A long tradition of studies on mass participation, especially in the United States, has examined the critical importance of race as a determinant of political engagement and participation (for instance, Matthews and Prothro, Reference Matthews and Prothro1966; Olsen, Reference Olsen1970; Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Shingles, Reference Shingles1981; Guterbock and London, Reference Guterbock and London1983; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman, Brady and Nie1993; Tate, Reference Tate1994; Leighley and Vedlitz, Reference Leighley and Vedlitz1999; Hutchings and Valentino, Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004; Chong and Rogers, Reference Chong and Rogers2005; McClerking and McDaniel, Reference McClerking and McDaniel2005; Fraga, Reference Fraga2018 among many others). Race is a socioeconomic cleavage that has political implications in other contemporary societies as well (e.g., Marx, Reference Marx1998; Winant, Reference Winant2001; Bleich, Reference Bleich2003; Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2008; Loveman, Reference Loveman2014; Mitchell-Walthour, Reference Mitchell-Walthour2018), but we know less about its role as a predictor of political participation from a comparative standpoint.

This paper contributes to the comparative study of race and political behavior by examining group differences in political participation in three racialized societies that experienced different racial formation processes (Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994; Winant, Reference Winant2000) that resulted in differences in the politicization of racial identities—Brazil, South Africa, and the United States. I argue that the role of race as a driving force of political mobilization is conditional on the existence of politicized racial identities. The sheer existence of racial inequalities and discrimination is not sufficient to foster different levels of political involvement based solely on membership of (or identification with) particular racial groups. Race as a political force is, therefore, the outcome of racial projects that emphasize race as a political cleavage.

I argue that, where race is legally constructed and mobilized as the basis of discriminatory practices and policies, as was the case in apartheid-era South Africa and the Jim Crow period in the American South (Woodward, Reference Woodward1955; Louw, Reference Louw2004), mechanisms for defining “crisp” race group boundaries—and, consequently, group membership—enable the enforcement of discrimination against target groups. By helping to establish and enforce the criteria for group membership, those same mechanisms unintentionally lay the foundations for the development of group identity and consciousness along racial lines, which may mobilize members of (formerly) discriminated groups to engage in political resistance (Marx, Reference Marx1998). These cleavages and racial identities reinforce each other both as a function of, and reaction to, state power. They become institutionalized and develop long-lasting effects that may persist after the legal discrimination ends (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio, Powell, DiMaggio and Powell1991). The emergence and consolidation of such political identities is, therefore, especially important for political organization and mobilization to participate in activities that demand higher levels of collective organization, such as direct action in protests and boycotts. As these forms of direct action are repeatedly performed by group members, they are eventually incorporated into their repertoire of political action via socialization and practice (Barnes and Kaase, Reference Barnes and Kaase1979). If group boundaries remain “porous” or ill-defined, as they are in Brazil, group membership becomes ambiguous, weakening the group identity formation process—thus making mass political participation along group lines less likely (Marx, Reference Marx1998).

I analyze data on non-electoral political participation from cross-national surveys carried out in the mid-2000s in Brazil, South Africa, and the United States to examine this hypothesis. I also address an important gap in the political participation literature in Brazil and South Africa by exploring political activism and participation in voluntary political and non-political organizations. Analyzing non-political organizations is relevant here for examining whether the mobilization of identities would also affect behavior outside the political realm. The analyses examine group-level differences in participation across race groups and whether such participatory asymmetries, if any, can be attributed to socioeconomic factors or to political attitudes. The findings show that Blacks in the United States and Blacks and Coloureds in South Africa are more likely to participate in political acts that require intense grassroots mobilization such as demonstrations, whereas Whites in those countries are overall more active in resource-demanding forms of activism such as signing petitions and financial contributions to political causes. Participation in voluntary organizations is complex, and the contextual role of religious association is remarkable. Although Black Americans report higher engagement with churches, which is consistent with the historical role of Black churches in the United States as a locus for political mobilization, Blacks in South Africa are less engaged in religious associations than Whites and Coloureds, which might reflect the role of specific denominations such as the Dutch Reformed Church in providing theological support for apartheid. Regarding other types of associations, there is little difference between Blacks and Whites in the United States and Coloureds and Whites in South Africa; overall, Black South Africans are less engaged in associations, and socioeconomic resources explain part of this participatory gap. Brazil does not display substantive group differences in activism or associational life between Blacks, Browns, and Whites for either mobilization- and resource-demanding activities or membership in organizations.Footnote 1

Voting behavior is not addressed in this paper. Differences in electoral systems—for instance, voting is compulsory for adults in Brazil and optional in South Africa and the United States—exert institutional constraints on the structure of incentives for turnout (e.g., Cox, Reference Cox1997), which is beyond the scope of this study.

The next section discusses the construction of race as a politically salient identity in Brazil, South Africa, and the United States to provide a theoretical background for assessing the expected differences (or lack thereof) in participation between groups in each country. I then selectively review the prior research on racial differences in political participation in the three countries, and discuss the concept of political participation and the empirical strategy for measuring political (and non-political) participation. Thereafter, I present the hypotheses and expectations derived from the current literature, followed by the data and methods deployed in the empirical analysis. The results are then presented and discussed. The paper concludes by assessing the implications of the findings for future scholarship.

Racial projects and social identities

An influential literature on race and politics, largely focused on the United States, has argued that group consciousness and linked fate (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Dawson, Reference Dawson1994) are important drivers of political participation for political minorities since they foster a strong sense of group attachment and a need for collective action to pursue social change that eventually offset socioeconomic resources as explanatory factors of political behavior. As claimed by Verba and Nie (Reference Verba and Nie1972, 151), “group consciousness may substitute for higher social status that impels citizens into political participation.” To extend this logic to the analysis of race and political participation in South Africa and Brazil, I build a broader argument based on Social Identity Theory to examine the conditions under which race is an important predictor of political attitudes and behavior.

According to Social Identity Theory, individuals aim to be members of groups that provide them with some positive utility such as prestige, power, or self-esteem. If membership of a certain group provides no such rewards, individuals will leave the group if possible and aspire to join other groups (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981). If it is not possible to leave the group, member will either seek to reshape the meaning of group membership (Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2008; Camp, Reference Camp2015) or engage in collective strategies of social change (McAdam, Reference McAdam1982) to alter group hierarchies to make it a more positive and rewarding affiliation (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1975, Reference Tajfel1981).

Importantly, the feasibility of changing one's group affiliation might not only be a function of individual will. It is also conditional on the structural features that define group membership: the permeability of group boundaries is crucially important (Ellemers, Reference Ellemers1993). If groups in a given society are constructed as discrete entities with “bright” and impermeable boundaries (Alba, Reference Alba2005), boundary crossing will be unlikely, and collective action to pressure for changes in the group hierarchies becomes a last resort against the stigmatization of group membership (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1975; Ellemers, Reference Ellemers1993).

The three countries examined here differ considerably in their historical enforcement or race boundaries. Cross-national variation in how race has been socially constructed accounts for differences in the permeability of group boundaries across societies and, consequently, for the political salience of race (Omi and Winant, Reference Omi and Winant1994; Wimmer, Reference Wimmer2008; Telles and Sue, Reference Telles and Sue2009).

Marx (Reference Marx1998) argues that the differences in nation-building processes in the case study countries have attenuated or emphasized the salience of race as a response to their elites' need for political survival and to warrant national territorial integrity. In South Africa and the United States, the development of an intra-White coalition and the strengthening of an overarching White identity to appease separatist forces—from the Afrikaner nationalists and the Southern confederates, respectively—in the aftermath of bloody civil wars in the second half of the nineteenth century occurred at the expense of racial minorities. This led to the disenfranchisement of non-White populations and the eventual institutionalization of legal discrimination systems and the use of the state apparatus to enforce group boundaries as a means of implementing segregationist policies (Marx, Reference Marx1998). This section outlines the key events in Brazil, South Africa, and the United States that helped shape their race relations and racial projects. See, among others, Freyre (Reference Freyre1946 [1933]); Woodward (Reference Woodward1955); Fredrickson (Reference Fredrickson1981); Davis (Reference Davis1991); Ribeiro (Reference Ribeiro1995); Marx (Reference Marx1998); Nobles (Reference Nobles2000); Thompson (Reference Thompson2000); Beinart (Reference Beinart2001); and Winant (Reference Winant2001) for detailed historical overviews and interpretations of the development of race relations in those societies.

In the antebellum United States, slavery was an established institution in the South, and anti-Black laws restricting the social and political rights of free Blacks in both Southern and Northern states were almost universal. Such laws generally included the segregation of public spaces, anti-miscegenation, and the denial of voting rights. The Thirteenth amendment abolished slavery in the United States after the Civil War, but several Southern states passed legislation in 1865–66, known as the Black Codes, that restricted the rights of free Blacks, generally including the segregation of public facilities and institutions, economic rights, and anti-miscegenation laws (Forte, Reference Forte1998). Despite the Fifteenth amendment's prohibition of the denial of the right to vote based on race, Black voting was suppressed via legal restrictions on voter registration and threats of physical violence. The end of the federal government's Reconstruction-era protection of Blacks' political rights in 1877 placated Southern objections to national unity, and the ruling of the constitutionality of segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 paved the way for the institutionalization of Jim Crow laws in the South (Woodward, Reference Woodward1955; McAdam, Reference McAdam1982). Although anti-Black practices were generally less severe in Northern states, de facto segregated real estate developments, schools, sports facilities, restaurants, churches, and other public spaces were also pervasive outside the South (Marx, Reference Marx1998; Sugrue, Reference Sugrue2008, Reference Sugrue2012). After Brown v. Board of Education mandated school desegregation when Plessy v. Ferguson was overturned in 1954 and with the direct action of Black activists, legal segregation in the United States ended with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Group identities and political attitudes have largely developed along racial lines; these have been reinforced by the persistence of prejudice and informal discriminatory practices (Kinder and Sanders, Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Marx Reference Marx1998; Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Chai and Yancey2001).

