Introduction

Roman urban communities made use of circular economic models in many respects: repair, curation, lateral cycling, and recycling were all activities well-rooted in the economic system, drawing from a long experience and mindset (Duckworth & Wilson, Reference Duckworth and Wilson2020; Furlan, Reference Furlan2023; Bavuso et al., Reference Bavuso, Furlan, Intagliata and Stedingforthcoming). Among the processes involved, largely but not exclusively grouped under the umbrella term of reuse, recycling, i.e. ‘the return of an artifact after some period of use to a manufacturing process’ (Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1996: 29), certainly had a substantial impact on some categories of material, particularly glass and metals.

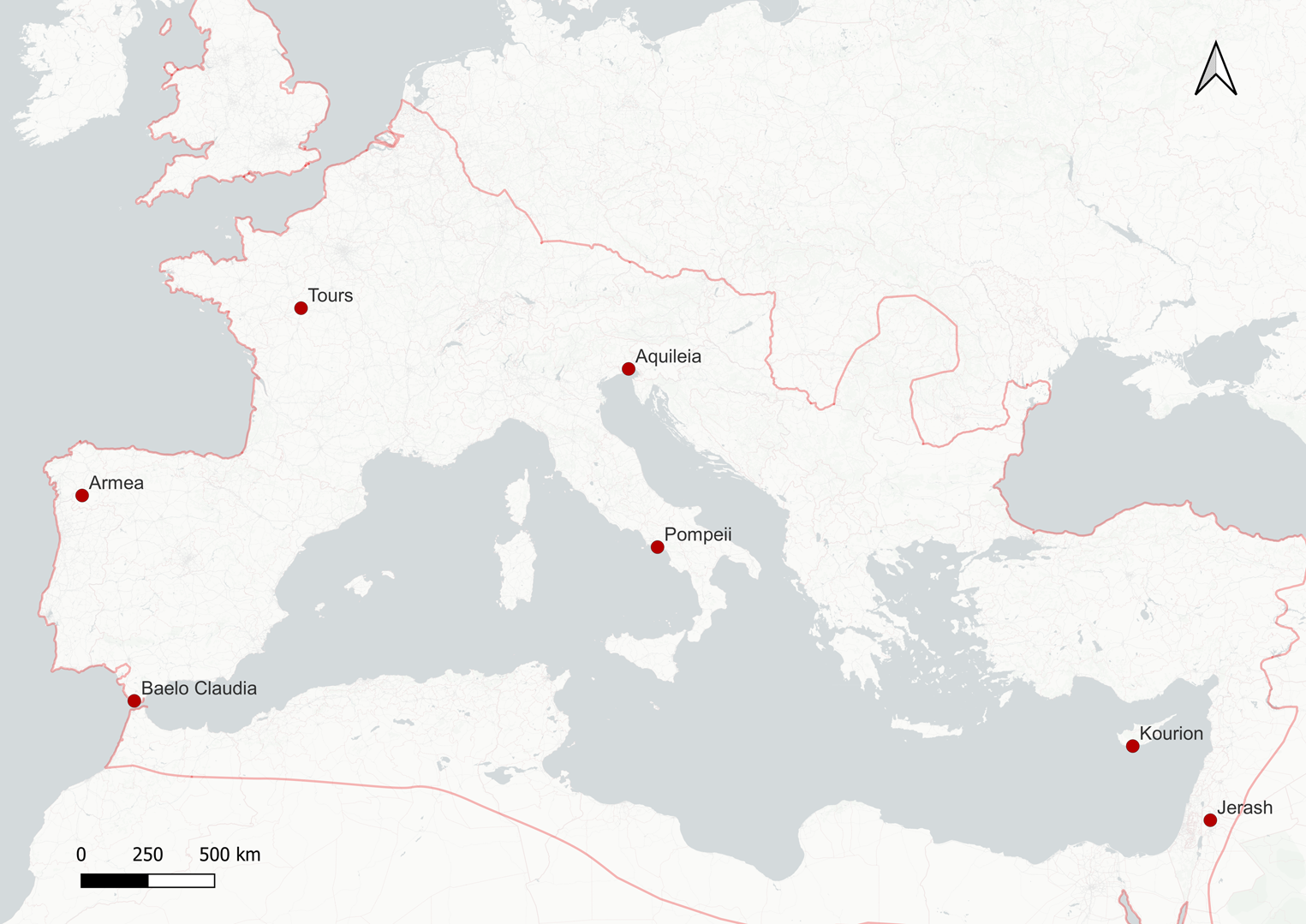

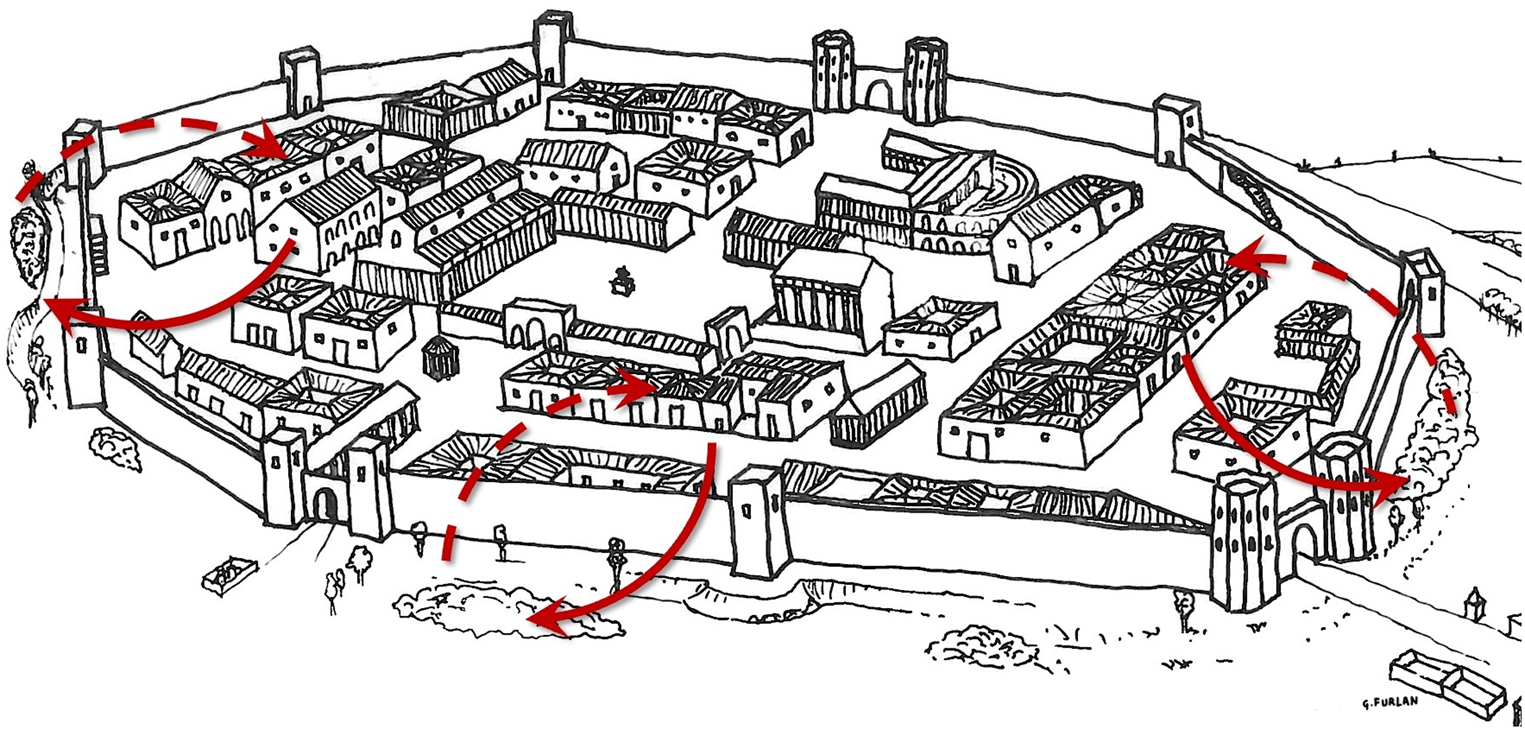

Recycling took place within urban waste management systems (Figure 1). The Roman approach to urban waste shared some aspects with the systems adopted in other cultural, geographical, and temporal contexts (see Hayden & Cannon, Reference Hayden and Cannon1983; Needham & Spence, Reference Needham and Spence1997; Beck, Reference Beck2006), but also had its own specific features (Raventós & Remolà, Reference Raventós and Remolà2000; Ballet et al., Reference Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003; Furlan, Reference Furlan2017). In general, solid rubbish generated in domestic or productive areas could be provisionally discarded, stored, or hoarded, but then was routinely collected and transported outside the city walls, where it accumulated in mounds or filled riverbeds and cavities. Between initial discard and final deposition, what was considered worth being reused (and, specifically, recycled) was collected, re-entering the economic system.

Figure 1. Simplified model of the ‘waste stream’ of a Roman town. Reuse practices can occur at different stages.

The recycling of glass and metals in the Roman world has been variously attested in the archaeological record, written sources, and archaeometric analyses (e.g. Keller, Reference Keller, Bruhn, Croxford and Grigoropoulos2005; Freestone, Reference Freestone2015; Pollard et al., Reference Pollard, Bray, Gosden, Wilson and Hamerow2015; Bray, Reference Bray, Duckworth and Wilson2020; Duckworth, Reference Duckworth, Duckworth and Wilson2020); this documentation provides an outline of the dynamics, networks, and agents involved. Conversely, the economic impact of glass and metal recycling on the local, urban economies remains understudied. This seems to be largely due to three factors:

1) a lack of extensive archaeometric analyses, difficult and expensive to conduct on large enough assemblages

2) the quality of the available archaeological data, consisting of finds from very disparate types of contexts, each with their own taphonomical issues

3) multiple recycling, as glass and most metals could be remelted more than once.

