Introduction

Universal Credit (UC) debuted on the global policy stage in 2013. UC stepped into the ‘uncharted territory’ (Pareliussen, Reference Pareliussen2013: 17) of combining means-tested social security benefits for out of work adults with wage top-ups for low paid workersFootnote 1 in the UK. The reform was designed rapidly to deliver neoliberal cost-cutting priorities within an austerity paradigm (Monaghan and Ingold, Reference Monaghan and Ingold2019: 362). Crucially, UC introduces low-paid workers (who may previously have claimed working tax credit) to a regime of social security based on mandatory job search requirements enforced by punitive benefit sanctions. There is ‘no real international or historical precedent’ (Clegg, Reference Clegg2015: 497) for this large-scale application of job search requirements to low-paid workers to promote ‘progression’ via extra working hours or multiple jobs (McKnight et al., Reference McKnight, Stewart, Mohun Himmelweit and Palillo2016; Millar and Whiteford, Reference Millar and Whiteford2020; Work and Pensions Committee, 2016). Usually, a tax credit operates as an ‘employment-conditional earning subsidy’ (Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy2015: 4). UC subjects low paid workers to double conditionality by adding job search conditions on top of employment conditions.

This article is the first to investigate how in-work UC conditionality is experienced at micro level by claimants over time. Our in-depth qualitative longitudinal research was based on an abductive research strategy ‘to construct descriptions and explanations that are grounded in the everyday activities of […] social actors’ (Blaikie, Reference Blaikie, Lewis-Beck, Bryman and Futing Liao2004: 2). We report findings from a sample of 58 UC claimants, who participated in a total of 141 interviews over three waves of interviews (ESRC ‘Welfare Conditionality’ study 2014–17). The focus is particularly on the experiences of 30 interviewees who were employed during one or more waves of the study (76 interviews). This bottom-up perspective is necessary to understand how UC, as a completely new policy approach, affects real people’s lives and their in-employment job search decisions. An existing wealth of quantitative literature identifies the economic effects of sanctions on unemployment benefit recipients’ employment outcomes (Abbring et al., Reference Abbring, Van den Berg and Van Ours2005; Arni et al., Reference Arni, Lalive and Van Ours2013; Fredriksson and Holmlund, Reference Fredriksson and Holmlund2006; Lalive et al., Reference Lalive, Zweimuller and Van Ours2005; Boockmann et al., Reference Boockmann, Thomsen and Walter2014). However, our contribution is to explore the social impacts of extending welfare conditionality (i.e. mandatory engagement in job search activities enforced by benefit sanctions for non-compliance) to ‘in work’ UC recipients by presenting new analysis firmly grounded in the experiences of low paid workers.

First, we outline welfare conditionality in relation to the development of Universal Credit. Second, we detail our research methods. Third, we present empirical evidence to identify a series of conditionality mismatches that highlight contradictions and counterproductive aspects of conditionality for in-work UC claimants. We conclude by reflecting on the broader implications of in-work conditionality and the consequences of the new coerced-worker-claimant model for welfare systems and labour markets.

Welfare conditionality and Universal Credit

Benefit sanctions are core to UK welfare conditionality underpinning UC. Existing literature shows that benefit sanctions can, in some countries, result in short-term movement from unemployment benefit to paid employment (Abbring et al., Reference Abbring, Van den Berg and Van Ours2005; Arni et al., Reference Arni, Lalive and Van Ours2013; Lalive et al., Reference Lalive, Zweimuller and Van Ours2005; Boockmann et al., Reference Boockmann, Thomsen and Walter2014). However, sanctions are not always effective (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cancian and Wallace2014) and, in the longer term, have been found to extend unemployment or reduce job quality, earnings and retention (Arni et al., Reference Arni, Lalive and Van Ours2013; Fording et al., Reference Fording, Schram and Soss2013; Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018). Loopstra et al. (Reference Loopstra, Reeves, Mckee and Stuckler2015) show sanctions led to a ‘substantial increase’ in Jobseeker’s Allowance exit, but most did not enter employment and were instead distanced from collective social support (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Dwyer, McNeill and Stewart2016). Similarly, whilst the National Audit Office (NAO, 2016) found JSA sanctions had a significant effect in getting claimants off benefit, they were just as likely not to find work as to enter employment and there were no positive earnings effects. Sanctions have been found inappropriate for disabled people (Weston, Reference Weston2012; Newton et al., Reference Newton, Meager, Bertram, Corden, George, Lalani, Metcalf, Rolfe, Sainsbury and Weston2013; Hale, Reference Hale2014; Work and Pensions Committee, 2014, 2015; Oakley, Reference Oakley2016; Moran, Reference Moran2017) and can even reduce disabled benefit recipients’ likelihood of working (Reeves, Reference Reeves2017). The existing studies (above) investigate moves from unemployment to paid work, rather than moves from part-time to full-time work. However, conditionality may be less effective for workers than for unemployed people because ‘the total number of people with conditionality requirements of some kind is increased, while employment services are limited … and sanctions on part-time workers for failure to job search or take up full-time jobs may seem impractical or lack public support’ (OECD, 2014: 104). In this article, we investigate how workers, rather than unemployed people, experience sanctions and support.

