Before World War II, Jaromír Weinberger's Schwanda the Bagpiper (1927) was the most widely known Czech opera after Smetana's Prodaná nevěsta (The Bartered Bride, 1866).Footnote 1 It rapidly achieved great success and was performed throughout the world. Although popular, the opera was also controversial, and triggered debates at its world premiere in interwar Prague, where critics judged the work an epigone, and a musical reminiscence of bygone times that hindered the development of modernism in Czech music. This mixed reception recurred at the century's end, when the Walt Disney Company considered a sequence from the opera for the movie Fantasia 2000, but ultimately rejected it. Since 1945, Schwanda the Bagpiper has rarely and only reluctantly been performed (save for its famous polka and fugue, which the composer extracted from the score and reorchestrated for concert performance).Footnote 2 Recently, revivals of the opera were planned as part of a Weinberger Festival at the Komische Oper Berlin and in a new production at the Národní divadlo in Prague, both in early 2020. Although the COVID-19 pandemic brought these efforts to a sudden halt, in March 2022 Schwanda finally made it onto the Berlin stage in a stellar, refreshing production that I experienced a few weeks after the premiere. It brought to the fore the dialectics of nationalism inherent in the work – continuity and discontinuity, homogeneity and plurality, unity and division. The press celebrated it as a ‘late rediscovery’.Footnote 3

Schwanda had a unique trajectory: its creation during the first half of the interwar years and its complex reception during the second half were affected by the transformation of notions of nationalism in Europe. It became entangled in the nascent Czechoslovakia's musical identity politics, which deeply affected opera during this transitional time. The aesthetics of the generation then coming of age began to waver between the conflicting ideologies of Czech nationalism and international modernism, French cultural influences and conservatism.Footnote 4 This oscillation led to a growing crisis in operatic aesthetics, especially in the capital Prague, throughout the mid-1920s. Fierce contemporary debates, in which critics and composers showed their true colours, reflected the political tensions between conservatism and modernist reorientation, an anxiety about loss of national distinction, and an openness to international modernism.Footnote 5 Furthermore, Schwanda occupied a doubly difficult position because of Weinberger's Jewish heritage: it was caught in the currents of anti-Semitism.

Even so, for acculturated Jews like Weinberger the interwar period – wedged between the oppressions of pre-World War I and the rise of Nazism – became a precious time. If Eastern Europe's Jews were faced with chauvinism and intolerance, socioeconomic instability, economic stagnation and right-wing politics, Czechoslovakia's government remained an exception in the region with its politics largely moderate, liberal and democratic, although not without ambivalence about Jews.Footnote 6 And not entirely without complexities, as the Czech-Jewish movement continued to confront Zionism and vice versa, and both faced popular anti-Semitism under a government that tried to fight it.Footnote 7

More than any other work, Schwanda the Bagpiper, in its gestation and reception (with failure and success), reflects the transitional and complex state of the arts in the young republic during the interwar period, and the status of Jews therein caught between the Czech and German populations and their distinct nationalisms, as well as between anti-Semitism and Zionism.Footnote 8 Ezra Mendelsohn captures the intricate relationship as follows: ‘Even in Prague, where there was a strong German liberal tradition warmly supported by the Jewish population, relations between Jews and Germans were far from being close – [by 1933] the relationship is described by Brod as being one of Distanzliebe.’Footnote 9 During these crucial years, adopting the national identity of the majority became pertinent again for many Jews.Footnote 10 That Weinberger devoted himself to a musical nationalism that builds on the foundation of nineteenth-century Czech operatic culture reflects this Zeitgeist. But more than that, the plurality of the opera's musical inspirations mirrors (albeit imperfectly) the plurality of the First Czechoslovak Republic (itself an example of an imperfect plurality).

This article seeks to unravel this plurality, focusing on the conception and subsequent reception of Schwanda the Bagpiper in the context of various expressions of nationalism, anti-Semitism and Jewish identity politics throughout the interwar period, and taking into consideration the many historical, political and musical junctures before and during this trajectory. It argues that in Schwanda the Bagpiper, while remaining rooted in the Czech nationalism of the nineteenth century, Weinberger sought to blend various cultural expressions thereby seemingly feigning what Andrea Orzoff has termed the ‘myth’ of the Czechoslovak state with an assumed openness and tolerance at its core.Footnote 11 In reality, Schwanda the Bagpiper embodies the transitory state of nationalism during the interwar period. It represents the liminalities of young Czechoslovakia's nationalism: Czechness takes on a dominant role, while the minority cultures of the new multi-ethnic state, though not being ignored, were treated as second rank.Footnote 12 This actual position of minorities is reflected not only in the opera itself, but also in its reception, which was marred by anti-Semitism. In this way, Schwanda the Bagpiper represents what critical theorists and philosophers have broadly recognised as the close connection between nationalism and anti-Semitism with their intertwining ideological patterns.Footnote 13

By unravelling this connection and further interrogating its meaning, this article is in concert with Weinberger's own trajectory, which steadily built up to Schwanda the Bagpiper and then slowly faded out with the onset of World War II. Methodologically it approaches music as both subject (through musical analysis) and mode of cultural experience and understanding (through cultural analysis), and provides a hermeneutical perspective. In what follows, the above-mentioned junctures that accompanied the creative process and conception are outlined; the libretto and the music are then analysed with special attention to the cultural and aesthetic elements they synthesise. The different phases of reception of the two versions are then scrutinised, first in Prague and then in Europe and beyond, to provide a deeper understanding of how and why the work vanished from the performance canon, and of the role of nationalism and anti-Semitism in this disappearance.

Junctures

Jaromír Weinberger was born four years shy of the turn of the century, in the Jewish Quarter in Prague known as Josefov. By that time, the Jewish population of the Czech lands had experienced major transformations. In 1867, Jews in Bohemia became equal citizens following developments in the Austro-Hungarian Empire of which the kingdom was a part. They were also undergoing a rapid process of acculturation. Rooted in a multicultural locale, the Jews of Bohemia could choose to align with either the Germans or the Czechs, with many leaning towards the former as perceived carriers of the high culture (and language) of the region.Footnote 14 Naturally, this led to conflict with the Czech majority. And these were not the only complexities of that time, as historian Ezra Mendelsohn posits: ‘Czech-Jewish relations were clouded by the Jews’ cultural and political pro-German position … [and] while there was no lack of popular anti-Semitic manifestations during the nineteenth century, Czech politics on the whole remained relatively free of anti-Semitism.’Footnote 15

Change was under way in the last decades of the century, however, when a new movement popularised Czech language and culture among the Jewish population, and prompted by Jewish support for Czech national aspirations, a political rapprochement began. In parallel, the support of German national interests ceased.Footnote 16 (And in another parallel, Zionism began to rise, with the foundation of the Prague group Bar Kochba, which brought together those who had allied with the Germans and those who had previously identified with Czech nationalism.Footnote 17) This rapprochement would collapse, however, in the 1890s under pressure coming from a number of directions.Footnote 18

Growing up in the small village of Sedlov where the family had lived and farmed for generations, and following his parents’ choice of schooling, Jaromír oscillated between Czech culture and German. His first compositions, conceived at the age of nine, were sent to the Emperor – an example of Habsburgtreue, which at the time was a way of navigating Czech and German nationalisms.Footnote 19 Pieter M. Judson explains this seeming dialectic of loyalty to the Habsburg Empire on the one hand and to the new nation on the other by noting that ‘both the empire and the dynasty generally remained popular’.Footnote 20 Weinberger's self-identification as a composer would solidify temporarily upon studying with significant figures of the Czech music scene, at first privately with Jaroslav Křička and Václav Talich, and later at the Prague Conservatory with Karel Hoffmeister and Vítĕzslav Novák, the latter a Dvořák pupil and one of the country's leading creative figures. Like many of his contemporaries, he also enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatory, taking lessons with Max Reger, whose rigorous approach to counterpoint would leave its traces in Weinberger's own compositions, manifested overtly in Schwanda.