Similarly, South Africa engaged in race-based exclusion throughout most of the twentieth century that is rooted in its colonial experience. In contrast to Brazil and the United States, the Black populations of which were transplanted to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade, South African Blacks comprise a myriad of groups native to that continent. The initial relationship in the mid-seventeenth century between the native Khoikhoi and the Dutch merchants, who aimed to establish a trading post in the Cape area to provide support for the vessels of the Dutch East India Company en route to India and Southeast Asia, were amicable (Crijns, Reference Crijns1959; Thompson, Reference Thompson2000). In the settlements, slaves imported primarily from India and Southeast Asia provided labor, and played an important role in the founding of the Coloured group in South Africa (Jeffreys, Reference Jeffreys1953).

As the Dutch settlements became permanent and expanded into arable land, leading to territorial disputes, and the Khoikhoi's became more willing to hide runaway slaves, tensions between natives and Europeans soon developed. The constant skirmishes at the colony's expanding frontier and the emerging sense of racial superiority among the Afrikaner “Boer” is believed to have laid the foundations of the White colonialists' harsh racial attitudes toward the indigenous Black population and non-Whites in general (Crijns, Reference Crijns1959; MacCrone, Reference MacCrone1961). Animosities between the Afrikaners and the British started as early as 1795 following the British takeover of the Cape Colony and escalated with the abolition of slavery in 1834, which became a focal point of tensions between the groups.

The British administration assessed that Afrikaner nationalism could pose a threat to stable rule in Southern Africa, as it later did in the 1899–1902 Second Boer War, and promoted peaceful accommodation and concessions to appease the Afrikaners. For instance, when the British government provided the Cape Colony with a local government and a constitution to legislate domestic affairs in 1853, even though the principle of non-racialism was incorporated into the text, franchise requirements were such that non-Whites were excluded from elections in practice and treated as a distinct, inferior community. In subsequent years, pressures from race-conscious Afrikaners to introduce racial segregation led to the creation of a separate congregation of the Dutch Reformed Church for non-Whites in 1857 and the banning of non-White children from public schools in 1861 (Ritner, Reference Ritner1967; Thompson, Reference Thompson2000). In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, with the expansion of the mining sector, discrimination in the workplace gained momentum: explicit provisions were introduced to reserve skilled jobs for Europeans and manual labor for Black workers only (Feinstein, Reference Feinstein2005). Discussions about prohibiting Black natives from acquiring land started as early as 1903 and culminated in the 1913 Natives Land Act, one of the first major laws passed in the Union of South Africa, which created “native reserve areas” comprising 7% of the country's territory (expanded to 11% in 1939) and prohibited Blacks from purchasing or leasing land outside the reserves (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg1993). The alliance between Afrikaners and English speakers against the cultural and demographic “Black threat” reached its pinnacle with the introduction of apartheid after the victory of the Afrikaner ethnic nationalist National Party in the 1948 general election (Marx, Reference Marx1998). Apartheid consolidated existing and novel exclusionary policies against native Black and Coloured populations into a broad segregation system that enforced racial classification, banned intergroup marriage, and regulated land use and employment, in addition to other realms of life (Crankshaw, Reference Crankshaw1997; Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Posel, Reference Posel2001). The system was dismantled in the early 1990s during transitional period that resulted in a general election with universal suffrage in 1994, followed by the repeal of apartheid legislation. After almost a half-century of legal segregation and political mobilization along group boundaries, race remains socially and politically salient in post-apartheid South Africa (Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Amoateng and Heaton2004; Seekings, Reference Seekings2008; Muyeba and Seekings, Reference Muyeba and Seekings2011).

The development of race relations followed a different path in Brazil. Portuguese colonial rule had been largely unchallenged since the mid-seventeenth century, and the relocation of the Portuguese court to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 consolidated the central government's power. Numerous slave rebellions and regional separatist movements were contained and defeated (Bethell and Carvalho, Reference Bethell, Carvalho and Bethell1985). Slavery was prevalent nationwide, as it was a fundamental institution of Brazilian society; elites' overall consensus about slavery led to few or no incentives to develop racial ideologies to create an overarching White identity to unify regional elites (Marx, Reference Marx1998). In response to the growth of the abolitionist movement and the thriving slaves' resistance throughout the nineteenth century, the central government took legislative action to (slowly) transition toward abolishing of slavery (Reis and Klein, Reference Reis, Klein and Moya2011). Amid a large non-White population and mindful of past slaves' revolts, Brazilian elites aimed to minimize potential conflict along racial lines, and no system of legal segregation has been enforced since the abolition of slavery in 1888, although darker-skinned individuals do still experience informal forms of prejudice and discrimination (Marx, Reference Marx1998; Telles, Reference Telles2004). During the first half of the twentieth century, race mixing was promoted as the very definition of “Brazilianness” (Skidmore, Reference Skidmore1993 [1974]), with the development of a race classification system characterized by high levels of ambiguity and flexibility in the popular discourse and practice (Harris, Reference Harris1970; Telles, Reference Telles2004).

Building on this discussion, I contend that the salience of race for political mobilization is conditional on how race is constructed and experienced in a society. The state plays a critical role in imposing racial terminology and enforcing racial boundaries—i.e., in determining the permeability of group boundaries—which unintentionally legitimates group identities and solidarities, and encourages group-based mobilization. Racial identities are, therefore, the product of state power as well as reactions to it (Marx, Reference Marx1998). As these identities are reinforced, they become institutionalized and develop long-lasting effects (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio, Powell, DiMaggio and Powell1991) that persist after legal discrimination is overruled. Importantly, the presence of racial inequalities is not sufficient for the politicization of race. Social Identity Theory predicts that an identity will be politicized if, in addition to group stigmatization, group boundaries are impermeable and prevent individuals from moving between groups. As the result of their racial formation processes and enforcement of group boundaries, race is expected to be an important political force with the potential to counterbalance the lack of other determinants of political participation in societies such as South Africa and the United States. Such a “race effect” should be absent in Brazil according to the theory.

Race and participation

An influential approach in the study of political participation emphasizes the importance of resources for electoral and non-electoral forms of political participation. According to this approach, a larger endowment of resources, either material or cognitive, increases the probability of political involvement, engagement, and participation (Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1965; Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Wolfinger and Rosenstone, Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Leighley, Reference Leighley1995; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995). In other words, individuals with higher socioeconomic status (SES), political information, political interest, and connections to recruitment networks tend to be more politically active. If political participation is conceived as a form of input to the political system (Easton, Reference Easton1957), then severe inequalities in politically relevant resources are expected to lead to biased outputs from the system in favor of individuals and groups that are more capable of exerting pressure on the system (Dahl, Reference Dahl1996; Gilens, Reference Gilens2005). The resource-based model of political participation has been widely employed to explore the links between race and political participation in the United States. Scholars in this research tradition have argued that racial minorities have overall lower levels of participation in most political activities—including voting, contacting politicians, and membership in political groups—as a consequence of their less plentiful stocks of resources. Blacks and Latinos have been found to participate less than Whites in the United States because they have less access to politically relevant resources, but group differences in participation vanish after accounting for the effect of resources (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman, Brady and Nie1993, Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Leighley and Vedlitz, Reference Leighley and Vedlitz1999). According to this approach, race and ethnicity affect political participation through their strong influence on the acquisition or development of resources.

Recent scholarship on political participation has nevertheless challenged the tenets of the resources-based approach. Cross-national evidence suggests that the impact of resources on political participation might be circumstantial, conditional on context, or restricted to specific groups or modes of participation (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005; Booth and Seligson, Reference Booth, Seligson and Anirudh2008; Krishna, Reference Krishna and K2008; Mattes, Reference Mattes2008; Pateman, Reference Pateman2012; Isaksson, Reference Isaksson2014). It has also been demonstrated that perceptions of the influence of various sociodemographic groups over political outcomes—e.g., the group's relative contribution to the electoral results—have an important impact on decisions about whether to participate in politics beyond what is predicted based on the level of available resources (Fraga, Reference Fraga2018; see also Howell and Fagan, Reference Howell and Fagan1988; Bobo and Gilliam, Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990).

Another perspective on political participation, also primarily developed in the American context, proposes that group-level factors such as group identity and group consciousness play a significant role in explaining the political participation of different race groups, especially minorities. Several studies have demonstrated that group consciousness can also be an important resource leading to political participation; the resource model pays little attention to such group-specific factors (Matthews and Prothro, Reference Matthews and Prothro1966; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Shingles, Reference Shingles1981; Bobo and Gilliam, Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Chong and Rogers, Reference Chong and Rogers2005; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Eugene and Watts2009; Masuoka and Junn, Reference Masuoka and Junn2013). Group consciousness embodies a notion of shared interests between the individual and the group that might facilitate collective action when coupled with perceptions of illegitimate intergroup differences in status (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1975; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Dawson, Reference Dawson1994; Huddy, Reference Huddy, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013).Footnote 2 Studies conducted during or in the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement in the United States claimed that, after controlling for the effect of resources, Blacks would be equally and eventually more politically active than Whites, and that a sense of group identification and group consciousness have a significant influence on a range of political activities such as protests and community activities (e.g., Orum, Reference Orum1966; Olsen, Reference Olsen1970; Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Shingles, Reference Shingles1981). Recent research has also highlighted the importance of group consciousness in explaining the political behavior of racial minorities in the United States (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Lien and Margaret Conway2005; Sanchez, Reference Sanchez2006; Masuoka and Junn, Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Foster and Combs2019).

