Introduction

By the close of 2021 the church press was recording the sobering impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the resilience of the Church of England. Experience was suggesting a decline in active participation and a decline in revenue generation. The Church Times of 3 December 2021 led on summarizing findings from the Evangelical Alliance: ‘Church attendance has fallen by a third since before the pandemic, and many regular worshippers have been attending only monthly since in-person services resumed this summer’.Footnote 2 The previous issue of the Church Times on 26 November 2021 had given full coverage of the November meeting of the General Synod and led on summarizing the report from the finance chair of the Archbishops’ Council:

Mr Spence again highlighted the ‘profound’ impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on parish income…. It had been running at ten per cent below 2019 levels; for September it was running at two per cent lower even than September 2020…. ‘But we are learning that it is proving much more difficult to recover, and I have to question whether we will ever again reach the levels that it did in 2019, when we knew that numbers of regular givers were declining and their age was increasing.’Footnote 3

Against this background, the aim of the present paper is to interrogate the responses of non-ministering members of the Church of England to the Covid-19 & Church-21 Survey in order to gain insight into individual differences associated with giving up on the Church of England in the time of pandemic. First, however, attention is drawn to findings from two research traditions. The first of these two bodies of research is well established and concerns the motivations for leaving church: why do people give up on churchgoing? The second of these two bodies of research is recent and shaped within the experience of the pandemic: how have people responded to the enforced migration to digital worship?

Why People Give Up on Church

The Church Leaving Applied Research Project, established during the 1990s, was designed to clarify the various motivational strands involved when people leave churches. The one obvious conclusion arising from the study was that multiple issues are involved. The study used a mixed-methods approach combining qualitative and quantitative data. The qualitative component comprised 27 in-depth interviews with a range of people who had left – or in a few cases switched between – Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist or New Churches, alongside interviews with 11 clergy, exploring their perceptions of why people leave, and interviews with 37 young people associated with the Methodist Association of Youth Clubs (MAYC). The quantitative component employed a random telephone survey to identify a sample of church-leavers among the general population. The calls identified 1604 individuals who were willing to receive a postal questionnaire and who had once attended church at least six times a year (not including Christmas and Easter), but who had subsequently lapsed to less than six times a year. Questionnaires were successfully mailed to these individuals and 56 per cent of these were returned and were suitable for analysis.

In the first book emanating from the Church Leaving Applied Research Project, drawing on an interim set of the data, Richter and FrancisFootnote 4 distilled eight core motivational themes. In the second book, drawing on the full data, Francis and RichterFootnote 5 further refined their analysis to identify 15 motivational themes. These were categorized as: matters of belief and unbelief; growing up and changing; life transitions and life changes; alternative lives and alternative meanings; incompatible lifestyles; not belonging and not fitting in; costs and benefits; disillusionment with the church; being let down by the church; problems with relevance; problems with change; problems with worship; problems with leadership; problems with conservatism; and problems with liberalism. Underpinning these 15 themes were three cross-cutting strands, which may have relevance for giving up during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The first strand concerned the importance of affect over cognition. Church-leaving was more likely to be an emotional response than an entirely rational response. Church-leaving was more closely related to how people felt than to what they believed. For some people the pandemic may have touched a raw nerve and may have been unsettling. Worship may have been less able to touch emotions than it had been before. It would not, then, be surprising if this was reflected in some becoming church-leavers.

The second strand concerned the impact of change. Change was seen in the impact on beliefs, on life transitions, on lifestyles, on relevance and on the disturbance of familiarity. The pandemic profoundly changed the way many people were able to express and maintain their faith. Online worship was an unfamiliar ritual, and when offline services in church resumed, they were not necessarily a safe return to the former familiar patterns. It would not, then, be surprising if this was reflected in some becoming church-leavers.

The third strand concerned the power of habit in sustaining churchgoing. Of the 153 items in the quantitative survey, an item that received one of the highest endorsements was simply this: ‘I got out of the habit of going to church’, endorsed by 69 per cent of the participants. For many people, getting out of the habit of going to church was not synonymous with giving up on God: 75 per cent of church-leavers believed that they did not need to go to church to be a Christian. The moratorium on going to church enforced by the pandemic may just have been sufficient to break the habit shaped by years of attendance.

The issues of how churchgoers manage change and what happens when habits are suddenly broken came to the fore during the Covid-19 pandemic. Both academy and Church wondered what the consequences might be for the medium-term future. Hazel O’Brien, for example, drew on the work of Danièle Hervieu-Léger to suggest Irish Catholicism may use the opportunity to adapt in ‘fascinating and unexpected ways’.Footnote 6 Others have noted both the opportunities and challenges for researchers responding to such an unprecedented event.Footnote 7

Experiencing Online Worship

Two studies initiated during 2020 began to chart the responses of religious communities to the enforced migration to online worship. The first survey, the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey, was launched at York St John University on 8 May 2020 and remained open until 23 July 2020. This survey, distributed in association with the Church Times, was designed primarily for Anglicans and attracted over 5000 responses from clergy and laity, the majority of whom identified as members of the Church of England. Various analyses of this dataset have indicated groups within the Church of England who might be more prone to give up on particular forms of worship service.

