Roman terracotta lamps bearing images of sexual intercourse were in circulation from the late 1st c. BCE until the end of the 4th c. CE. Like all standardized Roman lamps, these objects were made using molds that were fashioned from a wooden or clay master model or other already-made lamps. The reusability of the molds allowed for lamps to be produced en masse and for identical disc-reliefs to be replicated across multiple objects. The copying of lamp-motifs across different workshops is, however, still relatively poorly understood. This is because the scholarship remains primarily focused on tracing the networks of production and trade using Firmalampen that bear name-stamps.Footnote 1 The visual differentiation between the Italian and locally produced lamps is also sometimes complicated. Recent WD-XRF analysis of Firmalampen from Vindonissa has shown that the lamps previously classified by Loeschcke as locally made were in fact Italian imports, produced somewhere in the region of Modena.Footnote 2 More work on fabric analysis is needed to enable us to securely spot imported Italian lamps that could have been the prototypes for locally produced copies in the provinces. It has nonetheless been proposed that symplegmata lamp-scenes were copied from an Alexandrian-Egyptian illustrated handbook of coital positions and that lamps with such images were used for titillation.Footnote 3 Moreover, and in the absence of systematic research, there is an implicit assumption that the sexual lamp-repertoire was stable and that the consumption of this iconography was consistent throughout the Empire. Replicated images of sex on lamps continue to be seen as imitative, with no history and with limited agency.

In this paper I call for a revision of these conjectures. I consider the creation of symplegmata disc-reliefs against the backdrop of the increased connectivity of the globalizing Empire and use descriptive and compound inferential statistical methods to analyze the consumption of sexual lamp-images across 11 Roman provincial sites. The paper demonstrates that the consumption of lamps with sexual disc-reliefs varied both during and across the Empire. Roman provincial communities had preferences for certain representations of sex on lamps. The paper further shows that sexual disc-reliefs have their own structure and rules of creation; disc-motifs are defined by their relations to one another and the wider Roman visual repertoire. These figurative systems were also continually interacting and evolving during the Empire, resulting in representations of sex that were often associated with specific places and historical periods. By introducing new and adapting old motifs, images of sex decorating lamps were also altered to suit their specific contexts, which often resulted in innovative sexual imagery that produced new meanings in more localized settings. This paper is a result of a larger project which looked at how lamps with sexual disc-reliefs constructed sexual discourse in Roman provincial settings. The quantitative findings presented herein should be viewed as complementary to my earlier publication which looks at the iconographic meaning and agency of sexual disc-reliefs.Footnote 4

Quantitative methods have been successfully applied to Roman objects; however, these approaches are novel to Roman sexuality studies.Footnote 5 My analysis considers only lamps with images of human-human and human-animal sexual intercourse. Other scene-types with sexual overtones, such as mythological pursuits, are excluded. Disc-reliefs of explicit sexual acts offer a distinct and identifiable case study in how sexual lamp-imagery came about, how it constructed meaning, and how it was consumed by provincial communities over time. Notwithstanding their overt sexual character, these images cannot be described as erotic.Footnote 6 The 19th-c. establishment of Secret Museums associated with Victorian morality continues to condition our perception of lamps with sexual art.Footnote 7 Some have argued that the stories about the Secret Cabinets are imbued with a false premise of the “censorship myth.”Footnote 8 It is, however, undeniable that the past privatization and pornografication of ancient visual-material culture have shaped the scope and the nature of the modern scholarship. As Mary Beard observes, the establishment of Secret Museums constructed both a state of mind and a particular physical location that has endured in the Classical scholarship.Footnote 9 Archaeological evidence, however, has shown that lamps with symplegmata scenes were used across different social contexts;Footnote 10 these objects had multiple and complex cultural lives. Not all symplegma disc-reliefs functioned to provoke arousal, nor were they necessarily perceived as obscene by ancient viewers. For these reasons, I refer to the lamp symplegmata images as sexual rather than as erotic.

