Political parties are agents of gender representation by making gender claims and proposing gender-related policies. In the early 1990s, political parties were ‘the missing variable’ in the gender and politics literature (Baer Reference Baer1993: 547). Since then, a burgeoning literature has examined the relationship between gender and political parties in established democracies (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs and Kantola2016; Espírito-Santo et al. Reference Espírito-Santo, Freire and Serra-Silva2020; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006, Reference Kittilson, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013). However, some issues remain unexplored. The need for research on political parties' representation of gender in the context of democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe persists. Moreover, existing accounts of feminized political parties do not accommodate claims arising from neoconservatism, populism and anti-gender campaigns. Furthermore, scholarship tends to focus on fulfilling electoral pledges (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed and Naurin2017) rather than promissory representation, that is, claim-making and pledges in electoral campaigns.

Consequently, this article is guided by the following research question: how are political parties gendered ideologically? Three sub-questions are proposed: how and why do parties make representative claims about women and gender? What are parties’ gender-related policy pledges? How does democratic backsliding affect gender ideology? Drawing on representation theory and gender and politics research, this article proposes a new framework to analyse a diversity of claims concerning women and gender, and policy pledges made by political parties during an election campaign. This framework is then tested with reference to Polish political parties involved in the 2019 parliamentary elections.

Poland is a particularly interesting country in which to investigate this subject because of its political, cultural, historical and gender justice context. Politically, a range of ideologies are represented, although the majority in parliament is held by the right-wing populist Law and Justice (PiS) party, in power since 2015 and re-elected in 2019. PiS is alleged to have instigated democratic backsliding (Markowski Reference Markowski2020). Culturally, the Catholic Church, which strongly favours traditional gender roles, plays a major role in society and politics, and supports PiS. Historically, communism advocated women's education, employment and abortion rights but severely limited their political rights. In terms of gender justice, women's rights and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) rights have worsened since PiS rose to power. In 2019, Poland ranked 24th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index (EIGE 2019) and was the second worst in its measure of LGBTQ+ equality laws and policies (ILGA Europe 2019).

This article makes an important contribution to the scholarly literature in several ways. First, by adopting a ‘thick’ conception of gender understood in binary and nonbinary terms, the analytical framework not only considers the heterogeneity of women's interests but also contributes an LGBTQ+ dimension and gender-related policies. The work also differentiates a scholarly understanding of gender ideology as a set of ideas, attitudes and views on gender that provide a foundation for gender-related policies from its populist understanding as a threat to the traditional family and conservative values. Second, the article demonstrates that a party's ideology and representation of gender is not straightforward and requires detailed qualitative analysis to uncover complexities and a more nuanced understanding of how parties accommodate different sorts of claims. By examining Polish political parties, this article discerns diverse gender ideologies, including a populist element. Third, the article's focus on political representation during an electoral campaign – of what Jane Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge2003) calls promissory representation – highlights parties' commitment to fulfil election pledges, but little is known about how claims and pledges are made. Hence, this study will address this gap.

Literature review

Ideology affects the representation of women (Campbell and Erzeel Reference Campbell and Erzeel2018; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs and Kantola2016; Kittilson Reference Kittilson, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003) and LGBTQ+ people (Brettschneider et al. Reference Brettschneider, Burgess and Keating2017). Research shows that leftist parties advocate egalitarian beliefs and are known for their greater support for gender equality and affirmative action (Caul Reference Caul1999). Since the left endorses equality, it has favoured marginalized groups, including women and LGBTQ+ people. Left-wing parties tend to nominate more female candidates than right-wing parties (Krook and Childs Reference Krook and Childs2010; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris1993; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2007) and exhibit higher levels of substantive representation of feminist interests (Erzeel and Celis Reference Erzeel and Celis2016). Andrew Reynolds (Reference Reynolds2013) shows that social democratic, socialist, communist and green parties have more LGBTQ+ MPs than other parties.

Previous studies have demonstrated that conservatism entails gendered claims (Celis and Childs Reference Celis, Childs, Celis and Childs2014), weak equality policies (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2018) and low political representation of women (Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris1993). However, scholars are now highlighting advances made by right-wing parties in Western Europe to include women (Kittilson Reference Kittilson, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013; Shames et al. Reference Shames, Och and Cooperman2020) and demonstrate that laissez-faire conservatism can be compatible with liberal feminism (Campbell and Erzeel Reference Campbell and Erzeel2018; Celis and Childs Reference Celis, Childs, Celis and Childs2014, Reference Celis and Childs2018; Erzeel et al. Reference Erzeel, Celis, Caluwaerts, Celis and Childs2014). Moreover, Reynolds (Reference Reynolds2013) argues that in the UK a growing number of openly gay MPs have come from the Conservative Party.

Research on gender and agrarian parties is limited. Since traditional morality is at the core of their ideology, one could expect them to support gender traditionalism. In the past, rural parties included, on average, more women than left socialist parties (Caul Reference Caul1999).

