8 A valley for the kings

8.1 A new renaissance

The Middle Kingdom ended along with the twelfth dynasty. Under the thirteenth dynasty, the country began to split up again into two lands, with the foreign Hyksos taking gradual control of Lower Egypt. The process leading to a second reunification was launched by the Theban rulers of the seventeenth dynasty and can be said to have been completed with the reign of Ahmose (1550–1525 BC), the founder of the eighteenth dynasty (Shaw Reference Shaw2000). The transformation initiated in the Middle Kingdom, when the twelfth dynasty kings had favoured Amun as the main deity, was concluded, so that Thebes became the main religious and power centre of the whole country and Karnak the most important temple in Egypt.

The Theban rulers before Ahmose were buried in tombs excavated along the slopes at Dra Abu el Naga, a series of low cliffs to the north-west of the Deir el Bahri bay. Their tombs were arranged one after the other, respecting a south-of-west progression (Winlock Reference Winlock1924). Ahmose, on the other hand, evidently wished to give a strong signal of the return to an ancient tradition, for he constructed a majestic funerary monument at Abydos (Harvey Reference Harvey1994, Reference Harvey1998). The complex is close to that of Senwosret III and parallel to its axis (Figure 1.2). It included a pyramid which is currently in very poor condition but which must have been a reasonably distinctive and striking monument on the Abydos landscape. At present, no subterranean structure has been identified in it. However, on the axis with the pyramid towards the cliffs lies a rock-cut underground complex, surmounted by a terraced temple, built up against the mountain. The complex bears a resemblance to Senwosret III’s tomb nearby but, as with the latter, it is not known for certain whether it was a cenotaph or if the king was interred there. His mummy has actually been recovered, in the so-called Deir el Bahri cache, a tomb in western Thebes which was used by twenty-first dynasty priests, alarmed by plundering of ancient burial sites, to store dozens of royal mummies which had been gathered from their original sepulchres. So there exists the possibility that the king had a Theban tomb, though it has never been found.

