Introduction: theoretical and research basis for the treatment

Specific phobia of vomiting (SPOV; also known as emetophobia) is a severe and debilitating anxiety disorder, causing high levels of distress and having a profound impact on sufferers’ lives. It is a type of specific phobia most commonly defined by a fear of oneself vomiting, although a diagnosis can also encompass a fear of other’s vomiting (Price et al., Reference Price, Veale and Brewin2012). Sufferers go to great lengths to avoid this risk, for example restricting consumption to ‘safe foods’, extensive avoidance and planning of situations, monitoring of interoceptive cues that feel linked to nausea or scanning for illness cues in others, together with a range of other highly impairing safety-seeking behaviours (van Hout and Bouman, Reference van Hout and Bouman2012; Veale and Lambrou, Reference Veale and Lambrou2006). SPOV has a population prevalence of approximately 0.1% (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Rinck, Turke, Kause, Goodwin, Neumer and Margraf2007) but this may be an under-estimate due to misdiagnosis caused by its superficial resemblance to eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and other difficulties (Veale, Reference Veale2009). Onset usually occurs during childhood (Lipsitz et al., Reference Lipsitz, Fyer, Paterniti and Klein2001) and is often associated with early traumatic childhood memories of vomiting (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Murphy, Ellison, Kanakam and Costa2013b).

Four times more females than males are diagnosed with SPOV (Lipsitz et al., Reference Lipsitz, Fyer, Paterniti and Klein2001; van Hout and Bouman, Reference van Hout and Bouman2012), and the problem often has an early onset, therefore affecting many women of childbearing age. Given the association between pregnancy and increased risk of vomiting (Lacroix et al., Reference Lacroix, Eason and Melzack2000), most severely in the form of hyperemesis, women with SPOV may avoid, delay or even terminate pregnancy for this reason (Lipsitz et al., Reference Lipsitz, Fyer, Paterniti and Klein2001). Furthermore, the care of young children often involves exposure to their vomit, either due to reflux or the child contracting contagious pathogens such as norovirus (Hutson et al., Reference Hutson, Atmar and Estes2004). Early caregiving may therefore present particular difficulties for parents with SPOV and may start to directly impact on children via modelling or avoidance. In their study, 70.8% of respondents reported asking children to wash hands excessively as a result of their own fears (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Hennig and Gledhill2015). This can be an area of concern for parents who are worried about the impact on children who may pick up on and start to copy their behaviour independently (Gerull and Rapee, Reference Gerull and Rapee2002).

Anxiety symptoms and disorders are common in the perinatal period, with phobias as a group thought to affect approximately 8% of women (Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Janssen, Antony, Tucker and Young2016; Nath et al., Reference Nath, Busuulwa, Ryan, Challacombe and Howard2020). Phobias particularly relevant to the perinatal period, namely tokophobia, blood-injury phobia and SPOV may cause more sustained levels of anxiety for women during this time. Persistent prenatal anxiety has been associated with more difficult infant temperament and increased frequency of crying and feeding difficulties in the postpartum period (Field, Reference Field2018; Thiel et al., Reference Thiel, Iffland, Drozd, Haga, Martini, Weidner, Eberhard-Gran and Garthus-Niegel2020). Postpartum anxiety can impact on aspects of parenting and the mother–infant relationship, via depressive symptoms, pre-occupation, avoidance or other limitations to functioning caused by the problem (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2016; Reck et al., Reference Reck, Tietz, Müller, Seibold and Tronick2018; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Craske, Lehtonen, Harvey, Savage-McGlynn, Davies, Goodwin, Murray, Cortina-Borja and Counsell2012). Both biological and environmental mechanisms have been implicated in the associations between perinatal anxiety and the raised risk of emotional and social problems in children throughout childhood (Capron et al., Reference Capron, Glover, Pearson, Evans, O’Connor, Stein, Murphy and Ramchandani2015; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Hill, Hellier and Pickles2015). Early and effective treatment of anxiety disorders during the transition to parenthood is therefore important to improve quality of life for the woman and reduce the risk of impact to the child (Aktar et al., Reference Aktar, Qu, Lawrence, Tollenaar, Elzinga and Bögels2019).

