Mental illness has been conceptualised as a stigmatised attribute and many studies have indicated that stigma relating to mental illnesses and stigmatising attitudes to people with mental illness are widespread. Reference Crisp, Gelder, Rix, Meltzer and Rowlands1-Reference Alonso, Buron, Bruffaerts, He, Posada-Villa and Lepine4 There are several distinct forms of stigma that are conceptualised in the context of mental illness. Public stigma of mental illness is defined by the extent to which the general population collectively holds negative beliefs and attitudes about mental illness and the degree to which they discriminate against those with mental illness. Personal stigma can be thought of as each individual’s prejudices and stigmatising attitudes towards those with mental illness, an aggregate of which leads to public stigma. Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves5

Perceived public stigma relates to the extent to which an individual perceives the public to hold stigmatising attitudes towards those with mental illnesses. Reference Corrigan6 Finally, ‘felt-stigma’ or ‘internalised stigma’ arises when an individual who is affected by a mental illness, begins to relate these negative social conceptions to themselves. Reference Watson, Corrigan, Larson and Sells7,Reference Mittal, Sullivan, Chekuri, Allee and Corrigan8 Over the past two decades there has been an increasing recognition of stigma in mental illness as a major public health challenge and as a key factor in the poor utilisation of mental health treatment. Large-scale epidemiological research has shown that less than 25% of a college-aged population with mental disorders had received treatment in the past year. Reference Blanco, Okuda, Wright, Hasin, Grant and Liu9 This is particularly pertinent as it has been estimated that approximately 75% of lifetime mental disorders have their onset before the age of 24 Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters10 and the onset of mental disorders at a young age is associated with an adverse impact on educational and social outcomes, Reference Breslau, Lane, Sampson and Kessler11 as well as impaired occupational functioning. Reference Kessler and Frank12 The lack of help-seeking behaviour in those who have engaged in suicidal behaviour has been demonstrated in epidemiological studies Reference Schweitzer, Klayich and McLean13,Reference De Leo, Cerin, Spathonis and Burgis14 and is recognised as a risk factor for completed suicide. The significance of this is highlighted by suicide being among the top three causes of death in the population aged 15-34 years. 15

There have, however, been conflicting findings about the effects of stigma on help-seeking intention and behaviour for mental disorders. Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer16-Reference Blumenthal and Endicott19 This is speculated to be a consequence of the complexity of mental illness stigma as a concept and the inherent differences that exist in measuring it. Public stigma has been conceptualised as a negative stereotype agreement Reference Corrigan20 and this has been further developed and conceptualised as personal stigma. Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves5,Reference Griffiths, Christensen and Jorm21,Reference Calear, Griffiths and Christensen22 The need to consider both personal and perceived public stigma when measuring mental illness stigma, as well as the need to treat them as separate entities has been demonstrated. Reference Griffiths, Christensen and Jorm21 Both personal stigma and perceived public stigma have been shown to be associated with impaired help-seeking behaviour, Reference Gulliver, Griffiths and Christensen23 with personal stigma being more consistently reported to be associated with non-help-seeking intention and behaviour. Reference Schomerus, Auer, Rhode, Luppa, Freyberger and Schmidt17,Reference Golberstein, Eisenberg and Gollust24,Reference Griffiths, Crisp, Jorm and Christensen25

In this study we sought to assess the level of perceived public stigma in a population of university students. As a secondary aim, we sought to measure the level of personal stigma, in order to ascertain the students’ personal attitudes towards mental illness. Personal stigma is a broader concept than ‘felt stigma’ and applies to everyone regardless of an individual’s prior history of mental illness. This is important as university students are in an age group that often experience mental health problems for the first time Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters10 and are often unaware that they have mental health problems that could benefit from treatment. Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26 We hypothesised that both perceived public stigma and personal stigma would be independently associated with lower help-seeking intention under the assumption that an individual is influenced by both others’ and his own attitudes regarding mental health treatment.

