French urban anthropology and subaltern populism

It is no secret that urban anthropology is a relatively new field in the French-speaking world. In 1983, the translator of Ulf Hannerz's famous book Exploring the City: Inquiries Toward an Urban Anthropology, Isaac Joseph, wrote in his preface:

The number of works in urban anthropology presented and discussed in Ulf Hannerz's book is impressive. Shall we count all those that the French public is unaware of? Those that are not translated and those that are virtually absent from the debates on urban scholarship in France? How shall we interpret the result: as a sign of theoretical provincialism, or as a lack of interest in issues that made the history of Anglo-Saxon anthropology? (Reference Joseph and HannerzJoseph, 1983: 7)

However, as early as the mid-1950s, works of ethnologists like Georges Balandier (Sociologie des Brazzavilles noires, Reference Balandier1955), the founder or at least the inspiration for what would henceforth be called dynamic anthropology, clearly fell within the domain of urban anthropology, as did those of his British colleagues of the Manchester school. Of course, decolonization and the repatriation of ethnology from the colonies to the metropoles played a role in the development of this branch, which is sometimes a refuge rather than a real choice of fieldwork. Reference GutwirthGutwirth (2008) admits to having done urban anthropology without being aware of it.

The development of urban anthropology in France is also linked to the larger debate on the scope and purpose of anthropology that took place in the 1980s, if we are to judge by the état des lieux, the “checklist” published by L’Homme in 1986.Footnote 1 It was basically about deciding whether, after decolonization and the creation of new nation-states in the former colonies deprived anthropologists of exotic fields, ethnology could still be maintained as a discipline studying “simple” societies; or whether, after giving up the exoticism triggered by the Great Divide between “simple” and “complex” societies, it was possible to apply its method to more closely related fields, even if it meant encroaching on traditional domains of sociologists, in this case, the city. Already, in the preceding years, an interest for the city could be observed across the humanities at large, as shown by Henri Lefebvre's Le Droit à la ville (Reference Lefebvre1968), or Manuel Castells’ La Question urbaine (Reference Castells1972). These works had a clear ideological bias, much like most approaches in urban anthropology and sociology. The aim was to show how the city reflects the “class struggle,” to put it briefly. In the ethnicist version that would follow, this antagonistic approach would show how minorities are spatially marginalized within cities and how neighborhoods take on the ethnic characteristics of their inhabitants. Thus, the word ghetto would progressively become a customary term to refer to ethnic neighborhoods.

Finally, the craze for urban anthropology can also be linked to the all-pervasive interest in everyday life rather than in major events, started since the 1930s by the historians of the Annales. To show how the city was of interest to intellectuals who were discovering everyday life in the 1980s, we could mention the chapter “Marches dans la ville” by Michel de Certeau's L’Invention du quotidien, a cult writer enforcing a philosophical, rather than a sociological approach. In any case, this “subaltern” orientation of urban studies, which still flourishes today through a wealth of studies on migrants, reflects very well the shift from the primitive in the bush to the workers and ethnic groups in the suburbs—thus entitling anthropologists to retain their knightly role as defenders of the oppressed, as if anthropology, barely rid of its colonial complex, had already chosen to serve a humanitarian mission. It is as Victor Hugo's or Charles Dickens’ writings, depicting the city as hell or as a cancer, served as inspiration for this “populist” (Reference AmselleAmselle, 2010) vision of urban anthropology.

Before I go into more detail about the new rich in their lavish homes, I would like to point out the inherent vagueness of the term “urban anthropology.” No one will dispute the truism that the world is becoming urbanized, yet little has been done to define the boundaries of the city or the urban (Reference AgierAgier, 1996). The ruralization of the city can be just as interesting to observe as the urbanization of the countryside or what is sometimes referred to as “rurbanization.” As for the palaces of the new rich in the former socialist countries, our topic, things are no less blurred since these residences can be found in the city centres, in gated communities, or even on a main road, often at the entrance or exit of a city. However, insofar as our study belongs to the domain of social representations and urbanism, or even architecture, rather than to an anthropology in the city—or of the city, as a meaningful wholeness—we cannot skip the study of space for social interaction or networks, as a well-established tradition in up-to-date urban anthropology would recommend (Reference AgierAgier, 1996).

