The 1945 White Paper on Full Employment, produced by the Curtin-Chifley Government, was the founding document of Australia’s postwar prosperity. As the full-employment policy put forward by the Australian Labor Party at the 2022 election observes:

In 1945, Prime Minister John Curtin released the Full Employment White Paper, which charted a course for the Australian labour market in the post-Second World War era. Curtin knew that if Australia was to prosper after a period of great upheaval it needed to rewrite the social contract, and to be meaningful, full employment needed to be at the at the core of it.

This policy echoed a statement by then opposition leader Anthony Albanese https://anthonyalbanese.com.au/media-centre/full-employment-white-paper-australian-jobs-summit

Australia is at a similar turning point, and a White Paper on Full Employment will help us to navigate it. The White Paper will be informed by an Australian Jobs Summit that will be convened as one of the first actions of an incoming Labor Government.

The Albanese Government’s implementation of this commitment has been ambiguous and sometimes contradictory. As Kalecki (Reference Kalecki1943) presciently observed, the prospect of a government committed to full employment is often unwelcome to employers for whom a labour market with full employment is experienced as ‘skill shortages’. Responding to this concern, the Jobs Summit was renamed the ‘Jobs and Skills’ Summit and the working title of the White Paper was modified from ‘White Paper on Full Employment’ to ‘White Paper on Employment’.

Nevertheless, when the White Paper eventually emerged under the title Working Future – White Paper on jobs and opportunities, (Australian Government 2023) it included a commitment to a ‘new, bolder full employment objective’ defined as an economy where everyone who wants a job is able to find one without having to search for too long. This definition, which is consistent with the ordinary language meaning of ‘full employment’, is explicitly contrasted with the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU), which forms the basis of macroeconomic policy as implemented by the Reserve Bank of Australia. This concept is not related to the absence of involuntary employment but rather refers to an unemployment level consistent with stable inflation.

In this paper, the conflict between the NAIRU and full employment as it is ordinarily understood is discussed in a historical context. The Working Future White Paper is then assessed with a focus on how the government seeks to reconcile a full-employment commitment with a monetary policy framework based on continued reliance on the NAIRU concept.

Background

The 1945 White Paper

The Curtin Government came to office in 1941, Australia’s darkest hour, when the country was threatened with invasion. Yet the government was not content to put politics aside in the interests of the war effort. Rather, victory in war and in peace was seen as inseparable. The Curtin Government introduced a wide range of social welfare benefits and increased existing benefits.

The paper began by drawing a striking contrast between the disaster of the Great Depression and the national mobilisation achieved in wartime:

Despite the need for more houses, food, equipment and every other type of product, before the war not all those available for work were able to find employment or feel a sense of security in their future. On average during the 20 years between 1919 and 1939, more than one-tenth of the men and women desiring work were unemployed.

In the worst period of the depression, well over 25 per cent were left in unproductive idleness. By contrast, during the war, no financial or other obstacles have been allowed to prevent the need for extra production from being satisfied to the limit of our resources.

It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

The central message of the 1945 White Paper was that mass unemployment was not the unfortunate outcome of economic forces but the result of policy choices. As the experience of the war had shown, a government with sufficient determination could achieve and maintain full employment.

The White Paper set out an explicitly Keynesian program of demand management, saying ‘The essential condition of full employment is that public expenditure should be high enough to stimulate private spending to the point where the two together will provide a demand for the total production of which the economy is capable when it is fully employed’.

The era of full employment

During the 25 years following the release of the White Paper, the commitment to full employment and price stability was delivered in practice most of the time. An upsurge in inflation in the early 1950s was controlled by tight fiscal policy, without producing a substantial increase in unemployment.

The central point of Keynesian economics was that a market economy could be characterised by sustained high unemployment and price deflation because of inadequate demand. But Keynes recognised the converse point that excess demand, while being associated with low unemployment, could lead to inflation. This was clearly recognised in the White Paper.

