Tea was my companion – at first the ordinary black tea, made in the usual way, not too strong: but I drank a good deal, and increased its strength as I went on. I never experienced an uncomfortable symptom from it. I began to take a little green tea. I found the effect pleasanter, it cleared and intensified the power of thought so. I had come to take it frequently, but not stronger than one might take it for pleasure.

—Sheridan Le Fanu, “Green Tea”

In Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 short story “Green Tea,” the Reverend Mr. Robert Lynder Jennings becomes obsessively engaged in a potentially subversive research project on ancient pagans, and finds himself experimenting with green tea as a stimulant to sharpen his mind, boost his productivity, and maintain his stamina through long, sleepless nights bent over books. One day, while riding an omnibus, Jennings sees two piercing deep red eyes staring at him, and gradually realises that they belong to a small black monkey, which was “pushing its face forward in mimicry to meet mine” (23). At first fancying the creature to be the “ugly pet” (23) of a fellow traveller, Jennings attempts to ascertain the monkey's mood, and “poked my umbrella softly towards it. It remained immovable – up to it – through it!” (23–24). Gradually, he becomes convinced of the creature's demonic nature, and this grinning, screeching vision persecutes Jennings for the rest of his days, sitting on his books and interrupting him while he studies, shrieking curses and blasphemies to drown out his prayers, soliciting him to perform evil acts, and finally, commanding him to commit suicide, which he does, slitting his own throat with a single-edged razor. In the final analysis offered by Jennings's physician and confidant, the metaphysical doctor Martin Hesselius, a significant contributing cause to Jennings's nightmarish experience was his gradual self-poisoning by green tea.

This admittedly odd tale has largely been treated sceptically by critics, who are disturbed by the apparent disparity between Jennings's tea related crimes and his horrific punishment. His is seen as a case, in Barbara Gates's words, of a “good man with no very apparent guilt or reason to kill himself” (20), who is nevertheless subject to the “tenuousness of life, its susceptibility to sudden, unsuspected – and seemingly pointless – alterations” (23). Dubbing “Green Tea” an “archetypal ghost story” and Jennings himself an unfortunate victim, Jack Sullivan insists that “the truth is that Jennings has done nothing but drink green tea,” and that “the strange power of the tale lies in the irony that something intrinsically ridiculous can drive a man to destroy himself” (14). Repressed sexual frustrations and crippling religious doubt have also been cited as the primary causes of the apparition of a supposedly Darwinian monkey, which literally separates Jennings from his parish and the rituals of his faith.Footnote 1 The critical substance of the tea, however, which is clearly privileged in the tale's title, remains for these critics a rather innocuous beverage partaken by an unjustly tortured everyman.

Interestingly, both Brenda Hammack and Susan Zieger have focussed more carefully on Jennings's habit of tea drinking by identifying this tortured scholar in their different arguments as one version of the “chemically inspired intellectual in occult fiction” (Hammack 83), who resorts to psychoactive agents in order to enhance mental acuity and offset exhaustion. Certainly, Jennings's aspiration to sharpen and intensify his intellectual powers through the use of green tea forms, as Hammack and Zieger have noted, part of a broader Victorian association between frenetic scholarly activity and drug abuse, and aligns him with a host of artists and writers such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey, Charles Baudelaire, Theophile Gautier, and Edgar Allan Poe, who, dedicated to their vocations, turned in varying degrees to artificial stimulants for creative inspiration. In fact, “everyone who sets about writing in earnest,” Jennings claims, “does his work, as a friend of mine phrased it, on something” (22). However, in categorising green tea alongside alcohol, tobacco, opium, morphine, and hashish collectively as artificial stimulants to a mentally abusive lifestyle, both Hammack and Zieger overlook the more particular social, cultural, and medical contexts of green tea in the nineteenth century, and leave us with the impression that it is indeed a rather poor choice of stimulant for Jennings's purposes, that, as Suzanne Daly has observed, “All in all, ‘Green Tea’ would perhaps make more sense, both to a reader in 1872 and to us, if we replaced the words green tea with opium” (104). Why then, we must ask, did Le Fanu choose green tea and not opium, morphine, or hashish as Jennings's catalyst to spectral visions and self-destruction? What kinds of associations specific to green tea are being brought to bear upon the operations of this beverage in the story? And, finally, what symbolic work does this substance perform in a tale so much concerned with the empirical, and with potential interactions between material and spiritual realms?

This essay examines nineteenth-century medical, scientific, and cultural discourses surrounding green tea in order to demonstrate the complex set of forces peculiar to green tea which are operating upon the Reverend Jennings's body and mind. In so doing, it offers new insights into the contradictory histories and transformative powers of green tea in Le Fanu's tale from a materialist perspective. There is, as Elaine Freedgood has argued, a kind of knowledge that is “stockpiled” in things, which “bears on the grisly specifics of conflicts and conquests that a culture can neither regularly acknowledge nor permanently destroy if it is going to be able to count on its own history to know itself and realize a future” (2). In its movement from China to the British aristocracy to the general populace, green tea came to hold significant and contradictory social, cultural, imperial, and medical meanings and, I want to argue, when deployed in a gothic context it is rendered increasingly sinister as it divests itself of these meanings in devastating ways that disrupt individual and social coherence and destabilise the boundaries between the material and the metaphysical.

