All drug use, fundamentally, has to do with speed, modification of speed … the times that become superhuman or subhuman.

After all, the world is industrial and we have to come to terms with it … Gone are the old good days of opium, heroin, gone are the young bangi¸ gone is hashish, marijuana, and geraas [weed, grass]! Now it is all about shisheh, blour and kristal and nakh. The modern people have become post-modern. And this latter, we know, it is industrial and poetical, like the God’s tear or Satan’s deceit.Footnote 1

Introduction

The election of Mahmud Ahmadinejad to the ninth presidency of the Islamic Republic asserted an anomaly within the political process of post-revolutionary, post-war Iran. After the heydays of reformist government, with its inconclusive and juxtaposing political outcomes, the 2005 elections had seen the rise of a political figure considered, up to then, as marginal, secondary, if not eclectic and obscure. Accompanied by his rhetoric, which tapped into both a bygone revolutionary era and a populist internationalist fervour, Ahmadinejad brought onto the scene of Iranian – and arguably international – politics, an energy and a mannerism, which were unfamiliar to Islamist and Western political cadres.

Considering his apparent idiosyncrasies, much of the attention of scholars and media went into discerning the man, his ideas and his human circles, with symptomatic attention to foreign policy.Footnote 2 His impact on the domestic politics of the Islamic Republic, too, has been interpreted as a consequence of his personalising style of government; his messianic passion about Shi’a revival and religious eschatology clashed with his apparent infatuation with Iran’s ancient Zoroastrian heritage;Footnote 3 and, significantly, his confrontational attitude vis-à-vis political adversaries manifested an unprecedented tone in the political script. Ahmadinejad himself contributed greatly to his caricature: his public appearances (and ‘disappearances’Footnote 4) as well as speeches, amounting to thousands in just a few years.Footnote 5 His interventions in international settings regularly prompted great upheaval and controversy, if not a tragicomic allure prompted by his many detractors. His accusations and attacks against the politico-economic elites were numerous and unusually explicit for the style of national leaders, even when compared to European and American populist leaders, such as Jair Bolsonaro, Donald J. Trump and Matteo Salvini, all of whom remain conformist on economic matters. Ultimately, his remarks about the Holocaust and Israel, albeit inconsistent and exaggerated by foreign detractors, made all the more convenient the making of Ahmadinejad into a controversial character both domestically and globally, while provided him some legitimacy gains and political latitude among hard-liners, domestically, and Islamist circles abroad. Philosopher Jahanbegloo, in his essay ‘Two Sovereignties and the Legitimacy Crisis’, describes this period ‘as the final step in a progressive shift in the Iranian revolution from popular republicanism to absolute sovereignty’.Footnote 6 Conversely, in this volume, Part Two and its three Chapters give voice and substance to this period and its new form of profane politics as they emerged after 2005. In its unholy practices, it did not produce enhanced theocracy, nor absolute sovereignty. Instead it made Iranian politics and society visibly profane, with its drug policy being the case par excellence. Jahanbegloo’s take, and that of other scholars following this line, has shed a dim light on the epochal dynamics shaping the post-reformist years (2005–13).Footnote 7 It is over this period that an ‘anthropological mutation’ took shape in terms of lifestyle, political participation, consumption and cultural order.Footnote 8 This anthropological mutation produced new social identities, which were no longer in continuity with neither the historical past nor with ways of being modern in Iran. This new situation, determined by ruptures in cultural idioms and social performances, blurred the lines between social class, rural and urban life, and cultural references among people. Italian poet, film director and essayist Pier Paolo Pasolini described the transformations of the Italian people during the post-war period – especially in the 1970s – as determined by global consumerism and not, as one would have expected, by the Weltanschauung of the conservative Christian Democratic party, which ruled Italy since the liberation from Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime in 1945. Not the cautious and regressive politics of the Catholic Church, but the unstoppable force of hedonistic consumerism represented the historical force behind the way Italians experienced life and, for that matter, politics. Taking Pasolini’s insight into historical, anthropological transformation, I use the term anthropological mutation – or, as Pasolini himself suggested, ‘revolution’ – to understand the epochal fluidity of Iranian society by the time Mahmud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005. It was not the reformist government alone that brought profound change in Iranian society. Reform and transformation were key traits of Ahmadinejad’s time in government. That is also why the period following Khatami’s presidency is better understood as post-reformism rather than anti-reformism.

Over this period, the Islamic Republic and Iranians all lived through the greatest political upheaval following the 1979 revolution: political mobilisation ahead of the June 2009 elections, especially with the rise of the Green Movement (jonbesh-e sabz); then state-led repression against protesters and the movement’s leaders, Mir Hossein Musavi and Mehdi Karroubi. The events following the presidential elections in June 2009 exacerbated the already tense conditions under which politics had unfolded in the new millennium. Allegations of irregularities, widely circulated in international and social media, led to popular mobilisation against what was perceived as a coup d’état by the incumbent government presided over by Ahmadinejad; then, the seclusion of presidential candidates Mir Hossein Musavi and Mehdi Karrubi, inter alios, changed the parameters and stakes of domestic politics irremediably. For the first time since the victory of the revolution in 1979, massive popular demonstrations took place against the state authorities. Meanwhile, the security apparatuses arrested and defused the network of reformist politicians, many of whom had, up to then, been highly influential members of the Islamic Republic. Echoing the words of president Ahmadinejad himself, he had brought ‘the revolution in the government’.Footnote 9

In this Chapter, I dwell on a set of sociocultural trends that unfolded during this period, progressively transforming Iranian society into a (post)modern, globalised terrain. It is important to situate these dynamics as they play effectively both in the phenomenon of drug (ab)use and the narrative of state interventions, the latter discussed in the next two Chapters. In particular, the ‘epidemic’ of methamphetamine use (shisheh), I argue, altered the previously accepted boundaries of intervention, compelling the government to opt for strategies of management of the crisis. The following three Chapters explore the period after 2005 through a three-dimensional approach constituted of social, medical and political layers. The objective is to examine and re-enact the micro/macro political game that animated drugs politics over this period. In this setting, drugs become a prism to observe these larger human, societal and political changes.

Addictions, Social Change, and Globalisation

With the rise of ‘neo-conservatives’ within the landscape of Iranian institutions, it is normatively assumed that groups linked to the IRGC security and logistics apparatuses, as well as individuals linked to intelligence services, gained substantial ground in influencing politics. The overall political atmosphere witnessed an upturning: religious dialogue and progressive policies were replaced by devotional zeal and ‘principalist’ (osulgar) legislations. Similarly, the social context witnessed epochal changes. These changes can be attributed in part to the deep and far-reaching impact that the reformist discourse had had over the early 2000s, in spite of its clamorous political failures. The seeds that the reformists had sowed before 2005, were bearing fruit while the anathema of Mahmud Ahmadinejad was in power. Longer-term processes were also at work, along lines common to the rest of the world. Larger strata of the population were thus exposed to the light and dark edges of a consumeristic society.Footnote 10 The emergence of individual values and global cultural trends, in spite of their apparent insolubility within the austerity of the Islamic Republic, signalled the changing nature of life and the public.