In an initial analysis of 2496 lay participants who had identified as not having been involved in the provision of lay ministry during the pandemic, Francis and VillageFootnote 8 found that while nearly two thirds (63 per cent) of women agreed that online worship is a great liturgical tool, the proportion fell to half (49 per cent) of men. While 72 per cent of women agreed that it has been good to see clergy broadcast services from their homes, the proportion fell to 59 per cent of men. This suggests men might have been more likely to abandon online worship.

In a second analysis of the same sample, Francis and VillageFootnote 9 explored the thesis that the Jungian process of judging would be important in evaluating innovation during the pandemic, distinguishing between the responses of thinking types and feeling types.Footnote 10 According to the theory, feeling types are concerned with harmony and consensus, while thinking types are concerned with analysis and critique, suggesting that thinking types would be more critical and less sympathetic in respect of issues identified by the survey. The presented data generally supported this thesis. While 65 per cent of feeling types agreed that online worship is a great liturgical tool, the proportion fell to 56 per cent of thinking types. While 76 per cent of feeling types agreed that it was good to see clergy broadcasting services from their homes, the proportion fell to 64 per cent of thinking types.

Analysis of 403 clergy in the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey indicated other groups that were less supportive of online worship.Footnote 11 While 62 per cent of Evangelical clergy agreed that online worship is a great liturgical tool, the proportion fell to 46 per cent of Anglo-Catholic clergy. While 78 per cent of Evangelical clergy agreed that it has been good to see clergy broadcast services from their homes, the proportion fell to 43 per cent of Anglo-Catholic clergy. Online communion services were a particularly difficult issue for some groups in the Church of England.Footnote 12 Data provided by 3286 laity and 1353 clergy showed significant differences between traditions within the Church in views about this central ritual. Among clergy the view that it is right for clergy to celebrate communion at home if they are broadcasting the service to others was supported by 70 per cent of Anglo-Catholics and 39 per cent of Evangelicals. Among laity this view was supported by 74 per cent of Anglo-Catholics and 56 per cent of Evangelicals. Among clergy the view that it is right for people at home to receive communion from their own bread and wine as part of an online communion service was supported by 18 per cent of Anglo-Catholics and 41 per cent of Evangelicals. Among laity this view was supported by 26 per cent of Anglo-Catholics and 62 per cent of Evangelicals.

The second study was conducted as part of the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project, an ambitious project extending across diverse faith communities, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. This project employed a mixed-method approach involving three strands, two qualitative and one quantitative. The two qualitative strands comprised 15 specific case studies and an action research group. The quantitative strand is described as ‘the largest and most detailed survey of Briton’s experience of ritual during the pandemic’. This largest and most detailed survey, available online between 21 September 2020 and 30 May 2021, gathered responses from a total of 604 religious leaders and congregants, across all faith traditions.

In their report on the findings from the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project, Edelman et al. Footnote 13 concluded that online ritual was, at best, a mixed blessing. The research identified both considerable innovation in digital worship during the pandemic, and deep-seated dissatisfaction with what had been provided. Although clearly of benefit for those with disabilities or no provision nearby, the report concluded that overall the move to online ritual had been one of loss, not gain. ‘By almost every metric, the experience of pandemic rituals has been worse than those that came before then. They are perceived as less meaningful, less communal, less spiritually effective, and so on’ (p. 7).

For church leaders, the good news from this report was the discovery of ‘a tremendous appetite for religious ritual online’ and the indication that online services are ‘particularly inviting for those who are seeking out new communication, experiences, and modes of worship’. At the same time, this report found that human connection seemed more important to congregants than technical sophistication or quality performance. Congregants seemed to be better predisposed toward participation than toward spectacle. Taking a prudential approach to the evidence, the report concluded that the future was neither online nor offline (that is, face-to-face gatherings in a church building), but hybrid.

The second core finding from the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project concerned the age effect on appreciation of online worship. Younger respondents under the age of forty had a consistently less positive experience of and attitude toward online worship than people in older age groups. The report suggested that, although those aged under forty may generally be regarded as more comfortable in the digital world, it may be that online worship is not going to be the solution for growing a younger and more diverse church.

The third core finding from the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project was that the experience was not uniform across all Christian denominations. The report singles out the Church of England for special attention. The data indicated that for the Church of England, the gaps between the experience of leaders and participants was quite marked. Worship leaders in the Church of England rated their experience of worship during the pandemic as marginally worse than before than pandemic. Worship participants in the Church of England rated their experience of worship during the pandemic as considerably worse than before the pandemic. The difference between the views of leaders and participants was considerable. On the basis of this evidence the report concluded that: ‘For whatever reason, Church of England clergy seem less aware of or attuned to the experience that their worshippers have had during the pandemic than others’ (p. 21).

