One of the more enduring assumptions about how law works (or should work) in society—held by many social scientists and citizens alike—is that legal rules announced from a “high level” (i.e., executive officials, legislatures, and courts) are thereafter simply invoked by a group of officials at a “lower level” in order to arrest, prohibit, or compel some sort of action. The liberal legalist maxim “the rule of law, not of men” is perhaps the most ancient expression of the view that laws should do the ruling—not men, women, bureaucrats, or interest groups. Of course, a significant body of work in the social sciences demonstrates that lawmakers', administrators', and citizens' aspiration for the rules to dictate enforcement action is seldom fulfilled. The reasons given for this vary.

Some argue that extralegal actors, such as business and interest groups, influence or even “capture” particular agencies (Reference BernsteinBernstein 1955; Reference BursteinBurstein 1998; Reference EisnerEisner et al. 2000; Reference KolkoKolko 1965; Reference SelznickSelznick 1949); somewhat differently, others depict enforcement as a bargaining process in which enforcement officials and extralegal actors negotiate to determine the meaning of the law and compliance (Reference Canon and JohnsonCanon & Johnson 1999; Reference HawkinsHawkins 1984; Reference Hawkins and ThomasHawkins & Thomas 1989; Reference Hall and O'TooleHall & O'Toole 2000; Reference Manning, Hawkins and ThomasManning 1989; Reference WilsonWilson 1980). In both cases, higher law and lower law fail to align because of the influence of extralegal actors on the enforcement process.

Other scholars highlight the discretion of regulatory officials in deciding what gets enforced and how enforcement takes place (Reference DiverDiver 1980; Reference HawkinsHawkins 1992, Reference Hawkins2002; Reference KaganKagan 1978; Reference LaFaveLaFave 1965; Lipsky 1980; Reference LynchLynch 1998). Such discretion permits ideological factors, operational philosophies within an agency, bureaucratic conflicts, and the career goals of officials to shape the ways rules get defined and enforced. As a result, local law departs from higher law because the discretion inherent in the enforcement process permits it.

Yet another set of arguments focus on the ambiguity of the law, emphasizing that most rules fail to specify direct instructions for their enforcement (Reference CalavitaCalavita 1998; Reference EdelmanEdelman 1990; Reference HawkinsHawkins 2002; Reference MashawMashaw 1979; Reference O'TooleO'Toole 1995; Reference Pressman and WildavskyPressman & Wildavsky 1979; Reference WasbyWasby 1976). The ambiguous nature of the law requires officials within the system to engage in “rulemaking” to determine exactly how to apply it, the effect of which is to elaborate and, in some cases, narrow the scope of the law's application.

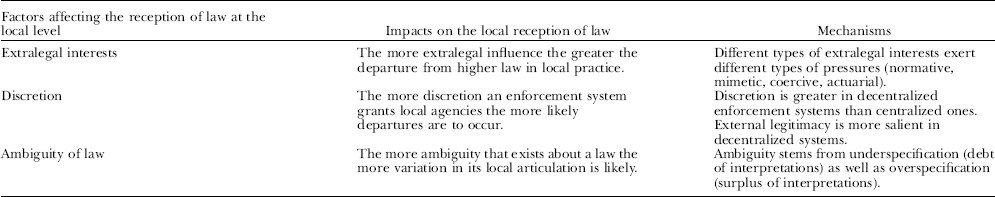

Taken together, these arguments envision the misalignment between higher law and local law as a function of extralegal actors who insert themselves into the enforcement process, the type and extent of discretion officials possess, and the degree of uncertainty that surrounds legal rules. One or more of these factors have been identified in studies of implementation in all of the major sectors of law and government, including the enforcement of energy and environmental regulations (Reference HawkinsHawkins 1984; Reference Manning, Hawkins and ThomasManning 1989), the delivery of social services (Reference LipskyLipsky 1980), the implementation of civil rights laws (Reference Conway, Grumm and WasbyConway 1981; Reference EdelmanEdelman 1992; Reference SkrentnySkrentny 1996; Reference Stewart, Grumm and WasbyStewart 1981), and the administration of criminal justice (Reference BittnerBittner 1980; Reference CicourelCicourel 1969; Reference Crank and LangworthyCrank and Langworthy 1992; Reference HawkinsHawkins 2002; Reference LynchLynch 1998; Reference SkolnickSkolnick 1966; Reference WasbyWasby 1976; Reference WilsonWilson 1968).

These studies provide the basis for a more general theoretical map for understanding the factors and processes involved when higher law becomes local law. Nonetheless, we must determine which aspects of enforcement systems affect the meaning of law at the local level, what configurations of extralegal actors and local agency discretion shape the content of a particular rule's interpretation, and how the ambiguity of law provides opportunities for circumventing or enabling implementation at the local level. Doing so requires analyzing the development of local responses within an entire field of organizations, with a particular focus on determining how the structure of that field, ambiguity, and discretion work to produce variation in the articulation of policy at the local level. Accordingly, we are less interested in explaining the specific choices any given agency makes in an effort to respond to a legislative mandateFootnote 1 and more interested in how an entire field of organizations responds to a larger public policy mandate. In other words, our unit of analysis is the field of organizations, not the law enforcement agency. How local agencies respond to new enforcement demands requires understanding the professional, bureaucratic, and political networks within which enforcement agencies are situated. In this article, we focus on the entire network of actors and organizations that have shaped how California's local law enforcement agencies are responding to the mandate to enforce hate crime laws. We use the case of hate crime policing in California law enforcement agencies to identify how extralegal influences, discretion, and statutory ambiguity affect the reception, interpretation, and ultimately the reconstitution of law at the local level.

Before proceeding, it is necessary to describe the general parameters of the arena of social life we examine in this article. The classical liberal (i.e., liberal legalist) view of law enforcement is as a hierarchically organized system where new rules are created at “central headquarters” (e.g., courts, legislatures, attorneys general's offices), broadcasted to “branch offices” (e.g., local law enforcement agencies), and then incorporated into practice among individual law enforcement agents working within local agencies (e.g., beat cops). In contrast to this imagery, we argue that law enforcement must be understood as a system in which authority and rulemaking are actually quite dispersed, both laterally and hierarchically, and where understandings of law circulate rather than move strictly from the top down.

Less abstractly, state criminal law enforcement systems in America comprise largely autonomous local agencies that have substantial discretion to define law and pursue particular enforcement agendas; yet local police departments often exhibit strong tendencies toward conformity with other peer agencies, as well as prevailing state, national, and international standards and ideals about policing.Footnote 2 The latter, what Reference CrankCrank (1994, Reference Crank2003) calls the “institutionalized myths” of policing, originate from the activities of various types of “standards-bearers.” Standards-bearers are collective actors that distill and promote conceptions of law, such as state and federal agencies, professional associations, and “leader” organizations that are understood to have “model” policies or approaches. Some of these standards-bearers are official governmental sources, and others are nonstate entities that provide information to law enforcement agencies and are thus well-positioned to influence law enforcement policy and practice.

Combined, these groups constitute what organizational sociologists call an interorganizational field. In this study, a population of organizations (i.e., local law enforcement agencies) and the key producers of meanings (i.e., standards-bearers) comprise the interorganizational field.Footnote 3 The presence of a diverse array of standards-bearers in the environment of local law enforcement agencies means that the ambiguity of law is characterized less by underspecification and more by overspecification. That is, as local law enforcement agencies implement higher law, they do so in a way that is shaped by a surplus of legal meanings that provides different models for local agencies to use. A legal surplus exists when there are multiple legitimate expressions of the same rule. This results when groups promote divergent interpretations of the law. Each expression highlights different aspects of the law, reflects the interests of its proponent(s), and offers distinct ways of envisioning the basic nature of the problem to be addressed by the law. A legal surplus also characterizes a situation in which the law itself presents alternative expressions of the rule (e.g., multiple statutes defining the same phenomena). In either case, the ambiguity of “what the law is” derives not from a debt of legal meaning but more from a surplus of possible interpretations. Under such conditions, agencies in a state criminal law system select the model they deem most desirable from a range of options. This aggregate pattern is revealed in a patchwork of definitions employed by agencies across the state.

