Cosmopolitanism had an image problem in the socialist world. Karl Marx, as is well known, was to blame. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels (Reference Marx and Engels1976, 6:488) wrote: “The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country.… And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature.” National literatures are withering away, to be replaced by a new cultural formation of global reach and concerns. The authors of the Manifesto are observers of a process that inevitably reshapes cultural production worldwide. And yet, the new cosmopolitan literature is intimately tied to the rise of the bourgeoisie and capitalism. The economic base, say Marx and Engels, determines its superstructure—in this case, the literature of the capitalist era. Its association with the bourgeoisie, its original sin, has tainted cosmopolitanism ever since.

How, then, did cosmopolitanism fare in the socialist world? It did not help that Stalin, in 1948, launched a vicious campaign against “rootless cosmopolitans.” The latter was chiffre, and decoded meant mostly Jewish intellectuals—the most outward-looking segment of the Russian intelligentsia. The campaign was intended “to eliminate ‘Jewish influence’ and to help a ‘native’ (i.e. non-Jewish) intelligentsia gain sway in the Soviet Union” (Azadovskii and Egorov Reference Azadovskii and Egorov2002, 69). The echoes of this last of Stalin's venomous political campaigns reverberated beyond the Soviet Union; it found ready emulators abroad, in the Soviet Union's allies in the expanding socialist world. His successors repudiated the excesses of Stalin's campaigns, and rehabilitated many of its victims. Cosmopolitanism itself, however, remained a toxic label throughout the socialist world, from central Europe to East Asia.

The fate of cosmopolitanism reveals a paradox. Marxism-Leninism, an ideology built upon internationalism, on the transcendence of “national one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness,” at once declared the arrival of a new brand of transnational culture, and yet showed profound unease over the all-embracing aspirations of this new literature and art. The socialist regimes from Prague to Pyongyang, from Beijing to Bucharest, set out to build a common culture that celebrated shared values, themes, and styles (see Volland Reference Volland2017). Yet at the same time, the newly empowered socialist and communist parties could not overcome their suspicion of the foreign, of influences that filtered in from outside the socialist state. Both the bourgeois origins of this global tide of cultural production and its carriers, the cosmopolitan intellectuals, rendered the worldliness in the cultural realm suspect. In a deeper sense, the paradox was grounded in the fact that socialist cultural production could be perceived only in universal terms. The very notion of a socialist culture presumes global links and flows. Hence, socialist literature in any given country is situated within a global network of writing and reading. The cosmopolitan is a fundamental condition of being, not just of modern culture in general, but of socialist culture in particular—in Europe as much as in the socialist nations of East Asia.

For Marx, the cosmopolitan is characterized by its transcendence of the national and the local, by rising above “one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness.” Little does the Manifesto say about the liberal humanism and globetrotting individualism of the cosmopolitan Weltbürger.Footnote 1 As a cultural expression, cosmopolitanism rather denotes the convergence of formerly isolated traditions into the “common property” of an emancipated humankind. Cosmopolitanism, in other words, becomes the fundamental framework for all cultural production, undergirding all creativity and imagination. This understanding differs decisively from conceptions of cosmopolitanism in the Kantian tradition that have enjoyed widespread currency and have only in the late twentieth century been challenged as parochial and Eurocentric (Cheah and Robbins Reference Cheah and Robbins1998). It privileges the result of the globalization of intellectual labor, world literature, over the habitus of its producers. It focuses on practice, rather than on mindset—as, in the words of Sheldon Pollock (Reference Pollock, Breckenridge, Pollock, Bhabha and Chakrabarty2002, 17), “something people do rather than something they declare, as practice rather than proposition (least of all, philosophical proposition).” The emergence, in recent years, of a critical conception of cosmopolitanism that brings vernacular practice back into focus as a site of cosmopolitan production, and a view of cosmopolitanism in the plural, as cosmopolitanisms (see Breckenridge et al. Reference Breckenridge, Pollock, Bhabha and Chakrabarty2002),Footnote 2 provides a vantage point to revisit Marx's proposition, and its implications for cultural production in the socialist world.

Paradoxically, the significance of cosmopolitanism emerges in sharpest relief in places and times of xenophobia, when public rhetoric denounces the foreign and attempts to deny it the last vestiges of legitimacy. Even in such situations, when socialism turned inward and shut itself off, when regimes ostensibly denounced the foreign and aimed to stem cultural flows across their borders, the cosmopolitan did not die off. Rather than withering, it warped and appeared in new disguise. Cosmopolitanism went clandestine. It cannot simply melt into air, as it is tied inextricably to socialist culture itself, and hence it goes underground. From there, it continues to shape attitudes and practices, providing the framework in which culture is conceived and defined. This is what happened in Stalin's Soviet Union in the 1930s. “Paradoxically,” Katerina Clark (Reference Clark2011, 16) observes, “even as the Soviet Union became an increasingly closed society, it simultaneously became more involved with foreign trends” which, as Clark argues, were of crucial importance to legitimize the grandiose experiments—social as well as cultural—promoted by Stalin. Foreign visitors were brought to Moscow, an extensive bureaucracy was created to deal with cultural exchange, and massive amounts of foreign literature were translated and published in the Soviet Union.

In a very different yet no less instructive manner, the People's Republic of China (PRC) found itself unable to cut the ties to the world beyond its borders, even as Mao's sociopolitical experiments catapulted the nation into mass campaigns that explicitly rejected foreign models in all realms of life. Socialist China, as Joseph Levenson (Reference Levenson1971, 1) has argued, inherited the cosmopolitanism of the May Fourth era, when revolutionary “new intellectuals” sought to reclaim the universalism that had gone lost together with the Confucian worldview: “against the world to join the world, against their past to keep it theirs, but past.” In the late 1950s, after a decade of intense interaction and exchange with the socialist world, the Maoist PRC began to redefine its transnational cultural networks, and eventually embarked on a path of self-sufficiency and isolationism that led to the Cultural Revolution (conventionally dated 1966–76).Footnote 3 “Communist cosmopolitanism” was thus recast as “bourgeois cosmopolitanism.”Footnote 4 Yet even during this period of “High Maoism,” the PRC would not and could not erase the traces of a fundamentally cosmopolitan outlook.Footnote 5 The two decades before the launch of Deng Xiaoping's “reform and opening” program in 1978 have been described as xenophobic and hostile to things foreign, most notably so by the supporters of Deng's “New Deal,” a characterization that has been gladly embraced abroad.Footnote 6 Studies of Chinese socialist literature from the 1950s, and even more so from the 1960s and 1970s, have lamented the “break” with the urbane, ostensibly outward-looking literature from the Republican era.Footnote 7 Convenient judgments like these, however, take the socialist critique of cosmopolitanism at face value. They overlook the other side of the paradoxical nature of cosmopolitanism.