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) including in vivo and/or imaginal exposure can be an effective treatment for SPOV (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Gilpin and Veale2018), although there is scope for further improvement: half of participants achieved clinically significant change in a small trial of 24 participants (Riddle-Walker et al., 2016). Seven out of eight participants improved using a time-intensive delivery of CBT including rescripting of early images (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Deale, Foster and Veale2020). The importance of addressing early memories or intrusive images of vomiting in some form may therefore be an important addition to the CBT approach for SPOV (Price et al., Reference Price, Veale and Brewin2012; Veale et al., Reference Veale, Murphy, Ellison, Kanakam and Costa2013b). However, there is no specific literature on how to take these factors into account in the the impact of SPOV on parenting, or documenting the treatment of this problem at this time. Parents often feel very guilty about the potential impact on children and this needs to be carefully assessed and worked with in therapy. The current paper outlines the treatment of two mothers of young children using CBT, highlighting parenting-specific issues that arose in treatment and how these were conceptualised and treated.

Case material

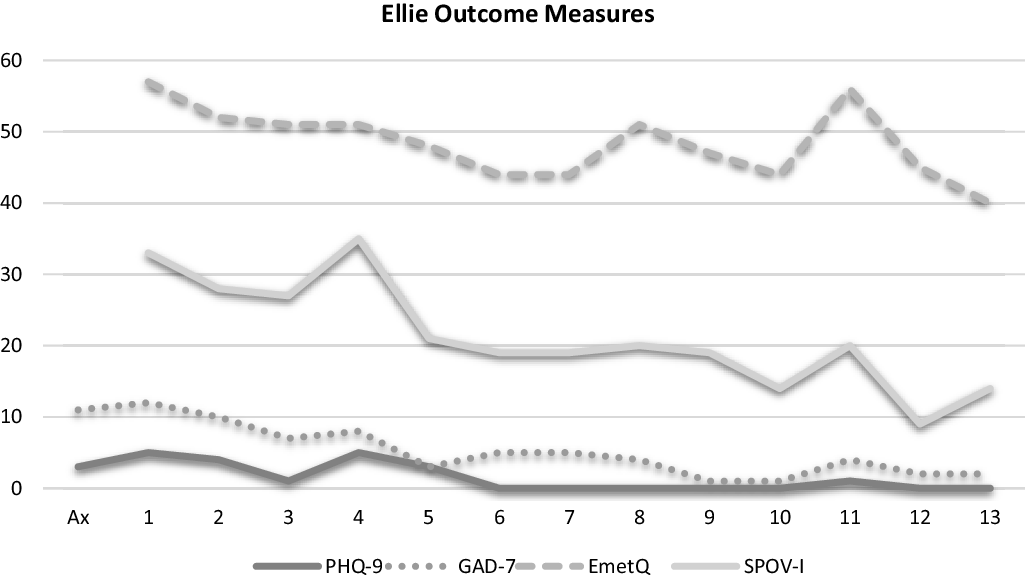

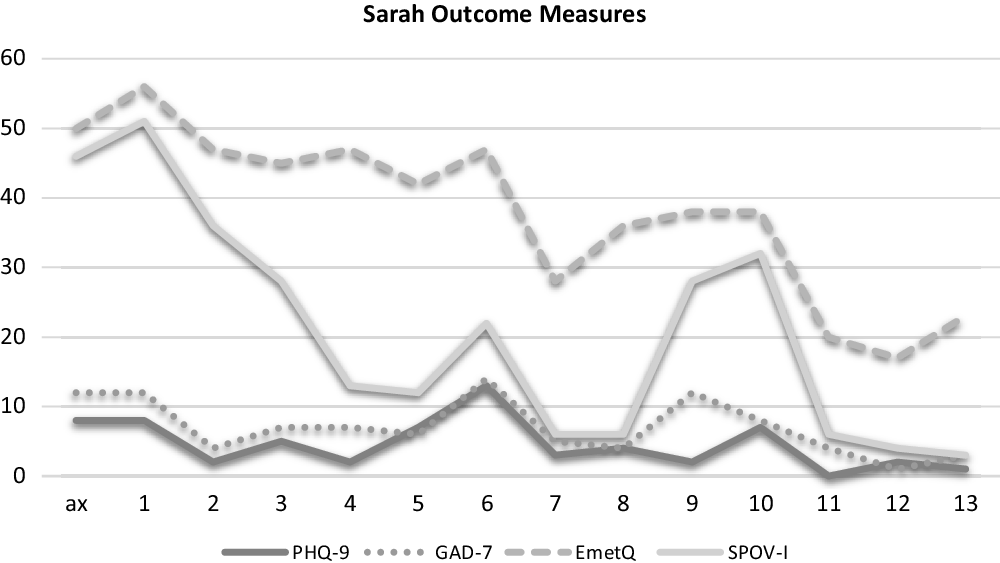

For each person, symptoms of general anxiety and depression were monitored weekly using validated measures of depression (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) and anxiety (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). On the PHQ-9, a score of 0–4 indicates no depressive symptoms, 5–9 mild depressive symptoms, 10–14 moderate depressive symptoms, 15–19 moderately severe depressive symptoms, and 20–27 severe depressive symptoms. On the GAD-7, a score of 0–4 indicates minimal anxiety symptoms, 5–9 mild anxiety symptoms, 10–14 moderate anxiety symptoms, and >15 severe anxiety symptoms. SPOV symptoms were assessed with two disorder-specific measures: the SPOV-I (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Ellison, Boschen, Costa, Whelan, Muccio and Henry2013a) and the EmetQ (Boschen et al., Reference Boschen, Veale, Ellison and Reddell2013). The SPOV-I is used to measure cognitive and behavioural processes in specific phobia of vomit. EmetQ is designed to measure the severity of fear of vomiting on a weekly basis. Scoring above 10 on the SPOV-I or above 22 on the EmetQ indicates the likely presence of SPOV.

Case descriptions

Sarah (a pseudonym) was a 33-year-old white woman who was a married mother of three (ages 3, 7 and 10) who worked in healthcare. She had felt anxious about vomiting since early childhood. She functioned reasonably well in her job by generally escaping or avoiding situations in which patients vomited. However, this was more difficult on night shifts and she attempted to cope by using safety-seeking behaviours (SSBs) such as avoiding naps on her breaks on these shifts (lest she feel nauseous when she woke) and eating only small meals beforehand. In general, Sarah was hypervigilant to signs or stories that meant she or someone in her vicinity may vomit (e.g. when she felt nauseous, one of her children seemed unusually quiet, or she heard about a patient on the ward vomiting or another family in their social network being struck by a sickness bug). Sarah employed many SSBs and avoidance strategies, described later in this paper. Sarah often felt nauseous and would attempt to reassure herself that she was not actually ill by eating ‘junk’ food such as crisps and chocolate. Sarah felt her SPOV had been gradually getting worse over the years since becoming a parent, and was aggravated with each successive child as the risk of encountering vomit increased.

