1. Introduction

Tocharian vocabulary contains a large number of Iranian loanwords, belonging to different chronological layers and of different dialectal origins (Peyrot Reference Peyrot2015). The oldest layers are now most likely seen as belonging to an otherwise unattested Old Iranian dialect (Peyrot Reference Peyrot, Beek, Kloekhorst, Kroonen, Peyrot, Pronk and de Vaan2018), rather than to a reconstructed “Old Sakan” (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2005). More recent layers of borrowings, however, have so far received little or no attention. The medical vocabulary is in this respect emblematic. Whereas most technical terms are of Middle Indian origin, a significant number are Iranian (Carling Reference Carling2007: 330). The scholarly literature on the subject tends to view the Iranian component as being overwhelmingly of Khotanese origin. If this is true, it will enable us to uncover scenarios of historical transmission and contact between the North and the South of the Tarim Basin.

1.1. Siddhasāra and Yogaśataka

The preface to the Khotanese Siddhasāra,Footnote 2 the great medical work preserved also in Sanskrit (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1980) and Tibetan (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1982), may offer us a rare glimpse into the reception of medical texts in Central Asia:

It was R.E. Emmerick's idea (Reference Emmerick1983: 22) that the “collections of prescriptions (yauga-mālyo jsa)” could refer to the Yogaśataka, “which was popular not only in India and Ceylon but also in Central Asia”.Footnote 4 Such a reading of the passage is well worth considering, although I have not found any mention elsewhere of a rivalry between the Yogaśataka and Siddhasāra traditions. No Yogaśataka manuscript has been found in the South of the Tarim basin, but this is not sufficient to justify such an enmity. Moreover, Siddhasāra traditions are present in the North, although they are quite late.Footnote 5 It is possible, however, that the polemic passage of the Siddhasāra does not refer to a contrast between Southern and Northern oases. It could simply remind the reader of the contraposition existing between longer works that explained the medical theory and the popular collections of recipes such as the Jīvakapustaka, which were clearly made for practical use.Footnote 6 At any rate, if Emmerick's idea proves right, the preface of the Khotanese Siddhasāra might witness the late echoes of a contact scenario between the South and the North, which was already taking place at the time of the first Tocharian translation of the Yogaśataka in the North.Footnote 7 One could surmise that not only the Yogaśataka, but also other medical texts, were circulating widely between the South and the North. This could have been the reason why the Tocharian medical lexicon seems to be so composite, and the Iranian part appears to be overwhelmingly of Khotanese origin.Footnote 8 In such a contact scenario, one should obviously not underestimate the oral component, as pointed out by Carling (Reference Carling2007: 332).

In what follows, the Tocharian medical vocabulary of alleged Khotanese origin will be presented and analysed, in an attempt to verify whether such a contact scenario has to be assumed or not.

1.2. The Tocharian medical vocabulary of alleged Khotanese origin

Twelve medical lexical items have been selected. A distinction can be made between names of ingredients and technical vocabulary. Individual studies will attempt to verify whether the items have a clear Khotanese origin. Among the ingredients, we find:

• TB aṅkwaṣ(ṭ) subst. ‘Asa foetida’

• TB eśpeṣṣe subst. ‘spreading hogweed (Boerhavia diffusa)’

• TB kuñi-mot subst. ‘wine’

• TB kuñcit ~ kwäñcit A kuñcit subst. ‘sesame’

• TB kurkamäṣṣe ~ kwärkamäṣṣi adj. ‘pertaining to saffron’

• TB tvāṅkaro subst. ‘ginger’

In the following, the items belonging to the technical vocabulary are listed:

• TB ampoño subst. ‘rottenness, infection’

• TB ampa- v. ‘to rot, decay’

• TB krāke A krāke subst. ‘dirt, filth’

• TB krāk- ‘to be dirty’

• TB ṣpakīye subst. ‘suppository’

• TB sanapa- v. ‘to rub in, rub on, anoint, embrocate (prior to washing)’

It is important to note the presence of three verbs in this group, a feature that might suggest deeper linguistic contact (Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 70).

2. Names of ingredients

2.1. TB aṅkwaṣ(ṭ) subst. ‘Asa foetida’

Tocharian occurrences:

• aṃkwaṣ PK AS 2A a5, aṅkwaṣ PK AS 2A b2.Footnote 9 Both forms appear in a list of ingredients belonging to the Tocharian bilingual (Sanskrit–Tocharian) fragments of the Yogaśataka. The Sanskrit equivalent is hiṅgu- ‘id.’Footnote 10 in both cases (Tib. śiṅ-kun).

• aṅwaṣṭ PK AS 3B b5.Footnote 11 The word appears again in a list of ingredients, although the text has not yet been identified. It was classified as a medical/magical text. The title of the section to which the text should refer is given in line b4 as a generic bhūtatantra “Treatise against the demons”.

Khotanese occurrences:

• In the Siddhasāra it occurs in various orthographic shapes: aṃguṣḍä Si 19r4, 128r4, 130v2, aṃgūṣḍą’ 123r1, aṃgūṣḍi 126v4, aṃgūṣḍi’ 126r4, aṃgūṣḍä 10v1, 12v4, 123r5, 124v1, agūṣḍä 122r4, aṃgauṣḍä Si P 2892.82 and 127.

• In the Jīvakapustaka: aṃgūṣḍi Ji 56r4, aṃgauṣḍa 97r5, aṃgauṣḍi 52r1, 98r2, 98v2, 100v2, aṃgauṣḍä 61v5, 85v3, 104v5.

• In other medical fragments: aṃguṣḍi P 2893.219, aṃgųṣḍi P 2893.165.Footnote 12

The scholarly literature agrees on the Iranian origin of the Khotanese word and posits a Proto-Iranian form *angu-ǰatu-.Footnote 13 This is seen as a compound of *angu- ‘tangy, sour’ (Bailey Reference Bailey1957: 51) and *ǰatu- ‘gum’ and is continued by New Persian angu-žad.Footnote 14 From the occurrences in Late Khotanese medical texts, a Khotanese stem aṃguṣḍa- can be safely reconstructed as the original.Footnote 15 As pointed out by an anonymous referee, PIr. *-ǰat- > Kh. -ṣḍ- is not a regular sound change in Khotanese. The regular outcome would probably have been **angujsata- with PIr. *-ǰ- > Kh. -js- (cf. OKh. pajsama- < PIr. *upa-ǰama- (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004: II 293)). The first necessary step in order to obtain the Khotanese form is a syncope of the -a- in **°jsata-, which would have caused secondary contact between **-js- and **-t-. Such a contact, however, results in the cluster -ysd-, and not -ṣḍ-, as one can easily see in the formation of the 3sg. pres. mid. of type B verbs (SGS: 193), e.g. dajs- ‘to burn’ 3sg. pres. mid. daysdi (SGS: 43) and dṛjs- ‘to hold’ 3sg. pres. mid. dṛysde (SGS: 46). -ṣḍ- (/ʐɖ/) seems to point to secondary contact of original *-š- (> *-ž-) and *-t-,Footnote 16 e.g. pyūṣ- ‘to hear’ 3sg. pres. mid. pyūṣḍe (SGS: 87).

