Introduction

The role of Perinatal Mental Health Services is the prevention, detection and management of perinatal mental health problems that complicate pregnancy and the post-natal time. These include new onset problems, reoccurrences of previous problems in women who have been well for some time and those with mental health problems before they became pregnant (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health, 2012). The wide range of disorders each of which may vary from mild to severe (Table 1) impact both on mothers and on their potential bonding with their infants. The documented evidence of adverse outcomes together with the many settings in which pregnant women and mothers are seen means many services and professionals are involved. Some of these are health promotion; general practitioners; practice nurses; public health nurses; the primary care team; midwives; obstetricians, secondary care community and inpatient mental health services and Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services. Other services such as addiction and child protection may also be involved (CR197, 2015).

Table 1. Rates of perinatal psychiatric disorder per thousand maternities with estimated number of women effected in Ireland per year

Rate is estimated based on average number of births for the years 2012–2016.

There may be some women who experience more than one of these conditions.

Ref: Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Model of Care (HSE, 2017).

This paper describes the development of the specialist component in Ireland through the design and implementation of a National Model of Care by the Health Service Executive (HSE) which was formally launched in November 2017.

Prior to this, very limited services were available in Ireland and these only in the three Dublin voluntary maternity hospitals. Each of these had a part-time perinatal psychiatrist (three or four sessions per week) and either a single mental health nurse (National Maternity Hospital) or mental health midwife (2.5 whole time equivalent in the Rotunda Hospital).

The publication of A Vision for Change in 2006, Government policy for mental health services in Ireland sounded the death knell for future expansion (DOH, 2006). It recommended one additional adult psychiatrist and one senior nurse with perinatal expertise be appointed to act as a resource nationally in the provision of care to women with severe perinatal mental health problems.

A happy coincidence of two factors provided the opportunity to overcome this barrier. The publication of the National Maternity Strategy (Ireland) 2016–2026 (DOH, 2016) included seven Mental Health Actions for implementation (Table 2). Its publication coincided with the short-lived tenure of the HSE Mental Health Division (MHD) led by a Mental Health Director (MHD 2014–18) together with a National Clinical Lead. The latter recommended that the Division design a Model of Care for Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services to respond in part to the seven Actions thereby contributing an essential component of an integrated perinatal mental health response (CR197, 2015).

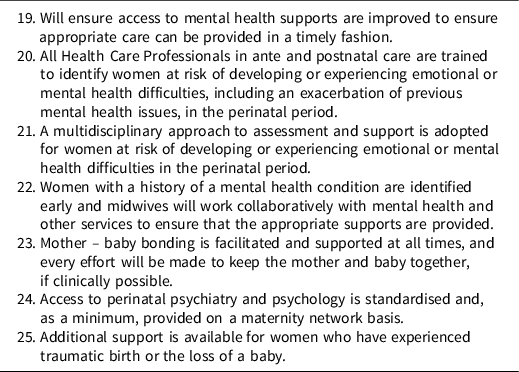

Table 2. Mental health actions to be implemented by the National Women and Infants Health Programme

The MHD established a Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Working Group in 2016 chaired by the then National Clinical Advisor Mental Health. The Working Group’s task was to design a specialist Model of Care. The terms of reference encompassed both the strategy for and operation of a Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Service for Ireland taking into account:

-

The interests of women, infants and their families

-

Relevant national and international research and evidence based practice and standards

-

Relevant national and international policy documents and reports.

The Working Group was multidisciplinary, including two obstetricians, with service user input provided by the Chief Executive of the Association for the Improvement of Maternity Services (AIMS Ireland).

Whilst the Group’s terms of reference were women with moderate to severe mental illness, they also included a central role in educating and training all involved in delivering services to women during the antenatal and post-natal periods. This was to ensure women with milder mental health problems would be both identified and receive appropriate help from skilled staff at primary care level in the community and within maternity services.

The Service User member cogently argued for the specific inclusion of the primary care maternity unit/hospital component; that is ensuring a response to women with milder mental health problems, an overall perinatal mental health clinical pathway with clear links between the non-specialist and specialist components and so these were also addressed.

This indicated there was an imperative to design an integrated care pathway between all services.