UC is the most all-encompassing manifestation of conditionality in any developed welfare system and is designed to restrict access to the social safety net by making means-tested benefits contingent on mandated claimant work responsibilities. The primary obligations are to provide evidence of extensive job search and attend work coach appointments and/or outsourced back-to-work programmes (sometimes requiring mandatory unpaid forms of work). Failure to undertake specified activities leads to severe benefit sanctions that can trigger debt, rent arrears, food bank use and can ultimately result in some claimants becoming homeless, destitute or suicidal (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2018a, Reference Dwyer2018b; Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Dwyer, McNeill and Stewart2016; Reference Wright, Dwyer, Jones, McNeill, Scullion and Stewart2018; PAC, 2017; Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018). Initially, UC was mistakenly lauded as a great success and ‘at the forefront of efforts by OECD countries to transform and modernise their activation policies’ (OECD, 2014:13) with predictions that it would boost employment by improving work incentives and simplifying the social security system (Pareliussen, Reference Pareliussen2013: 5). Additionally, its ‘ground breaking’ approach to providing employment support to ‘in work’ UC claimants was hailed as potentially ‘revolutionary’ in helping low paid claimants progress within the labour market (cf. Work and Pensions Committee, 2016). However, UC should not be interpreted as a benign administrative improvement.

Whilst strict work-related requirements have long been used to ‘activate’ unemployed people in many countries, the UK is exceptional in rapidly recategorizing many disabled people and lone parents as unemployed and applying a harsh conditionality regime to them (Adler, Reference Adler2018; Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2016; Fletcher and Wright, Reference Fletcher and Wright2018; Immervoll and Knotz, Reference Immervoll and Knotz2018; Whitworth and Griggs, Reference Whitworth and Griggs2013). UC compounds these trends by creating new connections between means-tested housing support, low-wage supplements and childcare subsidies. When roll-out is complete, about half of the anticipated 7m UC claimant households are projected to be in-work, with 1m expected to ‘earn more and progress in work’ (DWP, 2018). Prior to Universal Credit, conditionality ended when employment exceeded 16 hours. UC blurs the conditionality boundary because it routinely applies the full conditionality default (35 hours of work or job search) to unemployed claimants and those working any number of hours, triggering changes in conditionality regime according to earnings thresholds (CPAG, 2018 Footnote 2 ).

Universal Credit combines previously distinct and contrasting policy logics, or ‘paths’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994), working at cross purposes, with profound consequences for part-time and/or low-paid workers and their households. The resulting policy amalgam is a misfit, in which the underlying flawed assumptions about ‘dependency’ (Wright, Reference Wright2012) have been extended to low paid workers. On the one hand, the existing benefit system, for ‘undeserving’ inactive jobseekers, has long been deterrence-based, with below-poverty level payments and minimal stigmatised employment services (Fletcher and Wright, Reference Fletcher and Wright2018). Recently, a ‘punitive turn’ (ibid.), involving the 2010 ‘great sanctions drive’, the 2012 harsher sanctions regime (Adler, Reference Adler2018; Webster, Reference Webster2017) and major cuts to Jobcentre Plus (JCP) provision, have re-orientated the social security system towards disciplinary and punitive requirements at the expense of assisting people to get jobs (Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2018a; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Fletcher and Stewart2020). On the other hand, the success of the earlier Labour governments’ (1997-2010) conversion of wage top-ups from benefits (Family Credit) to tax credits (most recently, Working Tax Credit) was that it created a relatively generous and ‘respectable’ way to incentivise people to take jobs that would not otherwise be viable financially or possible practically. This was valuable for low-paid parents, especially mothers and lone parents, because it offered help with the cost of childcare and enabled an increase in both female labour market participation rates and the number of hours worked (Azmat, Reference Azmat2014; Gregg et al., Reference Gregg, Harkness and Smith2009). The tax credit approach enshrines a willing worker model of agency. This competent and rational economic actor model assumes well-motivated and well-behaved subjects who are sensitive to the provision of financial support/incentives, for whom coercion is unnecessary. The childcare element was pivotal to ‘make work possible’ (Clegg, Reference Clegg2015; Grover, Reference Grover2016) for parents since familial needs are interdependent and paid work is contingent on access to affordable high-quality childcare. Under Universal Credit, these two very different logics are brought together under the dominance of the punitive unwilling worker model, with a loss of status and symbolic incentives for low-paid workers, to create a new ‘coerced-worker-claimant’ model of social security. Under UC, in-work claimants are subjected to job search requirements as if they were unemployed, with sanctions routinely threatened and applied more widely and frequently than under JSA (Adler, Reference Adler2018; Webster, Reference Webster2017).

During our study, the DWP ran a nation-wide ‘In Work Progression’ Randomised Control Trial (RCT; 2015-18). Nationally, all eligible UC claimants entered the mandatory trial (DWP/GSR, 2018) in ‘Intense’ (fortnightly JCP appointments with mandatory actions), ‘Moderate’ (Work Search Reviews every eight weeks with mandatory actions), or ‘Minimal’ (a phone call with a Work Coach every eight weeks and voluntary actions) support groups. All options carried some risk of sanctions. The RCT ‘did not find any evidence of a statistically significant impact on self-reported earnings among participants 15 months after they started the trial’ (DWP, 2018: 16). In fact, fewer participants reported being in work at wave two than in wave one. UC represents a watershed in the application of welfare conditionality to low paid workers, which (as we demonstrate below) represents a fundamental flaw in its design.