This article is organized around eight major sections. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical considerations that shape this study. We describe the key findings of research on how extralegal interests, discretion, and the ambiguity of the law contribute to the disconnection between law-on-the-books and law-in-action, and we outline the specific social processes by which these factors are consequential for the reception of law in local settings. Next, we introduce our research site, data, and method of analysis by providing a brief overview of the history of hate crime law in California. Once the historical stage is set, we describe our sources of data and methods of analysis. Drawing on archival and interview data, we then put forward a “genealogy of law” in which we trace the development of the concept of hate crime within the national interorganizational field that comprises the institutional environment of California police and sheriff's agencies. Here our focus is on the structure of the interorganizational field of policing and the variety of legal meanings available to local agencies charged with developing hate crime policy. In the fifth section, we discuss how California police and sheriff's agencies define the concept of hate crime in their local policies. We focus on the status, conduct, and motivation provisions in hate crime policy to present findings about how hate crime law has come to be “rendered intelligible” (Reference RollinsRollins 2002:504) within California law enforcement agencies. Thereafter, we analyze the content and distribution of “model definitions” of hate crime found in local law enforcement policy. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings.

Theoretical Considerations

Research on the implementation of law is scattered across the research literatures in sociolegal studies, sociology, criminology, organizational behavior, social work, political science, and public policy; as a result, a comprehensive review of major theories and findings along these lines represents a considerable challenge that is beyond the scope of this article. Nonetheless, a recurring theme across this seemingly disparate work is the “distributed” character of lawmaking. That is, the power to determine what the law is and how it should be applied to specific circumstances is spread across legislative bodies, administrative agencies and levels, and jurisdictional units.

The structure and consequences of the distribution of lawmaking is not well-understood by most citizens and scholars working outside the substantive field of policy implementation studies. Although elected politicians, interest groups, social movement organizations, and the media are almost exclusively focused on the dynamics and drama that precede the moment when a policy proposal becomes transformed into a statute—as if it is the moment of greatest consequence—legislative enactment is really just the beginning, rather than the end, of a larger lawmaking process (Reference Hawkins and ThomasHawkins & Thomas 1989; Reference Jenness and GrattetJenness & Grattet 2001). A law enacted by a legislature or pronounced by a court inevitably undergoes a translation or filtering process as it moves down to the officials charged with applying the abstract law to concrete, “real-life” circumstances.

In describing the distributed character of lawmaking in governmental agencies, Kagan notes,

The legal decisions made by hundreds of bureaus, boards, and commissions that dot the governmental landscape, however, are rarely reviewed by courts, or reported in newspapers, or examined by scholars. Most administrators' decisions are made informally, undramatically, and deep in the recesses of bureaucracies. (1978:ix)

Recognizing this encourages sociolegal scholars to empirically document the diverse locations of lawmaking and to theorize the factors that shape the varying content of law. Drawing on multiple literatures, we highlight three factors that shape how the lawmaking process unfolds over time and across institutional and organizational domains: external interests, discretion, and the ambiguity of law.

External Interests

In any given governmental setting, policy may be shaped by the socially constructed interests of the parties involved. This is often clearest in various fields of business relations, where regulated parties contribute to both the creation of governing legal rules to which they are subject and the ways in which those rules are applied. Reference BernsteinBernstein's (1955) study of the functioning of regulatory commissions emphasizes this theme by showing how the enforcement work of commissions comes to be decoupled from higher political and legal authority and dictated by the need to make industry healthy and profitable. In Bernstein's view, commissions tend to become “captured” by the groups they seek to regulate. The theme of industry “capturing” the prevailing regulatory system also runs through Reference KolkoKolko's (1965) study of the regulation of the railroad industry. Reference SelznickSelznick (1949) uses the term cooptation to describe the close relationship between the federal policy implementation and local grassroots interests in his classic study of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Although the general idea of extralegal interests capturing enforcement has found less support recently (see Reference EisnerEisner et al. 2000), the idea that “stakeholders” contribute to the meaning-making processes that unfold within implementation remains viable. For example, Reference McCannMcCann's (1994) study of the pay equity movement reveals how employers, consultants, and reform advocates helped shape the implementation of wage discrimination remedies. Others demonstrate that outside influences are consequential under some conditions but not others. For example, Reference AndrewsAndrews' (2001) recent work on the effects of the civil rights movement in Mississippi on the implementation of federal “War on Poverty” programs shows that the influence of outside actors depends upon the leadership, organization, and resources the movement possesses, or what he terms the “movement infrastructure.”Reference HecloHeclo (1974) and Reference RosenbergRosenberg (1991), on the other hand, direct attention to state actors—i.e., bureaucratic interests and support—as a force shaping implementation.

Understanding how the interests of collective actors are manifest within a particular governmental sector and how they impact the “fleshing out” of legal rules requires a mapping of the extralegal and bureaucratic terrain to discover which actors are active within a particular domain and what sources of influence and inspiration they bring to bear on the enforcement process (Reference HeinzHeinz et al. 1993). It also requires an understanding of the characteristics of and conditions under which a given agency is open to or insulated from the influences of interested external actors. As others have demonstrated, law enforcement agencies vary in terms of the degree to which they provide opportunities for external interests to influence the organization (Reference Jenness and GrattetJenness & Grattet 2005). A considerable amount of scholarship on implementation has focused on different aspects of discretion in law enforcement systems.

Discretion

Historically, discretion has been studied at the individual level of analysis (i.e., as a property of individual decision makers). This is particularly the case in the literature on policing, which provides an important counter to the widely held assumption by some scholars (and even more citizens) that police officers rather unproblematically (and uniformly) translate law-on-the-books into action (Reference Sherman and CohnSherman 1978). Several decades of research on policing demonstrates that law enforcement does not work this way (Reference BittnerBittner 1980; Reference CalavitaCalavita 1992, Reference Calavita1998; Reference CicourelCicourel 1969; Reference LaFaveLaFave 1965; Lynch 1998; Reference SkolnickSkolnick 1966; Reference WilsonWilson 1968).Footnote 4

In the world of policing, however, discretion is not merely a characteristic of individual action, subject to the particularities of an officer's personality and background. Rather, discretion also has collective and contextual dimensions; thus it should be analyzed at both the individual and aggregate levels. As Sherman explains, “Police departments in this country vary widely in their autonomy from external control. Some police executives serve at the pleasure of a mayor, while others hold civil service tenure. Some police departments are dominated by political machines, while others are virtually independent” (1978:138). As Reference Bayley and SkolnickBayley and Skolnick (1986) reveal in their comparative study of police departments in six American cities, leaders in police departments frequently make choices about what kind of policing strategies they will emphasize in their department. These choices are often memorialized in agency policy. Policy, in turn, is “the embodiment of a set of values and assumptions located at the center of the organization” (Reference HawkinsHawkins 2002:40).Footnote 5

Police administrators are aware that individual officers' discretion contributes to a lack of uniformity in policing, so administrators routinely orient to organizational policies as a crucial point of intervention, a vehicle for standardizing officer behavior through structural change, executive orders, and the adoption of formal departmental policies (Reference Brooks, Dunham and AlpertBrooks 2001; Reference Walker and KatzWalker & Katz 2005). In other words, just as individual officers have discretion to define law, departments also make choices about what laws to enforce and how to enforce them. The primary way in which they do so is by articulating departmental policy.

In more general terms, organizational-level discretion should be seen as a byproduct of the way an interorganizational field is structured. Compared to regulatory agencies in other fields, such as federal tax law enforcement, local police departments exist within a highly decentralized system. Although the Attorney General in most states is officially empowered to oversee all aspects of the enforcement of that state's criminal law, in practice top-down directives are quite rare. As a result, individual agencies have more autonomy and more ability to fashion their own response to enforcement than other regulatory arenas. This means that the discretion individual agencies enjoy is a result of the way the entire field of criminal law enforcement is organized. In addition, the ways in which agency discretion is wielded is also a function of the ambiguity surrounding the rules to be enforced.

Ambiguity

Ambiguity results when policy makers create abstract rules designed to cover a wide array of circumstances. Such rules create a framework for rule enforcers but do not dictate specific enforcement actions. For example, Reference EdelmanEdelman and her colleagues (1990, Reference Edelman1992; Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman & Suchman 1997; Reference EdelmanEdelman et al. 1999, Reference Edelman2001) focus on ambiguity in organizational compliance with civil rights law. Many laws, but especially civil rights laws, contain ambiguous and indeterminate implications for what organizations should do as they operationalize abstract statutes in order to render them enforceable. In a context of uncertainty about what organizational response will provide protection from lawsuits, organizations often simply copy what other organizations are doing.

Law also operates via normative pressures as a cadre of professionals (e.g., human resource experts and lawyers) arises to provide authoritative interpretations of what the law covers and how the law should be constituted and enforced. Edelman illustrates the “endogeneity of legal regulation” by demonstrating the ways in which organizations help construct the meaning of law. Thus, “the meaning and content of law is determined within the social field it was designed to regulate” (Reference EdelmanEdelman et al. 1999:407). These insights suggest that law does not operate solely as a set of coercive commands that originate from lawmakers and are received by extralegal actors. Extralegal actors frequently confront law as indeterminate and, in such cases, can help construct what it means and how it should be applied.