I

Narrated in the form of a series of letters to his colleague Professor Van Loo of Leyden, the German physician Martin Hesselius's account of the demise of the Reverend Mr. Jennings has, we are told in the opening pages, been collated and edited by his anonymous secretary, and is dated from “about sixty-four years ago” (6), or, the first decade of the nineteenth century. These layers of embedded narratives and temporalities prompt questions of reliability typical of the gothic genre while self-consciously mobilising an anxious discourse surrounding tea drinking and nervousness prominent in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This was a moment when, as James Walvin has observed, the majority of tea imported to Britain was Chinese green tea – which only lost its primacy when cheaper, black tea from Assam and Ceylon flooded the market in the latter half of the century – and the habit of tea drinking was gradually spreading from the royalty and nobility to the rest of the nation, for whom it was still a novelty. Green tea was, in this period, an object of anxiety that opened the body to dangerous external influences, and a number of contemporary medical treatises on nervous disorders emphatically declared that it should be avoided by all persons with weak nerves. In his 1828 work on diet and regimen, for instance, James Rymer claimed that “all nervous disorders are certainly aggravated by the use of tea,” and that the “internal tremor which it often occasions” is worse in green tea than black (40-41). Elizabeth Lea, the compiler of Domestic Cookery: Useful Receipts and Hints to Young Housekeepers in 1845 agreed, declaring that black tea was more suitable for delicate individuals than green, but that “I have known instances of people being afflicted with violent attacks of nervous head-ache, that were cured by giving up the use of tea and coffee altogether” (184). The culprit in this process of consumption and gradual self-destruction was, it seems, often believed to be the stomach, an organ peculiarly vulnerable to such stimulants:

The swilling of the stomach is a great evil; especially if the fluid be acrid or stimulant. It is the quantity more than the quality of tea, which so frequently debilitates the stomach; not but that strong green tea possesses a sedative virtue, and that to a very considerable extent; but when the stomach is distended with a pint or more of fluid, its functions are oppressed, and a debility of its tone or of its elasticity ensues. (Richards 110)

Susceptibility to the effects of green tea is constructed as a signifier of a heightened state of nervousness and a delicate constitution unused to such modes of stimulation. It is a sensitivity which, I suggest, must be read in relation to social and financial circumstances. In her unfinished novel, Sanditon (1817), for example, Jane Austen draws on this figure of the overwrought, over-sensitive tea drinker in her satirical treatment of the hypochondriacal Arthur Parker. Idle and overweight, Arthur shares the capricious state of nerves of Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice (1813). Declaring himself to be suffering from rheumatism and nerves, his convenient “enjoyments in Invalidism” are, we are told, less than “spiritualized,” as he is determined to have “no Disorders but such as called for warm rooms and good Nourishment” (339), indulging his predilections for wine, strong cocoa, and hot buttered toast while expressing his horror that Charlotte Heywood has dared to drink two cups of green tea in one evening. “What nerves you must have! How I envy you!” (339) he declares, insisting that green tea “acts on [him] like Poison,” for he is of such a nervous disposition that even the smallest amount would paralyse the whole of his right side within five minutes (339). Green tea becomes, for Arthur, a vehicle of manipulation within the domestic sphere and an emblem of his pathological fragility and self-importance. Charlotte's dry response that “I dare say it would be proved to be the simplest thing in the World by those who have studied right sides and Green Tea scientifically and thoroughly understand all the possibilities of their action on each other” (339), is mocking not only of Arthur's hyperbolic attempt to garner her sympathy, but also of the contributions of medical and scientific communities to studies on the pernicious effects of tea drinking. This self-indulgent level of nervous susceptibility, Austen implies, is strictly limited to the leisured middle and upper classes.

The class-bound nature of ailments such as Arthur Parker's finds an interesting parallel in Beth Kowaleski-Wallace's argument that the complaints put forward about the dangers of tea drinking amongst the lower classes in the late eighteenth century were symptomatic of fears surrounding the erosion of the working-class lifestyle and its levels of productivity. Tea represents, Kowaleski-Wallace argues, a threatening “‘taste’ for more than is provided for by one's station, an unsettling desire for a lifestyle one is not born into” (138), which effectively weakens the British social fabric as the working classes, often gendered as female in such constructions, seek to imitate their betters, and in so doing waste not only their money but their time. Tea drinking, the time and expenses it consumes, and the gossip and idleness it potentially engenders, should, it is made clear, remain within the province of the wealthy. Further, if tea in general is seen as a symbol of luxury and indolence, then a nervous reaction to tea represents an (at times contemptible) emblem of that genteel life. In a light-hearted manner very much akin to Charlotte's treatment of Arthur, such a reading of the nervous destruction wrought by green tea also fuels Miss Matty Jenkyn's plaintive entreaties in Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford (1851) that her customers not buy the green tea in the little teashop she sets up in her parlour – a room inextricably intertwined with representations of Victorian middle-class domesticity. Miss Matty's panic, “running [green tea] down as a slow poison, sure to destroy the nerves, and produce all manner of evil” (46), is clearly meant to be a comical treatment of a discourse surrounding tea drinking prevalent earlier in the century, which nonetheless affirms a correlation between tea drinking and the more delicate, privileged members of British society.Footnote 2