The works that preceded Weinberger's opera were quite varied. A young composer in war-stricken Prague, Weinberger adhered stylistically to impressionism, as is evident in the three pieces for small orchestra Tři kusy pro malý orchestr (1916), Don Quijote (1916/1917) and Sentimentální rozhovor (A Sentimental Conversation, 1917). Earlier works resonated with the critics, among them chamber music, Veseloherní ouvertura (Humorous Overture, 1913) with the popular Czech song ‘Pepíku, Pepíku’ as the main theme, and the one-act pantomime Únos Evelinin, op. 5 (The Abduction of Evelyne, 1914), based on František Langer's play by the same name.Footnote 21 The pantomime had impressed Max Brod so much that he devoted an article to Weinberger – possibly the starting point of the writer's support. At the time Brod, today best known for his friendship with Franz Kafka, was a well-recognised journalist and cultural critic, noted for his early support of Leoš Janáček's opera Jenůfa, which he had just translated into German.Footnote 22 He shared his impressions of Weinberger's Únos Evelinin in Die Aktion, a German literary magazine focused on (left-wing) political issues and literary expressionism:

It is like blushing with excitement when you hear it! You feel ashamed. The very young composer Jaromír Weinberger in Prague fecit. One can play it in less than half an hour, the exploratory municipal theatre in Prague-Vinohrady (Czech) has played it countless times, even generating excellent revenue from it – and I can only commend all music publishers and theatre directors to take part in a race after this dainty opus; they will be grateful to me.Footnote 23

With the symphonic poem Don Quijote, however, Weinberger seemed to have struck a different chord, one that Brod addressed concernedly in the Zionist weekly Selbstwehr:

If the Czechs face such an unequivocal Jewish phenomenon as Mahler without comprehension, it cannot be a surprise … that neither our political nor our cultural nor our social position is clear to the Czechs. Good will seems to be lacking. A small example: last winter the young composer Jaromír Weinberger had his symphony Don Quixote performed at the Czech Philharmonic, a work … that shows seriousness and unusual talent … What happened? The Czech press almost unanimously attacked the opus of this Czech Jew, who most certainly feels like a Czech today. Of course, there is nothing wrong with disparaging criticism. And nothing contradicts the view that the Czechs do not wish assimilated Jews to penetrate the country. But that many critics proceeded from the implicitly taken-for-granted proposition: ‘Weinberger is Jewish, therefore he cannot be a creative talent’ – that is the serious, the most terrible thing about this matter.Footnote 24

While his aim here is to point to anti-Semitism in music criticism, the article also stands out from a series of attacks by Brod against the attitude of Czech Jews, particularly artists whose work unleashed prejudices.Footnote 25

A few months later politics would lead to further junctures. Before the war's end, in October 1918, Czechoslovakia emerged as one of the successor nations of the Empire, and as a home to three ‘nations’ (Czechs, Slovaks and Ruthenians) and three sizeable minorities (Germans, Magyars and Poles) – an ‘Austria-Hungary in miniature or an imagined community’.Footnote 26 In parallel, relations between the progressive Czech nationalists and the Czech-Jewish movement improved, both uniting as promoters and defenders of the new political order. As historian Hillel Kieval asserts: ‘Their political purpose now appeared to be reduced to insuring Jewish support for the new state, their cultural program to achieving a more effective integration with the Czech national majority.’Footnote 27

This course may have influenced Weinberger's next move, perhaps reinforced by the criticism of earlier works that were all but Czech in content. Already known as a composer of light (stage) music – the aforementioned overture and pantomime – he began to entertain the idea of an opera based on a Czech legend.Footnote 28 Librettist Miloš Kareš (1891–1944), a close friend and colleague with whom Weinberger had previously collaborated, shared two ideas: one on the robber Václav Babinský with a parodical quality and another on the mythical bagpiper Švanda.Footnote 29 That each drew from a familiar subject from local popular culture suggests that Weinberger wanted to engage deeply with Czech history, perhaps in response to earlier criticism or as a (re)affirmation of his Czech identity. But the path towards the final version was by no means straightforward and acceptance would prove elusive.

The first such sign was the increase in popular anti-Semitism, which erupted intermittently between December 1918 and 1920.Footnote 30 In the midst of this falls Weinberger's rendition of the Zionist anthem ‘Hatikvah’ for voice and piano, arranged in 1919 and dedicated to one of the Zionist groups, most likely Bar Kochba, which heavily supported musical activity.Footnote 31 Whether Weinberger was part of the Jewish intelligentsia centred around Brod, who strongly supported Zionism, cannot be ascertained, though this setting might have been conceived in concert with the Zeitgeist. But through these cornerstones – a Czech libretto and the setting of ‘Hatikvah’ – it seems that Weinberger was caught between patriotic Czech Jews and Zionists, and it was the latter that would prevail. Hillel Kieval sees the prevailing of Zionism as a relative ‘success’:

In the end, both the Zionist victory and the Czech-Jewish defeat proved to be more ephemeral than real. The government's recognition of the Jewish nationality did not alter long-term social and cultural developments within Czech Jewry. The Zionists did not achieve a revolution in Jewish consciousness, nor did the pace of Jewish integration slow down. In fact the reverse was true. Most indicators showed a dramatic increase in Jewish integration into Czech society at all levels between 1918 and 1939.Footnote 32

Self-integration into the Czech mainstream also defined Weinberger's trajectory as composer. Only a few more ‘Jewish’ works are documented, one created a few years after the historic juncture of 1933. Canto ebraico | נעימה עברית | Chant hébraïque | Hebraic song attested to his knowledge of Jewish prayer, its eighty-two-page manuscript titled in multiple languages as if to address specific Jewish diasporas – though curiously omitting Czech, German and Yiddish.Footnote 33 Weinberger conceived the work as a ‘Hebrew’ symphony, with an optional chorus at the end singing two core prayers, the Shema Yisrael and the Kol Nidre.Footnote 34

In the meantime, Miloš Kareš had sent libretto drafts, but they came at another juncture. Weinberger had just left the capital, assuming a guest professorship at Ithaca Conservatory in late 1922.Footnote 35 This might have been a welcome change for many reasons: aside from the monetary benefits, there was a growing ethnic and religious self-consciousness amongst the Jews of Prague in the aftermath of the November 1920 anti-Semitic riots, during which Czechs broke into the Jewish Town Hall, vandalised archives and destroyed Hebrew manuscripts. Weinberger might have been aware that Smetana's archetypical Czech national opera was performed impromptu during the night of anti-German and anti-Jewish demonstrations on 16 November; it was widely celebrated in the press (that night the local Neues Deutsches Theater was briefly occupied and the Deutsches Landestheater forcibly annexed as a branch of the Národní divadlo).Footnote 36 But already in 1919 Weinberger himself had become a target during an altercation with the young opera director Ota Zítek, which culminated in the alleged verbal attack: ‘You dirty Jew, during the pogrom we'll hang you from the lamp post first!’Footnote 37

What can be said for sure is that with Weinberger's arrival in New York, his interests shifted: he immersed himself in American culture, a move that would have a sustained impact on his compositions.Footnote 38 He asked Kareš to work on a libretto based on The Outcasts of Poker Flat (1869) by American writer Francis Bret Harte (1839–1902), a story that engages with American culture, drawing upon local colour and realism during the Gilded Age, with four immoral characters exiled from a gold rush mining town after its inhabitants decide to cleanse it of revolting elements.

Only a year later Weinberger returned home, taking the position of dramaturg alongside Oskar Nedbal at the recently founded Slovenské národné divadlo in Bratislava (the history of Slovak opera runs behind that of Czech opera by about a century, only developing with the formation of the new state). During this appointment, from 1923 to 1924, he came in closer touch with Slavic culture through the national dramatic works he helped bring to the stage. He wrote an overture to an old Slovak comedy, which was widely performed in concert in early 1925. He also resumed discussions with Kareš about an opera on the Švanda subject for, so he said, ‘purely musical reasons’.Footnote 39 A national opera again became a pressing matter – and a likely one.

