It may not be with bullets, and it may not be with rockets and missiles, but it is a war, nonetheless. It is a war of ideology, it’s a war of ideas, it’s a war about our way of life. And it has to be fought with the same intensity, I think, and dedication as you would fight a shooting war.

Paul Weyrich founder of the American Legislative Exchange Council (Viguerie Reference Viguerie1981, 55)

For decades, human rights organizations have exposed egregious abuses carried out by states across the globe. Yet, at the same time, other national and transnational civil society actors have waged war on these human rights organizations in attempts to shield rights-abusive states from accountability. One contemporary manifestation of this phenomenon involved attacks by civil society actors such as NGO Monitor and UN Watch on local and transnational human rights organizations following the publication of five human rights reports accusing Israel of the crime of apartheid (Gehrke Reference Gehrke2022). Similar dynamics relating to abortion (Guns Reference Guns2013), LGBTQI+ (Rao Reference Rao2014), and migrant rights (Farris Reference Farris2017), to name just a few, have been part of the global landscape for some time now. In recent years, these assaults have increasingly resulted in the normative claims of human rights organizations being sidelined while rights-abusive laws and policies have gained further ground.

Despite these disturbing trends, and even as a vast amount of literature has investigated the ways in which human rights and humanitarian organizations help enhance human rights (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Risse, Ropp, and SikknikReference Risse, Ropp and Sikknik1999; Forsythe Reference Forsythe2000; Ramirez, et al Reference Ramirez, Meyer, Min Woptika and Drori2002), only limited scholarly attention has been paid to the contemporary civil society wars and to their influence on human rights (Bob Reference Bob2012, Reference Bob2019). This article seeks to begin filling in this gap by using Israel as its primary case study. I focus on Israel because, on one hand, it has been repeatedly criticized by numerous human rights groups for carrying out the crime of apartheid and other systemic violations (Falk and Tilley Reference Falk and Tilley2017; Al-Haq et al. 2019; B’Tselem 2021; Human Rights Watch 2021; Amnesty International 2022), and, on the other hand, it has been aided by a wide range of civil society actors who both criticize and frequently assault human rights advocates and their findings while also facilitating the violation of human rights (Chazan Reference Chazan2012; Waxman Reference Waxman2016; Jamal Reference Jamal2018; Lamarche Reference Lamarche2019; Pinson Reference Pinson2022).

Israel serves as a particularly conducive site for research on the attacks waged against human rights given the visibility of these attacks on mainstream media, social media, and the blog sphere; the intensity of the interaction between national and transnational civil society actors; the existence of concrete rights-abusive legislation, policies, and practices over which civil society actors have been sparring; and the accessibility of stakeholders in a field often inaccessible to researchers. Moreover, the Israeli case not only sheds light on how civil society actors shield, facilitate, reproduce, and reinforce a national hegemonic project that depends on the continuous and systematic violation of internationally recognized human rights but also Israel emulates and is emulated by countries like Hungary wishing to enhance illiberal policies that are directed at securing the domination of one ethnic group over others and is therefore an important case to study (Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018).

I should emphasize, however, that I do not intend to rehearse the different ways in which Palestinian rights have historically been and continue to be violated. Rather, building on previous research (Gordon Reference Gordon2014; Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015), I investigate the work of pro-Israeli civil society actors both in bolstering apartheid through a variety of mechanism while shielding the state from those who claim that the country is carrying out the crime of apartheid. I begin with a concise discussion of Gramsci’s conceptualization of civil society as a series of actors responsible for the production of consent toward the state’s hegemonic project, noting that in order to understand how hegemonic projects are sustained over time it is vital to examine the workings of civil society. I then turn to offer a brief overview of the history of the apartheid accusation waged against Israel from the 1960s until the publication of the five apartheid reports. After noting that the reports brush over civil society’s contribution to the crime of apartheid, I describe three strategies—native dispossession, lawfare, and advocacy—that civil society actors have used to enable apartheid. I document how these actors adopt liberal tactics to protect, reproduce, and enable apartheid and to attack human rights defenders, thus revealing how liberal procedures and processes can be used to enhance apartheid. By way of conclusion, I reexamine the adequacy of the dominant paradigm informing human rights work, which currently fails to include civil society actors as perpetrators of abuse, arguing that the paradigm needs to be extended to include these actors. Civil society actors, I argue, also need to be held accountable when perpetrating violations.

CIVIL SOCIETY AND THE STATE

A slew of articles in the late 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated how civil society organizations, which in the popular imagination had been associated with liberal democracy due to their emphasis on civic participation (De Tocqueville Reference Tocqueville2015), often advance illiberal agendas that end up weakening democracy and the kinds of rights it promises (Chambers and Kopstein Reference Chambers and Kopstein2001). As David Rieff (Reference Rieff1999) and others (Berman Reference Berman1997) have shown, civil society actors have always been pivotal in projects that exclude certain social groups in the name of the “public.” Carothers and Barndt (Reference Carothers and Barndt1999, 20) consequently concluded that “civil society everywhere is a bewildering array of the good, the bad, and the outright bizarre.”

Given that civil society actors have distinct goals, some of which promote the expansion of rights and others that oppose those very same rights (Bob Reference Bob2019), it is not particularly surprising that there are intense rivalries between civil society organizations. Such rivalries, as historians have shown, are not a new phenomenon. For instance, after the establishment of abolitionist groups in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America, pro-slavery citizens wrote pamphlets (Newton Reference Newton1860), formed associations like the Blue Lodges (Phillips Reference Phillips2002), and used churches as platforms (Painter Reference Painter2001) to assist southern states in promoting the interests of slavery. In a similar vein, in the nineteenth-century UK civil society organizations were created—for example, the National League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage—to support antisuffragism (Harrison Reference Harrison2013). This history as well as the contemporary civil society wars surrounding gun rights, abortion, LGTQI+, public health, voter rights, policing and incarceration, and migrants underscore the complex relationship civil society actors have with each other and with the state. The rivalries suggest that although some civil society actors have, historically, operated in opposition to the state and/or to the violation of human rights, many others have played a central role in defending and aiding rights-abusive laws and policies. Notwithstanding this multifaceted history, scholars and practitioners, particularly those involved in human rights, frequently focus on the contribution of civil society to enhancing human rights and to the pursuit of freedom while eliding how civil society actors frequently do just the opposite.

In an effort to better understand the relationship between civil society actors and the state, scholars in the 1980s and 1990s (Adamson Reference Adamson1987; Buttigieg Reference Buttigieg1995; Cox Reference Cox1999) turned to the work of Antonio Gramsci who conceptualized civil society as part of the state itself, or, as he articulated it, the “state = civil society + political society,” where civil society is responsible for manufacturing consent, and political society is responsible for the coercive mechanisms of management and control (Reference Gramsci, Hoare and Smith1971, 253). Thus, for Gramsci, civil society is not an assemblage of autonomous actors distinguished from the state but signifies the realm where contesting ideas are produced and circulated and where intersubjective meanings informing people’s sense of reality are manufactured (see also Bobbio Reference Bobbio and Keane1988; Thomas Reference Thomas2009). Even as some civil society actors actively challenge the state’s hegemonic project, most civil society actors help solidify consent for the state’s project and thus help maintain the ruling group’s leadership and control (Buttigieg Reference Buttigieg1995).

