Through presence or absence, indigeneity has long been at the center of Bolivian politics, culture, and nationalism.Footnote 1 It carries immense social import. Yet what Indigenous means and who gets counted as part of this umbrella category has never been clear or static. Although Bolivia's racial and ethnic categories seem as etched in stone as the Andes themselves, individual classification is fluid and situational based on sociocultural markers that change over time. These markers include occupation, literacy, dress, language, surname, and residence. Individuals may move through these categories (and not only in one direction) over the course of their lives. This fluidity, combined with changing meaning and the valorization of indigeneity at the national and international levels, has led to wild fluctuations in official statistics on race since independence. The social construction of these categories came to the fore in 2012 when the census reported that Bolivians who identified as Indigenous had dropped to 40 percent of the population, down from 62 percent only eleven years earlier. International observers were left wondering, where did all the Indigenous people go?Footnote 2

As Laurent Dubois has argued, the categories themselves must be at the forefront of any discussion of race; they are “social artifacts that demand” explanations rather than “generate” them.Footnote 3 Investigating a category's construction and deployment is essential to understanding its history and power. Since the 1990s, cultural anthropologists have debated the many factors that influence the changing uses and connotations of Indigenous identity categories in Bolivia.Footnote 4 Historians have more limited sources for understanding the self-identification of people outside of leadership positions.Footnote 5 They have analyzed cultural production, petitions, speeches, laws, and publications to expose the often contradictory ideas about race and ethnicity circulating among Creole and Indigenous elites.Footnote 6 Others have explored Indigenous intellectuals’ construction of race-based social movements.Footnote 7 Historians have also productively studied censuses, education systems, and public health initiatives to understand how different administrations applied these ideologies.Footnote 8

Building on these approaches, this article uncovers the institutional practices that surrounded the assignment and inscription of race in Bolivian military records. As a central institution of the state, the military played an important role in shaping racial categories and ideologies. When officers or clerks assigned each man to a race, they drew on cultural knowledge and personal experience to make abstractions into seemingly fixed and concrete identity categories. Drawing on conscription records, correspondence, and military-justice proceedings, this article examines the way that military officers and conscripts serving as clerks during Bolivia's liberal and revolutionary eras deployed race thinking in the paperwork used to track the men who registered for obligatory military service. Through analysis of official military documents and internal record-keeping, I argue that the institution categorized conscripts by race through the 1950s but omitted this data from public-facing documents starting in the 1920s. The article thus contributes to understandings of how ideology, individual decision making, and bureaucratic structures impact the use of racial categories.

The state shapes identity categories through the paper technologies it produces as part of bureaucratic efforts to understand and control the population.Footnote 9 These technologies are created as its agents develop and use categories to guide their efforts to collect information about the people they administer. State agents then use the data to fashion legal identities and issue demographic statistics through the census and other reports. The process of creating categories and applying them to individuals produces paperwork that certifies identity, nationality, and the completion of requirements, such as paying taxes, voting, serving in the military, and completing roadwork. The very form of these documents determines the results and serves to regularize and formalize categories. What information is collected and what is omitted? In what order is data presented? Are answers free form or are the categories preprinted? Do individuals supply their own information or does a state agent determine some of the answers for them? Through attention to the changing form of the paper technologies related to military service, this article probes the complicated nature of ethnoracial categories and the contradictions between administrations’ ideology and the daily practice of state agents.

Military Manifestations of Liberal Race Thinking

Although racialized hierarchies laid at the heart of their nation-building projects, Latin American elites tended to reject legal discrimination based on race. Many espoused ideas of classical liberalism, which, in acts of willful ignorance, presumed equal and unmarked citizens. They tried to refrain from using race to classify members of a society imagined as being on a trajectory toward becoming a “modern”—understood as homogenous—nation. As Mara Loveman has argued, such states constructed “formally inclusionary nations, but on deeply hierarchical grounds.”Footnote 10 These ideas impacted early twentieth-century Bolivian statecraft, sometimes resulting in explicit prohibitions on recording race. Yet race was so central to daily life that state agents produced racial data in a variety of documents and statistics.