Švanda dudák originated not just at biographical and political junctures, but also at music-historical ones. It was conceived late in the aftermath of the nineteenth-century Obrození or Czech Cultural Revival, a movement formed by a group of Czech intellectuals who were concerned with national identity. They brought the Czech language into widespread modern usage and instigated a renewed interest in Czech history and folklore. Czech opera, too, had a designated role in the growth of national unity. Through its librettos it intentionally linked the historical periods of the past with contemporaneous national desires.Footnote 40 In this sense, Bedřich Smetana paved the way for Czech opera. Other nineteenth-century composers followed.Footnote 41 By the time Jaromír Weinberger came of age, Czech opera had been firmly established and was ripe for a new direction, though World War I put a temporary hold on it. At the end of the war, however, Prague as a true European capital began to strive for cultural change, negotiating conservatism and twentieth-century modernism. But how Czech can one be while also being modern? How modern can one be without losing one's audience? These were the questions that played out on the opera scene in the capital of a new and self-aware nation.

Syncretisms

Weinberger and his librettist approached nationalism by way of established ethnosymbolism – myths, histories and a musical language derived in part from folk music and dance, but responsive at the same time to contemporary idioms. By this means, they created an opera that uniquely blended the local/traditional and pan-European/modern for a new nation, in which the Czech continued to dominate. Indeed, as Michael Beckerman and Jim Samson assert, ‘[it] was through using stylized or arranged folk music as a symbol for the ideal nation and more contemporary idioms for the real world that [composers] sought to establish links between the tradition of folk opera and western European modernism’.Footnote 42 To provide a basis for this, the final libretto draft merged the original two topic propositions into one, thereby creating an over-the-top pastiche of legends and stories, exhibiting Slavic culture in high concentration, and in stark contrast to other Czech operas of the time. Nevertheless, Kareš took Czech folklore as a point of departure for a free development of the subject matter. He did so by integrating notions that had not been treated earlier with familiar subjects and by leaning on fantastical elements, while also drawing from Slovak culture. Through this mélange of characters and subjects, the librettist distinguished the plot from previously used similar subjects.

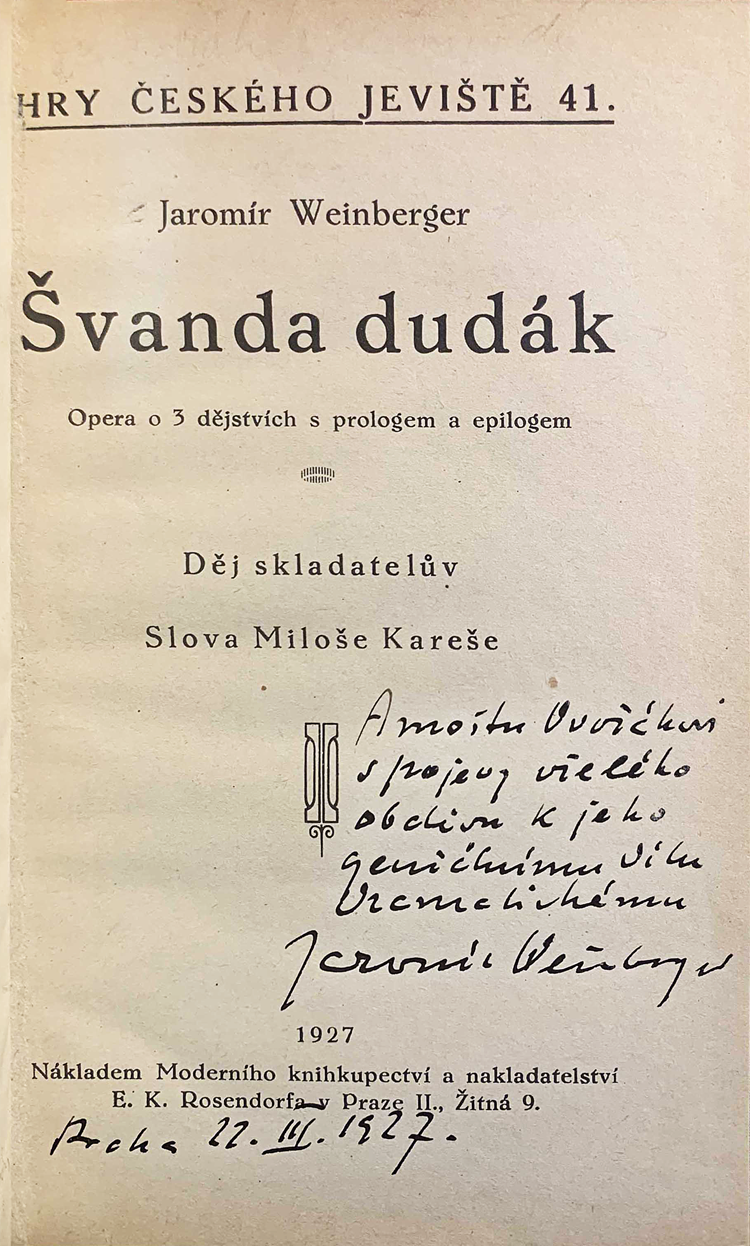

In its completed Czech-language version (Figure 1), the libretto revolves around the legend of the bagpiper of Strakonice, a town in southern Bohemia, about sixty miles south of Prague and a centre of bagpipe tradition since the sixteenth century. The local tale of Švanda, a village Orpheus with a folk instrument of magical powers who overcomes all obstacles, arose there in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century, becoming a powerful symbol of Czech musicianship. Like the Meistersingers and their hero Hans Sachs, the pipers of Bohemia (and possibly Švanda himself) had a historical reality.

Figure 1. Title page of the first edition of Miloš Kareš's libretto.Footnote 43 The Pierpont Morgan Library, Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection, New York. PMC 418. Reproduction courtesy of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

In addition to folkloric sources, Kareš considered dramatic versions of the legend. Ballads by the Czech poets Jaroslav Vrchlický (pseudonym of Emil Bohuslav Frída, 1853–1912) and Jan Ladislav Quis (1846–1913)Footnote 44 inspired him to incorporate several parts in verse form. Kareš also relied on a cantata by Karel Bendl (1838–97) and the famous play Strakonický dudák (1847) by the Czech dramatist and representative of the Czech Cultural Revival, Josef Kajetán Tyl (1808–56).Footnote 45 Strakonický dudák had been a huge success with the public, especially during the nineteenth century. The fairy-tale elements in the play and the opportunities they provided for an exotic spectacle as well as scene transformations contributed to its success.Footnote 46 The enthusiastic reception in the region might have been due to widespread familiarity with the southern Bohemian folktale, which served as Tyl's source. Indeed, the bagpiper seems to have struck a special chord with Czech audiences, perhaps as the most Czech of the arts or because he embodied ordinary virtues.Footnote 47 After all, Švanda is a folk musician who plays an instrument rooted in Bohemian folklore, suggesting that his musicality was inherent rather than acquired. Švanda thus corresponds to the idea of the unique musicality of the Czech people, an idea that Charles Burney had more generally perpetuated after visiting Prague in 1772.Footnote 48

Weinberger and Kareš must have been well aware of this reception and of the numerous other stage works conceived between 1880 and 1917 that embraced the subject, perhaps hopefully anticipating similar success.Footnote 49 Drawing from different sources that had already proved effective with Czech audiences, Kareš transformed them by incorporating new ideas for his own foray into the subject. He relied on Tyl only in the prologue and treated the subject of Švanda freely throughout. Kareš created a lively and happy Švanda character, whose cheerful nature and spell-binding musical instrument helps him to overcome all obstacles – a popular subject widely used since Mozart's Zauberflöte.

The greatest transformation, however, was the merger of two stories by adding as antagonist the legendary robber Václav Babinský (1796–1879), a criminal who was held in Špilberk, the Habsburg Monarchy's infamous prison. But instead of drawing on the historical figure Kareš fused different characters from legends and folklore. One was the late eighteenth-century robber Kovařík, who ruled in the eastern Czech lands and was known for adventurous escapes and for mobilising the Czech soldiers against Habsburg oppression – a timely reference to history in the aftermath of secession from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A second inspiration was Juraj Janošík (1688–1713), a legendary figure in Slovak history and known as the scourge of the rich and the protector of the poor, who was eventually executed.Footnote 50 A central character in many legends, his exploits were the subject of popular song.Footnote 51 But the Babinský character also integrates attributes stemming from beloved European folk and fairy tales including Robin Hood, Till Eulenspiegel, the Pied Piper and Rumpelstiltskin.