Initial research on far-right parties has demonstrated that such parties send no women to parliament (Caul Reference Caul1999). Recent studies, however, show that women's political representation has improved, and despite advocating for the traditional family, they also support gender equality (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2015). Although far-right populist parties have selected women party leaders, they also display signs of toxic masculinity (Daddow and Hertner Reference Daddow and Hertner2021), and it is not clear whether such parties exhibit a ‘genderedness that is very similar to the one found across right-wing party families’ (Spierings et al. Reference Spierings, Zaslove and Mügge2015: 6).

However, there is a need for more detailed research on gender ideologies at election times. Hence, the importance of promissory representation needs to be highlighted. Promissory representation is a type of representation in which voters choose and assess potential representatives based on the promises they make during election campaigns, which they then keep or fail to keep (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003). The study of promissory representation, however, tends to focus on pledge fulfilment (Thomson Reference Thomson, Royed and Naurin2017). Less is known about how and why gender claims and pledges are made by political parties.

Moreover, in Central and Eastern Europe, it is important to understand how democratic backsliding affects ideology and representation. Scholars argue that illiberalism and rising authoritarian populism endorse anti-feminist and anti-gender rhetoric (Korolczuk and Graff Reference Korolczuk and Graff2018). ‘Gender ideology’ is used as a catchall term by right-wing and far-right parties to imply that a gay- and feminist-led transnational movement is threatening the traditional family and conservative values, and is used to justify discrimination against women and LGBTQ+ people (Toldy and Garraio Reference Toldy, Garraio, Leal Filho, Azul, Brandli, Lange Salvia and Wall2020). PiS's electoral victory contributed to the intensification of the ‘culture war’ discourse and the strengthening of new anti-gender initiatives (Korolczuk Reference Korolczuk2020). Moreover, the rise of neoconservatism raises questions about gendered representation (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2021).

Finally, existing research tends to analyse gender and political parties by focusing on women. Lisa Young (Reference Young2000) offers a feminist responsiveness framework that examines responses by political parties to feminist movements' demands and assesses parties' feminist credentials by considering representational and policy responsiveness. Sarah Childs (Reference Childs, Cross and Katz2013) proposes a feminization framework that examines the nature of a feminized political party by assessing women parliamentary elites, women party members and women's concerns. Rosie Campbell and Sylvia Erzeel (Reference Campbell and Erzeel2018) discuss a gender ideology from a feminist perspective and subsequently propose traditional and feminist gender ideologies. However, these approaches are narrow in scope. Instead, there is a need to go beyond a feminist understanding and examine a diversity of claims, including non-feminist and LGBTQ+ claims, and a variety of gender-related policies. Consequently, a more comprehensive framework based on a ‘thick’ conception of gender is proposed below.

The conceptual and analytical framework

Gender in political science scholarship is diversely conceptualized. Karen Beckwith (Reference Beckwith2005) acknowledges that definitions of gender range from a simple synonym for sex to culturally specific dynamic interactions. Johanna Kantola and Emanuela Lombardo (Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017) suggest the need to study gender first as a complex socially constructed relation between masculinities and femininities and gender roles and norms; subsequently, analytical focus should shift away from biological sex, which treats men and women as binary opposites, to gender identities. Mary Hawkesworth (Reference Hawkesworth, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013: 47) proposes that gender as an analytic category necessitates ‘interrogations about the ways in which power operates to produce sex, gender and sexuality within specific racial, ethnic and national contexts’.

Consequently, this article argues that a ‘thin’ understanding of gender (as sex in binary terms) can be distinguished from its ‘thick’ understanding (in binary and nonbinary terms). This article uses a ‘thick’ understanding of gender to allow the inclusion of historically marginalized groups – that is, women and LGBTQ+ people. The need for research on women and politics persists (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2005) and the focus on LGBTQ+ people highlights sexual and gender diversity and justice (Brettschneider et al. Reference Brettschneider, Burgess and Keating2017).

This article draws on Michael Freeden's (Reference Freeden, Smelser and Baltes2001: 7174) definition of political ideology as a ‘set of ideas, beliefs, values, and opinions’ that provides ‘plans of action for public policy making’. Consequently, the study of claims (ideas) and policies is required. Michael Saward (Reference Saward2010) views claim-making as the core of representation and emphasizes how diverse and complex a representative claim can be. Karen Celis et al. (Reference Celis, Childs and Kantola2014) adopt a representative claim approach to study claim-making for women and women's issues (policies). If promissory representation is considered, then instead of policies, pledges need to be examined. Election pledges are commitments made through parties' programmes to implement certain policies (Thomson Reference Thomson, Royed and Naurin2017).