The findings already published from the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey and from the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project draw attention to challenges as well as opportunities generated by the sudden migration to online worship. While online worship may have been able to simulate the experience of offline services and to sustain the commitment of established churchgoers for a short period of time during an unexpected emergency, the current body of knowledge suggests that this provision may be more vulnerable in the longer term and give rise to a new generation of church-leavers, namely those who lose interest in online worship and simply switch off.

Research Questions

Against this background the aim of the present study is to give close attention to the experiences of churchgoers engaging both with online worship and with return to socially distanced offline services in church, and to do so by taking an individual differences approach. The evidence from previous research (both concerning church-leavers and concerning experience of online worship) suggests that levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction vary in line with personal factors (both age and sex), psychological factors (personality), ecclesial factors (church tradition), and contextual factors (social location). Such factors were taken into account in designing the Covid-19 & Church-21 Survey.

In this paper we use the Covid-19 & Church-21 Survey data to address four key research questions:

-

1. What was the perceived affect response to online and socially distanced in-church services during the 2021 lockdown in the Church of England?

-

2. Why did worshippers give up online worship or attending services in church?

-

3. What individual differences were associated with giving up online worship or attending services in church?

-

4. Was there a relationship between how worshippers responded to online or offline services and whether they were likely to give up on them?

Method

Procedure

During the first and third lockdowns, online surveys were promoted through the online and paper versions of the Church Times, the main newspaper of the Church of England, as well as directly through Church of England dioceses. The second survey, named Covid-19 & Church-21, was delivered through the Qualtrics XM platform and was available from 22 January to 23 July 2021. It was designed to be used by various denominations, and the total response was 5853, of which 1862 were Anglicans living in England who completed sufficient responses to be included in the study. The current analyses are based on the group of 826 ‘non-ministering’ respondents, consisting of 800 lay people plus 26 retired clergy who were no longer licensed for ministry. Stipendiary clergy, self-supporting or retired clergy who were still active in ministry, and those in authorised lay ministries were excluded from this analysis because those with authorised or paid ministries had strong reasons not to give up on worship.

Dependent Variables

Affective Response to Online Worship and to Services in Church

The Scale of Perceived Affect Response to Online Worship (SPAROW)Footnote 14 invites participants to assess their responses to online worship against six different affect responses, three positive (energized, inspired and fulfilled) and three negative (detached, unmoved and distracted). The set of six items was introduced by the statement ‘During or after these [pre-recorded/live-streamed] services I usually felt:’ Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). Negative items were reverse coded to produce a summated rating scale measuring affect experience of online worship in the pandemic, with high scores indicating positive affect and low scores indicating negative affect. The scale was unidimensional (tested with factor analysis employing principal component extraction and varimax rotation). Village and FrancisFootnote 15 reported excellent internal consistency reliabilities (α = .90 for pre-recorded services and .91 for live-streamed services) as measured by Cronbach’s alpha.Footnote 16 This set of six items was presented separately to participants who had accessed pre-recorded services and to participants who had accessed live-streamed services, meaning that some participants completed the list twice. The items comprising SPAROW were also used to assess perceived affect response to re-emerging offline services when churches were permitted to re-open.

Giving Up on Online Worship or Services in Church

Participants were asked whether they had given up participating in online worship or given up going to church services. Responding to these two issues separately, some indicated they had given up on both. Relevant follow-up questions were then presented as Likert items with a five-point response scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). For those who indicated that they had given up participating in online worship there were four items: ‘Accessing online services was too hard’, ‘Online services do not work for me’, ‘It was too distracting to watch at home’, and ‘I went to church mainly for social contact’. For those who indicated that they had given up on going to church services there were seven items: ‘It was too complicated to book a place in church’; ‘I didn’t like socially distanced church services’; ‘Going to church kept my faith alive’; ‘No one from church bothered to contact me in the pandemic’; ‘The church has been useless in responding to the pandemic’; ‘I stopped going and found I could manage without church’; ‘I have got out of the habit of churchgoing’.

Predictor Variables

Personal Factors

Sex was coded: male (1), female (2), other (3), and prefer not to say (4). Only those who responded with the first two categories were included in the analyses. Age was coded: 18–19 (1), 20s (2), 30s (3), 40s (4), 50s (5), 60s (6), 70s (7), and 80s+ (8).

