While seeking work in Mannheim in 1777, Mozart described in letters to his father, Leopold, that a ‘Dutchman’ named Dejean had commissioned what turned out to be the bulk of his solo flute works. This was Ferdinand Dejean, a surgeon in the Dutch East India Company (VOC).Footnote 1 His life story was published in detail recently,Footnote 2 with further analysis of the immediate source of his wealth which came from his wife,Footnote 3 whose first husband had died in Batavia.Footnote 4

There are three lettersFootnote 5 to his father in which Mozart refers to a 200 guilder feeFootnote 6 agreed with Dejean for the commission. He mentions Dejean twice in an Asian context: ‘Unser indianer’ (our Indian), interestingly without thought of racial origin, and ‘Der wackerer Holländer’ (the courageous Dutchman),Footnote 7 echoing the perceived bravery of going out to Asia and surviving against the odds. That Mozart alluded to Asia in two separate letters says something of his sense of wonder about it, and he clearly liked ideas about Asia. In Mannheim one could see images of Asia personified in Turkish dress, with Frankenthal porcelain Continents decorating the Mannheim elector's residence and the giant chancel statues of the Jesuitenkirche. That church was dedicated to Franz Xaver,Footnote 8 later the name the Mozarts gave to their youngest son. This dedication did not occur in the churches of Vienna or Salzburg,Footnote 9 so Mannheim is a potential source for this name in Mozart's mind. He liked the acoustics of the Jesuitenkirche, which, when he visited, had a large ceiling fresco of St Franz Xaver evangelizing in India, and showing him washed ashore after a shipwreck.Footnote 10 Mozart stayed at the Mannheim elector's Schwetzingen, where de Pigage had already begun the courtyard of the mosque, driven by aesthetics and the freemasons’ tolerant principle of belief in any supreme being. The stunning Chinoise decorations of the Bath House had also been completed.Footnote 11 Five years later, Mozart composed Zaide and Die Entführung aus dem Serail, evoking danger, rescue, and the Ottoman exotic. He composed Mitridate re di Ponto when he was 14 from a cast list and libretto based on Jean Racine. These were artistic, dramatic, and romantic ideals of a simplified Asia.

Dejean was unusual, but not alone, in putting uxorial inheritance into intellectual development. For example, Johan Mohr's wife's money from her late husband funded the building of a giant astronomical observatory in Batavia in 1765.Footnote 12 In his portrait,Footnote 13 Dejean is shown with two strong emblems of biblical judgement (Figure 1). This begs the question of whether he was praying he had done enough good, or even expiating some guilt about the source of his income.

Figure 1. Ferdinand Dejean by Jacobus Buys, circa 1780. The emblems of judgement are sheep versus goats, and legs bared or covered. The globe's steel latitude gauge points to Batavia. Source: Kind permission of BDBEC.

Dejean was the financial and intellectual lead in Mozart's commission, assisted by his fellow freemason, the virtuoso flautist Wendling.Footnote 14 Proportionately, though, most of the money for Mozart appears to have been rooted in the wealth of Anna Buschman's first husband, Wilhelm Buschman. For two full trading years he was the VOC upper merchantFootnote 15 and managing Resident on Kharg, before it was abandoned under siege by Mir Mohanna, the ruler of Bandar Rig.

There is already a good précis of some of Buschman's reports to BataviaFootnote 16 on the broader military and political events. Dutch trade on Kharg has been considered from the perspective of the reasons for its failureFootnote 17 and Kharg's general history and archaeology.Footnote 18 There is other discussion of the fall of Kharg.Footnote 19 These publications reasonably leave aside the source of Kharg VOC private profit and the Kharg pearl trade in Buschman's time there as upper merchant. After a broad, introductory review, this article looks afresh at the primary source records of Buschman in the National Archives of the Netherlands (Nationaal Archief, NA), newly digitalized for this study.Footnote 20 We consider the relevant time period in detail, with a forensic accounting eye, while appraising Buschman's behaviour and circumstances.

Wilhelm Buschman and Anna Pack

Wilhelm Johannes BuschmanFootnote 21 graduated in law from Groningen in 1752 at the age of 19.Footnote 22 His father, Jacob, was a Dutch Republican pastor in Elburg, a tolerant old Hansa town, where, in Buschman's boyhood, the Jewish community was already holding services.Footnote 23 Jacob Buschman was a prolific theologian and published six religious works.Footnote 24 Two of them were in print and therefore potential influences on W. J. Buschman before he left for Batavia. They covered the Old Testament, including a 340-page Judaism-facing commentary on Jacob and Moses.Footnote 25

At the age of 19, Wilhelm Buschman published a legal treatise in Latin on the rights of man, which says more about his character and intellect than any VOC transcripts.Footnote 26 It is dedicated with humility and a discernment of moral values to his father and two uncles, namely Petrus, ‘a respected Amsterdam businessman’, and Huybert, ‘a successful, pious merchant of integrity’. His work is thoroughly referenced and analyses human rights legislation, historically and contemporaneously, covering gender, liberty, servitude, marriage, ownership, and inheritance. It shows a good standard of both Latin and ideology. The professional, academic, and moral origins of Buschman in an ecumenical culture are evidence for his extracontractual VOC income being more subcultural, rather than individually psychopathic, for that organisation; there is nowhere near sufficient evidence in summated sources for a generally antisocial personality disorder, even though it was noted that he upset colleagues when in drink.Footnote 27

Buschman married Anna Maria Pack in Bombay in 1755Footnote 28 during his preliminary VOC duties. They spent eight years together on Kharg from 1757, until Mir MohannaFootnote 29 drove them out.Footnote 30 Buschman became an upper merchant in late 1762, tasked with bringing tighter management to Kharg, replacing Jan van de Hulst.Footnote 31

Anna Buschman was highly likely to have been Anglo-Indian. Even by the 1860s, when the concept of marital racial integration in India was at rock bottom, only 6 per cent of British East India Company (EIC) personnel were accompanied by their wives. In the eighteenth century, interracial marriage was encouraged by the EIC, and mixed race daughters almost invariably married soldiers of lower ranks.Footnote 32 For Anna Pack to have married a VOC merchant was a rare chance at extra security after her father, an accountant and warehouse man, died of gangrene in Bombay in 1746.Footnote 33 She had unusual wealth for an Anglo-Indian widow, though less unusual for a VOC widow.

