Focusing on beliefs that everyone would agree are delusional, as was done in Chapter 1, can tell us quite a lot about their defining characteristics and perhaps even say something about their underlying nature. However this approach is silent on another question, of whether there are other forms of pathological belief, and if so how these might be related to delusions. Also left unanswered is the question of the status of unusual beliefs that are seen in the non-mentally ill population, and whether or not these are related to delusions. The first of these issues turns out to be non-trivial and is the subject of this chapter. Discussion of the second, that of minority and idiosyncratic beliefs in the non-psychotic population, is postponed to Chapter 4.

The outstanding, even notorious, example of a belief that is pathological but not considered to be delusional is the overvalued idea. This clinical construct has been in existence for over a century, during which time it has been a constant thorn in the side of those who prefer their definitions of delusions to be simple. Although it often seems to lead a shady existence on the fringes of psychiatry, the need for such a category of abnormal belief has been argued for several times over the years, not least by Jaspers (Reference Jaspers1959). Rather more frequently, however, the reaction has been one of bland denial that there is any case to answer.

Another class of belief that falls squarely into the category of pathological but only uncomfortably regarded as delusional are the ideas of hopelessness, self-depreciation and self-blame that are seen in major depression. Clearly, depressed patients who are convinced that they are never going to get better despite having recovered from numerous previous similar episodes, and believe they are a burden on their families who would be better off without them, are labouring under some form of false belief. However, most people would be reluctant to place such ideas in the same category as those of Kraepelin’s patient in the previous chapter who wrongly believed that her husband was dead and that it was her fault. Exactly the same issues arise in mania, where patients with milder forms of the illness show boundless confidence and have inflated ideas about their abilities and future prospects. Despite the fact that clinicians encounter these ideas on a regular basis, they have been subject to very little scrutiny and they never seem to have acquired a universally accepted formal psychopathological name. In this chapter they are referred to rather clumsily as the unfounded ideas of major affective disorder.

The third form of non-delusional abnormal belief that needs to be considered seems at first sight surprising, since it concerns obsessions. Medical students the world over are taught that, although patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder find themselves forced to think unpleasant and distressing thoughts, they recognize that the ideas are not true. Later, those medical students who go on to become psychiatrists learn that some patients are distinctly ambivalent in their attitude to their obsessions, and there are even some who deny altogether that their ideas are irrational. How patients who show this phenomenon should be regarded might be thought to be a matter of only academic interest. However, it has recently acquired some importance, as psychiatry has found itself wrestling with the problem of how to classify not only patients who do not doubt their obsessions, but also those with certain other non-psychotic disorders where the ideas sometimes seem to be held with full delusional intensity (above all body dysmorphic disorder, see Chapter 3).

Overvalued Ideas

In the early 1980s the author of this book decided to carry out a PSE, which he had just learnt how to do, on a patient with morbid jealousy, a man who was convinced his wife was being unfaithful. He was confident that the detailed questioning of the interview would reveal not only a central delusion of infidelity but also a supporting network of delusions of reference and misinterpretation. After all, this was what such patients were supposed to show according to the literature on what was then variously referred to as paranoia, paranoid state and paranoid psychosis, which included a jealous subtype. To this author’s surprise, while the patient was completely convinced that his wife was having extramarital sex indiscriminately, he denied all other symptoms. He did not believe that people were talking about his wife’s infidelity, or that there were references to it on the TV, or that her lovers were leaving secret messages for her, or anything of the kind. He did think he could detect signs of his wife’s sexual activity from the state of her underwear, which he checked constantly, but this seemed to be understandable as the kind of wrong conclusion that anyone who was deliberately searching for scraps of confirmatory evidence might easily come to.

This was the author’s introduction to the murky world of the overvalued idea, the tradition that there exists a form of abnormal belief with qualities that set it apart from delusions, even if it is difficult to say exactly why. The term had been introduced by Wernicke at the beginning of the twentieth century (Wernicke, Reference Wernicke1906), who defined it as a solitary abnormal belief that came to dominate an individual’s actions to a morbid degree. Unlike obsessions, overvalued ideas were viewed as normal by the patient; ‘[i]ndeed patients see in them expressions of their very being’. Their development could often be traced to an event that aroused strong emotions of a negative kind, for example being left out of a will, the suicide of a friend, the death of one’s husband, a wife’s comment about sniffing tobacco, witnessing a person being deloused and perhaps most characteristically receiving an official judgement that was perceived to be unfair. Although the ideas often developed in individuals without any other signs of psychopathology, they could also be the first sign of psychosis or a symptom of melancholia or general paralysis (i.e. neurosyphilis).

The first case Wernicke described was of a 61-year-old man who came to psychiatric attention when he had an altercation with two men outside his flat. The police were called and the upshot was that he was forcibly removed to a mental hospital. No psychotic symptoms were found and he was quickly discharged. However, similar incidents continued to occur, leading to more admissions. It emerged that the patient believed that one of the two men involved in the original dispute, who he was acquainted with, had said to the other something along the lines of ‘Look, there is the scoundrel who abandoned the girl that time.’ The patient took this to be a reference to the fact that he had previously proposed to the daughter of a wine trader, but then broke off the engagement when he found out that her father was in financial difficulties. He considered that the escalating harassment he was experiencing all went back to this acquaintance, who had told other people the story and had also instigated the police to observe him on the grounds of alleged mental illness. The patient ended up hospitalized continuously for four years; he showed no referential ideas or other signs of mental illness during his stay, but he did not want to leave because he was convinced the harassment would start up again.

Wernicke’s second case was different, and foreshadowed some of the problems that would dog the overvalued idea in years to come. It concerned an unmarried female schoolteacher of around 40 who started to believe that a male colleague was in love with her. This caused her such difficulties that she ultimately had to leave her job. Unlike the previous patient, referentiality was a prominent part of the clinical picture, and this may well have gone beyond what could be construed just as simple ideas of reference. She repeatedly found herself in apparently coincidental meetings with the male colleague, and noticed that other members of staff talked conspicuously about him; even her pupils seemed to be dropping hints about the matter. A decisive feature for Wernicke was the fact that, despite having been declared incurably insane at one point, she eventually improved dramatically and returned to work in another job. Nevertheless, she remained permanently estranged from her family, who she believed deserved some of the blame for her losing the love of her life.