The new rich

The sources for studying the nouveau riche in the region under consideration are meagre, and there is not much ethnography available either. Again, as a result of a spillover effect, scholarship on this topic largely focuses on outcasts, ethnic minorities, and, in the case of Romania and Bulgaria, the poor Roma (Reference RueggRuegg, 2009). True, the visibility of the new rich in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet world is a relatively recent phenomenon, which should be put in a two-fold context. On the one hand, the behavior of the new elites: they have become such through access to new lucrative jobs or positions in economy and politics (which provides the necessary capital); on the other hand, a wide variety of imported products have been made available in the East, along with better knowledge of fashion and trends (which makes the architectural projects we are going to describe possible). All of this was unattainable under the old regime. Affluent and privileged individuals could hardly display their wealth publicly. It is precisely this aspect—the public display of wealth—that characterizes the new rich in the East, in contrast to, for example, the (Protestant) bourgeois tradition, which requires people to keep their wealth hidden and to practice a certain parsimony, if not downright stinginess, as one can experience in austere Calvinist cities like Geneva.

The newly rich must now compete for recognition with international standards of wealth, which are widely displayed in luxury and social magazines, television shows, and other luxury industry events. Among the most common and visible signs of wealth is the car. We may easily recall Roland Barthes’ studies (Reference Barthes1957) on “contemporary” myths: the legendary Citroën ds was one of them, whereas today German and English models share the privilege of symbolizing wealth and status in the East. In addition to the cars themselves, which parades in front of their owners’ palaces, their emblems are sometimes used as decorative architectural elements, such as the Mercedes star in Romanian Roma palaces. The “German model” has been influential in East Central Europe since the 18th century, thanks to German settlements whose architectural traces are still visible in towns and villages, and despite their massive emigration during the last years of communism and after the reopening of the borders, when Germany enacted a very generous policy of reception. Clearly, in people's mind, this German model of efficiency and success is still a source of inspiration, all the more so as it is validated and enhanced by the foremost role of Germany within the European Union, at least in the economic domain.

Among the few existing works on nouveau riche in French anthropological scholarship, Marc Abélès’ essay (Reference Abélès2002) took into account the young new rich of Californian start-ups. His study shows above all how the practice of philanthropy changes across the generations, ranging from the cultural philanthropy of well-established foundations in the United States to the local actions of the new rich, often aiming at defending the environment. Albeit wealthy, these young entrepreneurs flaunt no palaces; they are content with luxury cars, fine wines, and extravagant meals. Sometimes, they even do their own shopping. This work is, therefore, of little use to us.

If we turn to an older study, Thorstein Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), we find a more systematic reflection on the symbolic aspects of wealth parading in relation to idleness. However, the historical, economic, and political contexts are now completely divergent from the region we are studying. Veblen argues that this idle rich class bases its authority precisely on the fact that it does not need to work. The new rich of the self-made man type, on the contrary, usually boasts of having succeeded through their work and set themselves up as a model in a liberal society where everyone can attain opulence. This late morality of the wealthy classes, ranging from the apology of idleness to the praise of work, corresponds to two ways of spending. The idle classes, in the tradition of aristocracy and of grand bourgeoisie that followed in its footsteps, practiced extravagant spending, whereas actual workers, even after they attained prosperity, tend to argue in favor of thrift, for saving paved their way to opulence. However, it soon becomes clear that these opposing categories are far too general to reflect the actual diversity of behaviors, especially of those who did not necessarily become affluent through their work, as may be the case in Eastern Europe. Are we witnessing a neo-aristocratic form of lavish spending among the new rich in the East?