Psychological Factors

Psychological variables were assessed using the revised version of the Francis Psychological Type and Emotional Temperament Scales (FPTETS). This is a 50-item instrument comprising four sets of ten forced-choice items related to each of the four components of psychological type theory: orientation (extraversion or introversion), perceiving process (sensing or intuition), judging process (thinking or feeling), and attitude toward the outer world (judging or perceiving), and ten items related to emotional temperament (calm or volatile).Footnote 17 Previous studies have demonstrated that the parent instrument (which contains just the four psychological type scales) functions well as a measure of psychological type preferences in a range of church-related contexts.Footnote 18 In this sample, the alpha reliabilities were .84 for the EI scale, .79 for the SN scale, .74 for the TF scale, and .82 for the JP scale.

Ecclesial Factors

Church tradition was assessed using a seven-point bipolar scale labelled ‘Anglo-Catholic’ at one end and ‘Evangelical’ at the other. It is a good indicator of differences in belief and practice in the Church of EnglandFootnote 19 and was used to identify Anglo-Catholic (scoring 1-2), Broad Church (3-5) and Evangelical (6-7) respondents. In the Church of England, Anglo-Catholics tend to be liturgical traditionalists but more liberal on moral issues, while the reverse is true for Evangelicals.Footnote 20 Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical were used as dummy predictor variables. Church attendance pre-pandemic was assessed on a seven-point scale collapsed into three categories: less than seven times a year, once or twice a month, and at least weekly.

Contextual Factors

The questionnaire included a number of contextual items such as geographical location, household status, and experience of the virus. These did not prove to be significant predictors of giving up, and only one is included here. Respondents were asked how many others in various age categories lived in their household and we used a dummy variable for those with children under 13 years old as a measure of likely parenting pressures during lockdown.

Participants

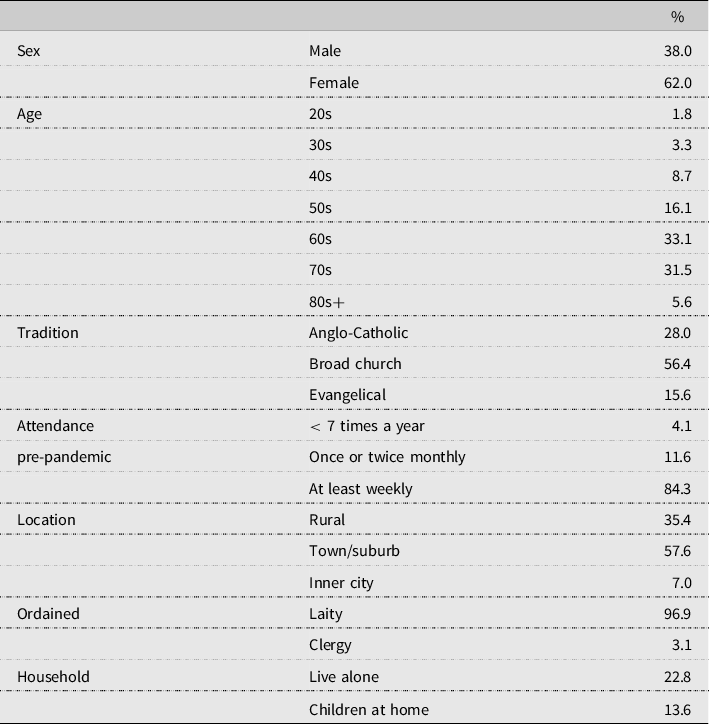

The 826 participants comprised 62 per cent women and 38 per cent men. The majority (64 per cent) were in their 60s or 70s, 3 per cent were ordained clergy, and 14 per cent had children aged under 13 years living with them (Table 1). The majority (56 per cent) self-identified as Broad Church (i.e., neither Anglo-Catholic nor Evangelical). The vast majority (84 per cent) had attended church services at least weekly prior to the pandemic. Although there are no accurate independent measures of the profile of the non-ministering Church of England members as a whole, similar surveys suggest the procedure captures a broad spectrum of the denomination.Footnote 21 There was probably an over-sampling of Anglo-Catholics, and an under-representation of younger adults and Evangelicals, which reflects the readership of the Church Times newspaper.

Table 1. Profile of non-ministering members of Church of England

Note: N = 826

Analysis

Analysis was in four stages. The first stage of analysis examined the perceived affect response to two forms of online worship (pre-recorded and live-streamed) and to re-emerging offline services in church.

The second stage of analysis examined the frequency of giving up on participating in online worship or on going to offline services in church and the responses to various reasons why this might have happened.

The third stage was to examine the frequency of giving up online worship or offline services in church among different groups within the sample. Chi-squared analysis was used to test for differences in the proportions giving up or not giving up between the sexes, different age groups, those with or without children at home, those belonging to different traditions in the Church of England, and among those with different psychological type preferences.

The fourth stage was to examine the perceived affect response scores to both online worship and offline services in church, so as to compare the scores of those who have given up online worship or offline services in church with the scores of those who had not. This was a subsample of those who had given up that was restricted to those who either accessed online services or attended church in the lockdowns, or both. Differences in mean scores were tested with t tests for independent samples.

