1. K43c and the word <hs’lyh> in the Zoroastrian ritual vocabulary

The fragment of Pahlavi manuscript labelled K43c consists of two non-contiguous folios (numbered 186 and 191 in Persian script) containing some liturgical indications concerning the Paragna ritual.Footnote 1 The text is still unpublished but is easily accessible thanks to the facsimile printed in Christensen (Reference Christensen1936, vol. 2).Footnote 2

Even from a superficial look, it is clear that ms. K43c provides a slightly different formulation of some ritual indications already known from the Nērangestān, which have recently been studied by Cantera (Reference Cantera and Farridnejad2020). In particular, f. 186 coincides to a great extent with N.30.10–11, where the procedures for drawing the water for libations are described, and ends with a fragment corresponding to N.49.14 dealing with the collection of consecrated milk (Av. gąm jīuuiiąm, Pahl. <jyw'> ǰīw) which is going to be mixed with the water (cf. Cantera Reference Cantera and Farridnejad2020: 73 f.). F. 191 (starting from l. 3) contains ritual indications on the cutting of the barsom similar to those given in N.79.8 ff. (cf. Cantera Reference Cantera and Farridnejad2020: 79–81).

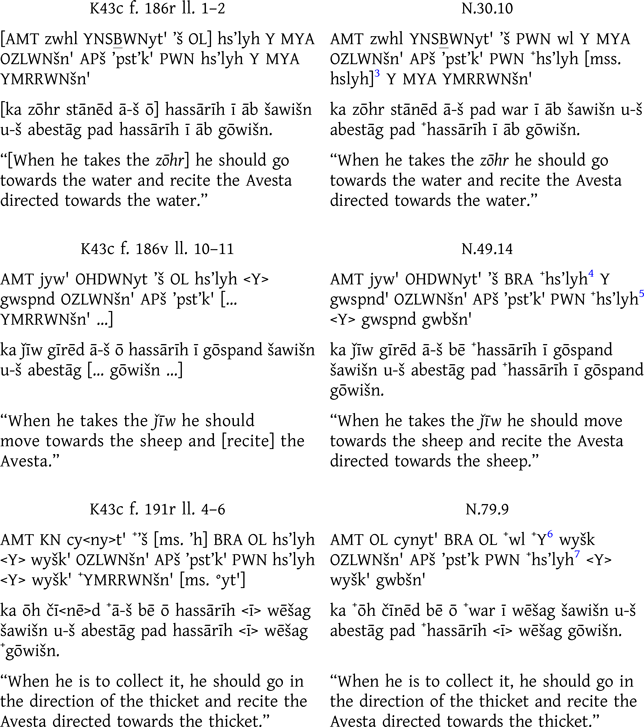

The fact that these passages from the Nērangestān have the same content as K43c but express it in different words is very helpful in clarifying the meaning of the very first word occurring in K43c, the subject of this paper. As I shall argue below, this word, which is not registered in the main lexicographical repertoires of Pahlavi, should be read as <hs’lyh> hassārīh. Here follows a synoptical presentation of the sentences in K43c containing this term, alongside their equivalent in the Nērangestān. The edition of the passages from the Nērangestān is based on Kotwal and Kreyenbroek (Reference Kotwal and Kreyenbroek1992–2009, abbreviated K&K) with some improvements made possible by comparison with K43c.

As can be seen, Pahl. hassārīh is used as an alternative to Pahl. war with the meaning “side, direction”.Footnote 8 Despite what may appear from Kotwal and Kreyenbroek’s edition, where war is systematically restored regardless of the manuscript readings, in the quoted passages from the Nērangestān there are only two certain occurrences of war, whereas everywhere else corrupted spellings for hassārīh are found. As a matter of fact, this is not the only case in which spellings pointing to Pahl. hassārīh have been misinterpreted or emended by editors. I have been able to identify at least four more passages from the Pahlavi religious literature.

N. 52.7 (after K&K/3: 236 f.):Footnote 9

AMT ’hlwb’n lwb’n plwhl YDBHWN’t' OL dšntwm blswm QDM ’y YBLWNyt' PWN +hs’lyhFootnote 10 Y zwhlk'

ka ahlawān ruwān frawahr yazād, ō dašntom barsom abar ē barēd, pad +hassārīh ī zōhrag

“When he worships the souls and fravashis of the righteous, let him make the offering on the point of the barsom that is farthest to the right, beside the zōhr cup.”

