13.1 Introduction

Former UK prime minister Tony Blair once said: “The problem isn’t vision. Often we know what to do. The real problem is getting things done.”Footnote 1 In 2013, the World Bank Group embraced this challenge as a part of a new “science of delivery” initiative championed by its president,Footnote 2 building on an ambition that Sir Michael Barber articulated in the service of the Blair government, manifest most conspicuously in his deployment of dedicated delivery units (see Reference BarberBarber, 2015). At issue was whether organizations could develop and formalize reliable guidance about how best to translate good ideas into real impact.

As part of this effort to improve implementation, the qualitative case study has a special place. Randomized controlled trials and other tools used to assess program design or evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions provide little leverage or practical insight when the breakdown between ideas and impact lies in the hows – the specific steps taken to deliver a service or change an institution. A case study can help improve the translation of policy into results by tracing these pathways, illuminating the effects of context, process, politics, and capacities on intermediate achievements and broader outcomes.

But practitioners can also use case studies to improve performance in a variety of other ways. While previous chapters have laid out a social scientific rationale for the use of qualitative case studies, proposed standards for assessing rigor, and offered examples, this chapter focuses on employing case studies for adaptation and learning, especially in governments or organizations that seek to promote economic growth and development. It proposes that case studies useful for this purpose have seven specific qualities, though they may differ widely in other respects. Additionally, it offers a brief user’s guide for policy planners, managers, and instructors.

Our observations build on insights from two programs: the World Bank’s Development Research Group and its leading operational unit deploying case studies, the Global Delivery Initiative (GDI), and Princeton University’s Innovations for Successful Societies (ISS) program, which develops policy-focused case studies of development.Footnote 3 Both programs worked for many years with people leading change in different contexts. From 2008 through 2021, the Princeton program helped a rising generation of leaders address the institution-building challenges facing governments in fragile states and neighborhoods, low-income countries, and crisis situations. Case studies were, and remain, the program’s medium for enabling public servants to share experience with each other in an accessible manner. Similarly, the World Bank-based GDI, which launched in 2014, began as a collaboration among various development partners to help practitioners build a more systematic understanding of program implementation, promote policy dialogue, and improve operational effectiveness. The Global Delivery Library, one of the GDI resources, became an open repository of cases that tapped the tacit knowledge of field-level practitioners about how to navigate delivery challenges, enabling future operations to draw upon wisdom from past interventions.

13.2 From the Science of Delivery to Adaptive Management

Blair’s observation – it’s not the vision but the how that’s the problem – had its roots in a prime minister’s struggle to improve service delivery across different sectors, especially education, health, and policing. In the United Kingdom, as in every country, implementation is often the great bugaboo on which great ideas stumble. But offering reliable generalizations to help guide the work of front-line providers, managers, and ministers poses many challenges. The social world cannot be reduced to a set of laws or principles as easily as the natural world.

Efforts to frame a science of delivery exposed two different policy worlds: one in which it was possible to base generalizations on credible evidence, and another in which tracing the influence of actions on impact was more difficult, though still valuable. In medicine and education, for example, there were some strong points of agreement about measures that could have a big impact on broad outcomes, as Reference WagstaffWagstaff (2013) has correctly noted. Take the example of vaccination against childhood diseases. There is mounting evidence about how best to scale vaccination campaigns. Though not completely reducible to a formula – at least not to one that works the same way to the same extent in every setting – it is possible to think systematically about how to achieve results, including estimates of the participation rates needed to create herd immunity and innovations to help maintain the cold-chain when lack of electricity threatens vaccine viability. Reference WagstaffWagstaff (2013) points out that it is unsurprising, then, that champions of a science of delivery – the testable, relatively stable understanding of cause and effect within the implementation process – often started their careers in a field such as public health and that journals such as Implementation Science were specific to this policy area.

This science came together as the confluence of many strands of research and multiple methods of investigation. It is notable that the contributions in the pages of the Centers for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report have included not only analysis of epidemiological data, but also case studies based on field interviews.Footnote 4 The qualitative case studies help identify the nature of the many gaps between the release of a vaccine to a health worker and actual protection of an individual against the disease, and often to point to remedies. By tracing the breakdowns in the process, they spur adaptation that could help improve the match between the numbers of people a campaign aimed to protect and actual levels of vaccine administration. Through multiple cases, as well as larger tracking studies, practitioners are able to come closer to answering the key “How?” questions that Reference BehnBehn (2017: 94) rightly highlights as essential elements of a science of delivery: “How does this strategy produce results? What exactly are the causal connections between the strategies employed and the resulting outputs or outcomes?”Footnote 5