Despite being contemporaries of Wernicke, Kraepelin and Bleuler had very little to say about overvalued ideas. Kraepelin seems not to have used the term, and Bleuler (Reference Bleuler1924) expressed doubt about whether the symptom existed. Even so, both authors found themselves grappling with the problem of patients who showed similar features to Wernicke’s first case. Kraepelin (Reference Kraepelin1905) gave a detailed description of one such patient (see Box 2.1), and argued that the presentation was simply a ‘secondary form’ of paranoia. Later, however, he (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1913b) changed his mind and excluded it from this category, citing among other things the fact that the belief seemed to have its basis in external events rather than arising from than internal causes.

Box 2.1 The Querulous Paranoid State (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1905)

A master tailor, who had previously been declared bankrupt, again fell into debt and, in the course of trying to prevent a creditor and a bailiff removing his furniture, locked both of them up in his house while he lodged a complaint in court. As a consequence of this he was found guilty of false imprisonment.

A short, humorously treated account of the affair appeared in a newspaper, which contained inaccuracies. The patient wrote a correction, only part of which was printed. A further enraged letter to the editor was responded to by publication of a full report of the proceedings, in which the words ‘master tailor’ were printed in large type. The patient took exception to this and brought three legal actions against the newspaper. These actions were all rejected in the courts. The patient then set in motion a series of appeals to higher and higher courts, eventually petitioning the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of State, the Grand Duke and the Emperor. After all these measures failed he tried the experiment of complaining to the heads of the courts and appealing to the public, and was considering proposing disciplinary proceedings against the Public Prosecutor.

The all-consuming nature of the patient’s preoccupation was well-illustrated in the following passage:

The innumerable petitions which the patient has drawn up in the course of the last few years, chiefly at night, are exceedingly long-winded, and always allege the same thing in a rather disconnected manner. In their form and mode of expression they incline to the legal document, beginning with ‘Concerning’, going on throughout with ‘evidence’ and concluding with ‘grounds’. They abound in half or wholly misunderstood professional expressions and paragraphs of totally different laws. Often they are careless and appear to have been written under excitement, contain numerous notes of exclamation and interrogation, even in the middle of a sentence; one or more underlinings, some in red or blue pencil; marginal notes and addenda, so that every available space is made use of. Many of the petitions are written on the backs of judgements and refusals of other courts.

On mental state examination, the patient was coherent and was able to give a clear account of events. On the subject of his court actions he expressed himself volubly and showed increased self-confidence and superiority, plus a certain satisfaction and readiness for battle. He was also exceedingly touchy – if pressed on whether he might have been mistaken in his interpretation of events, he immediately became mistrustful and raised the suspicion that the interviewer supported his opponents. He was never at a loss for an answer to objections, which he justified by quoting minutiae of the law; in prolonged conversation a wearisome diffuseness crept into his narrative. It seemed that an attorney involved in the patient’s original bankruptcy proceedings was the original source of his problems. Because of this, the clerk did not draw up the accusation properly; the public prosecutor gained an erroneous impression from it; and the judges of several courts did not want to reverse verdicts once agreed to; and as a body they were prejudiced. He believed that the whole system of law had been obstructed via a conspiracy involving Freemasons and also Jewish financiers, who supported the newspaper that wrote about him. Additionally, the press was involved, as they were associated with the attorney in question.

As a result of his incessant pestering of the authorities, the patient was eventually pronounced to be mentally deranged, against which he adopted every possible legal means of redress. Meanwhile he continued to carry on his business, and apart from writing innumerable petitions, did not appear strange or troublesome. He had brought his family almost to the brink of ruin, but in spite of all the setbacks he remained optimistic about the outcome of his case.

Bleuler (Reference Bleuler1911) expressed his views rather more succinctly:

We find numerous transitions from simply unbearable people to the paranoid litigants with marked delusions. The best solution perhaps is to draw a line somewhere in the middle of the scale and place the half that do not have real delusions there and count the others as paranoid.

In contrast to Kraepelin and Bleuler, Jaspers (Reference Jaspers1959) wholeheartedly embraced the concept of the overvalued idea. For him it was one of the most important categories of delusion-like ideas, beliefs that needed to be distinguished from delusions proper (others included the delusions of mania and depression and what he called transient deceptions due to false perception). Unlike delusions, which were the manifestations of a new process irrupting into the individual’s life, an overvalued idea was, he argued, the result of an interaction between the individual and his experience which brought a focus to the patient’s life, albeit a pathological one – it was as it were a ‘hypertrophy’ of an already abnormal personality in reaction to adverse events.

Psychopathologically, rather than being un-understandable, the overvalued idea was fundamentally no different to the kinds of passionate political, religious or ethical conviction held by many healthy people. As well as the by now paradigmatic querulous paranoid state, Jaspers (1959) considered that a proportion of patients with morbid jealousy also showed overvalued ideas, as well as some cranky inventors and world reformers.

Jaspers’ views on understandability versus un-understandability and process versus personality development enjoyed great influence in mid-twentieth century British and European psychiatry, but started to fall out of fashion from the 1970s. Over roughly the same period, the overvalued idea made the transition into a much looser usage, as a term which referred to false beliefs that the clinician did not feel were held with the degree of full conviction necessary for delusions – in other words as a synonym for partial delusions (see Chapter 1). This position became official in 1980 when DSM-III defined an overvalued idea as ‘an unreasonable and sustained belief that is maintained with less than delusional intensity (i.e. the person is able to acknowledge the possibility that the belief may or may not be true)’.

