Student riots were a constant thorn in Habib Bourguiba’s side during his long and authoritarian rule in Tunisia (1956-87). The Tunisian president is known for setting up an autocratic regime centered around his person, known as al-Burqibiyya or le Bourguibisme, which saw with suspicion any potential competitors.Footnote 1 On the other hand, Bourguiba is fondly remembered for spearheading a secular and modernist project that included considerable investment in youth education and the promotion of equal rights for Tunisian women.Footnote 2 Bourguiba spoke consistently to his people about his vision for a new Tunisia, explaining that it rested on the shoulders of the educated classes, the professionals, and the university students. Yet, when the political scientist John Entelis polled Tunisian university students in 1972, he found that most respondents considered themselves apolitical or supported leftist groups rather than the state's ideological line.Footnote 3 In that survey, and among other contemporaneous observers of Tunisian politics, the Perspectives Tunisiennes movement, or Afaq Tunisiyya (henceforth Perspectives), was the most frequently cited group by university students as an alternative to the regime.Footnote 4

Created in the early 1960s, Perspectives attacked the Destourian regime for espousing socialist principles in name only in its “Destourian Socialist” nation-building program, while maintaining a diplomatic alignment with the imperialist camp, concentrating power in the hands of the petty bourgeoisie, and infantilizing the Tunisian people.Footnote 5 As Burleigh Hendrickson has noted, Perspectives belonged to a constellation of new Arab Left movements that shared a theoretical imaginary that included solidarity with the Vietnamese and Palestinian struggles. Perspectives was connected to French radical networks as a legacy of the colonial experience harnessed during the worst periods of the Tunisian regime's repression.Footnote 6 The movement is synonymous with the 1967 protests in downtown Tunis following news of the Arab military defeat by Israel, and the subsequent 1968 “Tunis trials,” when scores of activists and university students were arrested, tortured, and jailed arbitrarily. Many Perspectives members took refuge in France, where with the support of Tunisian students in Tunis they published their eponymous journal, which was then smuggled back into Tunisia. Tunisian leftism, like other Arab leftist movements, appeared to lose ground to Islamist opposition in the following decades, starting on university campuses, until the Islamists became Bourguiba's, and his successor Zinedine Ben Ali's main opposition.

After decades spent languishing on the margins of historiography, Tunisian leftism has been steadily revived, first by the Temimi Foundation's Siminar al-Dhakira al-Wataniyya wa-l-Tarikh al-Zaman al-Hadir (Seminar on National Memory and the History of the Present Time), then by the post-2011 Tunisian truth commission and published memoirs of the former leftists themselves. A core feature of these testimonies and revived memories has been underlining the symbiotic relationship between the Left and university students, which brings the Tunisian leftist experience into the mainstream of Tunisian postindependence history.Footnote 7 The two saw their interests intersect most notably in the demand to secure the independence of the student union, the Union Générale des Étudiants de Tunisie (UGET). The union was established in 1952 and played a leading role in the nationalist struggle for independence from France alongside the neo-Destour party. After independence, the UGET lost its autonomy due to Destourian party-state meddling, as the latter asserted its hegemony by co-opting autonomous organizations such as the powerful workers union (Union Générale des Travailleurs Tunisiens, or al-Ittihad al-ʿAm al-Tunisi li-Shughl).Footnote 8 The Perspectives movement was itself established by disgruntled Tunisian university students in Paris who, upon their return and as young professionals, ensured the organization filled the gap left without UGET by espousing student issues. These ranged from better living conditions and stipends, to input on the curriculum and university management, to expressing anxieties about future employment prospects.Footnote 9 Perspectives harnessed the energies of students who, in turn, anointed Perspectives as a truly radical organization standing in opposition to the Bourguiba regime. In August 2021, this student activism was commemorated, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Korba Congress of the Tunisian student union in August 1971.Footnote 10 At Korba, the small seaside town hosting the student congress, a coalition of radical and pan-Arab students led by Perspectives managed to secure a majority, outnumbering regime sympathizers. Emboldened by their success, these radical students launched a nationwide protest movement on 5 February 1972 (which became known as Black Saturday) that was violently put down by the authorities. In its wake, scores of students and Perspectivistes were arrested and jailed between 1973 and 1975, effectively ending the movement.Footnote 11 The increased focus on Korba and Black Saturday speaks to attempts to reattach silenced histories of the Left to national history.

In this article, I argue that the student question was more than a tactical alliance about material demands and UGET's autonomy, but rather a fully fledged political counterproject for postindependence Tunisia. Bourguiba stood at the helm of a reformist state deploying a bourgeois and French-inspired political program that believed in the “educability of the national subject,” a belief commonly found among Arab nationalists, while he repeated colonial tropes about his people not being ready for politics.Footnote 12 As a radical alternative, the student question was fleshed out in the journal of Perspectives, in which the students envisaged Tunisian social emancipation emanating from their struggle. The Perspectives political project was never fully formulated, since the movement was led by students and worn down by repression, but some salient traits appear. Perspectives demanded their generation's inclusion and autonomy from their predecessors’ interventionism by deploying the prevailing vocabulary of political critique found across different contexts in the global South to define and envisage a Tunisian social and political revolution. As opposed to Bourguiba, who infantilized the Tunisian people, the student question recognized the Tunisian subject's intrinsic entitlement to autonomous citizenship and political participation (rather than these rights being contingent on modern education and alignment with Bourguibist principles). Perspectives’ resistance project embraced ideological principles of the New Left, but it also was a reaction of the country's emerging intellectual elite to being excluded from defining Tunisia's independent future. Rather than assessing this movement's leftist theoretical credentials, I read this alliance between Perspectives and the student body as a landmark moment in the country's postindependence history and politics. As Mohamed-Salah Omri argues, Perspectives began to conceptualize a modern Tunisian citizenship that would underpin the democratizing drive of civil society organizations in the ensuing decades.Footnote 13 This article accepts the invitation of Sune Haugbolle and Manfred Sing to “deprovincialize left histories” by recognizing not only their global entanglements but also the complex forms of adaptation to local contexts and, I would add, their imbrication within national histories, and by highlighting their forms of theorization through praxis, which live on in the unfolding genealogy of Tunisian radicalism.Footnote 14

Revisiting the student question provides an opportunity to reconstitute and elevate the theoretical labor of the Perspectives movement by drawing on its journal, published from 1964 to 1970 (volumes 1 to 25).Footnote 15 The article portrays this as more than a rebellious movement beset by ideological bickering, or a series of protests, and rather as a collective demand for agency forged in the fire of regime repression. Reading these volumes complements what Amy Aisen Kallander has depicted regarding the polemic on women's miniskirts and men's haircuts of the same period, which evoke a rejection of the state's vision of a “useful youth” as a “catalyst for fears about gender roles, youth culture, the nuclear family, women's employment, and public space.”Footnote 16 In this case, the journal's articles gradually embrace students as more than primary forces for change, rather as the vanguard of a radical social project opposing Bourguibism (and opening the door for a new look at the imagination of student movements and the New Left across the Maghrib).Footnote 17 From these conditions emerges a new type of militant profile that has been under-theorized in existing scholarship on the New Arab Left. We focus on those who were neither fully fledged intellectuals, nor professional activists or guerrilla fighters, but rather university students, who were often elevated too soon within leftist movements. Through their praxis, they advanced the theoretical project of the New Arab Left.