In view of these problems with a derivation of aṃguṣḍa- from Proto-Iranian directly, it is preferable to see in LKh. aṃguṣḍa- a loanword from an Iranian language in which intervocalic *-ǰ- underwent fricativization (> *-ž-). This might be e.g. Sogdian, in which old *-ǰ- gives regularly -ž- (GMS: 42), or even Parthian, for which the same sound change is attested (Durkin-Meisterernst Reference Durkin-Meisterernst2014: 96). Although highly speculative, a Sogdian or Parthian form might also be at the origin of the irregular -ž- found in New Persian angu-žad, which seems to alternate with a native form with -z- (angu-zad, Hassandoust Reference Hassandoust2015: I n° 525).

The dating of the syncope is crucial to determining whether the Tocharian form was borrowed directly from the unattested Sogdian (or Parthian, or another, unknown, Middle-Iranian language of the area) cognate that may be posited, or from Khotanese. It seems that the attribution of the syncope to Khotanese is not problematic: -a- was first weakenedFootnote 17 to -ä- in unstressed syllable (*angùžata- > *angùžäta-) and then lost. Moreover, New Persian angu-žad, if borrowed from Sogdian or Parthian, may show that the unattested form had no syncope (although this is far less certain). In other words, the Tocharian form needs a source language in which syncope has already taken place. This may be identified with Khotanese, in which the loss of -a- can be accounted for without problems. More questionable would be the possibility that loss of -a- was already realized in the unattested Middle-Iranian antecedent. Therefore, the chance that the Tocharian form was borrowed directly from Khotanese may seem higher than the possibility that Tocharian borrowed from Sogdian or Parthian. Nevertheless, this second possibility cannot be excluded.

As far as Tocharian is concerned, Iranian *-u- was reinterpreted as w + ǝ and, more precisely, as kw + ǝ, so that the word takes the aspect /ankwǝ́ṣt/. This phenomenon is to be observed also for a series of other Tocharian medical terms (TB kuñcit ~ kwäñcit, kurkamäṣṣe ~ kwärkamäṣṣi and kwarm < Skt. gulma-).Footnote 18 Since the development of u to u ~ wä ~ wa is thus understandable within Tocharian, the form may be derived from Khotanese without any problem.Footnote 19 The form aṅwaṣṭ with final -ṭ is older than the form without -ṭ, as aṅkwaṣ can be derived from the form with final -ṭ by sound law (Peyrot Reference Peyrot2008: 67).

Old Uyghur ʾnkʾpwš (Röhrborn Reference Röhrborn1979: 145), i.e. angabuš, probably via *anguwaš, with the absence of final -t as in Tocharian, and Chinese 阿魏 ē wèi Footnote 20 share the same semivocalic element -w- and must therefore be considered Tocharian loans. The history of the wordFootnote 21 may thus be provisionally reconstructed as follows: Proto-Iranian *angu-ǰatu- > *Sogdian (or *Parthian?) [*-ǰ- > *-ž-] → Khotanese aṃguṣḍa- [*-žat- > -ṣḍ-] → Tocharian aṅ(k)waṣ(ṭ) [-kwaṣṭ < -guṣḍ-] → Chinese and Old Uyghur (independently).

2.2. TB eśpeṣṣe subst. ‘spreading hogweed (Boerhavia diffusa)’

Tocharian occurrences:

• eśpeṣṣe THT 500–02 b9–10.Footnote 22 Otherwise, the more common word for the Boerhavia diffusa is punarṇap, LW < Skt. punarnavā, in PK AS 3A a5, W19 b1, W1 b4, W6 a6, W6 b5, W17 b5, W20 a5. Another hapax legomenon for the same plant is wärścik, LW < Skt. vṛścika-, in PK AS 3A a5.

Khotanese occurrences:

• The Khotanese equivalent occurs various times in the Siddhasāra and in the Jīvakapustaka, mostly preceding bāta, bāva, bā ‘root’:Footnote 23

• Siddhasāra: aiśca bāva 100r4, eśta bāta 133r2, eśtä bā 135v2, e’śte bāta 129v2, e’śte bāta 135v3, auśta bāta 9v5, auśte bāta 140r2, au’śte bāta 139r5, au’śtä bāta Si P 2892.71.

• Jīvakapustaka: aiśta bā 49r1, aiśta bāva 58v3, aiśta bā 62v2, auśta bā 66r5, iṃśta bā 73r5, iṃśta bāva 77v3, iṃśta bāva 84r4, äṃśta 80v5, iṃ’śta bāva 79v2.

• In other medical texts: u’śtä bāva P 2893.213.

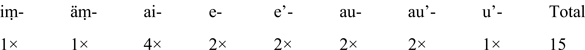

The Khotanese occurrences are attested in a puzzling series of different orthographies. It is immediately clear that such a vowel alternation in the first syllable is unprecedented, and therefore difficult to assess:

Five of fifteen total occurrences show a back vowel (au-, u-), whereas the rest point to a front vowel (i-, ai-, e-). H.W. Bailey's tentative explanation (DKS: 48) takes the forms with back vowel as original and posits a hypothetical *ā-vastyā-.Footnote 24 However, this leaves the forms with front vowel, i.e. the large majority, unexplained. The subscript hook, which occurs five times, might signal the earlier presence of a lost -l-, as in the case of OKh. balysa- and LKh. ba'ysa-, be'ysa-, bi'ysa-, bai'ysa-. Only a few occurrences of the word have a subscript hook, but in the case of ba'ysa-, too, the subscript hook is often omitted.Footnote 25 Indeed, the presence of both front and back vowels in the Late Khotanese notation might also point to a lost -l-, which is normally associated with fronting, as noted by an anonymous peer-reviewer. The case of hälsti- ‘spear’, however, which occurs in Late Khotanese both with initial ha’° and hu’° (DKS: 486), apparently shows that loss of -l- could also be associated with a back vowel. For the Khotanese word for Boerhavia diffusa, a hypothetical Old Khotanese form *alśta or *älśta can be then reconstructed. *älśta could be further interpreted as an inflected form of a stem *älsti-, a variant of OKh. hälsti- (SGS: 288) without initial h- (< PIr. *Hr̥šti- ‘spear’, cf. Av. aršti- and OP r̥šti- ‘id.’).Footnote 26

The use of terms for ‘spear’ to describe plants with reference to the oblong form of their leaves is documented in Latin, where the adjective lanceolātus ‘lanceolate’ is used as a botanical term. Since the leaves of the Boerhavia diffusa are not oblong or spear-shaped, the term may refer here to the form of its roots. However, given the tentative nature of this explanation, there is always the possibility that the word could represent a borrowing from an unknown language.