The overvalued idea was not to prove quite so easy to dispose of, however. The problem was the existence of certain disorders which were characterised by a range of presentations that were difficult to fully characterize without resorting to something resembling the concept. One of these was morbid jealousy, which encompassed everything from merely over-possessive individuals to patients who held a delusion of infidelity in the context of an obviously psychotic illness with other delusions, hallucinations, etc. In between were patients – like the one described earlier in this chapter – who showed a preoccupying belief that their partner was being unfaithful in the apparent absence of other symptoms, variously referred to in the literature as jealous monomania, obsessive jealousy or the jealousy reaction of abnormal persons (Cobb, Reference Cobb1979). Another example was hypochondriasis: Merskey (Reference Merskey1979) commented that between the excessive health consciousness that characterized many otherwise psychiatrically healthy individuals and the delusions of illness and bodily malfunction seen in major depression and schizophrenia, from time to time one encountered patients for whom pure hypochondriasis seemed the only applicable term:

These patients show excessive concern with bodily function, a failure to respond to sympathetic management and reassurance by relinquishing their complaint, a marked fear of the occurrence of physical disease and a continuing or markedly recurring belief that they have got a disease. They show dependence on medical personnel and often are dissatisfied with them. A pattern of cultivated meticulous valetudinarianism may be prominent together with detailed ordering of the smallest items of daily life in terms of health and illness with cupboards overflowing with laxatives and home remedies, punctilious compliance with dietary fads, etc.

Eventually, the present author (McKenna, Reference McKenna1984), prompted by his own experience with the aforesaid patient with morbid jealousy (who ultimately murdered his wife), and having also seen a case of querulous paranoia, not to mention several with hypochondriasis, made the connection with the tradition of the overvalued idea and wrote a review article on the topic. This made the point that all three disorders could sometimes occur in an isolated form, without other symptoms suggestive of schizophrenia or major depression being present. The phenomenology of the belief, it was suggested (only partly tongue-in-cheek), was characterized by non-delusional conviction, non-obsessional preoccupation and non-phobic fear. A further notable feature was the determined and consistent way in which the patients acted on their beliefs.

The article also made a case that the central feature of some other disorders was an overvalued idea. The classic example here was anorexia nervosa where, despite the fact that patients adamantly believe they are overweight – to the extent that they not infrequently starve themselves to death – use of the term delusion was (and still is) studiously avoided. Something else that seemed like it might fit into the same category was dysmorphophobia, or as it is now known, body dysmorphic disorder. The nosological status of this disorder was very unclear at the time, as witnessed by articles with titles like ‘Dysmorphophobia: symptom or disease’ (Andreasen & Bardach, Reference Andreasen and Bardach1977). Since then interest has increased exponentially, and the question of whether these patients are deluded or not deluded is currently the subject of an important debate (see Chapter 3).

A third suggested candidate for a disorder with an overvalued idea was erotomania. Although Wernicke’s (1900) second patient had this diagnosis, her case was less than convincing as she had widespread referential ideas that may well have been delusional in nature. However, de Clérambault (Reference Clérambault1942, see also Baruk, Reference Baruk, Hirsch and Shepherd1959), whose name has become synonymous with the disorder, also felt that erotomania showed features that set it apart from other delusional states. Rather than being a gradually discovered explanation for mysterious events, he argued, the belief in erotomania had a ‘passionate’ or ‘hypersthenic’ quality from the outset, which led the patient to relentlessly pursue the person they believed was in love with them. Unfortunately, de Clérambault’s five cases of ‘pure’ erotomania (as described in Signer, Reference Signer1991) were no more convincing than Wernicke’s: one believed that a whole series of military officers and King George V were secretly communicating their romantic interest in her and that all London knew about the affair. Another showed formal thought disorder, and a third additionally had persecutory delusions.

Nevertheless, there is some reason to believe that cases of erotomania where the central belief shows the hallmarks of an overvalued idea may also exist. Mullen et al. (Reference Mullen, Pathé and Purcell2000) described a form of the disorder which often emerged in an individual with pre-existing personality vulnerabilities such as self-consciousness, stubbornness and a tendency to take remarks the wrong way, and once established, became the organizing principle of the person’s life. Although they stated that the belief was often of delusional intensity, they also noted that on other matters the individual remained as clear thinking, orderly and rational as before they became ill. The central belief did not even have to be a conviction that a person was in love with the patient; patients with what they termed pathologically infatuations (also known as borderline erotomania) persistently pursued the object of their affections but made no strong claims that their love was reciprocated. One of Mullen et al.’s cases of this type is reproduced in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2 Borderline Erotomania or Pathological Infatuation (Mullen et al., Reference Mullen, Pathé and Purcell2000)

Ms L, a female aged 47, was the youngest of four children. On leaving school she obtained a job as an accounts clerk, which she had retained until a year previously. Her husband was her first and only boyfriend. Ms L was always painfully shy and self-conscious. She reported frequently feeling that people looked at her and laughed at her behind her back. At work she was occasionally overwhelmed by suspicions that others were ganging up on her and talking about her. She avoided social contacts outside the family. She was a well-organized individual but had no obsessional or phobic symptoms.

Four years previously she had come to ‘realize’ that a senior partner in the firm for which she worked entertained romantic feelings about her. She had always admired him and considered him a gentle and concerned individual. Her preoccupations with this man increased markedly after the sudden death of a younger brother who had been the person with whom she had had the closest relationship. The love crystallized following an incident when the object of her affections spoke to her one morning about the weather and the prospects for the upcoming ski season. It was this she claimed made her realize that he reciprocated her affection. She said ‘l knew this meant he had strong feelings for me, because usually I am completely ignored. No one chats to me. They think I’m not intelligent enough’.

Over the next few months she felt that he expressed his love in a variety of roundabout ways: clothes that he wore, the way he nodded a greeting, and the occasional exchanged good morning. It was not, she said, so much what he said but the tone of voice and the way he said it. She became interested in her appearance for the first time in many years, took up aerobics, lost 10 kg and began colouring her hair.

The object of her attentions, in a victim impact statement, said he had been aware for some years that she was infatuated with him, but this was entirely one sided and had never been encouraged. He had tried to ignore it but it became, in the last three years, increasingly intrusive. She would follow him; turn up unexpectedly; stand next to his car after work, awaiting his departure; write notes to him and phone him both at work and at home. He arranged for her to be made redundant to prevent continuing harassment at work.

