How do rights matter in schools? One answer to this question suggests that Americans increasingly look to the “realization” of legal rights to solve racial and ethnic segregation, inequality, and injustice in educational contexts (Reference ArumArum 2003). A deep commitment to this approach underlies the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and other landmark Supreme Court decisions, such as Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District in 1969 and Goss v. Lopez in 1975, which expanded students' rights with respect to freedom of expression and the right of due process for disciplinary actions in public schools, respectively.

A very different picture of legal rights in contemporary American society emerges from studies of legal mobilization outside educational contexts. Multiple generations of researchers have demonstrated that American adults rarely turn to lawyers or the courts when they define experiences as rights violations, instead taking a range of actions apart from law or absorbing perceived wrongs without overt response (Reference BaumgartnerBaumgartner 1988; Reference BlackBlack 1983; Reference BumillerBumiller 1987, Reference Bumiller1988; Reference CooneyCooney 1998; Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998; Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–81; Reference FriedmanFriedman 1985; Reference FullerFuller et al. 2000; Reference GalanterGalanter 1983; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81; Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974). This paradox—between legal rights as a sought-after guarantee of social justice and legal rights as a little-used means of redress in the face of social injustice—is especially apparent for socially disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups. Such groups have collectively invested the most in attaining legal rights, especially civil rights, as a means of redressing social injustice in American society, but they are also relatively unlikely, especially at the individual level, to invoke legal rights when faced with perceived rights violations (Reference BlackBlack 1976; Reference BumillerBumiller 1987, Reference Bumiller1988; Reference CurranCurran 1977; Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003; Reference Mayhew and ReissMayhew & Reiss 1969; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81).

Much of the law applied to U.S. students over the past half century has been intended to benefit nonwhite youth, but to date there has not been empirical research on the mobilization of rights among youth. In this article, we explore the paradox of rights and race in high schools by examining whether and how students who self-identify as white and nonwhite mobilize their rights in response to both hypothetical scenarios and self-reports of actual rights violations involving discrimination, harassment, freedom of speech, and disciplinary procedures.Footnote 1 By examining both what individuals claim they would do and what they report they actually did in response to rights violations, we examine the relationship between hypothetical and actual rights mobilization, two aspects of the law-in-action that are rarely investigated in the same study. These aspects of mobilization, we believe, are crucial for understanding the paradox of rights and race in schools and other contexts. We base our analyses on surveys of 5,461 students in California, New York, and North Carolina, and in-depth interviews with students and school personnel that make up part of our broader School Rights Project (SRP)—a multimethod study of law and everyday life in American high schools.

We conceptualize responses to rights violations as a multidimensional process involving a variety of actions that may or may not include law in any direct way. How youth interpret and respond to situations as rights violations is integrally bound up in the ongoing interactional dynamics through which they define who they are and where they belong in the social fabric—their self-identities (Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003; Reference Oberweis and MushenoOberweis & Musheno 1999). During adolescence, self-identity becomes especially salient for youth and a key lens for interpreting their own and others' actions (Reference EriksonErikson 1968).

Of particular importance for the normative domains we examine are self-identities related to the social categories of “youth” and race and ethnicity.Footnote 2 Adolescence is a time when youth develop an acute sense of how formal rules and procedures, especially in schools, influence their lives (Reference Fagan and TylerFagan & Tyler 2005). To the degree that youth identify as members of socially disadvantaged ethnoracial categories, they can become attuned to everyday ethnoracial injustice, including disparate treatment of white and nonwhite youth in security and disciplinary procedures by school authorities (Reference KupchikKupchik 2009; Reference Welch and PayneWelch & Payne 2010). Youth also can become aware of societal “myths” about the efficacy of law and rights for achieving ethnoracial justice (Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974). Youth identity is thus intimately linked with the sociocultural processes of forming and acting on “commonsense understanding[s] about how law works”—legal consciousness (Reference NielsenNielsen 2004:7; see also Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998; Reference MerryMerry 1990).

In the next section we develop our notion of legal mobilization as a multidimensional process and then, in a following section, suggest a number of hypotheses about the relationships between youth, ethnoracial self-identity, and perceptions of and responses to rights violations. We then describe our survey and qualitative methods. Our findings interlace quantitative patterns from our survey results with representative excerpts from in-depth interviews with youth and adults. We conclude by suggesting some theoretical implications of our work for the interplay of youth legal mobilization, self-identity, and racial and ethnic inequality in schools.

Conceptualizing Legal Mobilization

Legal mobilization refers to the social processes through which individuals define problems as potential rights violations and decide to take action within and/or outside the legal system to seek redress for those violations (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference BlackBlack 1973; Reference BumillerBumiller 1987, Reference Bumiller1988; Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–81; Reference Hirsh and KornrichHirsh & Kornrich 2008; Reference HoffmanHoffman 2005; Reference KesslerKessler et al. 1999; Reference MarshallMarshall 2005; Reference MichelsonMichelson 2007; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81; Reference Nielsen and NelsonNielsen & Nelson 2005; Reference NielsenNielsen 2004; Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974).Footnote 3 Our conceptual approach to legal mobilization specifically builds on three well-known literatures within the law and society tradition on the management of conflict. The first of these literatures is the dispute transformation framework, which depicts the natural history of disputing as evolving through a number of stages on the way to an articulated claim for redress against a party or parties identified as at fault (Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–81). In contemporary American society, few disputes are transformed into legal claims, and the aggregate evolution of disputes tends to graphically resemble a pyramid, with a broad base of grievances and rights violations, but strong attrition so that only about 5 percent of all grievances reach the trial stage (Reference MichelsonMichelson 2007; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81; compare Reference Nader and ToddNader & Todd 1978).

The other two literatures we draw on investigate actions that operate tangentially or wholly apart from formal law. One of these literatures focuses on disputing in the “shadow” of law (Reference Mnookin and KornhauserMnookin & Kornhauser 1979), involving constellations of law-like procedures, such as organizational grievance procedures, mediation, or arbitration (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman & Suchman 1999; Reference Edelman and ErlangerEdelman, Erlanger, et al. 1993; Reference FelstinerFelstiner 1974; Reference HeimerHeimer 1999). The last literature we draw on explores the range of actions that people take outside the law to pursue rights violations, including coercive and remedial self-help, bilateral negotiation, avoidance, covert actions, and “lumping” (Reference BaumgartnerBaumgartner 1988; Reference BlackBlack 1983; Reference EllicksonEllickson 1991; Reference EmersonEmerson 2008; Reference MacaulayMacaulay 1963; Reference MorrillMorrill 1995).

In drawing from these sources, we conceive of legal mobilization as emerging out of a pool of perceived rights violations (which may or may not have a basis in formal law) and comprising multiple modes of action: (1) formal legal action, such as filing a formal lawsuit, filing a formal complaint with a government agency (e.g., the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission), or contacting a lawyer; (2) quasi-legal action, such as using formal complaint procedures provided by the school, district, or equivalent organization (e.g., an archdiocese), or using some sort of internal dispute resolution forum (i.e., mediation, peer counseling, etc.); (3) extralegal action, such as contacting the media, directly confronting a person verbally or physically, seeking support from a counselor or religious professional, avoiding the person, talking with peers or family members, or engaging in prayer; and (4) doing nothing (“lumping it”).

In Figure 1, we overlay our conceptual model of legal mobilization on the outline of the classic dispute pyramid (Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81). With the exception of doing nothing, these responses are not mutually exclusive as youth (or adults) can pursue several strategies at once. Moreover, they may not unfold in temporally linear ways (e.g., from more formal to less formal or vice versa). Instead, we view these strategies as potentially reinforcing, but also potentially in conflict with each other depending upon their salience and meaning in particular sociocultural contexts. By conceiving of mobilization as a multidimensional process, our approach can potentially reveal a broader range of options that youth have for mobilizing their rights apart from law and a framework for examining whether youth combine different options as they mobilize their rights.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Legal Mobilization as Multidimensional.

