Bipolar disorder is accompanied by multiple comorbidities, but substance misuse is particularly common, Reference Merikangas, Herrell, Swendsen, Rossler, Ajdacic-Gross and Angst1 and its co-occurrence often leads to a more pernicious and difficult to treat course of illness. Genetic and family studies also suggest a considerable overlap and interaction of the two disorders and that early-onset bipolar disorder and substance use disorder share at least some common genetic vulnerabilities. Reference Lin, Mclnnis, Potash, Willour, MacKinnon and DePaulo2 Those with early-onset bipolar disorder are also more prone to substance use disorders than those with onset in adulthood. Reference Perlis, Miyahara, Marangell, Wisniewski, Ostacher and DelBello3 In this paper we focus on the role of stressors in the initiation of both bipolar disorder and substance misuse, as well as their role in precipitating mood episode recurrence and addiction reinstatement. Behavioural sensitisation (increased behavioural responsivity) also occurs as a result of the repeated occurrence of (a) stressors, (b) psychomotor stimulants and (c) episodes of bipolar disorder, as well as cross-sensitisation among each of these that may further drive illness progression. Although we focus on bipolar disorder, much of the discussion is equally relevant to recurrent unipolar depression. Reference Berk, Copolov, Dean, Lu, Jeavons and Schapkaitz4

Stressors as precipitants of affective illness, substance misuse onset and recurrence

Very robust clinical and preclinical literature indicate that experience of early life adversity and stressors is a strong risk factor for animals and humans subsequently adopting drug self-administration and addiction. Reference Post and Leverich5 This is best demonstrated for psychomotor stimulants, but is also seen with other drugs including opiates and alcohol. Reference Knackstedt, Melendez and Kalivas6 In a parallel fashion, stressors are also involved in the precipitation of initial episodes of recurrent unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Reference Post and Leverich5 Individuals with a history of early severe psychosocial adversity experience a more severe and treatment-refractory course of bipolar disorder and have an increased incidence of substance misuse. Reference Post and Leverich5

In animal studies, a history of early stressful life experiences can lead to increased stressor responsivity to stressors in adulthood (stress sensitisation). There is considerable evidence for similar phenomena in humans. In the classic study of Caspi et al, Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig and Harrington7 only those individuals who had multiple early life stressors were vulnerable to the occurrence of depression following stressors in adulthood, and this also varied as a function of the type of serotonin transporter that one inherited. In addition, repeated defeat stress in adult animals sensitises to cocaine, and cocaine sensitisation increases the susceptibility to social defeat stress. Reference Covington, Maze, Sun, Bomze, DeMaio and Wu8