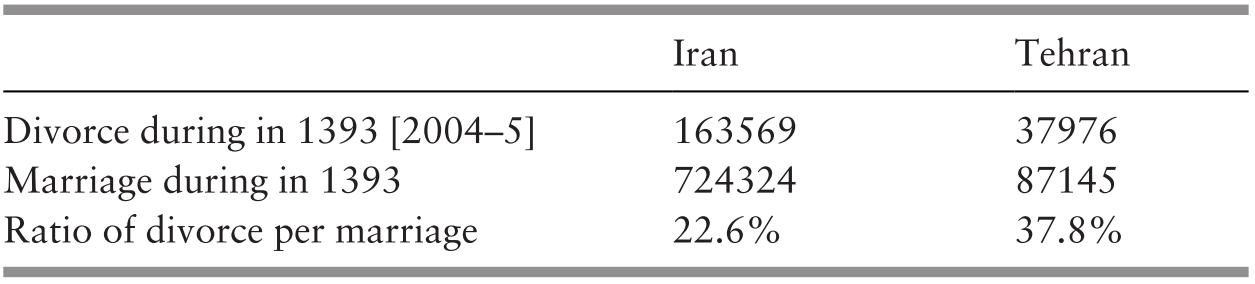

Family structure underwent a radical transformation during the 2000s. With rates of divorce hitting their highest levels globally and with a birth rate shrinking to levels comparable to, if not lower than, Western industrialised countries, the place of family and the individual was overhauled, together with many of the social norms associated with them (Table 6.1). The average child per woman ratio fell from seven in the 1980s to less than two in the new millennium, a datum comparable to that of the United States.Footnote 12 The (mono)nuclearisation of the family and the atomisation of individuals brought a new mode of life within the ecology of ever-growing urban centres. Likewise, the quest for better professional careers, more prestigious education (including in private schools), and hedonistic lifestyles, did not exclusively apply, as it had historically, to bourgeois families residing in the northern part of the capital Tehran. Along with Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s coming to power, rural, working class, ‘villain’ (dahati) Iranians entered the secular world of the upper-middle class, at least in their cultural referents.Footnote 13 More than ever before, different social classes shared a similar horizon of life, education being the ‘launch pad’ for a brighter career, made of the acquisition of modern and sophisticated products, such as luxury cars, expensive clothes, cosmetic surgeries, technological devices and exotic travels (e.g. Thailand, Dubai).Footnote 14 These elements entered surreptiously but firmly into the daily lexicon and imagination of working class Iranians, against the tide of economic troubles and the increasing visibility of social inequality.Footnote 15 A decade later, in the late 2010s, consumerism has become a prime force, manifested in the Instagram accounts of most people.

Table 6.1 Rates of Divorce in 2004–5Footnote 11

| Iran | Tehran | |

|---|---|---|

| Divorce during in 1393 [2004–5] | 163569 | 37976 |

| Marriage during in 1393 | 724324 | 87145 |

| Ratio of divorce per marriage | 22.6% | 37.8% |

Coterminous to this new popular imagery, the lack of adequate employment opportunities resulted from a combination of haphazard industrial policy, international sanctions and lack of investments, inducing large numbers of people to seek a better lot abroad. With its highly educated population, Iran topped the ominous list of university-level émigrés. According to the IMF report, more than 150,000 people have left the country every year since the 1990s with a loss of approximately 50 billion dollars.Footnote 16 After the clampdown on the 2009 protestors, many of them students and young people, this trend was exacerbated to the point of being acknowledged as the ‘brain-drain crisis’ (bohran-e farar-e maghz-ha).Footnote 17 A report published in the newspaper Sharq indicated that between 1993 and 2007, 225 Iranian students participated in world Olympiads in mathematics, physics, chemistry and computer science.Footnote 18 Of these 225, 140 are currently studying at top US and Canadian universities.Footnote 19 The case of the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who, in 2014, was the first woman ever to win the Fields Medal (the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in mathematics), is exemplary of this trend.Footnote 20 In the words of sociologist Hamid Reza Jalaipour, ‘many left the country, and those who remained in Iran had to travel within themselves’,Footnote 21 by using drugs.

The presence of young people in the public space had become dominant and, in the teeth of the moral police (gasht-e ershad) and the reactionary elements within the clergy, exuberantly active. The fields of music, cinema, arts and sports boomed during the late 2000s and physically encroached into the walls and undergrounds of Iran’s main cities. The examples provided by Bahman Ghobadi’s No one knows about Persian cats (winner of the Un Certain Regard at Cannes) and the graffiti artist ‘Black Hand’ – Iran’s Banksy – are two meaningful cases in an ocean of artistic production of globalised resonance.Footnote 22

Considering the sharpening of social conditions, both material and imagined, there was a steady rise in reported cases of depression (dépréshion, afsordegi). Indicative of the growing mental health issue is a report published by the Aria Strategic Research Centre, which claims ‘that 30 percent of Tehran residents suffer from severe depression, while another 28 percent suffer from mild depression’.Footnote 23 Obviously, the increased relevance of depression can be attributed to a variation in the diagnostic capacity of the medical community, as well as to changes and redefinition of the symptoms within the medical doctrine.Footnote 24 Yet, the fact that depression progressively came to occupy the landscape of reference and human imagery of this period is a meaningful sign of changing perception of the self and the self’s place within broader social situations.

The lack of entertainment in the public space has been a hallmark of post-revolutionary society, but its burden became all the more intolerable for a young globalised generation, with expectations of a sophisticated lifestyle, and cultural norms which have shifted in drastic ways compared to their parents. If part of it had been expressed in the materialisation of an Iranized counterculture (seen in the fields of arts and new media), the other remained trapped in chronic dysphoria, apathy and anomie, to which drug use was often the response. The prevalence of depression nationwide, according to reports published in 2014, reaches 26.5 per cent among women and 15.8 per cent among men, with divorced couples and unemployed people being more at risk.Footnote 25 In a post-conflict context, characterised by recurrent threats of war (Israeli, US military intervention), the emergence of depressive symptoms is not an anomaly. However, as Orkideh Behrouzan argues, in Iran there is a conscious reference to depression as a political datum, manifested, for instance, in the popular expression ‘the 1360s (1980s) generation,’ (daheh shasti) as the ‘khamushi or silenced generation’ (nasl-e khamushi).Footnote 26 The 1980s generation lived their childhood through the war, experienced the post-war reconstruction period and the by-products of the cultural revolution, while at the same time gained extensive access – thanks to the unintended effects of the Islamic Republic’s social policies – to social media, internet and globalised cultural products.

An event that may have had profound effects on the understanding of depression among Iranian youth is the failure of achieving tangible political reforms following the window of reformism and, crucially, in the wake of the protests of the 2009 Green Movement. The large-scale mobilisation among the urban youth raised the bar of expectations, which clashed with the state’s heavy-handed security response, silencing of opponents and refusal to take in legitimate demands. In this, the reformists’ debacle of 2009 was a sign of a collective failure justifying the self-diagnosis of depression by the many expecting their actions to bear results.

In 2009, Abbas Mohtaj, advisor to the Ministry of Interior in security and military affairs said, ‘joy engineering [mohandesi-ye shadi] must be designed in the Islamic Republic of Iran, so that the people and the officials who live in the country can appreciate real happiness’. He then carefully added that ‘of course, this plan has nothing to do with the Western idea of joy’.Footnote 27 His call was soon echoed by the head of the Seda va Sima (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) Ezatollah Zarghami, who remarked about the urgency of these measures for the youth.Footnote 28 The government had since then relaxed the codes of expression in the radio, allowing satirical programmes (tanz), perhaps unaware of the fact that political jokes and satire had already been circulating via SMS, social media and the internet, in massive amounts. More extravagantly, the government called for the establishment of ‘laughter workshops’ (kargah-e khandeh), somehow remindful of the already widespread classes of Laughter Yoga in Tehran’s parks and hiking routes.

‘People should have real joy [shadi-ye vaqe’i]’, specified an official, ‘and not artificial joy [masnu’i] as in the West’.Footnote 29 Yet, more than ever before, Iranians ventured to trigger joy artificially, notably by using drugs, medical or illegal ones. Auto-diagnosis, self-care and self-prescription had become the norm among the population, preluding to a general discourse towards medicalisation of depression and medicalised lifestyles. With antidepressants being the most prescribed drugs and 40 per cent of Iranians self-prescribing,Footnote 30 one can infer the scope of this phenomenon and, particularly, its relevance on drug policy. The appearance of dysphoria and apathy, regardless of generational divide, is also manifested in the spectacular expansion of the professional activities of mental health workers, specifically, psychotherapists, whose services are sought by ever-larger numbers of people, although mostly belonging to the middle and upper classes.Footnote 31 Examples of depressive behaviour have often been connected to drug (ab)use. The expansion of Narcotics Anonymous (mo’tadan-e gomnam, aka NA, ‘en-ay’), and its resonance with the larger public, exemplified the transition that social life, individuality and governmentality were undergoing.