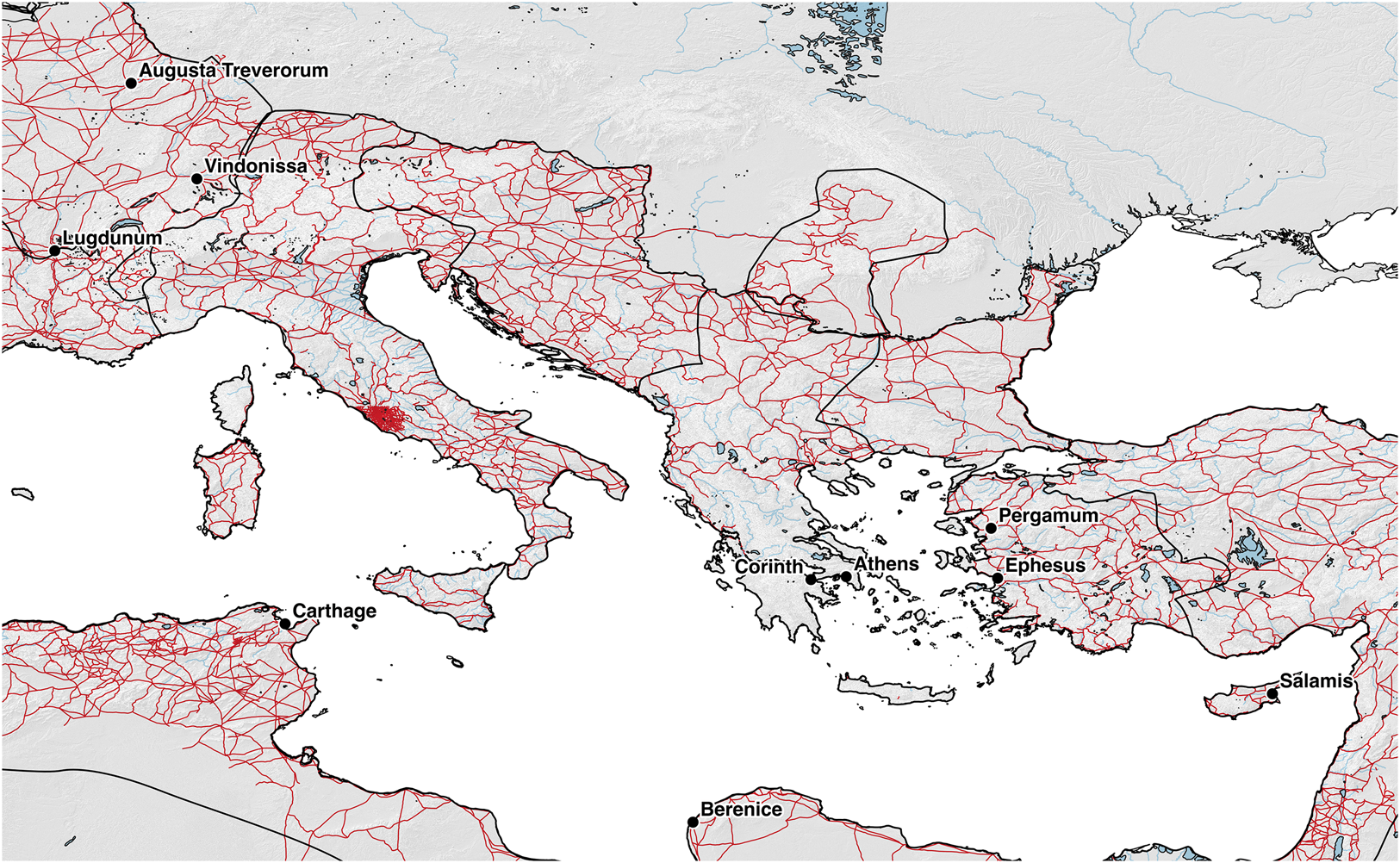

The corpus selected for this study does not claim to be exhaustive but rather aims to give a representative overview of lamps with images of sex from important Roman provincial sites (Fig. 1). My analysis is based on 619 lamps that were gathered systematically through catalogues and fieldwork from 11 locales: the Athenian Agora, the Kerameikos, Corinth, Pergamum, Salamis (Cyprus), Berenice (Benghazi), Trier, Vindonissa, and Carthage.Footnote 11 I obtained the Lyon data from Arnaud Galliègue, and lamps from Ephesus were gathered via excavation reports and first-hand study of the material. The selected sites provide a robust dataset in terms of both quantity and diversity. My data choice was driven by the possibility of statistically comparing multiple distributional and representational trends over time and across broad geographical areas. Because many lamps were recovered from rubbish fills or belong to legacy data, they are missing a comprehensive archaeological record. Selection of data from relatively dissimilar sites was important as it enabled me to assess whether the detected trends varied due to characteristics specific to individual sites, such as demography and economy. Unlike lamps from museum collections, the gathered objects have secure site provenance.Footnote 12 This information has allowed me to contextualize lamps with sexual disc-reliefs in the cultural and historical networks that framed their creation and consumption, as well as their emergent effects.

Fig. 1. Roman provincial sites considered in this study and their positions within the Roman road networks (Ancient World Mapping Center files used: ‘carte_hillshade’, ‘coastline’, ‘ba_merge’, ‘ba_roads’, ‘inlandwater’, ‘roman_open_water’, ‘roman_empire_ad_117’ <http://awmc.unc.edu/wordpress/omap-files/> [Accessed: 7 January 2023]). (S. Vucetic.)

Quantitative methods

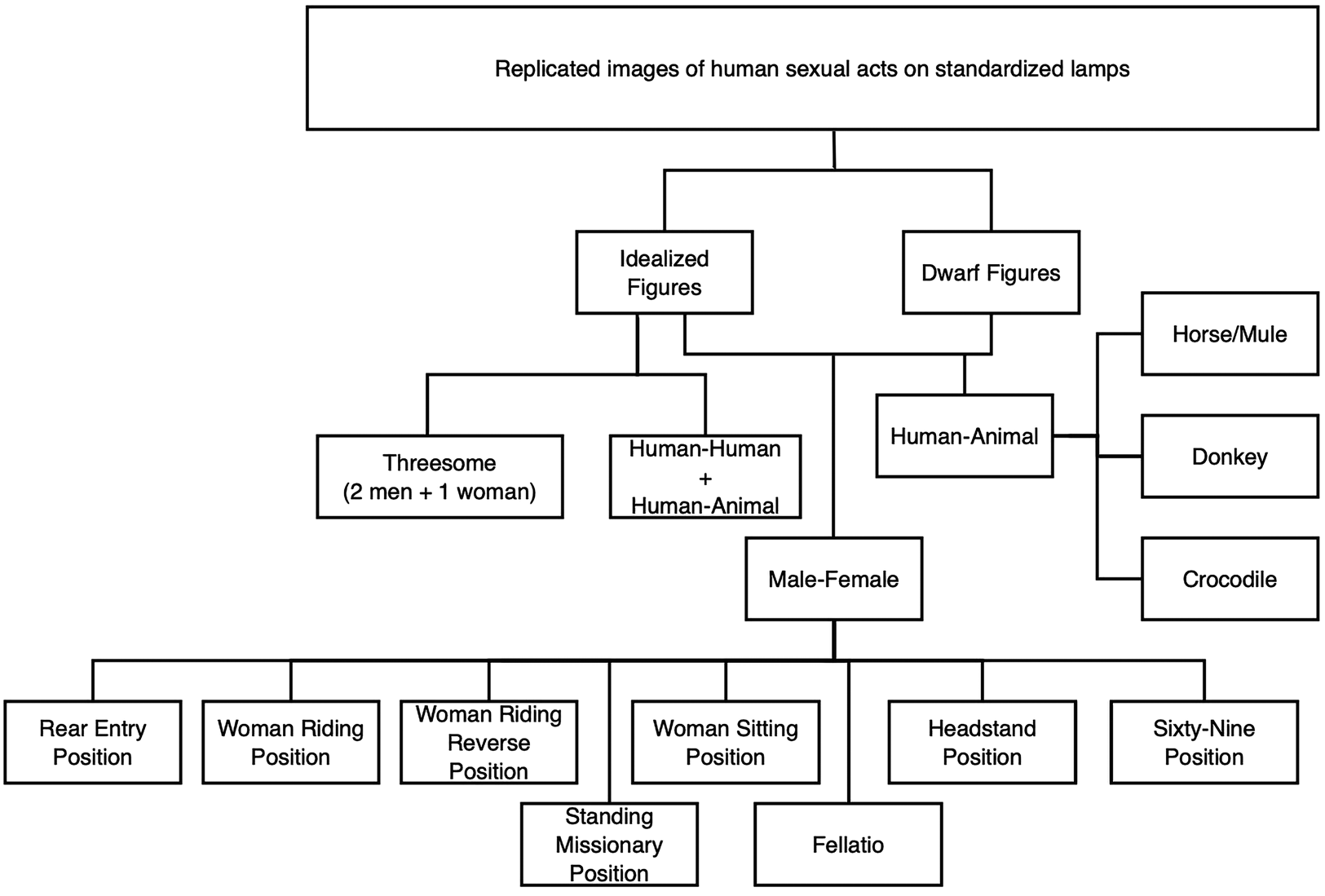

The aims of the quantitative analysis were to: (1) determine key trends – reoccurrences, variations, and correspondences – in the spatio-temporal patterns of representation of image-types; (2) chart the differences and similarities in the sexual disc-reliefs within and between locales and over time; and (3) locate sexual themes and motifs that were in circulation between sites and were traveling through various cultural and economic networks. To facilitate comparisons of the frequencies of different sexual disc-reliefs, I organized images according to figure and coital position types (Fig. 2). This data was also supplemented by basic iconographic description. To enable more precise statistical analysis, I utilized the lamps’ typo-chronological features and placed the disc-reliefs into a chronological sequence structured around 50-year intervals.Footnote 13 Descriptive statistical data, such as bar charts and tables, were most suitable for plotting the general spatial and chronological comparisons in the distribution of the gathered images and for comparisons of the proportions of different image-types across the regions in each period.

Fig. 2. Categorization of iconography of sex on standardized lamps. (S. Vucetic.)

I used compound inferential analyses for important comparisons and to identify deviations of observed frequencies of motifs and image-types from expected frequencies of the same. Inferential statistics use a sample from a population to assess the probability of the relations between measured variables as consistent. Because their application facilitates drawing conclusions about the larger population from which the data is gathered, I was able to determine whether the quantitative findings from the gathered lamps can be generalized to a specific site, cultural unit, or historical period, or if they are artifacts of the sampling procedure. I thus conducted a series of Chi-square and Fisher's exact test analyses against a series of questions (hypotheses) with the aim of assessing whether there were significant relations between:Footnote 14

1. Imagery and time: Does the frequency of specific iconographic elements (e.g., figure type, coital position) change over time? Are image-types or iconographic elements associated with specific historical periods? Is the rate of change consistent or variable?

2. Imagery and place: Is the frequency of image-types and iconographic elements most commonly associated with particular sites, cultural units, or inter-regional contexts?

I have avoided discussing the data as a proportion of the total number of lamps from all sites. As Trier, Lyon, Carthage, and Vindonissa do not have any lamps with symplegma reliefs after the mid-2nd c. CE, and because these objects continue to circulate in the Greek sites until the end of the 4th c. CE, any analyses examining sexual disc-reliefs as a proportion of total number of lamps after the 3rd c. CE will inevitably produce skewed results. Likewise, the Kerameikos is a unique site in that it was the potters’ quarter, which yielded a disproportionally large number of lamps (292 lamps). For these reasons, the Kerameikos data has the potential to both illuminate the nature of provincial lamp production and skew the resulting picture of provincial consumption. In order to get a sense of what kind of sexual disc-reliefs were produced on a local level, the Kerameikos data was analyzed independently but integrated into the discussion section of the paper.

