Introduction

At the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) crisis in March 2020, the General Medical Council set out to provide early provisional registration for final-year medical students to help deliver care at a time of extreme pressure within the National Health Service (NHS). Studies have consistently demonstrated that ENT is poorly represented on the undergraduate medical curriculum, with most final-year medical students and junior doctors feeling unprepared for clinical practice.Reference Ferguson, Bacila and Swamy1 Coronavirus disease 2019 exacerbated this issue as opportunities for learning were limited because of a requirement for senior doctors to perform aerosol-generating procedures. Major haemorrhage and airway emergencies can be anxiety-inducing, high-stress scenarios for even experienced clinicians, let alone those who are new to working in ENT.

To address these issues, we established a simulation-based platform aimed at providing a unique, safe and constructive resource for learning to improve the clinical skills, knowledge and confidence of new interim foundation doctors. The course was initially incorporated into departmental induction for first-on-call ENT doctors, followed by national expansion to reach an audience of junior doctors working in ENT across Scotland.

Method

The first iteration of the programme involved five interim foundation doctors allocated to our ENT department to help support the clinical team during Covid-19. They attended a half-day simulation study day, comprising a ‘skills and drills’ workshop focused on specialist equipment and procedural skills, followed by two interactive scenarios (tracheostomy emergencies and epistaxis). A combination of an interactive SimMan3 G mannequin, a technician utilising a Mask-Ed™ and a video flexible laryngoscope trainer along with a trained ‘confederate’ ward nurse was utilised, with the aim of delivering a high-fidelity, immersive simulation. The Mask-Ed allowed for simulation of an elderly patient as actors were unavailable during the Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it facilitated replication of a highly realistic epistaxis experience for the participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A technician wearing a Mask-Ed silicone mask with a ‘confederate’ nurse replicating an epistaxis scenario.

Participants were asked to rate how prepared they felt in managing the relevant condition before and after the course on a five-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree to 5, strongly agree). The session was repeated three months later for the nine new first-on-call ENT doctors, with adaptations based on initial feedback.