A Sociolegal Perspective on Youth, Identity, and Legal Mobilization

We theoretically ground the definition of and responses to rights violations in the concept of self-identity, which not only refers to the social processes through which people come to recognize themselves and others but also provides a basis for evaluating one's own actions and those of others (Reference Oberweis and MushenoOberweis & Musheno 1999:899–900). In adolescence, self-identity becomes especially salient as youths increasingly question who they are, what they hope to be, and the ways they plan to conduct their lives (Reference EriksonErikson 1968; Reference White and WynWhite & Wyn 2008:191–209). Self identity is always contingent and interactional, and contains multiple components that may or may not be consistent with one another.

How Youth Mobilize Rights

Research on the sociology of adolescence and youth culture generally suggests that youth actively carve out autonomous social worlds apart from the gaze, control, and protection of adults (Reference ColemanColeman 1961; Reference DornbuschDornbusch 1989; Reference Skelton and ValentineSkelton & Valentine 1998; Reference Weis and FineWeis & Fine 2000; Reference White and WynWhite & Wyn 2008). Multiple qualitative studies in schools and communities have documented the predominance of extralegal actions that youth take to manage peer conflict and trouble with adults involving actions intended to alter the conditions under which rights violations occur or avoid offending parties (Reference CarterCarter 2005; Reference EmersonEmerson 2008; Reference Garot, Monaghan and GoodmanGarot 2007, Reference Garot2009; Reference Morrill and MushenoMorrill & Musheno, forthcoming; Reference Morrill and YaldaMorrill, Yalda, et al. 2000). With respect to teachers and other adults (especially in positions of official authority), some actions along these lines can involve various kinds of resistance (Reference McFarlandMcFarland 2001, Reference McFarland2004). Aside from their own agency in handling conflict, youth may also perceive their standing as minors and their relative power as youth vis-à-vis adults as formal barriers to mobilizing law or taking quasi-legal action (Reference FineFine et al. 2003). Therefore, we posit that youth are in general more likely to turn to extralegal forms of rights mobilization.

Hypothesis 1: In response to hypothetical scenarios containing rights violations, youth are more likely to claim that they would take extralegal action than mobilize formal law, take quasi-legal action, or do nothing.

Hypothesis 2: In response to actual rights violations, youth are more likely to report they took extralegal action than mobilized formal law, took quasi-legal action, or did nothing.

How Race Matters in Youth Perceptions of Rights Violations

As youth who identify as African Americans and/or Latinos/as navigate their high schools, they can become especially aware of their collective, subordinated status in local and national-level ethnoracial hierarchies, particularly when they encounter institutional “messages that education does not pay and that discrimination prevents people of color from ever succeeding” (Reference Portes and RumbautPortes & Rumbaut 2001:61; see also Reference CarterCarter 2005; Reference HallinanHallinan 2001; Reference OakesOakes 1985; Reference Rosigno and Ainsworth-DarnellRosigno & Ainsworth-Darnell 1999; Reference Telles and OrtizTelles & Ortiz 2008; Reference TysonTyson et al. 2005; Reference Walters and BriggsWalters & Briggs 1993; Reference Waters and EschbachWaters & Eschbach 1995). In this context, youths' self-identities as African Americans and/or Latinos/as can become a key way of organizing their orientations and expectations toward their daily experiences with legal and other agents of institutionalized authority (Reference Flanagan and SherrodFlanagan & Sherrod 1998; Reference Hagan and HirschfieldHagan, Hirschfield, et al. 2002:242–3; Reference Hagan and SheddHagan, Shedd, et al. 2005:383–5; Reference HelwigHelwig 1995).Footnote 4 Students who identify as white also tacitly organize their experiences around being white but do not, except when attending schools with other self- and socially identified ethnoracial groups, develop distinct senses of their “whiteness” (Reference PerryPerry 2002). Instead, white students typically define “white” as “normal” (i.e., “race-neutral”; Reference PerryPerry 2002) and may consider themselves less vulnerable to the everyday injustices experienced by African American or Latino/a youth (Reference FineFine et al. 2003).

In a survey study of more than 18,000 Chicago public high school students, for example, Reference Hagan and SheddHagan, Shedd, et al. (2005) found that self-identified African American and Latino/a youth perceive themselves to be more vulnerable to and experience more discriminatory police contacts than white students. Other studies suggest similar patterns with respect to African American and Latino/a youths' expectations of discrimination by adults in official capacities: by teachers in schools (Reference Rosenbloom and WayRosenbloom & Way 2004); by private security guards and police in public places, such as shopping malls (Reference O'DoughertyO'Dougherty 2006) or city streets (Reference FineFine et al. 2003); by police while driving a car (Reference Lundman and KauffmanLundman & Kauffman 2003); or by prospective employers (Reference PagerPager 2007).

The few studies on perceptions of rights among African American and Latino/a students regarding rights violations relevant to freedom of expression suggest parallel findings to those on discrimination (Reference Bloemraad and TrostBloemraad & Trost 2006; Reference Haney LópezHaney López 2003), with social movement research specifically suggesting that African American youth expect and experience intense repression of their rights to freedom of expression (Reference CrenshawCrenshaw 1988; Reference EarlEarl et al. 2003; Reference McAdamMcAdam 1988; Reference Stockdill, Mansbridge and MorrisStockdill 2001). With respect to the experience of sexual harassment, multiple survey-based studies demonstrate its pervasiveness in secondary schools, although firm estimates of the influence of race and ethnicity on the experience of harassment are unavailable because of data collection and institutional constraints (see the review in Reference LeeV. Lee et al. 1996). Qualitative evidence, however, suggests that African American women and adult Latinas experience higher rates of perceived sexual harassment than white women in workplaces (Reference CortinaCortina 2001).

Hypothesis 3: African American and Latino/a youth perceive rights violations at higher rates than white youth.

Youth who self-identify as Asian Americans may be situated quite differently from African American or Latino/a youth. Although Asian Americans have suffered a long, collective history of discrimination and engaged in an intense striving for rights as a means for full membership in American society (Reference AnchetaAncheta 2006; Reference MotomuraMotomura 2006), contemporary Asian American youth in schools are also socially constructed as a “model minority” that is assimilating or has assimilated into “mainstream” (read white) society via aggregate high academic achievement and subsequent career success (Reference LeeS. Lee 2009). This dynamic can lead to a conflicted self-identity—on the one hand, “flattering in comparison with stereotypes of other racial minorities,” yet also dehumanizing—and may also lead to self-censure by Asian American students about their “own experiences and voices” regarding rights violations (Reference LeeS. Lee 2009:9). This self-censure may result in self-reports of rights violations among Asian American youth that approximate those among white youth.

Hypothesis 4: Asian American youth perceive rights violations at rates similar to white youth.

How Race Matters in Hypothetical Rights Mobilization

As youth come to self-identify as African American or Latino/a, they can also become aware of the historical legacies of the “minority rights revolution” (Reference SkrentnySkrentny 2002), especially the civil rights movement. Within this legacy, schools played important roles both as vehicles for achieving and teaching about ethnoracial equality and justice. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, fiscal and political support for education increased at every level of government, and ethnoracial justice became an important rationale for these efforts (Reference KirpKirp 1982:197). As commonly taught in high school civics or history classes, this legacy is often organized around stories about the courage of individual African Americans (and Latinos/as in more inclusive versions) to challenge racial and ethnic injustice (Reference Aldrige and ArmstrongAldrige 2002; Reference DunnDunn 2005; Reference View and ViewView 2004; e.g., the Denver Public School District's Alma Project curriculum, “Lessons in Courage: Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and Ruby Bridges” [Reference WilliamsB. Williams 2001], or online curricula, such as http://www.adl.org/education/rosa_parks/sources-information or http://www.freechild.org/student_rights.htm). Although a recent national survey revealed high school seniors' knowledge of important historical events in American history to be rudimentary at best, 97 percent of the students surveyed could accurately identify Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as “a historically significant figure” who challenged racist authority and led the civil rights movement (Reference HessHess 2008:9).

