Introduction

In John Preston's (Reference Preston2007) novelisation of the 1939 excavation of Sutton Hoo, O.G.S. Crawford is an absent presence, due to arrive at any minute but never actually materialising. Crawford's role is minimised not only in fictional accounts of the excavation, but also in factual records; in 1975, Bruce-Mitford wrote that Crawford spent “three working days at the site” and took a total of 64 photographs (Reference Bruce-Mitford1975: 137). In reality, Crawford was present for five working days, arriving on the evening of the 24th and leaving on the afternoon of the 29th of July, and his negative register shows that he took 124 photographs during this time. In 2011, following the discovery of a cache of photographs taken by Mercie Lack and Barbara Wagstaff, newspapers reported that “prior to these photos emerging there were just 29 known pictures of the excavation” (The Telegraph 2011). Furthermore, although three of Crawford's photographs feature in a current display of the Sutton Hoo finds in room 41 at the British Museum, Crawford himself is not credited as the photographer.

Crawford's absence in the above scenarios can be understood through the lens of a much wider discussion about the politics of representation in archaeological fieldwork. Several commentators have highlighted the deliberate erasure of archaeologists in excavation records (McFadyen Reference McFadyen1997; McFadyen et al. Reference McFadyen1997; Lucas Reference Lucas2001; Shepherd Reference Shepherd2003; Baird Reference Baird2017; Riggs Reference Riggs2017). Specific forms of archaeological labour are subject to different kinds of erasure; photography, for example, is only rarely captured by another camera (Riggs Reference Riggs2017: 362). This is often coupled with the assumption, espoused by Ingold (Reference Ingold2011) and Bohrer (Reference Bohrer2011), that to work with a camera is to somehow put aside one's subjective experience and function outside of the social circumstances of fieldwork. This treatment of archaeological photography disembodies and erases archaeologists such as Crawford, dislocating them both from their work and the social aspects of excavation. In this paper I highlight some of the many ways in which Crawford's photographs may be argued to reveal presence rather than absence, and social engagement rather than scientific detachment. In doing so I draw upon a collection of 124 prints made and annotated by Crawford, and currently housed in the Oxford Institute of Archaeology.

