Introduction

Acceptance that the world is in the midst of an ecological emergency has grown markedly among national and international policymakers in recent years, not least because of climate movements and the increasingly stark evidence presented by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022) about the scale and timing of the problems. Even though many countries, mainly in the Global North, have committed discursively at least to net zero emission targets by 2050, the remaining carbon budget that is compatible with the one point five degrees Celsius warming target is estimated to run out within six point five to nine years if rising global emission trends continue at the current pace (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Rosen, Lamboll and Rogelj2022).

These developments raise important issues for national social protections systems – and social welfare more generally – for three main reasons. Firstly, particularly in the Global North, balancing the fiscal requirements for meeting net zero targets with the often path-dependent commitments made in social protection budgets presents a major challenge (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2011). Secondly, the environmental crisis has implications for the social risk landscape within which social protection systems operate (e.g. extreme weather events increase risks to livelihoods, shelter and health; IPCC, 2022) and which they are not always well designed to mitigate (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Guenther, Leavy, Mitchell and Tanner2009; Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose2013). More generally, the crisis also affects traditional social risks such as unemployment and redundancy. Mitigating such risks could be crucial in legitimising the decarbonisation of the economy, reducing energy consumption and protecting the most badly affected (Gough, Reference Gough2017). Social protection systems might also be used to ensure de-carbonisation costs (e.g. through the use of carbon taxation, fall least on the poorest households) particularly given their carbon footprint is smallest (Preston et al., Reference Preston, White, Browne, Dresner, Ekins and Hamilton2013; Büchs and Schnepf, Reference Büchs and Schnepf2013). Thirdly, and more fundamentally, founded on the assumption of capitalist growth and funded by it, social protection systems have also contributed crucially to the crisis (Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2019; Büchs, Reference Büchs2021b).

Notwithstanding the scale of these challenges, policymakers have generally been very slow to confront them. Ecological modernisation (EM), the approach which has most guided policy ideas about economic decarbonisation, envisages some state interventions but generally emphasises market-based solutions. It favours carbon pricing (taxes) to ensure greenhouse gas emitters fully bear the costs of their actions; limited market interventions (e.g. R and D incentives) to promote low-carbon, high-efficiency technologies; and regulatory change to remove barriers to eco-friendly behavioural change by consumers (Stern, Reference Stern2007: 308/9). While the EM perspective accepts that transition will create distributive challenges (Stern, Reference Stern2007), only very limited attention has been given to addressing them (OECD, 2011, 2013). Generally favoured are limited labour market interventions to encourage re-training and improve skills, and targeted forms of financial compensation to the most-affected groups (Bridgen and Schøyen, Reference Bridgen, Schøyen and Greve2022).

Against this background, and as a means to highlight and discuss more fully the issues and challenges for social protection systems raised by the environmental crisis, this article reviews five literatures which seek to address the gaps left by EM’s neglect of these matters: Adaptive Social Protection (ASP); Just Transition (JT); Green New Deal (GND); Post-growth; and Eco-feminism. We have chosen these approaches based on a literature review, finding the first three have been the most prominent ones in recent academic and policy debates about climate change and social protection, while the latter two offer crucial critical contributions to the debate which are often underexamined. It is important to acknowledge that these are not exhaustive, and several other concepts and frameworks such as ‘sustainable welfare’, ‘eco-social policy’, or ‘eco-socialism’ are also relevant to this debate. Where possible, we discuss links to them in the relevant sections. Analytically, we focus on how each literature conceptualises the challenges of the climate crisis for social protection systems, including the scale of transformation required, the new norms and policies proposed to address these challenges and the theory of change (if any) explicit or implicit in the literature. We start with the first three literatures which share many of the assumptions of EM with respect to the nature and scale of change required to address the environmental crisis but criticise its neglect of social protection. We then consider the Post-growth and Eco-feminist literatures whose critique of EM’s approach to social protection is part of a broader critique of the nature and scale of change considered sufficient by EM to successfully address the crisis. We then discuss how the five literatures compare in relation to our analytical dimensions. We focus particularly on how ideas and interests combine in each literature to influence climate-related recommendations for social protection reform and associated theories of change. We finish by suggesting how future scholarship in this area might proceed.

Adaptive social protection

Adaptive social protection (ASP) approaches focus on the role of policies in reducing the negative impacts of global shocks, such as climate change, food insecurity and poverty, particularly in the Global South. ASP frameworks, such as adaptive social protection (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Guenther, Leavy, Mitchell and Tanner2009, Reference Davies, Béné, Arnall, Tanner, Newsham and Coirolo2013), climate-responsive social protection (Kuriakose et al., Reference Kuriakose2013) and shock-responsive social protection (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Scott, Smith, Barca, Kardan, Holmes, Watson and Congrave2018) have been proposed by international development scholars. ASP approaches share an understanding that climate change is caused by unsustainable economic growth and economic underdevelopment, and that integrating social protection in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation can help to improve the livelihoods and build long-term resilience against climate shocks among vulnerable groups. Commonly, ASP approaches seek to improve social safety nets in the interest of accelerating capitalist economic growth in low- and middle-income countries. While the focus of ASP programmes is usually on local small scale interventions, they are generally top-down driven and particularly promoted by international development agencies and organisations, such as the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank (World Bank, 2022; UNDP, 2015). One of the key arguments of ASP approaches is that present social protection policies tend to respond to short-term impacts without considering long-term adaptation to intensifying environmental risks, and that this needs to be changed (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Guenther, Leavy, Mitchell and Tanner2009; Costella et al., Reference Costella, Jaime, Arrighi, de Perez, Suarez and van Aalst2017; Aleksandrova, Reference Aleksandrova2019).

