Introduction: Women, Commerce, and Capitalism

White women were heavily involved in a range of commercial activities in plantation Jamaica. Recent scholarship has overturned past analyses of white women’s lives in colonial British America, which either ignored the role of white women in commerce in plantation societies in favor of exploring inheritance practices and sexuality or denied that white women had any involvement at all in slavery and asserted that they, at least in Jamaica, were essentially irrelevant to economic life.Footnote 1 This recent scholarship comprehensively shows that white women in British American plantation societies were extremely active participants in a rich and varied commercial culture, shaping that culture in numerous ways, especially with respect to the consumption of goods. White women’s economic involvement was circumscribed: they were not involved to any significant extent in the transatlantic slave trade, or in large-scale moneylending to plantations, or even in much of plantation agriculture. Nevertheless, their active participation in local trade in British manufactures means that an understanding of commerce in Britain’s most valuable eighteenth-century American colony is incomplete without an analysis of white women’s debt and credit networks. These networks demonstrate that white women played a significant role in facilitating the Jamaican economy, especially in urban areas outside the plantation sector.Footnote 2

The amount of credit white women extended to a variety of debtors was substantial by British-Atlantic standards and became more so over time. It developed into a system that helped lubricate local trade, aiding the distribution and consumption of British manufactures.Footnote 3 It functioned alongside multiracial female-centered systems of trade, sometimes described as “higglering,” that have been a significant part of Jamaica’s informal economy from the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 4 In this article, we examine networks of female credit in Kingston, Jamaica, between 1735 and 1779, using social network analysis (SNA) in order to provide fresh empirical data on female involvement in commerce in the Atlantic world. We use SNA because it allows us to infer precise qualitative relationships from quantitative data; this means that for the first time, the power and influence of white women within Kingston’s credit networks is measured—which is not possible using traditional methodologies. By using centrality and closeness measures we show a female-centered credit system, one mostly directed toward augmenting the credit opportunities of white women rather than white men. Given that consumption was often, if not always, driven by white women, we argue that these female-centered credit networks were a vital part of Jamaica’s capitalist economy.

This article demonstrates how female-centered credit networks emerged and functioned in Kingston in the eighteenth century. In doing so, it makes four historiographical contributions. First, using SNA allows us, for the first time, to accurately measure the importance of predominantly white women in Jamaica’s credit networks and to provide close analysis of how those female credit networks operated in practice. Using measures of closeness, average centrality, and density, we demonstrate that white women were important conduits of information within a dynamic credit system. They also acted as bridges, that is, actors who link different networks together, as well as being linked to larger male-centered transatlantic networks—this added to their influence, despite their relatively low numbers.

Second, it confirms that an older literature that saw white women as irrelevant to the Jamaican economy was misplaced.Footnote 5 The British West Indian colonies were more than “armed camps of aggressive men, or machines for the making of fortunes.”Footnote 6 Indeed, it has been argued that white women in Jamaica performed a wide variety of roles, including importing goods and retail services.Footnote 7 More recently, Christine Walker has shown that white women were not marginal players in colonial slavery, but through their roles as merchants, shopkeepers, tavern keepers, moneylenders, and occasionally planters were strong supporters of Jamaican colonialism and were themselves an integral part of an “aggressively profit-orientated” capitalist society.Footnote 8

Third, we see white women at the center—not the periphery—of a developing consumer economy in the Atlantic World.Footnote 9 White women were central to consumption rather than production both in Britain and in Jamaica. British women bought tropical products such as cotton clothing, items associated with the tea ceremony, and luxury items in general, all of which helped to shape consumer markets in the industrious revolution of eighteenth-century Britain.Footnote 10 Female tastes, for example, often determined what sort of cotton products should be produced.Footnote 11 White women in Kingston played an equally important part in shaping Jamaican consumption patterns as consumers, and importantly, as we demonstrate here, provided and accessed credit in order to finance that consumption.

Fourth, by looking at change over time, we examine how white women’s commercial activities and their success in inserting themselves into a dynamic urban Jamaican economy fluctuated according to larger economic cycles. White women were particularly affected by the frequent wars that disrupted Caribbean trade and that had a disproportionate effect on lesser traders who “fell harder” than transatlantic merchants.Footnote 12 Lesser traders were a group in which white women were overwhelmingly represented. Nevertheless, the overall trend was that white women became more important over time within credit networks, notwithstanding their greater susceptibility to being harmed by disruptions of trade caused by war and other economic shocks. We therefore demonstrate that white women were important and proactive participants in Jamaica’s high-consumption capitalist economy. This article briefly outlines the place of white women in Jamaican society, before discussing the sources and methodology used for this research. The main section then analyses our findings decade by decade, with the last section providing a summary of our conclusions.

The Female Economy in Kingston

White women were implicated strongly in slavery, the major institution in colonial Jamaican life, and not just in the plantations but in Kingston, where enslaved people made up 60 percent of the population. Walker has made very clear the extent of economic activities of white women, which included considerable exploitation of Black women, either as enslavers or as competitors to free women of color. White women may have been more marginal to the Jamaican economy than white men, but racial hierarchies were much more significant than gender in creating social and economic divisions, and white women profited from such divisions. As Serena Zabin argues, ‘the remarkable openness of the Atlantic markets to people of all ranks was in part the result of the very hierarchical structures that produced it.”Footnote 13 As our analysis illustrates, white men were increasingly prepared to lend to and borrow from white women, while white women developed credit networks with other women (both white and occasionally of color)—all of which reinforced tendencies toward white solidarity in societies where the majority of the population was Black but the majority of wealth holding was white.

