Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common mental disorder with an estimated prevalence of 15.4% in the most robust epidemiological studies (those using diagnostic interviews and random samples) of conflict-affected populations, Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren1 and a 12-month prevalence across the world of 3–4%. Reference Karam, Andrews, Bromet, Petukhova, Ruscio and Salamoun2 The disorder may occur in people of any age who have been exposed to one or more exceptionally threatening or horrifying events. Characteristic symptoms include re-experiencing, avoidance and hyperarousal. 3,4 The disorder is associated with substantial comorbidity, such as depression, anxiety and substance misuse, Reference Brunello, Davidson, Deahl, Kessler, Mendlewicz and Racagni5 and significant economic burden. Reference Ferry, Bolton, Bunting, O'Neill, Murphy and Devine6 Previous meta-analyses of pharmacological treatment of PTSD have been inconsistent. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines found that only paroxetine, mirtazapine, amitriptyline and phenelzine were significantly superior to placebo. 7 Owing to the relatively small effect sizes and sample sizes, none of these drugs was included as a first-line treatment for PTSD; all were recommended as second-line treatment after the initiation of trauma-focused psychological treatment. The guidelines of the Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health (ACPMH), consistent with NICE, recommended that pharmacological interventions should not be used in preference to trauma-focused psychological treatment. 8 Other reviews have been more positive about pharmacological treatment, grouping selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) together and rating them as equivalent to trauma-focused psychological treatments. 9,Reference Foa, Keane, Friedman and Cohen10 A Cochrane review reported strong benefits, Reference Stein, Zungu-Dirwayi, Van der Linden and Seedat11 but the Institute of Medicine found inadequate evidence to determine the efficacy of pharmacological treatment for PTSD. 12 There are, however, major differences between the methodological quality of these reviews, making direct comparison problematic. Reference Forbes, Creamer, Bisson, Cohen, Crow and Foa13 Given the inconsistent findings of previous meta-analyses and the increasing number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacological treatments, the World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned an update of the information obtained by the most methodologically robust systematic reviews published to date: those by NICE, ACPMH and the Cochrane Collaboration. 7,8,Reference Stein, Zungu-Dirwayi, Van der Linden and Seedat11 We reviewed RCTs that assessed the efficacy of pharmacological treatment compared with placebo control groups at reducing traumatic stress symptoms in individuals experiencing PTSD.

Method

All double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and comparative trials of the pharmacological treatment of PTSD completed from October 2005 (to ensure all eligible trials not published at the time of the NICE, Cochrane and ACPMH searches would be included) were considered in our primary and additional searches, covering 13 separate databases. Trials completed before October 2005 that were included in the NICE, Cochrane and ACPMH reviews were also considered. Published and unpublished abstracts and reports were sought out in any language. Studies were not excluded on the basis of differences between them such as sample size and duration. Pharmacotherapy trials in which there was ongoing or newly initiated trauma-focused psychotherapy or where the experimental medication served as an augmentation agent to ongoing pharmacotherapy were excluded. Pharmacotherapy trials in which there was ongoing supportive counselling were allowed provided it was not initiated during the course of the treatment, on the basis that this is common in trials and the limited evidence for supportive counselling. Reference Bisson, Ehlers, Matthews, Pilling, Richards and Turner14 Open label trials were not considered. Our review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist and reporting guidance. 15

Participants

All studies of participants with PTSD according to ICD or DSM criteria were eligible. 3,4 There was no restriction on the basis of onset, duration or severity of PTSD symptoms, or on the presence of comorbid disorders, trauma type, age or gender of participants.

Interventions

Pharmacological treatments for adults with PTSD, in which the comparator was a placebo or other medication, were eligible for inclusion.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest were clinician-administered continuous measures of symptom severity such as the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale. Self-rated PTSD symptom scales were considered separately. The total number of participants who left the trial early for any reason was used as a proxy measure of treatment acceptability.