The first and third factors mostly belong to the sphere of archaeometry, but the second can be tackled along more traditional archaeological lines. Here, we compare primary assemblages, which reflect (as much as can be ascertained) the systemic context of Roman towns (for the difference between systemic context and archaeological context, see Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1972), with extra-urban rubbish assemblages to determine the effectiveness of glass and metal recycling in the urban economy.

The chronological and spatial limits of our study were determined by the available evidence and its nature. The introduction of glassblowing in the second half of the first century bc, which substantially changed the glass vessel market (Stern, Reference Stern1999; Grose, Reference Grose2017: 9; Larson, Reference Larson2019; Jackson & Paynter, Reference Jackson and Paynter2022), represents a terminus post quem for this study. Our article mainly focuses on early and mid-imperial contexts from the western Roman Empire, but also includes two comparative case studies from late imperial Kourion in Cyprus and early medieval Jerash in Jordan (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location of the sites included in the study (map by M. Coto Sarmiento using QGIS 3.22 3.22.6-Biał owieża with CARTO Positron basemap. Roman Empire border added by A. Pažout using Ancient World Mapping Center (https://awmc.unc.edu/wordpress/).

Methodology

Any archaeological assessment of the intensity of urban recycling is conditioned by a variety of factors and possible biases; some cannot be eliminated, but their impact can at least be roughly modelled and evaluated. In any event, reducing potential biases to a minimum is the basic principle followed.

A first consideration concerns the preservation of glass and metals in the archaeological record. Roman glass is considered very durable (Davison, Reference Davison2003: 169–98); it can disintegrate completely under certain burial conditions but in none of our case studies does this seems to have happened to a significant degree. A similar situation can be assumed for metals: although displaying different rates of corrosion, even small metal items were recovered in each site we examined, and their complete disintegration can be ruled out as a significant bias.

In order to assess the effectiveness of glass and metal recycling, a first step consists of measuring how much of these materials was in use in an urban settlement. This is hardly achievable in absolute terms, but can be ascertained in terms of relative proportions and expressed as a percentage.

Systemic assemblages (all materials circulating, or otherwise in use, or temporarily stored in a town in a given period) are normally composed of materials of different types. The degree of survival of organic finds is heavily affected by variable rates of decay; therefore they cannot be used for reliable comparison. Building materials must also be excluded, as their discard is often the result of discrete, scattered episodes of refurbishment rather than regular building operations.