Trade and commerce were variegated sectors in Kingston, but what differentiated the trading and credit networks of white women from transatlantic merchants on the one hand and enslaved women on the other was scale rather than nature. As Amanda Vickery has shown for eighteenth-century England, shopping and small-scale trade was not especially gendered, even if women were “principally identified with spending.”Footnote 14 Certainly, elite white men in Jamaica, as in England, were more likely to purchase luxury goods such as mahogany furniture and new carriages. They joined with white men in self-fashioning an expansive consumer culture in Jamaica, one that was fueled by differential access to credit.Footnote 15 Moreover, in offering credit to other white women, and occasionally to women of color, white female creditors assisted in this flow of credit, which in turn aided that consumption. As white women were important in basic provisioning for the household, this access to credit was important.Footnote 16

Indeed, in Kingston, there were many white women who were part of these credit networks. Compared with Jamaica as a whole, Kingston was a place relatively receptive to the presence of white women. According to a census taken in 1731, 516 white women and 607 white men lived in Kingston. The number of effective female-headed households in Kingston was probably greater than one-quarter, as perhaps 15 percent of Kingston’s male inhabitants depended on the sea and were often absent from the island. Therefore, despite the relative absence of white women on the island as a whole, Kingston’s female-headed households were much more in line with port cities elsewhere in the Atlantic world.Footnote 17 Indeed, women, both white and of color, owned 28.9 percent of all properties taxed in Kingston in 1753.Footnote 18 Thus, far from being a place simply of masculine colonialism, “local circumstances made it all but impossible, and certainly undesirable, for Kingston traders to exclude white women from mercantile activities.”Footnote 19 Furthermore, around one in two free women of color lived in the town, becoming an increasingly visible part of Kingston’s mercantile community over the course of the eighteenth century.Footnote 20

Kingston was also highly distinctive in that it was not a marrying place. Marriages that occurred seldom lasted long and did not produce many surviving children. Furthermore, widowed white women seldom remarried. Rates of illegitimacy for white children, at 25 percent, were of a different order compared with rates of illegitimacy in England and Wales, which were generally around 1 to 2 percent.Footnote 21 There were also sound economic reasons for white women not to (re)marry. By being legally single, or feme sole, unmarried white women were unconstrained by law and custom from entering into business or holding and hiring out enslaved people, as was the case for married white women, who were termed feme covert. Indeed, as Walker argues, Jamaica’s lax attitudes toward sexual activities was an essential component of economic success, notably for entrepreneurial female businesswomen focusing “on service and trade.”Footnote 22

White Jamaican women as a group were wealthy compared with their counterparts in North America and Britain. Their median wealth was £285, and their mean wealth £803, in inventoried estates made between 1674 and 1770.Footnote 23 That was considerably more than the £42 possessed on average by the average person in England/Wales and the northern colonies of British North America, and the £60 of people in the thirteen colonies that became the United States.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, white women’s wealth accounted for only 12 percent of total inventoried wealth between 1674 and 1784. The average personal property of white women was only 38–42 percent the value of that of an average white male between 1725 and 1784. Yet the total wealth held by white women in inventories was substantial, as befitted a very rich colony. It amounted to £870,100 in 1193 inventories made between 1674 and 1784, or 4.6 percent of the total wealth held in inventories over this period. A considerable amount of this wealth—£495,383 or 56.9 percent—was in the form of debts owed to white women by others. It means that the average amount of debt held by white women was £415.24, although the median amount of debt held was much lower than the mean, with a majority of white women holding no debt and credit being concentrated in the 20 percent of white women who listed debts in their inventories.Footnote 25

White women’s credit networks were nevertheless small in terms of value and number compared with the credit networks operated by Kingston’s transatlantic merchants, who lent considerable amounts of money. For example, co-partners, Edward Foord and Samuel Delpratt, in Kingston, and Richard Clark, in Montego Bay, died in 1777, 1784, and 1777, respectively, with loans outstanding worth £373,026, lent to 351 people. Thus, just one major firm of transatlantic merchants had a debt portfolio that was 75.3 percent of the total amount of debt held in all female inventories. Foord, Delpratt, and Clark confined 84.7 percent of their loans to people borrowing more than £1000 and 61.7 percent to individuals who borrowed more than £10,000.Footnote 26 They were not averse to lending to white women—their second-largest debt went to Sarah Gale, the proprietor of a large sugar estate in Clarendon Parish—but the great majority of their lending was made to men, notably the owners of sugar estates.Footnote 27

White women’s overall presence in the credit market was therefore relatively limited compared with that of men, and the amount they borrowed was not great—there were 135 female debtors (white and of color) from our sample of 1526 debtors, borrowing £1,275 out of total amounts lent out of £170,180. Nevertheless, white female traders played an important role in accelerating demand for British manufactures, because they had access to credit to buy such goods, stock their shops with tantalizing displays, and provide credit to cash-poor consumers. As Walker notes, “as family members, friends, neighbours, and business owners, Jamaican-based women acted as moneylenders, creating intimate webs of credit and debt that greased the wheel of the colonial economic economy.”Footnote 28 This credit available to white female traders facilitated a lively retail trade in British and American goods and moneylending. White women’s relative economic marginality did not stop them from playing an important role in the economic life of Kingston. White women in Jamaica were able to profit more than white women in other British colonies from the institution of slavery, in part due to their vigorous employment of access to credit.Footnote 29 That connection to slavery and credit can be ascertained through an examination of the extensive details on credit noted in Jamaican probate inventories.Footnote 30

Probate Inventories and Social Network Analysis

Probate inventories are not unproblematic sources. They only record personalty, or movable property, which in Jamaica included enslaved people; real estate, including both land and buildings, was excluded.Footnote 31 Legislation passed in Jamaica in 1711, making probate inventories mandatory to clear probate, was a vital part of the protection of property and aided the reassurance of creditors.Footnote 32 Indeed, all the evidence suggests that white Jamaicans treated making probate inventories very seriously, with appraisers dedicating considerable time and effort to creating them.Footnote 33 The high mortality rate in Jamaica worked against the biases often apparent in samples of probate inventories made in England, where inventoried people were usually older, wealthier, and more exclusively male than the general population, thus distorting wealth patterns.Footnote 34 Furthermore, as Christer Petley notes, appraisers tended to be wealthier than those being appraised, had to be literate, and needed to have a good grasp of what the deceased had owned, as well as arithmetical and accounting skills and a working knowledge of local prices.Footnote 35