Results

Affect Response to Online Worship and to Offline Services in Church

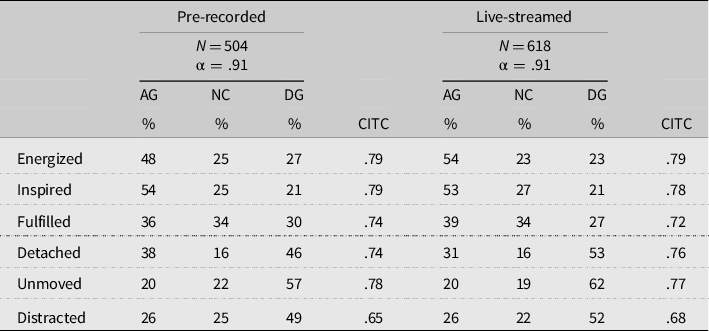

Of the 826 participants, 504 had accessed pre-recorded worship and 618 had accessed live-streamed worship. In both groups, the measure of perceived affect response (SPAROW) achieved a high level of internal consistency reliability (α = .91 in both cases). The item endorsements presented in Table 2 demonstrates a slightly less positive response to pre-recorded services than to live-streamed services. For example, 54 per cent felt energized by live-streamed services, compared with 48 per cent who felt energized by pre-recorded services.

Table 2. Scale properties of SPAROW for the two types of online worship

Note: AG = Agree; NC = Not certain; DG = Disagree; CITC = Corrected item-total correlation. α = Cronbach’s alpha

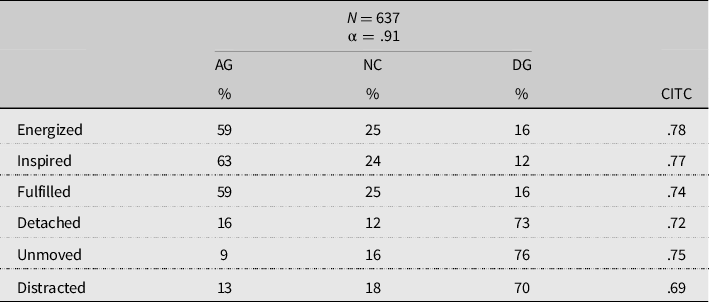

Of the 826 participants, 637 had accessed re-emerging offline services in church. The measure of perceived affect response (SPAROW) achieved a high level of internal consistency reliability (α = .91) in this context. The item endorsements presented in Table 3 demonstrate a more positive response to offline services than to online worship. For example, while 38 per cent felt detached from pre-recorded worship and 31 per cent felt detached from live-streamed worship, the proportion fell to 16 per cent who felt detached from services in church.

Table 3. Scale properties of SPAROW for re-emerging offline services in church

Note: AG = Agree; NC = Not certain; DG = Disagree; CITC = Corrected item-total correlation. α = Cronbach’s alpha

Reasons for Giving Up Online Worship or Offline Services in Church

Of the 826 people asked about giving up, 23 per cent had given up on at least one of online worship or going to church, with 15 per cent of the overall sample giving up on online worship, and 13 per cent giving up on going to church; 10 per cent had given up online worship but not church services, 8 per cent had given up church services, but not online worship, and 5 per cent had given up on both.

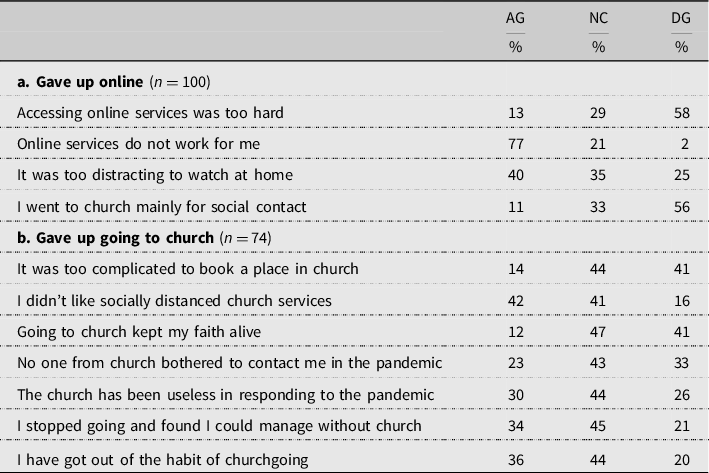

Not everyone who gave up something answered the items related to why they gave up. Of those who gave reasons for giving up on online services (N = 100), only a small minority (13 per cent) indicated that this was because they were too hard to access (Table 4a). Over three quarters (77 per cent) of this group agreed that ‘online services do not work for me’, with 40 per cent agreeing that it was too distracting to watch at home. Only 11 per cent agreed that they went to church mainly for social contact, which may have been a reason for not bothering with online worship where individual social contacts tend to be difficult or impossible.