Reference CalavitaCalavita's (1992, Reference Calavita1998) work on the enforcement of immigration law paints a similar picture. For example, she finds that the imprecision and vagueness of recent Spanish federal immigration laws allowed regional governments to develop varying approaches to immigrants seeking legal residence, work permits, and social services. The variability in regional enforcement policies has left immigrants in a precarious position, never certain of their legal status, and thus contributing to their marginalization in Spanish society (Reference CalavitaCalavita 1998).

Edelman and Calavita suggest that the ambiguity of law allows locally situated decision makers to craft novel interpretations of abstract statutes and thereby develop varying responses to statutory law. Both also see ambiguity as stemming primarily from the inherent vagueness of the law itself and the absence of clear determinate meanings of the rules. However, inherent vagueness is not the sole source of legal ambiguity. As we demonstrate below, ambiguity can also result when multiple interpretations of law exist in densely packed organizational fields. Under these structural conditions, standards-bearers compete to promote ideal models of agency policy while individual agencies decide which policy to adopt. Indeed, multiple interpretations of the law result precisely when standards-bearers operate to promote alternative standards—each with their own basis of legitimacy. Under these conditions, what we refer to as a surplus of legal meaning can influence the aggregate patterns of policy development.

Processes Influencing Legal Meaning-Making at the Local Level

The processes by which external interests, discretion, and ambiguity operate also need to be specified. Institutionalist scholarship on the sociology of organizations provides a well-known typology for cataloging such mechanisms. In their classic article on “institutional isomorphism,”Reference DiMaggio, Powell, Powell and DiMaggioDiMaggio and Powell (1983) highlight three types of social processes that generate similarity in organizational structures and practices across a population of organizations: coercive, mimetic, and normative.Footnote 6 This typology is relevant to the present inquiry and, at the same time, leaves open the possibility of discovering additional processes that influence organizational behavior and attendant policy development and design.

Coercive Processes

In general terms, a coercive process manifests when an organization adopts a policy to conform to and garner legitimacy from a higher governmental authority. Coercion operates when the Attorney General's office, a state appeals court, or another higher-ranking state agency commands conformity to a standardized approach to the implementation of a specific law or an entire body of law. It typically relies upon sanctions or inducements to influence organizational behavior at lower levels. As such, coercive processes are most common in regulatory fields characterized by a high degree of centralization and where, in terms of the factors discussed above, local agencies are granted little discretion to depart from higher-level authority. While this characterization may fit other policy implementation arenas, as argued above, it does not apply well to policing systems, where, despite the existence of the legal authority of an Attorney General to dictate local law enforcement behavior, such authority is rarely enacted.Footnote 7 Thus, we do not expect that hate crime policies among California police and sheriff's agencies result from a coercive process.

Mimetic Processes

Mimetic processes result from circumstances in which ambiguity exists and—in lieu of a clear plan-of-action—one organization simply copies the approach of another organization. Typically, the organizations engaged in the copying are, in some way, peer organizations, at least from the point of view of the organization doing the copying (i.e., the focal organization). This is done without a great deal of reflection or attempt by the focal organization to make sense of the rule or problem at hand. For this reason, the basis for mimetic processes is shared cognition; that is, an organization adopts a policy because members of its leadership believes that it is the “way it is done” for organizations such as theirs. Mimetic processes in the field of regulatory enforcement are reflected when—facing an ambiguous statute or court ruling—a local agency simply copies the implementation policy of another agency. This could be a neighboring agency with which the focal agency interacts regularly; an agency across the state that is perceived to share population characteristics or crime problems with the focal organization; an agency that has a similar organizational structure to the focal agency (i.e., what Reference Strang and MeyerStrang and Meyer (1993) call “cultural linkages”); or an organization that is perceived to be a “leading” agency, one that routinely sets the pace for agencies within a particular field or state. Given the ambiguity surrounding California hate crime statutes, we expect that many local law enforcement agencies will simply choose to mimic another agency.

Normative Processes

Normative processes are evident when organizations adopt policies that conform to legitimated standards of right and wrong, which derive from professional or social movement sources that cut across a population of organizations. Professional associations have increasingly become promoters of standards of what constitutes “best practices” in a variety of organizational settings. In the field of law enforcement, normative pressures are exerted by interested organizations such as the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), which regularly publishes model policies and provides a forum for the dissemination of technical knowledge about policing. Professional sources are also increasingly found within the government itself. In California, a major source of professional oversight of policing is the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST), which promotes professional policing practices, certifies training programs throughout the state, and produces guidelines about how to enforce the state's laws. These actors are, in the terms described above, interest groups or “stakeholders” that are external to an individual law enforcement agency but can nonetheless influence the design of its policy. Likewise, other types of organizations external to local law enforcement agencies, most notably social movement organizations, can exert normative influence. In the case of hate crime policing, community groups of all sorts, such as bias crime task forces, human rights and human relations commissions, and groups such as the Anti-Defamation League, qualify as interested parties, key stakeholders, and relevant standards-bearers. Thus, we expect normative pressures to be evident in the policies adopted by California law enforcement agencies.

Actuarial Processes

Moving away from the types of processes identified in institutionalist scholarship, we draw from the criminology and sociolegal literatures to posit a fourth type of process: actuarial. Actuarial processes are reflected when the development of policy is heavily influenced by the privileging of data collection over other organizational concerns, including following the strict “letter of the law” or conceding to the types of external influences discussed above. Actuarial thinking prioritizes the efficient management of personnel and populations based on a statistically grounded risk assessment of the problem at hand; as a result, administrators prioritize collecting aggregate statistics and performance measures about a particular problem as the key to determining how the agency should respond.Footnote 8

Reference SimonSimon argues that “the institutional fabric of society is colonized by actuarial practice” (1988:797). Thus, trends in policing are reflective of a broader growth in actuarialism in the criminal justice system and society at large.Footnote 9 The rise of actuarial practices in law enforcement has led to the displacement of other disciplinary practices related to the allocation and operation of power in society and the organizations that comprise it (compare Reference LynchLynch 1998). In policing, the older disciplinary practices are reflected in the professional knowledge about how to effectively capture criminals and prevent crime and are rooted in the assumption that behavior can be normalized through crime control policies. Actuarial practices, on the other hand, derive from the assumption that crime is relatively unpreventable and thus must be managed in a way to reduce risks and optimize collective security (Reference Feeley and SimonFeeley & Simon 1992). An actuarial mechanism is reflected in agency hate crime policies that are based upon the requirements of the data collection system, rather than the law, professional models, or social movement proposals.

Thus far, we have argued that to account for the aggregate pattern of responses of local agencies to higher law, research must consider the characteristics of the interorganizational field in terms of the three variables described above: discretion, ambiguity, and external interests. These considerations raise a series of related empirical questions. What stakeholders exist within the organizational field under study? What opportunities do these stakeholders have to influence the design of a local agency policy? Is the field composed of agencies that are susceptible to external influence by virtue of the amount of discretion they possess? Is the law sufficiently ambiguous to permit varied interpretations of how an agency should proceed? Moreover, because these factors can operate via four different types of social processes, researchers must ask, Which social processes produce conformity in local agency responses? Are they primarily coercive, mimetic, normative, actuarial, or, more likely, some combination of all four? Although these questions could be used to guide any investigation of policy implementation, in this article we apply them to an analysis of how the law enforcement field in California responds to state criminal statutes mandating the enforcement of hate crime law.

Research Site, Data, and Method of Analysis

Research Site

We chose California as the site for this research because the state legislature has been at the forefront of hate crime policymaking for the last two decades and, as a result, the State of California arguably has the most comprehensive, complex, and demanding system of hate crime laws in the nation. In addition, California accounts for nearly one-quarter of the reported hate crimes nationwide, and it has a large and vibrant community of social movement and professional groups focused on the issue. At the same time, local agencies in California exhibit variation in their responses to hate crime law that reflect the range of variation found in other states. Some agencies have responded with detailed policies that reveal considerable effort and thought, others have adopted a more minimalist approach, and many have not adopted anything. Thus, while California represents a “mature” case in terms of policy innovation, the regional diversity of the state and the variation in response of agencies within the state make the lessons drawn from California relevant to other states and the trajectories they are likely to pursue in the future.