In the following pages, I first situate sexual disc-reliefs within their social and historical context and outline the structure and logic of their creation. I then examine the trends that characterize this lamp-iconography and that are derived from the statistical data. In the final section of the paper, I discuss the striking changes that occur in the 3rd c. CE and explore some of the possible reasons that account for disparate iconographic and consumption trends across different Roman provincial locales.

Situating replicated sexual disc-reliefs

Visual representations of sexual intercourse begin to decorate terracotta lamps during the Early Imperial period. This is the time when a new style of Roman sexual art also developed, along with a broader process of standardization of the Roman material and visual culture.Footnote 15 Lamps with images of sex appear in the provinces following Roman military interventions; by the 1st c. CE, these objects were produced by local workshops and available throughout the Empire. Sexual disc-reliefs remained in circulation until the 4th c. CE, albeit in different intensity. After the 2nd c. CE, such images disappear from the lamp repertoire at the Latin-speaking sites but continue to circulate in the Greek East until the end of the 4th c. CE.

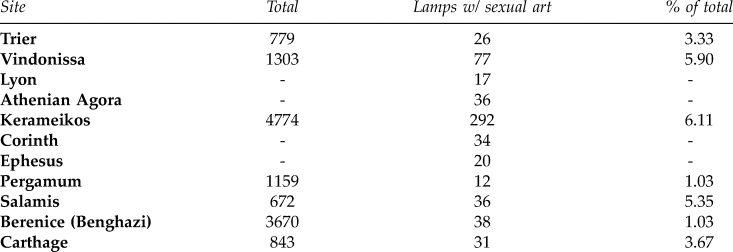

Museum collections suggest that in the Empire these objects were plentiful.Footnote 16 Because lamps with symplegmata scenes were commonly deemed “obscene” and subsequently isolated from their cultural and archaeological contexts, museum collections are better indicators of the recent centuries’ collecting practices than of ancient consumption trends. The gathered data shows that sexual disc-reliefs typically make up 1.03%–5.90% of the total lamp assemblage from each site (Table 1). These numbers correspond to the patterns previously observed by Eckardt (1.97%–4.62%) and me (3.10%–5.95%), although it should be noted that in some regions, such as Pannonia, lamps with images of sex appear to be entirely absent.Footnote 17 Based on these observations, we can then say that in the Roman world sexual intercourse was relatively popular lamp decoration although not as frequent as initially claimed.

Table 1. Proportion of lamps with sexual disc-reliefs from the total of lamps from each site. (Most of the gathered lamps belong to legacy data. Because not all excavated lamps have been recorded or preserved, obtaining the total number of lamps from each site was not always possible.)

No doubt, mold-making technological innovation and the rapid increase in connectivity helped sexual art on lamps to quickly become mass-produced and widespread. The mold-making practice also assisted iconographic replication, aiding the production of formulaic images of sex on lamps throughout the globalizing Empire. How this iconography came about and how it generated meaning is then better understood using concepts of universalization and particularization associated with the globalization process.Footnote 18 As Versluys explains, universalization means styles and motifs that initially belonged to a culture are separated from that specific culture so they can play a role in a larger system (koine).Footnote 19 In such a way, these iconographic elements also lose part of their original meaning. Particularization occurs in local contexts through the process of borrowing from the universally shared and globally available koine. Particularization also allows for iconographic elements to acquire new meanings.

To create sexual disc-reliefs, lamp-makers frequently borrowed, adapted, and repurposed schemes and elements drawn from widely circulated iconographic repertoires. The process of image-making involved transmission of figural patterns by means of different mechanisms. When portraying different kinds of copulating bodies, lamps rely on already established artistic traditions. The 5th-c. BCE stylistic convention for conveying the Classical Greek ideal body provides the framework for the sexual representation of ordinary (idealized) body forms. Some Early Imperial lamps also reproduce iconographic schemata depicting idealized symplegma scenes from the Arretine ware.Footnote 20 Iconographic schemata are also shared between lamps and terra sigillata produced in the provinces (Fig. 3). This transmission of figural patterns is not so surprising given that molded lamps and pottery were frequently produced in the same workshops. Brendel and, more recently, Jacobelli have suggested that the symplegmata disc-scenes were copied from an illustrated book of coital positions.Footnote 21 The constancy of the sexual themes and motifs across lamp disc-reliefs, however, seems to have been a consequence of the continued circulation of certain styles, schemata, and iconographic motifs that sustained popularity across a range of media including pottery, coins, and wall-paintings.

Fig. 3. Canopy symplegma decorating Late Roman Cypriot plate and Athenian lamp. Athenian Agora; Inv. P 3553 and L 3880. (Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations ©Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development [H.O.C.RE.D.]. S. Vucetic.)

To generate symplegma disc-reliefs involving dwarfs, lamp-makers relied on stylistic conventions which first appeared in the late 1st-c. BCE Roman Nilotic scenes.Footnote 22 The dwarfs’ bodies have large heads and short legs, and female dwarfs often have protruding buttocks and sagging breasts. Lamp-makers repurposed elements of Nilotic scenes, mostly figural arrangements (coital positions) and stylistic features of the dwarfs’ malformed bodies, to generate images of copulating dwarfs. The transference of dwarf symplegmata from wall-paintings and mosaics onto mass-produced and portable lamps transformed the social context of this art from Roman domestic ideology to a variety of settings including military and funerary situations.Footnote 23 It can be argued that the style of sexual disc-reliefs was created by the conscious appropriation of motives and styles from the available past and present visual repertoire. Transference of these iconographies from one medium to another further points to different cultural and economic networks through which objects and imagery were moving. Because of the different natures of the media bearing sexual iconography and the different contexts in which they were viewed, these repeated images had a potential to generate dissimilar visual effects and be open to different readings. In the next section, I consider in more detail how sexual disc-images were created and how repeated combinations of elements generated meaning across the lamp repertoire and in different contexts.

Rules of creation

Disc-reliefs almost uniformly depict genital, or potentially anal, penetrative acts involving human male-female and human-animal pairs in a range of coital positions.Footnote 24 Of 619 gathered lamps, a single 1st-c. CE Pergamene lamp shows male-male sex, two Late Roman lamps from Salamis depict a threesome (one female-two male figures), and two lamps show a female figure performing fellatio.Footnote 25 Cunnilingus and female-female sex are not depicted at all. Whilst the multiple-participant sexual depictions might be a function of the size of the visual field, more complex but non-sexual relief decorations occur, suggesting that the lamp-makers exercised some agency when selecting which sexual schemata were appropriate for these portable objects.Footnote 26 The size of the visual field was evidently, if a factor at all, not the deciding one in the selection and creation of this iconography.