Ellie (a pseudonym) was a white 34-year-old married mother of a two-year-old son and three-month-old daughter, and worked as a teacher. Ellie reported that her SPOV had been a feature of her life for as long as she could remember and recalled clear early memories of traumatic vomiting. Ellie reported her SPOV had markedly worsened after having children. She reported that her problem had affected her occupational functioning as she would have to run out of the classroom when a child was sick and leave her teaching assistant to manage it. Ellie also managed her phobia with various SSBs, which are described later in this paper. Ellie’s anxiety caused her to feel nauseous, fuelling her misinterpretation that she might vomit.

Both Sarah and Ellie had attended CBT sessions at their respective local primary care services several years prior to the treatment described in this paper. Ellie could not recall how many sessions she was offered. She stated that the therapy was moderately helpful, but she felt as if the therapist was ‘still trying to figure out the problem’ by session 4 or 5, and there was not much exposure work. However, she reflected that she did resume eating chicken after this course of therapy, but did not manage to maintain this gain and had stopped eating it again within a few years. Sarah remembered that she was offered six sessions of CBT. She said that she did not find them helpful as the therapist had never treated SPOV before, and she became pregnant during the treatment, which helped as she had a non-threatening explanation for nausea.

Both Ellie and Sarah had experienced an average amount of nausea in their pregnancies (not hyperemesis). Ellie, like Sarah, was not distressed by pregnancy nausea as it had a clear and non-frightening explanation. Both were particularly anxious about vomiting bugs.

Parenting-specific issues

Sarah felt anxious to be alone with the children at night lest one of them vomit. She reported monitoring them constantly for signs of sickness, becoming worried at any perceived change in their mood, how much they ate at meals, or their bowel movements. Sarah reacted to this anxiety by repeatedly asking her children if they were OK and how they felt, which she reported irritated them and made them more likely to keep any feelings of illness from her and seek comfort from their father instead. This made Sarah feel upset and guilty and concerned about the impact of her anxiety on them. Furthermore, Sarah was often frightened by hearing about other children attending school sick and interrogated her children about their contact with the unwell peer when this occurred. Sarah also reneged on commitments to care for friends’ children if she heard they had recently been ill. On the occasions Sarah’s children did get sick, Sarah avoided caring for them, relying instead on her husband or other family members. This all placed considerable strain on Sarah’s relationships.