Table 4. Reasons for giving up

Note: AG = Agree; NC = Not certain; DG = Disagree

Of those who gave reasons for giving up on church services (N =74), only 14 per cent indicated that this was because it was too complicated to book a place (Table 4b), something that was required by many churches in lockdowns. For just over two-fifths (42 per cent) it was because they disliked socially distanced services. For almost a quarter (23 per cent) it may have been a response to lack of contact from their church, and for nearly a third (30 per cent) it may have been because they were generally critical of the church response to the pandemic. Around a third indicated that they just got out of the habit of churchgoing (36 per cent) and/or found they could manage without church (34 per cent).

Predictors of Giving Up Online Worship or Offline Services in Church

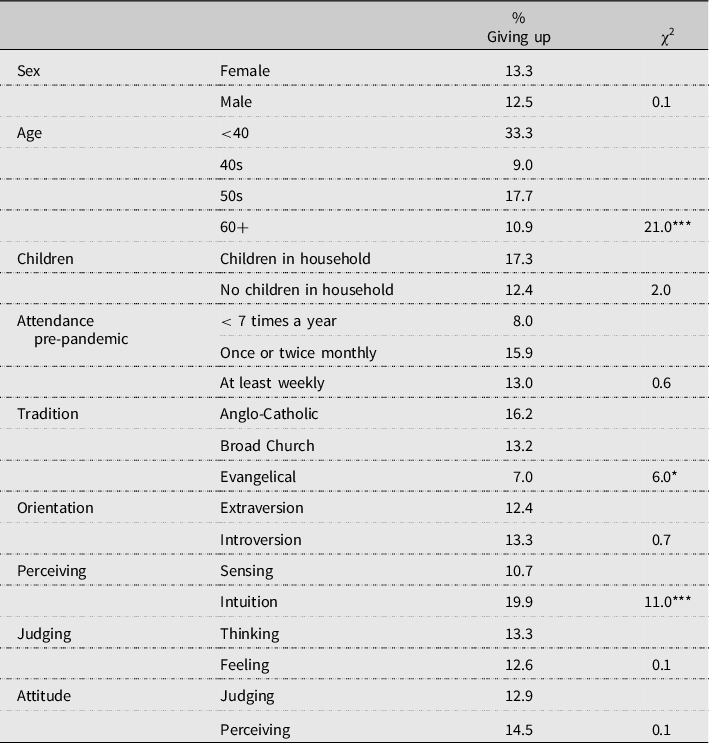

Of the 826 respondents who were asked the giving up questions, 776 had accessed online worship. Among this group, there were three statistically significant predictors of the frequency of giving up on online worship (Table 5). First, a third of those under 40 years old gave up online worship, which was twice as high as among those in their 40s or in their 60s or older. Second, Evangelicals were about half as likely to give up online worship as were the other two traditions. Third, those with a preference for intuition were twice as likely to give up online worship compared with those with a preference for sensing. There were no differences between men and women, between those with or without children at home, and in any other aspects of psychological type.

Table 5. Bivariate analysis of giving up online worship

Note: N = 776. Chi-squared based on frequencies. * p < .05; *** p < .001

Of the 826 respondents who were asked the giving up questions, 644 had attended offline socially distanced services in church. Among this group, there were again three statistically significant predictors of the frequency of giving up on such services, but these were not the same as for online worship (Table 6). First, women were more than twice as likely to give up attending offline services in church than were men. Second, extraverts were twice as likely to give up attending offline services in church than were introverts. Third, those who preferred perceiving were twice as likely to give up attending offline services in church as were those who preferred judging. Those with a preference for intuition were more likely to give up church services compared with those with a preference for sensing, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 6. Bivariate analysis of giving up offline services in church

Note: N = 644. Chi-squared based on frequencies. * p < .05

Giving Up Services in Relation to Perceived Affect Response

Of the 826 respondents, 124 (15 per cent) had given up online worship, of whom 101 (82 per cent) indicated they had accessed online worship during the third lockdown. A smaller number, 111 (13 per cent), had given up offline services in church, of whom 48 (43 per cent) indicated they had attended church during the lockdown. It seemed that it was more likely that someone would give up on church without having attended in lockdown than would give up on online worship without having accessed it.

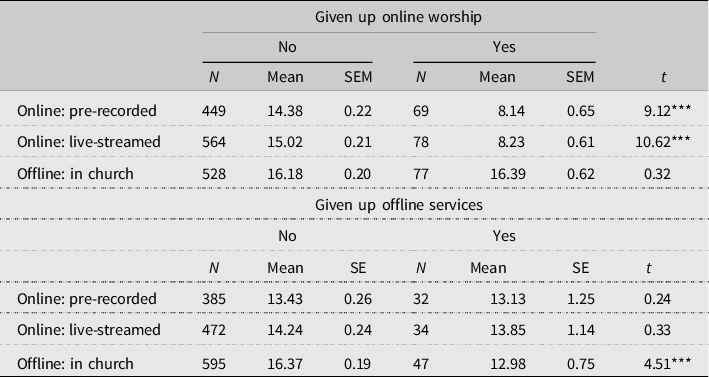

To test if levels of experience were related to giving up, it was necessary to restrict samples to those cases where people had accessed services and reported their experiences. We tested all three types of experience (pre-recorded services, live-streamed services and services in church) against both giving up online worship and giving up offline services, with a prediction that online experience would be poorer for those giving up online worship, but not for those giving up church services, and church experience would be poorer for those giving up church services, but not for those giving up online worship.

