-

I. [Page 13] Overview 16

-

II. Analysis 19 1. Question 1: which law governs attribution? 19 1.1. Overview 19 1.2. Attribution-related questions governed by international law for purposes other than State responsibility 20 1.3. Attribution-related questions governed by domestic law 22 2. Question 2: which international legal rules? 26 2.1. Overview 26 2.2. Special treaty-based rules of attribution 27 2.3. Special rules of attribution applicable in investment disputes 31 3. Question 3: which phase of the proceedings? 34 3.1. Overview 34 3.2. The determination of the relevant phase 35 3.3. The operation of prima facie tests and the allocation of the burden of proof 37 4. Question 4: what are the main attribution routes under general international law? 40 4.1. Overview 40 4.2. Conduct of organs of the State (Article 4) 41 4.3. Conduct of instrumentalities (Article 5) 49 4.4. Conduct directed or controlled by a State (Article 8) 54 4.5. Conduct acknowledged and adopted by a State (Article 11) 63 4.6. Other attribution routes 67 5. Question 5: analysis of recurrent problems 69 5.1. Overview 69 5.2. Sovereign vs commercial acts 70 5.3. Official capacity vs private acts 73 5.4. Ultra vires action (Article 7) 75 5.5. Attribution of failure to act 77 5.6. Attribution, contracts and umbrella clauses 80

-

III. Concluding observations 86

-

Appendix: List of cases relevant for attribution 88

-

[Page 14] 1. This volume of the ICSID Reports focuses on the broad topic of attribution of conduct – whether action or inaction – to States.Footnote 1 The international legal rules of attribution are both old and new. Old because several authorities on which their formulation or consolidation rests date back to the early twentieth century or even before. But they are also new because, in earnest, their systematisation came much later, mainly in the last quarter of the twentieth century and, above all, in the 1996 and 2001 Draft Articles adopted by the International Law Commission (ILC) on the subject of State responsibility for internationally wrongful acts.Footnote 2

-

2. A growing degree of consolidation is also apparent in the reasoning of international courts and tribunals applying the relevant rules of general international law. This is so not only in cases preceding the 1996 or 2001 ILC draftsFootnote 3 but also in those decided in the years between the two draftsFootnote 4 and shortly after the [Page 15] adoption of the 2001 draft.Footnote 5 The initial lack of consolidation was less a matter of unfamiliarity with the new systematisation than one of lack of an extensive practice by investment tribunals. As an illustration, the tribunal in EnCana v. Ecuador, presided over by the last ILC Rapporteur on State Responsibility, the late Judge James Crawford, decided the matter of attribution without reference to previous investment cases.Footnote 6 Over time, the body of cases grew and, quite naturally, many complex issues emerged and were addressed in the reasoning of tribunals. At present, the case law of investment arbitration tribunals has become a very important vector in the consolidation of the general international law of attribution.

-

3. This preliminary study provides a systematisation of this growing practice relating to the operation of the general international law of attribution. It does so in the light of the 16 cases reported in this volume as well as of a wider body of cases listed in the Appendix. As in previous volumes, the 16 decisions reflect a combination of relevance and editorial considerations. This preliminary study covers what I see as the most salient issues of importance to practitioners, while at the same time emphasising the conceptual problems raised by these issues. Every effort is made for the theoretical and practical analysis to complement each other, as they should. As the late Professor Emmanuel Gaillard once noted, “law is a science of action” (“le droit est une science de l’action”),Footnote 7 and the constant systematisation work on which law partly rests must embody this double imperative.

-

4. After an overview of the main issues arising from the cases reported in this volume (Part I), I analyse five main questions, each with its sub-questions, in the light of both the reported decisions and the wider case law (Part II), before offering some brief concluding remarks (Part III).

I. Overview

-

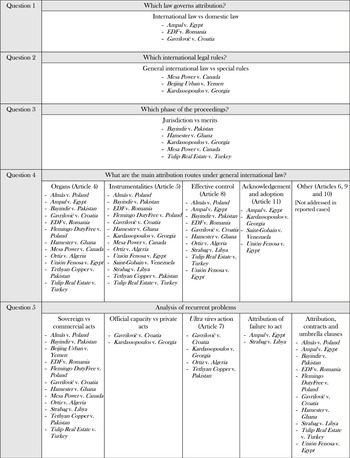

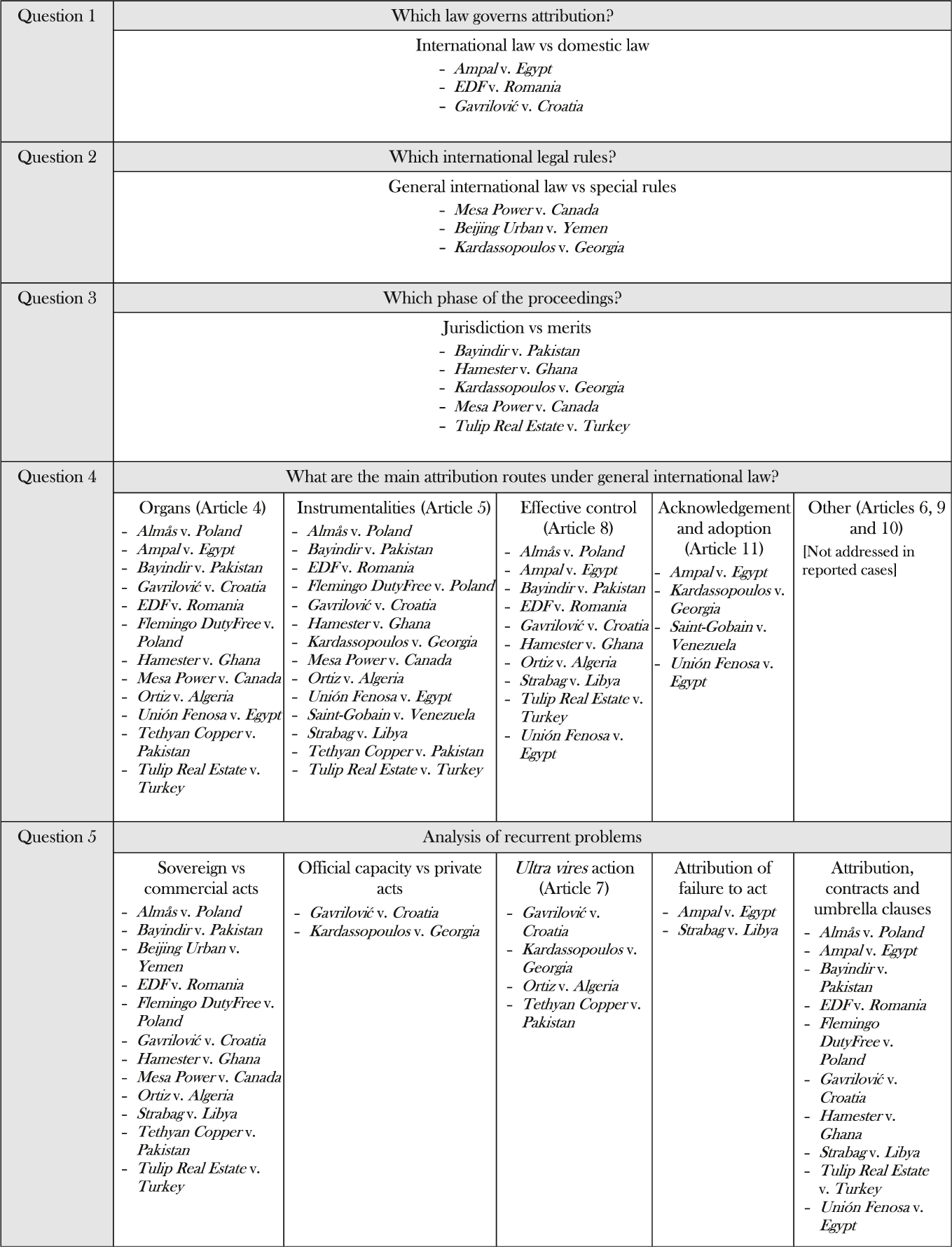

5. This preliminary study places the wide range of issues relating to the rules governing attribution of conduct in the context of five broad questions, which are distinct but related. These questions are selected on the basis of three main considerations. First, taken together, these questions and their answers provide a systematisation of many issues that have emerged in the case law. Thus, they can be seen both as a guide to the broader case law and as an analytical grid to identify and disentangle numerous issues that are sometimes conflated or overlooked. Secondly, these questions can be used to summarise the main tenets arising from the 16 decisions reported in this volume. Figure 1 presents the five questions and locates all the reported decisions in those quadrants where they are most relevant. Thirdly, the same exercise could be conducted for a wider body of case law relating to attribution, much of which is analysed in this study (see Appendix). I have not done so in graphic form, but the structure of Figure 1 underpins the analysis of this wider body of cases in Part II of this study. Before undertaking this analysis, I must elaborate on each of the five questions and their possible answers.