Eight months prior to the admission, Ms L, while trailing the object of her affections, observed him to meet and have a drink with a senior secretary from the firm’s office. Over the next week she tailed both this lady and the object of her affections. She became convinced that he was having an affair with this woman. She found herself troubled by intrusive images of her would-be lover in the arms of this other woman. She became increasingly distressed and angry. She made a number of accusatory phone calls to the object of her affections, his wife and the secretary she supposed to have stolen his affections from her. At one point she attempted to throw herself in front of his car. She caused a major incident at his place of work by accusing him in front of a number of colleagues of having an affair and having deserted her. At this time she began to develop signs of depression with sleep disturbance, loss of appetite, self-denigratory ruminations and suicidal thoughts. Immediately prior to her admission she confronted the object of her affections with a rifle she had taken from her husband’s gun cupboard. He claims she pointed it at him and threatened him, although she denies actually directing the gun at him. She left to return home, where she attempted to stab herself through the heart and in fact succeeded in inflicting a serious chest wound.

On admission she acknowledged that she was still preoccupied by thoughts of her supposed lover. She believed that there would still be a reconciliation between them because he remained in love with her and she returned his affection. She acknowledged that she was still plagued by jealousy and that vivid images would intrude into her consciousness of him having intercourse with her supposed rival. She claimed no longer to be actively suicidal because she recognized that eventually this hiccup in their relationship would be sorted out and they would have a future together. She was commenced on both antidepressants and 6 mg of pimozide and over the subsequent four weeks, the intensity of her preoccupations with this supposed beloved gradually decreased. She came to recognize that the relationship was now over and there was no future, given what had occurred. She still retained the belief that he had returned her affections, although she accepted that she may have been overhopeful in her expectations for the relationship.

The stage was now set for a further expansion of the concept of the overvalued idea by Veale (Reference Veale2002). He argued that it had been a mistake all along to think of overvalued ideas in terms of concepts like degree of conviction and presence or absence of insight. Instead, he proposed that the overvalued idea occupied a different conceptual space altogether, that of Beck’s (Reference Beck and Beck1979) ‘personal domain’. An individual’s personal domain concerns what he or she values about him- or herself, the animate and inanimate objects that he or she has an emotional investment in, such as his family, friends and possessions. Overvalued ideas arose when one of these values became dominant and idealized within the personal domain. Conversely, if a particular value was not part of an individual’s personal domain, an overvalued idea could not develop: a person may believe that they are overweight or their nose is too big, but if they do not place much value on the importance of appearance, this will never convert into anorexia nervosa or body dysmorphic disorder.

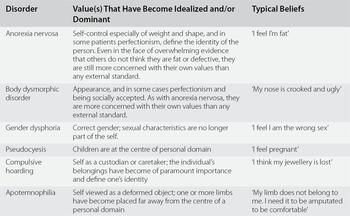

This conceptualization led Veale (2002) to propose that overvalued ideas are the common feature of a considerably wider range of disorders than previously thought. A partial list of the disorders he included is shown in Table 2.1; notable inclusions are gender dysphoria, compulsive hoarding and pseudocyesis. In gender dysphoria, he argued, the idealized value is being of the opposite gender, and in compulsive hoarding it is the individual’s possessions that assume overriding importance. Women with pseudocyesis believe themselves to be pregnant when they are not, reflecting the enormous emotional investment they have in having children. It is worth noting that there is little or no psychiatric understanding of any of these disorders, either from the standpoint of nosology or in terms of their putative psychopathological basis.

Table 2.1 Some Additional Disorders Where the Central Psychopathology Has Been Proposed to Be an Overvalued Idea

| Disorder | Value(s) That Have Become Idealized and/or Dominant | Typical Beliefs |

|---|---|---|

| Anorexia nervosa | Self-control especially of weight and shape, and in some patients perfectionism, define the identity of the person. Even in the face of overwhelming evidence that others do not think they are fat or defective, they are still more concerned with their own values than any external standard. | ‘I feel I’m fat’ |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | Appearance, and in some cases perfectionism and being socially accepted. As with anorexia nervosa, they are more concerned with their own values than any external standard. | ‘My nose is crooked and ugly’ |

| Gender dysphoria | Correct gender; sexual characteristics are no longer part of the self. | ‘I feel I am the wrong sex’ |

| Pseudocyesis | Children are at the centre of personal domain | ‘I feel pregnant’ |

| Compulsive hoarding | Self as a custodian or caretaker; the individual’s belongings have become of paramount importance and define one’s identity | ‘I think my jewellery is lost’ |

| Apotemnophilia | Self viewed as a deformed object; one or more limbs have become placed far away from the centre of a personal domain | ‘My limb does not belong to me. I need it to be amputated to be comfortable’ |

Note: Veale also included social phobia, making the argument that patients at the severe end of the spectrum of this disorder often hold beliefs with near delusional certainty about what others are thinking.

The last disorder listed in Table 2.1 has to be among the strangest in psychiatry. Apotemnophilia or body integrity identity disorder is a thankfully rare condition where an individual develops an overwhelming wish to have one or more limbs amputated. This leads him or her to try and persuade surgeons to operate to remove a limb, or in some cases self-amputation is attempted. The scanty available information (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Hennekam and Denys2012; First, Reference First2005; First & Fisher, Reference First and Fisher2012) suggests that the disorder usually has its onset in childhood or adolescence and that only a minority of patients have associated psychiatric disorders. Although not sexually motivated in the majority of cases, the disorder otherwise seems to share several key features with gender dysphoria, as First (Reference First2005) noted.

Something that Veale (2002) did not include but might represent yet another example of a disorder with an overvalued idea, at least in some cases, is the olfactory reference syndrome, currently classified as a subtype of delusional disorder (see Chapter 3). These patients become convinced that they give off an offensive smell which others notice, and they engage excessively in behaviours such as showering, changing their underwear and using perfumes and deodorants. Begum and McKenna (Reference Begum and McKenna2011) carried out a systematic review of cases reported in the world literature, excluding those which showed – or later developed – evidence of schizophrenia, major depression or bipolar disorder. They found that while some of the patients were described as holding the belief that they smelt with unwavering conviction, in slightly less than half there were statements such as, ‘admitted that his preoccupations about the odour were excessive and unreasonable’; ‘the thoughts were ego-dystonic’; ‘oscillated between fear and conviction’; and ‘could be persuaded to some extent that she did not smell’. They also found that only a minority of the patients were actually able to smell the smell they believed they were giving off, and even then often only intermittently. Referential thinking, in contrast, was very frequent – the patients described people around them frowning, making remarks, opening windows, getting off buses and trains when the patient got on, and so on. However, while these ideas were often pervasive and at times farfetched, they never seemed to take a clearly delusional form, such as the smell being referred to by means of special signs or being alluded to on television.

