In the late sixteenth century, Hugh Hall wrote a devotional guide that united his two vocations: gardener and Catholic priest. His A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge drew parallels between the work a man must do in soil or with gardening tools to the work the same man must do to rid himself of sin and to live a virtuous life. The Discourse is rich with analogies that unite the literal garden of soil, plants, and tools with the figurative garden of one’s soul and spiritual practice. Just as a gardener has to ‘consyder well, off the grownd he hath to deall withall…and how to hele the defectes that makes the grownd unfruyctfull’ a penitent must be a ‘carefull Gardener over his owne yearthe and to mark well the dysposytyon of his owne nature’.Footnote 1 Hall’s Discourse united horticultural practice with spiritual practice and addressed the interwoven secular and spiritual nature of humankind. As an author, he was one of several men who wrote on the blended nature of horticultural and spiritual practice. Just who he was, though, has been elusive because he was one of the many sixteenth century figures who left scant traces in the records. What we do know about him is largely due to his relationship with the Arden and Somerville families in Warwickshire and his connection to John Somerville’s plot against Elizabeth I. This article mines the available sources to examine Hall’s working life and his dual careers set into the context of the social and cultural world in which he lived. It argues that Hall’s identity, like his vocation, was a fusion of the secular and the sacred, of gardener and priest, and that his Discourse exemplifies that dual identity.Footnote 2 The purpose of this is to establish Hall’s identity and social world in preparation for further scholarship that examines in detail his Discourse.

Hall was a Catholic priest who worked primarily in post-Reformation Warwickshire and Worcestershire. He does not appear in the ordination records beginning in 1558, and thus must have been ordained in England late in Henry VIII’s reign or sometime in the reign of Mary I.Footnote 3 Men could not take religious orders until age 24, which means he was probably born between c. 1520-1533; that would place his ordination c. 1544-47 or 1552-1557 and his age at his death in the mid-late 1590s between 64-77 years of age.Footnote 4 There were at least four clergy called Hugh or Hugo Hall active during this time, none of whom are easily identifiable as the Hall who is the subject of this article. One was a deacon and then a rector in the Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield between the mid 1550s and early 1560s, another was appointed as clerk in Lincoln in 1559, yet another was a curate in the Diocese of Winchester between 1568-1574, and another was ordained as a deacon (1565) and a priest (1566) in the Diocese of Lincoln.Footnote 5 If our Hall was one of these men, he was probably the one working in the Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield, since that is the geographic area in which our subject was most active. It is equally possible that none of these clerics is the same one as our subject. Hall was probably ordained prior to Elizabeth I’s accession and as such he was considered one of the Marian clergy, a group that Elizabeth and her government hoped would die off and leave the kingdom quiescently Protestant.Footnote 6

The Marian clergy were a complex group. Some converted to Protestantism while others conformed to the Elizabethan Religious Settlement and took the required Oath of Supremacy even if they disagreed with the new theology. Others resigned their livings, unable to reconcile their convictions with the new order. Of those who resigned, some pursued a different career while others continued to serve English Catholics and developed the beginnings of an underground Catholic movement that was the hallmark of the seminary priests and Jesuits in the last twenty-five years of the sixteenth century.Footnote 7 The Marian clergy were also plentiful: there were more of them than there were Jesuits. Even in the last decade of Elizabeth I’s reign, Marian priests comprised at least 14% of the Catholic clergy known to be working in England; Patrick McGrath and Joy Rowe posit that the number was higher, but the clandestine nature of dissident clerical work makes exact figures difficult to determine.Footnote 8 Hall was among the Marian clergy that at least some men in the political establishment recognised as a potential threat. He was, according to one report, ‘a most dangerous practiser, a conuayour of intelligence to all the Capitall papistes in these partes, a resorter to them under the cloke of a Gardiner, converteth, reconcilethe, confessethe saithe masse’.Footnote 9 Despite the potential threat, there is only one extant record of state prosecution of him, related to the Arden-Somerville Plot discussed below.

When Hall appears in modern scholarly treatments, it is as a supporting actor rather than as the focus of the analysis. Hilary Turner and Neil Younger have mentioned Hall’s role in the Sheldon and Hatton households, for example, but the purpose of their articles was not to examine Hall.Footnote 10 Recent scholarship by Cathryn Enis and Glyn Parry, both as individual authors and as collaborators, has offered more perspective on Hall than what we previously had. Cathryn Enis placed Hall at the heart of a network of powerful and ancient Catholic families who were implicated in the Somerville Plot in 1583. Enis demonstrates that Hall was known to the Elizabethan state and his movements on the continent were reported to Burghley.Footnote 11 Glyn Parry has noted that Hall’s presence among West Midlands Catholic families and his connection to Hatton ‘linked court politics with Leicester’s persecution’ of the Arden family.Footnote 12 Parry and Enis’s coauthored volume on Warwickshire politics makes clear how a middle-aged Marian priest’s private speech could be appropriated for political purposes by figures on both sides of a debate, and how those words became a central focus of the earls of Leicester and Warwick as they carried out their campaign against some of Warwickshire’s most powerful gentry families.Footnote 13

The present article centres Hall in the analysis and asks not only how his dual careers shaped his identity, but also how early modern conceptions of masculinity and worthwhile labour influenced that identity. Early modern manhood was formed through multiple sources of male identity, such as age, social status, marital status, vocation, reputation, wealth, and power.Footnote 14 For most men, the household was the ‘crucible of patriarchy’, the space in which manliness was forged and performed.Footnote 15 For clerics, both the church and the household were spaces of masculine performance. Both spaces were steeped in patriarchal structures: one of the church and the other of the family and society. Catholic clerics in Protestant England, however, had been forced out of traditional worship spaces and into makeshift chapels in households, where their lives and the security of the household was constantly under threat of discovery. Thus, the crucible of patriarchy for post-Reformation Catholic priests was available in only one kind: the household over which they exercised spiritual authority. Post-Reformation Catholic clergy had to operate under unusual circumstances wherein they were often protected and supported by women. Despite an arrangement that inverted traditional gender hierarchies in the social space of the household, this arrangement did not emasculate priests nor did it subvert the gender order. Instead, necessity prompted these men to develop alternative forms of manhood that took into account the unique circumstances within which they worked.Footnote 16 For Hall, these alternative forms were founded on mastery of his profession as a gardener and the spiritual leadership he provided to selected households in the West Midlands. Hall’s manliness was located in his dual vocations, the secular and the sacred.

Hall’s dual identity reflected contemporary trends in botany and horticulture, particularly the fusion of gardening and religion. From the late medieval period through c. 1700, gardening and religion were connected in both text and practice. Sixteenth century English people were enthusiastic gardeners in both rural and urban settings, for foodstuffs, aesthetics, and a potent spiritual purpose. The designs, plants, colors, and scents within medieval and early modern gardens symbolised aspects of religious belief and functioned as spaces wherein individuals could meditate, exercise their piety, and hone their overall spiritual life.Footnote 17 In the sixteenth century, Catholic and Protestant clergy agreed that working in a garden drew the faithful closer to God, and even brought people struggling with atheism back to the fold.Footnote 18 Botanical authors frequently invoked imagery of the Garden of Eden and Adam and Eve during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 19 In the 1560s Levinius Lemnius produced a Biblical herbal which connected botany and gardens to interpretations of religious texts; English editions appeared beginning in 1587.Footnote 20 Clerics on the continent, such as Hieronymus Bock and Otto Brunfels, left their monastic orders to pursue interests in botany, gardens, and Protestantism. Bock managed the gardens of Count Palatine Ludwig; his Kreütter Buch, or Book of Plants, was drawn from his observations of those gardens.Footnote 21 Brunfels quit his Carthusian monastery and became a Lutheran minister and later the city physician of Bern, a profession that required specialist training and copious knowledge of botany and gardens.Footnote 22 The prologue to William Turner’s A New Herball emphasised the role of religion in the lives and careers of botanists and gardeners.Footnote 23 Turner was a nonconformist in the reign of Henry VIII. He left England for the continent during the post-Reformation period of Henry’s reign, returned under Edward VI, left again during Mary I’s reign, and returned under Elizabeth I. He dedicated his New Herball to Edward Seymour, Protector Somerset and dedicated some later work to Elizabeth I. Hall was thus in good company with other educated clergy-botanists, Catholic and Protestant, in his impulse to unite religious and botanical themes in his Discourse and his careers.Footnote 24 He was, however, unique in his practice as a Catholic gardener whose skill resulted in commissions even from high-ranking Protestant statesmen in a Protestant realm: no other priest-gardener appears in historical records for the late Elizabethan period and although Hall trained other gardeners, extant documents do not refer to them by name.Footnote 25