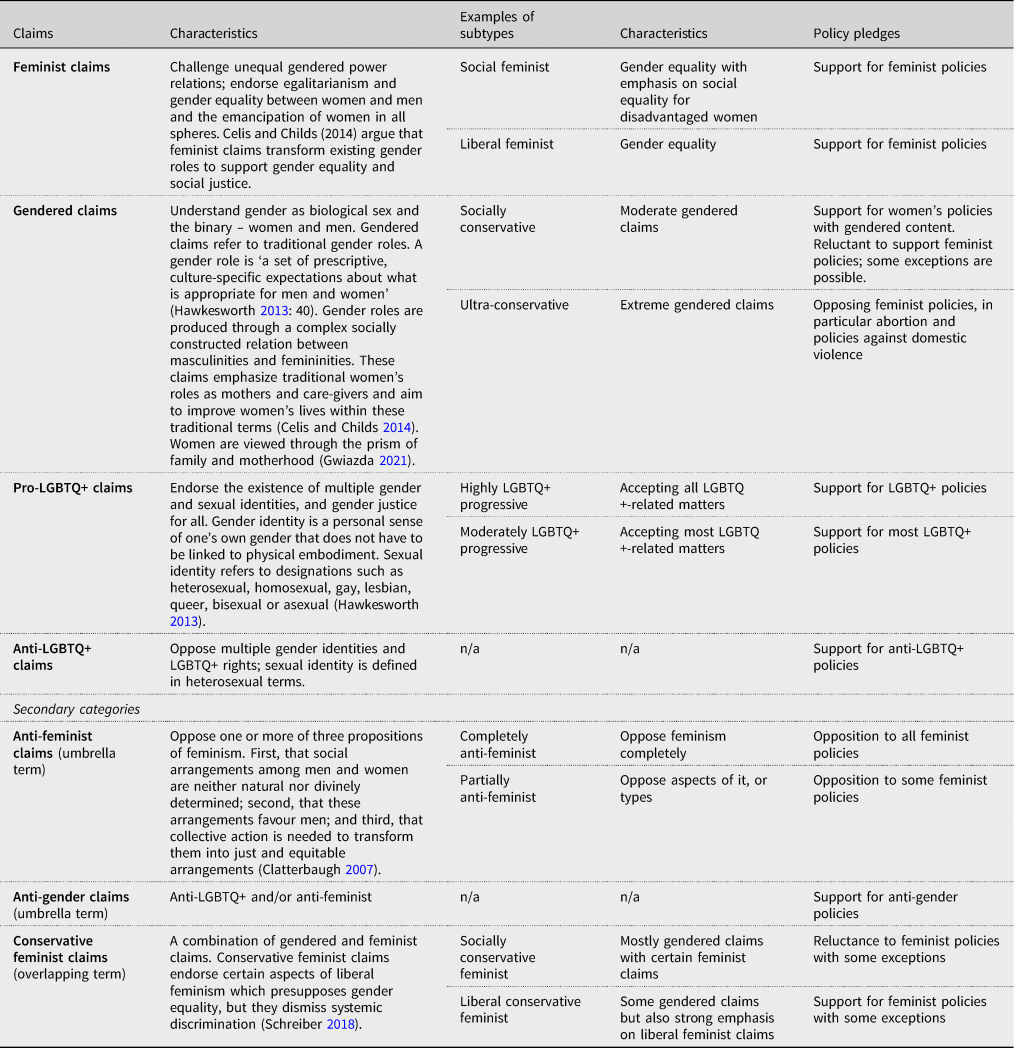

Consequently, to analyse party ideology systematically and to discern gender ideologies specifically, gender claims and gender-related policies are considered. Table 1 presents a gender ideology framework for analysis.

Table 1. Gender Ideology Framework for Analysis

In addition to claims defined in Table 1, ideology is concerned with gender-related policies. This term is used to encompass both gender equality policies and gender-related policies that continue to uphold inequalities. First, gender equality policies denote feminist and LGBTQ+ policies. Feminist policies are concerned with improving women's rights, reducing gender-based hierarchies and recognizing the intersectional complexities of women (Mazur Reference Mazur2002, Reference Mazur2017). Policies on reproductive rights, combating domestic violence or addressing the gender pay gap are examples. Conversely, LGBTQ+ policies are equality laws that focus on sexual orientation and gender identity, and are progressive because they treat all citizens equally (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2013). Policies providing for same-sex marriage, adoption and transgender rights are examples. Second, anti-gender policies (including anti-LGBTQ+ policies) contest gender-related issues, gender identities and complexities, hinder gender awareness and either present the concept of gender pejoratively or reject it completely (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2020). Finally, policies that relate to women but do not have the specific objective of enhancing gender equality can be discussed within the scope of women's policies with gendered content (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2021).

Claims are linked to gender-related policies. There is an expectation that feminist claims are congruent with feminist policies. Gendered claims can be congruent with women's policies with gendered content. Pro-LGBTQ+ claims are consistent with LGBTQ+ policies. Anti-LGBTQ+ claims are consistent with anti-gender policies.