It is likely, however, that in Jamaica, as in England, and as consumer goods proliferated, appraisers simply summarized the deceased person’s goods as opposed to listing them separately. They might also have categorized them differently by gender, the result of a subjective and reflective process.Footnote 36 Significantly, this categorization was often reflected in the amalgamation of the debtors of white women, meaning that the number of debtors, and often even the amounts that were owed to creditors, were under-recorded. Consequently, inventories were an embodied a set of practices that served specific people within particular moral and political contexts.Footnote 37 Probate inventories therefore have their quirks and biases, but they reveal very well the female credit networks to which SNA can be applied.

SNA has increasingly become a popular tool for analyzing historical networks, particularly eighteenth-century commercial networks in the Atlantic world. This has included the development of Liverpool’s and Bristol’s slave-trading communities, London’s networks with Maryland during a credit crisis, the trading links between Liverpool and New York, trade associations in Liverpool, privateering networks, Bristol’s Nevis connections, and the trade of the East India Company.Footnote 38SNA has also been used to investigate some of Kingston’s slave trade networks. It has not been used so far to investigate white women’s credit networks in Jamaica.Footnote 39

SNA is a methodology derived from the social sciences that employs computational techniques to determine relationships between people in a statistically significant way.Footnote 40 Importantly, it also allows us to quantify a person’s importance within a social network through the use of centrality measures. Within SNA, a social network consists of a finite set or sets of actors and the relationships between them, and applies graph theory to measure these relationships. A graph comprises a set of points (or vertices)—in this case our actors (women and men)—connected to one another via edges (or arcs). Two actors who are next to one another are said to be adjacent. The number of other actors to which any given actor is adjacent is called the degree, and the distance between points is calculated by the number of edges in the path between those actors. The degree, or centrality measure, allows us to measure the relationships between these actors, and thereby their power and influence within the network. The presence of this relational information is a critical and defining feature of a network. Four measures are commonly used: out centrality, which measures the expansiveness, or how many people any particular actor has access to within the network; in centrality, which measures how many actors have access to that same actor; betweenness centrality, which identifies potential points of control within a network; and closeness centrality, which measures how close an actor is to others in the network and therefore their relative access to information. Those closer to other actors may also be less reliant on other actors and therefore more independent.Footnote 41

Closeness and betweenness are usually expressed as being between zero and one, where zero is the least connected and one is the best connected. We use closeness in this article. We do this because due to the ego-centric nature of the probate inventories as a source, most of the subnetworks are “star” networks based around the decedent. In and out centrality measures are therefore mostly the same as the number of debtors, and the betweenness is often zero, and not helpful for our analysis. We do, however, use average centrality (a combination of in and out centrality) as a measure of the average number of contacts an actor possesses, and density to see how well interconnected the overall network is. A density of 1 indicates a network in which every actor is connected to every other actor, and a density of 0 indicates a network that is completely atomized.Footnote 42

