Introduction

Neurocognition, cognitive reserve, and social cognition have all been related to functioning in first-episode psychosis (FEP). Specifically, numerous studies have found that cognitive deficits are present early in psychosis, manifesting in multiple cognitive domains including working memory, executive function, attention, processing speed, and/or learning and memory (Zabala et al., Reference Zabala, Rapado, Arango, Robles, de la Serna González, Rodríguez-Sanchez, Andrés, Mayoral and Bombín2010; González-Ortega et al., Reference González-Ortega, de Los Mozos, Echeburúa, Mezo, Besga, Ruiz de Azúa, González-Pinto, Gutierrez, Zorrilla and González-Pinto2013; Bora and Murray, Reference Bora and Murray2014). These deficits have been related to poorer psychosocial functioning (Leeson et al., Reference Leeson, Sharma, Harrison, Ron, Barnes and Joyce2011; González-Ortega et al., Reference González-Ortega, de Los Mozos, Echeburúa, Mezo, Besga, Ruiz de Azúa, González-Pinto, Gutierrez, Zorrilla and González-Pinto2013; Green and Harvey, Reference Green and Harvey2014; Torgalsbøen et al., Reference Torgalsbøen, Mohn, Czajkowski and Rund2015), but some studies have not found this association (Kravariti et al., Reference Kravariti, Morris, Rabe-Hesketh, Murray and Frangou2003; Stirling et al., Reference Stirling, White, Lewis, Hopkins, Tantam, Huddy and Montague2003). Overall, there is a lack of consensus on how cognitive functioning changes over the course of the disease and its relation to functional outcome.

Cognitive reserve has been associated with the functional course of FEP, patients with a higher cognitive reserve showing a better outcome (Leeson et al., Reference Leeson, Sharma, Harrison, Ron, Barnes and Joyce2011; Amoretti et al., Reference Amoretti, Bernardo, Bonnin, Bioque, Cabrera, Mezquida, Solé, Vieta and Torrent2016). Cognitive reserve has been defined as the ability of a brain to cope with brain pathology and thereby minimize symptoms (Stern, Reference Stern2002) and variables used as measures of cognitive reserve include premorbid IQ, educational level, and occupational attainment (Anaya et al., Reference Anaya, Torrent, Caballero, Vieta, Bonnin and Ayuso-Mateos2016).

Social cognition has also been associated with functional outcome. Indeed, it has been suggested that social cognition is a better predictor of functional outcome of FEP patients than neurocognition (Fett et al., Reference Fett, Viechtbauer, Dominguez, Penn, van Os and Krabbendam2011; Ohmuro et al., Reference Ohmuro, Katsura, Obara, Kikuchi, Sakuma, Iizuka, Hamaie, Ito, Matsuoka and Matsumoto2016). Social cognition includes theory of mind, social perception, social knowledge, attributional biases, and emotion processing, areas that are affected in FEP patients (Horan et al., Reference Horan, Green, DeGroot, Fiske, Hellemann, Kee, Kern, Lee, Sergi, Subotnik, Sugar, Ventura and Nuechterlein2012; Bora and Pantelis, Reference Bora and Pantelis2013; Bliksted et al., Reference Bliksted, Fagerlund, Weed, Frith and Videbech2014). It has also been associated with neurocognition and premorbid IQ (Bliksted et al., Reference Bliksted, Fagerlund, Weed, Frith and Videbech2014) and there is evidence of a relationship between social cognition and neurocognition and that this may have a negative influence on functional outcome of FEP (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder2011).

Although cognitive reserve, neurocognitive functioning, social cognition, and functional outcome are probably related, the direction of their associations is not clear (Fett et al., Reference Fett, Viechtbauer, Dominguez, Penn, van Os and Krabbendam2011; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder2011; Pinkham and Harvey, Reference Pinkham and Harvey2012; Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, van Haren, van Baal, Kahn and Hulshoff Pol2013; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Chang, Chen, Lin, Tsai and Lane2013). In a systematic review, Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder2011) found that social cognition acts as a mediator between neurocognition and functioning in schizophrenia (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder2011), though in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis this was not observed (Barbato et al., Reference Barbato, Liu, Penn, Keefe, Perkins, Woods and Addington2013).