Figure 1. Key questions and recurrent problems in the attribution of conduct to States in investment arbitration

-

6. The first question concerns the law governing matters of attribution of conduct. Whereas some tribunals have proceeded to apply general international law rules, as codified in the ILC Articles, matters of applicable law may be more complex. The rules formulated in Part I, Chapter II of the ILC Articles have a well-defined scope of application. They apply to attribution of conduct to the State as a subject of international law (not domestic law) and only for the purpose of State responsibility (not for other purposes). That, in turn, raises two sets of sub-questions. One concerns the determination of the rules of international law governing attribution-related issues for purposes other than State responsibility. The other concerns the determination of the scope of application of domestic law to a range of attribution-related issues.

-

7. The second question relates to the determination of the relevant rules of international law. One sub-question concerns the operation of special rules of attribution, which may arise from instruments, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),Footnote 8 EU secondary legislation,Footnote 9 the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT)Footnote 10 or other sources. Another sub-question arising in this context concerns the possibility that the general rules of attribution may operate differently in the context of international investment law. This was hinted at by the tribunal in Bayindir v. Pakistan in connection with the rule codified in Article 8 of the ILC [Page 17] Articles.Footnote 11 The growing body of investment decisions on matters of attribution has resulted, indeed, in increasingly detailed inquiries and the development of “tests” for the application of the general rules.

-

[Page 18] 8. The third question concerns the stage of the proceedings in which matters of attribution must be addressed. Although there is no legal requirement preventing attribution from being heard at the jurisdictional stage, and respondent States sometimes raise objections to jurisdiction based on the lack of attribution, the factual dimensions of the question make it more suitable for the merits. When there is no bifurcation between matters of jurisdiction and merits in the proceedings, this factual dimension does not raise any particular difficulties. But in bifurcated proceedings, tribunals may need to either apply a prima facie test to matters of attribution or join the jurisdictional objection based on lack of attribution to the merits. These different options have implications for the length and cost of proceedings.

-

9. The fourth question focuses on the main routes of attribution under general international law. Chapter II of Part I of the ILC Articles provides the basis for analysis. Out of the several rules identified in this document, three of them have been most recurrently used, namely attribution of conduct of organs of the State (Article 4), conduct of instrumentalities of the State (Article 5), and conduct under the direction or control of the State (Article 8). In principle, conduct ultra vires of organs or instrumentalities remains attributable to the State, as stated in Article 7, but there are important distinctions to be made in this regard. These are not the only routes that have been tested in practice. In reported decisions we find reliance on Article 11, which attributes conduct to a State if the latter subsequently adopts the conduct as its own. Beyond the reported decisions, there are some cases which shed light on other attribution routes, including Article 6 (organs placed at the disposal of a State by another State) and Article 10 (insurrectional and other movements). Within the context of the fourth question, clarification of each attribution route can be seen as a sub-question. Yet, staying at this level would not capture a number of specificities that are best discussed separately. That is the purpose of the fifth and final question.

-

10. The fifth question attempts a transversal analysis of five recurrent legal problems arising in the case law. These are by no means the only legal issues that arise, but their general relevance warrants specific discussion. The first sub-question concerns the ever-present issue of the nature – sovereign or commercial – of the relevant acts and the scope of application of this distinction. The second sub-question focuses on a distinct matter, which is the difference between acts performed by an organ or an instrumentality in an official capacity and acts performed in a private capacity. This sub-question raises several complex issues, both definitional (“official capacity”) and normative (how should acts of corruption, which are performed by definition in an official capacity, be characterised). The third sub-question is closely related to the previous one. It concerns the attribution of ultra vires acts. Under Article 7 of the ILC Articles, acts ultra vires of organs and instrumentalities may be attributed to a State under the rules formulated in Articles 4 and 5 if and only if they are performed in an official capacity. For the purpose of Article 4, it does not matter whether the act is of a sovereign or commercial nature, as long as it is performed by an organ acting in an official capacity. By contrast, under Article 5, the commercial nature of the act would be an obstacle to its attribution to the State. The fourth sub-question lies at [Page 19] the intersection between the assessment of attribution and that of breach of a primary norm. It concerns the attribution of failure to act in circumstances where the State is required to act. The fifth and final sub-question concerns a number of issues arising in connection with contracts, including the attribution of the contractual terms themselves, that of conduct interfering with the contractual framework, and the operation of so-called umbrella clauses in this context.

-

11. Figure 1 above summarises all these questions/sub-questions, and the issues for which the decisions reported in this volume are most relevant. In the following paragraphs, I examine each of these questions/sub-questions in the light of the relevant case law. The last section of the study offers a brief overall assessment.

II. Analysis

1. Question 1: which law governs attribution?

1.1. Overview

-

12. Both international law and domestic law are relevant for attribution. Even when it is undisputed that the attribution of a certain conduct is governed by international law, domestic law remains relevant to ascertain whether a certain person or entity is an organ of the StateFootnote 12 or an instrumentality is endowed with governmental authority.Footnote 13 In this scenario, the international legal rules on attribution specifically rely on domestic law. A different matter is, however, to determine whether these rules apply in the first place.

-

13. The Commentary to the ILC Articles specifies the ambit of application of such rules in two main ways.Footnote 14 First, the rules govern attribution of conduct to the State “as a subject of international law” and not as a subject of domestic law.Footnote 15 Second, they only concern attribution for the purpose of determining a State’s responsibility for internationally wrongful acts. These two specifications are more complex than they may appear at first sight. At a basic level, the first one means that in a case against a State before domestic courts for violation of domestic law, the attribution of conduct to the State will not be governed by the rules of attribution in general international law but by domestic law . But the situation becomes more complex when the State is sued for breach of a contract. In principle, such a claim would be against the State as a subject of domestic law, a contractual partner. However, such claims have often been brought before international arbitration tribunals under a composite applicable law, including domestic and international legal aspects. In such cases, the second specification [Page 20] is useful to clarify that the international legal rules on attribution only concern a State’s responsibility for an internationally wrongful act, i.e. the consequences (organised by “secondary rules”, including rules of attribution) under international law of a breach of an international rule of conduct (a “primary rule”).

-

14. The decision of the tribunal in Ampal v. Egypt offers a concise confirmation of this point when it states that “[t]he Tribunal accepts the Respondent’s submission that the rules of attribution only apply to the determination of breaches of international law. They are not applicable to contractual breaches.”Footnote 16 The conceptual distinction between primary rules and secondary rules can be applied both to international and domestic law. The breach of a primary rule of domestic law has the consequences described in the applicable secondary rules of domestic law. Only if the conduct may amount to a breach of a primary rule of international law will the international legal rules on attribution apply, alongside other “secondary rules” of State responsibility for internationally wrongful acts.

-

15. These two specifications, taken together, circumscribe the scope of application of the rules of attribution in general international law in such a way as to exclude two main sets of questions which are governed by other rules: attribution-related questions under international law for purposes other than State responsibility, and attribution-related questions governed by domestic law.