Pearl fishing on Kharg and the pearl economy

The Persian geography Hudud al-'Alam, حدود العالم من المشرق الی المغرب , finished in 372/982, mentioned Kharg as a good source of pearls:

… Kharak lies south of Basra at a distance of 50 farsangs.Footnote 34 It possesses a large and prosperous town called Kharak. Near it excellent and costly pearls are found.

Also, in the medieval period, the Gulf traded pearls with Song dynasty China via Sumatra. In other early Persian references, Kharg had smaller pearl yields than the major sites like Bahrain, Jolfar, Qatar, and Sharjah, but more Yatima pearls of exceptional quality.Footnote 35

Nineteenth-century British accounts record Kharg as having the best pearls in the Gulf and, crucially for the thread of this article, with pearl beds found at all depths, from just below the low waterline.Footnote 36 These depths remain shallow on modern chart data, too. Kharg itself grew its pearl output from the time of the Dutch as a prodromal financial economy, emerging from a subsistence one. In 1907 Kharg had 40 pearl boats.Footnote 37

The Kharg VOC base's founder, self-styled as ‘Baron’ Tido Friedrich von Kniphausen, attempted to obtain six glass diving bells in 1757 to harvest pearls, as reviewed by Floor.Footnote 38 Such work and the accompanying huge costs were not speculative and reflected richer pickings at a faster turnover, based on oyster bed knowledge. Kniphausen said he expected a four-fold increase in productivity. Batavia, however, barred the potential use of diving bells by Gulf locals and they never materialised.Footnote 39 While there is no reason to doubt the potential of the bells, other evidence suggests that the pearl harvest was already going well in secret.

Floor emphasised Kniphausen's drive for personal and VOC profit, including his proposed conquest of Bahrain in 1754,Footnote 40 motivated by the pearls. In recent years Bahrain had been conquered and ruled by Mir Mohanna's father, Mir Nasir. Kniphausen also considered taking Bahrain as an anti-British bastion, militarily and economically. The VOC directors barred him from invading Bahrain, though, preferring consolidation to expansion, which contributed to the VOC's downfall in the Gulf. In 1757, Kniphausen described Simi oysters around Kharg ‘in rather large quantities’,Footnote 41 a statement smacking of deliberate vagueness.

Buschman first appears in correspondence as ‘Under Merchant on Kharg’, writing with Kniphausen in January 1757.Footnote 42 Importantly, Kniphausen's interest in pearl fishing was documented in the same year as Buschman's arrival.Footnote 43 The types of oysters and relations with Arabs were considered, but, again vaguely, there was no comment about absolute quantities or prices. After that, the record about pearls in Buschman's time on Kharg stop dead. It is possible that the pearl beds’ yield around Kharg and the wider Gulf fluctuated, but they could not have died off totally as this would not account for their sudden and time-limited disappearance from history during Buschman's time on the island.

The most revealing accounts of actual pearl activity on Kharg are by the British observers Francis Wood of the EIC in the Persian Gulf and Edward Ives RN. Wood's 1756 account. The latter came from his observations and verbal report from Under Merchant van de Hulst: Kharg was rich in pearl beds. Kniphausen ran diving teams who delivered the oysters to him for private opening, so, central for our argument, only Kniphausen knew how many pearls there were.Footnote 44 Kniphausen recorded his knowledge of the pearls’ potential, citing Bahrain generating Rs 240,000Footnote 45 annually.

Kniphausen tried to impress upon Ives that Kharg's pearl production was limited, obviously exaggerating the depth at which they were found:

Pearl oysters have been found near this island, but as they lie in considerable depths, not less than 13 or 14 fathom water, the divers (who were not very expert at the business) had not met with much success, at the time we were there. Some pearls of considerable value however had been found, particularly one, very handsome and large, which the Baron was so polite as to present to Mr Doidge.

Ives did not indicate if he had even been to the shoreline to see the oyster beds.Footnote 46 Kniphausen also said then that he was keen to learn about diving bell technology from Ives's party, so his interest was genuine.Footnote 47

The VOC realised that pearl cryptocurrency was a problem just over a year into Kniphausen's private pearl activity on Kharg, although the Dutch also sourced pearls off Chennai and Sri Lanka. Sumptuary laws banning pearls worth over 4,000Footnote 48 rand were introduced by the VOC in the Cape in 1755 to control damage from a soaring black market economy rather than to enhance puritanism. A particularly extravagant string of pearls valued at 1,000 rand in the Cape would have bought 66 horses.Footnote 49 That is around £400,000 today, based on modern draft horse prices and consistent with the present-day cost of the highest value pearl necklaces. VOC communities were spending too much money on pearls; the Company and its bases were not benefitting.

Mir Mohanna and the political geography of the Gulf

Mir Mohanna has already been reviewed well and at length in secondary sources, but his interactions with Buschman and role in Kharg's history linked to pearl wealth warrant a recap here. The Mir was a key actor in shaping the demise of the VOC and the future structure of Gulf government. Kharg's location allowed local coastal pearl fishers to trade from a wide area and the political structure of the Arabs who lived around the Persian coastal region at the time lent itself very well to unregulated trading. Carsten Niebuhr, a German scientist on the Royal Danish Arabia Expedition, described the Arabs as possessing all the northern Gulf coast adjoining Persia, and confirmed their ready ability to hide from any trouble on the islands.Footnote 50 Kniphausen's report to the VOC in 1756 described the locals living by navigation, pearl diving and dealing, and fishing. When approached for tax or servitude by Persian court officers, the pearl fishers simply paddled out to sea.Footnote 51 Importantly, too, in terms of the Arabs’ free trade potential, there is a lack of positive evidence, at least in Buschman's early years, that the coastal and island Arabs belonged formally to any other state.Footnote 52 The existence of a distinctive Khargi island language, related to other Persian coastal linguistics,Footnote 53 appears to be rooted in a balance of isolation and maritime territorial dissipation, consistent with Niebuhr and Kniphausen's cultural descriptions of competent, seafaring trade and easy local migration. Such political isolation suited Mir Mohanna.