This article examines the circulation and, to a degree, the consumption of foreign literature in socialist China under High Maoism.Footnote 8 On the following pages, I will explore the modes and channels through which cultural production from Europe and the United States, and from Japan and the Soviet Union, reached Chinese readers from the late 1950s through the 1970s. Access to foreign literature during this period was neither complete nor universal: availability of foreign authors was always selective, and often highly so. And access was often restricted, sometimes to highly circumscribed groups (though never as narrow as the official definitions stated). But, degrees of availability of and access to foreign literature existed throughout this period. The flow of foreign cultural production into China may have shrunk to a trickle, and much of it moved underground, but at no point did it dry up entirely. It could not. The cosmopolitan, at once hailed and condemned by Marx and his twentieth-century followers, provided the underlying framework of global socialist culture, in which the People's Republic—just like the other socialist nations in East Asia and Europe—viewed its own culture. As Marx had put it, “national one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness” were no longer an option.

In what follows, I will detail three distinct modes of circulation, through which Chinese readers (at least some of them, at least at certain times) gained access to foreign literature, and through which foreign literature came to play a role in socialist China: the narrowly defined sphere of private reading; the “restricted public sphere” of books and journals published for internal (neibu 内部) circulation; and publications in the realm of the “open public sphere,” that is, for open circulation and consumption. Through what means and channels did foreign literature circulate in the PRC? Which works and authors reached Chinese audiences, and what criteria of selection applied? What motivated readers, translators, and editors alike to seek out foreign literature, and how did they justify doing so? The sections below scrutinize the inner logic and the functioning of these three distinct but overlapping modes, and demonstrate how they worked to perpetuate an understanding of literature and culture that was fundamentally cosmopolitan in nature.

The Private Sphere

The solitary nature of literary consumption made it circumspect in the eyes of the socialist state. The “making of the state reader” therefore represents an effort on behalf of the socialist state to rein in the autonomy of the reader, to channel the practice of reading, and to transpose it from the private into the public realm. “The Soviet reader,” as Evgeny Dobrenko (Reference Dobrenko and Savage1997, 2) points out, “can be regarded as one of the aspects of a larger process—the shaping of the Soviet man.” The symbolic significance of this shift in the economy of reading was not lost on the cultural planners of socialist China: Reading groups and study sessions; classrooms; and wall newspapers where texts of all sorts, from newspaper editorials to short stories and Mao's old-style poetry, were studied and discussed under the eyes of the public bear witness to the effort to make reading a collective and communal, rather than private, experience. Utopian as these projects were, however, they never replaced private forms of reading. Indeed, private reading remained the primary means of literary consumption throughout the socialist world: beyond the watchful gaze of the state, its capacity to preselect texts, prescribe interpretations, or preempt alternative decodings and responses. Ironically, the official promotion of collective reading in fact drove readers, in China and elsewhere, ever deeper into the confines of their privacy. Throughout the most turbulent and violent episodes of the PRC's history, private reading thus remained the preeminent mode of cultural consumption. Private forms of reading, which as a rule perpetuated patterns shaped in previous years and decades, allowed individual readers across China to interact with foreign literature.

The significance of private reading patterns, above or underground, has been noted by both Chinese readers (in fact mostly readers-turned-writers) and foreign observers. The poet Bei Dao 北島 (Reference Dao, Larson and Wedell-Wedellsborg1993, 63–64), one of the pioneers of the modernist resurgence in the late 1970s, has commented on the importance of private consumption of foreign literature during the Cultural Revolution for the new wave of experimental writing. Perry Link (Reference Link, Link, Madsen and Pickowicz1989) has studied the evolution of reading networks centered around hand-copied volumes that made available literature—both entertainment fiction and more serious works—to readers across the Chinese countryside during the Cultural Revolution. And in two recent studies, based on oral history accounts, Barbara Mittler (Reference Mittler2012, 18–21; Reference Mittler2013, 178–79, 189, 194) has found ample evidence of diverse reading patterns; many of Mittler's cultural revolutionaries were voracious readers, devouring everything they could lay their hands on.

The forms of reading described in these accounts comprise the most clandestine way of consuming foreign literature, and thus cosmopolitan practice in a highly constrained environment. The examples quoted most often refer to the underground circulation of books at the height of the Cultural Revolution. During the Red Guard movement, libraries across the country closed their doors, at least for large parts of the populace. Yet the Red Guards, responsible for these closures as they wrested power into their own hands, themselves had continued access to these libraries, and often to those parts of the libraries’ collections they had been barred from before.Footnote 9 As many former Red Guards have reported, the upheaval provided them with both the power and the leisure time to read extensively: “…we read all kinds of things that were fengzixiu [封資修; feudal, capitalist, and revisionist, i.e., premodern literature and those from the capitalist nations and the Soviet Union] anyway, Balzac and Romain Rolland! At the time, I was looking after an ox [i.e., someone held in a makeshift prison, or ox pen], reading all the while, I thought this was quite fun.” “During the Cultural Revolution I read more books than ever before. I would get them from friends: all literary classics, translated from French and German…” (quoted from Mittler Reference Mittler2013, 190; compare also the voices quoted in J. Li Reference Li2015, 122–29). From guardians of proletarian purity, the Red Guards turned ravenous readers. And foreign literary classics invariably top the lists of these Red Guard readers.

These patterns of underground reading persisted after the end of the Red Guard movement, in the summer of 1968, when millions of educated young people were sent to the countryside, to “learn from workers and peasants.” More often than not, the rusticated youth found more interesting teachers and guides in the books they brought with them, openly or smuggled, to their mountain and village destinations (Song Reference Song2007, 329). The thriving backyard industry of hand-copied fiction that circulated in the late 1960s and 1970s is well documented (Link Reference Link, Link, Madsen and Pickowicz1989). Copying, often in groups and networks, helped to deal with scarcity. The objects of these efforts ranged from entertainment fiction to foreign classics. Dai Sijie, a former Red Guard who spent three years in the countryside in Sichuan, has produced an intricate fictional account of the circulation of classic French realism, in which two urban youth read Balzac's novels to an uneducated village girl, the daughter of a local tailor (Dai Reference Sijie2000). As I show below, Balzac had once been a model of critical realism, courtesy of Engels, but had been attacked by Chinese critics as early as 1960. A decade later, he was turned once again into a role model in the Chinese countryside, casting his spell even on illiterate “readers” like Dai's little seamstress.

The circulation and reproduction of foreign books in the Cultural Revolution underground raises the question of access. Publishers no longer printed these books, and no bookstores sold them. Libraries, though shut, remained a crucial source of books for those with access (which often needed not more than a broken window).Footnote 10 Another important source of books was private collections. Readers who had acquired such books when they were openly available—in the 1960s, the 1950s, or the 1940s, depending on the nature of these books—could and did still read the copies in their possession. Stories abound of frightened owners burning their prized collections at the onset of the Cultural Revolution, or watching Red Guards incinerating them. The impact of these raids is hard to quantify. The fact that many editions in the 1950s were produced in huge print runs, and that these editions sell for very low prices on secondhand markets today, suggests that very significant numbers of copies have survived the Cultural Revolution, and that reports of book burnings may have primarily symbolic value (as is the case elsewhere). The publication of books (or lack thereof) at any given time, thus, does not equal the availability of books.