The results (Table 7) bore out these predictions: mean positive affect scores of both pre-recorded and live-streamed online services were significantly lower for those who gave up online services than among those who did not. There was no difference in online positive affect scores between those who did or did not give up church services. Similarly, the mean positive affect score for in-church services was significantly lower for those who gave up church services than among those who did not, but there was no difference in positive affect scores for either pre-recorded or live-streamed online worship. It seemed that people who experienced high negative or low positive affect when engaging services were less likely to try again.

Table 7. Mean positive affect experience scores for different services in relation to giving up

Note: Equal variances not assumed. *** p < .001

Discussion

The present study was designed to explore the impact of the pandemic on the Church of England through the responses of non-ministering members. The focus was on assessing experience of online worship and assessing experience of re-emerging services in church when they were permitted to re-open. The research questions were shaped by an individual differences approach to giving up on the Church of England in light of these experiences. The results give some indication of the extent of giving up, as well as answering our four research questions.

The base sample was from a survey completed mainly by people who were not in authorized ministries and who had been regular attenders at church prior to the pandemic. They may not have represented non-ministering affiliates of the Church of England as a whole because infrequent or casual attenders are unlikely to complete questionnaires related to church life. There was no evidence in our sample that people who infrequently attended prior to the pandemic were more likely to give up going to church during the pandemic, but samples were small in this group, and it was hard to be certain. Accepting these caveats, in this sample nearly a quarter of the participants had given up online worship, going to church, or both (23 per cent): 15 per cent had given up on online worship and 13 per cent had given up on going to church, indicating that 5 per cent had given up on both. Given that this sample was weighted towards committed attenders, these figures are likely to be minimum estimates for the Church as a whole, and clearly resonate with the news items reported by PaveleyFootnote 22 that fewer people were currently attending church services, and reported by Williams et al. Footnote 23 that the finance chair of the Archbishops’ Council was expressing anxiety regarding falling revenue. It seems that a leaner Church may emerge after the pandemic.

The first research question we posed was about the perceived affect response to online and socially distanced in-church services during the 2021 lockdown in the Church of England. The SPAROW allowed comparison of responses to pre-recorded and live-streamed online worship, and socially distanced worship in church. The results showed that in-church services were better received than online services and, for online services, live-stream worship was better received than pre-recorded services. In general, online worship was less energizing, inspiring or fulfilling than in-church worship and more distracting, more detached and less moving. This is in line with the findings of the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project Footnote 24 which also found that online worship was less spiritually effective. Online media may offer innovation and convenience, but in a post-pandemic world of hybrid worship it seems that selection might favour in-church worship. Where there are online services, live-stream seemed to offer a more positive experience than pre-recorded. This suggests that the live-streaming of in-church services, practised by some for many years, may offer the best way of developing on- and offline worship in the years ahead. Live streaming does require more investment in equipment, so it would be worth knowing who would be most likely to use such offerings.

The second research question asked about the reasons why people may have given up online or in-church worship. Only a small proportion of those who gave up online worship did so because it was too hard to access (13 per cent) or because they had previously attended church mainly for social contact (11 per cent). Most gave up because this medium just did not work for them (77 per cent), or because it was too distracting to watch at home (40 per cent). These findings give some more insight into why people in the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project concluded that, overall, the move to online ritual had been one of loss rather than gain.

Those giving up on going to services in church may have done so for two main reasons. First, the implementation of socially distanced church services was not welcome: 42 per cent of those who gave up church attendance said that they did not like socially distanced church services. This finding resonates with one of the causes for church leaving discussed by Francis and RichterFootnote 25 that they style ‘problems with change’. The notion that churchgoers can be intolerant of change is based on more than anecdotal evidence. The problem is that the pandemic forced change very quickly in a way that disrupted established patterns and expectations. Second, for some people the sudden disruption to their routine of churchgoing proved fatal. A third of those who gave up going to church said that they had got out of the habit of churchgoing (36 per cent) or that they stopped going and found they could manage without church (34 per cent). This finding resonated with a core finding from the survey conducted among church-leavers by Francis and Richter.Footnote 26 An item in that survey that received one of the highest levels of endorsement from church-leavers (69 per cent) was this: ‘I got out of the habit of going to church’. It may, then, not be a matter of surprise that locking the church door during the pandemic was successful in breaking the habit of a lifetime for so many.