Amongst those sensitive and nervously constituted figures of the middle and upper classes overindulging in the teapot, there is, I would suggest, a peculiar class of tea drinker whose consumption of green tea in particular becomes representative of a scholarly temperament and a tendency towards excess and obsession. In his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in serial form in the London magazine in 1821 with the subtitle “Being an Extract from the Life of a Late Scholar,” Thomas De Quincey deliberately constructs himself as a melancholic student and philosopher who suffers from ill-health, intellectual torpor, and unbalanced emotions, drawn to opium as a source of “exquisite order, legislation, and harmony” (40). However, alongside his all-consuming opium addiction, De Quincey, much like Le Fanu's protagonist, also maintained a habit of tea drinking during his nocturnal studies, “from eight o'clock at night to four o'clock in the morning” (60), and he even notes in passing that “some people have maintained, in my hearing, that they had been drunk upon green tea” (43). Tea, for De Quincey, is a kind of tonic rather more subtle and sophisticated than opium; it is not effective for all who use it, but it is of particular benefit to the sensitive and delicately constituted scholar: “Tea, though ridiculed by those who are naturally of coarse nerves, or are become so from wine-drinking, and are not susceptible of influence from so refined a stimulant, will always be the favourite beverage of the intellectual” (60). Again evoking an ideology in which the more highly strung nerves of the upper classes become the seat of intellectual advancement and social refinement and superiority, De Quincey claims that the heightened sensitivity to external and internal stimuli typical of the artistic sensibility extends even so far as to include tea.

De Quincey's claim for the subtle but salutary effects of tea upon finely-strung nerves during periods of intense mental exertion was echoed in the more specific context of green tea in an 1827 pamphlet dedicated to Some Observations on the Medicinal and Dietetic Properties of Green Tea by the medical practitioner William Newnham. An infusion of green tea, Newnham claimed, might have varying effects on the heart, mind, and nerves, dependent on the state of these systems at the time when the beverage is taken. Nevertheless, he found the substance to be particularly useful in the case of afflictions arising from the intense and long-continued application of the mind to any object of literary research. At such moments, he claims, green tea has extraordinary powers to recruit the flagging energies of both body and mind:

There are few who have not experienced its salutary influence under such circumstances, in soothing the irritation, which is a consequence of over-action – calming the nervous system – invigorating the animal frame – refreshing the jaded spirits – clearing the ideas – brightening the faculties – and so far recruiting the energies of the brain, as to render it again a willing and obedient organ to the indefatigable and immaterial intelligence which presides over its functions. (9)

This marked association between the student and the teapot can, it seems here, confer a degree of dignity and gravity both to the scholar and to the mental labours at hand. Thus, the prolific English writer E. V. Lucas wrote in his piece “Concerning Tea” in the Cornhill Magazine as late as 1897, “taking them as a whole one may say that no class of men make such good tea as undergraduates,” and, further, that these “tea connoisseurs” are temperamentally suited to the task, for “there is something Asiatic about the reserved undergraduate – and today the conscious ones are all reserved – that stimulates tea to do its best for him” (72). Trouble inevitably ensues, however, when the symbiosis of this relationship is disrupted by excess, which manifests itself in the form of physical exhaustion, over-excitement of the mental faculties, and a corresponding over-indulgence in green tea. “Once a man looks upon tea when it is green,” Lucas declares, “his fate is sealed,” for it has “shattered many a nerve” (76). It was in this vein that green tea made its appearance in the educational overpressure debates of the 1870s and 1880s, as nervous exhaustion, loss of appetite, and digestive disorder, alongside what Dr. G. E. Shuttleworth referred to as “a tendency to substitute nerve-titillating tea for a more nourishing diet” (529), were often noted in the medical and more general press as appalling by-products of the British forcing system. In 1878, the renowned British physician T. Clifford Allbutt opened the first issue of Brain: A Journal of Neurology with a piece entitled “On Brain Forcing,” in which he condemns the act of cramming students in elementary schools, which he argued placed a terrible strain upon students’ bodies and minds, prompting them to turn, amongst other things, to green tea:

The village grocer's son goes to ‘theological college,’ and sits up by night over his “Evidences” with green tea in his blood and a wet cloth about his brows. The Gardner's daughter pulls roses no more, and has become a pupil-teacher; she is chlorotic at sixteen, and broken-spirited at twenty. (61)

Cultural and social fears surrounding the abuse of green tea by overworked and exhausted students at an elementary school level were reinforced by medical case studies of the over-imbibing of tea amongst a class of older, more impassioned, and noticeably always male scholars, who were supposed to be almost excessively devoted to their work. John Cole, a distinguished member of the Royal College of Surgeons, for example, submitted a case to the London Medical Society in 1833 in which a young author, while temporarily engaged as a parliamentary reporter, developed the practice of rising at noon and dedicating the greater part of his day and night to writing, “drinking very strong green tea for five or six hours together” so that, “it commonly happened two or three times a week that he was found in a state of insensibility on the floor” (277). Similarly, the Irish physician William Stokes's medical treatise on the diseases of the heart contains a section on the effects of tea which relates the case of a middle-aged gentleman accustomed to pass a considerable portion of his night in scientific and literary labours, who customarily drank large quantities of tea throughout until at length he became subject to paroxysms of quick and vehement action of the heart, intense precordial distress, and “a painful sense of impending death” (535). Earlier, in his 1817 pamphlet on “Some Brief Notices of the Deleterious and the Medicinal Effects of Green Tea,” the senior physician Edward Percival offered a series of studies on the abuse of tea, including one very dramatic instance furnished him by a Dr. Harvey which similarly evidenced both the physiological and psychological effects of green tea drinking:

I happened to answer the door myself, as all my domestics were out, looking at some public spectacle. He appeared to me to be actuated by great terror; and upon my asking him what was the matter, he said, ‘I have called upon you to request you would let me in, and allow me to die in your house.’ (12)Footnote 3

Further investigation, Percival reports, reveals that the patient had a barely discernible and extremely irregular pulse and that he had drunk “a great deal of strong green tea during the whole of the preceding night” (12). He, too, had fallen victim to the temptations of intensifying his intellectual powers through the use of green tea.

