12.1 Introduction

This chapter considers how different types of development-focused organizations have introduced case studies into their operations, and explores the lessons from these experiences for other development organizations interested in using case studies to enhance their own implementation effectiveness.Footnote 1 At one level, of course, case studies will be used differently depending on the organizational context; as such, to fully exploit a case study’s potential it must align with an organization’s specific reality: its history, mission, mandate, and capability. Actually doing this, however, requires undertaking the complex task of integrating cases into idiosyncratic organizational structures, rules, regulations and processes, and aligning it with a corporate culture that, at least initially, may or may not be favorably disposed to ‘learning’ in this way. In the sections that follow, we provide a comparative analysis of how this task has been conducted in four different development organizations, focusing in particular on how they select, prepare, and utilize case studies for collective learning.

A concern from the outset, and one that some regard as a pervasive weakness of case studies, is how to prepare cases that are both faithful to the unique particularities of each intervention and yet potentially usable by practitioners working elsewhere, perhaps even in different sectors, regions, and scales of operation. Indeed, “But how generalizable is that?” is a common critique levelled against case studies as a research method, where the concern is that the case itself is neither randomly selected nor “representative” of a larger population, but rather “cherry picked” to support predetermined conclusions. As methodological and empirical issues, these concerns are addressed elsewhere in this volume.Footnote 2 For present purposes, we consider case studies not as “qualitative evaluations” nor as small-scale “impact assessments” of projects, but focus instead on their roles as diagnostic and pedagogical instruments within (and between) development agencies. In this sense, we consider how case studies are prepared and read in ways akin to their use in medicine, law, and public policy – which is to say, as instances of broader phenomena, wherein professionals use their seasoned experience (and, where appropriate, scientific knowledge) to learn from specific instance of how, why, where, and for whom particular outcomes emerged over the course of a project’s or policy’s implementation. If formal impact evaluations are concerned with assessing the “effects of causes” (e.g., Did this rice subsidy, on average, benefit the poor? Did that text message invoking sacred precepts increase credit card repayments?), then in this instance case studies primarily seek to discern the “causes of effects” (How was this village able to solve its water disputes so much more effectively than others? Why did that program for improving child nutrition fare so much better with younger mothers than older ones? Where were the weakest and strongest links in the implementation chain of this immunization program? Why do some development organizations seemingly learn more effectively than others?).Footnote 3 It is in responding to these latter concerns that case studies have a distinctive comparative advantage; in this sense they should be seen as a key complement to, not a substitute for, more familiar evaluation tools used to engage with and learn from development interventions.

In this spirit, our concern here is to work backwards from broader concerns about the conditions under which development organizations ‘learn’ (or seek to learn), with a view to considering the role that case studies play in this process. Our discussion proceeds as follows. Section 12.2 considers four broad factors that seem especially important for understanding how organizations (not just their individual staff members) learn – that is, modify and/or improve their procedures and products in the light of experience and evidence. Section 12.3 then considers how these four factors have been deployed in case studies as used by four different organizations engaged with development issues: the World Bank, Germany’s GIZ (Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit), the Brookings Institution, and China’s Ministry of Finance. Section 12.4 concludes by categorizing how these different organizations are using case studies to learn across four organizational levels.

12.2 Organizational Learning Within Development Organizations

How do development organizations learn? A reading of the literature suggests that four broad factors seem to be especially important for understanding whether and how such learning takes place: motivation, environment, knowledge type, and practical use. We explore each of these factors by responding to four related questions.

12.2.1 Do Development Agencies Have the Motivation to Learn?

What motivates organizations to learn and invest in learning, and why might case studies be a suitable tool for doing so? For private sector organizations operating in today’s globalized economy, the motivation is clear: they must ‘adapt or die’ – that is, they must continually change in response to their fast-moving environments or risk becoming irrelevant. Indeed, in business theory and practice, an organization’s capacity to learn, and to apply and communicate knowledge, is considered a key strategic capability and is thus fundamental to its ability to produce value through innovation, improved quality, and efficiency (Reference DruckerDrucker 1994). Management specialist Peter Reference SengeSenge (1990) goes so far as to argue that the rate at which organizations learn may become the only sustainable source of competitive advantage; to capture this, he introduced the idea of a ‘learning organization’ – namely, an organization which actively cultivates certain characteristics to harness value from continuous learning.