The analysis of gender claims and gender-related policies facilitates the identification of gender ideology. For Shannon Davis and Theodore Greenstein (Reference Davis and Greenstein2009), gender ideologies are defined as views that people hold regarding gender roles in terms of a division of paid work and family responsibilities. Susan Philips (Reference Philips, Smelser and Baltes2001) argues that the study of gender ideologies is concerned with understanding differences in human views on women, men and alternative gender identities. Instead, I define a gender ideology as a set of ideas, attitudes and views on gender that constitute the foundation for gender-related policies. I propose to study a gender ideology as a gender dimension of political ideology using a ‘thick’ understanding of gender in its binary and nonbinary forms. This scholarly definition differs from a populist understanding of ‘gender ideology’ (in inverted commas), which is used by populists to denote a threat to traditionalism, conservative values and national identity.

Gender ideologies can be classified as traditional or egalitarian (Davis and Greenstein Reference Davis and Greenstein2009). In this article, traditional gender ideologies uphold traditional gender roles and a binary understanding of gender. Such views can result in any of the following: gendered claims, anti-LGBTQ+ claims, women's policies of gendered nature and anti-gender policies. Conversely, egalitarian gender ideologies endorse progressive gender roles and a nonbinary understanding of gender which encompasses alternative sexual identities and gender identities. Such views can result in any of the following: feminist claims, pro-LGBTQ+ claims, feminist policies and LGBTQ+ policies.

This analytical framework has several advantages. It is sensitive to the heterogeneity of women and gender and moves beyond the narrow feminist perspective. Moreover, this approach emphasizes the representative's role (in this case, political parties) in creating and framing claims and proposing policy actions. This framework is used for promissory representation but can also be applied to substantive representation.

Methodology

The advantage of using qualitative single-country studies is that they are more intensive and in-depth because they focus on particular features of a country (Landman and Carvalho Reference Landman and Carvalho2017) and are widely used in gender and politics research (Tripp and Hughes Reference Tripp and Hughes2018). In this article, a single-country study generates inferences about the gender ideologies of political parties.

This in-depth study is based on primary and secondary data. Primary sources include party manifestos and leaders' statements made during the 2019 electoral campaign. Party manifestos were available on parties' websites whereas leaders' statements were taken from online sources: Polish Radio, YouTube and broadsheet newspapers such as Gazeta Wyborcza, Gazeta Prawna and Rzeczpospolita. Primary data were analysed using content analysis. A qualitative content analysis ascribes meaning to text or verbal data through its interpretation by a researcher (Schreier Reference Schreier2012). Margrit Schreier (Reference Schreier2012) also clarifies that the main categories of a coding frame used in qualitative content analysis are the aspects on which the study focuses. In this article, the main categories are identified in Table 1. In addition, words such as women, mother and family were looked for specifically.

Five principal manifestos were examined. Moreover, several leaders' statements concerning gender-related matters were selected. Content analysis involved examining keywords (concepts) and themes (pledges) in manifestos and speeches. The author's knowledge of the Polish language was indispensable since written and verbal texts were in Polish. Both conceptual and relational analyses were used to identify gender ideologies (Le Navenec and Hirst Reference Le Navenec, Hirst, Mills, Durepos and Wiebe2010). Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of specific concepts in a text. Relational analysis examines the relationships among concepts and themes, in this case, the relationship between claims and pledges.

Secondary sources included the scholarly literature and reports published by international agencies. The European Institute for Gender Equality and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) publish reports on women's empowerment and LGBTQ+ people in Europe, respectively. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) report highlighted problematic aspects of the 2019 elections in Poland. Finally, the Institute of Public Affairs is a Polish research institute publishing regular reports on women in politics.

Poland

Table 2 presents the 13 October 2019 election results.Footnote 1 PiS was re-elected for a second term, securing 43.6% of the votes. The main opposition, the Civic Coalition, led by the liberal-centrist Civic Platform, won 27.4% of the votes. The Democratic Left Alliance (the Left) returned to parliament after a four-year absence and finished third with 12.6% of the votes. The Polish Peasant Party secured 8.6% of the votes. Finally, a new entrant, the far-right Confederation, received 6.8% of the votes. All five electoral committees, although formally registered as single parties, were de facto party coalitions (Markowski Reference Markowski2020).

Table 2. 2019 Election Results

Source: State Electoral Commission (2019).

Note: *Based on self-declaration in public media.

In the Senate, PiS won 48 of 100 seats, the same number as the Civic Coalition (43), the Polish Peasant Party (3) and the Left (2) combined, which concluded a pre-election pact not to run candidates against each other to secure a win over PiS. Three of four independents were elected with opposition support.

Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS)

Law and Justice (PiS) is a right-wing populist party, established in 2001 under the leadership of twin brothers Lech and Jarosław Kaczyński, in power from 2005 to 2007 and since 2015. The PiS electoral list also included candidates from two small parties: Solidarity Poland (Solidarna Polska) and the Agreement (Porozumienie). They have 18 deputies and 2 senators each. PiS promotes social conservatism in economic and moral spheres and advocates social transfers and state intervention in the economy, and traditional values and morality derived from the teachings of the Catholic Church. The party's national conservatism connects national traditions and identity with Catholicism. The party's populism clearly identifies enemies and is illiberal in essence (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2020). In power, PiS has been accused of repeatedly violating constitutional norms, dismantling checks and balances, infringing judicial independence, parliamentary procedures and citizens' rights and controlling public media (Markowski Reference Markowski2020).