Adams (DoT: 104) compares the Khotanese word with Tocharian eśpeṣṣe. The meaning is secured by the Khotanese and Sanskrit parallel (Maue Reference Maue1990: 163 fn. 20). If -ṣṣe is an adjectival suffix, then we are left with something that closely resembles the Khotanese word, although Tocharian -śp- for Khotanese -śt- is not paralleled elsewhere. A possibility to obtain the cluster -śp- would be to consider the Tocharian word as a compound from LKh. *aiśti- + *bā(ga) > *aiśtäbā > *aiśtbā > TB eśpe.Footnote 27 However, this leaves the Tocharian vocalism of the final syllable unexplained, since it is very unlikely that LKh. <ā>, which probably had the value /ɔ/ (Emmerick Reference Emmerick and Brogyanyi1979: 245), could have resulted in TB -e-. Overall, the comparison seems rather doubtful.

2.3. kuñi-mot subst. ‘wine’

Tocharian occurrences:

• kuñi-mot IOL Toch 305 b1 (literary)

• kuñi motäṣṣe W20 a4 (medical)

• kuñi motsa W22 a3 (medical)

• kuñi *mot Footnote 28 W38 a6 (medical)

Khotanese occurrences:

• gūra- ‘grapes’ e.g. in Siddhasāra 12r2.

• gūräṇai mau ‘grape wine’ P 2895.29 (Paris Y).Footnote 29

Adams (DoT: 193) puts forward the hypothesis that the first part of the word may derive from LKh. gūräṇaa- (KS: 142), adjective to gūra- ‘grapes’, with loss of the medial syllable. LKh. gūräṇaa- is an adjectival formation which was formed with the suffix -īnaa- (PIr. *-ainaka-). The long -ī- of the suffix was shortened to -i- or -ä- in unstressed position. This phenomenon may be part of a more general tendency of vowel weakening before the nasal -n-, which is already attested in Old Khotanese (KS: 136). For the adjective gūräṇaa-, therefore, a proto-form *gudrainaka- may be reconstructed. If TB kuñi is really derived from the adjective gūräṇaa-, we must reckon with a loan from Khotanese, after the shortening of the long -ī- of the suffix (already Old Khotanese) and the loss of intervocalic -k-: kuñi < gūni < gūrṇi < LKh. gūräṇai (< PIr. *gudrainakah). At first sight, Adams’ suggestion might appear rather far-fetched. However, the occurrence of the adjective gūräṇaa- with mau ‘wine’ in the Late Khotanese lyrical poem contained in the manuscript P 2895Footnote 30 might support his hypothesis. Indeed, the parallel TB kuñi-mot ~ LKh. gūräṇai mau seems rather striking. The Tocharian B form would then be a partial calque with TB kuñi < LKh. gūräṇai and TB mot for LKh. mau. As suggested by the reviewer, it might be worth noting here that TB mot cannot have been borrowed from Sogdian, as stated e.g. by X. Tremblay (Reference Tremblay2005: 438). The form mwδy quoted by Gershevitch (GMS: 408) from the Ancient Letter IV, l. 5, is now recognized to mean ‘price’ (LW < Skt. mūlya-).Footnote 31

2.4. TB kuñcit ~ kwäñcit A kuñcit subst. ‘sesame’

Tocharian occurrences:

• TB kuñcit PK AS 3A a1; a3 (medical), PK AS 8C a7 (medical), THT 18 b5 (2×) (doctrinal), THT 3998 a3 (wooden tablet), W7 a6 (medical);

• TB kuñcitä THT 505 b2, THT 2676 b3;

• TB kwäñcitä THT 1535.c b3 (literary);

• TB kwäñcitṣa adj. (?) THT 1535.e b3 (literary);

• TB kuñcitäṣṣe adj. ‘made from sesame’ IOL Toch 306 a5 (medical), PK AS 2B a6; b4, PK AS 2C b6, PK AS 3A a6, PK AS 3B a2; b1 (Yogaśataka), PK AS 9B b6 (medical), THT 364 b1, THT 2677.d b1 (literary), W10 a3; a4, W19 b3, W24 a3 (medical);

• TB kuñcītäṣṣe adj. THT 27 a8 (doctrinal), THT 497 b4; b9, W4 a4; b2, W6 b1, W21 b2, W23 a2, W27 a3; b3, W30 b4, W31 b2, W33 b2, W34 a4, W35 a5 (medical);

• TB kuñcītaṣṣe adj. THT 497 b5 (medical);

• TB kuñcitäṣe THT 2348.i b2 (literary), THT 2347.a a2, b3 (literary);

• TA kuñcitṣi adj. ‘pertaining to sesame’ A 103 a5, A 152 a3, A 153 b6 (literary);

• TA kuñcit PK NS 2 a2 (medical);

• TA kuñcitaśśäl PK NS 3 b1 (medical).

The TB -ṣṣe adjective can refer to milk (malkwer), oil (ṣalype) or taste (śūke, only in THT 27, not medical).

Khotanese occurrences:

• In Old Khotanese the form is kuṃjsata- ‘sesame’, in Saṅghāṭasūtra 72.2, 73.1, 88.2, 72.2.Footnote 32

• The most frequent form in Late Khotanese is kuṃjsa-, in Siddhasāra 9v1, 16v2, 100r3, 101v2, 106r3, 132v3, 133r2, 142v1, 142v5, 143r1 (10x), Si P 2892.60, in other medical texts P 2893.35, 46, 48, 80, 89, 113, 120, 127, 131, 147, 158, 211, 218, IOL Khot. S. 9.2, 24, 31, 35, 40,Footnote 33 P 2781.29, in documents P 103.52 col. 2.1 (SDTV: 158). Without anusvāra (kujsa-) in Siddhasāra 9r4, P 2893.247, 251, 255, 262, KT IV: 26.4, 5, P 103.26.1, kāṃjsa in P 2893.235 and in the documents P 94.8.4 (SDTV: 98), P 94.23.4,7, P 95.6.2, P 96.4.2, P 96.4.3, P 97.3.2, P 98.6.5, P 98.7.1, P 103.5.2,7, P 103.5.4, P 103.5.8, kājsa in P 95.5.6, kuṃjsą in Ji 95r3, kuṃjsaṃna P 2893.56.Footnote 34

• The Old Khotanese adjective kuṃjsatīnaa-, °īṃgyā- ‘pertaining to sesame’ is to be found in Saṅghāṭasūtra 73.2, 37.3, 28.4, 73.1, 74.2, 88.2, 28.3, Śuraṅgamasamādhisūtra 3.14r3, 3.13v2; 4,Footnote 35 IOL Khot 34/2.a1 and IOL Khot 41/1.9.