Although extant sources for Hall’s life and work are minimal, they come from a range of source types and perspectives: personal correspondence, government correspondence, intelligence reports, and interrogatories. Taken together, these allow for a partial reconstruction of his working life. Correspondence between Sir William Cecil and his steward, Peter Kemp, suggests Hall was working on the gardens at Burghley House near Stamford in October 1561. Kemp complained that he and the priest working on Burghley’s orchard disagreed on how to proceed with preparing the orchard for planting.Footnote 26 Kemp did not name the priest, but Hall was the only priest-gardener known in the region at this time and it is probable that this unnamed priest was him. At the same time, Cecil was making inquiries about a gardener from the continent. Sir Thomas Windebank wrote from Paris on 14 October 1561 to say he would inquire ‘for a gardener & thinges for your garden’.Footnote 27 Two different sources, one ecclesiastical and one state document, put Hall in France in 1580: the Douai Diaries noted him as a visitor to Rheims and intelligence gathered by William Herle placed Hall at Rouen.Footnote 28 Propaganda offers another piece. Leicester’s common-wealth, printed in 1584/5, mentions Hall as ‘Hatton’s priest’; this source has to be approached with caution for the kind of document it is, a propaganda piece attacking the Earl of Leicester, but the mention of Hall as Hatton’s priest aligns with similar claims from other sources.Footnote 29 The richest information on Hall’s ministry within West Midlands Catholic families appears in the state’s interrogatories of Hall and the Arden and Somerville families in connection with their purported plot against the queen in 1583.Footnote 30 These state records offer a view into Hall’s relationship with the extended household of the Ardens and with their son-in-law John Somerville, discussed in detail below.

Hugh Hall and the social world of the West Midlands

Extant records do not definitively tell us where Hall was born, who his family was, or explain his connection to the Halls of Idlicote, Warwickshire, ten miles southeast of Stratford-upon-Avon. Parish records for Idlicote do not contain entries for Hall and he does not appear in the Visitations of Worcestershire for 1569 or the Visitations of Warwickshire for 1619.Footnote 31 Still, significant evidence suggests that Hall was a relative of the Halls of Idlicote and that he was resident in the parish. The Halls were part of a network of Catholic families. They were cousins of the Somervilles, connected to the Underhills through the marriage of Elizabeth Hall to Simon Underhill and through the Underhills, connected to Sir Christopher Hatton.Footnote 32 Through Sir Ralph Sheldon the Halls were part of a wider network of Catholics that included the Ardens, Catesbys, Throckmortons, Treshams, and the Catholic lawyer Edmund Plowden, some of the same families for whom Hall or his trainee gardeners worked.Footnote 33 In November 1583, a letter referencing Hall mentioned that John Somerville’s mother was ‘at Hall’s house in Idlicote,’ the writer clearly meaning the priest’s house, as he was the only Hall mentioned in the communication.Footnote 34 The Hall family’s presence in Idlicote throughout this period continued at least through Richard Hall’s death in 1602. The presence of a house in the parish identified as that of Hall the priest establishes a probable kinship connection between him and the Halls of Idlicote, and places Hugh Hall’s residence within that community when he was not resident with the families who employed him.

Hall’s network extended beyond the families mentioned above. From at least the 1560s, he was part of a network of Midlands families with interests in gardening. Most of them were Catholics but some of his clients were Protestants who were willing to overlook his religious identity because they valued his talent as a gardener. As Rebecca Bushnell has argued, ‘the growing appetite for … a stately house and a stunning garden, intersected with the desire that fueled social ambition, since it was implied that possessing such things signaled social advancement’.Footnote 35 Gentry in the position to commission gardens that aligned with their social ambition would have hired the most talented gardeners they could, which underscores how they must have valued Hall. Between 1569-1583 Hall worked for a succession of elite Catholic families in Worcestershire and Warwickshire, including the Talbots of Grafton, the Throckmortons of Feckenham, Lord and Lady Windsor at Tardebigg, the Sheldons at Beoley, and the Ardens of Park Hall.Footnote 36 Garden commissions drew him to Northamptonshire, too. He appears to have worked for Sir William Cecil (later Lord Burghley) in the early 1560s and he was in Sir Christopher Hatton’s employ in the late 1570s and early 1580s.Footnote 37 Both of these men had the means and access to hire the best garden designers in the realm, which underscores the esteem in which they must have held Hugh Hall. Since Hatton sought to pay homage to Burghley by replicating the latter’s architectural and garden designs it makes sense that Hatton would hire Hall as his surveyor of works, given the gardener’s experience at Burghley House and as surveyor of works for the Ardens. Furthermore, as the builder of one of the grandest gardens in England at the time, Hatton would have sought out the best available surveyor and gardener for that project.Footnote 38 That he hired Hall indicates the high regard in which the latter was held. In anticipation of Burghley’s visit to Holdenby in 1579, Hatton asked Burghley to inform his surveyor of any ‘lackes and faultes’ in the ongoing construction at Holdenby.Footnote 39

Hall’s social world was a network of Catholic families who were connected by friendship and kinship. The Sheldons and Throckmortons intermarried through three generations in the sixteenth century alone. In 1555, the widowed Margaret Whorwood wed William Sheldon of Beoley and her daughter, Margaret, married Thomas Throckmorton of Coughton, in Warwickshire.Footnote 40 Two years later, Sir Robert Throckmorton’s daughter and Thomas’s sister, Anne, married Ralph Sheldon. Therefore, Margaret Whorwood Sheldon was mother-in-law to Anne Throckmorton Sheldon and her brother, Thomas Throckmorton. Her daughter, Margaret Whorwood Throckmorton, was sister-in-law to Thomas, Anne, and the other nine siblings in their sibling group. Members of these families socialised and, at the end of life, left each other bequests and served as executors for one another’s wills, leaving little doubt that they were friends as well as kin. William Sheldon, for example, named Sir Robert Throckmorton as one of his executors and bequeathed him £20 for his ‘paynes’, an act that was usual between friends and trusted kin.Footnote 41 The Throckmortons were also close to the Talbots, Windsors, and Treshams. Sir John Throckmorton of Feckenham and John Talbot were among Lord Windsor’s closest friends and served as two of the executors to his will.Footnote 42 When Sir John Throckmorton died in 1580 he left his ‘deere freende’ John Talbot his ‘best Corslett of proofe that serveth for myne owne bodye, and a case of Pistolles’.Footnote 43 Throckmorton’s niece, Mary Throckmorton Arden, was mother-in-law of John Somerville, the man at the center of the Somerville Plot. Arden’s husband, Edward, was Sir Christopher Hatton’s cousin, related through intermarriage between the Ardens and Hatton’s maternal relatives, the Saunderses.Footnote 44 These relationships endured across generations. Sir Thomas Cornwallis was a guest of the Sheldons at Beoley in the 1570s. When he made his will in 1605, he put money in trust for his youngest daughter into the custody of an older daughter, one of his sons, two cousins, a nephew, and his friend Ralph Sheldon.Footnote 45

Hall’s employments reveal these social ties as well. His religious career was spent mostly in the West Midlands, in kinship and social networks that spanned Worcestershire and Warwickshire. Through those same networks, his career as a gardener drew him to Northamptonshire for specific commissions. In addition to Hall’s employment with Cecil and Hatton, one of Hall’s students worked for Mary, Baroness Vaux and perhaps also for her brother, Sir Thomas Tresham. Hatton was one of Tresham’s patrons, and both Vaux and Tresham were related to John Throckmorton, who was Lady Tresham’s uncle.Footnote 46 Servants commonly moved between families in the same social network, entwining social and economic worlds as we see with Hall. Given his skill and reputation, which is borne out by his employment with leading gentry and Hatton in particular, Hall probably had additional commissions for which documentation has not survived.Footnote 47

After two decades serving as gardener to elite families in Worcestershire, Warwickshire, and Northamptonshire, and at least occasionally as priest to the Catholic families, Hall was arrested in connection with the Arden-Somerville plot to assassinate Elizabeth I. In 1583, Hall was in Sir Christopher Hatton’s household at Holdenby when a request arrived from John Somerville, the son-in-law of the Ardens of Park Hall, Warwickshire. Hall had been in the Arden’s household in 1575/6. William Thacker, a Somerville servant who had previously worked for Arden, testified that he had met Hall at Park Hall ‘about vij or viii yeares past…whom he tooke for a surveyour of wourkes’ rather than a priest.Footnote 48 Hall continued to visit the Ardens after he left their employ; whether these visits were to perform clerical duties, consult on plants or gardens, or simply as sociability the evidence does not say. On at least one occasion, though, the politically-charged content of Hall’s speech while visiting the Ardens contributed to a cataclysmic event for the Ardens and their daughter’s marital family, the Somervilles.