Memoirs of these leftists represent a fruitful source to complement more traditional archives, as shown in the case of Egyptian leftist Arwa Salih, who similarly began her years of activism in Egypt's university student movement.Footnote 18 In the Tunisian case, these memoirs allow us to identify a clear trajectory of engagement from student ranks to leadership of the Perspectives cells, accelerated by the 1968 “Tunis trials” that left a vacuum in the movement's leadership, and they speak to the multiple experiences of militancy within the movement. I rely on two memoirs from the pre-1968 leaders: Gilbert Naccache's Qu'as-tu fait de ta jeunesse (What Have You Done with Your Youth, 2009) and Mohamed Charfi's Mon combat pour les lumières (My Fight for Enlightenment, 2008), alongside those from their post-1968 successors: Fethi Ben Haj Yahia's al-Habs Kadhab wa-l-Hay Yarawah (Prison Is Deceiving and the Living Will Return, 2009) and Mohamed Cherif Ferjani's Prison et Liberté: Parcours d'un opposant de gauche dans la Tunisie indépendante (Prison and Freedom: Trajectory of a Leftist Opponent in Independent Tunisia, 2014). These memoirs demonstrate how university struggles created shared experience and reference points and allow us to speak of a distinct political generation.Footnote 19 At the same time, these four male-authored memoirs reflect only their availability as literary sources rather than the identity of the Perspectives movement, which was built on principles of gender equality, and for which a great number of female members were arrested, tortured, and jailed.Footnote 20 Only recently have memoirs of female leftists been published in Tunisia; these will continue to broaden and enrich this research.Footnote 21

The article moves from the formulation of the student question and the radical atmosphere of the early 1960s in Paris to the successful implantation of the Maoist branch of Perspectives within student ranks in Tunis. This set up a confrontation with the Bourguibist national project for students that culminated in the 1967 protests and 1968 trials. In the ensuing years, the Perspectives project faltered as the movement focused on survival and student agitation until their near takeover of UGET at the 1971 Korba congress. As I follow the trajectory of two individuals from student ranks to leadership posts within Perspectives, I attribute this movement's ability to regenerate after 1968 to the afterlives of the student question within university spaces, ultimately showing how these ideas on Tunisian emancipation lived on through Bourguibist hegemony.

Maoists and the Gestation of the Student Question (1963–66)

The Tunisian student question was born out of the Tunisian regime meddling in student affairs in the early 1960s and reached its culmination with the Maoist turn of the Perspectives movement a few years later. In 1963, Tunisian embassy members and pro-regime students rigged the UGET Parisian cell elections. The incident of the “confiscated ballot box” began when they caused a commotion after the voting ended, and the Tunisian embassy representative stepped in to ensure “appropriate counting of the votes,” all seemingly intended to prevent leftist Tunisian students from winning the election.Footnote 22 There were about twenty to fifty supporters in this splinter group, as Charfi recollects, many of whom had cut their teeth in the Trotskyist and Maoist groups of the French capital.Footnote 23 They decided to rally their fellow Tunisian students to establish a discussion group called Groupe d’Études et d'Action Socialiste Tunisien, or GEAST (Tunisian Group for Socialist Studies and Action), meant as an alternative to UGET. They founded the journal Perspectives: Pour une Tunisie meilleure (Perspectives: For a Better Tunisia), and a few years later they would drop the GEAST name and be known only as Perspectives.Footnote 24

At first, GEAST was a loose group with varying levels of commitment and coexisting ideological views. The group was led by Mohamed Charfi and Nourredine Ben Khedher, two older Tunisian students, who combined friendship and political commitment. It also was common for couples to be active together or to form as a result of these activities, as happened with Charfi and Faouzia Rekik. This group of students was in France thanks to the Tunisian government's scholarship program to train future administrative managers (the cadres), since the French diploma continued to be prestigious after independence.Footnote 25 In fact, GEAST members saw themselves as the successors to Bourguiba's nationalist generation, the majority of whom had studied in Paris in prior decades. Joining the Parisian UGET cell was a conventional entry point into national political leadership, with UGET presidents usually becoming ministers later on, but these political careers demanded total ideological allegiance to the ruling Destour party.Footnote 26 Instead, GEAST drew on radical leftist intellectualism in Paris and the principle of ideological pluralism: in the journal's first issue, the students introduce themselves as “modest” and “not a party organ” that was structured in any way. They only sought to “view clearly . . . Tunisian reality.”Footnote 27 Gilbert Naccache, who later joined the movement, described the early stage as a “revolt against all forms of authority . . . and [attempt] to capture the world of youth that is systematically ignored while seeking to express how they see the future of their country in which they want to be active participants.”Footnote 28

In those early Parisian years, GEAST lacked a clear mission statement, and the journal covered a wide range of topics from 1963 to 1964. Alongside a few editorials on recent political developments, the journal contained long studies that were reminiscent of the neo-Marxist and leftist critique found in study circles on the Left Bank. They addressed Tunisian development policies and agriculture, analyzed the national bourgeoisie and the structure of power in Tunisia, and reported on events in Algeria and Tunisia, displaying transnational Maghribi solidarity.Footnote 29 They also criticized Bourguiba's regime by denouncing his poor management of the Bizerte crisis in 1961.Footnote 30 They claimed emphatically that the state's “Destourian socialism” was a sham and that the state had “failed its historic mission.”Footnote 31 Despite this virulent language, the regime appeared unbothered by this discussion group abroad, believing that the nationalist elite and GEAST members had more in common than any differences with each other: they were both francophone, often of middle-class social origin, and shared modernist social values on such issues as education and gender reform. During this gestating phase of the GEAST group, it was deeply entangled in the transnational imagination of the New Left and radical student politics in the French capital, building those networks that served it well during subsequent repressive episodes.Footnote 32

Students gave GEAST the ideological focus it sorely needed. The journal began with articles demanding UGET's institutional autonomy from the Parti Socialiste Destourien (Destourian Socialist Party) and the regime apparatus that had engineered the election of loyalist leaders and directed committees in all its cells (domestic and foreign). GEAST questioned UGET's purpose, since it was unable to defend student interests from the regime. Journal contributors wrote about themselves and their attempts to win the Paris cell elections in 1963, noting that there had emerged a “progressive wing” within the student body that sought to challenge the “neo-Destourian wing.” They claimed that their leftist radicalism was a mirror of the country's growing concerns. In other words, GEAST members saw themselves as an avant-garde that felt compelled to choose between “mission or resignation,” demonstrating that students could lead the way in revamping Tunisian politics.Footnote 33 In later issues of the periodical they continued to rail against student organizations for their dependence on government for financial support and for seeking to discredit and break from the coalition of North African student unions in France (AEMNA), where leftist Tunisian students were able to gain access to the executive council and threatened to undermine the Tunisian authorities.Footnote 34 The journal attacked UGET's twelfth national congress in August 1964 in Tunisia, devoted to “our contribution to the achievement of independence: training national managers” (notre contribution à l’édification de notre indépendance: la formation des cadres). GEAST members did not attend the gathering, since they failed to be elected the year before in the Parisian cell, but they interviewed an anonymous delegate who spoke about the atmosphere and the UGET congress decisions. This delegate highlighted the lack of consensus, as opposed to what official Bourguibist newspapers proclaimed, and the lack of internal democracy in its working sessions. The anonymous delegate vowed to continue the struggle to gain control of the central committee and shift its dependency on the Parti Socialiste Destourien; this signaled the movement's embrace of similar clandestine and infiltration tactics.Footnote 35 Echoing this counter-hegemonic ambition, Perspectives published a special issue devoted to the martyred labor leader Farhat Hached, elevating his vision and contribution to the Tunisian struggle against the Bourguiba-centric national narrative dominating the 1960s.Footnote 36 After those first years in Paris, they began to see student-related issues as a way to enter the political fray in Tunisia. However, they still had to produce a well-defined counterproject.