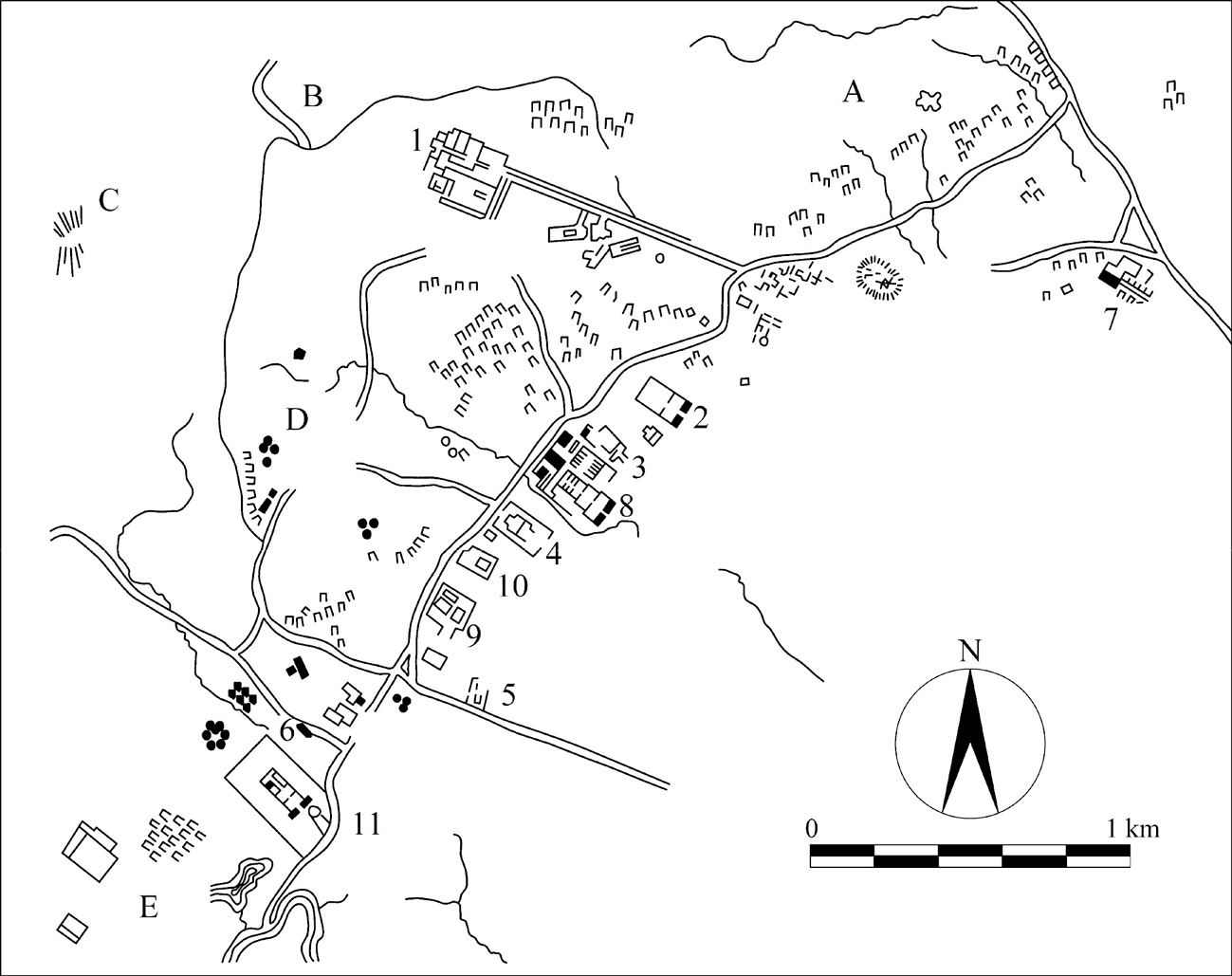

The pyramid of Ahmose is the last royal pyramid to be constructed in Egypt. Immediately thereafter, a clever new way of concentrating almost all the symbols and the icons associated with the afterlife – including the pyramidal shape – into an extremely restricted space was invented. The king responsible was probably Ahmose’s successor, Amenhotep I. His reign was relatively peaceful: the king devoted himself to the organisation of the state and instituted several important traditions which would be followed by almost all his successors. First of all, he wished to leave tangible traces of his reign at the temple of Karnak, where he ordered the construction of a huge limestone gateway. Second, he was the first king to inaugurate the tradition of constructing memorial temples in western Thebes. These temples, which were to acquire enormous importance with later kings, are usually called “funerary”. They were indeed devoted to the cult of the deceased king, but with the addition of a rather complex series of implications which we shall be exploring later. Finally, as mentioned, Amenhotep I was probably the founder of a new royal necropolis, in the wadi today known as the Valley of the Kings (Figure 8.1).1

8.1. Map of western Thebes. The royal funerary temples are numbered in chronological order, while capital letters denote geographical areas: (A) Dra Abu el Naga; (B) Valley of the Kings; (C) el Qurn; (D) Deir el Medina; (E) Birket Abu; (1) Hatshepsut; (2) Thutmose III; (3) Amenhotep II; (4) Thutmose IV; (5) Amenhotep III; (6) Ay-Horemheb; (7) Seti I; (8) Ramesses II; (9) Merenptah; (10) Siptah-Tawosre; (11) Ramesses III.

The main hint that Amenhotep I was the founder is that he was granted the honour of being declared patron god of the necropolis, along with his mother, Ahmose Nefretiri. They were worshipped in specially built temples at Deir el Medina, the town where the workmen of the valley lived. The question would, of course, be settled if it could be shown that Amenothep I was buried in the valley, but this has not yet been possible. The burial of the king is mentioned in an official document of inspection of the royal tombs drawn up during the twentieth dynasty, the Abbott Papyrus, where the inspectors’ itinerary is described in some detail. The document is difficult to interpret, though, because it mentions in passing two buildings by Amenhotep I, presumably temples, whose locations are uncertain (one of them is perhaps the one documented by Howard Carter at Deir el Bahri, now lost). The text does show that the king was buried in western Thebes, but from an archaeological point of view, we have not one but two likely candidates for his tomb, of which only one is in the Valley of the Kings. The tombs there are labelled by the letters KV followed by a number, and the one in question is KV39, located on the very edge of the valley, some 200 metres south of the later Thutmose III tomb, very close to the path ascending from the labourers’ village and thus in a perfectly natural position to be “the first tomb built”. However, a recent re-excavation has failed to come up with any definitive proof for Amenhotep I, and many Egyptologists believe that the king’s tomb is, rather, that labelled AN-B, located on the high cliffs over Dra Abu el Naga, based on the evidence of numerous fragments inscribed with the name of the king and his mother found there (see a complete discussion in Reeves and Wilkinson Reference Reeves and Wilkinson1996, and references therein). From the topographical point of view, it should be observed that AN-B is located in a dominant position in relation to the royal tombs of the seventeenth dynasty, which spread from north to south on the low slopes below. It is a fairly unusual topographical relationship for a royal tomb when compared to previous ones, especially considering that the latter follow a south-of-west progression. On the other hand, KV39 is actually to the south-west – although in a completely different place – of all these tombs.2

8.2 A valley for the kings

So much for Amenhotep I’s tomb. From the time of his successor, Thutmose I (1504–1492 BC), the rulers of the New Kingdom were buried in the Valley of the Kings (Reeves and Wilkinson Reference Reeves and Wilkinson1996; see, however, Romer Reference Romer1975). The valley (Photo 8.1) is today approached from a route to the west, but in ancient times this path was blocked – more or less near today’s ticket office – by a natural rock wall 5 metres high, removed only in modern times. Access from there was possible, but people were forced to climb the wall through an opening in the rocks. The valley was thus mainly entered by tracks over cliffs, one starting at Deir el Bahri, the other, smoother and perhaps used for the last part of the funeral of the king after the rites in the funerary temple, crossing the hill from Deir el Medina (Romer Reference Romer1981; Hornung Reference Hornung1990).

Photo 8.1. Western Thebes. The Valley of the Kings, with the modern access corridors to the tombs. The peak of el Qurn is visible to the left.