For the most part, however, development organizations tend to be mission- or impact-driven rather than profit-driven. As such, they operate in a somewhat different environment and are influenced by different forces. These organizations may not ‘die’ if they do not adapt – the fate of large development agencies whose mandates derive from nation-states, for example, is ultimately determined by political criteria. As such, and because their very existence serves the purposes of different powerful groups, public and nonprofit development agencies are unlikely to decline, at least in the short term, no matter what their level of “performance” is deemed to be. However, if a key driver of learning in organizations is typically to improve performance (Reference Fiol and LylesFiol and Lyles 1985), this can be a source of motivation common to all development organizations – mission-driven as well as profit-driven. So understood, for development agencies performance can be broadly defined by its key functions (e.g., client services, advocacy, distribution of funding, direct service delivery).

Factors both external and internal to the organization can help generate a strong need for learning which acts as an important motivator for action within an organization. Such a need generates the motivation to go from contentment (passive) to curiosity (actively seeking knowledge). A perceived need is therefore the antecedent to new learning (Reference ScottScott 2011). For development organizations in the current environment, there are many factors that may generate a learning ‘need’. External forces, including large global political agendas such as meeting the Sustainable Development Goals, may motivate a learning need as the organization considers how to respond; similarly, the emergence of influential new rival agencies, such as the New Development Bank, may create pressures where previously there were none. Internal factors may also generate a need: the desire to improve communication; to share lessons, build relationships and communicate; or to build a culture that is open to discussing challenges.

12.2.2 Is the Organization’s Environment Conducive to Learning?

Any learning initiative will take place in the wider context of the organization’s approach to learning and knowledge management. The capacity and openness to learn must be designed into the organization and, in turn, be reflected across its structures, functions, and processes. To do this, an organization, and especially its key managers, must first be open to “unlearning” established ways (Reference Hedberg, Nystrom and StarbuckHedberg 1981); indeed, Reference Inkpen and CrossanInkpen and Crossan (1995: 596) argue that “a rigid set of managerial beliefs associated with an unwillingness to cast off or unlearn past practices can severely limit the effectiveness of organization learning” (see also Reference Nonaka and KonnoNonaka and Konna 1998). More positively, Reference ZackZack (1999: 135) defines a firm’s knowledge strategy “as the overall approach an organization intends to take to align its knowledge resources and capabilities to the intellectual requirements of its strategy.” While knowledge may transfer in the normal course of activities, organizations often introduce processes and knowledge management systems that actively facilitate the key processes of knowledge creation, transfer, and retention (Reference Argote, Beckman and EppleArgote, Beckman, and Epple 1990). Reference ScheinSchein (1990) suggested that a group’s learning over time becomes encapsulated as the group’s culture: in other words, it is both internalized as a set of assumptions and externalized as group norms or values.

The use of case studies should therefore be considered in the context of the organization’s learning intent, strategy, and culture, and as one of a number of possible organizational learning tools or methods. The production of a case study involves not just a product but also a process which in itself can provoke learning at multiple levels of the organization. Key characteristics of such a process include:

Individual learning: Individuals have generated knowledge through their practices and they have learned how to overcome challenges. Organizations are motivated to capture the tacit knowledge held within individuals in the system and to share this knowledge. Case studies are one tool which can be used to approach this task.

Group learning: Group engagement with producing a case study. Case studies can be used to engage individuals within a group in reflecting together, capturing the group’s knowledge and generating shared insights.

Organizational learning: Retention of knowledge within the organization. The case study process is a way of attempting to codify and share knowledge. Members of the organization can then access this knowledge through the case studies, which can be used to initiate and inform discussion. Learning at the organizational level typically requires support from the organization’s authorities.

Interorganizational learning: Case studies are shared between organizations to foster the collective learning of a wider community of practice. Knowledge is transferred through a learning network by the development of shared processes/systems. Creating a network expands the reach of any particular initiative.

We will categorize this multilevel learning as IGOIL (individual, group, organizational and interorganizational learning), where different institutions may operate actively on one or more levels relevant to their learning strategy.

12.2.3 What Types of Knowledge are Captured by Case Studies?

Drawing on the early work of Reference PolanyiPolanyi (1966), Reference NonakaNonaka (1994) distinguishes between two types of knowledge: explicit knowledge, which is easily identified and codified; and tacit knowledge, which is what we know but cannot easily describe, and relates to both cognitive capability (‘know what’) and action (‘know how’). Explicit knowledge can be shared and integrated via reports, databases, and lectures, whereas sharing tacit knowledge occurs through dialogue and practice. One can acquire and convey explicit knowledge about a bicycle (its wheels, frame, etc.) through study, but one only acquires the tacit knowledge required to ride the bicycle by persistent practice (i.e., by falling over many times until one’s brain figures out how to stay upright).