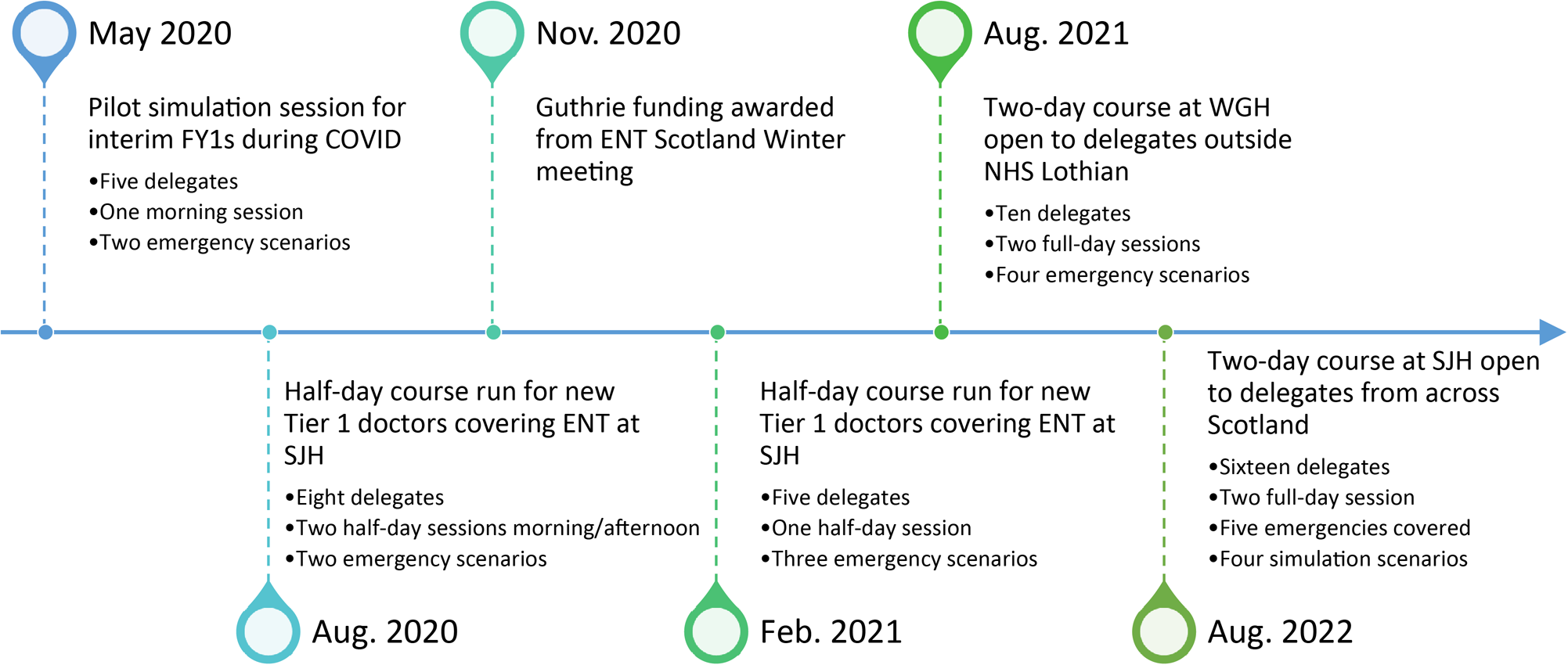

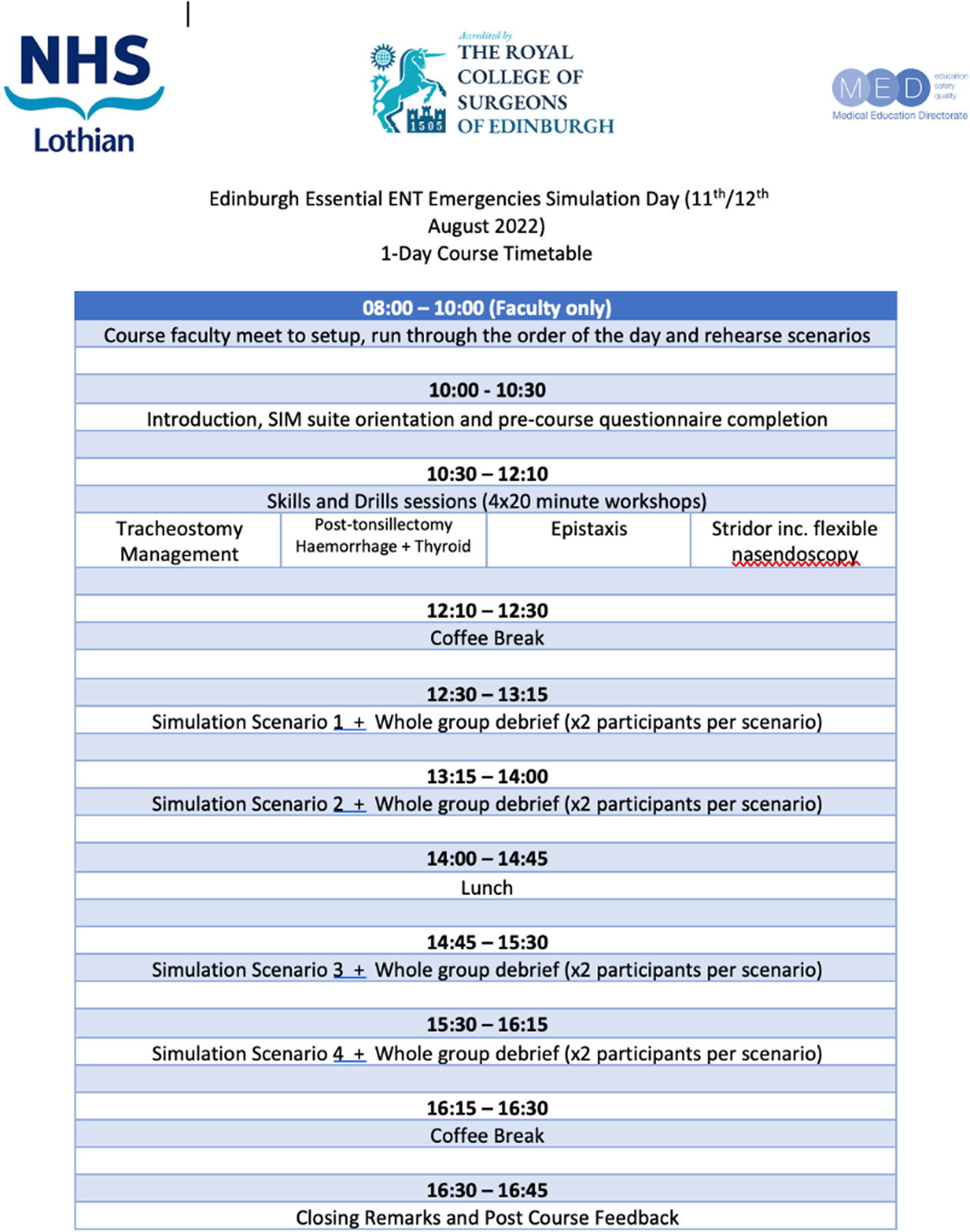

As the course developed, a combination of participant and faculty feedback was used, along with input from the NHS Lothian Medical Education Directorate simulation team and the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh, to help optimise the learning experience for participants. More time was allocated to the course, transitioning it to a full-day timetable, and it is now run for doctors across Scotland, in a range of specialties. The 2021 course received 10 participants and in 2022 this number increased to 16 over 2 consecutive days (Figure 2). Scenarios were included based on recommendations from previous participants, including post-tonsillectomy bleed, acute stridor and post-thyroidectomy haematoma. Prior to scenarios being introduced, the faculty designed ‘scenario storyboards’ in conjunction with the simulation faculty to ensure the feasibility of running them (Supplementary Information 1, available on the Journal of Laryngology and Otology website). The most up-to-date version of the course timetable is shown in Figure 3. Scenarios were run and debriefed by trained faculty from both ENT and simulation backgrounds.

Figure 2. Timeline showing the development of the ENT emergencies simulation programme since its inception in May 2022. FY1s = foundation year 1 participants; COVID = coronavirus disease 2019; WGH = Western General Hospital; SJH = St John's Hospital

Figure 3. The structure of the simulation day.