Therefore, for predicting the outcome of FEP patients after the onset of the disease, it is important to explore the potential mediating role of social cognition in the association between neurocognition and functioning. In this context, our study had the following objectives: (1) to assess changes from baseline in cognitive functioning, social cognition, and functioning at 2 years of follow-up in FEP patients; (2) to analyze the influence of cognitive reserve and cognitive domains on social cognition and functioning at baseline and at 2 years of follow-up; (3) to analyze the influence of social cognition on functioning; and (4) to analyze the influence of social cognition as a mediator between cognitive reserve and cognitive domains on functioning.

Method

Subjects

This work was part of the ‘Phenotype-genotype and environmental interaction. Application of a predictive model in first psychotic episodes’ study (PEPs study, from its acronym in Spanish) (Bernardo et al., Reference Bernardo, Bioque, Parellada, Saiz-Ruiz, Cuesta, Llerena, Sanjuán, Castro-Fornieles, Arango and Cabrera2013).

Patients were aged between 18 and 35 years old at the time of first evaluation and were required to have fluent Spanish and to give written informed consent. If patients were not capable of giving consent or minors, a legally authorized representative was asked to provide consent on their behalf. Moreover, it was required that patients had a less than 12-month history of psychotic symptoms.

Exclusion criteria for patients were: mental retardation according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) (including not only an IQ below 70, as determined using the test described in Table 1, but also poor functioning), history of head trauma with the loss of consciousness, and organic illness affecting mental health. The study was approved by the clinical research ethics committees of all participating centers in the PEPs Group.

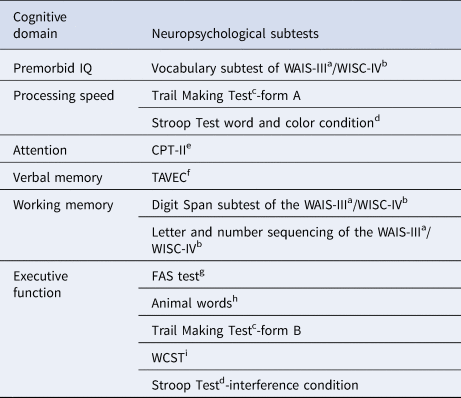

Table 1. Description of test and measures used for cognitive domain summary scores

a Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (WAIS-III) (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997).

b Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (WISC-IV) (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2003).

c Trail Making Test (Reitan and Wolfson, Reference Reitan and Wolfson1985).

d Stroop Test (Golden, Reference Golden1978).

e Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (CPT-II) (Conners, Reference Conners2004).

f Test de Aprendizaje Verbal España-Complutense (TAVEC) (Benedet and Alejandre, Reference Benedet and Alejandre1998).

g Controlled Oral Word Association Test (FAS test) (Loonstra et al., Reference Loonstra, Tarlow and Sellers2001).

h Animal words (Peña-Casanova, Reference Peña-Casanova1990).

i Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay and Curtiss1993).

Initially, 335 FEP patients were included in the study. Of these, 53 patients were excluded for not having seven or more neuropsychological tests completed. Thus, the final study sample consisted of 282 patients.

Data collection

Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected at baseline and at 2 years, while cognitive assessment was performed at 2 months of follow-up, in order to ensure the psychopathological stability of patients, and at 2 years of follow-up. If patients were actively psychotic at the time of the 2-year follow-up, we delayed the assessment until their condition was stabilized. The assessment protocol was fully described by Bernardo et al. (Reference Bernardo, Bioque, Parellada, Saiz-Ruiz, Cuesta, Llerena, Sanjuán, Castro-Fornieles, Arango and Cabrera2013).

Adult patients were diagnosed with FEP using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer and Gibbon1997), while the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for school-age children-Present and Lifetime version (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, Flynn, Moreci, Williamson and Ryan1997) was used for those under 18 years old, following DSM-IV criteria.

Functional impairment of patients was evaluated using the functional assessment short test (FAST) (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Sánchez-Moreno, Martínez-Aran, Salamero, Torrent, Reinares, Comes, Colom, Van Riel, Ayuso-Mateos, Kapczinski and Vieta2007), for which high scores suggest poorer functioning. The FAST is a measure of functioning that is valid, reliable, and sensitive to change and has been validated and widely used in bipolar disorder (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Reinares, Amann, Popovic, Franco, Comes, Torrent, Bonnín, Solé, Valentí, Salamero, Kapczinski and Vieta2011; Bonnín et al., Reference Bonnín, Martínez-Arán, Reinares, Valentí, Solé, Jiménez, Montejo, Vieta and Rosa2018; Vieta et al., Reference Vieta, Berk, Schulze, Carvalho, Suppes, Calabrese, Gao, Miskowiak and Grande2018), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Rotger et al., Reference Rotger, Richarte, Nogueira, Corrales, Bosch, Vidal, Marfil, Valero, Vieta, Goikolea, Torres, Rosa, Mur, Casas and Ramos-Quiroga2014), and FEP (González-Ortega et al., Reference González-Ortega, Rosa, Alberich, Barbeito, Vega, Echeburúa, Vieta and González-Pinto2010).