In these and similar curricula, Rosa Parks' refusal to move to the back of a segregated Montgomery, Alabama, city bus in 1955 or the first days of school integration in 1957 by small groups of African American students in Little Rock, Arkansas (the “Little Rock Nine”), are celebrated not only for their protagonists' courage, but also as the beginnings of waves of court cases that continued and extended the legacy of Brown and other landmark legal decisions to challenge the constitutionality of racial and ethnic segregation and discrimination across all spheres of American life (Reference Williams and BondJ. Williams & Bond 1988). Stories of individual rights mobilization (in actuality embedded in formally organized collective action and social movements; Reference PollettaPolletta 2006) have importantly become part of the “myth” about American “egalitarian possibilities of beleaguered minorities” (Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974:78; see also Reference AbregoAbrego 2008; Reference Delgado and StefancicDelgado & Stefancic 2000). This myth, however, may not figure in the same ways in the collective consciousness of white youth, who may imagine legal rights not as part of the march toward social justice, but as a taken-for-granted element of law and order or, even more pervasively, as somewhat peripheral to their everyday lives (Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974:78; Reference SkrentnySkrentny 2002). These orientations may be especially strong in white youth who define their “whiteness” as “normal,” and hence perceptually removed from the social injustices experienced by nonwhite youth (Reference PerryPerry 2002).

So deeply can the myth of rights inhabit the legal consciousness of African Americans that Williams has argued, “To say that blacks never fully believed in rights is true; yet it is also true that blacks believed in them so much and so hard that we gave them life where there was none before” (P. Reference Williams, Delgado and StefancicWilliams 2000:87). For Latinos'/as' legal consciousness, especially that of newly arrived immigrants, the mobilization of civil rights is at the core of escaping the status of “permanent foreigner” that, in turn, enables the recognition of social membership in U.S. society and the “pursuit of [individual and collective] projects without harassment and discrimination” (Reference Young, Gracia and De GriefYoung 2000:159; Reference AbregoAbrego 2008; Reference Gómez and SaratGómez 2004). Thus, for African American and Latino/a youth, in contrast to white youth, the mobilization of formal law may occupy a much more salient place in their ideals about how social injustice should be handled.

Although taking quasi-legal action does not present the same barriers for youth as mobilizing formal law, African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and white youth may ideally view such actions as similar to formal legal action. This perception may occur because of the popular sense that the private legal order of quasi-legal structures is fused with the public legal order (Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman & Suchman 1999) or simply because, from the perspective of youth, all institutionalized authority (whether law or not) points toward adult authority (Reference Morrill and MushenoMorrill & Musheno, forthcoming).

Hypothesis 5: In response to hypothetical scenarios containing rights violations, African American and Latino/a youth are more likely than white youth to claim they would mobilize formal law or take quasi-legal action.

The legacy of the civil rights movement has not figured as prominently in the legal consciousness of Asian Americans despite more than a century of discrimination, as well as individual and collective struggles for rights and social justice (Reference AnchetaAncheta 2006; Reference MotomuraMotomura 2006). On the contemporary scene, Asian American legal consciousness, especially among youth, may be powerfully shaped by the pervasiveness of the “model minority” construct in American schools (Reference LeeS. Lee 2009). Asian American youth may draw on this construct (albeit with ambivalence or lament) as they define their own identities, thus leading away from formal law as a means of redress for social injustice.

Hypothesis 6: In response to hypothetical scenarios containing rights violations, Asian American youth are less likely than white youth to claim they would mobilize formal law and take quasi-legal action.

How Race Matters in Actual Rights Mobilization

Against the backdrop of the heroic imagery of the civil rights movement, many African American and Latino/a youth face multiple barriers to actually mobilizing their rights. First, many African American and Latino/a youth, compared to white or Asian American youth, may face especially difficult financial and knowledge barriers to mobilizing formal law given lower aggregate income and educational attainment levels across African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and white households (Reference Oliver and ShapiroOliver & Shapiro 2006).

Second, the long history of African American oppression and contemporary police surveillance in African American communities has created a pervasive and profound African American distrust of legal authorities (Reference AndersonAnderson 1999; Reference NielsenNielsen 2004). African American youth socialization into this “cognitive landscape” (Reference Sampson, Bean and PetersonSampson & Bean 2006) is reinforced by aggregate police neglect of everyday problems in African American communities (Reference AndersonAnderson 1999) and intense scrutiny of black youth when they venture into white or multiethnic contexts (Reference Hagan and HirschfieldHagan, Hirschfield, et al. 2002; Reference O'DoughertyO'Dougherty 2006). This scrutiny has increased during the last generation as all youth have come under intensive surveillance with shifts in federal and local educational policy from concerns about access to education for socially disadvantaged groups to concerns about the “dangerousness” of such groups, especially African American youth (Reference FergusonFerguson 2000; Reference Krisberg and FramptonKrisberg 2008; Reference KupchikKupchik 2009; Reference SimonSimon 2007:207–31; Reference Welch and PayneWelch & Payne 2010). As a result, African American youth, compared to white teens, may become resigned to the inability of law to redress the injustices they encounter (Reference BumillerBumiller 1988:61) and may be motivated to do nothing or take extralegal measures to respond to rights violations that also bolster their reputations among peers (Reference AndersonAnderson 1999).

Latino/a youth experience some of the same collective distrust of legal and official school authorities and resignation as African Americans, but they are also embedded in the specter of concerns about citizenship and the potential for deportation from the United States. For Latino/a youth, not turning to formal law or taking quasi-legal action may therefore be rooted in collective anxieties and social stigma associated with actually being or being perceived as undocumented and living in the shadows of the “mainstream … legal” society (Reference Menjívar and BejaranoMenjívar & Bejarano 2003:126; Reference AbregoAbrego 2008). Thus, Latino/a youth may be motivated as much by collective stigma as distrust of the law and other forms of official authority to do nothing or take extralegal action in response to situations they define as rights violations by peers or adults (Reference CintrónCintrón 2000; Reference Sánchez-JankowskiSánchez-Jankowski 2008).

The situation of Asian American youth, in the aggregate, may again suggest different mechanisms in play with respect to their responses to rights violations than that of African American or Latino/a youth. In particular, Asian American youth may be concerned about sullying the sometimes “flattering” model minority stereotype they experience or because school officials and other adults do not regard grievances by Asian American youth as serious, because their perception may be that Asian American youth are collectively “problem-free” compared to other ethnoracial groups, including white youth (Reference LeeS. Lee 2009). The pressure to conform to the problem-free stereotype is likely to lead Asian American youth to do nothing or to take extralegal actions in response to rights violations (Reference Rosenbloom and WayRosenbloom & Way 2004).

For white youth, the situation is likely to be different still. Although the increased surveillance and security presence in schools has been pervasive throughout the United States (Reference KupchikKupchik 2009), it has been felt most keenly and disproportionately by African American and Latino/a youth (Reference KupchikKupchik 2009; Reference Welch and PayneWelch & Payne 2010). Indeed, white youth are more likely than nonwhite youth to perceive law and official authority in public spaces as a form of “protection” rather than control, which may lead them to be less distrusting or fearful of, and more reliant on, legal and other official authority to redress rights violations (Reference FineFine et al. 2003).

Hypothesis 7: In response to actual rights violations, African American, Latino/a, and Asian American youth are less likely than white youth to report they took quasi-legal or formal legal actions in response to actual rights violations.