Clear and measurable intended learning outcomes were established in conjunction with the NHS Lothian Medical Education Directorate and these were applied to each of the emergency scenarios. Comparing participant feedback to our predetermined intended learning outcomes offered a valuable method of assessing the impact of the course. As the course has developed and transitioned from a local programme to a Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh endorsed course, the process of feedback collection has been enhanced. A five-point Likert scale is still used for many of the responses, but the questions are now tailored towards the intended learning outcomes for the course. An example of the feedback form is given in the Supplementary Information 2, available on the Journal of Laryngology and Otology website. Data were collected via a questionnaire to participants at the end of their ENT placement to assess the impact of how this simulation training has led to sustained performance in clinical practice (Supplementary Information 3, available on the Journal of Laryngology and Otology website). This demonstrates a higher level of impact on service if an education programme can prove a positive and sustained impact.Reference Roussin and Weinstock2 From this we were able to assess how well the training had prepared participants for real-time emergencies, what could have been improved and whether any further scenarios would have been helpful in advance of managing an ENT on-call shift.

Results

Ten participants attended the course in August 2021, post-course feedback was received from eight participants and post-ENT placement feedback was received from five participants. Attendance increased to 16 participants in August 2022, when feedback was received from 15 participants post-course and 6 participants post-ENT placement.