This is true for public collections as well. At least until the eve of the Cultural Revolution, libraries presented a crucial avenue of access to books. Libraries, by definition, build collections of lasting value, and make them available to the public for the long term. This presents an obvious problem for anyone attempting to restrict access to books for private consumption. Publishers can be ordered to cease printing new editions of authors who have come under a cloud. It is much more difficult to prevent the private consumption of those copies that have found their way into library holdings.Footnote 11 Large public lending libraries were exceedingly scarce before the founding of the PRC. After 1949, however, the PRC followed models provided by the Soviet Union and other socialist nations, and vastly expanded libraries at the provincial, municipal, and even county level.Footnote 12 More importantly, the socialist state encouraged small-scale libraries and reading rooms in enterprises and work units of all kinds. During the Great Leap Forward (1958–60), in particular, the number of reading rooms in Chinese work units jumped significantly. Once these grassroots libraries had been stacked with books, these volumes usually stayed on their shelves, and were available to readers. After the Sino-Soviet split in 1960, the flood of Soviet literature in Chinese translation slowed to a trickle, and many works were no longer reprinted—even classic authors of socialist realism such as Mikhail Sholokhov were now labeled “reactionary.” To pull all copies of Sholokhov's Virgin Soil Upturned and The Quiet Don from tens of thousands of libraries and reading rooms, however, was logistically next to impossible. Both books had sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and many of these copies stayed on the shelves. Circulation cards that have survived in some library copies give concrete evidence that the Balzac translations of Fu Lei 傅雷, for example, which were no longer reprinted after 1963, remained available for private consumption and in fact were in heavy demand until virtually the eve of the Cultural Revolution, and again after 1972 (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Library circulation card for Balzac's Père Goriot (Ch. Gao laotou 高老頭, trans. Fu Lei).

Literary journals kept in private and public collections presented an even bigger challenge to anyone trying to limit access to foreign literature. Jean-Paul Sartre's La putain respectueuse (The respectful prostitute) had been published in the November 1955 issue of Yiwen 譯文 (Translation), shortly after the author's visit to the PRC, where he was celebrated as a “progressive foreign writer.” When Sartre joined two dozen other French writers, many of them left-leaning, to condemn the November 1956 Soviet military intervention in Hungary, Yiwen printed a terse note, reporting Soviet rebuttals of the protest. Yiwen never again translated any of Sartre's works. La putain respectueuse, however, was there for anyone who cared to consult the 1955 volume of Yiwen: it was impossible to pull the entire volume from thousands of libraries and reading rooms. The same is true for periodicals in general, where much of the most recent and most influential foreign literature was published in the 1950s and 1960s.

Libraries large and small thus remained a crucial avenue of access to foreign literature for innumerable Chinese readers, complementing carefully curated private collections. After the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, libraries closed, but their collections began circulating through other channels, fueling private modes of cultural consumption. The reminiscences of the Cultural Revolution quoted earlier in this section make clear that foreign literature was at the core of the underground reading movement. Cosmopolitan reading practices, in other words, were as central to cultural consumption in the 1960s and 1970s as they had been to readers in earlier decades. Chinese readers in the era of High Maoism continued to believe that these works were important to them, and many of them found ways and means to gain access to them.

The Restricted Public Sphere

Foreign literature remained accessible in China during the period of High Maoism beyond the sphere of private reading. A vast amount of translations—both reprints and new renderings—circulated in editions designated as restricted to certain segments of the readership, broadly known as neibu editions or popularly as hui/huang pishu 灰/黃皮書 (gray/yellow cover books, called so because of the uniform book covers) (see Iovene Reference Iovene2014, 73–76; Link Reference Link2000, 183–86; Shen Reference Zhanyun 沈展雲2007, 1–22). The exact designation of these editions varies, and so does their degree of (in)accessibility. Internal editions existed from the 1950s through the 1980s in all areas of publishing. Access was usually restricted to readers with privileges, such as those in work units related to press and propaganda, scientific personnel, or ranking party cadres—readers, that is, with specialized training or higher political consciousness who were supposedly immune to the corrupting influences these works contained. Such readers could access special sections in libraries storing neibu editions, or had cards entitling them to purchase neibu editions from bookstores. The exact distribution key might be more or less narrow, and was occasionally stated in the publications themselves (see Link Reference Link2000, 183–86). The realm of limited-access publications created a sphere of privileged readers, a “restricted public,” narrower than the population at large, yet clearly not private either.

The amount of neibu books published in the PRC is staggering. A catalogue of neibu editions (Zhongguo banben tushuguan 1988), itself designated an internal publication, lists over 18,000 books published internally between 1949 and 1986. The largest category, with 4,400 titles, is industry and technology, followed by history and geography and politics and law. The category “literature” (wenxue 文學) contains 900 titles, about a third of which are translations of foreign literary works. In the period of High Maoism, various Chinese publishers issued ninety-nine translations of Soviet works, nineteen translations of American books, and twenty of Japanese literature.

The number of internal editions of Soviet literature increased in direct proportion to the decline of Sino-Soviet relations. Ilya Ehrenburg (1891–1967) had been widely read in the PRC in the 1950s and was influential as both a novelist and a literary critic. His autobiography People, years, and life (Lyudi, gody, zhizn; Ch. Ren, suiyue, shenghuo 人,歲月,生活), published after the Sino-Soviet split, was issued in a neibu edition. Four volumes appeared between 1962 and 1964, just about a year after the publication of the Russian originals. The full edition of six volumes was published in 1979 and 1980 (still neibu). Readers in the restricted public sphere were also treated to some of the latest and most controversial Soviet literature, such as the works of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich had caused a sensation in Soviet letters after its publication in 1962, as did Solzhenitsyn's short stories. The Chinese translation of One Day appeared in 1963, followed by a collection of short stories in 1964. And even during the Cultural Revolution, Soviet literature remained a staple of the restricted public sphere. Sholokhov's popular They Fought for their Country, for instance, first published openly in 1947, was reprinted in 1973. The CCP had denounced Soviet cultural policies since 1960, and authors such as Solzhenitsyn were anathema to the Maoist Left, but they were considered important enough to warrant translation nonetheless, keeping at least the privileged Chinese reader informed about the latest foreign trends.