Hypothesis 8: In response to actual rights violations, African American, Latino/a, and Asian American youth will be more likely than white youth to report they did nothing or took extralegal action in response to actual rights violations.

Methodological Procedures and Contexts

We investigate the hypotheses above with surveys of students and in-depth interviews with students, teachers, and administrators in U.S. public, private (Catholic), and charter high schools in large metropolitan areas of California, New York, and North Carolina.Footnote 5 We selected these three states in order to examine the operation of law in school life across three different state-level legal contexts.

Study Design

Within each state, we sought variation in school sector (public, public charter, and private) and the social composition of student bodies (principally by household income as indicated in the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch under the National School Lunch Program). To the extent possible, we selected within each state four public schools (two each that served upper-/middle-income populations and two that served lower-income populations); two charter schools (one that served an upper-/middle-income populations and one that served a lower-income population); and two private schools (one that served an upper-/middle-income population and one that served a lower-income population). We chose Catholic schools as exemplars of private schools in the sample because they are the modal type of private school in the United States and because they have similar supra-school governance structures to public schools (e.g., dioceses and archdioceses vs. school districts). In six of the eight schools within each state, we conducted surveys of students, teachers, and administrators. In the remaining two schools (one each that served an upper-/middle-income population and one that served primarily a lower-income population) in both California and New York, we conducted in-depth interviews and surveyed students, teachers, and administrators toward the end of the data collection period. In North Carolina, due to access problems, we conducted in-depth interviews only at an upper-/middle-income school.

State Legal Contexts and School Sites

Each of the states in the study is subject to a uniform set of federal statutes and Constitutional principles with respect to education but nonetheless exhibits differences in particular rules and procedures, especially surrounding discipline and corporal punishment. California has long prohibited corporal punishment, whereas New York formally permits it, although it is banned in New York City. By contrast, North Carolina educational code permits corporal punishment as long as it is done “without malice” and to further “educational goals” (Reference BerkBerk 2007:24). All three states also have explicit provisions that reinforce civil rights protections against discrimination, but only California and New York have protections for “non-citizen” students (Reference BerkBerk 2007:7).

Evidence of campus security could be found at all our study sites. At each of the public school sites, private security guards could be found patrolling the hallways on any given day, and at our lower-income schools, police officers were often present. Catholic schools, with the exception of North Carolina, had guards posted at campus entrances but not elsewhere. The California and New York charter schools exhibited a mixture of characteristics: Lower-income charters had guards (but not police), while middle-income charters posted guards at entrances, but not inside campuses.Footnote 6

Surveys

At each of the schools in the sample, we surveyed the entire ninth and eleventh grade classes, focusing on youths as they entered high school and toward the end of their high school careers. The surveys focused on perceptions of law, rights, and rights violations at the individual level, with components including (1) demographics (including sex, age, race, ethnicity, social background, status with respect to federally recognized special needs, and educational/employment position—such as track placement or work assignment and job tenure); (2) current understandings and past experiences of law and legal structures (including perceptions of fairness); (3) ideas about law, legal structures, and institutional authority; (4) previous experiences with rights violations involving discrimination, harassment, discipline, and freedom of speech/assembly; and (5) a set of hypothetical scenarios (one per respondent) representing the same areas of rights violations as in the section about past experiences.

With respect to race and ethnicity, we asked students, “How do you identify your ethnicity or ancestry, that is, what do you call yourself?” and offered these categories: White/Anglo, African American/Black, Hispanic/Latino/a, American Indian, Asian American/Pacific Islander, Arab American, mixed ethnicity, or other.Footnote 7 We based questions about rights violations in part from the Civil Litigation Research Project (CLRP; Reference KritzerKritzer 1980–81; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81) and qualitative studies of legal mobilization and consciousness among adults and youth (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998; Reference FullerFuller et al. 2000; Reference Morrill and YaldaMorrill, Yalda, et al. 2000). Respondents were asked to check off any of the following situations they had experienced: peer harassment, discrimination, freedom of expression, sexual harassment, and disciplinary problems by a teacher or administrator. If respondents checked off any of these items, they were then asked to indicate which of the incidents they checked was the most “significant” or “important,” and how they handled the situation using a list of items we classified as falling into one of our four mobilization categories (formal legal, quasi-legal, extralegal, or doing nothing). If respondents did not check off any actual experiences, they could proceed directly to the last section of the survey containing a hypothetical scenario.

In-Depth Interviews

Socially diverse teams of graduate and undergraduate students led by three of the four authors of this article conducted in-depth interviews of youth (n=86), teachers (n=36), and administrators (n=9). We selected respondents purposively to represent the demographics and diverse experiences of youth and teachers on each campus, and we interviewed the principal at each site plus, where possible, an assistant principal in charge of discipline.

Each youth interview lasted between 30 minutes and two hours, was taped, and contained a tripartite structure: an opening section on respondents' general impressions of their schools, the informal social organization of their peers, and demographics (including how they identified themselves ethnically); a second section focused on each informant's knowledge and experiences of trouble and problems on campus; and a final part on informants' impressions of formal rules and rights on campus. Each teacher and administrator interview had the same structure, except that the first section included questions on work history and impressions of the student body at their school, the middle section included questions about “typical” problems and disputes encountered on campus, and the last section included questions about administrative and union relations in the teacher interviews, and union and district relations in the administrator interviews. The interview structure thus combined open-ended techniques used effectively in previous studies of informal disputing in organizations (e.g., Reference MorrillMorrill 1995) and legal consciousness (e.g., Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998), with more explicit foci on school rules and rights.

Our analysis of the interview data proceeded in two phases. First, SRP team members read through all the interview transcripts as “data sets” (Reference EmersonEmerson et al. 1995). We discussed our readings at multiple meetings with the entire SRP team during which we inductively developed initial qualitative coding categories via an “open coding” process (Reference LoflandLofland et al. 2005) that also drew on categories from our survey so that we could triangulate our findings across multiple data sets and interlace our interview and survey findings in write-ups. Second, we refined our initial codes and developed a master qualitative coding scheme using Atlas.ti to code each of the qualitative data sets from California, New York, and North Carolina. Because of the size of the California data set, the California team coded its own transcripts and the North Carolina and New York teams collaborated on coding their data sets. To enhance the cross-team reliability of our coding, we selected two extended, representative excerpts of transcripts from each state and had all SRP members participating in the qualitative analysis code them. We then compared our coding across teams and found high levels of interpretive consistency.

Response Rates and Sample Characteristics

The student response rates across schools ranged from 61 to nearly 100 percent, which resulted in a sample of 5,461 students. As can be seen in Table 1, nonwhite students comprised just under half the sample, with Latino/a students the largest among this group (17.4 percent), followed by African American students (13.1 percent), those students who self-identified as other (10.7 percent), and Asian American students (4.7 percent).Footnote 8 As a proxy for socioeconomic status, we used parental education: More than three-quarters of students reported that either their mother's or father's education extended beyond high school. With respect to grade level, our sample was slightly skewed toward younger students (59 percent were ninth graders and 41 percent were eleventh graders), slightly more than two-thirds of respondents reported living in a two-parent household (69.7 percent), a small percentage reported being disabled (4.8 percent), and nearly all students reported being citizens (96.2 percent). The vast majority of our students attended public or Catholic schools (owing to typically small enrollments in public charter schools). The largest proportion of the sample came from California (39.2 percent), with just over a third from North Carolina (33.6 percent) and approximately one quarter from New York (27.2 percent).