Method

This study was conducted at the National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG) primary care student health clinic. The student health clinic is situated on the campus of NUIG and provides primary healthcare to a student population of over 17 000. Within the primary care setting, there is a dedicated psychiatric clinic providing assessment and treatment to students with mental health difficulties. The university counselling service provides psychotherapeutic support on a self-referral basis.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of university students in order to ascertain the levels of perceived public mental health stigma that exist in this population and to look for any association between perceived public stigma and help-seeking intention in this typical young student population. As a secondary aim, we sought to ascertain the levels of personal stigma and to explore whether they were associated with help-seeking intention. An anonymous, self-administered questionnaire was distributed to attendees at the student health clinic over the 2-week study period in March 2012. The study was advertised by a poster in the primary care clinic and all attendees were invited to participate in the study. The clinic attendees were provided with a letter of information and were requested to complete the questionnaire once only; a post box was provided for the finished questionnaires and anonymity was assured. All participation was voluntary.

Perceived public stigma was measured using an adaptation of the Discrimination-Devaluation scale (D-D) (Appendix 1). Reference Link27 This is a well-validated scale that has demonstrated an internal consistency of 0.86 to 0.88 in university Reference DL Vogel and Hackler28 and community samples respectively. Reference Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen and Phelan29 The D-D scale assesses the extent of agreement on each of 12 statements, which indicate that most people will devalue or discriminate against someone with a mental illness or a history of mental health treatment. The extent of agreement was measured on a five-point Likert scale. The scale is balanced so that a high level of perceived devaluation-discrimination is indicated by agreement with six of the items and by disagreement with six others. Reference Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen and Phelan29 The responses were coded 1 (strongly agree), 2, 3 (no opinion), 4, 5 (strongly disagree), and items were appropriately recoded so that higher scores corresponded to a higher perceived stigma. We calculated the mean score across the 12 items for each participant. The original D-D scale refers to ‘mental patients’ but we broadened this concept by changing the wording to refer to people who have received mental health treatment.

To measure personal stigma, we adapted four items from the D-D scale by replacing ‘most people’ with ‘I’ (Appendix 2). This technique has been employed in other studies measuring personal stigma, Reference Griffiths, Christensen, Jorm, Evans and Groves5,Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26 in order to adapt perceived public stigma scales to allow for the measurement of personal stigma. These four items referred to accepting behaviour (‘I would willingly accept a person who has received mental health treatment as a close friend’ and ‘I would be reluctant to date a man/woman who has received mental health treatment’), an accepting attitude (‘I believe that a person who has received mental health treatment is just as trustworthy as the average citizen’) and a negative attitude (‘I would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment’). A similar adapted scale when utilised in another study to measure personal stigma showed a moderately high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.78. Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26