The sensitive and somewhat emotionally unstable intellectuals in these cases are shown by their doctors as being drawn to the heady delights of green tea in order to maintain an already unhealthy and immoderate lifestyle that threatens to strain their mental faculties to an extreme in the pursuit of artistic production. The intense concentration demanded by prolonged reading and writing induces a kind of entranced or addicted state that potentially leads to derangement of the mental faculties. Like these historical figures, the Reverend Jennings has indulged in an intemperate lifestyle, and demonstrates an imbalance of exercise between body and brain as well as the typical scholarly habit of neglecting his meals. He is, even before taking up green tea drinking, so obsessively committed to his project that, he confesses, “I was always thinking on the subject, walking about, wherever I was, everywhere” (21), inescapably drawn to his subject of study at the expense of his social and clerical duties. In keeping with the figure of the intellectual as already unbalanced or diseased by the very nature of his profession, Jennings regards himself as “thoroughly infected” (21). There is, Jennings hypothesises, a kind of mental boundlessness to such all-consuming scholastic activity, which holds significant psychological dangers lest the mind becomes lost within a complex labyrinth of premises and postulations, and “we should grow too abstracted, and the mind, as it were, pass out of the body, unless it were reminded often of the connection by actual sensation” (22). Green tea thus offers Jennings a physical corollary to the excesses of cerebral stimulation, supposedly supplying that “material waste” (22) left by an over-active mind in danger of losing its connection to the material world, and reminding the scholar that the act of learning must be an embodied experience. However, it will ultimately prove a further disruption to the flow of cerebral fluids rather than a moderate counter-balance to them. The use of green tea thus becomes both a cause and a symptom of the intellectuals’ disease.

II

The precise mechanisms by which excessive green tea drinking might cause nervous and mental diseases are never fully explained in the nineteenth-century medical and scientific press. The detrimental effects of tea were, however, subjected to experiment and analysis from at least as early as 1767, when it was recorded that Dr. Edward Smith conducted a series of tests in Edinburgh from which he argued that an infusion of green tea first diminished and then finally destroyed vital properties of the living tissues of the human body. The eminent Scottish physician Dr. William Cullen, in his Treatise of the Materia Medica (1789), also argued that scientific experiments had proven that an infusion of green tea “has the effect of destroying the sensibility of the nerves, and the irritability of the muscles” (310). Other experiments, he claimed, demonstrated that green tea gives out in distillation an “odorous water,” which he deemed a powerfully narcotic and sedative substance (310). Later, the chemist and physician Dr. Thomas Beddoes conducted a number of trials in which he applied a strong decoction of green tea to hearts just removed from living frogs and toads. “In all our experiments,” Beddoes concluded, “tea proved as quickly poisonous as laurel water, opium, or digitalis; and in some, even more so” (37). With the clear caveat that there was no certainty that the hearts and nervous systems of humans would be affected in the same way as the removed organs of amphibians, Beddoes nonetheless draws on this research in his warnings against the practice of tea drinking amongst adolescent girls in boarding schools – another class of fragile scholars in whom mental over-stimulation and exhausted nerves were deemed particularly dangerous – in his collection of essays on health collectively published under the title Hygeia in 1802. Dr. John Burdell, a surgeon dentist in New York, conducted similar experiments in the 1830s on other animals including birds, rabbits, and cats, and witnessed their painful spasms and finally their deaths, with the subsequent reflection that “how analogous this to the case of many a human sufferer, who is thus, though unwittingly, a self-inflicter of misery” (Alcott 54). Tea, in Burdell's view, was an insidious kind of poison in its gradual but nonetheless certain destruction of its devotees who, he declared, were, in a fashion comparable to Jennings, “filling [their] own flesh with anguish, and committing slow but certain suicide” (Alcott 54).