The choice of the valley for the royal necropolis was in all probability influenced by symbolic criteria. First of all, as has been repeatedly observed in the literature, its position behind the cliffs at the western horizon as seen from Thebes assimilated the king’s death and rebirth with the solar cycle. In fact, such a statement can be validated further, in a quantitative sense, if one notes that the axis of the Karnak temple of Amun – by far the most important religious centre in Egypt during the New Kingdom – passes along the northern rim of the Deir el Bahri bay. The Karnak temple axis, as we have seen, is oriented to the winter solstice sunrise to the south-east but opens towards the opposite orientation (which would be to the summer solstice sunset with a flat horizon) and therefore specifically towards the hills which guard the entrance to the valley. Thus, although the last rays of the sun do not penetrate the temple, the summer solstice sunset observed from Karnak is still very striking if the observer is aware – as the ancient Egyptians naturally were – of what is concealed behind the hills.3

Other symbolism implicit in the choice of the valley is connected with the prominent peak of el Qurn. This peak’s resemblance to a pyramid is obvious from any side but becomes quite extraordinary when the mountain is seen from the east, to the extent that one might suspect that the natural pyramidal shape was deliberately adapted by sculpting on that side. The peak itself, however, was not used for carving out the tombs, nor are the orientations of tombs and temples aimed towards it. The function of this peak is, accordingly, not directly connected with the funerary cult. We might consider it instead as a familiar, widely recognised marker of the presence of the royal burials.

As far as the interior of the tombs is concerned, they contain a renowned collection of magnificent decorations, and, in particular, of scenes extracted from funerary texts, which in the New Kingdom become a sort of illustrated map to the netherworld. The form of art is pictographic: vignettes accompanied by explanatory texts. The oldest is the Amduat, which we have already discussed. The most spectacular version of the Amduat is certainly that visible in the burial chamber of the tomb of Thutmose III, KV34. The decorations here are drawn in such a way as to give the impression of a huge papyrus unrolled and used to upholster the walls; the chamber itself is of oval shape, not unlike a king’s cartouche. Generally speaking, the interior of the royal tombs does not follow a rigid pattern. Their topography can, however, be subdivided into three successive stages, roughly corresponding to dynasties eighteen, nineteen and twenty: early tombs with curved axes; intermediate tombs where the entrance corridors curve abruptly to one side at a pillared hall about halfway into the tomb; and later tombs with straight axes. It is usually claimed that subsequent sections were symbolically linked to the nocturnal journey of the sun, so that the interior of the tomb mimics the topography of the beyond. The true significance of some elements remains elusive, however; for instance, was the impressively deep well, excavated in a special room on the corridor from the reign of Tuthmosis III onwards, a functional element to stop rainwater from collecting and robbers intruding, a symbolic element, or both?

Another point deserving our attention is of course orientation, both practical and symbolic. The importance of astronomy in the management of religion and power at that time is clearly alluded to in the depiction of astronomical texts on the walls of the tombs, starting from the nineteenth dynasty. These texts include star clocks and the “astronomical ceilings”, representing an image of the sky as the Egyptians were accustomed to seeing it – that is, of the Egyptian constellations (see Section 2.2 of Box 2). In spite of this, it is difficult to individuate a role for astronomy in the planning of the tombs. The access corridors face the interior of the wadi so their horizon is usually high. Analysing the corresponding declinations, it turns out that during the eighteenth dynasty the vast majority of the tombs were in the solar range, with declinations between −24º and +24º, with three exceptions looking towards Thoth Hill to the north (García, Belmonte and Shaltout Reference Belmonte, Belmonte and Shaltout2009). The sun in the (open) tombs could thus shine up to the shaft room. I do not think, though, that any particular symbolism can be attached to this pattern: the tombs were meant to be closed and probably also concealed from view. Besides, when the tombs were later to acquire a straighter axis, there is a lack of any recognisable orientation pattern. An exception is perhaps that of three tombs oriented close to due west. This orientation might be symbolic since these are Hatshepsut’s (KV20), Amenhotep III’s (WV22) and tomb KV55, which is a burial place for members of the Amarna royal family (possibly also for the reburial of Akhenaten), hence those very three Pharaohs who, as we shall see, had, for different reasons, a “special affinity” with the sun god.