This formulation provides an important starting point for theorizing the current civil society wars that we are witnessing across the globe, where human rights organizations critical of a state’s rights-abusive laws and policies are attacked by mostly neoconservative civil society actors. But although Gramsci interrogated civil society actors operating solely within the state—except perhaps his discussion of the rotary clubs, YMCA, and Free Masonry—(Gramsci Reference Gramsci, Hoare and Smith1971, 286), today many civil society actors operate on a transnational level. Several international relations (IR) scholars have invoked Gramsci to make sense of transnational civil society (Cox Reference Cox1983; Gill and Law Reference Gill and Law1989)—showing how transnational civil society actors help develop global governance—but other than Bob (Reference Bob2012, Reference Bob2019), little time has been spent either describing or providing any kind of systemic analytic frame for making sense of the current wars taking place among civil society actors or interrogating the effects these wars have on the work of human rights organizations themselves. Examining the work of a range of civil society actors directed at strengthening Israel’s hegemonic project as well as the reaction of some of these actors to the human rights reports accusing Israel of carrying out the crime of apartheid helps reveal some of the ways civil society actors more generally—beyond the Israeli context—contribute to systemic human rights violations.

ISRAEL AND THE APARTHEID ACCUSATION

In a 1965 policy paper written for the Palestine Liberation Organization, Fayez Sayegh (Reference Sayegh1965, 22) claimed that Zionism conceives itself in racial terms as a Jewish national movement, and this, he asserted, has led Israel to advance “racial self-segregation, racial exclusiveness, and racial supremacy.” A decade later, the United Nations General Assembly (1975) adopted Resolution 3379, characterizing Zionism as “a form of racism and racial discrimination.”Footnote 1 The denunciation was dramatic, leading to strong reactions from Israel’s allies, with the chief American United Nations delegate at the time, Daniel P. Moynihan, averring that the United States will “not acknowledge,” “will not abide by,” and will “never acquiesce” to “this infamous act” (Hofmann Reference Hofmann1975, 1).

The “Zionism is racism” charge undoubtedly hurt Israel’s reputation, but the accusation did not stick within the corridors of international power where Israel was still considered the only democracy in the Middle East. Nevertheless, Israel was determined to challenge the racist label and conditioned its participation in the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference upon the United Nations annulling the identification between Zionism and racism. The aspiration to initiate a peace process between Israelis and Palestinians and to reach a just solution based on land for peace pushed many member states to change their position and revoke Resolution 3379.Footnote 2

The Oslo peace process, which superseded the Madrid Conference, ultimately circumvented the local Palestinian leadership (Said Reference Said2007). Israel and the Palestinians signed the Oslo Accords in September 1993, but as the years passed, it became clear that the so-called peace process would not lead to a just solution (Gordon Reference Gordon2008). Consequently, during the 2001 Durban World Conference against Racism, Palestinian civil society launched a global antiapartheid campaign to end “Israel’s brand of apartheid” (Lennox Reference Lennox2009). Three years later, Palestinian and pro-Palestinian activists introduced Israeli Apartheid Week, organizing annual events across university campuses in Europe and North America, and then in 2005 about 170 Palestinian civil society organizations launched the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign inspired by the South African anti-Apartheid movement (Baconi Reference Baconi2021). These civil society initiatives sought to alter the lens through which the situation in Israel-Palestine was perceived in the international arena, from a conflict between two national movements to a settler colonial enterprise that had established an apartheid regime where one racial group dominates another.

This shift in perception began infiltrating United Nations bodies. Two years after the BDS campaign was launched, John Dugard (Reference Dugard2007, 3), the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Palestine, introduced the apartheid accusation within the United Nations, but he limited the charge to the areas that Israel had occupied in 1967, maintaining that “elements of the occupation constitute forms of colonialism and of apartheid.” This charge set the tone for many human rights bodies over the proceeding decade. As the years passed, numerous commentaries and articles making similar claims appeared in an array of media outlets, with some continuing to talk about apartheid in the occupied territories, others claiming that apartheid was “creeping” into Israel (Yiftachel Reference Yiftachel2009), and a few arguing that Israel was already a full-fledged apartheid regime (Abdelnour Reference Abdelnour2013). In 2011, the Russell Tribunal in Cape Town, an independent juridical panel of inquiry concluded that “Israel’s rule over the Palestinian people, wherever they reside, collectively amounts to a single integrated regime of apartheid” (Al-Haq 2011).

In 2017, this accusation was formalized in a United Nations report. Writing at the behest of the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, a small organ within the United Nations, Richard Falk, a professor of international law and a former UN rapporteur on human rights for the Palestinian Territories, and Virginia Tilley, a political scientist at the University of Southern Illinois, accused Israel of carrying out the crime of apartheid in all the territories under its control, and not just those occupied in 1967, while even extending the accusation to Palestinian refugees living in the diaspora (Falk and Tilley Reference Falk and Tilley2017). The authors used the 1973 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, which defines apartheid as “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.Footnote 3 They exposed how Israel has breached the Convention by putting in place a number of basic laws institutionalizing Israel’s regime of racial discrimination against the Palestinian people, and then showed how these laws provide the legal basis upon which Israel carries out policies and practices that entrench Israeli-Jewish domination over indigenous Palestinians. The report also discloses how Israel has been carrying out “inhumane acts” on a widespread or systematic basis against Palestinians due to their ethnic and racial grouping.Footnote 4

Given that NGOs and journalists have written literally millions of words about Israel’s violation of human rights over the years, the contribution made by the Falk and Tilley report—as well as the ones that followed—was not in uncovering the discrete kinds of abuses to which Palestinians have been subjected. If they had simply done this, the reports would have failed to satisfy the requirements set out by the Apartheid Convention itself. Although it is sufficient to demonstrate the breach of specific legal provisions to show that a human right had been violated, in order to establish that a country is carrying out the crime of apartheid one has to demonstrate that the racial manifestations of domination are institutional and systemic and that they are carried out with intention or purpose (Falk and Tilley Reference Falk and Tilley2017, 9). Falk and Tilley’s success in exposing the institutional and systemic nature of Israel’s policies toward Palestinians as well as their intentional character rendered their report a watershed while distinguishing it from previous human rights reports.

Following its publication, Falk and Tilley were lambasted and personally excoriated. NGO Monitor claimed that the “two authors have long histories of anti-Israel activity.” It described Falk as a “fringe 9/11 conspiracy theorist” and wrote that “Tilley has contributed articles to Electronic Intifada, a major online media outlet active in promoting antisemitism, extreme anti-Israel views, and propaganda” (NGO Monitor 2017, para. 2). Stephen Greenberg and Malcolm Hoenlein, the Chairman and CEO of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, exclaimed that “this latest outrage perpetrated against Israel by a UN body must not be allowed to stand,” and described Falk and Rima Khalaf, the executive director of the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, as “serial purveyors of anti-Israel calumnies who abuse their official UN positions to launch unjustified and outrageous attacks on Israel” (Sugarman Reference Sugarman2017, para. 8). In the UK, Richard Verber, Senior Vice President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, slammed the UN report, calling it “a shameful exercise in distortion, delegitimization and propaganda” (The Times of Israel 2017, para. 1).