In sharp contrast to the rich tradition of research on race and political participation in the United States, few studies have examined the issues in other societies, including Brazil or South Africa. Prior studies have argued that race is not an effective dimension for forging a sense of group identity or group consciousness in Brazil. Factors usually identified as part of an Afro-descendant identity in the United States, such as religion and skin color, or structural factors including residential segregation, are not exclusive to Afro-descendants in Brazil and are thus not effective forces for group mobilization (Telles, Reference Telles1996). Most of the scarce survey-based literature on race and political behavior in Brazil has focused on voting. Although this research has pointed out that even though race identification might lead to differential vote choice in the country despite the absence of a strong racial consciousness among non-Whites in Brazil (Souza, Reference Souza1971; Soares and Valle Silva, Reference Soares and Valle Silva1985, Reference Soares and Valle Silva1987; Castro, Reference Castro1993; de Souza Carreirão, Reference Carreirão2007; Bailey, Reference Bailey2009; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2009; Peixoto and Rennó, Reference Peixoto and Rennó2011), its effect would not be a major determinant of voting behavior (Prandi, Reference Prandi1996; Rennó, Reference Rennó2007). Recent research on non-electoral political participation has also suggested that the major cause of unequal levels of participation between Whites and non-Whites is group differences in resource levels, since the effect of race on participation dissipates after controlling for resources (Bueno and Fialho, Reference Bueno and Fialho2009; Bueno, Reference Bueno2012).

Perhaps, even more surprising is the contrast between the relative scarcity of quantitative research on race and non-electoral political participation in South Africa compared to the abundance of studies on social and political attitudes (e.g., MacCrone, Reference MacCrone1937; Pettigrew, Reference Pettigrew1960; Van den Berghe, Reference Van den Berghe1962; Foster and Nel, Reference Foster, Nel, Foster and Louw-Potgieter1991; Gibson, Reference Gibson2006; Seekings, Reference Seekings2008; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Kivilu and Davids2010), social movements (e.g., Seekings, Reference Seekings2000; Piombo, Reference Piombo2005; Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Habib and Valodia2006), and voting behavior (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart and Rose1980; Ferree, Reference Ferree2006; De Kadt, Reference De Kadt2017). Even though research on party preference and voting choice is marked by strong racial divides (Ferree, Reference Ferree2006; De Kadt, Reference De Kadt2017), studies on political activism have often only presented aggregate figures; between-group comparisons have not been forthcoming (e.g., Mattes, Reference Mattes2002; Davids, Reference Davids, Roberts, Kivilu and Davids2010). It has, nevertheless, been shown that Black South Africans are more active in community participation and in joining demonstrations than Whites and, to a certain extent, Coloureds (Klandermans et al., Reference Klandermans, Roefs and Olivier2001; Kotzé, Reference Kotzé2001; Mattes, Reference Mattes2008; Lavery, Reference Lavery2012). However, a more systematic look at non-electoral political participation in South Africa has not been undertaken. Some comparative analysis of Brazil and South Africa has suggested that race has opposite effects on participation in two countries. In Brazil, race loses its impact on political participation after controlling for resources, whereas in South Africa, resources lose their effect on participation after controlling for race (Reis et al., Reference Reis, Fialho, Bueno and Candian2007). These preliminary findings suggest that racial identity remains a major driving force behind political participation in the post-apartheid South Africa, and the lack of strong racial identities in Brazil is responsible for the non-effect of race.

Measuring political participation

Political participation is a fundamental research topic in the social sciences, but its very definition is not always straightforward. For example, at the conceptual level, what is the difference between a political versus a nonpolitical act? Political scientists' definitions of political participation often refer, implicitly or explicitly, to the electoral process or to state action. Verba and Nie (Reference Verba and Nie1972, 2), for instance, argued that political participation “refers to those activities by private citizens that are more or less directly aimed at influencing the selection of governmental personnel and/or the actions they take” (see, among others, Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1965; Huntington and Nelson, Reference Huntington and Nelson1976 for similar definitions). This perspective has influenced a large array of studies on political participation (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007).

Notwithstanding the undeniable importance of the state in modern societies, the focus on state actions elections may be too restrictive to accommodate contemporary forms of public action such as boycotting and other forms of political consumerism (Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Hooghe and Micheletti2005). This narrow concentration is also insufficient to account for the political activities of groups with no (or limited) political rights, such as non-Whites under apartheid and African Americans in the Jim Crow era in the U.S. South. Some scholars have criticized this electoral- and state-centered definition of political participation. It has been argued that “the political” concerns conflicts and their regulation, which obviously includes (but is not limited to) the state (Warren, Reference Warren1999; Reis Reference Reis2000). Moreover, political participation attempts to influence the allocation of social goods and values, which includes the distribution of political power through strategic positions in state institutions, but might also refer to goods outside the scope of the state, where it might serve as a mediator at best (Rosenstone and Hansen, Reference Rosenstone and Mark Hansen1993; Warren, Reference Warren1999). This broader definition of political participation encompasses both voting-related acts such as campaigning and casting ballots as well as activities such as petitioning, participating in demonstrations, and boycotts. Such acts aim to influence the distribution of goods and values (including political power) and include the state as one potential target of action.

Political participation is a multidimensional construct in which modes of participation are driven by different “logics,” causes, and intended consequences (Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1978; Claggett and Pollock, Reference Claggett and Pollock2006). Each mode of participation comprises a cluster of activities that usually go together: individuals performing one act in one cluster are likely to perform other acts from the same mode but not necessarily from another cluster (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1978; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007). Since prior research has found group-level differences in participation, and that some groups may be more active in specific types of participation than others, it is important to account for the variety of forms of political action in this analysis.

The original typology of modes of participation proposed by Verba and Nie (Reference Verba and Nie1972) in the American context, and later validated cross-nationally (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1978), encompassed four dimensions: (1) voting; (2) campaigning, which includes attending rallies, contributing money to a candidate, and persuading others how to vote; (3) communal activity, which accounts for acts related to solving local problems such as joining or forming a local group or contacting a local official about a social problem; and (4) personalized contacts such as reaching out to local, state, or national officials about a problem. Further research has extended Verba and Nie's findings and documented additional modes of participation such as political discussion (measured as the frequent engagement in political conversations) and cooperative-passive activity (such as belonging to organizations that aim to influence government and policy). These findings indicate that monetary contributions have recently become a separate, self-contained mode (Claggett and Pollock, Reference Claggett and Pollock2006).

Verba and Nie's and Claggett and Pollock's typologies cover only “conventional” forms of participation, which might be attributed to the original model's development circumstances. Nevertheless, their dimensions—in either original or expanded version—do not accommodate forms of non-electoral participation such as protest activity or emerging forms of political consumerism (Barnes and Kaase, Reference Barnes and Kaase1979; Norris, Reference Norris2002; Stolle et al., Reference Stolle, Hooghe and Micheletti2005). Teorell et al.'s (Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007) typology of political participation modes includes engagement in non-electoral forms of participation. In addition to representational (i.e., taking part in or directly targeting the electoral process) modes of participation such as voting, party activity (which resembles Verba and Nie's “campaign activity”), and contacting politicians and officials, Teorell et al. (Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007) propose two forms of extra-representational political participation: consumer participation and protest activity. Consumer participation includes boycotts, “buycotts,” petitioning, and donating money for political purposes. This mode is described as using market mechanisms to send (sometimes anonymous and vague) political messages.Footnote 3 Protest activity includes taking part in demonstrations and illegal protest acts.

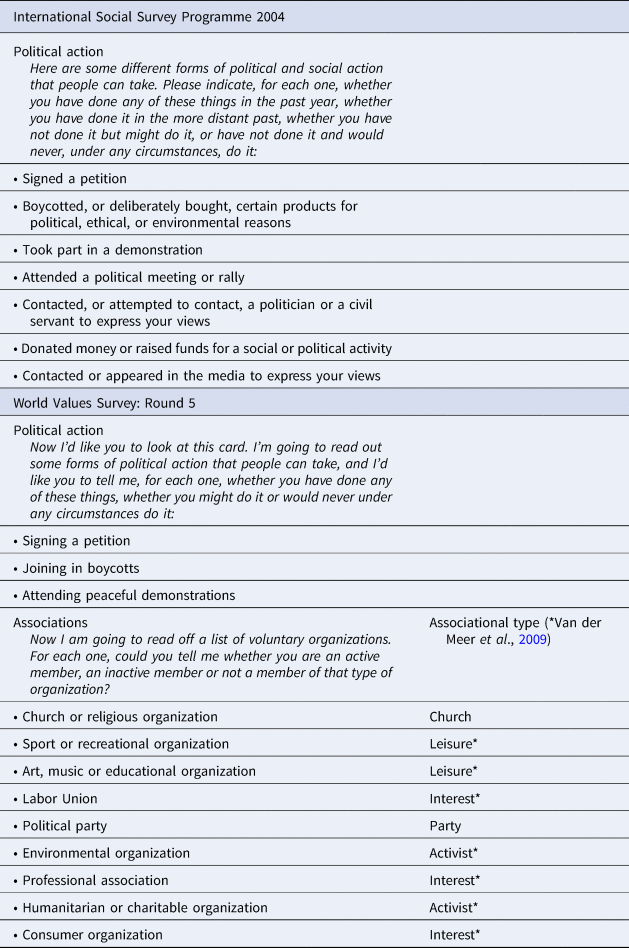

Table 1 lists the political acts for which data are available in the World Values Survey: Round 5 and the International Social Survey Programme 2004 (see the “Data and measures” section for further information). They include a selection of the modes of participation proposed by Verba and Nie (Reference Verba and Nie1972), Verba et al. (Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1978), Claggett and Pollock (Reference Claggett and Pollock2006), and Teorell et al. (Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, Van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007): political consumerism (signing petitions and participating in boycotts), donating money or raising funds for social or political causes (classified as either political consumerism or campaign/party activity and depending on the beneficiary), attending political rallies (campaign/party activity), contacting politicians and the media, and protest activity (e.g., participation in demonstrations).