A further issue is the presence of purely symbolic references in the interior of the tombs; for instance, symbolism connected with the sun’s positions may be perceived in eighteenth dynasty tombs, due to different colours being adopted for sun symbols in various places inside (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1994b). Generally speaking, however, royal tombs are flat, linear, “two-dimensional” affairs, corresponding exactly to how the netherworld is represented in the vignettes of the funerary texts, without any attempt at perspective. A notable exception, which actually shows efforts being made to achieve perspective in the pictography of the afterworld (for example, in the Ani Papyrus, Folio 33; see Faulkner Reference Faulkner1994), is related to a process of “cosmisation” of the burial, which occurred quite analogously in many other cultures (Krupp Reference Krupp1997; Ruggles Reference Ruggles2005; Magli Reference Magli2009a). This process consisted of marking with special protectors the four walls (ideally, the four cardinal points), so that the tomb – on the basis of the process of “the founding of the human space” we described in Chapter 1 – became the centre of the world, the place where main directions cross each other. In Japan, for example, some excavated funerary chambers of the so-called Kofuns (burial tumuli constructed between the third and the seventh centuries AD) contain images, painted on the walls, of four animals also symbolising the four cardinal points and the four seasons: the Azure Dragon of the East (spring), the Red Bird of the South (summer), the White Tiger of the West (fall) and the Black Turtle of the North (winter). A starry ceiling completes the decoration. In Egypt, the “cosmisation” of the funerary chambers begins at Abydos, with inter-cardinal orientation, and continues with the rigorous orientation of the pyramids to the cardinal points and the distribution of the Pyramid Texts on different walls and chambers. In the Middle Kingdom, coffins are “oriented”: their eastern part is the long side, identified on the exterior by the double eye ![]() -udjat, symbolically looking at sunrise and rebirth; consequently, the whole coffin is oriented as well, and the inscription on the exterior runs accordingly “from north to south”. In the New Kingdom, the tradition of the so-called magic bricks was established (see, for example, Silverman Reference Silverman, Der Manuelian and Freed1996; Taylor Reference Taylor and Davies1999). These were bricks inscribed with spells against the enemies of Osiris, one for each of the four walls and, symbolically, for each cardinal point. In many cases, the bricks had sockets into which an amulet could be inserted, facing the relevant wall. The amulets were a Djed pillar for the west, Anubis for the east, a shabti (a mummy-form figure of the deceased which can be magically activated) for the north, and a torch for the south. Each brick was inscribed with passages from Spell 151 of the funerary text called The Book of the Dead, where four “genies” (the “four sons of Horus”) are invoked for protection. They are: Amseti with human head, Hapy with baboon head, Kamutef with jackal head, and, finally, the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef. Their role was also associated with the protection of the viscera (liver, lungs, spleen, intestines) of the deceased, contained in canopic jars. The choice of the number four for the canopic jars is therefore also symbolic, as there are of course many other items of viscera which were not extracted, or were extracted but not conserved.

-udjat, symbolically looking at sunrise and rebirth; consequently, the whole coffin is oriented as well, and the inscription on the exterior runs accordingly “from north to south”. In the New Kingdom, the tradition of the so-called magic bricks was established (see, for example, Silverman Reference Silverman, Der Manuelian and Freed1996; Taylor Reference Taylor and Davies1999). These were bricks inscribed with spells against the enemies of Osiris, one for each of the four walls and, symbolically, for each cardinal point. In many cases, the bricks had sockets into which an amulet could be inserted, facing the relevant wall. The amulets were a Djed pillar for the west, Anubis for the east, a shabti (a mummy-form figure of the deceased which can be magically activated) for the north, and a torch for the south. Each brick was inscribed with passages from Spell 151 of the funerary text called The Book of the Dead, where four “genies” (the “four sons of Horus”) are invoked for protection. They are: Amseti with human head, Hapy with baboon head, Kamutef with jackal head, and, finally, the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef. Their role was also associated with the protection of the viscera (liver, lungs, spleen, intestines) of the deceased, contained in canopic jars. The choice of the number four for the canopic jars is therefore also symbolic, as there are of course many other items of viscera which were not extracted, or were extracted but not conserved.

8.3 The Hatshepsut projects

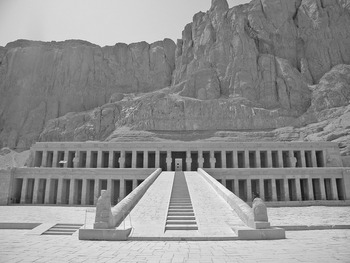

On the death of Amenhotep I, his son Thutmose I ascended to the throne, to be succeeded in turn by his son Thutmose II. Thutmose II died shortly after marrying his half-sister Hatshepsut. He left a young boy (fathered with another wife), Thutmose III, as heir to the throne, but Hatshepsut became regent. At any rate, she managed to proclaim herself Pharaoh and ruled for about 20 years before leaving the throne to the legitimate heir (probably on her death). To legitimise her own rights to the monarchy, Hatshepsut claimed direct descent from Amun-Ra. To validate this ideology, she started an ambitious building program on both the Theban banks of the river, establishing a series of ideological patterns and ideas which would be widely followed in later years. The masterpiece of her building programme is the funerary temple called Djeser-djeseru, the “most holy place” (Photo 8.2).

Photo 8.2. Western Thebes. The terraces of the Hatshepsut temple at Deir el Bahri.

The temple was designed as a sort of artificial extension of the cliffs of the Deir el Bahri bay, and is thus superbly integrated with the natural landscape. It consists of three court terraces separated by front colonnades and linked by ascending ramps, with dimensions deftly calculated to create stunning theatrical effects. The upper terrace had an entrance portico adorned with images of the queen in Osiris form, guarding the final sanctuary, a rock-carved chapel of Amun. (The tomb of the Pharaoh Queen in the Valley of the Kings is located roughly in correspondence with the temple axis on the opposite side of the cliff.) The architect responsible for the temple was Senenmut, a fairly important figure who also had an (unfinished) tomb excavated for himself in the flank of the temple hill.4 Hatshepsut’s architecture as executed by Senenmut on both banks of the Nile stresses the importance of the sun. The funerary temple is oriented to the winter solstice sunrise; today a wall prevents the rising sun from filtering up to the final sanctuary, but this phenomenon probably occurred in ancient times. The same orientation was emphasised by Hatshepsut in her additions to Karnak. Indeed, although the axis of the Karnak temple had been oriented to the winter solstice sunrise since the Middle Kingdom, the main front of the temple was facing west. Hatshepsut chose to add a structure that was open to the south-east, dedicated to Amun-Ra who hears the prayers. The building was aligned on the same axis as the pre-existing temple but was explicitly linked to the sunrise, and a group of seated statues representing Hatshepsut and Amun-Ra was the first element to be illuminated by the rising sun in the days around the solstice, creating a spectacular hierophany (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1974; Krupp Reference Krupp and Ruggles1988).