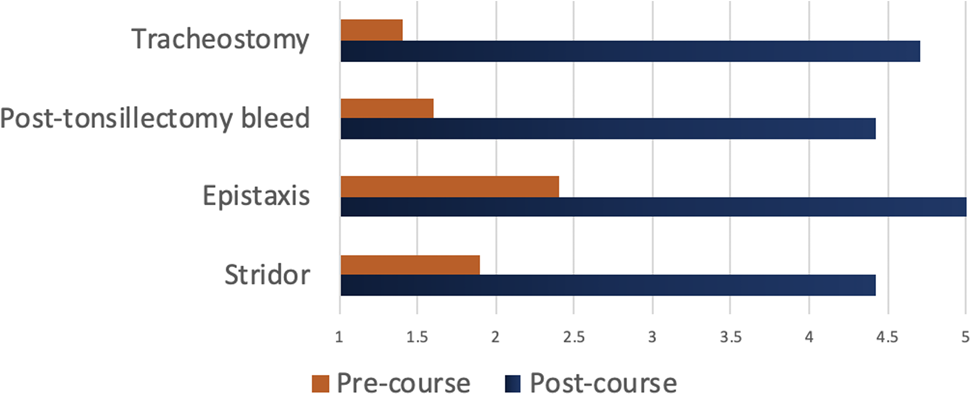

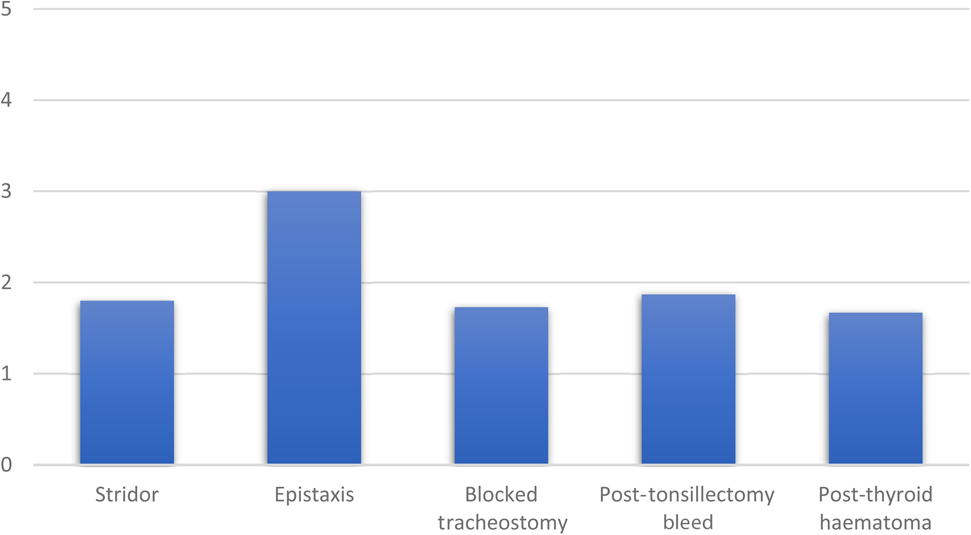

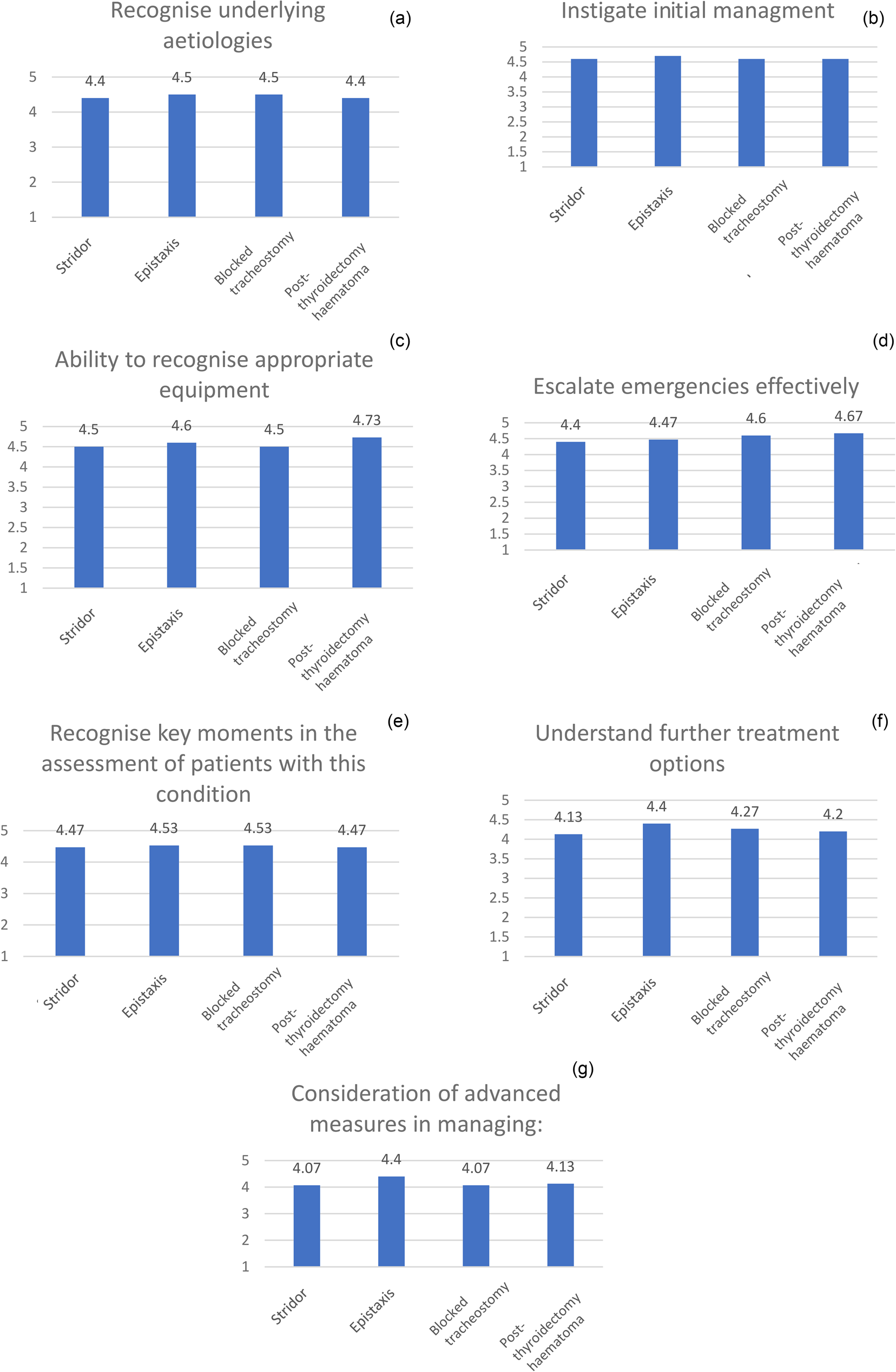

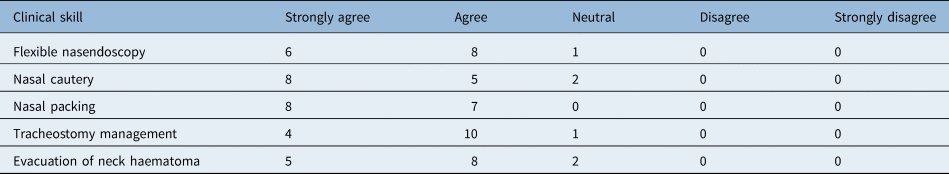

From the 2021 course, Likert scores for confidence in managing respective emergencies before the next shift demonstrated mean improvements in tracheostomy emergency from 1.4 to 4.6, in post-tonsillectomy bleed from 1.6 to 4.4, in epistaxis from 2.4 to 4.9 and in stridor from 1.8 to 4.4 (Figure 4). In 2022, one extra scenario, post-thyroidectomy haematoma, was added. The pre-course preparedness levels are outlined in Figure 5. Post-course analysis was divided into how confident participants felt at recognising underlying aetiologies, instigating initial management, recognising equipment, escalating emergencies effectively, recognising key moments in the assessment of the condition and understanding further treatment options. The mean results outlining participants’ perception of improvement over the course are outlined in Figure 6. The results demonstrate significant improvement in the participants’ confidence to manage all scenarios, with the greatest magnitude of improvement observed in those scenarios they were less familiar with at the outset, such as blocked tracheostomy and post-tonsillectomy bleed. Table 1 demonstrates how most participants felt more confident in performing key practical ENT skills by the end of the course.

Figure 4. Changes in participant confidence pre- and post-course (August 2021). Participants scored how confident they felt to manage ENT emergencies pre- and post-course on a five-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree. n = 10 responses.

Figure 5. Pre-course questionnaire results from August 2022. Delegates scored how confident they felt about managing ENT emergencies on a five-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree. Mean scores are shown. n = 15 responses.

Figure 6. Post-course Likert scale scores for how confident participants felt assessing and managing four different ENT emergencies: stridor, epistaxis, blocked tracheostomy and post-thyroidectomy haematoma. 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree. Scores shown are mean value. n = 15 responses.