Table 1. Survey items on participation in associations and political actions

Source: World Values Survey: Round 5 and International Social Survey Programme 2004.

A broader definition of the “political”—and, consequently, of political participation—also allows us to distinguish between membership in different types of voluntary organizations even though none of the modes of participation discussed above include participation in voluntary organizations. Van der Meer et al. (Reference Van der Meer, Grotenhuis and Scheepers2009) propose a typology comprising three types of voluntary organizations according to their primary concern or focus—activist, interest, and leisure organizations. Activist organizations, such as advocacy and lobbying groups, have the state as their primary focus of action; therefore, membership of this type of organization should be considered a form of political participation because it aims to influence the allocation of social goods. Activist organizations approximate Claggett and Pollock's cooperative-passive mode of participation. Interest groups focus primarily on market relations and can be either professional or consumer organizations. They encompass groups with political consumerism potential—therefore, related to politics—which would be excluded from conventional definitions of political participation (e.g., Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Huntington and Nelson, Reference Huntington and Nelson1976) but could serve as a proxy measure of Teorell, Torcal, and Montero's consumer participation. Leisure organizations fulfill recreational and socializing purposes, and thus fall short of being considered “political.”

I add two other types of organizations to Van der Meer et al.'s (Reference Van der Meer, Grotenhuis and Scheepers2009) typology—political parties and religious organizations. Parties are quintessentially political groups that seek to capture government positions to influence policy (Bawn et al., Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012). Parties carry out several political functions that might be related to different modes of participation, such as campaign activity and particularized contact. Religious organizations are technically non-political associations, given that their intended spiritual mission is not the regulation of conflicts or the allocation of goods and values in society, which makes it difficult to assign them to a mode of participation. However, such organizations have historically been an important locus for fostering a sense of belonging and group consciousness as well as networking and collective organization, such as the Black churches in the United States and the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (Ritner, Reference Ritner1967; McAdam, Reference McAdam1982; Lalloo, Reference Lalloo1998; McClerking and McDaniel, Reference McClerking and McDaniel2005). Moreover, active participation in religious organizations may also support the development of politically relevant skills (Rosenstone and Hansen, Reference Rosenstone and Mark Hansen1993; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995). Leisure organizations may also feature these organization, identity-building, and development functions (Erickson and Nosanchuk, Reference Erickson and Nosanchuk1990).

Although the subsequent analysis will assess political acts and membership in voluntary organizations separately rather than as clusters or dimension, the classification of political acts and organizations described above is relevant for comparing group-level political participation as it helps to map differences in the levels of participation across different types of political behavior. Including nonpolitical organizations, thus, also helps disentangle what might be specific about membership in different groups.

Hypotheses

The above discussion implies that race should be a strong predictor of political participation in societies where racial identities constitute a salient political cleavage. However, the literature on modes of participation suggests that different types of participation are influenced by different factors. Therefore, I hypothesize that race influences participation in specific activities—namely, those that demand mobilization along racial lines and form part of group's political repertoire. Therefore,

Hypothesis 1 (H1): In societies where race is a salient political cleavage, racial groups that have historically been discriminated against will be more engaged in political activities that demand mobilization and organization.

Therefore, I expected Blacks and Coloureds in South Africa and the United States to be more engaged in acts such as demonstrations, boycotts, and protests than Whites (McAdam, Reference McAdam1982; Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson1995; Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Sewell, Reference Sewell2004; Grant, Reference Grant2017).

Similarly, differences in participation in political acts that require mobilization along group boundaries in such societies would persist after controlling for conventional predictors of political behavior. Therefore,

Hypothesis 2 (H2): In contexts where race is a salient political cleavage, the effect of race as a predictor of participation in political activities that demand mobilization and organization remains even after controlling for relevant factors such as resources and attitudes.

The resistance of racial gaps in participation to controlling for other theoretically relevant predictors has been documented in the literature (e.g., Olsen, Reference Olsen1970; Booth and Seligson, Reference Booth, Seligson and Anirudh2008; Isaksson, Reference Isaksson2014; Fraga, Reference Fraga2018).

With regard to participation in voluntary organizations, Black churches in the United States have historically been an important locus of identity formation and political mobilization of Blacks (McAdam, Reference McAdam1982; McClerking and McDaniel, Reference McClerking and McDaniel2005; McDaniel, Reference McDaniel2008). Similarly, the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa served as an important site for the development of Afrikaner nationalism, and eventually also incorporated segments of the Coloured population (Lalloo, Reference Lalloo1998; Thompson, Reference Thompson2000). It follows that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Group differences in participation in institutional churches are expected in countries where religious affiliation is along racial lines. Blacks in the United States and Whites (and perhaps Coloureds) in South Africa are more engaged in institutional churches than their counterparts.

Elections in South Africa have been marked by voting along racial lines (Ferree, Reference Ferree2006). Similarly, Black Americans overwhelmingly vote in favor of the Democratic Party (Tate, Reference Tate1994). However, it does not follow that party membership differs between racial groups. Therefore, I do not advance a hypothesis on party membership.

The resource-based approach to political participation offers different predictions on group levels of participation, i.e., differences in political participation reflect differences in the stocks of politically relevant resources available to group members (Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1965; Verba and Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972; Wolfinger and Rosenstone, Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Leighley, Reference Leighley1995; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995). This approach generates two predictions:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a): Group differences in political participation are a function of the disparities in resources levels between race groups.

The effect of race on political participation is due to sociopolitical processes—such as discrimination—that influence the acquisition or development of resources. It follows that, on average, better-off groups will demonstrate higher overall levels of participation. Group differences in participation, however, should vanish once resource inequalities are accounted for (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman, Brady and Nie1993, Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Leighley and Vedlitz, Reference Leighley and Vedlitz1999).

Hypothesis 4b (H4b): Group differences in political participation are statistically non-significant after controlling for relevant resources.

Finally, as noted above, Brazil represents a distinct case in which important racial socioeconomic disparities are not matched by historically politicized racial boundaries (Marx, Reference Marx1998). Race is, therefore, not expected to play an important role as a predictor of political behavior.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Race is not a strong predictor of political behavior in Brazil.

Given the country's noticeable racial inequalities, according to the resource-based approach to political participation, average disparities in group-level resources should lead to group differences in political behavior that should be statistically non-significant after controlling for resources, in accordance with H4b.

These expectations do not exhaust all possible outcomes presented below. For example, I do not make predictions for signing petitions or participating in activist or leisure organizations. The study's major claim rests on the differential participation of historically discriminated groups in voluntary organizations that foster group identities and in political acts that demand mobilization and organization. I, therefore, assume that other types of political acts and voluntary organizations follow the predictions of the resource-based approach.

Data and measures

Data sets

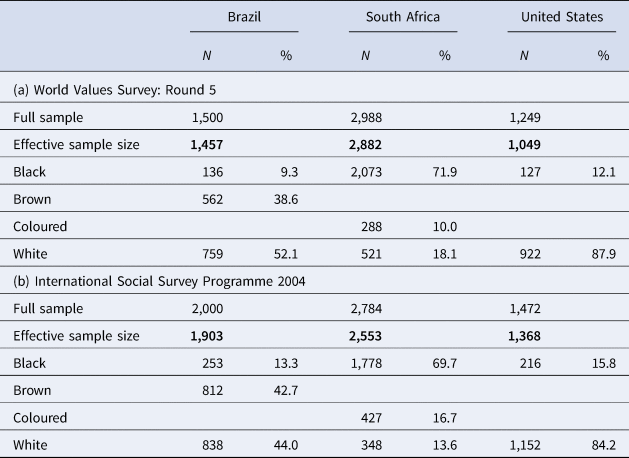

I employ data from two comparative social surveys in order to examine the role of race as a predictor of political participation in Brazil, South Africa, and the United States: The International Social Survey Programme 2004 (ISSP; ISSP Research Group, 2012) and the World Values Survey: Round 5 conducted in 2006 (WVS; Inglehart et al., 2014).Footnote 4 The ISSP and WVS collected data from nationally representative samples of adults (18+ years old in Brazil and the United States, 16+ in South Africa) using face-to-face interviews except for the American WVS, which used an online research panel. The ISSP and WVS core questionnaires were translated into the countries' national languages—Portuguese in Brazil; Afrikaans, Tswana, Xhosa, Zulu, and Venda (ISSP) as well as South Sotho and North Sotho (WVS) in South Africa—from the master questionnaire in English. The original English instrument was also used in South Africa and in the United States.Footnote 5 Sample sizes are reported in Table 2.Footnote 6 Measures of group identity and linked fate in cross-national surveys are scarce at best, and the WVS and ISSP are no exception. The available data do not allow the explicit assessment of within- and between-group variation in racial identity or how it correlates with political participation.