Case studies have also aided understanding by enabling us to probe why outliers – exceptional successes or failures – differed from the patterns normally observed, thereby illuminating possible ways to improve performance across the board. This was the approach adopted by Reference Brixi, Lust and WoolcockBrixi, Lust, and Woolcock (2015) to learn from local service success stories in parts of the Middle East and North Africa. Household survey data from several countries in the region indicated that student performance was often poor, despite the fact that school access and facilities had improved. If all schools in a country operated under the same set of regulations, these authors asked, why do some areas perform so much better than others, controlling for demographics? Did the differences stem from a condition outside the control of managers, or was it something that principals and teachers in one area just decided to do differently – a practice that, at least in principle, others could replicate? The household surveys did not contain the type of information that allowed them to answer these questions, so the team went to the successful schools and studied them. One hypothesis was that degree of parental engagement affected both teacher behavior and student performance. The questions the team posed therefore included several about interaction between school officials and the community. The case studies found that the successful schools were those where principals and teachers met with residents and there was more communication with families. The challenge was then to figure out how to generalize a practice that was at least partially sensitive to the orientations and aptitudes of school leaders. In this instance, qualitative case studies supported development of alternative explanations and illuminated a potential solution to the problem of low-performing schools.

Not all policy spheres look like either of these examples, however. In some, policy arenas, implementation involves multiple changes at once, which means there are several possible causal explanations for outcomes. In Reference BehnBehn’s (2017: 96) words: “Thus, the manager’s ability to assign causal credit is difficult. And if the management team is just starting out – if this is the team’s first effort to improve performance – which of the team’s multiple actions deserves how much of the credit?” The answer to this question cannot be called “science,” he says. “It could, however, be an intelligent guess.”

An intelligent guess is a step in the right direction, a hypothesis rooted in facts, though it isn’t the same as an evidence-based handbook, the kind of product Reference BehnBehn (2017) suggests a science would produce. Where it is hard to winnow out which conditions, circumstances, or actions carry the most weight in delivering a development outcome, and where we are therefore likely to have a high ratio of intelligent guesses in decision-making, implementation may adhere to a different model. Continual review, learning, and mid-course correction become essential. Though long practiced, this approach has more recently gone under names such as “adaptive management” or AdaptDev, which now has its own Google Group,Footnote 6 “Doing Development Differently” (DDDFootnote 7), and “Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation” (PDIAFootnote 8). The common idea across these new platforms is that where a traditional after-action review, for example, is conducted at the end of an initiative, the push instead should be for feedback and learning to occur throughout an effort to implement a policy or institutional change. Reference Booth, Balfe, Gallagher, Kilcullen, O’Boyle and TiernanBooth et al. (2018: 8) point to a process in which implementers, in response to complex challenges, “deliberately set themselves up to learn by trial and error, testing initial approaches and adjusting rapidly as evidence on possible avenues of change is acquired.” Matt Reference AndrewsAndrews (2018: 1), one of the key contributors to this approach, has written on the basis of his long experience: “We always ask of PDIA in practice: What did we do? What results emerged? What did we learn? What did we struggle with? What was next?”

Although both policy learning and learning-by-doing have a long history, the ambition of the Doing Development Differently and AdaptDev communities that have emerged in this space is to expand the practice of experimenting, learning, and adjusting in domains where broad evidence-based generalizations about implementation are out of reach. In these areas, the people responsible for translating ideas into practice will almost certainly encounter challenges and unexpected obstacles (Reference SchonSchon 1983; Reference Pritchett, Samji and HammerPritchett, Samji, and Hammer 2013). If they do not step back, reflect, learn, and adapt, they risk persisting with interventions or strategies that are not well suited to the situation that they face. Therefore, these teams must be ready and willing to adapt mid-course, to experiment and scale up what works, and to iterate and integrate feedback into implementation. Together with careful planning and the elaboration of a clearly articulated theory of change, the incorporation of “rapid feedback loops” into an endeavor is crucial, as is using these processes for “learning in response to ongoing challenges” (Reference Pritchett, Samji and HammerPritchett, Samji, and Hammer 2013: 1).

In this corner of the policy world, where causal relationships are less straightforward than they are in public health (and elsewhere), case studies help practitioners pool observations, recognize what has worked, identify where things aren’t turning out as anticipated, flag surprises, and open up space for adaptation. They help make the tacit knowledge practitioners have accumulated as explicit possible. Although they may draw on focus groups, surveys, and quantitative evidence, they employ interviews to help trace the steps taken, departures from the roadmap, and intermediate results in order to help us better address both anticipated and unexpected circumstances and increase the probability of generating intended impacts.

In early experiments, embedding case development and data collection directly into projects not only strengthened the quality of evidence produced but also enabled managers to make mid-course corrections and secure stronger buy-in from other stakeholders. Innovative elements have sometimes included smartphone surveys to check whether a service reached intended beneficiaries or assess satisfaction, geotagged information displayed on maps to help spot service coverage issues, satellite photography to track crop conditions, and other information generated with relatively low-cost and flexible tools that have a broad variety of applications (e.g., see Reference Danquah, Hasham and MacFarlaneDanquah et al. 2019 on Sierra Leone). Workshops to document and review implementation steps taken to date help staff members spot omissions and bottlenecks and discuss creative ways to surmount unanticipated obstacles.