Although the UN Secretary-General António Guterres renounced the report and instructed its removal from the United Nations website (The Times of Israel and AFP 2017), Falk and Tilley had already managed to spark a discussion in the face of what Rafeef Ziadah (Reference Ziadah2021, para. 11) later described as an “orchestrated silencing campaign, which attempts to foreclose debate before it even begins.” And indeed, two years later, a coalition of Palestinian organizations submitted a shadow report to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, laying out the charge that Israel was perpetrating the crime of apartheid (Al Haq et al. 2019), and by 2021 the human rights organizations B’Tselem (2021) and Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2021) had published reports echoing the same accusation, followed in 2022 by Amnesty International (henceforth, I refer to the five reports accusing Israel of carrying out the crime of apartheid as the “apartheid reports”).Footnote 5

These well-documented reportsFootnote 6 were also met with widespread opposition from an array of civil society actors. The tenor of all the attacks was, however, uncannily similar. NGO Monitor (2021a) blamed B’Tselem of using “anti-Semitic tropes” and euphemisms routinely marshalled by those who wish to destroy Israel. The American Jewish Committee (2021) noted that Human Rights Watch’s “arguments are baseless and sometimes border on antisemitism,” and The Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (2022, Flawed Report, para. 1) strongly rejected Amnesty International’s report stating that it had been informed by “biased antisemitic tropes.” These are just a few examples of the scores of attacks directed against these human rights groups by other civil society organizations located in Israel as well as North America and Europe. As with Falk and Tilley, in some instances, the reports’ authors rather than the human rights organizations were assailed. Shurat HaDin (2019) sued Omar Shakir, the author of the HRW apartheid report, claiming that he supports the Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions campaign. NGO Monitor (2021b) cast him as a terrorist sympathizer. The organization justified this charge by revealing that Shakir participated in an international conference hosted by Sabahattin Zaim University in Istanbul, whose organizers and sponsors are according to NGO Monitor “linked to various terror groups, including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine” (para. 2).

This brief overview reveals that as one group of civil society organizations accuses Israel of committing the crime of apartheid, another group claims the reports published by the first group are riddled with empirical flaws and that the organizations and people behind them are either anti-Semitic or terrorist sympathizers. The two accusations are actually different, with the latter being more generalizable due to the link it draws to the global “war on terrorism” and the former being more specific to the case study tying, as it does, the state of Israel to the Holocaust. Much can be said about these reactions to the apartheid reports, and I return to this when discussing the different ways civil society actors have enabled apartheid, but first it is important to briefly describe how civil society actors feature in the apartheid reports.

THE APARTHEID REPORTS AND CIVIL SOCIETY

All of the apartheid reports focus on the legislative and executive branches of government, highlighting the laws, policies, and practices that enable the domination of one group over another. A number of civil society actors that deal with Palestinian dispossession do, however, figure in the reports. Falk and Tilley, who spend time presenting the role of “private actors” in facilitating and bolstering apartheid, write,

The term apartheid is also used to describe racial discrimination where the main agent in imposing racial domination is the dominant racial group, whose members collectively generate the rules and norms that define race, enforce racial hierarchy and police racial boundaries. The primary enforcers of such systems are private, such as teachers, employers, real estate agents, loan officers and vigilante groups, but they also rely to varying degrees on administrative organs of the State, such as the police and a court system. It follows that maintaining these organs as compliant with the system becomes a core goal of private actors, because excluding dominated groups from meaningful voting rights that might alter that compliance is essential to maintaining the system. (Falk and Tilley Reference Falk and Tilley2017, 19–20).

“Social racism,” they conclude, “doubtless plays a vital role in apartheid regimes, by providing popular support for designing and preserving the system, and by using informal methods (treating people with hostility and suspicion) to intimidate and silence subordinated groups” (Falk and Tilley Reference Falk and Tilley2017, 20). Yet, after noting that “private actors” are the “main agent in imposing racial domination” and that they are the “primary enforcers of such a system,” they go on to explain why they do not focus or even analyze in any depth the contribution of private actors to the apartheid project. Social racism and institutionalized racism are interdependent, they claim, but the role of constitutional law distinguishes the two. Constitutional law can provide equal rights to the entire citizenry, the two authors explain, and when it does, the law offers an invaluable resource for people challenging discrimination at all levels of society. They accordingly intimate that because social racism would not amount to apartheid without the institutional dimension, they focus on discriminatory basic laws, regular laws, regulations, and policies adopted by the Israeli government. Much can be said about these claims and the limitations that come with the adoption of a legal lens when addressing social wrongs (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015), but here I will only underscore that the distinction between the social and institutional reproduces the distinction between civil society and the state and justifies the focus on the latter.

The four other reports follow their cue, and although the operations of a handful of civil society organizations are described in the reports—such as the work of the Jewish National Fund in expropriating Palestinian land or the settler NGO Ateret Cohanim in uprooting and dispossessing Palestinians in East Jerusalem—these organizations are not discussed in the recommendations as actors that should be held accountable.Footnote 7 Such civil society actors are presented more as auxiliaries rather than a central piece of the apartheid puzzle. Moreover, none of the reports mention civil society actors that deploy lawfare and advocacy, and therefore there is no discussion about their contribution to apartheid nor is there any demand that they be held accountable. So although the apartheid reports meticulously show the ways in which Israel’s governments have carried out the crime of apartheid through a series of laws and policies and even as they appear to be well aware that civil society actors play a role in enabling apartheid, they spend relatively little time describing and analyzing the contribution of civil society to the production, maintenance, and reinforcement of apartheid.

To be sure, the focus on laws, governmental policies, and practices reflects how international human rights law and associated conventions are formulated while also replicating and reinforcing the primary role ascribed to state sovereignty in international relations. Yet, international human rights law does leave room for interpretation, which could be used by human rights organizations to adopt a more holistic approach to the crime of apartheid, one that takes into account the role played by civil society. For instance, most of the crimes of apartheid as defined in Article 2 of the 1973 Convention refer to actions that could be associated with the government but are not necessarily government actions. Article 2 (d), for example, notes that the crime of apartheid also includes “Any measures including legislative measures, designed to divide the population along racial lines by the creation of separate reserves and ghettos for the members of a racial group or groups, the prohibition of mixed marriages among members of various racial groups, the expropriation of landed property belonging to a racial group or groups or to members thereof.”Footnote 8 As we will see below, the expropriation of Palestinian land is frequently carried out by civil society actors, and although I do not discuss it in this article mixed couples are monitored and at times punished by civil society actors (Gordon and Rottenberg Reference Gordon and Rottenberg2014). Even when human rights organizations document the operations of these civil society actors (which is relatively rare) they continue to demand accountability from the government and refrain from making similar demands from civil society actors even as the latter play a constitutive role in the perpetration of violations.

One of the reasons why rights groups focus on states is because human rights law identifies states as both the major perpetrators of violations and as the parties with an obligation to protect those whose human rights have been violated (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015). This approach, as feminists (for example, Bunch Reference Bunch1990) and critical legal scholars (for example, Jochnick Reference Jochnick1999) claimed in the 1990s, trapped human rights advocacy in a state-centric paradigm that ultimately blinkers human rights work. Scholars and activists consequently called on human rights organizations to broaden their purview beyond the state to include violations carried out by individuals and corporations and later by non-state armed groups. The assumptions informing these claims were that certain non-state actors can be major perpetrators of abuse, that some of these actors have inordinate power, and that therefore these actors need to be monitored and held accountable for their actions. Following these calls, human rights organizations began making demands on corporations, urging them to assume responsibility for human rights violations. For instance, Platform, a London-based NGO monitoring the oil and gas industry, has published reports accusing the Anglo-Dutch energy corporation Shell of paying government forces to attack, torture, and kill Nigerians living in the creeks and swamplands of the Niger Delta (Brock Reference Brock2011). Drawing on this earlier scholarship and relatively recent changes in the remit of human rights NGOs, I propose that we need to broaden the paradigm informing human rights work even further.