Table 2. Sample size and race groups

Note: “Full sample” indicates the total number of cases in the original data set for each country. “Effective sample size” indicates the cases retained for analysis. Percentages based on effective sample size.

Measures of political participation

Table 1 lists indicators of participation in political acts and voluntary associations. The ISSP and WVS political action items are recoded as binary variables based on whether the respondent has ever performed that action (either recently or in the more distant past) or not.Footnote 7 These measures of political actions have long been used to assess conventional participation (e.g., contact politicians) and protest potential (e.g., boycotting) in surveys (e.g., Barnes and Kaase, Reference Barnes and Kaase1979; Norris, Reference Norris2002; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010). WVS items on participation in voluntary organizations only allow respondents to report membership in certain types of organizations (e.g., humanitarian or charitable organizations); they cannot gage whether the respondent is a member of several organizations within the same category, which might artificially deflate the level of engagement in associations (Norris, Reference Norris2002, 147). Political parties are coded as an organizational type, and the remaining non-religious organizations are classified as one of the three types—leisure, interest, and activist—discussed in Van der Meer et al. (Reference Van der Meer, Grotenhuis and Scheepers2009). Churches and religious organizations constitute a separate associational type due to the multiple roles—including political (e.g., Rasool, Reference Rasool, Chidester, Tayob and Weisse2004; McClerking and McDaniel, Reference McClerking and McDaniel2005; Oro, Reference Oro2005)—they might perform in addition to their spiritual missions.

Race classification

All surveys use country-specific census categories. The data collection mode for racial classification differs across surveys. The ISSP employed self-classification in Brazil and the United States, whereas the interviewer assigned the respondent's race in South Africa based on observation. WVS respondents were classified by the interviewer in Brazil and South Africa, and the respondent's race was asked in a recruitment survey in the United States. Racial classification in the Brazilian ISSP and WVS questionnaires uses the five official categories used since the 1991 Census: Black (preto), Brown (pardo), Indigenous (indígena, native Brazilians), White (branco), and Yellow (amarelo, of Asian ancestry). The analysis focuses on the Black, Brown, and White categories, and excludes all other groups. According to the 2010 Brazilian Census, these three categories represented about 99% of the Brazilian population (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 2011).

The American ISSP questionnaire asks respondents to report her or his race (more than one category is allowed) as Black, White, or other.Footnote 8 Respondent's race in the American WVS was collected in a recruitment survey; respondents in the sample are classified as White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), other (non-Hispanic), and Hispanic. Only non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites are included in the analysis; they represented 85% of the American population according to the 2010 Census (United States Census Bureau, 2010).

In South Africa, both the ISSP and WVS collected information on race using the four official South African population categories (Black African, Coloured, Indian or Asian, and White). The analysis includes the Black, Coloured, and White groups only; according to the 2011 South African Census, these three groups represented 97% of the South African population (Statistics South Africa, 2012). Table 2 reports the number of observations for each group.

Control variables

Sociodemographics and political attitudes are taken into account as controls in binary logistic regressions that model the importance of race as a predictor of participation in organizations and political activities. Regression models using WVS data include education (9-point scale, from no formal education to complete college degree); gender (binary, male as the reference category); age (continuous variable) and age squared; interest in politics (4-point scale, from “not at all interested” to “very interested”); and opinion about the statement “civil rights protect people's liberty against oppression” as an essential characteristic of democracy (10-point scale, from “not essential” to “essential”).

Regression models using ISSP data include education (6-point scale, from no formal education to complete college degree); household income (natural logarithm transformation); gender (binary, male as the reference category); age (continuous variable) and age squared; interest in politics (4-point scale, from “not at all interested” to “very interested”); four measures of political efficacy (5-point scale, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), asking respondents their level of agreement with a statement on having no say about what the government does, that the government does not care about what citizens think, feeling a good understanding of important political issues in the country, and the belief that most people in the country are better informed about politics than the respondent; and four items on opinions about people's rights in a democracy (7-point scale, from “not at all important” to “very important”) such as government authorities should respect and protect the rights of minorities and treat everybody equally regardless of their position in society, that politicians should consider citizens' opinions before making decisions, and that citizens should have a chance to participate in decision-making.Footnote 9 As noted above, in addition to the importance of resources as predictors of political behavior (Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1965; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995), other factors such as group identity are influential as well (e.g., Olsen, Reference Olsen1970; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Shingles, Reference Shingles1981; Dawson, Reference Dawson1994; Chong and Rogers, Reference Chong and Rogers2005; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Eugene and Watts2009; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Foster and Combs2019); accounting for such factors would provide further information to help understand the mechanisms linking race and political participation. Unfortunately, none of the cross-national surveys analyzed here includes a set of measures of racial identity or linked fate, perhaps partly due to the potential challenges to develop questions on racial solidarity for groups other than African Americans (Chong and Rogers, Reference Chong and Rogers2005; but see Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Foster and Combs2019). Future cross-national surveys in multiracial societies would certainly benefit from developing comparative measures of group solidarity.

Missing data imputation

Prior to performing the data analysis, I used a Fully Conditional Specification (FCS) multiple imputation model using the Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) method in order to prevent the loss of data due to item nonresponse (Van Buuren, Reference Van Buuren2007, Reference Van Buuren2012). Prior studies have demonstrated that FCS outperforms other techniques for imputing categorical data, and that PMM preserves the distribution of the original data (Kropko et al., Reference Kropko, Goodrich, Gelman and Hill2014; Vink et al., Reference Vink, Frank, Pannekoek and Van Buuren2014). Multiple imputation is performed using the R package mice (Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011; R Core Team, 2021). Fifty “complete” data sets are generated from the multiple imputation.Footnote 10 A separate group imputation strategy (Enders and Gottschall, Reference Enders and Gottschall2011) is employed to preserve the multiple group data structure during the missing data imputation process. Therefore, missing data are imputed separately for each race group in a country. Estimates from the “complete” imputed data sets are pooled according to Rubin's (Reference Rubin1987) rules. Standard errors are calculated as follows: for each “complete” imputed data set, standard errors are obtained via nonparametric bootstrap with 1,000 replications; bootstrapped standard errors from each “complete” data set are then combined using Rubin's (Reference Rubin1987) adjustment for between-imputation variance. See Brand et al. (Reference Brand, Van Buuren, Le Cessie and Van den Hout2019) and Schomaker and Heumann (Reference Schomaker and Heumann2018) for a discussion of similar imputation-then-bootstrapping strategies.

