1.1 Introduction

At the beginning of the eighth century, the old Visigoth kingdom was in social and political crisis. Consequently, it collapsed easily under the expansion of the Muslims after they crossed the Straits of Gibraltar in 711. The collapse of the monarchy left power in the hands of the local elites and ecclesiastic hierarchy of the cities. The scant interest of the Muslims in the rugged northern lands and the Carolingian intervention in the north-east of the Peninsula facilitated the rise of Christian kingdoms and counties, separated by the frontier. This was a territorial strip, which immediately served as a stimulus to precipitate the internal processes of both societies, and which thus had a strong impact on economic evolution and articulation.

South of this frontier the lands were in the cultural and economic framework of the Muslim Mediterranean with shared links as far as the Middle East. This relation was maintained despite the political split, because in 756 al-Andalus became an Umayyad emirate separate from the Abbasid caliphate, and in 929 it was turned into a caliphate. Reference Ibn, Hawqal, Kramers and WietIbn Hawqal (1964) testified to the strong artisanal and commercial prosperity reached then, just when the Andalusian capital, Córdoba, occupied a position only surpassed by Baghdad and Byzantium. This, however, did not give enough cohesion to the multi-ethnic Islamic society of al-Andalus, which entered into crisis on the turn of the tenth to the eleventh centuries, to the extent that it was about to collapse and split into small kingdoms centred on their respective urban capitals ruled by ethnically cohesive lineages, the so-called taifas or petty kingdoms.

This scenario was one of weakness compared to the Christian kingdoms established on the northern side, where the aristocracy and the ecclesiastic hierarchy had consolidated their domains over territories seized on the frontier where, especially from the eleventh century on, feudalism linked lords, peasantry and land, while prominent urban centres, well communicated commercially, were gaining ground. The northern economy came to be identified with an expansive dynamic, precisely justified by the ideological discourse that supplied the political will to religious arguments to delegitimize the Muslim presence. The frontier stopped being a strip of land to become a line that the northern kingdoms gradually pushed southwards with the aim of gaining new domains. Al-Andalus could do little more than trust in its renewal from the African empires, first the Almoravid, before the end of the eleventh century, and, from the mid-twelfth century, the Almohad, which was definitively defeated in 1212, however. Thus, by the end of the twelfth century, the Christian kingdoms in the north had taken the lead, not only to occupy most of the territory of the Peninsula but had also stabilized rural and urban, feudal and bourgeois societies, well prepared to face the imminent late Middle Ages.

1.2 Hispania Under Muslim Rule

Several challenges opened up for the economy after the Islamic occupation of the Iberian Peninsula. First, the settlement of a new population, in general repeating its tribal and traditional structure and, in many cases, combining with respect for the native population (‘Muwallads’), implied changes in the tenure and exploitation of agricultural systems. Second, the consolidation of cities and towns, so typical of Muslim culture, would facilitate the action of the urban elites over the surrounding rural environment, interfering in such aspects as property and production. Third, urban production would lead to important trade routes, which connected al-Andalus, maintaining strong relations with Muslim lands on the other side of the Mediterranean, as well as stimulating specific relations with northern lands. This way, the bulk of the rich Roman (Visigoth) urban and commercial network continued under the new rulers and in the new Mediterranean scenario. The southern half of Iberia was closer to the contemporary patterns of development in the Middle East and Byzantium than to its northern neighbours in the Frankish dominated areas. Most of its commercial activities were related preferably to Mediterranean-based networks that spread from Misr (Egypt) and al-Sham (Syria), but also from Iraq and eastern Islam, at least from the point of view of technological and intellectual transfers. At the same time, the close relation between state structure and economic development led to an economic scenario marked by monetary consolidation, economic policies and urban development.

1.2.1 State and Consolidation of a Monetary Economy

From the mid-eighth century, the emirs of al-Andalus minted silver coins (dirhams), although without their names on them. The supply fluctuated: they became scarce in moments of turmoil, like the mid-eighth century coinciding with the great Berber uprising, or in the late eighth and early ninth centuries (the early years of Emir al-Hakam I); while, in contrast, they were much more common at times of economic growth, as in the second quarter of the ninth century (the reign of Abd-al Rahman II). During the periods of absence of a mint, coins would enter al-Andalus from the east and Maghreb through exports of agricultural goods and minerals. Praise is not spared for the consequences, both political and economic, of the creation of the mint generating widespread prosperity and encouraging the trade in luxury goods.

The coherence between the state and the authority of the emir was strongly compromised by internal upheaval and the victory of regional dynasties (duwal). Some of these clearly clashed with Umayyad rule; others negotiated a sort of symbolic acknowledgment of their authority. In every case, tax flows stopped, which may account for the data concerning coinage in this period. Very little survives from 272–285 AH (885–898 CE), corresponding to the reign of al-Mundhir and the early stages of ‘Abdallah. Almost nothing remains (two examples from 293 AH/906 CE) from 285 to 316 AH (898–928 CE). Some of this information should be updated taking into consideration Alberto Canto’s data (Reference Canto García and SénacCanto, 2012). A drop in the activity of the mint may thus be seen as a result of a political crisis, lack of power and centrality from the emir with consequences for the state of economy. The result of this state of affairs in urban life can be observed during Ordoño II’s attack on the medium-sized city of Évora (912 CE), seized by surprise thanks to the poor state and lack of repair of its walls.

In 316 AH/928–929 CE, Abderraman III defeated the rebel Banu Hafsun in Bobastro, assumed the minting of gold coinage (dinar) and proclaimed the caliphate. Minting gold coins was a caliphal prerogative, in concordance with the Roman assimilation of minting gold with imperial munus. The adoption of the title of caliph formed part of the competition between the Umayyads in al-Andalus and Fatimids in northern Africa’s Kayrawan. Such competition was political but also for markets and control of the gold trade, Andalusian links to the Maghreb already being notable in the ninth century during the emirate of ‘Abd al-Rahman II. Minting was then linked to the economic recovery, overcoming the serious problems that had persisted since the emirate of Al-Mundhir, from the late ninth century, until 928. The issuance of gold coinage brought numerous gains. According to Ibn Hawqal’s testimony, while the caliphate of Kayrawan collected between 700,000 and 800,000 dinars annually through different taxes, in al-Andalus, only the rent from the mint would supply an annual income of 200,000 dinars (gold) or 3,400,000 dirhams (silver), using a conversion rate of 1/17 that was probably too high (Reference Ibn, Hawqal, Kramers and WietIbn Hawqal, 1964: I, 94–95, 107).