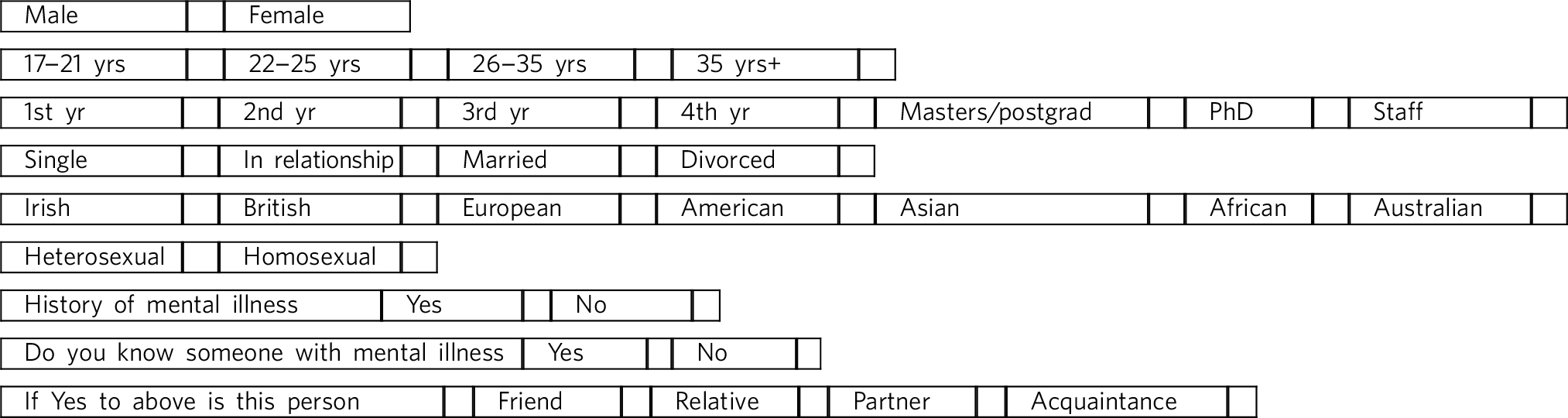

Demographic data including gender, age range, nationality, sexuality, relationship status and year of university study were collected (Appendix 3). Additional data regarding the participants’ history of mental illness, treatment for mental health problems and their personal contact with someone with a history of a mental illness were collected. We measured help-seeking intention by asking the question ‘If mental health problems were affecting your academic performance, who would you talk to?’. This was coded as a binary item (1 if ‘no one’ was selected and 0 otherwise). We also included a measure of perceived help-seeking by asking participants ‘In the past year, did you think you needed help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling sad, blue, anxious or nervous?’ and a measure of prior mental health services use, by asking ‘In the past year have you received treatment for mental health problems?’. The respondents were asked specifically whether they had received any psychotropic medication or counselling for their mental health problem.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 18.0 for Windows. Associations between demographic characteristics and perceived/personal stigma were ascertained. A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to test the validity of the personal stigma scale. We utilised the Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for parametric data where appropriate. Post hoc analyses using the Scheffe post hoc criterion for significance were conducted where ANOVA demonstrated significant differences between the group means. We used logistic regression to estimate independent correlates of binary help-seeking intention. All statistical tests were two-sided and the α level for statistical significance was 0.05.

Results

A sample size of 735 participants was obtained for the study, representing a response rate of 77% (based on a total number of 960 individual attendees at the primary care clinic over the 2-week study period). The majority of participants were female (73.5%, n = 540), with most of the sample aged less than 21 (75%, n = 551). Of the sample 12% (n = 88) reported a personal history of mental illness, with 57% (n = 417) reporting having personal contact with a person with a mental illness. In total 15% (n = 109) reported receiving treatment for a mental health problem in the previous 12 months, with 54% (n = 59) of those students who received help for a mental health problem attending counselling. A perceived need for help for a mental health problem was reported by 48% (n = 356) of the sample reported

Most of the sample reported that they would speak to someone if they were having a mental health or emotional problem, with the majority stating that they would speak with a doctor (31%, n = 225), 22% (n = 163) reporting that they would speak to a family member and 18% identifying a counsellor as someone they would speak to. Students who identified a second person who they would speak with (n = 308) chose a friend in 36% (n = 111) of cases. The social and clinical demographics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient sample (n = 735)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 195 (26.5) |

| Female | 540 (73.5) |

| Age range, years | |

| 17-21 | 551 (75.0) |

| 22-25 | 124 (16.9) |

| 26-35 | 45 (6.1) |

| >35 | 15 (2.0) |

| Year in college | |

| First-year undergraduate | 221 (30.1) |

| Second-year undergraduate | 168 (22.8) |

| Third-year undergraduate | 174 (23.7) |

| Fourth-year or higher undergraduate | 63 (8.6) |

| Undergraduate total | 626 (85.2) |

| Postgraduate | 107 (14.5) |

| Staff member | 2 (0.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 428 (58.2) |

| In relationship | 293 (39.9) |

| Married | 13 (1.8) |

| Divorced | 1 (0.1) |

| Sexuality | |

| Heterosexual | 715 (97.3) |

| Homosexual | 18 (2.4) |

| None stated | 2 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Irish | 636 (86.5) |

| British | 23 (3.1) |

| European | 27 (3.7) |

| North American | 34 (4.6) |

| Asian | 11 (1.5) |

| African | 4 (0.5) |

| History of mental illness | |

| Yes | 88 (12.0) |

| No | 647 (88.0) |

| Treatment for a mental illness in past 12 months | |

| Yes | 109 (14.8) |

| No | 626 (85.2) |

| Treatment received for mental health problem in the past 12 months (n = 109) | |

| Medication | 9 (1.2) |

| Counselling | 59 (8.0) |

| Both | 41 (5.6) |

| Do you know someone with a mental illness? | |

| Yes | 417 (56.7) |

| No | 318 (43.3) |

| Relationship to that person with a mental illness (n = 417) | |

| Friend | 130 (17.7) |

| Relative | 144 (19.6) |

| Partner | 4 (0.5) |

| Acquaintance | 56 (7.6) |

| More than 1 person | 83 (11.3) |

| In the past year did you think that you needed help for an emotional or mental health problem? | |

| Yes | 356 (48.4) |

| No | 379 (51.6) |

| If a mental health problem was affecting your performance, who would you talk to? | |