Apart from Soviet works, a steady stream of literature from other nations reached readers in the restricted public sphere. J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye appeared in a neibu edition in 1963. In 1974, Chinese translators produced a rendition of Eudora Welty's The Optimist's Daughter, which had just won the Pulitzer Prize. Most remarkable (and remarked upon in reminiscences; see also Iovene Reference Iovene2014, 75–76) is a translation of Jack Kerouac's On the Road. The iconic work of beat generation culture appeared in Chinese in December 1962, just weeks after Mao had reminded his compatriots to “never forget class struggle.” Equally surprising appears the publication, from 1971 to 1973, of the full four volumes of Yukio Mishima's 三島由紀夫 Sea of Fertility tetralogy. Mishima was a radical right-wing author who had been despised by Japanese Leftists and who had committed ritual suicide in 1970, after a failed coup d’état. That publishers during the High Maoist era saw it fit to issue works such as those of Mishima and Kerouac demonstrates that the restricted public sphere very often acted completely out of lockstep with the political and ideological logic undergirding the open public sphere.Footnote 13

The catalogue of internal publications is helpful in providing a sense of the scope and the logic of publishing for restricted audiences. Yet despite its size and coverage, the catalogue is far from complete; many more neibu books circulated in the PRC. Around 1960, for instance, the editors of the journal Shijie wenxue 世界文學 (World literature) translated The foothold (Pyad’ zemli; Ch. Yi cun tu 一寸土), a controversial novel by Grigory Baklanov (1923–2009) (Baklanov, Reference Baklanovn.d.). Shijie wenxue, until late 1958 known as Yiwen, was the foremost publication dedicated to translated literature, and one of the most widely read Chinese journals in the 1950s and 1960s. Besides the openly distributed Shijie wenxue, the journal's editors produced a steady stream of internal publications (see also Iovene Reference Iovene2014, 72–73). Baklanov's The foothold had originally been serialized in Novyi mir in May and June 1959, and had triggered heated debates in the Soviet press about the proper way to depict the Great Patriotic War and the soldiers of the Red Army. Chinese critics joined those of their Soviet peers who condemned the humanistic depiction of an army platoon in the last days of the war, with its sympathetic displays of fear, homesickness, and cowardice.Footnote 14 Several articles, translated from the Soviet press, appeared in Shijie wenxue,Footnote 15 but the translation of the full novel was circulated in a restricted edition only. It appeared as the fourth volume of the World Literature Reference Material Series (Shije wenxue cankao ziliao congshu 世界文學參考資料叢書). In a brief introduction, the (unnamed) translators summarize the main positions in the controversy in the Soviet Union and write: “The debates provoked by this work are matters of principle and therefore meaningful.… We are now translating this novel for your reference.” The foothold was not openly published in China until 1986.

By translating works such as Baklanov's The foothold, the editors of Shijie wenxue made available material from authors who had been attacked in the open press, and that was apparently considered unsuitable for open distribution by the journal's backers in the central government and the CCP. Yet the restrictions placed upon the books’ circulation did not make them irrelevant as such. To the contrary: It is striking that the editors felt it justified to invest the time and energy to translate a controversial 200-page novel within a year or two of its publication in the Soviet Union. Or that they considered Ehrenburg's insights and opinions—a volume of whose essays was published in the same series—to be relevant for cultural production in the PRC even after current Soviet views on literature and arts had been officially repudiated by leading Chinese critics and policy makers. This demonstrates that foreign literature and literary developments remained a crucial benchmark, indicating the larger framework within which Chinese literature imagined itself. The framework was implicit, hidden from view by external markers such as the labels “For internal reference, keep under covers” (neibao cankao, zhuyi baocun 内部參考,,注意保存) and “Internal reading material” (neibu duwu 内部讀物) that graced the covers—in bold print—of The foothold and Ehrenburg's essays, respectively. And yet, the framework was needed, sought after by readers and publishers alike. Paradoxically, just as the PRC's official cultural policies sought to distance the nation from its erstwhile points of reference (such as the Soviet Union and the United States), the number of editions for restricted circulation that turned to precisely these points of reference surged.Footnote 16

Books represent only a portion of the materials issued for restricted audiences. A number of periodicals offered privileged readers access to a wide sway of up-to-date information on cultural developments abroad—from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to the United States, Japan, and Latin America. A case in point is Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao 世界文學參考資料 (World literature reference material), a journal with irregular frequency issued by the editors of Shijie wenxue—in many ways a supplement to the latter that provided a broader context for the works translated there. The journal, founded in 1959 and edited by Chen Bingyi 陳冰夷, the editor-in-chief of Shijie wenxue, is not listed in the catalogue of neibu books discussed above.Footnote 17 Journals in general were an important conduit for fast-traveling information and trends, and neibu journals could be more important than books published for restricted audiences. Periodicals such as Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao provided its readers with a broad range of information that rarely if ever reached the open press (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Cover of Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao (World literature reference material).

Issue 30, for instance (dated March 28, 1959), contains two dozen mostly short, informative pieces on recent literary developments abroad. Three articles deal with the publication of Pearl S. Buck's exchanges with the Philippines’ ambassador to the United States, Carlos P. Romulo, titled Friend to Friend; the book's reception in the American press; and an announcement (quoting the New York Times of January 22, 1959) of her upcoming work Command the Morning. Buck's The Good Earth was publicly denounced—on the pages of Shijie wenxue no less—as a reactionary work that “distorts the actual conditions of class struggle in the Chinese countryside” (Li Wenjun Reference Wenjun1960, 115), but the publication of a major new book by an author as intimately familiar with China as Buck was apparently newsworthy. Another brief article reported on the commercial success of Lolita in the United States, noting that “the frenzied reaction to Lolita in the capitalist countries demonstrates how corrupt and perverse their societies are” (Liu Ailian Reference Ailian1959, 21). To ensure that Chinese readers (those with access to the journal, that is) were well acquainted with the “shameless” émigré landlord Nabokov, the editors also translated a brief, factual entry from Stanley Kunitz's Twentieth Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature. Three articles dealt with the Leftist British-Chinese author Han Suyin (1916–2012), including a brief biographical essay excerpted from the New York–based Saturday Review, a press article reporting her criticism of the US government's refusal to recognize the PRC, and a review of her bestselling novel The Mountain Is Young, also excerpted from Saturday Review. The longest section of the issue is devoted to Boris Pasternak, who had been awarded the Nobel Prize five months earlier. Six articles reported on Pablo Neruda's criticism of Pasternak, his invitations to England and the United States, the author's defense of Doctor Zhivago, and an attack by a Swedish Communist writer. By far the longest piece in the issue, at eighteen pages, is a detailed plot summary of Doctor Zhivago that quotes copiously from the novel, translating key passages such as Zhivago's final encounter with Strelnikov in Varykino. Attacks on Nabokov were published in the openly circulating Shijie wenxue, but only the readers of the journal's internal edition got to read excerpts from the novel. Elite readers with access to the restricted public sphere, the editors apparently felt, should keep abreast of major literary developments abroad.