Table 1. Confidence of participants in managing certain key clinical skills by the end of the course

Values are in number of delegates.

Feedback on the strengths of the course highlighted the high faculty-to-participant ratio, the opportunity for lots of hands-on, practical experience, well-designed high-fidelity scenarios, including the use of trained staff nurses, and ample opportunity to discuss cases and scenarios with experienced and knowledgeable faculty.

Areas highlighted for improvement that we intend to address for future courses include some of the debriefing sessions taking too long and repeating many of the same discussion points, as well as technical glitches. The former we aim to address by putting all our faculty through a simulation faculty development training course and encouraging attendance at our local meta debrief club to enhance and maintain this skill set.

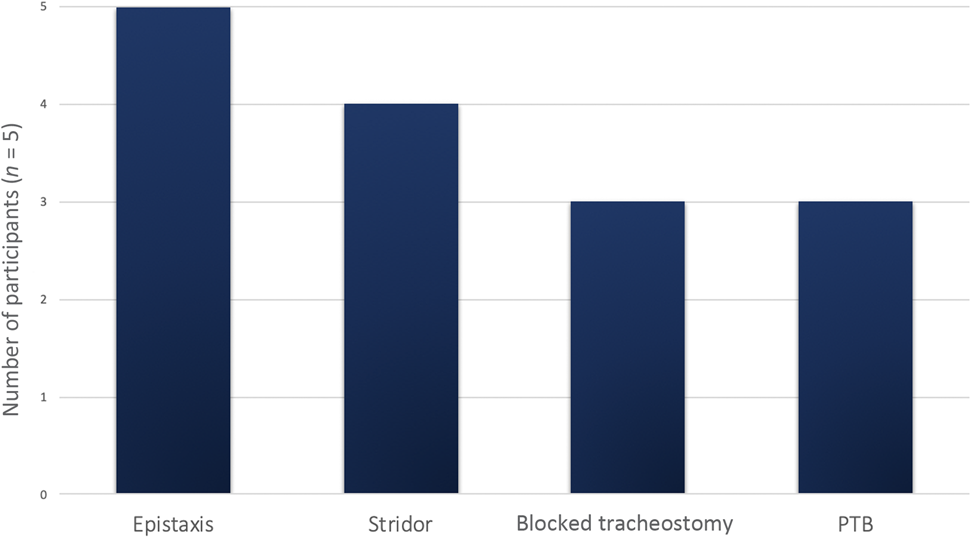

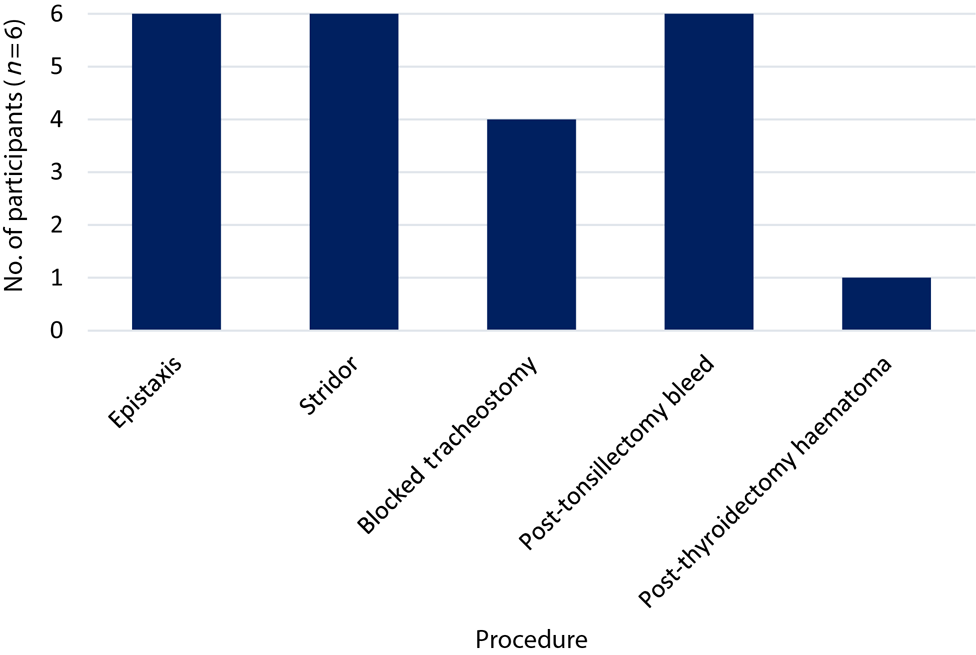

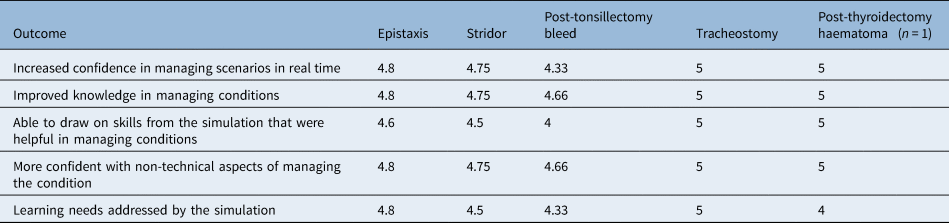

The response rate from post-placement participants was limited, with five responses in 2021 and six responses in 2022. From the 2022 results, it was reassuring to see that the participants had a chance to manage most of the emergencies covered in the scenarios (Figures 7 and 8). Stridor, epistaxis and tracheostomy emergencies scored the highest in terms of how well participants felt our course helped them manage in real time, with post-tonsillectomy bleed scoring lower. The mean Likert scores are summarised in Table 2. Feedback suggested that the course should cover other complications of tracheostomy and expand further on managing post-tonsillectomy bleeds as these were frequently encountered.

Figure 7. Opportunities for participants to manage scenarios in clinical practice during their ENT job, 2021 cohort. PTB = post-tonsillectomy bleed

Figure 8. Opportunities for delegates to manage scenarios in clinical practice during their ENT job, 2022 cohort.

Table 2. Post-ENT placement summary of mean scores outlining how well the simulation course prepared participants for clinical practice across five scenarios

*n = 6 responses. Five-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree.

Discussion

Strengths of the course