Nineteenth-century medical and scientific warnings of the dangers of excess and self-harm through green tea seemingly posit the culturally constructed identity of the nervous, overstrained scholar, and the use and abuse of green tea as a means by which society may produce and affirm that construct. The symptoms of what the American educator and physician William Andrus Alcott referred to as “the tea disease” (38) were generally agreed by these experimenters and their followers to include an initial excitement or euphoria followed by violent pain in the head, vertigo, palpitations of the heart, and enfeebled action, often inducing a syncope.Footnote 4 Given that such symptoms are staples of Victorian sensation and gothic literature, it is not surprising that medical facts and fears surrounding green tea drinking provided an anxious site for the medical and the imaginative to disrupt and inform one other in fictional explorations of the body's physiological and psychological responses to external sensation. In Edgar Allan Poe's short story “The Oblong Box,” first published in 1844, green tea forms the basis of a potentially factual, rational explanation put forward in opposition to more fantastic possibilities. This story, told from the perspective of an unnamed narrator, of his journey by packet-ship from South Carolina to New York, recalls his fearful suspicions surrounding a mysterious oblong box, six feet long and two and a half feet wide, which his fellow passenger Cornelius Wyatt has brought on board. Every night, the narrator hears – or rather thinks he hears, “if indeed the whole of this latter noise were not rather produced by my own imagination” – the sounds of the box being pried open with a muffled chisel and mallet, followed by a “low sobbing, or murmuring sound, so very much suppressed as to be nearly inaudible” (312). Our narrator's evident distrust of his own senses is derived from the fact that he has recently been suffering from nervousness, and he “drank too much strong green tea, and slept ill at night” (311). The use of green tea in this context is, as I argued in the previous section, part of a familiar and self-conscious construction of the protagonist as temperamentally nervous and exceptionally sensitive to external stimuli, but, by drawing on medical discourses surrounding green tea in a narrative of the grotesque and potentially supernatural, it also casts doubt upon the narrator's mental state and auditory perceptions.

Like the sounds emanating from the demonic monkey, which Jennings claims “sing” through his head rather than entering it through his ears in the form of vibrations, the sobbing and sighing that Poe's narrator perceives are, he reflects, more “like a ringing in my own ears” (312) – a complaint comparable to the dizziness, headaches, and ringing in the ears noted by recorded sufferers of the fearful tea disease. The narrator's reflection that “it must have been simply a “freak of my own fancy, distempered by good Captain Hardy's green tea” is not presented here as a particularly unusual or frightening concept, but as a known and genuine medical possibility, which paradoxically undercuts his hysteria while demonstrating his own psychological vulnerability. In the final exposé, when it is made clear that Cornelius Wyatt's wife was dead, embalmed, and lying in the box to be transported home for burial by her distraught husband, the narrator blames his own series of misunderstandings on “too careless, too inquisitive, and too impulsive a temperament,” but that his over-indulgence in green tea fuelled this nervousness, disrupted the workings of an over-stimulated mind, and potentially induced auditory hallucination is implied, I think, in his final confession that “there is an hysterical laugh which will forever ring within my ears” (316). Green tea is both a site and a tool for anxiety and unreliability in Poe's story.

Throughout the nineteenth century, conjecture as to what specifically constituted tea's dangerous properties ranged from its having been roasted in copper pans, to the presence of chemical salts and colouring substances, to the only partial curing of the leaves in green tea (as opposed to the more complete fermentation of the leaves in black tea), so that it retained more of the elements of its raw, natural state. Tea, writes the English physician Robert Hooper in his medical dictionary, is a narcotic plant, “On which account the Chinese refrain from its use, till it has been divested of this property by keeping it at least twelve months. . . . When taken too copiously, it is apt to occasion weakness, tremor, palsies, and various other symptoms arising from narcotic plants” (809). It is tempting to speculate that there is, in such concerns, a sense of green tea as a raw and primitive substance that was increasingly being taken into and exerting its unknown or uncontrollable effects upon the British body. The tea itself emerges from a complex nexus of British economic and political power relationships with China, and an increasing dependence upon Chinese commodities which gives additional layers of meaning to the anxiety surrounding British dependence upon or addiction to this narcotic plant, which was being naturalised in Britain far more subtly and completely than opium. The Otherness of this object, which is gradually being interwoven with British domesticity, is being held in tension with the troubling social and cultural Otherness of its exotic source culture. Like the pagan rites with which the Reverend Jennings is absorbed in Le Fanu's tale, there is something foreign and vaguely malevolent about this substance, which has not yet been fully understood and taken under British control. In its gradual naturalisation, it represents a destabilising or re-defining influence upon British culture and identity. Jennings's religious studies become a kind of intoxicating dependency in themselves, and it is important here to note that just as drinking green tea opens the British body and mind to dangerous influences, Jennings’s mind is in a sense invaded and taken over by subversive reading materials, which he admits are “not good for the mind – the Christian mind, I mean,” and yet still hold a “degrading fascination” to him (21).