Pahl.Riv. 58.38 (after Williams Reference Williams1990: 208–9):

’š’n' BRA OL hs’lyh Y blsm OZLWNšn' APšn' ’pst’k PWN hs’lyh Y blsm gwbšn'

ā-šān bē ō hassārīh ī barsom šawišn u-šān abestāg pad hassārīh ī barsom gōwišn.

“Then they should go towards the barsom and recite the Avesta directed towards the barsom.”

Boyce and Kotwal (Reference Boyce and Kotwal1971: 68) take the spelling for <hs’lyh> as a corruption of Av. ašaiia and interpret the “ašaiia of the barsom” as a reference to Y.8.2 (so Williams Reference Williams1990), but there is clearly no need for such an emendation.

ŠNŠ.Supp. 13.9 (after Kotwal Reference Kotwal1969: 42 f.):

HNA l՚d PWN ahurāi mazdāi hs’lyh Y dtwš zwhl hm LBBME Y OLE zwt’ l՚st' YHSNWšn'

ēd rāy pad ahurāi mazdāi hassārīh ī daθuš zōhr ham dil ī ōy zōt rāst dārišn

“On account of this, at ahurāi mazdāi the zōhr should be held in the direction of the daϑuš exactly level with the heart of the zōt.”

Kotwal (Reference Kotwal1969: 102 fn. 16) reads <’s’lyh>, but in the text emends it to an otherwise unattested *sarīh, tentatively translated as “above” (not in his glossary at p. 169). A reading hassārīh “direction” is supported by the parallels exposed so far and fits perfectly within Kotwal’s interpretation of the sentence.

There remains one attestation of hassārīh in a difficult passage of the Pahlavi translation of the Gāϑā Ahunauuaitī (Y.28.9b):Footnote 11

yōi və̄ yōiϑəmā dasəmē stūtąm

“nous qui avons pris place à la cérémonie de vos éloges” (Kell.)

“(we) who are standing by at the offering of praises to You” (Humb.)

MNW ’w' HNA Y LKWM hs’lyh YHBWNm st’yt’l’n'

kē ō ēd ī ašmāh hassārīh dahom stāyīdārān

“(we) who (are) in Your direction tenth among worshippers (?)”

Presumably, already in the most ancient layer of the Pahl. translation, this sentence was not correctly understood due to the ambiguity of the Old Avestan (OAv.) forms yōiϑəmā (Pf.Ind.1.Pl. of yat- “to take a position”) and dasəmē (Loc.Sg. of dasǝma- “offering”) and was consequently given a word-for-word translation which does not make full sense in Middle Persian.

As to the rendering of dasəmē, it seems preferable to me to accept the reading of ms. K5 <YHBWNm> (subsequently corrected to <YHBWNyt'>, which is the reading of all the other mss.) to be read as dahom “tenth”, written as a Pres.1.Sg. of dādan “to give” due to homophony. This form can be explained as an erroneous translation of OAv. dasəmē (mistaken for Young Avestan (YAv.) dasǝma- “tenth” instead of YAv. dasma- “offering”), according to an interpretation already found in Y.11.9, a YAv. passage where dasmē yōi və̄ yaēθma is quoted at the end of a numerical series 1–10 (cf. Malandra and Ichaporia Reference Malandra and Ichaporia2013: 16).Footnote 12 The later corruption in Y.28.9b of <YHBWNm> to <YHBWNyt'> dahēd (Pres.2.Pl. rather than 3.Sg.) may have been triggered by the presence of <LKWM> ašmāh “you” in the sentence.Footnote 13

The only Pahl. word which could represent the translation of OAv. yōiϑəmā is clearly hassārīh. This erroneous translation is most easily explained by assuming that yōiϑəmā was not interpreted as a verb but rather as an abstract noun in -man- or -ma- from the perfect stem of the verb yat- (yōit-, variant of yaēt-).Footnote 14 Since yat- is usually translated as a verb of motion in Pahlavi,Footnote 15 it does not seem unlikely that the assumed abstract derivative was rendered with a word meaning “direction”.

Admittedly, such an explanation must remain hypothetical to some degree, as long as the sense of the whole Pahl. sentence is unclear. However, I believe that the recognition of an attestation of Pahl. hassārīh “direction” represents a step forward in comparison with previous attempts to read the same word as asarīh “endlessness, abundance” (Dhabhar Reference Dhabhar1949: 20 in the glossary)Footnote 16 or āsārīh “encouragement” (cf. Shaked Reference Shaked1996: 654 fn. 40), which are both otherwise unattested and show no connection with the original Av. text. Likewise, Bartholomae’s emendation <hdyb’lyh> ayārīh “help, assistance” (followed by Malandra and Ichaporia Reference Malandra and Ichaporia2013: 27) should be rejected as unnecessary.