This policy will need careful administration. Not only will it be necessary to offset a tendency for spending to decline, but governments must also ensure that total expenditure is not too high. As long as there are unemployed resources to be drawn into production, increased expenditure will produce a higher level of employment, but once full employment has been reached, production is at its maximum. A higher level of expenditure would then cause prices to rise, with adverse effects on the stability of the economy and on the welfare of large sections of the community.

For nearly three decades, Keynesian macroeconomic policies yielded a combination of full employment and price stability. Occasional episodes of inflation were checked by policies to reduce excess demand. Conversely, demand was stimulated when unemployment threatened to increase.

Monetary policy played a secondary role in economic management. The commitment to full employment, made in the White Paper, was reflected in the legislation establishing the Reserve Bank of Australia. The official objectives of the Reserve Bank are stated as:

-

1. the stability of the currency of Australia;

-

2. the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and

-

3. the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia.

The Reserve Bank was independent in the sense that it did not take direction from the government. However, the Secretary of the Treasury was a member of the Reserve Bank’s board, and the ‘official family’ were expected to work together to coordinate macroeconomic policy. The Treasurer’s power to overrule the Governor of the Bank, while never exercised, reflected the elected government’s ultimate responsibility for macroeconomic policy and the commitment to direct policy to the maintenance of full employment.

The breakdown of full employment

However, with the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1971, Australia, like the rest of the world, experienced ‘stagflation’, a combination of high unemployment and high inflation. The most widely accepted explanation put forward by Milton Friedman was that with entrenched expectations of inflation, the Phillips curve trade-off could not be sustained in the long run. This analysis led to the abandonment of full employment and its replacement with the ‘natural rate’ concept put forward by Friedman and later renamed the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment or NAIRU. The implications of the NAIRU are discussed below.

The Accord period of the 1980s saw reductions in both unemployment and inflation, raising hopes that the prosperity of the Keynesian era might be restored. These hopes were dashed by the recession that began in 1989, and the high unemployment that persisted after output growth recovered. Even after 1989, the belief that full employment could and should be restored remained influential until the 1990s. As late as 1993, the Keating Government released a draft policy entitled Restoring Full Employment (later published as Working Nation.)

The Howard Government, elected in 1996, abandoned full employment as a policy goal (Quiggin Reference Quiggin1997). Except for a brief period in his final term, the official unemployment rate was above 6 per cent throughout Howard’s Prime Ministership.

The end of any commitment to full employment, even as an aspiration, came with the abandonment of fiscal policy as a policy instrument and the shift to a strong form of central bank independence, along with the adoption of inflation targeting as the basis of monetary policy. In Australia, this shift was formalised in the first Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy (1996), an agreement between the Treasurer and the RBA Governor. The statement enshrined a 2–3 per cent inflation target as the central element of monetary policy. The statement made clear that employment was now a secondary consideration, saying

These objectives allow the Reserve Bank to focus on price (currency) stability while taking account of the implications of monetary policy for activity and, therefore, employment in the short term. Price stability is a crucial precondition for sustained growth in economic activity and employment.

This framework was maintained through subsequent Statements up to and including that of 2016. Through this period, the inflation target was mostly met, except for the years before the pandemic when inflation fell short of the target. Unemployment rates fluctuated but remained well above the rates considered consistent with full employment in the past.

Implicit in the statement was the replacement of a full-employment objective with a focus on maintaining unemployment near a putative ‘natural rate’ of unemployment, later renamed the NAIRU. In the following section, the contrast between this concept, based on the operation of monetary policy, and measures of full employment derived directly from the job market.

What is full employment?

As with other policy targets like ‘price stability’, full employment cannot be given a precise definition. As long as people are free to change jobs, and employers are able to dismiss or retrench workers, there will be at least some unemployment. The crucial question is whether full employment should be conceived as an outcome in the labour market or as a condition for the maintenance of an inflation target.