The substance use was assessed using the European Adaptation of a Multidimensional Assessment Instrument for Drug and Alcohol Dependence (EuropASI) and patients were categorized according to EuropASI scores into four groups (no use, use, abuse, and dependence) (Kokkevi and Hartgers, Reference Kokkevi and Hartgers1995).

The following cognitive domains are assessed: processing speed, attention, verbal memory, working memory executive function, and premorbid IQ. The tests and measures used for domain summary scores are described by Bernardo et al. (Reference Bernardo, Bioque, Parellada, Saiz-Ruiz, Cuesta, Llerena, Sanjuán, Castro-Fornieles, Arango and Cabrera2013) and Cuesta et al. (Reference Cuesta, Sánchez-Torres, Cabrera, Bioque, Merchán-Naranjo, Corripio, González-Pinto, Lobo, Bombín, de la Serna, Sanjuan, Parellada, Saiz-Ruiz and Bernardo2015) (Table 1).

Estimated premorbid IQ, educational level, and occupational attainment were used as measures of cognitive reserve (Anaya et al., Reference Anaya, Torrent, Caballero, Vieta, Bonnin and Ayuso-Mateos2016). IQ was evaluated with the Vocabulary subtest of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997) or Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2003), while educational level and occupational attainment variables were assessed with the Hollingshead–Redlich Scale (Hollingshead and Redlich, Reference Hollingshead and Redlich1958).

Social cognition was assessed with understanding emotions, managing emotions, and total emotional intelligence scores of the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, which rate the helpfulness of certain moods and assess the effectiveness of strategies to manage emotions (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Salovey and Caruso2009).

Statistical analyses

Demographic variables are described with means (±s.d.) and percentages. t Tests for paired samples were used to analyze differences in cognitive performance and functioning of patients between baseline and 2 years of follow-up.

To assess the cognitive domains, we calculated the average of the z-scores of the neuropsychological variables which correspond to each domain (Table 1). As the scores of the Trail Making Test (Reitan and Wolfson, Reference Reitan and Wolfson1985) are inverse, they were multiplied by −1 to facilitate the interpretation (higher scores indicating better performance). The same approach was taken for cognitive reserve, that is, averages of the z-scores were calculated for estimated premorbid IQ, educational level, and occupational attainment.

To explore whether social cognition mediates the influence of cognitive reserve and cognitive domains on functioning, a three-step procedure was used (Frazier et al., Reference Frazier, Tix and Barron2004). Figure 1 represents the hypothesized mediation model. Firstly, we analyzed the relationship between cognitive reserve and cognitive domains with social cognition with a linear regression (path a). Secondly, linear regression models were built to explore the association of cognitive reserve and cognitive domains (independent variables) with functioning (dependent variable) (path c). All models were adjusted for potential confounders (namely, age, sex, civil status, socioeconomic level, educational level, diagnosis, substance use, and family history) with a stepwise procedure which only included variables in the final model if they produced a significant change in the coefficient of the independent variable. Finally, social cognition was included as a mediator in the multiple regressions found to be significant in the second step (paths b and c´). If the relation of social cognition with functioning was significant and the path c association became non-significant, conditions for mediation would be satisfied, this suggesting that social cognition is a mediating variable. The statistical significance of the mediation was examined by bootstrap analysis (95% bootstrapped confidence interval (CI)).

Fig. 1. Hypothesized mediation model.

Data analyses were conducted with Stata 12.1. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05, except for the analyses of the cognition domains for which we applied the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. For these, the level of significance was set at p < 0.01, calculated by dividing 0.05 by five, the number of cognitive domains.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics, cognitive, and functional course of the sample

Baseline characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2. The total sample comprised 192 men (68.1%) with a mean age of 23.64 (5.93) years. Of these, 123 (43.6%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 59 (20.9%) had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The drug most frequently used was tobacco (66.4%) and most patients were single (86.9%).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the sample

During 2 years of follow-up, all the cognitive domain scores improved significantly, except working memory and executive function. Social cognition, cognitive reserve, and functioning were also significantly better at 2 years (Table 3).