ASP policy proposals include new cash transfer programmes, job guarantee programmes, access to healthcare and new forms of household insurance against climate-related risks. For example, Norton et al. (Reference Norton, Seddon, Agrawal, Shakya, Kaur and Porras2020) argue that job guarantee programmes may potentially be used to address both social and environmental challenges in the form of ‘green jobs’. Also, cash transfers for migrants and their families may support the costs of domestic and international migration and reduce social exclusion (Johnson and Krishnamurthy, Reference Johnson and Krishnamurthy2010; Schwan and Yu, Reference Schwan and Yu2018). Other studies, such as Costella et al. (Reference Costella, Jaime, Arrighi, de Perez, Suarez and van Aalst2017), examine the potential of ‘climate smart’ social protection by using a forecast-based financing system to anticipate the need for financial support. Programme evaluations have found mixed effects: several evaluations of existing cash benefit programmes in low- and middle-income countries (Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Slater and Costella2019; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Kaur, Shakya and Norton2020; Norton et al., Reference Norton, Seddon, Agrawal, Shakya, Kaur and Porras2020) find that the programmes are successful in reducing households’ social vulnerability and providing a social safety net against short-term shocks. However, the contributions to households’ long-term climate resilience are very modest. As it has become used more frequently as a framework for social protection interventions, adaptation scholars have criticised existing ASP programmes for not fulfilling the aims of adaptive social protection models (Nightingale, Reference Nightingale2017; Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Nightingale and Eakin2015, Reference Eriksen, Schipper, Scoville-Simonds, Vincent, Adam, Brooks, Harding, Khatri, Lenaerts, Liverman, Mills-Novoa, Mosberg, Movik, Muok, Nightingale, Ojha, Sygna, Taylor, Vogel and West2021; Tenzing and Conway, Reference Tenzing and Conway2022). Efforts have mainly focused on applying technical adjustments in existing programmes rather than considering the changing nature of climate shocks and addressing more fundamental issues for global climate justice, such as eliminating inequality and strengthening people’s autonomy (Tenzing, Reference Tenzing2020; Ulrichs et al., Reference Ulrichs, Slater and Costella2019). In other words, adaptive social protection policies often appear as de-politicising techno-fixes for historically-grown global inequalities.

Overall, adaptive social protection scholarship brings attention to the unequal global development of social protection systems and the resulting difficulties of responding to the climate crisis for the most affected countries in the Global South. A vast challenge for ASP advocates remains poor countries’ limited access to funding, to which international development actors have responded with new proposals for attracting private investment. Critics have argued that an increasing reliance on private capital through de-risking facilitates greenwashing, reproduces global wealth inequalities and limits alternative development strategies such as Green New Deals (Gabor, Reference Gabor2021). Yet there are a range of other alternative frameworks available, such as Just Transition discussed in the next section.

Just Transition

‘Just Transition’ (JT) concepts date back to 1970’s labour environmentalism (Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2015). US trade unions then had realised practical trade-offs between environmental and workers’ protection when, for instance, they supported polluting industries to secure jobs (Newell and Mulvaney Reference Newell and Mulvaney2013: 133). The need to reconcile ecological and employment demands became urgent. The International Trade Union Conference, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the UN Environment Programme later engaged in formulating the JT approach which included an emphasis on “procedural fairness, promoting dialogue and engagement with workers and communities beyond the narrow questions of green jobs or pension schemes” (Abram et al., Reference Abram, Atkins, Dietzel, Jenkins, Kiamba, Kirshner, Kreienkamp and Parkhill2022: 1035). Stepwise, the approach experienced international diffusion and was broadly integrated in trade unions’ and international organisations’ programmes (Silverman, Reference Silverman2004). JT was then included in the Paris Agreement, referring to “imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities” (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, (UNFCCC) 2016: 2).

Developed as a concept in the context of labour relations, JT focused at the beginning particularly on economies in the Global North. The baseline argument was that the reckless pursuit of economic growth in the existing economic models was environmentally and socially unsustainable. Hence, a decarbonised economy then was to be reconciled with citizens’ social needs. These social needs were mainly understood as workers’ needs, which meant ‘appropriate measures to protect jobs in vulnerable industries’, ‘adequate support would be needed for people and sectors that stand to lose out as a result of decarbonising the economy through compensation and retraining for new employment opportunities’, ensuring ‘that new jobs created in low-carbon sectors provide ‘decent’ jobs’ (Newell and Mulvaney Reference Newell and Mulvaney2013: 134). Just as economic growth was mostly not criticised as such but rather called to be sustainably transformed, dependent labour and welfare state arrangements were usually not fundamentally questioned. A strong practical focus has laid on social dialogue approaches to empower labour movements.