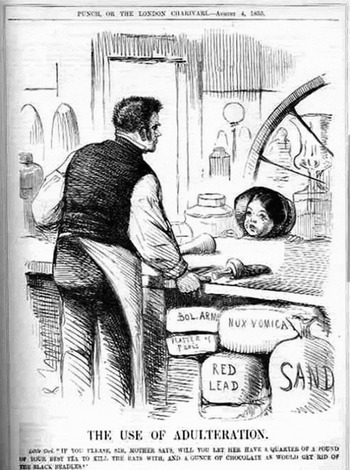

Alongside such vague fears of the provenance of the substance, the tea industry was plagued by public fears of tea's actual contents. Adulteration, the practice of mixing tea leaves with chemicals or of treating the leaves to make them appear of a higher quality or a brighter colour, was seemingly widespread at home and abroad throughout the first half of the century. Green tea in particular was routinely dyed with Prussian blue and magnetic iron to give it a “better” appearance, leading to fears throughout the century that the chemical contents of a tea pot rendered every cup of tea a great personal risk. Articles with titles such as “Poisonous Breakfast Beverages” and “Tea as a Poison” appeared throughout the early and mid-century, while speculation took place in the Lancet on cases of lead-poisoning which may have derived from adulterated tea drinking. An anonymous but self-proclaimed “enemy of fraud and villainy” (6) published his Deadly Adulteration and Slow Poisoning; or, Disease and Death in the Pot and Bottle in 1830, dramatically insisting that the adulteration of food and drink, of which tea played a significant part, was responsible for “the loss of tens of thousands of human lives every year” (6). In August 1855, Punch mocked this convergence of cooking and chemicals with a satirical sketch of a young girl at a grocery counter saying, “If you please, Sir, Mother says, will you let her have a quarter of a pound of your best tea to kill the rats with, and an ounce of chocolate as would get rid of the black beadles” (Figure 1). The clear implication here is that, alongside the increasing distance between producer and consumer being facilitated by the processes of industrialisation, urbanisation, and capitalism, the threat of adulteration is present, albeit comically, at the very heart of the Victorian middle-class family and its lifestyle.

Figure 1. “The Use of Adulteration.” Engraving, from Punch (4 Aug. 1855): 47.

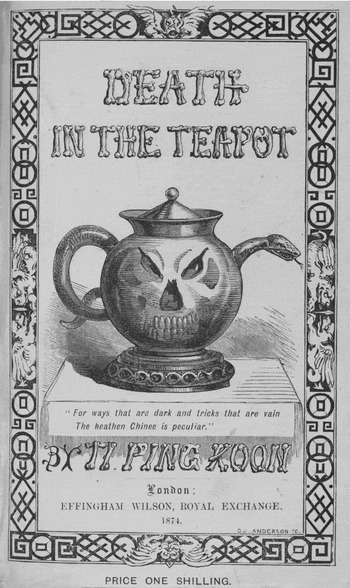

Public anxieties about the adulteration of food and drink as well as less clearly articulated uncertainties regarding tea's sinister Oriental origins were brought together to inform the small pamphlet entitled Death in the Teapot by Ti Ping Koon, which was published in London in 1874. Though it explicitly cautions its readers against taking any Chinese tea which has a pellicle floating on the surface of the infusion, lest gypsum or Prussian blue should have been used in its manufacture, it is rather more wary as to the underlying reasons for this kind of practice. Its opening declaration that “the public are being slowly poisoned by the daily use of an infusion, the ill effects of which, though not immediately felt, must baffle in their cumulative action the physician as well as the patient” and further that this “insidious and widely-spread evil demands instant investigation” (1), makes a claim for adulteration as a large-scale and long term problem of social health; yet the word “evil” is quite telling here, particularly as it follows so immediately from the pamphlet's title page (Figure 2). The striking picture on yellow cover papers of a teapot with a lid shaped like a Chinese-style hat, containing a sunken, skull-like face with what is clearly meant to be interpreted as Chinese eyes, and captioned with the phrase, “For ways that are dark and tricks that are vain, the heathen Chinese is peculiar,” is entirely unambiguous as to the origins of this insidious evil. The snake's head supplying the pot's spout further emphasises the foreign treachery implied in the act of adulteration, and the poison, or venom, contained in the final product. While there are clearly reasons for the adulteration of tea relating to commercialisation and the forces of industry, there remains nonetheless a sense of the potential dangers brought upon oneself by dabbling in a foreign market and, in this case, trading with the Chinese.

Figure 2. Ti Ping Koon, Death in the Teapot (London: Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange, 1874). Title Page. Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

III

In “Gender Trouble as Monkey Business: Changing Roles of Simian Characters in Literature and Film Between 1870 and 1930,” Julika Griem situates the late nineteenth-century literary fascination with ape and monkey figures within the context of a “late-colonial moment of a confrontation with an uncannily similar simian double as a return of energies that have to be repressed” (73). Victorian “monkey stories” such as Le Fanu's “Green Tea,” Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde (1897), Rudyard Kipling's “The Mark of the Beast” (1891), and Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World (1912) and, later, his story “The Creeping Man” (1923), are each driven, Griem argues, by the overwhelming impulse to contain the basic, often sexualised, animal influences of the ape-like double, “while simultaneously registering the futility of this project” (74). In the case of the Reverend Mr. Jennings, whose story was published only a year after Charles Darwin's Descent of Man (1871), it is easy to interpret the monkey in psychological terms, as Griem certainly does, as a symbolic figure of guilt and shame, produced by the conscious or unconscious workings of self-doubt, self-censorship, and sexual repression within a clergyman indulging his passion for the study of non-conventional religious practices and philosophies. However, there is notably little evidence of Jennings's religious doubt beyond the unstable metaphor of the monkey, and it is important to note that this is only one of an array of material, spiritual, and psychological possibilities put forward throughout the tale, each of which jostles against and disrupts the others in a manner entirely in keeping with the widespread scientific, cultural, and religious instabilities and burgeoning alternative philosophies that marked late nineteenth-century Europe.