Search strategy

We conducted a primary bibliographic database search of Medline, Medline In Process, EMBASE, the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database, PsycINFO, ASSIA and CINAHL using the Ovid interface on 22 February 2013. In order to avoid language bias, we separately searched (using the same search strategy, and in consultation with regional experts) the Japanese, Chinese and WHO regional databases (Spanish, Russian and Portuguese languages). This initial broad search was intended to identify not only the RCTs of interest but also reviews of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. The comprehensive search term used (see online Appendix DS1) was created by amalgamating the previous search strategies from the NICE, Cochrane and ACPMH guideline reviews with an updated list of medications. Additional searches for published and unpublished studies were made in the National Center for PTSD PILOTS database, the Cochrane Library, the Controlled Trials Register, Web of Knowledge, OpenSIGLE and Google Scholar. Reference lists of all selected studies and reviews were further scrutinised for any additional RCTs. An expert group was consulted to identify any additional studies they were aware of. Authors of identified studies were contacted to request data if outcome information was missing.

Study selection

One reviewer transferred the initial search hits and studies included in the earlier systematic reviews into EndNoteX4 software for Windows. Duplicates were removed. Two reviewers then independently screened the titles and abstracts. Studies that were clearly irrelevant were excluded; potentially relevant ones were assessed for inclusion as full texts. Any discrepancies between reviewers’ decisions were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

All data from newly identified studies were double-extracted by two independent reviewers into a standardised table and any discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer. Data for change from baseline to end-point were extracted when available, otherwise end-point data were used. Continuous data were extracted for clinician-administered PTSD symptom severity using the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale as the gold standard; for self-rated PTSD, the Davidson Trauma Scale was used as the gold standard. If these scales were not used, data from alternative scales were extracted. Dichotomous data were extracted for number of people withdrawing from the trial using total number of participants in the group as the denominator. One reviewer entered the outcome data into Review Manager 5 software for Windows, which was then checked by another reviewer. Data from studies included in previous systematic reviews were double-extracted by two independent reviewers, cross-checked for accuracy and any discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer.

Risk of bias

Two reviewers, using the domain-based evaluation method recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, Reference Higgins and Green16 independently assessed risk of bias in individual studies for each trial. This method considers the following domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking of participants and personnel; masking of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other sources of bias. Any discrepancies between reviewers’ decisions were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. Risk of bias across studies was assessed by considering publication bias through the visual examination of funnel plots.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5 software was used to synthesise data using meta-analysis and to provide forest plots for dichotomous and continuous data. Confidence intervals of 95% were used for all analyses. Categorical outcome measures such as leaving the study early were analysed using relative risk (RR) calculations. For continuous data, standardised mean differences (SMD) were used. The degree of heterogeneity between studies was calculated using the I2 statistic. Where this was less than 30%, indicating a mild degree of heterogeneity, a fixed effects model was used; a random effects model was used when I2 was greater than 30%. Data were analysed from the intention to treat (ITT) sample in the ‘once randomised always analysed’ fashion where possible, to avoid effects of bias from completers-only analyses. Analyses were performed for individual drugs and, in order to maximise the information available from data synthesis, whenever possible for classes of drugs (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs) and trauma type (e.g. combat trauma, sexual trauma, interpersonal violence trauma, all non-combat trauma).