Methods

This micro level qualitative longitudinal study is based on an abductive research strategy that aims to understand how claimants experience, understand and respond to UC in-work conditionality. This approach is designed to:

‘produce social science accounts of social life by drawing on the concepts and meanings used by social actors and the activities in which they engage’ (Blaikie, Reference Blaikie1993 :176).

The data were generated as part of the first major independent study (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Meager, Bertram, Corden, George, Lalani, Metcalf, Rolfe, Sainsbury and Weston2013)Footnote 3 into the efficacy and ethicality of welfare conditionality (www.welfareconditionality.ac.uk). Central to the study was a large scale (n 481) three-wave repeat qualitative longitudinal panel study (Corden and Millar, Reference Corden and Millar2007) conducted with diverse groups of welfare recipients subject to conditionality between 2014 and 2017 in 11 sites in England and Scotland. This article draws on data from 58 purposively sampled UC recipients (30 of whom were working at one or more interview). Recruitment was attempted through all identifiable organisations in contact with UC claimants (including JCP) in the selected geographical areas of ‘live service’ – in or near Bath, Glasgow, Inverness and Manchester. Most participants were accessed via local support agencies, such as job clubs, housing or advice agencies.

68% of the sample were male; 32% female. Most were social tenants (85% at Wave A) and single without dependants (at Wave A four were coupled; six had dependent children, including two lone parents). Eight reported disability at Wave A, increasing to 11 at Wave B and 15 by Wave C. Participants were aged between 19 and 60, distributed evenly across the age range, except for the larger 46-55 category (21 people).

Detailed semi-structured interview schedules were designed to explore claimants’ circumstances and experiences of UC and looking for work. Interviews lasted between 50 and 120 minutes. The 141 transcripts were analysed using two layers of coding. First, to maximise analytical consistency across the wider sample and over the three waves of data collection, attributes were assigned and a shared framework matrix coding schema produced longitudinal summaries for each participant, including all waves, linked to the original transcripts (Corden and Nice, Reference Corden and Nice2007; Lewis, Reference Lewis2007). The framework matrix was developed by a subset of the research team (including ourselves), based on a mix of pre-emptive concerns (e.g. efficacy/ethics) and key themes that emerged from close reading of selected transcripts. Second, more detailed UC-specific thematic coding (Mason, Reference Mason2002) was undertaken by the authors using QSR NVivo software.

The retention rate was 69% overall with the following rates of attrition: Waves A-B 20% (12 participants), Waves B-C 15% (6 participants). Attrition occurs for a range of reasons (Neale, Reference Neale2019). Within qualitative studies “unlike [in] quantitative longitudinal research, weighting factors cannot be applied to ‘correct’ for any biases in the achieved sample and even a small number of ‘lost’ respondents can equate to a large percentage of the original sample” (Farrall et al., Reference Farrall, Hunter, Sharpe and Calverley2015 :287). Such attrition may potentially distort the sample, and any subsequent analysis undertaken may favour a more positive or negative reading of the remaining participants’ experiences, arguably undermining the robustness of the evidence presented (Desmond et al., Reference Desmond, Maddux, Johnson and Confer1995). We cannot speculate on the reasons for attrition. However, a review of the employment statuses of those who were retained indicates high proportions of ‘in work’ UC claimants across all three waves (i.e. 29% of the sample at Wave A, 43% at Wave B and 38% at Wave C). Given our purposive sampling strategy we do not claim statistical significance for these figures.

Findings: in-work Universal Credit and counterproductive conditionality

In this section, we identify three examples of interconnected conditionality mismatches to illustrate three UC design flaws: 1) the imbalance between heavy sanctions and unassured employment outcomes; 2) the incompatibilities of rigid conditionality requirements and flexible employment; and 3) the disconnect between promises to make work pay and enduring in-work poverty.

Mismatch one: the imbalance between sanctions and employment outcomes

There was an imbalance between heavy sanctions, often disproportionate or unconnected to rule-breaking, and unassured employment outcomes. The punitive character of UC was the striking feature that emerged from most recipients’ accounts of using the system throughout all waves of the study. Five in-work UC interviewees experienced a sanction over the course of the research (in addition to 30 of the broader UC sample who were sanctioned). Working claimants were usually sanctioned for late or missed non-negotiable appointments or not meeting job search requirements, including cases where job search was done, but not recorded to the satisfaction of a work coach. In several cases, sanctions were a result of miscommunication or administrative error. Sanctions were often experienced by working claimants with shock and a palpable sense of injustice.

Even amongst those in-work claimants who had never been sanctioned, the threat of sanctions was routinely reinforced and loomed forebodingly in their minds as it did for out-of-work recipients. Misrecognition was core to the experience of in-work UC conditionality. Willing workers, whose conduct was compliant and respectful, were treated like miscreants, which was demoralising:

‘Constantly on your case, constantly trying to sanction you. It’s an absolute nightmare.’ (Jan, 42, WA working full-time; WB working part-time; WC working full-time)

[Y]ou feel like a criminal. I’ve always worked and so I think I should have been treated a little bit differently rather than just being stuck up as another unemployed person… I’ve gone to food banks twice… I can’t keep doing that… I mean Christmas I had no electric, no gas.’ (Andy, 54, WA working part-time; WB out of work disabled; WC out of work disabled)

23 of the in-work UC interviewees were aged 50 or over, most had been employed for several decades. Encountering the UC system for the first time as an in-work claimant could be almost incomprehensible, from the idiosyncrasies of the on-line claims process (involving elusive ID numbers and struggles to obtain proof of long-standing rental agreements), through the long wait for initial payment (up to 10 weeks for some, usually involving a missed rent payment) to the unfamiliarity of visiting a security-guarded JCP office where the prospect of losing everything, including their home, was raised as a potential consequence of any minor slip-up.