Le Fanu's self-conscious turn to the past throws into relief, from the vantage point of 1872, the dangerous ambiguities of everyday, domesticated objects such as tea in a constantly changing world, and forms part of his examination of the ongoing multiplicity of often contradictory meanings that such objects accrue. The use of tea as Jennings's particular substance of choice is not, as it may first appear, inexplicable; rather, it is in keeping with his status as a tormented intellectual seeking constantly to expand his understanding, and with the discourses of knowledge constructed around tea both by early nineteenth-century anxieties surrounding China and by medical and scientific practice. Tea was, in these early decades, regarded as a suspicious, foreign substance, entering the British body politic from China and destabilising the British sense of political, cultural, and financial autonomy as well as its internal coherence. It was a potentially threatening, disruptive force within social and domestic spheres.Footnote 5 Jennings may simply be unknowingly poisoning his body with a suspicious, adulterated product from the East that causes him to hallucinate, a decidedly sinophobic possibility that was clearly to be feared at the time in which Le Fanu's tale is set and one that is potentially operative within the story in the form of Lady Mary's inexplicable anxiety and reported earlier quarrels with Jennings over the subject of his green tea drinking. The “heathen Chinese” may well have employed his dark ways in producing and marketing this product and therefore be held responsible for Jennings's terrible physical and psychological ordeal. Ultimately, however, the tale itself is not conclusively sinophobic. This is only one possible explanation among many and it must be noted that even within this paradigm Jennings is not entirely an unknowing victim of the Chinese and their poisonous commodities. He is quite deliberately and consciously courting that alleged danger by choosing to open his mind and body to the “evil” influences of a demonised Other, and to different, non-Christian worlds of thought and habit. The clergyman's excessive consumption of dangerous pagan ideas by night finds its natural analogue in the overconsumption of Chinese green tea. As Jennings finds himself increasingly drawn into the radical and the unfamiliar, he hovers at the interstices of religious, scientific, medical, and occultist accounts of inexplicable events. The monkey, though not explicitly associated with China in the story, is nonetheless an exotic Oriental creature, and it amounts in this context to a site of the unknown, the Other, and the multiple potential meanings of that Other. It is undoubtedly a “dreadful interruption” (30) in the life and work of a scholarly clergyman and one which seems to possess an “atrocious determination to thwart [him]” emotionally and intellectually, and to distract him from his clerical duties. More than this, however, there is something rather hypnotic about the monkey's presence, which disrupts the normal workings of and inter-relationship between Jennings's mind and body, and undermines all sense of purpose and certainty:

It used to spring on a table, on the back of a chair, on the chimney-piece, and slowly to swing itself from side to side, looking at me all the time. There is in its motion an indefinable power to dissipate thought, and to contract one's attention to that monotony, till the ideas shrink, as it were, to a point, and at last to nothing – and unless I had started up, and shook off the catalepsy I have felt as if my mind were on the point of losing itself. (30)

In his fear lest his overstraining mind lose itself in abstraction, Jennings posits a complicated architecture of the human mind as an unnavigable, infinite, and unpredictable phenomenon productive of or containing multiple selves and identities. Catalepsy is a familiar condition of the haunted of gothic literature, and it clearly represents a state of powerlessness and a heightened susceptibility to external forces and mesmeric controls. In the case of Jennings, it is suggestive of the monkey's power both literally and figuratively to cut him off from any sense of meaning or certainty. Jennings is confused. He is rendered physically and mentally unable to pray and unable to pursue his metaphysical researches.

It has often been noted that periods of rapid scientific and technological advancement have frequently coincided with the emergence of alternative faiths and hermetic societies, as well as a pervasive cultural interest in spiritualism, mesmerism, the supernatural, the occult, and the paranormal. A distinguishing feature of the second half of the nineteenth century was a widespread malaise regarding Christian belief systems prompted by the positivist world views of scientific materialism. Many who turned to new metaphysical systems did so, as Janet Oppenheim writes, in an effort to counter this sense of loss and to recapture “some incontrovertible assurance of fundamental cosmic order and purpose, especially that life on earth was not the totality of human existence” (2). There is then, in this historical moment of fragmentation, an uneven and contradictory co-existence of mystical and materialist modes of understanding, as secularization and disenchantment sit alongside the persistence of traditional beliefs and the emergence of new spiritual cosmologies. It is this rather chaotic blending of past and present scientific, medical, religious, and spiritualist discourses that gives rise to the ultimate indeterminacy of the source of the Reverend Jennings's simian vision in Le Fanu's tale.

A relatively stable and naturalised product within the British domestic sphere by the time of Le Fanu's writing, the more complicated economic, political, medical, and social histories of green tea in the earlier decades of the century renders it an ideal vehicle for an exploration of the instability and inadequacies of conflicting ideological attempts to grasp the unknown. In keeping with early nineteenth-century medical concerns regarding tea's pernicious effects on the digestion and the nerves, Jennings's initial reaction to the monkey's appearance is an attempt to dissipate his agitation by insisting, Ebenezer Scrooge like, that his digestion is “quite wrong” as a result of “sitting up too late” (25) without proper rest or nourishment, and that this vision is but a symptom of “nervous dyspepsia” (26). That the monkey is merely an hallucination induced by overindulgence in green tea is further suggested by its means of communication with him “not by my ears” but rather “like a singing through my head” (31), a complaint comparable to the dizziness, headaches, and ringing in the ears noted by recorded sufferers of the fearful tea disease discussed above. At the same time, however, Jennings's medical consultant Dr. Hesselius hints at the dangerous metaphysical implications of these physiological complaints, assessing his case with remarkable specificity as “the story of the process of a poison, a poison which excites the reciprocal action of spirit and nerve, and paralyses the tissues that separate those cognate functions of the senses, the external and the interior” (37). The intimate connection drawn here between the spirit and the nerve, and the external and interior senses, resonates with the Swedenborgian mysticism deployed throughout the tale, and it renders the status of the black monkey, as pure hallucination or otherwise, tantalisingly ambiguous.Footnote 6 Excessive recourse to green tea, Hesselius writes in his concluding notes, disturbs the quality and equilibrium of the cerebral fluids and, as “the seat of interior vision is the nervous tissue and brain, immediately about and above the eyebrow,” this fluid congestion on the brain and nerves “forms a surface unduly exposed, on which disembodied spirits may operate” (39). Genetics, too, play a role, as Jennings's suicide, as opposed to his mysterious encounters with the monkey, is, according to Hesselius, the inevitable result of hereditary mania.