The 2019 PiS manifesto contains claims and policy pledges concerning women. It refers to women 34 times, mothers 5 times and the family 124 times. The party claims it takes care of ‘the proper position of women in society’ but views women equivocally. On the one hand, its socially conservative focus on the traditional family is apparent by endorsing a ‘Family first’ slogan. According to PiS, a family includes a union of a man and a woman, which forms the foundation of social life and should be protected from ‘gender ideology’ (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość 2019). PiS provides extended childcare benefits (the Family 500+ programme) and pension benefits for mothers who never worked or gave up working to raise four or more children (Mama 4+). Women are seen as mothers and part of the traditional family; hence gendered claims are promoted. Moreover, PiS opposes ‘eugenics and abortion on demand’ (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość 2019).

On the other hand, PiS also endorses conservative feminist claims. The party's manifesto stipulates: ‘Men and women are different, but it cannot justify a gender pay gap. That is why we will put forward proposals to address inequality in the workplace’ (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość 2019). Addressing the gender pay gap is its new pledge. The manifesto also mentions improving women's opportunities in promotion and recruitment and reconciling work with childcare. The ‘gender equality in the workplace’ section covers almost three pages of the 232-page manifesto.

PiS interprets gender in binary and populist terms. During the election convention, party leader Jarosław Kaczyński said, ‘We object to same-sex unions, their marriage, and their right to adopt children.’ Then he added, ‘there are only two sexes: women and men’ (Kaczyński Reference Kaczyński2019). This binary view of gender endorses anti-LGBTQ+ claims and policies, which is combined with a populist claim. PiS promises to ‘stop the spread of “gender ideology” because its impact is growing, especially among young people, and contributes to the growth of unfavourable attitudes towards the traditional family and having children’ (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość 2019). PiS supported an anti-gender citizens' legislative initiative to ban sex education because ‘it introduces “gender ideology” and LGBT rights’ (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2020). ‘Gender ideology’ is mentioned twice in the manifesto.

These claims were widely propagated in public media. PiS turned public media into a partisan propaganda machine, which is an element of democratic backsliding (Markowski Reference Markowski2020). This allowed PiS to control the public discourse during the electoral campaign and exclusively promote its own claims and policy pledges.

Overall, PiS voices gendered claims that advocate the preservation of traditional family and gender roles, a conservative feminist claim promoting gender equality in employment and anti-LGBTQ+ claims questioning the existence of gender and sexual identities. PiS promises to improve women's situation in the workplace and implement women's policies (childcare benefits) but opposes LGBTQ+ policies and abortion on demand. PiS's control of public media entails the monopolization of its gender ideology.

The Civic Coalition (Koalicja Obywatelska, KO)

The Civic Coalition (KO) is composed of the Civic Platform, the Modern Party, the Green Party and the Polish Initiative (having 119, 8, 3 and 4 deputies in the Sejm, respectively). The Civic Platform is a centrist liberal party. Established in 2001 as a liberal conservative party, it was in government from 2007 to 2015. It holds largely liberal views on the economy and social and moral issues (although there is also a conservative faction). The Modern Party, established in 2015, is a liberal party promoting, among other things, women's rights. The Green Party established in 2003 won its first seats in parliament in 2019.Footnote 2 Finally, the Polish Initiative is a minor leftist party.

The KO's manifesto makes several feminist claims and policy pledges. Women are mentioned 25 times in a 136-page manifesto which also includes a special section entitled ‘Women's Rights’. It encompasses: protection against different types of domestic violence; support for women in securing child alimony; state funding for in vitro fertilization; free anaesthesia during childbirth; full access to prenatal tests and perinatal care; sex education in schools; accessible and reimbursed contraception; gender pay gap elimination; pension gap elimination; protection against labour market discrimination and promotion of female progression in the workplace; introduction of gender quotas for middle and senior management positions in state institutions and state-owned companies; reconciling work and family life; increasing the number of places in nurseries; and the introduction of two-month paternity leave (Koalicja Obywatelska 2019). One leader of the Civic Platform has also confirmed that the Family 500+ programme would be continued (Schetyna Reference Schetyna2019). Because this policy pledge is discussed in combination with affordable public nurseries, this claim is socially feminist. The KO supports modern egalitarian families with an equal division of caring responsibilities between partners (Koalicja Obywatelska 2019).

Regarding other aspects of gender, the KO has called in the manifesto for legal recognition of civil partnerships for heterosexual and homosexual couples. Moreover, the mayor of Warsaw (from the Civic Platform) signed a declaration protecting LGBTQ+ rights. The KO is moderately LGBTQ+ progressive and does not openly support same-sex marriage and adoption.

Overall, the KO represents liberal and social feminist claims and supports feminist policies. Furthermore, it is moderately LGBTQ+ progressive.