Unlike in parts of Latin America where nationalist efforts led to the celebration of mestizaje, Bolivian intellectuals like Alcides Arguedas adopted prevailing ideas of scientific racism to condemn it as racial degeneration.Footnote 11 In 1899, Creole Liberal elites seized power after winning a civil war with the help of Aymara allies. The new administration moved the capital from Sucre to La Paz. They then worked to legitimize the highland region while simultaneously disavowing the allies who had brought them to power. As E. Gabrielle Kuenzli explains, this resulted in paradoxical efforts to denigrate the contemporary Aymara while making the Indigenous past central to nationalist narratives.Footnote 12 Although more virulent strains of biological determinism were certainly present in Bolivia, most Creole Liberals emphasized environmental determinism, denounced abuse, and expressed hope for cultural assimilation.Footnote 13 The authors of the 1900 census thus confidently predicted the “gradual disappearance of the Indigenous race.”Footnote 14 Yet many Liberal politicians were also rural landowners who depended on Indigenous labor. An important faction soon expressed fear of educational efforts, arguing that the Indigenous population would be easily swayed by caudillos and endanger the republic's democracy.Footnote 15

These contradictory ideas about race, nationalism, and Bolivia's path to modernity also marked rhetoric surrounding the project of universal male military service, which was implemented soon after the Liberal Party gained power.Footnote 16 Liberals frequently insisted that military service would be a sacred duty shared by the male population as whole. A shortened term of service, prohibitions on replacements, and the end of exemptions for tribute-paying Indians theoretically meant that the sons of prominent families, artisans, and Indigenous peasants would meet during service to forge a unified nation in the barracks.Footnote 17 Upon announcing the 1907 conscription law that would stand with only minor modifications until 1963, President Ismael Montes declared that “everyone without distinction of race or class” must be prepared “to give his blood in tribute to the nation.”Footnote 18 He further promised that the barracks would become “a practical training ground for equality where the son of the powerful brushes up against the son of the artisan and the Indian.”Footnote 19

Policies related to military service masked hierarchies of race and social class and presented them as based on personal merit. Stating that “the odious distinction between social classes should not be recognized in the barracks,” President Montes decreed that soldiers would be promoted based on only two factors: their level of education and their good conduct in the ranks.Footnote 20 Unwilling to recognize the institutional racism that prevented most Bolivians from accessing formal education, Montes presented these criteria as merit-based and equally attainable by all.

Documents authored by Bolivian military officers show “Indigenous” to be a marked category in a way that “Mestizo” and “White” were not. When they wrote letters or testified about conscripts who they perceived to be Indigenous, officers consistently identified them as “indios” or used the phrase “the indígena” to precede the person's name.Footnote 21 In similar documents concerning non-Indigenous men, I found them identified by race or social class only once. In that case, Major Alcibiades Antelo identified Alejandro Higuera and Hilarión Sánchez as Mestizos. However, he did so only to explicitly contrast them with two other deserters he described as “pure Indians, ignorant.”Footnote 22 Even more telling is a desertion report from 1911. In it, the prefect of La Paz ordered the capture of four miners who had deserted from the Viacha arsenal. He attached the personal information (filiación) for all four, but only one, an Indigenous man named Agustín Pacaza, was identified by race.Footnote 23 Officials lived in a society defined by the racialized difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, with Indigenous perceived to be inferior. They thus explicitly labelled conscripts who fit their definition of Indigenous.

Both officers and politicians presented conscription as a tool to nationalize and assimilate the Indigenous population. President Montes promised that military service would “incorporate that race [Indigenous] into the political life of the country and civilization in general.”Footnote 24 Three years later, Minister of War Andrés Muñoz assured Congress that conscription was already resulting in “the regeneration of the Indigenous race.”Footnote 25 Officers testified that military training was causing “a complete transformation in the ideas, habits, and customs” of men brought into the institution.Footnote 26 Officials promised that conscripts would learn Spanish, basic literacy skills, and modern hygienic methods during their time in the barracks. Not surprisingly, these statements make clear the assumption that Indigenous men needed to be improved by military service. For example, Minister of War Néstor Gutiérrez noted in 1914, “A few days after his admission to the barracks, the Indian, before retiring and timid, transforms into a soldier, handsome and self-controlled. It is noteworthy how, in the course of a couple months of military education, large modifications in conscripts’ character and temperament come about, equalizing all conditions and producing tenacity even in those least favored by nature, putting them on par with the most capable and intelligent.”Footnote 27 These comments reveal both environmental and biological ideas about race, with the minister of war promising, somewhat paradoxically, that military service would “fix” both cultural traits and those assumed to be inherent.