Similar journals existed at various times during the High Maoist period. In November 1973, Shanghai renmin chubanshe 上海人民出版社 began publishing a new journal, Zhaiyi 摘譯 (Digest of translations). At the height of the Cultural Revolution, the only functioning literary journal issued publicly in the PRC had been Chinese Literature, an English-language periodical ostensibly targeting a foreign audience. In a brief foreword, the editors explained:

Zhaiyi mainly introduces literary affairs from the Soviet Union, the United States, and Japan, is published without a fixed schedule, and is provided to related work units for research and criticism. The material [in this journal] has been directly translated from Soviet, American, and Japanese books, newspapers, and journals. The sources are generally provided. If you would like to refer to it in open publications please consult the original. (Zhaiyi bianyizu 1973)

Zhaiyi was designated “for internal circulation” (neibu faxing 内部發行) in the colophon and “internal material” (neibu ziliao 内部資料) on the cover (see figure 3). Zhaiyi averaged about 180 pages, and sold for anywhere from 34 to 58 cents an issue, depending on the number of pages. In the colophon, Zhaiyi lists a print run of 15,000 copies.Footnote 18 That is a very remarkable figure, raising questions about just how many people qualified as engaged in “research and criticism”—or rather, who may not qualify for inclusion in the journal's distribution key.

Figure 3. Cover of Zhaiyi (Digest of translations).

Zhaiyi closely followed the latest cultural trends in the Soviet Union, the United States, and Japan, the countries identified as the primary reference points for the PRC (at least in the restricted public sphere). Zhaiyi translated short stories and summarized novels, often within two or three months of their appearance in major foreign magazines. The journal covered a remarkably wide spectrum of literature. Most of the February 1975 issue, for instance, was given over to summaries of two science fiction novels, Aleksandr Kazantsev's (1906–2002) Stronger than time (Silneye vremeni; Ch. Bi shijian geng you li 比時間更有力), and Allan Drury's Come Nineveh, Come Tyre. Both novels “attempt to predict the future,” and “we can see from them how the two superpowers imagine the future” (Fan Reference Yiping1975, 1). The “summary” of Drury's novel (which is in fact a sequel to his Preserve and Protect) runs to almost 100 pages, a fifth of the original. What may have endeared Come Nineveh, Come Tyre to its translators (the “Foreign Literature Criticism Group of the Foreign Language Department at Fudan University”) may be that the book describes how the Russians and Chinese outwit a weak and feeble American president and achieve world dominance.

Apart from prose literature, Zhaiyi occasionally carried full-length translations of theater scripts, and showed a deep and sustained interest in cinema. Eighty percent of the space in the journal's inaugural issue, for instance, was taken up by the translation of the film script Courtesy visit (Vizit vezhlivosti; Ch. Lijiexing de fangwen 禮節性的訪問) by Anatolii Grebnev (1923–2002). The editors paid close attention to world cinema in later issues too. In January 1974, readers encountered a twenty-three-page synopsis of The Godfather (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1972), a film that “objectively reflects the corrupt and dark social reality of America” (93), followed by a number of brief excerpts from film reviews published in magazines such as Saturday Review, Life, Time, and The Atlantic Monthly. To drive home the significance of the film, the editors noted that The Godfather had won three Academy Awards, and that critics had compared it with Gone with the Wind. Notably, neither of these two benchmarks—the Oscars and Victor Fleming's epic romance—warranted so much as an explanation. Zhaiyi’s editors apparently assumed that their audience was sufficiently familiar with these staples of American popular culture. In actuality, however, it is precisely this matter-of-fact treatment of the Academy Awards and Gone with the Wind that raised the stakes for their readers, suggesting that someone not familiar with such “common knowledge” should be: Zhaiyi in fact all but endorses an implicit canon of trans(pop)cultural literacy. Never mind that, at the very moment Zhaiyi treated its readers to The Godfather, the Cultural Revolution was going through yet another radical phase, and the official newspapers exhorted the masses to “Criticize Lin Biao and Confucius” (Pi Lin pi Kong 批林批孔).

What the publication of Soviet science fiction and American movie scripts, as well as the assumed literacy of the journal's readers in foreign popular culture, suggests is that the selection criteria of Zhaiyi—and other neibu publications—operated independently from the official cultural policies. The restricted public sphere functioned according to a logic distinct from the ideological prescriptions governing the open public sphere. The fare presented to its supposedly “specialist” audience was highly selective,Footnote 19 to be sure, but the thresholds of selection were located not within Maoist China, but in the world beyond its borders: Neibu journals translated not (or not primarily) what suited the current policies or line in the PRC, but what was new, notable, or influential abroad. More precisely, the importance of these translations for their Chinese audience lay in the fact that they were important elsewhere—in the United States, the Soviet Union, or Japan. The intellectual framework giving guidance to privileged and specialized readers in Maoist China was itself transnational in nature.

The restricted public sphere was exclusive by definition. Just how exclusive, however, is open to question. The borders between the private, the restricted, and the open public sphere turned out to be porous, if not fluid.Footnote 20 Memoir literature suggests that neibu material was routinely shared with family members, friends, or colleagues, and thus circulated far outside the official distribution key. The son of Guo Moruo 郭沫若 (the president of the Academy of Sciences), for instance, recalls using his father's purchasing card to buy neibu books in the early 1960s, which he then shared with members of the “X Poetry Society” (Shen Reference Zhanyun 沈展雲2007, 12–13).Footnote 21 The poet Bei Dao makes access to this material responsible for a “quiet revolution” that paved the way for the modernist revival in the late 1970s (Bei Reference Dao, Larson and Wedell-Wedellsborg1993, 63). In oral history interviews, Barbara Mittler has found ample evidence for the wide circulation of such books during the Cultural Revolution, opening up “hitherto unknown avenues of cultural experience” (Mittler Reference Mittler2013, 194). Whether these forms of reading were really “hitherto unknown” is doubtful, however. As I will show below, they were arguably a perpetuation of patterns well-established before the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 22 With access to this material also came the awareness of the broader cosmopolitan context of contemporary Chinese cultural production.

As if to affirm how porous the borders segregating the open and the restricted were, the journals discussed in this section provide internal evidence of the difficulty (in fact, the impossibility) of policing the borders of circulation for translations of foreign literature. In its January 1976 issue, Zhaiyi responded to a reader's letter, clarifying its editors’ intentions and the journal's scope. The letter's author had complained that he and his friends, all avid readers of Zhaiyi, found that much of the journal's contents, “especially Soviet revisionist works,” “are aesthetically crude, some of them in fact just unreadable” (Zhaiyi [waiguo wenyi] bianyizu 1976, 171). The author and his friends hoped to read “foreign literary works that would open our eyes and from which we could also borrow aesthetically,” and thus asked the editors to translate more “representative works from the Soviet Union, America, and Japan.” In their reply, Zhaiyi’s editors pointed out, “that you and your friends feel dissatisfied with the contents of Zhaiyi is because your demands differ from the task of Zhaiyi” (172). Their journal, the editors explain, was published primarily to expose the ideological, political, and economic conditions of the imperialist and revisionist countries through the means of literature and art. “And it should be mentioned: Reading for its own sake, or just for ‘appreciation,’ rather than for criticism and study, is mistaken.” Yet it seems to be precisely these mistaken (bu dui de 不對的) forms of reading that were widespread among Zhaiyi’s readers—the editors admitted that much when they told the author of the letter that “the problems raised in your letter are fairly common among our readers” (171). Zhaiyi and similar publications offered a window to the world to Chinese readers who tried to keep abreast of developments abroad and found that “representative works” from countries such as the Soviet Union and the United States provided crucial input that could be “borrowed” by cultural production in China itself.