The Democratic Left Alliance (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD)

The Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), also called the Left, ran as a party coalition of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), Spring (Wiosna) and Together (Razem), gaining 24, 19 and 6 seats in the Sejm, respectively. The SLD was established in 1991 as the direct successor to the Communist Party, but over time it became a modern social democratic party. Liberal-left Spring, founded in February 2019, is led by LGBTQ+ campaigner Robert Biedroń, currently an MEP and the first openly gay politician in Poland. The radical left, Together, formed in 2015, has promoted social justice for women and minorities and protested against restricting abortion rights.

The Left offers a broad leftist programme addressing issues ranging from socialist concerns about unemployment, the rising cost of living and taxation, to environmental concerns (energy and climate issues) and sociocultural progressive policies concerning abortion, and gay and women's rights (Markowski Reference Markowski2020). The female leaders of the Left called on the opposition to support the ten-point ‘Pact for Women’ which inter alia addressed domestic violence, in vitro public funding, abortion and sex education. The Left has the highest proportion of women in its ranks in the Sejm (43%). The 19-page election manifesto mentions women five times and includes a separate ‘Women's Rights’ section which covers: (1) abortion liberalization; (2) reimbursement of contraception and (3) gender parity in central and local governments and state companies (Lewica 2019). Moreover, the manifesto calls for full reimbursement of in vitro fertilization, addressing the gender pay gap, sex education and a free nursery place for every child. The manifesto also highlights social rights that promote social inclusion and social solidarity.

Regarding LGBTQ+ issues, the main pledges are to introduce ‘marital equality for all’ and ‘sex education in schools’ (Lewica 2019). They derive from Spring's five proposals for LGBTQ+ people, including: legalization of civil partnerships; legalization of same-sex marriages; amendment of the Criminal Code to include hate crimes motivated by the victim's sexuality; changes to gender recognition law; and sex education (Gazeta Prawna 2019). The Left has three openly gay deputies. A leader of Spring has also defended women's rights, saying, ‘There is no equality without equality for women. Democracy without women is half democracy’ (Biedroń Reference Biedroń2019).

Overall, the Left represents social and liberal feminist claims and is highly LGBTQ+ progressive. The Left wholeheartedly supports gender equality polices.

The Polish Peasant Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, PSL)

The Polish Peasant Party (PSL) aligned with Kukiz'15 under the label of the ‘Polish Coalition’, yet formally registered as the PSL for the 2019 election, gained 30 seats (including five seats for Kukiz'15). With roots in the pre-war period, the PSL is an agrarian party, established in 1990, and has been present in parliament since then. It has played a pivotal ‘kingmaker’ role, joining several post-1989 governments (Markowski Reference Markowski2020). Kukiz'15 is an anti-establishment party founded by a rock musician in 2015.

The PSL manifesto makes no explicit references to women or LGBTQ+ people. However, it has been argued that some of the party's proposals support women: for example, voluntary social insurance contributions for micro-entrepreneurs (who tend to be women because of the need to combine work with childcare) and an hour for the family (which shortens worktime by an hour for parents of children under the age of 10) (Druciarek et al. Reference Druciarek, Przybysz and Przybysz2019).

Although no references are made to women, mothers are mentioned twice and references to the family, childcare and elderly care are made that emphasize the traditional family model. The party supports the Family 500+ programme, free-of-charge crèches and ‘will enable mothers and fathers to combine work and childcare’ (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe 2019). In the campaign, the PSL leader said he would not support the Left's ‘Pact for Women’ because it endorses liberalization of abortion. Instead the party supported the 1993 law banning abortion (with exceptions) (Kosiniak-Kamysz Reference Kosiniak-Kamysz2019).

Overall, the party supports implicitly gendered claims, seeing women as mothers and part of the traditional family. There is a weak conservative feminist claim concerning policy reconciling work and family life. However, the PSL is against the liberalization of abortion. There are no LGBTQ+-related claims and policies. In sum, since hardly any explicit gender claims and pledges are made, the PSL can almost be considered gender-blind.

The Confederation Freedom and Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodleglość)

The Confederation Freedom and Independence is a far-right populist party registered in July 2019, following a coalition agreement between KORWiN and the National Movement in 2018.Footnote 3 While the former is ultra-liberal in economic terms and ultra-conservative in social terms, the latter is ultra-nationalist, xenophobic and anti-Semitic. The leaders present themselves as defenders of the traditional family, oppose immigration and multiculturalism, and are Eurosceptic although they support unconstrained trade exchange (Markowski Reference Markowski2020). In the 2019 elections, the Confederation gained 11 seats: five for KORWiN, five for the National Movement and one secured by the nationalist and traditionalist Crown (Korona), which joined the Confederation before the elections.

The Confederation is a men's party: it has no female deputies in parliament and women are not mentioned in its manifesto, which instead shows an image of a three-generational family – including a mother, a father, children and grandparents. The Confederation supports the traditional family model (Druciarek et al. Reference Druciarek, Przybysz and Przybysz2019).