Ceramics are the most reliable for comparison, as they are non-perishable and were part of the everyday life of any Roman town; their abundance also makes them a sound benchmark from a quantitative perspective. Pottery was also commonly recycled, as temper in bricks and other ceramic vessels or as aggregate in mortars (Peña, Reference Peña2007: 263; Siddall, Reference Siddall, Ringbom and Hohlfelder2011); given the enormous amounts of pottery involved, we can assume that recycling had a relatively limited quantitative impact, even with a substantial proportion of ceramics being recycled. Finally, using ceramics as a benchmark should remain valid, as long as the incidence of recycling can be roughly modelled as constant in different urban contexts. The systemic quantity of glass and metal can therefore be measured in proportion to the total sum of ceramics, glass, and metal.

Among metals, an important distinction must be made: coins were withdrawn from circulation according to specific procedures, sharing little with common rubbish disposal (see e.g. Chameroy & Guihard, Reference Chameroy and Guihard2016). We have therefore deliberately excluded coins when counting metals.

Having selected a consistent benchmark to measure the relative abundance of glass and metal, the major issue is the selection of appropriate contexts, the ideal contexts being those least affected by depositional and post-depositional factors that would alter their capacity to show what was in use in a given space at a given moment. Primary urban contexts, little or not affected by long abandonment processes (therefore containing what is de facto rubbish minimally affected by curate behaviour; Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1996: 89–90), are the ideal target. Episodes of fire, earthquakes, or volcanic activity suddenly sealing a domestic or productive assemblage are rare in the archaeological urban record. Yet they can provide the most reliable picture of what was in use in a Roman town at a given time. The selection of appropriate contexts, as far as possible, includes an assorted mix of high- and low-status dwellings, as well as production facilities, the aim being to reflect as much as can be ascertained the whole urban systemic assemblage.

These archaeological contexts are then compared to contexts that formed at the other end of the rubbish stream, namely the communal extramural urban dumps. Again, the incidence of glass and metals is measured as a percentage of the total amount of glass, metals, and ceramics. At this point, any difference in the internal proportions of glass, metals, and ceramics between the two set of contexts can be largely explained by two main factors, namely: 1) the different use life (or replacement ratios) of objects made of different materials; and 2) the impact of recycling.

The first factor is difficult to model given the scant data available. Some models for the use life of certain classes of Roman pottery have been proposed (Peña, Reference Peña2007), but, to our knowledge, there are no models for glass and metalware. We can assume that the typical life of a metal vessel was longer than that of a ceramic vessel, and therefore must have reached the dumping sites less often. Given their function, items such as nails and appliques can be expected to have lasted for a long time. The same would apply to precious objects made of silver and gold. Quantifying the phenomenon, however, remains problematic. Glass is more fragile than pottery (mostly because the vessels’ walls are much thinner), but glassware was probably handled with more care and typically employed for more delicate purposes. Achieving a reliable figure, is, again, very difficult. Lastly, low replacement ratios (either due to normal use or to proper curation) and recycling are not mutually exclusive, as they can both involve the same object.

If a quantitative approach cannot accurately distinguish between the two factors, a qualitative approach, which examines the characteristics of the artefacts recovered, can attest to the existence of practices of recycling. In our study, after narrowing down the field through a numeric approach, our focus will therefore switch to a closer qualitative look at the assemblages recovered from dumping areas, to highlight the role played by recycling as opposed to different replacement ratios. This approach does not allow us to address the question of multiple episodes of recycling, but it does permit us to set a minimum threshold for recycling; it indicates the lowest figure for the impact of recycling in the Roman economy, giving us at least an approximate estimate of its effectiveness.

Considerations concerning quantification

Weight is the ideal parameter for measuring the relative proportions of materials involved in rubbish disposal and recycling, as each recyclable artefact is relevant only as a raw material to be reintroduced to the productive system. It also makes comparisons easier and straightforward. Unfortunately, this simple assumption is at odds with the most common type of data available for assemblages, namely finds counts.

For testing possible distortions, absolute numbers and relative percentages from two different rubbish contexts (from the Sarno Baths in Pompeii and Tours, see below), where both weight and finds count were available, were examined (Table 1). In an attempt to reduce possible discrepancies, the number of finds has also been multiplied by the average specific weight of each material, which varies according to the composition of ceramics, glass, and metal alloys; we used a figure of 2.8 kg/dm3 for ceramics, 2.2 kg/dm3 for glass, and 7.87 kg/dm3 for metals. The latter refers to the specific weight of iron. The specific weight of bronze depends on the quantity of tin in the alloy, which varies between eight per cent and fourteen per cent, implying a variation of the specific weight between 7.4 kg/dm3 and 8.9 kg/dm3. As the specific weight of iron lies in the middle, it was chosen as an approximation of the average specific weight of metals as a whole.

Table 1. Presence of glass, metal, and ceramics at Pompeii's Sarno Baths and Tours. The last column shows how the percentages vary if the number of finds is multiplied by the average specific weight of the three materials.

*The assemblage included 157 further objects, counted as individual items, but their weight was not available. It is unlikely that their count significantly affected the percentages presented here.

In both contexts, the finds count overemphasizes the presence of glass and metals, but adjusting the number of finds by specific weight does not appreciably improve the figures indicated by the simple weight. This seems to be largely due to the size of the finds: glass and metal finds recovered in dumps are considerably smaller than the average pottery sherds. It also implicitly confirms the impact of the upstream selection and collection for recycling, as only the smallest fragments and objects slipped through the system, the larger fragments of glass and metal being mostly absent from the dumps. Unfortunately, it was not possible to make the same observations on primary contexts intra moenia (inside the city walls), which may have provided a more complete picture.

Given the available data, we decided to compare finds count percentages, simply acknowledging that the results overemphasize the presence of glass and metals in dumps. This implies that any variations in percentage must be substantial to be perceived. One last remark concerns fragility and fragmentation, which does not only influence replacement ratios. In primary contexts, one find often corresponds to a complete, well-preserved object, whereas in dumping sites, it generally (but not exclusively) refers to a fragment. This may be a distorting factor, as this applies more or less uniformly to glass and ceramic finds, but not to metals; the latter break much more rarely and may theoretically lead to underestimating the percentage of metals in dumps. We shall, however, see that the characteristics of the metals recovered in dumps largely eschew this problem.