Table 3. Means of cognition and FAST during follow-up (n = 186)

p value <0.05 except for the cognitive domains for which the Bonferroni correction was applied (p < 0.01). Bold values represent the significant values.

Correlations between cognitive and functional variables are presented in a Supplementary Table.

Relationship between cognitive reserve, social cognition, general cognition, and functioning

Table 4 reports the results of the analysis of the basic path models at both baseline and 2 years. At baseline, cognitive reserve was significantly associated with social cognition. Regarding baseline cognitive domain scores, after the Bonferroni correction, only processing speed and verbal memory showed a significant association with social cognition at baseline (path a). Social cognition was not significantly associated with functioning at baseline (path b). Neither cognitive reserve nor the cognitive domains were related to functioning at baseline (path c).

Table 4. Statistical analyses of the paths a and b

p value <0.05 except for the cognitive domains for which the Bonferroni correction was applied (p < 0.01). Bold values represent the significant values.

At 2 years of follow-up, in addition to baseline cognitive reserve and verbal memory, baseline executive function was also associated with social cognition at 2 years, while processing speed became non-significant at this time point (path a). Furthermore, social cognition at both baseline and 2 years was significantly associated with functioning at the end of the follow-up (path b). Cognitive reserve was significantly related to functioning at 2 years. Regarding baseline cognitive domain scores, after applying the Bonferroni correction, only attention and verbal memory were significantly related to functioning at 2 years (path c).

The influence of social cognition as a mediator between cognitive reserve and cognitive domains on functioning

At baseline, as neither cognitive reserve nor cognitive domain scores were related to functioning (path c), the conditions for mediation were not satisfied.

At 2 years of follow-up, after including social cognition at baseline in the final model, all significant relations of baseline cognitive domains and cognitive reserve with FAST at 2 years remained significant. Further, their coefficients increased after the inclusion of social cognition, and therefore, baseline social cognition did not mediate in these relations. Nevertheless, relevant results were obtained after including social cognition at 2 years in the model. Social cognition at 2 years was a significant mediator between cognitive reserve and functioning at 2 years (Fig. 2). In fact, its association with functioning was significant (path b), while the relation between cognitive reserve and functioning became non-significant (path c´). These findings suggest a significant full mediation of social cognition, it mediating 20.8% of the effect (95% bootstrapped CI −10.215 to −0.337).

Fig. 2. Mediation of social cognition between cognitive reserve and functioning at 2 years.

With respect to cognitive domains, after including social cognition at 2 years in the regression model between baseline attention and functioning at 2 years, social cognition had a significant association with functioning (path b) and attention remained significant, its coefficient increasing (b = 3.445, p = 0.006). Therefore, the conditions for the mediation of social cognition were not satisfied. Regarding baseline verbal memory, this domain lost its significant association with functioning at 2 years when including social cognition at 2 years in the model (path c´), while the latter had a significant association with functioning (path b) (Fig. 3). Thus, social cognition at 2 years appears to be a significant full mediator, it mediating 25.2% of the effect (95% bootstrapped CI −4.731 to −0.605).

Fig. 3. Mediation of social cognition between verbal memory and functioning at 2 years.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that social cognition acted as a mediator between cognitive reserve and functioning at 2 years of follow-up. Likewise, social cognition was a mediator between verbal memory and functional outcome. These findings suggest that social cognition is involved and indeed plays a crucial role in the functional outcome of FEP patients. There is little previous research on this mediation, although in a systematic review Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder2011) also found that social cognition mediated the relationship between neurocognition and functioning in schizophrenia. Our findings are from a sample of patients with FEP and take into account the role of cognitive reserve. Moreover, our study has a longitudinal design.