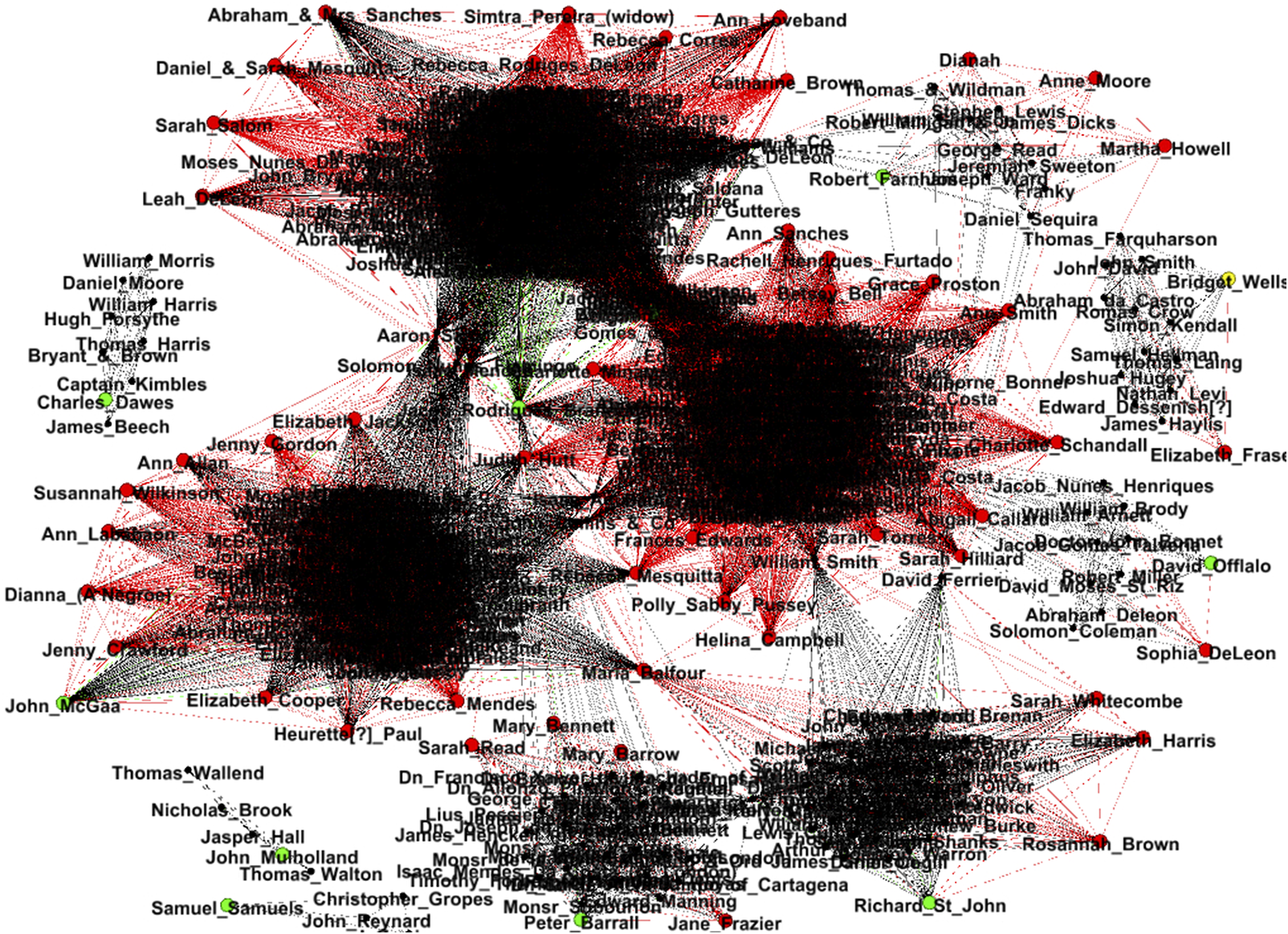

To examine white women’s roles within the credit networks in Kingston, we use Gephi, a commonly used program.Footnote 43 We chose sample years at approximately five-year intervals over the period 1735 to 1779 (1735,1739,1744,1749,1755,1759,1765,1769,1775, and 1779). This choice was partly due to the availability of sources, to ensure a long run of years that included peace- and wartime, and to make the sample manageable. This included all women with probate inventories in these years, a total of forty-three women, of whom thirteen had debtors recorded. Of these women, only three were women of color and were creditors only in the 1760s.Footnote 44 We also included fifty-six probate inventories of white men in the sample years listed as merchants or shopkeepers. These were chosen because they were the most likely to be involved in networks of commercial credit. These sample years have been grouped into decades to make the data and visualization manageable and to demonstrate change over time. We chose the Fruchterman-Rheingold force-directed layout, which draws those actors with the best or most connections to the middle of the graph (those with the least edges between points), while those less well connected are pushed toward the edges of the graph. It is important to note, however, that, where possible, women’s nodes have been “pulled out” of position to make them visible for the purposes of visualization.

Using this methodology, we demonstrate that white women, and some women of color, were an integral part of Kingston’s eighteenth-century credit networks, including regional and transatlantic credit networks. They were, thereby, a vital part of the wider capitalist economy of the Atlantic world. Women, both white and of color, accounted for only 8.8 percent of all debtors, and white women 3.8 percent of the value of all creditors in our sample, but nevertheless they participated in many of the networks of Kingston’s elite male merchants and planters in the area. Moreover, even if they were not a dominant presence in such networks and suffered disproportionately from economic shocks, they often had a relatively high closeness, or access to information, and were occasionally important bridges or connectors within networks.Footnote 45 They were particularly important in extending credit to other white women; they used all forms of financial paper; and they accessed the courts to enforce debts due to them. In doing so, these white women were important in providing distribution services as retailers to the non-elite in Kingston, and therefore played a significant and proactive role in facilitating a high-consumption economy in Jamaica.

Women in Kingston’s Eighteenth-Century Credit Networks, 1730s–1770s

White women were already well integrated into Kingston’s credit networks by the 1730s. Figure 1 shows white women as clearly visible in all the main networks. Female creditors have been colored in yellow, female debtors in red, male creditors in green, and male debtors in black.Footnote 46 White women were only absent on the peripheral networks of John Riviere, Mathew Andrews (both top right), and William Collins (center bottom).Footnote 47 Figure 1 is based on nine male and one female decedents. The men, all of whom were merchants, had 224 debtors, of which 11(4.9 percent) were white women, while the sole female creditor, Dorothy Matson (bottom right), had 79 debtors, of whom 28 (35 percent) were white women. Of a total of 303 debtors then, 39, or 13 percent were white women. Given that the average degree of this network (number of contacts) in the 1730s was 96, Matson, with 79 debtors was somewhat below the average. However, she was also part of a relatively dense network at 0.318. The three most well connected people in this network were men: Jacob Stoaks, John Hynes, and Alexander Henderson all had a closeness of 0.7189 (center top right). This is because they were all bridges between the two networks of Dorothy Matson and Henry Lloyd (0.7171). Dorothy Matson had a closeness of 0.4699. She therefore did not have as good access to information as these men. However, she did have more access to information than all the men in William Brown’s network, all of whom had a closeness of 0.3528, so she was therefore in a good position to access information within the network.

Figure 1. Kingston’s credit networks in the 1730s.Yellow, female creditors; red, female debtors, green, male creditors; black, male debtors.

Hanna Sharpe was the only female debtor of Richard Moore (center bottom), with a book debt of £7.97, but like many others in Richard Moore’s network, she still had a closeness of 0.4745, which was higher than that of Dorothy Matson.Footnote 48 Henry Lloyd (center top) extended credit via book debt of small amounts to Flora Plynth and Rosalinda De Vandelier, while Susanah Rose owed a substantial sum of £203.91.Footnote 49 However, Flora, Rosalinda, and Susanna Rose all had a closeness of 0.6071, which was the same as elite planter, Richard Elletson, and higher than Susanna Elletson and William Perrin, both of whom had a closeness of 0.4699. These women were therefore fairly well connected. William Brown (left), was more likely to extend credit to women.Footnote 50 Eight women owed him small book debts between £0.46 and £12.90, including Mary Braxton and Elizabeth Smith. Brown, Mary and Elizabeth all had a closeness of 0.3528.