The minting of gold coinage continued in Córdoba during the following 20 years before the transfer of the capital (and the mint) to the one newly built at Madina al-Zahra according to the eastern Abbasid models. In these years, the great increase in the amount of silver delivered to the mint is noticeable (from 316 to 336 AH/928–948 CE a variable number of surviving coins is registered, but this rises to 106 coins in 331 AH/943 CE). The huge investment implied by the construction and establishment in al-Zahra of a costly court society required large-scale minting of both gold and silver, the first represented by up to 24 surviving examples from 336 to 364 AH, and the latter also by high levels of coinage in the same period. Stability seems to describe the altogether brief al-Zahra period until the end of the reign of al-Hakam II. A change in the regime followed, with the minister (hadjib) al-Mansur taking power. In spite of this, nothing substantial seems to have changed from an economic point of view. The minting of silver coins characterizes the period of the economic recovery from 366 AH (976–977 CE) and that affected the last years of al-Hakam and then the caliphate of Hisham, particularly after 378 AH/988 CE. Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Amir’s ability to benefit from war with northern Christian kingdoms and the revenues brought to the state from booty and putting captives on the market, may account for the last moments of economic splendour before another major political crisis.

The great turmoil (Fitna) that led to the disintegration of the Umayyad caliphate (1009–1031) was accompanied by a severe fall in coinage, clearly perceived after 403 AH/1012 CE. The taifa regime based on the urban economy and local power followed the path of the caliphal state, in this respect as in many others. The mint, promoted by the new taifa kingdoms, acted as a show of power and a form of appropriation of Umayyad ideology. At the same time, it was a sign of the economic prosperity of al-Andalus in the eleventh century while it financed both investments in luxury goods and court society. Finally, it was the vehicle for a policy of buying truce vis-a-vis the rising northern Christian kingdoms, now much more aggressive, through the payment of tributes (parias), which became very high.

The major transformation in the eleventh century was a result of a political and religious event external to al-Andalus but with huge impact on Andalusian society. The rise of the maliki Berber Almoravid empire allowed integration into an economic network that controlled the continuous flux of gold from Timbuktu. That allowed a stimulation of the economy of al-Andalus, which had been exhausted under the pressure of the Christians kingdoms to the north, including strict fiscal policy required to be able to meet the payment of the parias. At the same time, the conquest of al-Andalus by an empire based in the Maghreb allowed monetary integration at a level never experienced before, in spite of the existing interdependence of both economies. The impact of North-African gold on the economy of Iberia (and not only al-Andalus), probably pre-dates the Almoravid conquest (in 1091, the conquest of Seville) as may be observed through documents from the frontier region of Coimbra, although it is not clear that all the early references to ‘morabitinos’ in the Christian area refer to Almoravid coinage (Reference Menéndez Pidal, Lapesa, García and SecoMenéndez Pidal et al., 2003). The fact that not until the eleventh century did the Christian kings begin to issue their own currency helped to establish Andalusian money, either minted in al-Andalus or later on in the Maghreb, as the key element in the Iberian economy. Even more so because the Almohad conquest in the mid-twelfth was accompanied by the takeover of the Almoravid dinar, which the Almohads adopted, changing very little in this respect (dobra, masmudi), and which were in circulation in Iberia together with the currency issued by the Christian kings in line with Islamic models. The fact that all these coins tended to circulate somewhat indistinctly make it hard to picture the actual provenance of such treasures as that amassed by the second Portuguese king Sancho I (d. 1211), mainly through a war economy, which amounted to 720,200 ‘morabitinos’ (Almoravid dinars?, dobras?), 195 gold marks and 4.5 ounces of gold and 1400 silver marks.

The Berber empire’s control of the gold supply enabled them to create an economic area in the western Mediterranean ruled with the double monetary pattern of gold/silver (dinar/dirham), in which gold coinage played a decisive role, fuelling both the dynamic Andalusian urban-based economy and the growth of Christian northern Iberia, even if a significant part of the transactions in that region were still not monetized. Its decline in the thirteenth century was a direct result of the crisis of the Almohad empire and stressed the close connection between state building and the monetary economy, always usual in al-Andalus.

1.2.2 Economic Policies

The role of the state and its impact on the medieval Andalusian economy may be asserted not only by taking minting activity as a measure of the evolution of the economy but also by observing the impact of public expenditure, taxation and market regulation.

An important motor for economic growth in tributary Islamic society was the policy of propaganda through a pattern of luxury consumption and a building programme. This can be appreciated when the court of ’Abd al-Rahman II hosted the singer and trendsetter Ziryab freshly arrived from Baghdad in or just after 822. The amounts given to him in dinars (directly and in rents) and in kind (palace, properties, goods, enslaved people and servants), as well as the focus on his impact on collective mores, material culture and patterns of consumption, show al-Andalus as a rich society closely connected by taste and refinement with the Abbasid east, then at its peak.

The construction of the new complex of Madinat al-Zahra, west of Córdoba between 937 and 961, brought the splendours of Byzantine and Abbasid palaces to the Iberian Peninsula. Before the end of that century, the palaces of the court aristocracy were added, along with the enlargement of the Aljama mosque, all under al-Hakam II, and the construction of a second courtly city, al-Madina al-Zahira, under the Amirids. Al-Makkari, quoting Ibn Ḥayyān, mentions a cost of 300,000 dinars per year, for a total sum of 7.5 million dinars (Reference MakkariMakkari,1840–1843: II, 187ff). The caliph reserved a third of its annual revenue from the treasure for the construction site, a sum that can easily match the investment by the emperor Justinian in the Hagia Sophia, four centuries earlier. This was made possible by a huge increase of the state’s revenues during the tenth century. This denotes the good state of the economy, as well as a model of society that promoted specialized work as it supported a court of luxury and consumer goods.

The ideological and economic impact of Madina al-Zahara became the model followed by the taifa kings in the eleventh century. The latter reproduced on their own scale the magnificence of the palaces and the ostentation of the royal courts as a base for their power. This can be seen both in the large capitals, like Seville, Zaragoza, Málaga or Granada, and in the lesser ones. Even the kings of Lleida had a second palace built in the nearby town of Balaguer that condensed the best the artists of the time knew how to do. All together it reflects an urban setting conducive for developing a rich material culture, with the production and dealing in silk fabrics, rugs, glazed pottery and ivory items, among others. Later, during the twelfth century, the Berber empires, especially the Almohads, also financed relevant construction programs in al-Andalus. In the late twelfth century, in their capital of Seville, the latter completely restructured the palace and the city around it, which required a heavy tax burden.