California's legislative responses to bias-motivated violence began in the mid-1970s. The Ralph Act, passed in 1976, is a civil statute that made it possible to sue and recover damages for crimes and criminal threats aimed at persons because of their status characteristics (e.g., race, religion, ancestry) (California Penal Code § 51.7). Although it added financial penalties for bias-motivated offenses and conceptualized the sanctioned behavior that would later be called “hate crime,” it did not create a new category of crime or enhance existing sentences. As such, it represents a precursor or foundation for the hate crime laws that came later.

In 1984, the legislature declared that any felony committed or attempted “because of race, color, religion, nationality, country of origin, ancestry, or sexual orientation” would be consider “aggravated” and thus subject to penalty enhancement under the sentencing provisions of California law (California Penal Code § 1170.75). In 1987, the legislature added Civil Code § 52.1, which created an action for injunctive relief in cases of rights interference, thus further strengthening the Ralph Act. In that same year, the legislature passed California Penal Code § 422.6 and 422.7, which extended penalty enhancements from felonies to all crimes. Together, statutes 51.7, 422.6, and 422.7 were called the Bane Civil Rights Act, which reads:

No person, whether or not under the color of law, shall by force or threat of force, willfully injure, intimidate, interfere with, oppress, or threaten any other person in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him or her by the Constitution or the laws of the United States because of the other person's race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, or sexual orientation. (California Penal Code § 422.6, 1987)

These statutes constitute the backbone of California hate crime law. Prosecutors must use the definition of hate crime contained within these statutes to assess offender conduct in specific cases.

However, the definition of hate crime in California law has never been entirely fixed. Several other statutes and amendments have expanded or altered the definition of hate crime. Between 1984 and 1991, all of the state statutes were broadened to include sexual orientation, gender, disability, or some combination of the three. In 1994, an amendment specified that hate crime also includes circumstances where a perpetrator “perceives that the other has one or more of these characteristics” (Amendment State 1994 Ch. 407 § 2 [SB 1595] 1994). A perception standard broadened the circumstances in which hate crime laws could be invoked and removed from relevance any discussion of whether the victim actually belonged to the group the perpetrator was intending to target. In 1998, California Penal Code § 422.76 provided a definition of gender that was inclusive of transgendered persons. In 1999, the year following the highly publicized killing of Matthew Shepard in Wyoming, a statute that defined bias-motivated murder was added (California Penal Code § 190.03). Although murder was covered under existing law, this statute focused attention on gender, disability, and sexual orientation and omitted the other categories traditionally used in hate crime statutes. Moreover, in contrast to the existing sentence enhancement for felonies, which only allows for up to three years of additional prison time or an upgrade to aggravated murder, the new murder statute provided a specific sentence instruction—“life without the possibility of parole.”

During the 1990s, California saw statutes 422.6, 422.7, and 51.7 upheld in state appeals courts. Two cases, In Re M.S. (1995) and People v. Aishman (1995), affirmed that bias need not be the sole motivation for a hate crime; however, in the context of a crime caused by multiple motives, the bias portion must be a “substantial factor” in order for the offense to qualify as a hate crime. This clarification was explicitly added to the bias-motivated murder statute (California Penal Code § 190.03, 1999) when it was adopted, but it applied to all of the preexisting statutes as well. In Re M.S. (1995) also clarified the status of threatening speech relative to the law. The court ruled that only those threats that the perpetrator has the “apparent ability” to carry out are covered under hate crime statutes. This excluded general threatening statements about groups of people—what the court referred to as “political hyperbole.” While perhaps limiting the scope of application of the law, this ruling served to square the use of the statute with the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The California legislature articulated and affirmed yet another definition of hate crime in 2000 when it passed a law mandating the development and use of hate crime reporting forms in California schools. This law introduced a distinction between hate-motivated “incidents” and hate crime. The former are noncriminal acts such as “bigoted insults, taunts, or slurs, distributing or posting hate group literature or posters, defacing, removing, or destroying posted materials or announcements, posting or circulating demeaning jokes or leaflets” (California Penal Code § 628.1), and the latter are preexisting criminal offenses such as “threatening telephone calls, hate mail, physical assault, vandalism, cross burning, destruction of religious symbols, or fire bombings” (California Penal Code § 628.1). This delineation between hate incidents and hate crime was novel, as was inclusion of the phrasing “expression of hostility” in both definitions. With regard to the latter, no previous statutory formulation had focused on the perpetrator's subjective emotional state.

The California legislature also sought to improve the quality of hate crime policing in the late 1980s. In 1989, the state created a reporting law that defined hate crime somewhat differently than any of the statutes that came before or after. That statute, California Penal Code § 13023, defined hate crimes as

any criminal acts or attempted criminal acts to cause physical injury, emotional suffering, or property damage where there is a reasonable cause to believe that the crime was motivated, in whole or in part, by the victim's race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or physical or mental disability. (California Penal Code § 13023, 1989)

Gender and national origin were added later. Ethnicity, included here, is not used to denote ancestry or national origin elsewhere in California law. The “in whole or in part” clause, which also does not exist in any of the California criminal statutes, has been emphasized in the FBI data collection guidelines since the passage of the federal Hate Crime Statistics Act in 1990. The statute makes no mention of the “interference with rights” that is so central to all of the other statutes, replacing it instead with an emphasis on the emotional suffering of the victim. Using similar phrasing, in 1992 the legislature passed a law that mandated the development of policing guidelines and a course of instruction and training designed to enhance the ability of law enforcement officers to identify, report, and respond to hate crime (California Penal Code § 13519.6).

This very brief legislative history reveals that California lawmakers have defined hate crime in different ways. With this in mind, the data described below provide a view of how these laws have been received and interpreted by local law enforcement agencies throughout the state.

Data and Method of Analysis

To understand how California law enforcement agencies have articulated the meaning of hate crime, we gathered three types of data. First, we solicited “general orders” from all the municipal police and county sheriff's departments in the State of California. General orders are local agency policies that provide the departmental definition of hate crime and, in so doing, signal to the community in general and officers in particular what counts as a hate crime and who counts as a hate crime victim. In addition, these policies specify an agency's protocol for dealing with hate crime incidents and responding to the needs of hate crime victims. Because officers rarely consult the criminal code directly, such documents are particularly salient. As the lieutenant in charge of a bias crime unit in a large city in northern California explained, “Officers themselves generally don't deal with the penal code” (interviewed March 7, 2003). Thus, general orders form an important part of the local understanding of the law.

In 1999, and then again in 2000 and 2001, we requested the policies pertaining to hate crime from all 339 municipal police and all 58 sheriff's agencies in the State of California.Footnote 10 Given that “each municipal police department and county sheriff's department in California has been responsible for developing its own response to hate crime” (Office of the Governor 2000:21), these data were used to provide a picture of how police and sheriff's departments in California envision hate crime as both a legal concept and a community problem. Of the 397 police and sheriff's agencies in the state, 39 did not to respond to the three successive requests for policies, constituting a 90% response rate.

One hundred sixty-one (40.6%) of the police and sheriff's agencies in California informed us that they do not have a hate crime policy. Representatives from these agencies often responded to our request for a copy of their hate crime policy by explaining why they do not have a policy. They gave a variety of reasons for not having a hate crime policy, including: the lack of need for one, an administrative delay in developing a (much-needed) one, and an ability to enforce hate crime law with existing policy. Some agencies told us that hate crime policies are important and that they were in the process of developing a policy on the subject. Finally, some departments take the position that policing hate crime is important and thus requires adherence to policy, but the development of special policies for the enforcement of hate crime law is unimportant insofar as general policing procedure is all that is required.Footnote 11

One hundred ninety-seven (49.6%) of the 397 police and sheriff's agencies provided us with a copy of their policy. This proportion of agencies with policies is considerably higher than the 37.5% of law enforcement agencies that reported having a hate crime policy in Balboni and Reference Balboni and McDevittMcDevitt's work (2001:14).Footnote 12 In other words, California police and sheriff's departments are above the national average reported in the only published study documenting the prevalence of hate crime policies among law enforcement agencies in the United States. Moreover, the policies in the data set come from agencies that have jurisdiction over two-thirds of the state's population.

In terms of form, the policies for hate crime in California law enforcement agencies vary, but they contain similar components and frequently follow the same structure as policies related to other policing concerns, such as “use of force,”“high-speed pursuit,” and “how to catalogue evidence in drug scenes.” The majority of the policies begin with a “purpose” section that describes the purpose of the policy. All the policies for sheriff's departments and all but one of the policies for municipal police departments detail the official procedures officers are to follow when responding to potential hate crime, including if and how the officer must provide victim services and engage with the community as part of enforcing the law.