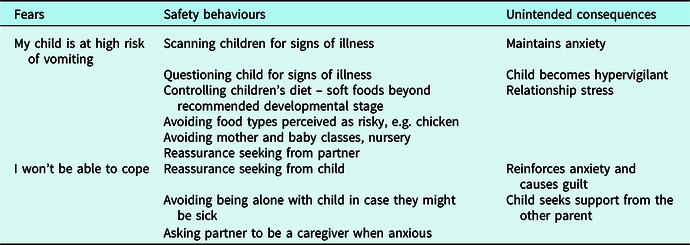

Ellie’s phobia also interfered with her parenting. She would sometimes keep her son away from nursery, would check her daughter’s temperature nightly and would ask her partner to investigate for signs of vomiting if she heard her daughter cough over the baby monitor. Ellie would not feed her daughter foods she considered a high risk of choking (such as sausages) or of food poisoning (chicken). Ellie’s anxiety centred primarily on her 2-year-old, as at the time of treatment her son was a very young baby and she did not view his milky ‘spit-up’ as akin to vomit and therefore did not find it threatening. When asked about why she was seeking treatment Ellie said ‘it’s all about [my daughter]’. However, she also expressed a great deal of sadness and regret that she had ‘missed’ being present for her son’s first few months of life as she was so pre-occupied by her phobia. Table 1 shows examples of common fears and behaviours in perinatal SPOV.

Table 1. Examples of commonly occurring perinatal fears and behaviours

Case conceptualisation

Intervention overview

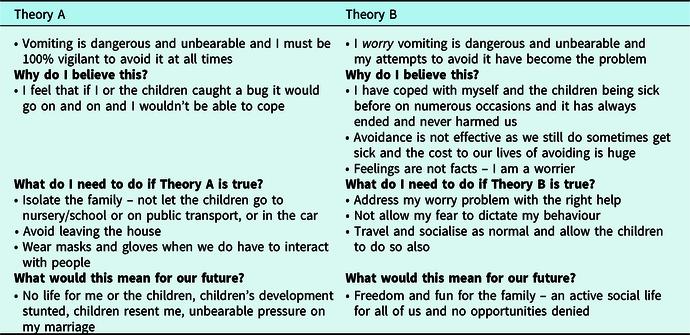

Ellie and Sarah each received 13 sessions of individual treatment delivered by a clinical psychologist in a primary care setting. Each course of treatment followed a very similar pattern. Treatment initially involved psychoeducation, developing a shared formulation of the vicious cycles maintaining the problem, reframing the problem as one of anxiety (Theory A/B technique; see Table 2), and constructing an exposure hierarchy. Imagery re-scripting of negative early memories of vomit and relapse prevention were addressed in the second half of treatment.