2. The meaning of Manichaean Middle Persian <hs’r> and Pahlavi <hs’l>

The reason why the word written as <hs’lyh> has been transcribed as hassārīh in the previous paragraph is that I think it should be linked with Manichaean Middle Persian (MMP) <hs’r> hassār, translated as “likewise” (adv.), “like” (prep.) or “alike” (adj.) in the main dictionaries.Footnote 17 Before I propose a new etymological interpretation for both words, it is worth analysing the few attestations of Middle Persian (MP) hassār in order to identify all of its semantic nuances. Firstly, some additional passages from the Pahlavi translation of the Gāthās will be introduced in which a spelling <hs’l> corresponding to MMP <hs’r> has mostly remained unnoticed.Footnote 18 Then, the meaning of <hs’r> in its Manichaean occurrences will be discussed.

2.1. Pahlavi Yasna

The Pahlavi translation is quoted excluding the explanatory glosses which, as will be exemplified below, are later additions based only on the older Pahlavi word-for-word translation.Footnote 19

Y.30.9d:

hiiat̰ haϑrā manā̊ bauuat̰ yaϑrā cistiš aŋhat̰ maēϑā.

“si nos pensées se concentrent là où la compréhension est …” (Kell.).

“when (our) thoughts will have become concentrated (on the place) where insight may be present” (Humb.).

MNW hs’l mynšn' YHWWNyt […] ’š TME plc’nkyh AYT […] BYN myhn'

kē hassār menišn bawēd […] ā-š ānōh frazānagīh ast […] andar mēhan

“he whose thought is concentrated (?), there dwells (?) his insight.”

Bartholomae (AiWb: 1763) simply transcribed the word as <a dd a r>, and Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1949: 20 in the glossary, see n. 16) interpreted it as asar: “a-sar mēnišn, continuous thinking, concentrated mind”.Footnote 20 Skjærvø (Reference Skjærvø2000), however, rightly recognized in this word the Pahl. counterpart of MMP hassār. Since hassār is employed to translate the OAv. adv. haϑrā, its most plausible translation is “in the same place”, so, figuratively, “concentrated” with reference to thought. Unfortunately, the sense of the whole sentence both in Avestan and Middle Persian is not fully clear, so it cannot be decided whether the equivalence of haϑrā and hassār is the result of a mechanical word-for-word translation or of a conscious interpretation of the Av. text. The explanatory gloss kū menišn pad dastwarīh ī any dārēd “i.e. (he) has his thought directed by someone else’s authority” is totally unrelated to the Av. text and probably depends on a reading a-sār “without head, without guide” (cf. Av. asāra-, Pahl. transl. +asardār, AiWb: 210). Despite being useless for the purpose of clarifying the meaning of hassār, such a gloss demonstrates that the word belongs to the oldest stage of the MP language and had become unintelligible to later commentators.Footnote 21

Y.32.6a–c:

pourū.aēnā̊ ə̄nāxštā yāiš srāuuahiieitī yezī tāiš aϑā

hātā.marānē ahurā vahištā vōistā manaŋhā

ϑβahmī və̄ mazdā xšaϑrōi aṣ̌āicā sə̄ṇghō vīdąm.

“Puisque, ô Maître qui conserves en mémoire, tu connais par la très divine Pensée les … des (torts) par lequels celui qui en commet beaucoup cherche, en temps de trouble, à établir sa renommée, la définition (de ces torts) doit vous être exposée, (à toi), ô Mazdā, et à l’Harmonie, au moment d’exercer l’emprise sur toi.” (Kell.)

“The many crimes against peace with which (the deceitful one) strives for notoriety, whether he so (strives) with these (crimes) / Thou knowest (about that) through best thought, O Ahura, Thou who rememberest (people’s just) deserts. / Let praise be broadcast for You, O Wise One, and for Truth, in (the domain of) Thy power.” (Humb.)