Labour market definition

On ordinary understandings of the term, the definition of full employment should be determined by conditions in the labour market.

Unemployment is commonly classified along the following lines

-

(a) Frictional unemployment arises as a result of workers changing jobs, as a result of their own choice, dismissal, or because existing firms close and new firms open.

-

(b) Structural or mismatch unemployment arises when the skills of unemployed workers do not match those demanded by employers with vacancy

-

(c) Skill deficiency unemployment arises if some workers do not have the skills required to produce enough to compensate employers for the costs of employing them

-

(d) Demand deficiency unemployment arises when there are not enough jobs available to employ those seeking work

If unemployment is either frictional or structural, the number of unemployed workers should be roughly equal to the number of unfilled vacancies. When a worker leaves their job to look for a new one, they become unemployed, but their departure creates a vacancy, so the balance remains unchanged. Similarly, skills mismatch should have broadly symmetrical effects on unemployment and vacancies.

Skill deficiency unemployment may be addressed through training programmes. There should also be access to disability benefits for those whose disabilities cannot be adequately addressed through trainings.

Full employment should be defined as a situation where there are roughly equal numbers of unemployed workers and unfilled jobs. Such an outcome arises when all unemployment is frictional, arising from workers leaving their jobs to search for new ones. Each such separation creates one vacancy and adds one to the number of unemployed. Conversely, when an unemployed worker finds a job, both the number of vacancies and the number of unemployed are reduced by one.

A formal version of this argument is presented by Michaillat and Saez (Reference Michaillat and Saez2022), who propose the more general rule that the best estimate of full employment at any given time is

That is, the full-employment rate u* may be estimated as the geometric mean of the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate. For the US, Michaillat and Saez (Reference Michaillat and Saez2022) estimate u* = 4.2%, and claim that this value has been stable over the period from 1930 to 2022. Their argument is summarised as follows (p. 2):

We propose that the best marker of full employment is the efficient unemployment rate, u*. We define u* as the unemployment rate that minimizes the nonproductive use of labor—both jobseeking and recruiting. The nonproductive use of labor is well measured by the number of jobseekers and vacancies, u + v. Through the Beveridge curve, the number of vacancies is inversely related to the number of jobseekers. With such symmetry, the labor market is efficient when there are as many jobseekers as vacancies (u = v), too tight when there are more vacancies than jobseekers (v > u), and too slack when there are more jobseekers than vacancies (u > v). Accordingly, the efficient unemployment rate is the geometric average of the unemployment and vacancy rates: u* = √uv.

What is crucial in this definition of full employment is that it depends entirely on conditions in the labour market, rather than on macroeconomic variables such as GDP growth and inflation.

The concept of full employment must be modified somewhat when a substantial portion of jobs are part-time, as has been the case since the large-scale entry of women into the workforce in the 1970s. Part-time employment is often preferred by workers with parental responsibilities. However, under-employment arises when workers seeking full-time employment can only find part-time jobs. Working Future gives a good discussion of these issues.