Flaunting power through building requires fiscal power. The Muslim territory was always a tributary state. The first wali (governor), ‘Abd al-Aziz, negotiated advantageous conditions for the surrender of the Visigoth lord Theodomirus in 713. These terms ensured religious freedom for the Christians and political independence for his territory but reserving for themselves the tax (a dinar per capita, plus part of the produce from the land). The system of distribution after the conquest awarded a fifth of the land to the state, which is why it later had in these fiscal lands its main source of revenue. In any case the model of a strong fiscal state seems to be inherent to al-Andalus, this being directly connected to the strengthening of central power. Therefore, when this model did not predominate, we can understand it as a deviation from the normal and a testimony that the central state went through moments of weakness, as evidenced by having to cede tax revenue to local or regional authorities.

Precisely the reinforcing of central power under ‘Abd al-Rahman II, in the second quarter of the ninth century, led to a reform of the treasury (Hizanah) and the institution of registers of tax collection (Reference Ibn, Ḥayyān, Makki and CorrienteIbn Ḥayyān, 2001; II-2, 181–182). That facilitated the increase in tax income, which, according to al-Shabinasi’s calculations, approached one million dinars of dirhams (silver), thanks to a great extent to the tax on real estate (haraj), which played an important part in the overall state income. This figure of tax income diminished with the later political crisis, which included agreements (or the lack of them) with the insurgents, giving them autonomy from central taxation. This was the case of the Banu Marwan in the west and the Banu Hafsun in the south of Córdoba.

The reinforcement of the state and the recuperation of the mint under ‘Abd al-Rahman III facilitated that, as Ibn Hawqal states (Reference Ibn, Hawqal, Kramers and WietIbn Hawqal, 1964: I, 111), the tax revenues until 340 AH/951 CE amounted to about 20 million dinars, not counting those on trade in merchandise and luxury goods, a number which is in line with the estimate that the 7.5 million spent on Madina al-Zahra corresponded to a third of the general revenue. In 961, on the death of ‘Abd al-Rahman III, his son al-Hakam II confiscated the courtesan’s fortunes, which enabled him to raise 20 million dinars.

The signs of a growing economy continued during the Amirid period between the last decades of the tenth century and the first decade of the eleventh. Military expenses undoubtedly rose to a new level but, as a consequence, booty also became part of the income. The collapse of the caliphate led to fragmentation into the taifa kingdoms, centred around urban capitals, each ruled by an ethnic elite (Andalusian, Berber or Slavic). They attempted to reproduce the caliphal administrative model, including its taxation. Precisely, the economic growth evident in the eleventh century was not enough to keep pace with the ostentatious courts of the rulers and, especially, pay the parias that the Christian kingdoms to the north demanded in return for peace. This led to high fiscal pressure, which generated popular unrest and disqualification by influential Islamic scholars, who considered this taxation illegal as it was not supported by Islamic law. Thus, at the end of the eleventh century, intellectuals and the general population supported the Berber Almoravid invaders. The crisis of the latter in the mid-twelfth century was followed by a brief second taifa period and the arrival, also from Africa, of the Almohads. At the centre of the policies of both Berber empires was a religious reform expressed also through a different fiscal policy which was less damaging to a rich but already fragile and socially unequal Andalusian society. Based in the Maghreb and with control of the Saharan gold, both the Almoravids and the Almohads could afford this.

A tributary society like al-Andalus may be dependent on taxes but is not necessarily focused on market regulation. A leading study on trade in late Andalusian society (Reference ConstableConstable, 1994: 110) seems to point in the opposite direction, showing how the Christian conquest reinforced control of the markets in which the previous Muslim princes had shown little interest. The lengthy classic study on the market by Reference ChalmetaChalmeta (1973), recently enlarged, analyses the institutional framework considering the evolution of trades (Reference Ibn, Ḥayyān, Makki and CorrienteIbn Ḥayyān, 2001: 393–494) and bearing in mind the data collected, one could ask if there is no contradiction between the idea of losing control and establishing an institutional framework for the markets. Also, the frequency of treatises concerning the urban police (Hisba), like those of al-Saqati or Ibn ‘Abdun in which control of the market and regulation played a major part, seems to contradict that notion. Perhaps the idea, prevalent in the tenth century, that taxation was light referred preferably to market activities but does not mean an absence of regulation. It is true that no general laws were issued, unlike in the thirteenth-century Christian Iberian kingdoms. Hisba treatises are in their stead and would probably be in use for determining market good practices. Also, the ulama played a very important part in regulating the market and economic activities in general as documented in the collection of fatawa by al-Wansharisi. Nevertheless, direct princely intervention cannot be excluded, as demonstrated by the Almohad caliph’s commitment to building markets, as in the case study of Seville, the Suq being part of the aljama mosque complex (Reference Ibn and Ṣāḥib aṣ-ṢalāIbn Ṣāḥib aṣ-Ṣalā, 1969). A concession made to some major ex-Andalusian towns after the conquest by the Portuguese king may shed some light on this issue: by transferring his rights to regulate the market (Almotaçaria) to local authorities he acknowledged that those rights were public and inherited from the Andalusian princely authorities.

1.2.3 Urban Development and Economic Growth

The overall importance of trade in al-Andalus, shown even more through archaeology than the texts, must be put in the context of indisputable urban growth. The rise in trade was closely linked to the state polities, while urban growth was connected to the state-building processes even if in a different way from mint activities. The position of Córdoba as the capital seems to have played a key role in the process, not only because it served as a role model for other cities but also because nowhere else in the west was there a similar concentration of political and economic power that converged with such a large population. The capital of al-Andalus enjoyed an economic influence going beyond the Mediterranean to the south and the Pyrenees to the north, acting as a huge hub of consumption and production that recalls the role played in the Near and Middle East, at different moments, by Constantinople, Baghdad, Samarra or Cairo (al-Qahira).