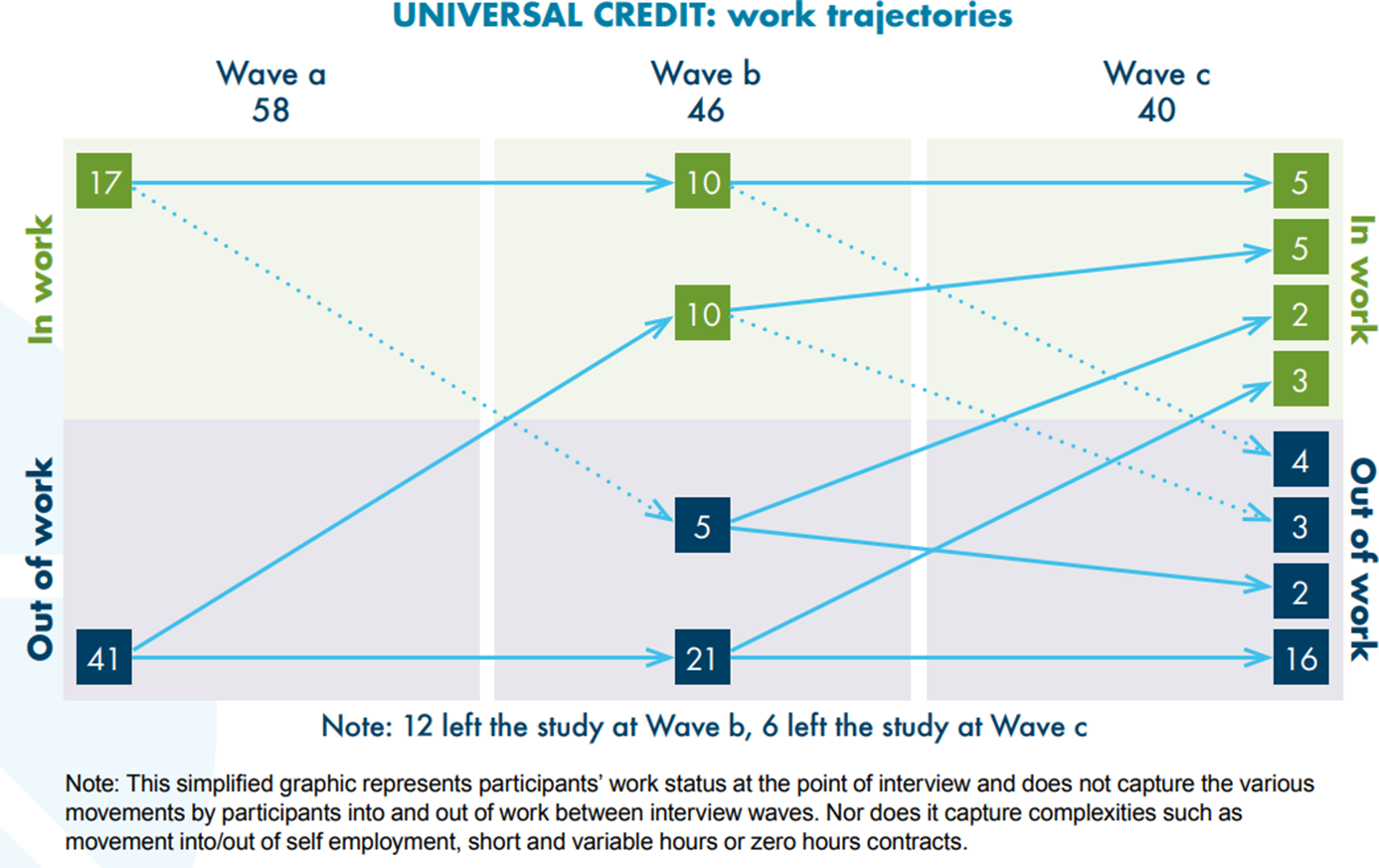

Figure 1. Universal Credit Work Trajectories (Waves A-C)

‘The whole sort of set up was absolutely new and because of my anxieties, and my depression…I just sat and listened to them waffle on… I know there’s a mandate… that they’ve got to get these benefits cut and to me it was if like I’m signing up to prison or something… Whatever they were saying didn’t make sense.’ (Andy, 54, WA working part-time; WB out of work disabled; WC out of work disabled)

Sanctions had the same overwhelmingly negative effects for in-work claimants as for those out of work, including widespread stress and anxiety, hardship, debt, rent arrears, fear of eviction, feelings of shame and worsening of mental and physical health conditions. However, the breadth and depth of the suffering caused by the threat and application of sanctions was not matched by employment outcomes.

Across the three waves of the study, UC interviewees demonstrated constant and concerted job seeking activity. However, the overall picture of job outcomes was relatively neutral (see Figure 1), with similar numbers moving into work (15) as losing their employment (12). There was broad consistency in the proportion of the sample who were in paid work throughout the study: Wave A, 29% of the sample (17) were in work; 43% (20) at Wave B; and 38% (15) at Wave C. Approximately half of those who completed all three waves changed employment status during at least one wave. Only five of those who started the study in work completed all three waves in work. Paid work remained elusive and transitory, more like a moving target than a final destination. UC creates a new conditionality mismatch between strong sanctions (with associated ill-effects), unrealistic job expectations and unrealised employment outcomes.