While Karim Khan Zand was ruling most of Persia following the last of the Safavids, local Mirs between the Ottoman frontier and Hormuz ruled Gulf islands and ports in their own right.Footnote 54 There is a significant gap in their history from their own perspective. Western accounts focus on piracy and extortion, not their day-to-day fishing, pearling, trade, or family life. Perry could only review evidence for Mir Mohanna maintaining devotion from the magnitude of his income.Footnote 55

JacobsFootnote 56 concluded that in 1750 VOC Governor General Mossel was motivated to establish a base on Kharg, not for pearls, but primarily to trade sugar with which to supply Batavia. Fort Mosselsteyn on Kharg lasted for 12 years, with the town population rising to 10,000. The Roman Catholic Bishop of Isfahan even moved his residence there.Footnote 57 Mir Mohanna himself reportedly confirmed Kharg as a Dutch territory in 1753 after Kniphausen gave his father Rs 2,000. Later, he refuted this in support of his claim to take the island.Footnote 58 Kniphausen and van der Hulst were to be proven wrong when they recorded in 1754 that there was: ‘… such anarchy that from that side one has to fear nothing. With regard to the Arabs, they all live in discord with each other and are unable to prevent our plan.’ Kniphausen believed the Khargi islanders appreciated the Dutch for preventing them from being ‘plundered by all passing Arab vessels’Footnote 59 and that Bahrain would be similarly grateful.

Mir Mohanna made himself sheikh of the coastal Al Zaab tribe and ruler of Bandar Rig in repeated coups. After killing his father, Mir Nasir, in 1754, in 1756 he killed 15 family members, including his elder brother, Mir Hussain.Footnote 60 Straightaway Mir Mohanna made a rent demand to the Dutch for Kharg, which Kniphausen refused to pay. Kniphausen was familiar with the details of local history and politics;Footnote 61 the standard of his report to Batavia on the Gulf in 1756 is so well-considered and consistent that his vagueness on the matter of pearls could hardly have been the result of incompetence.

Three years on, a maritime skirmish occurred off Kharg when a Dutch boat beat off two of Mir Mohanna's ships attacking a vessel from Basra. A later attack by 200 of Mir Mohanna's men on Kharg in March 1762 was foiled.Footnote 62 By the time Kharg fell to Mir Mohanna in 1765, it was the last of the Dutch bases in the Gulf, with Bandar Abbas (= Gombroon/Gomron) and Basra already having closed.Footnote 63 Mir Mohanna did not rule Kharg for more than a few months. He was ousted by forces loyal to Karim Khan Zand and reached Basra, but was arrested and executed in 1769 by Karim Khan's governor. His demise was pivotal in Karim Khan Zand gaining control of most of the Gulf coast and cementing the political geography.

Income, death, and inheritance in the VOC

The VOC's pay levels were geared to providing basic comforts (Table 1). Lasting wealth was widely attained by the more senior merchants in a culture of bribes and rake-offs. Sultan al-Qasimi summarised that the VOC Residents bought cargoes and charged the VOC for sales.Footnote 64 Despite many references to foreign ships’ cargoes in the Batavia records, Buschman provides no numerical evidence for this.

Table 1. VOC posts and earnings/florins per month, in Buschman's time under Governor van der Parra.

Source: Beknopte beschryving der Oostindische etablissementen (Amsterdam, 1792).

Buschman's father was comfortably well off in Elburg's pastorie, but there is no apparent notarial evidence that he was rich. Some inheritance from Buschman's merchant uncles is a possibility, but searches have not brought to light any notarial documents of this. If a Dutch legacy to Buschman was a factor in Anna Pack's final inheritance, it was probably still in Europe. Regardless of any undetected Dutch inheritance, Buschman's Asian-generated wealth was immense, as will be demonstrated. Anna would have inherited from her father, but, as a middle-ranking accountant and warehouse man, his opportunities for generating much income beyond his salary were not as great as those of a senior EIC officer.

A 1761 description lists only two merchants on Kharg island outside the VOC,Footnote 65 one a Persian, the other a Jewish merchant with a monopoly to trade sugar and spice into Basra. Buschman had no significant competition on Kharg for trading outside the VOC. He had every opportunity to sell pearls to foreign captains, mostly on British ships, who could, in turn, make big profits.

Samuel van de Putte spent several years touring China, Tibet, India, Persia, and the Malay peninsula, relatively unscathed.Footnote 66 Yet, after arriving in Batavia in 1745, he was dead less than two months later.Footnote 67 Buschman's will, transcribed a few months after he reached Batavia from Kharg on 23 October 1766,Footnote 68 described his wife as ‘Anna Pack, Englishwoman’. They were already officially married,Footnote 69 yet notably the clerk used her maiden name and origin, emphasising the presence of a British affinity. Although in the hand of a Batavia secretary, it was signed by Buschman himself, who died in January 1767, exactly three months later. His handwriting is tremulous and veers off. Neurobehaviourally, it looks as if he was already frail with his last illness when he signed his name. Most premature deaths in Batavia were the result of malaria. It is unlikely that yellow fever existed by then in Southeast Asia,Footnote 70 and febrile jaundice was probably malaria, as were ruptured spleens.Footnote 71 Buschman could have simply died from skin exposure to mosquito bites in Batavia's rainy season, in contrast to healthy Kharg.Footnote 72

Otto BlekerFootnote 73 discovered that when she married Dejean, Anna Pack, Buschman's widow, put a portion of their assets into the Batavian orphans’ fund for her son with Buschman, a sum totalling close to 275,000 florins.Footnote 74 In real wages and real wealth purchasing power today in buying goods or services, that is around £3.46 million.Footnote 75 Bleker discussed how this was legally binding. In his own rightFootnote 76 Dejean had 15,386 florins from left over pay and the sale of goods in Amsterdam, so he had generated an estimated 6 per cent of the declared pot he and his wife had on returning to Amsterdam.Footnote 77 Therefore Buschman's wealth comprised the bulk of Dejean's. Buschman may have been wealthier than Anna declared in Batavia. Nikolas van Maseyk, Footnote 78 the Dutch consul general in Aleppo, reported Buschman leaving Kharg with ‘zijne rijkdomme’, clearly meaning his personal wealth, of ‘drie Lack’, which is Rs 300,000. That converts to £30,000 at the time and roughly a colossal £4.2 million in present day currency. Buschman's hidden assets were obviously converted into cash.