Although a significant body of literature has analyzed the role played by national and transnational civil societies actors in shaping the way human rights are practiced in domestic settings (Risse, Ropp and Sikknik Reference Risse, Ropp and Sikknik1999; Lohne Reference Lohne2019), scholars focusing on human rights have carried out relatively little research on the activities of civil society actors that fight against human rights NGOs and human rights defenders and how these actors contribute to the violation of internationally recognized human rights. Highlighting the operation of these civil society actors will not only advance a more balanced analytical framework but may also propel human rights NGOs to widen their own conceptual framework so as to include the rights-abusive activities of civil society actors in their analysis and recommendations.

CRIMES OF APARTHEID AND CIVIL SOCIETY

An investigation of the civil society actors that have facilitated and enhanced Israel’s crimes of apartheid reveals that some of the actors are based in Israel and others are based in North America and Europe. Their remit is extremely broad including streamlining education in a way that corresponds with the hegemonic project; enhancing state branding and cultural diplomacy so as to present Israel as a thriving liberal democracy; lobbying politicians, governments, and an array of public and private institutions; influencing public opinion through advocacy while also participating in the surveillance of different actors and social groups; taking part in land grabbing endeavors; suing activists, and, at times, even carrying out vigilante violence. Most of these actors have offices, an official charity status, paid staff, publications, websites, and a series of goals that they promote; a minority is made up of smaller and more informal groups of volunteers who launch social media campaigns or deploy violence in order to sow fear among Palestinians and their supporters (Friedman Reference Friedman2015). Although in a future project I intend to map the full spectrum of these actors and the networks they have created, an examination of some of the prominent modes of operation of pro-Israel civil society actors dealing with Palestinians accentuates three primary groups that center around a major strategy: those focusing on dispossession, those deploying lawfare, and those that use advocacy as their primary tool. In what follows, then, I briefly describe the operation of a number of actors in each group, showing how they bolster the apartheid regime.

Dispossession

Even before the state of Israel was established, Palestinians were dispossessed from their ancestral lands by Zionist organizations. Scholars have documented this chapter in the history of the Zionist movement, chronicling how three pre-state civil society actors—the World Zionist Organization (WZO), the Jewish National Fund (JNF), and the Jewish Agency—played a crucial role in preparing the grounds for the massive expropriation of land following the 1948 war. In Records of Dispossession: Palestinian Refugee Property and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, Michael Fischbach (Reference Fischbach2003) reveals not only the central role played by the JNF in grabbing Palestinian land but also that, at times, the JNF rather than the government was the motor force of dispossession. This becomes apparent when one examines the activity of Yosef Weitz, who served as the director of the JNF’s Land Development Division from 1932. In May 1948, Weitz proposed to the fledgling Israeli government that he be allowed to establish a “Transfer Committee” to investigate proactive ways in which Israel could prevent the return of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees to their villages (Fischbach Reference Fischbach2003, 12–13). Fischbach reports that although Weitz did not receive official cabinet approval to operate, he went ahead and formed the committee and in June and July 1948 instructed his JNF employees to destroy several abandoned Palestinian villages from the Gaza region in the south to Acre in the north. In this way, Fischbach concludes, the JNF set the stage for the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages and the expropriation of millions of dunam from their Palestinian owners (14).

Over the years, the JNF has continued to play a crucial role in Palestinian dispossession and in the institutionalization of segregation between Jews and Palestinians and has used its charity status in numerous countries around the globe to raise tax-free funds to accomplish its goals. It has, for example, collected hundreds of millions of dollars for planting forests—most recently in the Negev region—in order to prevent Palestinians from accessing their agricultural lands (Bishara Reference Bishara, Nadim and Sabbagh-Khoury2018). It has simultaneously created a subsidiary, Himanuta, to purchase Palestinian houses for Jewish settlers in occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank (Shezaf Reference Shezaf2021). As several historians have shown, one cannot really understand the dispossession of Palestinians within Israel’s 1948 borders and in the areas it occupied in 1967 without taking into account the central role played by the JNF (Morris Reference Morris1987; Pappe Reference Pappe2007). Crucially, the JNF has helped produce a certain common sense around different forms of Palestinian dispossession while also serving as a harbinger of several civil society organizations that set out to dispossess Palestinians. The apartheid reports, as noted, describe the JNF but do not treat it as an actor accountable to human rights law, and when they mention some of the other civil society groups that have played a role in the dispossession of Palestinians, they do so only in passing. Here I briefly describe two other prominent civil society actors—Regavim and El-Ad—that enhance dispossession and enable apartheid.

Regavim (Hebrew for “mounds of earth”) was established in 2005 following the evacuation of Jewish settlers from the Gaza Strip. According to its website, its goals is to “prevent illegal seizure of state land, and to protect the rule of law and clean government in matters pertaining to land-use policy in the State of Israel” (Regavim n.d., About Us). In other words, its mandate is to ensure that the government continue to fulfill a central component of the Zionist hegemonic project, including the “Judaization of land” (Falah Reference Falah1989; Cohen and Gordon Reference Cohen and Gordon2018). In a previous research project, Nicola Perugini and I (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015) showed how Regavim has adopted a series of strategies to help Judaize land including the ongoing surveillance of land, monitoring Palestinian development, and filing scores of petitions to Israel’s High Court of Justice and other courts so that they, in turn, will instruct the executive branch to evict Palestinians from their lands or demolish their homes.

Significantly, in its High Court petitions the organization uses liberal law enforcement arguments and strategies to evict Palestinians from land. In some instances, Regavim rides on existing eviction orders that had already been issued by the Court against Palestinians. Monitoring which of these orders is still pending, it petitions the Court, asking that it instruct the Israeli government to implement the Court’s orders. The cases are constructed with the help of Regavim’s “area managers” who monitor—through, inter alia, aerial photos and satellite technology—Palestinian development across space (Perugini and Gordon Reference Perugini and Gordon2015). At the time of writing, Regavim had just filed a petition asking the High Court to instruct the government to evict close to 200 hundred Bedouin residents of Khan al-Ahmar, located a few kilometers east of Jerusalem, to make room for the expansion of a nearby Jewish settlement, thus making it easier for Israel to annex the area (Dokov Reference Dokov2022). In other circumstances, Regavim does not build on pending legal orders but submits its own petitions for demolitions and law enforcement. In these cases, liberal law is also the primary instrument. In a 2018 petition submitted to the High Court of Justice against the Israel Land Authority, Regavim successfully argued that the Authority must evict Palestinians and demolish the structures they had built on state land adjacent to the village Romat Al Hayb located in Israel’s northern district.Footnote 9 According to its website, in 2022 it submitted 19 petitions of this kind (Regavim 2022).