• The Late Khotanese form of the same adjective is mostly kuṃjsavīnaa-: kuṃjsavīnā Si 139r2, 141r1, kuṃjsavīnį Ji 97r2, 97v1, 96v4, 98r2, 98v2, 99v2, kuṃjsąvīnį Ji 99r4, 101v3, kuṃjsavīnai Si 15r1, 100v2, 101r3, 104v1, 109v5, 129v4, 130r2, 144r1, 156r1, 156r4, P 2893.165, kuṃjsąvīnai P 2893.139, without anusvāra kujsavīña Si 155r4, kujsavį̄ña Si 153v4, kujsavīnai Si 128r2, 128r4, 128r4, 130r3, 130r4, 131r2, 141r3, IOL Khot. S. 9.22, 110, P 2893.167, 256 kujsavį̄nai Si 129r5, P 2893.179, kujsavīnya Si 141r2.

• kuṃjsārgye ‘sesame oil-cake’ in Si 9r5, P 2893.83.

The most recent Tocharian lexicographical works consider the word a loan from Khotanese.Footnote 36 This communis opinio is probably to be traced back to a note by H.W. Bailey (Reference Bailey1937: 913). However, he does not state directly that the form is Khotanese. He writes rather that the Tocharian B word represents “an older stage than Saka kuṃjsata-”. He further derives the Khotanese form (DKS: 61) from a reconstructed *kuncita-, which is based on Skt. kuñcita-, even if this seems to be used for another type of plant, the Tabernaemontana coronaria.Footnote 37 In fact, the Tocharian and Khotanese occurrences both in the Yogaśataka and in the Siddhasāra translate Skt. tila- ‘Sesamum indicum’, (KEWA I: 504), not kuñcita-. Tremblay (Reference Tremblay2005: 440) does not give any identification more precise than “Middle Iranian”. If the form is really Iranian, it might not be easy to find out if the Tocharian word actually derives from the proto-form *kunčita-, which seems to be at the origin of Sogdian kwyšt'yc,Footnote 38 Khotanese kuṃjsata-, Old Uyghur künčit Footnote 39 and Middle Persian kwnc(y)t (CPD: 52). For what concerns Pashto kunjǝ́la, an Indian origin is preferred by Morgenstierne.Footnote 40 He further extends his hypothesis to all Iranian forms, which he considers old loans from Indian. In general, the Pashto form seems to share with Khotanese the voiced affricate and a different vowel in the second syllable instead of the expected -i-.Footnote 41 Whereas the voiced dental affricate instead of the unvoiced palatal is regular in both languages,Footnote 42 no satisfactory explanation for the different vowel is available.

On the whole, it might be difficult to trace the history of the word. Since the Indian forms are attested rather late and occur only in lexica, it is dangerous to reconstruct a Proto-Indo-Iranian form. In this case, Tremblay's general label “Middle-Iranian” seems the safest solution for the time being.Footnote 43

2.5. B kurkamäṣṣe ~ kwärkamäṣṣi adj. ‘pertaining to saffron’

Tocharian occurrences:

• kurkamäṣṣi PK AS 3B b5, THT 497 b8, THT 498 a8, W4 b1; b4, W7 b3, W19 b5, W20 a5, W21 b4, W26 b4, W32 a4, W38 a5, W39 a3, W41 b3 (all medical).

• kwärkamäṣṣi W29 b1 (medical).

• THT 2676 a3 (kurkumä-) at the end of the line, it could also be restored as kurkumä(ṣṣe) (Peyrot Reference Peyrot2014: 139, fn. 47).

Khotanese occurrences (only Late Khotanese):

• kurkāṃ Ji 97v3 and P 2893.62;

• kųrkāṃ P 2893.57;

• kurkuṃ Si 10v2;

• kūrkāṃ Ji 108r5;

• kūrkūṃ Ji 105v1;

• kų̄rkūṃ Ji 44v1;

• kurkumīnā […] prahaunä ‘saffron […] garments’ KT III: 1.9r5,Footnote 44 < adj. kurkumīnaa- (KS: 141).

Here is not the place to reconsider the whole history of the word, which does not seem to be specifically Iranian and can be traced back in time as far as Akkadian kurkanū and Greek κρόκος.Footnote 45

The basis for the Tocharian form must have been provided by an unattested *kurkuma-. As in the case of aṃkwaṣṭ and kuñcit ~ kwäñcit (cf. 2.1 and 2.4), *ku was reinterpreted as kw + ǝ, so that we obtain the spelling /kwǝrkwǝm/, further dissimilated to /kwǝrkǝm/. This (*kurkäm) might have been the original form from which the adjective was derived through accent shift (/kwǝ́rkǝm/ > /kwǝrkǝ́m°/). The tiny fragment THT 2676 is one of the earliest Tocharian manuscripts (Peyrot Reference Peyrot2014: 139 and Malzahn Reference Malzahn and Malzahn2007: 267) and might have conserved the undissimilated form /kwǝrkwǝm/. Since all Indian forms (CDIAL: 3214, cf. Skt. kuṅkuma-) have a nasal instead of the expected -r-, it is more probable that the Tocharian word derives from Iranian. Given the fact that saffron is known to grow in Persia (Laufer Reference Laufer1919: 320), a Middle Persian origin (Pahlavi kwlkwm (CPD: 52) and New Persian kurkum Footnote 46) is suggested by Tremblay (Reference Tremblay2005: 437). Otherwise, the Middle Persian form might have reached Tocharian through Khotanese *kurkuma- (DKS: 63). In fact, this is the form which might be reconstructed for Old Khotanese based on the Late Khotanese occurrences.Footnote 47 However, as noted by a referee, there is no special phonetic feature that might be attributed to Middle Persian proper. Tremblay's idea seems thus quite arbitrary and a Middle Persian origin remains highly doubtful. For the time being, it seems safer to consider the origin of the Tocharian word as coming from a general ‘Middle-Iranian’ context, without further specification. It might be noted further that Sogdian kwrkwnph,Footnote 48 because of the final labial plosive, remains a less probable candidate. An Iranian origin has been also suggested for Tib. kur-kum (Laufer Reference Laufer1916: 474).

2.6. TB tvāṅkaro subst. ‘ginger’

Tocharian occurrences:

• twāṅkaro THT 497 a7; b5, PK AS 9B a4 (medical).