Other manifestations of this new ‘spirit of the time’ encompassed addictive behaviours more broadly. For instance, groups such the Anjoman-e Porkhoran-e Gomnam (Overeaters Anonymous Society), which appear as a meeting point for people suffering from compulsive food disorders, are on the rise with more than eighteen cities operating self-help groups.Footnote 32 Similarly, sex addiction surfaced as another emblematic phenomenon. In the prudish public morality of Ahmadinejad’s Islamic Republic, there were already medical clinics treating this type of disorder.Footnote 33 A Shiraz-based psychiatrist during the 2013 MENA Harm Reduction Conference in Beirut surprised me when he said that a large number of people had been seeking his help for their sex addiction and compulsive sex, both in Shiraz and Tehran. This, he argued, was in part caused by the increasing use of amphetamine-type stimulants, which artificially arouse sexual desire, but was also a sign for the displacement of values in favour of new models of life, often inspired by commercialised products, such as films, pornography, advertisements and social media.Footnote 34

Alcoholism, too, has been acknowledged by the government as a social problem. Today there are branches of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in Iran and rehab centres for alcoholism, despite alcohol remaining an illegal substance, the consumption of which is punished severely. Beyond the diagnostic reality of these claims, it is undeniable that these changes occurred particularly during the years when president Ahmadinejad and his entourage were in government. Indeed, many of the policies and laws in relation to controversial issues, such as on transsexuality and alcoholism, took form during the post-reformist years.Footnote 35 These transformations occurred not as a consequence of the government’s performance and vision, but rather as a rooting and continuation of secular, global trends, many of which began during the reformist momentum, to which, awkwardly but effectively, the populist government concurred. This was a new mode of political and social change, one that could be called reforms after reformism. Once again, a counter-intuitive phenomenon was at play.

The ‘Crisis’ of Shisheh and Its Narratives

If one combines the widespread use of antidepressant drugs with the impressive rise in psychoactive, stimulant and energizing drugs, most notably shisheh, the picture inevitably suggests a deep-seated transformation in the societal fabric and cultural order during the post-reformist era.Footnote 36

In early 2006, officials started to refer to the widespread availability of psychoactive, industrial drugs (san’ati) through different channels, including satellite TVs and the internet.Footnote 37 They said they had little evidence about where these substances originated from and how they were acquired.Footnote 38 Although ecstasy – and generally ATSs – had been available in Iran for almost a decade, its spread had been limited to party scenes in the urban, wealthy capital.Footnote 39 The appearance of methamphetamines (under the name of ice, crystal, and most notably, shisheh, meaning ‘glass’ in reference to the glass-like look of meth) proved that the taste for drugs among the public was undergoing exceptional changes, with far-reaching implications for policy and politics.Footnote 40

The most common way to use meth is to smoke it in a glass pipe in short sessions of few inhalations. It is an odourless, colourless smoke, which can be consumed in a matter of a few seconds with very little preparation needed (Figure 6.1). In one of the first articles published about shisheh in the media, a public official warned that people should be careful about those offering shisheh as a daru, a medical remedy, for lack of energy, apathy, depression and, ironically, addiction.Footnote 41 By stimulating the user with an extraordinary boost of energy and positive feelings, shisheh provided a rapid and, seemingly, unproblematic solution to people’s problems of joy, motivation and mood. Its status as a new drug prevented it from being the object of anti-narcotics confiscation under the harsh drug laws for trafficking. After all, the official list of illicit substances did not include shisheh before 2010, when the drug laws were updated. Until then the crimes related to its production and distribution were referred to the court of medical crimes, with undistressing penalties.Footnote 42

Figure 6.1 Meanwhile in the Metro: Man Smoking Shisheh.

The limited availability of shisheh initially made it too expensive for the ordinary drug user, while it also engendered a sense of classist desire for a product that was considered ‘high class [kelas-bala]’.Footnote 43 As such, shisheh was initially the drug of choice among professionals in Tehran, who in the words of a recovered shisheh user, was used ‘to work more, to make more money’.Footnote 44 Yet after its price decreased sensitively (Figure 6.2), shisheh became popular among all social strata, including students and women, as well as the rural population. By 2010, it was claimed that 70 per cent of drug users were (also) using shisheh and that the price of it had dropped by roughly 400 per cent compared to its first appearance in the domestic market.Footnote 45 It was a ‘tsunami’ of shisheh use which took both state officials and the medical community unprepared, prompting some of the people in the field to call for ‘the creation of a national headquarters for the crisis of shisheh’, very much along the lines of the ‘headquartisation’ mentality described in the early post-war period.Footnote 46 This new crisis within the field of drug (ab)use was the outcome of a series of overlapping trends that materialised in the narratives, both official and among ordinary people, about shisheh. The narrative of crisis persisted after 2005 in similar, or perhaps more emphatic, tones.

This new substance differed significantly from previously known and used drugs in Iran. In contrast to opium and heroin, which tended ‘to break the spell of time’ and diminish anxiety, stress and pain, making users ultimately nod in their chair or lie on the carpet, methamphetamines generally boost people’s activities and motivate them to move and work, eliminating the need for sleep and food.Footnote 47 In a spectrum inclusive of all mind-altering substances, to put it crudely, opiates and meth would be at the antipodes. All drugs and drug use, wrote the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, have to do with ‘speed, modification of speed … the times that become superhuman or subhuman’.Footnote 48 Shisheh had to do with time, people’s perception of time’s flow; it was the new wonder drug of the century, with its mind-altering speed and physical rush as distinctive emblems of (post)modern consumption.

Opiates derive from an agricultural crop, the poppy, whereas methamphetamines are synthetized chemically in laboratories and therefore do not need agricultural land to crop in. Between 2007 and 2010, Iran topped the international table of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine legitimate imports, with quantities far above expected levels according to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB).Footnote 49 Pseudoephedrine and ephedrine are both key precursors for meth production, the rest of the chemical elements being readily available in regular stores and supermarkets. With Iran’s anti-narcotic strategy heavily imbalanced towards its borders with Afghanistan and Pakistan, the production of shisheh could occur, with few expedients and precautions, ‘at home’. In fact, it did not take long before small-scale laboratories – ante tempore versions of Walter White’s one in Breaking Bad – appeared within borders, inducing the head of the anti-narcotic police to declare, ‘today, a master student in chemistry can easily set up a laboratory and, by using the formula and a few pharmaceutical products, he can obtain and produce shisheh’.Footnote 50 In 2010, the anti-narcotic police discovered 166 labs, with the number increasing to 416 labs in 2014.Footnote 51 The supply reduction operations could not target domestic, private production of meth, because this new industry was organised differently from previous illicit drug businesses and could physically take place everywhere.

The high demand for meth and the grim status of the job market guaranteed employment in the ‘shisheh industry’.Footnote 52 A ‘kitchen’ owner who ran four producing units in Southern Tehran revealed that the prices of shisheh had shrunk steadily because of the high potential of production in Iran. In his rather conventional words, ‘young chemical engineers, who cannot find a job … work for the kitchen owner at low prices’, and, he adds, ‘precursors and equipment are readily available in the capital’s main pharmaceutical market at affordable prices’.Footnote 53 The shisheh that is produced is sold domestically or in countries such as Thailand under the local name of yaa baa, or Malaysia and Indonesia, where there is high demand for meth. The number of Iranian nationals arrested in international airports in Asia hints clearly at this phenomenon.Footnote 54

Logically, shisheh and the shisheh economy appealed particularly young people, who exploited the initial confusion and lack of legislative norms. At the same time, while opium and heroin had largely remained ‘drugs for men’ (although increasing numbers of women were using them in the early 2000s), shisheh was very popular among women. For instance, the use of shisheh was often reported in beauty salons and hairdressers, allegedly because of its ‘slimming’ virtue. In similar fashion, its consumption was popular among sportsmen, both professional (e.g. football players and wrestlers) and traditional/folkloric (e.g. zurkhaneh).Footnote 55 Its consumption appealed to categories of people enchanted with an idea of life as an hedonistic enterprise often governed by the laws of social competition, something that differed ontologically and phenomenologically from Islamising principles.