Results

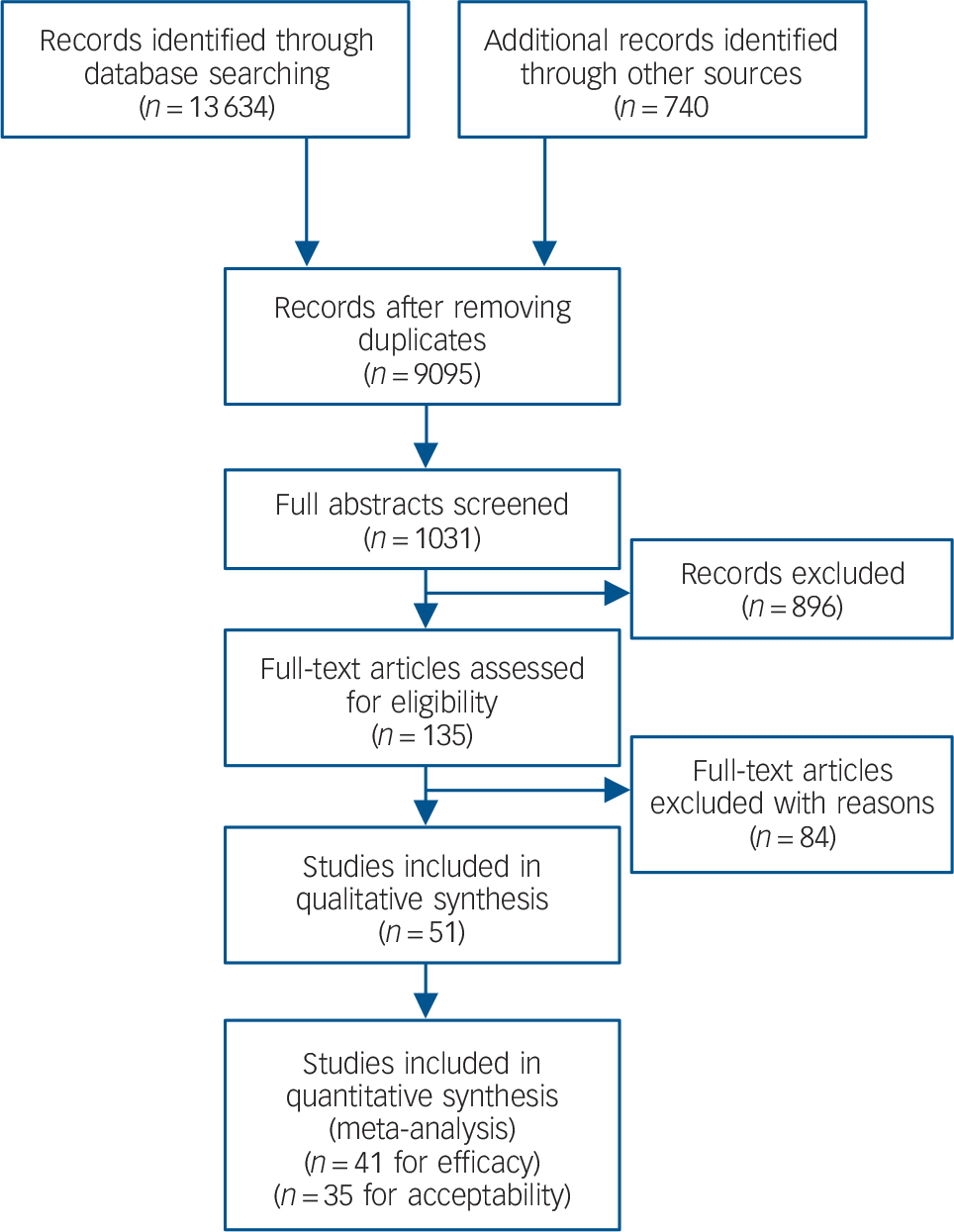

The database search yielded 13 634 records and an additional 74 were identified from other sources. From these, 4613 duplicates were removed leaving 9095 records. These were screened and 8064 irrelevant studies were removed. This left 1031 abstracts from which 896 were removed as ineligible. This left 135 full-text articles which were reviewed to find 84 not meeting the inclusion criteria. A total of 51 studies were included in this systematic review (Fig. 1). Sixteen new studies were found from our database search. Reference Connor, Davidson, Weisler, Zhang and Abraham17–Reference Petrakis, Ralevski, Desai, Trevisan, Gueorguieva and Rounsaville32 The remaining 35 were found in previous reviews. An additional 28 studies were identified from the NICE guidelines, of which five did not meet our inclusion criteria. Reference Cohen, Kaplan, Kotler, Kouperman, Moisa and Grisaru33–Reference Stein, Kline and Matloff37 This left 23 studies included from the NICE guidelines (references Reference Brady, Pearlstein, Asnis, Baker, Rothbaum and Sikes38–Reference Zohar, Amital, Miodownik, Kotler, Bleich and Lane54 plus six unpublished studies A-F in Appendix 1). Thirty-five studies were identified in the Cochrane review, of which 19 were already included in the NICE review and removed as duplicates. A further four used completer-only data and were not included; Reference Kaplan, Amir, Swartz and Levine55–Reference Smajkic, Weine, Djuric-Bijedic, Boskailo, Lewis and Pavkovic58 another allowed concomitant psychotropic medications and was excluded. Reference Reich, Winternitz, Hennen, Watts and Stanculescu59 This left an additional 11 studies from the Cochrane review, Reference Baker, Diamond, Gillette, Hamner, Katzelnick and Keller60–Reference Van der Kolk, Spinazzola, Blaustein, Hopper, Hopper and Korn70 which were included. There were 12 additional pharmacotherapy studies identified from the ACPMH guidelines, of which seven were already present in the above reviews and were removed as duplicates. A further four did not meet our inclusion criteria, Reference Mooney, Oakley, Ferriter and Travers71–Reference Stein, Kline and Matloff74 leaving one additional study which was included. Reference Davidson, Connor, Hertzberg, Weisler, Wilson and Payne75