The World Bank’s Global Scaling Up Rural Sanitation program aptly illustrates this kind of effort. With the goal of making a dent in the 2.5 billion people worldwide without access to improved sanitation, the project launched pilots in three countries, which served as learning laboratories for developing a theory of change. After this pilot phase concluded, the project then made the necessary adjustments and scaled up to a further 10 countries; to date, it has provided some 22 million people in 13 countries with improved sanitation.

The use of pilots in the initial “learning laboratory” countries provided crucial knowledge about what worked and what did not. This information was then disseminated through a global network, allowing team members to reflect on and analyze the results of their actions. Team leaders were able to learn from these initial lessons in real time, allowing for quick adaptation. An iterative and adaptive approach was also hardwired into the program, giving task team leaders both the freedom and the mandate to apply lessons learned in their countries or areas of responsibility, while also adapting and correcting course as they scaled up and collecting their own evidence locally to target effective behavior changes and interventions.

A second example from the GDI illustrates a slightly different approach, this time in the context of improving access of Nigerians to sustainable, clean, potable water. A case study indicated that governance reforms were difficult to implement, trust in the system was low, and monitoring was weak – with the result that progress had stalled. It was crucial to establish trust, build networks, and enhance relationships with a wide variety of stakeholders. To design a new phase of the project, the World Bank decided to share the case study and solicit ideas from each major stakeholder. It organized a series of meetings to invite observations and proposals. The first convened its Nigeria task team leaders. The subsequent meetings took place in Abuja and involved participation from representatives of more than sixty agencies, including the head of the Federal Program Implementation Unit, the high representative of the Federal Ministry of Finance, State Ministers of Water, State heads of the program implementation units, and the World Bank Country Director. Participants had a chance to discuss the case itself and introduce other information, then they charted out concrete recommendations.

13.3 Seven Qualities That Make a Case Useful for Practitioners

For purposes of learning and mid-course adjustment, not all case study formats are created equal. Moreover, the information and format needed are not always the same that academic colleagues seek. The GDI and Princeton’s ISS program both ambitiously tried to tailor what they do to serve three distinct audiences: practitioners who want to improve implementation success, policy researchers or scholars who want to ground a (social) science of delivery, and aspiring leaders completing courses of study in universities and staff colleges or executive education programs. The jury is still out on whether it is possible to serve three masters equally well. Nonetheless, the experience to date has generated some wisdom – not yet formally tested! – about what helps a case to meet the needs of practitioners. This wisdom can be spelled out in seven principles:

1. A good case draws on a clear, shared lexicon.

A good part of what makes some cases more useful than others in development policy is the conceptual structure that underlies them, the lexicon. A good case is far more than a heap of facts the reader must somehow fit together. A good case focuses on subject matter that is central to a decision or series of decisions and helps reveal the development challenge and choice architecture, as well as the conditions or circumstances that affected the options available and the degree of success. The utility of a case depends on the ability to attach general names to the core challenges and in so doing facilitate comparison and consideration of alternatives.

A lexicon precedes a theory. It is a conceptual map, the key or index a practitioner, instructor, or researcher needs to identify other instances in which the same issue arose. For example, the difficulty people have in coming together to provide a public good, like a litter-free street, is a collective action problem. To be useful, qualitative cases that address this issue either have to use the term or employ the definition, minus the jargon, so that we can draw them into the pool of shared experience.

To employ an analogy, many of us have probably had the experience of moderating a discussion in which people with diverse experiences share their recent work. The moderator’s job is to find the common ground, the shared problem on which the participants have something to say and could learn from each other. That job is much easier when the presenters share a lexicon and use that reference to define their focus and structure their remarks. Otherwise the moderator has to try to discern points of congruence based on fragmentary information – or ask the author, “this is a case of what?”

The ease with which we can learn from qualitative cases hinges partly on the degree to which the general names unlock the experience of others. It goes without saying that to be useful to development practitioners, this lexicon has to respond to how those practitioners think about their work and to what they seek to know. For example, to assist with implementation, both ISS and the GDI developed frameworks that featured a variety of delivery challenges (such as geographic fragmentation) and common impediments to success in achieving a broader development outcome (such as better health). But the aim was also to link users to broader theories and toolkits helpful for thinking outside the box and developing new approaches.

Located in an academic institution, ISS defined its lexicon by matching the problems governmental leaders said they encountered in trying to build more effective and accountable government with existing conceptual vocabularies in the social sciences. For example, some cases focus on coordination problems, and the program treats these in several different domains or policy spheres, including cabinet offices (centers of government), public financial management, disaster response, and business process improvement. In addition to coordination, collective action, and principal–agent/agency issues, the program focuses on problems that are especially difficult because they can lock a country into subpar performance: institutional traps, capacity traps, norm coordination traps, or thresholds, for example. (This approach led one reviewer to term the program’s work “trapology.”)

The GDI tried to secure a tighter fit between its lexicon and the mental maps of people in its diverse user base.Footnote 9 It reviewed more than 160 development publications to identify the delivery challenges most often encountered and conducted a text analysis on more than 4,000 Implementation Completion Reports from projects supervised by the World Bank and other development organizations. Focus groups reviewed the draft lists. The final result was a taxonomy with two levels. At the higher level, the program chose fifteen broad types of implementation problems across three dimensions: stakeholders, context, and project.Footnote 10 Below that were fifty-two additional keywords that presented a more granular view of specific delivery challenges. In the end, the effort yielded a taxonomy that included a mix of challenges, in several domains of application, mirroring the way many potential users searched for information and advice.