Hatshepsut’s need to evince a direct connection with the sun in order to legitimise her reign is made clear also by other elements of her building activities. Included in her plan was, for instance, the erection of two obelisks along the Karnak axis – today no longer standing – dedicated to marking the places “where my father rises”. As part of the ideological propaganda aimed at validating her reign, it also appears that Hatshepsut was the first Pharaoh to promote the worship of a “Theban triad” of gods, formed by Amun, Mut and Khonsu. Mut was an ancient Theban goddess associated with creation. As Thebes grew in importance, she was identified with the wife of Amun and mother of their son Khonsu, who in turn gradually replaced the other ancient Theban god, Montu. At Karnak, Khonsu was worshipped in a temple located to the south of the main building, while his mother had a specially built precinct to the south-east. A visit to the Mut precinct is a unique experience for two reasons. First, the area is filled with hundreds of basalt statues of the goddess in her lion-headed form, the warrior goddess Sekhmet, whose carving is apparently due to Amenhotep III (but some think that the original project was also Hatshepsut’s). Second, the temple is unique in being surrounded on three sides by a sacred lake shaped like a lunar crescent. Various interpretations have been put forward for this; some think that the lake was meant to constrain the potentially dangerous leonine goddess, others that the lake is an allusion to her son Khonsu, who was associated with the moon and depicted as a falcon wearing a crescent and moon disk on his head. No orientation to the moon can, however, be recognised there.

To the immediate south of the temple, excavations are gradually bringing to light a straight avenue flanked by hundreds of sphinxes. The sphinxes are a relatively recent addition (fourth century BC), but the avenue is much older and can probably be ascribed to Hatshepsut as well. It leads to the most important temple after – or perhaps even on a par with – Karnak: Luxor.