Another civil society organization heavily involved in the dispossession of Palestinians is El-Ad, a name formed from Hebrew letters that stand for “to the City of David.” In 1998, the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority and the Jerusalem Municipality hired El-Ad as a subcontractor to run “The City of David,” a national park located in Silwan, a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem. The park is located in occupied East Jerusalem and encompasses nearly all of the Wadi Hilwa neighborhood in Silwan, south of the Old City walls. Wadi Hilwa is home to approximately 4,000 Palestinian residents who live in more than 700 residential units in over 250 buildings (B’Tselem 2014). After receiving government funding and a permit to carry out archaeological excavations in the area, El-Ad outsourced that work to a governmental agency, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and began using archaeology to uproot Palestinians from the East Jerusalem neighborhood (Emek Shaveh Reference Shaveh2013a).

Raising millions of dollars primarily, from donors in North America (Blau and Hasson Reference Blau and Hasson2016), El-Ad’s objective is to excavate Jewish heritage in East Jerusalem (ignoring for example layers that reveal hundreds of years of Muslim rule) through seemingly benign archaeological practices that seek to strengthen “the Jewish bond to Jerusalem” (Guidestar 2022). In this way, this civil society organization not only erases Palestinian history but also deploys archaeology and preservation to dramatically restrict the development needs of the neighborhood’s indigenous Palestinian population (Emek Shaveh Reference Shaveh2013b; for an analysis of Israel’s use of archaeology to advance settler colonialism, see El-Haj Reference El-Haj2008). And although it introduces these restrictions, together with other civil society organizations it has arranged for 60 Jewish settler families, totaling some 300 individuals, to move into the neighborhood (B’Tselem 2014). Even this brief description of the City of David archaeological site that was created by El-Ad with the help of the Antiquities Authority in the very heart of a Palestinian neighborhood reveals the multilayered relations between civil society actors and government agencies, where the workings of one arm cannot really be understood without taking into account the operation of the other arm. By so doing it underscores just how limited the human rights lens of center-staging government actors is while simultaneously laying bare how dispossession can be carried out by designating an area as a national park and by using preservation requirements.

Due to lack of space, I cannot delve deeper into the different ways civil society organizations operate to dispossess Palestinians. I will note, however, that the Gramscian distinction between civil society that is responsible for persuasion and manufacturing consent and political society or government that is responsible for the coercive elements of the state does not appear to capture the full spectrum of the operations carried out by civil society. The case study suggests that the distribution of labor between civil society and political society is much more complex and, probably even more importantly, that the distinction between persuasion and coercion is often artificial and does not reflect the reality on the ground where the two are operationalized at the same time and often by the same actor. Before returning to this observation, I turn to examine the two other forms of intervention carried out by civil society organizations.

Lawfare

A bird’s eye of the civil society actors defending Israel from the apartheid accusation reveals that a number of organizations have adopted direct litigation as their preferred method. These organizations have become experts in lawfare, a term that combines the words law and warfare and is defined as the use of law for realizing military objectives. Originally lawfare was used to describe the use of universal jurisdiction to file suits against western military officers by alleging that their forces had wrongfully killed civilians during military operations (Dunlap Reference Dunlap2008). In the context of Israel/Palestine the term has been deployed by Israel and its allies to criticize organizations and individuals that submit petitions primarily in European courts against generals or politicians who allegedly committed war crimes or crimes against humanity against Palestinians (Dunlap Reference Dunlap2009).

In the past several years, however, civil society organizations are using a similar strategy by suing Israel’s critics in national courts, ranging from human rights organizations and their staff through cultural influencers to grassroots antiapartheid activists. UK Lawyers for Israel, the International Legal Forum, the Zionist Advocacy Center, and Shurat HaDin are among the prominent civil society actors who have deployed direct litigation to protect Israel. Below I describe the operations of one of these actors. However, before I do, it is important to note that I use lawfare to denote an additional (if related) phenomenon from the one discussed in the literature—namely, as a heuristic term to describe civil society actors’ attempt to introduce new laws directed at delegitimizing basic human rights or forms of mobilization against human rights violations. One actor at the forefront of this form of lawfare is the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019), which, among its many endeavors, has taken upon itself to introduce a slew of laws in the United States that shield Israel from Palestinian-led efforts to mobilize against the crime of apartheid (The Center for Constitutional Rights et al. 2021). ALEC is particularly interesting in the context of this study since it is a US-based organization without apparent ties to Israel and thus helps expose the kind of transnational networks civil society wars help constitute.Footnote 10

Founded in 1973 by Paul Weyrich (whom I quote at the beginning of this article) and two other conservative politicians, ALEC claims that it is currently “America’s largest nonpartisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators dedicated to the principles of limited government, free markets and federalism” (ALEC n.d., About ALEC). Indeed, over the years it has become a “highly effective incubator and platform for spreading a broad swath of corporate and conservative policies,” boasting a membership of up to a third of all state legislators and several hundred corporations (The Center for Constitutional Rights et al. 2021, 6). Using its platform, ALEC circulates prefabricated draft laws among its lawmakers who commit to advancing the draft laws within state legislatures across the country. The laws it advances, as Alexander Hertel-Fernandez (Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019) points out, can be roughly divided into two kinds: laws that promote corporate interests, often by enhancing deregulation and corporate profit, and laws that foster a conservative agenda, such as pro-life legislation and voter ID laws. The first kind of laws help fund the second kind, as ALEC’s corporate members pay considerable dues to the organization in order to ensure that ALEC lawmakers put forward the legislation in which they have a vested interest. In a sense, ALEC sells state lawmakers to corporations, and this enables it to fund social issues laws. As a coalition of civil society groups explains in a December 2021 report called Alec Attacks: “where ALEC saw a new and much needed revenue stream, corporate executives across the country saw an untapped network of political influence” (The Center for Constitutional Rights et al. 2021, 12).Footnote 11