GEAST shifted its position on student affairs around 1965 under the influence of a growing Maoist branch within the movement. Maoism was popular in Parisian Marxist circles following the disillusion with Stalinist communist parties.Footnote 37 Tunisians, like other Arab radicals, were specifically drawn to Maoism because it accounted for the social and economic challenges in Third World countries and drew a path for mobilizing classes with a revolutionary potential when they lacked an industrial base. Maoism also served to anoint youth as a revolutionary force. In 1967, the French intellectual André Malraux interviewed Mao Zedong for the weekly magazine Jeune Afrique. The chairman explained the importance of the revolution being truly tied to the working and rural masses: “The youth are not ‘red’ at birth; they have not known the Revolution,” Mao declared.Footnote 38 He warned that in the context of rapid social change, the majority might succumb to a bourgeois mindset induced by material perks, stating that the true liberation does not end with “swimming trunks . . . bicycles and washing machines” but a profound change of frame of mind, adding that:

Our customs must become as different from traditional customs as yours are from feudal customs. The base on which we have built it all is the real work of the masses, the real struggle of soldiers. Whoever does not understand this places himself outside the Revolution.Footnote 39

The Perspectives journal gave more space to Maoist ideas, both as a socioeconomic development agenda and as a mobilization tactic, and later judged that only “the Chinese Cultural Revolution is a truly revolutionary phenomenon.”Footnote 40 The turn to Maoism gave ideological consistency to GEAST, and it also elevated student matters as a fully fledged political program: revolutionary youth could be more than allies; they represented a guardrail against bourgeois materialism due to their idealism and a symbol of the Tunisia they hoped to build.

Bourguiba's University and His Children's Rebellion (1965–68)

The shift to Maoism coincided with the return to Tunis from France of these leftist founders in 1964–65. As Charfi writes, “henceforth, the movement was led from the [Tunisian] capital.”Footnote 41 On their arrival, they realized the scale of domestic student discontent and took the opportunity to elaborate the student question in person rather than from afar. The journal continued to express demands for UGET's autonomy, while adding a focus on the practical and specific concerns of university students to draw them into the movement. GEAST evolved from a discussion group to a political organization, known simply as Perspectives, and in 1966–68 it experienced its apogee. Charfi touted the movement's successes, owing to the student body: “In three years, Perspectives has become the nucleus of an opposition party which has achieved spectacular progress,” including several committees and underground cells that managed to “settle within student ranks as well as with managers and intellectuals, while enjoying a positive reputation across the country.”Footnote 42 They moved away from corporatist issues and began formulating the terms of their counterproject for Tunisia. This set them on a collision course with Bourguibism.

Tunisia changed at a blistering pace during the 1960s. State-led modernization and Destourian Socialism placed the younger generation at the center of the regime's reforms. Bourguiba believed his mission was to “change mentalities,” to make Tunisians “acquire the spirit of modernity” by “elevating the moral and intellectual abilities of the Tunisian people.”Footnote 43 This discourse of “moral straightening” was urgent, Bourguiba argued, in light of the people's “bad reflexes” and propensity for “anarchy, passions, strife and subservience, aggression and lack of discipline.”Footnote 44 The parameters of Bourguiba's discourse illustrate the bourgeois liberal ideology he acquired as a subject of French colonial assimilation, which guided his postindependence course of action. After independence, Bourguiba gave regular speeches, transmitted on radio or television, in which he sought to “educate” and effect collective morality.Footnote 45 He repeatedly cited the role that youth would play in the country's future development, and for that the pro-regime UGET leadership and secular elites gave him full support.Footnote 46

Education was the crown jewel of the state's social reform agenda. The 1958 education reform guaranteed universal access to primary education and enshrined the principle of bilingual education inspired by the Sadiqi College model, the prestigious bilingual school set up in Tunis in 1875 from which most of the country's elite had graduated.Footnote 47 The education portfolio controlled around a quarter of the state's budget in the mid-1960s.Footnote 48 Educational investments included significant funds for higher education to ensure the national university trained skilled Tunisians for the administration and the economy. The University of Tunis expanded its course offerings, so that a growing number of Tunisians no longer had to travel to France to acquire specialized skills in the sciences, engineering, and law, and it began hiring more Tunisians to replace French and European professors. The number of university students grew from 5,158 in 1965 to 6,830 in 1967 (out of 885,121 students of all ages across the country). The teaching staff comprised 127 Tunisians, 121 French professors, and 5 of other nationalities, and the campus saw new buildings and housing units added every year to accommodate this spectacular increase.Footnote 49

Bourguiba and other Destourian leaders prided themselves on these achievements. They saw them through the lens of the colonial experience, when studying opportunities were scarce for native Tunisians. According to their narrative, Tunisians from any geographical or social origin could now study with a stipend, with equal access for women, and male students were exempt from military service. The Tunisian state's blueprint for national development was contained in the Perspectives Tunisiennes 62–71 plan (not to be confused with the Perspectives movement; their similar names were a matter of coincidence rather than any co-optation of ideas). The plan asserted that “training future managers was one of the essential factors of progress.”Footnote 50 Yet, Bourguiba's education reforms were not met with adulation and gratefulness, but by growing student rebellion in the 1960s. As Amy Kallander argues, youth discontent in the 1960s stemmed from a clash of generations. It was expressed by the radical counterculture from the mid- to late sixties onward: men with long hair, women wearing miniskirts, rock and roll music, and the consumption of narcotics, all a rebellion against the older generation's moral discourse.Footnote 51 This was a common refrain across the global South; Jeune Afrique reported on similar movements of youth discontent in 1967, which began with specific material demands and evolved into wider political struggles.Footnote 52 In fact, intergenerational rebellion and counterculture worked alongside student activism at the Tunisian university, according to the historian Abdeljalil Bouguerra.Footnote 53 The Tunisian case stands out because those university students picked up on Bourguiba's discourse on youth as the country's future and demanded self-management of their student affairs. In this fertile terrain, Perspectives and its Maoist wing recruited heavily among student ranks from 1965 to 1967.

When the founding members of GEAST came back to Tunisia, they embodied the Bourguibist success story. They became engineers, professors, and other white collar professions, with comfortable middle-class lifestyles. At the same time, they maintained their semi-clandestine activities for Perspectives, holding discussion groups and continuing to publish their journal. The movement experienced a growing split between two ideological branches. The Maoist branch included Nourredine Ben Khedher, from among the Paris founders, and Gilbert Naccache, an agronomist working for the state. Maoists split with a moderate branch, represented by Mohamed Charfi, who taught law at the University of Tunis and established a discussion group on Tunisia's pro-imperialist foreign policy and the Vietnam war.Footnote 54 The moderate branch moved away from the GEAST circle by integrating professionals and the intelligentsia, while advocating for a softer socialism and democratic reform. In 1966, Perspectives decided to set up a commission idéologique to define a common platform and address this growing ideological rift. Instead of achieving reconciliation, it was Maoism that prevailed; according to Michael Ayari this was due to the popular image of China's Cultural Revolution.Footnote 55 The success of Maoism became a poisoned chalice that soured relations within the movement's leadership.Footnote 56

The Maoist branch also prevailed because it harnessed the energies of the university students. The Maoist group occupied the vacuum left by the absence of the banned Tunisian Communist Party and the discredited UGET. They recruited and mobilized on university campuses, whereas the other branch of Perspectives focused on discussion groups rather than activism. Thanks to their collaboration with Hafedh Sethom, a geography professor, the Maoists had a “foot in the door” of the university, Naccache recalls, which facilitated student recruitment. In February 1966, the Maoists scored a big success at the humanities faculty when the French agronomist scholar René Dumont delivered three talks as part of a technical visit to Tunisia.Footnote 57 Naccache describes these events as the “starting point for the rapid broadening of Perspectives activities.”Footnote 58 Dumont's talks sparked energetic student reactions, as the journal Perspectives related:

Most of the youth were attending such debates for the first time and these conferences made them realize that they could do more than sit through speeches from conference speakers. They too could discuss and challenge the views of supposed “masters.” In fact, they did not prevent us [from challenging them].Footnote 59

Similarly, the philosopher Michel Foucault held a teaching post at the University of Tunis from 1966 to 1968 as part of a technical cooperation arrangement with France. Soon after his arrival, Foucault became a focal point for Perspectives at the university, especially during his lectures and extracurricular activities. During the high point of repression against the Perspectivistes, he hid some of them in his villa at Sidi Bou Said and testified on their behalf during their trials (for which he is remembered fondly by former activists).Footnote 60

The Perspectives counterproject began to take shape in this context. The Maoists theorized the Tunisian student as a harbinger of a new, emancipated Tunisian subject who could have a say in state affairs. Perspectives began echoing the concerns of students regularly in its pages, often departing from concerns about their precariousness, especially how financial support could be withdrawn for disciplinary matters, from poor grades to participating in protests. Instead, writers proposed the principle of self-management at the university in the form of tripartite commissions (comprising students, administration, and professors).Footnote 61 Students would weigh in on scholarships, housing, dining halls, discipline, and examinations, and no longer suffer arbitrary decisions.Footnote 62 Perspectives articles argued that these responsibilities would prepare them for their role as future national leaders, as Bourguiba himself had claimed.Footnote 63 The journal shed light on growing student anxieties over future employment prospects. No longer did higher education guarantee social advancement, as it did for Bourguiba's generation; instead, Bourguiba now told the successors to wait their turn, since the administrative positions had filled up a decade after independence. Following the democratization of higher education, provincials and working classes felt they had “little hope for individual social promotion in the structure where their predecessors snuck in.”Footnote 64 The discrepancy between Bourguiba's promises and the declining opportunities and a favorable economic future sparked anger. Student discontent stemmed not from youthful angst but a desire for responsibility and self-management and violation of the intergenerational social contract, at the local level but with the national horizon in mind. The Perspectives movement pitched its core values in light of the continued absence of an autonomous student union that moved from the empowerment of students to the emancipation of all Tunisian people. The values cited included the following:

• fighting for the genuine autonomy of the student movement;

• supporting the working masses in their struggle for a better life;

• defending the material and moral interests of all students;

• cooperating with national organizations on an equal footing and respecting each organization's political identity; and

• working to set up a larger democracy across the country and include the masses to establish a truly socialist society.Footnote 65

This article, published in November 1966, reads as a genuine political program building on the specific conditions of student life to move toward a crucial intervention for all Tunisians. When read in its historical context, it represents the consecration of the Maoist wing within Perspectives, in imagination and strategy, by adopting the student question as its revolutionary catalyst.Footnote 66 For Naccache, these students “were the only ones to galvanize the group,” and they carried out their tasks fearlessly, including distribution of tracts despite police surveillance.Footnote 67 Progressively, non-Maoist leaders such as Charfi were sidelined from leadership to make room for Naccache and university students such as Ibrahim Rizkallah and Ahmed Othmani. These two carried out their studies in Tunis rather than France, compared to their predecessors, and joined the leadership committee in 1967. Perspectives felt ready to confront the authorities.

Student trouble rocked the university's humanities faculty on several occasions in 1966. The most notable instance came on 14 December, when two students fought with a bus driver after refusing to pay for their tickets and were arrested by the police. This confrontation tapped into feelings of anger and a rejection of authority. As news of the pair's arrest spread within student ranks, their comrades protested in front of the police station, demanding their release. The police made fifty additional arrests. The two “troublemakers” were forcibly drafted into the army, an act that became the regime's modus operandi for students it sought to punish.Footnote 68 The “bus fare” troubles, as they became known, attracted foreign attention, and international observers drew a link between student unrest and the Perspectives movement.Footnote 69 This incident revealed a general malaise among university students rooted in poverty and insecurity about the future, which countered the regime's rosy narrative of student bliss after independence. Jeune Afrique later noted the relationship between rapid university expansion, the integration of 7,000 new students, and the type of logistical challenges found across the global South, pointing to similar protests in Dakar.Footnote 70 Jeune Afrique devoted its coverage of student grievances to the structural limitations of the government's education reform; these grievances were exacerbated by the absence of a functioning autonomous student union to voice these issues and de-escalate the situation.

Bourguiba responded dismissively to these repeated flare-ups on campus, which benefited the Perspectives movement. At first, the Tunisian president refused to engage with the unresolved student issues and the unaddressed demands of previous years, including UGET's autonomy and better living conditions for students. Instead, Bourguiba showed disdain for “a few troublemakers” seeking to undermine public order and the state's authority.Footnote 71 Shortly after, in a speech on 8 April 1966, Bourguiba called on the “good” students:

You must be devoted and take part in the edification of a new Tunisia by combining expertise with militant mobilization . . . it is painful to see these youths, that do not lack competency nor dynamism, waste their time speculating over class struggle, bourgeoisie, or imperialism.Footnote 72

His response reinforced the image of state paternalism, disregard for student grievances, and a denial of their political agency. Bourguiba saw students as bricks in the national edifice, rather than mature individuals with a say in the country's future direction.

By early 1967, Perspectives had consolidated its place as the mouthpiece of the student body. Drawing on Maoist insights, its members saw in the Tunisian student body a great revolutionary potential. Students flocked toward the movement in the absence of other avenues for expression of their causes, such as an autonomous student union. They were the symptoms of Tunisian society's intergenerational crises and misunderstandings, which had similarly produced the French May 1968 riots and Dakar's student riots.Footnote 73 Student discontent snowballed because Perspectives had successfully produced and disseminated a counterproject that spoke to student issues and theorized their rebellion. The bus fare flare-up was underpinned by a political alternative and imagination rather than just anger. By 1967, the student body was on the cusp of a significant transformation of its fortunes.

Perspectives Without the Students: Wandering the Desert After 1968

News of the Israeli defeat of the Arabs in June 1967 drew the Tunisian leftist movement toward a confrontation with the authorities, which caused the collapse of its political project for student emancipation. Tunisian leftism was located at the intersection of several global dynamics, first as part of “global 1968,” as Burleigh Hendrickson has described the postcolonial communication networks of France's May 1968, albeit with some caveats.Footnote 74 Second, Perspectives also was shaped by the Arab 1968, that was, as Yoav di-Capua notes, “entangled in the response to the trauma of June ’67,” adding that Arab Leftists and students turned their revolutionary gaze inward against their discredited leaders after the defeat.Footnote 75 Perspectives was similar enough to the broader-based movements of the new Arab Left in that it embraced the bottom-up politics of everyday life in favor of social and cultural change and shared an anti-imperialist solidarity, from the Palestinian cause to Vietnam.Footnote 76 It differed in that 1967 did not catalyze the movement by promoting its internal growth. Instead, it led to the fracture of its bond with the university students.