Mismatch Two: inflexible Universal Credit and the flexible labour market

The second mismatch was the contrast between the rigidities of the UC system and employer requirements for a flexible workforce. Foundational to how UC operates is the requirement that in-work recipients must strive for ‘progression’ to full-time work with earnings above the stated conditionality threshold. Subsequently, individuals were required to agree a Claimant Commitment identifying steps to increase the total numbers of hours they work, seek increases to pay and/or take on multiple jobs. The Claimant Commitment is presented formally as a process whereby claimant and work coach negotiate an appropriate pattern of job search activities that fit with capabilities and existing informal care commitments (DWP, 2010a/b). However, in-work UC interviewees mainly experienced their Claimant Commitment as coercive rather than contractual:

I was being bullied into doing what they wanted… I had no choice… if I didn’t sign that agreement then… sanctions’. (Greg, 50, WA out of work; WB working full-time; WC working full-time)

You just sign everything because you haven’t got any choice really. If they say to you, ‘You’ve got to agree to look for a job for 35 hours’ you can’t turn round and say, ‘No I’m not’ because you’re getting off on the wrong foot. They’re going to straight away think ‘We’ve got a problem here. We’ll get on his back.’ (Sandy, 50, WA working part-time; WB working full-time; WC working full-time)

In-work UC interviewees were usually mandated to undertake their contracted hours at work and then fill the rest of their ‘working’ week up to (and in some cases beyond) 35 hours, with largely ineffectual job search or work preparation activities. In periods of unemployment, non-negotiable full-time job search was the norm. When employed part-time, job search hours were adjusted. Many interviewees highlighted insistent compulsion to seek further hours despite holding jobs with fluctuating hours.

‘Since I’ve been doing this UC it’s so much worse… [I]f you work for 20 hours a week in a job you’ve still got to do another 15 hours searching to make your wages up… Yes, I can work full-time if the work is there but there are zero-hour contracts where I don’t know if I’m working until the day before.’ (Adrian, 57, WA self-employed; WB informal work; WC out of work),

Several in-work claimants also reported that their work coach insisted they accept zero hours contracts:

‘They said to me when I first signed on, ‘Would you do a zero-hours contract?’ I said, ‘Well what if I say no?’ She said, ‘We’ll sanction you, you won’t get any money.’’ (Mark, 52, WA out of work, WB working full-time; WC working full-time)

‘If I don’t do up to 30 hours in that other time I’ve got to look for a job and I’ve already got a job which is a bit stupid, because the hours will go up in time. It’s just when you’re first starting. I’m on a zero hour contract.’ (Samantha, 27, WA working variable hours)

Most in-work interviewees felt encumbered by rigid pre-set JCP appointments to prove that they were working and seeking more work, which undermined their ability to work flexibly. Several called to attend the Jobcentre at short notice incurred a sanction, ironically for going to work; others chose to abandon their UC claim.

I was working at the time… ‘We’re going to charge you £10 a day for seven days’ and I said, ‘What, you’re going to fine me £70 for missing an appointment that I couldn’t even ring you to tell you that I’d be late? (Sue, WA unemployed; WB self-employed; WC unemployed)

I rang them because I’m not going to skip out of work just to go for a bloody interview… I couldn’t come in because I was working full-time. So, they said that was all right. Then I got a letter saying I’d missed my interview and they’ve taken me off Universal Credit. So, I thought … just stuff you. I can’t be bothered with them anymore… So, basically, mostly I’ve struggled. (Shelley, 42, WA working full-time; WB working part-time; WC working full-time)

One man had to forgo hours at work to attend mandatory Jobcentre appointments, meaning conditionality directly prevented him from working:

‘I’m still getting letters and being called into [Jobcentre] on Friday. […] Even though they know I’m in work. […] It’s one of those […] compulsory ones again, and if I don’t attend it I’ll probably end up in trouble […] [S]o I won’t be able to work on Friday again.’ (Craig, 46, WA, working part-time, WB out of work)

Ironically, in-work conditionality reduced many UC recipients’ opportunities to engage with paid employment. Fearful of benefit sanctions, interviewees regularly focused on meeting mandatory requirements even when such actions clearly would not help them secure further employment. Several in-work recipients reported being instructed to apply for posts for which they had no realistic chance of being hired: for example, a non-driver felt it was ‘insanity’ (Paul, 46, WA working full-time; WB out of work; WC out of work and disabled) that his work coach required him to apply for an HGV driver vacancy. Another interviewee said:

I was looking for jobs that I had no training in… I’ve never worked in a kitchen … ‘Have you got any experience?’ ‘No’ ‘Well sorry’… They wanted to get me a job in a care home. I’m like, ‘They wouldn’t give me a job in a care home’. ‘Well ring up for it and I’ll be checking’ but the first thing I said to the woman was, ‘I’m going to have to tell you the truth I’m not long out of prison’ and she said, ‘Well we can’t employ you ‘… [My] job advisor was saying, ‘Apply for it just so I can see you’re applying for jobs’. (Nick, 50, WA working part-time; WB working full-time, WC working full-time)