2. A good case has a structure that communicates what a practitioner needs to know and facilitates cross-case comparison.

Whatever the realm of use, a good case is a story with a particular spin, in the sense that it helps the user focus in on the information needed to draw conclusions. Structure is important for this reason, and the right structure depends on the intended purpose. If the focus is on implementation, then the case should track the stages of the implementation process, for example: problem recognition, likely delivery challenges, framing and strategy, steps taken to implement, adaptation processes, results obtained, and thoughts about what one might do differently. This ideal-type may not perfectly mimic the actual policy process in a given setting, but a decision-maker can easily follow the case narrative and relate to the subject matter if arrayed in this way, as well as compare and contrast with other cases.

The ISS program and the GDI both adopted templates to facilitate comprehension and comparison. With a few exceptions, the main actors – the “voice” of the story – are civil servants, civic leaders, task managers of projects, and occasionally managers based in international organizations. The text walks the reader through the context and the anticipated challenges (a set of hypotheses about potential sources of difficulty), and shows the options considered and the program design or strategy adopted to address these. Each case documents the new practices or policies a reform team created and the steps they took to win support, secure authorization, build awareness, reshape organizational cultures, and do the many other things often required to put a new system in place. In this respect, the approach resembles the classic Harvard Business School management case that puts the reader into the driver’s seat alongside the person who has to solve a problem. The cases also document unanticipated obstacles and happy surprises, then conclude with results and participants’ reflections on what they would do differently next time or in a different context.

3. A good case entertains multiple hypotheses.

Many different possible causes may account for an outcome. The case should make these visible to the reader and indicate where one or another appears to influence implementation, independently shape outcomes, or affect the scope conditions attached to solutions decision-makers employed. If the influence is negative, a work team can then think about how to solve the problem or mitigate the effects. If the influence is positive, the team might ask itself whether there are ways to amplify the impact. In this way, making hypotheses explicit facilitates adaptive management as well as instruction. This step also enhances the usefulness of a case for social scientists and policy-makers who aim to conduct cross-case comparison or internal process tracing to try to adjudicate among theories.

One sometimes hears that a good case must leverage a single underlying theory. But is that necessarily true? This approach is often too restrictive in practice, though it has its place. It would mean that, as in some kinds of social science research, the purpose of a case is to help us decide whether to accept or dismiss a particular account of results or impact. In areas where conditions may make a science of delivery achievable, as in aspects of public health, education, or economic policy, there is a rationale for constructing cases in this way. But for the purposes of adaptive management, in policy spheres where multiple causes are in play, it is preferable to entertain a range of theories and the hypotheses that flow from them.

There can be tension between the ultimate use of the case and making hypotheses explicit up front. The ISS program wrestled with this problem, sometimes with mixed success. Each series of its cases begins with a research design that highlights the many influences it wants to trace. Most of these become part of the challenges the decision-makers in the case confront, laid out in the second section. However, to ensure cases are engaging to read, ISS does not tag its hypotheses as such. Moreover, not all appear in the same section in every instance. Separate cross-cutting analysis carries the weight of this need. The decision to proceed in this way has consequences, however, and one is that many see the cases as purely inductive, scoping exercises. To conform more fully to a social science model, the program would have to produce a second, stylized version of each case that directly engaged hypotheses and shed other detail.

On the basis of its early experience, the GDI discerned five core categories of causal influence that development practitioners valued highly. Though not each was equally important in every instance, these dimensions provided an instructive set of entry points for assessing the dynamics of implementation and gradual accumulation of granular knowledge about these effects of contextual characteristics, political factors, and the actions of implementation teams on outcomes and impact.

The five dimensions (outlined below) were interconnected, complementing and enabling one another. Cases examined how particular challenges encountered along the way were managed with respect to:

a. Citizen demands and citizen outcomes: defining the goal as measurable gains in citizens’ well-being; identifying the nature of the problem based on a thorough understanding of citizens’ demands and local context; staying attentive to all factors that influence citizen outcomes, including, but not limited to, grassroots representation and bottom-up political pressure.

b. Collaboration: facilitating multistakeholder coalitions and multisectoral perspectives to identify and prioritize problems and coordinate (possible) solutions; convening varied development partners and building on their competitive advantages; tracing the impact of coordination structures on development outcomes.

c. Evidence to achieve results: using the best available evidence to identify problems and solutions; developing local evidence to refine solutions; collecting evidence of results throughout the project cycle; contributing to the global body of knowledge with the evidence collected for scaling up; whether outcomes were driven by evidence.

d. Leadership for change: understanding local political economies and drivers of change; identifying the incentives that motivate behaviors and integrating these into designing delivery solutions; evaluating whether incentive systems or political will accounted for outcomes.

e. Adaptive implementation: developing an adaptive implementation strategy that allows for iterative experimentation, feedback loops, and course correction; building a committed team with the right skills, experience, and institutional memory; maintaining the capacity to reflect on actions and their results; assessing whether institutional capacity for learning helped drive results.