Most important for our analysis, the vast majority of the policies provide a definition of hate crime. While the procedures described in the policy are important, the definition is where the behavior regulated by the state laws is articulated in local terms, and, as such, it most directly expresses what the local agency thinks the law covers. Therefore, we coded these definitions along a variety of dimensions, including the specific provisions relating to the victim's status (e.g., race, religion, sexual orientation), perpetrator's conduct, perpetrator's motivation, and targeted entity (e.g., person, property, business, family), as well as the verbiage used to describe each. These components are essential to any definition of hate crime (Reference GrattetGrattet et al. 1998). Based on these dimensions, we derived “model” definitions. Agencies adhering to the same model possess definitions that substantially share conceptions of conduct, motivation, status, target, and phrasing.

More generally, the policies and the definitions of hate crime contained therein are an important venue through which local meaning-making related to hate crime occurs. First and foremost, policies serve as a critical link in the policy chain, one that connects officers with legislative mandates. They provide a communication function in the chain of command—from police chief to beat cop—that allows for the possibility of a rearticulation of the parameters of higher law into “operational” local law enforcement practice. This “operational” law is crucial insofar as policies are distributed to all frontline officers, who can be subjected to disciplinary action if they are unaware of the orders or fail to comply with the dictates detailed in the policies. Second, several analysts have argued that policies define the parameters of hate crime law and thus shape the practice of hate crime policing. For example, Reference MartinMartin (1995), Reference Balboni and McDevittBalboni and McDevitt (2001), and most recently Reference Nolan and AkiyamaNolan and Akiyama (2002), found that when a specific hate crime policy exists, officers tend to follow the guidelines closely; in some cases, policies actually “alter dramatically” what officers do (Reference Wexler and MarxWexler & Marx 1986:210). As Reference SumnerSumner concludes, “[t]he presence and structure of the policy may adequately serve as a proxy for the form the law will take on the street” (2002:5). Third, and most important given the analytic purposes of this study, policies provide an empirical window through which local meanings assigned to statutory law can be observed and documented.

To situate agency policies in a larger context and set the stage for an analysis of the development of a surplus of legal meaning and the reconstitution of law at the local level, we also collected data on other highly visible forms of hate crime policy and definitions emanating from the interorganizational field in which California law enforcement agencies reside. Specifically, we collected archival data from organizations and agencies that have developed and circulated hate crime definitions, policies, and procedures designed to facilitate awareness of bias-motivated violence, define the parameters of hate crime, and direct law enforcement agents on how best to operationalize and enforce hate crime law. As detailed in the next section, these organizations and agencies include municipalities, local associations, regional commissions, county governments, states, professional associations, social movement organizations, and bureaus of the federal government. In particular, we tracked the way each of these entities defines hate crime, when it first put forth a definition of hate crime for public consumption (usually via a publication), and how the entity's definition does or does not circulate among other players in the interorganizational field. Our empirical focus on how hate crime is defined by various stakeholders in the interorganizational field and in local policies not only goes to the heart of our larger concern with how law in general and illegal behavior in particular is constituted, but it also allows us to treat definitions external to local agencies as a source of meaning from which any given agency could have appropriated legal meaning.

These data enabled us to develop what we call a “genealogy of law” that focuses on definitions of legal constructs in particular (i.e., definitions of hate crime). That is, these data combine to provide a comprehensive empirical record of the key producers and the point of origin and destination of each and every policy and attendant definition of hate crime contained therein. As such, the policies enabled us to determine how agencies are—and in some cases are not—attentive to different sources of legal meaning. Finally, in addition to the many informal discussions we held with officers as we collected the policies, we conducted formal in-depth interviews with 13 law enforcement officials from nine law enforcement agencies throughout the state in order to understand how hate crime policies are written, circulated, and used both inside the departments and in the public realm more generally. As such, we selected interview subjects who had formal roles in creating or authorizing policies, subjects involved in policing hate crime, and a handful of rank-and-file officers to understand how they orient to the policies in the course of doing their job. Within these parameters, a convenience sample yielded an interview with a lieutenant in charge of a bias crime unit in a large city, a high-ranking training officer in charge of delivering hate crime training materials to all levels of personnel, chiefs from two mid-sized law enforcement agencies, a chief from a small law enforcement agency, a captain in a mid-sized law enforcement agency, and seven sworn officers from a variety of types of law enforcement agencies. These interviews were instructive insofar as they provided us with an insider's view of where hate crime policies originate, how hate crime policies are adopted as official agency policy, how police officers orient to policies, and how policies function within departments.

The Development of a Surplus of Legal Meaning in the Interorganizational Field

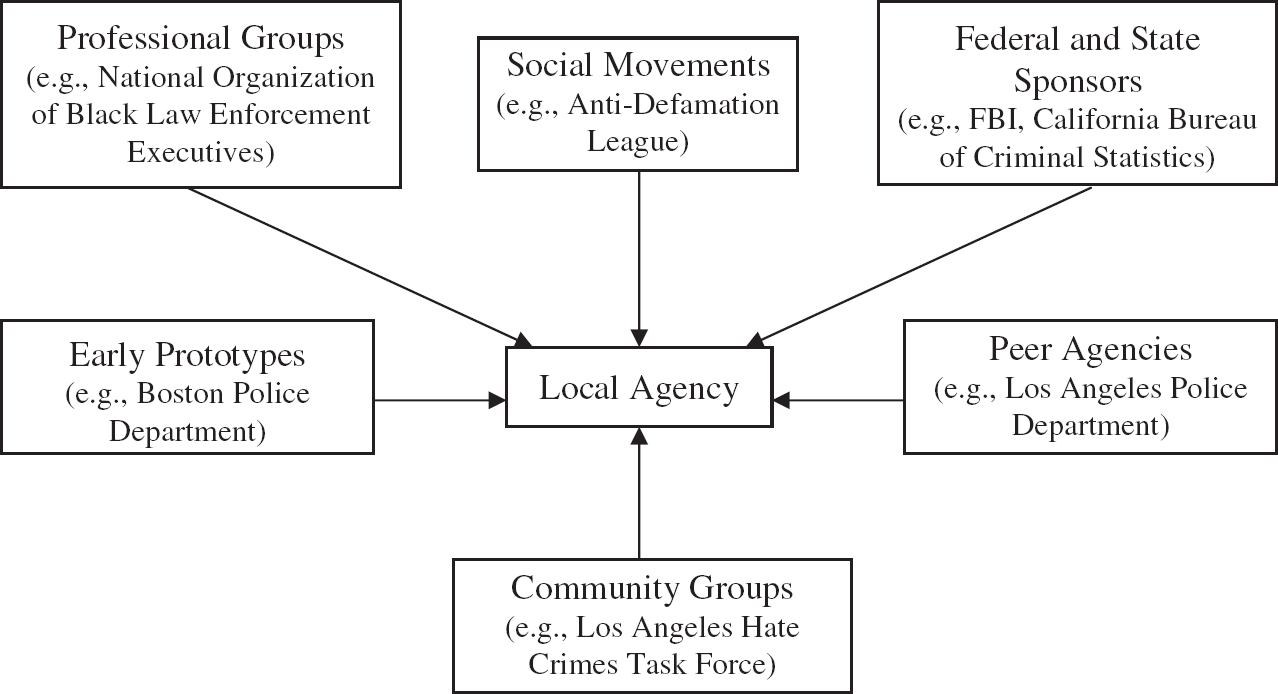

Having described the sources of data used in this study, we can now turn to a discussion of the origins and patterning of the local agencies' responses to the project of defining hate crime. Local law enforcement agencies in the United States are surrounded by an array of collective actors that supply models for policing particular kinds of problems. Other police departments, community organizations, national associations, social movements, professional groups, state agencies, and the federal government all contribute to a surplus of meaning attached to the term hate crime. Therefore, we start by describing the specific entities comprising the interorganizational field summarized in Figure 1. We do so to situate our argument about the role the structure of the interorganizational field plays in determining the reconstitution of law in local settings. Thereafter, we provide an analysis of the patterned ways in which many legal meanings circulate and mutate as they travel across time and organizational space.

Figure 1. Influences on Local Agency Policies

Early Prototypes

The history of efforts to define hate crime reveals that a handful of law enforcement agencies developed policy prior to their state passing hate crime legislation. Early conceptualizations of hate crime were presented in the policies of agencies in Boston, New York, and Maryland. For example, Boston's Community Disorders Unit developed a policy to deal with prejudice and race-based violence, referred to as “community disorders,” which includes any “conflict which disturbs the peace, and infringes upon a citizen's right to be free from violence, threats or harassment” (Boston Police 1978:1). In the early 1980s, both New York City and Baltimore County, Maryland, put forward policies with definitions of hate crime (Reference MartinMartin 1996). The New York City policy described a “bias incident” as “any offense or unlawful act based on victim's race, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation” (New York City Police Department 1984:11). During the same time period, the Baltimore County policy identified “racial, religious, and ethnic incidents” (RRE incidents) as “any criminal act which is directed at any racial, religious, or ethnic group” (Baltimore County Police Department 1985:3). While these precursors provided a foundation for action taken in California, no California agency has relied on definitions from these sources.