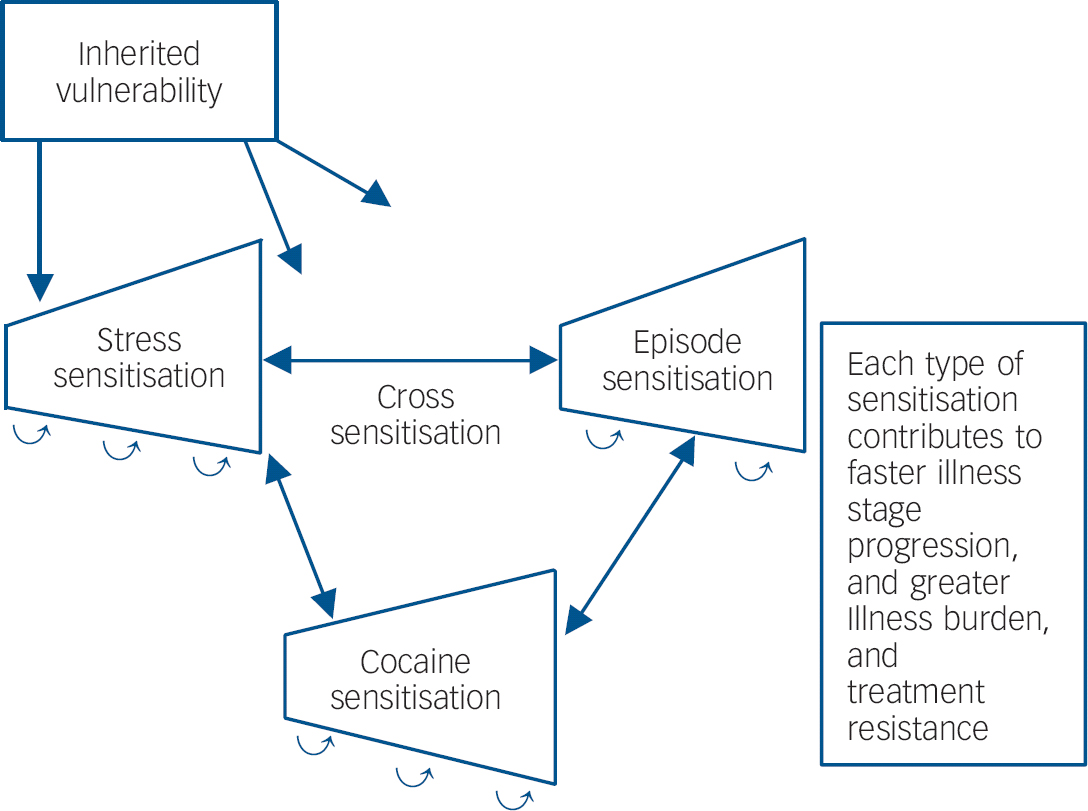

In those with recurrent unipolar and bipolar mood disorders, stressors also appear to be involved in relapse and recurrence of new episodes, Reference Post and Leverich5 as well as relapse into substance misuse in those who have been abstinent. Reference Kalivas and Volkow9 New mood episodes can, in turn, result in renewed drug use. As predicted in the sensitisation model of affective disorders, stressors are more likely to be involved in the precipitation of initial episodes and are successively less crucial for the occurrence of episodes later in the course of illness, which can also begin to occur more autonomously. Reference Post and Leverich5 Thus, there appears to be the potential for a vicious cycle in which stressors, episodes and substances of misuse can each increase vulnerability to the recurrence and magnitude of responsivity to the others (Fig. 1).

Episode sensitisation and increased vulnerability to recurrence

Emil Kraepelin described the tendency for episodes to occur more readily and with a shorter interval of being well in between successive episodes. Reference Kraepelin10 The strongest modern supporting data are those from the Danish case registry showing that vulnerability and latency to relapse vary directly as a function of number of prior admissions to hospital for either unipolar or bipolar depression. Reference Kessing and Andersen11

Fig. 1 Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of illness progression.

Stimulant-induced behavioural sensitisation

Repeated intermittent administration of psychomotor stimulants (amphetamine, cocaine and methylphenidate) results in increasing motor hyperactivity and stereotypy rather than a tolerance pattern of adaptation and decreased behavioural response. Reference Post and Leverich5,Reference Kalivas and Volkow9 Conditioned responses and an environmental context dependency to the behavioural sensitisation is also apparent. Reference Post and Leverich5 This sensitised increased magnitude of response is most readily seen if cocaine is repeatedly administered in the same environmental context, but not when the animal is tested in a dissimilar environmental context. We focus the discussion here on the psychomotor stimulant cocaine, but data also support similar sensitisation effects to amphetamine and methylphenidate, and some components of opiate and phencyclidine (PCP) can also sensitise, as can repeated bouts of alcohol withdrawal.

It has been found that in animals that are taught to self-administer cocaine by pressing a bar to have the drug delivered intravenously it is difficult to extinguish this habit. Reference Kalivas and Volkow9 Although animals will eventually stop bar pressing if cocaine is no longer delivered, they will rapidly reinstate bar pressing if a stressor or cues that cocaine is again available are presented. This animal model of cocaine reinstatement mirrors that in the clinical condition, in which stresses and episodes of mood dysfunction are also known to be precipitants of relapse to cocaine self-administration, even in humans who have been abstinent for long periods of time. Reference Kalivas and Volkow9 Depression and associated dysphoric affect are known precipitants of substance misuse relapse, as are the search for excitement and the poor judgement of mania. Reference Kalivas and Volkow9

Chronic cocaine use not only induces a variety of long-term biochemical and physiological effects, but also induces changes in the shape of the dendritic spines on the medium spiny neurons containing the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens). These GABA neurons receive converging input on these spines from terminals from the frontal cortex (glutamate) and the ventral tegmental area (dopamine). Reference Kalivas and Volkow9,Reference Moussawi, Pacchioni, Moran, Olive, Gass and Lavin12