Sexual disc-reliefs are characterized by well-defined and consistent figurative systems within which certain representational rules appear to be immutable. For example, the motif showing the man penetrating the reclining woman from the front appears only in association with the idealized figures. Similarly, animal-dwarf figural arrangement creates only one representational type, in which the dwarf woman copulates with the crocodile. These specific rules of creation rely on the system of unique and exclusive relations between the specific iconographic elements and point to different systems of value and representation in the production of their meaning and the effect. They also reveal that the meaning of sexual disc-reliefs is contingent upon the nature of their elements and their structural disposition.Footnote 27

As previously mentioned, mold-manufacture assisted replication and the standardization of both lamps and their figural systems. Thus, the most striking feature of the sexual disc-reliefs is visual sameness. Standardization, however, also encouraged change through the process of alterations in terms of motif arrangement.Footnote 28 Overall images were produced through transformation and adaptation of elements and through substitution of old motifs with new ones. Therefore, sexual scene-types have representational variants that are principally produced by modifying figural gestures, postures, and gaze. For example, disc-reliefs showing idealized figures in rear-entry coitus have six variations: (a) woman looking straight ahead, (b) woman looking down, (c) woman looking back at the man, (d) woman reclining on her side, (e) standing rear entry, and (f) symplegma with child. Scene-types also incorporate motifs that are repeated elsewhere across the lamps’ sexual repertoire. As such, images are bound by a number of shared and consistent elements that form the basis of each thematic structure (scene-type). The result is a remarkable amount of diversity within perceived representational homogeneity. For example, the idealized rear-entry scene-type has three standardized Italic variants which were established sometime in the early Principate (Fig. 4). While iconographic variations within each rear-entry scene-type point to the flexibility of the visual structure, the three representational variants remain bound by their style and constant elements – the coital position, the bed, and the figural type – which form the basis of each thematic structure. The representational range produced through these thematic variants is therefore not broad enough to transform or disrupt the character of the transmitted tradition. These unifying and consistent motifs both encourage standardization across the sexual repertoire on lamps and form the backbone of its visual structure.

Fig. 4. Three standardized variations of rear-entry position in idealized human representations: woman looking straight ahead; woman looking down; woman looking back. (Kantonsarchäologie Aargau, CH-5200 Brugg. Inv. nos. 41.276; 3431; 3432. S. Vucetic.)

Obviously, following Roman Imperial expansion and the associated intensification in connectivity, the visual system of sexual disc-reliefs developed as (in certain respects) unstable and therefore complex. The flexibility of the structure, the form of the schemata, and their ideational value allowed for semantic elements to be combined in novel ways or mixed with new motifs. In principle, this process of adding, extracting, and transforming elements is indefinite, resulting in creation of sexual disc-reliefs that diverge from the standardized visual templates. This process also opened possibilities for the disc-images to generate new meanings in more localized settings.

For example, in the military fort at Vindonissa, during the 1st c. CE, the standardized disc-motif in which the lying man is straddled by the woman (woman-riding position), is altered so that the woman is holding a shield and the sica-type dagger, equipment associated with the thraex gladiators (Fig. 5). Because most of the lamps with sexual decorations were recovered from the rubbish fill, it is unclear if at Vindonissa lamps with this image were used in the context of the military barracks or within other social places, such as taverns and inns.Footnote 29 What is certain, however, is that, at least during the 1st c. CE, lamps with sexual disc-reliefs were used within the fortress and the soldiers stationed at Vindonissa were primarily recruited from Italy.Footnote 30 The militarized setting and the demography of the soldiers may provide a useful point of departure for exploring the meaning and potential effect of this localized sexual iconography in Vindonissa.

Fig. 5. Left: lamp with standardized image of a woman straddling reclining man; right: lamp with localized variation in which woman is holding shield and dagger. 1st c. CE. (Courtesy C. Raddato.)

Because the Roman model for idealized sexual behavior promoted phallocentric masculine expressions of power, domination was one way of performing the manliness of the vir.Footnote 31 Castration, be it symbolic or physical, compromised the Roman masculine ideal.Footnote 32 For Roman soldiers who looked at this image, the unusual depiction of combat-like aggression and sexual domination would thus have likely evoked amusement.Footnote 33 The dynamic portrayal of the woman's body as she advances towards her lover, casts her in a dominant role; she is the agent of her sexual desire. If we consider that Roman military masculinity was coupled with martiality and that the use of a dagger embodies a capacity for violence, the woman's transgressive actions emerge as important.Footnote 34 Following the phallic cliché of the sword, we can also suggest that, with a weapon in her hand, the woman is symbolically equipped with a phallus. Visual portrayal of the female sexual agency and the symbolic male genitalia she holds in her hand materialize the woman as a monstrous phantasy – femme castratrice – a potent threat to Roman masculine expressions of power and autonomy.Footnote 35

The social status of Roman soldiers, however, complicated the relationship between masculinity and autonomy.Footnote 36 In the colonized territories, the masculinity of Roman soldiers was simultaneously reinforced through the exercise of power over the local civilian population and challenged through the actions of their commanders and superiors.Footnote 37 The lamp iconography of a woman's sexual performance with the dagger and shield may then point to anxieties incited by the precariousness of the Romano-Italian soldiers’ socio-sexual positioning within the broader 1st-c. CE Roman hegemonic masculinity discourse. The lamps with this image of combat and sex were not in high circulation – only three have been recovered from Vindonissa. Yet the reoccurrence of this curious image at Vindonissa as well as in other places with soldier and veteran communities, such as the Iberian Peninsula and Cologne, suggests that some standardized sexual lamp-imagery was altered to address more localized predilections and to speak to specific audiences.Footnote 38 The meaning and the effect of sexual disc-reliefs developed in relation to their contexts of consumption.

By the 3rd c. CE, lamp-makers were producing sexual disc-reliefs that are markedly different from the imagery that was circulating during the Principate. This is best shown when comparing the standardized Early Imperial and the 3rd-c. CE Greek representations of a couple in rear-entry position (Fig. 6). While the core motifs (figural type and coital position) remain the same, addition (child) and subtraction (bed) of iconographic elements produce a radically altered representation of sex that also undoubtedly generated new meaning. In this new lamp-image, the man approaches the woman from behind and is lifting the back of her dress. Although heavily draped, the woman's buttocks are exposed to the gaze of both the man and the viewer. In Oziol's view, a type of wreath surmounted by the inscription ΛANAΡΙΩ above the figures provides clues to the iconographic meaning.Footnote 39 She suggests that through a clever play on words, the inscription indicates a place of questionable reputation, or that a carder is the intended recipient of lamps bearing this Greek image-type. While such interpretation is conceivable, it is more likely that the image simply had a comical effect generated by the man's disproportionally large erect phallus and the unawareness of the woman who is busy playing with the child. Symplegma-with-child disc-reliefs were produced in Athens and in circulation in Athens, Corinth, and Salamis. Their pronounced regional distribution suggests that this new sexual iconography was also universalized, at least within its pan-regional context, which was characterized by common Hellenic language, social practices, and cultural knowledge. Although radically different from the earlier standardized types, through shared style and core motifs, this locally produced and regionally distributed lamp-iconography makes references to the shared sexual repertoire on lamps.

Fig. 6. Left: Early Imperial lamp with standardized representation of rear-entry symplegma; right: Late Roman lamp with symplegma with child. (Kantonsarchäologie Aargau, CH-5200 Brugg. Inv. no. 3431; Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Athen KER 23.923/ Ker RL 1972d. ©Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development [H.O.C.RE.D.]. S. Vucetic.)

The Vindonissian and Athenian examples show that forms and elements from the available visual repository were combined in novel ways, resulting in the local particularizations of the symplegma disc-reliefs across the globalizing Empire. The locally innovative sexual lamp-imagery did not come into being in isolation but was connected to the general visual repertoire of sexual art on lamps. Through the process of particularization, iconographic elements in the Vindonissian and Athenian symplegma variants were reframed in order to function as a means of speaking to soldiers and commenting on Late Roman-period concerns respectively. As distinctly local innovations, the symplegma with child and the symplegma with shield and dagger scenes nonetheless share common features with the other sexual disc-reliefs. In this way, these Early Imperial and Late Roman localized iconographic variations produced, reproduced, and innovated the shared Roman replicated sexual repertoire on lamps.Footnote 40

In the following pages and based on the statistical data, I discuss the key global, pan-regional, and local consumption trends of sexual disc-reliefs in the Roman world.