The Confederation endorses anti-feminist claims and pledges. In an interview held before the 2019 elections, a leader of KORWiN said, ‘women are weaker and should earn less so there is no need to address the gender pay gap’ (Korwin-Mikke Reference Korwin-Mikke2019). He had already expressed this opinion at the European Parliament in 2017 (Euronews 2017). This misogynistic claim is completely anti-feminist. The Confederation strongly supports a total abortion ban and withdrawal from the Council of Europe Convention (Istanbul Convention) on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. The Convention is seen as being at odds with Catholic values and the traditional family and, according to the Confederation, could lead to teaching Polish schoolchildren about non-traditional gender identities.

Regarding LGBTQ+ issues, the main populist slogan is ‘Stop LGBT propaganda’, which is used three times in the 20-page manifesto. The Confederation urges its supporters to ‘defend schools from the invasion of self-proclaimed “sex educators” and propagandists of the LGBT movement and oppose indoctrination and promotion of its harmful ideology’ (Konfederacja 2019). In an interview, a leader of the National Movement warned against ‘an invasion of LGBT ideology which attacks national and traditional identity and natural sex identity based on two sexes’ (Winnicki Reference Winnicki2019). The Confederation has proposed the Charter of Polish Families (in response to a declaration promoting LGBTQ+ rights by the mayor of Warsaw), which calls for the revocation of the Istanbul Convention, a ban on sex education, and opposes same-sex marriage and state funding of LGBTQ+ organizations (TokFM 2019).

Overall, the Confederation voices ultra-conservative claims and opposes feminist policies. The Confederation's anti-LGBTQ+ claims are related to anti-LGBTQ+ pledges.

Concluding discussion

This article has examined how Polish political parties are gendered ideologically. Using a novel analytical framework, it has analysed the gender dimension of political ideology and discerned political parties' claims and policy pledges in the 2019 electoral campaign. Although leftist and liberal parties endorse feminist and pro-LGBTQ+ promissory representation and right-wing parties largely endorse gendered and anti-LGBTQ+ promissory representation, a detailed analysis shows a more nuanced picture. Specific findings are presented below.

First, this article shows that gender ideologies vary in Poland. Table 3 presents a summary. There is a strong correlation between wider political ideology and a type of gender ideology, but the conventional dichotomy needs to be qualified. Left and centre parties display egalitarian gender ideologies of two types. Whereas the Left is highly progressive and opts for all LGBTQ+ policies (Type 1), the KO is moderately progressive and advocates several LGBTQ+ policies (Type 2).

Table 3. Gender Ideologies in Poland

Conversely, right-wing parties display traditional gender ideologies of three types: Type 1 is mostly traditional and populist; Type 2 is implicit or gender-blind; Type 3 is ultra-traditional and populist. PiS represents Type 1 by making gendered claims that advocate the preservation of traditional family and gender roles, opting for women's policies with gendered content and being reluctant to adopt feminist policies. It also endorses anti-LGBTQ+ claims and policies. However, it does advocate gender equality in employment. Thus, PiS is mostly traditional but with a conservative feminist claim. It also voices a populist claim – ‘gender ideology’. The PSL represents Type 2 because of its implicit gender claims. The Confederation represents Type 3 and supports ultra-conservative gendered claims, anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQ+ claims and opposes feminist policies, specifically those supporting abortion and combating domestic violence. It also uses a populist claim – ‘gender (LGBT) ideology’.

A traditional gender ideology is qualified with new specifications. First, a populist dimension is identified. Populists consider society to be separated into two antagonistic groups: supporters and enemies (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Right-wing populist PiS and the far-right populist Confederation view LGBTQ+ people as enemies. They refer to ‘gender ideology’ as a threat to the traditional family, conservative values and national identity. By using ‘gender ideology’, PiS criticizes neoliberalism, while the Confederation ‘combines a desire to maintain a gender hierarchy and hatred towards “sexual degenerates” with anti-European Union sentiments and Islamophobia’ (Korolczuk Reference Korolczuk2020: 165).

Moreover, this article argues that PiS is mostly traditional (rather than fully traditional) because it supports a conservative feminist claim. This is somehow surprising given PiS's social conservatism. The cases of PiS and the PSL illustrate that conservative parties are now more willing to accept certain gender-equality policies in the public sphere (employment) but not in the private sphere (abortion). Furthermore, there is a difference between explicit claims (all parties except the PSL) and implicit claims (PSL). While it is expected that explicit claims are closely linked to pledges, implicit claims and pledges are vague, so a party is more flexible in terms of endorsing diverse gender-related policies. In fact, the PSL as a coalition government partner of the Civic Platform supported, for example, gender quotas. Finally, the far-right Confederation is more traditional than its Western European equivalents and is classified as ultra-traditional.