The NAIRU: unemployment as a constraint on inflation

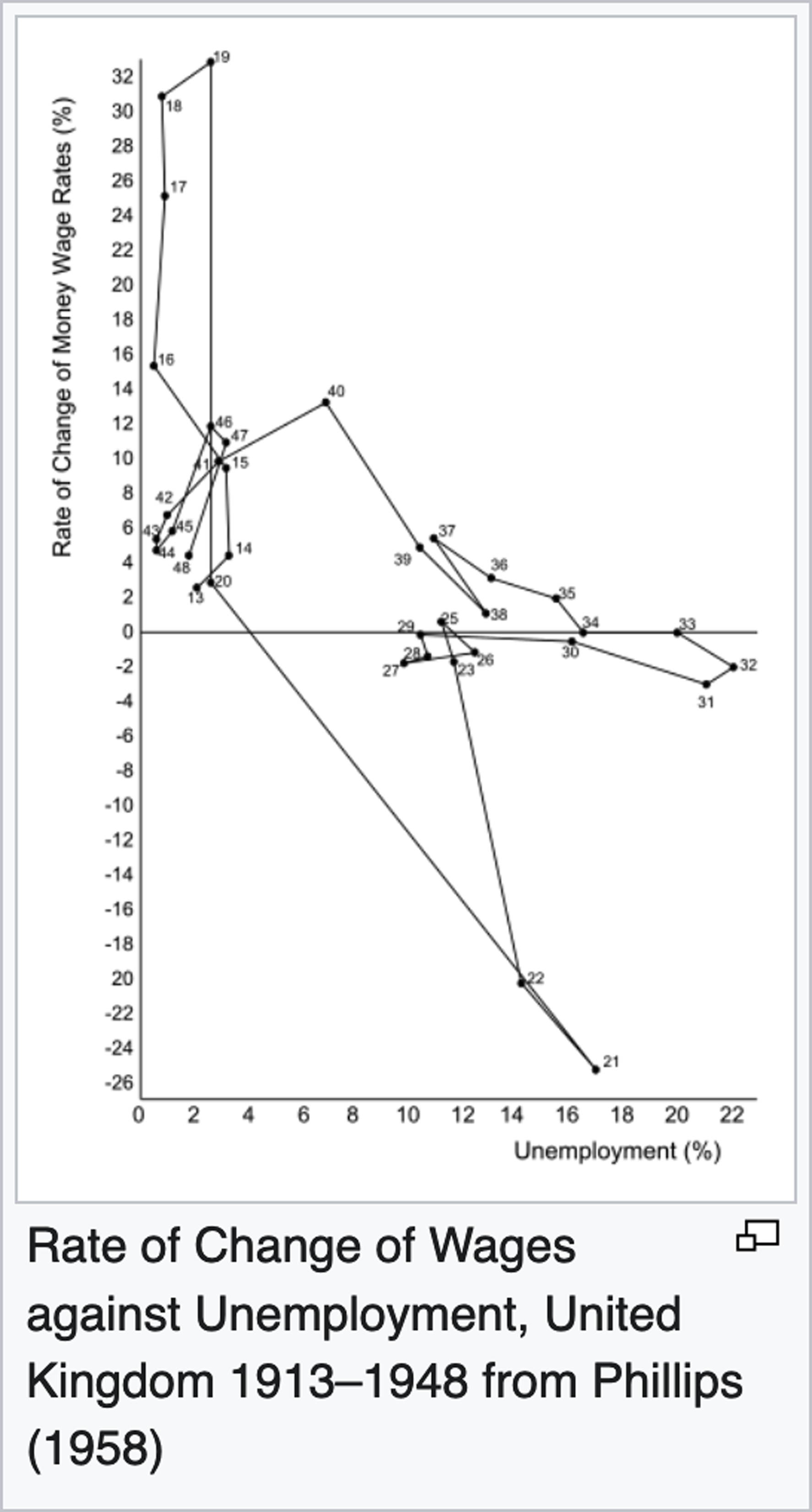

The labour-market-based definition of full employment differs radically from the concept that has dominated economic policy since the 1990s, that of the natural rate or NAIRU. The history of the NAIRU goes back to 1958 when NZ and Australian economist, AW (Bill) Phillips (Reference Phillips1958), published graphs plotting rates of unemployment against rates of money wage growth in the UK first between 1861 and 1913, and then between 1913 and 1948.

A line of best fit for the period 1861–1913 was given by a convex curve, which became known as the Phillips curve. As was expected on the basis of Keynesian economics, this curve showed that, when unemployment was low, wages tended to rise more rapidly. A similar pattern, though with some striking outliers, was observed for the period 1913–48.