The main female protagonist, Dorotka, is in turn freely invented (she is already present in Tyl's play). Her recurring song, in which she expresses her love for the countryside, exhibits her as an embodiment of a pan-Czechoslovak rural life, though by association the song is Czech:

A folk tune, ‘Na tom našem dvoře’, was customarily sung in productions of Tyl's Strakonický dudák;Footnote 52 Dvořák had relied on it in a stylised adaptation in the incidental music for František Ferdinand Šamberk's play Josef Kajetán Tyl (he also employed the various dance forms discussed below). Weinberger had used it before, in his first attempt at an opera, Kocourkov (1923–4).Footnote 53

‘Na tom našem dvoře’ occurs early on in the plot, which can be summarised as follows. Švanda, a fine bagpiper and farmer, lives with his wife Dorotka in the Bohemian countryside. One day the robber Babinský, who is being hunted by foresters, arrives at their home, where he remains unrecognised and receives a warm welcome. Švanda, fascinated by Babinský's stories of other countries and great wealth, agrees to go with him to visit a sad Queen who is under the spell of a wicked magician. Upon arrival at the palace, Švanda's play triggers the desired effect: the entire court begins to dance and the Queen begins to smile. In her re-found happiness she proposes marriage and Švanda consents. Wedding plans stall upon Dorotka's arrival, and the Queen threatens him with execution. He again plays the bagpipes to magical effect and escapes. Dorotka then confronts him, asking whether he kissed the Queen: Švanda replies that he would go to hell if he had. He instantly finds himself there. The Devil tricks Švanda into selling his soul, but he is saved by Babinský, who beats the Devil at a card game. At last, Švanda returns home, but not without encountering another obstacle: Babinský, who wants Dorotka for himself, tells Švanda that during his long absence she had become an old and unattractive maiden. But truth ultimately prevails and Dorotka and Švanda are finally reunited.

While largely rooted in Czech folklore, the plot ultimately layers features of the nineteenth-century Volksoper genre, in the wake of Smetana's Prodaná nevěsta and Dvořák's Čert a Káča, and the Zauberoper, which since the eighteenth century had centred predominantly on the magic of love. Indeed, Schwanda the Bagpiper also includes fairy-tale metamorphoses: a queen under a magician's spell, the power of love which relieves her from melancholy, and the magical sound of Švanda's bagpipe music that awakens her love. They recall Mozart's Zauberflöte, where music also symbolises humanity, love, happiness and the power of (musical) harmony. This similarity is found not merely in the plot, but also in the larger form of the operas: both blend opera seria and opera buffa elements, with sections of spoken dialogue. Folkloristic subjects, characters drawn from legends, the fight against evil, magicians, and special effects on stage are further similarities. Did Kareš turn to Mozart as a recipe for success? Or did the creators seek to conceive an archetypical modern-day contribution to national opera in the aftermath of Czechoslovakia's foundation through Weinberger's music?

Answers to the latter question can be found in the score, so let us return initially to the above discussed folk tune ‘Na tom našem dvoře’. Weinberger adapted it with Romantic phrasing, relying on strophic form and establishing it in B major, a key important in the opera at large. As a theme it is first heard in the overture, introduced by the horns (Example 1), then taken up by the strings with a quasi-impressionistic accompaniment. It is repeated several times with different accompaniment (overture, bb. 174–85, 221–6, 314–30; Act I, bb. 570–82 and 2344–2409; and Act II as stretta of the finale for soloists and full chorus). In bar 222, ‘Na tom’ is enveloped in chromatic passages, exhibiting a common trait in the opera – the juxtaposition of simple melodies and chromaticism. Such contrast is also evident in bar 2357, when ‘Na tom’ is interrupted by an atonal passage sung by Babinský, only to return to its tonic B major in bar 2392.

Example 1. Schwanda, overture, bb. 174–9.Footnote 54 Copyright © 1929 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

From its very first bars, Schwanda also leans on the soundscape of the local bagpipe tradition. The overture begins with a short and poignant motif, which ends on a high trill, a simple signal first introduced by the flutes, accompanied by bass drums, timpani and brass (Example 2). The actual signal, a trill on a high note embedded in major tonality, which prevails in the Eastern European bagpipe tradition, is a key element of the motif. It replicates the signal shepherds in Eastern Europe had used to orient their flocks or to warn of danger.Footnote 55 Weinberger conceived of and used this motif with an almost anthropological knowledge of its original form. In the course of the opera it turns into a leitmotif, which Weinberger repeated (overture, bb. 14–16, 233–5, 295–6, 331–6; Act I, bb. 1254–69; Act II, bb. 1762–4), in fragments (overture, bb. 341–2), in variations (Act I, bb. 1601–2 and 2070–3), and in disguise (Act I, bb. 2065–8; Act II, bb. 393–5). Throughout the opera the motif is played mainly by flutes – either solo or in combination with clarinets – often in high notes to enhance the signal character and underscored with changing orchestrations.

Example 2. Schwanda, overture, bb. 1–3. Copyright © 1929 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

Orchestration with flute or bagpipes in opera was common among Czech composers. In the short orchestral interludes in the opening scene of Čert a Káča, Dvořák used a flute and two oboes in unison for the imitation of bagpipes; in Král a uhlíř, he used a bassoon drone and a melody on a single clarinet. Smetana's bagpiper in Tajemství (Act I scene 4) is represented by a flute and oboe combination with trills, and a drone in fifths on bassoons and open-string cellos. John Tyrrell even suggests there is bagpipe imitation in Prodaná nevěsta, although there is no mention in the libretto or stage directions.Footnote 56

Throughout the opera the motif appears in conjunction with the Švanda character, but it also serves structural purposes. In their original context bagpipe signals had a special communicative significance, for instance to indicate the approaching end of a dance round with a trill on the highest note. Here, the motif introduces new and recurring motifs, and songs, tunes and dances. The instances of Švanda playing the bagpipe coincide predominantly with dance scenes or serve as signals, thus emulating its function in Eastern European practice: Švanda's bagpipe motif sounds in conjunction with the famous polka (Act I, bb. 1254–69) and the furiant (Act I, bb. 2070–3). But it is not used for the introduction of the polka played by the Devil, perhaps to respect the dramaturgy of the scene. But Weinberger incorporated the bagpipe motif in several dances, beginning with the entr'acte of Act I, where he used two dance rhythms in the form A–B–A: in bar 838 he introduced a dance theme that later accompanies the odzemok (b. 1987) – or odzemek, in Czech. It is followed in bar 894 by a dance in the style of the sousedská, a slow Czech couple dance in triple time adopted by a variety of Czech composers, among them Smetana, Suk, Dvořák, Foerster, Křička and Martinů.Footnote 57

The first dance section then returns in bar 1029. But this is only the beginning of a series of dances that define Act I and continue in Act II. Weinberger introduces Eastern-sounding inflections in an orchestral ‘danse tragique’ that conveys the lethargy and gloominess of the Queen (Act I, bb. 1110–85), followed by a series of dance tableaux that use Slavic dance forms, among them the polonaise, odzemok, furiant, with the polka the most Czech by association.Footnote 58 As one of the most popular dances of the nineteenth century, it found its way into the works of various Czech composers, among them Smetana in Prodaná nevěsta, Janáček in Výlety páně Broučkovy, Dvořák in Čert a Káča and Josef Bohuslav Foerster in Debora, to name a few.Footnote 59