Photographing the finds

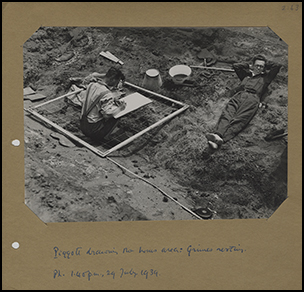

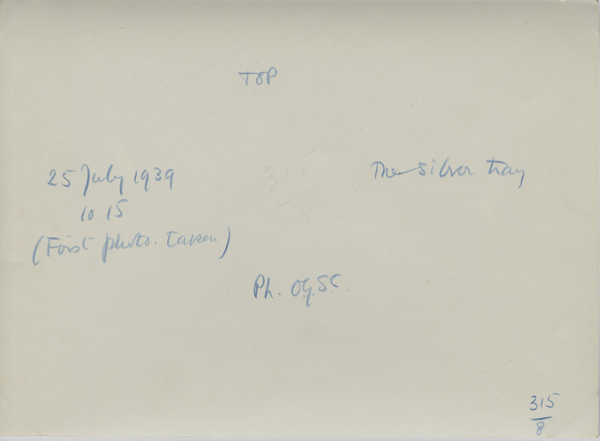

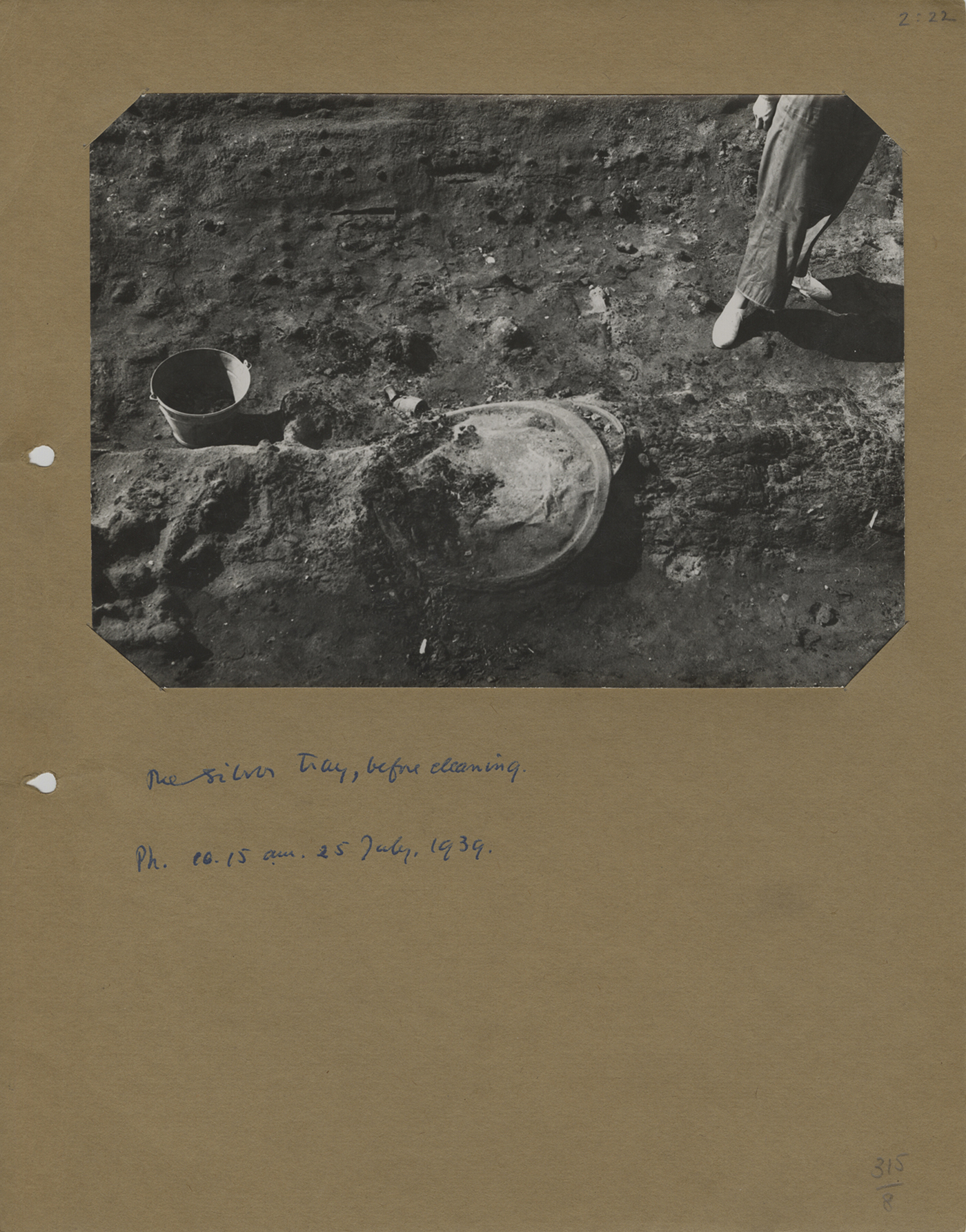

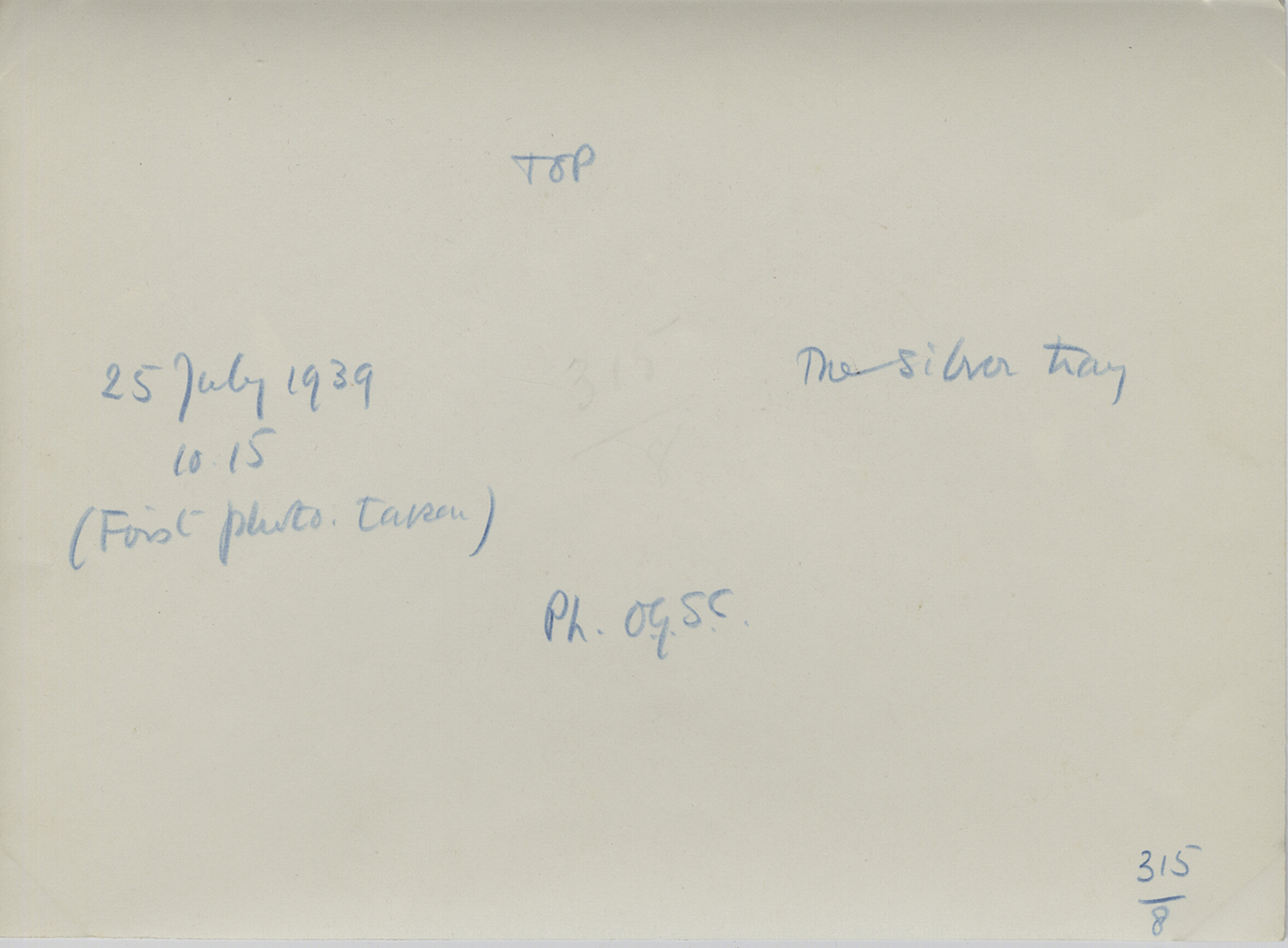

When reviewing Crawford's accounts of the excavation, it is notable that one object in particular seems to dominate his recollections: a silver dish measuring about three feet in diameter. Crawford described the lifting of the dish as “one of the great moments none of us who were present will ever forget” (Reference Crawford1940: 2). It is perhaps not surprising that the Anastasius Dish is the centrepiece of the first photograph taken by Crawford at Sutton Hoo (Figure 1). The copy of the print held by the Institute of Archaeology is mounted on brown card, on which Crawford has written “The silver tray, before cleaning. Ph.10:15 am. 25 July 1939”. This note was most probably made in the 1950s, when Crawford began to consolidate his photographs in preparation for their donation to the Ashmolean Museum. Yet, on the reverse of the print, another note hidden by the cardboard mount reads “First photo taken” (Figure 2). The tension between these inscriptions, the outward facing recital of factual data for a scholarly audience, and the hidden note tying the photograph to subjective experience resonates throughout the wider sequence of Crawford's photographs of Sutton Hoo.

Figure 1. The Anastasius Dish and disembodied foot of Peggy Piggott (print 2.22).

Figure 2. Note on the reverse of print 2.22.