Leaders thus took additional measures to encourage Indigenous men to register and serve. Decrees in January and December of 1908 and ministerial resolutions in 1913 and 1916 gave Indigenous men more time to register without being pursued as evaders.Footnote 28 They used familiarly paternalistic tropes about Indigenous ignorance to explain these targeted exceptions, citing “the special condition of the Indigenous race” and ordering landowners and civic and religious authorities to carefully explain the rules and penalties to the Indigenous population.Footnote 29

Military conscription took hold during a period marked by widespread uprisings and organized activism from Indigenous communities for land, education, access to markets, and an end to abusive practices.Footnote 30 While state actors hoped military service would help solve these problems by making men less Indigenous, they simultaneously feared the repercussions of arming and training men they did not identify with or trust. They worried that Indigenous conscripts might refuse to repress rural unrest or might use their skills against the state after shedding their uniforms. Oruro Prefect Eduardo Diez de Medina expressed these concerns in 1914: “[The Indian] shows himself to be proud, and in some cases defiant, when he returns to his land, forming perhaps a danger for the security of the internal order.” He suspected that Indigenous men who were eager to enroll had ulterior motives, hypothesizing that they had been “seduced by the prospect of becoming skilled in the use of arms and getting mixed up in aggressive adventures.”Footnote 31 Haunted by the specter of race war, Bolivian elites feared both the disease and their own proposed cure.

Recording Indigeneity in the Early Twentieth Century

Although elites’ liberal ideology discouraged them from collecting data on race, indigeneity appeared frequently in military documents in the early twentieth century.Footnote 32 State agents collected personal and demographic information (filiación, antecedentes, and generales) during the registration and exemption process as part of efforts to construct the bureaucratic apparatus necessary to administer and perhaps someday enforce the conscription system. They also implemented a new paper technology, the military service booklet, which detailed the man's personal information and record of military service.Footnote 33 Because of provisions that demanded it be produced to vote or be employed in the formal sector, this document served as a mechanism to coerce men, especially members of the middle and upper classes, to regularize their status by serving or obtaining an exemption.Footnote 34 The form and content of this paperwork merit detailed analysis because they reveal administrative concerns and the categories that government officials used to understand the population.

Bolivia's 1907 military service law called for military and civilian officials to set up tables every August and September in each departmental capital, provincial capital, and canton to register all eighteen-year-old men.Footnote 35 Registration involved data collection; they were to record the man's first and last names, place of birth, age, marital status, skin color, physical marks, “trade or profession,” residence, and registration date.Footnote 36 The continued mandate to record skin color apparently raised questions because of its association with race. A later clarifying memorandum by Minister of War José S. Quinteros delved further into the question of skin color, instructing state agents to note “the exact color of the skin on the face, that is to say, if he is pale (pálido), olive-skinned (trigueño), dark-skinned (moreno), etc., without taking race into account under any circumstance.”Footnote 37 In addition to showing Liberals’ aversion to generating racial data, his comments reveal the assumption that race existed and could easily be identified (or ignored).