In the first instance, the Tunis protests of 1967 brought Perspectives and its student members face-to-face with the Bourguibist state's repressive machine, culminating in the Tunis trials a year later. As news of the Arab defeat reached Tunis, students and left-leaning protesters marched on the downtown area; they turned violent when they attacked Jewish neighborhoods and Western embassies, prompting the police to intervene and launch the first major crackdown against the movement in the ensuing days.Footnote 77 The state set up a special court in September to try 134 students and professors it accused of being behind the wave of riots.Footnote 78 The courts handed out heavy prison sentences, ranging from six months to fourteen years, which appeared to put an end to leftist and student protests on the university campus.Footnote 79

Second, alongside these repressive tactics, the Bourguibist state sought to win back the student body with promises of reform. As a fine tactician, Bourguiba sought to regain their hearts and minds with a combination of sticks and carrots. Bourguiba succeeded in driving a wedge into the student body by denouncing the “subversive” elements stating that “Nous nous intéressons aux étudiants et à leurs instructions mais s'ils devenaient communistes ou maoïstes il faudrait les combattre” (We are keen on students and their education but when they become Communists or Maoists, we have to fight them).Footnote 80 He also ridiculed their revolutionary rhetoric:

Ces révolutionnaires en peau de lapin . . . fraîchement débarqués du quartier Latin, ces zélateurs de l'anarchie . . . rappelant nos anciens adversaires par leur comportement buté, leur fanatisme, leur attachement aux formules toutes faites, aux chimères (These revolutionaries in rabbit's fur . . . freshly disembarked from the Latin Quarter, these zealots of anarchy . . . remind us of our old opponents with their rough conduct, their fanaticism, their attachment to ready-made slogans and their impossible dreams).Footnote 81

In the following years, Bourguiba reminded the students of the government's achievements. He opened the door to the “good ones” or the “hard workers” (les étudiants sérieux, meaning the serious or responsible students), guiding the lost spirits back, declaring: “Nous nous désespérons de personne. Nous croyons en la perfectibilité de l'homme. Il nous incombe de guider les égarés et persuader les méfiants quelles que soient les raisons de leurs méfiances” (We will not lose hope in anyone. We believe in the perfectibility of man. It is upon us to guide the lost ones and convince the suspicious others regardless of the reason behind their fears).Footnote 82 The others, the troublemakers and their leaders, were but a small group who had to be disciplined.Footnote 83 Several top regime members relayed similar messages in public speeches and in the press, demonstrating that this was an orchestrated campaign.

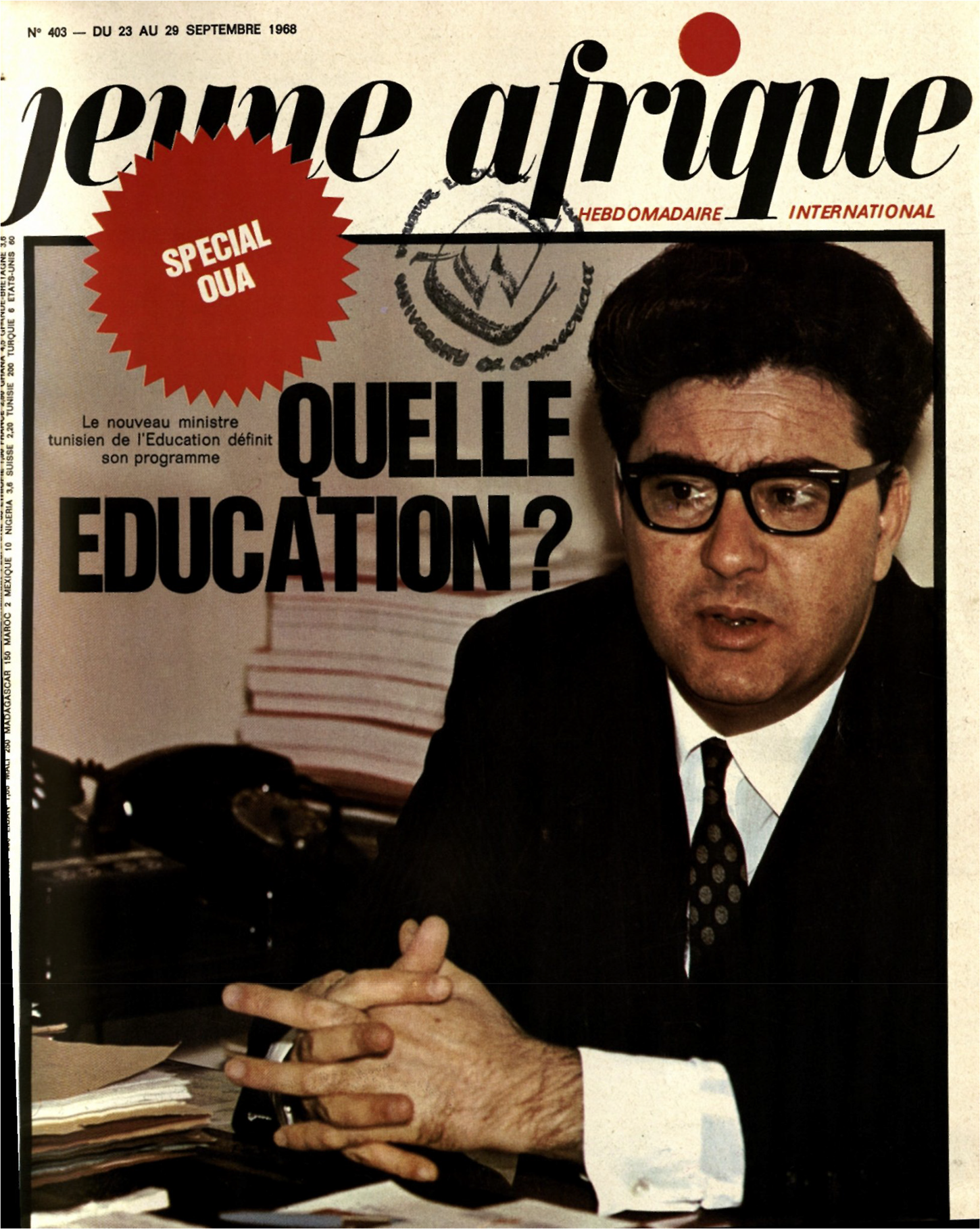

Bourguiba sensed the risk posed by these protests, and so he ordered substantive reforms to appease student discontent. He removed the education minister, the novelist Mahmoud Messaadi, whom he accused of maintaining harsh standards at the expense of the need to provide graduates to the workforce. He gave this portfolio to the powerful younger minister Ahmed Ben Salah, already in charge of national planning and the economy, who was seen as more capable of dealing with structural reform in the education sector and “harmoniz[ing] higher education with the needs of the planned economy.”Footnote 84 Ben Salah, a former trade union leader, had greater credibility among the students and promised change.Footnote 85 In the following months, he introduced much-needed reforms to the university; he was the subject of a Jeune Afrique cover in September 1968, seated at his desk in a committed and intent posture, with a headline asking “Quelle Education?” (What Education?; Fig. 1). He outlined plans to decentralize decision-making by setting up committees with faculty and union stakeholders, to reorient academic programs toward professional needs, and to change admission schedules to facilitate student integration rather than maintaining the high academic standards pursued by his predecessor that caused so many to fail and so much student discontent, as scholarships were dependent on academic success.Footnote 86 He introduced a student work program (stages étudiants) so that students could spend time interning in state factories and on farms with the promise of future employment.Footnote 87 Ben Salah took his message directly to the students, and the meetings often saw passions flaring, with Perspectives sympathizers in the room.Footnote 88 All these measures swayed a considerable section of the student body, especially the moderates who leaned toward Perspectives in the absence of constructive overtures from the regime before 1968 (even if Ben Salah's promises were far less ambitious than the demands made in the journal Perspectives). Before these measures could deliver results, Ben Salah was removed from power. In 1969, a wave of riots in the countryside against his rural collectivization policies pushed Bourguiba to order his demotion and arrest.Footnote 89 The rapid rise of this young politician also caused concerns among the old Destourian guard, who engineered his downfall. In 1970, Bourguiba named Hedi Nouira as prime minister, a regime stalwart who shifted the country back onto a liberal economic route that yielded rapid growth.Footnote 90 Nouira was a sexagenarian and Bourguiba's contemporary, thus unlikely to depart from the regime's paternalist views toward students or to continue Ben Salah's ambitious reforms. By then, the leftist-student connection had been disabled.

Figure 1. Ahmed Ben Salah on the cover of Jeune Afrique 403 (23–29 September 1968).