• twaṅkaro PK AS 9B b2 (medical).Footnote 49

• tvāṅkaro PK AS 2A b2, PK AS 3B b5 (all Yogaśataka), PK AS 9A b7 (medical), THT 500–502 b7 (Jīvakapustaka).

• tvāṅkaraimpa (com. sg.) PK AS 2B a2.

• tvāṅkaracce (obl. sg. m. of tvāṅkaratstse) PK AS 2A a6 (medical).Footnote 50

Khotanese occurrences:

• ttūṃgara Ji 78v4, 82v3, 88r2, 93v3, 98v2, 99r3, 99v2, 99v3, 101v2, 106v4, 109r5, 11v1, 112r4, 115r2, 115v5, 116r5;

• ttūgara Ji 98r2;

• ttūṃgarą Ji 58v2;

• ttūṃgarä Ji 88r4, 106r4, 110r3, 111r1, 113r1, 115r5;

• ttūgarä Ji 87r2;

• ttūṃgarāṃ Si 130v5;

• ttūgare Ji 57r4;

• ttūṃgare Si 146r2;

• tūṃgare Si 101v5.

H.W. Bailey's initial idea (Reference Bailey1937: 913) sought to explain TB -vā- against Khotanese -u- by comparing TB aṅkwaṣ(ṭ) and Khotanese aṃguṣḍa-, simply taking note of the same correspondence, without offering any further explanation. This is not possible because the Tocharian form contains here clearly /wá/ (<wā>) and not /wə́/ (<wa>) for /u/ as in aṅkwaṣṭ (see 2.1). Some time later, however, he developed a new etymological proposal.Footnote 51 He derived the Khotanese word from *tuwam-kara- with *tuwam° from the Proto-Iranian root *tauH- ‘to be strong, swell’ (Cheung Reference Cheung2007: 386). In this case, the Tocharian form would have conserved the Pre-Khotanese state of affairs and should be considered as a very old loan (Tremblay Reference Tremblay2005: 428 and DoT: 343). Bailey's derivation seems to imply a nominal form *t(u)v-a- from the verb *t(u)v- ‘to be strong’ (DKS: 144). This root is attested as verb with causative suffix -āñ- in LKh. tv-āñ- ‘to strengthen’ (SGS: 41). Several nominal forms from the same root are also to be found as medical terms, e.g. LKh. tv-āñ-āka- ‘strengthener’ (KS: 46)Footnote 52 and LKh. tv-āmā- (< *tv-āmatā-) ‘strengthening’ (KS: 94).Footnote 53 The case ending of the first member of the compound would have been preserved in the nasal *-m- before the second member *-kara-, as is the case in similar compounds, cf. e.g. dīraṃggāra- ‘evil-doing’ (SVK I: 56, Degener Reference Degener1987: 39). This derivation, however, seems semantically difficult. tv-a- must be a substantive (KS: 1) with the meaning ‘strong one’, ‘strong thing’ or ‘fat’. The resulting compound could be then approximately translated as ‘maker of strong (things or beings)’. Admittedly, such an attribute would be suitable for a person, not for a plant. It would be then desirable to have an adjective as first member of the compound. This is indeed possible if one starts with a form tv-āna-, an -āna- derivative (pres. part. mid. KS: 78) from the root tv-, which could produce a proto-form *tvāna-kara- ‘strong-maker’. This would yield OKh. *tvāṃgaraa- Footnote 54 through syncope of internal unaccented -a-. Both Old Khotanese reconstructed forms, *tv-aṃ-garaa- and *tv-āṃ-garaa-, may have been antecedents of the attested LKh. ttūṃgara-, since both OKh. tvā° and tva° may result in LKh. ttū°. For tvā° > ttū° one may compare the possessive adj. OKh. tvānaa- ‘your’ (KS: 85) which occurs in LKh. as ttūnā (IOL Khot S. 15.11) and for tva° > ttū° OKh. tvaṃdanu ‘reverence’ (SGS: 219) and its Late Khotanese counterpart ttūda (IOL Khot S. 6.27). Both Old Khotanese reconstructed forms may as well have been borrowed into Tocharian B. There is indeed no need to consider TB tvāṅkaro as a Pre-Khotanese loanword. The evidence suggests that the word may have been borrowed from the Old Khotanese antecedent of LKh. ttūṃgara-.Footnote 55

It might be worth noting that Tib. li doṅ-gra, which translates Skt. nāgara- ‘ginger’ in the Siddhasāra (Emmerick Reference Emmerick, Gnoli and Lanciotti1985: 313 and Bielmeier Reference Bielmeier and Scherrer-Schaub2012: 21–2) is also a Khotanese loan. That the borrowing took place from Khotanese is made clear by the preceding li, which always refers to Khotan (Laufer Reference Laufer1916: 455 fn. 1).

3. Technical vocabulary

3.1. TB ampoño subst. ‘rottenness, infection’

Tocharian occurrences:

• ampoñaṃtse (gen. sg.) PK AS 3A a1; a6; b1 (medical);

• ampoññaṃtse (gen. sg.) PK AS 3A a2 (medical);

• ampoñai (obl. sg.) THT 503 a3 (medical);

• ampoño (nom. sg.) THT 510 b6 (medical).

In the manuscript PK AS 3A it is used consistently in the gen. sg. with sāṃtke ‘remedy’. The text describes four remedies against ampoño. All other occurrences refer to medical texts.

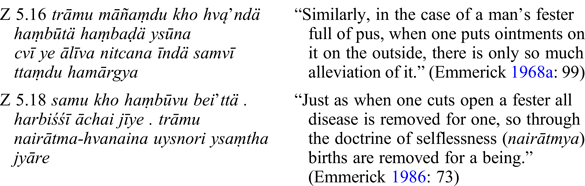

Adams’ second edition of his Tocharian B dictionary contains the following statement s.v. ampoño: “A nomen actionis from āmp- ‘rot,’ q.v., from Khotanese hambu-, i.e., hambu- + the Khotanese abstract-forming suffix -oña” (DoT: 21). In Old Khotanese there is indeed a word haṃbūta- occurring in Z 5.16 and 5.18,Footnote 56 two passages which present us with two literary similes involving medical terminology:

This has the aspect of a past participle from the Proto-Iranian root *pauH- ‘to stink, smell, rot’ (Cheung Reference Cheung2007: 302), to which a preverb *ham- has been added.Footnote 57 In the corresponding stanzas of the Mañjuśrīnairātmyāvatārasūtra, the word appears regularly as ha(ṃ)bu in both occurrences, as one would expect in Late Khotanese.Footnote 58 It is clear from a second set of occurrences in the Late Khotanese medical text P 2893 (KT III: 82–93) at lines 184, 185 and 189 that the word is a technical term. Here the word occurs in the spelling haṃbva(’)- (< haṃbuva- < haṃbūta-) always with the meaning ‘fester’. The reference to ‘hambu’ in DoT: 21 seems to take into consideration only one of the Late Khotanese forms, without commenting on the Old Khotanese one, which should be first compared with Tocharian. Otherwise, ‘hambu’ might stand for *hambu- and might be a reference to the unattested present stem from which the past participle haṃbūta- is derived. However, the suffix -ūña-/-auña- can be added to past or present participles but there is no example with the suffix being added directly to a present stem (KS: 159). If one were to add it to haṃbūta-, one would expect *haṃbūttauña-, in line with the attested hämättauña- (< past part. hämäta-) (KS: 164). The resulting intervocalic -t- seems to undergo strengthening rather than be lost altogether. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that intervocalic -t- was lost in this case already in Khotanese. In fact, as suggested a referee, -tt- in the hapax hämättauña- might be an example of ‘morphologische Verdeutlichung’ (KS: 162), i.e. a way to stress the presence of a morpheme boundary before the suffix. If this is correct, one could see in ampoño the past part. LKh. haṃbva- to which the suffix -auña- has been added. This would confirm the hypothesis of a Late Khotanese origin of ampoño, as suggested by Adams.

From the Tocharian point of view, however, there is still the possibility that ampoño is a genuine Tocharian formation based on the verb TB ampa- (borrowed from LKh. haṃbva-, see 3.2). In fact, all attested forms point to a nom. sg. ampoño or ampoña*. Because of the palatalization, ampoña would be the expected form (M. Peyrot, personal communication). THT 510, the fragment containing the only occurrence for ampoño, is normally classified as late, so the form might be simply interpreted as secondary for earlier ampoña (Peyrot Reference Peyrot2008: 99–101). This form would have the appearance of a derivative in -’eñña from a verbal root,Footnote 59 which in this case could be ampa- ‘to rot’ (see 3.2). For the forms with single -ñ- for the expected -ññ- one might compare the obl. sg. of wṣeñña, which is attested four times with a single -ñ- (IOL Toch 117 b4, Km-034-ZS-R-01 a7, PK AS 16.7 a4, IOL Toch 62 a3).

3.2. TB ampa- v. ‘to rot, decay’

Tocharian occurrences:

• THT 9 b7 stastaukkauwa āmpauwa spärkauw= ere : ⋅ai /// ‘swollen, rotten, void of colour’, parallel THT 10 a3 as preterite part. nom. pl. m. (doctrinal).

D.Q. Adams (DoT: 48) regards it as a Middle Iranian loanword from the same root as Khotanese haṃbūta-, New Persian ambusidan, etc. Malzahn (Reference Malzahn2010: 525) seems to be of the same opinion and would rather take the word as a Khotanese loanword. If from Khotanese, one might envisage the possibility that the form has the aspect of a denominative formation from LKh. haṃbva (< Old Khotanese haṃbūta-, see 3.1), resulting in TB amp(w)a-. This verb can be thus traced back with a fair degree of certainty to Late Khotanese.

3.3. TB krāke TA krāke subst. ‘dirt, filth’

Tocharian occurrences:

• A krāke nom. sg.? A 211 a1, a3, THT 2494 a2, nom. pl. krākeyäntu THT 2401 a3, obl.pl. krākes A 152 a4 (all literary texts).

• B krāke gen. sg. IOL Toch 4 kr(ā)ke(t)s(e) (doctrinal), IOL Toch 262 b4 (literary), PK NS 49B a2 (doctrinal, karmavibhaṅga), THT 7 a7; b2 (doctrinal), THT 159 b6 (abhidharma), THT 221 b4 (literary), THT 334 b1 (literary, vinaya, here it may refer to spermFootnote 60), THT 388 a6, THT 408 b6 (both literary in THT 408 in the expression kleśanmaṣṣe krāke, ‘the filth due to kleśas’), THT 522 a4 (doctrinal), THT 537 b5 (doctrinal), THT 1118 (vinaya, snai krāke ‘unstained’), THT 1192 a6 (literary, cmelṣe krāke ‘the filth pertaining to rebirth’), THT 1227.a a3 (literary, very fragmentary), THT 1258 a4 (literary), THT 2227 b1 (literary), W2 a6 (only occurrence in a medical text, ratre krāke ‘the red filth’).

The Tocharian A form is probably borrowed from Tocharian B.

Khotanese occurrences:

• OKh. khārggu acc. sg. Z 19.53.

• OKh. khārggä nom. sg. IOL Khot 150/3 r4 (Bodhisattva-compendium, Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2002: 337).

• OKh. khārja loc. sg. Z 5.90 (kho ju ye viysu thaṃjäte khārja ‘as one pulls a lotus out of the mud’).

• LKh. khā’ja loc. sg. P 4099.355 (sa khu vaysa khā’ja sūrai ‘just like the clean lotus in the mud’).

• LKh. khā’je loc. sg. Si 136v3, 136v4 (in both cases tr. of Skt. kardama-), P 4099.278 (sa khu veysa khā’je sūrai ‘just like the clean lotus in the mud’).

• LKh. khāje loc. sg. P 4 12r4 (Adhyardhaśatikā, see SDTV: 29).

• LKh. khāji loc. sg. P4 12r4–5 (Adhyardhaśatikā, see SDTV: 29).

• LKh. kheja loc. sg. (with further fronting of -ā-) Jātakastava 27v4.

• LKh. khājaña- loc. sg. (see SGS: 262 for the ending) Jātakastava 23v2.

It seems that the first scholar to put forward this etymological proposal was Van Windekens (Reference Van Windekens1949). Isebaert (Reference Isebaert1980: §180) finds the derivation unconvincing and suggests an Indo-European origin. His main criticism of Van Windekens’ proposal is based on morphological reasons. According to him, Middle Iranian loanwords never receive the masculine -e. Whereas Bailey's Dictionary (DKS: 74) does not seem to take note of the possibility of a loanword, Tremblay (Reference Tremblay2005: 433) returns to Van Windekens’ proposal and reports it without any further comment. The Khotanese word is formed from the Proto-Iranian root *xard- ‘to defecate’Footnote 61 to which the suffix -ka- has been attached (KS: 181), resulting in *xardaka-. In order to obtain the attested forms, one has to assume a series of metatheses which took place very early, at least earlier than the sound change -rd- > -l- in Khotanese: *xardaka- > *xadraka- > *xadarka-. This might have been the base for Yidgha xǝlarγo (from a feminine *xadarkā-, EVSh: 79) and Khotanese khārgga-, through loss of intervocalic -d- and voicing of -k-.