There is a lot of technical knowledge within development organizations, and a corresponding familiarity with discussing and recording what was done in a given situation in an attempt to discern and capture ‘best practice’. The case studies discussed in this chapter intend instead to capture knowledge about the way that things are done: ‘the how’ of implementation rather than ‘the what’ of end results. This type of knowledge is often held within an individual (or team) who has implemented or supported implementation of a program. From the social constructionist perspective on learning, Reference Cook and BrownCook and Brown (1999) suggest that this type of knowledge is acquired “as people wrestle with the intricacies of real world challenges and improvise a way to a solution” (Brown 2011: 6). From this perspective, learning depends on social interaction and collaboration: one person’s knowledge is co-dependent on the contributions of peers and must be negotiated with them. Knowledge about ‘the how’ is often tacit, context specific, and complex; factors relating to behavior, politics, and institutions influence the process. This is difficult to capture as the more we try to codify tacit knowledge the more it loses its context; perhaps it can only be recorded to a degree. Case studies attempt to capture some of this type of knowledge through alternative devices (such as via narrative form and personalization).

The cases discussed in this chapter are written with a specific focus on ‘delivery challenges’ (see Box 12.1); they describe situations where groups wrestle with and sometimes overcome delivery challenges. By sharing this type of knowledge, it is thought that others in the organization may gain inspiration for wrestling with their own real-world challenges. The organization’s culture will influence the openness of its members to capturing and discussing this type of knowledge – that is, knowledge relating to challenges and failures rather than just success stories.

Box 12.1 Defining ‘Delivery Challenges’

Delivery challenges are the nontechnical problems that hinder development interventions and that prevent practitioners from translating technical solutions into results on the ground. They are intimately related to development challenges, how interventions are implemented, and organizational issues. Delivery challenges should be the answer to the following questions: Why did intervention X, aimed at solving the development challenge Y, not work or not achieve its full potential? What were the main obstacles that intervention X faced during its implementation?

12.2.4 How Do Development Organizations Enhance the Practical Use of Case Studies?

It is widely accepted that learning requires changes in both cognition (knowing) and behavior (doing) (Reference ArgyrisArgyris 1977; Reference Crossan, Lane and WhiteCrossan, Lane, and White 1999; Reference GarvinGarvin 1993; Reference Hedberg, Nystrom and StarbuckHedberg 1981; Reference Stata, Almond, Schneier, Russell, Beatty and BairdStata and Almond 1989). As such, the practical value of using case studies lies not just in documenting the end product (what was achieved) but also the processes involved in getting there (how the end product was achieved). An advantage of the type of case study described in this chapter is that it remains close to practice. The cases capture stories of practice and should assist practitioners in implementing their work, thereby helping the organization achieve its mission.

Case studies can provide direct learning opportunities for practitioners to gain understanding of specific types of implementation challenges and how they were tackled, and/or to increase knowledge about specific development contexts. They aim to provide knowledge in a context-sensitive manner (unlike ‘best practices’). Since this type of knowledge is often best shared in person, additional value can be gained from the case study by using it as a catalyst to spark dialogue around implementation issues between practitioners within and between both sectors and organizations. As the focus is on challenges encountered during implementation, use of this type of case study may also contribute to wider discussions in an organization about challenges, including failures, and how to learn from them. Dissemination and promotion of engagement with case studies are therefore important activities that should take into consideration the specific audience, organizational context, and culture. Knowledge management systems which incorporate the compiling and coding of cases are a useful resource; however, it may not be sufficient to just share a case study with colleagues. Instead, learning platforms and opportunities should be designed with the intended audience in mind; for example, structured discussions and learning events may be appropriate mechanisms to translate knowledge into practice.