Fig. 1 Study search profile.

Description of studies

The characteristics of the 51 RCTs included in this review are summarised in online Table DS1. Only three of the studies did not employ a placebo comparator arm. Reference Spivak, Strous, Shaked, Shabash, Kotler and Weizman28,Reference McRae, Brady, Mellman, Sonn, Killeen and Timmerman65,Reference Saygin, Sungur, Sabol and Cetinkaya67 There were 31 SSRI trials, 14 of which assessed sertraline, Reference Friedman, Marmar, Baker, Sikes and Farfel21,Reference Panahi, Moghaddam, Sahebkar, Sahebkar, Nazari and Beiraghdar26,Reference Brady, Pearlstein, Asnis, Baker, Rothbaum and Sikes38,Reference Davidson, Pearlstein, Londborg, Brady, Rothbaum and Bell42,Reference Davidson, Rothbaum, van der Kolk, Sikes and Farfel43,Reference Davidson45,Reference Zohar, Amital, Miodownik, Kotler, Bleich and Lane54,Reference Brady, Sonne, Anton, Randall, Back and Simpson61,Reference McRae, Brady, Mellman, Sonn, Killeen and Timmerman65,Reference Saygin, Sungur, Sabol and Cetinkaya67,Reference Tucker, Potter-Kimball, Wyatt, Parker, Burgin and Jones68,A,C,D nine assessed fluoxetine, Reference Martenyi, Brown and Caldwell23,Reference Connor, Sutherland, Tupler, Malik and Davidson40,Reference Hertzberg, Feldman, Beckham, Kudler and Davidson47,Reference Martenyi, Brown, Zhang, Koke and Prakash51,Reference Martenyi, Brown, Zhang, Prakash and Koke52,Reference Van der Kolk, Dreyfuss, Michaels, Shera, Berkowitz and Fisler69,Reference Van der Kolk, Spinazzola, Blaustein, Hopper, Hopper and Korn70,Reference Davidson, Connor, Hertzberg, Weisler, Wilson and Payne75,B seven assessed paroxetine, Reference Wang, Tan, Wang, Wang, Cheng and Chen22,Reference Petrakis, Ralevski, Desai, Trevisan, Gueorguieva and Rounsaville32,Reference Marshall, Beebe, Oldham and Zaninelli50,Reference Tucker, Zaninelli, Yehuda, Ruggiero, Dillingham and Pitts53,Reference Marshall, Lewis-Fernandez, Blanco, Simpson, Lin and Vermes64,E,F one citalopram, Reference Tucker, Potter-Kimball, Wyatt, Parker, Burgin and Jones68 one escitalopram, Reference Shalev, Ankri, Israeli-Shalev, Peleg, Adessky and Freedman27 and one fluvoxamine. Reference Spivak, Strous, Shaked, Shabash, Kotler and Weizman28 There were three tricyclic antidepressant trials, Reference Davidson, Pearlstein, Londborg, Brady, Rothbaum and Bell42,Reference Kosten, Frank, Dan, McDougle and Giller49,Reference Reist, Kauffmann, Haier, Sangdahl, DeMet and Chicz-DeMet66 and three monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) trials. Reference Katz, Lott, Arbus, Crocq, Herlobsen and Lingjaerde48,Reference Kosten, Frank, Dan, McDougle and Giller49,Reference Baker, Diamond, Gillette, Hamner, Katzelnick and Keller60 Another six trials assessed other antidepressants, Reference Davidson, Baldwin, Stein, Kuper, Benattia and Ahmed18,Reference Davidson, Weisler, Butterfield, Casat, Connor and Barnett44,Reference Davis, Jewell, Ambrose, Farley, English and Bartolucci46,Reference McRae, Brady, Mellman, Sonn, Killeen and Timmerman65,Reference Saygin, Sungur, Sabol and Cetinkaya67,A and a further ten trials assessed other agents. Reference Connor, Davidson, Weisler, Zhang and Abraham17,Reference Davidson, Baldwin, Stein, Kuper, Benattia and Ahmed18,Reference Davis, Davidson, Ward, Bartolucci, Bowden and Petty20,Reference Matthew, Vythilingam, Murrough, Feder, Luckenbaugh and Kinkead24,Reference Padala, Madison, Monnahan, Marcil, Price and Ramaswamy25,Reference Tucker, Trautman, Wyatt, Thompson, Wu and Capece29,Reference Yeh, Mari, Costa, Andreoli, Bressan and Mello30,Reference Butterfield, Becker, Connor, Sutherland, Churchill and Davidson39,Reference Braun, Greenberg, Dasberg and Lerer62,Reference Hertzberg, Butterfield, Feldman, Beckham, Sutherland and Connor63 The average sample size was 130 (range 13–538), the average age of participants was 41 years (range 18–82) and 54% of participants were women. The average duration of the trials was 12.4 weeks (range 4–36). Thirty-four studies were based in the USA, five were international, four were from Israel and there was one each from Brazil, China, Iran, South Africa and Turkey. The location was unclear in three studies. The predominant trauma (>50%) was combat in 13 studies, physical/sexual assault in eight, physical assault alone in four, sexual assault alone in four, natural disaster in two and road traffic accidents in two. For 18 studies participants had been exposed to various traumas with no one type accounting for over 50%.