Unfounded Ideas in Major Affective Disorder

The description of this phenomenon goes back to well before the time of Kraepelin and Bleuler, but it seems only right to start with the former author, who, as well as identifying schizophrenia, was the first to properly define the category of major affective disorder. Describing ‘melancholia simplex’, that is depressive states without psychotic symptoms or stupor, he (Kraepelin, Reference Kraepelin1913b) noted how the patients viewed their past and future in a uniformly dim light: they felt that they were worthless and no longer of any use, their life appeared pointless to them, and they considered themselves superfluous in the world. In more severe forms of illness, the ideas would become first more and more remote from reality – patients would state that they had not taken good care of their children, had not paid their bills punctually, had been dishonest about their taxes – and then frankly delusional – that they had committed perjury, offended a highly placed person without knowing it, committed incest, set fire to their house, etc.

In much the same way, patients with hypomania, Kraepelin’s mildest form of mania, would say things like they were musically gifted, had written poetry, or were more intelligent than anyone else, often in a half-joking or boastful way. Once again these ideas would then give way by degrees to frank delusions in more severe cases, such as of being a millionaire, having invented non-existent devices and so on.

Almost all of what has been written subsequently about these ideas has concerned depression, and the line taken has always been the same, that they shade inexorably into depressive delusions. A good example is the detailed account of 61 patients with melancholia carried out in 1934 by the British psychiatrist, Lewis (Reference Lewis1934) (his definition of melancholia corresponds closely to the modern concept of major depression). He found 27 who had prominent ideas of self-reproach and self-accusation. Their ideas ranged from simply expressing the view that they had been selfish, had let everyone down, had neglected their children or had betrayed a trust, to the most abject delusions, for example that they were the wickedest person in the world, or that they had plotted to bring about their husband’s death through consumption, or that by eating they were causing other people to starve.

Hypochondriacal ideas were also common, being seen in 25 of the patients. The ideas here often centred on the bowels and once again encompassed the kind of concerns expressed by many healthy people, through to more obviously pathological ideas that they could not digest their food, to in the most severe examples a complete denial of having any abdominal viscera.

Something that Lewis (1934) did not describe but which can also occur is a transition from unfounded ideas to delusions in the same patient. Most clinicians will have seen patients who initially present with vague complaints about their bowels, without any clear diagnosis, but then over a period of days or weeks go on to develop a picture of psychotic major depression with the earlier ideas transforming into full-blown hypochondriacal delusions.

The only other systematic investigation into the phenomenon of non-delusional depressive ideas that appears to exist is Beck’s (Reference Beck1967) description of what he called cognitive distortions. As with Lewis, his case material consisted of patients he was treating, most or all of whom would have met current criteria for major depression or bipolar depression based on a long list of additional symptoms that they were required to show. His analysis was based on the patients’ spontaneous reports about their thoughts and feelings during therapy, and also the notes that many of the patients themselves made between sessions.

Beck (1967) found that a particular style of thinking recurred in his patients and showed itself in various ways, including low self-regard, ideas of deprivation (both emotional and material), self-criticism and self-blame, the perception of problems and duties as overwhelming, self-injunctions to do things, and escapist and suicidal wishes. His examples are reproduced in Box 2.3. He observed that such ‘depressive cognitions’ were often triggered in situations that touched on the patients’ preoccupations, even if only in a remote or trivial way. For example, if a passer-by did not smile at one patient, he would think he was inferior. Another patient had the thought she was a bad mother whenever she saw another woman with a child. However, the thoughts could also occur independently of the external situation, in the form of long, uninterrupted sequences of free associations.

Box 2.3 Beck on Depressive Cognitions (Reproduced with permission from Beck, Reference Beck1967)

Low Self-Regard

This generally consisted of an unrealistic downgrading of themselves in areas that were of particular importance to the patients. A brilliant academician questioned his basic intelligence, an attractive society woman insisted she had become repulsive-looking, and a successful businessman believed he had no real business acumen and was headed for bankruptcy. In making these self-appraisals, the depressed patient was prone to magnify any failure or defects and to minimize or ignore any favorable characteristics. A common feature of many of the self-evaluations was the unfavorable comparison with other people, particularly those in his own social or occupational group. Almost uniformly, in making his comparisons, the depressed patient rated himself as inferior. He regarded himself as less intelligent, less productive, less attractive, less financially secure, or less successful as a spouse or parent than those in his comparison group.

Ideas of Deprivation

These ideas were noted in the patient’s verbalized thoughts that he is alone, unwanted, and unlovable, often in the face of overt demonstrations of friendship and affection. The sense of deprivation was also applied to material possessions, despite obvious contrary evidence.

Self-Criticisms and Self-Blame

The self-criticisms, just as the low self-evaluations, were usually applied to those specific attributes or behaviors most highly valued by the individual. A depressed woman, for example, condemned herself for not having breakfast ready for her husband. She reported a sexual affair with one of his colleagues, however, without any evidence of regret, self-criticism, or guilt. Competence as a housewife was one of her expectations of herself but marital fidelity was not. The patients’ tendency to blame themselves for their mistakes or shortcomings generally had no logical basis. This was demonstrated by a housewife who took her children on a picnic. When a thunderstorm suddenly appeared, she blamed herself for not having picked a better day.

Overwhelming Problems and Duties

The patients consistently magnified problems or responsibilities that they considered minor or insignificant when not depressed. A depressed housewife, confronted with the necessity of sewing name tags on her children’s clothes in preparation for camp, perceived this as a gigantic undertaking that would take weeks to complete. When she finally got to work at it she finished in less than a day.

Self-commands and Injunctions

These cognitions consisted of constant nagging or prodding to do things. The prodding would persist even when it was impractical, undesirable, or impossible for the person to implement these self-instructions. The ‘shoulds’ and ‘musts’ were often applied to an enormous range of activities, many of which were mutually exclusive. A housewife reported that in a period of a few minutes, she had compelling thoughts to clean the house, to lose some weight, to visit a sick friend, to be a den mother, to get a full-time job, to plan the week’s menus, to return to college for a degree, to spend more time with her children, to take a memory course, to be more active in women’s organizations, and to start putting away her family’s winter clothes.