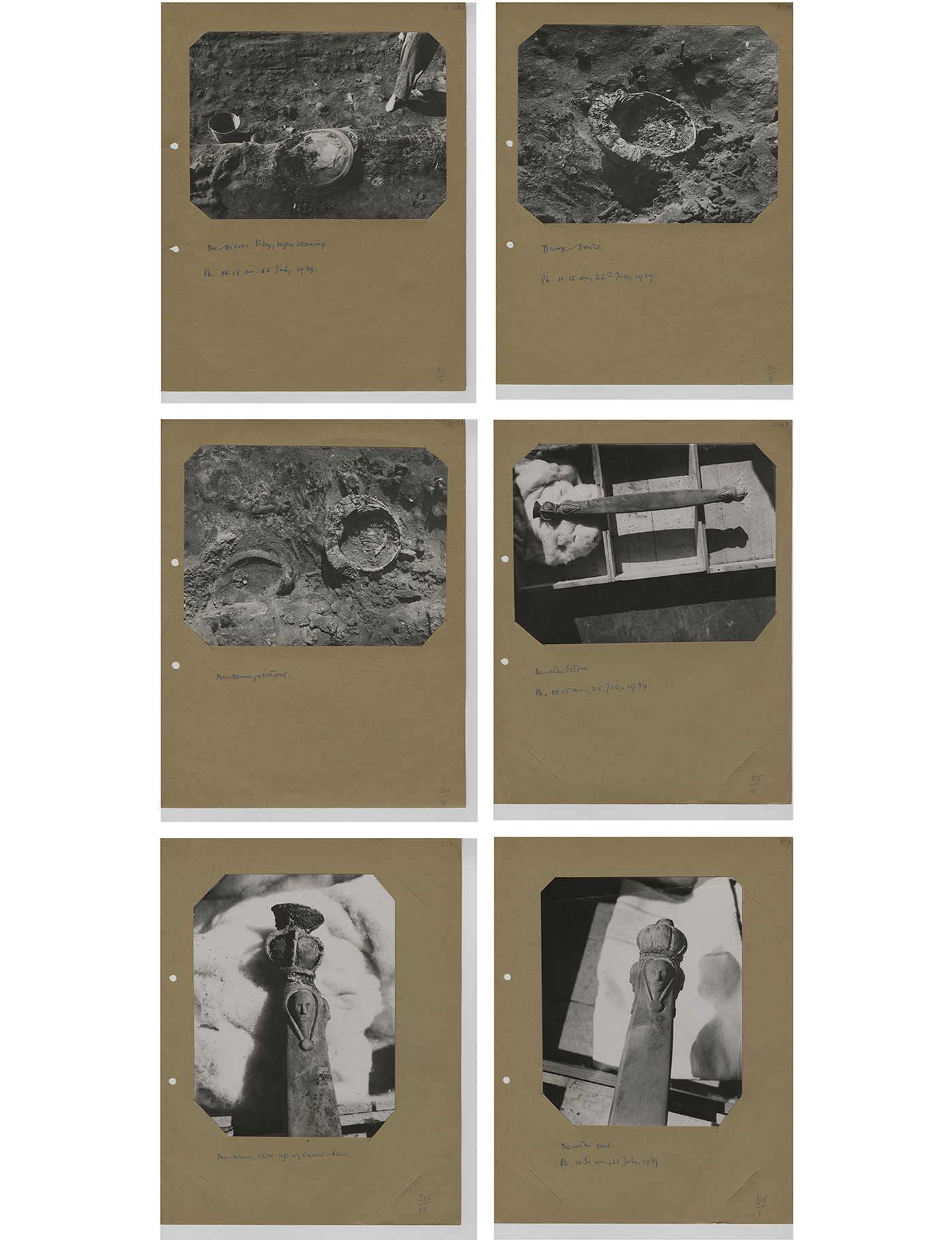

Traces of Crawford's experience can be found not only in individual prints, but by examining the temporal and spatial relationships between sequences of photographs. Immediately after photographing the Anastasius Dish, Crawford raced from the north side of the trench to the south-west corner to photograph what was exposed of the Bronze Bowls, before careering off to take three photographs of the whetstone, already safely nested in a packing crate (Figure 3). This frantic dash between finds took just under fifteen minutes, an average of two minutes per photograph. The sprint between objects tells a very human story of unbridled excitement. That Crawford incorporated photography into this race between the finds, rather than first touring the site and then returning to photograph at a more leisurely pace, is suggestive of how deeply ingrained photography was in Crawford's response to the excavation.

Figure 3. The first six photographs taken by Crawford (prints 2.22, 2.98, 2.97, 2.127, 2.1 & 2.2).