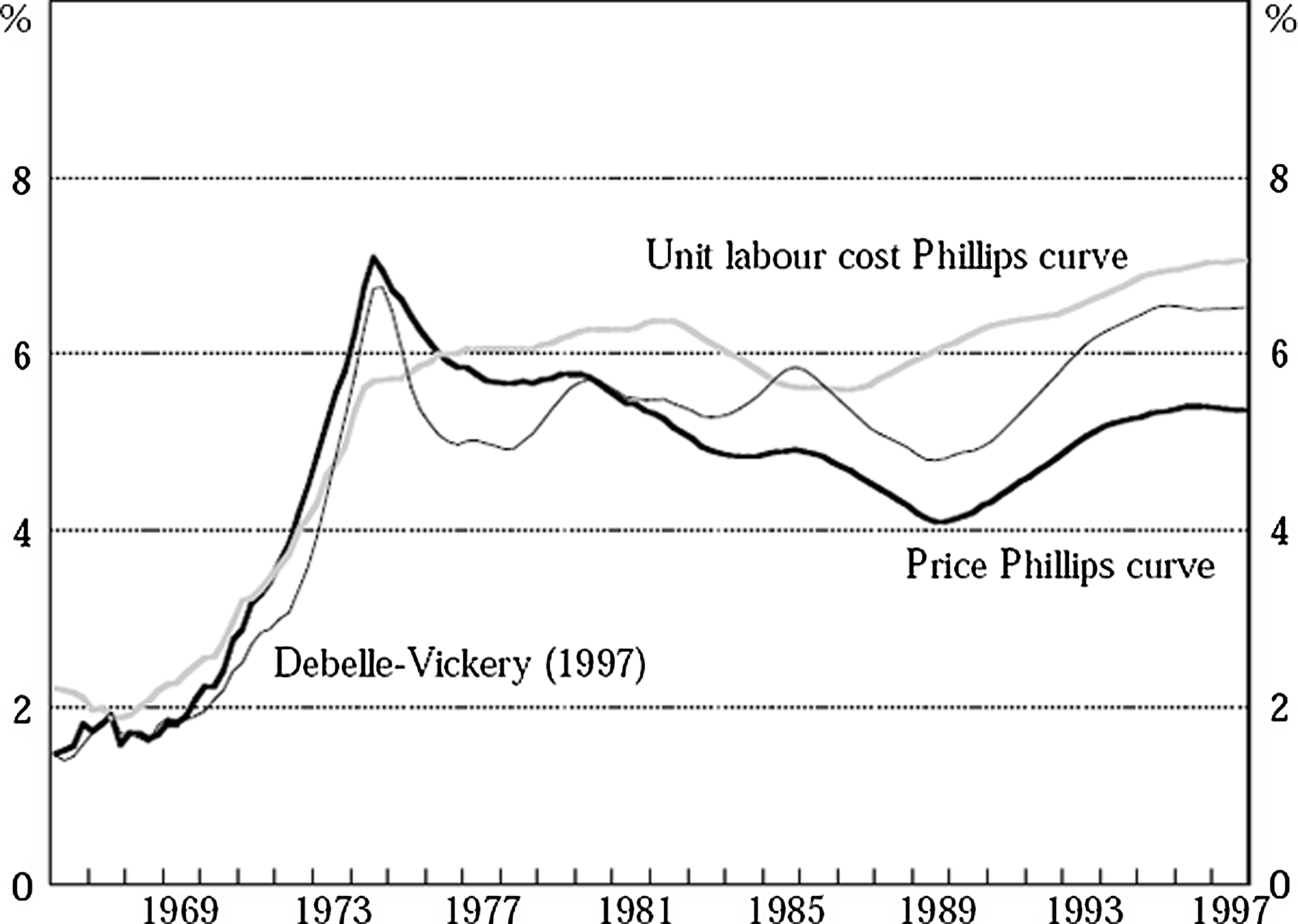

Although Phillips’ original curve referred to wage growth, many subsequent writers on this topic examined the relationship between unemployment and price inflation. At the time, this change did not make a great deal of difference. The long-standing constancy of the wage share of national income meant that real wages grew in line with productivity, at around 2 per cent per year. Putting this another way, the rate of wage growth was typically about 2 per cent higher than the rate of price inflation. The conflation of wage and price inflation became problematic after 1970, when the wage share began to fluctuate, briefly rising sharply and then declining over many decades.