While in current academic debates, we can observe attempts to bring the JT approach in dialogue – or even to merge it – with more fundamentally transformative approaches such as post-growth, or eco-feminism (Heffron and McCauley, Reference Heffron and McCauley2018; García-García et al., Reference García-García, Carpintero and Buendía2020), the main JT route is still focused on the Global North, and not aiming at fundamental societal change. However, we can observe a shift in the literature that goes from seeing social justice as a necessary add-on to green economic reforms to conceptualising “societal justice as the core to achieving a sustainable energy transition” (Abram et al., Reference Abram, Atkins, Dietzel, Jenkins, Kiamba, Kirshner, Kreienkamp and Parkhill2022: 1036), which points towards a more ‘holistic view of society’ (Heffron and McCauley, Reference Heffron and McCauley2018: 4). In the academic literature on JT, it is still noticeable that the JT approach is a bottom-up approach developed from trade unions. Formulating strategies for the practice and analysing routes for implementation is a vital part of the debate (Sharman, Reference Sharman2021; Galgóczi, Reference Galgóczi2020; Routledge et al., Reference Routledge, Cumbers and Derickson2018). The analysis of power relations and the discussion of social dialogue in a more traditional sense (i.e. inclusion of trade unions and employers’ associations) as well as including a broad array of societal stakeholders is central in the literature, with different theoretical and empirical approaches (Cha and Pastor, Reference Cha and Pastor2022; García-García et al., Reference García-García, Carpintero and Buendía2020; Winkler, Reference Winkler2020; White, Reference White2020). Furthermore, the focus is also increasingly expanded beyond the Global North (Pucheta and Sànchez, Reference Pucheta and Belén Sànchez2022). The discussion of different dimensions of justice is also a crucial substrand in the debate, mainly highlighting the interplay of procedural justice (consultation of affected parties), distributive justice (fair distribution of costs and benefits), recognitional justice (recognition of horizontal and vertical inequalities; e.g. gender, class, ethnicity, Global North/South divide), and restorative justice (compensating past harm) for a just transition (Abram et al., Reference Abram, Atkins, Dietzel, Jenkins, Kiamba, Kirshner, Kreienkamp and Parkhill2022: 1036; see also Fuller and McCauley, Reference Fuller and McCauley2016).

In the past years, the concept of JT has also reached governmental programmes and strategies – at least rhetorically. For instance, in the EU’s decarbonisation strategy, the European Green Deal, ‘Just Transition’ is strongly emphasised, and a Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) is established that shall “ensure that the transition towards a climate-neutral economy happens in a fair way, leaving no one behind” (EC, 2023). However, first analyses of the JTM show that there is little in there that matches trade unions’ and academics’ demands for a just transition (Moesker and Pesch, Reference Moesker and Pesch2022: 102750). Similar mismatches have been noted in the related literature on Green New Deals, the focus of the next section.

Green New Deal

The proposal for a ‘Green New Deal’ (GND) originally emerged from a variety of mainly politically left-wing sources in the late noughties as a means to combine economic stimulus and decarbonisation in responding to the financial crisis (NEF, 2008; Friedman, Reference Friedman2007; Schepelmann et al., Reference Schepelmann, Stock, Koska, Schüle and Reutter2009). Like EM approaches, its emphasis was initially on technological change, particularly a rapid move towards ‘clean energy’ as the primary means for addressing global warming (Pollin, Reference Pollin2019). In contrast, however, the GND proposed broad-ranging public, as well as market-based, action. Influenced by Just Transition approaches it stressed the importance of supporting displaced fossil fuel workers. Over time, the scope and ambition of GND thinking has increased but most plans remain founded on ambitious programmes of public economic and social intervention, promoting a revitalised and updated Keynesianism as an alternative to neo-liberal austerity (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Leggat, Morikawa, Pappas and Stephens2021; Schlosser, Reference Schlosser2021). Most are reformist rather than transformative: the pursuit of capitalist economic growth remains possible and desirable, both in the Global North and South (Pollin Reference Pollin2019); and socio-economic change is largely achievable through traditional forms of liberal democratic mobilisation.

In terms of social protection policy, most GNDs have drawn strongly from ideas developed as part of the JT approach (see above), the continuing development of which remains an important influence (Just Transition Centre, 2017). The primary focus of most GNDs has thus been paid employment and/or wage risks generated by economic decarbonisation, for (mainly male) labour market insiders (Rueda, Reference Rueda2005) employed in carbon-heavy industries (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Leggat, Morikawa, Pappas and Stephens2021). ‘Green jobs’ are at the core of this approach based on the promise that growing green industries will provide a greater amount of well-paid unionised employment (Sanders, Reference Sanders2019). To facilitate and ease the transition process or assist those who are not quickly re-employed or choose to retire, ‘emergency’ ALMPs, financial support and re-training policies are generally proposed. These are designed to supplement existing social protection systems, which are not generally regarded as requiring root-and-branch reform.