The change in spine shape following chronic cocaine use is accompanied by a loss of synaptic flexibility and regulation, in that long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), that are normally observed in the nucleus accumbens following high- and low-frequency stimulation of cortical neurons, no longer occur. Reference Moussawi, Pacchioni, Moran, Olive, Gass and Lavin12,Reference Moussawi, Zhou, Shen, Reichel, See and Carr13 This deficit in plasticity occurs in concert with increases in BDNF in the ventral-tegmental area and nucleus accumbens and decreases in BDNF occur in the prefrontal cortex, and each of these changes are important to the manifestation of cocaine sensitisation or reinstated cocaine-seeking. Brain derived neurotrophic factor is co-secreted from glutamatergic neurons. It is crucial for synaptogenesis, the development of LTP and long-term memory. Reference Knackstedt, Melendez and Kalivas6

Mechanistic convergences in animal models and human depression

These observations of differential effects of cocaine on BDNF in different brain regions are of interest in relationship to similar observations occurring following repeated bouts of defeat stress in an animal model of depression, as well as in clinical depression. In this defeat stress model, intruder mice are repeatedly exposed to (but protected from lethal attack by) an aggressive rodent protecting his home cage territory. The intruder animal eventually develops depressive-like behaviours associated with BDNF decrements in the hippocampus and increases in BDNF in the nucleus accumbens. Reference Berton, McClung, Dileone, Krishnan, Renthal and Russo14,Reference Tsankova, Berton, Renthal, Kumar, Neve and Nestler15 If either of the two alterations in BDNF levels is prevented by pharmacological or genetic manipulations, the defeat stress behaviours do not occur.

These regionally selective alterations in BDNF in this animal model of depression are mirrored by similar changes seen in humans with depression who have died by suicide, compared with controls without depression. Brain derived neurotrophic factor decreases in the human hippocampus in people who have taken their own lives have been multiply replicated, and BDNF increases in the nucleus accumbens have been reported. Reference Krishnan, Berton and Nestler16 Taken together, these observations suggest common effects of stressors, episodes of depression and repeated stimulant administration in increasing BDNF in nucleus accumbens and decreasing it in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

If there are some mechanisms in common mediating the long-term biochemical and behavioural effects of stressors, episodes of depressive-like behaviours and substances of misuse, these not only have the potentially unfortunate consequences of each exacerbating the others (Fig. 1), but the potential for a single therapeutic manipulation in one domain dampening or reversing the increased vulnerability or hyper-responsiveness in the other domains as well. A current example of this is N-acetylcysteine. However, many other mechanisms may occur in common in response to repeated stressors, episodes or stimulants as evidenced by prefrontal cortical hypofunction, glucocorticoid hypersecretion and alteration in prefrontal dopamine, that could account for common deficits in executive functioning, and could also become therapeutic targets. Reference Butts, Weinberg, Young and Phillips17

N-acetylcysteine inhibits cocaine and gambling addictions and other habits

In exploring the mechanisms of cocaine-induced behavioural sensitisation, several groups have observed an increase in the number and diameter of spines on the dendrites of the medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens, associated with a loss of LTP and LTD from prefrontal neurons and glutamate hypersecretion. Reference Moussawi, Pacchioni, Moran, Olive, Gass and Lavin12,Reference Kalivas18 Because many of the cocaine-induced neuroadaptations could be prevented by altering the disposition of extracellular glutamate, it was proposed that drugs restoring the function of glial proteins regulating extracellular glutamate might prove a means of reducing the vulnerability to relapse. N-acetylcysteine acts at the glial cystine–glutamate exchanger in the accumbens to promote glutamatergic tone on extrasynaptic inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors, and thereby decreasing the hyperactive glutamate response to the environmental triggers of reinstated cocaine-seeking. Reference Moussawi, Pacchioni, Moran, Olive, Gass and Lavin12,Reference Moussawi, Zhou, Shen, Reichel, See and Carr13 Daily administration of N-acetylcysteine reversed the electrophysiological, morphological, and neurochemical changes in the nucleus accumbens produced by cocaine self-administration, and these reversals and decreased proneness for cocaine reinstatement endured for at least 3 weeks after discontinuing 2 weeks of daily N-acetylcysteine treatment. Reference Moussawi, Zhou, Shen, Reichel, See and Carr13

Based on these preclinical studies, the findings were quickly translated into pilot clinical trials showing that N-acetylcysteine also decreased cocaine, heroin and gambling addiction proneness, and most recently for alcohol and marijuana. Reference Olive, Cleva, Kalivas and Malcolm19 It also decreased other repetitive habits such as those in trichotillomania, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism.