Buschman recorded very sporadic deaths on Kharg (Figure 2), a surprisingly low rate of around 0.5 per cent of personnel per annum for 1763–1764.Footnote 79 That is a massive contrast to the estimate given to James Cook in Batavia in December 1770 when VOC captains reported losing half their crew.Footnote 80 Bruijn identified that most VOC surgeons in Buschman's time did not live to return; 70 per cent died.Footnote 81

Figure 2. Northeast corner of Kharg. The open and dry terrain was a good antimalarial landscape, conducive to lasting survival and lasting embezzlement. Source: ILN, 4 April 1857.

There is a revealing retrospective detail about one death and inheritance on Kharg from 17 October 1760,Footnote 82 when an onder stuurman (second mate) left 3,000 florins. His wage was 15 florins a month.Footnote 83 Extrapolating from that, with adjustment for extra lifestyle costs, Buschman dying at the same age means he would have left approximately 200 times his basic VOC monthly income, totalling about 8,000 florins. Buschman actually left Kharg with two orders of magnitude greater in florins—strong evidence for the size of his extracontractual income. Buschman's extra income could have been shipped back to Amsterdam and banked, but this was not detected in VOC or notarial searches. The implication is that it went as cash and/or assets to Batavia.

The VOC had distinct legal benefits for widows, who were able to inherit property and maintain control over their finances and husbands’ wills.Footnote 84 In the Cape Colony, widows were able to set up households independently of their children, with sizeable inheritances relative to other heirs.Footnote 85 In the Dutch Republic, as well as the VOC, inheritance ethics were progressive.Footnote 86 The egalitarian distribution of property and the strong commitment to the nuclear family embedded in law was strengthened by wills. Dutch widows benefitted more than British women. The VOC also had a relatively outstanding welfare state for orphans.Footnote 87 There was a lot of flexibility in Dutch testamentary law which could be dictated by women. Aasdom law could conversely apportion a child's inheritance to a husband.Footnote 88 It was also common for colleagues to marry VOC widows, with a noticeable small trend for surgeons to marry the widows of other surgeons.Footnote 89

Outsider observations of the VOC on Kharg

In 1758, Edward Ives actually met Buschman and Anna Pack on Kharg. Ives had witnessed Kniphausen disparagingly negotiating a hard bargain to buy camels from an Arab merchant. He threatened to get them from Aleppo instead. Ives tellingly quotes Kniphausen's subsequent comment:Footnote 90

In Europe perhaps it may sometimes be a proper maxim for people to desire to be thought rich; but in this part of the world, all should endeavour to be esteemed poor, for the supposed rich man will ever be imposed upon, and it is out of his power to prevent it. Gentleman's servants also have a peculiar vanity in exaggerating the wealth of their masters, and thereby often put them to an extraordinary expence (sic).

Ives’ very next paragraph brings in Wilhelm and Anna Buschman:

… we took frequent opportunities of visiting our several friends upon the island, particularly Mr and Mrs Bosman, in whose gardens we passed some hours very agreeably, and smoked the Calloon and the Kerim Kan, pipes which are used by the gentlemen here, in the same manner as the Hookah is in Bengal.

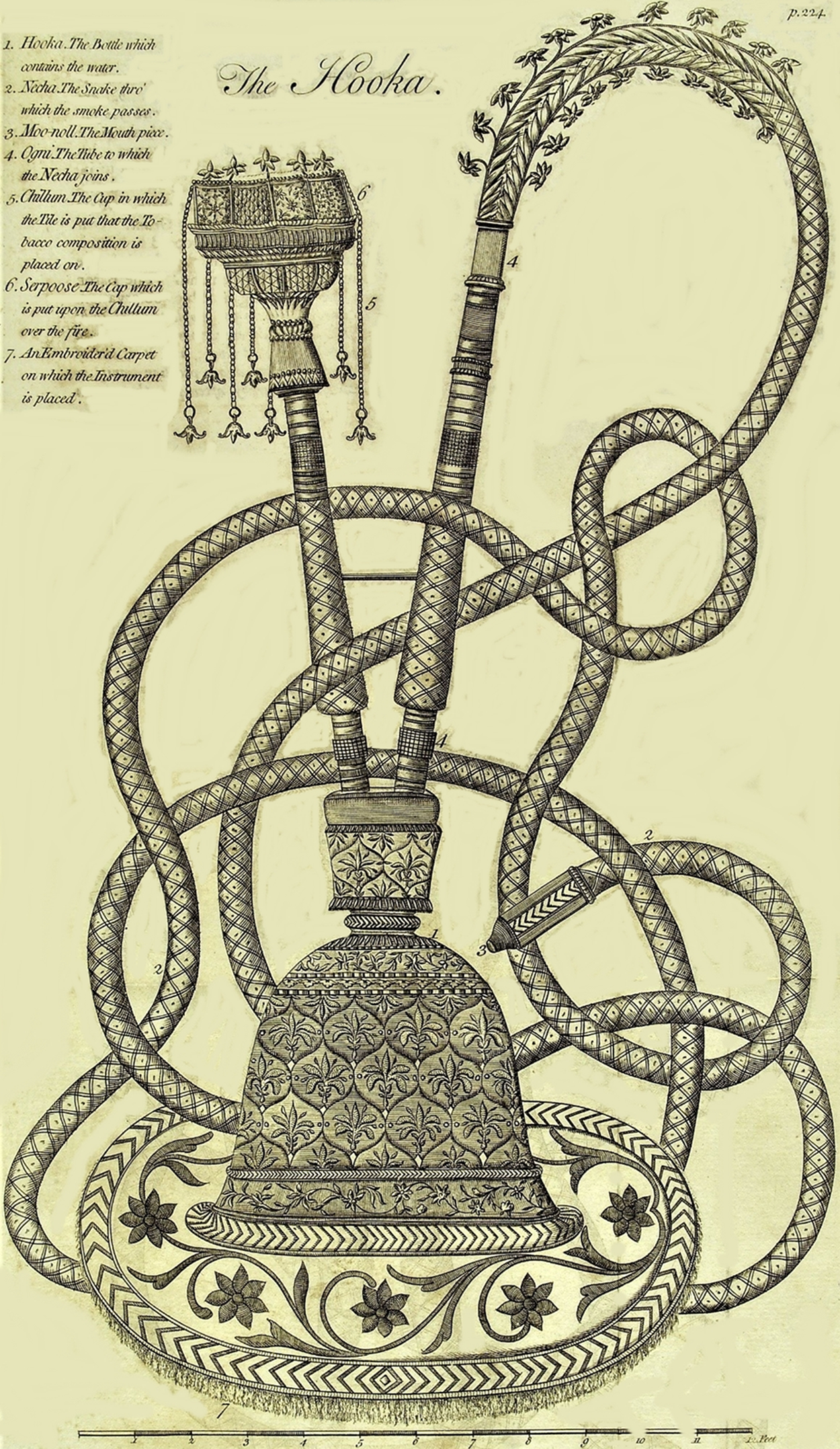

Figure 3 shows a qalyān from one edition of Ives’ book—his Calloon—adjoining his account of the Buschmans. Ives does not stipulate the origin of the Persian-looking pipe in this plate. Did it emblematise cultural affinity and immersion, and actually belong to the Buschmans? There are no clues as to the source of the image.