Community-Inspired Definitions

Moving beyond innovative law enforcement agencies that constitute leaders in the development of hate crime policy, another early source of legal meaning attached to the term hate crime is community groups. In California, for example, the Los Angeles County Hate Crime Task Force has, more than any other community group in California, shaped how hate crime has been defined by law enforcement agencies in the City of Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, and beyond. The Los Angeles County Task Force on Hate Crime was developed in 1988 in order to bring together representatives of various communities and constituencies in Los Angeles to systematically address violence directed toward minorities, develop policies for how law enforcement should respond to such events, and ensure that oversight agencies are monitoring both. The Task Force endorses a policy that defines hate crimes as “acts directed at an individual, institution, or business expressly because of race, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation” (Laguna Beach Police Department 1988, Attachment A).

Professional Definitions

Model definitions of hate crime were also developed by two professional associations: the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE) and the IACP. In 1985, NOBLE published “a recommended model of law enforcement response to incidents of racially and religiously targeted harassment and violence” (NOBLE 1985:1). From the point of view of NOBLE, “the model is designed to be an ideal, but practical approach to prevention and response” (NOBLE 1985:1). It defines hate crime as follows:

A racially or religiously targeted incident is an act or a threatened or attempted act by any person or group of persons against the person or property of another individual or groups which may in any way constitute an expression of racial or religious hostility. This includes threatening phone calls, hate mail, physical assaults, vandalism, cross burnings, firebombing and the like. (NOBLE 1985:1)

The following year, the IACP published its model policy with an identical definition of hate crime (IACP 1987). The IACP combined NOBLE's definition of RRE incidents with some of the phrasing used in Baltimore County's policy, included its own procedural guidelines, and promoted the policy as a “Model for Management.” IACP promotes this definition of hate crime to police executives across the country. NOBLE supplied the definition, while IACP provided the muscle to disseminate it.

Social Movement Organizations-Inspired Definitions

In 1998, the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith (ADL) circulated its model policy in Hate Crimes: Policies and Procedures for Law Enforcement Agencies (1988). The ADL's approach to operationalizing state law renamed RRE incidents “bias-related incidents” but retained and promoted the definition that originated from NOBLE's model policy. In the publication cited above, the ADL also helped circulate 12 other policies adopted by other law enforcement agencies throughout the United States (e.g., St. Louis; Baltimore County; Boston Police Department; Boston Metropolitan Police; Concord Police Department, California; Glendale Police Department, California; Los Angeles Police Department; Montgomery County, Maryland; New York City Police Department; San Francisco Police Department). The main function of this publication was to enable the ADL to disseminate model policies that include a standard definition of hate crime.

State-Sponsored Definitions

Finally, the interorganizational field displayed in Figure 1 contains two types of state-sponsored models and definitions: state and federal. As described above, California has, like many other states, adopted state-level hate crime laws, which provide important, but not exclusive, source material for agencies seeking to operationalize the concept of hate crime. In 1986, the Attorney General's Commission on Racial, Ethnic, Religious, and Minority Violence published a report that defined

hate violence to be any act of intimidation, harassment, physical force, or threat of physical force directed against any person, or family, or their property or advocate, motivated either in whole or in part by hostility to their real or perceived race, ethnic background, national origin, religious belief, or sexual orientation with the intention of causing fear or intimidation, or to deter the free exercise or enjoyment of any rights or privileges secured by the Constitution or the laws of the United States or the State of California, whether or not performed under the color of law. (California Attorney General's Office 1986:4)

Some of this language, in particular the last two clauses, surfaced in the 1987 Bane Act discussed above and was thus circulating in bill form at the time of the Commission's report. Nonetheless, the core of the definition—“any act of intimidation …”—was novel. In addition, the Commission's definition ultimately found a home in California Penal Code § 13519.6, a statute passed in 1992 mandating the development of a police academy curriculum on hate crime.

Also in 1986, the California Department of Justice, Bureau of Criminal Justice Statistics, proposed a slightly different definition and promoted it for inclusion in California agency policies and protocols. It defined “hate crime” as “any act or attempted act to cause physical injury, emotional suffering, or property damage which is or appears to be motivated, all or in part, by race, ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation” (California Department of Justice 1986:2). It differed from the Commission on Racial, Ethnic, Religious, and Minority Violence's definition by narrowing the focus to only reportable crimes that, strictly speaking, constitute criminal offenses. The Bureau of Criminal Justice Statistics' definition was incorporated into a 1986 state senate bill that sought to establish a hate crime reporting system for California, which subsequently passed in 1989 (California Penal Code § 13023).Footnote 13 And in 1994, POST, the agency in the California Department of Justice charged with overseeing and certifying the curriculum for the police academies and training throughout the state, employed the definition contained in California Penal Code § 13023 (which originated from the Bureau of Criminal Justice Statistics) in its “Cultural Diversity/Discrimination: Sexual Harassment and Hate Crimes” course guide (California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training 1994).

However, POST has not been entirely consistent in its support of any one definition. In 1995, POST relied upon the older Attorney General's Commission on Racial, Ethnic, Religious, and Minority Violence definition in its Guidelines for Law Enforcement's Design of Hate Crimes Policy and Training (California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training 1995), and in 2000 it changed the definition again. Hate crime became:

Any criminal act or attempted criminal act directed against a person(s), public agency, or private institution based on the victim's actual or perceived race, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disability or gender, or because the agency or institution is identified or associated with a person or group of an identifiable race, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disability or gender. Hate crime includes an act that results in injury, however slight; a verbal threat of violence that apparently can be carried out; an act that results in property damage; and property damage or other criminal acts directed against a public or private agency. (California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training 2000:26)

This definition is unique for its identification of public agencies as potential victims of hate crime.

During the same period, the federal government generated, circulated, and promoted several different definitions of hate crime. For example, in 1990, the FBI published its Hate Crime Data Collection Guidelines, according to which a hate crime is

A criminal offense committed against a person or property which is motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender's bias against a race, religion, ethnicity/national origin, or sexual orientation. (U.S. Department of Justice 1990:1)

This articulation of hate crime elaborates on the definition found in the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990 by inserting the phrase “in whole or in part” to recognize circumstances of mixed motives. The FBI publication also reports a list of procedures whereby officers can determine if a hate crime has occurred (i.e., “Objective Evidence that the Crime was Motivated by Bias”) and a list of key terms with attendant definitions (i.e., bias, bias crime, bisexual, ethnicity, heterosexual, homosexual, etc.). These procedures and terms now appear in local law enforcement agencies' policies.Footnote 14

The genealogy of law presented thus far reveals that agencies wanting to create a hate crime policy confront a situation in which many options are available. That is, a surplus of legal meaning is attached to the term hate crime, and contributors to that surplus come in various forms (see Figure 1). State law provides one source for defining hate crime, but other viable definitions are available from official governmental sources, such as the FBI; yet other definitions of hate crime are promoted by professional, social movement, and community groups. No doubt, this environment possesses ambiguity about which kind of policy is best. Notably, however, the ambiguity does not result from just the inherent vagueness of the statutes alone; instead, the situation is filled with ambiguity because there are so many ways of defining hate crime from a variety of legitimate sources. This is the environment local law enforcement agencies in California face as they develop a policy on hate crime enforcement. Therefore, the next question is: what kinds of policies do agencies across an organizational field develop in the context of this surplus of law? And related, what influences the adoption of some types of policy and not others?

Characteristics of Hate Crime Policies

Our analysis of local policy reveals immense variation in the definitions of hate crime found in local law enforcement agencies' policies. This variation is apparent via an examination of how hate crime policy (1) recognizes some status provisions and not others, (2) circumscribes conduct that qualifies, and (3) identifies the elements of motivation required for the law to be invoked.

Status Provisions

The definitions of hate crime vary in the policies in terms of the categories of persons covered—what we refer to as its “status provisions.” Status provisions such as race, religion, ethnicity, ancestry, sexual orientation, gender, disability, and so on implicitly reference what Reference Earl and SouleEarl and Soule (2001) refer to as “target groups.” That is, race is a proxy for nonwhites, religion is a proxy for non-Christians, sexual orientation is a proxy for gays and lesbians, gender is a proxy for girls and women, and so on. Given this, some axes of discrimination and minorities are highlighted while others are rendered invisible.