The striatum has been associated with processes of habit memory, which is automatic and unconscious, in contrast to conscious, declarative or representational memory, which involves structures of medial temporal lobe, including amygdala and hippocampus. Reference Mishkin and Appenzeller20 The ventral striatum appears to be involved in memory pertaining to habits that have particular reward value such as substance administration, gambling proclivity, or perhaps even in the initial anxiety reduction occurring in the context of hair pulling in trichotillomania or repetitious behaviours in OCD.

Thus, the N-acetylcysteine reset of the hyper-responsive cued glutamate signal in the nucleus accumbens, a key reward area of the brain, may be a critical component to suppressing overlearnt mechanisms in the habit memory system of the striatum. This sensitised hyper-responsivity in the nucleus accumbens may then be further exacerbated by the inability of prefrontal cortex to exert its normal modulatory control over the accumbens and sensory-motor striatum. Reference Moussawi, Zhou, Shen, Reichel, See and Carr13,Reference Olive, Cleva, Kalivas and Malcolm19 This may have parallels in the clinic wherein patients are unable to make appropriate cortically based risk–benefit evaluations of their behaviour Reference Butts, Weinberg, Young and Phillips17 and become dominated by processes in the unconscious habit memory system. This deficit may be further exacerbated by the finding that the degree of depression in affective ill and in cocaine-addicted individuals is correlated with the degree of decreased activity of prefrontal cortex, as revealed in positron emission tomography scans. Reference Kalivas and Volkow9

N-acetylcysteine in depression, a relationship with habit-based recurrences?

Based on an entirely different rationale of reducing oxidative stress, Berk and colleagues Reference Berk, Copolov, Dean, Lu, Jeavons and Schapkaitz4 in Australia independently assessed the therapeutic effects of N-acetylcysteine in patients who were inadequately responsive to their therapeutic regimens for bipolar disorder. They found that N-acetylcysteine, compared with placebo, exerted remarkably beneficial effects, particularly on depression after a period of 3 months and that these effects were lost following N-acetylcysteine discontinuation at 6 months. Acute antidepressant effects have also been observed by this group in unipolar depression. Berk et al postulated that N-acetylcysteine might be exerting these therapeutic effects because of its antioxidant effects and its glutathione precursor properties. Reference Berk, Copolov, Dean, Lu, Jeavons and Schapkaitz4 However, it is also possible that some of the glutamatergic mechanisms in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortical involved in an overactive habit system, described above for cocaine and a variety of other addictions and habits, could be involved as well.

In the experience of stress sensitisation in defeat paradigm, intruder animals are repeatedly subjected to the imminent threat and cues of an aggressive home cage animal intent on maiming it, eventually leading to the manifestation of depressive-like behaviours. A similar conversion to a habit-based process could also be occurring following multiple experience of episodes of depression. Although the initial episodes of clinical depression are often precipitated by psychosocial stressors, Reference Post and Leverich5 following many depressive recurrences, episodes can also occur more autonomously, and these depressions might increasingly engage the more unconscious and automatic mechanisms of the habit memory system. At this stage of illness evolution, one would hypothesise that effective psychotherapeutic manoeuvres might require targeting the striatal habit memory system, such as the repeated work and practise involved in cognitive/behavioural techniques that have been shown to be effective in unipolar and bipolar depression. Alternatively, work within the reconsolidation window (lasting 5 min to 1 h) after recall of long-term memories may also be effective in substance use and mood disorders. Reference Xue, Luo, Wu, Shi, Xue and Chen21

To the extent that N-acetylcysteine is helping to reprogramme and dampen pathological or overlearnt habit memories based in the nucleus accumbens reward and punishment system based on hyper-reactive glutamate signalling and associated changes in BDNF, it is possible that this action could also account for the therapeutic effects of N-acetylcysteine in depressive recurrences, as well as in substance misuse.