Reports emerged also about the use of shisheh among students to boost academic performance. By making it easy to spend entire nights studying and reviewing, especially among those preparing for the tough university entry examination (konkur), shisheh had gained popularity in high schools and universities. The shrinking age of drug use, too, has been factual testimony of this trend.Footnote 56 In an editorial published in the state-run newspaper, a satirist announced that, in Iran, ‘the modern people have become post-modern. And this latter, we know, is industrial and poetical’ and he longed for ‘the old good days of the bangis [the hashish smoker]’.Footnote 57 Shisheh epitomised the entry into the post-modern world, an epochal, perhaps irreversible, anthropological mutation. In view of this changing pattern of drug (ab)use, the authorities realised, slowly and half-heartedly, that the policies in place with regard to treatment of injecting drug users – harm reduction as implemented up until then – had no effect on reducing the harm of shisheh. Harm reduction could not target the ‘crisis’ of shisheh, which unwrapped in a publicly visible and intergenerational manner different from previous drug crises. Its blend, in addition, with changing sexual mannerisms among the youth, aggravated the impotence of the state.Footnote 58

Sex, Sex Workers and HIV

With drug use growing more common among young people and adolescents, people acknowledged shisheh for its powerful sexually disinhibiting effects, which, in their confessions during my ethnographic fieldwork, ‘made sex [seks] more fun [ba hal] and good [khoob]’. Equally, the quest for sex with multiple partners sounded appealing to those using shisheh, engendering the preoccupation (when not the legal prosecution) of the state. With moral codes shifting rapidly and the age of marriage rising to 40 and 35 respectively for men and women, pre-marital unprotected sex became a de facto phenomenon.Footnote 59

The combination of sex and drugs resonated as a most critical duo to the ears of policymakers, one that made Iran look more like a land of counterculture than an Islamic republic. Yet, because premarital sex was deemed unlawful under the Islamic law, the issue of sex remained a much-contested and problematic field of intervention for the state. Despite the repeated calls of leading researchers, the state institutions seemed incapable, if not unprepared, to inform and to tackle the risk of pre-marital unprotected sex. This attitude accounted, in part, for the ten-fold increase in sexually transmitted diseases in the country during the post-reformist period.Footnote 60

Many believed that while harm reduction policies were capable of tackling the risk of an HIV epidemic caused by shared needles, these measures were not addressing the larger part of the population experiencing sexual intercourse outside marriage (or even within it), with multiple partners, and without any valuable education or information about sexually transmitted diseases. The director of the Health Office of the city of Tehran put it in this statement during a conference, ‘we are witnessing the increase in sexual behaviour among students and other young people; one day, the nadideh-ha [unseen people] of today will be argument of debate in future conferences’.Footnote 61 The rate of contagion was expected to increase significantly in the years ahead, a hypothesis that was indeed confirmed by later studies.

As for the risk of HIV epidemics emerging from Iran’s unseen, but growing population of female sex workers, the question was even more controversial. Sex workers, in the eye of the Islamic Republic, embodied the failure of a decadent society, one which the Islamic Revolution had eradicated in 1979, when the revolutionary government bulldozed the red-light districts of Tehran’s Shahr-e Nou to the ground and cleansed it – perhaps superficially – of prostitutes and street walkers.Footnote 62 Government officials had remained silent about the existence of this category, with the surprising exception of Ahmadinejad’s only female minister Marzieh Vahid-Dastjerdi. The Minister of Health and Medical Education broke the taboo publicly stating in front of a large crowd of (male) state officials, ‘every sex worker [tan forush, literally ‘body seller’] can infect five to ten people every year to AIDS’.Footnote 63 The breaking of the taboo was a part of the attempt to acknowledge those widespread behaviours that exist and that should be addressed with specific policies, instead of maintaining them in a state of denial.Footnote 64 The framing of the phenomenon rested upon the notion of ‘risk’, ‘emergency’ and crisis. The opening of drop-in centres for women was a step in this direction, albeit initially very contested by reactionary elements in government. In 2010, the number of these centres (for female users) increased to twelve, the move being justified by the higher risk which women posed to the general population: ‘a man who suffers from hepatitis or AIDS can infect five or six persons, while a woman who injects drugs and makes ends meet through prostitution may infect more persons’.Footnote 65

The government, however, remained unresponsive to this call. Mas‘ud Pezeshkian – former Minister of Health under the reformist government (2001–5) – commented that ‘until the profession [of sex worker] is unlawful and against the religious law [shar’] there should be no provision of help to these groups’.Footnote 66 The result of this contention was a lack of decision and coherence about the risk of an HIV epidemic. According to an official report, the majority of groups at risk of sexual contagion (e.g. sex workers, homeless drug users) were still out of reach of harm reduction services.Footnote 67 If drug users in prison embodied the main threat (or crisis) during the reformist period, the post-reformist era had been characterised by the subterfuge of commercial sex and unprotected sexual behaviour, with the incitement of stimulant drugs such as shisheh.

A study published by Iran’s National AIDS Committee within the Ministry of Health and Medical Studies – with the support of numerous international and national organisations – revealed that only a small percentage (20 per cent) of the population between fifteen and twenty-four years old could respond correctly to questions on modes of transmission, prevention methods and HIV.Footnote 68 The crisis of this era was propelled, one could say, through sex, but also based on a certain ignorance of safe sexual practices, because of unbroken moral taboos.Footnote 69

The Disease of the Psyche

The changing nature of drug (ab)use and sexual norms – in the light of what I referred to as the broad societal trends of the post-reformist years – rendered piecemeal and outdated the important policy reforms achieved under the reformist mandates. In fact, shisheh could not be addressed with the same kind of medical treatment used for heroin, opium and other narcotics. Treatment of shisheh ‘addiction’ required psychological and/or psychiatric intervention, with follow-up processes in order to guarantee the patient a stable process of recovery.Footnote 70 This implied a high cost and the provision of medical expertise in psychotherapy that was lacking, and already overloaded by the demand of the middle/upper classes. Besides, methadone use among drug (ab)users under treatment engendered a negative side effect in the guise of dysphoria and depression, which could only partially be solved through prescription of antidepressants. The recurrence to shisheh smoking among methadone users in treatment became manifest, ironically and paradoxically, as a side effect of methadone treatment and a strategy for chemical pleasure.Footnote 71

The mental hospitals were largely populated by drug (ab)users, the majority of whom with a history of ‘industrial drugs’ use, a general reference to shisheh.Footnote 72 The rise in referrals for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, suicidal depression and other serious mental health issues needed to be contextualised along these trends. Suicide, too, remained a problematic datum for the government as it revealed the scope of social distress and mental problems emerging publicly.Footnote 73 But the increase of shisheh use markedly brought the question of drugs into the public space, with narratives of violence, family disintegration, abuse and alienation becoming associated with it. Although drug scares have always circulated in Iran (as elsewhere), they have mostly regarded stories of decadence, overdose, and physical impairment. They rarely concerned schizoid and violent behaviour in the public. With shisheh, drug use itself became secondary, while the issue of concern became the presence of highly intoxicated people, with unpredictable behaviours, in the public space.Footnote 74 As a law enforcement agent in the city of Arak confessed, ‘the heroini shoots his dose and stays at his place, he nods and sleeps; these people, shishehi-ha [‘shisheh smokers’], instead, go crazy, they jump on a car and drive fast, like Need 4 Speed,Footnote 75 they do strange things [ajib-o gharib] in the streets, talk a lot, get excited for nothing, or they get paranoid and violent’.Footnote 76 With this picture in mind, it does not surprise that Iran has had the world’s highest rate of road accidents and bad driving habits.Footnote 77 The trend of road accidents became also an issue of concern to the public (and the state), in view of investigations revealing, for instance, that ‘20 per cent of trucks’ drivers are addicted’, or that ‘10 per cent of bus drivers smoke shisheh with risks of hallucination and panic’ while behind the wheel.Footnote 78 Stories emerged also about violent crimes being committed by people on shisheh, establishing a worrying association between this substance, violent crimes (often while in a paranoid state) and, ultimately, long-term depression and mental instability.Footnote 79 More than being a sign of a material increase in violence, these stories are telling about the framing of this new substance under the category of crisis and emergency.