Metal and Glass Recycling in Pompeii

Given the necessity of reducing bias to a minimum, Pompeii at the time of its devastation in ad 79 constitutes an ideal case study. Clearly, some factors distorted the composition of certain assemblages, namely curate behaviour before and after the eruption of Vesuvius and refurbishing caused by the earthquake that affected the Vesuvian sites in ad 62/63. Nonetheless, the events leading to the sealing of the city were so sudden and irreversible that, from our point of view, the impact of these factors can be considered, if not negligible, at least incomparably lower than the sum of depositional and post-depositional processes affecting the archaeological record of most Roman urban sites.

The oldest excavation reports concerning the ad 79 phase of the city mostly do not contain reliable quantitative data, notably because of the selection criteria of investigations conducted before stratigraphic methods became current. For this reason, some groups of artefacts recovered in the nineteenth century, although thoroughly reassessed recently (Sigges, Reference Sigges2001; Coralini, Reference Coralini2018; Berg, Reference Berg, Berg and Kuivalainen2019: 56; Berg & Kuivalainen, Reference Berg and Kuivalainen2019), could not be used; only data from some recent excavations and the study of early to mid-twentieth-century excavation journals provide sufficient evidence to address our topic. This does not entirely rule out the possibility that some twentieth-century excavations were still privileging whole and precious artefacts over coarse pottery. Nonetheless, this bias can be considered less relevant and more occasional than systematic. Comparative case studies of other sites (see below) can also test, at least to some extent, the reliability of older Pompeian archaeological data relevant to our study.

The primary contexts

The online companion to Allison's (Reference Allison2006) publication of the finds of the Insula of the Menander (Allison, Reference Allison2021) provides a first, fundamental dataset. The database gives a full list of finds, based on the accurate examination of the old ‘giornale degli scavi’ (unpublished excavation reports held in the archives of the Soprintendenza) of the early twentieth century.

The insula included not only the large domus (house) of the Menander (Regio I, Insula 10, Entrance 4), but also smaller dwellings and tabernae (shops/stalls), therefore providing a cross-section of the systemic assemblage of a whole Pompeian insula. We considered a total of 3581 finds, including 2416 metal finds (67.5 per cent; any multi-material find with metal parts was counted as one metal find), 864 ceramic finds (24.1 per cent), and 301 glass finds (8.4 per cent). The assemblage comprises a silverware hoard that certainly belonged to the main household.

The second context examined is that from the House of Epidius Primus, a medium-sized atrium house located in Regio I, Insula 8, excavated in 1938 and 1941. Part of the assemblage, including bronze and silverware, was recovered in a wooden box. Again, examination of the ‘giornale’ made it possible to publish a list of the finds attributable to the ad 79 phase of the house (Berry, Reference Berry, Laurence and Wallace-Hadrill1997). A total of 467 finds included 229 finds of metal, 102 of glass, and 136 of ceramic. The percentage of metalware is close to half of the whole assemblage, ceramics roughly make up thirty per cent of the finds, and glass some twenty per cent.

Assemblages recovered in the remaining part of Regio I, Insula 8, have been published by Castiglione Morelli and Vitale (Reference Castiglione Morelli and Vitale1989). The insula was investigated in 1912 to a limited extent, and then fully uncovered between 1936 and 1941. This quarter constitutes a valuable socio-economic sample, as it includes, besides the House of Epidius Primus, other medium-sized domus, smaller dwellings, tabernae, and officinae (workshops).

We discounted some of the published case studies, either because they returned very few artefacts (locations may have been empty at the time of the eruption) or were insufficiently reliable (failure to recover the whole assemblage, post-depositional reclamation). Eventually, twelve contexts were selected: the taberna pomaria (fruit stall) of Felix, the House of Stephanus, Taberna 1.8.4, the House of the Indian Statuette, Taberna 1.8.6, the caupona (inn) and House of L. Vetutius Placidus, the hospitium (lodgings) and caupona of Pulcinella, the stabulum (stable) 1.8.12, the officina of A. Granius Romanus, the caupona and officina pigmentaria (paint or unguent workshop) of N. Fufidius Successus, the Casa dei Quattro Stili (House of the Four Styles), and the House of Balbus. Together they provided 511 finds, including 227 of metal (44.4 per cent), 185 of ceramic (36.2 per cent), and ninety-nine of glass (19.4 per cent).

Data are also available for the peri-urban villa rustica known as Villa Regina in Boscoreale, located about 1 km outside the north-western boundary of Pompeii; this villa was discovered in 1977, and therefore its data are reliable. In another nearby villa (at Pisanella), a basket filled with cullet (waste glass ready to be recycled) was found in older excavation campaigns (Keller, Reference Keller, Bruhn, Croxford and Grigoropoulos2005: 66). Although located outside the city walls, Villa Regina belonged to the Pompeian urban network, sharing access to its market. Overall, the villa and its assemblage reflect the life of a farmer of medium status, well connected to the intra moenia community. Out of 182 finds (De Caro, Reference De Caro1994), ninety-two are of metal, eighty-six of ceramic, and four of glass. This is the lowest percentage of glassware attested. It must be stressed that, although there is no bias in the recovery, metals still make up about half of the whole assemblage.

From a qualitative point of view, the vast majority of the 4741 finds selected in Pompeii for our study consist of whole items or by fragmented objects that could be reconstructed to a great degree and therefore counted as one specimen.

The rubbish mound south of the Sarno Baths

In 2016, within the framework of the project MACH (Multidisciplinary methodological Approaches to Cultural Heritage) – Pompeii (Artioli et al., Reference Artioli, Ghedini, Modena, Bonetto and Busana2019), it became possible to investigate the area located right in front of the Sarno Baths façade in Pompeii (Regio VIII, Insula 2, nos. 17–21), exactly at the boundary of the plateau hosting the settlement. The area, sloping southward towards marshland (Nicosia et al., Reference Nicosia, Bonetto, Furlan and Musazzi2019), had long been used for dumping waste from the city, until it was covered by pumice in ad 79 (Furlan et al., Reference Furlan, Bonetto and Nicosia2019).