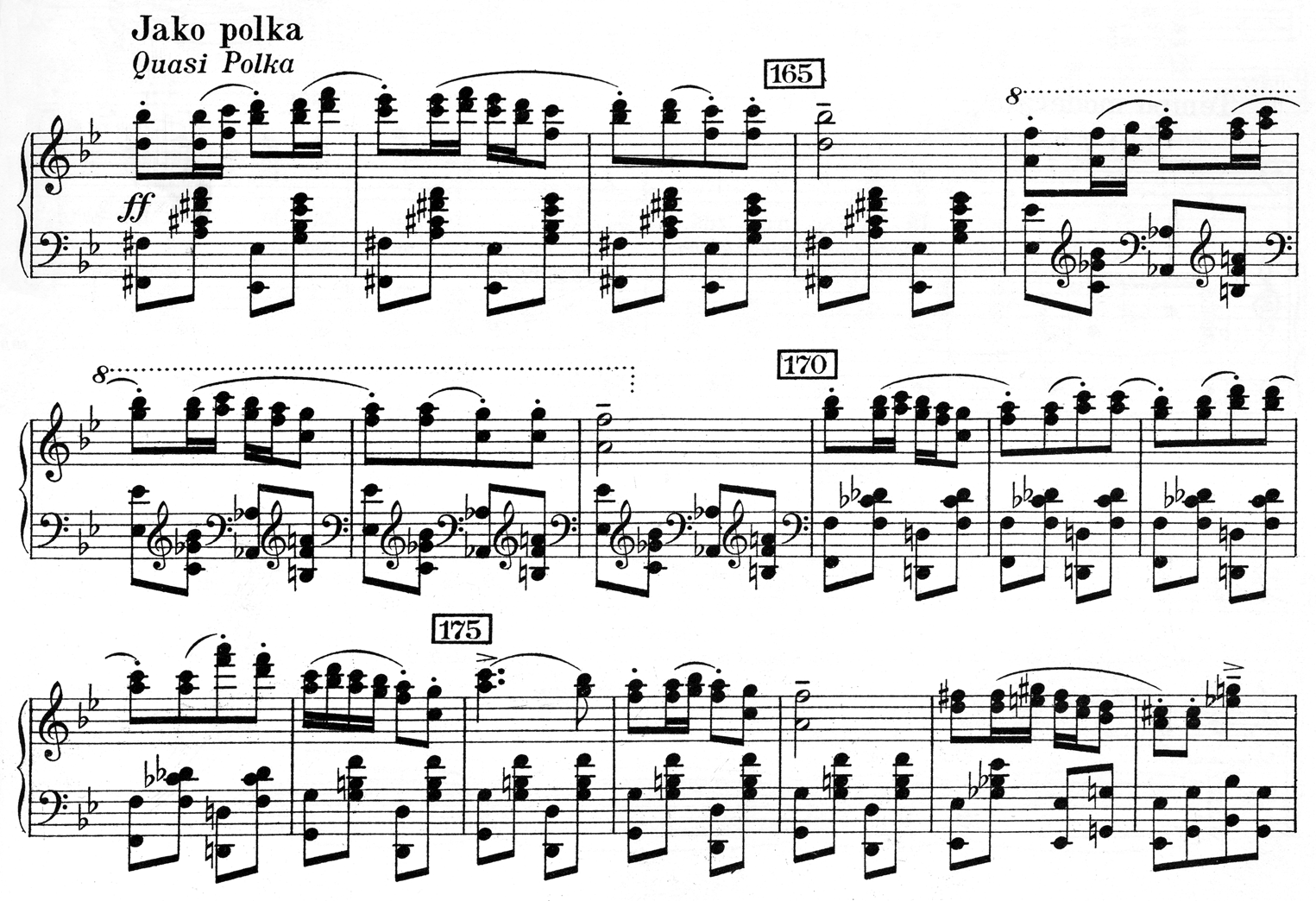

Of all dance forms in Schwanda, the polka is the most prominent. It appears for the first time in Act I, bb. 1270–359. While it may recall the polka from Prodaná nevěsta, it is far more elaborate harmonically. Beginning at bar 1302, Weinberger uses extended tonality with several chromatic sections (notably bb. 1302–10) to break out of the established B major key.Footnote 60 When the polka appears a second time, this time ‘played’ by the Devil in Act II (bb. 144–91), it comes with highly dissonant harmonies as the most overt polytonal passage in the opera to make it integral to the dramaturgy: when Švanda refuses to play for the Devil, the latter takes up the bagpipes himself and plays a truly devilish piece in hell (Example 3). The harmonies recede to tonal configurations when Babinský defeats the Devil in their card game (Act II, b. 1061), celebrating with polka motifs that lead to the famous fugue, which concludes this first scene of Act II. And a last time, Švanda's polka appears – albeit in a radically modified form – as the basis of the entr'acte (Act II, from bar 1551), which leads into the final scene.

Example 3. Schwanda, Act II, bb. 162–79. Copyright © 1929 (Renewed) by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

In Act I scene 3, when Švanda again plays the bagpipes, he does so to the rhythm of the odzemok, a Slovak shepherd's dance, performed only by men and incorporating spectacular leaps.Footnote 61 Weinberger uses it in close connection with the story line: when Švanda plays the odzemok shortly before his execution, his performance is so masterful that he can literally leap away while everyone is dancing. As before, Weinberger introduced the dance with conventional harmonies to enhance its folkloristic character, only to move on to complex harmonic patterns with such heavy chromaticism that no tonal centre is discernible.

Weinberger's deep knowledge of these dance forms and his clever dramaturgical application also becomes evident in the Bohemian furiant, a fiery dance that is impulsive in character with abruptly changing rhythms.Footnote 62 He aptly employed it for the trio of Švanda, Dorotka and Babinský – a classic husband and wife confrontation in which she furiously attacks him for infidelity and irresponsibility, while he remonstrates and conciliates. As with the other dances, the furiant has been quite popular among Czech composers: Dvořák used it for numerous movements in many instrumental works;Footnote 63 Smetana combined it with a polka in his overture to Prodaná nevěsta and used it in the second act when the village men celebrate and drinking leads to dancing.

The use of bagpipe imitations, folk tunes and various dance forms in the wider historical context confirms that they belonged to a shared musical vocabulary of that time and region. What makes Schwanda the Bagpiper stand out is the use of dance in the service of dramaturgy and in combination with an advanced contrapuntal and harmonic style, which freely oscillates between chromaticism, extended tonality and even atonality. Weinberger used divergent compositional layers: folkloristic elements serve as an attractive surface under which complex compositional techniques and progressive harmonies are less perceptible. In this stylistic synthesis, rooted in Czech historical consciousness, Weinberger drew from both Romantic operas and early twentieth-century music aesthetics. He furthered ideas of the Cultural Revival in its form, while interlacing contemporary elements. By merging the dichotomies of historicism/past and modernism/present in a comic opera, Weinberger envisioned how nineteenth-century Czech nationalism might be conceived in the new republic. Ultimately, in its synthesis of local histories and European fairy tales, Schwanda is reflective of a new nation, but one in which minorities had clearly differentiated ranks. Slovak culture was included, and there is even a tinge of Polishness in the allusion to Janošík and the use of the polonaise for the engagement celebration of Švanda and the Queen (Act I, bb. 1495–553 and bb. 1605–28, introduced by the bagpipe motif in bb. 1601–4).Footnote 64 There is also a suggestion of Germanness in the Ländler, a dance to whose rhythm Švanda introduces himself at the court of the Queen (‘Jsem český dudák’, Act I, bb. 1362–477). Indeed, through various dance forms and rhythms, Švanda gives a nod to a young multi-ethnic nation, though without questioning or downplaying its Czechness. The cultures of other sizeable minorities – Ruthenians and Magyars – are completely absent, however, reflecting political realities in interwar Czechoslovakia. Weinberger, caught in his own in-betweenness of identity, could have composed more assertively for the new and ethnically complex nation (as noted above, the creative process of the opera took place in parallel with the decline of the Czech-Jewish movement and growth of Zionism). Whatever his intent, it is not documented, although one may wonder whether such affirmation of Czechness derived from his own patriotism or fear that anti-Semitism could compromise his career. This tension becomes all the more obvious when the reception of the world premiere in Prague is considered.