In the second quarter of the ninth century, under ‘Abd al-Rahman II, Córdoba was not only the seat of power but also the site of considerable industries, among them the Tiraz, the state manufacturer of luxury fabrics. However, the key issue here would be to measure how the network of cities inherited from the late Antiquity benefited from the growth of the capital. Everything seems to indicate the survival of the late Roman cities in Iberia, many of which (Mérida, Toledo, Zaragoza and Seville) retained their position as regional capitals, although other cities were newly created as a result of political choices, like Badajoz and Almería. Precisely, the transfer of the regional capital from Pechina to Almería, which would become a major port city, was a sign of the growing connection of al-Andalus with Mediterranean trade as well as the rise of Murcia, another Levantine city. All this shows the importance of the arrival of irrigated agriculture and intensive production systems associated with small plots of land, but which also allowed very impressive urban growth, particularly in eastern Iberia (Sharq).

The eleventh-century fragmentation of the taifa was based precisely on urban dynamism. These cities had grown notably in the second half of the tenth century, often using material from the earlier Roman city to reinforce the new central points: the main mosque, the souk and the palace complex, Zaragoza being a good example. The physical embodiment of royal power was the zuda or palace, like those in Zaragoza, Lleida (with Balaguer) and Tortosa, or the kasbahs, which had risen to protect the governors from the ninth century onwards. This was the early case of Mérida, and then Seville or the Gharb in Lisbon, creating an urban landscape common to every Andalusian city, much like Aleppo or Damascus in contemporary Syria, where walls began to segregate a military elite from the rest of the population. Zudas and kasbahs housed micro-court societies that emulated the caliphal court cities, with a corresponding economic stimulus.

The walled suburbs that encircled many of the main cities from this period onwards also show that Andalusian cities were not only getting richer but bigger and more populous. This is surely the case of Lisbon, an interesting example if we consider the peripheral position and function of this Atlantic city during the emiral and caliphal periods. Not being a capital of a taifa, nor a key city for the Almoravids, its growth in the century before the Christian conquest of 1147, attested to by the two new neighbourhoods, particularly the western, was not due to any political relevance but to trade, navigation and a rich hinterland. For this reason, Lisbon can be used as a case study for the overall growth of the Andalusian urban system during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a growth resulting both from decentralizing political processes, which stimulated markets at a regional and local level, and the impact of technology on agricultural production, even if considerable differences can be seen in the use of irrigation techniques, particularly between the dry eastern part of al-Andalus and its more humid western regions. In the Sharq, in fact, urban growth during this period seems to have been sustained by intensive agriculture, which accounts for the prevalence of such regional capitals as Valencia and Murcia, and in another sense, is mostly connected to silk production in Granada, a new city that had replaced Elvira in the eleventh century. At the same time, in northern areas near the frontier, like the north of the Ebro Valley, agriculture was based on rural nuclei well protected thanks to public investments, whether central, regional or local.

In the twelfth century, under the Berber empires, the multi-polarized structure of the state, at the central and regional levels, again linked urban development with a central political position. In the first half of the century, Seville and Valencia took on the role of capitals under the Almoravids. Not only these cities but also regional capitals, like Badajoz, Granada or Jaén, grew to a relevance that would be acknowledged after the Christian conquest with the status of kingdoms they were granted. The state capitals, including Marrakesh and the failed attempt in Rabat in Africa, as well as Seville, all underwent extensive programmes of urban renewal involving huge financial and human resources. Some minor centres, like Beja, are also examples of efforts to revive urban structures wherever and whenever widespread warfare had damaged them.

One final issue concerns the impact of this monetized, market-based economy, strongly connected to statal ability to invest, on the Christian northern neighbours. The presence of Andalusian coins can be attested very early and will be enhanced by the payment of parias during the eleventh and again in the mid-twelfth centuries, this time particularly in the extreme west and the east. It is beyond any doubt that this was the model for Christian kings’ coinage activities and also that the contribution made by the input of gold coinage from the south had a major role on the northern principalities’ economic development to an extent difficult to measure. Some other issues, equally important, remain less visible: commercial networks linking northern and southern Iberia, transfers of technology and artisanship, transfer of market institutions and, above all, the development of patterns of consumption in northern societies that some objects we refer to in this chapter seem to attest.

1.3 The Northern Kingdoms and Counties

The northern territories combined continuity with earlier periods and a development that led them to occupy the frontier strip. This expansion led to the consolidation of a feudal society that benefited from urban development and trade links.

1.3.1 The Early Medieval Society

The disinterest of Muslim society in unattractive northern areas of the Iberian Peninsula combined with Frankish pressure, especially in the Eastern sector, disconnected the northern lands from the rest of al-Andalus. In all of them, a strong Roman tradition was maintained, as reflected in the territorial references (villa, strata) or the regional structure. The ease with which the Visigoth kingdom had collapsed does not imply that its interior lived in a state of poverty. The archaeological remains of Visigoth rural centres destroyed in the conquest (Bovalar in Catalonia, Pla de Nadal in Valencia) show active, populated communities, and with currency circulating. Nor is poverty perceived in the journey Eulogius of Córdoba made in the mid-ninth century to the numerous monasteries in the Pyrenees of Navarre. However, it is true that there was a growing regionalization, which meant a progressive ruralization, links between cities and the central state, and the social consolidation of magnates. Accordingly, the latter, mixed with the regional aristocracy, played a role as representatives before the new lords after the central Visigoth state collapsed.

Continuity is perceived in the cities that maintained a leading role, with the local magnates continuing to exercise a guiding hand, as in Pamplona. Also, the most exposed rural areas like the landscape of hilltop sites in Castile highlights the evolution from earlier centuries, which is why the pottery found reflects local structures and poor external connections. Even the Frankish penetration into the north-east of the peninsula accentuated the existing relation with the northern side of the Pyrenees through the former Septimania.

This scenario shows agrarian communities with communal assets and free peasant owners, as seen in Galicia. They were busy buying and selling land on a non-monetary market as well as establishing networks of friendship and patronage, which facilitated the rise of a local elite around the tenth century. Consequently, inequality between farmers grew. In the Pyrenees of Navarre and Aragon, the difficult geography, coupled with an ever-present Muslim danger that increased in the tenth century, invigorated the weight of the aristocracy and led to an early rise in peasant servitude. In the east, the documentation from the Catalan counties shows some allodiums belonging to lords but worked by enslaved people or fiscal servants; some lands were ceded to free peasants under various agreements and others under contract (precaria) established according to agreements. However, in both the east and the west, the magnates stood out (many of whom were initially neither nobles or clergy) and accumulated a large number of properties. On this base, they founded monasteries and churches and became close to the Asturian and Navarrese monarchies, which from the mid-eighth century tried to assert their pre-eminence.