1.2. Attribution-related questions governed by international law for purposes other than State responsibility

-

16. The first set of questions is expressly acknowledged by the Commentary to the ILC Articles by reference to the international legal rules governing the organs which can enter into commitments on behalf of the State without the need to produce full powers (Heads of State or Government and ministers of foreign affairs).Footnote 17 The distinction between the purpose of State responsibility and other purposes under international law (for which the international legal rules of attribution do not apply) was recognised by the tribunal in Gavrilović v. Croatia, in the following terms:

The ILC Articles are the relevant rules on attribution that are widely considered to reflect international law. They concern the responsibility of States for their internationally wrongful acts, given the existence of a primary rule establishing an obligation. These principles of attribution do not operate to attach responsibility for “non-wrongful acts” for which the State is assumed to have knowledge.Footnote 18

In this case, the tribunal reasoned that because there was no conduct constituting a breach of a primary rule of international law, the question of attribution did not arise. To avoid any confusion, attribution is a necessary but not sufficient [Page 21] component of an internationally wrongful act, as characterised by Article 2(a) of the ILC Articles. It is therefore relevant for the assessment of an allegation that a State has breached its international obligations, even if the assessment concludes that there has been no breach.

-

17. The distinction made by the tribunal in Gavrilović v. Croatia served mainly to conclude that the rules of attribution cannot be used “to create primary obligations for a State under a contract”.Footnote 19 An analogy can be made with the example given in the ILC Commentary relating to the rules defining the powers to bind the State. The fact that a person is an organ of the State is clearly not enough for such a person to be entitled, under international law, to conclude a treaty or to bind a State through a unilateral act, unless there are other rules that entitle that person to do so. The rules of attribution are inapplicable in this respect. The same applies to contractual undertakings. The mere fact that a person is (or is employed by) an organ does not mean that s/he is entitled to bind the State contractually – whether the national government, a territorial subdivision, or a public agency – unless there are other rules, here of domestic law, which contemplate such binding conduct. The international legal rules of attribution, including the rule concerning acts ultra vires, simply do not concern this issue.

-

18. There are also other attribution-related questions, governed by international law, where such rules are inoperative, although their treatment in the case law is sometimes confusing. For example, when the jurisdiction of a court or tribunal is limited to complaints or claims brought by entities (physical or legal) other than States, as under Article 34 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)Footnote 20 or Article 25 of the ICSID Convention,Footnote 21 the question may arise as to whether a claimant’s links to a State are such that they preclude its right of action.Footnote 22 This is clearly different from the question of whether a certain conduct is attributable for the purpose of State responsibility. Hence, the international legal rules on attribution are inoperative. The matter is governed by other rules of international law specifically concerning this issue, i.e. Article 34 of the ECHR or Article 25 of the ICSID Convention, for the interpretation of which the international legal rules on attribution may or may not be relevant, but they are not governing. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has developed its own test to determine whether a complainant is a governmental or non-governmental actor for the specific purpose of bringing a complaint.Footnote 23 In the investment context, tribunals have followed different approaches. In some cases, [Page 22] the matter has been addressed under a specific test applicable under the relevant rule (Article 25 of the ICSID Convention).Footnote 24 In others, perhaps due to the framing of the argument by the parties, the question has been incorrectly examined under the international legal rules of attribution, although this is clearly a purpose unrelated to State responsibility.Footnote 25

-

19. A further attribution-related question governed by international law but not by the international legal rules of attribution is the assessment of breach of a primary rule. The ILC Commentary makes this point clearly:

As a normative operation, attribution must be clearly distinguished from the characterization of conduct as internationally wrongful. Its concern is to establish that there is an act of the State for the purposes of responsibility. To show that conduct is attributable to the State says nothing, as such, about the legality or otherwise of that conduct.Footnote 26

In practice, the matter may be confusing because the facts underpinning the inquiry on attribution may be largely the same as those relevant to establish breach of an international obligation. For example, when the claim concerns conduct which is blatantly in breach of international law, its attribution would suffice to trigger responsibility. But, as noted by the commentary, “the two elements are analytically distinct”.Footnote 27 A conduct may be attributable to a State but, after assessment, it may not constitute a breach of a primary rule of international law. The latter assessment is governed by the primary rule.

-

20. So far, I have discussed four attribution-related questions governed by international law but not by the international legal rules of attribution, namely: (i) legal powers to bind the State in certain ways, (ii) the scope of primary norms (entities bound by it), (iii) the right to bring a claim, and (iv) the difference between attribution and responsibility. These are but some examples. As noted earlier, the international legal rules of attribution have a specific ambit of application, beyond which they are inoperative.

1.3. Attribution-related questions governed by domestic law

-

21. Certain attribution-related questions which are beyond the aforementioned ambit are governed by laws other than international law, i.e. domestic law including contractual matters. The decisions in Gavrilović v. Croatia and Ampal v. Egypt can serve again as starting points for the discussion. In Gavrilović, the respondent [Page 23] questioned the legality under domestic law of certain actions taken by its own Bankruptcy Courts. The tribunal, after stating that “the principles of attribution operate in the context of a complaint made against the State by a third party”, reached the conclusion that “[t]he involvement of the host State in this process – for example, through the Bankruptcy Court – is not a matter of attribution because there is no third party seeking to hold the State liable”.Footnote 28 The conclusion is correct but the reason is questionable. Whether or not a third party seeks to hold a State responsible is not determinative. What matters is whether the conduct must be considered State conduct for the purpose of its (in)consistency with a primary rule of international law. Given that the issue in Gavrilović was (in)consistency with domestic law, the rules of attribution were inapplicable.

-

22. The latter reasoning was followed by the tribunal in Ampal v. Egypt with regard to consistency with certain contractual obligations. The tribunal sided with the respondent in its conclusion that “the rules of attribution only apply to the determination of breaches of international law. They are not applicable to contractual breaches.”Footnote 29 Breach of contract is not a matter of State responsibility for internationally wrongful acts. The ILC Articles devote a specific article to the clarification of this point: “[t]he characterization of an act of a State as internationally wrongful is governed by international law. Such characterization is not affected by the characterization of the same act as lawful by internal law.”Footnote 30 A breach of a contract triggers the secondary rules defining the consequences of such breach under the proper law of the contract, whether the domestic law of the host State or a foreign law selected by the parties. Only a breach of a primary rule of international law triggers the rules of State responsibility for internationally wrongful acts. It is, of course, possible that the very facts claimed to be a breach of contract may amount to a breach of international law. This raises the classic issue of the distinction between treaty claims and contract claims.Footnote 31 The tribunal in Ampal recalled specifically its decision on jurisdiction, where the two matters were distinguished:

in order for it to find that there has been a breach of those standards in relation to the Gas Supply Dispute [fair and equitable treatment and unlawful expropriation], it will need to determine as an incidental question whether the Source GSPA [General Sale and Purchase Agreement] was validly terminated. However this does not change the fact that the key issue under the Treaty in respect of a claim for unlawful expropriation or breach of the fair and equitable treatment is whether there has been a loss of property right constituted by the contract or whether legitimate expectations arose under the contract.Footnote 32

Taken together, these two decisions clarify that the rules of attribution in general international law are only applicable to assess the consistency of State conduct with a primary rule of international law, not with one arising from [Page 24] domestic law (e.g. bankruptcy) or a contract (and its proper law). The next step of the analysis concerns the type of questions that fall under the remit of domestic (and contractual) law.

-

23. One important question that arises in practice concerns the extension of contractual obligations undertaken by entities, public or private, which are separate from the State. This may be relevant to determine liability under domestic law but also to assess whether there is an undertaking by the State (the contract) protected by an umbrella clause, i.e. by a primary rule of international law. The basic rule is clear: it is the applicable domestic law that determines who is a party to the contract; the international legal rules of attribution cannot extend a contract to a non-party. As noted in EDF v. Romania, reported in this volume:

[T]he attribution to Respondent of AIBO’s and TAROM’s acts and conduct [both being State-owned entities in the Romanian aviation industry] does not render the State directly bound by the ASRO Contract or the SKY Contract for purposes of the umbrella clause. … Attribution does not change the extent and content of the obligations arising under the ASRO Contract and the SKY Contract, that remain contractual, nor does it make Romania party to such contracts.Footnote 33

-

24. Interference by a State with a contractual relationship between third parties (e.g. a foreign investor and a public entity) may, however, be assessed in the light of the rules of attribution in general international law. For example, the public entity may exercise a contractual right under the direction or control of the host State.Footnote 34 That specific conduct (the exercise of a contractual right) may be attributed to the State under the international rules of attribution and, if it is in breach of a primary rule of international law, it may trigger the responsibility of the State for internationally wrongful acts. But at no point are the contractual obligations between the foreign investor and the entity extended to the State. Any potential breach of contract is merely part of the facts to be assessed when considering whether there has been a breach of an international obligation.