There is extensive evidence of social cognitive deficits in FEP (Horan et al., Reference Horan, Green, DeGroot, Fiske, Hellemann, Kee, Kern, Lee, Sergi, Subotnik, Sugar, Ventura and Nuechterlein2012; Bora and Pantelis, Reference Bora and Pantelis2013; Bliksted et al., Reference Bliksted, Fagerlund, Weed, Frith and Videbech2014; Langdon et al., Reference Langdon, Still, Connors, Ward and Catts2014; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Lui, Hung, Wang, Li, Cheung and Chan2015) and related conditions (Lahera et al., Reference Lahera, Herrera, Reinares, Benito, Rullas, González-Cases and Vieta2015; Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Valls, Morilla, Lahera, Martínez-Arán, Vieta and Reinares2017). Impairments in social functioning have been related to deficits in emotion recognition, emotional intelligence/social perception, and social knowledge of FEP patients (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Girard, Christensen and Addington2010), because of their difficulties managing specific situations and predicting social consequences, as well as in recognizing changes in behavioral meaning (Montreuil et al., Reference Montreuil, Bodnar, Bertrand, Malla, Joober and Lepage2010). Moreover, it is considered that deterioration in social cognition has been related to poor functioning, especially poor work and social functioning as well as interpersonal and problem solving skills (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Girard, Christensen and Addington2010; Fett et al., Reference Fett, Viechtbauer, Dominguez, Penn, van Os and Krabbendam2011; Horan et al., Reference Horan, Green, DeGroot, Fiske, Hellemann, Kee, Kern, Lee, Sergi, Subotnik, Sugar, Ventura and Nuechterlein2012).

A second major finding of our study is that social cognition may be a potential marker for predicting the functional outcome of patients. Previous studies have also found that social cognition may be a trait marker of psychosis (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Gokcen, Kayahan and Veznedaroglu2008; Bora and Pantelis, Reference Bora and Pantelis2013). In fact, it has been seen that social cognition could be a better predictor of functional outcome than neurocognition with a significant impact on general functioning of patients (Fett et al., Reference Fett, Viechtbauer, Dominguez, Penn, van Os and Krabbendam2011; Ohmuro et al., Reference Ohmuro, Katsura, Obara, Kikuchi, Sakuma, Iizuka, Hamaie, Ito, Matsuoka and Matsumoto2016). In our sample of FEP patients, although baseline social cognition was related to functioning at 2 years, it was not a mediator between cognition and functional outcome; however, social cognition 2 years later was a significant mediator. This finding is probably related to the state and trait nature of social cognition. Social dysfunction has been described as a state marker related to symptoms of schizophrenia, and some studies suggest that it is not impaired after symptom recovery (Corcoran et al., Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith1995; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Robinson and Birchwood1998). Nonetheless, several studies have demonstrated deficits in social cognition in remitted patients (Herold et al., Reference Herold, Tenyi, Lenard and Trixler2002; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Krabbendam, Jolles and Os2003; Inoue et al., Reference Inoue, Yamada, Hirano, Shinohara, Tamaoki, Iguchi and Tonooka2006). It is possible that patients have social cognition deficits as a trait marker, and in addition, these deficits may worsen with symptoms, indicating that it is both a trait and a state variable. Moreover, social cognitive deficits are already present even in patients at risk of psychosis (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Papas, Bartholomeusz, Allott, Amminger, Nelson, Wood and Yung2012; Ohmuro et al., Reference Ohmuro, Katsura, Obara, Kikuchi, Sakuma, Iizuka, Hamaie, Ito, Matsuoka and Matsumoto2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yi, Li, Cui, Tang, Lu, Xu, Qian, Zhu, Jiang, Chow, Li, Jiang, Xiao and Wang2016) and deficits have even been found in unaffected first-degree relatives (Bora and Pantelis, Reference Bora and Pantelis2013), this highlighting its trait properties.

On the other hand, another relevant finding of our study is that cognitive reserve and neurocognition predicted social cognition, both at baseline and 2 years. Bliksted et al. (Reference Bliksted, Fagerlund, Weed, Frith and Videbech2014) also found a correlation between social cognition and IQ, though they distinguish between a complex version of social cognitive deficits linked with IQ and another version related to simpler forms of social cognition that are independent of IQ. Regarding cognitive domains, processing speed and verbal memory showed a significant association with social cognition at baseline. At 2 years of follow-up, verbal memory and executive function were associated with social cognition. Previous studies have also found that cognitive functioning is related to social cognition. Theory of mind disabilities have been related to general cognitive impairment (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Gokcen, Kayahan and Veznedaroglu2008) and more specifically, Fernandez-Gonzalo et al. (Reference Fernandez-Gonzalo, Pousa, Jodar, Turon, Duño and Palao2013, Reference Fernandez-Gonzalo, Jodar, Pousa, Turon, Garcia, Rambla and Palao2014) showed that executive function was related to theory of mind in FEP patients. Further, Sachs et al. (Reference Sachs, Steger-Wuchse, Kryspin-Exner, Gur and Katschnig2004) found a correlation between emotion discrimination and verbal memory and language processing cognitive domains.