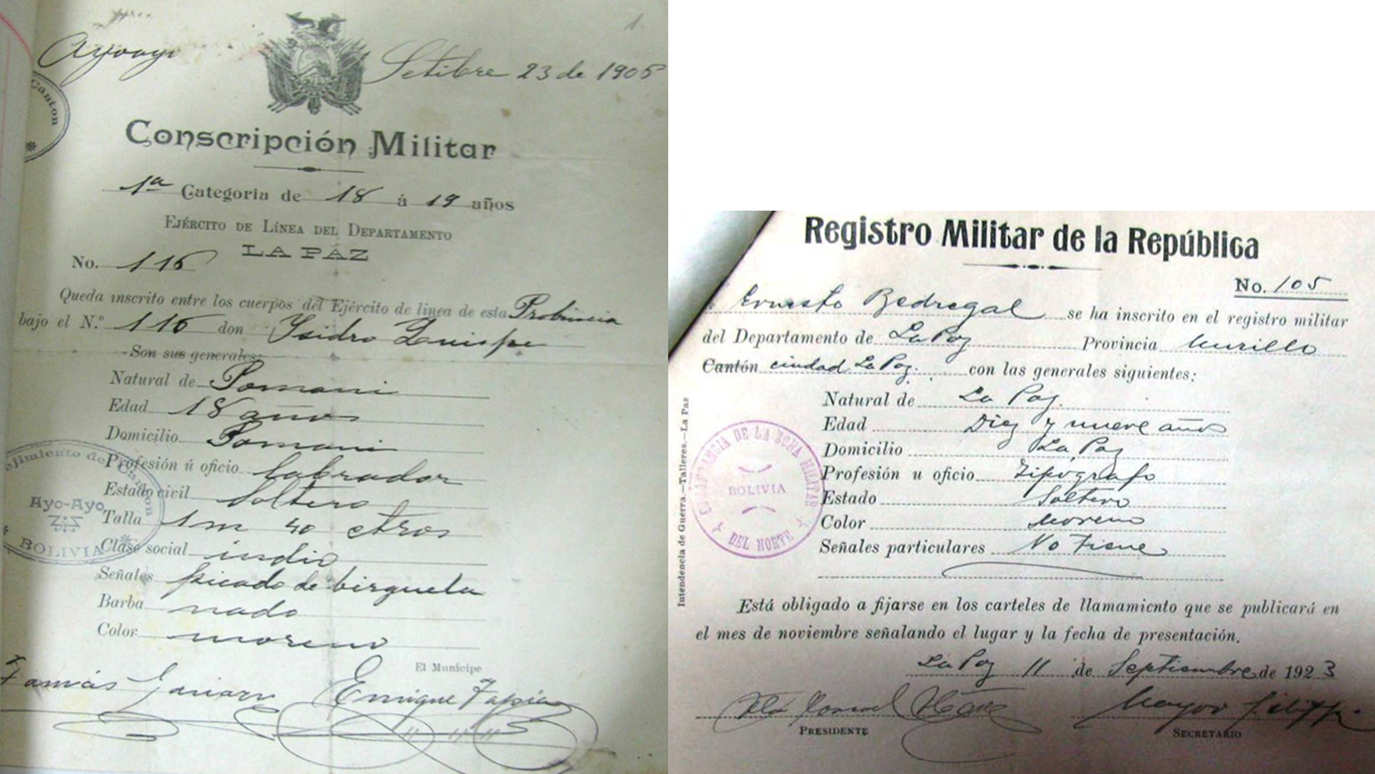

Again prohibiting the inscription of race, Quinteros instructed agents manning registration tables to record conscripts’ “social class,” self-consciously reassuring them that this classification was necessary to avoid confusion between men with the same names and to help the state locate the individual in question.Footnote 38 However, the detailed guidelines and regulations surrounding the 1907 military service law make no mention of social class. Quinteros's instruction to record it suggests the power of paper technologies to shape practice. I suspect that agents were recording this information because they were still using older preprinted forms. As shown in Figure 1, the “social class” category was present in military registration sheets from 1906 but absent by the 1920s.Footnote 39 Until new registration sheets were printed, agents would have continued collecting the information dictated by the older ones.

Figure 1 Military Registration Sheets from 1905 and 1923

Source: September 1905 military conscription sheet with line for social class attached to petition of “indígena Isidro Quispe” to the prefect of La Paz, February 21, 1908, Prefecture-Exped box 164, d. 32, ALP; September 1923 military registration sheet without line for social class attached to petition of Ernesto Bedregal to the prefect of La Paz, September 21, 1923, Prefecture-Exped box 254, d. 11, ALP. Reproduced with permission by the Archive of La Paz.