Escapist and Suicidal Wishes

Thoughts about escaping from the problems of life were frequent among all the patients. Some had daydreams of being a hobo, or of going to a tropical paradise. It was unusual, however, that evading the tasks brought any relief. Even when a temporary respite was taken on the advice of the psychiatrist, the patients were prone to blame themselves for shirking responsibilities. The desire to escape seemed to be related to the patients’ viewing themselves at an impasse. They not only saw themselves as incapable, incompetent, and helpless, but they also saw their tasks as ponderous and formidable. Their response was a wish to withdraw from the ‘unsolvable’ problems. Several patients spent considerable time in bed; some hiding under the covers. Suicidal preoccupations seemed similarly related to the patient’s conceptualization of his situation as untenable or hopeless. He believed he could not tolerate a continuation of his suffering, and he could see no solution to the problem: The psychiatrist could not help him, his symptoms could not be alleviated, and his problems could not be solved.

Beck (1967) also found that depressive cognitions showed certain formal characteristics. One of these was that they arose without any reflection or reasoning: for example, a patient observed that when he was in a situation where someone else was receiving praise he would automatically have the thought, ‘I’m nobody ... I’m not good enough’. Later he would reflect on this and realize it was an inappropriate reaction. The thoughts also had an involuntary quality; they would keep occurring even if the patients resolved to stop having them or tried to ward them off. Additionally, they seemed plausible to the patients, who tended to accept them uncritically and often with a strong emotional reaction; it required considerable experience with having the thoughts to be able to see them as distortions. Finally, Beck noted a characteristic stereotyped or perseverative quality: the same type of cognition would be evoked in a wide range of different settings. Some of his patients were even able to anticipate the kinds of depressive thoughts that would occur in certain specific situations and would prepare themselves in advance to make a more realistic judgement of them.

There is a certain amount of re-invention of the wheel in Beck’s descriptions, but at the same time there is no doubt that his account has more phenomenological depth than just about anything else that has been written. In particular, he identified depressive unfounded ideas as emerging spontaneously and effortlessly and carrying with them an immediate feeling of being true. In other words they appear to be unmediated, in the same way that Jaspers argued delusions are (see Chapter 1). Unlike delusions, however, patients are able to some extent to distance themselves from the ideas, being able to remonstrate with themselves about them, avoiding situations that provoke them, and most importantly for Beck, being able to be brought round to seeing them as distortions by a therapist.

Depressive cognitions formed the foundation of Beck’s development of cognitive therapy, which was to make him as close to world famous as it is possible to get in psychiatry. As he did so, he repeatedly took the position that the ideas were not just present during depressive episodes but represented an enduring aspect of the psychological make-up of individuals are who were prone to develop the disorder (e.g. Beck, Reference Beck1967, Reference Beck2008; Kovacs & Beck, Reference Kovacs and Beck1978). Here, however, he seems to be wrong: Coyne (Reference Coyne, Freeman, Simon, Beutler and Arkowitz1989) reviewed the evidence from 10 studies of depressive cognitions in patients who had recovered from a depressive episode. All but one found that the cognitions had returned to levels similar or close to those of controls. The only exception was a study that used less stringent criteria for remission than the other studies. Coyne (Reference Coyne, Freeman, Simon, Beutler and Arkowitz1989) concluded that ‘studies that have attempted to identify a persistent traitlike quality to depressive cognitions have generated considerable evidence to the contrary’.

Obsessions That Are Not Doubted

Views on obsessions have been remarkably consistent over a long period of time. Current definitions, such as those in DSM-5, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) and any number of textbooks of psychiatry, identify them as ideas, thoughts, impulses or images which are recurrent and intrusive, and which the individual considers senseless and tries to ignore or suppress. This definition can be traced back to Schneider (Reference Schneider1930) who described obsessions as ‘contents of consciousness which, when they occur, are accompanied by the experience of subjective compulsion, and which cannot be got rid of, though on quiet reflection they are recognized as senseless’; and then further to Esquirol in the nineteenth century who considered them to be ideas, images, feelings or movements accompanied by a sense of compulsion and a desire to resist them, with the individual recognizing them as foreign to his personality.

In the way of textbook definitions, however, the idea that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder do not believe that their obsessions are really true is an oversimplification. This was first pointed out by Lewis (the same Lewis who carried out the aforesaid study of melancholia) in what remains one of the most eloquent and insightful analyses of the phenomenology of obsessions. For him (Lewis, Reference Lewis1957), the important feature was the patient’s struggle against the thought:

The indispensable subjective component of an obsession lies in the consciousness of the patient: to him it is an act of will, which he cannot help making, to try and suppress or destroy the unwelcome intruder upon his mental integrity; but the effort is always in vain. It does not matter whether the intruder is a thought, an idea, or an image, or an impulse, accompanied by appropriate affect. Along with this subjective feeling of compulsion goes an inability to accept the experience as part of one’s proper and integrated mental activity: it is a foreign body, not implanted from without (as a disordered schizophrenic experience might be held to be by the patient) but arising from within, homemade but disowned, a sort of mental sequestrum, a calculus that keeps on causing trouble.

In contrast, he (Lewis, Reference Lewis1936) considered recognition of the senselessness of the idea to be non-essential:

Critical appraisal of the obsession, and recognition that it is absurd represents a defensive, intellectual effort, intended to destroy it: it is not always present, nor is the obsessional idea always absurd.

Here, Lewis was ahead of his time: starting approximately 50 years later there has been a steady stream of publications reporting that some patients with otherwise typical obsessive-compulsive disorder do not consider their obsessions to be unreasonable. This phenomenon is most commonly referred to as lack of insight into obsessions, but also as development of overvalued ideation (Kozak & Foa, Reference Kozak and Foa1994), or as obsessive-compulsive disorder with psychotic features (Solyom et al., Reference Solyom, DiNicola, Phil, Sookman and Luchins1985; Insel & Akiskal, Reference Insel and Akiskal1986; Eisen & Rasmussen, Reference Eisen and Rasmussen1993). At a rough guess, it is probably seen in around 10 per cent of patients with the disorder, although the variation around this figure was wide in three large surveys (Eisen & Rasmussen, Reference Eisen and Rasmussen1993; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Kozak and Goodman1995; Catapano et al., Reference Catapano, Sperandeo, Perris, Lanzaro and Maj2001). This uncertainty almost certainly reflects what the authors of these surveys were prepared to accept as evidence of the obsession not being considered irrational, from patients actually believing that the feared consequence would actually occur if a ritual was not performed, to feeling that the obsession was reasonable, to defending their beliefs against counterargument.