Risk of bias assessments

Risk of bias assessments are included in online Table DS1. Fourteen of the studies included enough information on adequate random sequence generation to be judged as having a low risk of bias; the remainder were unclear. Only eight studies included an adequate description of allocation concealment. All 51 studies described themselves as ‘double blind’ but only eight provided sufficient information to judge the masking of participants, personnel and outcome assessors as being of low risk. Incomplete outcome data were addressed adequately in 15 studies. Thirty-eight of the studies were deemed to be free from selective reporting.

Efficacy of pharmacotherapy

Data from 21 studies (n = 3932) were available for inclusion in a meta-analysis of reduction in severity of PTSD symptoms for any SSRI v. placebo (Fig. 2). This found a small positive effect for SSRIs when grouped together. The results of meta-analyses for individual drugs, which had been tested against placebo in at least two RCTs, are shown in Table 1. Three drugs were significantly superior to placebo on either clinician- and self-rated PTSD symptom severity combined (paroxetine) or clinician-rated PTSD symptom severity alone (fluoxetine and venlafaxine). We found insufficient evidence to support the preferential use of individual agents in either combat-related or non-combat-related trauma (Table 2).

Discussion

This systematic review found statistically significant evidence on meta-analysis for three pharmacological agents v. placebo in the treatment of PTSD (fluoxetine, paroxetine and venlafaxine) but no evidence for brofaromine, olanzapine, sertraline or topiramate. Four drugs – amitriptyline, GR205171 (a neurokinin-1 antagonist), mirtazapine and phenelzine – showed superiority over placebo in single RCTs, whereas eleven did not: alprazolam, citalopram, desipramine, escitalopram, imipramine, lamotrigine, nefazadone, risperidone, tiagabine and valproate semisodium. When meta-analyses were undertaken by class of drug rather than individual drug, SSRIs were found to perform better than placebo. The absence of sufficient data precluded meta-analyses of other drug classes. The absence of difference in numbers of individuals leaving the study early for any reason suggests that the drugs included were well tolerated overall.