The definition of the nouveau riche is usually based on the fact that they have not acquired the culture of spending that is merged with taste and refinement. In the case of the new rich in the region we are considering, ostentatious spending plays a definite role—it is all about social recognition of one's economic, hence social success, in an environment marked by external signs of poverty and underdevelopment, particularly in relation to infrastructure: amenities, road system, building materials, and so on. The new rich can hardly remain out of sight in such a context and inevitably take over the place occupied by the idle classes in the past, but they lack their culture and historical recognition. In addition, since the aristocratic and bourgeois classes were thoroughly wiped out, the new rich becomes all too visible. They are the only ones who stand out.

Franz Boas and Bronislaw Malinowski have shown how, among the Kwakiutl as well as among the Trobriand people, sumptuous spending brings honor and esteem to those who practice it—something Veblen had established long before. This mechanism, with the clientelism it produces, seems to cut across cultural boundaries. It is at work in all kinds of societies. However, the new rich we are focusing on are devoid of a culture and a habit of luxury spending, partly because luxury goods are scarcely available, partly because they tend to slavishly imitate those models they hold for the top of the social hierarchy, that is, North American soap operas.Footnote 2

Here, a great theorist of imitation can be of help. Gabriel Tarde (1890) has thoroughly studied the almost universal mechanisms of human imitation. In palaces, as we shall see, imitation rules: the idea is that, by copying Versailles or a Greek temple, I take over some of their own glory. For Tarde, imitation is a real social drive. Unfortunately, he was not particularly interested in architecture.

It is by relying on these theories of extravagant expenditure and imitationFootnote 3 that I will try to decipher the spectacular development of nouveau riche ostentatious architecture in the former socialist world, with a specific focus on the new rich Roma that I will closely observe. For lack of space, my argument will revolve around two aspects of this phenomenon: the struggle for recognition and high social status and lavish spending.

The invention of an honorable ancestry and the need for recognition

A key feature in the quest for social status is the evidence of a past, a lineage, conceivably but not necessarily glorious, such as quarters of nobility in Europe or genealogies in traditional societies. For want of noble origins or ancestors, one can join a lineage by taking on its appearance. Those who adopt the wig and the cane may be rare, but those who mimic illustrious architectural models in their residences are countless. The history of architecture must be called up here. The social representations of habitats that the owner regards as highly reputable and renowned serve as models for building the house and organizing the household space. The year 1989 marked a turning point in this fashion. From this year onward, it became possible to expand economic activities and exchanges with the West. The process was two-fold as new travel opportunities were created by the opening of the borders. It became possible to do business in the West, and to join in new economic activities developed by Western companies in the East, for example, in newly opened branches of international corporations or even in the vast ngo domain, funded by intergovernmental bodies or by the private sector in the West. Finally, key positions in new administrations could lead to quick fortunes. In the case of the Roma, it was rather thanks to the so-called informal economy (Reference Ruegg, Giordano and HayozRuegg, 2013) that they could erect vast palaces in the cities or the peripheries of East Central Europe. If we do not take this context into account, and if we do not refer to the history of architecture and its styles, the palace phenomenon would be hard to understand.

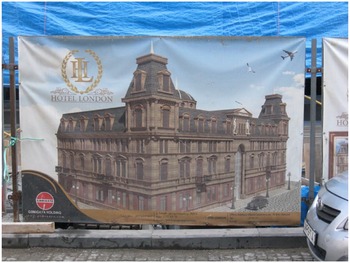

If we accept the fact that, for the new rich, the need for roots is paramount, it becomes clear why they would not venture into the latest contemporary architecture. On the contrary, they will try to slip into an existing tradition, preferably a venerable, long-established one, and present themselves as its heirs. Hence the use of iconic architectural elements, such as columns and capitals, selected according to their assumed “nobility” and antiquity. This strategy is by no means limited to the nouveau riche, let alone to the post-socialist era. The history of architecture brims with reinvented styles, usually preceded by the prefix neo: the neo-Gothic and the neo-classical are well-known examples. Not that the Renaissance did otherwise when it argued in favor of the ancient Greek and Roman civilization. Italy would indeed set the tone for polite and urban architecture, especially for the East: we need only mention Saint Petersburg. Late American reproductions of famous historical monuments, such as the Palazzo Vecchio of Florence in Boston or the myriad replicas of Las Vegas, share the same desire to create or rather to reinvent a tradition, that is, to recover and reclaim an illustrious past that would place you above suspicion. Reference Eco and WeaverUmberto Eco (1986), observing the “fake” of American “Enchanted Castles” puts it clearly: “Baroque rhetoric, eclectic frenzy, and compulsive imitation prevail where wealth has no history” (1986: 25–26). What should we say, then, of the new districts of Batumi in Georgia, whose buildings replicate England, France, Greek heroes (Figure 1)?