Hunting for small game was important in peasant production at that time. Agriculture based on growing cereals was spreading. Wheat was very unusual, even on aristocratic tables. Instead, the barley was the staple, followed by rye, which was better adapted to poor soils. Other cereals were also grown, including millet, spelt or other variants of millet such as pámula and panizo. Vineyards were also expanding, in smaller plots and with a low output. Other plants, such flax and hemp, were always needed for textile production. Irrigation was valued, which is why it was specified in contracts – subtus rego – and the insulae in the rivers were negotiated. The canals for mills were used for irrigation and specific small channels were used in tenth century in the Barcelona region and Roussillon, for instance. The use of manure as a fertilizer is documented in the same century, but the effects of a shortage of tools and draft animals and variability in the weather contributed to irregular crops, with some really bad years, as explicitly documented in the eastern counties in 990.

Nevertheless, the general tendency was for growth. Everywhere there was an important and continued increase in agricultural land in the eighth and ninth centuries, through the presura or aprisio. This principle, according to Visigoth legislation, granted a right to ownership after 30 years working land that had no known owner. The increase in farmed areas had previously happened in northern regions, such as Septimania, and reflected growing population density and the necessary growth in agricultural production. From this, some historiography has emphasized the increase in full ownership by family units, giving an image of a society full of free peasants who were small landowners. In any case, the documentation leaves no doubt that the dynamics of economic expansion benefited, above all, the magnates, including the groups close to power (as is the case of viscount and vicar lineages in the Catalan counties) and the ecclesiastic hierarchy formed by monasteries and bishops. Between the eighth and tenth centuries, all of these accumulated great landed estates as the basis of their power.

Livestock was also becoming increasingly significant. The contents of wills reflect the importance given to the ownership of small numbers of animals. In any case, magnates and monasteries were soon accumulating larger herds, as documented in negotiations for pastures by monasteries such as those in Arles in 878, Sant Joan de les Abadesses in 977 and Sant Pere de Besalú in 978. In the tenth century, livestock farming was regulated by properly organizing the areas of grass and pastures, although conflicts could not be avoided, like the one in the delta of the River Llobregat. Mountain territories such as Aragon received an economic boost from livestock. At that time, transhumance routes worked more on a basis of altitude than distance. This livestock was mainly sheep and goats, in addition to pigs, but with smaller numbers of oxen and horses given their high price.

The increase in production encouraged the work of blacksmiths and the spread of metal instruments. By 860, there was already a documented demand in Andorra for ‘decimis Andorrensis pagi ferri et piscis quae aeclesie sue debentur’ (Reference AbadalAbadal, 1952: 287). In the ninth and tenth centuries, the demand for arms and tools given the expansion of agriculture stimulated metal production in the Pyrenees (using water power often under the control of monasteries), but also in the new lands, where smithies were set up, especially working on repairing implements. The increase in mills had a greater economic and social impact. Molinarem anticuum was stated in Lillet, in the Pyrenean zone, in 833. The construction of a mill was complex, requiring a dam, a canal and a reservoir, in addition to the mill itself. However, in the ninth and tenth centuries, these spread along the rivers following the expansion of agriculture. This reflected the growing demand for flour, which was part of a change in eating habits. Secondary cereals are more digestible cooked than baked, which explains that in the Early Middle Ages the most important food was a stew based on cereal served as semolina or porridge combined with portions of meat and other products, often according to what was foraged in the forests. Focusing agriculture on cereals and dedicating the majority to flour processing implied the spread of bread and, with it, the progressive implementation of a new dietary model, based on the three items that would dominate the late medieval table: bread, wine and meat.

Consistent with this dynamic, at that time, the tax burdens fell mainly on agricultural production, in contrast with what was seen at the beginning of the eighth century in the eastern counties with their taxes on livestock and, above all, on trade. In fact, commercial activity had remained at a high level in the north-east of the Peninsula. This is perceived in the continuity of the markets in the cities and, notably, by the desires to possess the teloneum, a toll on the movement of merchandise to the market. In the ninth century, the ecclesiastic authorities asked the Carolingian sovereigns for control of this tax, a request that was granted partially. In 834, Lothair of Aquitaine gave the bishop of Elne ‘mediam parte mercati’, and in the same year, Louis the Pious conceded ‘tertia parte de pascuario et teloneo’ to the bishop of Girona in the ‘pagus’ of Girona and Besalú. Similarly, in 889, Eudes granted the bishop of Osona ‘theloneis mercatorum terre’. The internal movement and the relationship with long-distance trade were combined. In 860, the bishop of Urgell obtained the right to part of the teloneum on goods crossing his large dioceses in the Pyrenees and the bishops of Girona in 844 and Barcelona in 878 obtained a similar concession on merchandise arriving by land or sea.

However, there were other mountainous areas that seem to have had low levels of trade, such as Aragon. Similarly, the inward-looking nature and scarce outward orientation that characterized the Cantabrian area was a continuity of the disconnection in the fifth century following the fall of the Roman Empire as the region was closely linked to the economic and political needs of the Imperial power structures. The former Roman structures were also maintained in the western areas (Asturias and Galicia). They had little connection with the outside world and, instead, there was a continuity of regional markets and a network of urban capitals in rural regions.

The increase in space and agricultural production was consistent with a significant growth in trade, which combined the distribution of regional produce and other transported from afar, especially in the second half of the tenth century. The spread of hostels for pilgrims and travellers at the same time makes sense. At the end of the century, markets are documented in large cities and middle-sized towns, especially those with good communications. This is clear in many places in the eastern counties (Elna, Girona, Barcelona, Vic, Cardona, Urgell, Anglès, Gerri, Bages, Llor and Llavorsí). Also in the west, markets in Sahagún and León were complimented with those in Zamora or Cea. Some markets, like the one in Villafuentes (Burgos), clearly redistributed local produce. In other cases, they enabled a connection with products brought from afar. Luxury goods were usually from al-Andalus. These included silk, cotton, brocades, skins and leather goods, as well as perfumes and precious objects. Exports to the south were very specific, such as weapons made of Pyrenean metal or coral from Empúries, already documented in the ninth century. In fact, testimonies from the eighth and ninth centuries, such as the request from the bishop Elipandus of Toledo to Felix of Urgell who sent him a letter cum mercaturios, or the French clergy who journeyed seeking relics, show a network of communications travelled by merchants. The central role in this connection with Europe was played by Barcelona (‘via Mercaderia’ was the name given in the tenth century to the route continued to the Pyrenees via Girona) and secondarily through Pamplona, both cities connected to Muslim Zaragoza, where the routes linked to the heart of al-Andalus via Toledo.