The effect sizes for pharmacological treatments for PTSD compared with placebo are low and inferior to those reported for psychological treatments with a trauma focus over waiting-list or treatment as usual controls. Reference Bisson, Ehlers, Matthews, Pilling, Richards and Turner14 They are, however, similar to those found for antidepressants for depression compared with placebo. Reference Leucht, Hierl, Kissling, Dold and Davis76 Unfortunately, the absence of a common control condition and head-to-head pharmacological v. psychological treatment trials makes comparison of the relative efficacies of these treatment approaches difficult. This is compounded by the fact that a significant number of participants in psychological treatment trials were continuing pre-existing pharmacological treatment at the same time.

It is well accepted that a well-masked, placebo-controlled trial is a tougher test for an experimental intervention than a trial with a waiting-list control. The UK’s NICE guidelines development group attempted to address this by determining a higher effect size threshold for psychological treatments than pharmacological ones (0.8 v. 0.5), 7 but it is unclear whether such arbitrary cut-offs may have introduced bias against either form of treatment. What is clear is the marked effect of the placebo in several of the trials reported in this review. For example, in the two venlafaxine studies the mean reduction in PTSD symptoms of those on placebo was greater than 40%. Reference Davidson, Baldwin, Stein, Kuper, Benattia and Ahmed18,Reference Hertzberg, Feldman, Beckham, Kudler and Davidson47 There is a need for RCTs of specific psychological interventions compared with an adequate non-specific psychological intervention. It is only through such trials and direct head-to-head comparisons that the relative effectiveness of differing treatment approaches could be established. The current meta-analyses are a later iteration of the

Table 1 Efficacy and tolerability of individual agents v. placebo

MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NA, not applicable; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RR, relative risk; SMD, standardised mean difference; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

a. The I 2 statistic is noted only when > 1 study as not applicable otherwise.

* P <0.05.

evidence used to determine what to recommend for recent WHO guidelines. 77 A WHO guidelines development group examined this evidence and recommended antidepressants as a second line of treatment of PTSD when psychological interventions with known efficacy did not work or were not available. The

Fig. 2 Meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors v. placebo (SMD, standardised mean difference).

recently updated Australian guidelines also concluded that pharmacological interventions should not be preferentially used as a routine first treatment of PTSD over trauma-focused psychological treatments. 78 There are various other reasons for considering the prescription of antidepressants, including

Table 2 Trauma type subanalysis of individual agents v. placebo

MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NA, not applicable; SMD, standardised mean difference; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

a. The I 2 statistic is noted only when >1 study as not applicable otherwise.

* P<0.05.

concurrent depression, lack of availability of psychological treatments, failure to respond to or tolerate psychological treatments and the personal preference of the individual with PTSD.

The variation in efficacy between different agents is striking and could be explained by a number of factors. First, there may be real differences between drugs, even those in the same family. For example, paroxetine’s superior efficacy over sertraline may possibly be explained by its increased dopamine receptor activity. Differences in the pharmacology of phenelzine and brofaromine are also marked, and grouping all drugs in one class together seems less desirable than considering each one individually. This confirms previous observation that class membership does not confer the same level of efficacy in the treatment of PTSD. Reference Stein, Zungu-Dirwayi, Van der Linden and Seedat11 This meta-analysis supports this assertion, with the SSRIs paroxetine and fluoxetine having better evidence of efficacy than sertraline. It is interesting to note, however, that despite failing to show superiority over placebo, sertraline showed equivalence to venlafaxine in one of the studies included.A This may be a result of the strength of placebo effect varying across studies.