In the same 1907 document, Minister of War Quinteros suggested that agents choose from “indígena, artisan, cholo, gentleman” to describe social class.Footnote 40 Indígena has a long history as a fiscal, administrative, and legal category during the colonial period, and differentiated duties related to the category persisted well into the Republican era.Footnote 41 The meanings of Cholo have changed depending on time and context. Generally, the term signifies people of Indigenous or mixed descent who do not display some of the sociocultural markers associated with indigeneity.Footnote 42 Quinteros's list of social classes highlights how Bolivia's ethnoracial terms overlapped with class and occupational ones. By making “Indigenous” and “Cholo” into classes rather than races, he implied that the categories were cultural and environmental rather than biological. The minister of war drew on Liberal ideology that rejected racial difference while simultaneously asserting the importance of the categories that shaped his world in early twentieth-century Bolivia. He therefore presented these categories as class-based and mutable rather than race-based and immutable. Yet the categories’ very names revealed them to be profoundly racialized.

On paper, intellectuals might have been able to parse out differences between ethnicity, race, and social class. In practice, however, these categories were profoundly interrelated and imbricated. This divide between theory and practice allowed Quinteros to insist that the state agents manning registration tables ignore race while instructing them to record Indigenous or Cholo as a person's social class. As Rossana Barragán notes: “Even though race was conceived of in biological terms of origin and descendants, in practice the criteria were occupational because occupations were themselves already racialized.”Footnote 43 The profound association between Indigenous status and rural agricultural labor made impossible the idea of an urban Indian or an elite Indian. In the eyes of those doing the categorizing, Indians who left rural areas were no longer Indigenous.

Tellingly, indígena appeared as an occupational category in reports to Congress about the results of conscription efforts. From 1907 to 1912, the War Ministry chose to include in its report data on just three key factors: how many men registered from each department, their marital status, and their occupation.Footnote 44 As reflected in Table 1, these occupational tables were organized hierarchically, beginning with lawyers and ending with artisans and then indígenas. The categories were more specific for prestigious occupations, differentiating between medical, business, accounting, and theology students but lumping together all artisans and all rural workers. The information collected at registration tables was far more granular, including more than fifty different less-prestigious occupations like hatmaker, carpenter, bricklayer, blacksmith, day laborer, and farmworker.Footnote 45 The structuring of these tables reveals that state actors were more concerned with knowing details about the men presenting for service from the upper rungs of society than about the working-class men who constituted most of the ranks.

Table 1: Aggregate Professional Categories Used in Reports on Conscripts, 1907-1912

Data on the 1909 cohort was not presented in either the Boletín Militar or the minister of war's report to Congress. This table includes all conscripts who presented for service, including those exempted through the lottery. The year listed is the year that conscripts presented for service. A dash (-) indicates that the occupational category was not included in that year's report. The order varies slightly between reports, but the order presented is the most common. Because the summary table for the 1907 cohort seems to have a calculating error that misrepresented the number of artisans as 187 and of indígenas as 413, the data included in this table are based on the departmental breakdowns instead. Sources: Boletín Militar 1907, 300-302; Memoria de Guerra 1908, iv-ix; Anexos de Guerra 1910, clvii-clix; Anexos de Guerra 1911, 136-137; Anexos de Guerra 1912, 85-87.

The use of indígena as an aggregate professional category supports Barragán's conclusions about the racialization of professions.Footnote 46 Notably, none of the registration lists, individual sheets, or military service booklets I have found list a conscript's profession as “indígena.” Instead, agricultor, labrador, jornalero, colono, and peón commonly appear on the same list, leading me to believe that these categories were self-reported or that different scribes used different terms to signify agricultural labor.Footnote 47 The lack of other aggregate categories related to agriculture suggests that the people generating the statistics for these reports categorized all lower-status conscripts involved in food production as indígena. The sons of large landowners likely appeared as professionals, students, or as secondary graduates. Only in 1912, the last year that the conscription report was published, did it include the category “agriculturalist.” It did not explain how those thirty-three men differed from the two hundred indígenas recorded below them, but the category's placement suggests that it was considered a higher social status than indígena. The explicit inclusion of the descriptor “illiterate” after artisan and indígena in the 1910 report confirms perceptions surrounding the social status of these categories.