Reception of the Prague premiere

Švanda dudák received its world premiere on 27 April 1927, at the Národní divadlo in Prague under Otakar Ostrčil (1879–1935). The theatre certainly was a prestigious and suitable place for the performance of a young composer's opera, and fitting for Švanda dudák and its nationalist approach. The opening of the theatre in 1883 had been a visible symbol of successful Czech efforts to establish the nation's own cultural identity in the face of Austrian political and cultural domination.Footnote 65 The choice of repertoire strengthened this identity: there was a steady proportional increase of Czech works at the Národní divadlo and over 50 per cent of all operas performed during the 1920s were in Czech.Footnote 66

Švanda was produced by Ferdinand Pujman (1889–1961), one of the most prominent producers in Prague at the time and known for his modernist operatic concepts. The sets by the acclaimed painter and stage designer Alexandr Vladimír Hrska (1890–1954) were of modern stylistic simplicity. The theatre's choreographer and chief of ballet Remislav Remislavský (1897–1973) staged the dance numbers.Footnote 67 A hit with audiences, Švanda was performed thirteen more times through to 4 November, though under František Škvor, a younger conductor and composer.Footnote 68

The reviews following its world premiere were mixed to say the least, however. As Brian Locke has previously discussed, Czech critics and composers trounced Švanda as shamefully fraudulent, a harsh rejection indeed.Footnote 69 Locke interprets the negative reception as an expression of the ‘anxiety from which the Czech musical community was suffering at the crossroads of modernism, populism, tradition, and international recognition’.Footnote 70 Indeed, the premiere took place just five months after what became known as the ‘Wozzeck Affair’, the failed Prague premiere of Alban Berg's opera, which first exposed the Czech musical community to international modernism.Footnote 71 Subsequently the theatre administration denied Ostrčil the chance to present another work that could be perceived as inflammatory. Švanda dudák, with its rather popular couleur locale and apparently anti-modernist music, seemed like a counterweight to Wozzeck.Footnote 72

While there is no doubt that ideology and expectations about modernism in opera factored into the reviews, they also reflected the lingering popular anti-Semitism of the time regarding Weinberger's heritage, and they did so in the most overt way possible.Footnote 73 Among the first reviewers, Karel Jírak pointed to what he perceived as a naïve patriotic audience who applauded without any concern about the Jewishness of the composer. He added in parenthesis: a real Jew, not like Wozzeck's author. Although he was not Jewish, Berg's relationship with Schoenberg (and his compositional style) would later put him on the list of degenerate composers, and Jírak's comment might refer to and anticipate exactly that association. Accusations of plagiarism followed (‘If Smetana and Dvořák were alive they would use the Czechoslovak copyright law’) and the opera was judged for exploiting national values and popular arrangements for cheap success in ways that Weinberger found embarrassing, but without explaining which values exactly were in question and what concept of nation.Footnote 74 However, not every critic perceived Švanda as unoriginal. In a generally lenient review, for example, Rudolf Jeníček insisted that one could not call his work merely epigonal.Footnote 75

As the above analysis has shown, Weinberger's use of folklore, local dances and tunes, and native language leans on the Herderian model of musical nationalism employed by many composers into the twentieth century, most notably Jaroslav Křička and Vítězslav Novák.Footnote 76 Weinberger adapted pre-existing materials, transforming and synthesising them in line with neoclassical aesthetics by creating an eclectic blend of traditional simplicity and modernism through overt chromaticism and bi- and polytonal passages.Footnote 77

These facts remained unrecognised by Alois Hába, one of the very few boundary-pushing representatives of the Prague avant-garde, who focused on Weinberger's ‘plagiarism’, which he deemed intentional due to its very obvious resemblance to other works.Footnote 78 Indeed, he refrained from denouncing Weinberger as epigone, assuming instead that he copied consciously. But this he condemned as far more dangerous. He attributed the opera's success to the audience's incapacity to realise the difference between creative act and illusion, or (alluding to his nationalism) to recognise that Weinberger manipulated values for which other composers had fought.Footnote 79 Hába also found it necessary to define the nationalism of the critics as a group (note the oscillation between treating Weinberger as insider or outsider of Czech culture):

We are not anti-Semites. We will not even become such people so long as we maintain our own creativity. Weinberger is perhaps the first serious Czech-Jewish artist. He will be measured as we measure ourselves. He will achieve artistic equality only if he strives to create new values with the same integrity as our other artists. We do not seek the creator's compliments about our culture and we will consistently fight unproductive flattery, as happens in the fable ‘The Crow and the Fox’.Footnote 80

Hába continued with examples of composers that Weinberger should model himself upon, all of them of Jewish descent: Mahler, Schoenberg, Toch and others from the German-speaking lands; Schulhoff and Haas from Czechoslovakia. Ultimately Hába seemed deeply disturbed by Weinberger's reliance on Czech cultural heritage as a Jew, an anti-Semitism so latent that he himself denied it.Footnote 81

Zdeněk Nejedlý was a dogmatic advocate of Smetana's work and known to have stirred up hostility against those not supporting his agenda (to purge Czech musical life of those he considered unworthy, immoral and unpatriotic). He used the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia as an outlet to condemn the perceived borrowings as a ‘galimatiás’ of quotes taken from Libuše (majestic pomp), Prodaná nevěsta (merry scenes), Janáček (character of the Devil) and different works by Dvořák (dances).Footnote 82 ‘Galimatiás’, as Locke has pointed out, referenced the tower of Babel and thereby Weinberger's heritage.Footnote 83 Turning the table on his own anti-Semitism, Nejedlý claimed that the audience – who included fascists – had flocked to the theatre to applaud Švanda dudák, in much the same way that they had come prepared to castigate Wozzeck.Footnote 84 (Jírak, Nejedlý and Josef Hutter had all supported Wozzeck.) Lastly, Nejedlý, with his orthodox nationalist view of Czech composition and of Czech composers’ responsibility to the nation, found it ironic that a Jew had composed what he predicted could become a ‘fascist anthem’ – referring to the recurring theme song of Dorotka, which Weinberger had adapted from a folk tune.Footnote 85 This was a sly way of revealing his anti-Semitism while distancing himself from fascism.

Hutter criticised the opera as a chain of kitschy, sentimental, grotesque, folk-like and national scenes in the official mouthpiece of the composers’ union, Hudební rozhledy, and compared its effects to the newly emerging revue genre, but he refrained from attacking Weinberger's heritage overtly.Footnote 86 Indirectly, however, he positioned Weinberger as an outsider, as someone who did not belong to the inner circle of Czech composers. Indeed, for Hutter, Weinberger's dedication to three important representatives of the Czech National Revival – Josef Kajetán Tyl, Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák – was damaging to true national feeling. He continued that such nationalist ostentation, which had involved stealing from other composers’ scores (including Libuše), could be nothing but a conscious and cynical mockery of true Czech tradition. As Brian Locke has pointed out, this lack of invention that Hutter perceived stemmed from a threefold system of borrowing: the overall dramatic concept, organisational ideas and the musical notes themselves.Footnote 87 But a close look at the score does not provide proof and Hutter does not share concrete examples: as demonstrated above, the dramatic concept constitutes an amalgamation of ideas widely in use and the musical notes quoted stem from existing folk tunes employed by other composers as part of a shared tradition. Ultimately, Hutter argued from the assumption that as a Jew, Weinberger should not be allowed to participate in or draw from the cultural heritage of his own country.