The differences found between paroxetine and sertraline could be due to chance or lack of power, but it is noteworthy that over 1000 individuals were included in the meta-analyses of both paroxetine and sertraline, which suggests that power was not the issue. The same cannot be said for the majority of drugs reviewed, the evaluation of which was based on single RCTs with fewer than 100 participants. This review added 15 new RCTs to the evidence previously reported in systematic reviews but added no new trials for three of the four drugs recommended in the NICE guidelines (mirtazapine, amitriptyline and phenelzine). Of particular note is that new evidence resulted in drugs not recommended by NICE (fluoxetine and venlafaxine) now meeting the requirements laid down by NICE for recommendation as a second-line treatment. This review used particular rigour in assessing studies. Most of the other reviews that have concluded more favourably about pharmacotherapy grouped drugs from the same class together, Reference Foa, Keane, Friedman and Cohen10,Reference Stein, Zungu-Dirwayi, Van der Linden and Seedat11 did not include unpublished studies, Reference Jonas, Cusack, Forneris, Wilkins, Sonis and Middleton79,Reference Watts, Schnurr, Mayo, Young-Xu, Weeks and Friedman80 and adopted different inclusion criteria. 8,Reference Foa, Keane, Friedman and Cohen10,Reference Jonas, Cusack, Forneris, Wilkins, Sonis and Middleton79,Reference Watts, Schnurr, Mayo, Young-Xu, Weeks and Friedman80 This probably accounts for differences in conclusions between different meta-analyses despite apparently having the same raw data available. For example, sertraline performed significantly better than placebo in two recent meta-analyses, Reference Jonas, Cusack, Forneris, Wilkins, Sonis and Middleton79,Reference Watts, Schnurr, Mayo, Young-Xu, Weeks and Friedman80 which did not include the two unpublished studies included in our review.C,D

Study limitations

There were, however, some important methodological flaws in the studies identified in this review as illustrated by the risk of bias assessment undertaken. Clinical and statistical heterogeneity was apparent in the meta-analyses; this makes interpretation and generalisation across different trauma populations difficult. A major issue was that, despite having systematically tried to access unpublished data on the studies without ITT efficacy data, sufficient data for analysis were only available from only 41 of the 51 studies included. This raises the risk of outcome reporting bias. Reference Furukawa, Watanabe, Omori, Montori and Guyatt81 Incorrect definition of the ITT sample population was a problem. This is an important principle where data from every person who is randomised should be included in the analysis of efficacy. Participants might leave a study because of adverse effects, failed efficacy or greater symptom severity at baseline; not including their data in the analysis leads to bias, as a treatment might appear to be more effective than it is. Another important issue to consider is that this review considers drug monotherapy as opposed to drug or placebo in combination with psychological treatment. This evidence cannot, therefore, be used to consider whether or not pharmacotherapy augments psychological treatment for PTSD; many people with the disorder do receive both.

Several of the new studies identified by our search defined their ITT population as participants who received at least one dose of the study medication and received at least one post-baseline assessment. This could exclude some participants from analysis who had received treatment but not been assessed after the baseline. The most extreme case was a study of fluoxetine that defined ITT in this way, Reference Martenyi, Brown and Caldwell23 but measured PTSD symptom severity only at baseline and end-point, so was actually a completers sample. We decided to include these studies in our analysis but acknowledge that this affects the reliability of the results.

Implications

Pharmacological interventions for PTSD can be effective but the magnitude of effect unfortunately is small, and the clinical relevance of this small effect is unclear. This review supports the use of paroxetine, venlafaxine and fluoxetine as pharmacological interventions for PTSD. For most drugs, there remains inadequate evidence regarding efficacy for PTSD, pointing to the need for more research in this area to confirm the utility of pharmacological treatments for this disorder.

Appendix 1

Unpublished studies

Further details of the studies listed below are available from the authors.

-

A. Davidson J, Lipschitz A, Musgnung JJ. Venlafaxine XR and sertraline in posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. Appendix 14 of 2nd consultation draft for the NICE (2005) PTSD guidelines.

-

B. Eli Lilly. Unpublished data. Appendix 14 of 2nd consultation draft for the NICE (2005) PTSD guidelines.

-

C. Pfizer588. Unpublished data. Appendix 14 of 2nd consultation draft for the NICE (2005) PTSD guidelines.

-

D. Pfizer589. Unpublished data. Appendix 14 of 2nd consultation draft for the NICE (2005) PTSD guidelines.

-

E. SKB627 Bryson H, Lawrinson S, Edwards GJ, Grotzinger KM. A 12 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine in patients suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder.

-

F. SKB650 Bryson H, Dillingham KE, Jeffery PJ. A study of the maintained efficacy and safety of paroxetine versus placebo in the long-term treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Jorge Castro and Keiko Sakurai (World Health Organization interns) for assistance in multi-language searches.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.