| Doctor | 225 (30.6) |

| Counsellor | 129 (17.6) |

| Family member | 163 (22.2) |

| Friend | 95 (12.9) |

| Faculty member | 6 (0.8) |

| Religious service | 1 (0.1) |

| No one | 116 (15.8) |

There was a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) in the adapted scale D-D used in this study to measure perceived public stigma, and the adapted scale used to measure personal stigma had a moderately high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). There was a positive correlation between the perceived public and personal stigma variables (r = 0.33, P = 0.001). Item-total correlations showed positive correlations between each item and the others on the personal stigma scale (0.51-0.65). No single item deletion improved the internal consistency of the personal stigma scale above 0.78.

The personal stigma items satisfied the requirements for carrying out a PCA (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test 0.71; Bartlett’s test of sphericity P<0.001). The PCA conducted to examine the four items on the personal stigma scale yielded only one factor with an Eigen value greater than one (2.3) and this one factor accounted for 63% of the variance of the four items in the personal stigma questionnaire. All of the four questions loaded heavily onto this one extracted factor, with correlations of 0.71-0.84 found. Item-total correlations and internal consistency of the personal stigma scale (see above) were reasonably strong and supported that items on the same factor were measuring the same construct (i.e. personal stigma).

The mean level of perceived public stigma was 2.82 (s.d. = 0.66), which was substantially higher than the mean level of personal stigma (1.90, s.d. = 0.64) (F = 6.418, d.f. = 16, P = 0.001). The associations between the demographic characteristics and perceived public and personal stigma are displayed in Table 2. There were more significant associations with higher personal stigma scores than with perceived public stigma scores identified in our study sample.

Table 2 Associations of mean perceived public and personal stigma levels with sociodemographic and clinical variables

| Perceived public stigma | Personal sigma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) | t-test | d.f. | P Footnote a | Mean (s.d.) | t-test | d.f. | P Footnote a | |

| Gender | 1.146 | 733 | 0.252 | 1.212 | 733 | 0.296 | ||

| Male | 2.86 (0.59) | 1.95 (0.61) | ||||||

| Female | 2.80 (0.69) | 1.89 (0.65) | ||||||

| Age, years | 0.086 | 733 | 0.932 | 3.169 | 733 | 0.002Footnote * | ||

| <25 | 2.82 (0.65) | 1.94 (0.64) | ||||||

| >25 | 2.81 (0.71) | 1.74 (0.63) | ||||||

| Nationality | -2.008 | 733 | 0.045Footnote * | -2.637 | 733 | 0.009Footnote * | ||

| Irish | 2.80 (0.66) | 1.89 (0.63) | ||||||

| Other | 2.94 (0.71) | 2.17 (0.74) | ||||||

| Sexuality | 0.153 | 731 | 0.879 | 0.772 | 731 | 0.772 | ||

| Heterosexual | 2.81 (0.66) | 1.90 (0.64) | ||||||

| Homosexual | 2.79 (0.68) | 1.86 (0.69) | ||||||

| History of mental illness | 1.348 | 733 | 0.178 | -6.501 | 733 | 0.001Footnote * | ||

| Yes | 2.91 (0.80) | 1.50 (0.61) | ||||||

| No | 2.81 (0.64) | 1.96 (0.62) | ||||||

| Prior treatment for mental illness | 0.195 | 733 | 0.846 | -6.253 | 733 | 0.001Footnote * | ||

| Yes | 2.83 (0.75) | 1.59 (0.61) | ||||||

| No | 2.82 (0.65) | 1.96 (0.63) | ||||||

| Treatment with: | 0.573 | 107 | 0.568 | -1.975 | 107 | 0.063 | ||

| Medication | 2.87 (0.78) | 1.44 (0.52) | ||||||

| Counselling | 2.78 (0.70) | 1.65 (0.66) | ||||||

| Knowledge of someone with mental illness | 1.149 | 733 | 0.251 | -1.875 | 733 | 0.179 | ||

| Yes | 2.84 (0.71) | 1.76 (0.63) | ||||||

| No | 2.79 (0.61) | 2.01 (0.60) | ||||||

| Self-perceived need for mental health treatment in the past year | 2.485 | 733 | 0.013Footnote * | -4.542 | 733 | 0.027Footnote * | ||

| Yes | 2.88 (0.69) | 1.79 (0.65) | ||||||

| No | 2.76 (0.63) | 2.01 (0.61) | ||||||

| Would you seek help for a mental health problem in the next year? | 0.107 | 733 | 0.915 | -2.590 | 733 | 0.10Footnote * | ||

| Yes | 2.82 (0.66) | 1.88 (0.62) | ||||||

| No | 2.81 (0.68) | 2.04 (0.71) | ||||||

a. Independent sample t-test.