Dorothy Matson was the only female creditor in the 1730s, but she lent to many people through book debts, invariably for relatively small amounts.Footnote 51 Her good connections meant that her debtors included elite white women such as Susanna, the wife of Richard Elletson, who was the fourth largest slave owner in St. Andrews in 1754, with 215 enslaved people, and the owner of 530 acres of land.Footnote 52 Other debtors included the planter William Perrin, who owned 368 acres of land in St. Andrews on which he worked 124 enslaved people.Footnote 53 Dorothy also had four bonds due to her, worth a total of £382.25 and several orders and notes totaling £225.29. Matson therefore extended credit to both men and women but more often to women, and sometimes for significant amounts.

In the 1740s, Kingston’s credit networks contracted and were less interconnected overall than in the 1730s. This is highlighted by the network density of only 0.14, down from 0.318 in the 1730s. The average degree for the whole network was only 13.55, whereas in the 1730s it had been 95.75. Not only was the overall network smaller and less dense or interconnected, but white women seem to have suffered relatively more than men. There were far fewer women, and they were not as visible in as many networks as they had been in the previous decade. This contraction was due to the War of Jenkins’ Ear (Guerra del Asiento) of 1739 to 1748.Footnote 54 White female traders were less able to withstand economic shocks or credit contractions, because access to credit and capital was always more circumscribed for white women, a trend that was exacerbated in periods of commercial stress.Footnote 55 Furthermore, with the onset of war, the Spanish Asiento was suspended, and so (legal) trade with the Spanish colonies, in which some white women were engaged, closed.Footnote 56 In 1744 and 1745, one in five ships entering Jamaica came from Spanish America. In 1746, the percentage of ships arriving from Spanish America had declined precipitously to just 8percent.Footnote 57 Figure 2 is derived from the inventories of eight white men and three white women. The men had a total of seventy-four debtors, of which only three (4 percent) were white women. The four female decedents had a total of four debtors listed, although as these were not listed separately, it is likely that the number of debtors to white female creditors are greater than represented in the inventories.

Figure 2. Kingston’s credit networks in the 1740s. Yellow, female creditors; red, female debtors, green, male creditors; black, male debtors.

Indeed, during the 1740s, white women were present in the networks of only two white men. Mrs Jane was the sole female debtor of shopkeeper Nathan Cohen (top left), with a book debt of £3.93.Footnote 58 Eliza Sanderson owed merchant George Spencer (center right) £4.29, while Mary Morgan owed him £5.47 on a note.Footnote 59 These networks had a closeness of 1, but their small and isolated nature means that this does not tell us much. While these amounts are small, it shows that white women could access credit on book debt and use financial instruments, even if the postwar economy meant that white women were less able to do so. Four white women were creditors. Phyllis Bravatt, Elizabeth Johnson (both top right), Elizabeth Clough (bottom left), and Elizabeth Lintor (bottom right). Phyllis only had one unnamed debtor listed for the small sum of £5. Elizabeth Clough’s assessor did not bother to list the names and amounts of her debtors, although they were notes of some kind—so she may have been a moneylender, possibly to other white women. Elizabeth Lintor’s assessor also failed to separately list her various debts, totaling £19. Thus, we do not know the true measure of the closeness, average degree centrality, or the extent of Elizabeth Clough’s and Elizabeth Lintor’s debtors. Elizabeth Johnson had only two debtors—although these were the relatively wealthy women of color Susanna and Mary Augier—who jointly owed her £399.05. This debt was the outcome of a case in Chancery in which Elizabeth was a joint complainant with her husband Thomas. Thus, not only did Elizabeth Johnson lend out large amounts of money to women, she and Eliza Sanderson and Elizabeth Clough provided book credit, used financial instruments, and accessed the court system to secure debts.

Kingston’s commercial credit networks expanded in the 1750s, as peace returned to the island before the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in 1756. Trade with Spanish America resumed, and the Jamaican plantation economy boomed.Footnote 60 White women took advantage of this expansion. Figure 3 highlights the credit networks for the 1750s, derived from the inventories of eighteen white men and three white women. The white men, all merchants, had a total of 268 debtors, of which 17 (6.3 percent) were white women—a noticeable increase from white men’s debt networks of the 1730s and 1740s. The four white female decedents had a total of only four debtors listed between them. Jane Harpur’s book debts, however, were not listed separately, so again, we do not see the full extent of white women’s credit extension. Credit networks increased in number in this decade compared with the 1740s but were still smaller by 50 percent than the sizes of networks in the 1730s. There were also several small, isolated networks with a relatively low network density of 0.134. The average degree of the whole network had increased to 38.48, though again this was still less than in the 1730s.

Figure 3. Kingston’s credit networks in the 1750s.Yellow, female creditors; red, female debtors, green, male creditors; black, male debtors.

The people best connected in credit networks were, as usual, white men. John Gent and Samuel Adams had a closeness of 0.6528, and Thomas Thorowgood and Phillip Pinnock of 0.6155. This close connectedness was because these men were bridges between two networks and were involved in larger networks. Nevertheless, several women also had relatively high closeness scores. White female debtors were in five of the white male networks and were especially concentrated in four of them. William Rutherford (center right) extended book credit to one white woman, Jean Gilbert, who owed him £5.40 (both 0.5174).Footnote 61 Humphrey Morley (top left), extended credit to two white women.Footnote 62Mrs Sperring and Mrs Taylor, owed him money “on order” of £8.26 and £2.93, respectively (all 0.4232). Charity Collins, a pen-keeper, and Mary Carter each owed Thomas Thorowgood (center) book debts of £1.79 and £3.51 respectively and had a closeness of 0.4150.Footnote 63 Thorowgood, because he was also a debtor of William Lloyd, had a closeness of 0.6155.Footnote 64 William Lloyd (center) (0.6108) was just as likely as Thorowgood to extend credit to white women through book debts—often for small amounts suggesting household expenditure.Footnote 65 Several of the white women in Lloyd’s network also had a relatively high closeness of 0.5460.Footnote 66 The remaining white women were the book debtors of William Ewins (center left), who all had a closeness of 0.4702.Footnote 67 While they may have been debtors rather than creditors, they still had relatively high access to information for decision making, and potentially, influence.