Nevertheless, commercial investment was scarce, because credit responded more to consumption than investment, if we look at its short terms – the return dates coinciding with the harvest of cereal or wine and high interest rates, which in some cases reached 50%, despite the formal legal limitation included in the Visigoth legislation. The currency was, primarily, the benchmark for calculating sales, contracts and credits ‘ad rem valentem’. Reiterated references like the ‘solido’ of Galicia in the tenth century were not to a real currency but rather to units of account. Only in the north-east of the Peninsula, under Carolingian domain, were coins minted in the ninth century in Barcelona, Girona, Empúries and Roda de Ter (identification disputed with Roses). The bishops intended to monopolize the inherent profits. In 862, the emperor yielded a third of the profits from the currency of Barcelona to the bishop. This was also applied in Osona county in favour of the bishop of Vic with a disputed interpretation of Wilfred II’s will when he died in 911, and then in 934, when Count Sunyer granted it to the Bishop of Girona. The lack of precious metals and even the legitimist ideology of the Asturian monarchy impeded the issuance of coinage in the west. However, during the second half of the tenth century, Muslim currency circulated all through the north, although geographically unequally distributed.

1.3.2 The Frontier and Its Occupation

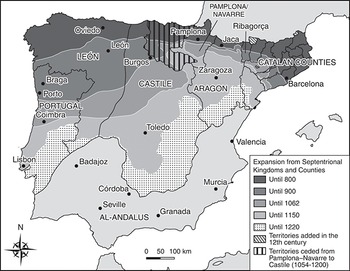

The frontier was stabilized in the mid-eighth century as a wide strip of territory between the Christian North and the Islamic South (see Figure 1.1). It covered the entire Douro Valley, a small strip north of the Ebro Valley and the lands east of the Muslim cities of Lleida and Tortosa. The historiography had imagined an empty territory that was occupied by the legitimate population who would recover their lands after retreating to the mountains; or a space open to spontaneous settlers who would find land and freedom until the nobles seized it through the feudal revolution in the following century. In reality, it was not barren, unoccupied territory but a disorganized one, that is to say atomized into various local communities and scattered settlements.

Figure 1.1 The Iberian Peninsula in the eighth–twelfth centuries.

Since the late Roman crisis, the population in the Douro Valley had been concentrated in ‘castra’, usually on local roads dominating a space with other minor occupations – ‘penellas’, ‘populaturas’ – and always in scattered, inward-looking, settlements. This included the continuity of populations like Castelhos Velhos or ‘civitas’ like Zamora. These peasant communities produced small local elites who acted as intermediaries with the outside, although contacts were scarce. Coherently, pottery remains are common local products and some imitations of sigillata, combining domestic pottery done on a slow wheel with other larger pieces done by hand. The scenario encouraged the lords of the north to lead incursions against notable populations that survived independently, as was the case of the ‘civitates’ in the Douro Valley attacked by the Asturians.

On the north-eastern side of the Peninsula, the frontier strip was narrower. This accentuated its function linking two peoples through raids between them (Muslims against Christian settlements and vice-versa in nightly expeditions), as Ibn Ḥayyān explained as happening in 975 (Reference BramonBramon, 2000: 326) and all kind of human relations. Many documents describe the no-man’s land of this frontier as a place full of ruins – ‘villa herema’, ‘ancient parietes’, ‘altos parietos’ – but with sufficient continuity to maintain the place names and inhabited by farmers and gatherers who lived between the two sides of the frontier. They appeared as an amalgam made up of remnants of the original population, early Islamic settlers, some fugitives and spontaneous settlers, all in a suspicious position, who coexisted with each other. From the Christian side, they were seen as ‘gentem paganam, perversos cristianos […] male insidiantes’ (Reference JunyentJunyent, 1992: 132).

The cohesion of these frontier territories could only come from outside. The growing economic power of the northern territories in the ninth century had boosted their elites, who projected their vigour onto the frontier strip. Therefore, the sovereign of the Asturian kingdom intended to repopulate attractive places on the frontier, such as Zamora in 893, and led armed interventions, such as the repopulation of various cities after the battle of Simancas in 940. From the last decade of the ninth century, Alfonso III of Asturias led a successful conquest to the south and east, thanks to attracting the local elites and their respective (often independent) efforts to conquer domains and occupy regions, who, in exchange, increased their status sheltering under royal protection. In fact, by serving the king they obtained donations in land, or his approval of pressures already applied. This was started by the counts of Castile in the tenth century. They ended up controlling the eastern side of the kingdom through their own conquests. In this way, numerous nobles expanded the frontier of the Asturian kingdom from Viseu, Santiago or Astorga in the west to Amaia or Osma in the east.

In the tenth century, the frontier everywhere benefited the aristocracy and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, formed by bishops and monasteries. Throughout this century, viscount and vicar lineages and ecclesiastical hierarchies from the former Carolingian counties led a systematic occupation of the eastern strip. They seized coherent areas within the frontier, marked them and built castles to rule this space. This transformed the border into a dense network of castle districts. In Aragon and Pamplona, north of the Ebro, the occupation of the border fringe was similar, under more direct control from the sovereign, who granted the territory as ‘honores’ for his barons. Similarly, in the centre of the peninsula, the ‘alfoz’ defined the new districts.

The real aim of occupying the frontier fringe was to establish perennial systems of territorial organization, trying to link the population permanently to their lords and the agricultural production to seigniorial and jurisdictional levies. The landscape was therefore covered with aristocrats’ castles controlling well-defined districts. The profits from this occupation could only be obtained from due agricultural development of the land. Therefore, the lords systematically called for new population – ‘agricultores ibi obducas ad habitandum et ad excolendum opus rusticum in eo’ – the scope being defined as ‘ipsa terra erema perducas ad cultura’ (Reference Font RiusFont Rius, 1969: 24, 25–26). The tax burden was initially weak to encourage occupation, while the population already residing on the frontier was initially respected in its allodial right despite becoming subject to the new jurisdiction. This direct relationship between the owner and the person with the right to work it soon became complicated by the progressive accumulation of rights over the property, with intermediate owners, often monasteries, appearing which lengthened the chain of those who held rights over the property.