Jaromír Borecký, a literary figure, took a different route to smear Weinberger. He opened his review in the Národní politika – a Czech daily with little emphasis on politics – with a seemingly innocent reference to Tobias Mouřenín's 1604 Czech adaptation of Dietrich Albrecht's verses Eine kurtzweilige Historia, welche sich hat zugetragen mit einem Bawrenknecht vnd einem Münche (Erfurt, c.1500) as Historie kratochvilná o jednom selském pacholku, in which Mouřenín had exchanged the character of the monk for a Jew, thereby replacing the originally anti-Catholic message with an anti-Semitic one.Footnote 88 The verses narrate how the monk/Jew ends up in a thorn hedge, where he has to dance naked for money and gets scratched to the core. The analogy with the prevailing view that Weinberger tried to capitalise on Švanda by using pre-existing (dance) music is clear, although Borecký quickly stepped back from anti-Semitic stereotyping by claiming that Mouřenín's verses were merely an example of a successful adaptation. He then transitioned to show how this story fertilised others, ultimately leading to Tyl. Still, an unreflected transmission of Jew-hatred reveals itself twice – in its traditional form (Mouřenín's adaptation) and as modern anti-Semitism (Weinberger) – and readers most likely and even subconsciously recognised the stereotypes.

The Prague critics condemned many prominent composers,Footnote 89 embodying what Christopher Campo-Bowen has called ‘the calcification of the Czech critical environment’, which took place during the first half of the twentieth century, ‘occasioned by war and virulent nationalism’.Footnote 90 But the fact that Weinberger was the only Jew contributing to Czech opera meant that their reception was not merely ideologically driven: it was also vindictive. For them, his heritage in combination with an overt display of Czech culture caused discomfort bordering on rage – though hardly any of them took into consideration that Švanda was framed as a national opera. In light of Weinberger being Jewish, his national opera conceived during a time of pervasive change offers a dialectic, suggesting an ironic distance, which is a decisive feature of the prevailing neoclassicism.Footnote 91 Be that as it may, the need to condemn Weinberger in such a way affirms the idea articulated by Karin Stoegner and Johannes Hoepoltseder that ‘exclusionary nationalist identification cannot do without antisemitism, in whatever latent form, as this combination seems to meet the need for certainty, stability, and unambiguous belonging in crisis-ridden periods’.Footnote 92 Much of the critical rhetoric is reminiscent of that found in Wagner's infamous tract ‘Das Judenthum in der Musik’ (1850/69) – conceived at the historical juncture between religious and racial anti-Semitism – which had long been known in Bohemia.Footnote 93 Although this may have been unintentional, considering the de-Germanification of Czech culture at the time, Wagner had nevertheless played a central and complex role as a political and aesthetic model for nineteenth-century Czech nationalism – but with the potential to undermine it.Footnote 94

Some Czech critics refrained from Othering and anti-Semitism, however, staying focused only on the music, but nonetheless refraining from praise.Footnote 95 The opposite is true for the reviews in German describing Švanda as ‘moderately modern’,Footnote 96 with its atonality far from being ‘artificial’.Footnote 97 In fact, all German-language reviews, published between May and September of 1927, were overwhelmingly positive, celebrating the opera as a sensational success, and announcing and anticipating Brod's translation into German.Footnote 98 (Brod himself had written a review, offering universal praise.Footnote 99) In these reviews, Weinberger is presented as Czech composer, with no mention of his heritage. What the Czech critics condemned as false nationalism, because it stemmed from a Jewish composer, Austrian and German reviewers might have understood as nationalism coming out of a multi-ethnic Czechoslovakia. From the outset, Švanda's seemingly divergent reception abroad apparently hinged on its perception as a nationalist work.

The rise of Schwanda

Reception in Prague did not affect the opera's further trajectory, in spite of rising anti-Semitism. Perhaps what Christopher Campo-Bowen asserts for Prodaná nevěsta's reception abroad proved true for Schwanda as well, namely that ‘it clearly moved freely across national boundaries, the composer and his opera [being] interpreted differently based on the observer and the context in which they found themselves’.Footnote 100 The person who set this movement in motion was none other than Max Brod, who right after the premiere phoned Hans Heinsheimer, editor-in-chief of the opera department at Universal Edition from 1923 until 1938. He recalls:

In Europe, a long-distance call is made only in an emergency, and even then people will usually cancel the call before it comes through and write a letter instead … Max Brod's long-distance call (all the long distance from Prague to Vienna) could therefore mean only that something of paramount importance had happened. ‘I think I have discovered a gold mine’, came Brod's voice over the phone. ‘Last night I heard at the Czech National Opera here in Prague a new work by Jaromir Weinberger called Shvanda. Tomorrow night will be another performance, and you must come and hear it. It is a magnificent piece, and I predict another world success.’Footnote 101

Brod's first prediction of a ‘world success’ refers to Janáček's Jenůfa, which he had ‘discovered’ back in 1916.

Facing the possibility of competing with another publisher, Heinsheimer travelled to Prague and concluded after the first half of the performance: ‘I decided right here that I wanted Shvanda at once and that I was not going to take any chances with Bote & Bock or anybody else, although I had found out that the story of Bote & Bock was nothing but a successful hoax.’Footnote 102 Right after the performance the contract between Universal Edition, Weinberger, Kareš and Brod was drafted. In the absence of paper, the dinner menu was pressed into service – a document that was destined to make brief but significant music history.Footnote 103 The next year, in 1928, Universal Edition published the revised version in Czech with German translation, as Schwanda, der Dudelsackpfeifer. Max Brod had shortened and adapted the libretto to make it more accessible. In addition to making structural changes,Footnote 104 he also altered relationships, including the one between Švanda and Babinský, who become adversaries. He enhanced fairy-tale elements and made sure that audiences would not need any knowledge of Eastern European folklore to understand the plot, effectively turning the piece into a pan-European tale: the story of a simple bagpiper who leaves his wife and home, venturing into the underworld of magicians and devils in search of fortune, and at the end returning to his simple beginnings as a happier and wiser man. A story with international appeal.

The new version premiered in October 1928 at the municipal theatre in Plzeň, a city about fifty-six miles west of Prague with a significant German population.Footnote 105 The new version, in Czech, received a performance in November at the Moravské divadlo in Olomouc under Emanuel Bastl and on other stages. By then the premiere in Germany had long been announced to take place in Breslau (today Wrocław, Poland).Footnote 106 On 16 December 1928, Schwanda, der Dudelsackpfeifer celebrated its first performance there, staged by Herbert Graf and directed by Helmut Seidelmann, with set designs by Hans Wildermann. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive with few exceptions.Footnote 107

The Breslau performance constituted a crucial step towards the opera's world success. Clemens von Franckenstein from the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich attended the performance and immediately planned to produce it as well.Footnote 108 The South German premiere took place there on 14 March 1929, under Hans Knappertsbusch.Footnote 109 Munich, just emerging as the city of the Nazi movement, embraced the work fully and wholeheartedly.Footnote 110 The performance was a breakthrough with many other productions following that year on German soil, in the theatres of Dessau, Münster, Leipzig, Erfurt, Danzig, Hannover, Stuttgart, Dresden, Kassel and Frankfurt am Main, as well as at Berlin's Staatsoper Unter den Linden and in Mainz.Footnote 111

Performances even returned to Prague, but now to the Neues Deutsches Theater.Footnote 112 Indeed, two years after the world premiere of the first version, the second version began its run, on 14 April 1929, with great success.Footnote 113 Ewald Schindler's production used the same stage design (only the dance scenes were newly choreographed by Joe Jenčík). Joseph Winkler and František Škvor conducted the first eight performances; apparently over 100 more followed.Footnote 114 This was perhaps an attempt to cater to the German audience's expectation and taste.Footnote 115 Thereafter Schwanda became part of a Czech opera cycle in Vienna's municipal theatre.Footnote 116 And the Wiener Staatsoper put it on the schedule for the following season.Footnote 117 The Slovenské národné divadlo in Bratislava brought it on stage on 11 September 1929, though it is unclear which version or in which language.Footnote 118 Graz premiered it in November.Footnote 119 Basel's municipal theatre celebrated the Swiss premiere in November 1929.Footnote 120 Teplice's theatre followed in December.Footnote 121