While the list of debtors for the three female decedents in the 1750s is disappointingly small, the lists are still informative. Jane Harpur (bottom left) had outstanding book debts, both good and bad, of £142.86 from a thriving retail business, but unfortunately the assessor did not list them separately, so her closeness of 1 is meaningless, because we cannot recreate her networks.Footnote 68 It also means we cannot compare her to the average centrality of 38.48 for the whole network to assess her connectivity. Other white women, such as Catherine Stephenson (bottom center), were moneylenders. She was owed £250 on bond. These included two bonds from Edward Tittles, a small slaveholder from St. Andrew Parish, worth £150.Footnote 69 Similarly, Henry Livingston owed her £71.43 on bond for the principal of his debt.Footnote 70 White women were clearly part of Jamaica’s regional financial networks, including loaning money to men.

In the 1760s, this pattern of a few small, isolated networks continued, and the density of 0.134 remained the same as in the 1750s. Women, white and free women of color, were a smaller absolute number and percentage of the credit networks in the 1760s than during the 1750s, probably because they suffered more than men did from credit downturns during the Seven Years’ War and then prospered as good times returned to the island after 1763. Economic shocks such as war tended to “cleanse” trading communities of lesser traders that did not have “the resources to sustain their trade”; this pattern intensified as traders retrenched their networks to those they trusted the most.Footnote 71 Although the number of women involved in these credit networks declined in the 1760s, different opportunities opened up for those active during the Seven Years’ War. They may have been helped by the increase in naval men posted to the island during the war to whom we might expect women, Black and white, to have provided services such as the provision of food and washing clothes.Footnote 72

Figure 4 is derived from nine male and four female probate inventories, three of which were for women of color. The male inventories, of all which were for merchants, contained 305 debtors, of which 12, or 3.8 percent, were female. The female inventories had only twelve debtors, of which only one was listed as female (8.33 percent). Overall, 317 debtors are listed, 49 more than in the 1750s, of which 13(4.1 percent) were women (both white and of color), which was a lower percentage and absolute number than in the 1750s. The book debts of Elizabeth McAulay, which are grouped together and do not note individual debtors, might have included women, further confirming an underrepresentation of white female involvement in the credit networks. Given that McAulay’s total debts were assessed at £600, her lists of debtors would have been revealing.

Figure 4. Kingston’s credit networks in the 1760s.Yellow, female creditors; red, female debtors, green, male creditors; black, male debtors.

Again, the most well-connected actors in 1760 credit networks were white men: Snow & Gerrard with a closeness of 0.7513, closely followed by Edward East, Neil Campbell, and Angus Campbell at 0.7375. The most well-connected white woman was Dorothy Thompson with a closeness of 0.5890, who was one of James Love’s (center left) many debtors. John Crow (center left) did not lend to white women, nor did Daniel Alvarenga (bottom right). Alvarenga’s network, however, was interconnected with that of Isaac Rodrigues Nunes, who extended credit of £30.44 to Judith Hutt.Footnote 73 These interconnections meant that Judith Hutt had a closeness of 0.4390, the same as merchant Thomas Southworth and planter Phillip Pinnock. Daniel Alvarenga has one of the few meaningful closeness measures of 1, because he was connected not only to the network of James Love, in which Dorothy Thompson and Mary Corbett were debtors, but to Alexander Henry (center top) and thereby Helen Sinclair (creditor) and Sarah East, Susan Stewart, and Frances Read (all debtors).Other white men extended credit to women via book debts or notes, often for small amounts.Footnote 74 This suggests that these debts were either for household expenses or small purchases for onward retail. Either way, these credit networks helped facilitate Jamaica’s high-consumption economy.

Some white women had more substantial debts. These included Susan Stewart (0.5053) (center top) who owed Alexander Henry (also 0.5053).Footnote 75 More important, however, was Helen Sinclair, despite her owing Alexander Henry a book debt of just £3.70. She was the only white female in this decade who was a bridge between networks, and who was listed as both a debtor and a creditor.Footnote 76 She had a closeness of 0.5118 and an average centrality degree of 212, which was much higher than the average degree centrality for the whole network of 71.02. Her inventory tells us that she was the enslaver of twenty people—nineteen men and one woman—and that she gained an income from hiring them out.Footnote 77 Frances Read (0.4349), the only woman listed as one of Sinclair’s debtors, owed her two debts for “negroe hire,” one for £31.94 and another for £21.43. The Kingston merchant firm of Beans & Cuthbert (0.5118) also owed Sinclair for the hire of enslaved people to the value of £30.84. Thomas Southworth, a slave-trading merchant, owed her £49.02 for the hire of an enslaved man sent to Havana, and Thomas Burrows owed her £35.71 for the rent of two sailmakers.Footnote 78 The well-connected partnership of Snow & Gerrard owed her £14.09 for interest due on land and “Negroes” sold to them. Sinclair also let Beans & Cuthbert transfer another debt for the purchase of “Yellow Belly” into an amount via “prize money,” thereby involving herself in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War. Helen Sinclair was also an urban landholder, because Beans & Cuthbert owed her £100 for stores leased to them. She rented out land to Daniel Gully, who owed her for a year’s rent of land, £157.10 for “Negroes,” and a balance due on a note of £103.92. In addition, Sinclair accepted an order from Jarvey& White drawn on Lewis Cuthbert. Despite the challenging wider postwar economy, Helen Sinclair was well integrated into the credit networks of this period, and importantly, more so as a creditor to white men and white women than as a debtor. She may also have been influential as a bridge between networks. Sinclair’s involvement in the Kingston economy in this way therefore suggests that white men, as well as white women, saw her as an active and reliable business associate. Certainly, she was engaged in a wide variety of economic activities, including renting out enslaved people and landholding.