GDI cases also included hypotheses drawn either from practitioner experience or research.

4. A good case contains essential operational detail. To serve development practitioners well, a case must speak to the issues that managers face with sufficient granularity that a counterpart in another country can follow the steps laid out. This quality often runs counter to what we seek in academe, where the aim is to test highly parsimonious theories that have broad applicability or scope, and where both the content and analysis of cases focuses on just a few key variables. The difficulty is to discern the difference between extraneous information and pertinent operational elements, which may include legal authority to act, the impact of political structures on jurisdiction, organizational routines, budget calendars, costs, information architecture, algorithms, and other elements, depending on the subject matter. From the perspective of someone trying to lead institutional change or implement a complex program, the devil is often in these details. An expert should see what she considers essential in a case and a novice should find the language easy enough to follow that the technical detail is clear.

When the person or team researching and writing the case (or facilitating case development) is unfamiliar with a subject area and the specific issues managers confront, reaching the right level of granularity may pose a problem. In some technical areas, both the ISS program and the GDI engaged experts to partner with them or to review initial briefings before case development began. Employing questions broad enough to allow practitioners to discuss their work in their own terms also helped the cases reach essential detail. It was always useful to ask, at the end of a conversation, “What would you like to know about how your counterparts in other countries have tried to reach the outcome you wanted to generate?”

5. A good case pays attention to political will but need not make political will its focus. Whether in the limited sense of having approval (authorization) from a department head or in the larger sense of having the backing of the head of state, implementation cases usually cut into a problem after there is at least a modicum of political will to proceed with a program and after an opportunity or ripe moment has already materialized. Sometimes sustaining political will is indeed one of the obstacles, but usually addressing this issue is antecedent to the steps taken to deliver a result. If there is no will, there is no policy intervention, and for those of us interested in improving implementation know-how, the “no will” cases are generally less interesting than others (though sometimes good ideas and initiatives bubble up without leadership).

A good practitioner case identifies the source of political will, as well as changes in intensity or motivation that may flow from political transitions, rotation in office, changes in popular opinion, unexpected events, etc. The case should identify how political backing was sustained or grew, or whether it was simply irrelevant and why. Were there self-reinforcing incentives built into the program design? Did program popularity make it difficult to change once the program started to deliver results? Were citizens groups able to lobby? Did leaders become part of a professional community favorable to a program’s continued operation? It may be tempting in some instances to attribute a project’s initiation or durability to outside pressure from a development partner, but rarely is that true. A good case explains why officials acceded, if in fact they did so.

6. A good case discusses scope conditions. One of the criticisms of randomized controlled trials is that they have limited external validity (Reference Pritchett and SandefurPritchett and Sandefur 2015). We often just do not have the information to know whether the same result would occur in other places, for other people, or during different periods in history (Reference WoolcockWoolcock 2013). Learning from qualitative case studies can be prone to this same problem, but an implementation case usually provides some grist for thinking more systematically about whether the experience highlighted holds lessons for others. That grist comes in the form of a clear specification of context and analysis of how context shaped the steps taken and the results achieved. Such an analysis provides some basis for understanding how a change in implementation circumstances (context, scale, population) might alter the result.

Beyond encapsulating these broad principles, both ISS and the GDI made it a practice to offer the people who did the hard work of putting a program into practice a chance to think about how their experience generalizes, thereby capturing some of the tacit knowledge in the heads of these experts. For analytical purposes it is important to establish the parameters within which the findings of a given case apply, and experienced practitioners are often keenly aware of how slight differences in legal authorization, public opinion, or institutional capacity could make it hard for others to emulate their successes.

7. A good case is fun to read. Our two programs differ with respect to this seventh quality: the “engagement factor.” People are busy. Senior officials, especially political leaders, are exceptionally so, and gaining their attention can be hard. If the purpose of a case is adaptive learning or diffusing experience, then a case ought to draw the reader in and get to the point fast. For this reason, the ISS program opted to follow a Harvard Business School management case model that puts a decision-maker in the driver’s seat, uses names and quotes (cleared with the people interviewed), and keeps jargon to a minimum. Its cases put the reader right at the coal-face.

This approach had its pros and cons, however. In the program’s view, while it boosted engagement with many practitioners and with students, it sometimes hurt credibility with a social science research audience, for whom this approach seemed to imply a “great man” theory of history. In the program’s view these concerns were often misplaced. The style was similar to highly commended scholarly work on political development. The social science translation problem more often lay in the release of individual cases separately from cross-cutting analysis – and outside the realm of peer-reviewed journals.