Figure 3. Persian-style qalyān, with floral narrow base flange, illustrated next to Ives’ description of smoking with the Buschmans. Source: Ives, English edition, 1773. Digitally remastered, the author.

Ives described newly built houses for Europeans and an esplanade.Footnote 91 He was obviously gathering intelligence, because, most unusually, he was still being paid for his five-year trip, after hopping off a naval commission to tour Arabia with unconvincing ‘ill health’. He was later free to publish a travelogue. His insights into Kharg appear to have survived because of the detailed levels of espionage observation transferring into the public domain. Ives described the practice of the British and Dutch at Bandar Abbas (then Gombroon) of siding with no particular trading partners, ‘and sometimes presents have been thought indispensably necessary’.Footnote 92

Niebuhr visited Kharg in June 1765. He said that while he was there Buschman governed Kharg like a small sovereign.Footnote 93 Niebuhr noted that Buschman was law-abiding and respected. He was aware that Buschman's father was a pastor, so Buschman must have told Niebuhr that to give a favourable impression of his character. He described Buschman arranging an intimidating reception for Mir Mohanna's envoy and Buschman's ‘handsome entourage’, with the VOC soldiers at their posts and the sailors shipboard. Buschman sat on a large armchair with his secretary and ensign, ‘und alle seine Schwartzen und die übrigen bedienten’, on both sides of the white-pillared hall. Describing separate groups of ‘all his blacks and the various servants’ implies that the sub-Saharan Africans were slaves. Niebuhr also mentioned that sub-Saharan Africans who had been sold as slaves continued to practise African religions on Kharg under Buschman. That speaks of his religious tolerance, but does not disclose whether they were sold at the Cape, the main VOC slavery centre, or whether this was another trade on Kharg omitted from the VOC books. Unlike the pearl trade, there is no evidence for primary slave trading by the VOC on Kharg at any point. They were almost certainly transported on VOC ships to Kharg from the Cape.Footnote 94

Buschman showed the Arab delegation the fort and the gunposts. Niebuhr described Buschman's characteristic, lively determination. The Mir's envoy placed his hand on Buschman's shoulder saying ‘If you had to give up such a fort, you would no longer be worthy of being Governor here.’ Notably, the word ‘governor’ was used even though Buschman was not one. Either that was the Arab envoy's perception, or Buschman's chosen word fed into the envoy's retrospective account, or both. Niebuhr described a subsequent strong and peaceful trade at Kharg, but, six months later, Buschman's show of strength and swagger did not deter Mir Mohanna.

Wood described the VOC in their last year on Kharg as having two gunboats, 60 European military personnel, and 100 African slave auxiliary troops.Footnote 95 These numbers are consistent with Buschman's 1763–1764 troop costs. He later shed light on a Dutch strategy to settle Chinese in Kharg as a ‘peaceful’ labour force. An element of this must have been to avoid dependence on Gulf Arabs or African slaves with greater potential for conflict and rebellion.

Buschman's reports from Kharg to Batavia

Early years as under merchant

In the year to 1759, the goods traded report by van de Hulst and Buschman does not mention pearls.Footnote 96 The year to 1760 account details individual ships and sale agent involvement, but no pearls.Footnote 97 All this suggests that Buschman's predecessor as upper merchant, van de Hulst, was following in Kniphausen's footsteps trading in clandestine pearls, while Buschman, still under merchant, was learning the trade. The account of goods traded to September 1761 omits pearls.Footnote 98 A lengthy audit of October 1762 contains no pearls.Footnote 99 The 1763 records submitted again by Jan van de Hulst and Buschman show no pearls at all,Footnote 100 nor do the cargo manifests.Footnote 101 The VOC books at Surat, down the chain of VOC harbours in what is now Gujarat, did not record any pearls in Buschman's time.Footnote 102

First full trading year as upper merchant, 1763–1764

Two sets of annotated, annual accounts for 1763–1764 and 1764–1765 span the heart of Buschman's time in the powerful position of upper merchant on Kharg.Footnote 103 This period was his prime opportunity to accumulate personal wealth. Before these two years, the annual record overlapped with his less privileged time as under merchant. From late 1765, the records are incomplete. This analysis of Buschman's business style and accounts begins when the records pertain to Buschman's time as upper merchant, until his departure from Kharg and the closure of the base.

In the penultimate full year of trading on Kharg, from September 1763–1764, the total sugar profits were 103,003 florinsFootnote 104 and Buschman excused that as a poor year. Profits from pepper, steel, and tin were very small in comparison. Buschman would have been very unlikely to rake off something like one-third to one-quarter of the VOC profit to create even a fraction of his lowest-estimated wealth. There was no mention of pearls with those commodities, nor in any other goods lists.Footnote 105 The year after that, in a time of escalating warfare, the total profits for the prime commodity of sugar was down 75 per cent, to only 26,995 florins.Footnote 106 The total of those two years of sugar profits totalled less than Buschman's wealth. Unit prices of the major commodities in the period showed negligible fluctuation. It was simply a flat market,Footnote 107 with trade at a standstill.Footnote 108 He was upfront in justifying his use of the VOC account to pay 23,201 florins for land-based soldiers ‘which has occasionally been provided at the expense of this (budget)’. Another insight without extra justification is the cost of staffing the two VOC ships at 2,512 florins for European marines and more than double that at 6,606 florins for Arab marines.Footnote 109 There was a further cost of 5,700 florins for land soldiers,Footnote 110 after ‘unrest from last year until the end of February’ who were ‘very necessary and needed to be kept on’.