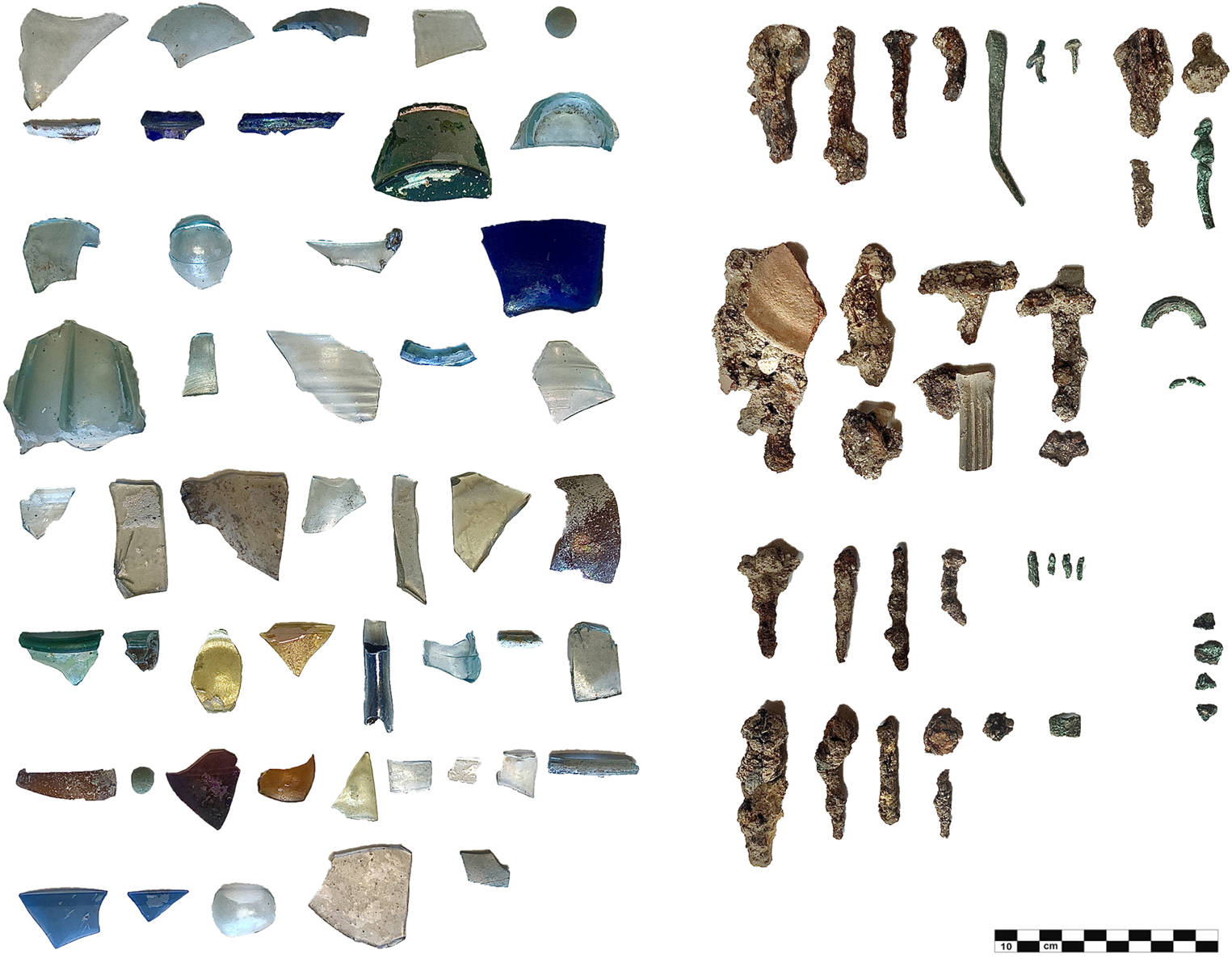

For this study, only the rubbish layers deposited approximately between ad 50 and 79 (context numbers 64, 65, 38, 42, 43, and 41=46) were selected. A total of 1331 finds was considered, including thirty-eight of metal, forty-eight of glass, and 1245 of ceramic (Table 1). Glass is largely represented by small, light sherds, whereas metal, while less fragmentary, includes only small specimens (mostly nails, parts of fibulae, and pins), rarely larger than a few centimetres (Figure 3). There were no fragments certainly attributable to metal vessels, in contrast to the numerous sherds of ceramic vessels (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The glass and metal assemblage from the Sarno Baths dump in Pompeii.

Figure 4. A small sample of the ceramics recovered in the Sarno Baths dump.

Comparative considerations

The primary contexts are highly variable in their composition, but some main trends can be detected (Table 2).

Table 2. Proportions of glass, metal, and ceramics in primary contexts at Pompeii, compared with corresponding proportions from the Sarno Baths dump.

The proportion of ceramic finds in primary contexts ranges from a minimum of c. twenty-four per cent for the whole Insula of the Menander to a maximum c. forty-seven per cent at Villa Regina (mean 34.1 per cent). Glass is attested in lower quantities and varies greatly (2.2–21.8 per cent, mean 13 per cent). The presence in Roman urban assemblages of large numbers of metal items (44.4–67.5 per cent, mean 52.9 per cent) may appear surprising. We had anticipated that recovery strategies and discrepancies in older reports would result in an over-representation of precious materials over ceramics, but the case of Villa Regina seems to indicate that metals were truly an important part of domestic assemblages. Although we could not reprocess the whole assemblage, gross data reported for vessels in the House of Iulius Polibius also indicate that metalware was present in substantial quantities in Pompeian domestic assemblages (Castiglione Morelli, Reference Castiglione Morelli and Bats1996).

In a house in Regio VI, Insula 13, Entrance 16, another mid-sized atrium house, room 9, excavated in 2005, yielded a small assemblage dated to ad 79 (Mian & Tiussi, Reference Mian, Tiussi, Verzár-Bass and Oriolo2009); it included fifteen ceramic (71 per cent), six metal finds (29 per cent; one find consisted of three small objects, which were counted as one), and no glass; the presence of metal items, although low, is not negligible for a single room.

The percentage of glass and metal finds dramatically drops when we turn to the peri-urban rubbish mounds: metal is represented by less than three per cent (2.9 per cent) of the whole assemblage of the Sarno Baths dump, and glass by less than four per cent (3.6 per cent), usually consisting of very small, thin, and light fragments. Apart from building material, which was not counted, the assemblage consists largely of ceramics. The difference between the composition of the primary contexts and the dumping site is thus pronounced, and this leads us to our first conclusion.