It has to be said that not all the examples of this phenomenon that have been described are convincing. Thus, in one of the seminal articles on the subject, Insel and Akiskal (Reference Insel and Akiskal1986) described four patients. One of them recognized that his obsession about contamination with germs was irrational, but he was considered to show a commitment to it by virtue of the fact that he covertly wore surgical gloves and stuffed his sheets into the hospital incinerator every morning – hardly unusual behaviour in obsessive-compulsive disorder. In another influential account Solyom et al. (Reference Solyom, DiNicola, Phil, Sookman and Luchins1985) described a group of eight patients who had obsessions with no feeling of subjective compulsion and without insight and resistance. However, three were described as having disturbance of body image as their major symptom, raising the possibility that they might have been better diagnosed as suffering from body dysmorphic disorder. Another of the patients was described as having a hypochondriacal obsession; here it seems possible that the diagnosis could have been hypochondriasis: patients with this latter diagnosis are often misdiagnosed as having obsessive-compulsive disorder before the clinician belatedly realizes his or her mistake (the present author has done this several times). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that patients exist who truly believe that their obsessions are rational. An example is shown in Box 2.4.

Box 2.4 A Patient Who Firmly Believed in Her Obsessions (Reproduced with permission from Foa, Reference Foa1979)

Judy was a 37-year-old artist, married to a businessman. They had three children, ages eight, six and three. She was afraid of being contaminated by leukaemia germs which she would then transmit to her children and husband. She described the following at her first interview with her therapist:

T. I understand that you need to wash excessively everytime you are in contact, direct or indirect, with leukemia.

P. Yes, like the other day I was sitting in the beauty parlor, and I heard the woman who sat next to me telling this other woman that she had just come back from the Children’s Hospital where she had visited her grandson who had leukemia. I immediately left, I registered in a hotel, and washed for three days.

T. What do you think would have happened if you did not wash?

P. My children and my husband would get leukemia and die.

T. Would you die too?

P. No, because l am immune, but they are particularly susceptible to these germs.

T. Do you really think people get leukemia through germs?

P. I have talked with several specialists about it. They all tried to assure me that there are no leukemia germs, but medicine is not that advanced; I am convinced that I know something that the doctors have not yet discovered. There are definitely germs that carry leukemia.

T. What is the probability that if you didn’t wash after the incident in the beauty parlor your family would get leukemia?

P. One hundred per cent. They might not get it immediately, these germs could be in their bodies for five or even ten years. Eventually they will have leukaemia. So you see, if I don’t wash, it’s as if I murdered them.

In a few cases the ideas enter very strange territory indeed. O’Dwyer and Marks (Reference O’Dwyer and Marks2000) described a series of five patients who had elaborate beliefs in the context of what were otherwise clear-cut obsessive-compulsive illnesses. One of these was a young man with rituals which completely dominated his life. These related to a ‘power’ he believed he had, which he felt brought him luck and he was in constant danger of losing. He also believed there was a second power of evil, possessed by a workman, and he developed a separate set of rituals to ward this off. He believed implicitly in these powers and feared terrible consequences for him and his family if he did not retain the former and repel the latter. On one occasion, at the beginning of his illness he had seen a man’s face at a glass door and heard a voice say, ‘Do the habits and things will go right.’ He also claimed that when he experienced loss of the good power, he would see a black dot about the size of his fist leaving his body. Another patient, a man in his late thirties, had the fear that reflections in mirrors represented another world and developed rituals in relation to this. He feared being transported into this other world and sometimes believed that he had actually been transported there: when this happened he believed he would be forced to stay there if he ate while in it. The other world looked the same as the real one, but ‘felt’ different and he wondered whether his family and friends had been replaced by identical appearing doubles. Both patients failed to respond to antipsychotic drug treatment, but the first improved markedly on treatment with clomipramine and behaviour therapy, and the second improved moderately on behaviour therapy alone.

All this naturally raises the question of whether there is some kind of deep link between obsessions and delusions. This view gains strength from claims, made from the nineteenth century onwards, that obsessions can sometimes transform into delusions (see Rosen, Reference Rosen1957; Burgy, Reference Burgy2007). This is said to happen when a patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder develops major depression, or when an illness that starts off as obsessional later reveals itself to be schizophrenia, both of which are well-documented occurrences (e.g. Stengel, Reference Stengel1945; Gittleson, Reference Gittleson1966). Bleuler (Reference Bleuler1924) was an early supporter of this view. On the other hand, Schneider (1925, quoted by Burgy, Reference Burgy2007), denied that such transitions ever occurred.

Gordon (Reference Gordon1926) set out to answer the question empirically. He collected a series of six patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who later developed delusions, in most cases in the context of a depressive illness. He found a reasonably direct relationship between the content of the obsession and the content of the delusion in one case. This was a 13-year-old girl who developed obsessional doubts about whether she had carried out actions like writing, speaking and walking correctly, and would have to repeat the actions several times before she was satisfied. At the age of 18 she started working as a kindergarten teacher, and shortly afterwards began to dwell on the idea that she was not teaching her pupils correctly. This then became a conviction that she had taught her pupils the opposite of what they needed to know, and that she would be dismissed and would never be able to work again. She later started to hear the children’s voices reproaching her and then God’s voice telling her that both she and her parents would be sacrificed.

In two other patients the link was less straightforward. One had longstanding hypochondriacal preoccupations about the function of his intestines, liver and kidneys, ‘which he genuinely doubted’. Several years later he developed persecutory and referential delusions, probably in the context of major depression, and came to believe that he was correct about his previous health concerns. The other patient had experienced a compulsion to repeat his prayers without missing out a word for two years. Towards the end of this period he gradually developed an explanation for doing this, that since he had to pray there must be some divine reason for it. He went on to believe he was a sinner and deserved everything that happened to him or would happen to him. He no longer questioned the necessity of praying. He later developed visual and auditory hallucinations.