The coding of indigeneity as an occupation and Minister of War Quinteros's defensiveness stand in stark contrast to the documentary mandate in the 1900s and 1910s to record race on the most prominent military document of the time. Upon discharge, each conscript received a military service booklet that documented their service record and personal information. The version issued to conscripts between 1909 and 1919 (and perhaps longer), recorded race on the top line of the third page.Footnote 48 The booklet included race under physical appearance (señales exteriores) rather than with place of birth, domicile, and parentage (antecedentes), which suggests that the form's designers understood race to be manifested through physical appearance. The placement of race at the top of the list of physical characteristics implies that race was the primary and most important identifying characteristic. In fact, when race appeared on military documents, it was always the first characteristic, topping descriptors like skin color, hair color, height, and weight.

Paper technologies during the Liberal era consistently included Indigenous status. However, the category to which this status belonged was varied; it appeared as a response to prompts for race, social class, and occupation. This malleability points to the centrality of indigeneity in Bolivia. It also betrays Creole elites’ uncertainty about their nationalist narrative and how to deploy social science categories in an international context dominated by eugenics. In the coming decades, however, Indigenous status both solidified into a racial category and disappeared from public military documents.

Omitting Race from Public-Facing Documents

Despite the documentary prominence of race in the early twentieth century (or perhaps precisely because of it), the designers of the military service booklet eliminated the line for race in the 1920s. This meant the state was no longer racially marking men, at least publicly. When asked to show their military documents by patrols, at the polls, or when called up for war, former conscripts would present a paper technology that no longer categorized them by race. Yet race by no means disappeared from official records. A variety of sources from military and prefecture archives suggest that authorities routinely generated and transmitted racial data at least through the mid-1950s but did not include it in public-facing documents or those designed to be archived.

The form of military service booklets changed over time, with new versions issued in the 1920s, after the Chaco War (1932–1935), and again in the 1940s. None of these later booklets included a place for race to be recorded.Footnote 49 The initial omission of race from military service booklets in the 1920s came as part of a larger paring down of the physical description of conscripts that eliminated reporting on four of nine features.Footnote 50

The military service booklet ventures into the world alongside the former conscript whom it documents; its archival counterpart is the military service sheet, which lists the same personal and service information as the booklet. Literate conscripts or noncommissioned officers serving as clerks in each military unit filled out this form, and then the relevant authorities signed it and sent it to the Territorial Registry of the Ministry of Defense, which houses service sheets dating from demobilization after the Chaco War through the most recent cohort of discharged conscripts. This archive's primary function is to verify men's service or legitimate exemption when they run for office, request documents, or otherwise need to prove compliance with the obligatory military service law.Footnote 51 The service sheets took on a variety of forms and documented different information over the years; however, none of the more than two thousand preprinted service sheets that I sampled from this archive for the years 1936 through 1974 offered a place to classify race.Footnote 52

These public and formally archived documents imply that the military stopped systematically producing racial data on conscripts in the 1920s. Yet isolated sheets from the late 1930s and early 1940s suggest otherwise. Although the form did not solicit conscripts’ physical description, the clerk who filled out service sheets for the Vegara Fifth Artillery Regiment in 1938 used the space designated for medical information to record race along with a description of each conscript's eyes, nose, and hair.Footnote 53 I also found four mimeographed documents from 1938 and 1940 that list both race and skin color as part of conscripts’ physical description.Footnote 54 Are these documents anomalies, the products of errant clerks who recorded extraneous information? Or are they evidence of the continued classification by race during the recruitment process?