This regular application of compulsory full-time employment/work search established a counterproductive culture of compliance that impeded more meaningful and effective attempts to secure further employment. Rather than helping people into work, or supporting in work ‘progression’, the consensus amongst interviewees was that priorities had changed:

It’s not a Jobcentre; it’s a sanction centre. (Ben, 19, WA out of work; WB working short hours)

Consequently, both claimants and work coaches become engaged in an absurd bureaucratic ritual where jobs are applied for and boxes ticked, but meaningful outcomes were rare. Some claimants even spoke in terms of job search, rather than entering employment, becoming their full-time occupation. For example,

My job was solely to prove to that woman that I had applied for so many jobs, and that was it…Whether they were suitable for me, whether I was suitable for them, whatever, it didn’t matter. (Mark, 52, WA out of work, WB working full-time; WC working full-time).

They said, ‘Oh well you need to have an interview because you’re starting back to work’. I said, ‘Well I’m starting back to work. I don’t need to see you’. They said, ‘Well we always have a meeting’. I said, ‘I’m busy. I’m working. I’ve no time to come and see you. You should be happy. (James, 50, WA self-employed; WB out of work; WC self-employed)

However, the costs of this flexibility mismatch were borne by claimants who were continually pressurised financially and psychologically, sometimes to breaking point. Despite working and intensively looking for more work, Sarah felt trapped in a limbo void of income or hope:

‘I’ve had enough. Is there any use in me working casually because it’s messed up so many appointments to have so many sanctions? And because I’m on nought, nought, nought… whatever I do work then gets deducted the month after out of my wage… I was told obviously if you lose your job, you’ve made yourself out of work voluntarily, so then my benefit stops anyway… I’m not getting anywhere with anything at the minute and I’m trying my hardest to find full-time work… They’re not offering any training or anything… I just thought ‘everything has just fallen apart now, I can’t do any more’. I’ve got bailiffs here, I’m booked in for work sometimes and they’ve knocked me back…[I]t wears you out.’ (Sarah, 30, WA working variable hours)

Ultimately, some interviewees chose to disengage entirely from UC and relinquish their entitlements to in-work wage and housing supplements, rather than continue to face the stress and pressure placed on them to seek more hours or better paid work.

‘Because the hassle of it, the grief of it isn’t worth anything. … for what it causes me stress-wise, I’d rather be without it… I don’t like the way that they treat you, we’re just numbers, animals. They don’t see you as anything else.’ (Craig, 46, WA, working part-time, WB out of work)

Whilst some interviewees found variable monthly UC payments helpful, altering in line with fluctuations in their pay, none could see the sense in the rigid application of constant further job search and attendance at JCP. If sanctions-based in-work conditionality has this deterrent effect and harmful social outcomes, which we found amongst a small sample, on a large scale, disengagement may undermine many of the imagined societal benefits or cost savings predicted in the business case for UC (DWP, 2018).

In-work ‘progression’ as relentless coercion towards ‘more work’

For those who remained engaged with Universal Credit, in-work conditionality meant ongoing requirements to ‘progress’ hours of work and pay. One interviewee, Joan, was in her 60s and had been a cleaner for eight years before claiming UC. She had arthritis and depression (since being widowed a decade ago) and lived in social housing with her son. At Wave A, she was confused about how UC worked but pleased to receive a variable monthly UC payment alongside her fluctuating wages to help with housing and living costs. When her working hours decreased, Joan’s work coach requested she looked for more work.

She [work coach] wants me to work 30 hours, just see if I could just get another one [job] to top up the hours…. I mean they don’t pressure me, she’s very good… She knows my problems with my health and that. So, they seem quite happy… She’s more like a friend really… because she’s a similar age to me, so it’s nice [laughs]. (Joan, 59, WA working short hours; WB working short hours; WC working part-time)

However, at Wave B, a different picture emerged. Unannounced, Joan had received no monthly UC payment due to deductions for a crisis loan repayment and an unexpected local authority lump sum recoup of long-standing rent arrears. A new work coach began pressuring Joan to find more work without sympathy for her financial situation or ongoing struggle to manage mandatory online job search due to a lack of IT skills.

A nightmare… I got myself in a little bit of difficulty with the rent, they said that they’d take the money out of my Universal Credit…. [T]hey took everything out. I didn’t have a penny… So, it was really difficult… That horrible lady said that if I didn’t sort things out she was going to sanction me, but she didn’t… She put down that it was a warning of a sanction… She spoke down to me as if I was a child… With not being well… it has not helped… But I’ve not stopped work. I’m still working. (Joan, 60, WB working short hours; WB working short hours; WC working part-time).

Joan continued to attend required fortnightly Jobcentre meetings and was reliant on her son’s help to complete her online job search requirements. Throughout the two-year period when we interviewed Joan, she worked continuously and held down between three and five part-time cleaning contracts concurrently. At Wave C, Joan had five jobs and was working full-time (34 hours a week), but was still required to seek more hours, under threat of sanction, despite her ongoing impairments.

If you don’t go [to the Jobcentre] … you get in trouble but I always go. I never let them down. She [work coach] said that I’m supposed do 40 hours. I tried to explain… at my age I really wanted to slow down a little bit. One job… she sent it to me on my email thing, but when I explained to her… I still had the job at night. I work half past 4 to 6, and she said this was 5 until 12 at night. I said ‘12 at night, I can’t’ – can you imagine at midnight? I mean it’s bad enough in the morning but midnight?…It was quite a good walk from here. She said ‘it’s walking distance’. (Joan, 61, WA working short hours; WB working short hours; WC working part-time).