An appealing but misleading interpretation of the Phillips curve is that it represents a menu of choices available to policymakers, who can decide to trade off higher inflation against lower unemployment or vice versa. While leading Keynesians such as Samuelson and Solow (Reference Samuelson and Solow1960) presented the curve more cautiously, this interpretation was widely held in the early 1960s, giving rise to optimism about the possibility of ‘fine-tuning’ macroeconomic policy (Heller Reference Heller1966).

In his 1968 AEA Presidential Address, Friedman (Reference Friedman1968) criticised the trade-off interpretation, arguing that it took no account of expectations. In Friedman’s view, once workers and employers adjusted their expectations to take account of increased inflation, any benefit in reduced unemployment would disappear. It followed that unemployment could not, in the long run, be shifted away from what Friedman called the ‘natural rate’, that is

the level that would be ground out by the Walrasian system of general equilibrium equations, provided there is embedded in them the actual structural characteristics of the labor and product markets. (Friedman Reference Friedman1968, 8)

The term ‘natural rate’ was found to be problematic and has generally been replaced by the NAIRU acronym. Apart from that change, and some tweaks to the mechanisms by which expectations are adjusted, Friedman’s model remains central to macroeconomic policy today.

The NAIRU model justifies central banks and Treasury departments in disregarding unemployment since it implies that, in the long run, they can do nothing to move unemployment away from the NAIRU.

When the rate of unemployment falls below the NAIRU, wages increase more rapidly than is consistent with stable inflation. The rate of inflation increases. As expectations adjust, if unemployment remains low, inflation accelerates. The process ends either in hyper-inflationary collapse or with the adoption of a contractionary monetary policy, which increases unemployment temporarily above the NAIRU, until inflation declines.

In this framework, the short-term benefits of reducing unemployment below the NAIRU are outweighed by the costs of the necessary subsequent deflation. It follows that the achievement of the inflation target, on average, will come as close as possible to the goal of maintaining full employment.

However, just as Friedman discredited the idea of a stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation, subsequent experience has discredited the idea of a stable NAIRU, dependent only on the structure of labour markets. The most important evidence concerns ‘hysteresis’, that is, the fact that if external or policy shocks raise the rate of unemployment, high unemployment will be sustained even after the shocks end (the term originally refers to the ‘memory’ effect by which a piece of metal that has once been magnetised is more easily magnetised in the future). The result of hysteresis is that estimates of the NAIRU tend to move in line with the actual value of unemployment, adjusting with a lag.

For several decades after Friedman’s address, estimates of the NAIRU were generally increasing. Gruen et al. (Reference Gruen, Pagan and Thompson1999) provide a range of estimates for the period from the development of the NAIRU concept to the end of the 20th century.

As unemployment rates gradually declined after 2000, estimates of the NAIRU followed suit (Ruberl et al Reference Ruberl, Ball, Lucas and Williamson2021). Moreover, estimates for the period from 1990 to 2000 were revised, to show a gradual decline rather than the increase estimated at the time.

While inflation remained low and stable, the NAIRU model was barely tested, until the Covid-19 pandemic. Experience of inflation since the onset of the pandemic appears inconsistent with standard interpretations of the NAIRU model. The upsurge in inflation following the lifting of Covid restrictions coincided with low unemployment rates. However, the NAIRU model (unlike Keynesian interpretations of the Phillips curve) requires causality to run through labour markets, with higher wages driving price inflation. In the recent inflation, nominal wage growth has remained at low levels, consistent with stable inflation.

The decline in inflation rates since 2022 is even more striking. Like other central banks the Reserve Bank raised interest rates as a response to higher inflation. Inflation rates fell, but, once again, the transmission mechanism envisaged in the NAIRU model did not apply. On the contrary, inflation decelerated despite historically low rates of unemployment.