-

25. In this context, one may ask what rules govern whether the contractual obligations undertaken by a separate entity (public or private) can be extended to the State. Whether or not a State has entered into a contract through representatives is a matter of domestic law. The decision on jurisdiction in Khan Resources [Page 25] v. Mongolia offers a good illustration.Footnote 35 The dispute concerned a uranium mining venture in Mongolia. The claims were brought under both a set of contracts and the ECT. The claimants argued inter alia that the contractual obligations were binding on the State because they had been entered into by entities which were State representatives. The respondent objected that Mongolia was not a party to the relevant contract and, as a result, the tribunal lacked personal jurisdiction. The tribunal rejected the objection. In doing so, it made two significant points. First, the tribunal stated that the claimants bore “the burden of proving the facts on which they rel[ied] in support of this proposition [i.e. that the entities party to the relevant contract were representatives of Mongolia]”.Footnote 36 Second, the tribunal stated that “the relationship between a state and its alleged representative must be assessed under the law of this state and in the light of the factual background of this relationship”.Footnote 37 Thereafter, it examined the text of the contract, in the light of a related contract, Mongolian law and the behaviour of the parties, and it found that the State was a party to the contract and therefore the tribunal had personal jurisdiction. At no time did the tribunal feel any need to refer to the international legal rules on attribution.

-

26. The approach followed in Khan Resources v. Mongolia is, in my view, correct. It can be contrasted with the less clear approach followed on this point by the tribunal in Devas v. India, a decision reported in volume 18 of the ICSID Reports.Footnote 38 In this case, the claimants argued that the conduct of a State-owned company, including the entry into a contract with the investor, was attributable to the State on the basis of the concept of agency. This argumentation was problematic because the claimant sought to establish a certain notion of agency in international law by reference to cases where agency had been analysed, as it must be, under domestic law.Footnote 39 The tribunal rightly rejected the existence of such a concept but, debatably, it examined whether the obligations undertaken by the State-owned entity under the contract could be extended to the State as a result of the international legal rules of attribution. On this point, it concluded that:

when entering into the Agreement, [the State-owned entity] was not acting as an organ of the Respondent, whether under the provisions of Articles 4 and 5 of the ILC Articles. The Agreement itself does not constitute an obligation the Respondent has entered into within the meaning of Article 11(4) [the umbrella clause].Footnote 40

[Page 26] This reasoning was possibly influenced by how the parties argued their case, but it is misleading. Whether a contract concluded by a separate State-owned enterprise can be extended to the State is a matter of domestic law. By contrast, whether a State has interfered with the exercise of contractual rights by the State-owned enterprise allegedly in violation of a primary rule of international law is a matter governed by the international rules on attribution. The tribunal reasoned, on this specific point, that the issuance of a force majeure notice by the State-owned enterprise had been conduct under the direction or control of the State (Article 8 of the ILC Articles), hence attributable to it for the purpose of State responsibility.Footnote 41

2. Question 2: which international legal rules?

2.1. Overview

-

27. The international legal rules governing questions of attribution may be derived from general international law, as partly codified by the ILC Articles, but also from the treaties applicable in a specific case. As discussed next, three instruments which have been referred to in the practice of investment tribunals are the NAFTA, EU secondary legislation and the ECT.

-

28. In addition to the application of possible special rules of attribution, another sub-question arising in this context concerns the possibility that there may be specific international legal rules of attribution for investment disputes and their wider relevance for other contexts. The ILC Articles were developed to cover State responsibility for breach of any primary rule of international law, including – but not limited to – investment protection standards.Footnote 42 But investment disputes may present some peculiarities requiring adjustments to at least some of the general rules codified therein. As noted in the introduction, the tribunal in Bayindir v. Pakistan suggested such a possibility in connection with the rule codified in Article 8 of the ILC Articles.Footnote 43 This possibility must be assessed in the broader context of the constant reference to and refinement of the general rules of attribution in the case law of investment arbitration tribunals. On the one hand, constant reference to the general rules is evidence that they are applicable as such to investment disputes. On the other hand, the growing body of investment cases analysing these rules has resulted in increasingly specific jurisprudential tests, which may (or may not) be relevant beyond investment disputes.

-

29. The following paragraphs discuss, first, the sub-question of special treaty-based rules of attribution and, second, the one relating to the possibility of special rules of general international law applicable to investment disputes.

2.2. Special treaty-based rules of attribution

-

30. It is useful to begin the discussion of special treaty-based rules of attribution with the decision in Mesa Power v. Canada, reported in this volume,Footnote 44 because it addresses the two main issues that may arise in this context, namely the framing of the alleged special rule and the interactions between it and the general rules of attribution. The basic context of the attribution issue in this case was the respondent’s argument that the NAFTA contains a special rule of attribution (Article 1503(2)) for State enterprises which makes certain acts of these entities (which could be attributed under general international law) not attributable to the State. Hence the two questions: are the relevant entities “State enterprises” and, if so, what is the operation of Article 1503(2)? The tribunal answered that the entities were indeed State enterprises and that Article 1503(2) was a special rule of attribution under which only certain acts of the entities were attributable to Canada.

-

31. The first part of the answer – the characterisation of the entities – was based on the text of Articles 202 and 1505 of the NAFTA. According to these provisions, “state enterprise means an enterprise that is owned, or controlled through ownership interests, by a Party” (Article 202) and “[f]or the purpose of this Chapter [Chapter 15 on Competition Policies, Monopolies and State Enterprises] state enterprise means, except as set out in Annex 1505, an enterprise owned, or controlled through ownership interests, by a Party” (Article 1505). In order to make the more encompassing rules of general international law governing, the claimant argued that the three entities at stake were not State enterprises because they did not meet the test of Annex 1505. But the tribunal rejected this argument on the grounds that Annex 1505 was only relevant for Article 1503(3) of the NAFTA, not Article 1503(2). Thus, the test was whether the relevant entities were “owned or controlled” by Canada, which in the tribunal’s view was indeed the case.

-

32. That led to the question of the operation of Article 1503(2) of the NAFTA, which is our focus here. This provision states:

Each Party shall ensure, through regulatory control, administrative supervision or the application of other measures, that any state enterprise that it maintains or establishes acts in a manner that is not inconsistent with the Party’s obligations under Chapters Eleven (Investment) and Fourteen (Financial Services) wherever such enterprise exercises any regulatory, administrative or other governmental authority that the Party has delegated to it, such as the power to expropriate, grant licenses, approve commercial transactions or impose quotas, fees or other charges.

The tribunal, following both the arguments of the parties and a decision of an earlier NAFTA tribunal in UPS v. Canada,Footnote 45 framed this provision as a special attribution rule. As such, it must be understood as a secondary rule which operates [Page 28] at the same stage as other secondary rules, including the rules of attribution in general international law. This interpretation is plausible,Footnote 46 but it may misrepresent the nature of Article 1503(2) and of analogous provisions in other treaties (e.g. Article 22(1) of the ECT).Footnote 47

-

33. Indeed, Article 1503(2) could also be understood as a primary rule of international law specifying which primary rules formulated in the NAFTA govern the conduct of State enterprises. This alternative framing is no less plausible,Footnote 48 particularly in the light of Article 1503 as a whole, which specifies the obligations of each State party in connection with its State enterprises. Perhaps more compellingly, Article 1116(1)(a) of the NAFTA refers to claims brought by investors for breach of obligations under Article 1503(2), further confirming that this provision states a primary rule of obligation. The fact that the jurisdiction of a tribunal under Chapter 11 does not extend to alleged breaches of another primary rule (Article 1503(3)) does not make any difference. That a treaty may limit the jurisdiction of an arbitration tribunal only to claims for breach of certain standards but not others (which may, for example, fall under the jurisdiction of domestic courts or be simply removed from the remit of arbitration tribunals) does not mean that the rules of attribution do not apply to assess whether a certain conduct is attributable to a State. Framed as a primary rule, Article 1503(2) could not serve as a lex specialis with respect to secondary rules of attribution in general international law. The result would be that more conduct of State enterprises may have been attributable to the respondent.