Developing the Model of Care

Key factors identified by the Working Group which strongly influenced the Model agreed were the epidemiology of mental illness in the perinatal period, recent birth rates in Ireland from which were estimated the number of women likely to be affected by perinatal mental health illness in a year (see Table 1), national policy documents as already outlined (Department of Health, 2006, 2016) and the evidence for perinatal mental illness and its treatment (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Parsonage, Knapp, Lemmi and Adelaja2014; RCPsych CR197, 2015; NICE 192, 2015). An important aspect of the latter was the potential adverse impacts on infants of such illnesses (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Hipwell, Hooper, Stein and Cooper1996, OCEC YMH, 2014), 72% of the overall impact being on the child (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Parsonage, Knapp, Lemmi and Adelaja2014). The impacts are known to continue into adulthood and include cognitive (Slein et al. Reference Slein, Pearson, Goodan, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014) as well as emotional and behavioural problems (Geradin et al. Reference Geradin, Wendland, Bodeau, Galin, Bialobos, Tordjman, Mazet, Darbois, Nizard, Dommergues and Cohen2011; Leis et al. Reference Leis, Hevon, Stuart and Mendelson2013) with disorganised attachment to the mother recognised as particularly relevant (Slein et al. Reference Slein, Pearson, Goodan, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014).

Core values and principles on which to base the Model of Care were identified, with the service user perspective being key, and these are summarised as follows:

-

Increased awareness of mental health issues based on normalising the experience.

-

Training for all maternity staff in perinatal mental health being necessary to ensure this.

-

Ensuring those working in maternity services understand that mental health is on a par with physical health.

-

Universal sensitive and supportive mental health screening at the maternity service booking appointment and review clinics, including postnatally.

-

A clearly established pathway of care.

-

Specialist mental health services to avoid separating mothers and their babies, including during a mental health admission.

-

Advocacy for women experiencing perinatal mental health problems.

-

A recognition of and support for women who have complex caring responsibilities as a risk factor such as a child or adult with a disability (HSE, 2017).

The current provision of maternity services in Ireland was a challenge as there are 19 maternity services/ hospitals in Ireland with births in 2016 ranging from 1034 (South Tipperary General Hospital) to 9017 (National Maternity Hospital) (Department of Health, 2020).

The Working Group concluded that:

The organisation of the new Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Service, taking all of the above into account, would be based on the maternity network/hospital group structure in Ireland. The maternity service/hospital in each network with the largest number of deliveries would host the Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Team. Each would be a Hub site and would support the smaller maternity services in the Maternity Network (the spoke sites).

Figure 1 shows the hub and spoke specialist perinatal mental health networks including the hub site in each.

Fig. 1. Hub and spoke specialist perinatal mental health structure.

The functions of a Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Service, derived from the core values and principles, were further addressed and the resources required to deliver these decided. It was agreed a full mental health multidisciplinary team led by a consultant perinatal psychiatrist would be based in each hub. Both the hubs and spokes would also have a perinatal mental health midwife whose role was specifically to ensure a response to women with mild to moderate mental health problems. The Hub Team would support spoke sites by providing clinical advice, offering second opinions and organising relevant education for spokes and also hub staff. Finally the Working Group agreed a referral pathway for implementation in each maternity service (Fig. 2). Key to this is ensuring that all women at first point of contact with the maternity service are routinely asked about their mental health (Whooley et al. Reference Whooley, Avins, Miranda and Browner1997).

Fig. 2. Perinatal mental health referral pathway.

Other issues addressed in the Model of Care included standards of care (CG192, NICE 2014/16); governance structures for the services; initial and ongoing education; programme metrics and evaluation.

Implementing the Model of Care

Clearly as a new service development, funding was essential to implement the Model of Care.

It is a measure of the recognition of the need for these services that the Mental Health Division (MHD) allocated some initial funding (€0.5m 2016, €0.5m 2017). At the formal launch in November 2017 the Minister of State for Mental Health allocated a further €2m and in 2019 €0.6m was allocated as an important component of implementing the National Maternity Strategy (DOH, 2016).

This enabled the Clinical Lead (CL) and Programme Manager (PM) to move seamlessly from design to implementation, when requested to do so by MHD. For this purpose a National Oversight Implementation Group was set up with clear terms of reference. Its specific brief was to work with local services in the recruitment of staff and provide induction for new staff in conjunction with existing perinatal mental health staff. The group also had to support hub site development and develop and support the spoke structure. A key function was to organise education and training in perinatal mental health. In additional a dataset was designed and implemented to capture clinical activity and outcomes. Finally the development of a National Mother and Baby Unit (MBU) was to be advanced.