The course is designed around the educational principle of constructivism,Reference Steffe and Gale3–Reference Dennick and Matheson5 whereby the participants are introduced to theory and skills at the beginning of the day, with the opportunity to ask questions and practice with the equipment and models. They are then re-introduced to these themes later in the day through the medium of high-fidelity scenarios, enabling consolidation of prior learning in a clinical context. The trained, faculty-led scenario debrief using the Scottish centre debrief modelReference Oliver, Shippey, Edgar, Maran and May6 is critical in helping participants recognise learning outcomes from the scenarios through open questioning, facilitated self-reflection and group discussion. This creates a shared mental model to allow everyone to benefit from the learning, not just those who participated in the scenario.Reference Dieckmann, Molin Friis, Lippert and Ostergaard7–Reference Abulebda, Auerbach and Limaiem9 Scenario simulation has the added benefits of building on knowledge and skills learned earlier in the day, and allowing integration of practising non-technical skills, such as communication and leadership.

Several challenges arose during the setup of this course. Notably, there was an appreciation that a sound knowledge of ENT does not equate to an ability to design, run and debrief an effective simulation training course. Time spent training and practising this skill is essential, and assistance in this can be accessed through the local health board or university simulation lead. Decision-making around suitable participants for the course has been a point of contention. There was interest from nurse practitioners and doctors from accident and emergency departments so a decision was made to allow their attendance, but the intended learning outcomes were retained as those designed for junior doctors covering ENT on-calls, and priority of attendance was also offered to these doctors.

Conclusion

Preparing healthcare professionals adequately for clinical practice is essential to enhancing patient safety and this course offers a safe, non-judgemental platform for junior doctors to learn about and put into practice the knowledge and skills required to manage some of the core emergencies encountered in ENT.Reference Aggarwal, Mytton, Derbrew, Hananel, Heydenburg and Issenberg10

The success of this course can be attributed to a multitude of factors, including a high level of immediate relevance to the learners, appropriately trained and enthusiastic faculty, the development of high-fidelity scenarios and continued innovation through regular feedback and input from our local Medical Education Directorate simulation team.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank NHS Lothian Medical Education Directorate and the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh for their assistance with this study.

Competing interests

None declared

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215123001597.