-

34. Leaving aside questions of framing, the tribunal in Mesa Power v. Canada pursued its analysis as if Article 1503(2) was indeed a special (secondary) rule of attribution. As mentioned, the analysis of the interactions between this special rule and the general rules followed the reasoning of the tribunal in UPS v. Canada. The Mesa Power tribunal’s position is summarised in the following excerpt:

The NAFTA thus establishes a special regime which distinguishes between a NAFTA Party and its enterprises, specifies what control obligations the former has over the latter, and thus organises the NAFTA Party’s responsibility for acts of its enterprises. This regime cannot be displaced by the ILC Articles, which, as mentioned above, are [Page 29] residual in nature. … As a consequence, the responsibility regime arising from Article 1503(2) prevails over the residual rules of Article 5 of the ILC Articles. The acts of the [three entities] will accordingly be attributable to Canada if these enterprises were exercising regulatory, administrative or other governmental authority as specified in Article 1503(2) when they carried out the acts in question.Footnote 49

-

35. This conclusion required the determination of whether the three entities, in their impugned acts, were exercising governmental authority. At this stage, given that the term “governmental authority” is not defined in the NAFTA, the tribunal had little choice but to revert to the rules of attribution in general international law, specifically to the rule codified in Article 5 of the ILC Articles and its commentary, to clarify its meaning.Footnote 50 This reasoning accurately reflects the operation of the lex specialis principle, which may displace the general rule in part or fully and, even in the latter case, it does not preclude resort to other rules applicable between the parties for interpretation purposes.Footnote 51

-

36. The conclusion reached by the tribunal in Mesa Power v. Canada, i.e. the application of a special treaty-based attribution rule which made certain acts non-attributable to the State, can be contrasted with the reasoning of the tribunal in InterTrade v. Czech Republic. In this case, the claimant sought to attribute an allegedly unfair tender process managed by an instrumentality established by the respondent through different routes, including reference to the instrumentality’s status under EU law. In support of this argument, the claimant referred to two opinions of the European Commission characterising the instrumentality as a “public contracting entity” under Directive 92/50/EEC and concluding, on that basis, that the mismanagement of the tender process by the entity amounted to a breach of EU law by the Czech Republic.Footnote 52 Unlike the situation in Mesa Power v. Canada, the application of EU law would have meant that the relevant obligations had a wider group of duty-bearers, in that “public contracting entities” were widely defined, encompassing the Czech instrumentality. The tribunal rejected the argument, however, and found that attribution for the purpose of State responsibility for breach of international law was governed not by EU law but by the rules of attribution in general international law, specifically Article 5 of the ILC Articles.Footnote 53 The result was that the acts could not be attributed.

-

37. For present purposes, the decision on InterTrade v. Czech Republic is noteworthy in relation to the issue of framing. As discussed earlier in this preliminary study, the rules on attribution cannot extend the scope – specifically the duty-bearers – of a primary rule arising from a contract, domestic law or international law. If a rule applies only to a specific category of duty-bearers (e.g. judicial institutions), it cannot be extended to apply to administrative institutions merely because both types of institutions are “organs”. By contrast, if a rule defines its duty-bearers broadly (e.g. the State), then conduct attributable to the State will be [Page 30] relevant to determine whether the duty-bearer of the rule has breached it or not. The duty-bearers of a primary rule are thus defined by the rule itself.

-

38. In InterTrade v. Czech Republic, the real inquiry was whether a rule of EU law defining its duty-bearers broadly (encompassing conduct by the Czech instrumentality) had the effect of broadening the duty-bearers of certain investment protection standards under the applicable BIT to include not only the State but also separate instrumentalities. The clear answer is that these are different primary rules, each with its own duty-bearers. The action of instrumentalities is treated as action of the State (the duty-bearer) only if certain conditions are met, described in the general rules of attribution. Thus, the tribunal correctly analysed this issue under such rules and, on the facts, a majority concluded that the conduct was not attributable. The lex specialis issue does not arise in such a context because the two rules operate at different levels, one as a primary rule and the other as a secondary rule (of attribution). There was no conflict between two secondary rules of attribution. Even if such had been the case, as the tribunal seemed to suggest,Footnote 54 the selection of the lex specialis would have been guided by the determination of the relevant primary rules at stake. For attribution of conduct to the State to assess its consistency with the standards of the applicable BIT, the rules of attribution in general international law apply.

-

39. Another aspect of the lex specialis inquiry is raised by the decision of the tribunal in Beijing Urban v. Yemen, which is reported in this volume. At stake was whether the claimant’s links to the Chinese government precluded the tribunal from asserting jurisdiction over the claims under Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention. The respondent argued that the tribunal lacked personal jurisdiction because Article 25(1) excludes inter-State disputes from its remit, and the conduct of the claimant was attributable to the State under the rules of attribution of general international law. The tribunal accepted that the claimant was “a publicly funded and wholly state-owned entity established by the Chinese Government”,Footnote 55 but it rejected the objection.

-

40. For present purposes, the most relevant aspects of this decision concern the framing of the issue and the test applied to address it. It is well established that, unlike arbitration clauses in BITs, Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention is not a standalone basis of jurisdiction. It only defines the scope of jurisdiction of ICSID tribunals. Nor is Article 25(1) a primary rule, as it does not grant a right to bring a claim. But neither does it set out a special rule of attribution of conduct “for the purpose of State responsibility”. It is, like Article 34 of the European Convention on Human Rights, a rule setting out conditions for a claim to proceed before a specific dispute settlement mechanism.

-

41. The tribunal correctly addressed the issue under Article 25(1) as such and, more specifically, in the light of the interpretation given to it by Aron Broches, one of the main drafters of the ICSID Convention. The “Broches factors” or “Broches [Page 31] test” were thus an elaboration of Article 25(1), as the governing rule.Footnote 56 Although the tribunal expressly mentioned the conceptual link between the Broches test and the attribution rules in Articles 5 and 8 of the ILC Articles,Footnote 57 its reasoning makes clear that these other rules were not applied. The test asks whether the entity bringing a claim before an ICSID tribunal is either “acting as an agent for the government” or “discharging an essentially governmental function”.Footnote 58 In either case, the claim would be precluded.

-

42. Despite the resemblance between this test and certain attribution rules, Article 25(1) is clearly not about attribution “for the purpose of State responsibility”. As a result, even if it is framed as a special rule of attribution (for the purpose of determining the jurisdiction of ICSID tribunals or, more specifically, of assessing the nature of the claimant), it is not a lex specialis with respect to rules attributing conduct for the purpose of State responsibility. It is a lex specialis for the purpose of any general rule which may govern the relation between an entity and a State for the purpose of bringing an action. This is not to say that the rules of attribution in general international law may not be used to interpret this dimension of Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention, as far as they do not operate as the governing rules.

-

43. The reference to the Broches test in Beijing Urban v. Yemen also raises a broader question for the relations between special and general rules: the status and scope of operation of the many jurisprudential developments relating to attribution in the case law of investment arbitration tribunals.