For its part, the GDI, initially hosted within a multilateral organization, chose a different approach. Its cases usually treated an agency within a government or an institution as the lead actor, though it may mention the names of those involved. By virtue of being a consortium of more than forty partner organizations, of necessity the case writing style adopted had to balance ensuring adequate cross-program coherence with fitting the particular preferences and imperatives of its affiliate members. This approach also came at a cost, sometimes obscuring the internal negotiation dynamics within the agency in favor of a cleaner or more administratively procedural account. That said, adopting such an approach also allowed communities of practice to stand back and evaluate a situation more dispassionately.

13.4 Putting Cases to Work: Moderating a Case Discussion

A case is not usually a stand-alone document, though it can be so. If an important purpose of case studies is to promote learning and adaptation, then much rides on their capacity to stimulate group reflection, deliberation, and innovation. This in turn raises another question: How does one effectively moderate a case discussion?

Coming forward to the present, in our experience, the tone, sequence, and focus vary depending on whether the aim is to teach – to introduce key concepts and ways of thinking about a problem – or to help people who have participated in implementation reflect on their work. For the first purpose, the moderator may play a strong role in directing the discussion so that a group reaches key points, pausing to elaborate these. By contrast, for adaptive learning, where the point of a discussion is to help the people who carried out the work reflect and solve problems, the moderator may stand back a bit more to give participants a bigger opportunity to shape the agenda and to get into specific operational details in more depth than one might in a classroom setting. In both situations, however, there are some shared objectives, most importantly stimulating creative thinking about ways to: overcome obstacles that continue to impede success; mitigate the downsides of a generally successful response; reach difficult (isolated, marginalized) communities; take the intervention to scale; or adapt an approach for different circumstances.

To use a case for classroom purposes, we usually begin by reminding the group of the broader issues at stake. Every case has a development challenge at its core, the public value the people at the center of the action seek to create: the desired impact on citizens’ lives. Every action also has an author, so naming names is important, or at least naming offices: “Minister Marina da Silva wanted to reduce the rate of deforestation in order to adhere to a new climate regime and preserve water quality and availability in her country”; “Sudarsono Osman wanted the land registries in Kuching to serve citizens faster, with fewer errors.” The discussion leader may want to add some additional facts to situate the issue, identify what created the space for change, and add some more detail about the lead decision-makers.

Next comes the dramatic moment: “But … something stood in the way.” The discussion leader then poses a series of questions, beginning with “What was the main problem, the main delivery challenge?” At this stage, it is important to ensure that everyone can identify the general form of at least the major implementation problem in a case – process efficiency, aligning the interests of a principal and an agent, collective action, or coordination, for example: “Mr. X is responsible for making the program work, but he’s stuck. At the start, what is his main problem? What is the general form of this problem?” Knowing the general form enables the case user to link to a general toolkit and consider whether solutions often considered in other settings might be useful in the circumstances at hand. The ability to abstract in this way enlarges problem-solving capacity. It is important to pause and sharpen familiarity with the general concept and the standard toolkit at this point.

Third, we help users connect with the context: “What do we know about the setting and the elements of context that might shape which tactics Mr. X can deploy?” Context is something that will come up throughout the discussion but especially at the end, when the focus is often on scale, scope conditions, and adaptations required to help a similar approach work in another setting. Context may include resource levels, diversity, socioeconomic conditions, government structure, legal authority, and many other conditions or circumstances, some of which may be malleable, while others remain fixed.

The real focus of the discussion comes after this point: “What options did they consider? Were there other possibilities and, if so, do we know why they weren’t considered? What motivated the choices they made?” And then: “Let’s work through the steps the team takes … ” The central objective is to develop a clear outline of the strategy and tactics employed. If the real issue the instructor wants to use as a focal point occurs later in the case, then it may be perfectly acceptable to expedite the discussion and simply throw the key elements of the initial response into a Powerpoint slide. “So here are the steps they initially took … Have I got it right?” Usually, however, the aim is to pause to consider the purpose of each step, the appropriateness of the design, what proved difficult to do, any pleasant surprises, and how sensitive the actions taken were to the aptitudes of team leaders or context.

In the classroom, the instructor’s job is to help participants identify concepts useful for analyzing problems that emerge at each step, as well as to bring external information to bear, where warranted. One of Princeton’s Ebola response cases, for example, focuses on carrying out contact tracing in a very difficult context. If the group is unfamiliar with the key elements of contact tracing, it is helpful to call a short “time out” and explain these in some detail. Even if the elements are in the case text, pausing to reinforce the ideas is often helpful for nonspecialists.

Sometimes the focus of the discussion is not on the strategy or the main steps taken, but on an unanticipated obstacle a team confronts: “There is a big unanticipated obstacle in this case … They struggle to adapt. Put yourself in their shoes. How would you deal with this situation?” If the obstacle is minor and the response is successful, it is possible to fold this discussion into the previous stage of the conversation. If the obstacle is significant and incompletely resolved, the major part of the discussion could focus on this matter. The aim is then to help participants identify possible solutions by abstracting from the specific – giving the problem a general name that links to a toolbox – or by inviting each person to tap his or her own experiences and intuitions about how to solve the problem.