Although Joan’s hours of work increased over the three waves of the study, she experienced these work requirements as unrealistically high. She had demonstrated a commitment to paid work by being in work long-term. The variations in her hours over time are indicative of the low-paid flexible labour market in which she works. For Joan, in-work conditionality never led to ‘progression’ in the sense of gaining better quality work, a more senior role, higher pay, improved skills/qualifications or career development. Like many women of her generation and class background, Joan was stuck in low-paid, unskilled work. UC added cruel and constant pressure to take on more work. UC coerces working claimants into time-consuming unproductive job seeking. Ingold (Reference Ingold2020: 236) found that ‘conditionality led to employers receiving large numbers of unsuitable and unfiltered applications with associated negative resource impacts’. Similarly, Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Berry, Rouse and Whittle2019: 2) found that UC in-work conditionality reduced productivity and created unnecessary costs for employers, who considered it ‘a hindrance to workforce flexibility’. Together, these findings suggest that UC promotes dysfunctional job matching activities, which are far removed from the mathematical purity of optimal search conditions assumed in economic modelling of job search theory (cf. Faggian, Reference Faggian, Fischer and Nijkamp2014).

Mismatch three: the promise to ‘make work pay’ and persistent in-work poverty

In setting out their initial vision, the UK Coalition Government promised fundamental welfare reform that would:

Ensure that work always pays and is seen to pay. Universal Credit will mean that people will be consistently and transparently better off for each hour they work and every pound they earn (Duncan Smith, in DWP, 2010b :1).

The in-work poverty that UC generates for many recipients indicates systemic failings of its underpinning assumptions (Millar and Bennett, Reference Millar and Bennett2017). The reality for most of our interviewees was ongoing and worsening poverty and debt. Inadequacies in both rates of pay at the lower end of the labour market and meagre levels of benefit combined to trap people in poverty which participation in paid employment did not solve:

‘I kept reading these things that with Universal Credit you’re better off in work… [I] couldn’t live on the money … I was actually better off on the dole and giving the work up which I didn’t want to do… I was actually about £40 worse off working.’ (Colin, 50, WA out of work; WB working variable hours; WC working variable hours)

Most in-work UC interviewees continued to live in poverty, even when working full-time, and struggled to pay their household bills and survive month-to-month. Whilst some reported UC gave ‘smoother’ (Simon, 21, WA out of work; WB employed variable hours) income when moving in and out of work, others found it ‘hit or miss’ (Cameron, 31, WA working part-time; WB out of work; WC out of work) or had long periods without any income:

‘I’m only earning £8.50 an hour, which is not a lot of money when you’ve got rent and this and that. Then you go back on the benefits and you might not get paid for six weeks – which is what’s happened to me twice. The first time it happened it was like three months. It was like I was forgotten. [Y]ou think: ‘oh God! What am I going to do?’ (Jane, 51, WA out of work; WB self-employed; WC out of work)

The long wait for first payment created a financial shock that was very difficult to recover from. Discretionary Advance Payment loans do not fix this problem because many applicants are refused (Stinson, Reference Stinson and Dwyer2019), with about half of all new UC claimants receiving advances (DWP, 2017). Because the advance is repayable, this stores up trouble for claimants who face a prolonged period of insufficient and reduced income because of deductions:

‘Bankrupt through the council because of Universal Credit putting me in arrears… So, I had to go to foodbank and I had to phone the welfare to get some money to help me for that week. I keep having to do it because I’m getting £220 to live off for a whole month… Because they’re taking the money that I borrowed last year off, £41, plus a bill that’s come in through eight years ago from DWP when I first moved in and I thought that was wiped. They’re taking money off there and then they’re taking another £48 off every month because I’m in arrears with my rent.’ (Cameron, WA working part-time; WB out of work; WC out of work)

Existing debts continued to accumulate on entering low-paid employment and were compounded by three further significant changes that UC introduced. First, many struggled following the switch from fortnightly to monthly payments (at below-poverty rates). Second, payment of the housing element of UC directly to the claimant in combination with the lengthy waiting period for initial payment, significantly increased rent arrears for many in-work claimants. Third, many struggled with the unpredictability of variable monthly payments, paid in arrears, on an assessment date that is often out of synch with wage and rent payments. Problems persisted.

‘I literally didn’t have any payments for six weeks because I’d earned over the threshold and I’d gone into that month. My month goes from the 17th to the 17th so that’s how they judge you; you’re always judged on those months. Then, ‘Oh well, you’ve gone over your threshold so we can’t pay you now for another six weeks’. So, it’s like, oh fucking hell!’ (Jane, 51, WA out of work; WB self-employed; WC out of work).