At the same time, shisheh became a cure for depression and lack of energy, also overcoming the urban–rural divide. I had confirmation of this more than once during my time spent in a small village in central Iran between 2012 and 2015. The shepherd known to my family since his adolescence, one night arrived in his small room, prepared some tea and warmed up his sikh (short skewer) to smoke some opium residue (shireh) which he had diligently prepared in the preceding weeks. One of the workers from a nearby farm, a young man of around twenty, came in and after the usual cordial exchanges, sat down, took his small glass pipe and smoked one sut of shisheh.Footnote 80 After their dialogue about the drop in sheep meat price in the market, the shepherd asked for some advice, ‘you see, it has been a while I wanted to give up opium, because you know it’s hard, I have smoked for thirty years now, and I feel down, without energy [bi hal am] all the time. Do you think I should put this away [indicating the opium sikh] and instead try shisheh?’.Footnote 81

In this vignette, the use of shisheh represents a response to the search for adrenaline, libido and energy in the imaginatively sorrowful and melancholic timing of rural life. Many others, unlike my shepherd friend, had already turned to shisheh in the villages, whether because of its lower price, its higher purity or opium’s adulterated state.Footnote 82 The government invoked the help of the Village Councils – a state institution overseeing local administration – in an attempt to gain control over Iran’s vast and scattered villages, but with no tangible results, apart from sporadic anti-narcotics campaigns.Footnote 83 By the late 2000s, drug adulteration (especially opium) increased substantially, encouraging drug users to shift to less adulterated substances – for example, domestically produced shisheh – or to adopt polydrug use. This caused a spike in the number of drug-related deaths, up to 2012, due principally to rising impurity (Figure 6.3).Footnote 84 The cost of using traditional drugs like opium and heroin was becoming prohibitive and less rewarding in terms of pleasure. Inevitably, many shifted to shisheh.

Figure 6.3 Drug-Use-Related Deaths

Conclusions

The phenomenon of drug use intersected over this period with long-term transformations that had bubbled below the surface of the governmental rhetoric and imagery of the Islamic Republic. Changing patterns of drug consumption, hence, was not the simple, consequential effect of new drug imports and lucrative drug networks, although these played their role in facilitating the emergence of new drug cultures. From the late 2000s onwards, drugs affected, and were affected by, broader trends in society, such as changing sexual norms, consumption patterns, social imagination, economic setting and ethical values. This represented a fundamental ‘anthropological mutation’, for it changed the way individuals experienced their existences in society and shaped their relation to the surrounding world. By this time, new cultural, ethical values gained traction, relegating to the past the family-centric, publicly straight-laced way of being in the world. The pursuit of sensorial pleasure, personal recognition and aesthetic renewal became totalizing – and totalitarian – in more rooted and uncompromising ways than the clerical ideology preached by the ruling class in the Islamic Republic. Not the ideology of the clergy, but the driving force of post-modern consumerism was the totalitarian drive of social change. To this epochal moment, the state responded haphazardly and incongruently, mostly unaware or unconcerned of what this transformation signified and in what ways it manifested new societal conditions where the old politics and rhetoric had effect. Rather than attempting a reconfiguration of the new cultural, social and ethical situation, the political order coexisted with the coming of age of new subjectivities, without recognizing them effectively.

Drugs, and shisheh in particular, were a manifestation of the profound changes taking place over this period to which the state reacted with hesitation and through indirect means. This chapter focused on social, cultural and human (trans)formations from the mid 2000s onwards, with an especial attention to the rise of shisheh consumption and its contextual psychological, sexual and economic dimensions. The next two Chapters dwell on how the state countered this changing drug/addiction phenomenon. An emblem of the anthropological mutation in lifestyle, imagery, values and flow of time, shisheh contributed to the change in political paradigm with regard the public place. It also brought about a shift in drug (ab)use and in the governance of drug disorder. Shisheh, hence, is both cause and effect of these transformations.

Introduction

One hot morning of early September 2014, Tehran’s University of Medical Sciences hosted the Eighth International Congress on Addiction Science. The venue was that of important scholarly events – the Razi (Rhazes) Conference Hall – located near the symbol of modern Tehran, the Milad Tower. A lively movement of people, mostly young students, male and female, animated the premises of the building, where the registration procedures and distribution of materials of various kinds, including breakfast, was taking place. One could tell, prima facie, that the schedule was expected to be dictated by some high-ranking, prominent participation, particularly among government officials.

The conference, an attendant involved in the organisation revealed to me, was meant to be ‘a new start’ for Iran’s drug policy and the academic community, especially in its engagement with its Western counterparts. The conference panels narrated the underlying dynamics within the policy community, in the wake of the eclipse of the post-reformist government. As such, the conference was a telling vignette of the features and apparent paradoxes of post-reformist drug policy.

At 8AM, I had successfully snuck into a panel on ‘Women and Addiction’, which occurred behind closed doors; if truth be told, I had to use my network in the UNODC to get access to the room where a female ministerial advisor did not want her statements to be reported publicly. The audience was almost entirely composed of women whose stricter type of hijab was telling of their employment post in state institutions. Despite the novelty of the issues debated in the panel, with off-the-records data being revealed, after the second presentation my attention drifted to a concomitant panel in Hall 3, titled ‘Harm Reduction among Drug Users’.

Since this panel included influential officials in the policy community and well-known advocates of harm reduction, it seemed a (political) manifestation not to be missed. I left the panel on Women and Addiction and moved to the opposite room where the panel on Harm Reduction was taking place. On this panel were prominent members of the policy community from different ministries and the DCHQ, plus a number of high-ranking officials in the audience. The presenters were Dr Ahmad Hajebi, Director of Mental Health Office at the Ministry of Health; Dr Mehdi Guya, Director of the Centre of Infectious Diseases at the Ministry of Health; and Farid Barrati-Sadeh, Director of Treatment at the DCHQ.

Despite the friendly tone of the exchanges, one could sense the latent animosity between the participants. As the panel contemplated a Q&A session, the comments remained mostly cursory, provocative and colourful. But the last speaker, Farid Barrati-Sadeh, an outspoken official with regular presence in the media, opted to use the time allocated for his presentation in order to, as he said, ‘clarify and point out some of the contradictions in the exposition of our friends’. From the very outset of his presentation, the speaker remarked that the current implementation of drug laws was not only haphazard and fragmentary, but also contradictory in itself. This, he argued, was due to the lack of interest of his ‘friends’ in the Ministry of Health, who were ‘unwilling to engage with harm reduction and keep on criticising the setad [i.e. DCHQ] for every problem in this country’. Raising the tone of his voice, he accused the other speakers who preceded him, Dr Mehdi Guya and Dr Ahmad Hajebi, ‘of refusing to adopt new protocols for the new treatment camps under the 2010 law’, a law approved by the ‘organs of the Islamic Republic and has the authoritative support of the Leader of the Revolution’, that is to say Ayatollah Khamenei. Comments of disapproval could be heard from the front line of the conference hall, where the other speakers sat. The presentation of the DCHQ official extended in a quid pro quo with the other speakers, with mutual accusations of incoherence, hypocrisy and managerial unwillingness/incapacity. It then terminated when Minoo Mohraz, Iran’s internationally prominent HIV/AIDS scholar, intervened on the panel floor, taking the microphone away from one of the speakers and, with severity, reprimanding all the panellists about their rowdy behaviour and ‘their inconclusive messiness’.Footnote 1 She then remarked that

as a person who is not ejrai [executive, i.e. a public official] – I am a scientist [adam-e ‘elmi] – I have duties towards the people, whatever you want to say and discuss about, I ask you to sit together and discuss. People cannot bear this anymore … I ask you to solve this and to support harm reduction; … use the budget to promote useful programmes, not to establish compulsory treatment camps [kamp-e darman-e ejbari].

For an external viewer, the contest might appear one centred around budgetary allocations between different state institutions entrusted with harm-reduction duties. It soon became explicit, however, that budgetary discussions were only a side note on the more equivocal and vexed page of ‘compulsory treatment’ and the ‘camps’ in general.

The 2010 Drug Law Reform

The roots of the diatribe among the panellists went back to the text of the 2010 drug law reform. This reform, approved after long and complex negotiations within the Expediency Council, emblematised the developments with regard to drug (ab)use under the presidency of Mahmud Ahmadinejad. The conference debates, although taking place after the demise of Ahmadinejad, actually concentrated on the experiences of the last government. In a way, the debate itself was taking place so overtly – and loudly – because of the political change represented by the election of Hassan Rouhani in 2014, which had resulted in a lost grip on the institutional line of command within the policymaking institutions. Criticism was accordingly welcomed as a sign of renewal, even when the people in charge at a bureaucratic level remained, largely, the same.