General consumption trends

Lamps decorated with human-human and human-animal symplegmata scenes appeared in the provinces following Roman military interventions and remained in circulation until the end of the 4th c. CE. The arrival and the longevity of these lamp-images, however, was not synchronous across the Empire. In Athens, symplegma disc-reliefs appeared somewhat early, as attested by a 1st-c. BCE lamp characterized by Late Hellenistic style features.Footnote 41 The peak consumption of these objects is during the first two centuries CE, when they are in circulation across both Latin and Greek sites. After this period, images of sex disappear from the Latin provincial lamp repertoire and are only found in the Greek-speaking locales, where they remain until the end of the 4th c. CE.

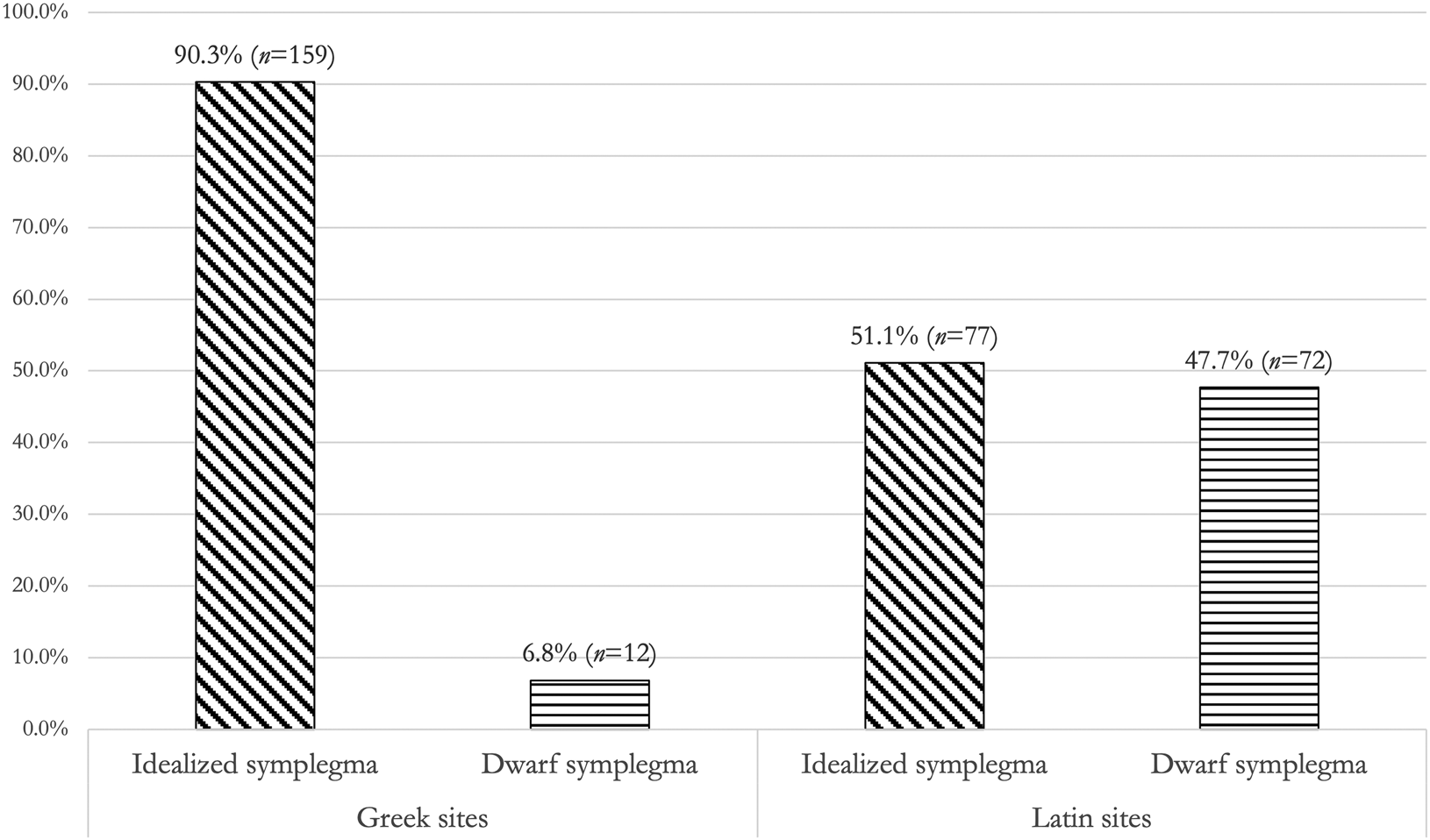

Thinking in broad strokes, idealized symplegma scenes are prevalent, forming 72.2% (n=236) of the 327 lamps gathered (excluding Kerameikos). Their peak frequency is during the 1st c. CE, when they are in circulation across all studied provincial sites. This is also the period when idealized symplegma disc-reliefs are most frequent in the Latin-speaking locales. In the Greek East, however, lamps with such images are most frequent in the 3rd c. CE. Moreover, Figure 7 shows that the Greek-speaking sites have a high proportion of idealized symplegma scenes, whereas at the Latin sites, lamps with both idealized and dwarf symplegmata scenes were consumed at roughly the same frequency.

Fig. 7. Distribution of idealized and dwarf symplegma disc-reliefs (excluding the Kerameikos data) (uncertain n=7). (S. Vucetic.)