Prefecture and military-justice records support the latter explanation. In the 1940s, race persistently appeared on the less formal paper technologies that are in these archives. One example is the desertion notices (parte de deserción) used to locate conscripts who had left the ranks without permission. Rather than professionally printed forms like the military service sheets and booklets, desertion notices were typically mimeographs of typed forms.Footnote 55 This allowed for variability over place and time. An officer or clerk typed or handwrote the conscript's name, address, parentage, physical description, and the circumstances surrounding his desertion. The unit then sent desertion notices to the minister of war, who forwarded them to the departmental prefect, who in turn sent them to the relevant local authority. Reflecting the practice of reporting race in military service booklets at the time, all but two of the sixty-five notices (97 percent) I found from the 1910s included racial data.Footnote 56 More surprising is that all but two of the twenty-nine desertion notices (93 percent) I found from 1940 to 1950 also reported race.Footnote 57 The clerks who filled out victim reports for accidents and deaths also included the conscript's race in addition to other personal information.Footnote 58 Decades after the category's elimination from the booklet and archived service sheets race was still topping the list of conscripts’ physical characteristics in these documents designed for internal use.

The categorization of conscripts by race whenever a form called for it suggests that racial data was still being routinely generated during the recruitment process on a paper technology that moved with the conscript during his service. Before investigating these questions about race, I had assumed that the service sheets served this function, but the appearance of racial information elsewhere led me to examine more closely all the sheets in my sample.Footnote 59 The results suggest that documentary practices varied widely in the late 1930s and the 1940s. Handwriting and typing indicate that most units filled out the sheet in its entirety at the time of discharge whereas some others seem to have filled it out partially upon assignment to the unit, stored it locally, and then completed it upon discharge.Footnote 60 Generally, sheets sampled from same unit in the same year were filled out similarly, but my analysis found no consistency across years within the same unit.Footnote 61 The lack of uniformity in form and procedure is consistent with my previous conclusion that, even after the Chaco War, the Bolivian military lacked the capacity or will to establish an effective bureaucratic regime.Footnote 62

The units that filled out the entire service sheet after completion of service had to use another instrument—that likely included racial data—to keep track of conscripts’ information. This perhaps explains the four mimeographed documents mentioned above. These look like service sheets but differ in three ways: the forms are mimeographed rather than preprinted, they do not solicit discharge information, and they include lines for both race and skin color in the physical description. The first two factors demonstrate the internal purpose of the form. The third suggests that the military was deliberately leaving race out of public-facing documents. These four sheets accidentally ended up archived alongside the same conscripts’ official service sheets likely because these men had been reassigned from their original units to the Ministry of Defense. I suspect that many units used mimeographed sheets like these that included race, transferred the information to the preprinted sheets at the time of discharge, and then destroyed the original. Reflecting the heterogeneity of practice at the time, other units used the service sheet that would eventually be archived.

The Military Register supports the theory that, at least at particular registration sites, the military was systematically creating racial data and then omitting it from the public record. Also archived at the Territorial Registry, this register is a bound volume of the original registration tables from each of the recruitment sites around the country. The size of four standard sheets of paper, these preprinted tables were filled out by hand or typewriter after the close of recruitment. Each man who presented for service, including those medically ineligible or dismissed through the lottery, had his information recorded on a row. The form, in use until 1953, reported each conscript's personal information, medical appraisal, and physical description.Footnote 63 It did not provide a column for race. However, at certain recruitment sites, clerks classified conscripts as M for Mestizo, I for Indigenous, or B for White. Between 1947 and 1952, race was assigned to more than 27,500 conscripts, which was about half of the men whose information made it into the archive.Footnote 64 Clerks in this period bisected the profession column to add an additional column for race. This sandwiched information about the conscript's race between his occupation and literacy status, signaling the continued association of these factors. This placement stands in contrast to the desertion reports and mimeographed registration records, which consistently listed race as part of conscripts’ physical description.

The high percentage of tables with this information and its uniform placement show that recording race in the Military Register was a widespread practice. It was most common in the Cochabamba department, but I found no other consistency in registration sites, handwriting, or the names of the officers who signed for the 561 tables that included race.Footnote 65 Were military personnel only generating racial data at these sites? Or were they generating it at all sites but only entering it on the registration tables at some? The consistent inclusion of race in the desertion, death, and victim reports drawn from registration data leads me to suspect the latter: that military officials classified men by race during the registration process, but only some clerks were told to draw in a column for it when filling out the registration tables. The others did not include it because the preprinted table did not solicit it.