Table 1. Student Descriptives

Multivariate Strategy

To estimate the relationships between the four types of legal mobilization and self-identified ethnoracial category, we estimated logit models. In a baseline model, we controlled for a number of individual and contextual characteristics. We based our decision to control for individual-level variables as a result of findings from previous research. First, previous research demonstrates that gender can influence legal mobilization in workplaces in response to discrimination and harassment net of other factors (Reference HoffmanHoffman 2003; Reference MarshallMarshall 2003). Second, we used parental education as a proxy for material and knowledge-based resources in households because such resources have been demonstrated in previous research to influence legal mobilization and socialization (e.g., Reference GalanterGalanter 1974; Reference LareauLareau 2003; Reference Mayhew and ReissMayhew & Reiss 1969; Reference MerryMerry 1990). Third, we controlled for U.S. citizenship because of the possibility that being documented or undocumented might affect the likelihood of mobilizing law net of ethnoracial category (Reference AbregoAbrego 2008; Reference Menjívar and BejaranoMenjívar & Bejarano 2003). Likewise, one's sense of being disabled may be related to rights consciousness and the perception of law as a viable response to rights violations (Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003). Finally, following standard practices in education research, we controlled for type of household (single or two-parent household) and grade level (Reference ArumArum 2003). Our contextual controls included type of school (public, Catholic, and charter) and state (California, New York, and North Carolina).

In a second model, we included the respondent's experience with actual (past) rights violations as a control because experiences with injustice may alter perceptions of the efficacy of law for redressing rights violations (Reference BumillerBumiller 1988) and the likelihood of mobilization (Reference FullerFuller et al. 2000). We ran separate logits for doing nothing and for each of the three types of mobilization independently. Thus, students could report that they would take one or several paths (i.e., extralegal, quasi-legal, and formal legal) to mobilize rights. We adjusted standard errors for school-level clustering.

Rights Violations and Legal Mobilization in Schools

The 51.7 percent rate of rights violations among youth in our sample was higher than self-reported rights violations in the only previous national random survey of legal mobilization by adults in CLRP, which reported an overall rate of 41.6 percent for all grievances (including discrimination in the workplace, consumer complaints, and community problems; Reference Miller and SaratMiller & Sarat 1980–81). Other studies report grievance rates of 20 to 35 percent for consumer problems (Reference Best and AndreasenBest & Andreasen 1977; Reference King and McEvoyKing & McEvoy 1976; Reference WarlandWarland et al. 1975), 60 percent for “low-income” consumer problems (Reference CaplovitzCaplovitz 1963), and 45 percent for used car problems (Reference McNeilMcNeil et al. 1979).

Legal Mobilization and Youth

The patterns in Table 1 generally support Hypothesis 1 (taking extralegal action in response to a hypothetical rights violation): The vast majority of youth (79.4 percent) reported that they would respond to a hypothetical rights violation by taking extralegal action, followed by some sort of quasi-legal action (31.2 percent), doing nothing (15.4 percent), and taking formal legal action (8.5 percent).Footnote 9 In support of Hypothesis 2 (taking extralegal action in response to an actual rights violation), the vast majority (76.3 percent) of the students who reported actual rights violations also reported taking extralegal action, followed by engaging in quasi-legal action (21.4 percent), doing nothing (19.3 percent), and taking formal legal action (3.2 percent). Indeed, fewer than 5 percent of students actually pursued any formal legal action at all in response to rights violations.

Youths' everyday understandings of the constraints they face in mobilization processes were evident throughout our qualitative interview data, as illustrated by this self-identified “Dominican” female senior regarding punishment in a New York school:

Interviewer: What rights do you think you have when you're facing punishment by a teacher or an administrator?

Student: Well I think that as long as they have to hear what you have to say and then at least consider it, then I think that—I mean, I know I don't have that many rights. I don't. The authority, I can't do anything. I'm 17 years old. I'm a minor, I don't have anything.

In this excerpt, the student began to assert that she did have rights (“as long as they have to hear what you have to say and then at least consider it”) that spoke to due process, but then denied she could actually use those rights to address “authority” as it was exercised against her because of her age (“I'm a minor, I don't have anything”).

While some youths lapse into resignation and inaction in response to rights violations, a more prevalent pattern in our qualitative data (consistent with our survey data) was mobilizing rights via extralegal action. Consider this example from a senior at a California school who identified himself as “mixed Latino/a, Asian, and white”:

Well, of course there's the rights that have to do with American law and the right of free speech…. All those rights here, you know, are recognized in some way ideally…. See, with the teachers, it's usually the students talk[ing] amongst themselves about the teacher. [Students] don't go out and tell on them or anything. They're all like “Oh, this teacher—he's racist or something.” They're not going to go to an authority and tell somebody they're racist or anything. They just kind of say it amongst themselves or do something on their own…. Kids don't have much power compared to adults … but they know how to get back at a teacher if they want to … make their classrooms hell.

Like the informant from New York, this respondent claimed that his school generally “recognizes” rights in “American law” but then observed that students did not “have … power” relevant to adults, rarely mobilizing their rights formally when faced with rights violations. Instead, they resorted to extralegal action (“say it amongst themselves or do something on their own”). Youth can feel powerless in trying to exercise formal channels to handle problems with adults in their schools, but powerful outside of those channels. Some of their actions in this regard tap into the myth of rights (Reference ScheingoldScheingold 1974) but more typically draw on local knowledge about how school order is maintained as a way to frame and act against official authority deemed unjust (e.g., Reference McFarlandMcFarland 2004). In this way, power and authority in schools are relational as is the basis for youth resistance to adult authority (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 2003).

With respect to peers, extralegal tactics are also the first line of action, as illustrated in the following interview excerpt from a self-identified “white” male senior at a middle-/upper-income school in California. The youth was responding to questions about whether he ever had “trouble” with students, and how he handled it:

I mean like it's kinda embarrassing. I had this girl, like she was … stalking me. Everywhere I went, there she was. I mean, dude, she was a trip. Now I'm not going to go to some counselor [or]. security dude and say “What the hey, there's this chick after me.”… I talked with my friends a lot and they said, “Whoa dude, you gotta right not to have her in your face like that.” So I went to her and told her to cool it. Get outta my face…. It worked for a while, then she, like was there again…. I changed my schedule … she transferred like the next term.

Although this pattern did not generalize to every interpersonal peer conflict we learned about through our informants, it was typical among youth in our data sets: a recognition of a problem or trouble with a peer (“I had this girl … stalking me”), consultation with trusted peers (“talked with my friends”), remedial action taken with the offending party in an attempt to alter her behavior (“went to her … told her to cool it”), avoidance (“changed my schedule”), and then resolution only when the offending party exited the scene (“she transferred”). These tactics are also consistent with a number of studies on the social dynamics of interpersonal conflict management (Reference EmersonEmerson 2008). What is interesting is the explicit sense given in the interview of mobilizing rights, not through the law or a quasi-legal structure, but via extralegal means. That is, rights can provide a rationale for one's actions even in the midst of operating outside official authority or law.