12.3 Using Case Studies for Organizational Learning in Four Development Agencies

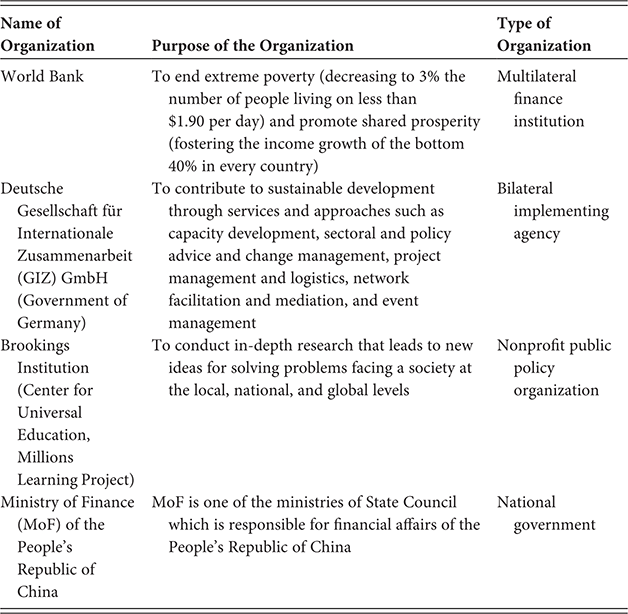

Organizations have different ways of curating, documenting, and mobilizing knowledge. Generating and using case studies as a tool for organizational learning requires a considerable investment of an organization’s time and resources, and different organizations have deployed different approaches. This section presents the experiences of four different organizations engaged with development issues – a multilateral agency (the World Bank), a major bilateral agency (Germany’s GIZ), a leading think tank (Brookings Institution), and a key national ministry of a large developing country (China’s Ministry of Finance) – as they have developed their use of case studies within their individual contexts. Reflecting on the experience of these different types of organizations may assist other organizations in their decisions about whether and how best to incorporate case studies.

The organizations were selected on the basis of their participation in the Global Delivery Initiative (more on this below) as well as the type of organization they represent. They were assessed via oral interviews as well as complementary desktop research of secondary material. Based on this assessment, the chapter will now examine how the motivation for organizational learning, managing knowledge, and the use of case studies in managing knowledge can vary among different types of development organizations.

All of the four organizations are linked through their involvement in the Global Delivery Initiative (GDI; described below – see Box 12.2) and all have developed case studies and shared them through the GDI network, which allows for some comparison between methods and approaches used.

Box 12.2 Case studies and the Global Delivery Initiative

The Global Delivery Initiative (GDI) was a joint effort by multiple organizations to create a collective and cumulative evidence base on the ways in which challenges encountered during the delivery of development interventions are addressed. The GDI supported the science of deliveryFootnote 4 by building on the experience of its partners; connecting perspectives, people, and organizations across sectors and regions; and ensuring that staff and clients have the knowledge they need for effective implementation (see Reference Gonzalez and WoolcockGonzalez and Woolcock 2015). From the outset, the GDI deployed analytical case studies as its primary tool for acquiring, assessing, and disseminating knowledge on implementation dynamics: how particular teams, often implementing complex projects in difficult circumstances, successfully identify, prioritize, and resolve the problems that inherently accompany delivery.

In addition to producing case studies (and sharing them through its Global Delivery Library), the GDI convened partners to facilitate sharing of experiences and lessons learned on delivery; provided support to practitioners in member organizations as needed; trained prospective case writers; and identified common delivery challenges to provide support to practitioners. The goal was not to identify prescriptive universal ‘best practice’ solutions, but rather to share particular instances of how common problems were solved, with the expectation that these solutions could be adapted elsewhere as necessary by those who face similar challenges. Knowing that others have faced and overcome similar challenges can also be an important source of ideas and inspiration. Indeed, all professional communities – from brain surgeons to firefighters – have forums of one kind or another for sharing their experiences and soliciting the advice of colleagues as new challenges emerge; similarly, managers and front-line implementers of development projects should have ready access to people and materials that can help enhance their skills and effectiveness.

The steps by which a GDI case study was prepared emerged through an iterative process. The common principles underpinning the preparation of a GDI case study centered on treating it as an instance of applied research: beginning with a thorough desk review (documenting the project’s history, objectives, and performance to date); using this to generate specific questions pertaining to implementation challenges that formal documents cannot answer; and then outlining a pragmatic methodology whereby particular stakeholders (project staff, recipients, senior government counterparts, etc.) were interviewed and additional data generated. The case study was then prepared on the basis of this material (Global Delivery Initiative 2015). Unique to the GDI case study methodology was that it evolved around development and delivery challenges. Instead of focusing on (project and/or program) objectives, case studies were built around challenges that were cross-sectoral and allowed for learning across sectoral disciplines. The assumption was that this approach would spark a discussion on nontechnical matters amongst technical experts as well as related stakeholders (e.g., governments). This approach varied considerably from general practice in development organizations, wherein learning was focused on project reports, excluding knowledge on the “how to.”

12.3.1 Motivation for Using Case Studies for Organizational Learning

The motivation for using case studies varies widely across all assessed organizations, depending on organizational objectives, structures, and processes. For example, instead of focusing on ‘best practices’, China’s Ministry of Finance (MoF) seeks to tell the story of China’s development over the past decades in ways that capture insights to inform and possibly adapt planned or ongoing interventions in other countries (as well as in China) – the MoF invests in case studies because they are perceived as a suitable product for knowledge-sharing between China and the rest of the world. A case study is considered an additional product in documenting project results and hence will be disclosed and distributed publicly. More formally, the MoF’s objective(s) when producing case studies are to:

Shed light on underexplored projects that China has conducted together with the World Bank, producing implementation knowledge on how these projects were carried out.