As we hypothesized, at 2 years of follow-up there was an improvement in social cognition, cognitive functioning, and general functioning of patients. There is extensive evidence of the involvement of cognitive impairment in the functional outcome of FEP patients (Lepage et al., Reference Lepage, Bodnar and Bowie2014; Torgalsbøen et al., Reference Torgalsbøen, Mohn, Czajkowski and Rund2015). Neurocognitive deficits have been identified as a core symptom of schizophrenia and may be more related to functional recovery of patients than clinical symptoms (Lepage et al., Reference Lepage, Bodnar and Bowie2014). It has been suggested that cognitive impairment appears soon after or even before the first episode of psychosis (Bora and Murray, Reference Bora and Murray2014), and while some studies argue that there is deterioration in cognitive functions in the follow-up (Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, O'Carroll and McCreadie2006; Arango et al., Reference Arango, Rapado-Castro, Reig, Castro-Fornieles, Gonzalez-Pinto, Otero, Baeza, Moreno, Graell, Janssen, Parellada, Moreno, Bargallo and Desco2012), others postulate an improvement in cognitive function (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Sánchez, Pérez-Iglesias, González-Blanch, Pelayo-Terán, Mata, Martínez, Sánchez-Cubillo, Vázquez-Barquero and Crespo-Facorro2008; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Nieman, Wiltink, Dingemans, van de Fliert, Velthorst and Linszen2010). Our findings suggest that cognitive impairment in FEP is not progressive after the onset of illness, but rather improves in the follow-up, which lends support to the neurodevelopmental model of cognition. Although the effects of treatments were not analyzed in the study, it is possible that treatment effects and/or clinical stabilization contribute to cognitive improvements in FEP. In our sample of FEP patients, cognitive functioning improved significantly at the 2-year follow-up in all cognitive domains, except working memory and executive function. Similarly, Lepage et al. (Reference Lepage, Bodnar and Bowie2014) found that verbal and working memory are the cognitive domains most affected in FEP. This suggests that specific cognitive domains may be more sensitive than others for predicting long-term functional outcome, that is, some may be more impaired and may be more closely related to patient outcome. Specifically, in our FEP sample, verbal memory predicted the functional outcome at the 2-year follow-up. In relation to this, Torgalsbøen et al. (Reference Torgalsbøen, Mohn, Czajkowski and Rund2015) found that attention/vigilance and verbal learning predicted remission at 6 months of follow-up, whereas attention/vigilance and working memory predicted functional outcome.

Cognitive reserve was also associated with functional outcome. This result has also been found in other studies. Specifically, it has been concluded that patients with a better cognitive reserve will have better outcomes in follow-up. Barnett et al. (Reference Barnett, Salmond, Jones and Sahakian2006) concluded that patients with better cognitive reserve could have better reasoning skills and functional capacity to use compensatory forms and inhibit abnormal neural processing, which translates into greater insight and treatment adherence. Other studies also found that cognitive reserve can predict both the risk of illness as symptoms remit and functional improvement (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Salmond, Jones and Sahakian2006; Forcada et al., Reference Forcada, Mur, Mora, Vieta, Bartrés-Faz and Portella2015; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Sanchez-Moreno, Sole, Jimenez, Torrent, Bonnin, Varo, Tabares-Seisdedos, Balanzá-Martínez, Valls, Morilla, Carvalho, Ayuso-Mateos, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2017). Amoretti et al. (Reference Amoretti, Bernardo, Bonnin, Bioque, Cabrera, Mezquida, Solé, Vieta and Torrent2016) have shown that cognitive reserve predicts neuropsychological outcome, negative symptoms, and functioning at 2 years of follow-up, and hence, cognitive reserve can be used as a reliable indicator for the course of FEP patients (Amoretti et al., Reference Amoretti, Cabrera, Torrent, Mezquida, Lobo, González-Pinto, Parellada, Corripio, Vieta, de la Serna, Butjosa, Contreras, Sarró, Penadés, Sánchez-Torres, Cuesta and Bernardo2018).