The Arden-Somerville case has been rigorously examined by Cathryn Enis and Glyn Parry, so this essay will mention only the details pertinent to our understanding of Hall.Footnote 49 In October 1583 Hall was with the Ardens at Park Hall and ‘delivered certayne speaches…that towched hir Majesty greatly in honour’.Footnote 50 To speak so freely suggests that Hall was a close friend or confidante of his hosts, especially since he was not their social equal. The Arden’s daughter, Margaret, later related the conversation to her husband, John Somerville, whereupon an upset Somerville, already struggling with a bout of mental illness, decided to travel to London to assassinate the queen. Thomas Wilkes, a clerk of the Privy Council charged with investigating the case in Warwickshire, reported that Somerville’s ‘mynde was greatlie troubled, insomuche that he could not sleepe’.Footnote 51 Prior to his journey Somerville sent to Hall at Sir Christopher Hatton’s Holdenby estate to request confession and absolution but the priest declined on the grounds of a sore leg that prevented him traveling.Footnote 52 When Somerville was arrested en route to London and interrogated by government officers, he named Hall’s speech at the Arden’s Park Hall, which he had heard secondhand, as the impetus for his decision to kill the queen. Along with the Ardens and Somervilles, Hall was indicted for treason. John Somerville died in prison, Edward Arden was executed, and shortly afterward Hall, Mary Arden, and Margaret Somerville were released.Footnote 53 Hall’s release was probably achieved through Hatton’s intervention; Glyn Parry posits that Hatton saved Hall’s life by sacrificing Somerville.Footnote 54

Between 1584-1597 Hall lived quietly enough not to appear in official records. During this time he did not appear in family papers of his usual network of West Midlands Catholic families and was probably resident in the noble household of the Catholic, and sometimes recusant, John, Baron Lumley at Nonsuch. This was probably the period during which he wrote his Discourse, for which he needed a well-stocked library with a substantial collection of religious texts. Several factors point to the very real possibility that Hall spent these years in Lumley’s household or as his guest: the nobleman’s reputation for hospitality, Lumley’s own previous brush with treason, the vast resources of Lumley’s library, and the disposition of Hall’s manuscript in that library. Lord Lumley’s reputation for munificent hospitality is borne out by the frequent invitations he offered to friends and fellow county officers to ‘dine and sleep’ at his houses. In 1583, for example, he suggested that the men attending a meeting about the county musters could stay at Nonsuch and somewhat playfully quipped ‘not for any other respect than to have yourselves to be refreshed with the sight of your best dogs to be outrun by my lazy deer’.Footnote 55 In other words, Lumley offered the type of munificence expected of the nobility, but also seemed to have truly enjoyed having friends (and possibly also clients) to stay. For Hall, residence in a household with greater wealth and resources than his previous hosts possessed and with the financial support and physical protection Lumley could provide would have been ideal in the aftermath of his legal troubles. Having been tortured on the rack during the government’s investigation of the Somerville Plot, Hall might have sustained injuries that compromised his ability to work, and in any event he was probably content to keep a low profile after his narrow escape.Footnote 56 Furthermore, Lumley might have been sympathetic to Hall’s circumstances since Lumley himself had been accused of treason for his involvement in the Ridolfi Plot in 1571. Despite his Catholicism, Lumley had gradually worked his way back into a position of trust with the queen and her government. Perhaps he felt sympathy for, or even a sort of kinship with, the disgraced priest.

The Lumley Library and gardens would have been valuable resources for Hall as he worked on his Discourse. The library contained over 3000 items and was rich in theology, history, liberal arts and philosophy, medicine, cosmography and geography, law, and music.Footnote 57 Lumley’s patronage of artists and writers included liberal use of his library, to the extent that he had a handlist drawn up ‘for the use of his friends’.Footnote 58 Hall’s completed manuscript, of which there is only one known copy, was in Lord Lumley’s library, which strengthens the probability that the treatise was written under Lumley’s patronage.Footnote 59 It was not unusual during this time for writers to leave only a manuscript copy rather than a printed version. Printing was expensive and labour intensive, so much so that even the best-known naturalists who made up London’s scientific community in Lime Street in London did not print their findings.Footnote 60 The timing of Hall’s Discourse would also coincide with Lumley’s residence at Nonsuch Palace, which he held from c. 1580-1592 and at which he constructed extensive and lavish gardens. Martin Biddle hypothesises that the gardens were in a maintenance phase after 1585, since once Lumley understood he would not retain the property he was unlikely to invest more revenue into further developing the gardens.Footnote 61 Whether the gardens were being actively remade or simply maintained, they would have been useful to Hall as he conceptualised, contemplated, and drafted his Discourse, regardless of whether he was a houseguest or in Lumley’s employ.

Hall’s horticultural expertise was known beyond the confines of West Midlands estates and Hatton’s Holdenby, as evidenced by at least two other Northamptonshire gentry families employing a gardener Hall had trained. In 1597, Sir Thomas Tresham of Rushton, Northamptonshire directed his stewards, George Levens and John Slynne, to send to his sister, Lady Vaux, who had a gardener in her employ who had been trained by Hall at Holdenby. Tresham referred to Lady Vaux’s gardener as one who had been ‘breed upp as I hear under Mr. Hall (ye preeste who lately dyed, and excelled in gardening worke) in Holdenbury workes’.Footnote 62 This indicates that Hall was known in the area as a priest and gardener, that he was involved with the daily operations at Holdenby to a degree that he was training other gardeners as a master would train apprentices, and that he died in 1596 or 1597. This source also confirms his connection to a wider network of elite gardens in the Midlands. Hall’s Discourse, undated but written in late sixteenth century hand, is the only time we hear his own voice, unmediated by government agents or estate stewards.

Priest and Gardener: Hugh Hall’s Identities

The connection between individual identity and occupation is an emerging field of inquiry, and the connection of gender to occupational identity has particular need of scholarly attention. English people in the sixteenth century identified themselves and each other through a complex blend of factors that included social, economic, and marital status, religious belief and practice, education, hobbies, gender, and occupation. Identity was deliberately constructed; it was intentional on the part of an individual and yet also shaped by external forces, by other people’s definition of an individual.Footnote 63 Alexandra Shepard has demonstrated that an individual’s control over their identity, including their honesty and credit, depended on their status in the social hierarchy. The poor, for instance, ‘appear to have had far less agency than their wealthier neighbours over the terms of their own worth and identity’.Footnote 64 Hall was not poor. He seems to have amassed enough wealth to keep his own house in Idlicote even if he did spend extended periods in residence at the homes of his employers and patrons. Still, the families for whom Hall worked and with whom he socialised shaped external perceptions of his identity. As Mark Hailwood has argued, the contemporary connection between identity and occupation was so ubiquitous that broadsides and ballad discourse emphasized the connection between the two in the process of identity formation.Footnote 65 Clerical identity underwent significant transformations between c. 1560-1660 as clerical work became increasingly regarded as a professional endeavour.Footnote 66 For clergy of all confessions, vocational preparation, piety, and professional ethos became highly valued aspects of identity. Wietse de Boer and Ellen A. Macek have emphasized the similarities in Protestant and Catholic clerical identity during this period, especially insofar as all clergy experienced the same expectations and pressures of professional reordering regardless of confession.Footnote 67

Clerical identity also shaped and was shaped by expectations of gender. As clerical identity shifted during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so too did the requirements of clerical manhood. For both Protestant and Catholic clergy, highly-valued masculine traits were articulated through the successful performance of one’s profession, thereby fusing professional and gender identities. Hall’s external identity, and probably also parts of his internal identity, were shaped by his status as a practitioner of an outlawed religion, his refusal to conform to the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, and his close relationships with Catholic families. His Discourse reveals that his internal identity, the view he held of himself, leaned heavily on his education and preparation for his professional life, his piety, and his expertise with botany and gardens.