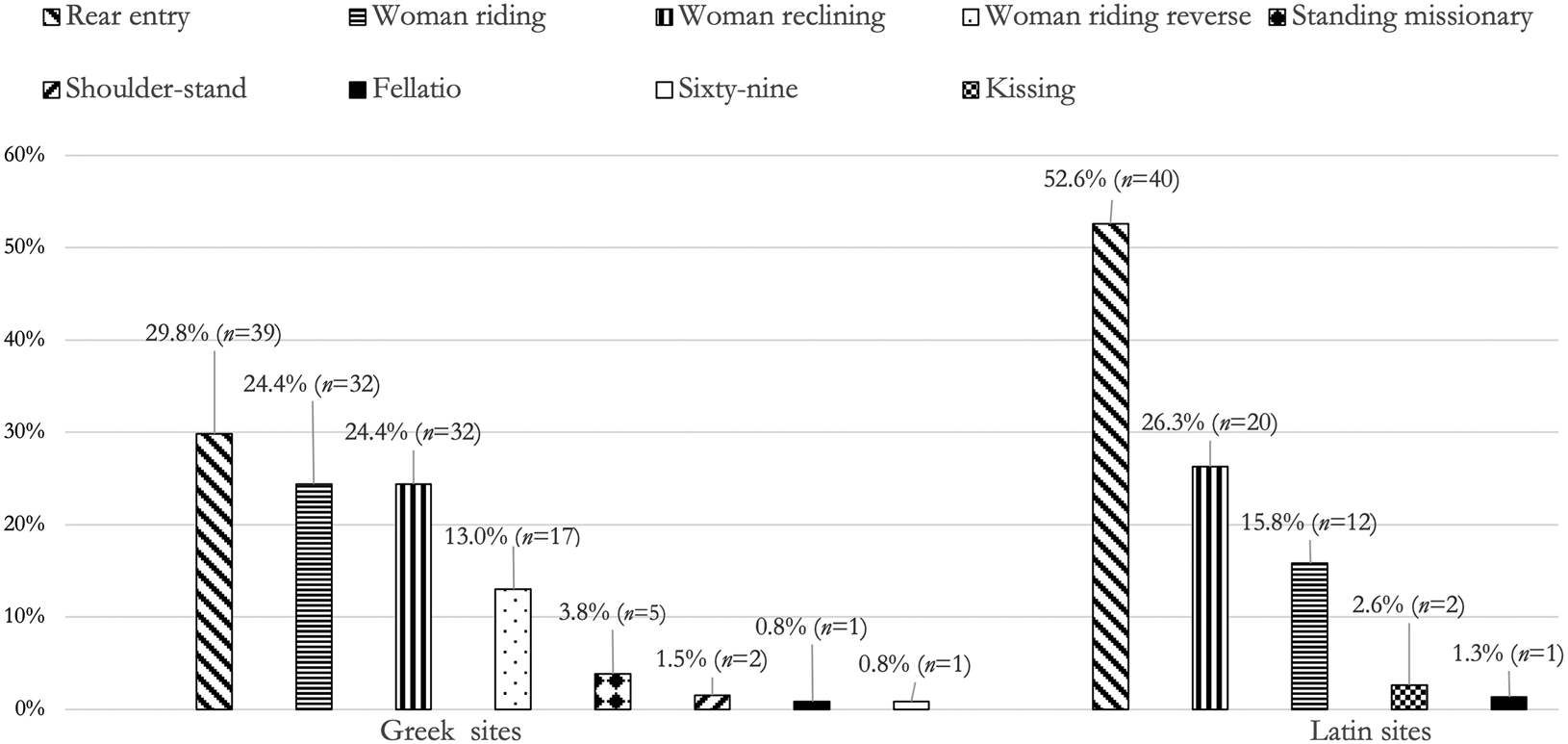

Plotting of the gathered disc-reliefs indicates that idealized symplegma image-types and their variants occur in representational series that are associated with specific places and time periods (Supplementary Tables 1–4). Images of idealized figures in rear-entry coitus are prevalent across the gathered corpus, and lamps with such decorations were circulating extensively. The 1st-c. CE provincial communities favored this type of sexual scene (38.2%, n=79), although woman-reclining (25.1%, n=52) and woman-riding (21.3%, n=44) coital motifs also enjoyed popularity. By the early 2nd c. CE, however, portrayals of couples in the woman-riding position appear to fall out of fashion. The rear-entry scenes are in high circulation at the Latin sites, where they make up about a half of all the idealized symplegma disc-reliefs. Across the Greek locales, besides the rear-entry scenes, disc-reliefs depicting sexual intercourse in woman-riding and woman-reclining positions are also frequent. In general, lamps consumed in the Greek East exhibit a greater variety of coital positions than those from the Latin-speaking sites (Fig. 8). Some sexual disc-reliefs, however, have very limited distribution: lamps with scenes showing the woman-riding-reverse position are found only in Berenice (Benghazi), Athens, and Corinth, whilst lamps depicting shoulder-stand sex and sixty-nine position are limited to Salamis.

Fig. 8. Distribution of sexual positions/acts in idealized symplegma scenes across Latin and Greek regions. (S. Vucetic.)

Dwarf symplegma scenes decorate lamps that were circulating during the 1st and 2nd c. CE. They are mainly consumed in the Latin locales, where they form 47.7% (n=72) of the total number of lamps (Supplementary Tables 5–6). When compared to the idealized symplegma disc-reliefs, dwarf symplegma disc-reliefs show a narrow coital range. Dwarfs are depicted copulating in rear-entry, woman-riding-reverse, and woman-riding positions (Fig. 9). The rear-entry (53.5%, n=38) and the woman-riding-reverse (43.7%, n=31) positions are the most frequent representational choices. The woman-riding position was only consumed at the Latin sites (Fig. 10; Supplementary Tables 5–6).

Fig. 9. Standardized lamps with dwarf symplegma image-types. Vindonissa 1st c. CE. (Kantonsarchäologie Aargau, CH-5200 Brugg. Inv. nos. 41.276; 3431; 3432. S. Vucetic.)

Fig. 10. Distribution of coital positions in dwarf symplegma scenes; Latin vs. Greek sites. (S. Vucetic.)

Of the lamps with dwarf symplegma scenes, 46.4% (n=39) can be dated to the early 1st c. CE. The high frequency of such representations continues into the late 1st c. (42.9%, n=36), after which dwarf symplegma decorations decrease in popularity. In the northwestern urban centers of Lyon and Trier, the decreased consumption of dwarf symplegma disc-reliefs coincides with the general decline in popularity of Nilotic scenes on other media after the 2nd c. CE. Although in North Africa Nilotic scenes remain popular well into the 4th c. CE, at Carthage images of copulating dwarfs disappear from the lamp repertoire after the 2nd c. CE. Lamps with dwarf symplegma disc-reliefs are entirely absent in Athens and Corinth, whereas at other Greek-speaking sites, this lamp iconography is in circulation during the 1st c. CE, albeit in very low intensity. This regional consumption pattern corresponds to broader distributional trends of dwarf iconography in Greece, with only a few examples of Nilotic representations in mosaics having been recovered, possibly commissioned by migrants.Footnote 42 The pan-regional distribution of lamps with sexual scenes involving dwarfs suggests that these objects were circulating in the locales where Nilotic art more generally was also consumed.

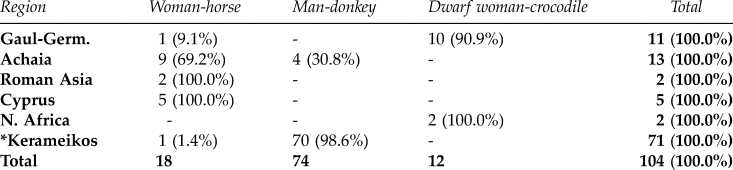

Human-animal sexual scenes have the lowest distribution, making up 6.0% (n=37) of the gathered corpus. These images depict woman-horse symplegma, men copulating with donkeys, and dwarf woman-crocodile sex. In general, bestiality disc-reliefs are more frequent in the Greek East. In the Latin West, most of such scenes depict the dwarf woman copulating with the crocodile. Inferential analyses point to statistically significant correlation between the Athenian Agora and human-animal disc-reliefs, best explained by the consumption of lamps with man-donkey and woman-horse symplegma scenes at this site (Table 2; Supplementary Table 8).Footnote 43 The representational and distributional diversity of lamps with sexual disc-reliefs points to different provincial preferences for specific kinds of representations of sexual intercourse. They also point to the agency of sexual-disc-reliefs and the construction of meaning in colonial situations.Footnote 44

Table 2. Distribution of human-animal symplegma scenes.

Localized consumption trends

Provincial communities present dissimilar styles of consumption over time. At Vindonissa, lamps with sexual decorations are primarily associated with the soldier population that was stationed at the site during the 1st c. CE. Meanwhile, the newly urbanized communities at Lyon and Trier use lamps with idealized symplegma scenes during the 1st c. CE, whilst at Carthage these objects are consumed until the mid-2nd c. CE. In Pergamum, idealized sexual scenes are in circulation until the 3rd c. CE, at Berenice (Benghazi) until the mid-3rd c. CE, and in Athens, Corinth, and Ephesus until the end of the 4th c. CE.Footnote 45 In Salamis, after the 2nd c. CE decline, sexual disc-reliefs appear with higher frequency again in the 3rd and 4th c., after which images of sex disappear from the Cypriot lamp-repertoire. Overall, in the Greek-speaking localities, lamps with sexual art continue to be involved in people's lives much more consistently and for a longer time than in the Latin northwest.

These consumption trends are somewhat to be anticipated, given that the Greek sites were also connected through networks of culture-based transregional Hellenic consciousness, which predated the Roman conquest.Footnote 46 From the 6th c. BCE, the Greeks were also producing a distinctive form of wheel-made lamp, and by the Hellenistic period they were making lamps using molds.Footnote 47 Lamps were thus implicated in a range of Hellenistic social practices well before the Roman invasion. In the Greek East, communities would also have had a strong familiarity with the Hellenistic visual koine that the Roman lamp art was drawing from. Therefore, the impact of Roman-type lamps at the Greek sites was not located in the introduction of new iconography or cultural practices involving lighting equipment. Rather, over time these objects and their imagery unlocked possibilities for cultural innovation for local lamp-makers and consumers, in terms of both lamp-forms and sexual disc-reliefs.