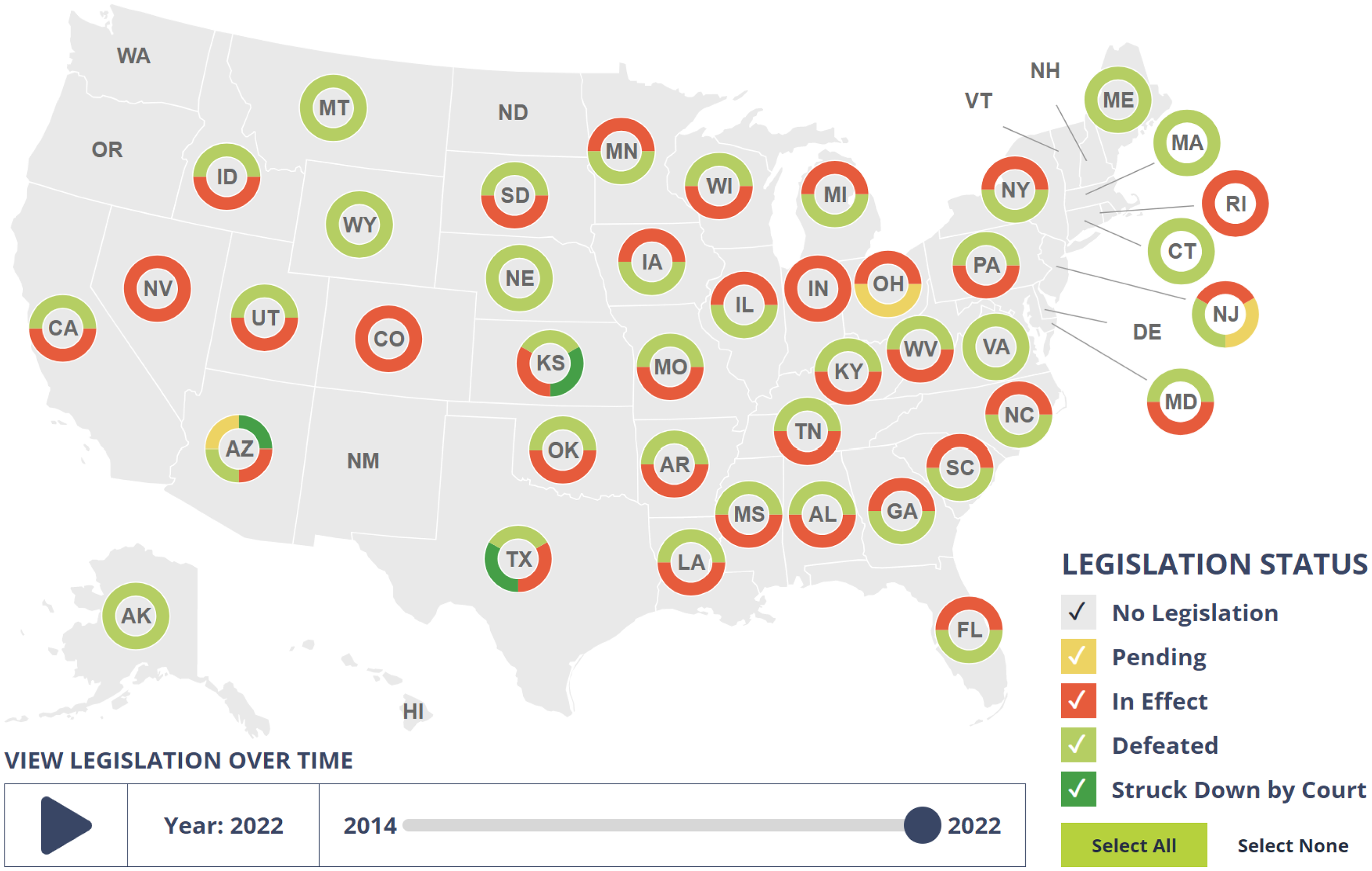

ALEC joined the effort to protect Israel from antiapartheid mobilization—particularly the call of 170 Palestinian civil society organizations to use boycott, divestment, and sanctions in order to pressure Israel to end its brand of apartheidFootnote 12 —due to its right-wing evangelical commitments. Its involvement appears to have begun in 2014 when the Jewish United Fund, a civil society organization that describes itself as “one of the largest humanitarian organizations in the [United States]” started working closely with lawmakers in Illinois to introduce legislation that would render it illegal to support BDS (Jewish United Fund n.d.). The idea to introduce such legislation emerged from the Israeli government following the growing appeal of the BDS movement on campuses and among civil society organizations in the US and Europe and its conception within Israel as an existential threat to the regime (White Reference White2020).Footnote 13 ALEC initially joined The Jewish United Fund, but not long after took the reins and led the efforts across the US. If in May 2015, the Illinois state legislature unanimously passed the first state law that explicitly punishes those who advocate BDS in support of Palestinian rights, by December ALEC introduced two anti-BDS measures as potential model legislation at the annual ALEC summit it organizes for its lawmakers.Footnote 14 Since then, 260 (copy paste) bills targeting boycotts and advocacy of Palestinian rights have been introduced across the United States. Twenty-three percent have successfully passed, which means that 34 states now have anti-BDS legislation in effect (see Figure 1).

The goal of these anti-BDS laws is to prevent civil society groups and individuals from expressing solidarity with Palestinians living under apartheid as well as to punish activists, civil society organizations, and corporate actors that actively support the antiapartheid campaign. Significantly some of the processes leading to the legislation of these bills can be taken out of a liberal democracy textbook about the ways citizens can participate in influencing political decisions that affect their lives.Footnote 15 What we witness here, however, is how a foreign government (Israel) influences the agenda of an American civil society group and how corporate funding is then used to enhance the agenda of this foreign country.Footnote 16

While one group of actors introduces legislation that prevents nonviolent forms of activism—adopted and developed by Palestinian civil society organizations—against apartheid, another group of actors sues individuals and organizations that are actively engaged against the systemic violation of Palestinian rights. These actors have developed an arsenal of legal strategies, using “soft law” such as complaints to regulatory bodies as well as strategic lawsuits against public participation and tort claims. Their targets include Human Rights Watch, Oxfam, Christian Aid, the New Israel Fund, and the Carter Center (to name a few), as well as human rights defenders and other social justice activists.

A primary actor in this group is Shurat HaDin: Israel Law Center, which describes itself in the following manner: “We are dedicated to protecting the State of Israel. By defending against lawfare suits, fighting academic and economic boycotts, and challenging those who seek to delegitimize the Jewish State, Shurat HaDin is utilizing court systems around the world to go on the legal offensive against Israel’s enemies” (Shurat HaDin n.d., About Us). Putting to test a new Israeli antiboycott law after New Zealand singer Lorde cancelled an announced Tel Aviv performance, Shurat HaDin successfully sued two antiapartheid activists in an Israeli court because they had published an open letter urging Lorde to heed the Palestinian call to boycott Israel (Abu-Shanab Reference Abu-Shanab and Sachs2017; Shurat HaDin 2018). The organization also won a High Court of Justice appeal against Human Rights Watch researcher Omar Shakir, in which it asked the government to revoke his working visa due to his prior support for the Palestinian Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign (Shurat HaDin 2019a). Following the ruling, Shurat HaDin’s founder Nitsana Darshan-Leitner stated that “Shakir is the one who pushed Airbnb to delist the Jewish homes in the [West Bank] and even took pride in having the hosting platform comply with his dictates. Now that the High Court has ruled Omar Shakir is grossly biased, HRW has now [sic] lost all its credibility in the Israeli–Arab conflict. They ought to shut down their offices here and stay out of this region” (2019a, para. 4).

Shurat HaDin (2019b) also regularly operates outside of Israel and succeeded in closing the Jewish Voice for Just Peace in the Middle East’s account with the German Bank für Sozialwirtschaft in Cologne Germany after warning the bank that its association with “the radical anti-Israel Jewish Voice for Peace in the United States, as well as an integral part of the anti-Semitic BDS movement” (para. 2) exposed its officers to potential criminal and civil liability under the United States Antiterrorism Act. In a similar vein, the organization filed a legal complaint with the IRS against the Presbyterian Church USA seeking to revoke the Church’s tax-free status because it supports the Palestinian BDS movement and had divested $21 million worth of shares from corporations complicit in Israeli human rights violations, such as in Caterpillar, Hewlett-Packard, and Motorola Solutions (Shurat HaDin 2014).

Both examples—legislating bills and filing lawsuits—offer instances of civil society actors marshalling liberal law to help shield a regime which the most prominent human rights organizations across the globe have accused of carrying out the crime of apartheid. They highlight the interdependency between the rights-abusive laws and government policies, on one hand, and the workings of civil society, on the other. Consequently, any attempt to explain Israeli apartheid and to outline those responsible for human rights abuses without investigating the contribution of civil society actors is necessarily blinkered.