Shifts in clerical identity occurred across the confessional spectrum and both Protestant and Catholic clergy were affected. Individually and corporately, clergy influenced and were influenced by these changes. Instead of inhabiting a ‘web of horizontal community relations’ as had late medieval, pre-Reformation clergy, the post-Reformation cleric became ‘an agent of a vertical hierarchy’.Footnote 68 Post-Tridentine English Catholic clergy experienced this change, too. They were members of a professional class and yet the increasing anti-recusancy laws made these clerics both pastoral workers and political figures. Advice manuals for Catholic clergy emphasised piety, exemplary conduct, avoiding political entanglements, and the importance of writing commonplace books and books of sermons as a meditative and devotional aid.Footnote 69 Although most of this advice remained static between 1560-1660, late sixteenth century Catholic writers like the Jesuit lay associate George Gilbert cautioned against engaging in disputations or overt attempts at conversion. Instead, Gilbert urged priests to offer sermons designed to inspire self-reflection so that the hearer might meditate on the direction of their life.Footnote 70 In other words, Gilbert advocated for Catholic priests to provide the conditions that could encourage conversion, but that would allow clerics to avoid overt attempts at conversion. Such a strategy would allow priests to sidestep laws that made conversion a treasonable offence. Later Catholic writers, such as Richard Smith and George Herbert, reflected not only Gilbert’s advice, but also the practice of the generation of clergy that came before them. Smith and Herbert, writing to recusant clergy and conservative clergy, respectively, directed their readers to compose their own books of meditations, spiritual instructions, devotions, and sermons.Footnote 71 These books would enhance a cleric’s own preparation and spiritual fitness and could, if disseminated or published, have a positive spiritual influence on their followers, too.

Hall’s clerical identity and practice aligned with Gilbert’s advice, especially in regard to writing out one’s meditations or spiritual instructions. Hall’s Discourse skillfully integrated spiritual meditations drawn from the Bible and medieval religious commentaries by writers such as Isidor of Seville and Augustine with horticultural knowledge, garden design, and the use of garden tools.Footnote 72 As examples discussed below reveal, this integration was thorough; for example, the use of one’s spade or gardening shears was infused with spiritual relevance. According to Hall’s text, all actions had dual secular and spiritual relevance.Footnote 73 Through his Discourse Hall professed his clerical identity by making clear his piety, education, preparation, and claiming a commitment to right behaviour, honour, and reputation. He used that same document to claim his identity as a gardener, especially through his detailed advice on planting, design, and the tools a gardener needed to cultivate a robust and successful garden. The Discourse establishes Hall’s honour and reputation through extensive knowledge and expertise in multiple, overlapping professions. Through his own articulation of those attributes, Hall constructed and performed the gendered expectations of his manhood through his dual careers, by demonstrating mastery of each aspect of those careers.

Garden design and labour engaged Hall with the professions through both architecture and medicine. Garden design was a subset of architecture in the late English Renaissance; botanical knowledge, while part of natural philosophy, was also part of the medical profession.Footnote 74 Both of these vocations fell under the umbrella of learned professional training. Hall was of course not trained as a physician, yet during the sixteenth century both clergy and laity ‘were deeply concerned with the health of their souls … [and] with their physical health’.Footnote 75 As mentioned above, the German botanist Otto Brunfels was trained as both a cleric and a physician; another expert German botanist, Leonhart Fuchs, was trained as a physician as well. In the sixteenth century, natural philosophy, which included the study of botany, was part of the wider field of medicine.Footnote 76 Rosemary O’Day argues that the ‘learned professions grew out of a philosophy of life’ that included a perspective of ‘work in terms of vocation, service and commitment rather than of simply earning a living’.Footnote 77 With this is mind, the care Hall demonstrated for one’s spiritual and physical health were steeped in the professions, as evidenced by his knowledge of theology, botany, and garden design, and his work as a cleric, garden designer, and gardener.

In the sixteenth century, priests commonly sought out additional sources of income to supplement their meagre livings. By-employments or secondary careers, such as gardener or surveyor of works, could be significant to poorer clerics since the secondary income could keep one financially solvent. K. Tawny Paul has argued that by-employments often meant more to individuals than mere financial supplements and that multiple careers were common for most non-elite premodern English men and women; each of an individual’s different occupational identities played a role in that person’s life and those often changed across the life course.Footnote 78 A person’s occupation shaped their identity, reflected God’s intentions for an individual, and produced a sense of satisfaction.Footnote 79 Work provided ‘a sense of dignity and purpose’, demonstrated a man’s honour and respectability, and confirmed his manhood by his ability to make a living.Footnote 80 To gain a real sense of a person’s identity, however, we should pay attention to how ‘individuals classified their own activities’ – how they defined their own work-based or occupational identities.Footnote 81 For individuals who considered their vocations as a manifestation of divine grace, that vocation might have had a stronger imprint on their sense of self, meaning that what they did might have influenced who they thought they were. Hall’s dual identity as priest and gardener was a common theme throughout his working life, both in terms of how others saw him and how he regarded himself, or what we might call his external and internal identities.Footnote 82

Contemporaries tell us that one’s occupation also imprinted on the body because of how one used their body to perform their work. Bakers and tailors were known by their legs, miners by their skin, and watermen by musculature on the hands and arms. Samuel Johnson observed that a man’s occupation was evident in his appearance, that ‘one part or other of his body, being more used than the rest, he is in some degree deformed’.Footnote 83 The body and hands of the upper sort would have signaled their status through the absence of those physical markers of strenuous physical work. Without question, the arduous labour in garden work would have shown itself on Hall’s body. His Discourse makes clear that working a garden was demanding corporeal labour. Digging at the earth with spades, using a mattock to chop or pick at the earth, removing rock and rubble, and rearranging soil into garden beds, mounts, and orchards, in addition to setting and tending plants and hauling sprinkler lines, required use of one’s entire body and would have resulted in well-developed arm and back muscles. This labour could have worn down a body from hard use. Sir Henry Slingsby thought that the death of his gardener, Peter Clark, was hastened by ‘extreme labour [that] shortened his days’.Footnote 84 That labour, the strength required for it, and any marks on his body as a result of that work, also emphasized Hall’s manliness and confirmed his masculine identity. Like other early modern people, Hall quite literally wore his occupational identity.

For gentry and nobility interested in gardens, Hall’s main identity was a gardener who had once been or perhaps still was a priest. For Catholics, his identity as a priest would have been enticing for the spiritual symbolism he could weave into their planted landscapes and for the spiritual care they might have from him through those spaces, and perhaps also administration of traditional religious rites. The few times we hear people refer to him in the sources, they identify him first as a priest, secondly as a gardener. In keeping with contemporary practice, most people referred to him as Mr. Hall, as they referred to Marian and suspect priests even into the Elizabethan period, so the lack of ‘Father’ as a title cannot be taken as evidence of a secular or religious identity.Footnote 85 Hall seemed to view himself in terms of the dual identity of priest and gardener. His Discourse reveals that his sense of self was steeped in spiritual contemplation and the possession of a deep well of knowledge of religious texts, at least equal to his mastery of gardens and his knowledge of botanical and horticultural texts.Footnote 86

Until his arrest in 1583 Hall performed some clerical duties for the families with whom he lived, although his time was mostly occupied by work in the gardens. Kemp’s letter makes clear that the priest-gardener at Cecil’s Burghley estate was outdoors working with the earth or directing labourers to do so; of course he would not have carried out clerical duties for a Protestant employer. As surveyor of works for the Ardens his attention would have been consumed by landscape work rather than that of a priest, but there are indications that he continued to provide spiritual care in at least a limited scope. Somerville’s request for Hall to hear his confession and administer the sacrament implies that the priest at least occasionally still provided spiritual care. Government officials certainly thought so when they investigated him and found him to be worryingly influential in ministering to Midlands Catholics. Hall denied such activities on the grounds that he lacked the authority to reconcile (convert) anyone to the church, but admitted that he had heard confessions, although only of ‘mene in the catholike church allredy’.Footnote 87