At some Latin sites, however, molded lamps, including those with sexual disc-reliefs, were objects (at least initially) linked to representatives of the Roman state. Terracotta lamps with symplegma scenes were deposited in the graves of the Early Imperial freedmen who had held public office at Carthage.Footnote 48 Meanwhile, at Vindonissa, the post-1st-c. CE drop in overall lamp consumption coincides with the changes in the military situation throughout eastern Gaul and Germania. In 75 CE, the frontier was shifted to the Neckar-Odenwald limes meaning that Vindonissa became a hinterland. After 101 CE, the camp continued to accommodate only a fraction of the military personnel. The nearby civilian settlement also significantly shrank due to its economic links to the military fort.Footnote 49 On a practical level, lamps were novel and foreign objects which required an expensive imported fuel. As Reece points out, their utility became important in the context of multi-roomed structures, such as military barracks. In Vindonissa, for the local civilian population, who mostly resided in a single-roomed dwellings, a central hearth or a cheap candle would have provided more than enough light for daily activities.Footnote 50 While the statistical data suggests that lamps with sexual disc-reliefs gained relative popularity amongst civilians in the 2nd c. CE, at Vindonissa, the local community evidently did not so readily take up sexual disc-reliefs or lamps more generally. In Vindonissa, sexual disc-reliefs were primarily linked to the military population and numbers rose and fell according to the arrival and departure of personnel.

By way of contrast, the newly established urbanized communities at Trier and Lyon more readily incorporated Roman lamps into their lives.Footnote 51 From the Augustan period onward, the extensive road networks, the flow of goods, and the civilian urbanization process helped to rapidly situate these newly formed communities within the Roman socio-political system.Footnote 52 This is attested in particular by the changes in the funerary deposits at Trier, which stand out for high percentages of lamps, along with platters, cups, and glass vessels.Footnote 53 Pitts observes that in this provincial urban center, terra sigillata and especially lamps and glass were a part of “a more exclusive and urban-focused style of consumption.”Footnote 54 Because the 1st-c. CE funerary deposits at Trier also include lamps with sexual disc-reliefs, the local purchase and use of this material culture fits into the styles of consumption linked to the newly formed Roman provincial urban communities.Footnote 55 Lamps with sexual disc-reliefs were, then, also used as both cultural markers and expressions of status. This pattern is further present in pre-Flavian Roman Britain, where general lamp consumption is also strongly linked to the military and the urbanized civilian population.Footnote 56

Notwithstanding the locally developed representational variations, the sexual repertoire that was circulating in the Latin sites strongly corresponds to the images designed for the Italian lamps. The general homogeneity of the sexual repertoire on lamps across Italy and the Latin northwest may have been a consequence of the increased mobility and connectivity between these regions, allowing for lamps and other objects to travel over greater distances. Some Italian lamps were likely arriving into the freshly integrated territories by means of intensified economic networks, including via Italian potters who established their workshops in the colonized regions. In Vindonissa, the presence of both Italian imports and locally produced lamps suggests that some soldiers and their families initially brought Italian lamps with them and then later purchased locally made lamps from the traders who were operating near the military base.Footnote 57 Pottery kilns and craft workshops uncovered at the outskirts of the civilian settlement in Windisch point to the presence of a commercial network that was established to meet the demands of local soldiers and possibly also the civilian population of the nearby settlements.Footnote 58 The presence of this localized imagery points to the tastes of a provincial clientele whose attention, at least on some level, lamp-makers were aiming to attract.Footnote 59 That being said, in the absence of more comprehensive fabric analysis it remains unclear whether the lamps with localized representational variants were produced by the same workshop at Vindonissa.

The situation in the Greek East was more complex. At Pergamum and Ephesus, the early 1st-c. CE lamp-types combine Hellenistic and Roman morphological traits. However, it appears that this was not a commercial success. Giuliani observes that the Early Roman Imperial imported lamps did not affect the local Hellenistic stylistic tradition and that it was only from the second quarter of the 1st c. CE that local workshops begin to produce Italian-type lamps.Footnote 60 Across the Aegean, in mainland Greece, the Italian-type lamps and their (sexual) decorations arrived via Patras and Corinth.Footnote 61 Soon after, at these new colonies, workshops were producing lamps by copying the imported Italian models. In Corinth, Roman-type lamps began to be locally produced in the early 1st c. CE. In Athens, Italian lamps with a volute nozzle enjoyed some popularity during the Augustan period, and this also appears to be the only time when Italian-made lamps with sexual disc-reliefs were imported by the city in any quantity.Footnote 62 In Athens, however, and despite a reasonable number of Italian imports, Hellenistic-type lamps continued to be produced for some time. More generally, as Rotroff points out, Athenian lamps deriving from post-Sullan contexts exhibit strong Greek stylistic (typological) features.Footnote 63 Rotroff proposes that the conservativism of the Athenian lamp-makers was driven by complex ideological forces associated with Greek cultural resistance.Footnote 64 This proposition is plausible, particularly when we observe that as early as the 2nd c. CE, Greek lamp-makers begin to develop their own lamp forms and disc-relief iconography.Footnote 65

During the 3rd c. CE, the Athenian lamp industry underwent an economic and artistic revival. Attic lamp-makers, although retaining the basic features of the Corinthian lamps, developed a lamp-style of their own.Footnote 66 This period is also marked by the highest frequency (relative and absolute) of lamps with symplegma disc-reliefs in both Athens and Corinth and the emergence of a novel sexual repertoire on lamps (Fig. 11). The Kerameikos workshops produced lamps with this new iconography in the relatively short period between 250 and 350 CE. Nearly all Attic lamps with this novel sexual lamp-art originated from the ΠΙΡΕΙΘΟΣ workshop, suggesting that, at least in this period, Athenian production of symplegma disc-reliefs was linked to workshop specialization.Footnote 67 The new 3rd-c. CE sexual repertoire also had pronounced pan-regional distribution linked to cultural networks that were only indirectly influenced by the Roman state. Lamps with canopy symplegma were consumed in Achaia and Ephesus, disc-reliefs showing symplegma with lamp stand were circulating in Pergamum and Berenice (Benghazi), whereas lamps with symplegma-with-child disc-reliefs enjoyed popularity in Ephesus and Salamis. The narrow distribution of symplegma with bearded man and man-donkey disc-reliefs suggests that the Kerameikos workshops produced lamps with these images exclusively for the Athenian clientele.

Fig. 11. Left to right: Symplegma with old man (Agora L 2264); Symplegma with lamp stand (Corinth L 803 (1198)); Symplegma with child (Ker RL 1972d/KER 23.923); Canopy symplegma (Agora L 3880); Man-donkey symplegma (RL 1990a/KER 23.948). (Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA and Agora Excavations and the Kerameikos, DAI: ©Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development [H.O.C.RE.D.]. S. Vucetic.)

Two key trends stand out in the data. First, in the Latin-speaking regions, sexual disc-reliefs experience a terminal drop after the mid-2nd c. CE, and second, for the Greek-speaking sites, the 3rd c. CE is a period of iconographic innovation and the phase of increased consumption of lamps with symplegma scenes. Evidently, then, the 3rd c. CE marks an important phase for lamps with sexual disc-reliefs. In the next section, I explore some of the possible reasons behind these radically different phenomena.