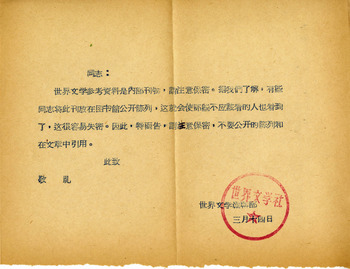

It is unlikely that Zhaiyi’s explanation of its “task” (renwu 任務) accomplished its goal. And it remains doubtful if the exhortation to “related work units and comrades … to safeguard Zhaiyi” (173), buried in the second to last paragraph of the reply, was much more successful. To keep materials designated for internal distribution out of the public realm was a perennial issue. Two decades earlier, the editors of Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao had faced the same problem. Between the pages of issue 36, they had slipped a mimeographed notice to the journal's subscribers, signed and carrying the red seal of the journal's editorial offices (see figure 4). The notice reads in full:

Comrade: Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao is an internal [neibu] publication; please keep it secret. We have learned that some comrades have placed this publication on open shelves in the library, so that those people who should not see it may have access to it; in this way secrets may be easily given away. We thus explicitly ask you to take care to safeguard secrecy, and not to display [this journal] openly or quote [it] in writing. With regards, Shijie wenxue editorial department—March 14.

Figure 4. Notice of Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao editors to readers.

Consequently, the journal's next issue added the words “please don't display openly” (qing wu gongkai chenlie 請勿公開陳列) to the prompt of the cover, which until then had simply read, “Internal publication, keep under covers” (Neibu kanwu, zhuyi baocun 内部刊物,注意保存) (see figure 2 above).

The efficacy of the notice needs to be doubted. The fact that the slip remained neatly in place, between the pages of the journal, fifty years after it was placed there, suggests that the librarians who should have taken notice never even saw it—or did not care much about its content. That the editors of Shijie wenxue cankao ziliao felt it necessary to remind its subscribers of the journal's restricted nature points to a real and obviously widespread problem: that any number of libraries and reading rooms apparently did not bother to lock away neibu publications, but rather made them openly available to whoever cared to read them. The eighteen-page plot summary of Doctor Zhivago, with its extensive quotations, certainly reached a much wider audience than intended—and so did The Catcher in the Rye, and Kerouac's On the Road. The problem, and the fact that the editors of Zhaiyi still struggled with it, twenty years later, underlines that the existence of an extensive restricted public sphere in the era of High Maoism made access to foreign literary production inconvenient, but not impossible, for considerable numbers of readers.

The Open Public Sphere

Foreign literary works also circulated openly, highlighting the cosmopolitan roots of Maoist China. The leeway for the publication, dissemination, and circulation of foreign literature in the open public sphere was clearly much narrower than that in the restricted public sphere and in the private sphere. In addition—and in contrast to the restricted public sphere—the open public sphere was subject to quickly shifting constraints that fluctuated in close correlation with political and ideological developments.Footnote 23 In the face of these restrictions, it is remarkable to what degree foreign literature and culture remained a presence in the Chinese public sphere, serving as implicit reference points, an index to conceptualize and contextualize Chinese cultural production. In the eyes of both readers—who actively sought access to foreign literature—and those who translated and published these works, cultural imports from abroad retained their centrality for cultural consumption in China.

Foreign literary works, and information about cultural developments outside the PRC, circulated in two fundamentally different modes: the affirmative and the negative. The two modes exhibit internal logics that are diametrically opposed yet mutually complementary. While each existed independent from the other, they reinforced each other and hence helped to construct a literary universe that placed the revolutionary PRC within a global, and in fact universal, framework of cultural production and consumption. The affirmative mode aimed at explaining and justifying why certain works were not just acceptable, but meaningful and valuable within the Chinese public sphere; why it should be desirable that the reading public is acquainted with such works; and how cultural producers in the PRC can gain insights and thus benefit from these cultural imports. The negative mode hinges on critiquing foreign literary works, on exposing their pernicious influence and mistaken views, in order to serve as “negative instructional material” (fanmian jiaocai 反面教材) that is supposed to show the public the superiority of the socialist system and its splendid culture, but also teach readers to avoid the pitfalls of mistaken behavior that would inevitably harm the socialist state (compare Mittler Reference Mittler2013, 197–98). Both modes require active intervention from the publishers of these works, as well as strategies to frame them and fix their meaning. The success of these strategies, however, is impossible to measure with precision. In effect, the works, once let loose into the public sphere, were open to appropriation by readers who could chose to accept or reject, or simply to ignore, the barrage of prescriptive prefaces, editorial notes, and interpretive critical articles designed to fix their meaning; in other words, to free these works from their instructional scaffolding and recontextualize them as they themselves saw fit.

What I call the affirmative mode of framing is largely self-explanatory. Newspapers, literary journals, and publishing houses since the 1950s relied on an extensive array of paratextual devices, in addition to more lengthy and systematic discourses, to establish legitimacy for works that might appear vulnerable ideologically. In the 1950s, the classics of socialist realism from the Soviet Union needed no justification, whereas works from the new people's democracies of Eastern Europe, which were now also introduced to China, did. Journals and newspapers running such translations routinely added editorial prefaces or translator's notes that framed works by unknown or little-known authors within the accepted parameters of cultural production, most importantly those provided by the Soviet Union. The journal Yiwen, for instance, added brief postscripts (houji 後記) to its translations that provided factual and philological information but also, and more importantly, commented on the reception of these works in their home countries and abroad, especially the Soviet Union. In addition, Yiwen routinely translated critical essays by leading Soviet literary critics or academics who commented on the works and their authors, speaking from the vantage point of authority. Such essays were usually published together with the translations; they suggested that what was ideologically justifiable in the Soviet Union was also justifiable in China, at least until the late 1950s.