By the early 1580s Hall’s reputation as a gardener was well established as was his experience managing large projects as surveyor of works. He was in demand because of those skills, which he had cultivated into a professional identity that rivaled, and perhaps exceeded, his clerical identity. He established his reputation with the Ardens and Sheldons before going to work for Sir Christopher Hatton at Holdenby. While he was at Holdenby, other gentry called in to consult with him on their gardens. For example, in late summer 1582, Sir Thomas Cornwallis visited Hall at Holdenby to discuss his own gardens and orchard. He communicated with Hall at least once after that, when in late spring 1583 he wrote with additional questions about a garden. When the state questioned Cornwallis about his relationship with Hall, he insisted that he ‘had no conference of him of anything but of gardens and orchard’.Footnote 88 The men seem to have initially met at Sheldon’s house at Beoley. In the depositions after the Arden-Somerville affair, Hall admitted to having been at Beoley in the late 1570s and early 1580s. He acknowledged saying Mass there c. 1578 but denied doing so in late summer of 1582, when Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who was a guest there, asked him to do so. It was probably through the Sheldons that Cornwallis learned of Hall’s skill as a gardener and surveyor of works. It makes sense that a Catholic priest implicated in a treasonous plot would deny he performed religious rites. Indeed, after the passage of new laws in 1581 prohibiting the saying or singing of Mass, to admit doing so risked financial and bodily penalties of 200 marks and imprisonment for one year.Footnote 89 Hall also denied that he administered confession and absolution to John Somerville. Yet in that same interrogation he admitted that he had said Mass and heard confession in years past, although not with the intention of converting anyone since he only ministered to those who were already Catholic. Still, that local Catholics requested that Hall say Mass and hear their confessions suggests that for some people his clerical role was still a significant part of his identity.

Prior to the Reformation, training as a cleric offered multiple career pathways. One might join a religious order, pursue the pastoral ministry as a parish priest, or pursue a career in an occupation or service. The Reformation removed the possibility of religious orders in England and deprived of their livings priests who refused to follow the state’s mandate to become Protestant ministers. Even before the Reformation, supplementary incomes had been necessary for a substantial segment of the pastoral clergy. Income for parish priests varied widely and the sixteenth century was marked by high levels of clerical poverty. Slightly more than one third of clerical livings paid less than £5 per year, below the subsistence level; 17% were valued between £5 and £10 per year, 44% were valued between £10-30 per annum, while only 4% of benefices paid more than £30 per annum.Footnote 90 For some post-Reformation Catholic clergy, the skills that provided supplementary income led to a new career or to occupational plurality. In the first decade of Elizabeth’s reign, priests who refused to accept the new queen’s religious settlement were either ejected from their livings or resigned those livings in protest. Now without employment or housing, these men had to rely on existing extra-clerical skills or develop new ones. Hall’s vocation as a gardener might have originated out of necessity during Edward’s or Elizabeth’s reign or from his own enjoyment of gardening and botany. At the time of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, as a Catholic priest in a Protestant realm, Hall would have had to conform to Protestant reforms, escape to Catholic Europe, or cultivate an alternative vocation. However it started, the creation of landscapes had by the last quarter of the sixteenth century become a significant part of his work, which prominent gentry in Worcestershire and Warwickshire, and statesmen in Northamptonshire, hired him to do.

Hall exemplifies the transition from medieval to early modern forms of the clerical profession: from pre-Reformation Catholic organization of the clerical estate to post-Reformation member of the professions, a class that included lawyers and clerks. Both pastoral and non-pastoral professional identities and careers reflected the education clerics received in the universities and their continued accumulation of knowledge throughout their careers. Although gardeners were typically identified as labourers, Hall’s gardening career was steeped in the professions and reflects both a high level of education and continued study of religious and natural philosophy texts, as is made clear by his mastery of those texts, detailed in the discussion of his Discourse below. The libraries of the families he lived with and worked for would have included such texts as they were among the most fashionable of the time; part of their appeal was to display a family’s education and cultural currency as humanists. The Lumley library contained numerous copies of Aristotle, Cicero, and Pliny, dictionaries of several European languages, and herbals that contemporaries used for both gardens and medical knowledge.Footnote 91 The Tresham library, substantial although smaller than Lumley’s, featured many of the same books.Footnote 92 The combined library of the Treshams and the Brudenells of Deene, Northamptonshire, who acquired the Tresham collection through marriage, held at least 1900 volumes.Footnote 93 The other families with whom Hall lived and for whom he worked would certainly have had substantial libraries as well. Elite families allowed servants in specific roles, such as overseers, to use their libraries. For example, Robert Stickells used the architectural books in Tresham’s library at Rushton Hall when he was working on designs for some of Tresham’s new buildings in the 1590s.Footnote 94 Hall must have used Lumley’s library as he wrote his Discourse, since many of the works he cited were in that collection: Bernard of Clairvaux, Isidor of Seville, and books he did not cite but clearly had knowledge of, like Pliny’s Natural Histories and botanicals by Leonhart Fuchs, William Turner, and Conrad Gessner. The Discourse does not contain a dedication, but Hall’s gift of his treatise to Lumley is another indication of the nobleman’s support, perhaps even patronage, of the priest-gardener and his work.

During the Elizabethan period, Protestant authorities perceived the identity a Catholic priest derived from his by-employment as a disguise and an attempt at subterfuge to deceive the state. Priests who worked as schoolmasters, stewards, or gardeners in Catholic households (as a few examples) were often described as using those positions as a disguise to conceal their true role in a household, thus deepening their deception to the community and polity in which they lived. Officials’ concerns regarding clerical disguise predated underground Catholic worship. Prior to and during the Reformation, lay and ecclesiastical authorities dealt with complaints that some clergy concealed their status by wearing lay clothing and living as a layperson.Footnote 95 The idea of clerics disguising themselves in order to conceal their status was therefore ingrained in English culture by the time Protestants imputed this behavior to Catholic priests in the 1580s. As a matter of safety, Catholic priests usually traveled in disguise when they journeyed to or from the continent and when they moved around within England. The Jesuit Henry Garnet, for example, disguised himself as a gentleman and sometimes traveled with one of his protectors, Anne Vaux, while pretending to be her brother.Footnote 96 Some priests did conceal their pastoral role in a household; as the laws increased against Catholic priests working in England those disguises were sometimes a matter of life or death. Legal statute permitted Marian priests to continue working as clergy, however, so there would have been no need for Hall to conceal his identity, as Thomas Wylkes had accused him of doing in 1583.Footnote 97 Ultimately, the focus on disguise discounts or denies the non-clerical roles that clergy played in houses throughout the realm and the reality of secondary or multiple vocations.

Priests often had skills they could use as by-employments or develop into plural occupations, and which for some clergy might have been more central to their identity than was their religious vocation. That by-employments became part of a priest’s identity is evident from the reactions to dual careers such as Hall’s. It was common for priests to serve as schoolmasters or stewards in elite households: as one example, Sir Thomas Crooke, an ordained priest, was in Sir Alexander Culpepper’s employ as a steward.Footnote 98 There were even more specialized by-employments, such as garden design. In order to work for leading statesmen like Cecil and Hatton, Hall’s reputation and primary public identity must have been as a talented garden designer who possessed extensive knowledge of both the scientific (botanical) and practical aspects of garden art. Catholic gentry and nobility would have appreciated the fusion of religious and botanical knowledge Hall brought to his work, but his knowledge, reputation, and ability to design aesthetically pleasing spaces infused with displays of wit, such as Hatton’s garden at Holdenby, would have been the most important aspect for elites in the waning years of the English Renaissance.