The most detailed of such plans are Pollin et al.’s (Reference Pollin, Garrett-Peltier and Wicks-Lim2017) GND for Washington State and the employment and retraining sections of Bernie Sanders’ (Reference Sanders2019) broad-ranging GND developed as part of his presidential campaign. These both proposed: a wage and/or job guarantee for younger workers, lasting for five years in the Sanders plan, which would maintain wages at previous levels; significant resources for retraining and re-location, providing in the Sanders Plan either a four-year college education or vocational job training with living expenses provided; financial support for older, pre-retirement workers choosing early retirement over re-employment; and state support for the multi-employer occupational pension schemes operating in fossil fuel industries, which would otherwise likely collapse as the industry contracted (Pollin et al., Reference Pollin, Garrett-Peltier and Wicks-Lim2017; Sanders, Reference Sanders2019).

Some of these proposals appear to have influenced the Biden Presidency’s environmental policies and the European Green Deal, both of which have promised a step-change in the resources provided to economic decarbonisation (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Farrell and Stevis2022; Sabato et al., Reference Sabato, Jessoula, Mandelli, Schoyen, Hvinden and Dotterund Leiren2022), and greater recognition of the need to protect citizens at risk of being ‘left behind’. However, some commentators regard such commitments as primarily discursive (Gengnagel and Zimmermann, Reference Gengnagel and Zimmermann2022) and there is also scepticism whether the governance arrangements exist in either polity for them to be fully implemented (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Farrell and Stevis2022; Sabato et al., Reference Sabato, Jessoula, Mandelli, Schoyen, Hvinden and Dotterund Leiren2022; Tollefson, Reference Tollefson2020).

Moreover, based on criticisms of the first wave of GNDs’ rather narrow, labourist focus, the social concerns considered in GND (Green New Deal) debates have broadened. The influence has become more evident of the environmental justice movement (Klein, Reference Klein2019), the eco-socialist left (Schwartzman, Reference Schwartzman2011) and post-growth proponents (Schor and Jorgenson, Reference Schor and Jorgenson2019), leading some commentators to suggest the emergence of a more radical GND2 (Mastini et al., Reference Mastini, Kallis and Hickel2021). Thus, Sanders’ plan, for example, incorporates concerns to protect ‘frontline communities’ as well as displaced workers, particularly those affected by existing disadvantages of class, ethnicity and race (Sanders, Reference Sanders2019: see also Klein, Reference Klein2019).

More generally, closer links have been made between the environmental crisis and the social crisis of inequality, based mainly on work linking income and wealth inequality and carbon emissions (Jorgenson et al., Reference Jorgenson, Schor, Knight and Huang2016; Galvin and Healy, Reference Galvin and Healy2020; Klein, Reference Klein2019; Schor and Jorgenson, Reference Schor and Jorgenson2019). This has led to proposals for a broader range of social policy reforms in addition to the immediate support proposed for displaced workers, including more universal job guarantees and commitments to economic security in work and retirement (Sanders, Reference Sanders2019). However, the links between income inequality and carbon emissions, particularly, remain contested (Gough Reference Gough2017: 80-2) and the role of these broader social reforms in mitigating environmental challenges is not always well specified (Galvin and Healy, Reference Galvin and Healy2020). Despite the increased influence of eco-socialism, even GND2 is predominantly reformist in its approach to capitalism.

Gough’s outline of eco-social policies is the most developed and radical summary of such reforms (Reference Gough2017, Reference Gough2022). Social protection systems under such plans would be variously deployed to compensate losers of carbon reduction policies, such as carbon taxes, target financial support for housing retrofits on households in fuel poverty and, more generally, reduce income inequality as a means to address excess positional consumption (Gough, Reference Gough2017: 144 and 168). Gough, and some post-growth scholars (Mastini et al., Reference Mastini, Kallis and Hickel2021), regard such plans as a potential steppingstone to a more concertedly post-growth future, only a minority of which GND proponents have explicitly considered (Aronoff et al., Reference Aronoff, Battistoni, Cohen, Riofrancos and Klein2019; Pettifor, Reference Pettifor2019). However, as will be discussed in the next section, there is also concern among post-growth scholars that some social protection systems GND proponents wish to preserve are drivers of GHG emissions.

Post-growth

Post-growth approaches offer a radical perspective on climate change, proposing a fundamental transformation of current economic and welfare systems. Post-growth approaches argue that global climate targets as set out by the IPCC (2022) cannot be achieved in a context of continuing global GDP growth because there is currently no evidence that global emissions and GDP growth can be decoupled in absolute terms and at the required speed (Haberl et al., Reference Haberl2020; Parrique et al., Reference Parrique, Barth, Briens, Kerschner, Kraus-Polk, Kuokkanen and Spangenberg2019). This evidence suggests that any serious attempts to tackle climate change would require wealthy countries in the Global North to transition to a post-growth economic system.

A transition to post-growth economies would have wide-ranging consequences for welfare states more generally and social protection systems specifically. Welfare states and growth-focused economic systems have evolved in tandem and remain closely coupled (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021b). On the one hand, financing social protection systems depends on economic growth (Bailey, Reference Bailey2015; Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2021). Economic contractions within growth-based economies lead to unemployment and hence reduce social insurance and tax payments that fund social protection systems. In addition, ageing societies, a trend in all developed welfare states, will require more resources for old age pensions, health and social care in the future. Some actors therefore argue that economic growth is necessary to fund future welfare state expansion (Bailey, Reference Bailey2015; Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2021). The dependency between growth and welfare states is bi-directional, however, as welfare states and social protection systems support economic growth by stabilising demand, improving population education and health, and supporting social stability (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021b; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020).