2.3. Special rules of attribution applicable in investment disputes

-

44. The issues examined in the following paragraphs can be usefully introduced by reference to an observation made by the tribunal in Bayindir v. Pakistan, reported in this volume. In this case, the tribunal had to determine whether the exercise of a contractual right (the termination of a construction contract) by a Pakistani instrumentality (the National Highway Authority or NHA) could be attributed to the State. The tribunal reasoned that the conditions of Articles 4 and 5 of the ILC Articles were not met, but that the exercise of the right had been under the direction or control of the government, therefore attributable under Article 8. To reach this conclusion, it had to take a stance on the test for attribution under this rule. It made, in this regard, the following statement:

the Tribunal is aware that the levels of control required for a finding of attribution under Article 8 in other factual contexts, such as foreign armed intervention or international criminal responsibility, may be different. It believes, however, that the [Page 32] approach developed in such areas of international law is not always adapted to the realities of international economic law and that they should not prevent a finding of attribution if the specific facts of an investment dispute so warrant.Footnote 59

-

45. The references to the contexts of “foreign armed intervention” and “international criminal responsibility” concern the divergence of views between, on the one hand, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Nicaragua case Footnote 60 and later in the Bosnian Genocide case Footnote 61 and, on the other hand, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in the Tadić case.Footnote 62 This divergence of views concerns the level of control required for attribution (specific to the act or general to the group). In the Bosnian Genocide case, the ICJ noted that the general control test applied by the ICTY could be suitable for that specific context, but that the rule in general international law required specific “effective control”.Footnote 63

-

46. The tribunal in Bayindir v. Pakistan seemed to suggest that the realities of international economic law call for yet another approach under the same rule. It did not clarify this approach but, from the factual discussion, the main modulation was the sufficiency of giving “clearance” for a specific decision in a highly concentrated government where certain actions would not be expected to proceed without at least passive approval from the leader.Footnote 64 The Bayindir test combines therefore a specific context (the high concentration of political authority in one person’s hands which may be found in authoritarian regimes) with an action which falls short of giving a specific direction and is more like a permission. The difference between a specific direction and a mere permission lies at two levels: impulsion and specificity. Permission assumes that the impulsion does not come from the leader and that the “clearance” granted to whomever gives the impulsion can be of a more general nature.

-

47. I will discuss the operation of the rule formulated in Article 8 of the ILC Articles later in this study (Section 4.4). For present purposes, the Bayindir test is but an illustration of what could be seen as investment-specific tests or approaches to the operation of the attribution rules in general international law. Other tribunals have referred to specific tests in relation to attribution but rarely contrasting them to the general understanding in international law. One example concerns the decision in Kardassopoulos v. Georgia, reported in this volume.Footnote 65 The tribunal discussed attribution issues mainly in its award on the merits and concluded that:

[Page 33] whether one applies the principles of attribution set forth in the ILC Articles on State Responsibility or the tests developed in arbitral jurisprudence to ascertain whether the acts or omissions of a particular entity are attributable to a State, the answer in these arbitrations is the same.Footnote 66

The “tests developed in arbitral jurisprudence” mentioned in this excerpt are those referred to in Maffezini v. Spain, a decision of January 2000, i.e. the year before the adoption of the ILC Articles in their second reading.

-

48. The Maffezini tribunal relied on “structural” and “functional” tests to determine whether an entity is a “State entity”. The content of such tests shares some common ground with the general rules of attribution, but it also presents some marked differences, most notably a presumption arising from some specific circumstances:

Here a finding that the entity is owned by the State, directly or indirectly, gives rise to a rebuttable presumption that it is a State entity. The same result will obtain if an entity is controlled by the State, directly or indirectly. A similar presumption arises if an entity’s purpose or objectives is the carrying out of functions which are governmental in nature or which are otherwise normally reserved to the State, or which by their nature are not usually carried out by private business or individuals.Footnote 67

The reasoning of the Maffezini tribunal on this point is debatable, and the overwhelming majority of the case law now follows the rules codified in the ILC Articles, as discussed later in this chapter (Section 4). For example, it seems clear that State ownership of a separate entity does not entail any presumption of attribution as such.Footnote 68 For the acts of such an entity to be attributable, it will normally have to meet the requirements of the rule codified in Article 5 of the ILC Articles. But the specificity of these “tests” and the fact that they are presented in an award rendered in 2010, Kardassopoulos v. Georgia, begs the question of the recognition of attribution rules which are specific for investment disputes.

-

49. All in all, a systematic review of the relevant investment decisions leads to the conclusion that there is no clearly formulated thesis according to which there are special attribution rules in general international law which apply to investment disputes. The few decisions that either suggest or refer to such specificities, such as Bayindir v. Pakistan and Kardassopoulos v. Georgia, proceed on the basis of the rules codified in the ILC Articles. Some earlier decisions, such as Maffezini v. Spain,Footnote 69 RFCC v. Morocco Footnote 70 or Nykomb v. Latvia,Footnote 71 which do not clearly rely on specific routes from the ILC Articles, can be explained by the fact that they faced a less settled body of case law on this issue. In all events, their approach is not presented as a set of investment-specific rules, distinct from the general rules of attribution. For the rest, the wide convergence of the now mature body of [Page 34] investment cases dealing with attribution summarised, for example, in Ortiz v. Algeria Footnote 72 makes it clear that the applicable rules are those of general international law, as codified in the ILC Articles. Any variations from them, even those presented as “tests”, must be understood as elaborations of the requirements of these rules on the specific facts of the case. This is consistent with the views of the ICJ in the Bosnian Genocide case that “[t]he rules for attributing alleged internationally wrongful conduct to a State do not vary with the nature of the wrongful act in question in the absence of a clearly expressed lex specialis”.Footnote 73 The only remaining question is whether they could be extrapolated to other types of disputes. Here, the answer is likely negative, at least in the light of the ICJ’s apparent reluctance to take on board the developments made by investment tribunals on matters of general international law.Footnote 74

3. Question 3: which phase of the proceedings?

3.1. Overview

-

50. The third question concerns the stage of the proceedings in which matters of attribution must be addressed.Footnote 75 Two main related sub-questions arise in this context. The first is whether there is a legal requirement to address matters of attribution at a specific phase of the proceedings or, on the contrary, whether such stage is determined by the nature of the objection and other relevant considerations. The second sub-question concerns the treatment of attribution arguments before a full review of the evidence can be conducted and the allocation of the burden of proof.

-

51. The link between the first and second sub-questions can be illustrated by Consutel v. Algeria.Footnote 76 In this case, the tribunal proceeded on the assumption that matters of attribution must always be handled at the merits and, as a result, at the jurisdictional level, the facts supporting attribution of conduct must be assumed:

The Tribunal considers that the questions of attribution discussed by the parties are questions for the merits and not of jurisdiction. Consequently, subject to what follows, the Tribunal must, when examining its jurisdiction, take for granted that the acts and omissions reproached to Algérie Telecom [a telecommunications operator wholly owned by the State] can be attributed to the Respondent.Footnote 77

Subject to the discussion in Section 3.2, this conclusion provides a clear illustration of the link between the sub-questions identified earlier.

-

52. In what follows, I examine first the reasoning of tribunals to allocate matters of attribution to a certain stage of the proceedings in order to identify what are the [Page 35] considerations guiding such determination. I then analyse the resort to prima facie tests and the allocation of the burden of proof.

3.2. The determination of the relevant phase

-

53. The determination of the appropriate phase at which matters of attribution must be discussed has sometimes been at issue in the investment case law. Whereas it seems reasonable for attribution – as part of the examination of State responsibility – to be addressed once the tribunal has asserted jurisdiction over the dispute, i.e. when examining the merits of a claim,Footnote 78 the question is much more complex than it first appears.