KBD kynyk’n' kyn' BOYHWNyhyt […] MNW slwt YKOYMWNyt […] AYK AMT OLEš’n' hs’l […] / ’šk’lk' ’m’lynyt’l ’whrmzd […] W ZK Y p’hlwm ’k’s Y PWN whwmn […] / PWN +HNA Y LK LKWM ’whrmzd hwt’yh ZK Y ’hl’yyh hmwhtšn' BRA YDOYTWNyhyt

was kēnīgān kēn xwāhīhēd […] kē srūd ēstēd […] kū ka awēšān hassārFootnote 22 […]/

āškārag āmārēnīdār Ohrmazd […] ud ān ī pahlom āgāh ī pad wahman […]/

pad ēd ī tō ašmāh Ohrmazd xwadāyīh ān ī ahlāyīh hamōxtišn bē dānīhēd […]

“It is desired that the hate of many malicious men is announced, because if they (are) that way, (You) Ohrmazd (are) the true reckoner and the highest knower by means of Wahman. In this realm of Yours, Ohrmazd, the teaching of righteousness will become known.”

Leaving aside the serious exegetical problems in this OAv. passage (cf. Kellens and Pirart Reference Kellens and Pirart1988–91, vol. 3, 84 f.), it seems to me that the Pahl. word-for-word translation reveals a coherent interpretation by the translator: the evil ones should be openly denounced because their behaviour will be judged and punished by Ohrmazd. In particular, the words yezī tāiš aϑā at the end of the first line match perfectly with ka awēšān hassār “(lit.) if they so”. In this case, hassār appears to be employed in the more general meaning of “so, that way”, without any local connotation.

Y.46.8a–b:

This last passage deserves discussion only because it contains a word apparently pointing to Pahl. <hs’l> (registered as <’s’l> in Dhabhar Reference Dhabhar1949 and compared to the previous attestations in Malandra and Ichaporia Reference Malandra and Ichaporia2013: 204):

yə̄ vā mōi yā̊ gaēϑā̊ dazdē aēnaŋhē

nōit̰ ahiiā mā āϑriš š́iiaoϑanāiš frōsiiāt̰

“[…] ou qui soumet mes troupeaux au tort, que le désastre (rituel) ne résulte pas pour moi de ses actes.”

“And if someone aims at my herds to injure (them), / may destruction not reach me through his actions.”

MNW ZK Y L gyh’n' YHBWNyt ’w' OLE kynyk' […]/ LA PWN ZK Y OLE kwnšn' +’w' +mnFootnote 23 +’slyšFootnote 24 l’nynyt’l +HWEydFootnote 25

kē ān ī man gēhān dahēd ō ōy kēnīg […]

nē pad ān ī ōy kunišn +ō man (?) +āθriš […] frāz rānēnīdār +hē

“Who gives injury to my world,

may (he) not direct āϑriš against me (?) as a consequence of his actions.”

In order to establish a plausible reconstruction of the original word-for-word translation of this passage, the manuscript text needs to be corrected in several points. In my opinion, the corruptions here are twofold. First, some mechanical errors took place: the sequence here conjecturally restored as ō man “against me” was corrupted into a spelling pointing to <ANE> an “I”Footnote 26 and the mere transcription of the OAv. hapax āϑriš <’slyš> was erroneously split into two words, originating in some mss. the pseudo-attestation of hassār <’s’l> with which we are concerned. At a later stage, maybe at the time when the explanatory glosses were added, the correct Opt.3.Sg. rānēnīdār +hē was deliberately changed into rānēnīdār ham in order to make sense of the corruptions, disregarding the fact that this would have compromised the correspondence with the original Av. text.Footnote 27 The corruption of <’slyš> into <’s(’)l lyš> (maybe passing through a stage where <’slyš> was written with double <l> for an alleged /l/) was already found in the text read by the later commentators, who explain asā̆r rēš “infinite wound” as kē pad tan ud ruwān rēš kunēd “which causes a wound both in the body and in the soul” (i.e. both in life and in afterlife, forever).Footnote 28 Once again, such a recostruction is rather hypothetical, since it is impossible to know to what extent the Pahlavi translator understood the OAv. text in the first place. Anyway, it should appear from this discussion that the attestation of the spelling <’s’l> in Pahl. Y.46.b is in all likelihood unrelated to the word hassār.

2.2. Manichaean texts and Armenian hasarak

In the Manichaean corpus, the passages where the meaning of <hs’r> hassār is recognizable with enough certainty are only five. They are presented below grouped according to their meaning (the references are based on Durkin-Meisterernst Reference Durkin-Meisterernst2004):

a) hassār as an adverb meaning “in the same place/direction as” (as in Pahl. Y. 30.9 = OAv. haϑrā).