Social traces

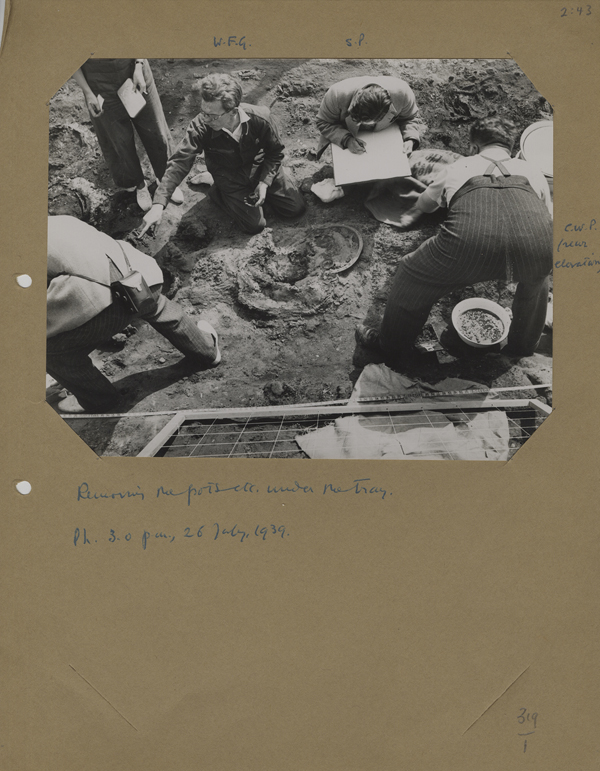

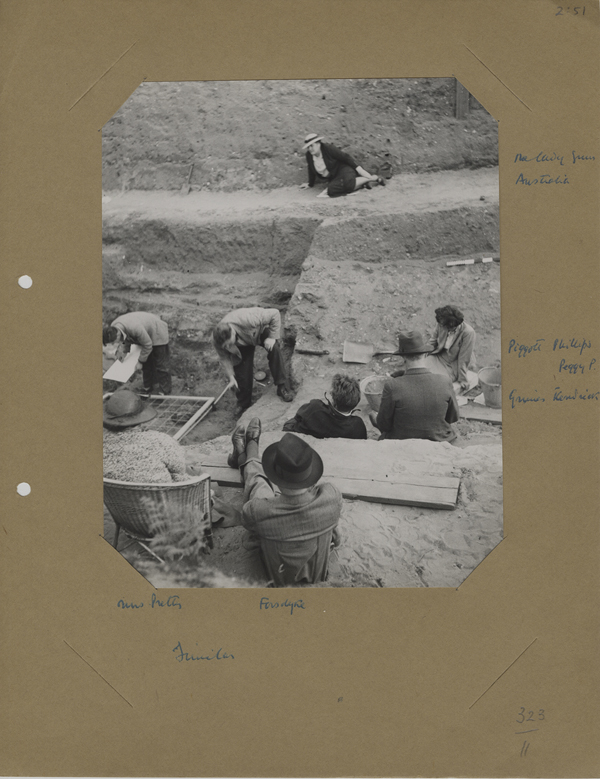

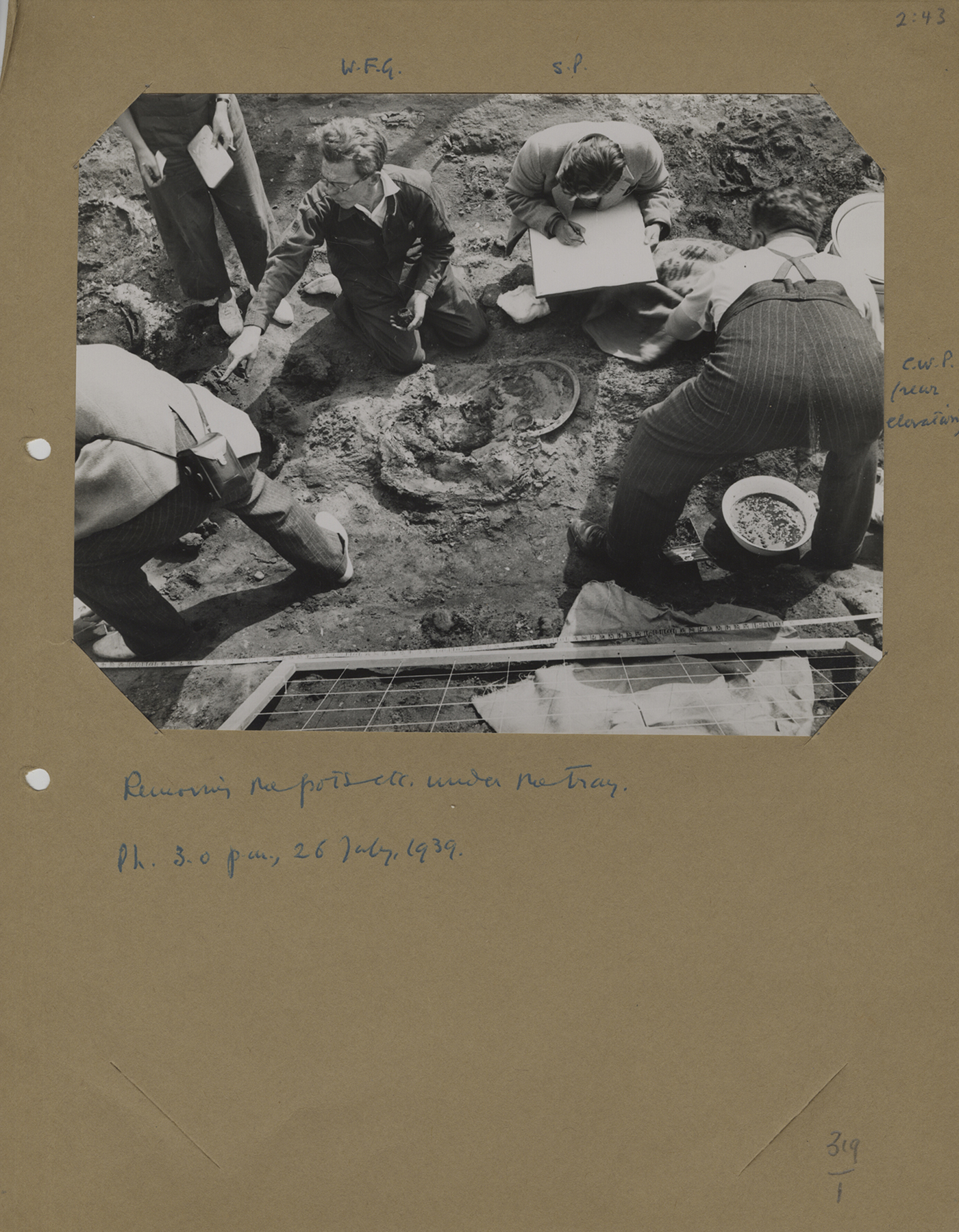

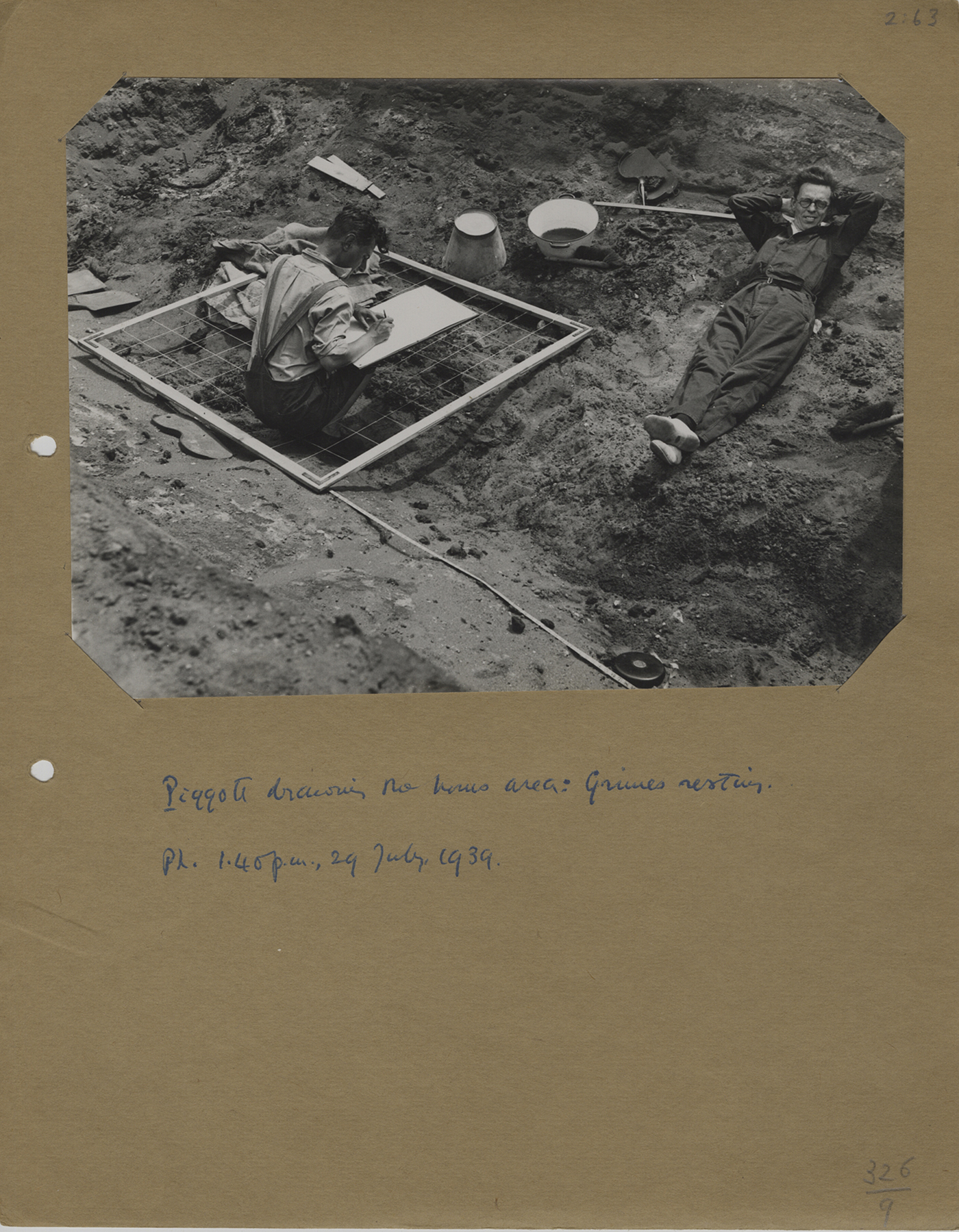

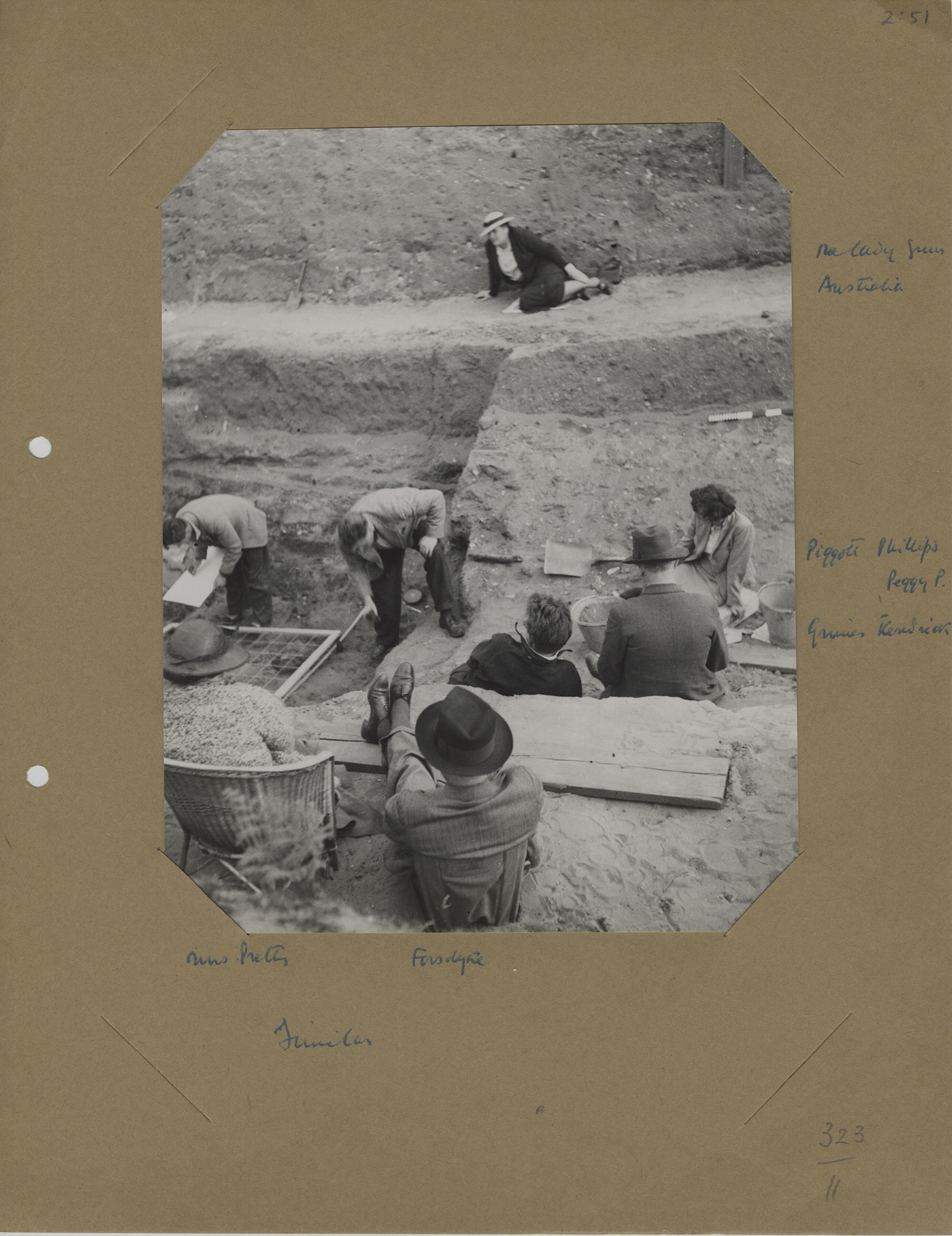

It is not only in photographs of the finds that Crawford's presence behind the camera can be detected. Crawford regularly flouted developing conventions for archaeological photography, which prescribed that human figures should only appear in front of the camera as a means of gauging scale (Cookson Reference Cookson1954: 44; Wheeler Reference Wheeler1954: 202). Of Crawford's 124 photographs of Sutton Hoo, 43 depict archaeologists and other onlookers. These are a series of striking portraits of the excavators with whom Crawford had close personal ties. Indeed, aside from the Anastasius Dish, Crawford's colleague from the Ordnance Survey, W.F. Grimes, is the most frequent subject of Crawford's photographs of the site. Crawford's