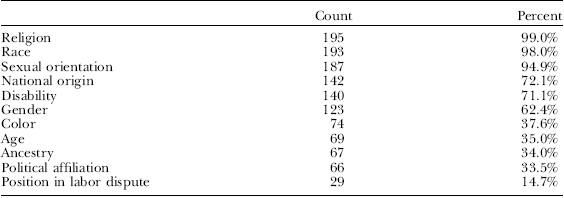

As Table 1 shows, the most frequently included status provisions in law enforcement hate crime policies are race, religion, and sexual orientation. More than 90% of definitions reference these groups. The next most frequently used status provisions are disability and gender, as well as some of the alternative ways of referencing race and ethnicity. These are included in roughly two-thirds of the policies. The least frequently included categories are age, political affiliation, and position in a labor dispute.

Table 1. Distribution of Status Provisions in Local Law Enforcement Polices in California

Note: Percentages are based upon the total number of agencies that have orders (n=197).

As a result of the differential inclusion of status provisions, some agencies are comparatively inclusive in their approach to defining hate crime (i.e., they recognize many or all of the provisions included in California criminal and civil statutes) and others are comparatively exclusive (i.e., they omit categories present in the law). The selective use of status provisions means that some agencies do not explicitly recognize some acts as hate crime in their policy. For example, when gender or disability is not included, officers are not made aware or reminded that those categories are also part of the law. This might play a role in the underreporting of hate crime incidents and the underenforcement of hate crime law.

Conduct

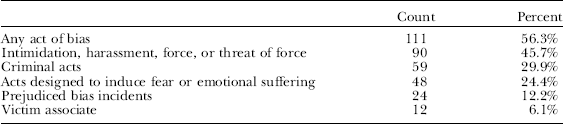

As Table 2 reveals, the policies also vary in terms of the conduct they describe as covered by hate crime law. One hundred eleven agencies (56%) have policies that describe the scope of activities that officers must respond to as “any act of bias,” whether criminal or not. This extremely broad focus is frequently accompanied by a purposeful delineation between hate crimes and hate incidents, but other times it is not. An officer in a Professional Standards unit reported in an interview that his department wanted officers to track and respond to noncriminal incidents involving bias because such incidents can escalate into criminal offenses at a later point and because identification of potential “hot spots” of bias-related activity can help officers correctly classify subsequent cases. However, such a broad definition of the behavior clearly goes beyond what the criminal statutes require.

Table 2. Distribution of Conduct Provisions in Local Law Enforcement Policies in California

Note: Percentages are based upon the total number of agencies that have orders (n=197).

In addition, 48 agencies (24%) use definitions that include broad terms, such as “acts designed to frighten or produce emotional suffering,” to describe the conduct involved in hate crime. Again, some of these acts may be criminal, others may not. The wording of this definition might encourage officers to focus on the victim's emotional reaction to an incident as a key consideration in whether to classify an incident as a hate crime. Moreover, “emotional suffering” does not necessarily encompass criminal acts. In other words, an act may cause emotional suffering and not be criminal.

Ninety agencies (46%) use the phrase intimidation, harassment, or threat of force, which is accurate relative to the criminal statutes (California Penal Code § 422.6 and 422.7, 1987). However, unless an officer happens to know that the California courts have ruled that this portion of the law does not apply to all incidents of verbal intimidation, harassment, or threats, but only to “true threats” (see In Re M.S. 1995), the officer might be led to classify as hate crime acts that do not meet that strict requirement of the statutes. Twenty-four agencies (12%) use the broad concept of “prejudice-based incidents,” which is further defined as “violence or intimidation by threat of violence against the person or property of another.” A handful of other policies highlight particular examples, such as firebombing and crossburning. To the extent that these policies invoke a set of stereotypical hate crime scenarios (Reference Levin and McDevittLevin & McDevitt 2002), they serve to narrow officers' understanding of when the category of hate crime is applicable. For example, less-stereotypical types of hate crime, such as those based on disability or gender, are less likely classified as hate crime. Thus, the core conduct to which officers are being directed to respond is different across agencies.

As is the case with status provisions, some of these conduct descriptions are overinclusive relative to the state statutes, and others are underinclusive. Thus, if the policies were followed closely, we would expect to see variation in terms of the types of incidents that are classified as hate crime.

Motivation

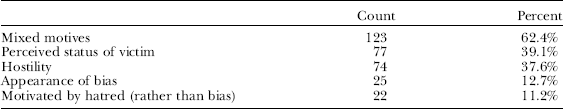

The definitions also vary in the way motivations are depicted (see Table 3). All of the policies define hate crime in ways that direct officers to assess certain mental states. One hundred and twenty-three agencies (62%) use definitions that explicitly direct officers to recognize circumstances involving “mixed motives” as a hate crime. When an agency's definition of hate crime includes acts motivated “in whole or in part” by bias, it is explicitly instructing officers not to dismiss a case as a hate crime just because there may be other motives for the incident. Such phrasing also does not require bias to be the “primary” motivation for the crime. Nor does it indicate a “but for” standard (i.e., but for the element of bias the crime would not have happened), which is used in some departments (Reference BoydBoyd et al. 1996). The criminal hate crime statutes, California Penal Codes 422.6 and 422.7 (1987), do not contain any language that specifies how to proceed in cases with mixed motives. The earliest use of the “in whole or in part” phrase in California is in the 1986 publication by the Attorney General's Commission on Racial, Ethnic, Religious, and Minority Violence. It also surfaced in the federal Hate Crime Statistics Act and was subsequently included in FBI data collection guidelines regarding hate crime.

Table 3. Distribution of Motivation Provisions in Local Law Enforcement Policies in California

Note: Percentages are based upon the total number of agencies that have orders (n=197).

Seventy-seven agencies (39%) use policy to signal to officers that the actual status of the victim is not a factor that should exclude an act from being classified as a hate crime. That is, acts in which the offender wrongly perceives the status of the victim still count as hate crime. Seventy-four agencies (38%) instruct their officers that hostility is a component of motivation that needs to be present. This consideration requires officers to make a deeper assessment of the perpetrator's mental state (i.e., identifying the presence of hostility), which is not a determination required in policies that rely on “motivated by” or “because of” criteria. Twenty-five agencies (13%) explicitly direct their officers to classify as hate crime any crime that has the “appearance of bias,” which goes well beyond any state statutes. Twenty-two policies (11%) indicate that hatred, rather than bias, is what an officer should use to determine whether a hate crime has occurred. Bias is a broader way of describing motive because one does not have to possess hatred in order to be biased. Officers using a hatred standard might reject incidents involving bias, but not hatred.

Commensurate with our findings related to variation in status provisions and conduct descriptions, the motivational elements of local policy provide another opportunity for the meaning of the law to be reconstituted. The phrasing attached to “motivation” can sometimes expand the reach of the law, and in other instances it can restrict it. For example, requiring hostility narrows the applicability of the law, while “appearance of bias” implies a broader range of applications (for more along these lines, see Reference Jenness and GrattetJenness & Grattet 2001).

Taking these findings as a whole, a picture of what hate crime means for California law enforcement agencies emerges. Hate crimes are most typically envisioned as “any act” committed because of “race, religion, or sexual orientation” regardless of “mixed motives.” In other words, it is in these terms that hate crime is most consistently defined in the state. Nonetheless, homogenization around this definition is far from complete; a sizeable number of agencies have yet to agree on the core parameters of hate crime.

Model Definitions of Hate Crime

Despite the patterns of variation described above, commonalities do emerge across agencies. Of the 197 agencies that have written policies, 176 (90%) rely on one of eight definitional models (see Table 4 for an inventory of these model policies). All but one of the models—the definition first used in the Ridgeview Police DepartmentFootnote 15—were traced to sources in our genealogy of law. Accordingly, each model was available in the interorganizational field and was a candidate for adoption by any given California law enforcement agency. Nineteen agencies (10%) created their own “anomalous” definition, and two agencies have policies that do not define hate crime. Thus, most agencies rely on a definition created somewhere else or by someone else. This is significant evidence that agencies do not exercise their autonomy in purely particularistic ways. Rather, how an agency selects a definition is a product of several different kinds of processes. To understand the role these influences play in policy design requires a closer examination of the content of definitions of hate crime found in policies that gain enough traction in the interorganizational field to be copied by a handful of agencies—what we call “model policies.” By model we do not mean to imply preferable or ideal; rather, we merely mean to imply that the policy type was replicated across the organizational field.