Rights Violations and Ethnoracial Identity

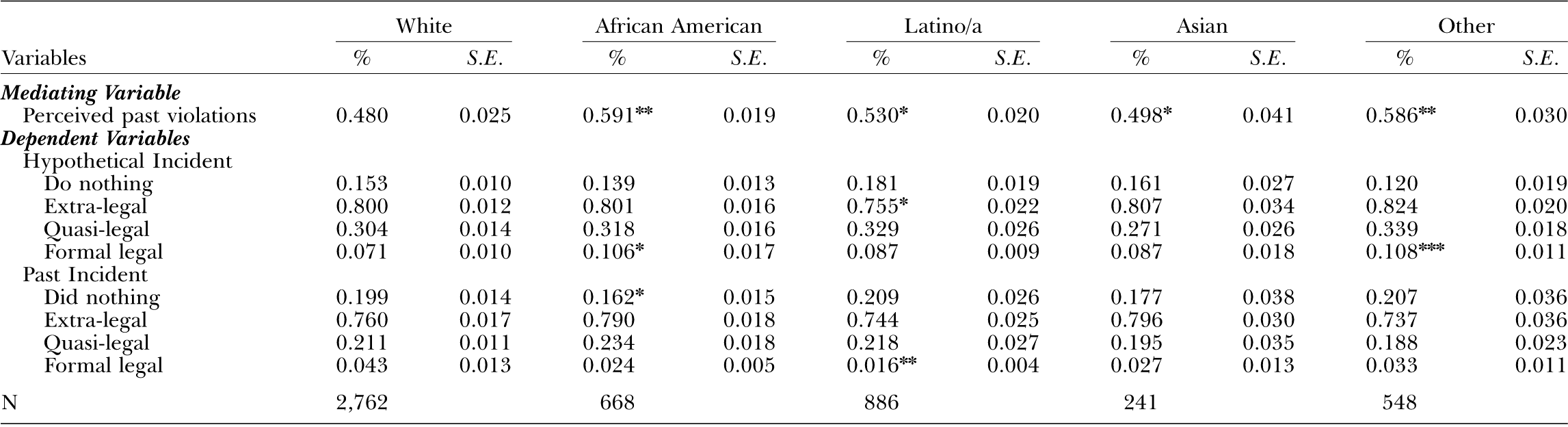

Quantitative evidence for the relationships between ethnoracial self-identity and perceived rights violations (Hypotheses 3 and 4) can be found in Table 2. In support of Hypothesis 3, African Americans (59.1 percent; p<0.01), Latinos/as (53.1 percent; p<0.01), and students who identified as other (58.6 percent; p<0.01) all reported higher overall rates of perceived rights violations than did white students (48.0 percent). In support of Hypothesis 4, Asian American students' rate of perceived rights violations (49.8 percent) was not significantly different from that of white students.

Table 2. Perceived Past Rights Violations by Race

* p<.05,

** p<.01

Note: Significant differences between minority and white students are noted with asterisks next to group percentages and means.

The disaggregation of these results by type of rights violation in Table 2 reveals a more complex picture.Footnote 10 All nonwhite students reported higher rates of teacher and administrator discrimination against them than white students (18.5 percent), with African American (33.7 percent; p<0.01) and Asian American students (33.2 percent; p<0.01) reporting the highest rates, followed by Latino/a students (28.2 percent; p<0.01) and students who self-identified as other (27.2 percent; p<0.01). Few students reported being denied services for special needs, and there were not any significant differences across racial and ethnic categories. Latino/a (7.9 percent; p<0.01) and Asian American (3.3 percent; p<0.01) students reported significantly lower rates than white students (10.8 percent) of inappropriate sexual language or behavior by teachers. Students of different racial and ethnic groups reported similar rates of inappropriate sexual language or behavior by peers (ranging between 25.4 percent for white students and 20.8 percent for Asian American students). Finally, students of different racial and ethnic groups reported similar rates of perceived rights violations with respect to teachers not following the correct (due process) disciplinary procedure (ranging from 18.3 percent for white students to 19.5 percent for African American students), save for Asian American students, who reported lower rates than did white students (14.1 percent; p<0.05).

Excerpts from in-depth interviews with youth about situations they defined as rights violations illuminate these patterns and underscore how ethnoracial identity organizes their interpretations. In the representative excerpts below, students from a California campus recounted their experiences in portions of in-depth interviews that covered problems with teachers. In the first excerpt, a self-identified “Mexican” female junior discussed her perceptions of discrimination in a teacher's evaluation of a writing assignment. In the second excerpt, a self-identified “mostly white and some Italian” female junior discussed her sense of discrimination on campus:

Oh, yeah with grades… . Like, I would look at my paper and a friend's paper who's Anglo, and I would do the same thing and she [the teacher] wouldn't give me full credit for it, and oh, look what I did here—it's the same as her… . There was definitely discrimination… . It's something you feel every day about because of what you look like, who you are, where you come from… . There's this sense that you, you can't take these classes, like whatever, you're not smart because you're Mexican or whatever.

** *

I mean, there's this one white kid that you can tell is kind of—he discriminates against like Mexicans. But it's hard to think of lots of problems like that from students or teachers… . Like maybe if I was black or Mexican or something, it might be different … From my perspective, there really isn't a big problem that I know about. I just don't see it.

In the first excerpt, self-identity intersected with what the student perceived as a stigmatized social identity (i.e., how the social category the student identifies with is perceived by others; Reference Engel and MungerEngel & Munger 2003). The context is an AP English class from which she believed “Mexicans” were excluded because of stereotypes about their intelligence. She also suggested that her experience of discrimination was an everyday occurrence and related it to who she is and, as she noted later in the interview, her country of origin (“where you come from”; she immigrated to the United States from Mexico with one of her parents when she was a young child). The second student's experience contrasts sharply with the first. The respondent spoke of a seemingly isolated case of peer discrimination against “Mexicans” and, interestingly, referenced how her self-identity might modify her sense of what goes on at her campus if she were “Black” or “Mexican.” From her vantage point as a white youth, she did not “see” discrimination by teachers, more generally, as a “problem” on her campus.

A very different sense of discrimination emerges from the perspective of a self-identified Thai and Vietnamese female junior on the same campus. Her experiences were not grounded in negative expectations by teachers and other adults but by heightened, positive expectations about the normativity of her behavior:

At home and in school it's the same, you have to be perfect. I never give anyone any trouble. Just mellow. I mean, like at home I get disciplined a lot more than I would here [in school] … because I am not allowed to do a lot of stuff anyways. Having, being so perfect all the time, it's difficult to believe bad stuff is happening to you, talk about it even … like when that kid who was staring at my feet in class and touching my bare feet in class when I wore sandals … I didn't do anything about it for a long time… . But like I think that a lot of teachers or counselors don't think things like that occur to an Asian. Like nothing deviant is supposed to happen with the whole super Asian thing… . Maybe that's why my counselor—I mean, I left him messages—and it took forever for him to get a hold of me.

The reference in this excerpt is to recurring sexual harassment in which a male peer would stare at and touch the respondent's bare feet in unwanted ways in class. In this excerpt, we find evidence for the model minority stereotype working in multiple ways. On the one hand, the respondent recounted normative pressures at home and in school for her to be “perfect” as an “Asian.” On the other hand, these pressures led to her disbeliefs and difficulties talking about her experiences being harassed (self-censoring). She recounted that she “didn't do anything” about the incidents for “a long time,” but when she did attempt to mobilize her “counselor” to address the situation she believed that what she called “the whole super Asian thing” played a role in his lack of responsiveness.

Legal Mobilization and Ethnoracial Identity

Bivariate Analyses

The patterns in Table 3 partially support Hypothesis 5 (that in response to hypothetical rights violations, African American and Latino/a students claim they would mobilize law and take quasi-legal actions at higher rates than white students) but do not support Hypothesis 6 (that in response to hypothetical rights violations, Asian American youth are less likely than white youth to claim they would mobilize formal law or take quasi-legal actions). More African American students (10.6 percent; p<0.05) than white students (7.1 percent) claimed they would mobilize law in response to a hypothetical rights violation, but nearly as many Asian American students (7.1 percent) as Latino/a (8.7 percent) and white students (8.7 percent) claimed they would mobilize law or take quasi-legal action (2.7 percent for Asian American youth vs. 3.0 percent for white youth).

The results in Table 3 also partially support Hypothesis 7 (that African American, Latino/a, and Asian American youth are less likely than white youth to report taking formal legal or quasi-legal actions in response to actual rights violations) and Hypothesis 8 (that African American, Latino/a, and Asian American youth are more likely than white youth to report taking extralegal action or doing nothing in response to actual rights violations). Latino/a youth reported mobilizing law at a lower rate in response to actual rights violations (1.6 percent; p<0.01) than white students (4.3 percent). African American and Asian students, by contrast, were no more likely than white students to mobilize law in response to an actual rights violation. African American students were also more likely than white students (19.9 percent vs. 16.2 percent; p<0.05) to report doing nothing in response to an actual rights violation, which may relate to the resignation felt especially by African American youth with respect to the everyday possibilities for social justice from formal legal or quasi-legal action.