A bribe in the amount of 435 florins, described as a ‘small present’,Footnote 111 was made to an anonymous Arab to clinch a deal, with the justification that the British had already offered a bribe. Buschman also considered debts owed to the VOC by Arabs. First, he wrote an update pertaining to a notorious episode of VOC corruption.Footnote 112 A loan of 7,056 florins made in 1749 to Suliman Pasha by the VOC's Frans Canter had still not been paid back 15 years later. His successor, Ali Aga Pasha, had also not repaid this debt,Footnote 113 and Buschman noted Ali Aga's contemporaneous military expense in suppressing insurgency around Basra. Ali Aga Pasha had insisted that the debt had already been repaid.Footnote 114 In 1750, Canter owed 32,271 florins to the VOC and Buschman records that sum as still outstanding. The Dutch had always struggled to control corruption. Frans Canter was summoned to Batavia from Basra for trading misconduct in 1750. He escaped by fleeing the VOC's jurisdiction to the protection of the Amsterdam burgermasters.Footnote 115 This was a paradoxical sanctuary and a stark contrast to Robert Clive and Warren Hastings facing the London liberals, when Edmund Burke had rehashed the quote of good people doing nothing. Why the good people of Amsterdam did nothing in Canter's case is evidence of efforts to maintain civic power, independent of the global monopoly of the VOC. It was not puritanism. Buschman's writing also redirected the focus on guilty behaviour away from himself.

In addition to Canter's two bad debts, Buschman recorded that the family of Mir Nazier, lord of Bandar Rig, had failed to settle debts from 1754 with the VOC. To recap, Mir Nazier was later killed in July of that year by his youngest son, Mir Mohanna. A British reportFootnote 116 said that the trigger was when Mir Nazier gave one of Mir Mohanna's most beloved concubines from Georgia to the Dutch at Kharg. Only the previous year, Mir Nazier had offered Kharg to Kniphausen and Batavia had clinched the deal. What started as a family power struggle eventually escalated into an all-out Arab civil war with Shiraz. Mir Mohanna's debt to the VOC might have been a potential lever in later negotiations with him by Buschman. Despite that debt, though, Buschman still gave Mir Mohanna a bribe mentioned later in the 1764 diary, with his studied excuses of ‘in celebration of the peace’ and ‘unavoidable, given the local customs’.Footnote 117

On 17 August 1763, the VOC ship Amstelveen ran aground in fog and heavy seas off the coast of Oman, bound for Kharg.Footnote 118 Buschman reportedFootnote 119 that some of the Amstelveen cargo was handed over to local Arabs at the urgent request of Ali Pasha of Baghdad to keep the peace. Buschman blamed poor trade progress on the loss of the Amstelveen. He also made a case that the loss was offset by profitable sales from the cargo of the Rebecca Jacoba van Rustwoude.Footnote 120 Buschman told Batavia that the British were trying to exploit the supply gap from the wreck and bring in lots of goods.Footnote 121 The VOC counter-strategy was to attempt to sell more sugar to Basra. Sugar prices went up, helpfully, as the British had no competitive sugar stock, but Buschman expressed his anxiety to Batavia that the price might not hold: ‘Don't blame me for that. They can't always be the same.’Footnote 122 He also discussed the shawl cloth trade, but there was no mention of pearls.

The VOC base in Basra had closed in 1753 due to a dispute with the Ottomans. Ten years later Buschman was still describing residual stock from the Basra closure in Kharg. He added that some off-loading was done ‘to lighten the load’ and that he was ‘not sure where some of the items went’. Not all of the Basra residue could be sold.Footnote 123 Buschman showed courtesy in asking for permission to be reimbursed for giving provisions to a particular captain. A final table covers Persian goods and rosewater, but there is nothing about pearls.Footnote 124 He also kept Batavia informed about regular contact with Mir Mohanna's merchants coming onto Kharg, but did not describe specific goods. There was no mention of pearls or bribes passing in either direction.Footnote 125

Between 5 September 1763 and 21 August 1764,Footnote 126 24 foreign ships were recorded at Kharg. Fifteen of these were British and basic cargo lists were done for seven of them. They carried sugar, some originating in Bengal or Cochin (Kochi), and tin, iron, and steel. The records described sailings between Colombo, Bombay, or Surat and Basra, or Bandar Bushehr (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Gulf trading bases, settlements, and political centres, second half of the eighteenth century. Source: The author.

It is notable that in the Batavia diaries attention is given to British activity, while there is nothing on VOC merchants’ personal activity. The under merchant who preceded Buschman documented English and Arab ships in more consistent detail than Buschman, in particular the cargo details and quantities.Footnote 127 Some of Buschman's reports on British activity are annotated with lines in different ink in the Batavia diary, so VOC headquarters were paying close attention to the EIC.

On 29 August 1764, Buschman addressed a letter in very good French to Peter Wrench, the British agent in Basra, complaining about a British party chasing Persians around the VOC lodge, hitting doors and windows with axes, and setting fire to gun platforms.Footnote 128 There is no log of any taxes on cargoes or harbouring fees by Buschman. It is fair to assume that as he knew the captains' names, he had every opportunity to levy them. If he did, though, it is hard to see it generating his massive fund.

The final trading year, 1764–1765, until evacuation

Buschman finalised accounts to Batavia for September 1764–1765Footnote 129 only at the point of evacuation from Kharg in December 1765. These were incorporated into the May 1766 Batavia diary with his report on the fall of the base to Mir Mohanna. The goods traded, with profits for the VOC's last full year on Kharg, are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. VOC goods traded and profits, Kharg, 1764–1765.

*Mace is a strong spice from nutmeg husk for medicine and flavouring.

†Benzoin is Styrax tree resin for incense burning.

Source: NA, 3184, pp. 38–39.

There is no mention of pearls. Additional itemised goods, including 447 shawl cloths and 570 items of bedclothes, were sold at a small loss. Other profits from waist bands and lapis lazuli pigment totalled just 40 florins. Buschman explained that goods were sold at a loss due to trade paralysis.Footnote 130 It is interesting that the items sold at a loss during the rebellion were domestic luxury objects, potentially explicable by a wartime fall in demand, but also convenient for extraction from stock as gifts or personal stowage.

Table 3. Goods evacuated from Kharg, December 1765.

*Noted besides Buschman's table. Rosewater was used for food flavouring, perfume, and blessings.