At this stage the moderator’s role is to ensure everyone has a chance to contribute and to provide two or three alternative ways to structure the problem under discussion, in the event that everyone is stuck. For example, in one Smart City case, a public health unit used sophisticated math modeling to identify households at risk of lead poisoning, but the effort temporarily ground to a halt over the question of whether it could enter houses at risk and intervene, given concerns for privacy, personal autonomy/consent, and data security. Did it matter that those most at risk were too young to make informed choices on their own behalf? Would the answer to these questions be different if the issue was secondhand cigarette smoke or some other kind of risk – and if so, why? The moderator stimulated thinking by highlighting the ethical principles at issue and inducing participants to think about the implications by pointing to analogous issue areas where the same quandary was a matter of settled law or procedure.

The discussion moderator may want to summarize the results actually achieved and move on, but it is also possible to craft two important conversations around this segment of the case: one focused on causation and the other focused on metrics. Often the conversation will jump to the impact on the broad development challenge, the outcome highlighted in the beginning. In most instances many things affect this type of outcome, so it is important to identify the other things that contribute – the potential confounders – and then try to identify the specific lines of influence through which policy implementation shaped this “public value.” To establish these lines of influence, we usually have to focus on intermediate outcomes or outputs: faster delivery times, lower rates of error, more inclusive coverage, etc.: “Were these the right metrics? Can you think of better metrics? If your office didn’t have much money, is there a way to assess effectiveness inexpensively?” “What contributed most to these improvements?” “On one important dimension, there was little improvement … Why?”

Finally, if the purpose of the discussion is to assess the extent to which lessons from the case are applicable in other contexts, then it is possible to skim through some of the other stages and focus on this matter. Identifying the scope conditions, or the central factors and processes shaping the effectiveness of the solution case protagonists deploy, is central to this task. It is also possible to focus this part of the discussion on ways to improve further, to mitigate the downsides of the tactics selected, or to borrow from other fields to get around some of the limitations associated with the tactics actually used.

Some moderators subdivide the cases, asking participants first to read just the opening sections that outline the problem and the delivery challenges (possibly also the options considered and framing), so that the group has a chance to think about tactical toolkits available and how to proceed. The moderator then hands out further sections of the case, and the next phase of the conversation picks up with what the decision-makers actually did and the pros and cons of the approach, improvements, etc. A third handout might focus on an unanticipated obstacle or on results, prompting another turn in the conversation.

Over the years we have come to share the view of Harvard Business Case Publishing that providing moderators with teaching notes or discussion guides improves usage and enhances the quality of discussion. These notes provide some of the general concepts, toolkits, conceptual puzzles, options, and additional background information that moderators often need to move a conversation forward and inspire creative thinking. Generating them should become a part of the case development process, and they usually flow well from the initial research design and the cross-cutting analysis produced at the end, if there is such.

13.5 Using Case Studies as Part of Adaptive Management

Using cases for problem-solving or improvement within an organization entails a slightly different approach. In this setting, the case study becomes part of a participatory process designed to improve problem identification, foster development of solutions, and win agreement on accompanying changes in practice, including monitoring results. Since 2012, this form of adaptive management, long practiced in many major companies, has attracted a following in public sector development organizations. The United States Agency for International Development’s adaptive management principles, treated as requirements in some of its assistance packages or awards, include elements such as regular monitoring of results; practices to support mid-course review of strategy and implementation and course correction; rewarding “candid knowledge sharing” and collaborative learning; and sharing results widely.Footnote 11

The qualitative case study can play an important role in this approach. In some instances, the case writer’s role is to conduct interviews before a mid-course review begins and to assemble observations of individual team members and beneficiaries in a form the moderator can use to structure discussion of what has worked, why some steps did not succeed to the degree anticipated, and what to do next. The project manager may then use the results of the conversation to revise the program so that there is a record for comparison after the next attempt to improve delivery. Alternatively, a designated writer may skip the first step and become the recorder for the group discussion, creating a case as a record or after-action report. Qualitative cases drawn from other settings may also enter the moderated discussion at various points in order to spur reflection and creative thinking about what decision-makers should do next.

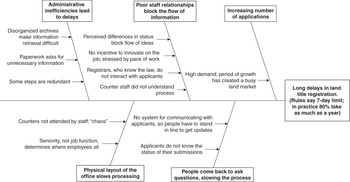

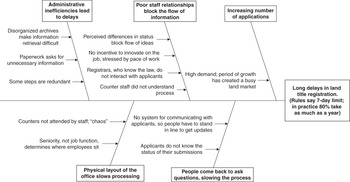

Those developing the PDIA approach have given this issue a lot of thought. In their experience, one of the challenges associated with learning and adaptation is to induce team members to think hard about the sources of success and difficulty. For this purpose, they employ some of the tools of the trade that Toyota has developed – for example, the “Five Whys” exercise that asks participants to push themselves beyond an initial statement about the proximate cause of a problem to deeper reasons: If A was the cause, why did A happen? If B caused A to happen, what caused B?Footnote 12 They go through this exercise at multiple points, creating a “fish diagram” to help provide a record of the discussion (see Figure 13.1). This discussion generates information and insight to incorporate in the next case draft, rendering the case study a collective, participatory product.