M7981 I V i 28 (Hutter Reference Hutter1992, l. 332), transl. Boyce (Reference Boyce1975: 66 fn. 17):

ud parrōn az zamīg ud āsmān hāmkišwar, ud bēdandar az hān panz dušox ō ērag pādgōs-rōn, az anōh ōrrōntar abar tam dušox, az xwarāsān dā ō xwarniwār pādgōs, hassār wahištāw ēg dēsmān īg nōg dēs.

“beyond the cosmos of earths and heavens, and outside those five hells in the south quarter, nearer (?) than there, upon the darkness of hell, from the east to the west region, corresponding to Paradise, build a new building.”

Although the traditional translation “corresponding to” (Andreas and Henning Reference Andreas and Henning1932 “entsprechend”) is ambiguous, it seems difficult not to give hassār a local meaning (“in the same place as Paradise” or “in the same direction as Paradise”). In fact, the whole passage is aimed at describing – in a fairly cryptic wayFootnote 29 – the place where the “New Building” (dēsmān īg nōg, see Andreas and Henning Reference Andreas and Henning1932: 184 fn. 1) is going to be built.

b) hassār as an adverb meaning “so, likewise, in the same way” (as in Pahl. Y.32.6 = OAv. aϑā).

M7981 II V ii 3, 13 (Hutter Reference Hutter1992, ll. 757–67):

ud hassār-iz hōšag axtar pad ēw māh yak rōz abzawēd […]

“and likewise, the constellation of Virgo exceeds one month by one day”

ud hassār-iz māhīg axtar pad ēw māh yak rōz abzawēd […]

“and likewise, the constellation of Pisces exceeds one month by one day”.

These parallel sentences follow a passage dealing with the relation between epagomenal days and constellations in the Iranian and non-Iranian (here probably Babylonian) calendar.Footnote 30 According to the traditional interpretation, followed in the given translation, hassār is employed as a simple anaphoric adverb marking the continuity of discourse. However, since the purpose of these sentences is to indicate the two periods of the year in which, according to Mani’s interpretation, the surplus days accumulate in the non-Iranian calendar, I regard as equally possible a translation such as “and also corresponding to the constellation of X there is one day in excess over the time of a month”. From this perspective, the meaning of hassār would be more similar to (a), albeit with a temporal nuance. In any case, for practical reasons, in the following paragraph the letter (b) will be used to refer to a meaning “likewise, in the same way”, since it is supported by the attestation in Y.32.6 and is somehow implied in the value (c).

c) hassār as an adjective meaning “equal”.

M7981 II R ii 27 (Hutter Reference Hutter1992, l. 713):

ud rōz dwāzdah zamān bawēd ud šab dwāzdah zamān, ud harw dō āgenēn hassār ēstēnd

“and the day will last twelve hours, and the night twelve hours, and both will be equal together”.

M5750 R ii 20 (Sundermann Reference Sundermann, Wießner and Klimkeit1992: 316 ff.)

imīn senān rōzān pad paymān harw se hassār hēnd

“those three days are all three equal in length”.

Finally, the Arm. loanword hasarak remains to be mentioned, rightly connected by Benveniste (Reference Benveniste1957–58: 56 f.) to MMP hassār.Footnote 31 Benveniste identifies for Arm. hasarak both an adverbial usage “pareillement, en commun”, corresponding to our meaning (b), and an adjectival usage “pareil, égal, commun”, corresponding to our meaning (c).

3. Etymology

The only explicit attempt to offer an etymology of MMP hassār goes back to Henning (Reference Henning1935: 17), who derived it from Ir. *ham-sarda- “of the same kind”, from the same stem as YAv. sarǝδa- “Art, Gattung” (AiWb: 1566 f.). This etymology is clearly based on the adjectival meaning “equal” (c), and is probably influenced by the comparison with Parth. hāwsār “similar, alike” (Arm. loanword hawasar), derived from Ir. *sarda- by Bartholomae (Reference Bartholomae1906: 35 fn. 1, 233).Footnote 32 In my opinion, this explanation is questionable in several respects.

First, it should be emphasized that the prefix ham- undergoes assimilation before -s- only in a couple of verbal forms in which its semantic value is fairly weakened (hassāz- “to make ready” < *ham-sač-, hassūd ppt. “whetted” < *ham-sauH-, cf. Henning Reference Henning1947: 45).Footnote 33 On the contrary, in the great number of bahuvrīhi adjectives formed with ham + noun, assimilation is never found, probably because the derivational process did not cease to be transparent and productive throughout the Middle and New Iranian period and inhibited phonological changes across morpheme boundaries. As a matter of fact, along with forms such as Pahl. hamsāmān “contiguous” and hamsāyag “neighbour” (NP hamsāye) – all without assimilation – an adjective hamsardag “of the same kind” < *ham-sarda-ka- is attested in Pahlavi (cf. CPD: 41), demonstrating that the proto-form postulated by Henning indeed existed, but did not yield hassār as its MP outcome.