Results

Group-level differences in political participation

Political activism

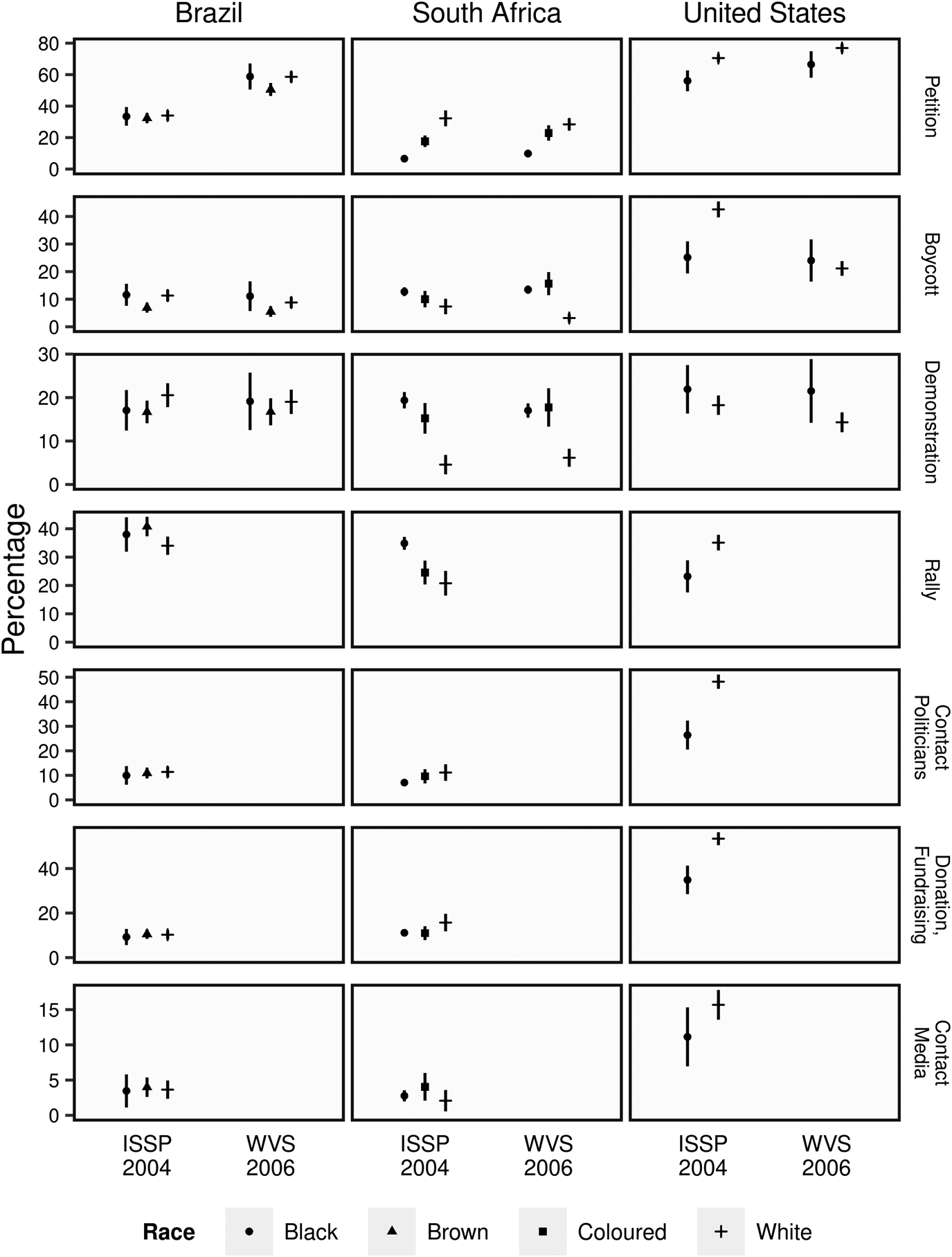

Figure 1 reports the frequency of participation in political acts for members of different racial groups across countries.Footnote 11 The ISSP and WVS results are similar for signing petitions, joining boycotts, and participating in demonstrations. A country's relative differences in participation between groups—i.e., the direction of the participation gap—are robust across surveys. White respondents are more prone to sign petitions in the United States and in South Africa, Blacks are more active in boycotting and demonstrations (followed by Coloureds and Whites) in South Africa, and there is a non-significant pro-Blacks difference in demonstrations in the United States. Group differences are small and non-significant in Brazil. The only remarkable discrepancy across surveys is registered for boycotting in the United States: Whites are more engaged in boycotts than Blacks in the ISSP data only.

Figure 1. Participation in political action.

Source: World Values Survey: Round 5 and International Social Survey Programme 2004.

Regarding the forms of activism measured only in the ISSP survey, group differences are again non-significant in Brazil. Blacks in the United States are overall less engaged in rallies and fundraising campaigns, and contact politicians less often than their White counterparts. In South Africa, small, non-significant group differences are found for contacting politicians or the media as well as for fundraising; Black respondents are, nevertheless, significantly more active in political rallies.

Overall, the descriptive results for political activism provide partial support for H1, H4a, and H5.

Voluntary associations

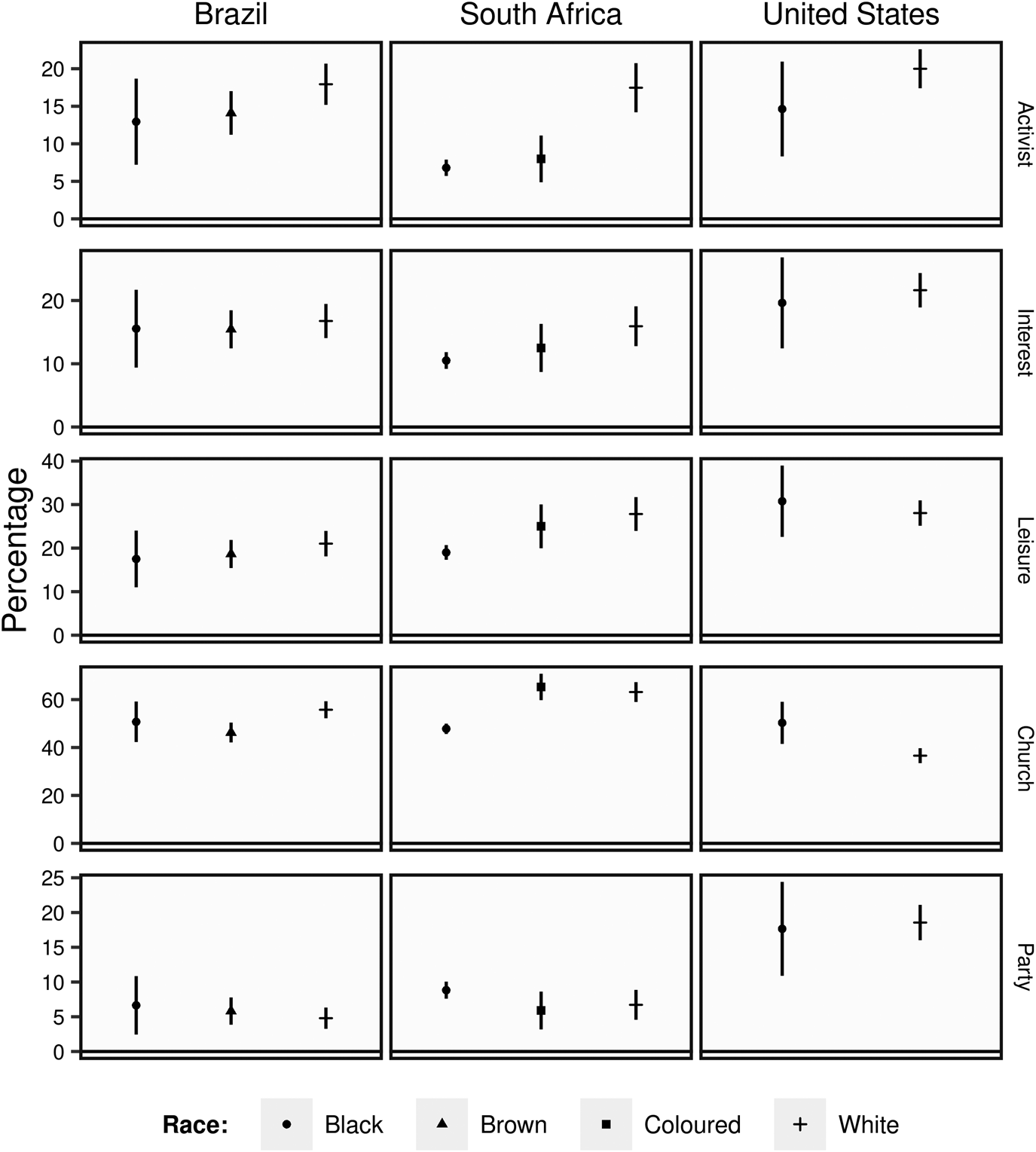

Figure 2 presents participation in voluntary associations and organizations. Again, no significant group differences are found in the Brazilian data. White respondents report higher levels of associative behavior, yet only by modest, non-significant margins. Group differences exceed 5% only for active participation in churches, where there is a 10-point distance between Browns (45%) and Whites (55%); Blacks fall in between (50%).

Figure 2. Participation in voluntary organizations.

Source: World Values Survey: Round 5.

Blacks in South Africa are less active in all kinds of voluntary organizations except for political parties. Coloured and White respondents are similarly more active than Blacks in non-political organizations such as leisure associations and churches. Whites are more involved than other groups in organizations with a political character such as activist and interest groups, especially the former.

The United States exhibits a different pattern. Blacks and Whites report similar levels of participation in parties, leisure, and interest groups, yet diverge regarding other organizational types. Although Whites are about 8% more active than Blacks in activist associations (yet non-significant), Blacks are 10% (and significantly) more prone to be active church members.

The descriptive results for participation in organizations in Brazil support H5. The findings from the United States provide strong support for H3, and H4a gathers modest support only for activist organizations. The results from South Africa provide support for H3 and H4a; higher Black participation in political parties in South Africa supports H1.