To reflect the integrated ethos of the Model of Care, it has from the first been jointly implemented with the HSE’s National Women and Infants Health Programme (NWIHP), which also funded all the new perinatal mental health midwife posts. This integrated approach is fully in line with Sláintecare, the Government’s strategy on the Future of Healthcare in Ireland (Houses of the Oireachtas, 2017).

First actions

The CL and PM identified and undertook the key first actions required to begin establishing the Model of Care nationally.

These were:

-

i. Site visits:

These were made to each of the six maternity hub sites to meet the Clinical Lead Obstetrics and the Director of Midwifery and also the local mental health service managers in Southeast Dublin, Limerick, Cork and Galway.

-

ii. Appointment of perinatal psychiatrists:

A crucial early action was the recruitment of a perinatal psychiatrist at consultant level for each of the six hub sites. As perinatal psychiatry is not a recognised sub-speciality in Ireland yet, posts were recruited as General Adult Psychiatrist with special responsibility for Perinatal Psychiatry.

Fortunately, the three existing perinatal psychiatrists had offered senior trainees special interest sessions and so there were a number of potential applicants. Additional training for the three successful local applicants in perinatal psychiatry was provided by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Perinatal Psychiatry Training Course for Consultants as part of implementing the Model of Care.

One existing part-time psychiatrist opted to move to a full-time post in perinatal psychiatry, a UK Consultant Perinatal Psychiatrist successfully competed for one post and an Irish doctor who had trained in perinatal psychiatry in the US for another.

-

iii. Setting up the National Oversight and Implementation Group (NOIG):

With the recruitment of the first two full-time perinatal psychiatrists in the National Maternity Hospital, Dublin and University Maternity Hospital Limerick, the Group was formally established and also included the existing perinatal mental health nurse and midwife. It now has representation from each hub site and each discipline and is chaired by the CL and supported by the PM. Each discipline representative on the NOIG is charged with establishing a national peer group and each reports back to the NOIG any issues of concern. The Perinatal Mental Health Midwife representative is also tasked with reporting back on issues arising in the Spoke sites.

-

iv. Recruitment of Mental Health Nurses and Perinatal Mental Health Midwives:

The next task was to recruit perinatal mental health nurses (hubs) and perinatal mental health midwives (hubs and spokes). This required joint working with the HSE Office of Nursing and Midwifery Service Director (ONMSD) and Nursing and Midwifery Planning Development Unit Dublin to develop clear and complementary job descriptions, an essential undertaking as there was a widespread misunderstanding that either a mental health nurse or a midwife could be appointed to the perinatal mental health midwife posts.

-

v. Induction:

An induction schedule was developed and agreed for these two roles. As some of the midwives had limited previous experience in mental health, this required a detailed approach with training in mental health assessment and management within a clinical supervision framework. Conversely, the mental health nurses and all other disciplines on the hub team required induction to the maternity services and their functions.

-

vi. Recruitment of Health and Social Care Professionals:

Recruitment of health and social care professionals to hub teams began in the latter half of 2018. All were at senior level and required adaption of existing job descriptions for the role.

As with every project, most steps went smoothly but a few not so smoothly manifesting largely in recruitment delays and accommodation issues. Table 3 summarises progress during the implementation phase, January 2018 to June 2021.

Table 3. Implementation timeline

Review of progress

A recent review examined barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social settings, one of WHO’s Millennium Development Goals (WHO, 2008).

The review identified a wide range of barriers and concluded there was a complex interplay of system-level factors across different stages of the care pathway that can influence the effective implementation of perinatal mental health care (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts2021). This prompted us to review what worked well and not so well in implementing the Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Model of Care in Ireland. The key factors are outlined below and fortunately there were many more facilitators than barriers.