Identify a platform and adequate tools to document its development experiences in order to share these with the world, especially with other developing countries as part of a “South–South Cooperation” agenda.

Table 12.1 Overview of the four development organizations

| Name of Organization | Purpose of the Organization | Type of Organization |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank | To end extreme poverty (decreasing to 3% the number of people living on less than $1.90 per day) and promote shared prosperity (fostering the income growth of the bottom 40% in every country) | Multilateral finance institution |

| Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (Government of Germany) | To contribute to sustainable development through services and approaches such as capacity development, sectoral and policy advice and change management, project management and logistics, network facilitation and mediation, and event management | Bilateral implementing agency |

| Brookings Institution (Center for Universal Education, Millions Learning Project) | To conduct in-depth research that leads to new ideas for solving problems facing a society at the local, national, and global levels | Nonprofit public policy organization |

| Ministry of Finance (MoF) of the People’s Republic of China | MoF is one of the ministries of State Council which is responsible for financial affairs of the People’s Republic of China | National government |

The Millions Learning Program at the Center for Universal Education (Brookings Institution) decided that case studies were an appropriate strategy for capturing and sharing the process behind how education interventions around the world went to scale. In order to do so, the Millions Learning team globally scanned for programs and policies initiated by state and nonstate actors that demonstrated a measurable improvement in learning among a significant number of children or youth.

GIZ’s interest in case studies is to primarily address specific delivery challenges by first characterizing the most important failure in not closing the delivery gap, specifically the so-called “last mile delivery gap” for the poor. For example, in the case of water and sanitation programs, it is the missing access to clean water; in the case of the energy program, it is missing access to at least one important energy service. Case studies address more complex issues at the governance level, such as the functioning of public administration systems overseeing police forces. They also deal with more institutional/political types of failure, such as the missing rights-based approach to public administration (South Caucasus) or political interventions in police reforms (Central America). Success is therefore always presented as a substantive response to an identified failure in public service delivery.

GIZ’s motivation in curating knowledge via case studies has varied depending on the case study in question. Some examples follow:

Starting a more general reflection process on specific program approaches (Water/Sanitation; Community Policing)

Promoting an innovative intervention with proven scale-up (Prison Reform/Bangladesh)

Presenting a proven technical/organizational innovation (Metering System Bangladesh)

Supporting regional learning processes (Community Policing, Administration Law South Caucasus)

Marketing program approaches (Cashew Initiative; Energizing Development).

12.3.2 Organizational Learning Environment

Work on case studies is usually embedded in organizational contexts such as units explicitly dealing with organizational learning and/or knowledge management. These linkages are of high importance to ensure that case studies reach their intended target audiences within each organization. Organizational culture – or in this case, learning culture – is the “breeding ground” that highly impacts how case studies are perceived and acknowledged.

For China’s MoF, promoting adaptive learning is the core rationale for producing case studies; as such, case studies should at best include stories of successful interventions as well as course correction. However, changing the perspective from focusing on success to challenges has not always been easy for case writers in this context. To openly identify, assess, document, and communicate failure poses a distinct challenge in China’s otherwise “success-driven” environment.

Brookings’ Millions Learning project was initially interested in learning from case study “success stories” as well as from interventions that did not achieve their intended outcomes. However, the team quickly realized how challenging it was to publish “failure cases,” as people are often hesitant to publicly admit to failure. That is why in the project’s calls for case studies, the wording is highly important. For example, the team’s use of the term “failure” caused resistance, whereas the terms “challenges” and/or “course corrections” resulted in greater sharing among case study partners. Apart from semantics, the change in wording also strongly enhances the emphasis on learning and jointly improving from experiences (such as how challenges have been overcome).

To openly discuss challenges as well as failure is nothing new at GIZ, which for many years has been actively fostering a culture permitting failure to be openly addressed. Strategic evaluations, for example, are done with openness, highlighting deficits and failure. However, discussing failure and limitations is not yet a mainstreamed management attitude. GIZ acknowledged several common challenges to the process of writing case studies, as follows:

Identifying an appropriate delivery challenge

Updating the existing literature by internet research, and not just relying on existing institutional documents or reports

Identifying the most important causal mechanisms

Lack of recognition of the importance of governance structures/aspects at the national level

Comparative case studies require a different methodological approach. They are not an extension of a single case study

The process of organizing a case study depends on the specific demand and should not be too predetermined. (It is not the written document which counts, but the use of the knowledge that emerges by doing case studies.)