Thus, the occupation of the frontier in the tenth century continued the social and agrarian densification seen in the interior in the previous century. Agriculture based on cereal and vineyards was consolidated, contracts for the development of vineyards were disseminated, like the complantatio in the eastern counties and the rivers was used for the construction of mills. Some spaces taken from the border were suitable for livestock, such as the mountains of Salamanca and Ávila. The changes in ownership and landscape were justified by the Christian doctrine that supported the expulsion of the invading Muslim who had occupied these lands and also the Christian duty to transform the ‘eremum’ into ‘cultum’. The development of these territories strengthened towns and cities as central places for services and exchange, which consolidated the power of their elites and at the same time blurred the disquisition between the urban and rural spaces. The old frontier as a fringe of separation disappeared, absorbed and converted into a well-articulated space, one which was fully integrated into the northern domains. From this moment on, the frontier would become a line, which led to warlike relations in the eleventh-century feudal context.

The expansion of the eleventh century penetrated into Islamic territories in the east, where the infrastructure was used either to displace the population, change crops and impose a new feudal structure under the formula of castles districts, if necessary divided into minor sub-districts called quadres. In the centre of the Peninsula, south of the Douro, especially in the second half of the century, the new territories combined military defence, repopulation and rural and agrarian colonization under royal jurisdiction. They were organized into extensive ‘alfoces’, a kind of territorial and administrative unit that brought together numerous villages dependent on the respective town council. At the end of the eleventh century and throughout the twelfth important towns and cities grew up presiding over extensive alfoces. These included Sepúlveda, Segovia, Ávila, Plasencia or Toledo in Castile and Calatayud, Daroca, Teruel and Albarracín in Aragon.

The circulation of people and goods and the complexity of the occupation of the territory transformed the social and economic reality both in the new lands and in the interior. The prosperity of the interior lands cannot be understood without the wealth coming from the border. It was not only about the loot or commercial relationship with al-Andalus but, notably, the establishment of a permanent system to extract income, one which greatly benefited the aristocracy and ecclesiastical hierarchy. All the urban capitals and indoor market centres benefited from this system. The emergence of Barcelona, as a clear example, was related to its opening to the Mediterranean as well as its hinterland, which included prosperous cities (three episcopal seats: Barcelona, Vic and Girona), but directly because of the profits that enriched aristocrats and clergy from the nearby border settled in the surroundings of Barcelona. On its part, the institutionalization of royal powers in León, Castile and Navarre was mainly based on the frontier, which produced immediate profits, a place where durable social and economic links were established and the framework to take the various holders of power into the royal orbit.

1.3.3 Societies in Expansion

The Asturian monarchy was gaining ground thanks to ensuring its links with aristocrats and magnates, and in 910, it moved its seat southwards, from Oviedo to León. This city was consolidated as the urbs regia, as Fernando I reinforced it, initially settled on the eastern frontier of the kingdom, as count of Castile, and who in 1037 assumed, now as king, the thrones of León and Castile. He based his rise on the promotion of different clienteles in his curia and in administrative roles outside the court, together with successful conquests and new ways of promoting the settlement of the newly added areas. Royal wealth enabled him to undertake notable projects, like the collegiate church in León in 1063. In 1085, when Alfonso VI of Castile conquered Toledo, one of the Muslim capitals and ideological reference for the Visigoth monarchy, the territorial expansion offered him the way to solidify his power through presiding over a structure of magnates converted into his vassals.

The movement on the frontier and the wealth of all the northern kingdoms and counties was shaped in the eleventh century by the supply of financial contributions the taifa kingdoms in the Muslim south were obliged to hand over, the tributes called parias. Previously, trade, booties and ransoms made the Andalusian currency familiar, like the profit Alfonso III of Asturias earned in 878 for returning to Muhammad I one of his leading ‘consiliarius’. Muslim gold coins were circulating more regularly in the northern lands at the end of the tenth century. The eleventh-century parias benefited all the northern kingdoms and counties, as well as leading warlords like El Cid or Arnau Mir de Tost. Incomes from these were very high between 1048 and 1073 but diminished from then on. They injected a great deal of cash, especially gold, into the northern territories, favouring an increase in wealth that had immediate political, social and economic effects. It is thus no surprise that, in the 1080s, the county of Barcelona focused its efforts on applying pressure to the taifa kingdoms in the east of the Peninsula to ensure this important source of income. The parias disappeared with the arrival of the Almoravids and did not reappear until this empire entered into crisis between 1130 and 1170. It was precisely then, from this context, that Ibn Mardanīš, the Wolf King, aimed to build an Andalusian kingdom around Murcia in the south-east of the Peninsula, but found himself obliged to pay important parias, agreed in a pact between Alfonso the Chaste of Aragon and Alfonso VIII of Castile.

The issuance of currency had only been maintained in Barcelona but during the tenth century and the beginning of the eleventh, the counties of Besalú, Cerdanya-Berga, Empúries, Roussillon, Urgell joined it, as probably did Ribagorça, as well as Girona, which belonged to the same count of Barcelona. The bishops of Girona, Urgell and, especially, Vic also issued money, as did the Viscount of Cardona, who occasionally put it into circulation at the end of the eleventh century in Calaf. While population growth and economic development stimulated the circulation of cash, the link between the issuance of currency and royal power explains why Alfonso VI issued money for the first time in Castile shortly after the conquest of Toledo (1085) and that Sancho of Aragon did the same soon after taking Pamplona (1076), a move that turned him into the sovereign of both kingdoms. Soon after, around 1085 Aragonese currency was minted in Jaca. At the same time, the circulation of Andalusian currency was made compatible with the arrival of European money. From the end of the eleventh century and even more in the twelfth, a lot circulated from the Camino de Santiago, especially Angevin, Tours and Melgueil shillings (solidos), while the latter also spread across the north and Catalonia. In the twelfth century, various cities in León and Castile issued currency. These included León, Toledo, Santiago, Salamanca, Ávila, Palencia, and probably Oviedo, Osma, Nájera and Burgos, the profits from these issues coinciding with certain cathedrals and monasteries. At the end of the twelfth century, in the east, the main reference currencies were defined, such as the Jaca and Barcelona shillings (solidos) and other local coinage was strengthened like that of Agramunt in Urgell, while the importance of the Melgueil shilling in the Catalan north-east reflected the cultural and economic proximity between Catalonia and Provence, and in Navarre at the end of the twelfth century there were the sanchetes in reference to Sancho VII.