The Soviet Union as a source of legitimation disappeared after the Sino-Soviet split of 1960, but the practice itself remained in place. Chinese critics consequently took the place of their Soviet peers in journals such as Shijie wenxue, and penned prefaces, critical essays, and other framing devices for translated literary works in need of explanation—be it new works of Soviet literature (some of which still appeared openly in the early 1960s), works from the newly independent nations of the Afro-Asian world, or the occasional piece of Leftist literature from France or the United States. Western classics were a special category. The works of Shakespeare, Rabelais, or Balzac needed explanations of their meaning and value to make their open circulation possible in an increasingly hostile political climate. The case of Balzac is illustrative. A leading representative of the realist tradition, he was relatively easy to incorporate into a newly reconstructed canon of world literature that led, in linear fashion, from nineteenth-century critical realism to the socialist realism of the twentieth, the current apogee of literary creativity. Yet it did not hurt that Engels personally had authorized the status of Balzac, qua an obscure but widely quoted letter that praised the latter's detailed account of nineteenth-century French society “from which … I have learned more than from all the professed historians, economists, and statisticians of the period together” (Marx and Engels Reference Marx and Engels1947, 42). Engels's “endorsement” made possible a flood of Balzac publications in the first decade of the PRC, but the French author was running out of luck when he came under attack at a meeting on literary theory in Shanghai in the spring of 1960 and was lumped together with other bourgeois writers such as Stendhal, Romain Rolland, and Leo Tolstoy (Gu Reference Wei1987, 31). Translating and publishing Balzac henceforth became much more difficult; after a brief hiatus, a number of reprints and new translations appeared in 1962, albeit with carefully worded prefaces that chided Balzac for being “a monarchist and a fervent Catholic” whose “main failure” was to propagate suffering in restraint rather than resistance and rebellion.Footnote 24 By 1964, though, no endorsements or positive framing would help Balzac, and Chinese readers had to wait until 1978 for new editions. (But note that Balzac's novels were easily available in libraries, reading rooms, and private collections, and were read widely before and during the Cultural Revolution under the auspices of private reading, as noted above.)

Less frequent, but no less significant, was the circulation of foreign literary works by way of negative framing. The negative mode of contextualization and interpretation serves a range of purposes: It exposes the corrupt nature of foreign literature, their authors, and their societies as a whole; it functions as a negative foil that highlights the splendid achievements of Chinese cultural production as against these foreign products; it serves as a warning of corrupt tendencies that need to be prevented from taking root on Chinese soil; and it makes available for dissection and selective appropriation works that may be undesirable in their entirety, but contain valuable aspects. We have encountered such arguments in Zhaiyi’s reply to its readers; and it is true that negative examples are much more frequently found in neibu publications. Yet they also appear in the open public sphere, and I will discuss a particularly interesting case here.

As noted in the previous section, a neibu edition of Jack Kerouac's On the Road appeared in 1962. The beat generation as a whole, in its aesthetics no less than its public posture, would arguably make it anathema to publication or discussion in the open public sphere of High Maoism. Yet that is exactly what happened: we find references in the open press that not just make clear that editors such as those of Shijie wenxue were acquainted with the latest trends of the American avant-garde, but that apparently were to keep the Chinese reading public informed about some of the more provocative literary developments in the capitalist West. In February 1960, at the height of Mao's Great Leap Forward, Shijie wenxue published a detailed, eleven-page essay entitled “A moribund class and a corrupt literature: The American ‘beat generation’” (Ge Reference Ha1960).Footnote 25 Recent American writing, from Steinbeck's The Pearl to the works of Leftist authors such as W. E. B. Du Bois, had appeared periodically in Yiwen. With the beat generation, however, Shijie wenxue engaged a literary trend that was controversial even in the United States.

As the title suggests, the article frames its discussion in distinctly negative terms; the rhetoric of decadence and sociopolitical decay was boilerplate for contemporary readers, who were very much used to reading about the impending, ongoing, or accelerating decline of the United States. Apart from predictable value judgments, however, the author presents a wealth of contextual and factual information, as well as long excerpts from a range of works that provide a fairly accurate image of the aesthetic concerns of the beat generation writers. The article seems to draw primarily on Gene Feldman's and Max Gartenberg's seminal The Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men (Reference Feldman and Gartenberg1958), and especially that book's introduction, as well as the contemporary American press. True to the theme laid out in the title, the author begins with a rather gossipy portrayal of the “decadent” lifestyle of the beatniks, mentioning Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, among others, and dwells at some length on the sensational 1957 “Howl” trial in San Francisco. The article then provides an informed and factually accurate summary of Jack Kerouac's background, followed by a detailed synopsis of On the Road, which appears to thrive on its voyeuristic pleasure: the quest for freedom that speaks from the novel—social, spiritual, sexual—is contagious, easily piercing the article's thin layer of perfunctory mockery and invective. After two pages of breathless description of road trips at 110 miles per hour, sex, rock and roll, and all-night parties, the dismissal of the novel as “dirty and repulsive” (angzang bukan 骯髒不堪) appears feeble and ineffective.Footnote 26 In a similar vein, extensive quotations from Ginsberg's “Howl” are surprisingly inspired and effectively transport the energy, the fury emanating from Ginsberg's diction. The quality of the rendering suggests a sustained and serious engagement with Ginsberg's work on behalf of the translator(s).

Within the allocated space, the article clearly aims at breadth as well as depth. Apart from Kerouac and Ginsberg, it provides brief portraits of Lawrence Lipton, John Clellon Holmes (noting the influence of Holmes's Go, considered the first beat novel), and Ferlinghetti. Again, the author provides extensive quotations from the latter's poem “Dog” (156). Finally, and more like an afterthought, the concluding section dutifully identifies the beat generation and its literature as the cultural manifestation of a moribund postwar American society, a nation whose decline appears a foregone conclusion when seen against China's own splendid socialist culture. (Note that the PRC was mired in a major famine when the article appeared.) In sum, the essay presents an informed and knowledgeable introduction to the beat generation writers, at the time the most influential new development in American literature, or, in the author's judgment, a group of “sex addicts, drug addicts, misanthropes, reactionary catholic priests, madmen, terrorists…” (156). The only oversight might be the absence of any mention of William Burroughs, the most notorious of the group. But as if to make up for this lapse, Shijie wenxue ran a brief notice five months later, on American “drug literature” (mazui wenxue 麻醉文學), which introduced Burroughs as the foremost representative of this latest trend in American letters (Yu Reference Shi 雨石1960), thus ensuring that readers in Maoist China had an accurate, complete, and up-to-date understanding of contemporary American literature.

Its context—the essay was printed in between a Plekhanov treatise on “Art and Social Life” and a review of a new North Korean novel—makes the beat generation article appear even more bizarre. It was an outlier, but not an exception. The above-mentioned diatribe against Pearl S. Buck, which provides—over ten pages—biographical information, detailed summaries of Buck's major works, and ample quotations from her writings (Li Wenjun Reference Wenjun1960), belongs in the same category. Another intriguing example, again from the pages of the open-circulation Shijie wenxue, is a June 1963 article on the French nouveau roman (Liu Mingjiu and Zhu Hong Reference Mingjiu 柳鳴九 and Hong 朱虹1963; see also the discussion in Iovene Reference Iovene2014, 71–72). On over twenty pages, the authors provide an overview of the development of the nouveau roman since its beginnings in the 1950s, from Robbe-Grillet's Les gommes (1953) to the more recent craze and its echoes in the French press, trying to explain why its proponents “lash out mercilessly” at the “highly acclaimed critical realists” of the nineteenth century (90). The article expresses dismay at the fashionable craving for novelty of the bourgeois French literary world, but also notes: “Their ‘new techniques’ have met with strong approval in capitalist countries such as England and America and have become subject of dissertation theses and academic research. Since the nouveau roman has become so influential, we need to pay attention to it” (89). The justification for a detailed discussion of the topic thus draws on foreign sources—and capitalist nations as such. As the authors make clear, developments in the contemporary world of letters abroad are relevant for readers in the PRC. And to make sure that Chinese readers get at least some impression of the new trend, the article is followed by a brief excerpt from Nathalie Sarraute's Le planetarium (1959), an “important representative work” of the nouveau roman (102). Just as in the case of the beat generation writers, Shijie wenxue thus decided to introduce its Chinese readers to some of the latest and most influential trends in Western literature—the very term nouveau roman had been coined only in 1957, and Robbe-Grillet's Pour un nouveau roman was published only in 1963. These developments, remote as they might seem from contemporary cultural production in the PRC, did matter to the editors of Shijie wenxue, who apparently believed that they should matter also to their audience in the open public sphere, and thus to Chinese letters at large.