Regression analysis

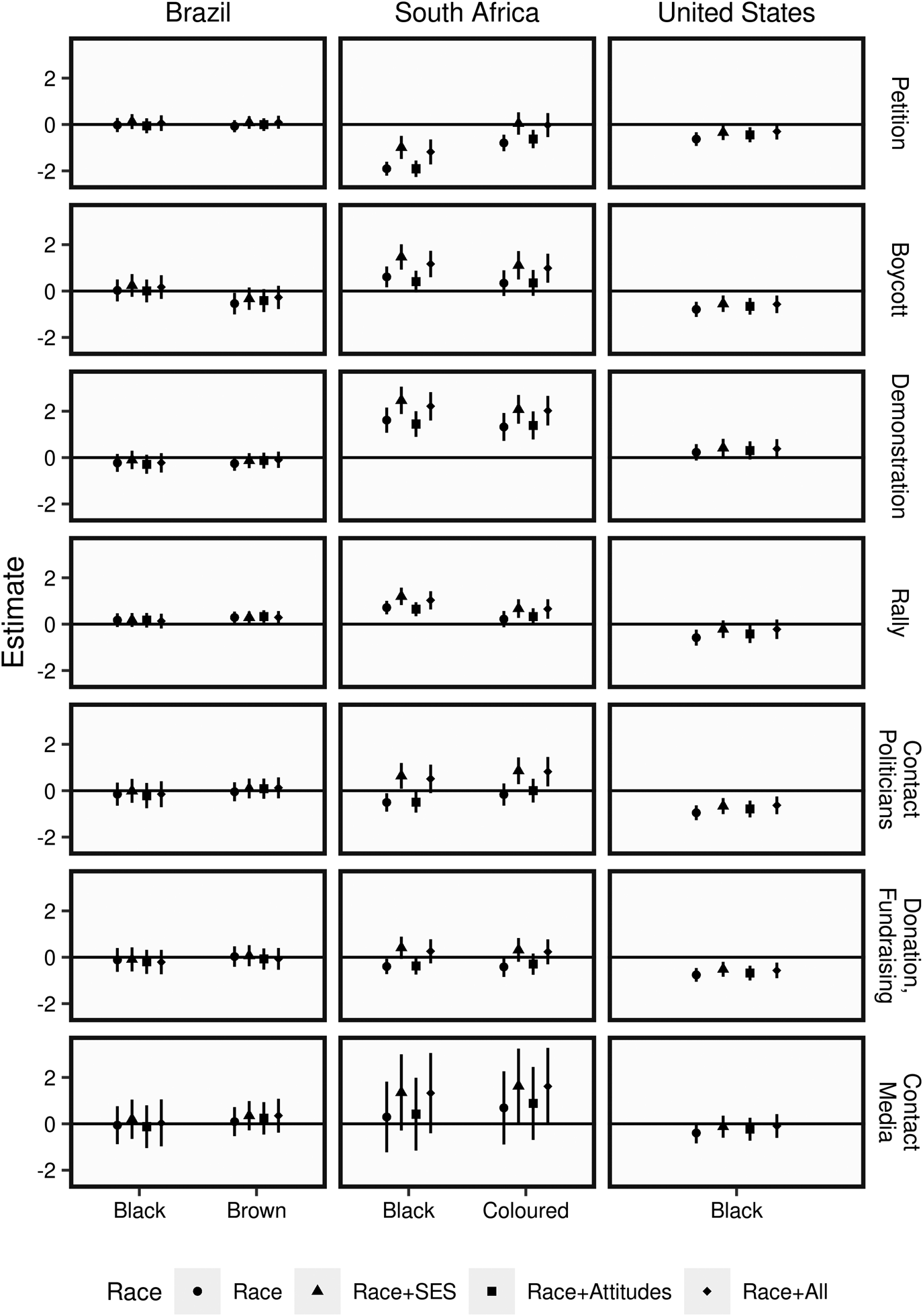

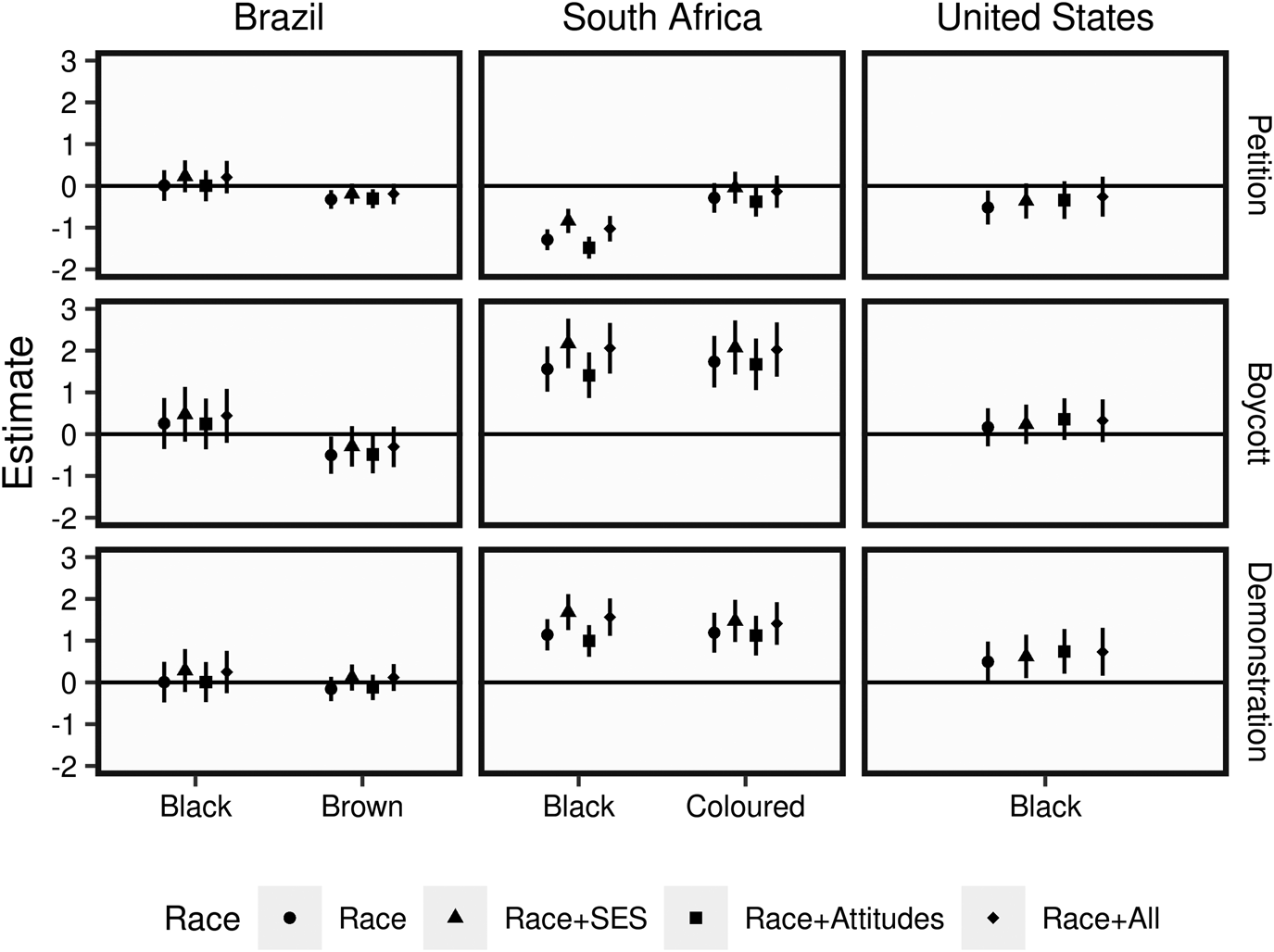

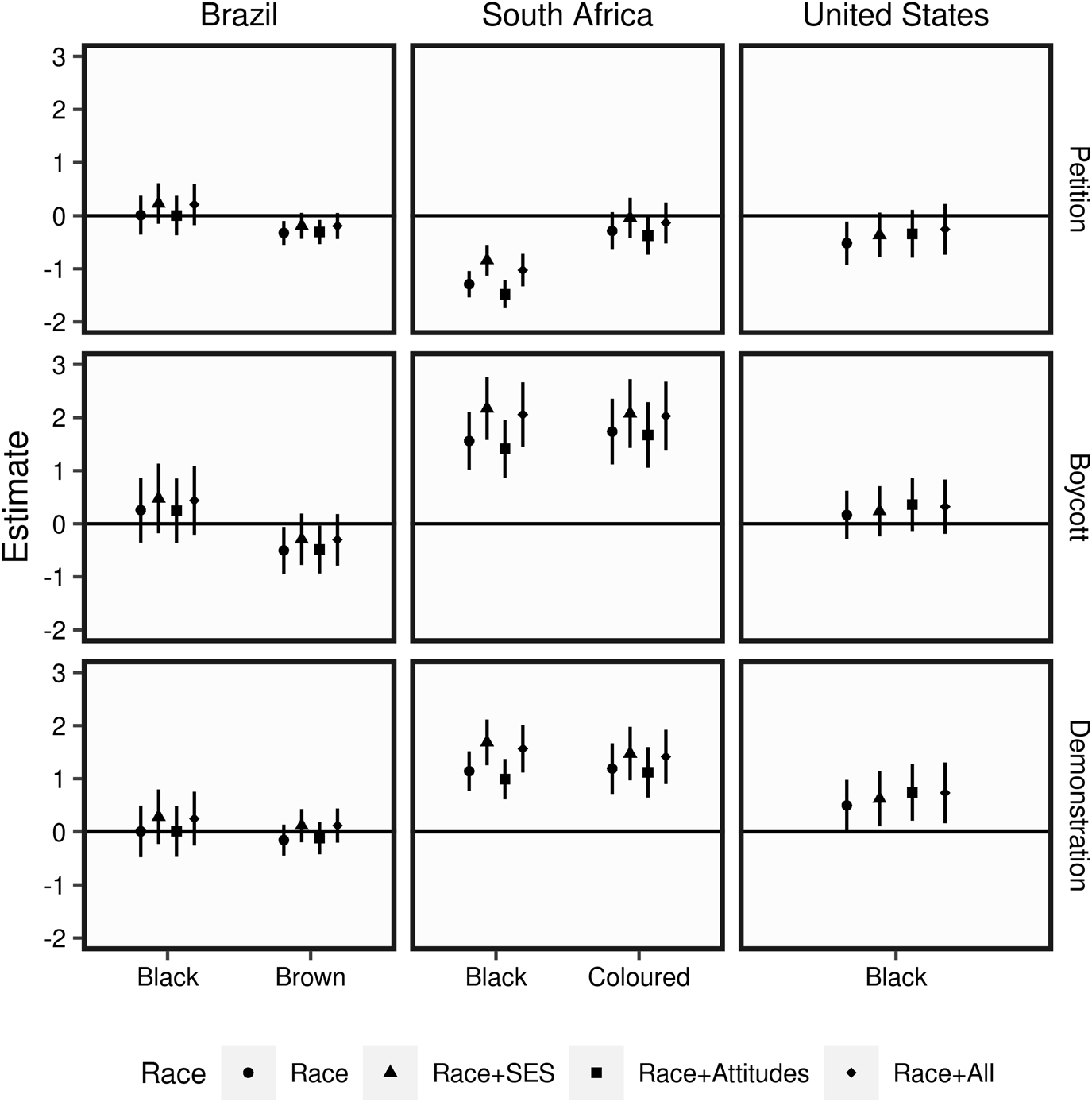

The evidence presented thus far displays the proportion of respondents in each race group that have been engaged in various political activities and organizations across contexts, and provides preliminary support for several of the paper's hypotheses. These results, however, do not account for concurrent predictors of political participation. A series of logistic regression models are fitted to ISSP and WVS data to examine whether the group differences (or the lack thereof) in political activity and membership in voluntary organizations presented in Figures 1 and 2 remain after controlling for predictors of political participation such as sociodemographics and political attitudes. In all regression models, the predictor of interest is the respondent's race. Figures 3, 4, and 5 report logistic regression coefficients along with 95% confidence intervals for Blacks, Browns, and Coloureds, respectively—Whites are set as the reference category.