The 2010 law reform materialised the inherent idiosyncrasies of the politics of drugs in the twenty-first century. The law itself provides a localised example of the paradigm of government with regard to the crises that the post-reformist governments had faced. Post-reformism reflects the scenario left by the demise of governmental reformism following Khatami’s last presidential term and its unsuccessful efforts at triggering political reform. Under the umbrella of post-reformism, I indicate those attempts at governance which fall short of calling overt reforms, but which produce diffused changes within political practice. It encompasses ideologically strong administrations calling for a revolution in government while instilling a grassroots form of management of social and political conflicts (i.e. Ahmadinejad); as well as centrist, business-oriented administrations pledging moderate, slow and timidly progressive civic change (i.e. Rouhani).

The year 2010 was momentous in formulating a new approach, called post-reformism, regarding illicit drugs. Discussions of the new anti-narcotic laws were ongoing and, as the country had already built the infrastructure for large-scale interventions, the new political formula had the potential to be ground-breaking. Instead, the text of the 2010 reform of the anti-narcotic law reproduced the multiple ambiguities of harm reduction (and public policy generally) in Iran, the law itself becoming the contested ground between different governmentalities towards what was defined ‘addiction’, as partly manifested in the diatribe reported at the beginning of this Chapter. It was an oxymoronic law producing oxymoronic governance.

Apart from updating the list of narcotic drugs with the insertion of new synthetic, industrial drugs, notably shisheh, the key changes in the new texts concerned Article 15 and Article 16.

Abstract from the 2010 Drug Law Reform

Article 15 – The addict is required to refer to legitimate state [dowlati], non-state [gheyr-e dowlati], or private [khosusi] centres, or to treatment and harm reduction grassroots organisations [sazman-ha-ye mardom-nahad], so to apply to addiction recovery. The addict who enrols in one of the above-mentioned centres for his/her treatment and has obtained an identification [gavahi] of treatment and harm reduction, as long as he/she does not publicly manifest addiction [tajahor be e‘tyad], is suspended [mo‘af] from criminal sanctions. The addict, who does not seek treatment of addiction, is a criminal.

Note 2 – The Ministry of Welfare and Social Security is responsible … to cover the entire expenses of addiction treatment of destitute [bi-beza‘at] addicts. The government is required to include this in the yearly sections of the budget, and to secure the necessary financial credits.

Article 16 – Addicts to narcotic drugs and psychoactive substances, included in Articles 4 and 8, who do not have the identification mentioned in Article 15 and who are overtly addicted, must be maintained, according to the decision of the judicial authority, for a period of one to three months in a state centre licenced with treatment and harm reduction. The extension of the maintenance period is permitted for a further three months. According to the report of the mentioned centre and based on the opinion of the judicial authority, if the addict is ready to continue treatment according to Article 15, he/she is permitted to do so according to the aforementioned article.

Note 2 – The judicial authority, for one time, can suspend the sanction against the addict for a six-month period, given appropriate guarantees and the allocation of an identification document mentioned in Article 15, and can refer the addict to a centre as enunciated in this aforementioned article. The aforementioned centres are responsible to send a monthly report on the trend of treatment of the addict to the judicial authority, or to his representative …

Note 3 – Those contravening the duties enunciated in Note 2 of this article can be condemned to incarceration from one day to six months.Footnote 2

Several issues emerge from analysing these two articles. First, the 2010 reformed law legitimised harm-reduction practices applied since the early 2000s, including them in an institutional legal order. The law explicitly mentions the legitimacy of ‘harm reduction’, although it does not specify what falls under this label. Second, the law institutes centres for the implementation of harm reduction; these centres, it is spelled out, include both state centres and private clinics, as well as charitable and grassroots organisations. In other words, Article 15 of the 2010 law legitimises those agents already active in the field of drug (ab)use, explicating their social role with regard to addiction. It enshrines their function according to what I define in the Chapter 8, the governmentalisation of addiction. More crucially, the 2010 law establishes a distinction between those drug (ab)users who are willing to seek treatment and refer to a recognised institution (e.g. clinic, camp), as contemplated in Article 15, and those who do not seek treatment, who therefore become subject to Article 16. This has two main effects: on the one hand, the new law protects registered addicts since it provides them an identification card, allowing them to carry limited quantities of methadone with them – in the case of MMT patients – or to seek harm reduction treatment – in the guise of clean syringes and needles – without the risk of police arrest. On the other hand, those addicts who do not register for treatment in a recognised institution, are still liable of a crime – the everlasting crime of addiction – and could be forcibly sent to state-run compulsory camps (kamp-e maddeh-ye 16). Their crime is that of being intoxicated in a visible manner, publicly (tajahor).

Concomitant to the new law, governance of drug consumers adopted new analytical frames, which follow the logic of what I define oxymoronic governance. Drug (ab)users were now described and treated as ‘patient criminal [mojrem-e bimar]’ who, if not under treatment, ‘will be object a court ruling on compulsory treatment, to which the police will enforce a police-based treatment [darman-e polis-madar]’.Footnote 3 What was formerly a criminal – and perhaps the emblem of a criminal – the ‘addict’, is now a patient whose crime resides in his condition, his dependency to an illegal substance. This new subjectivity is the object of institutional care, not through the expertise of medical professionals alone, as would be for other patient types, and not through the whip of policemen, as would occur for simple criminals. Dealing with the drug (ab)user produces a new figure within state law and order, that of the therapeutic police, a force which treats disorder of an ambivalent kind. This enmeshment of criminalisation and medicalisation provides a cursory glance at the new governmentality under post-reformism. By adopting a medical lens, through a law-and-order approach, the therapeutic police is where policing encounters addiction. Its means are, from a practical point of view, in continuity with orthodox policing. ‘Quarantine’, used during the 1980s, came back into vogue when officials addressed the need to isolate risky groups, such as IDUs and HIV-positive individuals.Footnote 4 Quarantine, a quintessential medical practice with mandatory enforcement, was not a metaphorical hint, but an actual practical disposition. Police and medicine needed cooperation, at close range, on the matter of drugs. This new mode of intervention was rooted in the framing of the addict as a mojrem-e bimar, a ‘patient-criminal’, who needed to be countered by a ‘therapeutic police’.

In line with the post-reformist vision based on the ‘therapeutic police’ and governmentalisation of addiction, the new law contemplated direct intervention in tackling addiction, by forcing into treatment those who were reluctant, or unable, to do so. If, at the level of political discourse, the new drug law was characterised by the concomitance of insoluble traits (i.e. assistance and punishment), it did not mean that its practical effects were totally unintended. While addiction was publicly recognised as a ‘disease’ and medical interventions were legitimated nationwide through public and private clinics, the figure of the drug (ab)user remained inherently deviant and stigmatised among the official state cadre, especially when connoted with the disorderly – and dysfunctional – features of poverty and social marginalisation. The law intended to manage disorder instead of bring about order; to govern crisis instead of re-establishing normalcy, whatever the content of the latter proved to be.

The provisions of the law seem to respond, among other things, to the necessities dictated by the expanding crisis of shisheh in the public space as described in Chapter 6. Public officials during the late 2000s seemed to agree that people abusing methamphetamines could not be cured, or that a cure for them was either unavailable or too expensive to be provided on a large scale.Footnote 5 This persuaded cadres of the state to seek mechanisms of intervention that were not necessarily coherent with each other, but which, from a public authority perspective, responded to the imperatives of public order. In other words, they adopted an oxymoronic form of politics, the adoption of otherwise incompatible means.

The text of Article 16 stresses the need to intervene against ‘those addicted publicly’. It envisions public intervention vis-à-vis the manifest effects of drug use, materialised by disorderly presence in the streets, noisy gatherings of drug users, vagrancy and mendicancy.Footnote 6 This interpretation of the shisheh ‘crisis’ was rooted on a law enforcement model, updated with a new medical persuasion – that of the incurability of shisheh addiction.Footnote 7 Since methadone substitution programmes and classical harm-reduction practices (i.e. needle exchange) were inadequate to respond to the treatment of shisheh users, the state resorted to a practice of isolation and confinement, this time, however, not through incarceration in state prisons. Instead, it gave birth to a new model, that of the compulsory state-run camps, a paradigm of government of the drug crisis that exemplified, in nuce, the post-reformist governmentality on crisis.