Ceramics make up the vast majority of archaeological finds in any urban site, but urban palimpsests are usually composed of few primary contexts and many secondary deposits, often derived from rubbish through reclamation (Dicus, Reference Dicus, Platts, Pearce, Barron, Lundock and Yoo2014; Bonetto et al., Reference Bonetto, Furlan, Ghiotto, Cupitò, Vidale and Angelini2017; Figure 5). The relative, systemic presence of ceramics was clearly much more limited. In other words, the composition of the rubbish mound is closer to what can be expected when digging any archaeological site, but far from the actual composition of an urban assemblage.

Figure 5. The ‘cycle of rubbish’: after selecting what could be reused, waste was discarded outside the urban boundaries. When extramural materials (and sediments) were reclaimed, they re-entered the city, forming secondary deposits. The actual, systemic presence of glass and metal is, therefore, not reflected by these deposits.

Our next step was to determine the reasons for the marked drop in glass and metal in communal dumps. This dramatic change, also reflected in the state of the artefacts (from whole items to fragments), suggests that different replacement ratios cannot alone be responsible for this drop: if this were case, the dump would have contained old, but still largely whole, metal vessels. But, before discussing the reasons for this phenomenon, we will consider whether the picture that emerges from Pompeii is reflected on other urban sites in the Roman Empire.

Comparative Case Studies

To investigate whether the pattern detected at Pompeii is an anomaly or reflects a broader trend, we needed to bring other case studies into play. Again, the lack of published quantitative data limits the contexts we could study, particularly primary contexts, as undisturbed destruction layers are rare in urban sites. By widening the geographical and temporal focus, it is nevertheless possible to gather a reasonable amount of comparative evidence.

Primary contexts

The obvious counterpart for the Pompeian assemblages is represented by Herculaneum. Unfortunately, again, published quantitative data are rare and very early archaeological investigations in the eighteenth century, conducted by tunnelling, make some assemblages unreliable. Even some more recent accounts, based on the ‘giornale degli scavi’, seem suspicious. The complete publication of the Casa dei Cervi (House of the Stags) presents all the material recovered during the excavations of 1930 (Tran, Reference Tran and Tinh1988), excluding what was recovered during the eighteenth century. Leaving aside a few dubious cases, where the attribution to the house was uncertain, the material of interest includes forty-one ceramic (77.3 per cent), nine metal (17 per cent), and three glass (5.7 per cent) finds. One of the metal finds is a whole, large bronze bathtub. No small finds or coins are reported, nor any iron items; their presence in a large, rich house is more than probable and we must conclude that for some reason they were not recovered or recorded.

The Casa del Colonnato Tuscanico (House of the Tuscan Colonnade), although excavated in 1960 and 1961 and published in 1974, had been heavily tunnelled during the eighteenth century (Cerulli Irelli, Reference Cerulli Irelli1974: 12). Among the finds presented, several metal items are included, but no glass. This clearly contrasts with what is preserved in the local antiquarium, where glass vessels are said to represent more than thirty per cent of all vessels (note that this refers to vessels, not finds; Scatozza Höricht, Reference Höricht1986: 22; see also de Kind, Reference de Kind1998). J.P. Morel (Reference Morel and Zevi1984) had already stressed the importance of glass in the Vesuvian households, and there seems little doubt that in Herculaneum, too, metal and glass represented a relevant part of a typical systemic assemblage, although accurate quantification is difficult.

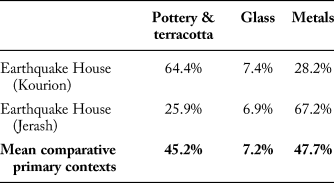

Apart from the Vesuvian sites, sealed primary contexts with little post-depositional activity are extremely rare, and among these, those excavated in a significant proportion and fully published are even fewer. The so-called Earthquake House at Kourion in Cyprus, although later in date, is a notable exception. The Earthquake House, so named because a dramatic earthquake at the end of the fourth century ad demolished it and effectively sealed its assemblage, is an urban dwelling that was almost completely excavated in 1934-35 and between 1984 and 1987. The pre-earthquake assemblage has been fully studied and published by Costello IV (Reference Costello IV2014). In total, 188 finds were included in our study, namely 121 ceramic, fifty-three metal (as usual, excluding coins), and fourteen glass finds.

The percentage of glass and metal finds is lower than the mean value attested in Pompeii. It is difficult to ascertain the reasons for this difference. However, from the perspective of our work, metal and glass items are still an extremely relevant part of the dwelling's everyday assemblage. As usual, the artefacts were largely complete or could be reconstructed.

In Jerash (Gerasa, Jordan) an earthquake sealed a dwelling in the so-called Northwest Quarter in ad 749; the house is not fully excavated, but the investigation of a few rooms (Lichtenberger et al., Reference Lichtenberger, Raja, Eger, Kalaitzoglou and Højen Sørensen2016) revealed part of an undisturbed assemblage in use at the time of the earthquake. We included this context in our study because, in the light of forms of continuity characterizing aspects of urban living in the former Roman Empire at least until the early Islamic period (the so-called ‘long Late Antiquity’), it is worth considering whether the composition of a later domestic assemblage differs markedly or not from the assemblages of earlier periods.

Given that the building has not been fully excavated, the small sample may not be representative of the whole: out of fifty-eight (complete or reconstructible) finds, thirty-nine are metal, fifteen are ceramic, and four are glass. The proportion of metalware and ceramics is nearly reversed compared to Kourion's Earthquake House, whereas the percentage of glass is substantially unchanged. The proportions appear very similar to those of the Insula of the Menander: metals are a relevant part of the domestic assemblage, and glass forms a small but appreciable part of it. Overall, the tendency discernible in Late Roman and post-Roman assemblages (Table 3) is broadly in line with what has been observed on the Vesuvian sites.

Table 3. Proportion of glass, metal, and ceramics in Kourion and Jerash.

Urban dumps

Urban dumps are still rarely explicitly targeted by archaeological investigations. Nonetheless, they were so ubiquitous that fieldwork occasionally intercepts these precious deposits. Some assemblages have been published (see Table 4), and they can be used to test what has been observed in the Pompeian dump at the Sarno Baths.