†Sappan wood yields red dye.

Source: NA, 3184, p. 31; NA, 3184, p. 30.

After fleeing Kharg under siege in May 1766, Buschman had to document the goodsFootnote 131 that had been stowed on the VOC ship Walcheren under his direction amid the urgency of the evacuation,Footnote 132 and those that were already on board the Kronenburg (Table 3). The inventory is simple, but of convincing financial and quantity detail, consistent with other tables. It must have reflected Buschman's expectation of exceptional scrutiny from Batavia, given the catastrophic loss of the other assets. Buschman emphasised the excuses of the defeat of the small island and the fear of a new attack.Footnote 133 He documented the salvage of 53,976.12 florins in cash. The stock of salvaged powder sugar alone amounted to nearly 1.9 million pounds in weight. There is no record of how much sugar remained on the island. The total weight of powder sugar sold in the previous complete trading year was 293,380 pounds. In the evacuation, the VOC had removed over six years of saleable material, at the recent rate of sale. The lost trade opportunity was huge. Importantly, though, the last year of VOC sugar profit amounted to only a modest portion of Buschman's wealth. The final year's total VOC Kharg profit was about half of Buschman's apparent final Asian wealth. Again, it does not fit becoming rich on bribes and rake-offs from the transparent commodities.

In the last full year of trading, it cost 58,292 florins to run Kharg Island, including ship and building repairs, heating, lighting, food, and wages;Footnote 134 15,700 florins went on pay for temporary Arab seamen. On this, Buschman was careful to clarify:Footnote 135

… the expenses of Moorish seafarers for which the regulations do not say anything, of which some were shown in greater detail from the added statement of accounts among the attachments.

His concern to cover his back reveals something of the VOC view of money going to Arabs. There is also a rare insight into VOC hospital costs:Footnote 136

Hospital expenses, medications used, linen for bandages, bed linen and what was provided according to specifications further submitted for the purchase of fresh and energising food: 1874.8 florins.

That hospital budget was only down 27 florins from the previous year. It was not raided to fund trade losses and it stands as a credit to Buschman that he preserved the expenditure on healthcare.

Buschman was upfront about spending 905 florins for a ducal receptionFootnote 137 and a bribe, described as a ‘Gift bill for a small present’, to the Armenian Sarkies of 447.7 florins (Sarkies was the Shiraz trade envoy).Footnote 138 Notably, bribes in went to the merchants, bribes out came from the VOC funds. There are no accounted incoming ‘gifts’.

The expenses are carefully accounted for in the profit and loss accounts and are consistent with Buschman's later textual description in the diary. Once more, even with the highest conceivable percentages as bribes and rake-offs, his money had to have come from something else, something hidden.

Weight for weight, the value of pearls was far more than that of sugar, tin, wood, or spices. Pearls are much easier to stow and carry, well-suited to personal baggage. There is no mention of pearls in the evacuating ships’ cargo. There is mention of Buschman getting on board quickly, though, ‘in case the ships left’. That must have been with his wife, son, and baggage,Footnote 139 including his cash, reported to Mareyk at the VOC's Aleppo consulate by some unknown astute observer. Buschman was at pains to excuse the escalating trade failure:

It is to my eternal regret that the profits have been small, caused by the bad circumstances mentioned above, which no human being could have foreseen or known about.

He also emphasised ‘my tireless attempts and vigilance, to which my ambition and the interests were united’.Footnote 140 There is also one rare example of Buschman politely asking Batavia to leave some goods on his account, at their discretion.Footnote 141 It refers to 80 carabasse storage bottles of rosewater, worth 1,280 florins. He separated the account of the rosewater from the rest of the table in the Walcheren inventory, perhaps making the peripheral labelling assist him in deflecting the Batavian directors’ focus. The rosewater was less than 1 per cent of his minimum apparent wealth generated on Kharg. Again, Buschman's money must have come from something hidden.

Siege and abandoning the island, December 1765

Kharg was significant to Mir Mohanna. In 1754, he had forced his elder brother Mir Husain to seek refuge there.Footnote 142 In Buschman's time, Mir Mohanna attacked Kharg itself twice. He actually seized Dutch gunboats on blockading the base in 1762.Footnote 143 Buschman himself negotiated the settlement. After Mir Mohanna attacked again in December 1765, which led to the Dutch giving up the base altogether, Kharg never returned to lasting European control and its population was greatly reduced until the oil boom of the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 144

The complexities of Mir Mohanna's violent rise to power and overthrow of Kharg came to Niebuhr's attention. Just before Buschman's eviction, a British ship tackled Mir Mohanna head on, alongside what can be seen as Buschman's masterly inactivity in only firing warning cannon shots. Buschman had recently done a deal with Mir Mohanna to camp and graze on neighbouring Khargu Island,Footnote 145 appearing to accept it as the Mir's refuge from Shiraz and not suspecting hostility from him. Opportunities for bribes to Buschman were there and they were certainly in contact. Not surprisingly, though, those crucial details are not on record.

At the point of the VOC surrender, Mir Mohanna had taken up menacing positions on sea and land. Buschman described these in the Armenians’ houses outside the bastion of the town; they also had multiple cannon batteries and small guns. A few months previously the envoy had certainly worked out how to vanquish Buschman.Footnote 146 Buschman boarded ship as the town became entirely surrounded. The two VOC ships Walcheren and Kronenburg were completely cut off from land access by Mir Mohanna's large, armed fleet.Footnote 147 Knowing that the attackers had scaling ladders, Buschman described ‘great morosity’ among the European and Moorish residents of the town. His colleague van Houting came out from the ramparts to negotiate surrender terms under a white flag. Some records were left behind with the goods. Buschman wrote defensively to Batavia that:Footnote 148

… with the unforeseen siege and the thwarted correspondence, the papers drawn up from that, and made ready to be sent on with the ship Walcheren, remained at the office, which the expected resident Houtingh will do me the satisfaction of confirming, and which could also be indicated from his letters.

Kharg was a sizeable VOC town, fort, and trading base (Figure 5). Succumbing to a menacing and far bigger Arab army and navy than the VOC had under Buschman was, therefore, inescapable.

Figure 5. Plan of the VOC fort, warehouses, and Kharg town, northeast corner of the island, the site of modern Khark. Source: Niebuhr, Dutch edition, 1776, Table 38.