The facilitators of implementation included an implementation mechanism being established at time of launch by the Mental Health Division was a key factor in developing the services nationally and in a uniform manner. The involvement of existing highly trained staff in perinatal mental health in Ireland who worked closely with all stages of design and implementation was crucial. Funding was made available at the time the Model of Care was launched without which none of this could have happened. The close link with the Tavistock Clinic, London for SPMH training of psychiatrists who could then subsequently apply for the new consultant positions was invaluable. The development of the perinatal mental health midwife role nationally meant the service user imperative of ensuring women with milder mental health problems could have their needs addressed was met. Close and good working relationships were established with all hub and spoke sites and enabled smooth implementation. The programme was able to work closely with the HSE National Recruitment Service to develop bespoke panels to fill posts in line with specifically designed job descriptions and to run the competitions for the three HSE sites together meant posts could be filled in a timely manner. The development of the PMH Healthcare app for all frontline staff was an efficient way of providing PMH specific information and training to SPMHS teams and other frontline staff; metrics on this indicate a high take up rate of use by public health nurses in particular. Six full-time higher trainee posts in psychiatry were funded by the HSE and approved by the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland. These will ensure perinatal psychiatrists are available in Ireland in the future and will offer this training to higher trainees who subsequently work as consultants in community psychiatry teams.

Barriers were that funding was diverted for most staff in the SPMHS Galway University Hospital team in late 2019–2020; this was returned in 2021. Difficulty in the provision of accommodation (team base and clinical space) for the hub teams in all three HSE sites remains an ongoing issue. There is no specific data system to collect PMH information and measure outcomes at patient level, both in terms of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

There is more to do and a particular focus is the development of a National Mother and Baby Unit. The latter will require a concerted effort to secure the funding to build and run this essential component of Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services.

Such a unit means women with severe mental illness during the first post-natal year who require admission are not separated from their babies. This will ensure the mother’s relationship with and care of her baby is seen as a priority together with treatment of her mental illness. This is crucial as it is well recognised that mothers retain and enhance their role as primary caregiver for their babies when they have strong, positive relationships not disrupted by separation (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Marks, Platz and Yoshida1995; Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Macdonald, Seneviratne, Waites and Pawlby2018).

Other actions include the delivery of a bespoke SPMHS training programme to the Hub and Spoke teams in 2021 and continuing in 2022. Further development of education in PMH for public health nurses following contributions to their guidelines for identifying and responding to post-natal mental health problems is in train. In 2021 implementation of the Model of Care recommendation to have an identified Community Mental Health Nurse with special interest in perinatal mental health in each community based double sector, thereby enhancing integrated working, will be addressed in 2023. Further development of spoke structures, specifically the liaison psychiatry provision, and a ringfenced virtual perinatal psychiatry service for spokes is required. The latter should be in place in the Saolta Hospital Group by the end of 2022. Continuing the rollout of the PMH Healthcare App which now has over 1200 frontline staff the majority being public health nurses and midwives. This to include metrics to determine effectiveness as an educational tool. The provision of a bespoke IT database for ease of collection of activity and outcome data to guide further clinical service development is badly needed.

In reviewing progress, the unexpected diversion of funding in late 2019 and throughout 2020 which we could do little to influence other than robust advocacy was a major, albeit temporary, obstacle. Early and pro-active consideration of accommodation in which teams can see women and their families would have been useful in the three HSE Hub Sites and is an important message for anyone undertaking similar projects.

Conclusion

This unexpected opportunity to develop Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services in Ireland has made good progress in the 4.5 years since the Model of Care launch.

As always, designing the Model of Care was far easier than implementing it. Our experience proves the now well-recognised principle that it is essential to have a robust implementation mechanism with dedicated staff to ensure this happens. However, none of this would have been possible without the ongoing support, encouragement and input of all the pre-existing staff in the perinatal mental health services.

The recent review of progress has highlighted the need to adjust the Model to respond, for instance, to the identified need for spoke augmentation with dedicated perinatal psychiatry input. The updated Royal College of Psychiatrists Report on Perinatal Mental Health Services (CR232, 2022) re-emphasises the importance of also focusing on the mother–infant relationship. The lack of parent–infant services in Ireland in general and specifically parent–infant mental health services is an important action which must be addressed in implementing Sharing the Vision (Department of Health, 2020) Ireland’s new mental health policy.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Author [MW] has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author [FO] has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Clinical standards

The Health Service Executive’s Mental Health Division (MHD) was responsible for the provision of specialist mental health services. In recognition of the need for Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services, the MHD prioritised the development of this Model of Care in 2016. Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services form one component of an integrated perinatal mental health service response (CR197, 2015).