Identity and Hall’s A Priest’s Discourse on Gardening

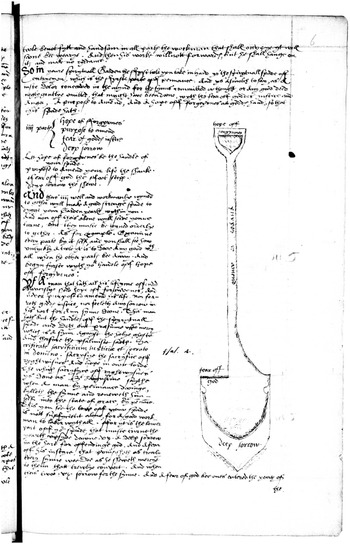

Hall’s writing reveals that he saw garden design and garden labour itself as another aspect of the spiritual expression of his ministry. His manuscript A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge contains 34 folios and eleven illustrations. The treatise contains both practical gardening advice and spiritual instruction, with the former often used as an analogy for the latter. The illustrations depict garden tools and designs and are annotated with the corresponding spiritual properties to which Hall focuses the reader’s attention. Whether tools to till and prepare the soil, a watering vessel, or garden beds, Hall ascribed devotional mnemonics to specific parts of those garden features and to the physical movements one had to perform to use the tools or meditate on the arrangement of plantings. The knowledge that produced the advice he offered in his Discourse was possible because of his education and dual vocations. Indeed, throughout this document Hall demonstrated that his identity as a gardener dovetailed with his identity as a priest. These were dual vocations that were callings from God, a stance that was typical of men in the professions.Footnote 99 Hall’s treatise argued that the care of one’s soil and the care of one’s soul were inseparable. Just as in practical terms a gardener would ‘rydd owt off the way all sotch impedymentes off breres [briars] and thornes, tyles and stones, logges and rubble or what so ever yt bee yt lyeth in the way to hinder his work’ they would in a spiritual sense ‘rydd owt off the way all sotch impedymentes [of] theis Dysposytyons’ of personality such as intractability or capriciousness. The spiritual gardener must then ‘clens your grownd off theim’ to eliminate sin and ‘bringe your grownd into tyllage, and to furnysh it wyth good Garden stuffe. you then buckell you wyth speed to ryddaunce which is Doone onlye by the sacrament off pennance’.Footnote 100

Since penance required both spiritual and corporeal work, the physical actions of gardening could, with proper focus, produce the spiritual change one sought as one performed physical labor in the garden in tandem with spiritual reflection. Hall detailed the spiritual functions of nine garden tools and how those tools could aid the spiritual gardener in religious practice. The first, the ‘spirytuall spade of Contrycyon which is the ffyrste parte off pennance’ was made up of four parts: hope of forgiveness, desire to change or ‘a purpose to amend’, fear of god’s justice, and deep sorrow. The handle of the spade represented hope of forgiveness, the shank symbolised ‘a purpose to amend’, the foot step on the top edge of the blade represented the fear of God, and the blade itself, deep sorrow (figure 1). The penitent, grasping the handle with hope and the shank with purpose to amend, would use their fear of God to push the spade into the earth, using the spade to turn over the soil. In practice in a garden, this action improves soil quality by mixing organic matter deeper into the earth, producing ‘fyne moolde’. Citing Psalm 4, Hall drew a parallel between the physical action of turning over the soil while focusing on these four aspects of the spade and the spiritual work of turning over the earth of one’s soul, an act of penance with which one ‘reneweth himself into the state of grace’ through the simultaneous physical and spiritual actions of gardening.Footnote 101 No single one of these parts would be enough to bring the change a sinner required. Rather, all elements had to be used together as parts of a whole, imagery in itself reminiscent of the apostle Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians and to the secular philosophy of the Body Politic.Footnote 102 One who used these components as a mnemonic as they dug in their garden could simultaneously ‘dygge your Garden yearth wythin you’, thus fulfilling both the practical and the spiritual aspects of gardening.Footnote 103

Figure 1. The spiritual spade of contrition. Hugh Hall, A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge. © British Library Board Royal Manuscript 18 C III, p. 280, f. 6r.

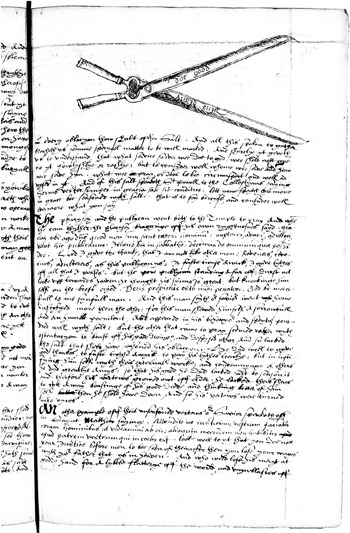

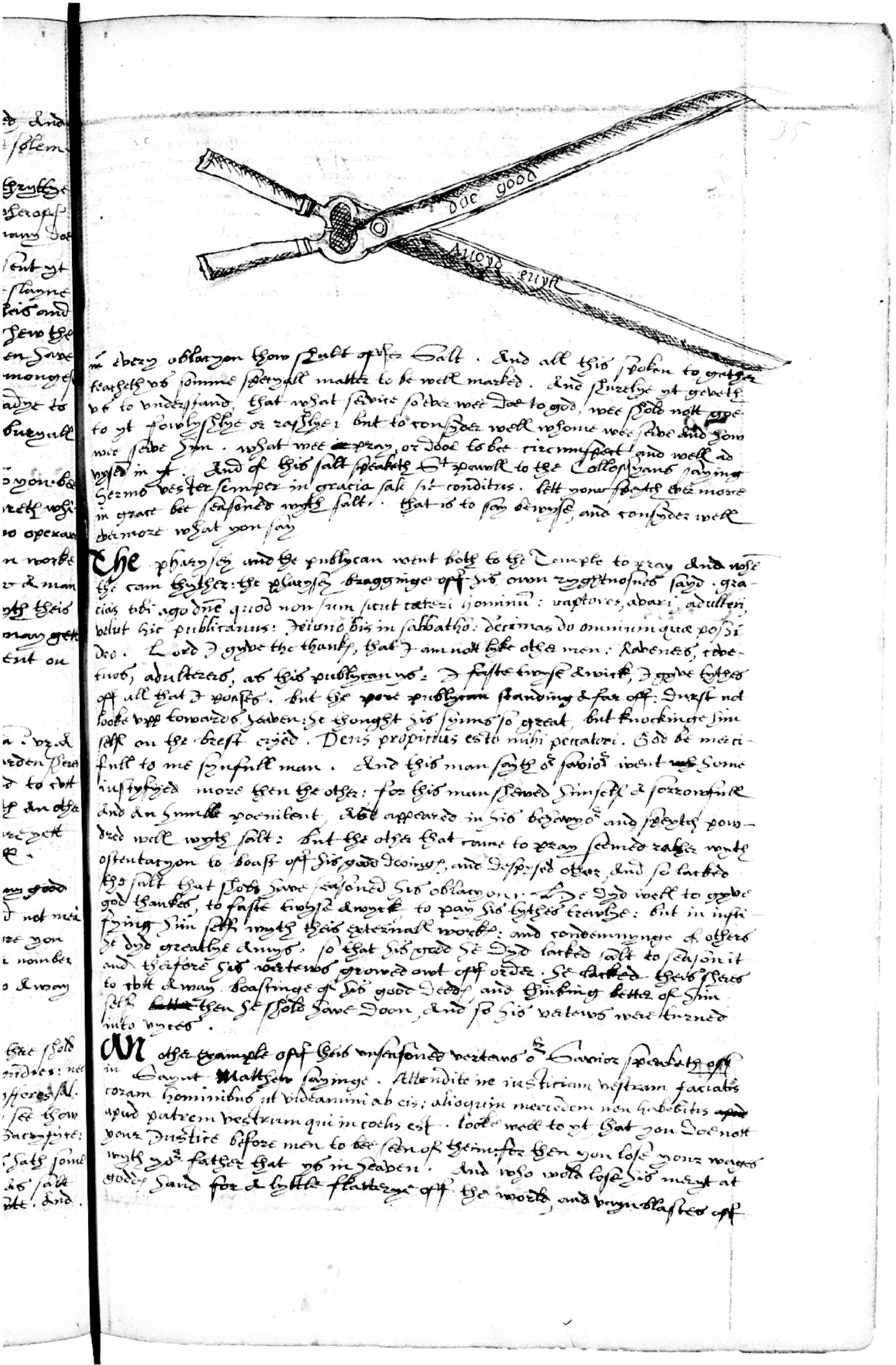

Similarly, Hall advised that one could use garden shears as a sensory mnemonic to rehearse an admonition to oneself to ‘do good, avoid evil’. Here, Hall cautioned that faithful believers must be vigilant not to allow themselves to be overcome by the perception of an abundance of their own virtues. Even ‘good vertues’ must ‘bee kept in good order’ if they were to benefit the soul and avoid falling into sin. When one’s virtues grew out of control, as healthy plants would grow beyond their borders, the penitent should then ‘take your shears and clypp away all that may offend’.Footnote 104 Here, Hall seemed to echo Boethius:

-

If you want a healthy yield,

-

Clear the bracken from the field.

-

If you want the grain to sprout,

-

Hack the briars and bushes out….