Given the specificity of the formation, if the word is a loanword, it cannot come but from Khotanese. After all, it seems that Khotanese ‘mud’ refers to the same semantic areas of Tocharian ‘dirt’ and ‘filth’.Footnote 62 In this case, the Khotanese form would have undergone in Tocharian a further metathesis to become krāke.

3.4. TB krāk- ‘to be dirty’

Tocharian occurrences:

• krākṣtär PK AS 7M b1 (doctrinal, Karmavibhaṅga).

As reported by Adams (DoT: 229), the meaning ‘to be dirty’ was suggested by M. Peyrot (apud Malzahn Reference Malzahn2010: 612) on the basis of the substantive TAB krāke, from which the verb is derived. The passage in question, which refers to poor, blurred eyesight, seems to justify such an interpretation.

3.5. TB ṣpakīye subst. ‘suppository’

Tocharian occurrences:

• ṣpakīye THT 510 b1, W15 b3 (2×), W38 b5, W39 b1.

• ṣpakaiṃ W3 a3, W8 b4, W9 a3, W 10 a4, W34 b2, W42 b1 (all medical).

All occurrences of the plural come together with yamaṣṣällona, gerundive of yām- ‘to make’, e.g. in the phrase W3 a3 ṣpakaiṃ yamaṣṣällona ‘suppositories are to be made’. This is exactly paralleled by the Khotanese technical phrase ṣvakyi padīmāñä (e.g. Si 122r1, part. nec. of padīm- ‘to make’), with the same meaning.

Khotanese occurrences:

• ṣvaka Si 121v5, 150v5.

• ṣvakyi Si 122r1, 122r3, 148v5, 149r4, 149v5, 151r1.

• ṣvakye Si 121v5, 151r1 (2×), 151r2, 151r4, 151r5 (2×).

• All occurrences of ṣvakā- are from the Siddhasāra. It translates Skt. varti ‘suppository’ and guḍikā ‘pill’ and Tib. reng-bu and ri-lu ‘pastil’).

The first scholar to make known the word was H.W. Bailey (Reference Bailey1935: 137). The striking correspondence with the Tocharian word was again noted by him some years later (Bailey Reference Bailey1947: 149). A further clarification of the meaning and the etymology is offered by R.E. Emmerick (Reference Emmerick1981: 221).Footnote 63 There the meaning is established as ‘suppository’ against Bailey's ‘pastil’. The etymology is given as < PIr. xšaudakā-, a formation from the root *xšaud- ‘to wash’ (Cheung Reference Cheung2007: 455). Since the word is a very specialized medical term, one should assume that the borrowing took place quite late, when Indian medical texts were already circulating within the Tarim basin. As it is attested only in the Late Khotanese Siddhasāra, the word was possibly borrowed from Late Khotanese, although it is not to be excluded that Old Khotanese translations of medical texts existed, even if they are no more extant. In this case, a possible Old Khotanese form may have been *ṣṣūdakā- or *ṣṣūvakā-, as intervocalic -d- might have been lost already in Old Khotanese (see e.g. OKh. pāa- < PIr. *pāda-). The preservation of intervocalic -k- is noteworthy. The possibility that the Tocharian word was borrowed from Late Khotanese may seem more probable, as the nearest antecedent of the Tocharian initial cluster ṣp- may have been LKh. ṣv- rather than OKh. *ṣṣūv-. Thus, TB ṣpakīye must be considered a Late Khotanese loanword in Tocharian.

3.6. TB sanapa- v. ‘to rub in, rub on, anoint, embrocate (prior to washing)’

Tocharian occurrences:

• 3sg. pres. mid. sonopträ W40 b3 (se ce ṣalype sonopträ ‘C'est cette huile qui est ointe’ (Filliozat Reference Filliozat1948: 88)).

• 3sg. opt. mid. sonopitär PK AS 6B a6 (sonopitär likṣītär wästsanma krenta yäṣṣītär ‘anointing himself, washing himself, [and] wearing beautiful clothes’).

• pres. ger. sonopälle PK AS 8C b1 (partāktaññe pitkesa ṣarne s(o)nopäll(e) ‘one has to smear both hands with spittle of viper [Vipera russelli]’), PK AS 9A b8 (se ṣälype mel(eṃn)e (yänmā)ṣṣä«ṃ» • tärne sonopälle ‘This oil (reache)s the nos(trils). The crown of the head [is] to be anointed’), THT 497 b1, THT 2677.d b2, W7 b5, W26 b3, W40 b2.

• subj. ger. sanāpalle W27 b1 (mälkwersa kātsa sanāpalle ‘à appliquer en onctions au ventre avec du lait’ (Filliozat Reference Filliozat1948: 85)), W35 a6, W39 a4, W41 b2.

• inf. sanāpatsi W4 b3, W14 a2, W29 b1, W34 a5.

• perl. san(āpo)rsa PK AS 8C b1 (san(āpo)rsa ka tweri rusenträ ‘just by smearing the doors will open’).

All occurrences are from medical texts.

Khotanese occurrences:

ysänāj-:

• 3sg. opt. OKh. Z 3.102, kho ju ye ysänājä nei’ṇa uysnauru samu ‘as if one should bathe a being with nectar alone’ (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 69).

• inf. OKh. Z 24.220, ttī akṣuttāndä pajsamä käḍäna ysänājä ‘then [they] began to bathe him to do him reverence’ (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 383).

• 3pl. pres. LKh. Suv 3.47 ysinājīde muhu ba'ysa. mu’śdī'je ūci jsa pvāśkye ‘may the Buddhas bathe me in the cool water of compassion’ (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004: I 49).

ysänāh-:

• 1sg. pres. LKh. P 2027.28 ysīnāha’ (< OKh. *ysänāhe) ‘I wash (off myself ?)’ (Kumamoto Reference Kumamoto1991: 65).

• 3sg. pres. LKh. Jātakastava 6v1–2: tta khu ttaudäna haṃthrrī satvä viysāṃji ysināhe (< OKh. *ysināhätä) ‘just as a man tormented by heat bathes in a lotus pool’ (Dresden Reference Dresden1955: 424) and Sudhanāvadāna 373: haḍai sṭāṃ drai jūnäka aharṣṭi ysīnāhe ‘Because of that she bathes three times a day’ (De Chiara Reference De Chiara2013: 151).

• part. nec. OKh. Suv 8.36: ysänāhāñu ‘he should bathe’ (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004: I 189).

• part. nec. in Siddhasāra 135v2 (as a medical term) LKh. vameysą̄ñä u ysīną̄hāñą ‘must be massaged and bathed’ (Emmerick Reference Emmerickunpublished), Sudhanāvadāna 235 and 233 (De Chiara Reference De Chiara2013: 111, 139) and IOL Khot 160/4 v3 u drrai jūna haḍe ysināhāña ‘and three times a day one should wash’ (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2002: 359).