Although most white women inventoried during the eighteenth century were legally feme sole, and thus could operate as independent traders, they still faced relatively limited access to capital and credit (a situation exacerbated for women of color), which meant that they were less able to withstand the vacillations of the war economy. Therefore, the free women of color, Ann Jennison (bottom left), Sukey& Co. (center right), and Mary Augier (top right), in this analysis, are especially significant for showing how such women could overcome the disadvantages of their race as well as their gender.Footnote 79 Sukey, in particular, was well connected, with a closeness of 0.4714. Similarly, many white women were well integrated in terms of being bridges within the network, such as Judith Hutt, but were also well connected via planters and merchants to the Kingston, regional, and transatlantic economy. White women were fewer in number and did not lend to as many people as did white men, but those that were active were well connected, with access to information at the same measure as many men. Importantly, they acted as potentially influential bridges between networks and were adept in the use of various financial instruments.

White women became more noticeably part of Kingston’s credit networks during the 1770s than they had been previously, an important point given that white women usually suffered during times of economic downturn such as the American War of Independence and the Atlantic-wide credit crisis of 1772.Footnote 80 Figure 5 is derived from the inventories of twelve white men and one white woman. Overall, there were 62 female debtors (white and of color) out of a total of 560, nearly double that of the 1730s, and four times the number in the 1760s. White women are also present in all the networks except those three that were peripheral. Figure 5 also shows that the network had fewer isolated networks, which is reflected in the higher network density of 0.219.

Figure 5. Kingston’s credit networks in the 1770s.Yellow, female creditors; red, female debtors, green, male creditors; black, male debtors.

Some white men extended credit to white women, but only for small amounts. These included shopkeeper David Offlalo (center far right), who extended book credit to one white woman, Sophia DeLeon.Footnote 81 Robert Farnham (top right) extended credit to three white women. These may have been for small amounts, but the white women still had a closeness of 0.3896.Footnote 82 Peter Barrall (center bottom) also extended small amounts of book debt to four white women, yet all the white women had a relatively high closeness of 0.4574.Footnote 83 Richard St John (bottom right) also extended credit to four white women, all on book debt. Again, these were for small amounts, possibly for onward retail. One white woman, Maria Balfour, owed St John £3.57, but she also owed money to John McGaa, the merchant second most likely to extend credit to white women, with nineteen female debtors.Footnote 84 Importantly therefore, Maria was a bridge between networks. Her closeness of 0.5847 is higher than that of the other white women in St John’s network, including St John himself (0.4522) and that of John McGaa (0.5289).Footnote 85 Maria also owed McGaa a considerable sum, £83.57.Footnote 86 The remaining white women owed McGaa small sums, including Judith Hutt, who owed McGaa just £1.11. However, Judith also owed Jacob Rodrigues Brandon a small book debt of £1.43.Footnote 87 As a bridge between two networks she had a high closeness of 0.6628. It is also notable that she accessed credit with more than one merchant. Furthermore, Judith Hutt was also present as a debtor in the 1760s, so she is one of the few women, like Dorothy Matson and Mary Augier, who had a long-term presence within Kingston’s credit networks.

Benjamin Pereira’s (top right) credit network is noteworthy, as he was a large-scale moneylender willing to lend sizable sums to white women. This shows that on occasion white women could access the extensive credit available from the portfolios of men at the highest levels of wealth in Kingston.Footnote 88 Eleven white women owed Pereira book debts, including Simtra Pereira and Rebecca Correa (both 0.5560), both Jewish widows. He also had one debt secured by mortgage of £186.57 due from Abraham and Mrs Sanches, and another for £74.67 due from Isaac and Rachel Mendes. It is unusual to see both husband and wife named on debts due to feme covert. It may well be that Jewish women were able to access credit due to the particular social and economic cultures of Jewish people within Jamaica, which were oriented toward dealing with their compatriots or co-religionists. Like the similar networks of the Scots, these orientations rendered them, to their critics, as unduly clannish.Footnote 89

There was only one female creditor from our sample of the 1770s, Bridget Wells (center right).Footnote 90 Her network had a closeness of 1, but was contained within a small and isolated network, from which we cannot infer much information of value. What is important about her, however, is that she mostly extended credit to men. Her only white female debtor was Elizabeth Fraser, who owed Bridget £470.07, on several bonds written in April 1770 and in July and October 1779. Another large debtor was Samuel Hellman, who owed Wells £400 on a Bill of Exchange, apparently drawn on the British government. Simon Kendall was the only person whose debt was itemized by goods—for sundry apparel and bed linen—but still secured on a note for £111.43. Clearly, Bridget was a moneylender who was able to (supposedly) secure her debts through bonds. However, Bridget had a problem, because the majority of her debts were considered doubtful, and some were of long date. These included Romas Crow who owed her £13.58 on a variety of notes and orders from 1768. Therefore, while she was able to get her debts secured by financial instruments, she was not always able to enforce payment. Bad debts were a continuing and pressing problem in Jamaica. Between 1722 and 1791, 80,021 executions for £22,563,786 were lodged in the provost marshal’s office in Spanishtown for judgments in the Jamaican Supreme Court.Footnote 91 We do not know how many of these debts were owed by white women, but the large sums involved suggest that there would have been court actions taken by white women.