Therapeutic Police: Compulsory Treatment Camps

Part of the diatribe portrayed in the conference vignette opening this chapter reflected the opposing views existing on the role of the therapeutic police and the status of compulsory treatment camps. Since the implementation of the 2010 reform – but to a minor degree since Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005 – the state regularly intervened to collect homeless drug users and confine them to compulsory camps, much to the astonishment of those who had worked towards the legitimation of harm reduction.Footnote 8 In reality, part of the medical community and NGO sector – notably the NGO Rebirth (Tavalod-e Dobareh) – had supported the text of the 2010 law on the basis that it recognised the legitimacy of treatment and harm reduction, as a prelude towards decriminalisation of addiction. Compulsory treatment camps, supporters of the 2010 law argued, were the necessary venue to medicalise addiction among those who could not be persuaded to seek treatment. It would be, they added, the safest and fastest way to introduce the addict into the cycle of treatment, facilitating recovery.Footnote 9 Yet, therapeutic policing relied on a system which paid little attention to recovery. Centres managed by law enforcers often unveiled situations of degradation and abuse, which prompted several officials to publicly express their opposition to this model, on the grounds that it neither brought results, nor offered humanitarian support.Footnote 10

Operating since the late 2000s, compulsory treatment camps have been active in sixteen regions. Although the media and officials refer to them as ‘camps’, the official name for them, hitherto, has been ordugah, which translates in English as ‘military camp’. One official lambasted the use of this term as ‘unappreciative’ of the government’s effort to treat drug addicts.Footnote 11 The origins of this institutional model can be traced back to the early years of the Ahmadinejad government.Footnote 12 Their purpose, however, became antithetical to the original idea. In 2007, the new head of the DCHQ, C-in-C Ahmadi-Moghaddam, already announced that ‘the addict must be considered a patient-criminal [mo‘tad-e mojrem] who, if he is not under treatment, the court will rule for him compulsory treatment [darman-e ejbari] and the police will be the executor of a police-based treatment’. He then added, ‘we have to build maintenance camps [ordugah-e negahdari]; the NAJA has already built camps for the homeless and vagrants, which in the opinion of treatment officials can be used as maintenance camps for addicts for a certain period’.Footnote 13 This announcement is an ante tempore elucidation of the 2010 law model. It coincided with the appointment of the head of the police as director of the DCHQ. The fact that, genealogically, the compulsory treatment camps were formerly camps for the internment of vagrants and homeless people, unveiled the primary concern of the state regarding the management of public order.Footnote 14

Much like the 1980s, the officials adopted a language that underlined the need to ‘quarantine’ problematic drug (ab)users.Footnote 15 Yet, this rhetoric did not prelude to a return to past forms of intervention; the post-reformist ‘quarantine’ envisaged the presence and ‘supervision of doctors, psychologists, psychiatrists and infection experts as well as social workers’ and the referral, after the period of mandatory treatment, to ‘the non-state sector, NGOs and treatment camps’.Footnote 16 The rationale, it was argued, was to introduce so-called dangerous addicts and risky groups into the cycle of treatment, the first of which was managed by the state, through the therapeutic police, while afterwards it was outsourced to non-state agents, through charities, NGOs and civil society organisations.

The government made large budgetary allocations to the NAJA in furtherance of the construction of compulsory camps. In 2011, 81 billion tuman (equivalent to ca. USD 8 million), were allocated to the Ministry of Interior, to build a major compulsory treatment camp in Fashapuyieh, in the southern area of the capital.Footnote 17 This first camp was designed to inter around 4,000 addicts in the first phase (with no clear criteria of inclusion), with the number going up to 40,000 once the entire camp had been completed.Footnote 18 Other camps were expected to be operating in major regions, including Khorasan, Markazi, Fars and Mazandaran.Footnote 19 A gargantuan project resulted from the implementation of Article 16 of the 2010 law. The deputy director of the DCHQ, Tah Taheri, announced that ‘about 250,000 people needed to be sent to the compulsory treatment camps by the end of the year’ as part of the governmental effort to curb the new dynamics of addiction.Footnote 20 The ambitious plan had the objective of unburdening the prison organisation from the mounting number of drug offenders, a move likely to also benefit the finances of the Judiciary and the NAJA, always overwhelmed by drug dossiers and structurally incapable of proceeding with the drug files.

The nature of the compulsory treatment camps resembled more that of the prison than anything else. Legislation on illicit drugs mandated the separation of drug-related criminals from the rest of the prison population. Authorities failed to implement the plan on a large scale, leaving the prisons filled with drug offenders.Footnote 21 Up to 2010, the prison population had increased to 250,000 inmates, a number that, given the state’s commitment not to incarcerate drug addicts, was symptomatic of an underlying duplicity, or ambivalence, in state intervention.Footnote 22 Mostafa Purmohammadi, a prominent prosecutor, identified ‘addicted prisoners’ as one of the main concerns of the prisons and he advised the implementation of mandatory treatment camps to alleviate the dangers and troubles of the prison system.Footnote 23 Consequently, for the first time in many decades, the prison population decreased by some 40,000 people in 2012, reaching the still cumbersome number of 210,000 inmates. This datum, heralded as evidence of success by the post-reformist government, could be actually traced back to the introduction, on a massive scale, of the compulsory camps for drug (ab)users, managed by the therapeutic police. The actual population confined in state institutions for charges of criminal behaviour (including public addiction), had actually mounted to almost double the size of prisons prior to the 2010s.

Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the overall number of prisoners had increased by six times, and the number of those incarcerated for drug-related charges by fourteen times, with one in three court cases allegedly being drug-related in 2009.Footnote 24 If, during the reformist period, the introduction of harm reduction had been prompted, among other things, by the HIV epidemic in prisons, the post-reformist government under Ahmadinejad reacted with outrage against the waste of money that the incarceration of drug offenders represented. An official from the Prison Organisation in 2010 outlined that ‘the maintenance of every prisoner costs 3,000 tuman per day … which is equivalent to a waste of public capital of around 450,000,000 tuman per day’.Footnote 25 Researchers from state institutions demonstrated that treating drug (ab)users would cost an average of fifteen times less than incarcerating them. In view of the ratio of drug (ab)users in prison – an astonishing 70 per cent – the creation of the compulsory treatment camps provided an alternative device for the management of a costly population.Footnote 26 The head of the Judiciary, Ayatollah Sadeq Ardeshir Amoli Larijani, leading member of the conservative faction and brother to the Parliament speaker Ali Larijani, echoed these results, asking for a swift re-settling of ‘addicted prisoners’ in the compulsory camps for the sake of treatment. Compulsory camps, rather than being under the supervision of the Prison Organisation, are managed by the DCHQ.Footnote 27

Out of the conviction that the drug (ab)user population would be relegated to the camps, the Ahmadinejad government suspended the needle exchange programmes in prisons, affirming that ‘the situation [of HIV/AIDS] was under control’.Footnote 28 The assumption among officials became that since drug (ab)users are now referred to compulsory camps, needle exchange has become irrelevant in prisons. At the same time, the government proceeded towards a significant expansion of methadone treatment, bringing more than 40,000 prisoners under treatment by 2014. Methadone, in this regard, represented an acceptable solution, as it was produced domestically, it was readily available through private and public clinics and, last but not least, facilitated greatly – by virtue of its pharmacological effects – the management of unruly subjects, such as drug users, in the problematic contexts of prisons.Footnote 29 In the account of several former drug offenders in prison, the authorities tended to encourage methadone treatment with high doses, without much scrutiny of either the side effects of excessive methadone use, or the internal economy of methadone within the prison.Footnote 30

Inspired by the relative success of its methadone programmes (in prisons, as much as outside), the DCHQ agreed to pilot methadone treatment programmes inside some of the compulsory treatment camps supervised by the NAJA. This, it seems, was identified as a productive way to introduce the highest number of drug addicts into the cycle of treatment, via less harmful drugs such as methadone. By familiarising arrested drug (ab)users to methadone, the authorities sought to maintain them off, allegedly more dangerous drugs, such as heroin. But because the number of methamphetamine users had increased significantly, methadone proved ineffective, and the authorities sought alternatives in the model of the compulsory camps. Based on forced detoxification, these camps treated all drug (ab)use without distinction. Shafaq camp embodied the new model of treatment of drug (ab)use.