Figure 1. Batumi, Georgia. Hotel construction in progress.

In the quest for an illustrious lineage, two distinct sides should be taken into account: on the one hand, the antiquity of the tradition that ennobles those who adopt it; on the other, the aristocratic character of the building or monument chosen. It would never occur to anyone to reproduce a troglodyte cave. This explains the nouveau riche's preference for Greece and Rome. Accordingly, a palace is better than a middle-class house. This is why the Château de Versailles remains one of the most popular models, possibly the most prestigious of all references. In between today's nouveau riche and Versailles, however, we find an interesting case of aristocratic architectural imitation due to a peripheral monarch, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, and realized in Herrenchiemsee in 1885. In his megalomania, Ludwig shared the same attraction for the noble and ancient as the opulent Roma, and like them, he will leave his little Versailles largely uninhabited. Russian emperors were also fascinated by Italian, French, and German models. Western architectural style would only spread to the Romanian provinces by the end of the 19th century, as cities and manor houses were mainly inspired by Byzantine and Ottoman models. I remember visiting a boyar's countryhouse in Oltenia that had been turned into a museum and in which those two styles were blended: of the two salons on the upper floor, one was “Turkish,” with carpets and cushions and large windows all around, while the other was “Viennese,” with a concert piano, tables, chairs, and wall hangings. This example could be extended to south-eastern Europe altogether. The Ottoman garden cities with walled houses were replaced by the Enlightenment model of geometric city plans, whose houses with numerous windows on the street announced the owner's worth (Reference RueggRuegg, 1991).

Display your wealth

The second message that these palaces deliver is that there is no limit to the amount of money that can be spent. The size of the property, the gates, the materials (marble), the decoration made up of statues, niches, and columns, the fanciful roofs, the annexes and their contents, luxury cars—everything points at this sole goal. The location of the palace can also play a critical role, which brings us back to urban anthropology.

The presence and meaning of political and ethnic symbols in Eastern European cities—saints or national heroes—is a well-studied topic in political anthropology. The erection and demolition of statues, the way they are revered, their strategic location in the city, and related commemorative parades are all prominent themes of post-socialist scholarship and literature. The Romanian city of Cluj, with its dual Hungarian and Romanian constituency and their respective symbolic meanings, is a classic case to illustrate such symbolic staging. Inversely, the equally symbolic installation of the new rich in the centre, in the historical districts, or in their new districts in the suburbs, remains underscrutinized in the multiculturalist and ethnicity-oriented temper of current research.

It was the intrusion of affluent Roma into the city of Timişoara that set off the fire. In recentyears, there have been protests in Timişoara against these Roma who “fraudulently” acquired a few buildings in a historic district, allegedly by forcing the residents to leave under threat, or by bribing the authorities. We can hardly understand these anti-Roma demonstrations if we do not keep in mind that their settlement in Timişoara contradicts the image of the poor, marginal Roma. The purchase of houses in the heart of the city and the construction of “palaces” by the Roma represented a crime of lese-majesty for many citizens in town; and this is just one example among many others. Yet someone did sell these properties, even under duress, and someone else did issue title deeds and/or building permits … This case highlights the imaginary landscape of the city and the imaginary interplay of its ethnic groups. The revolt is born out of this sense of lese-majesty, of what Mary Douglas described in Purity and Danger (Reference Douglas1966) as defilement—a sense that something is out of place. Ethnicity here becomes a secondary concern in relation to a social representation which ineluctably assigns the Roma a place at the edge of the city.