While decoupling welfare and social protection systems from economic growth would bring numerous challenges, various proposals have been made for supporting social protection in a post-growth context, often under the framing of ‘sustainable welfare’. First of all, proponents highlight that post-growth fundamentally differs from economic contraction within a growth-focused context (Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Paulson, D’Alisa and Demaria2020; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Kallis and Martinez-Alier2010). Post-growth seeks to establish an alternative, post-capitalist sustainable welfare system (Büchs, Reference Büchs2022) that prioritises social and ecological objectives over economic growth, both within policy making as well as at the corporate and organisational level (Raworth, Reference Raworth2017). While there are many affinities between the post-growth and eco-socialism literatures, they sometimes differ on views about the desirability of growth in a post-capitalist future and the role of private property (Kallis, Reference Kallis2019, Vergara-Camus, Reference Vergara-Camus2019). Post-growth advocates claim that policymaking within a post-growth economy would seek to ensure that opportunities and resources, including assets such as productive capital, property, and land, are distributed more evenly. It is thought that this preventative approach would, in the longer-term, reduce the need for poverty and inequality reduction, as well as for other welfare expenditures which are currently required in response to social problems that are aggravated by high levels of inequality (Wilkinson and Pickett, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2019).

Post-growth economies with sustainable welfare systems would also focus more directly on ensuring needs satisfaction for all, thus reducing demand for social security payments (Büchs, Reference Büchs2022; Koch, Reference Koch2022). The concept of ‘basic needs’ has become very prominent within these debates because it offers a framework for re-orienting economics from current satisfaction of preferences and wants through (over-)consumption to the satisfaction of satiable needs within planetary boundaries (Gough, Reference Gough2015). This perspective also offers an alternative perspective on social protection with a greater emphasis on the direct provision of in-kind benefits such as health care, education, housing, as well as access to domestic energy, transport and internet. Such a provision of Universal Basic Services (UBS) (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021a; Coote and Percy, Reference Coote and Percy2020) could reduce the need for cash payments because they would contribute directly to the satisfaction of basic needs.

To curb emissions and create greater social equality and inclusion at the same time, post-growth perspectives also promote a fall in production and consumption via working time reduction, work redistribution, and a decoupling of work and social protection (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021a; Jackson and Victor, Reference Jackson and Victor2011; Koch, Reference Koch2022). Working time and productivity reductions are thought to reduce output and consumption and hence reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Jackson and Victor, Reference Jackson and Victor2011). At the same time, working time reduction and redistribution of work would contribute to maintaining employment levels and social inclusion through work. Crucially, social protection would need to be decoupled from formal labour market participation and instead be provided on a universal basis. This can include cash benefits and in-kind social protection benefits through UBS as discussed above, as well as income guarantees or universal income schemes (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021a; Coote and Lawson, Reference Coote and Lawson2021). In addition to ecological benefits of working time reduction, proponents emphasise likely social benefits such as people having more time that they can spend on wellbeing-promoting activities such as nurturing social relationships, exercise, care and cultural activities.

Post-growth approaches envision transformational theories of change as incremental change within the current system would fail to target underlying institutions of growth-based, socially exploitative, and ecologically destructive capitalism. The post-growth perspective advocates more radical, transformative change towards a new system through peaceful, inclusive and democratic processes (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Regen, Cadiou, Chertkovskaya, Hollweg, Plank, Schulken and Wolf2022).

Eco-feminism

Ecological feminism is a broad strand of feminist research and activism concerned with the systemic and historical relationship between gender oppression and environmental destruction. While initially focused more narrowly on the oppression of women and nature (Mies and Shiva, Reference Mies and Shiva2014), the focus of eco-feminist scholarship has broadened towards the multiple relationships of gender relations and the environment, and its intersections with other forms of structural oppression (Gaard, Reference Gaard2015). Eco-feminist research has been critical of the promises of capitalist economic growth and EM, similar to post-growth studies. At a theoretical level, much eco-feminist research has sought to understand how the systemic logics and historical dynamics of capitalism necessitate not just the exploitation of wage labour but also the expropriation of women and genderqueer people, indigenous peoples, animals and the biosphere (Gaard, Reference Gaard2015; Oksala, Reference Oksala2018; Salleh, Reference Salleh, Fakier, Mulinari and Räthzel2020), such as through mechanisms of free-riding and market-creation (Oksala, Reference Oksala2018). This perspective is also influenced by the emphasis on colonial violence and unequal economic exchange from anti-colonial theories and movements (Gebrial and Kaur Paul, Reference Gebrial and Kaur Paul2021; Mies and Shiva, Reference Mies and Shiva2014; Tilley and Ajl, Reference Tilley and Ajl2023). Overall, eco-feminist research and activism challenges the belief that capitalist modernisation towards a green economy is a sufficient solution, instead demanding radical transformation.