Figure 3. Race as a predictor of political activism (ISSP).

Source: International Social Survey Programme 2004.

Note: Figures report logistic regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. “Race” indicates race categories as the only predictor in the model; “Race + SES” indicates the inclusion of sociodemographics as control variables; “Race + Attitudes” indicates controlling for political attitudes; “Race + All” indicates controlling for both sociodemographics and political attitudes.

Figure 4. Race as a predictor of political activism (WVS).

Source: World Values Survey: Round 5.

Note: Figures report logistic regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. “Race” indicates race categories as the only predictor in the model; “Race + SES” indicates the inclusion of sociodemographics as control variables; “Race + Attitudes” indicates controlling for political attitudes; “Race + All” indicates controlling for both sociodemographics and political attitudes.

Figure 5. Race as a predictor of organizational membership (WVS).

Source: World Values Survey: Round 5.

Note: Figures report logistic regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. “Race” indicates race categories as the only predictor in the model; “Race + SES” indicates the inclusion of sociodemographics as control variables; “Race + Attitudes” indicates controlling for political attitudes; “Race + All” indicates controlling for both sociodemographics and political attitudes.

Political activism

The findings for the United States show important differences in group political behavior across types of acts. Blacks participate more in demonstrations than Whites in all scenarios in the WVS data; in the ISSP, the difference in participation is significant when accounting for SES, but not when controlling for political attitudes. These results offer some support for H2, especially given that the small sample size for Blacks in the U.S. samples may contribute to large standard errors. The effect of SES on the ISSP supports prior findings in the literature that Blacks are more active in selected political acts than Whites after accounting for sociodemographics (Orum, Reference Orum1966; Olsen, Reference Olsen1970), which contradicts the resource approach and H4b in the context of mobilization-demanding acts. The findings for boycotting differ across surveys: Whites are consistently more active than Blacks in the ISSP, and no differences were found in the WVS data. Further exploration of this divergence is beyond the scope of this paper. Blacks do sign petitions and attend rallies less often than Whites, but this group gap vanishes after controlling for sociodemographics, which supports H4a and H4b. However, and contrary to H4a and H4b, Blacks also contact politicians and participate in fundraising less often than Whites. No difference is observed for contacting the media.

The findings from Brazil suggest that group differences in political activism are minimal, if any, and are not robust to controlling for sociodemographics, which provides strong support for H5. The results do not support H4a, for the country's remarkable racial disparities are not reflected in between-group levels of political activism. Rallying is the sole exception: Browns are statistically more active than Blacks and Whites, even though the substantive difference is minor (see Figure 1).

The findings from South Africa indicate important differences in political activism across racial groups conditional on the mode of participation. Blacks participate more than Whites in boycotts, demonstrations, and rallies. Coloureds are more active than Whites in demonstrations, and also in boycotting and rallies after accounting for sociodemographic variables. Differences in group propensity to act increase for Blacks and Coloureds compared to Whites after sociodemographics are accounted for. The results for mobilization-intensive participation support H1 and H2 but not H4a and H4b. Whites consistently petition more often than Blacks, but not more often than Coloureds after controlling for SES. Group differences in fundraising are non-significant and reverse for contacting politicians, in a pro-Black and pro-Coloured direction, after controlling for SES. Group differences are not significant for contacting the media, although they reach statistical significance for Coloureds after controlling for SES. Overall, the results for South Africa challenge the resources approach to political participation.

Voluntary organizations

The results for Brazil, displayed in Figure 5, again support H5. Blacks, Browns, and Whites in Brazil differ little in their propensity to join organizations. There is one exception: Browns in Brazil, counter-intuitively, report lower levels of church membership even after controlling for resources and attitudes.

The results from the regression analysis in the United States are consistent with Figure 2. Contrary to H4a and H4b, no significant group-level differences in membership in activist, leisure, and interest organizations or political parties are detected between Blacks and Whites. Blacks are more active members of churches, and group differences are robust to the inclusion of controls in the regression models, supporting H3.

In South Africa, Blacks are overall less engaged in organizations compared to the other groups in most scenarios, except for political parties; Whites are more active than Blacks and Coloureds in activism organizations. After accounting for SES, Blacks close the participatory gap in interest groups and, importantly, are more active in political parties than Coloureds and Whites. Finally, Whites and Coloureds are more active in religious institutions than Blacks.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper examines the salience of race as a predictor of political participation in three societies with large racial inequalities and different racial dynamics. I argue that race is itself a strong driver of participation in some political acts and organizations, conditional on the politicization of racial identities. I hypothesized that in societies where race has been politicized, and group membership been constructed and enforced by state actions to implement discriminatory policies (and as an active reaction to them), race has become a salient political force for group mobilization that can offset the lack of other factors and resources. Importantly, because the enforcement of group boundaries strengthens identities and solidarity networks, I argue that the consequences of politicized racial identities should be more noticeable for participation in acts that demand organization and mobilization. I derived working hypotheses from this argument and from prior studies, and tested them using empirical data from two large-scale comparative surveys.

The findings presented above demonstrate that, even though socioeconomic factors are important predictors of political participation, race offsets the differences in socioeconomic resources with regard to participation in acts that require group mobilization and organization in societies such as the United States and South Africa, where race has been a major politicized dimension (Marx, Reference Marx1998). In the United States, Blacks are more active in demonstrations, and eventual gaps in participation in rallies vanish after controlling for sociodemographic factors. Black Americans are also more active in churches, an important type of organization in their historical struggle against inequality and stigmatization in the country (McAdam, Reference McAdam1982; McDaniel, Reference McDaniel2008). However, Blacks in the United States participate less than their White counterparts in more individualized or resource-demanding acts such as signing petitions, fundraising, and contacting politicians, even after controlling for socioeconomic and attitudinal variables, which challenges the resources-based approach to political participation (e.g., Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman, Brady and Nie1993, Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995). In South Africa, non-Whites (Coloureds and Blacks) are more prone to boycotting, joining demonstrations and political rallies than Whites. What is more, after accounting for sociodemographics, the predicted level of participation of Blacks and Coloureds in those acts increases compared to Whites' expected level of engagement. South African Whites more actively participate in individualized political acts such as petitioning and joining activist organizations; for other associations, Coloureds and Whites display similar levels of organizational involvement. Interestingly, Blacks in South Africa are less engaged with the institutional church, which may reflect the role of certain denominations in fostering Afrikaner nationalism (Ritner, Reference Ritner1967; Lalloo, Reference Lalloo1998), but have a higher chance of membership in political parties once socioeconomic factors are controlled for. This finding may reflect both the historical role of the African National Congress for that population (Thompson, Reference Thompson2000; Ferree, Reference Ferree2006) and the fact that formal membership may be eventually deflated among Blacks due to an absence of factors associated with party membership (e.g., formal education and recruitment networks). Substantive group-level differences in political participation and organizational membership are mostly absent in Brazil. Although this result corroborates the existing literature on the lack of group mobilization along racial lines in the country (Telles, Reference Telles1996), it remains puzzling given the remarkable overall racial inequalities in the country and demands further investigation. On average, Whites are better-off than Blacks and Browns; thus, one could expect to find that Whites are more politically active even if the participatory gap dissipates after controlling for sociodemographic and attitudinal variables, as predicted by the resources approach to participation. All in all, the findings presented in this paper pose important challenges for the resource-based approach in contexts characterized by deep racial inequalities, where it should prevail.

The argument that politicized group identities have an important effect on political behavior, particularly on mobilization-intensive political acts, is supported by evidence from multiple surveys. In the United States and South Africa, countries that experienced racial projects that emphasized “bright” group boundaries for the enforcement of segregationist policies throughout most of the twentieth century, Blacks and Coloureds are recurrently more engaged in direct, mobilization-intensive political action, but not in other modes of participation, which indicates that group identity and consciousness provide a type of “heuristic” (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981; Dawson, Reference Dawson1994; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Eugene and Watts2009) that promotes participation in collective but not more individualized actions. The comparison to Brazil makes it clear that the existence of racial disparities and grievances alone might not suffice to foster political participation along racial lines. The politicization of group boundaries, even if they result from exclusionary political processes, proves to be an important force for the emergence of group consciousness and the mobilization of deprived groups.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2021.29.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank David O. Sears, Boris Sokolov, Mattias Wahlström, Joost de Moor, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.