The Working Future White Paper then came at a time when the NAIRU model was overdue for reassessment.

Working future: an assessment

After decades in which macroeconomic policy focused primarily on inflation, the announcement of a renewed commitment to full employment, made by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in 2021, was a major step. Labour’s election campaign included not only a commitment to full employment but the promise of a Jobs Summit leading to a new White Paper on Full Employment, modelled on that of 1945.

Upon taking office, the Labor Government backed away from this commitment. The Jobs Summit was relabelled a ‘Jobs and Skills Summit’ and much of the discussion focused on supposed skills shortages. This was a misnomer. The problem faced by employers was not a shortage of particular skills but the difficulty of filling vacancies of any kind in a situation of full or near-full employment. After decades in which the number of unemployed workers routinely exceeded vacancies, employers found this situation difficult to accept.

An even more consequential change was the removal of the word ‘Full’ from the name of the proposed White Paper. The decision to break with Labor’s history on this crucial issue seemed to portend the abandonment of the entire process.

The response to the Review of the Reserve Bank was also disheartening. Not only was the NAIRU framework endorsed but the Treasurer abandoned the power to override Reserve Bank decisions. This power, which required an explicit statement to Parliament, was never used but remained as a statement of the ultimate responsibility of government for economic management.

With this background, it seemed unlikely that the White Paper would contain anything of value. Relative to these low expectations, Working Future came as a pleasant surprise.

A submission to the process from the Per Capita group (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Lloyd-Cape and Quiggin2022) made five proposals, of which all but the suggested title were adopted in some form

-

Recommendation 1: The title of the document should be the White Paper on Full Employment.

-

Recommendation 2: The Australian Government should renew its commitment to Full Employment as a policy objective.

-

Recommendation 3: Full employment policy will require a return to the active use of co-ordinated fiscal and monetary policy, implemented through a revised Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy.

-

Recommendation 4: Full employment should be defined as a situation where there are roughly equal numbers of unemployed workers and unfilled jobs.

-

Recommendation 5: The Federal Government should establish a broad review of what changes to monetary and fiscal policy would be required in order to meet a full-employment objective.

Most importantly, Working Future stated a goal of full employment defined in terms of the actual experience of workers in the job market, namely ‘an economy where everyone who wants a job is able to find one without having to search for too long’. This implies that the number of vacancies should be similar to the number of unemployed workers, as suggested in Recommendation 2.

The studies undertaken as part of the process that produced Working Future included an extensive examination of unemployment and policies for full employment as suggested in Recommendation 5.

Finally, a new Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy was issued in December 2023, attempting a resolution of the conflict between a public policy commitment to full employment and a monetary policy framework based on the NAIRU. The extent to which this attempt is likely to succeed is discussed in the following section.

Full employment and public policy

The central problem for Working Future is the need to reconcile a labour-market-based definition of full employment with a monetary policy framework based on the NAIRU. As is observed in

Conceptually, the NAIRU represents the level of unemployment consistent with stable wage or price inflation; it is a measure of where the current maximum sustainable level of employment may lie rather than a guide for the Government’s long-term objective of sustained, inclusive full employment.

The crucial contrast here is between the ‘long-term’ objective of full employment and the ‘current’ need to keep unemployment rates at or near the NAIRU.

Most of the policy measures discussed in Working Future may be seen as attempts to improve the functioning of labour markets in the hope that the NAIRU will be reduced to a rate consistent with sustained, inclusive full employment. The list of such measures includes a range of worthwhile initiatives

-

1. Strengthening economic foundations

-

2. Modernising industry and regional policy

-

3. Planning for our future workforce

-

4. Broadening access to foundation skills

-

5. Investing in skills, tertiary education, and lifelong learning

-

6. Reforming the migration system

-

7. Building capabilities through employment services

-

8. Reducing barriers to work

-

9. Partnering with communities

-

10. Promoting inclusive, dynamic workplaces.

To the extent that such measures can be implemented successfully, their effects are likely to be felt only in the long term.