Further studies are decidedly thin on the ground. Those that the present author has been able to find are summarized in Table 2.2. In most cases the link is less than direct or there is some other complication. Thus, one of Stengel’s (Reference Stengel1945) patients had had sadistic and blasphemous thoughts from childhood which included violent ideas towards women. In adult life he developed a paranoid illness where one of his beliefs was that women were the cause of all the evil in the world. Stengel (Reference Stengel1945) considered that the delusion was not a derivative of the obsession, although the contents of both were related to the patient’s underlying impulses and complexes. In another of his cases, a woman started washing her hands compulsively in response to a fear of germs and also of dog excrement and earthworms. Seven years later she developed an illness that was probably schizophrenia. One of her symptoms was eating dead flies, earthworms and animal excrement, which she explained was to glorify God by humiliating herself and doing things she abhorred.

Table 2.2 Studies of Obsessions That Convert to Delusions

| Study | Patients | Direct Link between Obsession and Delusion | Indirect Link between Obsession and Delusion | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gordon (Reference Gordon1926) | Six obsessive-compulsive patients who developed major depression or schizophrenia | 1 | 2 | See text |

| Stengel (Reference Stengel1945) | Fourteen patients in whom obsessional symptoms preceded depression or schizophrenia | 0 | 2 | See text |

| Rosen (Reference Rosen1957) | Thirty schizophrenic patients in whom obsessional symptoms had been observed at some point | ?1 (not clear if the patient had actually developed schizophrenia) | 2 | See text |

| Goldberg (Reference Goldberg1965) | Four patients with mixed obsessional and paranoid symptoms over many years | 0 | 0 | Three cases were of morbid jealousy; the fourth simply had an obsessional fear that he was suspected of theft. |

| Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Winnik and Weiss1976) | Three cases of ‘obsessive psychosis’ | 0 | 0 | The patients all lacked insight into their obsessions, leading to a diagnosis of psychosis being made on psychoanalytic grounds. |

| Insel and Akiskal (Reference Insel and Akiskal1986) | Four cases of obsessive compulsive disorder with psychotic features | 1 | 0 | See text |

Rosen (Reference Rosen1957) described four apparent transitions in an examination of the case notes of 30 schizophrenic patients who had at some point experienced obsessions. In two, it was clearly not a case of direct transformation. One patient had fears of contamination and harm through loose objects lying about and later developed beliefs about being poisoned and had hallucinations of people falling off roofs and being pushed down drains. The other, a woman who initially had a compulsive urge to look at men’s genitals later came to believe that everyone knew that she had this compulsion. In a third patient, the transition was not to delusions: a patient who had previously experienced single words coming into her mind later developed thought insertion which sometimes included the same words. The most direct link was in a patient who developed an obsession that she might harm someone and four years later started to believe that she might harm God; she also began hearing His voice saying this. However, it is not altogether certain that this patient had actually developed schizophrenia: although she expressed the belief that she might harm God, she carried on performing rituals in response to this idea and was aware of the absurdity of it. The author’s statement that the patient ‘was not entirely convinced that the hallucinations were due to her imagination’ might also raise doubts about whether what she was experiencing was truly hallucinatory in nature.

In Insel and Akiskal’s (Reference Insel and Akiskal1986) series of four patients, a link between the content of the obsession and the content of the delusion was considered to be present in only one. This was a patient with a long history of obsessive checking who became preoccupied with the idea that he may have inadvertently poisoned the children’s juice in the day centre where he worked. Later he was admitted and while in hospital developed a short-lived psychotic state. As part of this, he became convinced that the hospital staff in collusion the FBI believed he had committed this crime. However, he maintained that he did not do this.

Conclusion: The Complexity of Pathological Belief

The simple answer to the question of when a delusion is not a delusion is ‘When it is an overvalued idea’. Despite being ignored, misunderstood and lost altogether on American psychiatry (it is difficult to resist the temptation to say undervalued), there seems to be a clear need for such a second category of abnormal belief. Trying to deny its existence simply leads to contradictions, of which the nature of the belief in anorexia nervosa is the most glaring example. In an ideal world, it might be better to start afresh with a different name for this form of psychopathology, such as quasi-delusions, or non-psychotic delusions, or even perhaps type II abnormal beliefs. But the fact is that the term overvalued idea not only has the force of history behind it, but also actually captures the phenomenological features of the symptom quite nicely.

Whatever else it is, the overvalued idea is not a halfway house between normal beliefs and delusions. However, a form of abnormal belief that gives an almost irresistible impression of being so exists in the ideas of hopelessness, self-depreciation and self-blame seen in major depression – Beck’s depressive cognitions – and the corresponding grandiose ideas in mania. Does this mean that all delusions, not just those seen in major affective disorder, are on a continuum with other less pathological ideas, perhaps even with beliefs we all hold at certain times? This seems on the face of it to go against the conclusions reached about the nature of delusions in Chapter 1. On the other hand it is the position taken by a currently highly influential theory, the so-called continuum view of psychosis, which is considered in detail in Chapter 4.

If there are some types of abnormal belief that are not on a continuum with delusions and some that are, where do obsessions stand? On balance, the evidence seems to be more in line the former. There can be no doubt that obsessions are sometimes held with firm conviction. However, in most cases where this happens the beliefs continue to look like obsessions rather than, say, overvalued ideas – the patient in Box 2.4, for example, still responded to her idea about ‘leukaemia germs’ by performing compulsive rituals and did not develop a hypochondriasis-like pattern of help-seeking behaviour. Rarely, as in the cases described by O’Dwyer and Marks (Reference O’Dwyer and Marks2000), the beliefs go further, to the point that the patient seems to be fully committed to what might be termed an obsessional fantasy world. But even here the resulting state does not seem to resemble psychosis in key ways, not least its response to treatment. The acid test of the existence of a continuum between obsessions and delusions is whether the former can sometimes transform into the latter. Given that only at most two or three convincing examples of this phenomenon have ever been recorded, the verdict here has to be one of ‘not proven’.