Table 2. Theory A/B

Formulation

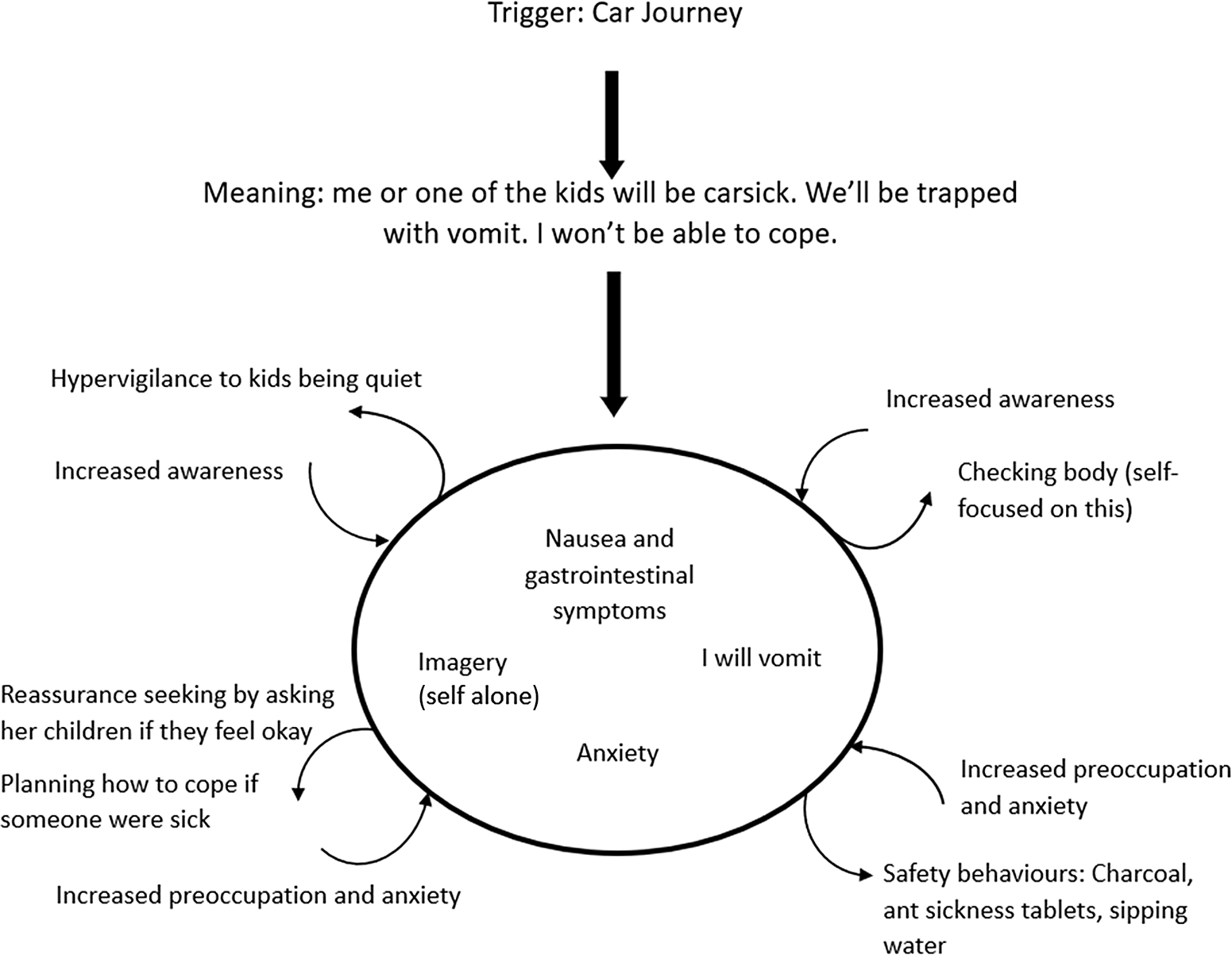

A collaborative formulation of Sarah and Ellie’s SPOV using Veale’s (2009) ‘vicious flower’ was developed in session 1 of their treatment. A recent example of heightened anxiety was used to elucidate links between their beliefs, emotions, cognitions and behaviours (see Fig. 1 for Ellie’s vicious flower). The maintaining factors were broadly similar for both Ellie and Sarah.

Figure 1. Example of formulation for Ellie.

Goal setting

Short and long-term goals were established early in treatment.

Ellie’s goals for therapy included wanting to be a ‘normal’ person who could cope with her children being sick (e.g. not sending her partner to deal with it) and not feel like the phobia was taking over her life. Ellie wanted to feel confident caring for her children alone, and to be able to look after them when they were sick.

Sarah’s goals for therapy were similar in that she wanted to be able to look after her children alone when they were sick and take them out for the day alone, without her husband. Sarah also wanted to be able to use public transport with her children.

Theory A/B

In this stage of treatment, clients are introduced to the idea of conceptualising and then treating their difficulties as an anxiety problem. Using Socratic questions, clients are asked to consider each section in turn. An example developed with Sarah is provided in Table 2.

The issue of the unintended consequences on the family of following the restrictions dictated by anxiety must be tackled sensitively. This formulation can be used by the therapist to help parents choose to tackle their SPOV and select a different future.

Exposure and behavioural experiments

Exposure hierarchies were developed with Sarah and Ellie and commenced with the help of the therapist, including exposure to images, videos and sound recordings of vomit. Exposure tasks further up the hierarchy included watching a therapist simulate vomiting in the toilet, eating expired salmon and watching other people vomit on video. Anxiety levels were monitored out of 10 during the task and scores usually reduced from the start to the end of exposure. SSBs such as reassurance that ‘the person vomiting in the picture was drunk and not ill’ were identified and encouraged to be dropped. Children were not present in therapy sessions. For homework, clients continued exposure in situations meaningful to their goals (e.g. using public transport with their child) and attempted to drop SSBs.