Unlike China’s MoF or the Millions Learning project at Brookings, the scope of GIZ’s case studies depends on the demand of its partner organizations and program managers. Consequently, GIZ’s approach to learning from case studies and its integration into corporate learning has several specific objectives:

To document the tacit implementation knowledge of different program interventions with different partner organizations. As a contribution to an internal reflection process, this type of case study needs a clear mandate from an internal network or community of practice and relies on the motivation of senior advisors to make their implicit knowledge explicit.

To introduce innovative approaches focused on a specific delivery gap at the country level, but also at regional or international levels. This type of case study is neither a policy document with general recommendations nor a detailed story of a specific program intervention at the country level. The case attempts to understand the most important causal mechanism responsible for the identified delivery challenge and to explain why and how the presented response to the delivery challenge has been effective.

To present a proven organizational or technical solution to an identified delivery gap mainly at the local or micro-level starts by explaining why the established approach has not been effective in closing the delivery gap. Such case studies usually focus on the incentive structure, in particular on incentives and behavioral attitudes of clients and partner organizations.

At the World Bank, the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) has embarked on a series of reports to better understand how the Bank learns from its operations, embedded knowledge, and experiences (see IEG 2014, 2015). As a general conclusion, these reports state that the World Bank can do much better in learning from the knowledge it produces and that flows through its practice.Footnote 5 The Bank agrees it needs a more strategic approach to learning, and that such strategy should adapt to the different learning needs identified by these reports (needs related to operational policies and procedures, human resources policies and practices, and promoting an institutional environment with incentives and accountability to foster knowledge and learning).

As part of a recent full-fledged institutional change management process, the World Bank has created different sectoral responsibilities to manage learning and knowledge to help overcome development challenges. The new arrangement aims to build capacity for staff and to encourage clients to learn, share, and use knowledge derived from experience in addressing operational challenges, including assessing whether and how such experiences can be adapted elsewhere and scaled. One of these institutional responsibilities resided in the Global Delivery Initiative, which sought to package such knowledge and lessons into case studies and generate methods to develop such case studies for use within and between development organizations. For GDI, case studies on delivery provided a clearer understanding of the sequence of events and balanced the perspectives of key actors, helping us untangle cause and effect. More specifically, such case studies sought to outline how interventions were implemented. They provided insights into the results and challenges of implementation, and helped to identify why a particular outcome occurred. They explored interventions in their contexts, and described what was done, why, how, for whom, and with what results.

12.3.3 Types of Knowledge Curated Via Case Studies

Case studies are an appropriate tool to capture knowledge in a structured yet context-sensitive manner, allowing for narratives to unfold and implementation processes to be revealed without over-simplifying. The type of knowledge curated via case studies, however, varies according to each organization assessed.

Guidelines produced by the World Bank were used as the methodological backbone of all case study work initiated by China’s MoF. However, the Ministry would like to maintain a certain flexibility regarding its case studies that allows experienced case writers to add their individual styles and additional details. This is because China’s MoF strives to capture knowledge through case studies that informs the design of new interventions (projects) in China, as well as to inform the implementation of ongoing interventions (scaling up). Therefore, the selection criteria for case studies are primarily based on the quality of the project the case study will focus on, and whether it entails concrete experiences that are worth sharing within and beyond China. In a small number of cases, the MoF also selects case studies based on research interest.

Apart from publishing a final report and upcoming stand-alone case studies, the Millions Learning team periodically blogs about its case studies, report findings, and topics. The team is planning to release a series of two-minute videos that feature voices of case study partners to bring each featured case study to life. The Millions Learning team also disseminates a quarterly newsletter, tweets daily, and presents its report and case study findings at international events and conferences every few months. The vast majority of the case studies (80 percent) contained empirical findings from fieldwork and were not limited to desk research only. Fieldwork was conducted by staff at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution and consultants via in-person or phone interviews. The same people who undertook the field visits and data collection wrote the case studies (in-house researchers as well as external consultants). What is required of case writers is familiarity with the case study methodology as well as the topic of the case, the specific intervention, and the country.