* P<0.05.

With respect to the items on the personal stigma scale, 93% (n = 681) of the sample agreed with the statement that they would gladly have someone who has received treatment for a mental illness as a close friend, and 86% (n = 635) reported that they would regard someone who has received mental health treatment to be as trustworthy as someone who has not. In total 92% (n = 675) reported that they would not think less of someone for having received mental health treatment and 58% (n = 429) reporting that they would date someone who has received mental health treatment.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess for significant differences between mean levels of perceived public stigma within a number of groups (Table 3). Personal stigma was found to be significantly elevated in those younger than 21, in comparison to those in the other age groups (F = 4.647, d.f. = 3, P = 0.03) and specifically in comparison to those in the 22-25 age group (mean difference 0.20, s.e. = 0.06, P = 0.019).

Table 3 Associations between perceived public stigma and sociodemographic and clinical variables

| Perceived public stigma Mean (s.d.) |

F | d.f. | P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range, years | 0.230 | 3 | 0.876Footnote b | |

| 17-21 | 2.81 (0.64) | |||

| 22-25 | 2.79 (0.75) | |||

| 26-35 | 2.88 (0.59) | |||

| >35 | 2.83 (0.98) | |||

| Ethnicity | 2.862 | 4 | 0.023Footnote c | |

| Irish | 2.80 (0.66) | |||

| British | 2.93 (0.67) | |||

| European | 3.04 (0.52) | |||

| American | 2.76 (0.85) | |||

| Asian | 3.34 (0.57) | |||

| Friends/family with mental illness | 1.701 | 3 | 0.149Footnote b | |

| Friend | 2.76 (0.68) | |||

| Relative | 2.96 (0.70) | |||

| Partner | 2.75 (1.13) | |||

| Acquaintance | 2.83 (0.57) | |||

| Prior treatment received | 0.952 | 2 | 0.389Footnote b | |

| Medication | 3.15 (0.73) | |||

| Counselling | 2.79 (0.70) | |||

| Both | 2.81 (0.79) | |||

| Person you would speak with if you experienced a mental health problem | 0.298 | 4 | 0.879Footnote b | |

| Doctor | 2.81 (0.67) | |||

| Counsellor | 2.83 (0.64) | |||

| Family | 2.78 (0.64) | |||

| Friend | 2.87 (0.72) | |||

| Faculty member | 2.83 (0.80) | |||

| No one | 2.81 (0.68) |

a. One-way ANOVA.

b. Scheffe post hoc criterion did not detect significant differences between group means for these variables.

c. The mean level of perceived public stigma was increased in those of Asian nationality compared with Irish students (mean difference 0.54, s.e. = 0.20, P = 0.123) and compared with American students (mean difference 0.58, s.e. = 0.22, P = 0.167) but this was not of statistical significance.

In Table 4, we show the estimated associations between non-help-seeking intention and mean personal stigma levels, mean perceived public stigma levels, history of mental illness and personal contact with someone with a history of mental illness. The odds ratio for personal stigma of 1.44 is statistically significant (P = 0.043), indicating that higher personal stigma is associated with a likelihood of non-help-seeking intention for any future mental health problem. In contrast, the odds ratio for perceived public stigma (OR = 0.871) is not statistically significant (P = 0.428). Those who had personal contact with an individual with a history of mental illness had a significant association with non-help-seeking intention (OR = 1.868, 95% CI 1.213-2.875). There was no significant relationship between a history of mental illness and the likelihood of not displaying a help-seeking intention for a mental health problem.

Table 4 Explanatory variables and associations with non-help-seeking intention (bivariate logistic regression)

| B | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean perceived public stigma | -0.138 | 0.428 | 0.871 (0.619-1.226) |

| Mean personal stigma | 0.365 | 0.043Footnote * | 1.44 (1.01-2.05) |

| History of mental illness | -2.70 | 0.446 | 0.763 (0.381-1.529) |

| Personal contact with a person with a history of mental illness | 0.625 | 0.005Footnote * | 1.868 (1.213-2.875) |

R 2 = 0.057 (Nagelkerke); model: χ2 = 15.926, d.f. = 4, P = 0.003.