Behavioural experiments were designed in-session to challenge Ellie and Sarah’s beliefs regarding the likelihood of vomiting. For example, Ellie aimed to cook and eat chicken on a night her husband was away. She believed 50% that she would become ill. Ellie did not get ill, but it transpired she had overcooked the chicken by 15 minutes as a safety behaviour. Ellie was therefore challenged to re-attempt this task cooking the chicken for the appropriate time and feed it to her daughter, which she managed to do.

Further exposure tasks of watching videos of vomiting highlighted beliefs such as that the experience of vomiting was distressing for that person. This was challenged by identifying the emotional bridge with the client’s own experience, focusing on details that indicated the person was relieved, and using stimulus discrimination (a focus on the here and now) when such emotions were elicited by fears of vomiting. The videos Sarah and Ellie found most distressing were linked to their particular idiosyncratic beliefs about vomiting. For example, Ellie was very disturbed by a video of a girl vomiting off the side of a boat and felt convinced that the girl was really suffering, despite the fact that she was laughing and joking in the video. This was because the sound the girl was making was reminiscent of choking, which recalled Ellie’s early traumatic memory of feeling like she was choking and in danger of suffocation. Stimulus discrimination in this case involved Ellie clearly and repeatedly labelling her anxiety a ‘ghost of the past’ as she watched the video and focusing intently on the girl’s relaxed happy demeanour in the video and the clear signs that the girl could breathe, was not choking, was relieved by the vomiting and was finding it funny. Both women were most upset by videos of vomiting caused by illness, as opposed to people vomiting for other reasons (e.g. being drunk, or on fairground rides). Sarah felt extremely anxious about an ostensibly innocuous picture of a vomit stain on a train seat as it made her think of someone being sick in the carriage and spreading the germs around.

Steady progress was made with the exposure tasks, but high levels of emotion remained regarding Sarah and Ellie’s own fears of vomiting. Sarah identified a generalised sense of low competence. Standard techniques such as keeping a positive data log were used to help her focus on the many examples of competence and parenting self-efficacy in her life, which contrasted with her Theory A belief. This led to reframing this sense of incompetence as related to a historical experience that required updating.

Dropping subtle safety behaviours

Exposure tasks throughout treatment continued to highlight subtle safety-seeking behaviours. Sarah employed many SSBs including taking anti-sickness medication and charcoal tablets, avoiding certain types and quantities of food at certain times, avoiding food nearing its sell-by date, avoiding alcohol, cooking food for longer than necessary, scanning her body for signs of nausea, staying home if nauseous, checking her surroundings for escape routes and toilets, and planning how she would cope if she or someone in her family were to vomit. Sarah would also leave a towel on her child’s bed in case her child vomited. Discovery that unexpected feelings of nausea caused lapse into safety behaviours prompted discussion of a more realistic explanation for the nausea, e.g. that Sarah had not eaten during her night shift then over-ate when she returned home.

Ellie’s SSBs included handwashing (her own hands and her children’s), avoiding touching door handles and lift buttons (or covering her hand with a tissue or using her elbow), seeking extensive reassurance, avoiding car trips lest her daughter be sick, and constantly checking her daughter for signs of illness.

In both cases, the clients’ partners attended a session to help their understanding of how the problem worked, and to develop shared strategies to replace reassurance seeking such as encouragement and support.

Surveys

Tailored surveys were used to challenge both clients’ beliefs about the high frequency and duration of vomiting bugs in general, instead discovering that most respondents had experienced one or two vomiting bugs in their adult lives, which lasted for a comparably short period of time. These were effective in changing beliefs about the probability of vomiting.