Multivariate Analyses of Responses to Hypothetical Rights Violations

Our multivariate analyses in Table 4 provide a more sensitive examination of our two hypotheses regarding responses to hypothetical rights violations. In partial support of Hypothesis 5, African American youth were more likely to claim they would mobilize law in response to hypothetical rights violations in the baseline model (0.539; p<0.05). However, this result lost statistical significance in the second model that takes into account actual (past) experiences with perceived rights violations. It may be that the high rates of African American students who have experienced rights violations (especially discrimination) compels them to be more skeptical of the myth of rights and resigned to navigate through everyday rights violations without the law or quasi-legal action. This finding is consistent with Reference BumillerBumiller's (1988) argument that African American persons' experiences with injustice mediate their claims about what they would do in response to a rights violation. This quantitative result is also consistent with a typical observation drawn from our in-depth interviews with African American and Latino/a youth. Listen to this self-identified, “mixed Black-Mexican” senior male discuss learning about versus actually mobilizing rights on his California campus in response to a question about what rights he thought he had in school:

Table 4. Models Estimating the Likelihood of Taking Action Against a Hypothetical Rights Violation

* p<.05,

** p<.01,

*** p<.001.

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Analyses are adjusted for clustering of students within schools. Missing covariates (with the exception of gender and race) are mean substituted; dummy variables flagging missing covariates are included in the analyses but not shown.

Rights, rights, rights. We learn all about rights in school. You like listen to the speeches in class—hear the stories, Rosa on the bus, MLK, Caesar [Chavez] in the fields… . It's inspirational. I'm glad they did what they did, stood up for our, our rights and all. You wanna stand up for [one's rights] too. It's who I wanna be… . Like, like my mom has a picture of MLK on the wall and she always said to stand up for stuff… . What happens every day if you're black or Mexican—that gets you thinking different… . There's prejudice, racist stuff all the time. They always watching you, the guards, teachers, you know… . Sometimes it seems that what [civil rights figures] did … that what they did don't matter today. Maybe I can't be like that. I don't know.

Table 3. Mediating and Dependent Variables by Race

* p<.05,

** p<.01,

*** p<.001.

Note: Significant differences between minority and white students are noted with asterisks next to group means.

The paradox of rights and race is vividly expressed in this youth's voice. The narrative history of heroic acts and heroes of the civil rights movement is, as the youth observes, “inspirational,” and it is taught both in the class and at home. The courage to “stand up” for these ideals, so the respondent notes, is how he wants to define his identity. But the everyday realities, including constant surveillance by adult authorities, intrude on this ideal identity, causing dissonance between the images of the heroic past and the weight of the present. In the end, the youth questions whether the acts of mobilization associated with the civil rights movement matter for the everyday realities of prejudice and racism that he experiences, and he wonders whether he can live up to the heroic deeds of the past.

Also in partial support of Hypothesis 5, Latino/a youth were more likely than white youth to claim they would mobilize law in response to a hypothetical rights violation, both in the baseline model (0.325; p<0.01) and when taking into account actual (past) experiences with perceived rights violations (0.302; p<0.01). In partial support of Hypothesis 6, Asian American students were somewhat less likely than white students to claim they would engage in quasi-legal action both in the baseline model (−0.258; p<0.05) and when taking into account past experiences with rights violations (−0.264; p<0.05). Again, the model minority stereotype may play into these patterns and resonates with some of the difficulties alluded to earlier in the article in an excerpt from an interview with an Asian American respondent who repeatedly experienced peer harassment.

Other significant, non-hypothesized results also emerged in the findings relevant to ethnoracial identity and responses to hypothetical rights violations. Latino/a youth were more likely than white students to claim they would do nothing both in the baseline model (0.247; p<0.05) and when taking into account past experiences with rights violations (0.245; p<0.05). Latino/a youth were also less likely than white students to claim they would take extralegal action in the baseline model (−0.255; p<0.05) and when taking into account past experiences with perceived rights violations (−0.252; p<0.05). Again, these findings may result in the uneven ways that the interplay between the myth of law and rights and the realities of everyday life constitute the legal consciousness of minority youth. Finally, those students who identified themselves as “other” were more likely than white students to claim they would take formal legal action both in the baseline (0.593; p<0.001) and when taking into account past experiences with rights violations (0.541; p<0.001). Although our measure of ethnoracial identity in our survey did not, unfortunately, enable us to discern what specific ethnoracial categories “other” respondents identify with, previous survey research by Reference Lee and AbdelalT. Lee (2009) suggests that survey respondents who self-identify as “white” or “Asian American” are least likely to check “other” in categorical schemes. Thus, it may be that “other” students in our survey were more likely to be mixed African American and/or Latino/a, and therefore were similar in profile to our African American and Latino/a respondents.

Multivariate Analyses of Responses to Actual Rights Violations

Table 5 provides little statistical support for Hypotheses 7 or 8, save for the finding that Latino/a youth are less likely than white youth (−0.767; p<0.05) to report mobilizing law in response to an actual rights violation. The results for African American youth with respect to mobilizing formal law were negative (−0.480) but did not reach minimal statistical significance at the 0.05 level.Footnote 11 Our qualitative interview data, however, suggest nuances that our survey data cannot capture and that, in many ways, are consistent with the theoretical logics undergirding Hypothesis 7.Footnote 12

Table 5. Models Estimating the Likelihood of Taking Action Against a Perceived (Past) Rights Violation

* p<.05,

** p<.01,

*** p<.001.

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Analyses are adjusted for clustering of students within schools. Missing covariates (with the exception of gender and race) are mean substituted; dummy variables flagging missing covariates are included in the analyses but not shown.

Consider this representative interview excerpt from a self-identified “Mexican” junior female that we interviewed at a California school. She talked about student responses to a teacher's unwanted actions, which helps unpack our survey result that Latino/a youth are less likely than white youth to take formal legal action when they experience a rights violation:

There's this teacher—I think he abuses rights with a lot of the girls, making them feel extremely uncomfortable because he might very well be attracted to younger girls. And most of these girls don't speak up because, number one, they don't want to cause problems…. Like, myself, I don't know how comfortable I would be speaking out against him, just because I'm afraid of the repercussions….

In this and other interviews, Latino/a youth used rights to refer to normative boundaries across which adults (and sometimes peers) should not transgress but which do not in and of themselves ensure protection from such transgressions. A key feature of this respondent's comments was “repercussions,” which we learned from this respondent and her peers included anxieties about interpersonal retribution from teachers (for example, by grading a student “extra hard”) and/or fear about one's complaint to “official” authorities somehow leading to an investigation of one's family or friends for possible violations of imigre (immigration) law. Indeed, these comments were quite representative of Latino/a and African American youths' sense of the constant surveillance and discipline they face in schools. As noted earlier, youth are quite aware of the differential power between them and their teachers. For Latino/a youth we interviewed, especially in California, however, law was strongly woven into this sense of vulnerability that placed them one step away from having their lives disrupted, if not destroyed, by unwanted and unpredictable legal incursions.

This fear could also be discerned in the discourse of adults, especially administrators working with lower-income Latino/a student populations with high numbers of recently arrived immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Consider the comments from this self-identified “white” administrator:

Interviewer: I realize there may be differences across students, but tell me a bit how Latino youth handle problems that might arise with teachers involving, for example, a situation where they feel they've been discriminated against in some way.

Administrator: Look, kids from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, they don't want any trouble. If some problem happens with a teacher or other students, we invite them to come to us, to figure it out, to file grievance if it's warranted.