* P<0.05.

Discussion

Main findings

In this population of university students, perceived public stigma was not a predictor of non-help-seeking intention. This finding is consistent with other studies that have also failed to identify an association between perceived public stigma and mental health help-seeking intention, Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer16,Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26,Reference Golberstein, Eisenberg and Gollust30 and further indicates that perceived public stigma may not be as strong a barrier to mental health utilisation, as has previously been suggested. Perceived public stigma levels were higher than personal stigma levels in our study population, a finding that has been mirrored in other cross-sectional studies. Reference Calear, Griffiths and Christensen22,Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26,Reference Griffiths, Nakane, Christensen, Yoshioka, Jorm and Nakane31 This divergence may suggest that students have an inflated view of public stigma and this finding may serve as an opening for future initiatives to focus on reducing levels of perceived public stigma. Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26 The findings that over 90% of students would accept someone with a history of treatment for a mental illness as a close friend could be advertised as part of a social norms campaign to reduce perceived public stigma among students.

Personal stigma was measured using a newly constructed scale that showed validity and reliability. Our study showed that this pilot measure of personal stigma was negatively associated with future help-seeking intention. The association between heightened personal stigma and decreased help-seeking intention for mental health problems has been demonstrated in other studies, Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26,Reference Cooper, Corrigan and Watson32 including among an adolescent population where its impact on treatment retention was highlighted. Reference Evans, Foa, Gur, Hendin, O'Brien and Seligman33 Further, the lack of an association between perceived public stigma and help-seeking is consistent with other studies that have found no similar association. Reference Brown, Conner, Copeland, Grote, Beach and Battista34,Reference Roeloffs, Sherbourne, Unutzer, Fink, Tang and Wells35 This association between personal stigma and a decreased likelihood to access help for a mental health problem compared with the insignificant association between perceived public stigma and help-seeking would suggest that personal stigma is a more significant barrier to mental health treatment utilisation in this university population.

A prior history of mental illness was not predictive of future help-seeking intention, but an interesting finding was that personal contact with someone with a history of a mental illness was associated with a decreased likelihood of accessing help for a mental health problem in the future. This is not wholly consistent with evidence from previous studies which indicate that stigma is diminished through contact with individuals who have received treatment for mental illness. Reference Corrigan6,Reference Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam and Sartorius36 However, it may be explained through negative experiences that individual students have had with a person who they know to have a mental illness, by negative accounts which they received from the person regarding the treatment that they got for their mental illness or by not having close social contact with the person. This is an area that stigma reduction campaigns could focus on by aiming to increase the degree of first-hand factual information that students receive regarding mental illness and the effectiveness of mental health treatment. This would allow for more informed decisions to be made by students regarding mental illness and to increase confidence in the effectiveness of treatments in order to reduce stigma. It would also provide impetus to allow for service user participation in such a programme, Reference Schomerus, Auer, Rhode, Luppa, Freyberger and Schmidt17,Reference Alonso, Buron, Rojas-Farreras, de Graaf, Haro and de Girolamo37 thus demystifying mental illness to a greater extent.

Perceived public and personal stigma was higher in students of Asian ethnicity, which highlights the difficulties that may exist in engaging this cohort of students who may find the academic environment particularly stressful due to the acculturation process that they are faced with. Personal stigma was increased among certain student groups including the younger students, with a significant elevation among the youngest age group noted and this is consistent with findings from other studies. Reference Calear, Griffiths and Christensen22,Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin26 Pleasingly there were lower levels of personal stigma among students who had a history of mental illness; in those who had previously received treatment for mental illness and in those who had perceived a need for help in the previous year. This is encouraging as it may indicate that this group of students who have had prior experience of mental health problems will be less impeded in seeking help on an ongoing basis or in the future. However, it is also notable that although 15% of students reported receiving treatment for a mental health problem in the past year, there was 48% who felt that they needed help for an emotional or mental health problem in the same period. This would indicate that a majority of students had not engaged in seeking clinical help for their problem, a finding which has been mirrored in other studies. Reference Blanco, Okuda, Wright, Hasin, Grant and Liu9 It may be partially accounted for in our study population by the high proportion of students who identified non-clinical sources of support including family members or friends.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the large study population that was a representative sample from the university population, which further improves the generalisability of the study findings. The study had a cross-sectional design, which used self-reporting to identify future help-seeking intention. The lack of a longitudinal design prevents us from establishing a causal relationship between stigma and help-seeking intention. A prospective study design would be a useful future step in order to overcome this limitation. We did not assess the impact of individuals’ perceptions of the effectiveness of mental health treatment on help-seeking intention or indeed on stigma levels, which could have been a confounding factor. We had limited information on the clinical status of the participants at the time of the study, which may have acted as an additional confounding factor, as someone who is actively depressed, for example, may display different treatment-related intention to someone who is anxious or who is highly distressed but without evidence of a clinical disorder. Reference Brown, Conner, Copeland, Grote, Beach and Battista34 The use of a scale to measure personal stigma that has not been previously validated may have led to a measurement bias been introduced into the study.