Conclusion

The 1980s witnessed an explosion of literary creativity in the PRC. Many of the authors involved in the feverish search for a new voice, for new aesthetic and narrative modes of expression, had grown up during the era of High Maoism, and credit their inspiration to reading practices during this time: underground novels, hand-copied volumes of foreign fiction, clandestine literary networks (Bei Reference Dao, Larson and Wedell-Wedellsborg1993; Shen Reference Zhanyun 沈展雲2007, 13, 15, 16–22). These experiences, people such as the poet Bei Dao later claimed, allowed them to pick up where their forebears had left off at the founding of the PRC in 1949, to rebuild China's cosmopolitan heritage.

Such claims, shaped as much by the feverish climate of the 1980s reform era as by the xenophobic discourses of the Mao period, need to be revisited. As I have shown on the preceding pages, the cosmopolitan tradition of modern China did not rupture in 1949. The 1950s saw an unprecedented (in both numbers and diversity of sources) influx of foreign literature into socialist China. While the Soviet Union replaced Western Europe as the center of the literary world map, literature from other socialist nations, from developing countries, and even the capitalist West continued to appear in Chinese literary journals and on the shelves of bookstores. And throughout the period of High Maoism, an astounding range of foreign literature was translated and disseminated in China, where it was consumed in the open and the restricted public sphere, as well as the private realm.

Qualifications are, needless to say, in order. Far from everything was translated and published. Kerouac and Kafka were; Burroughs and Robbe-Grillet were not. The choices made by publishers are often surprising, but selectivity remained the rule. Translations, if they appeared, were often not reprinted. Distribution was frequently restricted. Those who had access to neibu books before the Cultural Revolution often were denied access after 1966, and vice versa. Notably, sources such as the catalogue of neibu publications do not list any literary translations published between the summer of 1966 and 1970, neither have I found publications from this era, leaving us with a hiatus during the brief high tide of the Cultural Revolution. But, throughout the twenty-year period under discussion in this essay, Chinese translators produced a steady stream of translations that need to be seen as controversial and even contrarian in light of contemporary literary policies and Chinese literary output. The range of these publications—from Ehrenburg and Baklanov to Mishima, Pearl S. Buck, and the beat generation writers—is staggering and shows well-informed, professional translators and literary specialists at work. These translations reached Chinese audiences through a variety of channels: clandestine reading networks drawing on private collections, libraries, and reading rooms; the large and multi-layered restricted public sphere with its journals and book series; and the open public sphere, where attentive audiences could read works “endorsed” by Soviet or Chinese critics, or otherwise penetrate layers of invective and abuse to gain glimpses of the latest output of the literary avant-garde from around the globe. The borders between the open and the restricted, between the public and the private, were often porous. The different spheres interacted with one another: An author (such as Pearl S. Buck) vilified in public was translated and published in the restricted public sphere. And even when the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution disrupted publication, it did not bring reading to a halt. As Barbara Mittler (Reference Mittler2013, 191) has pointed out, houses were ransacked and libraries pried open; as a result, access restrictions were all but unenforceable during these years.

Circulation alone, however, is of limited value as a measure for the cosmopolitan practices of the era of High Maoism. Access to foreign literature was restricted, but it did not disappear from the literary field—the glass may be half full or half empty. Of real significance, I argue, are the attitudes of both publishers and readers: the editors at China's most influential publishing houses and literary magazines, as well as their audiences, agreed in giving weight and meaning to foreign literature. Publishers commissioned translations and background articles from Chinese translators (who were often the best and most knowledgeable in their fields) because they believed that these translations—from dissident Soviet writers to the contemporary Western avant-garde—were important for China and for their readers, however broad or narrowly this readership was defined. They believed that these works were meaningful, and that readers in the PRC should be well acquainted with new literary developments across the globe: that they should know (about) these authors and these works and these trends, and that they probably wanted to know. Readers, in turn, largely agreed. Studying literary consumption is notoriously difficult, but the available evidence suggests that translations of foreign literature found enthusiastic readers, both before and during the Cultural Revolution, through the various channels discussed in this essay.

The broad agreement of editors on the one hand and readers on the other about the significance of foreign literary production for socialist China allows us to venture one further claim: that foreign literature, just like before 1949, ultimately served as a benchmark, an implicit yardstick against which Chinese cultural production was measured. Official policy pronouncements notwithstanding, the practices of publishing and reading suggest that throughout the High Maoist period, foreign literary production constituted the framework within which Chinese practitioners and audiences alike comprehended the notion of literature itself—a screen of reference onto which Chinese literature was projected, a sounding board for domestic cultural production. Even during the most xenophobic of days, Chinese cultural production was conceived in transnational terms, in a global context. It is impossible, within the scope of this article, to prove the validity of these claims. The impact of cultural consumption on cultural production, in the Mao era and beyond, warrants further research. What the survey of readings patterns reveals, however, is a cosmopolitan mindset that has internalized the idea that modern culture, very much in the sense predicted by Marx, is a fundamentally transnational affair that has long since transcended “national one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness.” This mindset, reflected in actual practices of cultural production and cultural consumption, persists even when cosmopolitanism is rejected or attacked by official rhetoric. Chinese literature is a part of world literature, and world literature has become an inalienable part of literary life in China.

The clandestine circulation of literary works, in the sense explored by Robert Darnton (Reference Darnton1995), is an age-old phenomenon, yet one that is, as an explanatory model, of limited value for the High Maoist era. Foreign literature was circulated and consumed in the PRC, in a partly clandestine and partly open manner. Yet that which had gone underground, hidden under layers of access restrictions, carefully worded “endorsements” and justifications, and denunciatory and abusive commentary, were not simply the books themselves, but the commitment to the world and world literature. Beneath this surface veneer, a deeply ingrained belief in the salience and significance of an evolving world literature lived on, perpetuating and affirming the cosmopolitan tradition of the decades before 1949. What had gone clandestine, as it were, was cosmopolitanism itself.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Jonathan Abel, Jennifer Altehenger, Lena Henningsen, and Shuang Shen, all of whom read and commented on earlier versions of this article, and to the two anonymous reviewers for the Journal of Asian Studies for their critical suggestions.