A central concern of eco-feminist scholarship is with the labour and institutions of social reproduction, which post-growth and other critical ecological scholarship often fails to analyse (Saave and Muraca, Reference Saave, Muraca, Räthzel, Stevis and Uzzell2021). Social reproduction can be broadly understood as the complex sets of practices, processes and technologies that reproduce humans on a daily and generational basis, which are necessarily interdependent with ecological reproduction and create both life and death (Murphy, Reference Murphy and Mojab2015). It is a well-rehearsed feminist claim that labour of social reproduction is predominantly performed by women for little or no pay, reproducing unequal gender relations and intersectional vulnerabilities to the climate crisis in the process (Heintz et al., Reference Heintz, Staab and Turquet2021). Empirical research increasingly documents that unequal gender relations make women and genderqueer people more vulnerable to climate change and can result in unequal effects of climate policies (Daalen et al., Reference van Daalen, Jung, Dhatt and Phelan2020; Pearse, Reference Pearse2017), but this has had limited impact on climate policy (Djoudi et al., Reference Djoudi, Locatelli, Vaast, Asher, Brockhaus and Sijapati Basnett2016; Huyer et al., Reference Huyer, Acosta, Gumucio and Jim Ilham2020). Another central concern of eco-feminist scholarship is reproductive justice, a Black feminist concept concerned with the human right to have children, not to have children and to parent children in safe and healthy environments (Ross, Reference Ross2017). This brings critical attention to the prominent environmentalist discourse on restricting population growth which can function as a distraction from addressing the causes of the climate crisis, and as the basis for racist interventions in the lives of women of colour in the Global South (Tilley and Ajl, Reference Tilley and Ajl2023).

There are several norms and policy proposals emerging from recent eco-feminist research and activism that seek to address these underlying unequal power relations.

Firstly, many eco-feminists demand more universal, more redistributive social protection systems to better protect women and other marginalised groups from climate change impacts and reduce inequalities. Policy proposals emphasise a de-linking of employment trajectories and access to social protection, such as through forms of green basic income to better protect unpaid caregivers (Laruffa et al., Reference Laruffa, McGann and Murphy2021; Williams Reference Williams2021). To address intersectional inequalities in access to social protection, many have also called for abolishing restrictions on immigrants’ social entitlements in advanced welfare states as well as radical reforms of global financial institutions to allow the development of social protection systems in the Global South (Cohen and MacGregor, Reference Cohen and MacGregor2020; Williams, Reference Williams2021; Gebrial and Kaur Paul, Reference Gebrial and Kaur Paul2021).

Secondly, like other feminist social policy scholarship, eco-feminist perspectives seek to expand the scope of the eco-social protection debate to include social services and the paid and unpaid social reproductive work that sustains them. Problematising the gendered and racial inequalities in contemporary care economies, many urge for a radical transformation of social reproductive labour, including through more public ownership of services, better pay, more workplace democracy and universal working-time reduction (Aronoff et al., Reference Aronoff, Battistoni, Cohen, Riofrancos and Klein2019; Cohen and MacGregor, Reference Cohen and MacGregor2020; Williams, Reference Williams2021). A variety of approaches to the welfare state exists with eco-feminist scholarship, with some rejecting it as inherently violent and proposing an alternative strategy of commoning collective care provision which does not rely on the existing capitalist welfare state (Saave and Muraca, Reference Saave, Muraca, Räthzel, Stevis and Uzzell2021; Wichterich, Reference Wichterich, Harcourt and Nelson2015; Mies and Shiva, Reference Mies and Shiva2014), while others suggest that reforming existing welfare institutions is possible and desirable, albeit proposals differ on how far reforms should go (Williams, Reference Williams2021).

Finally, eco-feminist thinking places great importance on democratic processes of transformation and challenges the idea of eco-social policy as a technocratic issue to be solved by political elites and academics. Many have criticised the underrepresentation of women and feminist movements from climate policy making, and demanded more democratic processes to address systemic inequalities (Daniel and Dolan, Reference Daniel and Dolan2020; Gay-Antaki, Reference Gay-Antaki2020). Some extend the demand to the democratic management of eco-social services and workplaces (Williams, Reference Williams2021) as well as public investment decisions (Mellor, Reference Mellor2019). Concrete accounts of how such processes of transformation should be implemented in the face of institutionalised gendered power relations are lacking however.

Overall, eco-feminist scholarship urges scholars to engage in a systemic analysis of the relationships between social and environmental injustice, and the role of capitalist welfare institutions in reproducing it.