In 2010, the government inaugurated the mandatory treatment camp of Shafaq in the village of Shurabad, south of Tehran. The location of this centre sounded familiar to those acquainted with Iran’s history of drugs: during the 1980s, Shurabad had been one of the major collective rehabilitation centres for drug (ab)users, one that was often given focus in media reports. In the 1990s, it was transformed into a female prison, before eventually being abandoned. Its revivification synchronised well with the post-reformist government’s call to bring back the revolutionary principles of the Islamic Revolution, in the spirit of Sadegh Khalkhali and his onslaught against drugs. However, the Shafaq centre did not resemble the old, obsolete structure of the 1980s. It was rebuilt with the objective of instituting a model for other compulsory camps as well as for other non-state rehab camps.

The target population of this camp consisted of marginal drug (ab)users, a fluid category made of poor or pauperised homeless or with instable housing, people visiting or living around the patoqs in Tehran. Shafaq’s management was initially entrusted to retired Colonel Khalil Hariri, a leading commander of Anti-Narcotic Police who had been stationed in the Sistan and Baluchistan region for nine years with the primary duty of fighting drug traffickers.Footnote 31 His appointment revealed the government’s priorities on treatment: a top security official in anti-narcotics acting as director of an addiction treatment centre. In Shafaq, the government allocated ca. 100,000 tuman (ca. USD 8) per treated addict, which officials said would cover the employment of medical and social cadres to supervise recovery, which they expected to last for a three-month period.Footnote 32

The camp of Shafaq operated from early 2010 to late 2012, when a huge scandal broke out bringing its closure. Fifty-three people, rounded up by the police because of their status as ‘public addicts’, had died of chronic dysentery after having spent a few weeks in the camp. Media reported the deaths and several journalists managed to contact people who had previously been inside the camp, unearthing dramatic accounts. The picture that emerged from the reports was gruesome: a single silo with no windows, composed of fourteen rooms on two lines, each occupying fifty beds, with no heating system installed, inadequate sanitary services and insufficient alimentary provisions, the centre soon became the symbol of the state’s inhumane treatment of drug (ab)users.Footnote 33

Overcrowded rooms and the lack of medical personnel added to the ordinary accounts of beatings, mistreatment and abuse by the personnel, including physical violence against elderly individuals.Footnote 34 The use of cages, bars and handcuffs, constant police surveillance, disciplining rules and physical violence exposed, on the one hand, the contrast with the humanitarian and medicalised precepts of harm reduction (Article 15) and, on the other hand, embodied a coercive and securitising strategy based on the management of the margins, perceived as disorderly and chaotic. Dozens of people I encountered in the drug-using hotspots – the patoq – mentioned their experience, or that of their cohorts, in the camp, remarking, not without some pride, the fact they were still alive despite what they had gone through.Footnote 35 Whether their accounts were effectively experienced or empathically imagined, scarcely mattered. In fact, the narratives of Shafaq established a shocking precedent among the population of homeless, pauperised drug (ab)users, which delegitimised governmental interventions on the problematique of addiction, while unwrapping the inconsistencies behind the state’s framing of ‘addiction’ as a medical problem.

Even the work of harm reduction organisations, which had stepped up in supporting the needs of homeless drug users, was negatively affected by the public outcry against Shafaq. Social workers operating in the patoqs had to reassure the drug-user community of their non-involvement in ‘compulsory camps’. In several patoqs, the outreach programmes had to be stopped because of the threat of violence by the patoq’s thugs [gardan-koloft, literally ‘thick-necks’], who feared that strategic information was gathered by the NGOs and sent to the police (an allegation that had some factual evidence, in fact). One man from the Farahzad Chehel pelleh (literally ‘40-steps’) patoq explained me that ‘Shafaq is a place that even the bottom line people [tah-e khatti-ha] cannot bear! And these guys [indicating the outreach team], we don’t trust them, one day they give us syringes, the other day they stare at us when the police comes and brings us to hell!’ Anathema of the homeless drug-using community in Tehran, a young interlocutor of mine would use the metaphor of barzakh to describe Shafaq: the Islamic purgatory, or limbo, whereby one could spend the eternity before the judgement at the end of times.Footnote 36 Intellectually, this image connected with the theological, eschatological meaning of ‘crisis’ as the moment of the ultimate judgment, the moment that decisions take shape regardless of established conventions.

Beside Shafaq, the compulsory treatment camps became sites of risk themselves, with the spread of HIV and other venereal diseases being reported on a number of occasions. For instance, Majid Rezazadeh, the Welfare Organisation’s head of prevention, recounted that ‘a budget for harm reduction is allocated to the compulsory camps, but these [camps] are not only unsuccessful in decreasing the rate of addiction, but they have become actual locations for the spread of the virus of AIDS in the country’.Footnote 37 Indeed, the debate about the status of these camps proceeded up to the post-Ahmadinejad period. One of the conference presenters mentioned earlier in this chapter, Ahmad Hajebi, invited the DCHQ, to pledge publicly to the definitive closure of the compulsory treatment camps, because ‘they are not places for human beings’.Footnote 38

Nonetheless, compulsory camps have been part of the political economy of addiction in the Islamic Republic: the police identified this model as an easy source of governmental funds, based on a regulation that ensured state bonuses to the NAJA for every drug offender referred to state-run camps. By collecting homeless drug users from across the cities’ hotspots on a regular basis, the police benefit from a substantial financial flow, justified by the expenses that it putatively incurs managing the camps. Given that most of the state-run camps are known for their Spartan and down-to-earth conditions, it is implied that considerable amounts of money are filling the coffers of the NAJA through addiction recovery subsidies. This also implies that the NAJA has a stake in the continuation and proliferation of the activities of the compulsory camps.Footnote 39 Although incidental to the case of compulsory camps, the rumours and accusations about the expensive cars and unchecked revenues of police officials might be a collateral effect of the compulsory camp model.Footnote 40 According to a member of the DCHQ, the municipality of Tehran spends around 400 million tuman per month on taking care of the city’s addicts, or rather for the provision of services to them.Footnote 41 Thus, the police becomes the ultimate powerbroker in drug (ab)use, especially when higher numbers of arrests contribute to a boost in budgetary allocation.

The existence of the compulsory camp model testifies to the endurance of a securitisation approach, based on law enforcement techniques, which coexists with a medicalised and managerial approach to drug (ab)use.Footnote 42 But the camps, paradigmatically, embody a new mode of law enforcement – one that, instead of contesting harm reduction, uses its rhetoric for a new purpose. Security rather than humanitarian concerns govern this model foregrounded in a management of disorderly population – one could name them the ‘downtrodden’ to use Iran’s revolutionary lexicology – through coercive mechanisms, while leaving drug (ab)users, from middle class backgrounds, unmolested.Footnote 43 While reports about Shafaq in the newspapers prompted a political reaction, bringing about the closure of the camp (and its reopening under a new management in 2014), other centres have continued to operate with similar modalities, even though with less outrageous conditions. In 2014, the director of Rebirth provocatively asked the authorities, ‘to take the addicts to prisons’ instead of the treatment camps, because at least as a prisoner the addict would have minimal support from medical and social workers.Footnote 44

Private Recovery Camps

Private rehabilitation centres have been operating legally or informally since the mid 1980s, although their veritably extra-ordinary expansion can be traced back to the early 2000s and the new politico-medical atmosphere brought in by the reformists. In particular, the coming of age of the NGO Rebirth laid the ground for a mushrooming of charitable, private rehab centres, popularly known as camps. The word camp in Persian, rather than recalling the heinous reference to the Nazi concentration camps, hints at the camp-e tabestani, ‘summer camps’, ‘holiday camps’ that had become very much à la mode among middle-class Iranians in the 1990s.Footnote 45