The third-century change

Historically, the last decades of the 2nd c. CE are marked by the death of Commodus in 193 and the end of the Antonine dynasty. Cities in decline (oppida labentia) and the weakening of the Empire's urban networks foreshadowed increased instability. Certain 3rd-c. CE insecurities were undoubtedly felt in all regions, affecting the strength and coherency of the Empire. Increases in security threats, along with pressures on the Imperial treasury and the administrative system, were just some of the problems that were affecting the nature of Imperial power and the familiar power dynamics.Footnote 68 The economic networks were affected by the monetary and fiscal changes and the administrative partition of the Imperial territories.Footnote 69 The consequences of these major adjustments meant that the regions located near the frontier profited economically from the military presence and trade with the communities residing outside the Imperial borders. The supersession in this period of Gallic by northern African workshops as the principal producer of ceramics provides a further sense of the shift in prosperity in the western provinces. Meanwhile, mainland Greece and the islands continue to endure economic decline, despite a resurgence of the Athenian lamp industry. The late 2nd c. CE also saw the emergence of Greek and Latin texts which debate sex and marriage and compare sex with women to sex with boys.Footnote 70 Greek romance novels are in fashion.Footnote 71 Positive attitudes towards abstinence from sex are present in both Christian and Stoic philosophy.Footnote 72 By the 3rd c. CE, the institutionalization of Christianity further amplified debates on the merits of sex and celibacy. Wall-paintings from the House of the Painted Vaults at Ostia suggest that the tradition of depicting sexual intercourse in art did survive into the Late Roman Empire.Footnote 73 However, as Clarke points out, both the state of the scholarship and a poor state of preservation hinder any meaningful assessment of the prevalence of sexual iconography in this later period.Footnote 74 Possible connections between socio-political shifts and changes in the provincial distribution and consumption of sexual disc-reliefs nonetheless deserve consideration.

The Late Roman Latin West underwent important political, religious, and economic changes that impacted both the urban and the rural topographies.Footnote 75 As in Italy, in the Latin-speaking provinces, the transition to Christianity was linked to attractive incentives encouraging the aristocracy to exchange their conventional civic and religious roles for prominent positions within the Christian community.Footnote 76 This also meant that the previous cultural conceptualizations of the “self” and the body were being reworked to correspond to the new structures and religious allegiance. The novel legal prohibitions and social restrictions challenged and altered traditional gender boundaries and power dynamics. Roman expressions of masculinity and femininity underwent change in the transitional period from polytheism to Christianity as the new religious morality favored sexual self-control and purity.Footnote 77 It is attractive to propose that the disappearance of lamps with sexual disc-reliefs from the Late Roman Latin regions was linked to these profound recastings of Roman sexual ideology.

Visual representations of sex, however, do not entirely vanish from the Latin West. Around the time when the sexual disc-reliefs decline, in the second quarter of the 2nd c. CE, the Rhône valley workshops begin producing wheel-made vases that frequently combined images of acrobatic sex and inscriptions of sexual puns.Footnote 78 This iconography, produced on appliqué medallions, has been understood as depictions of public sexual spectacles and as profane parodies of well-known festivals.Footnote 79 It is also possible that the vases with this elaborate iconography were used to commemorate specific holidays, such as the Saturnalia.Footnote 80 Whether the highly localized production and consumption of this material culture within the Rhône valley is linked to the increasing regionalism characteristic of this period may be up for debate. What is certain is that after the mid-2nd c. CE, at least in some Latin-speaking places such as Lyon and Vienne, images of sex remain in circulation.Footnote 81 In this later phase, however, iconography of sexual intercourse is unambiguously humorous in character and connected to objects that functioned as festival gifts or souvenirs.

The situation in the Greek East was different. From the 2nd c. CE, Greek culture was experiencing a resurgence, known as the Second Sophistic, that lasted well into the Late Empire.Footnote 82 This rebirth of Greekness was characterized by an axiomatic veneration of the 5th and 4th c. BCE Greek classics, which inspired newly produced literature, philosophy, sciences, and rhetoric. Greek identity was performed through civic service, intellectual achievement, and dedication to the traditional gods. The importance of non-Christian religious practices to this identity is attested by the steady flow of lamps with traditional mythological imagery produced by the workshops in Greece and Roman Asia as late as the 6th c. CE.Footnote 83 Although it is difficult to discern whether this imagery was involved in religious practices or appreciated for its aesthetic value, it is clear that despite the 4th-c. CE formalization of Christianity as a state religion and the growing Imperial restrictions on traditional religious activities, images of traditional gods continued to be in circulation in the Greek East.Footnote 84

The scholarship has successfully demonstrated the complexities of Greek self-placement and self-conceptualization during the Roman Empire.Footnote 85 Hall points out that the writers of the Second Sophistic revitalized the 5th-c. BCE debates on the virtue of culture and the meaning and nature of Hellenic identity.Footnote 86 These debates may also be viewed in the light of the foundation of the Panhellenion by Hadrian in 131–32 CE, with textual evidence suggesting that the criteria for admission necessitated demonstratable Hellenic descent.Footnote 87 Following the post-colonial interpretations, the increasing regionalism of the Empire, along with the development of a new sexual repertoire and its pan-regional distribution, especially in the context of the revival of the Greek past, raises a possibility of emerging forms of Hellenic-identity reaffirmation in the face of the Empire and increased instability from the late 2nd c. CE onwards.Footnote 88 The effects of interconnectivity and traveling objects and images on local iconographic innovation, however, cannot be overlooked. Iconographic elements were continuously transformed, adapted, or substituted, creating opportunities to produce novel representations of sex. What is important here is that by retaining the established visual structure of sexual disc-reliefs, the new Greek repertoire still shared characteristics with the sexual lamp-imagery in circulation during the Principate. The new Greek sexual disc-reliefs were locally innovative and were also linked by style and visual structure to the earlier sexual disc-reliefs. By using the universally available elements, this new Greek disc-art was also a part of a larger Roman sexual repertoire on lamps. The locally developed sexual repertoire thus also signals a process by which old schemas were adapted to new realities through the process of local cultural innovations. These locally innovative images also participated in the expression of the Greek-speaking urban population; their impact was in part located in their ability to change the dynamics of experience.

Conclusion

In this paper I aimed to demonstrate that the repetitive nature of disc-reliefs is a positive quality that can be used to statistically identify distributional and representational trends in lamp iconography. The sexual lamp-repertoire was not static and did not emerge in isolation. Rather, it came about as a part of a broader development of Roman sexual iconography and continued to change over time and across the Empire. While the numbers of sexual disc-reliefs are relatively low when compared to other types of lamp-imagery that were in circulation, the findings presented herein are robust and the data is valid. Lamps with sexual disc-reliefs have distinct regional styles of consumption and representation. These objects were differently received by diverse communities living in the Empire, and provincial communities show different predilections for certain images of sex on lamps. Although to some degree these patterns may be affected by the unbalanced state of scholarship and preservation, they must also reflect the tastes and choices of the provincial communities and the popularity of certain sexual subjects in the provincial lamp repertoire.Footnote 89 The trends presented here were a consequence of a host of social and Imperial factors that were both Empire-wide in scope and operating on a more local level. In a highly militarized environment such as Vindonissa, sexual disc-reliefs were primarily in circulation during the 1st c., when the overall consumption of lamps was prevalent, despite the ongoing cultural and economic exchange between the military and civilian population. In contrast, the 3rd-c. pan-regional distribution of the new sexual repertoire at the Greek-speaking sites may have had something to do with a reassertion of the Hellenic identity at the time. These divergent trends suggest that, across different locales, provincial communities selected, used, and innovated sexual disc-reliefs in order to participate and negotiate their places in an increasingly globalized Empire. In these new socio-political landscapes, lamps and their sexual art were active agents of identity expressions and cultural innovation.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1–8 contain cross-tabulated data produced by SPSS PAW v.22 software for the completed Chi-square analyses and Fisher's exact tests, and the questions against which they were produced. To view the Supplementary Materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759423000193.