Paul’s (below) full-time wages alongside his UC payment came ‘nowhere near’ the cost of his council tax, rent, utilities and food. Many were reliant on support from family friends to meet their basic needs. Some were in dire circumstances. Paul had a previous long-term history of full-time work but was made redundant. At first interview, he was very critical of UC, the lack of support and an ineligibility for benefit due to his previous redundancy payment, which would not have affected his eligibility under the previous tax credit systemFootnote 4 . His last experience of claiming out of work benefits was two decades previously, and although he was working part-time, when we first interviewed him, he spoke of ‘feeling criminalised’ by claiming UC:

‘I’ve had to go out and go to a food bank and I’m working 40 hours a week and that was before I was getting overtime…How embarrassing is that?… That is wrong. (Paul, 46, WA working full-time; WB out of work; WC out of work disabled)

Fear of eviction due to rent arrears and a constant struggle to manage financially had a negative impact on Andy’s mental health. Unable to cope, he set up a campsite on wasteland and slept rough because his situation overwhelmed him.

‘I’ve been taken to court for rent arrears… This is what took me to the river, anxiety and my own depression… This week I got paid £145, out of that I’ve got to pay a week’s rent, £95 something, right, so it’s basically £100. So, then you’ve got £45. I’ve got to pay gas and electric to keep my flat going, which I very rarely buy any of that, only electric… I try and do without the gas, which is not good for my health, not good for the state of the flat because it’s mouldy… I can’t afford it. … With all the other bills like water rates, I’m £2500 in debt with them, I’ve got rent arrears and just trying to sort of like survive, I can’t do it on my weekly payments… I’m doing about 28 hours but I’d like to do more but I can’t… because I can only work if the employer tells me to. So, I’m stuck on these small hours.’ (Andy, 54, WA working part-time; WB out of work disabled; WC out of work disabled).

At Wave B, Andy had acute depression and was no longer working. A housing support worker intervened to prevent eviction and rationalise his debts through a Debt Relief Order. He developed a serious physical illness and was on medication for chronic anxiety and panic attacks. Waiting for a Work Capability Assessment, his work coach still made contact but the pressure to find work had eased. Nonetheless, Andy was perplexed, reasoning ‘If I’m ill, why have I got a job coach?’. By the third interview Andy’s health had deteriorated further and he had moved into supported accommodation. Whilst bedridden, healthcare workers had helped him to successfully apply for a Personal Independence Payment. This meant an end to job search requirements. There is clear mismatch between the original promise to make work pay and the enduring persistence of poverty for many in-work recipients.

Conclusion

In this article, we have assessed how the welfare conditionality inherent in UC affected the lives of claimants. We found that combining out-of-work benefits with in-work earnings top-ups involved a culture clash of policy assumptions. Under UC, two contrasting policy logics are combined under the dominance of the punitive ‘unwilling worker’ model that traditionally governs unemployment assistance schemes. Rather than incentivising progression within paid employment or further engagement with work, UC is deterrence-based, with stigma, low value payments, coercive support and punitive sanctions designed to repel ‘dependency’. For low-paid and part-time workers, in-work UC represents losing the status and symbolic inclusion that tax credits previously offered via respectable and enabling earnings top-ups, based on a ‘willing worker’ model of competent agency. The result is a new and unique ‘coerced worker claimant’ model of social security, that threatens and applies exceptionally harsh penalties more widely and frequently than JSA did before it. UC is different from previous generations of social security in its comprehensive application of standardised forms of welfare conditionality, to both ‘in work’ and out of work claimants, across the whole social assistance population.

We identified a set of mismatches that reveal UC design flaws. Punitive sanctions were mismatched with unassured employment outcomes and in-work sanctions were experienced as unjust. Despite concerted job seeking activity, most experienced paid work as elusive or transitory, more like a moving target than a final destination. Rigid Jobcentre attendance requirements and high job search expectations were at odds with employers’ needs for variable availability and quick response. ‘In-work progression’ was experienced simply as pressure to take on unrealistic amounts of ‘more work’ (extra hours or multiple jobs), without improvement in the quality or duration of employment – producing a coerced flexible workforce, continually in fear of losing their income and homes. This impacted detrimentally on the physical and mental health of several in-work claimants. Some relinquished their entitlement to UC and closed their claim, despite ongoing insecure employment and enduring poverty. Others continued to claim but were increasingly distressed by unrealistic work and job search requirments. Although being ‘better off in work’ was a prime justification for Universal Credit, we found many examples of claimants being financially worse off in employment and in-work poverty was rife. In the absence of effective financial work incentives, UC was experienced as predominantly punitive. In-work UC sanctions were easily triggered, rapidly escalating and long-lasting. Taken together with employers’ experiences that UC conditionality overburdens recruitment processes with large numbers of unsuitable applications (Ingold, Reference Ingold2020; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Berry, Rouse and Whittle2019), our findings indicate that UC stimulates dysfunctional job matching practices, which bear little resemblance to the assumptions in economic modelling of job search theory (cf. Faggian, Reference Faggian, Fischer and Nijkamp2014) and impair productivity.

These findings demonstrate a fundamental flaw in the design of UC for working claimants. In removing the cliff-edge of benefit withdrawal long-criticised for creating unemployment benefit traps, UC creates a new problem. As the old distinction between low paid work and unemployment disappears, there is greater ambiguity about job search conditions, deeply embedded internationally in all unemployment assistance schemes, but which have never been used for tax credits. Our findings suggest that in-work conditionality requirements for UC should be removed because they are ineffective, do not further improve pre-existing motivations to work (DWP, 2018) and are socially damaging. Instead of treating workers as if they were unemployed, by threatening devastating sanctions and stimulating copious ineffective job applications, UC should operate as an ‘employment-conditional earnings subsidy’ (Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy2015:4) without additional conditionality.