GIZ has broad experience in using case studies and uses an existing methodology. One of the main learnings is that case studies are only valid in specific contexts and that knowledge cannot be directly transferred from one context to another. For instance, once a case study is developed, its results are only used by a couple of colleagues to feed into the development of specific programs. At times meta-evaluations are carried out for specific topics, but these do not always lead to changes in action as the conclusions tend to be fairly general. This has led to the understanding in GIZ that case studies are a necessary tool for specific programs but that generalization of results is tricky and obtaining evidence is highly resource-intensive and often impractical. Use of case studies falls outside the default reporting procedures at GIZ. Reporting requirements are linked to specific program cycles and implementation processes, whereas case studies take a broader view of the social and political context as well as behavioral and institutional aspects. They usually cover a greater period than a program cycle, as they focus on how delivery gaps have been closed (and not only on the impact of a given program intervention).

At the World Bank, the current objective is to gain in-depth and systematic knowledge on the causal mechanisms that explain development results. Based on systematizing casual mechanisms (which includes the identification of the key factors and enabling conditions) that explain the pathway to change, the Bank can identify lessons learned that may usefully inform decision-making in other contexts and scales. The case study method is useful for hypothesis generation: drilling deep into experiences and tracing the casual mechanisms of change (see Reference GerringGerring 2017) helps to systematize the mechanisms behind implementation process.

GDI’s cases, then, worked with a focus on the ‘how to’ of implementation. The type of knowledge curated revolved around those factors and pathways of change that explain a particular development result. The purpose of gathering such knowledge was to provide practitioners with evidence that can help them inform their own decision-making. As stated in GDI’s fact sheets,

The case study method encourages researchers to ask questions about underexplored complex delivery problems and processes that development stakeholders routinely grapple with: what they are, when they arise, and how they might be addressed, including detailed accounts of delivery techniques, strategies, and experiences of the twists and turns of the implementation process. Systematically investigating delivery in its own right will make it possible to distill the common delivery challenges – the institutional, political, behavioral, logistical, and other issues that affect the delivery of specific interventions. It will also inform practitioners when they are faced with similar delivery challenges in their own programs and projects.

12.3.4 Use of Case Studies for Organizational Learning

Apart from disseminating case studies via the Global Delivery Library of GDI, China’s MoF intends to publish all its case studies via the library of the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, which is one of the partner universities of MoF China. Conferences and events organized by local government officials are equally important channels for dissemination of insights gained via case studies. For instance, the Ningbo government is planning to include the Wetland project case study in a book about Ningbo’s experience in implementing World Bank projects, and it will be shared with participants at a conference hosted by the Ningbo government. Additionally, all case studies by the MoF will be disseminated via the internal online platform to all bureaus and agencies affiliated with the Ministry. It is too soon to provide evidence on whether case studies have been used by decision-makers and officers in government. However, there has been strong interest by project managers in China to use and learn from these case studies. The MoF does not foresee any resistance or challenges in disseminating case studies. Even so, it has adapted its approach following feedback from a GDI training course so that now a selected group of dedicated academics will produce all case studies; this has significantly increased the quality of the cases.

The explicit objective of the Millions Learning project is to use case studies to provide a picture of the players, processes, and drivers behind the scaling process in education. It is evident that the project is interested in leveraging knowledge in education across organizational and national borders. The project also intends to learn from and build on research on scaling up which may be relevant across sectors – for example, health and nutrition, as well as other disciplines. It has been clear from the start that the project did not intend to publish a compendium of case studies, but instead preferred to focus on patterns across case studies that should be documented and shared. Case studies are referred to in order to provide examples. The team was also clear from the project’s inception that documentation of knowledge is more a means to an end than a final product. Therefore, the Millions Learning report is considered to be the starting point for knowledge-sharing, dialogue, and, ideally, action around selected topics and areas in education. Hence, it is outward facing, inviting organizations and individuals to share information and contribute to further shaping the debate around global education. To achieve this, the initiative continuously reaches out to organizations, agencies, and individuals from around the world to contribute to and feed into the process through interviews, conventions, and draft report reviews. The Millions Learning team also published stand-alone case studies in 2016, providing a deeper dive into the individual case studies discussed in the Millions Learning report.

To date, ten case studies using the GDI methodology have been developed by GIZ. There has been exchange across organizational boundaries, but not yet at scale. However, regional programs have used case studies for reflection processes across boundaries. Selected case studies have been presented at regional seminars and used as reference material in the formation of new interventions. Coming back to the different types of case studies GIZ has developed, the following lessons can be derived from experiences in writing and using case studies so far:

Case studies presenting innovative approaches focus first on design and analyze the real implementation issues related to the chosen design. The context is more related to regional or international experiences in the area or issues presented, and the country context is mainly taken into account for understanding the differences with other experiences. Comparison is more important than detailed understanding of specific case-related aspects of implementation and management. The main focus is on understanding similarities and differences due to specific country conditions.