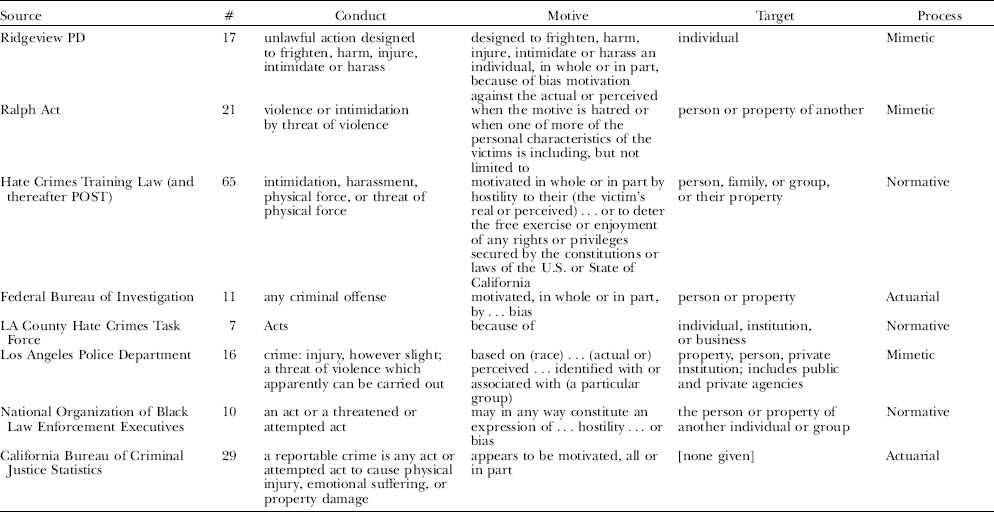

Table 4. Model Definitions of Hate Crime in California Law Enforcement Agencies' General Orders

Note: Nineteen agencies created their own “anomalous” definition of hate crime and two agencies did not include a definition of hate crime in their policy.

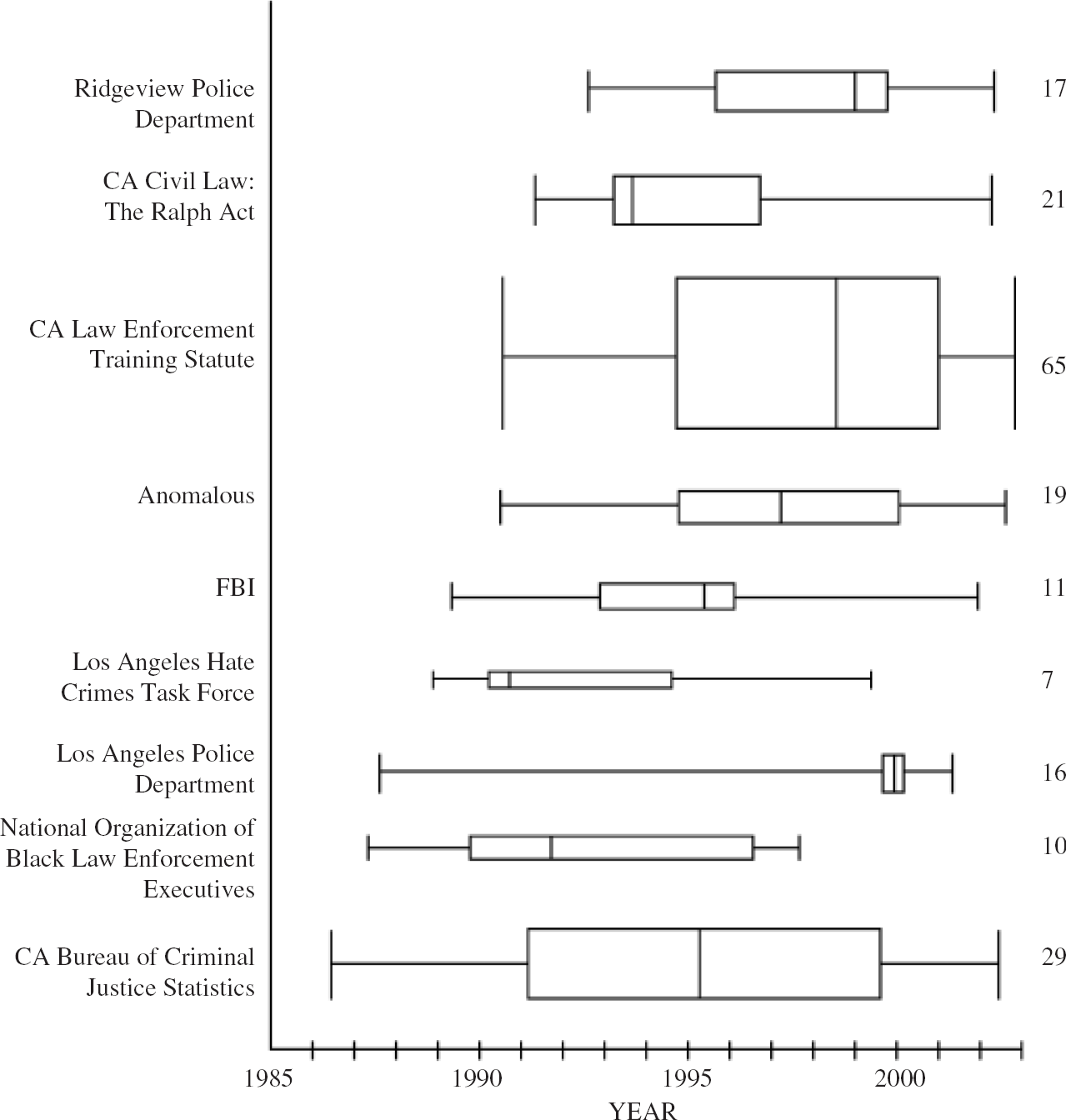

Figure 2 presents box plots of the timing of adoption of each model. The height of each box plot reflects the number of adherents, which is also given in the right column of the figure. Moving from left to right, the vertical lines on the box plot represent the following thresholds on the distribution for each model definition: the timing of the first adopter, the 25th percentile, the median, the 75th percentile, and the last adopter. As such, the figure provides an image of the temporal distribution of each model definition. Some of these models tended to be adopted in the late 1980s and early 1990s; others tended to be adopted later. With 65 adherents (33%), the most common approach is to use the definition of hate crime contained in the California Law Enforcement Training statute (California Penal Code § 13519.6, 1992). In fact, 28 of the 65 policies were written by a single Southern California attorney and then sold to agencies. This “boilerplate” approach to policy design has resulted in the development and circulation of a single policy among some California agencies. These policies, bearing the label “338” on the top left-hand corner of the policy, represent an “off-the-shelf” solution sold to agencies that chose to purchase a policy that promises to withstand litigation, rather than develop their own.

Figure 2. Boxplot of Model Definitions of Hate Crime Found in California Law Enforcement Agencies Policies

Other model definitions derive from the sources summarized in Figure 2. Twenty-nine agencies (14%) use the language contained in the hate crime reporting law (California Penal Code § 13023, 1989), which ultimately originated in the California Bureau of Criminal Justice Statistics. Twenty-one agencies (11%) use the wording of the Ralph Act—the law that creates remedies for victims of criminal civil rights violations (California Penal Code § 51.7, 1976). Seventeen agencies (9%) employ a definition that was first used by the Ridgeview Police Department in 1993. Sixteen agencies (8%) rely on a definition that originated in the Los Angeles Police Department. Eleven agencies use the FBI definition. Ten agencies (5%) use the NOBLE model policy, which was also promoted by the IACP and the ADL. Finally, seven agencies (4%) use the definition provided by the Los Angeles County Hate Crimes Task Force.

Even when an agency has conformed to a model definition, it may add or subtract wording. Most of the 65 agencies that use the California Law Enforcement Training statute, including those that purchased the 338s, have modified the definition in small ways. Sometimes words are added or omitted in order to tailor the model to the specific needs of the agency. Other times, fragments of text added by one agency are copied into the policy of another. Akin to a genetic mutation, alterations to definitions are then replicated by subsequent agencies that may themselves add or subtract text. Mutations then compound over successive generations, even while core parts of the definition remain unchanged. The result is that agencies have policies that are standardized in important ways but also contain differences. For example, some of the agencies that use the FBI definition of hate crime added the sentence “The Department of Justice of the State of California also includes as hate or bias crimes those offenses motivated by the offender's bias against persons with a physical or mental disability.” This phrase was then replicated by several other agencies. Although wording differences might seem trivial, such changes can affect the definition of hate crime expressed in the policy. In this case, strict adherence to the FBI definition has the effect of narrowing the definition of hate crime by omitting disability-based offenses.