Interviewer: Do they come in?

Administrator: Not really.

Interviewer: Why?

Administrator: I know for a fact that they're scared if they come that someone might start investigating their family or something…. They don't always understand how the system works…. We're not going to do that. We're here to educate kids, not deport ‘em.

Interviewer: What about Anglo kids?

Administrator: Anglos, white kids, they'll make a helluva lot of noise—their parents will threaten a lawsuit … [they] know the system and how to use it … have the money to do that, whatever. They're not afraid of what might happen to them. They'll stir the pot.

This administrator obliquely suggested that Latino/a youth may not do anything (“don't want any trouble”) when faced with trouble they define as discrimination by a teacher (which is consistent with Hypothesis 8). He also summarized his sense of the fear that we encountered among Latino/a youth regarding both formal law and quasi-legal action in schools (e.g., “they're scared” and “don't always understand how the system works”), and drew a normative boundary between the school's primary purpose (education) and the goals of legal officials outside the school regarding the policing of undocumented persons. The administrator also signaled his perception about the relationship between white students, material resources, and the likelihood of formal legal mobilization, which is quite different from the sense we encountered among white youth that, from their perspectives, youth would generally not mobilize formal law or go to internal authorities with grievances against teachers. The administrator's statements, however, do resonate with long-standing research findings that the “haves come out ahead” in legal mobilization because of material resources and knowledge about the law (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974), as well as Reference LareauLareau's (2003) work regarding the activist role that middle-class parents (both white and nonwhite) play in steering their children through schools. Moreover, the administrator's statements, together with our data from youth, speak to the complexities of perceptions across youths and adults with respect to legal consciousness and mobilization in schools.

In addition to fear among Latinos/as, interviews with African American youth revealed the unfairness and resignation with which African American youth regarded how their schools handle rights violations and discipline. This qualitative pattern resonates with the theoretical logic undergirding Hypothesis 7 regarding the general distrust of law among African Americans, especially police, and the everyday realities faced by African American youth. In the following exchange with an interviewer, an African American male junior from a North Carolina school commented on a recent “race riot” on his campus:

Student: We had a race riot not too long ago.

Interviewer: I remember hearing about that.

Student: Yeah.

Interviewer: What happened with it?

Student: You know, so, a friend of mine named Joseph,Footnote 13 he was walking or something, and Harold, you know, being a white guy, you know, said something about him being a nigger. And so that's how it all started.

Interviewer: Wow.

Student: So that escalated from there.

Interviewer: OK. And so what did the school do about that?

Student: They had police here for a while, but, you know, I thought—I almost—I looked at it like they were protecting Harold, you know? They had him in an ISS [in-school suspension] room. Nobody could come in. He was, you know, surrounded by police. You know, if I would have said I was going to do some stuff like that, I would have been suspended for 10 days and he got suspended for three. So, you know, I think it was a little messed up, but it's not my decision on what happens here.

In the excerpt above, law is embodied by the police, who physically “surround” and “protect” a white perpetrator. The respondent further imagined the discipline and discrimination he would have suffered as an African American student if he, rather than the white student, was a key perpetrator in the “race riot” (“I would have been suspended for 10 days, and he got suspended for three”). The respondent resigned himself to the idea that there was little possibility he could shape in-school decisionmaking or outcomes in such matters.

The everyday realities for taking quasi-legal action in schools also appear in other student interviews. In one such interview, the interviewer asked an African American male senior at a New York school what options he considered for dealing with disagreements with teachers:

Interviewer: When you have disagreements with teachers, do you ever consider any other options for addressing them? Like talking to an administrator or using a formal grievance process? Even contacting a lawyer? Have you ever thought about it?

Student: Actually I haven't. Because what you get from it is nothing is going to happen…. The school is not really strict on being yourself, like stand up for school rights. It's not like that.

Not only does it appear, then, that African Americans become resigned to injustices given their past experiences, but African American males, not surprisingly, seem the most resigned. Even as the previous two excerpts highlight a sense of resignation, they also suggest youths' sense of connection to the larger injustices in play and that law should perhaps protect their rights but does not.

Conclusions

At the outset of this article, we asked how rights matter for youth in American high schools. Slightly more than half the students in our survey sample reported experiencing rights violations, but students self-identifying as African American, Latino/a, and “other” reported rights violations at significantly higher rates than students self-identifying as Asian American or white. Regardless of ethnoracial identification, the vast majority of youth reported in surveys and in-depth interviews that they would handle a rights violation via extralegal means. In general, youths recognize they have “rights” in the abstract (whether based in law or not), but they understand the limitations of rights given the social realities of everyday school life. When asked in surveys how they would respond to rights violations in hypothetical scenarios, however, African American, Latino/a, and students identifying as “other” were more likely than white and Asian American youth to claim they would take formal legal action. In response to actual rights violations, despite experiencing higher rates of rights violations than white students, African American, Asian American, and students self-identifying as “other” were no more likely than white youth, and Latino/a youth were less likely than white youth, to report taking formal legal action. Although all youth have become more subject to criminal justice technologies and control in American schools during the past 30 years (Reference SimonSimon 2007:207–31), we argue that the paradox of rights and race among youth in schools is integrally linked to disjunctions in schools between the myth of rights as a means of social justice and the disproportionate punishment and stigmatization experienced by African American and Latino/a youth (Reference KupchikKupchik 2009; Reference Welch and PayneWelch & Payne 2010). For Asian American youth, the paradox may be more linked to the social tensions they experience as being socially constructed as a model minority. In multiple ways, then, the paradox of rights and race in American high schools facilitates ethnoracial inequality between white and nonwhite youth.

That more than half our survey sample of youth could recall a rights violation within the “legal grid” (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998:237) of discrimination, sexual harassment, freedom of expression, and discipline also speaks to the moral force of rights to organize youth perceptions of and reactions to particular kinds of trouble in their everyday lives. Our qualitative data especially illustrate how youth draw on notions of rights to draw normative boundaries between justice and injustice, construct the moral character of their schools, and locate themselves in the institutional fabric of their campuses. At the same time, the great preponderance of extralegal action among all youth underscores how they, like adults, most often draw on normative orders apart from law to respond to trouble even when they define it in conceptual terms recognizable in some way as law. Given the contingent and experimental nature of adolescence (Reference DornbuschDornbusch 1989), as well as the exclusion of youth from voice in the institutional authority that governs much of their lives (Reference Morrill and MushenoMorrill & Musheno, forthcoming), it is especially important to understand the connections between normative orders during this developmental period because it may reveal how youth form the cognitive and behavioral habits (Reference GrossGross 2009) that inform legal consciousness in adulthood.

Especially important along these lines is exploration of the agency and inventiveness youth hint at when discussing extralegal action, which we have only touched upon in this article, and the interactional dynamics through which they constitute their self-identities in contexts of changing legal and school policies. Indeed, the potential tensions between these multiple orders and lines of action could even function as a form of education for youth about how institutionalized authority and unfair discipline are socially constructed and can be challenged (e.g., Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey 1998:238–9; Reference Morrill and ZaldMorrill, Zald, et al. 2003). The nationwide immigration protests in 2006, for example, in which thousands of Latino/a high school students participated (Reference ArchiboldArchibold 2006), demonstrate that under certain conditions, students can act collectively in the pursuit of social justice. To be sure, there is always a mixture of social and material conditions that make collective action of any sort possible (Reference Edelman and McAdamEdelman, McAdam, et al. n.d.; Reference McAdamMcAdam et al. 1996). Based on our in-depth interviews, we speculate that the nascent sense of rights and their linkage to broader social injustices expressed among nonwhite youth could provide the ideational foundations for a collective “oppositional consciousness” to facilitate political mobilization (Reference Mansbridge, Mansbridge and MorrisMansbridge 2001).