Discussion

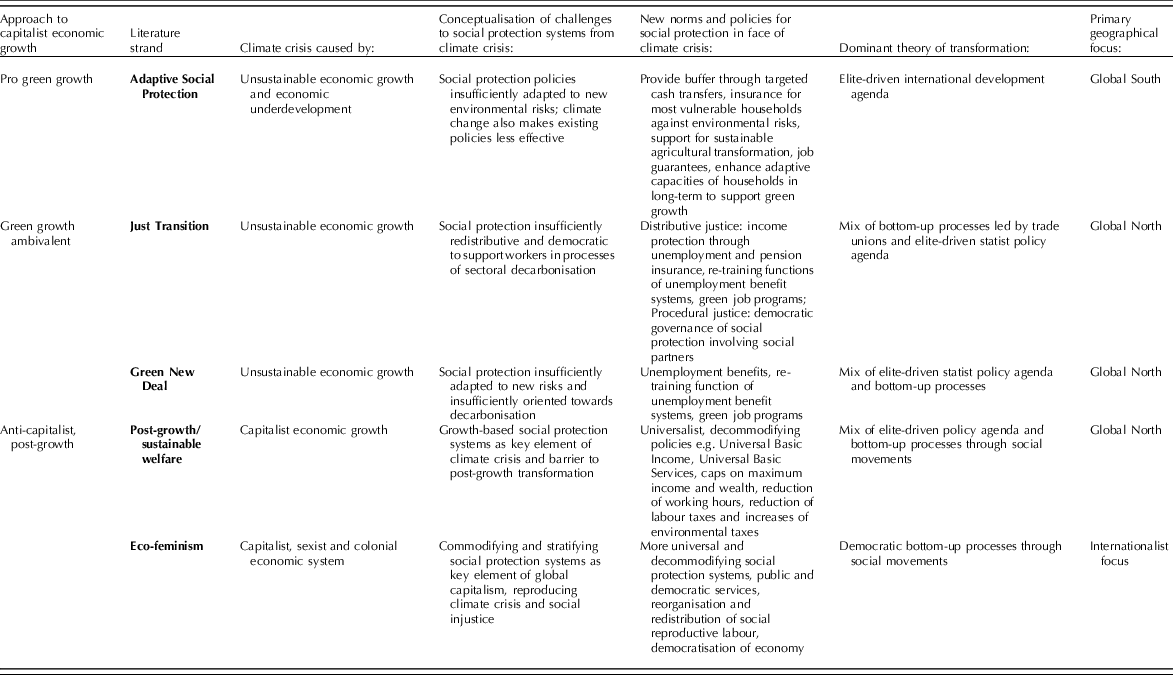

Our review of the academic and non-academic literature on the climate crisis and social protection policy suggests that there are at least five distinct policy frameworks critical of the dominant EM perspective. Each of these can be distinguished along several dimensions and has different strengths and weaknesses as we will further discuss below. Table 1 below provides an overview:

Table 1. Comparison of different policy approaches to the climate crisis and social protection

A significant difference between these normative eco-social policy frameworks are their underlying assumptions and theories concerning the causes of the climate crisis, which are not always made explicit. We find that approaches are located on a spectrum between a green growth orientation and a green anti-capitalist orientation. While the former is based on the belief that a more sustainable capitalist system that decouples GDP growth from resource use and associated waste products like emissions is achievable, the latter questions that absolute decoupling at the global level is achievable within the remaining time and hence rejects GDP growth as the goal of economic policy, as well as capitalist logics of profit accumulation through private property relations, as environmentally and socially destructive.

Our analysis suggests that the new social protection norms proposed by scholars in different policy frameworks are shaped by their understandings of the climate crisis and the role of capitalist growth, as well as the geographical and actor political context within which they were developed. On the pro-growth end of the spectrum, Adaptive Social Protection approaches which emerged as part of international development research consider unsustainable growth a primary cause of the climate crisis and poverty a primary amplifier. Its proponents consequently suggest a range of small-scale eco-social public policy interventions such as cash transfers and jobs programmes to adapt poor persons in the Global South to climate change and to accelerate capitalist development. Just Transition proposals have a similar green growth orientation but, predominantly at least, have been focused on the Global North. Due to their emergence within the North American trade union movement, they promote corporatist and decentralised decarbonisation programmes, rather than statist top-down approaches. But many of its demands are directed at different levels of public policy and have been promoted by policy elites. Most JT approaches seek to ‘green’ industrial strategy and social policy through public investment, public and occupational earnings-related benefits and job creation programmes to support decarbonisation. Green New Deal packages, which have developed primarily in (and for) North America and Europe by academics, activists and politicians, also remain largely committed to capitalist economic growth but promote large-scale public and private investment in eco-social public infrastructure, services and social protection benefits for most affected workers, similar to those proposed under the JT perspective.

On the anti-capitalist end of the spectrum, both post-growth and eco-feminist approaches, which emerged in academia and social movements, reject capital-driven growth as the primary aim of economic and social policy. Instead, they propose needs and rights-based systems of provisioning, though there is little consensus on what this transformation should entail. Some post-growth advocates explicitly call for a radical transformation of capitalist market economies, while others focus more narrowly on replacing GDP growth with alternative norms. Common proposals across these lines include more redistributive and universal social protection systems, a decoupling of work and welfare, and a greater democratisation of decision-making. Most contemporary eco-feminists are critical of capitalist social protection systems for their reproduction of gendered and racialised class domination but have different ideas for how radically this should or could be changed. Many proposals are oriented towards gradual eco-feminist transformation of social protection such as through more gender-equal and greener benefit systems, while some call for a more rapid and more radical democratisation and greening of public institutions and economic production. We believe that there is a need for further critical comparative analysis of these proposals and their underlying assumptions about the causes and drivers of the climate crisis, particularly how they seek to address existing social and economic inequalities in different institutional and geographic contexts. This could spur the necessary critical utopian theorising that has been long absent from mainstream social policy research (Levitas, Reference Levitas2013). Radical sustainable welfare and eco-feminist approaches offer particularly pertinent questions for this task, but are themselves often too vague in their imagination and strategies for transformation, including how those relate to trends in existing welfare systems. We believe that more dialogue between proponents of different approaches could help sharpen this dimension.