8.4 The sanctuary of the south

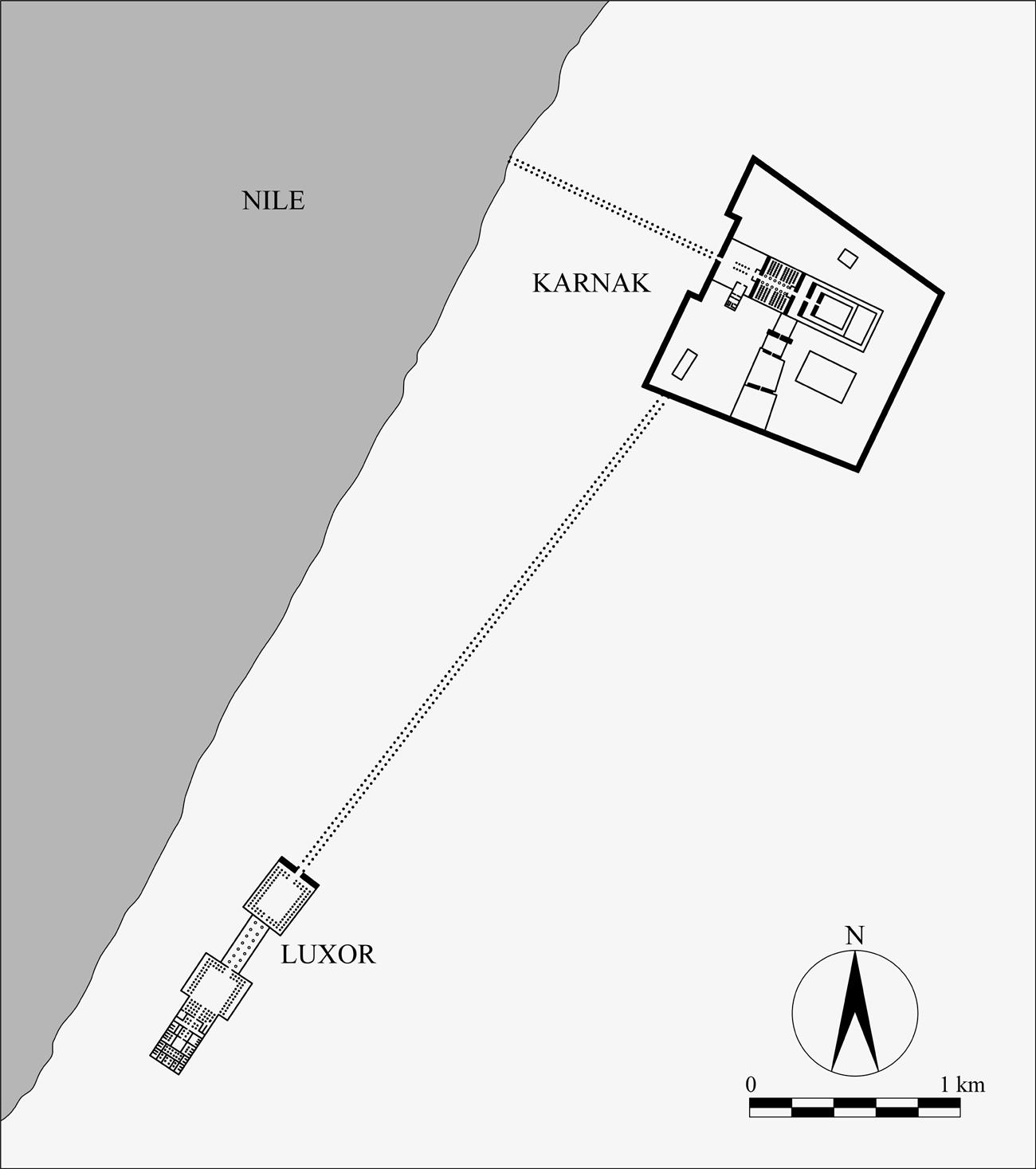

The so-called temple of Luxor is located along the Nile some 3.5 kilometres to the south-west of Karnak (Figure 8.2). Known in ancient times as the “sanctuary of the south”, it was principally dedicated to Amun, worshipped here as a fertility and creator god, Amenemopet (Bell Reference Bell and Arnold1997).

8.2. Plan of the Karnak and Luxor temples, connected by the Alley of the Sphinxes. Notice that the Karnak axis goes perfectly straight, while the Luxor axis bends several times.

There is a suspicion that the foundation of this temple dates to the Middle Kingdom, but conclusive proof has never emerged, as the earliest reference so far comes from an inscription, discovered in a quarry near Memphis, dating from year 22 of the reign of Ahmose. The earliest architectural evidence, on the other hand, comes from Hatshepsut’s reign, although most of her buildings were subsequently destroyed and the magnificent temple we can see today is mostly the work of Amenhotep III and Ramesses II (Badawy Reference Badawy1968).

Amenhotep III’s buildings at Luxor were planned in two different stages. In the first stage, the intricate, secluded multiroom complex which stands today at the very end of the temple was erected (perhaps on a small “primeval” hill, although many Egyptian temples – for instance Medinet Habu – claimed such an honour); later a huge open court with a magnificent access colonnade (completed by Tutankhamun after the Amarna period) was added. Later on, major additions were made by Ramesses II, which consisted of an entrance pylon (Photo 8.3) with a pair of huge obelisks in front of it and a large pillared court. Inside this court, to the right of the entrance, a triple shrine can be seen. The structure – which replaces the last “way station” previously built by Hatshepsut – was used for housing the barks of the statues of Amun, Mut and Khonsu of Karnak. Luxor and Karnak were in fact closely connected. Every year, the statues of the Theban triad visited Luxor in a procession known as The Beautiful Festival of the Opet (Cabrol Reference Cabrol2001). This festival, together with the “Beautiful Feast of the Valley”, which we shall encounter later, and the feast of Osiris, was the most important of several held yearly in honour of the gods in ancient Egypt. It commenced with the Karnak statues being loaded onto ceremonial barks under which long stakes were inserted. Baldachins were then carried on the shoulders of the priests; the religious procession moved towards Luxor along the avenue mentioned earlier. Today this avenue is lined by the hundreds of Sphinxes added subsequently by Nectanebo II, but Hatshepsut had already equipped it with six “bark stations”. At each station, the cortège stopped and the priests performed ceremonies.5

Photo 8.3. Luxor. The Ramesses II pylon of the temple seen from the final section of the Alley of the Sphinxes. The displacement of the axis of the first court with respect to the front can be perceived.

Renewal was the focus of this feast, and countless offerings of flowers, symbols of renewal, were brought to the temples. The idea of the renovation of power – both divine and royal – is certainly not new, as it can be traced back to the Early Dynastic period and the Sed festivals. The New Kingdom kings also celebrated Sed festivals, but the yearly feast of the Opet fulfilled a different function, connected to the relationship of the common people with the divine. Public access to temples was in fact forbidden, so the idea of circulating the god’s statues back and forth met the need to have contact, however detached and perfunctory, with the gods. The Pharaoh, in accordance with his divine nature, had of course a key role, for the festival was connected with the renewal of the Ka of the king and – by extension – to that of all people. The Pharaoh himself made a sort of reappearance, having changed his clothes, after the entrance of the procession into the recessed part of the Luxor temple. The secluded rites included a repetition of the coronation, with the king receiving the two crowns in front of the god’s image and presenting special offerings.

Was the “sanctuary of the south” – and the explicit manifestation of the Pharaoh’s power associated with it – tied up with astronomy? And if so, in what way?

Contrary to what transpired at Karnak in the course of more than one millennium, where subsequent additions did not alter the axis’ direction towards the rising sun at the winter solstice, at Luxor at each enlargement a bend of the axis was effected. The bends are initially almost imperceptible: the inner court has an azimuth ~34°, which changes to 35½° for Tutankhamun’s court. Then, however, the turn to the west becomes clearly perceptible with the Ramesses II addition, though the court and the pylon of this king are not aligned with each other, bearing azimuths 42½° and 39½°, respectively. The presence of these bends makes a visit to the temple a strange experience: at the entrance, the line of sight along the open hall is perceived at an angle in relation to the front pylon, and the linear perspective of the colonnade on the opposite end does not reveal the presence of the vast inner court which follows (Photo 8.3).