Women, both white and of color, were connected to wider local, regional, and transatlantic credit networks as debtors, even more so than as creditors during the 1770s. Elite men such as Philip Pinnock (0.5560), George Paplay& Co.(0.4574), John Coppell (0.5289), Thomas and Wheeler Fearon (both 0.5560), and Thomas Hibbert (0.5289) held considerable wealth as Kingston merchants and prominent Jamaican politicians. They had women in their credit networks. These men operated on a different scale of moneylending to that of women. Kingston merchant and esquire, Peter Barrall, for example, extended credit to the Kingston merchant, St. Andrew planter, and Jamaican politician, Edward Manning (0.4574), and his merchant house, Manning & Ord (0.4574), for £205.05 and £2637.76 respectively. These elite men were not necessarily better connected within the credit networks analyzed here, which are orientated around the interactions of lesser traders, including white women. The skewed closeness of 1 in small networks aside, many white women were relatively well connected in the 1770s. It was scale rather than nature that differentiated the credit networks of white female Kingston traders from mighty transatlantic merchants. White women with high degrees of closeness during the 1770s included Abigail Pereira (0.7107), Rebecca Mesquita (center) (0.6628), in addition to the aforementioned Maria Balfour and Judith Hutt. At the other end of the scale were Sophia De Leon (bottom right) (0.3737), Anne Moore, Martha Howell, and Dianna—a woman of color—(all top right) (all at 0.3996 or low levels of closeness). Despite the traumas of an Atlantic-wide credit crisis and the start of the American War of Independence, the number of women, Black and white, in Kingston’s credit networks increased in the 1770s. Many were well connected, able to access and provide various forms of credit and to use a wide range of sophisticated credit instruments.

Conclusions: Women, Credit and Capitalism

This article makes four historiographical contributions. First, we use SNA to visualize white women’s involvement in Kingston’s eighteenth-century commercial credit, showing the roles of white women, and occasionally women of color, in these networks. By providing a quantitative analysis of white women’s place within Kingston’s mid-eighteenth-century credit networks, we add an important new element to the work of Walker, Erin Trahey, and Sweeney. We have achieved this by using closeness and centrality measures to show the extent to which white women, and some women of color, were connected and had access to information, even when gender constructs held white women back from full participation in the Kingston economy. While white women never had the highest closeness in any decade analyzed here, they often had relatively high closeness and average centrality. In many cases, these measures of connectedness were even higher than those some elite men. Furthermore, white women were often important bridges and conduits of information between networks, making them potentially more influential.

Second, our evidence shows that white women were particularly important within the domestic retail sector and that they had an orientation toward assisting other women, white and of color, with their credit needs. We cannot therefore, as in the past, conclude that male advantage relegated white women to commercial irrelevance. Indeed, the evidence we have presented here represents a minimum of white female involvement in Kingston credit networks. White women’s debtors were underrepresented in the probate inventories, probably due to appraisers’ perception that white men, rather than white women, were economic actors. The large number of debtors in Dorothy Matson’s inventory is testament to how many female debtors may be missing in the inventories of white women whose debtors were not so carefully noted, such as those of Elizabeth McAulay. It is worth noting however, that gender was not the only issue of importance. Most women of color did not have access to the credit networks enjoyed by wealthy free women of color like Susanna and Mary Augier. They thus found it difficult to get the capital or credit needed for entrepreneurialism. The Augier sisters, as free women of color, were therefore exceptional rather than representative in how they were able to be connected to networks that provided them with suitable credit. By contrast, Jewish women such as Simtra Pereira and Rebecca Correa were apparently able to use their ethno-religious networks to access credit successfully.

Third, white women were important in the provision of credit to the local and regional economy, which facilitated Jamaica’s high-consumption economy, especially at the lower echelons of society. We recognize that white women had access to only part of the Kingston economy, rather than to the more credit-intensive and valuable transatlantic trade, especially in enslaved people, and to Jamaica’s vibrant plantation sector. White women nevertheless accessed both local and regional credit networks, used book credit and sophisticated credit instruments to do so, and accessed the local court systems to enforce those debts.

Fourth, white women were, in common with other lesser traders, particularly susceptible to economic cycles. They were more likely to suffer from credit contractions and other adverse trading conditions than were white men, because most had small capital reserves.Footnote 92White men had on average four to five times as much cash reserves and much greater amounts of debts lent out.Footnote 93 As was the case in other Atlantic trading communities in wartime, Kingston’s commercial networks contracted, and many lesser traders were forced out of the trading community. Thomas Doerflinger suggests that French colonial commerce had been reduced by as much as 81 percent by the end of the Seven Years’ War, and while British colonial commerce did not decline quite so much and quickly returned to prewar patterns once the Seven Years’ War was completed, the contraction of trade in the war itself was substantial.

It was even more substantial during the American War of Independence, when trade with North America declined dramatically. Women in Kingston, white and of color, who were involved in retail trading and in providing services to local populations of residents and visitors were especially likely to suffer in such a dramatic commercial downturn.Footnote 94 Yet it is also clear that white women in particular were able to take advantage of economic upturns when they occurred. Indeed, over this whole period, white women benefited from the rising wealth of the island, with white female wealth increasing by 84 percent between the 1720s and the early 1780s.

Kingston’s white women suffered in common with the lesser traders, and disproportionately so. This trend was particularly true in the 1740s, when Kingston’s networks contracted. The women were able, however, to take advantage of the revival of trade in the 1750s, 1760s, and 1770s, despite the travails of the Seven Years’ War and the onset of the American War of Independence. While white women were not a large proportion of total debtors and creditors in Kingston, they were still able to access credit from elite merchants, thereby integrating themselves into transatlantic credit networks. In turn, they were particularly important in extending credit to other white women and thereby facilitating Jamaica’s high-consumption economy. The fact that white women were integral to Kingston’s local credit networks shows that they played a significant role in Kingston’s economy, and especially in the lower echelons of white society, as evidenced in the many instances of small debts owed by and to them, through a mixture of book debt and a wide range of credit instruments. They therefore played an important and active role in Jamaica’s high-consumption economy. Indeed, this quantitative analysis of Kingston’s credit networks demonstrates that despite gender constructs and patriarchy, white women were active and capable protagonists in the economy of eighteenth-century Jamaica.