In fact, there is no apparent trace of a word sāl (the non-Manichaean counterpart of sār) with the meaning “sort, kind” (< Ir. *sarda-) either in MP or NP. Most likely, the non-South-Western outcome attested in Pahl. sardag prevailed because it was distinguished from the potential homophone sāl “year” (< OP ϑard-, Av. sard-).Footnote 34 As was already recognized by Meillet (Reference Meillet1906–08), it is more plausible that both Parth. hāwsār and MP hassār are compounded with a second member *-sāra- “head”, well attested in the Iranian languages as an ablaut-variant of *sarah- “head” in composition. In particular, there are two possible meanings of Ir. *-sāra- which are relevant to our discussion:

• in compound adjectives with a nominal first element, meaning “having the head of X, resembling X”: e.g. MMP hūgsār “pig-headed”, xarsār “donkey-headed”; Pahl. mēšsār “sheep-headed”, xašēnsār “blue-headed” (name of a bird in HKR 25, “mallard duck” according to Azarnouche Reference Azarnouche2013: 112); NP gāvsār “bull-headed”, dēvsār “demon-like”, etc. (cf. Horn Reference Horn, Geiger and Kuhn1895–1901: 191 f. for further examples); Parth. hāwsār (< *hāvat-sāra-) “similar, alike”.

• in compound adjectives and adverbs meaning “(having the head) directed towards X”: e.g. Av. starō.sāra- “reaching the stars with its top” (name of a mountain); MP nigūnsār “downwards”; Pahl. abāzsār “rebellious”; Sogd. postposition -sār, -sā “towards” (cf. Gershevitch Reference Gershevitch1954: 69 f., 223); Chor. postposition -sār “towards” (cf. Benzing Reference Benzing1983: 568).

In light of the semantic analysis carried out here, it seems plausible to me that the original meaning of hassār was (a) “in the same direction”, i.e. the most concrete and specific, also attested in the abstract hassārīh, and that meanings (b) “in the same way, likewise” and (c) “alike, equal” resulted from a subsequent semantic evolution. A possible etymology which would account for this meaning is OP *haçā-sāra- “(having the head) in the same direction”, with a first element corresponding to Av. haϑrā̆ (Ved. satrā́) “an einem Ort, zu gleicher Zeit, zusammen, zugleich” which is rendered by means of Pahl. hassār in Y.30.9 (see above).Footnote 35 In origin, the OIr. compound was probably an adjective, but due to its almost exclusive predicative usage, it became perceived as an adverb in the Middle Iranian stage, just like MP nigūnsār “downwards”. Since the only meaning attested for hassār as an adjective in MP is “equal, alike”, I am inclined to think that it is the result of a secondary development starting from a somehow faded value of hassār “similarly, likewise” (b). The semantic evolution of this word could then be summarized as follows:

(a) “having the head in the same direction” (adj.) > “in the same direction/place” (adv.);

(b) “in the same way/manner” (adv.) > “so, likewise” (adv.);

(c) “equal, alike” (adj.).

Unlike the simple hassār, the abstract derivative hassārīh seems to have preserved the old local sense “(the same) direction”. Perhaps it is thanks to the retention of a more concrete connotation that the word hassārīh could survive in the Zoroastrian ritual lexicon long enough for us to be able to grasp its meaning and reconstruct retrospectively the history of such an interesting lexical item.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to M. Mancini, A. Cantera, C.G. Cereti, and P.O. Skjærvø for reading a draft of this article and providing me with helpful advice and criticism.

Funding information

This article is a product of the PRIN project “Cultural interactions and language contacts: Iranian and non-Iranian languages in contact from the past to the present” (PRIN 2020, prot. 2020PLEBK4-003, sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Education and Research), Unit at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” whose co-ordinator is F. Pompeo, principal investigator E. Filippone.

Abbreviations

- AiWb

= Bartholomae Reference Bartholomae1904.

- CPD

= MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1971.

- Humb.

= Humbach, Elfenbein, and Skjærvø. Reference Humbach, Elfenbein and Skjærvø1991.

- Kell.

= Kellens and Pirart. Reference Kellens and Pirart1988–91.

- K&K

= Kotwal and Kreyenbroek. Reference Kotwal and Kreyenbroek1992–2009.