Second, political parties accommodate gender claims and pledges that derive from different sources. Egalitarian gender ideology relates to feminist and LGBTQ+ activism over the past decades. Following women's suffrage in 1918, under communism, women were granted rights to education, employment and abortion. This top-down emancipation and communist control of independent movements initially hindered women's political activism during democratic transition (Waylen Reference Waylen1994). The institutionalized feminism of nongovernmental organizations dominated in the early 2000s and is now followed by less formal grassroots forms of engagement that combine online activism with organizing demonstrations on the ground (Hall Reference Hall2019). According to Ewa Winnicka (Reference Winnicka2011), two strands of feminism can be discerned: liberal and leftist – the former represented by the liberal Congress of Women (supporting women's business and political elites), and the latter represented by the Women's Agreement of 8 March (supporting low-paid, disadvantaged and marginalized women). The Civic Platform has collaborated with the Congress of Women, while Left's Together represents disadvantaged women. Phillip Ayoub and Agnès Chetaille (Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020) emphasize that the LGBTQ+ movement born in the late 1980s was reinvigorated by Poland's accession to the European Union. Its claims were adopted by the Spring party – a member of the Left.

Traditional claims and pledges derive from the fact that Poland is a traditionally conservative country, influenced by the Catholic Church, where the traditional family plays a central role. Women have been assigned specific gender roles, best characterized by the traditional figure of the ‘Polish Mother’, Matka Polka (Hall Reference Hall2019). The term refers to a woman who has devoted her entire life to her family and to raising children in the spirit of traditional and patriotic values. The post-1989 period was marked by a pact reached between the new democratic government and the Catholic Church, which brought about restrictions on abortion in 1993, limiting women's reproductive rights (Hall Reference Hall2019). Moderately gendered claims are linked to this cultural and historical legacy. Ultra-conservative claims are closely linked to ultra-conservative organizations such as Ordo Iuris and Catholic Radio Maryja.

A populist element is related to the Catholic Church's opposition to ‘gender ideology’. Poland's anti-gender campaigns were initiated in 2012 by the Catholic Church and ultra-conservative organizations, following the Vatican's criticism of gender equality movements as powerful foreign colonizers (Korolczuk Reference Korolczuk2020; Korolczuk and Graff Reference Korolczuk and Graff2018). In Poland, anti-LGBTQ+ claims have been associated with the national tradition, equating Poles with Catholics, and highlighting the incompatibility of LGBTQ+ ideas with Polish culture (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020).

PiS's conservative feminist claim (gender equality in employment) could be attributed to stronger conservative feminist voices and the women's forum within the party (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2020). Yet, the complexity of claims-making can come from additional factors. It can result from the need to appeal to different sorts of constituencies, intra-party competition or a unilateral decision by the party leader. Future research should investigate these factors.

Third, political parties offer different gender ideologies to attract specific constituencies. Promissory representation offers a contract between parties and their constituents: specific claims and pledges are to secure votes. Traditional gender ideology is directed at conservative voters whereas egalitarianism is linked to progressive voters. A sociodemographic profile of the electorate can discern constituencies. According to Radoslaw Markowski (Reference Markowski2020), the PiS electorate represented almost two-thirds of the poorly educated, religious and socially conservative voters, older people and those living in rural areas and small towns; the KO was largely supported by the well educated and those living in big cities; the Left attracted many voters with a progressive appeal; the PSL appealed to rural voters and moderately religious and conservative voters; the Confederation was more than twice as popular with men than women and attracted the most radical voters from the nationalist conservative camp. The conservative feminist claim is likely be offered to the section of PiS supporters who have a different sociodemographic profile from the core one, but this link needs to be researched further.

Finally, the effects of democratic backsliding were visible in two ways: publicizing governing party ideology through the control of state media and prioritizing populist and illiberal claims, including anti-gender claims. Although international observers concluded that Polish parliamentary elections were prepared well, they were concerned about intolerant rhetoric and bias in public media (OSCE 2019). In fact, partisan propaganda aired by the public broadcaster promoted PiS's claims, including gendered claims and pledges. References to threatening ‘gender ideology’ were widespread. Since 2015, PiS has restricted women's rights and supported ‘LGBT-free’ zones (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2020). The 2019 electoral campaign brought into sharp relief PiS's populist and illiberal claims on public media. Thus, anti-gender claims and the resistance to gender equality are clearly connected with democratic backsliding. Andrea Krizsán and Conny Roggeband (Reference Krizsán and Roggeband2019) argue that the gendered dimensions of democratic backsliding include an assertion that gender equality is a value externally imposed and hence alien to national traditions and the closure of civic space and constraints on civil society organizations promoting women's rights and LGBTQ+ rights. Moreover, this article adds that the gendered dimension of democratic backsliding means the substantial exclusion of feminist and progressive claims, which compromises the quality of political representation.

In conclusion, this article contributes to a better understanding of gender ideologies by utilizing a novel framework to analyse Polish political parties. Moreover, it highlights the importance of promissory representation and how parties make gender claims and gender-related policy pledges. However, electoral promises do not necessarily result in policy outputs and outcomes. The best test of promissory representation involves examining ideology in practice, that is, the analysis of substantive representation and policy outputs. Further research should also examine intersectionality and intra-party ideological differences. Finally, future studies should gather information on the evolution of claims-making over time and on who determines claim inclusion in manifestos. In short, more research on gender, ideology and political parties is needed.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers for their very useful comments on this article.