close associations with his subjects are most apparent on occasions where his annotations of the prints take a humorous turn; as in the case of print 2.43 where Crawford draws attention to Charles Phillips's “rear elevation” (Figure 4). Nor does Crawford depict archaeological labour alone. In print 2.63 Grimes lounges on the floor while Stuart Piggott draws (Figure 5). In 2.51 the proportion of seated figures to those standing makes it clear that Crawford's focus is on the activity taking place outside the burial chamber (Figure 6). Both the wide sandy platform, occupied by Peggy Piggott, Grimes and T.D. Kendrick, and the walkways along the edge of the main trench were liminal spaces simultaneously providing access points into the chamber, and a social space where those present could gather when not working.

Figure 4. Rear elevation (print 2.43).

Figure 5. Grimes relaxing (print 2.63).

Figure 6. Social space at Sutton Hoo. This is also a photograph worthy of comment for the higher than normal ratio of women to men. Peggy Piggott is on the far right. Edith Pretty sits in the wicker chair in the foreground, while the ‘lady from Australia’ reclines on the far side of the trench (print 2.51).

Conclusions

These photographs of archaeologists at both labour and leisure are far removed from the scientific detachment described by Bohrer and Ingold. Rather these prints speak of much messier realities of life and provide a vital, engaging vision of archaeology in the field. Whether photographing objects or people, Crawford's photographs are gleeful, and at times irreverent. The camera is put to light-hearted, even downright humorous use, as much as it is utilised for more studious purposes. Although Crawford may not appear in front of the camera, it is vital to remember that he was both present and participating in the social interactions on the site, and that his enmeshment in the social landscape of Sutton Hoo had clear implications for the way in which he recorded the excavation. If the presence of Crawford as a photographer cannot be found in his photographs, this is more a reflection of strategies of looking at photographs, the questions asked of them and the work that they are expected to perform within institutional contexts than any inherent absence in the photographs themselves. By returning to the archive, with an awareness of what Morton (Reference Morton2009) has termed a “whole archive” approach, it is possible to excavate Crawford's presence at the site.

Acknowledgements

All photographs are from the Crawford Photographic Archive and appear courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Oxford. I would like to thank Martyn Barber, Jaanika Vider, Lesley McFadyen and Jennifer Baird for their comments on drafts of this article. This project was funded by the AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Partnership.