Advocacy

If JNF and Regavim enable Israeli apartheid through the dispossession of Palestinian land and the creation of Jewish-only settlements, ALEC, through the mobilization of state legislatures, introduces laws that shield Israel from BDS and Shurat HaDin files lawsuits against Israel’s critics, all in order to buttress the country’s hegemonic project. Alongside these actors, there is an assemblage of other civil society organizations that have taken upon themselves the role of shielding Israel from the apartheid charge by framing those who make it as anti-Semites, terrorists or people harboring such critics. Their targets include Palestinian farmers, human rights NGOs, university staff and students in Israel, the Palestinian territories and abroad, private and governmental donors, news outlets and social media platforms, politicians, public intellectuals and grassroots activists, civil society actors, and an array of cultural influencers—from pop singers and movie stars to super models. This is by far the largest group of apartheid enablers, with scores of organizations dispersed primarily in Israel, North America, and Europe.Footnote 17 Their objective is to produce a chill effect and ultimately delegitimize those who are harshly critical of Israel in order to sustain and (re)produce Israel’s image as a liberal democracy. And while they target governments, news networks, and, more recently, corporations such as Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream and media platforms like Facebook, the vast majority of their targets are themselves civil society actors, cultural influencers, and grassroots activists who support the Palestinian struggle for self-determination.

This cluster of advocacy actors includes organizations such as NGO Monitor, Im Tirzu, Board of Deputies of British Jews, UN Watch, Stand With US, and the Anti-Defamation Leagues (to name a few). Here I focus on NGO Monitor, outlining its threefold strategy: which begins with surveying, mapping out, and monitoring the major actors supporting Palestinian liberation; then moves to frame these actors as associating with terrorists and/or as anti-Semitic; and, finally, it targets donors and policy makers, urging them to stop the supply line or be outed as funding “terrorists” and “anti-Semites.” In this way it helps define and police the borders of legitimate debate about Israel, names and punishes anyone who transgresses these borders, and sows fear among those who might consider transgressing.

After mapping the civil society field, NGO Monitor creates portfolios of human rights and other organizations critical of Israel, which it then publishes as reports and passes on to an array of governmental bodies, donors, and other pro-Israel civil society actors both in Israel and abroad. Currently it has portfolios of 228 civil society actors on its website (NGO Monitor n.d. a), 32 private funders like Christian Aid and Open Society Foundation (NGO Monitor n.d. b), alongside 20 government funders including the different agencies within each country that fund the suspected actors (NGO Monitor n.d. c). In the portfolios, NGO Monitor scrutinizes each organization’s publications, donors and in several cases (particularly with respect to Palestinian organizations) it monitors the organization’s staff members primarily by mining social media activities on Facebook, twitter, and other platforms and by examining whether they were indicted by the Israeli military court (whose conviction rate is 99 percent). A military court conviction or Facebook post are sufficient to render, in NGO Monitor’s eyes, staff members of Palestinian civil society organizations terrorists or terrorist sympathizers and is then used to delegitimize both the person and the organization he or she work for.

This is the strategy NGO Monitor (2022c) used when creating portfolios of six Palestinian civil society organizations that were later designated by the Israeli government as terrorist organizations despite criticism voiced by several EU governments and the Biden Administration that the proof provided against these organizations did not stand up to scrutiny (Government of the Netherlands 2022). It is important to note that these six civil society actors are either human rights organizations that channel information to the outside world about violations taking place in the West Bank or humanitarian organizations that help Palestinians retain their lands. In other words, the effort to delegitimize these actors can be understood as an effort to delegitimize nonviolent resistance to Israeli rule.

Elsewhere I have analyzed NGO Monitor’s work showing how the organization uses textbook democratic practices—such as raising issues in the public sphere and lobbying legislators and decision makers—to brand local and transnational human rights organizations as a national threat that needs to be restrained (Gordon Reference Gordon2014). I also showed how the construction of human rights as a security threat has been carried out not in order to reject human rights tout court but in order to curb what neoconservative groups define as a particular “political” application of human rights.

Although my previous study focused on how NGO Monitor and other organizations harnessed “the war on terrorism” discourse to brand human rights activists as terrorists and terrorist sympathizers, in the past few years there has been similar emphasis on antisemitism primarily following the 2016 adoption of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance “working definition of antisemitism,” which equates forms of anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism (Jewish Voices for Peace 2017). As numerous commentators and organizations have claimed, this definition has become a tool of choice for so-called pro-Israel organizations because it shifts the meaning of anti-Semitism from its traditional focus on hatred of Jews per se—the idea that Jews are naturally inferior and/or evil, or a belief in worldwide Jewish-led conspiracies or Jewish control of capitalism, or some combination thereof—to one based largely and, it seems, most importantly, on how critical one is toward Israel’s apartheid regime (Gould Reference Gould2020). The definition provides eleven examples of contemporary manifestations of anti-Semitism, seven of which refer to the State of Israel, thus rendering critique of the state as potentially anti-Semitic. One example of anti-Semitism is the claim “that the existence of the State of Israel is a racist endeavor” (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance n.d., § 2, bullet 7), and another involves the requirement that Israel behave in a way “not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation” (§ 2, bullet 8). Debating whether Israel, as a self-proclaimed Jewish state, is “a racist endeavor” or a “democratic nation” can be sufficient evidence to brand a person or a civil society organization an anti-Semite.

In a July 2022 report (NGO Monitor 2022b) entitled “Al-Haq’s Antisemitic Submission to the UN’s Permanent COI,” NGO Monitor writes that the “Palestinian NGO Al-Haq, along with 90 cosignatories, submitted a flagrantly antisemitic report to the UN Human Rights Council UNHRC’s permanent ‘Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and in Israel’ (COI).” The submission, NGO Monitor continues, “presents a blatantly false historical account, denying Israel’s right to exist and denying the Jewish people their right to sovereign equality. In this respect, Al-Haq and the other NGOs contravene the IHRA Working Definition of Antisemitism, specifically its identification of ‘Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor’ as antisemitic” (NGO Monitor 2022b, 1).

After chronicling which of the signatories of this submission has received EU funding, NGO Monitor provides a series of quotes from the report submitted by the Palestinian human rights organization as examples of antisemitism. These include

-

“The 1948 Territory refers to the territory of the settler-colonial State of Israel, established by the displacement and dispossession of the vast majority (around 80 percent) of the indigenous Palestinian people during the Nakba and the maintenance of a settler colonial and apartheid regime over the Palestinian people since its creation.”

-

“The Palestinian people argued that the incorporation of the Balfour Declaration was illegal.”

-

“The partition of Palestine, as it stood at that time, violated sacrosanct principles of international law” (NGO Monitor 2022b, emphasis in the original).

These quotes are meant to convince the reader that Al Haq is anti-Semitic because it depicts Israel as an “inherently illegal enterprise,” which according to the IHRA definition can be construed as anti-Semitic (NGO Monitor 2022b). A similar strategy was adopted by NGO Monitor after the publication of the apartheid reports. Under the heading Amnesty International it writes, “Amnesty is a leader of a network of NGOs that promote artificial and manufactured definitions of apartheid to extend the ongoing campaigns that seek to delegitimize and demonize Israel” (NGO Monitor 2022a). In an April 2022 report titled “Amnesty International’s Cruel Assault on Israel: Systematic Lies, Errors, Omissions & Double Standards,” NGO Monitor writes that Amnesty “liberally uses the term ‘Jewish domination’ to refer to Israel’s policies (in fact ‘domination’ appears in the report subtitle which is then copied on every page of the report), a concept, which along with charges of wholesale theft of land and property, that directly evokes antisemitic tropes of Jews seeking to wield power over others” (Aizenberg Reference Aizenberg2022, 5).