By early 1930, Schwanda had been performed on some eighty stages,Footnote 122 Alfred Einstein wrote an elaborate review for the New York Times based on the Berlin production. He positioned Schwanda as the greatest success in ‘German opera’ [sic] since Krenek's Jonny spielt auf and wondered whether national opera had experienced a renaissance. Although not shying away from criticism – ‘alas! it is simply a work’, ‘he writes no masterpiece’, ‘is not a Bohemian musician of original creative force’ – Einstein, an authoritative and highly respected critic, laid the groundwork for Schwanda's worldwide success.Footnote 123 The next year Schwanda premiered as ‘first novelty of the season’ on 7 November 1931, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Sung in German under the direction of Artur Bodanzky, the cast included experienced Wagner interpreters such as Friedrich Schorr (Švanda) and Maria Müller (Dorotka), who had already sung this part in the 1929 production at the Staatsoper in Berlin. According to the New York Times chief music critic Olin Downes, Schwanda was ‘by far the most successful novelty to be produced by that company in several years’.Footnote 124 In his review, he also pointed out parallels with Prodaná nevěsta and even Rimsky-Korsakov, particularly in the overture and in motifs throughout the opera. Omitting a nationalist or exoticist discourse, Downes saw the quotations or ‘references’ as intentional and described the libretto as farcical. Although he did not classify the opera as ‘first order’ and perceived inconsistencies of material and style, he emphasised its sophistication, complicated technique and counterpoint, concluding that ‘the sum total is entertainment and a lively, melodious score … He has done a very workmanlike and amusing job.’Footnote 125

In these years Schwanda became the most widely known Czech opera after Smetana's Prodaná nevěsta. Between 1927 and 1931, it was performed about 2,000 times in Czech or German as well as in other translations.Footnote 126 By 1939 the performances had doubled to 4,000 and included productions in more than twenty languages, even rare ones such as Swedish.Footnote 127 Rapidly achieving great success, it was performed throughout the world. Like Prodaná nevěsta it came to represent a work ‘capable of standing on its own, unbound to a specifically Czech context’.Footnote 128 What then happened to the initial anti-Semitic criticism? In fact, none of the reviews after the Prague world premiere ever brought up Weinberger's heritage – perhaps a sign that it was not widely known, or that it was widely accepted outside Prague.

A national opera for which people?

In late 1933 musicologist Wilhelm Altmann reported that while in 1929/30 Schwanda had seen nearly 500 performances in Germany, these were now reduced to twenty-seven (down from fifty-four).Footnote 129 Though he cautiously did not share or analyse the reasons, in the same article he referred to Heinrich Marschner's Der Templer und die Jüdin as ‘stofflich nicht erwünschte Oper’ (undesirable opera subject matter), subtly alluding to the rise of Nazism that had affected Jewish-associated repertoires being brought to the stage. Indeed, with Hitler's rise to power in January 1933, anti-Jewish actions soon followed, intended to cleanse German culture of ‘degeneracy’. In April, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was put in place, which barred all Jews from civil service jobs – these included musicians employed at the opera houses; with the establishment of the Reich Culture Chamber in September the same year the ban of Jewish composers took its course. By 1934 Schwanda was almost completely absent from German programmes, with only three performances (down from twenty-seven).Footnote 130 In Germany, where anti-Semitism had been strongly on the rise, censorship replaced criticism.

After the debacle surrounding the first Czech version, it was perhaps surprising that the opera returned to the Národní divadlo in Prague in 1933, but not to the Neues Deutsches Theater. In the 1930s, the German minority of Czechoslovakia had begun to transform into a pro-Nazi force.Footnote 131 And paradoxically Weinberger himself got entangled in the Czech–German conflicts happening in Prague.Footnote 132 In March 1937 a new production of Schwanda by the Wiener Staatsoper was announced.Footnote 133 But with the annexation of Austria the subsequent year, Weinberger's works disappeared from the programmes there altogether. With the German occupation of Czechoslovakia soon after, Schwanda's reception was further compromised by Weinberger's Jewish heritage, and there was a preliminary end to performances there. His name was blacklisted, first in Judentum und Musik; mit einem ABC jüdischer und nichtarischer Musikbeflissener and subsequently in the Lexikon der Juden in der Musik, with Schwanda mentioned as his main work and even receiving a separate entry.Footnote 134 However, the Weinbergers had already left for Paris in the autumn of 1938, where Schwanda was still being performed, as it was in England, the Netherlands and beyond. With World War II the work fell into oblivion – a result of the performance caesura it experienced, reinforced by the new Zeitgeist and taste that pervaded the post-war period.

But by 1934, excerpts of Schwanda had begun to appear in Jewish contexts, including performances of the Culture League (a Nazi-controlled cultural ghetto, but also a temporary safe haven for about 2,000 musicians and cultural figures) and for Hanukkah in Frankfurt am Main.Footnote 135 Indeed, the Jewish world began to discover Weinberger as one of its own. In Pult und Bühne, an almanac issued by the Reich Association of Jewish Culture Leagues in Germany, Kurt Singer (co-founder of the League) optimistically included Schwanda among the recent operas that could shape the canon of an opera house.Footnote 136 But Singer's ultimately ‘shattered hopes’ of maintaining German-Jewish culture under Nazism – and/or transplanting it to the United States – were experienced by Weinberger too, and Schwanda disappeared from the repertoire.Footnote 137

In their 2004 study ‘Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust’, William Brustein and Ryan King propose that the highpoint of anti-Semitism between 1899 and 1939 (including geographical variances across Europe) were due to declining economic conditions, increased Jewish immigration, growth of leftist influence and identification of Jews with the leadership of the political left in the decades before the Holocaust.Footnote 138 Their study and comparison of the situations in France, Italy, Romania, Great Britain and Germany confirms their assumptions, but does not quite hold for interwar Czechoslovakia, where the economy was solid and Jewish immigration was stable. However, as previously mentioned, leftist support was lacking, attesting to the ambivalent role of the government under Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. Indeed, if Czech leaders had done little to stop the anti-Semitic campaign in the Czech press in the early years of the First Republic, they had stayed silent during the Weinberger attacks too.Footnote 139 What Michael Riff concludes for the 1890s was perhaps even more valid for the interwar period: namely, that popular anti-Semitism was so virulent among the Czechs that the Jews’ attempts at acculturation were illusive.Footnote 140 And as the case of Weinberger reveals, artists and composers received anti-Semitic responses, especially when their artworks attempted enculturation by way of ethnosymbolic nationalism.

But the moment surrounding Švanda's premiere in 1927 does not merely point to anti-Semitism, it also reflects competing notions of nationalism and its meanings for composers and critics active on the Prague culture circuit (and beyond). There was the nationalism of the Czech critics, who expected composers to give voice to the critics’ particular vision of Czechness and embed it in the international styles prevalent at the time. They (perhaps unintentionally and unknowingly) followed Wagner, not only in ideology but also in rhetoric, while at the same time obliquely rejecting him for being German. Thus, they alluded to the barrier that separated Jews and non-Jews, which prevented Jews from creating genuine German (here Czech) music: Jews could only imitate (Weinberger ‘imitated’ Smetana and Dvořák). Their civic nationalism implies the assertion of an internal homogeneity and thus the exclusion of the ‘Other’.Footnote 141 Indeed, as a complex multi-ethnic nation, Czechoslovakia grappled during the interwar years with considerable insecurities concerning its national identity and rootedness, a feeling of discomfort that was channelled and projected onto the Jews as an imagined homogeneous community – a nationalist anti-Semitism.Footnote 142 This interpretation also affirms Karin Stoegner and Johannes Hoepoltseder's assertion that the twinning of nationalism and anti-Semitism ‘is situated at the very centre of modern identification and the constraint on unambiguously identifying with a group one happens to belong to’.Footnote 143 But there was also the ethnic nationalism of an acculturated Jew, who followed in the footsteps of his Czech predecessors, and whose music had processed and subverted their own nationalism. In other words, Weinberger's opera occupies a liminal space in the phenomenology of nationalism, embodying its dialectics within a mythical and idealised young nation that met a premature end with the rise of Nazi Europe.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to Tristan Willems for sharing with me the many materials he collected while cataloguing Weinberger's manuscripts at the Muzeum české hudby in Prague, to my colleague Jadranka Važanová for her help with the Czech translations and to Christopher Campo-Bowen for his thorough reading and helpful feedback.