This was arguably the most difficult period in the Perspectives movement's history, because of the challenge the regime's promises for reform posed for the organic link it had fostered with the student body. Founding leaders Naccache and Ben Khedher languished in jail, whereas others such as Charfi demanded a presidential pardon in exchange for abandoning politics.Footnote 91 Some left the country altogether. On university campuses, Destourian student militias hounded surviving cells.Footnote 92 The leaders who took up the mantle were those, such as Ahmed Othmani, who were elevated by the Maoist group before the 1968 trials. Othmani was arrested in 1968 but feigned repentance when he asked for a presidential pardon. He was released, only to continue his activism for the Perspectives movement in a clandestine manner with his spouse, Simone Lellouche, and a surviving nucleus of activists.Footnote 93 Eventually, in April 1971, he was again arrested after the police raided his apartment and found copies of the movement's journal, which had been banned. In January 1972, the authorities expelled his wife, a Tunisian Jew who held a French passport, on charges of public disturbance (she led student solidarity protests for her husband in front of the main tribunal).Footnote 94 Her expulsion sparked more student protests, and she continued coordinating the movement from France.Footnote 95 During this period, the authorities made systematic use of torture as a means of extracting information during interrogation to locate and dismantle remaining cells of the movement, as detailed by the landmark testimony published by Othmani after his 1979 release.Footnote 96 Perspectives survived by shifting its tactics from those of a well-defined structure with working groups and committees to ad hoc modes of decision-making. The movement's cells in France became autonomous, and Perspectives underwent a shift in priorities and outlook.

For two years after the 1968 trials, Perspectives struggled to regain the ideological upper hand on university campuses. The journal acted primarily as a tool to denounce state repression and to mobilize support for the jailed leaders instead of selling its counterproject. In April 1969, it devoted an article to the hunger strike at the Borj Erroumi prison. The thirty-four imprisoned leftists demanded to be recognized as political prisoners, along with better conditions including the right to receive books and newspapers and to receive food packages from family members, sanitary living conditions, and the ability to correspond with those outside.Footnote 97 Although the hunger strike achieved little, its aim was to show how the struggle against repression continued behind bars. The group also diagnosed the causes of its current “crisis” as the priority the movement gave to “agitation” on campuses rather than what they called “organization” and “theorization,” and the internal division of the movement and growing animosity between “opportunists” and “adventurers,” as each side called the other.Footnote 98 A year later, Perspectives started to return to the student question as a key component of the “theoretical work” ahead. They called for an in-depth study of the university's demographics and the history of the student movement, alongside a sociological study of Tunisian society to assess its ripeness for revolution.Footnote 99 A year later, they issued a direct call to students, after the state authorized a pro-Palestine student protest in Tunis. Perspectives warned the students that these were attempts to co-opt the student movement, while continuing to “deny their adulthood”; it was stated that “this regime has a golden rule: those who do not share its reactionary policy, all those opposing Tunisia's participation in strengthening American imperialism, all those are not adults, it will put them under surveillance (liberté surveillée).”Footnote 100 Perspectives called for “unity, to close ranks, since the more this regime is weakened, the more it becomes aware of its upcoming demise and the masses unifying, the more it grows in ferocity, and the more it will try to divide [us].”Footnote 101 This combative rhetoric masked the fight for survival undertaken by Perspectives, rather than defending and developing the student question. In fact, in December 1970, the group gambled with a redesigned issue of Perspectives, now more newspaper than periodical, adorned with the hammer and sickle for the first time (Fig. 2). The revamped publication linked yet “another struggle at the University in Tunis” to the climate of social agitation across the country, including among the workers and miners. They proclaimed “a Tunisian revolutionary movement that knows today an unprecedented scope,” more of an aspirational statement than a factual one.Footnote 102 As Perspectives leaned fully into social agitation, the periodical adventure ended: this was its last issue.

Figure 2. The revamped Perspectives with the hammer and sickle logo (December 1970).

The scale of the regime's 1968 repression of Perspectives delivered a near fatal blow to Tunisia's leftist movement. Protests endured, but they were contained within campus walls. Whereas the remaining leaders languished in jail, others relocated to France, or were harassed in Tunis. Perspectives lost the potency and relevance it had enjoyed in 1965–67. Nonetheless, facing its ideological demise, the unexpected afterlives of the student question allowed the movement to persevere by reinventing itself, thanks to a generation of successors.

Perspectives in the Marketplace of Radical Ideas (1970–72)

From 1970 onward, Tunisian leftism went through a splintering and reconfiguration as the university became a marketplace of radical ideas. Weeding out student radicalism entirely was impossible, although the authorities succeeded in disrupting the Perspectives movement. Foreign observers pointed to the “communists” and the “students” as the main opposition to Bourguiba's regime.Footnote 103 The veteran Jeune Afrique journalist Guy Sitbon, who had covered the Algerian FLN (National Liberation Front) from Tunis before, noted the absence of a “firm ideology” among these groups of radical students and failed to identify its various components—not that he could be blamed. He explained that they were committed to disruption and collective action in this fragmented space, vying for student recruitment while evading regime repression.Footnote 104 Perspectives allied itself with the workers’ movement, and other groups on campus included Baʿthist circles and surviving cells of the Tunisian Communist Party.Footnote 105 These groups formed and re-formed themselves at the rate of arrests, graduation, and discovery of new branches of Marxism. The history of Tunisian student radicalism in the 1970s lost the focus of the previous decades due to the multiplication of groups and their different ideological shades. Instead, I read this period as the afterlife of the student question. During this new stage of the political project, ideological work took a back seat to practical actions; namely, Perspectives began infiltrating UGET, something they had not achieved during their previous bid in the 1960s.

Perspectives opened a breach on campus, but they were not the only opposition group in a fragmented space of radical mobilization that contained other groups, all vying for student recruitment.Footnote 106 In France, a Tunisian worker and a surviving perspectiviste, Hachemi Ben Frej, established a journal called al-Amil Tounsi (the Tunisian Worker) offering a synthesis of leftism and pan-Arabism. The journal reached five thousand monthly copies, five hundred of which were smuggled back to Tunis, according to Michael Ayari.Footnote 107 Although students were a force, they “lacked a firm ideology” according to Guy Sitbon, but he noted the infiltration and takeover of UGET, something they had not been able to do previously.Footnote 108 The Perspectives movement may have become less visible outside the university walls after 1966 and 1967, but it was undergoing a spectacular transformation on the ground and within student ranks. The key to the reconfiguration of student political strategies lay in demographic changes at the Tunisian university. The student population grew from five thousand in 1964 to ten thousand in 1970. The increased numbers came from the postindependence generation, including a growing share of provincial Tunisians.Footnote 109 This demographic shift was mirrored within Perspectives. Its new student members came from different social origins than the founders, the Paris-trained Maoist leaders who languished in jail or in exile. This created an opening for the new generation to take Perspectives in another direction. These life experiences and resulting ideological choices are clearly outlined in the memoirs of Cherif Ferjani and Fethi Ben Haj Yahia, who entered the University of Tunis in the early seventies.