• 3pl. perf. tr. IOL Khot 147/1 r5 haṃdāra ysinauttān[d]ä ‘some washed (themselves)’ (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2002: 331).

• past part. OKh. Suv 13.17 + hu- ‘well-’ huysänauttī ttarandarä ‘his body well-bathed’.Footnote 64

haysñ-

• 2sg. impv. P 5538b 88 rīmajsa pamūha ttai haysña ‘dirty clothes. Wash.’ (Kumamoto Reference Kumamoto1988: 69).

• 3sg. pres. OKh. Z 4.96 o kho käḍe rrīmajsi thauni kṣārä biśśä haysñäte rrīma ‘or as when lye cleans all the dirt on a very dirty garment’. (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 93).

• part. nec. LKh. as a medical term in Siddhasāra 100r5 haysñāña ‘(a medicinal herb) is to be washed’.

• 3sg. perf. tr. m. OKh. Z 2.170 pātro haysnāte ‘he has washed the bowl’ (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 39), and 21.13 kvī ye haysnāte käḍe ‘when one had washed it [the face] thoroughly’ (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 299), LKh. IOL Khot 75/4 b2Footnote 65 pā haysnātä ‘he washed (his) feet’, IOL Khot 28/14 b3–4 kamalä haysnā[te] ‘he washed the head’. (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2002: 233).

• Past part. in the LKh. adj. haysnālīka- (KS: 309 < haysnāta- + suffix -līka-) ‘washed (of clothes)’ in IOL Khot 140/1a6–7, 10, 11, 12.Footnote 66

From the occurrences above, it seems that in Khotanese the three verbs had adopted three different semantic specializations: ysänāj- ‘to wash, bathe another person’, ysänāh- ‘to wash, bathe oneself’ and haysñ- ‘to wash, clean a thing or a part of the body’. This gives a meaning which is slightly different from Tocharian ‘to anoint’. Whereas haysñ- can be derived without difficulties from *fra-snā-ya (with past part. haysnāta- < *fra-snāta-) and ysänāh- from *snāfya- (with past part. ysinautta- < *snāfta-), the derivation of Khotanese ysänāj- is not straightforward. The *k/g increment hypothesized by Bailey (DKS: 351) and Emmerick (SGS: 113) seems quite arbitrary and it is not attested in any other language (Cheung Reference Cheung2007: 348). The voiced fricative at the beginning of the word can be explained by the vicinity of -n-, so that we might have had *snā- > *znā > *zǝnā- (<ysänā>) with the additional development of an epenthetic -ä-.

Adams (Reference Adams and Arbeitman1988: 402–3) proposed that TB sanapa- ‘to rub, anoint’Footnote 67 could be derived from the Pre-Khotanese antecedent of Khotanese ysänāh- ‘to wash’, i.e. from the stage at which Proto-Iranian intervocalic *-f- had still not shifted to -h-. Since no -f- exists in Tocharian, this could give only TB -p-. The vocalism he explains by arguing that the Khotanese verb was borrowed first as *senāp-, probably implying that the Khotanese vowel -ä- of the first syllable was pronounced as [ẹ], i.e. a mid-front vowel. This vowel, however, is rather to be interpreted as [ǝ], since it occurs as an epenthetic vowel in unstressed position (Emmerick Reference Emmerick and Brogyanyi1979: 442). Whatever the interpretation of the first vowel, however, there is no need to postulate a further metathesis (*senāp- > /sānep-/), as did Adams (Reference Adams and Arbeitman1988: 403), since, if the verb was borrowed as senapa-, sanapa- may be simply obtained through a-umlaut.

In conclusion, Adams is probably correct in interpreting the word as a loan from Iranian. Further, it seems clear that sanapa- can only be derived from Pre-Khotanese, as this is the only Iranian language which has a -p- increment to the root PIr. *snaH- (Cheung Reference Cheung2007: 348), no word-initial palatal,Footnote 68 and an extra epenthetic vowel in the first syllable.

4. Conclusion

Of the twelve lexical items analysed, one (sanapa-) can be derived from Pre-Khotanese and nine (aṅkwaṣ(ṭ), eśpeṣṣe, kuñi-mot, tvāṅkaro, ampa-, ampoño, krāke, krāk-, and ṣpakīye) can be ascribed to Khotanese proper. Among these, tvāṅkaro is certainly an Old Khotanese borrowing. For eśpeṣṣe, kuñi-mot, ampa-, ampoño (if not directly from ampa-), and ṣpakīye a Late Khotanese origin can be posited, although for eśpesse this remains for now too uncertain. There is unfortunately no way to determine whether aṅkwaṣ(ṭ) and krāke (with its derivative krāk-) have been borrowed from Old or Late Khotanese. For the remaining two items (kuñcit and kurkamäṣṣe), an Iranian origin can be given as certain, although the dialect affiliation is still not completely clear.

I am aware of the fact that the dimensions of the analysed corpus are quite small. Nevertheless, from these results one may argue that contact between Khotanese and Tocharian took place uninterruptedly from prehistoric times until the epoch of the first written attestations. In particular, the medical lexicon may bear traces of contact both at an oral level in the Pre-Khotanese epoch and at a written level in the historical epoch. Five items that can be attributed to Khotanese proper, ampa-, ampoño, kuñi-mot, krāke and ṣpakīye, are in fact technical terms which show a high level of semantic specialization. They must be assigned to a period in which Indian medical knowledge was already circulating widely in written form in both the South and North of the Tarim basin.

Technical abbreviations

Bibliographic abbreviations

CDIAL = Turner Reference Turner1962–85

CPD = MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1971

DKS = Bailey Reference Bailey1979

DoT = Adams Reference Adams2013

EDP = Morgenstierne Reference Morgenstierne2003

EVSh = Morgenstierne Reference Morgenstierne1974

EWA = Mayrhofer Reference Mayrhofer1992–2001

GMS = Gershevitch Reference Gershevitch1954

KEWA I–IV = Mayrhofer Reference Mayrhofer1956–80

KS = Degener Reference Degener1989

KT I–VII = Bailey Reference Bailey1945–85

MW = Monier-Williams Reference Monier-Williams1899

SDTV = Emmerick and Vorob’ёva-Desjatovskaja Reference Emmerick and Vorob’ёva-Desjatovskaja1995

SelPap I–II = Henning Reference Henning and Boyce1977

SGS = Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968b

SVK I = Emmerick and Skjærvø Reference Emmerick and Skjærvø1982

SVK II = Emmerick and Skjærvø Reference Emmerick and Skjærvø1987