In accord with this possibility, enhancing glutamate clearance from the synaptic space by increasing glial glutamate transporters in the nucleus accumbens was also sufficient to decrease cocaine reinstatement behaviours and reverse some of the behavioural, biochemical and physiological effects of cocaine sensitisation. Reference Knackstedt, Melendez and Kalivas6 Such findings would be consistent with the clinical data that glial numbers and glial activity are reported deficient in autopsy studies of patients with mood disorders compared with controls (at least in cortex), further suggesting the potential benefits of targeting glial deficits in the domains of episode and stress sensitisation. This suggestion converges with the finding that glial, but not neural, toxins are capable of inducing depressive-like behaviours in several animal models.

The epigenetic connection of BDNF to stress, substance misuse and depression

These environmentally induced effects of repeated defeat stress and cocaine on biochemistry and behaviour that persist for indefinitely long periods of time could be mediated by acute alterations in transcription factors activating or repressing gene sequences in DNA to induce new proteins, neurotrophic factors and long-term changes in synaptic excitability. Reference Post and Leverich5 However, additional neurobiological mechanisms for inducing such long-lasting changes in ‘epigenetic’ regulation of gene transcription induced by events in the environment have recently been elucidated. Epigenetic regulation involves environmentally induced changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation and methylation that facilitates or reduces DNA transcription. Reference Tsankova, Berton, Renthal, Kumar, Neve and Nestler15 Typically, DNA methylation is repressive, whereas acetylation of histones (around which the DNA is tightly wrapped) renders DNA less tightly wrapped and, therefore, more easily activated or transcribed. This process has been termed ‘epigenetics’ or ‘above genetics’ because it does not change the inherited nucleotide or gene sequences conveying vulnerability to certain traits and diseases. Since these methyl, acetyl and other small chemical marks tend to be long-lasting, both genetic (inherited) and epigenetic (environmental) effects could contribute to long-term pathological and adaptive biochemical and behavioural changes conveying sustained increases in illness vulnerability. Reference Post and Leverich5,Reference Roth, Lubin, Funk and Sweatt22

In the defeat stress paradigm in adult animals, the decrements in hippocampal BDNF are caused by a repressive epigenetic mechanism involving trimethylation of histone H3K27. Reference Tsankova, Renthal, Kumar and Nestler23 If antidepressants are given that increase hippocampal BDNF and reverse the defeat stress behaviours, it is most interesting that the trimethylation of H3K27 is not reversed. This suggests that the antidepressants increase BDNF through other mechanisms and leave the initial defeat stress-induced epigenetic marks in place. Lifelong persistence of the epigenetic marks related to stressors early in life is likely a mechanism for increased reactivity of animals and humans to subsequent stressors later in life. Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig and Harrington7,Reference Roth, Lubin, Funk and Sweatt22

Although such persistence of epigenetic marks suggests that they might convey relatively permanent alterations in reactivity and vulnerability, drugs are now being explored that directly alter these epigenetic marks. These include DNA methyl transferase facilitators and inhibitors, histone deacetylases and an entire group of drugs known as histone deacetylase inhibitors, one of which is valproic acid. Reference Bredy, Wu, Crego, Zellhoefer, Sun and Barad24

Roth et al Reference Roth, Lubin, Funk and Sweatt22 also found that rodent neonates subject to poor mothering experiences exhibit lifelong decrements in BDNF in prefrontal cortex, based on increases in DNA methylation of the BDNF promoter. If these animals are given zebularine, an inhibitor of DNA methylation, the BDNF decrements in the cortex and associated behaviours do not occur. Interestingly, DNA methylation is also involved in cocaine-induced behavioural sensitisation in mice, and the sensitised response is again blocked by the methylation inhibitor zebularine.