Table 4. Proportions of glass, metal, and ceramics in the comparative dumping sites examined.

Within a programmed emergency excavation in 1990–91, part of a peri-urban channel was excavated in Tours in western France (Dubant, Reference Dubant, Ballet, Cordier and Dieudonné-Glad2003). Extramural watercourses were privileged targets for dumping activities, and Tours was no exception. Part of the channel bed was filled with rubbish between the end of the first century ad and the beginning of the following century. As shown in Table 1, the excavation produced a considerable quantity of material, largely consisting of ceramics (96.6 per cent), with metal and glass minimally represented (respectively 1.4 per cent and 2 per cent).

Typically, dumps were located right against the city walls, as in Pompeii. This was the case of Baelo Claudia in southernmost Spain, where a large dumping area stretched along the outer perimeter of the south-eastern city walls (Bernal Casasola et al., Reference Bernal Casasola, Arévalo González, Muñoz Vicente, García Jiménez, Bustamante Álvarez, Sáez Romero, Remolà Vallverdú and Acero Pérez2011). The assemblage included 3869 finds, with 3380 ceramic, 326 glass and 163 metal finds. The percentage of ceramic finds, although still extremely high (87.4 per cent), is noticeably lower than expected, and glass is particularly well attested.

A third context is represented by the fill of an extramural artificial waterway at Aquileia, on the Adriatic coast in north-eastern Italy. For a long period, approximately between the later first century bc and the beginning of the fourth century ad, part of the canal was used to dump rubbish (Bonetto et al., Reference Bonetto, Furlan, Ghiotto and Missaglia2020). The extensive publication of the finds (Maggi et al., Reference Maggi, Maselli Scotti, Pesavento Mattioli and Zulini2018) makes it possible to include 2674 finds in our study, i.e. 2596 ceramic, sixty-nine glass and only nine metal finds. The percentages are very similar to those from Tours and Pompeii. The incidence of metal is, however, the lowest observed.

Finally, it was possible to evaluate the presence of glass and metal finds in the dumping site of a smaller centre, the Galaico-Roman site of Armea in Galicia. Here, a large quarry pit was filled with rubbish dated to between the end of the first century and the beginning of the second century ad. Out of 6122 finds, only 139 were of metal and fifty-nine of glass, whereas 5924 (about 96 per cent) were ceramics (see Rodríguez Nóvoa et al., Reference Rodríguez Nóvoa, Valle Abad, Fernández Fernández and Coll Conesa2019).

In sum, the data emerging from the examination of four dumping sites are consistent with what has been observed in Pompeii, strongly suggesting that extremely low percentages of glass and metal finds, as well as their fragmented state and small size, are the norm, the output of a systematic and widespread mechanism. Although it was not possible to fully quantify the data, similar patterns emerge from urban dumps in other major sites. A pre-ad 70 dump in Jerusalem (Bar-Oz et al., Reference Bar-Oz, Bouchnik, Weiss, Weissbrod, Bar-Yosef Mayer and Reich2007) contained negligible quantities of metal and glass (although partial disintegration of thin glass may have played a role); and a second-century ad dump from the slopes of the Gianicolo, in Rome, also produced similar results (Filippi, Reference Filippi2008).