Around 1018 gold coinage began to be issued in Barcelona, and this would continue regularly throughout the century. These were the mancusos that imitated Andalusian currency. The initiative for these issued was private, linked to the financial strategies in a context of a great deal of wealth circulating. The count of Barcelona worked to control the currency issues, and did so between 1069 and 1076. Precisely, in 1069 gold mancusos were coined with his name (‘RAIMUNDUS COMES’). Gold coins may occasionally have been minted in Besalú between 988 and 1020, coinciding with a moment of splendour for this county, similarly to what happened in the final years of the century with the city of Jaca in Aragon. In another context, Almoravid gold coins were occasionally imitated by Alfonso VII of Castile around 1150, these being issued in Baeza in the brief period he held the city. However, it was from 1176 under Alfonso VIII when imitation Andalusian morabatinos were issued. These were prestigious coins that circulated throughout the Peninsula, including both Navarre and the Catalan counties. The emission of gold morabatinos or maravedíes also happened in León, under Ferdinand II from 1177. Precisely the Leonese king ceded the rights to the currency to the Church; in 1186 to Salamanca Cathedral and in 1193–1194 to the Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. In Portugal gold coins were minted under Sancho I, in 1185–1189.

Trade allowed the surpluses from one area to be redistributed and, at the same time, luxury articles to be exchanged. These included luxurious fabrics and objects made of precious metals or ivory from al-Andalus, not infrequently from the Orient, that were used by the aristocracy and in the Christian liturgy. On occasions these objects were very unusual, like the three chess sets made of 96 pieces of rock crystal, produced between the end of the tenth and beginning of the eleventh century, which reached Arnau Mir de Tost, lord of Àger. In other cases, they produced a multiplier effect and were replicated, which is why in the eleventh century in Valdesaz, near León, artisan tiraceros imitated silk cloth.

Initially, the Jews tended to stand out in long-distance trade. It was Jews who, shortly before the mid-eleventh century, transported products for leading magnates in the west of the Peninsula, especially Menendo González, but were assaulted by rival aristocrats, losing 1,700 pounds of silk, 30 tunics and 30 linen canvases. A large part of credit was also entrusted to the Jews, like near Coimbra in 1018 when an enslaved man sought them to obtain the money with which to buy his freedom. However, the increase in wealth in the mid-tenth century generalized the participation in long-distance trade, as denoted by the traders in Barcelona from various places or the permission granted by Borrell II to subjects from Sant Cugat to fish and carry mercaderias by boat, a privilege confirmed by the count’s son, Ramon Borrell of Barcelona, in 1011. Very significantly, the Peace and Truce conceded by Bishop Oliba of Vic in 1030 protected all participants in the markets: ‘quicumque mercatores ad mercata venientes aut in mercata manentes aut inde redeuntes’ (Reference Gonzalvo BouGonzalvo, 1994: 7).

The increase in trade meant the development of artisanal activities, which appeared in the urban fabric, like the ‘tendas’ documented in the tenth century in both Barcelona and León. The high immigration of ‘francos’ from Europe, from the end of the eleventh century was mainly of those dedicated to urban trades centred around commerce, artisanal activity or construction. Unquestionably, between the end of the eleventh century and early decades of the twelfth, all the towns and cities on the line marked by the Camino de Santiago, across the kingdoms of Pamplona and Aragon and Castile and León, received a large number of immigrants. This led to the growth of specific neighbourhoods for these ‘francos’, with a customized legal status, especially in Navarre. This way, the inventio of Santiago de Compostela not only generated a nucleus of great consequences at the ecclesiastic, political and social levels, but that the way that led Christendom to this centre worked as a route for pilgrimage and trade, generating great wealth, with a multiplier effect that benefited all sectors of society, which explains the royal backing, with explicit actions like the establishment of hospitals under Alfonso VI. It coincided with a political opening to France, which facilitated the entry of the Gregorian reform, the influence of Cluny and elites of French origin around Alfonso VI. Meanwhile, the Pyrenean territories, Pamplona, Aragon and the Catalan counties with Barcelona to the fore, were interrelated with Occitania and Provence, establishing a political, economic and cultural link highlighted in the twelfth century.

The urban development consolidated a specific bourgeois social group, denomination that appeared in the fuero of Jaca in 1077, differentiating between burguensis, miles and rusticos. The urban setting was clearly stratified with elites like those found in the twelfth century in Pamplona, Burgos, León, Sahagún, Santiago de Compostela, Barcelona or Lleida. The documentation conserved referring to the latter two shows an urban elite dedicated foremost to investment in properties, and all kinds of rights, rents and activities, thus reinforcing a leading position from which they assumed the representation of the city before the respective lord. The numerous weekly markets established all over the territories from the eleventh century reinforced the vitality of the urban nuclei as regional centres. The central role of these towns and cities and the attraction of long-distance trade was strengthened with the annual fairs, beginning with the one in Belorado in 1116, to which others, like Valladolid, Sahagún and Jaca, were added during the same century. In this context, at the end of the twelfth century, the axis established by the Camino de Santiago lost its uniqueness due to the drastic reduction in immigrants in the last third of the century and, especially, because the urban fabric showed the entrenchment of the cities that grew on the old frontier, as well as the emergence of those on the Cantabrian Coast. For its part, from the end of the eleventh century and notably throughout the twelfth, Barcelona had risen as a trading port open to the Mediterranean, which explains its permanently fluctuating relations with Genoa.

1.4 Conclusion

The long evolution that had been transforming the Iberian economy since the fifth century found its excipient in the Islamic invasion at the beginning of the eighth century. The establishment of the frontier and then its transformation were its main consequences. The social and economic transformations that occurred between the eighth and tenth centuries were at the base of the social model that would be developed in the Christian world during the rest of the Middle Ages, including the forms of seigneuralization and extraction of rents and income. The overwhelming transformation of the landscape guaranteed the agrarian base of the economy, with the predominance of cereal and vineyards, at the same time that a network of urban capitals with their markets was reinforced to articulate internal distribution and external relations. From this moment on, the border would be, first and foremost, a line that separated two cultures, which remained related by cultural and economic exchanges. This path did not lead to inward looking but rather to an opening to the exterior, well illustrated by the economic momentum around the Camino de Santiago, the establishment of an inextricable political, social and economic connection between both sides of the Pyrenees and, at the same time, the opening of trade to the Mediterranean.