The next step is to encourage people to think outside the box in generating solutions for each problem the process identifies. The aim at this stage is to encourage people to draw on their own thinking. At this point it may be helpful to consider what others who have faced similar problems have done, drawing on cases from the libraries that the GDI and the ISS offer, or some other source. These stories take people out of their circumstances and surroundings, reduce defensiveness, and trigger new lines of thought. These conversations about other places usually quickly lead back to a more open discussion about the issues on the table. The moderator may summarize what another government or agency tried and then simply ask, “Would that work here, in your view?” “What would you do differently?” “What is the theory of change behind this idea?” “How will we know if this idea works?” Again, this part of the discussion can go into the case draft, if the case serves as the collective record.

But there is also a further step in adaptive learning. The PDIA authors ask participants to identify the space for change in connection with each problem identified in the previous step. That space includes three elements: Authority (who has the authority to act?), Acceptance (Do the people who will be affected recognize the need for change?), and Ability (Is there capacity – time, money, skill – to act?). This phase of the discussion may help set priorities – if the suggestion is to move where there is space or leverage – or it may lead to creative thinking about how to expand the space for change. This information may also become part of the case record.

Both the GDI and the Princeton ISS program have contributed to learn-and-adapt initiatives. In its first years, the GDI’s Science of Delivery team helped more than sixty different projects use cases to broaden or deepen thinking during review of the initial concept note, decide how to address operational challenges, or present results. Participants sometimes convened their project staff to discuss and record their experiences as their work moved forward, resulting in the gradual development of a case, or they assembled at the conclusion of a project to develop an after-action report that documents the steps they took.

The GDI described its method, the Delivery Lab, as an opportunity to bring together thematic experts with specific operational knowledge from GDI’s partner organizations and other invited guests who are working to overcome the obstacles and bottlenecks that can impede development efforts. Each lab began with a practitioner (the challenge holder) sharing an operational challenge that he or she currently faced in the context of an ongoing project. This brief presentation was followed by a facilitated group discussion and brainstorming session where experts shared relevant experiences. Ultimately, participants worked together to cocreate actionable solutions. The sessions allowed for peer exchange of experience-based knowledge, as practitioners explore problems and think through potential solutions.

13.6 Conclusion

Implementation-focused case studies play a vital role within the development community in the three key respects described here: (a) helping to develop better understanding of implementation dynamics (a science of delivery), (b) training, and (c) supporting adaptive management. But both the GDI and ISS program observe that practitioners have often employed qualitative cases for other purposes too.

Sometimes the aim is simply to help a manager or public servant structure a problem and think about the menu of options others have tried. A case study can provide a quick guide to key issues and enough operational knowledge to enable the decision-maker to figure out what s/he needs to know so as to pose the right questions in a more detailed person-to-person follow-up conversation. For instance, Princeton’s ISS program has documented the efforts of a number of governments to improve cabinet office coordination and support for policy decisions. These cases have helped chiefs of staff and deputy ministers learn from each other without having to take valuable time to travel abroad in search of ideas. But they have also facilitated face-to-face small group meetings that have matched those who have led impressive reforms with those who are just beginning to think about what to do.

To take another, similar example, the GDI used a case on accountability for mineral royalty funds to support Colombia’s peace process. In Colombia, royalty funds from mining and natural resources held potential for financing local projects and building legitimacy. However, early experiences in managing natural resource funds were unsuccessful in part because local governments lacked capacity to avoid misallocation, corruption, and poor planning, and the central government had no mechanism to remedy this problem. As a result, instead of building peoples’ confidence in their governments, the initial program undermined trust and the sense of government efficacy. The National Planning Department then created a new program that had flexibility to help local governments to build their capacity to implement projects, while also mobilizing community members to carry out “citizen visible audits.” The case study on this program, which helped ensure that money was not stolen or misplaced and that projects met the real needs of the citizenry, helped foster agreement among parties to the peace process. In Colombia, an actual example of how to build local accountability and legitimacy and equitably use natural resources to develop the country moved policy conversations forward.

Apart from this kind of use, the programs have also found that people who have played important roles in the changes a case documents value the record of achievement. Those who labored hard to make something happen often immediately move on to the next project or crisis. The case provides welcome recognition and helps them explain their own contributions to others. They say the acknowledgment helps fuel another round of effort. Indeed, organizations often ask the programs whether they will commit to develop a case study on a specific program so that managers can say to team members, “If we do well, we will become a model … ”

In other instances, people have written to say that they have used a case as a briefing to prepare for deployment to a new post. Operations documents and technical reports rarely contain names, but cases often do, thereby helping newcomers know to whom they can reach out for additional information while also offering historical context and an implicit heads up about sensitivities.

Finally, the case study is a vital tool for communicating to a wider audience what purpose a development initiative serves, the human story that unfolds around and within it, and the results achieved. It gives form and spirit to the numbers we often use to analyze policies. In an era when trust in governments and international organizations is low, the case study is a way to make the work practitioners do more accessible to fellow citizens and to rebuild shared understandings about the missions we pursue.