When animals are subjected to early repeated, prolonged (3 h but not 15 min) maternal separation, they develop lifelong increases in corticosterone and anxiety behaviours, in part based on deficient expression of the glucocorticoid receptor based on methylation of its DNA promoter. Parallel findings occur in humans who take their own life and had a history of physical or sexual abuse in childhood; they had an increase in glucocorticoid receptor methylation compared with those without these early stressors. Reference McGowan, Sasaki, D'Alessio, Dymov, Labonte and Szyf25

Clinical implications

The long-term consequences of increased reactivity (sensitisation) to recurrent stressors, episodes and substances of misuse and their cross-sensitisation to each other have a number of important implications for clinical therapeutics. To the extent that each of these processes is environmentally mediated, it is amenable to current efforts at reducing or preventing their occurrence and the consequent long-term adverse effects on behaviour. The long-term persistence of the sensitisation effects and many of their epigenetic mechanisms makes it all that more important to consider the early and consistent initiation of long-term prophylactic treatment in bipolar disorder in an effort to avoid illness progression by the further recurrence of new episodes, the accumulation of stressors and the all-too-common acquisition of substance misuse comorbidities. Reference Post and Leverich5

In recurrent unipolar and bipolar disorders, there appears to be not only a more adverse course of illness in those with childhood-onset compared with adult-onset illness (such as more episodes, substance misuse and disability), Reference Perlis, Miyahara, Marangell, Wisniewski, Ostacher and DelBello3,Reference Post and Leverich5 but long delays to first treatment that are inversely correlated with age at onset of illness. Reference Post, Leverich, Kupka, Keck, McElroy and Altshuler26 This delay to first treatment for mania or depression in bipolar disorder is independently correlated with a more adverse outcome in adulthood as seen by more time and more severity of depression, less time euthymic and the experience of more episodes in prospectively rated adults.

Thus, it would appear imperative to begin to address recurrent mood disorders from the perspective of the potential of the progressive and sensitisation effects of accumulating mood episodes with their potential for cross-sensitisation to stressors and substances of misuse, in order to refocus efforts at earlier and more effective long-term prophylactic strategies. The potential cross-sensitisation among stressors, episodes and substances of misuse raises the specter of an adverse positive feedback mechanism in each domain of illness vulnerability, with recurrences of each not only increasing responsivity to themselves, but also to the others (Fig. 1). The potential liabilities of this process may be particularly relevant to people with bipolar illness living in the USA. Reference Post, Leverich, Kupka, Keck, McElroy and Altshuler26,Reference Post, Leverich, Altshuler, Frye, Suppes and Keck27 Compared with patients from Germany and The Netherlands, those from the USA experience: (a) more stressors not only in childhood, but in the year prior to illness onset, and prior to the last episode; (b) more substance misuse comorbidity; as well as (c) more episodes, and more rapid cycling (four or more episodes/year). Each of these could engage sensitisation mechanisms and propel illness progression, which is further confirmed by findings of increased treatment refractoriness in those from the USA compared with Germany and The Netherlands. Reference Post, Leverich, Altshuler, Frye, Suppes and Keck27 Thus, the convergence of more stressors, episodes and substance misuse in the USA may lead to greater accumulation of epigenetically based vulnerability and severity of illness progression than in some European countries.

The partially converging mechanisms discussed in this paper also yield a new perspective on the frequent co-occurrence of substance misuse comorbidities in affective disorders and the linkage of childhood stressors to early onset and more rapid-cycling illness, as well as the adoption of substance misuse. Thus, it appears more than mere coincidence that there is a high incidence of substance misuse comorbidities in recurrent affective disorders and that stressors play aetiopathological roles in the onset and relapse of both syndromes.

Although substance misuse comorbidities vastly complicate the course and treatment of recurrent affective illness, we hope that the clinical and theoretical exposition of some convergent pathways illustrated in this paper (such as changes in BDNF, cued-glutamate reactivity in the nucleus accumbens, possibly engaging habit memory systems) also offer a hopeful perspective about prevention as well as new modes of therapeutic intervention, such as with N-acetylcysteine currently and perhaps epigenetics in the future. While awaiting such future possibilities to arrive, this overview suggests the importance of employing available clinical strategies and public health measures. These might include reconfiguring efforts aimed at more frequent and consistent long-term prophylaxis, employing stress immunisation and coping techniques, and initiating primary prophylaxis for substance misuse in youth with bipolar disorder who have not yet started misusing drugs but are at high risk for doing so. Reductions in, or prevention of, any one of the domains of stress-, episode- or substance misuse-sensitisation is likely to yield therapeutic benefits in each of the other domains as well.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.