In the meantime, the Reserve Bank will maintain its focus on a 2–3 per cent inflation target. However, the effect of the full employment is to give some real effect to the recommendation included in the RBA review that the Reserve Bank should publish information regarding its performance on unemployment.

This is spelt out in more detail in the 2023 Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy

The Government’s objective is sustained and inclusive full employment where everyone who wants a job can find one without searching for too long. The Reserve Bank Board and Government agree that the Reserve Bank Board’s role within this is to focus on achieving sustained full employment, which is the current maximum level of employment that is consistent with low and stable inflation. The Reserve Bank Board commits to regularly communicating its assessment of how conditions in the labour market stand relative to sustained full employment, drawing on a range of indicators and recognising that full employment is not directly measurable and changes over time.

Despite the carefully inserted qualifications at the end of the quoted paragraph, this reporting requirement will create substantial difficulties for attempts to implement contractionary monetary policies in pursuit of the inflation objective. Assuming such policies produce an increase in unemployment, the Reserve Bank must either

-

(a) admit to policy failure; or

-

(b) make an explicit claim that the rate of ‘sustained full employment’ (that is, the NAIRU) has risen, relative to existing rates of unemployment, which have been consistent with declining inflation.

Had a reporting requirement of this kind been in place during the below-target inflation period in the years before 2019, it seems likely that pressure for more expansionary policies would have been enhanced.

Unsurprisingly, the Statement makes no mention of the active use of coordinated fiscal and monetary policy. Such coordination is inconsistent with the strong form of central bank independence implicit in the very existence of a periodically renegotiated statement.

Nevertheless, the interaction between monetary policy and fiscal policy cannot be ignored. During the period of monetary policy dominance, that interaction has been mostly antagonistic. The perceived role of the central bank has been to rein in the fiscal profligacy of governments.Footnote 1 The underlying assumption was that discretionary fiscal policy is not a useful tool of macroeconomic policy.

Reflecting on the experience of the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid pandemic, Working Future challenges this position.

The discussion of macroeconomic policy in Working Future represents a significant endorsement of discretionary fiscal policy, as well as an appreciation of the role of automatic stabilisers

Discretionary fiscal policy interventions can complement the role of automatic stabilisers and play an important role in limiting the costs of significant adverse economic shocks on the economy, businesses and labour markets. There may be a more important role for fiscal policy to help manage economic shocks during times of severe contractions in aggregate demand, when monetary policy is at its limits or its transmission channels are constrained. This is more likely to be relevant, for example, during times of acute crisis or in the event of adverse supply shocks. Fiscal policy can also be more targeted than monetary policy.

This statement is broadly consistent with the actual practice of Australian Governments, including the use of large-scale fiscal stimulus in response to the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is inconsistent with the dominant rhetorical emphasis on the need for budget balance and on the pre-eminent role of monetary policy, administered by an independent central bank.

Concluding comments

As then Opposition Leader Albanese (Reference Albanese2020) observed the Labor Government that produced the 1945 White Paper

‘They knew national leadership in times of crisis was about more than mere preservation, it was a question of vision, of courage’.

Similar vision and courage are required today.

Australia has the opportunity to return to the decades of full employment achieved under the policies set out by the Curtin and Chifley Governments. However, if the policy framework that has prevailed since the 1990s is left unchanged, this opportunity will pass us by. Sooner or later, contractionary monetary policy will produce a return to high unemployment, with a corresponding upward adjustment to the NAIRU.

Working Future is not the radical break with the existing policy framework implied by Albanese’s pre-election rhetoric. However, restoring a meaningful definition of full employment as an objective of government policy is a step in the right direction.

John Quiggin is Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland. He is prominent both as a research economist and as a commentator on Australian public policy.