In countries where collectivization dismissed all individuality and transformed aristocratic residences and churches into hospitals and hospices, if not into sheds, little historical or scenic appeal is left to the countryside, except for monasteries and the few castle ruins that have survived. Only the city guarantees the necessary visibility and recognition, a spot on a main road, or a protected neighborhood, the opposite of a ghetto. The Roma, like other nouveau riche, follow this model.

Roma palaces or nouveau riche's homes?

In Romania, the appearance and multiplication of multi-storey, conspicuous individual houses that belong to the Roma nouveau riche, either in the cities or along main roads, soon made headlines. The term “Gypsy palaces” (Palatele ţiganeşti) was swiftly coined as a slur, and the media ruthlessly mocked these luxurious palaces, covered in marble, supported by golden columns, decorated with lions, and all sorts of opulent embellishments. Images of these palaces were posted on YouTube, along with critical comment threads. A scholarly volume containing a collection of photographs of these sumptuous residences was published in 2008 and included a sociological essay. Interestingly, the essay (Reference GräfGräf, 2008) was first published as a “working paper” in a series on minorities, suggesting it was obviously about an ethnic phenomenon. Yet things are not quite that simple. This is only one among other possible and more accurate explanations.

During a fiedwork in 2009 in the Republic of Moldova, we were able to photograph the Moldovan cousins, or rather uncles, of those palaces (Figure 2). In Soroca, where those photos were taken, the “tradition” went back well beyond the end of the Soviet regime. Similar-looking buildings, replicating historical styles and monuments, mainly empty or unfinished, were disseminated throughout the Roma quarter on the hill. According to our informants, those villas were built with the fortunes of the Roma who had accumulated gold during their peregrinations in the former Soviet world. Similar palaces are popping up in Bulgaria and other Balkan countries. Reference DelépineSamuel Delépine (2007), one of the few authors who published a study on Roma housing in Romania, refers to these palaces in passing, but the title of his book, Quartiers tsiganes, reflects his ethnic-oriented approach.

Figure 2. Soroca, Rep. Moldova. Roma palace imitating a historical monument.

A first glance reveals a great variety of styles. Some palaces in the west of Romania adopt a French style, with mansards and monumental staircases; others, in the same region, imitate early 20th century bourgeois architecture of Bucarest. In the eastern part of the country, the style of the new Roma houses depends on their religious affiliation, sometimes mistaken for their ethnicity. Turkish or Muslim Roma's houses are more reminiscent of India, commonly regarded as their original homeland. In the same city, Constanţa, Romanian, and Orthodox Roma follow a neo-bourgeois style, itself a mimic of the “national” neo-Byzantine intellectual architecture! In Moldova, one can find imitations of the Soviet and Mughal styles of Central Asia.

We are not trying to establish a typology of “Gypsy palace” styles; on the contrary, our goal is to challenge this narrow, ethnic-based definition. Let us broaden our perspective and consider the full set of these showy constructions, in town or not. In a residential area of Cluj, we found an example of a neo-classical “palace” belonging to a doctor and corresponding almost exactly to a “Gypsy” palace, perhaps less “flowery” (Figure 3). The Greco-Roman filiation, monumentality, decorative ornaments from the portico to the entablature, and even on the gates that enclose the property, everything tells us of a miniature replica of an ancient palace, meant to dignify the owner's ancestry and confer high social esteem on him. The famous Armenian palaces on the outskirts of Yerevan also deserve a mention. All the elements we have noted are amplified: historical references, extravagant building materials, pools, fountains ¼ The source of inspiration here is more to be found in Hollywood than in Athens (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Cluj. Neoclassical palace of a Romanian medical doctor.

Figure 4. Palace of an Armenian nouveau riche in the outskirts of Yerevan.

National and international orientation of cities in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet world

On the larger scale of urban development in post-socialist countries, two divergent yet concurrent trends can be observed: one is national or ethnic; the other is international or global. These trends are visible among the Roma in Romania and in the Republic of Moldova. One takes a neo-classical shape and emulates the pattern of Western art, as filtered by American TV series.