-

54. In the excerpt of Consutel v. Algeria reproduced in the previous sub-section, the tribunal considered that attribution is always a matter for the merits. However, on closer examination, the authorities on which it relies are not so conclusive. The tribunal refers, to buttress its assertion, to several decisions, the earliest of which is Jan de Nul v. Egypt.Footnote 79 In this case, the tribunal reasoned that it was not appropriate “at the jurisdictional stage to examine whether the case is in effect brought against the State and involves the latter’s responsibility. An exception is made in the event that if [sic] it is manifest that the entity involved has no link whatsoever with the State.”Footnote 80 In addition to this first “exception” (manifest lack of attribution), the tribunal also mentioned another “exception” by reference to Salini v. Morocco.Footnote 81 In the latter case, a tribunal addressed attribution at the jurisdictional stage because the parties had extensively pleaded the issue as one relevant to jurisdiction. A similar approach was followed in RFCC v. Morocco.Footnote 82

-

55. The interest of this second “exception” to a purported “rule” is that it depends on how the parties themselves frame the facts relevant for attribution. Framed as an objection to jurisdiction, the tribunal is expected to address the issue at that stage and some tribunals have done so, either presenting their examination as an effort to satisfy the parties’ procedural expectationsFootnote 83 or simply addressing it as an objection to jurisdiction ratione personae.Footnote 84 In one of the latter examples, Teinver v. Argentina, the tribunal reasoned that there was indeed authority to “support the conclusion that matters of state attribution should be adjudicated at the jurisdictional stage when they represent a fairly cut-and-dry issue that will determine whether there is jurisdiction”.Footnote 85 In casu, it rejected the objection on the grounds that the respondent accepted that some conduct was attributable to the State and that, as far as the conduct identified in the objection was concerned, [Page 36] “the fact-intensive nature of Claimant’s allegations” required the tribunal to “postpone adjudication of this issue until the merits phase”.Footnote 86

-

56. Rather than an “exception” to a “rule”, this line of cases suggests that there may be circumstances under which attribution is relevant for jurisdiction. Relevant considerations to make this determination would include: (i) manifest lack of link between the conduct and the State, (ii) the framing and pleadings of the parties, (iii) the overall effect of a finding of non-attribution (whether it excludes jurisdiction altogether or not) and, of course, (iv) factual considerations (which may be addressed at the jurisdictional level if they are sufficiently “cut-and-dry”).

-

57. The decision in Teinver v. Argentina, although clearly distinct in its understanding of the issue, is one of the authorities on which the Consutel tribunal relied. A similar mismatch between the rule asserted and the authorities relied upon can be discerned in another case cited in Consutel, namely Hamester v. Ghana. In this case, the tribunal began its reasoning by stating that “[t]he question whether the issue of attribution is, in a given case, one of jurisdiction or of merits is not, in the Tribunal’s view, susceptible of a clear-cut answer”.Footnote 87 It then provided a nuanced view of the question:

Not all issues, however, are so discrete or easily answered. Many – as is the case with attribution – entail more complex considerations, which could be characterised both as jurisdictional and relevant to the merits (and so to be considered only if the Tribunal has jurisdiction) …

In order to clarify the distinction between a jurisdictional question and a merits question, it is useful to consider the different burden of proof required for each. If jurisdiction rests on the existence of certain facts, they have to be proven at the jurisdictional stage. However, if facts are alleged in order to establish a violation of the relevant BIT, they have to be accepted as such at the jurisdictional stage, until their existence is ascertained (or not) at the merits stage. The question of “attribution” does not, itself, dictate whether there has been a violation of international law. Rather, it is only a means to ascertain whether the State is involved. As such, the question of attribution looks more like a jurisdictional question. But in many instances, questions of attribution and questions of legality are closely intermingled, and it is then difficult to deal with the question of attribution without a full enquiry into the merits. …

In any event, whatever the qualification of the question of attribution, the Tribunal notes that, as a practical matter, this question is usually best dealt with at the merits stage, in order to allow for an in-depth analysis of all the parameters of the complex relationship between certain acts and the State.Footnote 88

This is perhaps the clearest analysis of the issue in the current state of the investment case law. It confirms a prior analysis made in Maffezini v. Spain, where the tribunal distinguished questions of attribution relevant for jurisdiction and merits in similar terms:

[Page 37] the Tribunal has to answer the following two questions: first, whether or not SODIGA is a State entity for the purpose of determining the jurisdiction of the Centre and the competence of the Tribunal, and second, whether the actions and omissions complained of by the Claimant are imputable to the State. While the first issue is one that can be decided at the jurisdictional stage of these proceedings, the second issue bears on the merits of the dispute and can be finally resolved only at that stage.Footnote 89

If the jurisdiction of the tribunal rests indeed on the existence of conduct attributable to a State – irrespective of whether such conduct amounts to a breach of a rule of international law – then the claimants have to establish those facts for the tribunal to have jurisdiction. Only if this is established can the tribunal examine whether certain conduct constitutes a breach or not.

-

58. Given the need for a factual inquiry, this is usually done at the merits stage, where the facts are discussed in detail. Such was the approach followed in Tulip Real Estate v. Turkey, where the tribunal examined whether the conduct of an entity (Emlak) was attributable to Turkey and concluded that, to the extent that the conduct was not attributable, it was “outside of the remit of the Tribunal”.Footnote 90 Such fact-intensive objections to jurisdiction could be addressed at the jurisdictional level, if the tribunal allows for bifurcation, or later, if the objection is joined to the merits. In Maffezini v. Spain, aspects of attribution relevant for jurisdiction were determined at the jurisdictional stage. The tribunal was satisfied – for jurisdictional purposes – with a prima facie showing made by the claimant that the entity at stake (SODIGA) was acting on behalf of the State.Footnote 91 The evidentiary burden that the claimant was required to discharge, although prima facie, was quite significant. This raises the additional question of what exactly is meant by a prima facie test in this context.

3.3. The operation of prima facie tests and the allocation of the burden of proof

-

59. Reference to a prima facie test to handle facts at the jurisdictional level is common in the investment case law. For example, the tribunal in Mesa Power v. Canada noted that “attribution is generally best dealt with at the merits stage. This is subject to a prima facie pro tem test being performed in the context of jurisdiction to ascertain that the acts alleged are susceptible of constituting treaty breaches.”Footnote 92 However, little clarity is provided on the parameters of this prima facie test. To explore such parameters, it is useful to distinguish three main aspects: (i) the level of scrutiny of the facts, (ii) the nature of the objection, and (iii) the allocation of the burden of proof.

-

60. The first issue was examined with characteristic insight by Judge Rosalyn Higgins in her Separate Opinion in the first phase of the Oil Platforms case.Footnote 93 The context of the analysis was a peculiar objection to jurisdiction raised by the US [Page 38] arguing that the treaty invoked by Iran was not applicable ratione materiae to the dispute. Judge Higgins identified the fundamental tension underpinning resort to prima facie tests as follows:

a struggle between the idea that it is enough for the Court to find provisionally that the case for jurisdiction has been made, and the alternative view that the Court must have grounds sufficient to determine definitively at the jurisdictional phase that it has jurisdiction.Footnote 94

One particularly important precedent colouring her entire analysis was the Mavrommatis case, a diplomatic protection dispute brought under Article 26 of the UK Mandate over Palestine before the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ).Footnote 95 The UK challenged the jurisdiction of the PCIJ, leading the Court to examine at the jurisdictional stage whether the facts alleged by Greece as constitutive of the dispute fell under the terms of the mandate. The Court conducted a thorough analysis of each claim at the jurisdictional level, noting however that its analysis did not prejudge the merits. Judge Higgins contrasted the Mavrommatis approach with the less demanding one followed by the ICJ in the Ambatielos case, where the Court seemed to content itself with some degree of plausibility.Footnote 96 A significant difference between the two cases was that, in Ambatielos, the merits of the claim were expressly reserved to a tribunal other than the Court. But the cases epitomise two contrasting positions regarding the treatment of facts at the jurisdictional level.

-

61. Judge Higgins pursued her analysis and formulated a principle according to which the approach to be followed would lie somewhere in between the thoroughness of Mavrommatis and the flexibility of Ambatielos. Applied to the facts of the Oil Platforms case, she suggested that:

The only way in which, in the present case, it can be determined whether the claims of Iran are sufficiently plausibly based upon the 1955 Treaty is to accept pro tem the facts as alleged by Iran to be true and in that light to interpret Articles I, IV and X for jurisdictional purposes – that is to say, to see if on the basis of Iran’s claims of fact there could occur a violation of one or more of them.Footnote 97

-

62. This test was brought into the investment case law by a series of decisions, mainly Impregilo v. Pakistan Footnote 98 and then Jan de Nul v. Egypt.Footnote 99 However, in this process it underwent a transformation. The level of scrutiny of facts, if they are to be taken as “alleged”, is clearly less demanding than the prima facie test in Maffezini, discussed in the previous section. This could be explained by the fact that in the Oil Platforms case and in Impregilo v. Pakistan,Footnote 100 the test was used to determine whether the facts as alleged would fall under the provisions of the treaty [Page 39] invoked by the claimant or, in other words, whether the treaty prima facie applied to them.