-

You will end your servitude

-

When your mind has understood

-

Real and apparent good.Footnote 105

Rather than citing Boethius, however, Hall engaged with Luke 18: 9-14, the parable of the ‘pharysey and the publycan’.Footnote 106 Hall also focused on St. Paul’s admonition to the Colossians, ‘lett youar speytch ever more in grace bee seasoned wyth salt that is to say bewyse and consyder well evermore what you say’.Footnote 107 Without salt to season one’s speech, ‘his vertewes growed owt off order. He lacked theis sheres to cutt away boastinge of his good Deedes…and so vertews were turned into vyces’.Footnote 108 To conclude the section, Hall returned to a blend of the philosophical/theological model and the practical: ‘Take your shears therfore and clypp off the evyll from good and then your workes wylbe the fearer’.Footnote 109 In other words, Hall encouraged believers to be vigilant in their gardening and spiritual practice, lest the plants in one’s garden or one’s virtues, or spiritual condition, grow out of control. As he had illustrated with the garden spade, Hall suggested that the gardener could transform the garden shears into a religious meditation. The two blades of the shears were labeled ‘doe good’ and ‘auoyd euill’ (figure 2). As the gardener repeatedly closed and opened the blades to trim grass, herbs, or other plants, they were to focus on the movement of the blades as a meditative chant, ‘do good, avoid evil’ with each swish of the blades.

Figure 2. The garden shears. Hugh Hall, A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge. © British Library Board Royal Manuscript 18 C III, p. 280, f. 35r.

Hall again fused practical and spiritual gardening when he compared planting advice for seeds in springtime to the cultivation of a penitent’s inner, spiritual garden. He began by acknowledging that ‘all good Gardeners’ know that springtime is ideal for setting plants and sowing seeds, since that is the time of year that ‘eytch thinge begynneth to take roote and sprowteth forthe by reason the sonne draweth the sapp and moysture towardes him, and cawseth eytch thinge to budd, sprynge and blossom’. Environmental conditions like temperate air, warm rains, and ‘the rygor off wynter’ past, allowed for the growth of seeds and plants just as spiritual conditions permitted people to turn to the ‘cheyf Gardeninge off our owen yearth’. Springtime planting was typical garden advice. Thomas Hill offered similar instruction in The Gardeners Labyrinth, acknowledging that warm air ‘comfortablie drawe vppe the plantes’. He added that in colder areas, ‘as at Yorke, and farther Northe,’ the gardener would have to wait until mid-Spring for the ground to be sufficiently warm for sowing seeds.Footnote 110 Gervase Markham echoed advice about ideal weather for planting and tied that knowledge to the expertise a good English housewife should possess in addition to her other attributes of godliness and modesty.Footnote 111

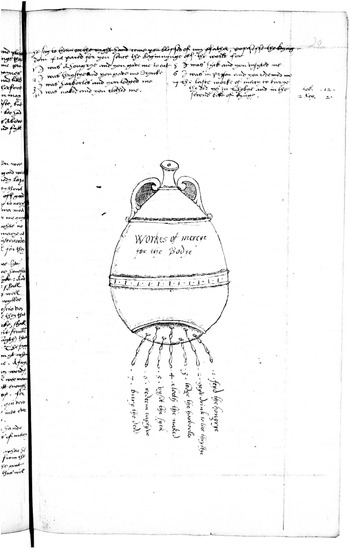

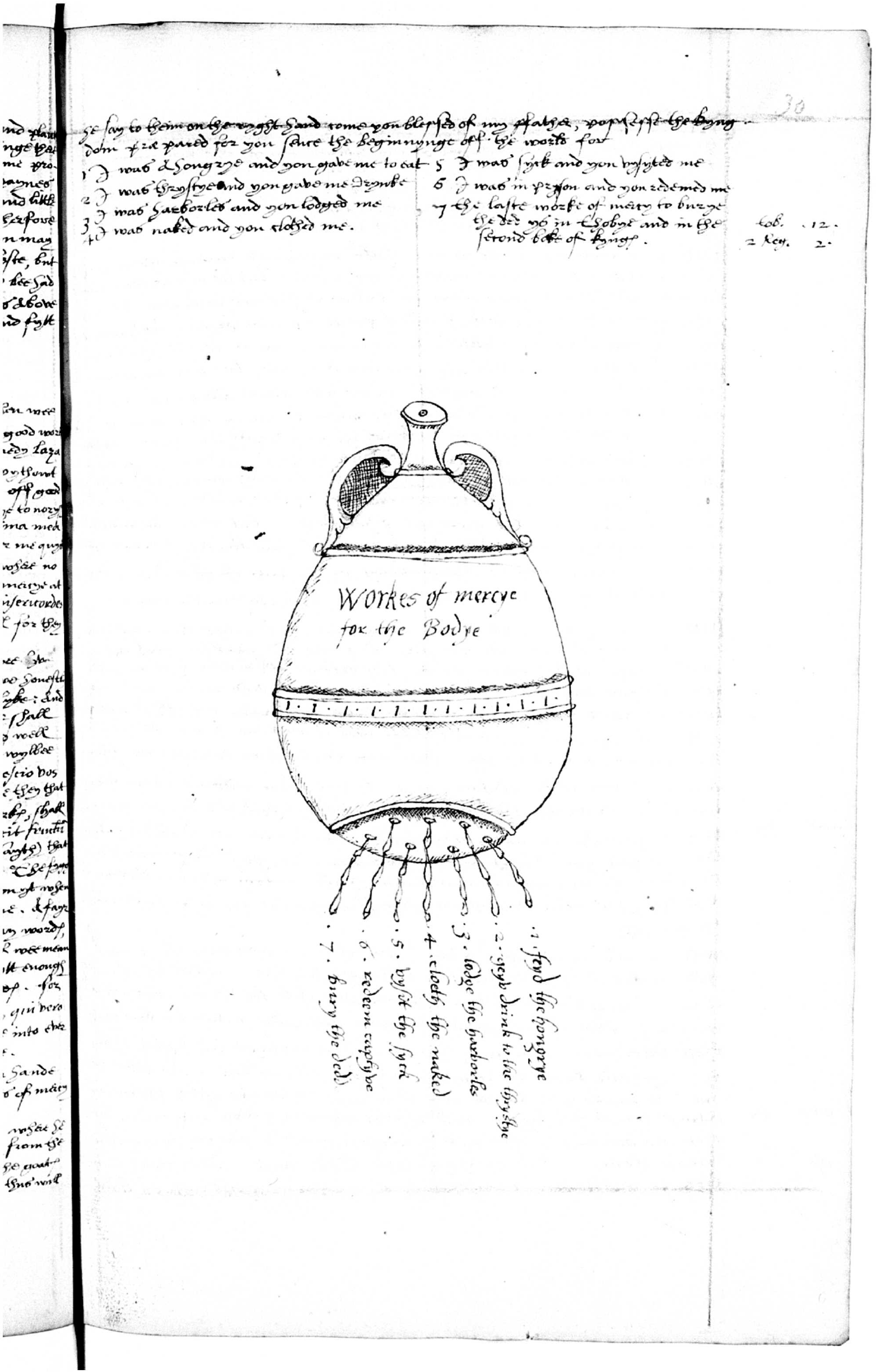

The pious meditations and rituals that Hall prescribed were part of the larger collection of religious expression and devotional practices of late sixteenth century Catholics. Readership is notoriously difficult to assess, especially when a text remained in manuscript, as Hall’s did. His primary audience for his Discourse was probably his patron, Lumley, since the manuscript was presented to Lumley and remained in his library. Hall might have intended an additional audience among the other gentry and noble gardeners for whom he worked and among whom he ministered, the literate men and women who populated the upper strata of the English social hierarchy. Jill Francis has noted that most important seventeenth century gardening texts circulated in manuscript rather than print form, specifically those written by Sir Thomas Hanmer and John Evelyn.Footnote 112 For Hall’s manuscript, however, manuscript circulation seems unlikely, since the one extant copy suggests that the manuscript was not copied and distributed. Hall’s advice might also have resonated with some of the labourers who worked in the gardens, since workers who could not read the text could be taught the devotional precepts connected with the tools and the bodily motions, as a sort of physical manifestation of catechism.Footnote 113 As a solitary interior practice, piety could be carried out anywhere, even while performing the most mundane tasks. The devotional practices Hall recommended in his Discourse were exercises and rituals that constituted both meditations or prayers and a form of good works. These qualities were evident not only in how a gardener would use a spade or shears, but also in the devotional qualities in watering pots. Hall included two of these in his Discourse, one representing works of bodily mercy and the other representing works of spiritual mercy (figures 3 and 4).Footnote 114 There was a durable connection between religious meditations or the practice of piety and labor. As Patricia Crawford has argued, after the Reformation, both Catholics and Protestants attested to the value of prayer in reducing the drudgery of everyday tasks.Footnote 115 Similarly, J.C.H. Aveling found that Catholics engaged in regular repetition of certain prayers, devotions, and rituals, for both piety and comfort.Footnote 116 Alongside demonstrations of piety, private devotions inculcated ‘introspective skills and a personal spiritual life’ which underscored a person’s religious identity, their credit, and their honesty.Footnote 117 Hall’s instructions make clear that similar combinations of bodily movement and repetition of prayer or devotions were easily transported into the garden.