The riddle of the Luxor bent axis has been the subject of several unsuccessful attempts at explanation, including an astronomical one. In particular, in the nineteenth century, Egyptian chronology was very different from today and had (wrongly) been shifted backwards by many centuries. Using this chronology, Lockyer (Reference Lockyer1894) associated the changes of the axes with the precessional drift of the rising point of the bright star Vega. However, this solution cannot be reconciled with the currently accepted chronology. The changes in the axes thus remain unexplained, as they were not necessary to keep the building parallel to the Nile – which has not altered its course much since then, as the ancient quay connected with the temple clearly shows. To find the most plausible reason for the deviation of the Ramesses II addition, we must first analyse the Karnak to Luxor avenue.

Unlike what happened with the Luxor temple proper, important astronomical events took place at the time of construction at both ends of this avenue. The pathway proceeds very straight along its 2 kilometre course, and its azimuth from Luxor to Karnak can be estimated quite precisely to be 45° (data from the author) (Figure 8.2). Clearly, this choice is hardly random, as it is the inter-cardinal orientation we have already encountered many times; furthermore, it was not constrained by local topography. We already know that this direction is out of the solar and lunar range, and that it generally corresponded to the Milky Way. Actually, if we take Hatshepsut’s accession as a reference point (say around 1470 BC), then we can see that the region of azimuths close to 45° was particularly crowded by the rising of bright stars: the “northern branch” of the Milky Way with Cygnus, but also Arcturus and Vega. Equally luminous was the horizon at the opposite end (azimuth 225°), where the brightest part of the Milky Way – and, in particular, the Southern Cross – sat in alignment with the avenue in the direction of Luxor (Tables A.1 and A.2). The two centuries or so separating Hatshepsut from Ramesses II were not sufficient for precession to destroy these phenomena, so that 200 years later the spectacle was still quite effective, and Ramesses II provided an artificial horizon for it with the erection of the external pylon and the two obelisks at the end of the avenue. But the large (7°) bend of the Ramesses court also had another aim. In fact, the project was designed in such a way that Luxor became a sort of double-faced temple, since a visual axis connects the chapels of the bark stations with the inner sanctuary (Photo 8.4). In this way, when occupied by the statues, the chapels played the role of alternate inner sanctuaries located at the opposite end.

Photo 8.4. Luxor. The axis of the Amenhotep III colonnade of the Luxor temple viewed from the back end.

We might say, then, that the symbolic relationship between Karnak, the main “house” of Amun who hears the prayers, and Luxor, the main “house” of Amun as a creator (or re-creator) god, responsible for renovating the Ka of the Pharaoh, was heightened by a series of references to Egyptian conceptions of the sacred space which would have been quite familiar. Basing on the astronomical and topographical observations presented earlier, I think that the “sanctuary of the south” – where the power of the gods was “re-enhanced” and, in a sense, resuscitated – can be seen as a sort of gigantic Serdab, and in fact the ceremonies held in the most secret part of the temple (the so-called Opet temple, located to the back of the main building) probably included the Opening of the Mouth performed by the Pharaoh on the statue of Amun of Luxor, Amenemopet. The Luxor temple is actually to the south-west of Karnak and connected to it by the alley oriented precisely along the inter-cardinal direction. It is therefore in a position which is also the “classic”, almost mandatory position for the tomb of the successor to a revered king. In this case, however, the successor is no one but the “renewed” Pharaoh who, as well as a rejuvenated Amun god, succeeds himself.

An aura of mystery surrounds the temple of Luxor even today, as countless publications have tried to assign to it a hidden, esoteric meaning (see e.g. Schwaller de Lubicz 1998). Indeed we do not know the details of the ceremonies that took place there, nor can we imagine the feelings of the devout people who left inscribed votive shards along the route of the statues’ procession and saw in the solemn march of the gods the reassuring regularity of the life cycle. After the entrance of the statues into the recesses of the temple, the common people waited for the king to report on the success of those ceremonies, and in this sense the secret of the temple really had been kept. Nonetheless, we can see once again that ancient Egyptian architecture and symbolism is far from being hidden or esoteric. So although the fine details of the theological framework were perhaps only vouchsafed to the elite, the feeling of the sacred space, and the way in which buildings were oriented and ceremonial acts were engineered in order to maintain Maat on the land of the two lands, was also here apparent – familiar – to everyone.

8.5 My face is yours

On Hatshepsut’s death, the legitimate heir Thutmose III ascended to the throne, and the memory of the Pharaoh Queen swiftly began to fade. Thutmose, in fact, launched a wide-ranging programme aimed at dwarfing the achievements of his predecessor, to the extent, later in his reign, of even obliterating her name from many monuments. The king also added a small temple up against that of the queen at Deir el Bahri, probably with the objective of replacing it as receiver of the statues of the Karnak gods during the “Festival of the Valley” (Chapter 10).