Cherif Ferjani came from a high school in Kairaouan in the country's interior rather than the Sadiqi College in Tunis. He attributed his teenage rebellion to the influence of his teachers, recounting being expelled from high school and even visiting the police office a few times. Eventually, in 1969, he arrived at the university with a “spirit of revolt” underpinned by a critical outlook and a desire to join Marxist discussion circles where he stood out among his “anarchist, situationists, Guevarist and national Marxist friends”; he even requested a scholarship from the Soviet Union's embassy in Tunis.Footnote 110 Similarly, Fethi Ben Haj Yahia writes that his motivation came from a desire for political involvement rather than ideological convictions. He was recruited while still in high school in the thick of the action around Perspectives protests:

I was in the final year of high school at the Khaznadar lycée . . . I was very quick to integrate with my surroundings thanks to football and this street culture that I acquired during childhood in the working class neighborhoods near Montfleury. . . . We were a bunch of teenagers in front of this high school waiting for the last ring of the bell to join class with reluctance, when a handsome young man and a stunning young woman approached us. They asked if we were aware of the political trial against Ahmed Ben Othman, Simone Lellouche and many others that we knew as well as an old Zaytuni would know Darwin's theories. They told us that the government was plotting for a selective higher education policy and that after securing our baccalauréat, something they presented as a given, we would become nothing more than an unemployed lot and undesirable citizens (muwāṭinīn manbūdhīn wa ‘āṭilīn), since that plan was obviously only going to benefit the kids of the bourgeoisie (awlād al-burjwāziyya). The young woman spoke, and she was so pretty and elegant that, in our eyes, she was above any social class. And since we hated the kids of the bourgeoisie with everything the word meant to us in our everyday vocabulary, such as awlād nānā [pejorative Tunisian slang for effeminate or gay men] and other terms there is no point in remembering, I quickly expressed my desire to attend their secret meeting planned for the next day. The rendezvous was fixed downtown, in Lafayette.Footnote 111

Upon their arrival, these rebellious youth were soon recruited into the leftist movement. The two young men arrived at the humanities faculty in 1969–70 smitten by the radical atmosphere. Their road toward leftist militancy did not start with texts and discussion groups; instead, they cited the “legend of the Che” or the Vietnam war and the Palestinian struggle as inspiration.Footnote 112 The students began to draw on the Arab revolutionary experience, which they often sought out in person, rather than Parisian Maoism. Ferjani recounts how he discovered an offshoot cell of Perspectives, al-Charara (the Spark), one summer in Lyon through their literature.Footnote 113 Then in November 1971 Ferjani and his friends attempted to join the Dhofar rebellion from France in between academic years, only to reach Baghdad and realize they lacked the adequate visas to cross over to Oman. Ferjani remembered fondly the friends they made along the way.Footnote 114 This anecdote attests to the romanticism of the struggle, and a core feature of second-generation Tunisian leftist repertoires: good intentions and poor preparation.

Ultimately, these experiences changed the movement's ideological repertoire. The progression from membership to leadership of Perspectives was often a fast-tracked affair and marked by the rhythm of arrests. This meant that posts opened up faster than students could acquire political and ideological training. In 1972, Ben Haj Yahia joined the humanities faculty, enjoyed the new freedom and coed atmosphere, found his way to the radical student circles inside UGET, and came in contact with the Perspectivistes when the movement was evolving into the new organization calling itself al-Amil Tounsi “under pressure from the new generation.”Footnote 115 Back then, they were the “stars” on campus, activists with a “heroic aura” who could talk expertly about Marxism for hours. Due to police arrests, Yahia was soon promoted and became one of them.Footnote 116 Looking back, he questions his preparedness, since his reference point was “Che Guevara rather than Marx.” Indeed, this whole generation of activists “moved from the intellectual circles to the militant cell before having finished reading the Marxist basics.”Footnote 117 Rather, Yahia had excellent organizational skills and led a clandestine operations to distribute leaflets at night. These documents denounced Bourguiba's “dictatorship” by crafting a simplified socialist-inspired message for the masses using slogans that appealed to local concerns, such as “Strawberries being grown in greenhouses for the outside market without the people being able to see their color or form” (thamrat al-farāwla al-latī nazraʿuhā fī al-buyūt al-mukayyafa liyastaʾthir bihā al-ʾajnabī wa lā yaʿrifu minhā al-shaʿb sawā al-laūn wa-l-shakl).Footnote 118 This was a far cry from the thirty-page studies of agriculture policies of 1964, but it tapped into the same spirit of the students’ right to define Tunisia's postindependence future.

These trajectories speak to the ideological consequences the democratization of higher education had on the Perspectives movement. There was a shared conviction in the students’ right of political agency and responsibility to challenge the government's ideological line. However, leftist students stopped being the country's elite-in-waiting; instead, they expressed employment anxieties and called for direct action and reawakening of the student struggle from its slumber. This reveals another feature of student politics in the early 1970s: after the 1968 defeat, the leadership vacuum allowed for the emergence of a new generation of leaders from student ranks. I see them as by-products of the student question coming alive to uphold the struggle of a student vanguard that hoped to reignite the whole country. The opportunity presented itself soon enough.

Chasing the Revolution: The Student Question Outside the University (1972–75)

Spurred by the new generation of Tunisian students, Perspectives scaled up its projects and set out to infiltrate and take control of UGET. The opportunity came in August 1971 in the small seaside village of Korba, where the union held its eighteenth congress. This time, in contrast to the1960s, the leftists deployed a more patient tactic, meant to finally secure its autonomy from the ruling party. The other difference lay in its ideological pragmatism. The movement's members had fewer qualms about cross-ideological arrangements than their Maoist predecessors.Footnote 119 This event marked a shift from survival and agitation to a tactic of institutional takeover, thanks to the emergence of the new generation of leaders from within the student ranks.

Due to the need for secrecy and the safeguards Perspectives put in place to protect it from regime tactics, there is insufficient information to re-create the process by which this new strategy was decided, except for the events of the day.Footnote 120 The historian Taoufik Monastiri left a compelling account of the event as it played out:

For the first time in a decade, a coalition was constituted between left-leaning Destourian students, communists, Arab nationalists and leftists. This coalition obtained the majority of voices in the congress [and] it took this opportunity to revise the Union's charter to reflect its autonomy from the Parti Socialiste Destourien. Then, the congress experienced a confusing episode and the president stepped down, followed by the vice president; students of this “coalition” left the meeting, and the minority that remained took advantage of the situation to organize new elections and continue their work. The coalition of opposing congress members later judged . . . the decisions taken in their absence to be null and void and challenged their representativeness.Footnote 121

The Korba incident indicates how the student question as a demand for autonomy lived on within the psyche of radical students, despite being hounded on university campuses and having their leaders arrested. This coalition satisfied the long-standing demand to be represented by an autonomous union and manage their own affairs. The coalition failed in its bid to gain control of UGET's governing committee, despite securing a legal majority. However, Korba was not a total failure, as the historian Mohammed Dhifallah explains; it was a turning point for the student movement thanks to the cross-ideological alliance between Perspectives, communists, and Baʿthists.Footnote 122 It made national news and shed light on student demands for autonomy from the regime.Footnote 123 In the ensuing decades, opposition politics within UGET downplayed the importance of ideological purity in favor of forming strategic fronts, a legacy of Korba.Footnote 124

This failure to gain control over UGET through elections drove these radical students to other, more direct means of action outside the university. On their return to Tunis, Perspectives students and their pan-Arab allies coordinated a series of protests, culminating on 5 February 1972, known as Black Saturday. Five thousand students made up the protest, joined by high schoolers in the capital and in the provinces. The authorities made around a thousand arrests.Footnote 125 The protestors attacked symbols of state authority, including Bourguiba himself, when crowds chanted “al-shaʿb huwwa al-mujahid al-akbar!” (the people are the supreme combatant), a quip against Bourguiba, known to Tunisians as the “supreme combatant” for securing independence from France. Such a personal attack against Bourguiba in a public space crossed a red line for the regime.