It is possible that Mir Mohanna, from existing knowledge and having got wind of Buschman's wealth, seized Kharg to control its pearl trade. Arguably, Buschman and Mir Mohanna were both actors in the slow genesis of commerce in modern Kharg. On the other hand, it was doing well in the tenth century. One view is that a few driven individuals like Buschman were the only source of success on Kharg in the first place,Footnote 149 and the Dutch were inflexible in their dealings with the Gulf Arabs, leading to the failure of their expensive enterprise. Jacobs argued that the VOC failed because it did not take corruption in hand, and that corruption was a constant factor, not a clear precipitant for decline.Footnote 150 That view fits a more nuanced consensus—that the VOC could not compete against the tighter-managed and later Napoleonic-militarised EIC,Footnote 151 though they too had struggled in the Persian Gulf.

Pearls on Kharg emerge again in records very soon after Buschman. When Mir Mohanna fled Kharg himself in 1179/1766, soon after the Dutch, an Armenian Shiraz official reported that he had left behind ‘many pearls’.Footnote 152

Conclusion

Was the VOC funding Mozart? We already have a good idea from Bleker and Steins’ work that the answer is ‘yes’—in part and indirectly. The findings here substantiate that around 94 per cent, if not more, of the source fund paying Mozart for his flute compositions came from Wilhelm Buschman's Persian Gulf activity. Dejean might still have sponsored Mozart out of his personally generated funds, but he was a lot richer due to the Buschmans’ money and uxorial inheritance. Without Anna Pack it would have been harder for Dejean to commission so many fine compositions. Buschman left Kharg with so much cash that some of his wealth may have been undeclared in Batavia, though it was similar to the sum in the Batavian orphans’ account, which is helpfully consistent. That similarity also gravitates away from much of the money we know Anna had banked in IndiaFootnote 153 which came from her father. Buschman could have hidden the possible £600,000 discrepancy somewhere else, such as India, in his wife's name on the way back. Equally, Anna's wealth declaration may have been accurate, with any discrepancy being within conversion or an estimate error. Whatever the case, a sum of over £4 million gravitates even further away from bribes, rake-offs, and declared commodities as the source. Buschman had more wealth than the whole of the annual Kuwaiti pearl output. It is credible that the sum derives from Kharg pearls alone. That Kharg is an island, with a clear geographical reference point and a boundary for a set of records, has helped this article; it is a historian's test tube.

The professionalism and detail of Buschman's diaries are rich and informative; there is still scope for more to be published on it. To the VOC, personal business conducted by its senior merchants was regarded as an entitlement, not theft from the company, even though it was technically illegal. Why it was ever criminalised to the point of arrest is also a matter for further research; the sums of money described by Buschman in the case of the criminalised Frans Canter were only a fraction of Buschman's minimum likely wealth. Details of treading on someone else's toes are rarely recorded in history, as the offended party naturally hides reasons for their anger and embarrassment.

You rarely need to look far beneath the surface in eighteenth-century research for slavery to appear. Huge numbers of sub-Saharan Africans were traded in the Cape by the VOC. Comparing the Arhuysers pay rates with Buschman's accounts and the reported numbers of military personnel, they were paid half to a quarter of the pay of the lowest VOC ranks. They laboured under despicable ethics and were not free to leave. Buschman paraded slavery and was accustomed to it; he was probably culture-bound, but not clinically psychopathic. Ironically, the VOC lost out vastly to having a slave militia, which, in apparent wisdom, never fired a shot under attack.

Buschman's writing indicates that he was officially dutiful, busy, and organised. The magnitude of his wife's eventual inheritance indicates that he applied the same attributes to his personal benefit. Niebuhr proved Buschman could be assertive and swanky, but he also verified that he kept to social norms and was not psychopathic. Transparent commodities on Kharg, including sugar, spices, cloth, dyes, and scents, were available for achieving additional income in bribes and rake-offs. To generate Buschman's wealth it would have been dangerous to take a massive percentage from the VOC's official goods, especially in hard times. Buschman would have risked being treated as another Frans Canter had he done that. Nevertheless, some personal factoring in goods sales by Kharg merchants may not have been recorded in order to conceal evidence. Buschman's platitudes to Batavia on his modest stock of evacuated rosewater were an obvious smokescreen in overall context. With the extraordinary original wealth involved in the Buschman-Pack-Dejean-Mozart fiscal trail, there had to be more to it than income from transparent goods.

Low volume, high value pearls are the only reasonable explanation for generating such huge sums in just over two years, helped by a position where Buschman was perceived as a sovereign. Nothing suggests precious metals were covertly traded; although their prices were defined, they do not figure around Kharg before, during, or after our period of interest. Pearls vanished from the records in Buschman's time for no plausible climatic, seismic, ecological, or global volcanic reason. They instantly reappeared with Buschman's Persian successor, Mir Mohanna. Military expansion by Mir Mohanna formed continuing threats to and opportunities for Buschman's personal profits. From wider evidence, it is not convincing that Buschman's predecessor, Kniphausen, maintained that pearls were hard to reach. He was obviously trying to put Ives off the scent in several ways: greatly exaggerating the pearl bed depths, talking of poor success, and implying new inventions were crucial. He also actively sought to dispel any potential evidence that he might be wealthy. Kniphausen's secret pearl activity was documented coincidentally by foreign observers in likely intelligence gathering, when they could travel in relative peace. In Buschman's time as upper merchant during Mir Mohanna's campaign, foreign observation of VOC merchant pearl activity was even less likely. Buschman probably had no records, was unobserved, and had a pearl monopoly.

In the author's professional experience of modern international fraud, it is still very difficult to get the complete picture; hence, there is nothing trickier in history than when someone has actively covered their tracks. Buschman had the intelligence and the opportunity to succeed. He completely compartmentalised his private trade from official VOC business, certainly in practice and possibly in mental denial. Kharg's natural, anti-malarial landscape was a fortunate coincidence, allowing Buschman to survive long enough to become rich. Pearls can be seen as the eighteenth-century equivalent of the compact, high value 500 Euro note to today's money launderers. Also, it looks like the principle of Do not steal an item from a box, steal the whole box; it is a lot less likely to be noticed. With Gulf pearls at one end, Batavia in the middle, and Mozart at the other end, history seldom has such colourful forensic audit trails. The reality was more dramatic than the art and the operas.

Conflicts of interest

None.