Case studies which summarize implementation knowledge focus more on implementation than on design since the design has been proven effective under different conditions and situations. Thus, the main interest is to understand what works under which conditions and what kind of tacit knowledge should be taken into account when approaches have to be transferred and adapted to a “new” context.

Case studies which present a proven organizational/technical solution to a delivery gap at the local level focus on the “how” of the incentive structure. Therefore, feedback loops with clients and real-time impact monitoring are important tools.

At the World Bank, the GDI was one of the most interesting and productive initiatives using case studies as a learning source. The model of case studies for the GDI provided comprised a critical body of knowledge with insights from the implementation process that helped practitioners identify those causal mechanisms explaining results in particular contexts. An understanding of the critical factors and enabling conditions in achieving results helped to inform projects operating outside the specific context of the case. The cases were also used as part of training sessions to develop the capacity of practitioners to use cases to inform their own practice and to populate the GDI’s case study repository, now managed by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation.Footnote 6 At the same time, the training agenda acted as a capacity building “train the trainers” strategy, with the aim of creating a global cadre of suitably qualified practitioners that not only gained skills as case writers but also benefited their own practice. Internally at the World Bank, the GDI trialed some case studies that were used as learning exercises for newcomer staff, in which they simulated how staff approach clients in different contexts and for different development problems.

12.4 Lessons Learned in Aligning Case Studies with an Organizational Learning Agenda

In the previous section we noted that case studies on development practice are used in different ways and with different levels of systematization for the purpose of organizational learning. Here we can make use of our IGOIL categorization to explain how case studies from these different organizations tap into different levels of learning.

As we see from Table 12.2, different organizations use case studies for learning purposes, but such purposes serve different objectives. We can use the MoF of China and the World Bank as two examples with different purposes. For China’s MoF, learning is external facing, with partners that want to learn from the experiences captured in the Chinese case studies. This external interest may come typically from other governments that want to learn how the Chinese government dealt with a particular development challenge. Learning is done mainly at the interorganizational level: the MoF selects and systematizes experiences to be disseminated, and this external demand is what guides the capture and systematization of knowledge by the MoF.

Table 12.2 How different organizations use case studies for learning purposes

| Learning Category | MoF, China | GIZ, Germany | Brookings – Millions Learning Initiative | World Bank –GDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | X | X | ||

| Group | X | |||

| Organizational | X | X | X | |

| Interorganizational | X | X | X |

The World Bank’s approach is also very much about interorganizational learning, by sharing experiences among institutions on how to address development challenges. However, at the same time there is a specific focus on knowledge retention and organizational learning, with the goal of interpreting and using the knowledge collected through the case studies to support the organization’s business practices and improve performance. The GDI approach focused on contacting particular partners and using group discussion to advance this learning agenda; it also provided training for practitioners to not only become case writers, but to develop capacity at the individual level for transformational change by better understanding the change process.

Table 12.2 also points to some of the different motivations for using case studies as a learning tool. In the case of MoF China and Brookings, for instance, case studies are shown as exemplars of how to do things or ‘what and how things work’ in the spirit of sharing such knowledge outside the boundaries of the organization. At GIZ the focus is to provide practitioners, within and outside the organization, with examples of good practices. Finally, GIZ understands itself as a convener of experiences on transformational processes, with the role of promoting dialogue not only at the practitioner level but also across organizations and countries.

Table 12.2 and the preceding discussion shows that case studies do not need to use the same knowledge-sharing strategy or audience to inform development processes. Case studies can be used as a learning tool to improve performance and implementation in internal practices. They may never be shared directly with other practitioners or stakeholders outside of that organization, but this approach may still spread lessons indirectly through changes in behavior and practices as a consequence of insights captured in the case study. On the other hand, case studies can be used directly to inform counterparts of experiences that provide insights on what works and how. In this instance cases may have more impact on an external organization receiving such knowledge.

Finally, the use of case studies as a learning tool also generates some knowledge value in the process of developing the case study itself, in addition to the output. As has been shown with MoF China, the GDI, and to some extent GIZ, case writers are trained to focus on a problem-driven approach to tackle case studies. These case writers are also practitioners involved in development projects who may be keen to incorporate this approach in future development practices. Further capacity building at an individual level may also take place among the key stakeholders involved. As a case study’s interviewees, they play a role in articulating their experiences, which are captured as knowledge on the “how to” of implementation. As experienced through the preparation of case studies by the four organizations discussed in this chapter, such engagement provides these key stakeholders with a new perspective on how to tackle challenges throughout the implementation cycle, and in the process perhaps generates a change of mindset.