The findings of our study have important implications for clinical practice. An understanding of the association between neurocognition, cognitive reserve, and functioning and of the mediating role of social cognition is important for predicting the outcome of FEP patients after illness onset. It is essential to consider the relationship between illness outcome in patients and their IQ, both premorbid values and changes therein, to identify the need for a specific treatment to improve the functional outcome of FEP patients. Specially, patients with lower cognitive reserve may be more likely to need functional rehabilitation to help to improve their prognosis. In addition, people with higher cognitive reserve can be oriented to more ‘normal’ work or education. Likewise, it is essential that the treatment of these patients focuses on social cognitive deficits to improve their functional outcome.

This study has some limitations and strengths that should be considered. Our study had a follow-up of 2 years, and a longer follow-up period should be considered in future research. Another limitation is the variability across studies in how IQ is measured. Although we used criteria based on previous studies, there is no specific instrument validated to measure cognitive reserve. Finally, future studies should include a control group. The study also has important strengths. First, the results can be considered generalizable because it is a multicenter study that included a large sample of patients recruited in numerous Spanish psychiatric admission centers for acute psychosis. Second, the wide age range of the patients means that the sample is representative of the target population, with an average age (23.63 ± 5.9 years), lower than that for other studies with large FEP cohorts which did not include child and adolescent patients (OPUS trial: 26.6 ± 6.4; Bertelsen et al., Reference Bertelsen, Jeppesen, Petersen, Thorup, Ø hlenschlaeger, le Quach, Christensen, Krarup, Jørgensen and Nordentoft2008; and EUFEST trial: 26 ± 5.6; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Fleischhacker, Boter, Davidson, Davidson, Vergouwe, Keet, Gheorghe, Rybakowski, Galderisi, Libiger, Hummer, Dollfus, López-Ibor, Hranov, Gaebel, Peuskens, Lindefors, Riecher-Rössler and Grobbee2008). Third, the neuropsychological battery used was extensive and covered the areas proposed by the NIMH-MATRICS consensus (except visual memory) (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Nuechterlein, Green, Baade, Fenton, Gold, Keefe, Mesholam-Gately, Mintz, Seidman, Stover and Marder2008; Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Kern, Baade, Barch, Cohen, Essock, Fenton, Frese, Gold, Goldberg, Heaton, Keefe, Kraemer, Mesholam-Gately, Seidman, Stover, Weinberger, Young, Zalcman and Marder2008; Nuechterlein and Green, Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Rund and Sundet2009).

To conclude, although further studies are required, our findings suggest that cognitive reserve and neurocognition are related to functioning, and social cognition plays a mediating role.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719002794

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the authors of the PEPs group who participated in the development of this manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Carlos III Institute of Health and European Fund for Regional Development (PI08/1213, PI11/01977, PI14/01900, PI08/01026, PI11/02831, PI14/01621, PI08/1161, PI16/00359, PI16/01164, PI18/00805), the Basque Foundation for Health Innovation and Research (BIOEF), the Secretaria d´Universitats I Recerca del Departament d´Economia I Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365), and R&D activities in Biomedicine, Madrid Regional Government and Structural Funds of the European Union (S2017/BMD-3740 (AGES-CM 2-CM)).

Conflict of interest

A González-Pinto has received grants from or served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen-Cilag, Ferrer, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shering-Plough, Solvay, the Spanish Ministries of Science and Innovation (through CIBERSAM) and of Science (through the Carlos III Institute of Health), the Basque Government, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and Wyeth.

C Arango has been a consultant to or has received fees or grants from Abbot, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Caja Navarra, CIBERSAM, the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, the Carlos III Institute of Health, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, the Spanish Ministries of Science and Innovation, of Health, and of Economy and Competitiveness, Mutua Madrileña, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Shire, Takeda, and Schering-Plough.

E Vieta has received grants from or served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Allergan, Angelini, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, the Carlos III Institute of Health, the European Union's 7th Framework Program and Horizon 2020, the Brain and Behaviour Foundation (NARSAD), and the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

R Rodriguez-Jimenez has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: the Carlos III Institute of Health, the Spanish Health Research Fund (FIS), CIBERSAM, Madrid Regional Government (S2010/ BMD-2422 AGES), JanssenCilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, and Takeda

The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.