The third research question examined the individual differences that were associated with giving up online worship or attending services in church. The results suggested that three factors had a part to play in predisposing people to give up online worship. The personal factor of age is significant. The age group most likely to grow weary of online worship comprised those under the age of forty. This finding resonates with the conclusions of the Social Distance, Digital Congregations Project. That report concluded that younger respondents under the age of forty had a consistently less positive experience of and attitude toward online worship.Footnote 27 It is also consistent with the finding from the Coronavirus, Church & You survey that it was the middled-aged, rather than the younger or older people who were most positive about virtual church in the first lockdown.Footnote 28 The psychological factor of the perceiving preference (sensing or intuition) was also significant. Intuitive types were twice as likely as sensing types to give up online worship. This finding resonates with findings from a study concerning congregational satisfaction and psychological type reported by Francis and Robbins.Footnote 29 In that study intuitive types reported a significantly lower score of congregational satisfaction compared with sensing types. The ecclesial factor of church tradition (distinguishing among Anglo-Catholic, Broad Church and Evangelical) is significant. Anglo-Catholics were twice as likely as Evangelicals to have given up online worship. This finding resonates with findings from the study reported by Francis and VillageFootnote 30 comparing the responses of Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy to online worship. In that study Anglo-Catholic clergy reported significantly greater discontent with the migration to online worship.

Two factors have a part to play in predicting who was most likely to give up going to services in church. The personal factor of sex is significant. Women were twice as likely to give up going to church than were men. This finding resonates with findings from the study reported by Francis and VillageFootnote 31 that compared the responses of men and women to online worship. In that study women were significantly more accepting of online worship. The implication seems to be that those more content with online worship may be more reluctant to return to offline services. Psychological factors were more important for predicting giving up going to offline services in church than for predicting giving up online worship. Three psychological factors have a part to play. First, extraverts were twice as likely as introverts to give up going to the re-emerging socially distanced services in church. For extraverts who thrive on social interaction such constraints may have been especially frustrating. Second, perceiving types were twice as likely as judging types to give up going to the re-emerging socially distanced services in church. For judging types who rely heavily on order and structure to their social lives re-engaging with the routine of offline church services may have been especially rewarding. Third, although not quite reaching statistical significance, intuitive types were almost twice as likely as sensing types to give up going to the re-emerging socially distanced services in church. This pattern is consistent with the findings of the present study on giving up online worship and with the findings of Francis and Robbins mentioned above concerning congregational satisfaction. Intuitive types may yearn for more engagement in worship than sensing types.

The fourth research question explored whether or not there was a relationship between how worshippers responded to online or offline services and whether they were likely to give up on them. There was clear evidence of such relationships for both forms of service: individuals who had experienced pre-recorded or live-streamed online worship and have then decided to give up online worship recorded significantly lower scores on the Scale of Perceived of Affect Response to Online Worship (SPAROW), but not on affective responses to offline services in church. On the other hand, individuals who had experienced re-emerging socially distanced church services and have then decided to give up going to church recorded significantly lower SPAROW scores to offline services in church, but not to online worship. These findings confirm the linkage between subjective evaluation of experience of different expressions of church or different forms of worship and the intention of participants either to persist with their engagement or to withdraw from such engagement.

Conclusion

Building on findings published from two earlier surveys concerned with the experiences of religious communities during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey and the Social Distance, Digital Congregation Project, the present study reported on the in-depth Covid-19 & Church-21 Survey, drawing data from non-ministering members of the Church of England in order to illuminate aspects of the impact of the pandemic on the future trajectory of the Church of England. Within the tradition of research concerned with church-leavers, this study focused on identifying individual differences in the motivation of those who give up on church, and in so doing distinguished between giving up online worship and giving up offline services in church.

The main finding from this study is that the Covid-19 pandemic will leave the Church of England in a weaker condition than was the case before the pandemic. Three main factors have underpinned giving up on the Church of England in the time of pandemic. First, the disruption to the regular provision of Sunday services has for some people broken the well engrained habit of church attendance. As a consequence they have got out of the habit of churchgoing, and, having stopped going they found they could ‘manage without church’, which implies it is something that is not essential to their faith. Second, when offline services in church re-emerged after the lockdown, with social distancing and other modification in provision, some people found that these changes were not to their taste. They went back to church, but neither recognized nor liked the church that now confronted them. Third, the gallant move to online worship may have met the needs and expectations of some, but for others the novelty failed to sustain commitment and they switched off. These three findings were also consistent with the cumulative evidence drawn from the two earlier surveys.

The Coronavirus, Church & You Survey was live between 8 May and 23 July 2020. The Covid-19 & Church -21 Survey was live between 22 January and 23 July 2021. Data from these two surveys placed side-by-side allow the unfolding impact of the pandemic on the Church of England to be charted. A third survey is now needed to monitor the next stage of development.