The other is national and ethnic: it may mimic the architecture of their nation, Romania, or in the case of the Moldovans the Soviet big brother, or it may refer to their mythical Indian or Mughal origins. Such symbolic references are not peculiar to the Roma, nor are they ethnic or exclusively contemporary phenomena either—quite the opposite. As we tried to show through a handful of examples, the quest for legitimacy by the nouveau riche and peripheral aristocracy often turns into an invented link to ancient and mythical origins: whether in the United States, in Russia, or in Europe, mimicking highly regarded styles and illustrious monuments is the most common means of achieving this goal.

A volume would be needed to study the development of the city of Batumi, in eastern Georgia, with its new buildings reminiscent of European capitals, a token of Georgia's desire to become closer to Europe, or even join the European Union. Apart from the reproduction of Place des Vosges and a number of statues alluding to the local attachment to ancient culture, one would also find Hollywood architectural patterns, just like the English hotel illustrated in Figure 1.

A brief look at a Central Asian city, Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, gives further substance to this mixture of national and global urban development. President Nazarbaev, who moved the capital from Almaty to the northern region of Akmola in 1997, can rightly be seen as an exemplary new rich, given the extent of his power and his intervention in the urban planning of the new city. Astana illustrates magnificently this two-fold desire for a monumental national identity and for joining the circle of prosperous nations.

The town planning and architecture admirably disclose the autocrat's approach to nation-building. A presidential boulevard traces an axis across the city that goes from the neo-Mughal presidential palace to the Khan Shatyr mall, a sort of gigantic yurt that has become one of the tourist attractions of the city, partly because of its air-conditioned sandy beach.

Midway, dominated by a golden sphere, stands the Bayterek tower. It merges popular tradition (it embodies a tree of life topped by a golden egg) with politics. Indeed, at the top of the tree, the golden egg enshrines a cast handprint of the president. Visitors can place their hand in the president's and make a wish. The symbolism brings together the traditional national and the affluent postmodern and international, with a clear dependence of the latter on the former. As for religious staging, other monuments could be mentioned, including a number of new mosques and the Pyramid of Peace and Accord, meant to embody the President's desire for peace and cultural diversity—but also the recent construction of the Russian-Orthodox Dormition cathedral, whose gleaming domes (Figure 5) pledge tolerance toward the former rulers. The new Opera House is as classical, or rather neo-classical, as the other concert halls are post-modern. The old opera house had a clear local taste, closer to St. Basil church in Moscow than to the San Carlo theatre in Naples. As a living museum of architecture, Astana also counts a number of gated communities where the nouveau riche is now retreating; less architecturally inspired, they are rather functional.

Figure 5. The Dormition cathedral in Astana.

Conclusion

By placing the Roma palaces in the broader context of urban transformations in the former communist countries, thanks to new access to money after the abolition of the “second World” borders, we renounce providing an exhaustive analysis. In our view, these palaces embody social movements of global reach that exceed ethnicity and nationality. Esthetically, they should be understood under the framework of politics of recognition, common to all those who achieve a new status, rather than as a purported “ethnic” or “social” bad taste. Here, we are aiming less at responses to psychological needs than at identity strategies that play a critical role in contexts of identity uncertainty and redefinition due to rootlessness and mobility (Reference RueggRuegg, 2009).

The analysis of these strategies avoids social and ethnic clichés in decoding the symbolic expressions of ideal-typical behaviors such as those of the new rich. President, manager, or doctor, Roma, Armenian, Romanian, or Kazakh, one has to spend one's new fortune in an ostentatious way by taking up the oldest and most illustrious examples. Imitation, as Gabriel Tarde argued, plays a key role. Along with recognition, revenge spirit is also part of the play, as for Roma hiring Romanians to build their palaces, or autocratic presidents making their Western democratic business partners grovel for a contract. The main profits are shared by architects, marble sellers, wrought iron fence manufacturers, and Mercedes dealers.