Shortly after, the authorities launched a crackdown, now targeted at the student body as a whole rather than a few organizations, as in 1968. The “trials of Marxists-Leninists” (procès des militants marxistes-léninistes) took place on a rolling basis every few months. They betrayed the realization that the “opponent” was no longer a single organization and instead, for the regime, had become diffused within the student body.Footnote 126 The Black Saturday protests raised the alarm about the danger of a cross-ideological group of radicalized students and prompted stronger reactions. Humanities and law faculties were closed until the end of the year.Footnote 127 Unlike 1968, Bourguiba did not make a distinction between “troublemakers” and “serious students.” In his official speeches and in the press, he portrayed “Marxism-Leninism” as a disease that had “infected” the entire student body, that had spread through a “foreign hand,” and that needed to be culled. There was no tangible proof of realistic plots, outside of anecdotal references to some student contacts with the Soviet and Chinese embassies, who would sometimes provide typewriters and study trips. The special court for “state security” accused the students of endangering internal security, offending the head of state, and illegally distributing tracts.Footnote 128 Every few months until mid-1975, the court tried more students who stood accused of being part of the loosely defined “Marxist-Leninist opposition” (which contained Perspectives, other leftists, and Baʿthists), until they were confident of having dismantled their cells and networks. By targeting university students so broadly, the state broke its symbolic pact with the educated elites two decades after Tunisia's independence.

Following this increase in regime repression, several Perspectives cells adopted a more radical tone and moved their activities outside the university. They embraced the prospect of an armed struggle against the authorities. Ben Haj Yahia was part of a radicalized cell operating in secret and constantly losing its members to police arrests. In early 1973, he fled the country after being alerted that the police were after him.Footnote 129 He traveled east with others to train in the arts of guerilla tactics and armed struggle alongside Lebanese and Palestinian groups in the Bekaa valley.Footnote 130 He returned to Tunisia after crossing the border illegally from Annaba, in eastern Algeria, and joined a small underground cell with a cache of improvised weapons. In Ben Haj Yahia's narrative, this sounds like a pipe dream, as he and his comrades attempted to secure clandestine passage across the border by paying for strangers’ beers at an Algerian bar, or by visiting friends and family without suspecting they were being followed. Due to youthful exuberance and lack of caution, Yahia was apprehended in the spring of 1975 and put on trial in July along with 101 others in a “courtroom full and ready to burst, with families, lawyers, security officers and some friends that managed to evade police control at the door.”Footnote 131 A foreign correspondent attending one such trial of “Marxist-Leninist” students reported that the judge called the accused “insolent” and “ungrateful.” In turn, these students “left the tribunal with their fists held high” and chanting the Internationale.Footnote 132 Soon after, Ben Haj Yahia was sent to the Borj Erroumi prison near Bizerte, along with Cherif Ferjani and older Perspectivistes.

Borj Erroumi was a strange scene in the mid-1970s: it held two generations of Tunisian leftists from the same organization, sharing three adjacent prison cells (A, B, and C) who often had never met before. The two groups had little in common aside from their opposition to Bourguibism. Naccache, from the first generation, wrote about his shock upon receiving a smuggled copy of the journal Perspectives in prison and seeing the hammer and sickle on the front page along with its pro-Arabist content, a far cry from the organization he and the movement's founders had sought to establish: anti-Stalinist, secular, and Tunisia-centric.Footnote 133 Ferjani and Ben Haj Yahia, like other young leftists, called him “papi,” a nickname meant to convey some affection but also to mark him as a vestige of the past. After all, these were leftists who cut their teeth by rejecting Bourguiba's paternalism and were allergic to most forms of disdain from older generations, especially the francophone urbanites. From 1974 to 1979, these prisoners coexisted uneasily within prison walls. Outside, on university campuses, Tunisian Islamists filled the void, often using methods and tactics of those they were encouraged by the authorities to target and harass, to now attack the Destourian state.Footnote 134 They too, to some extent, were products of the student question, despite their widely different ideological choices.

By the early 1980s, the government had released most of these leftist prisoners and turned its attention to the growing Islamic contestation. At Borj Erroumi, their memoirs inform us, the Perspectivistes made some ineffectual attempts to maintain their political commitment by holding some ideological debates. In reality, they were isolated from the outside, managing occasionally to smuggle in newspapers or build makeshift transistors, but they were most often being plagued by prison mistreatment, personality clashes, and political scheming that would pause only during their daily football games and family visits.Footnote 135 After their release from prison in 1979–80, many joined newly established organizations for the defense of human rights in Tunisia instead of returning to leftist activism. The authorities tolerated the Tunisian League of Human Rights and Amnesty International, and they offered a connecting thread for yesterday's student leftists in their transformative ideals. Even after they reintegrated into Tunisian society, the Perspectives episode was largely ignored by the wider public. In 1987, Bourguiba was removed from office by his prime minister, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who empowered the Tunisian authoritarian state further. For several decades, the student question was gleaned only in memoirs and memories and absent from the main Tunisian national narrative.

Conclusion

During the post-2011 Tunisian transition, transitional justice processes such as the Instance Vérité et Dignité, Tunisia's truth commission, gave the country a platform for national reconciliation. The testimonies of former leftists figured prominently, including that of Gilbert Naccache, who spoke about his journey from Perspectives to his many arrests and years in prison.Footnote 136 Bringing the Tunisian leftist movement to the heart of Tunisian national historiography represents the next step in consolidating these democratic gains. However, broadening Tunisian historiography for its own sake can be a pitfall. Rather than merely commemorating these groups, historians can do them justice by reconstituting these groups’ political imaginations. We find traces of their histories in periodicals and the militants’ memoirs, and, within those, the traces of a political project waiting to be reassembled and assessed. Chief among those was the student question, a political project for emancipation formulated by the Perspectives Tunisiennes that inspired successive generations of its members. At its heart lay a conception of an emancipated university student, a responsible subject who could eventually succeed the generation of nationalist leaders who had secured independence and who still held on to state affairs. Perspectives produced a vision of Tunisian citizenship and political agency granted to everyone rather than to a minority of educated, loyal, and Destourian allies. As products of Bourguiba's modern university, they rejected the regime's promise of future reward, took aim at Bourguiba's paternalist and bourgeois views on social progress, and saw themselves as the vanguard that would usher in a new sociopolitical model through revolution. Their legacy to Tunisia's postindependence history was seminal. As Mohamed-Salah Omri writes, Perspectives was a large ideological tent that “gathered all sorts of people from genuine liberals to extreme left activists . . . who rebelled against the repression which became routine in Tunisia,” while demonstrating their ability to imagine another Tunisia beyond Bourguibism.Footnote 137 Even if Perspectives slipped into oblivion from the 1980s onward, this legacy served future opposition groups well.

This article also has underlined the need to rewrite histories of the New Arab Left as part of the main national narrative rather than as groups on the margin of society, culture, and politics. Tunisian leftists enjoyed and cultivated a central bond with university students, who in Tunisia and other progressive Arab countries have been the pillars of national development programs. Historians must strike the right balance between narratives that acknowledge the national commitment without falling into the trap of idealized portrayal of their heroic struggles. Theirs was a history of some successes and many failures. For those who spent years in prison and suffered torture and lasting traumas following their convictions, and for their families, writing their history offers the possibility for closure. As founding leader Nourredine Ben Khedher explained shortly before his death in 2005, “Nous étions les enfants illégitimes de Bourguiba” (we were the illegitimate children of Bourguiba).Footnote 138 At the 2008 Temimi Foundation round tables, former Perspectivistes disagreed: “Nous étions ses enfants légitimes!” (we were his legitimate children!). And they went on to debate and bicker just as they had many decades ago.

Acknowledgments

This article has greatly benefited from conversations with Mohamed Salah Omri, Kmar Bendana, Amy Aisen Kallander, Hannah Elsisi, and Dylan Baum. This journal's editor and anonymous reviewers offered generous and generative comments, as did feedback from attendees at the conference “Left-Wing Trends in the Arab World (1948–1979): Bringing the Transnational Back In,” held in Beirut in December 2016. Finally, I extend warm thanks to the former Perspectivistes who have shared their memories with me over the years.