The king’s intentions are particularly clear precisely at Karnak, where – among other building projects – he ordered the erection of enormous obelisks (one can be found today in Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome) aimed at outdoing Hatshepsut’s efforts. To the south-east end of the temple axis, the king also ordered the construction of a somewhat unusual structure, the Akhmenu. The Akhmenu was a large, rectangular temple intended to celebrate the king’s ancestors and military campaigns; the roof was supported by two rows of columns shaped like the poles of a portable tent. From the architectural point of view, the transverse position of the longest side of the Akhmenu in relation to the Karnak temple axis (Photo 8.5) clearly shows the intent of obstructing the view of Hatshepsut’s buildings along the direction of “her father” rising into the south-east.

Photo 8.5. Karnak. The temple axis at sunset.

Veneration of the rising sun at the winter solstice was, however, reaffirmed also in the Akhmenu. In fact, a stairway from the north-east corner of the pillared hall leads up to a room (“high room of the sun”, as Gerald Hawkings called it), which is clearly a solar shrine. This elevated building is provided with a window opening to the south-east and a huge altar in the form of four-hetep signs not unlike that of the Niuserra sun temple at Abu Gorab, built about a millennium earlier.

Successors to Thutmose III were Amenhotep II and his son Thutmose IV. With these two kings, we see a renewed focus on Giza that is somewhat difficult to account for. No traces of cult activities pertaining to the Middle Kingdom have in fact been recovered there, the only fact worthy of note being the presence of stone reliefs which came from Giza pyramid complexes reused in the pyramids of Lisht. Some evidence of activity can be found at the beginning of the New Kingdom, but it is usually attributed to the fact that the area of Giza was used as a hunting reserve (Hassan Reference Hassan1953). The Pharaoh who really turned the situation around was Amenhotep II, who ordered the construction of a new temple there after more than one thousand years. This temple (perhaps built on an earlier Thutmose I chapel) is the small building which is visible directly above the north side of the Sphinx pit. The building houses a huge stela, dedicated by the king to the god Hor-em-akhet, meaning “Horus in the horizon”. The temple is obviously oriented to directly face the Sphinx from the front and Khufu’s pyramid from the rear, and there can scarcely be any doubt that it is dedicated to the Sphinx herself, so in a sense it is incorrect to call it a “temple” since the god’s statue is definitively not inside it. On the other hand, there is some ambiguity as to the interpretation of the god “Horus in the horizon” identified with the statue (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1994a). It is usually believed that the original meaning of the Sphinx was lost at that time and that the similarity – about which we know a considerable amount – between the setting sun between the two pyramids and the hieroglyph Akhet (with the Sphinx perched in the middle) had perhaps been “noticed” or “picked up” (Photo 8.6). I have always been loath to accept this interpretation, as it smacks too much of a sort of fetishistic worship of a statue, which appears quite antithetical to the Egyptian mentality. So, I tend to think that the Akhet in question here – where the “Horus” is in – is nothing but Khufu’s. Unfortunately, it is impossible to ascertain whether the denomination “Horus in the Horizon” for the Sphinx can be traced back to the Old Kingdom; in turn, the name of the Great Pyramid, the Horizon of Khufu, was known in the New Kingdom, but perhaps referred to the whole Giza necropolis. As it happens, however, Amenhotep II is also credited with the revival of the cult of Khnum, the god protector of Khufu, since he decreed the erection of a pair of obelisks devoted “to his father”, Khnum-Ra, at the main temple of this god in Elephantine (one of the two obelisks is today at the University of Durham).

Photo 8.6. Giza. The sun sets behind the Sphinx, with the two main pyramids forming a giant Akhet sign, as seen from the Sphinx terrace on a summer evening. The Sphinx really becomes “Horus in the horizon” in these moments.

Another point that is difficult to clarify is the reason behind the decision by Amenhotep II to build this temple. This decision is probably connected with the famous “dream stela” which was erected by his son Thutmose IV between the paws of the Sphinx. The inscription on the stela recounts that, when the king was still a young prince, he fell asleep in the shadow of the statue at midday. In a dream, Hor-em-akhet prophesied that he would gain the future kingship. The god, however, requested that his precinct be cleared up and restored. Although the stela bears the date of year 1 of Thutmose IV, it is hard to believe that Amenhotep II erected the temple without clearing the pit, so perhaps the works were really carried out by the prince on his father’s behalf. If this was the case, the initial repairs in the masonry of the Sphinx body should also have been executed, although the megalithic temple in front of the Sphinx was left completely forgotten and buried in the sand.

Clearly, the restoration of the Sphinx suited the propaganda aims of Thutmose IV. Accordingly, one might suspect that the restoration made by the king involved not only the body but also the face. As we have seen in Chapter 3, the question “who is the Sphinx?” is highly debated, and I have already agreed with Stadelmann’s (Reference Stadelmann1985) identification of the statue with Khufu as being the most likely. However, there is a passage of the prophecy of the Dream Stela where the Sphinx says (Breasted Reference Breasted1906): “My face is yours, my desire is toward you. You shall be to me a protector.”

The wording “my face is yours” is usually interpreted as “my face is towards you”, but I would suggest that the hypothesis of a resculpting of the head by an artist serving Thutmose IV is a possibility which might just be worth exploring further.