-

63. The latter conclusion raises the second issue mentioned above, namely the nature of the objection. Whereas in the Oil Platforms case and Impregilo v. Pakistan, the key question was whether the alleged facts a priori fell under the treaty (objection ratione materiae),Footnote 101 in Maffezini v. Spain and in cases where attribution is raised as a jurisdictional obstacle, the objection is ratione personae.Footnote 102 Facts relevant for the assessment of a breach of a primary rule may be taken as alleged at the jurisdictional level to determine if the treaty prima facie applies to them. But facts relating to attribution are relevant for the assessment of both jurisdiction ratione materiae and jurisdiction ratione personae. Extrapolating the prima facie test from a broad assessment of whether the facts fall under a treaty to a specific assessment of whether certain acts are attributable to a State is a non-obvious step. It was made by the tribunal in Jan de Nul v. Egypt,Footnote 103 and it has thereafter featured in decisions relying on Jan de Nul, such as Consutel v. Algeria.Footnote 104 The problem of this extrapolation is that the type of demanding prima facie assessment conducted in Maffezini v. Spain fell between the cracks. The extrapolation had the result of transforming one demanding prima facie test into a mere fiction or assumption of facts for jurisdictional purposes. In other words, it undermines the possibility to raise an objection to jurisdiction ratione personae for lack of attribution at an early stage.

-

64. The third issue, the allocation of the burden of proof, is affected by this extrapolation. If attribution matters relevant for jurisdiction or breach are conflated, assumed to be met prima facie and allocated en bloc to the merits, the evidentiary burden of the claimant at the jurisdictional level is greatly facilitated. The consequences of this conflation may be alleviated when there is no bifurcation of jurisdiction and merits. In such case, the prima facie test loses its relevance,Footnote 105 and the claimant has the burden to establish the facts on which it claims attribution for purposes of both jurisdiction and breach. But in case of bifurcation the problem re-emerges. Even if the attribution allegations are defeated at the level of merits, that creates significant unnecessary costs for both parties. If the tribunal “assumes” – rather than establishing prima facie in line with the more demanding Maffezini test – the facts underpinning its jurisdiction ratione personae, it may also be overstepping its powers.

-

65. The problems arising from the extrapolation of one prima facie test developed for jurisdictional objections ratione materiae to objections ratione personae can be avoided if matters of attribution are handled in the light of the [Page 40] general considerations made in Hamester v. Ghana.Footnote 106 When certain facts must be established for the tribunal to have jurisdiction, then the burden of proof is on the claimant and the question must be addressed either at the jurisdictional phase or as a jurisdictional objection joined to the merits.

-

66. Addressing it at the jurisdictional phase may be appropriate under certain circumstances, discussed earlier by reference to Maffezini v. Spain and Teinver v. Argentina, including whether: (i) there is a manifest lack of link between the conduct and the State, (ii) the parties frame or plead the question as one of jurisdiction, (iii) the overall effect of a finding of non-attribution would exclude jurisdiction altogether, and (iv) the relevant factual considerations are sufficiently distinct to be addressed separately at this stage.

-

67. A tribunal may decide, instead, to join the jurisdictional objection ratione personae to the merits. In such case, once the merits phase is reached, attribution will have to be established in full. The question then arises of how the joined jurisdictional objection is to be addressed. In both Hamester v. Ghana Footnote 107 and Tulip Real Estate v. Turkey,Footnote 108 the tribunals rejected bifurcation of this issue, so the objections were addressed together with the merits. Yet, whereas the Hamester tribunal appeared to convert the objection into a matter for the merits, thereby asserting jurisdiction but rejecting attribution of specific conduct under certain claims, the Tulip Real Estate tribunal concluded that conduct non-attributable to Turkey was “outside the remit of the Tribunal”.Footnote 109

4. Question 4: what are the main attribution routes under general international law?

4.1. Overview

-

68. The fourth question concerns the main routes of attribution admitted in general international law as they are codified in Part I, Chapter II of the ILC Articles. Several routes have featured in the practice of investment tribunals, most notably attribution of conduct of State organs (Article 4), State instrumentalities (Article 5), and persons or entities acting under the instructions, direction or control of the State (Article 8). There are variations in the operation of these routes, such as the question of acts ultra vires (Article 7), and there are also other routes, such as conduct acknowledged and adopted by the State (Article 11), which are discussed in the decisions reported in this volume. Still other routes, rarely discussed in the investment case law, include Article 6 (organs of a State placed at the disposal of another State) and Article 10 (insurrectional movements).

-

69. The discussion in this section is organised under five headings, one for each main attribution route (Articles 4, 5, 8 and 11, respectively) and another for all the rarely used ones (Articles 6, 9 and 10). The question of ultra vires action [Page 41] (Article 7) is a modulation of certain attribution rules. It will be discussed in their specific context and also in Section 5.4 as one recurrent problem.

4.2. Conduct of organs of the State (Article 4)

-

70. The conduct (actions or omissions) of State organs is attributable to the State.Footnote 110 This is a classic rule of customary international law, codifiedFootnote 111 in Article 4 of the ILC Articles in the following terms:

-

1. The conduct of any State organ shall be considered an act of that State under international law, whether the organ exercises legislative, executive, judicial or any other functions, whatever position it holds in the organization of the State, and whatever its character as an organ of the central Government or of a territorial unit of the State.

-

2. An organ includes any person or entity which has that status in accordance with the internal law of the State.

-

-

71. Paragraph 1 removes any doubt regarding possible variations in attribution arising from the internal organisation of a State. Whether States are organised following a tripartite separation of powers or not, and whatever the form of power allocation across sub-national entities, the conduct of organs from any governmental structure is attributable to the State.

-

72. The decision in Tethyan Copper v. Pakistan, reported in this volume, provides a useful illustration of the basic rule. In this case, an Australian company active in the copper mining sector claimed that the authorities of Balochistan, a province of Pakistan, had refused to grant it a mining lease in violation of the Australia–Pakistan BIT. The tribunal made a distinction between, on the one hand, federal and provincial organs and, on the other hand, an agency established as a statutory corporation under provincial legislation (the Balochistan Development Authority or BDA). Conduct of the first group was clearly attributable to Pakistan under the rule codified in Article 4 of the ILC Articles, irrespective of the nature of the organs (executive, legislative or judicial) or their level in the internal organisation of the State (federal, provincial or municipal, or other devolution structures).Footnote 112

-

73. This conclusion was not affected by the fact that the province of Balochistan had a separate legal personality under domestic law. According to the tribunal, given that sub-national entities have no international legal personalities, if their acts could not be attributed to the State, “it would be impossible to make the [Page 42] conduct of provincial units subject to international obligations, which would in turn discourage investments in areas that are governed by provincial law and/or in which investors have to deal with provincial authorities”.Footnote 113 Thus, in the context of State organs, it makes no difference whether the territorial subdivision has a separate legal entity, as is very frequently the case.

-

74. In addition, in the context of State organs, the nature of the acts, sovereign or commercial, has no bearing. As stated by the commentary to Article 4 of the ILC Articles, which the tribunal quoted, it is “irrelevant for the purposes of attribution that the conduct of a State organ may be classified as ‘commercial’ or as acta iure gestionis”.Footnote 114 It is important to distinguish the sovereign vs commercial dichotomy from whether the organ acts in an “official capacity” or in a purely private capacity. Only action/inaction in an “official capacity”, whether sovereign or commercial in nature, is attributable. Whereas the “sovereign” or “commercial” classification focuses on the nature of the “act”, the “official” or “private” capacity classification is a matter of “context” or “appearance”.Footnote 115 If an act (whether sovereign or commercial) is performed by a person cloaked with governmental authority or holding herself out as a State official, then it is attributable to the State, even if the act is ultra vires (see below, Section 5.4). By contrast, in the absence of the “appearance” of an official capacity, the acts are not attributable. I will return to this difference later in this study (Section 5.3).

-