Discussion

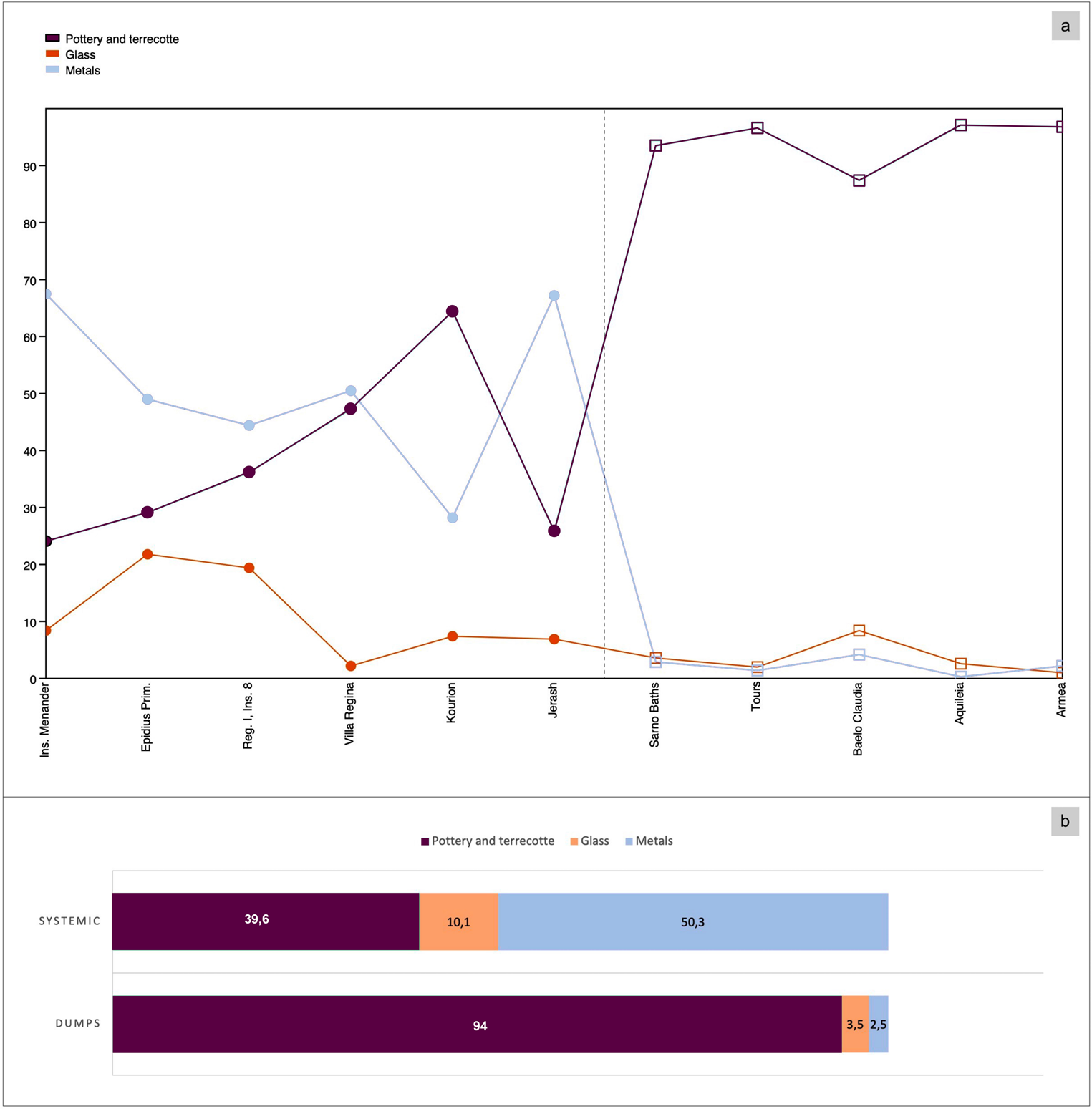

The difference between the incidence of metal and glass in sealed urban primary contexts and in urban dumps is clear (Table 5, Figure 6). Whereas, in contexts that reflect the actual assemblages in use, metals make up about half the assemblage and glass about one tenth, dumped materials contain more than ninety per cent of ceramics. While the percentage of glass decreases to a lesser extent, the drop in the incidence of metal items is dramatic. Expressing the same data in terms of weight, the drop would be even more pronounced. The substantial difference between urban primary contexts and urban dumps (or, to simplify, between consumption and discard) can be ascribed to different replacement ratios and to recycling.

Table 5. Global comparison of the proportions of glass, metal, and ceramics in primary contexts and in dumping sites.

Figure 6. Summary graphs. a: varying percentages of glasses, metals, and ceramics in the contexts examined (circle=primary context in situ; square=dumping site); b: overall difference in the percentage of glass, metals, and ceramics between primary contexts in situ and dumping sites.

At this point, we need to consider the state of preservation of the finds. In primary contexts, the finds are mostly either complete or conjoinable. In dumping sites, glass is mainly fragmentary, and metal consists of small items or fragments, indicating that they went through a process of selection. If longer replacement ratios alone were responsible for the low incidence of glass finds, then older, but still largely conjoinable, items should be recovered together with the ceramics. This is clearly not the case.

Concerning metals, we expected their lower breakage ratio to lead to underestimating their presence in dumps. However, what is usually recovered in dumps is small metal finds with low, although not absent, fragmentation. Metal vessels, usually larger (cauldrons, jugs, cups, etc.), were not recovered as complete objects and their fragments counted as one find. Wherever it could be ascertained (in Pompeii, Armea, Aquileia, and Baelo Claudia), they were simply absent, which implies that there is no bias owed to fragmentation.

We are left with only one reasonable explanation: a large part of what is missing was systematically remelted. The glass and metal we find in dumps is what escaped the collection of recyclable materials, an apparently exceptionally effective process. This appears to confirm what the few available written sources tell us. For glass, we know about the existence of a network of collectors who exchanged cullet for sulphur sticks (Leon, Reference Leon1941; Whitehouse, Reference Whitehouse1999), and it has been suggested, based on the Edictum de Pretiis (Edict of Prices issued by Diocletian in ad 301), that glassblowing could barely survive without systemically recycled cullet (Stern, Reference Stern1999). In Pompeii before ad 79, the occurrence of glass recycling is also confirmed by archaeometric analyses (Brill, Reference Brill and Scatozza Höricht2012), although an exhaustive study is still missing.

A network of collectors selected out of the waste stream anything that could be reused, and this activity was integrated into the productive system. Indeed, the less glass and metal is attested in dumps, the more the recycling system was effective, and the production chain wasted fewer reusable resources. Comparing this effectiveness in different sites may be more difficult: was the management of recyclable materials more efficient in Aquileia than in Baelo Claudia, or was Baelo Claudia, on average, richer in glass and metal items? Did this depend on different access to primary resources? A more systematic comparative study of primary deposits and dumping sites may provide answers to such questions.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the impact of recycling on the economy of Roman towns was substantial: metal and glass reached dumping sites in minimal proportions, strongly suggesting that these materials were extensively recycled. The occurrence of multiple episodes of remelting makes the figures that have emerged from our analysis a minimum threshold, i.e. that the effectiveness of recycling was even greater. Our results further suggest that the traditional assumption that recycling is combined with economic decline should be put aside; future research ought to start from the assumption that an effective use of resources and the reduction of waste were intrinsic to the economy of Roman towns in any period (see Downs & Medina, Reference Downs and Medina2000: 34; Holleran, Reference Holleran2012: 220).

We also found that a typical urban assemblage contained much more glass and metal than one would expect from examining rubbish dumps or secondary layers. To put it another way, our reasoning about urban dynamics is heavily influenced by ancient recycling, and the importance of ceramics is more archaeological than systemic (sensu Schiffer, Reference Schiffer1972).

Our study was mainly limited by the scarcity of well-published quantitative data from suitable deposits: in future, the availability of more datasets (e.g. the weight of different classes of artefacts) may throw more light on the effectiveness of recycling. For instance, understanding regional and chronological variations would permit a better appreciation of the economic role of recycling in relation to the availability of raw materials. In our analysis, we identified a general trend, but even that makes it clear that ‘waste nothing’ was commonplace in Roman towns.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation under grant DNRF119 – Centre of Excellence for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet). The project MACH – Pompeii was funded through the Progetto Strategico dell'Università di Padova (Bando 2011, prot. STPD11B3LB). The authors wish to thank R. Raja, C. Boschetti, R. Garth Jones, and J. Bonetto for helpful and stimulating discussions on the topic. They are also grateful to Maria Coto-Sarmiento for her help, Alba Antía Rodríguez Nóvoa for kindly supplying unpublished data and discussing the evidence from Armea, Spain, and the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their constructive comments. GF designed the research; CA studied the unpublished assemblage from the Sarno Baths; GF drafted sections 1, 2, and 4. GF and CA drafted sections 3 and 5. The tables were compiled by GF and edited by CA; CA designed figures 3 and 4; GF designed figures 1, 5, and 6; both authors collaborated on the revision of the manuscript.