Jennings is suffering, then, either from indigestion, the dreaded tea disease and its associated destruction of the nervous system, a profound mental delusion, an accidental clairvoyance, the return of repressed desires and crippling doubts, a congenital suicidal impulse, or a spiritual affliction. Ultimately, despite the doctor's initial promise of an explanation, there is insufficient evidence for the reader to affirm or discard any of these possibilities. None of these alternatives is incontestably “true,” and it is this indeterminacy which exposes the limitations of medical science, religious institutions, and the human sensorium by raising the possibility of seeing and hearing beyond the usual sensory thresholds and by positing the kinds of phenomena that may exist beyond or beneath the conscious mind. Interestingly, in his final observations, Hesselius tells us that Jennings's case is far from singular. He has in fact met with, and successfully treated, 57 instances of its kind, and, he declares, had Jennings not despaired and suicided, “I should have cured him perfectly in eighteen months” (38) simply by means of the application to his forehead of iced eau-de-cologne, a supposedly powerful repellent of the nervous fluid. While there were indeed nineteenth-century precedents for the claim that eau-de-cologne might reduce fever, delirium, and headaches, Hesselius's diagnosis posits not only a need for moderation and balance in the employment of a counter-effect to the tea, but it suggests that Jennings's sufferings are at least somewhat routine, and that the inability to comprehend fully the fundamental mysteries of existence and the human mind is ubiquitous and frequently crippling.

Fifteen years after the publication of “Green Tea,” Isabel Gordon, the governess and eventual morphinomaniac in Richard Pryce's sensational novel An Evil Spirit (Reference Pryce1887), is interrupted by her employer, Mrs Carruthers, as she self-injects in her room, and Mrs Carruthers endeavours to enlighten her as to the dangers of drug addiction by giving her a little book to read. Though unnamed, this brief narrative is, we are told, “the story of an over-worked curate, who got into the habit of drinking the strongest green tea, to keep himself awake at midnight studies,” until “so binding did his habit become, that he found it impossible to break the chains, even though his brain began to give way” (85). Relocating “Green Tea” from its earlier culture of subversive tea drinking to a broader cautionary discourse surrounding overwork and substance abuse in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, Mrs Carruthers once again renders Jennings's afflictions and weaknesses commonplace in this particular historical and cultural moment. Isabel herself is cast in this way as a more recent, female iteration of the nervous Reverend Mr. Jennings and, on the verge of collapse without the artificial vitality induced by morphine, she even begins to see Le Fanu's monkey as she lies awake and suffering in her room. Isabel's engagement with the tale is not only conceptual and imaginative; it is also physical, as she becomes entirely unnerved, overcome by exhaustion, and starts at every sound lest “some terror such as the tea-drinker's ape should come up and take up its hideous abode in my life” (92). Isabel recounts her steady habituation through the pages of her diary:

Then the darkness took shape about me and became full of terrors – things nameless, vague, intangible, but hideous as the foulest imaginations of hell. I could not sleep, I was too tired, and more than once the tea-drinker's ape came and gazed at me and disappeared. Ah, my drug! My drug! With you I could defy these things and sleep! (95)

In her reading of “Green Tea,” the highly mutable state of this curious and responsive reader allows past fictional and present “real” worlds to merge in Isabel's consciousness, as she performs and experiments with the role of the addict through the medium of narrative as well as that of the hypodermic needle. Finally, her intense psychological and physiological response to Le Fanu's tale ironically drives her back to morphine as a means of mental escape from the imagined horrors of the grinning ape. The re-imagined and re-presented monkey becomes for her a kind of demonic mocking double, an avatar of the pains of withdrawal, and the personification of her mental and physical torment. It is, in this late Victorian application of the tale, a declaration of the self-destruction and premature bodily and mental decay inherent in excess – even in excess intellectual preoccupation or tea drinking – which resonates with medical case studies and supposedly leads inevitably to individual degeneration and social collapse.

When the Reverend Mr. Jennings turns to green tea as a “soothing companion” (22) to his nocturnal researches, he is upholding a long tradition of scholarly tea drinking that ever verges on the dangers of excess and addiction. Le Fanu's tale might thus be read as a marker of Jennings's delicate constitution and highly susceptible nature, and as a rather hyperbolic warning against long-term recourse to hallucinogens. However, an examination of the social, economic, and medical history of green tea in nineteenth-century Britain reveals its ambiguous status as an exotic, other, and potentially medically dangerous commodity in the early decades of the century, and the array of unstable associations that this brings into the text. In its gradual accretion of meanings and possible effects throughout Le Fanu's tale, green tea, like the hallucinatory monkey itself, disrupts the psychological coherence of the individual and blurs the boundaries between the material and the spiritual, and the subjective and the objective, while exposing the limitations inherent in all human constructions of knowledge.