Imagery re-scripting

Given the links between current appraisals and early experiences, the most prominent memory of vomiting was ‘relived’ to establish key meanings. These images were then ‘updated’, with the aim of processing and re-contextualising negative emotions using the protocol developed by Arntz of imagery rescripting (Arntz and Weertman, Reference Arntz and Weertman1999). Using this, the adult self is (and/or another safe and helpful adult, such as the therapist, are) brought in to provide comfort and any other action required to update the emotion of the memory. There were some similarities between Sarah and Ellie’s early traumatic memories of vomiting. For both, the trauma memory occurred shortly after their parents had divorced. In Ellie’s case, she was on an outing with her father aged 7, and felt sad and homesick as she missed her mother a lot, and did not feel comfortable or well cared-for when alone with her father. She was also highly anxious as her father had just scolded her harshly for losing an item of clothing. She suddenly vomited on the street, and felt shocked, scared and ashamed because her father seemed very embarrassed. She also had the thought that she was choking and was unable to breathe in the midst of the vomiting. Ellie’s father did not comfort her. To update the memory, Ellie relived it again but then imagined her adult self appear to comfort and look after her and take her home, and also tell off her father for letting her down in that moment. This provided a ‘corrective emotional experience’, meeting Ellie’s emotional needs which were unmet at the time, and she described it as very cathartic. She also focused on breathing through the vomiting and bringing in adult knowledge to the child’s experience, i.e. that, although it was a highly unpleasant sensation, she was not in fact choking or in any danger of suffocation.

Sarah’s trauma memory took place when she was approximately 14 (she could not remember her exact age). Her father had recently left the family, and her mother was in hospital. She was alone in the house and she and her sister fell ill with a vomiting bug. This was the first time she had not been looked after while ill, and she also felt responsible for looking after her sister despite being ill and frightened herself. Key cognitions identified in the reliving included ‘I can’t cope’ and ‘it will never end’. Sarah was surprised at how intensely sad she felt when reliving the memory. As with Ellie’s case, Sarah brought her adult self into the memory to comfort and look after her child self, and also applied what she ‘knows now’ during the memory ‘hotspots’ (i.e. she did cope, and it did end, after only a few hours). Between-session homework consisted of practice of the updated narrative and ongoing exposure and dropping of safety behaviours, including reassurance-seeking.

Outcomes

By the end of treatment, both Ellie and Sarah met the goals they set out to achieve at the start of treatment. They both noticed a ‘shift’ in their SPOV and felt happy and free to be ‘doing what everyone else does’ (i.e. no longer restricting foods).

At the start of treatment, Ellie and Sarah’s SPOV-I and EmetQ measures indicated severe symptoms. Scores on both measures reduced by the end of treatment. Ellie and Sarah’s scores on the standard primary care (IAPT) dataset (PHQ-9, GAD-7) and disorder-specific measures (SPOV-I, EmetQ) are reported below, in Figs 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Outcome measures for Ellie.

Figure 3. Outcome measures for Sarah.

Key elements of treatment

-

Empathic assessment of current impact on self and family members.

-

Case conceptualisation of individual beliefs, emotions, maintaining behaviours in present and key past experiences fuelling emotional meaning of vomiting.

-

Setting of goals (both short term and beyond therapy) – thinking about the parent you want to be.

-

Theory A/B – reframing of the problem as one of fear and reduced self-efficacy rather than threat. Weighing of evidence and pros and cons of change.

-

Development of exposure hierarchy.

-

Dropping of safety behaviours and setting experiments to challenge these.

-

Developing self-compassion and increasing self-efficacy.

-

Imagery re-scripting of key memories.

-

Increasing tolerating uncertainty, e.g. maybe my daughter will be sick.

-

Attention training to focus away from signs of illness in children.

-

Reviewing outcome measures.

-

Relapse prevention.

Discussion: treatment implications of the cases

These cases illustrate the prominence of parenting issues for new mothers with SPOV and highlight the effectiveness of CBT. Anxiety can be greatly exacerbated by the transition to parenthood and in the case of SPOV is complicated by the possibility of needing to care for a sick child in a situation that also acts as trigger for one’s own anxiety. The CBT approach to SPOV utilises many techniques which are applicable across different anxiety disorders, e.g. breaking vicious cycles of avoidance and SSBs using exposure-based behavioural experiments and discussion. The reported cases demonstrate that positive outcomes are enhanced if the full range of negative emotions present at the time of the onset of SPOV are processed using imagery rescripting. Sarah and Ellie (like many people with SPOV) were primarily aware of fear and disgust in relation to the day-to-day experience of their phobia and were surprised that the dominant affect was in fact overwhelming sadness and loneliness when they re-experienced key vomiting memories. Rescripting these memories and updating the key meanings subsequently reduced their distress and enhanced the effectiveness of exposure. These cases also demonstrate the non-linear nature of progress typical of anxiety disorder treatment. Although symptom scores dropped significantly overall over the course of treatment, there were multiple spikes in anxiety on weeks in which Sarah and Ellie had to contend with triggers (such as Sarah’s daughter’s vomiting bug). Public awareness of SPOV is low in comparison with other anxiety disorders; it is therefore likely that many sufferers are not aware that effective treatment is available. Consequently, we reproduce Sarah and Ellie’s message to other parents with SPOV considering CBT:

I found CBT very challenging, particularly emotionally. At the beginning, I struggled to explain and understand why I felt the way I did, but the treatment really helped me to understand this and validate my feelings. I still live with SPOV, but the treatment made me realise that I can deal with vomit and it is the anxiety tricking me into thinking I can’t. I try to remember this regularly when faced with a challenging situation and I’ve definitely adopted more of a ‘bring it on’ attitude, rather than running away from it.

The treatment has made me realise that my SPOV is just one flaw in my parenting. Before treatment, I wholeheartedly believed that having SPOV made me a bad/ineffective mum; I now believe that this is not the case – I know I’m a good mum and there are lots of things that I do well, this is just one area that I struggle with and continue to work on.

This time of year (autumn/winter) is usually a particular struggle for me, with the threat of sickness bugs like norovirus being more prevalent. For the first time since being a parent, I’m actually enjoying this autumn for what it is – a lovely season! Although it’s still on my mind, I’m definitely less pre-occupied with SPOV and it feels really nice to be able to enjoy this time of year with my family.

Conclusions

This paper outlines two successful cases of CBT treatment for SPOV. Veale’s (2009) protocol was followed and tailored to the specific concerns of the clients. It is relevant to note that, despite the distress associated with their symptoms, both women were functioning well in their day-to-day lives, and were not significantly anxious or depressed. Clients with SPOV who are experiencing higher levels of functional impairment, or other co-morbidities such as depression, general anxiety and self-harm, may require that these factors be addressed first before they can respond positively to a brief structured intervention such as the one outlined in this paper. The current study adds to the evidence base that CBT effectively reduces symptoms of SPOV to non-clinically significant levels in parents of young children. Although reductions in anxiety were observed on a measure of general anxiety (GAD-7), SPOV symptoms are most usefully assessed using disorder-specific measures (in this case, the SPOV-I and EmetQ). A limitation of this study was the lack of follow-up to assess whether gains were sustained. Future research could investigate if identifying and treating women before or during pregnancy could prevent difficulties in early parenting.

Key practice points

-

(1) Pregnancy and caring for young children involves exposure to vomit and thus presents particular challenges for parents with SPOV. Parental SPOV symptoms may impact directly on children due to modelling and avoidance.

-

(2) Safety behaviours centred on children should be thoroughly assessed to inform goal-setting. These can include scanning and questioning children looking for signs of illness, reassurance-seeking from children and/or partner, avoidance of being alone with children lest they vomit, avoiding contact with other people’s children (nursery, soft play, playdates, etc.), excessively washing children’s hands, avoiding car journeys with children, and controlling children’s diet.

-

(3) Treatment is underpinned by a vicious flower formulation encompassing cognitive and behavioural maintenance factors. The aim of treatment is to build evidence for a less threatening alternative view of the problem (i.e. the problem is I worry vomiting is dangerous and unbearable – it is a worry problem, not a danger problem). This is accomplished with behavioural experiments and graded exposure to vomit cues.

-

(4) Using imagery rescripting to update traumatic early memories of vomiting is a useful way to process the sadness and fear associated with these memories and update attendant beliefs such as ‘I am alone’ and ‘I can’t cope’.

-

(5) Progress in SPOV treatment should be assessed using disorder-specific measures such as the SPOV-I (Veale et al., Reference Veale, Ellison, Boschen, Costa, Whelan, Muccio and Henry2013a) and the EmetQ (Boschen et al., Reference Boschen, Veale, Ellison and Reddell2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah and Ellie for allowing us to share their stories and for their contributions to this manuscript.

Author contributions

Kimberley Orme: Data curation (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Fiona Challacombe: Conceptualization- (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Alexa Roxborough: Conceptualization- (equal), Investigation (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

F.L.C. is supported by a HEE/NIHR ICA Programme Clinical Lectureship, ICA-CL-2017-03-013.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statements

Authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Written permission was obtained from each person to write up the case studies and include their feedback, and final versions were sent for approval.

Data availability statement

No further data are available for reasons of confidentiality.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.