Figure 3. Watering pot representing the works of bodily mercy. Hugh Hall, A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge. © British Library Board Royal Manuscript 18 C III, p. 280, f. 30r.

Figure 4. Watering pot representing the works of spiritual mercy. Hugh Hall, A priestes discourse of gardeninge applied to a spirituall understandinge. © British Library Board Royal Manuscript 18 C III, p. 280, f. 32r.

Hall’s understanding of horticulture adds additional evidence that from early in his working life gardening was a vocation and a significant aspect of his identity. He had extensive knowledge of continental advice on planting. Cecil’s steward Peter Kemp, who oversaw the making of the gardens at Burghley House in 1561, wrote to his master to report that ‘the priest’ refused to ‘open the grouwnd in dyvers places of the orchard, for yt he sayeth the holes wyll stand full of water do what he can’.Footnote 118 This knowledge is drawn directly from contemporary books on botany, gardening, and silviculture, which recommended extensive soil preparation prior to planting by repeatedly digging the earth at intervals of a month or more and then letting the holes sit open to the air to allow clods to loosen and weeds to die.Footnote 119 When these directions were not followed, the soil required significant amendment with dung before it was ready for planting.

Hall’s botanical and gardening knowledge reflected the work of natural philosophers like William Turner, Rembert Dodoens, and Thomas Hill and of ancient philosophers such as Pliny. Hall’s Discourse revealed his familiarity with Thomas Hill’s The Gardener’s Labyrinth and Pliny’s Natural History, particularly the sections on assessing qualities in soil and clearing the ground of debris. Hill outlined different types of soil — ‘hot and bare, not leane by sand, lacking a mixture of perfect earth: nor barren gravel, not of the glistering powder or dust of a leane stony ground, nor the earth continual moist’ — and connected those to contemporary ideas of bodily humours, for instance hot and dry or cold and moist.Footnote 120 These soils would require amendments if they were to successfully grow herbs, or ‘simples’ and flowers. Hall echoed Hill’s advice but took it further. Hot earth, made up of ‘Sulphurye or lymye substance’ would burn the seeds sown in it; cold and moist earth ‘wantynge heat’ would ‘eytch thinge decayeth that ys sett or sowed in yt’. Both men agreed that sandy or chalky soil with no ‘fatt matter to stay and hold yt together’ and clay soil ‘overbindeth’ and ‘hardened and congealed together into sturdye cloddes’ would be similarly barren.Footnote 121

Hall’s ability to unite religious and scientific texts speaks to a high degree of mastery of the materials and a life spent reading about his two vocations. His Discourse was a gardening text through which he dispensed gardening advice similar to Hill’s, Turner’s, and Dodoens’s, but it extended that genre into a devotional guide. In the margins of his Discourse, Hall notes where he has drawn on specific authors or texts. Most of his citations are from the New Testament of the Christian Bible; some denote ancient and medieval authors like St. Augustine, St. Bernard, and Isidor of Seville — texts to which he would have had ready access at Nonsuch.Footnote 122 Intriguingly, he cited none of the abundant botanical or gardening literature from the continent or England.Footnote 123 His citations were focused on philosophical and religious writings, which emphasized the importance of the devotional quality of the Discourse. Given the burgeoning practice of life-writing among the middling sort during the late sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries, the Discourse might even have reflected Hall’s own self-examination following his role in the Arden-Somerville affair. Indeed, life-writing became central to the identities and ‘sense of self’ of members of the middling sort during this period, and it is possible that Hall was part of this trend.Footnote 124 Among the case studies of early modern workers, Hall’s story provides additional evidence that an individual’s identity was complex, flexible, and tied to the life-cycle, and that their occupational identity both shaped and was shaped by contemporary ideas about gender.

In addition to his work as priest, gardener, and surveyor of works, Hall made at least one trip to the continent to buy plants, trees, and books for customers in England. John Gilpin, a servant of the eighth Earl of Northumberland, reported that when he met Hall at Rouen in 1580 or 1581 the priest had trees, plants, reams of paper, and seditious books prepared for transport into England.Footnote 125 Hall was evidently on a buying trip for one or more of his employers. Given the timing between his known residency and employment with the Ardens and Hatton and the volume of goods he had in his possession, he was probably buying for them as well as other Midlands gardeners. Hall’s excursion underscores his expertise and his credit, since patrons usually sent their most knowledgeable and trustworthy servants on these types of purchasing trips. Henry VIII sent his head gardener, Sir John de Leu, to France ‘for certain trees and grafts’ in 1547.Footnote 126 The botanist John Gerard’s surgeon friend Mr. William Martin sent one of his servants to the Barbary Coast to fetch plants for Gerard’s garden.Footnote 127 Naturalists in the Lime Street community of scientists in late sixteenth century London kept up a thriving trade with friends and colleagues throughout Europe and Asia.Footnote 128 These were not the professional plants merchants of the eighteenth century, but the work they performed in gathering specimens for the gardens of gentry and nobility established the foundations of the later plants trade and emphasised the increasing importance of botany and gardens in late Renaissance England.Footnote 129

Conclusions

Although the sources for Hugh Hall’s life are limited, extant archival records allow for a somewhat complete picture of the man and his life to emerge. Hall was both a priest and a gardener, an educated humanist whose training and expertise allowed him to occupy two vocations. He was in demand for pastoral duties, which he claimed to perform only rarely, and in even more demand as a gardener for Catholics and also for some Protestants, although he seems to have worked mainly for Catholic families in an interconnected Midlands social and kinship network. Within that network, Hall was among friends. The people for whom he worked were friends with each other; they socialized, as Cornwallis did with the Sheldons at Beoley, they married their children to each other, they witnessed and served as executors for one another’s wills, and they left gifts to each other in those wills. Most, if not all of them, cultivated gardens and must have valued the creativity and expertise Hall brought to their planted spaces. Over time Hall became one of their social group, paying visits to the Sheldons at Beoley and to the Ardens at Park Hall, for example, while he was working for Hatton at Holdenby.

Hall’s two vocations shaped his identity, both in the way others perceived him and how he viewed himself, or what scholars of social identity call external and internal identities. Among gentry and nobility with interests in gardens, Hall was known as a Catholic priest who ‘excelled in gardening worke’.Footnote 130 For these people, his identities reflected his dual vocations. His clerical identity strengthened his reputation among recusant Catholics while at the same time it placed him at risk among Protestants who believed he might have ill intentions toward the state or monarch. Still, both Protestants and Catholics sought him for his gardening talent, which indicates that his reputation as an expert gardener overcame his religious nonconformity for Protestants who employed him. For their part, Catholics surely appreciated whatever spiritual care Hall might have offered while in their employ. Hall’s clerical identity, the arduous physical labor he performed as a gardener and as a surveyor of works, and his knowledge of botany and gardening, provided him not only with occupational identities, but also with the honour and reputation necessary for the successful performance of his manliness.

The assessment of Hall’s sense of self agrees with arguments made by historians studying occupational identity, that what people did influenced who they felt they were, and that in analysing identity we should pay attention to how people in the past defined themselves. Hall’s Discourse, the only document that allows us to hear his unmediated voice, tells us that he was a deeply spiritual writer and probably a deeply spiritual man, whose twin occupations of gardener and Catholic priest merged into an identity as a spiritual gardener. Both of his vocations were founded in learned professional training, which he probably perceived as given to him by God. He deftly blended his vocations as two parts of a whole, the secular and the divine reflecting each other and inflecting each other. The earth, like a human soul, had problems with imbalance that required amendment to remedy. In humans, this was connected to sin; Hall made no such judgment on what caused problems in the soil. For Hall, the fusion of gardens and religion were what made a person whole, making the secular spiritual and placing the practitioner on a path for a humble and virtuous life filled with the beauty and the art of the late Renaissance English garden.