Similar accusations of anti-Semitism have also been harnessed against Human Rights Watch, B’Tselem and numerous other actors. Once a report about a civil society organization is published—ostensibly documenting its association with terrorists or its “anti-Semitic” tendencies—NGO Monitor proceeds to send it to government officials, journalists, and donors. NGO Monitor regularly lobby’s politicians in both Israel and the EU, demanding, among other things, that they defund the pro-Palestine civil society organizations. Meanwhile, UK Lawyers for Israel has used allegations of terrorism and antisemitism brought forth by NGO Monitor against specific Palestinian and pro-Palestinian civil society actors to call on banks and funding platforms—like PayPal and BT’s My Donate—to deplatform the organizations.Footnote 18 Cases in point include UK Lawyers for Israel’s (UKLFI) initial success in preventing Defense for Children International Palestine (DCI-P) from receiving foreign currency donations by bank transfers from Citibank and Arab Bank PLC, and its campaign to discontinue the ability of UK Charity War on Want from receiving donations through PayPal (UKLFI 2018a, 2018b).

These strategies are extremely effective, as once those who support the Palestinian demand for self-determination are accused of being terrorists and/or antisemites, they are forced to spend considerable time and resources defending themselves and their organizations rather than concentrating all of their resources on the antiapartheid struggle. One human rights lawyer told me that if once 90 percent of the files in his office were dedicated to violations perpetrated by Israeli authorities, currently 40 percent of the files involve human rights defenders who have been accused by civil society groups of anti-Semitism or terrorism.Footnote 19 The message is clear: if you join the antiapartheid camp, you will be targeted, cast as enemy, and framed as illegitimate, and you will have to spend considerable time and resources defending yourself.

CONCLUSION

This cursory description begins to lay bare the increasingly complex role local and transnational civil society networks play in bolstering domestic hegemonic projects that violate human rights. Although a more in-depth investigation is needed to map the field, make sense of the multifaceted relations within it and understand the gamut of strategies that are deployed as well as their specific objectives, a few conclusions can already be drawn from the analysis. Some of these are specific to the case study, whereas others appear to have more general implications. In the remaining space, I briefly highlight three observations, the first relating to liberalism, the second to the consent/coercion bifurcation, and the third involves the human rights lens.

First, one aspect of these wars that is particularly fascinating—and transcends the Israeli case—is that liberalism is the ultimate reference point used by both sides of Israel’s civil society wars. Indeed, both camps are invested in situating Israel in relation to a liberal imagination. The pro-Palestinian and human rights organizations seek to show that Israel is not a liberal regime, whereas the pro-Israel camp that champions the domination of one racial group over another is invested in portraying the regime as a liberal democracy, albeit a Jewish one; the latter’s objective is to ensure that Israel will continue to be imagined as a liberal regime and one of the ways this goal is achieved is by presenting Israel’s critics as illiberal: anti-Semites, terrorists, or sympathizers of these groups. Moreover, the case study reveals how liberal strategies can be and have been used to enhance and shield an illiberal apartheid regime.Footnote 20

There is, however, another move that has received less scholarly attention—namely, the effort of civil society actors to undo the distinction between apartheid and liberalism by defending and helping to produce the image of (apartheid) Israel as liberal. Put differently, the struggle between the two camps can be framed as a struggle over the character and meaning of democracy, where the pro-Israel actors lay claim to a form of liberal democracy that permits one ethnic group to dominate other ethnic groups. The fascination with the liberal/racial domination conjuncture is surely not unique to Israel and can be identified in numerous countries across the globe. Indeed, more research needs to be carried out about the production of this conjuncture and the kinds of relations it helps cement between, on one hand, governments, politicians, and journalists who are captivated by and invested in this ideological formation particularly in light of the increasing movement of refugee populations across political borders and, on the other hand, civil society actors that help produce, circulate, and shield this ideological formation with the objective of legitimizing a form of democracy in which one ethnic, racial, or religious group dominates other groups.

Second, and as mentioned above, the analysis of civil society organizations problematizes Gramsci’s distinction between coercion and persuasion and the distribution of labor within the state, where certain actors are responsible for coercion and others for manufacturing consent. Civil society, Gramsci (Reference Gramsci, Hoare and Smith1971, 242) wrote in the Notebooks, “operates without ‘sanctions’ or compulsory ‘obligations’, but nevertheless exerts a collective pressure and obtains objective results in the form of an evolution of customs, ways of thinking and acting, morality, etc.”Footnote 21 Although the role of civil society is certainly to bolster the hegemonic project by modifying people’s habits, will, and convictions to conform with the directives and objectives set forth by the project (Gramsci Reference Gramsci, Hoare and Smith1971, 266), such actors, as the above analysis documents, also take part in the employment of sanctions and compulsory obligations to bolster the hegemonic project—as when they dispossess Palestinians or convince funding platforms to remove pro-Palestinian organizations.

At the same time, the case study highlights and seems to corroborate Gramsci’s claim that hegemony—understood following Peter Thomas (Reference Thomas2009) as a political strategy—is exercised over allied groups and domination over political adversaries and that this duality is often sustained within a single state. This is directly connected to the notion of a liberal apartheid regime espoused by the civil society organizations and an array of governments, where certain groups within a given state are managed by manufacturing consent through the allocation of rights and privileges and other groups are managed and controlled primarily through coercion and forms of domination. The above analysis contributes to this insight by highlighting that civil society actors play a prominent role not only in producing consent but also in enabling the domination of the adversary groups.

All of this leads directly to my third claim, the one I have gestured to throughout this article—namely, that if human rights organizations are interested in the processes that lead to violations and the actors responsible for the abuses, they need to expand their remit and to begin investigating the contribution of civil society actors to the perpetuation of social wrongs. When human rights groups assess and decry social wrongs, they focus almost exclusively on rights-abusive laws, policies, and practices adopted and promulgated by the state’s legislative and executive branches, yet they fail to consider the contribution of civil society actors to human rights abuses. Shedding light on the ever increasing role civil society actors play in the twenty-first century and the mechanisms they deploy in enabling state crimes—such as native dispossession, lawfare, and advocacy—not only adds an important dimension to the conceptual frame for understanding how states get away with egregious violations—one currently missing in the critical literature on the efficacy of human rights (Douzinas Reference Douzinas2007; Hopgood Reference Hopgood2013)—but also offers a much more complex understanding of the processes that facilitate systemic human rights violations, which is a necessary step in actually addressing and redressing these wrongs. Put differently, one cannot really understand how Israeli apartheid ticks without taking into account the contribution of civil society actors, which would necessarily include interrogating the local and transnational networks they create, the different strategies they deploy, and the specific (antisemitic branding) versus general (terrorist branding) accusations they level against human rights defenders. If the goal of human rights organizations is to challenge systemic and institutional forms of abuse, that are also considered crimes against humanity, then they need to investigate this group of apartheid enablers and demand that they too be held accountable. By extending the way we think about the identity of perpetrators and targets of abuse, this new conceptual frame can potentially change the dominant conception of what counts as a violation as well as strategies that lead to violations, thus transforming our conception of accountability and how we can be more effective in holding actors accountable.