Stigma reduction campaigns

The need to establish more productive campaigns to reduce stigma in this population is essential in order to increase their utilisation of mental health treatments. The finding that 16% of this study population would not speak to anyone if they were to experience a mental health or emotional problem is particularly worrying in the context of the documented increase in the rates of youth suicide internationally in the past 30 years, Reference Wasserman, Cheng and Jiang38 which is mirrored in Ireland where the rate of youth suicide is the fourth highest in the European Union for 15- to 24-year-olds. 39

A focus of future stigma reduction campaigns should be on reducing personal stigma. Findings from our study suggest that this could lead to increased help-seeking intention. The university setting offers many channels through which a more positive effect on mental health may be founded. Reference Hunt and Eisenberg40 It provides a single integrated setting that encompasses the major activities in the lives of the student population, namely social and career-based activities. It also provides an appropriate setting for the provision of health services, including mental health services that can have both a preventive and treatment-based role in order to ensure an improvement in the utilisation of services for students and a reduction in morbidity relating to mental disorders. The challenge remains in implementing successful stigma reduction programmes in order to enhance service utilisation in this population and to make more lasting changes to their attitudes towards mental illness and treatment.

Appendix 1

Adapted Devaluation-Discrimination (Perceived public stigma) scale

Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements.

-

1. Most people would willingly accept a person who has received mental health treatment as a close friend.

-

2. Most people believe that a person who has received mental health treatment is just as intelligent as the average person.

-

3. Most people believe that a person who has received mental health treatment is just as trustworthy as the average citizen.

-

4. Most people would accept a fully recovered person who has received mental health treatment as a teacher of young children in a public school.

-

5. Most people feel that receiving mental health treatment is a sign of personal failure.*

-

6. Most people would not hire a person who has received mental health treatment to take care of their children, even if he/she had been well for some time.*

-

7. Most people would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment.*

-

8. Most employers will hire a person who has received mental health treatment if he/she is qualified for the job.

-

9. Most employers will pass over the application of a person who has received mental health treatment in favour of another applicant.*

-

10. Most people in my community would treat a person who has received mental health treatment just as they would treat anyone else.

-

11. Most people would be reluctant to date a man/woman who has received mental health treatment.*

-

12. Once they know a person was in a mental hospital, most people will take his opinions less seriously.*

Appendix 2

Personal stigma scale

Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements.

-

1. I would willingly accept a person who has received mental health treatment as a close friend.

-

2. I believe that a person who has received mental health treatment is just as trustworthy as the average citizen.

-

3. I would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment.*

-

4. I would be reluctant to date a man/woman who has received mental health treatment.*

All items are answered from: Strongly agree, 1; Agree, 2; No opinion, 3; Disagree, 4; Strongly disagree, 5.

Items with a * are reverse scored, i.e. ‘Strongly agree’ corresponds to 5 points instead of 1 point.

Appendix 3

Your views on mental health

We would appreciate if you could take a few minutes to complete the following survey. Please mark the most appropriate box with an X

In the past year have you received treatment for mental health problems? Yes/No

If Yes, did you receive 1. Medication 2. Counselling 3. Both

If mental health problems were affecting your academic performance who would you talk to? Doctor/Counsellor/Family/Friend/Faculty member/Religious service/No one

In the past year, did you think you needed help for emotional or mental health problems such as feeling sad, blue, anxious or nervous? Yes/No

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.