We identify another key difference between approaches in their underlying theories of transformation. Although there is no consensus on what this has to entail (Wright, Reference Wright2009; Williams, Reference Williams2021), we found that our five perspectives commonly include explicit or implicit considerations of which actors have sufficient relative power for supporting the desired transformation, as well as which actors have particular interests in advancing or hindering them. The ASP literature tends to stress fiscal constraints faced by governments and the path dependence of existing social protection institutions (or the lack thereof) more than other approaches. This is grounded in their focus on low- and middle-income states as the main actors of transformation. Focused predominantly on the Global North, many GND and JT proposals identify the path dependencies of carbon-intensive productive sectors, including capital investments and labour dependencies, as central barriers to decarbonisation. Yet like ASP proponents, these two agendas appear to share a belief that most governments have an interest and the capacity to transition towards a decarbonised capitalist economy. The empirical basis for this however remains lacking, as indicated by recent UN warnings over a lack of credible policy plans despite promises (UNEP, 2022). Additionally, all three approaches rarely question the historical origins of the global distribution of wealth and processes of resource exchange, thus risking the reproduction of unjust colonial relations (Tilley and Ajl, Reference Tilley and Ajl2023).

In terms of the collective agents of transformation, JT’s corporatist orientation tends to prioritise tripartite policy concertation and decentralised collective bargaining as part of ‘procedural justice’, but there are more radical proposals of JT which propose militant labour strategies. GND proposals tend to emphasise the prominent role of governments, legislators, and, to a lesser degree, activists. While ‘post-growthers’ and eco-feminists offer various accounts of how contemporary welfare capitalism is environmentally and socially destructive and increasingly propose alternative norms, they have surprisingly little to say about how change towards alternative systems of provisioning could occur. This is particularly troubling in the context of vast research on the neoliberal restructuring of social protection systems in the last few decades (Cantillon, Reference Cantillon2011; Dukelow, Reference Dukelow2021; Bridgen, Reference Bridgen2019), which have shifted many welfare states further away from the universalist norms that these approaches promote. Overall, we find that the theories of transformation of most policy frameworks remain underdeveloped and lack empirical grounding – with the exception of the process-oriented Just Transition approach. Erik Olin Wright’s work might usefully be deployed here too, particularly his suggestion that theories of transformation should provide accounts of why existing institutions are relatively stable, what gaps and contradictions there are which open space for transformation towards identified aims, how such possibilities are likely to develop over time (Wright Reference Wright2009 :27). Certainly, further research on the contradictions and possibilities of transformation is required for the full spectrum of existing eco-social proposals and paradigms.

Overall, our article contributes to growing debates about the politics of eco-social transformation by bringing attention to different ideological dimensions of policy approaches. There are only few who have attempted to theorise this field such as Mandelli’s (Reference Mandelli2022) eco-social-growth trilemma or Zimmermann and Graziano’s (Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020) mapping of institutional dimensions of different ‘worlds of eco-welfare states’. Our analysis raises further questions about the power relations and interests underlying both processes of eco-social policy knowledge production and their political promotion. Most importantly, the constellations of different actors invested in different approaches, such as international organisations with the adaptive social protection agenda, social democratic parties with Green New Deals or employers and unions with Just Transitions raises questions about the power interests at play, and the extent to which historical, geographical and institutional contexts within which policy frameworks have emerged shape their orientation. We should be particularly cautious to avoid the pitfalls of a ‘problem-solving political science perspective’ (Trampusch, Reference Trampusch2004) in which policy actors are functionally perceived to be focused on solving problems rather than advancing their own ideologically formed interests. Understanding the latter requires analyses of the interconnected processes of interest formation and ideology development, a claim frequently emphasised in critical social policy scholarship (Jessop, Reference Jessop2012; Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2013). The fact that some eco-social policy norms such as green job creation or universal basic income are supported by a broad range of actors (and that others are widely opposed) should make us more curious about what shapes such an apparent interest convergence and how proposals differ in their assumptions, design and implementation (Fouksman and Klein, Reference Fouksman and Klein2019). More critical research is required on the actor constellations supporting different policy frameworks and their underlying interests in eco-social transitions, including the roles of academics like us.

To conclude, this article raises a number of potential roles for social policy scholarship in supporting eco-social transitions. We find that there is a need for further developing empirically grounded conceptions of alternative eco-social policy institutions, which can draw on the vast number of ideas emerging inside and outside the academy, and could involve creative labour and prefigurative praxis (White, Reference White2020). Such work needs to be explicit in outlining the underlying analytical and normative assumptions of existing and new proposals. On this basis, the relationship between eco-social alternatives and existing social protection institutions, of various types, should be at the forefront of eco-social policy research with the aim of fully theorising the barriers and opportunities for transformation. Additionally, scholars should further examine the power interests and ideologies underlying different proposals and the coalitions forming around their promotion. Eco-social policy research should also further engage with the insights and questions raised by eco-feminist scholarship to avoid reproducing the masculine universalism underlying so much social policy research. Finally, scholarship could support prefigurative policy experimentation and evaluation of policy outcomes on different groups.

Acknowledgements

We thank the organisers of the SPA Climate Justice and Social Policy Group for their workshops in 2021, which led to the creation of this article.