The omission of race from mass-printed forms like the registration tables, service sheets, and military service booklets was likely a conscious decision made near the top of the state hierarchy. This design choice reflected liberal ideals of equality that rejected racial classification. However, evidence from the Military Register, service sheets, and desertion reports makes a strong case that, during the 1930s and 1940s, the standard practice throughout Bolivia was still to assign a race to each man who registered for military service.Footnote 66 Was this decision made at an equally high level? I suspect so, but it also could have resulted from continuance in clerical practice, with recruitment commissions unthinkingly reproducing forms that included race. Either way, the military was producing racial data on conscripts during this period but not including it in public documents.

Recording Race in the MNR's Bolivia

Many things about Bolivia changed profoundly after April 1952, when the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement's (MNR) coup plot turned into a popular revolution from below. Although led by elite and middle-class reformers, the party gained significant support in the mines, factories, and countryside. After enacting universal suffrage, the MNR responded to pressure to nationalize the largest tin mines and, more reluctantly, enact a widescale agrarian reform that titled land to “those who work it.”Footnote 67 According to popular lore, the MNR destroyed the military and attempted to rebaptize the Indigenous population as peasants. Although the latter was hyperbole, much work remains to understand the meaning and deployment of racialized categories in the MNR's Bolivia.Footnote 68 This section contributes to ongoing scholarly efforts by analyzing data-generation practices in the military, showing that clerks continued to systematically categorize conscripts by race until 1959, when race abruptly disappeared from the Military Register.

Scholars’ understanding of race in revolutionary Bolivia has become increasingly nuanced. Reflecting dominant global trends in the 1950s and 1960s, the first wave of scholarship emphasized the stigma associated with Indigenous status and assumed that assimilation would benefit the individual and nation.Footnote 69 Beginning in the 1970s, as Indigenous movements around the world gained prominence, the coding of this assimilationist vision for Bolivia shifted from celebratory to condemnatory, with scholars detailing the devasting material effects of the MNR's “reformist mestizo project.”Footnote 70 However, recent research is complicating understandings of both the party's ideology and the effects of its policies. Looking at the MNR's cultural project, Matthew Gildner argues that leaders drew on and promoted Indigenous traditions to develop a nationalist cultural project with an “inclusive veneer.”Footnote 71 In terms of effects, Carmen Soliz argues that the MNR's assimilationist discourse contrasted with its agrarian policies, which actually strengthened Indigenous communal structures.Footnote 72

The revolution caused intense upheaval in Bolivia's military, leading to drastic reductions in budget and size. The officer corps also underwent a significant renewal with about half discharged and others returning from exile.Footnote 73 Contrary to popular belief, the new administration did not abolish and rebuild the military.Footnote 74 The events of 1952 did leave a significant mark on conscription records, however. A host of military service sheets from the 1952 cohort are stamped “with insufficient instruction” and show that many conscripts received discharges in late April 1952 instead of serving a full year.Footnote 75 Although a similar number of men registered for service in 1953 as had in previous years, the Military Register reveals the process to have been an uneven affair. In the outlying departments of Beni, Pando, and Santa Cruz, where conscripts primarily worked on road and colonization efforts, men registered and entered the ranks in January, as they had before the revolution. In La Paz, Cochabamba, Chuquisaca, Potosí, and Oruro, conscription did not take place until after the revolution's first anniversary in April.Footnote 76

The revolution also coincided with a major change in one of the paper technologies used for conscription.Footnote 77 Most of the men recruited in 1953 had their information recorded on a new preprinted registration table rather than the one that had been in use since at least 1940, when the Ministry of Defense's records begin.Footnote 78 Omitting columns routinely left blank on the previous version, the new form was smaller and did not need to be folded to fit in the bound volume. It did not have columns for most physical descriptors, only retaining a place to record distinguishing marks. More importantly, registration in 1953 seemed to reflect the MNR's professed goal of eliminating Indigenous status. The clerks who filled out the 431 tables listing the information of more than 12,000 men did not assign a racial identity to any of them.Footnote 79

A homicide case from that year, however, shows that the absence of race from the Military Register does not mean that the postrevolutionary military had ceased producing racial data. When Zenón Vedia Chungara accidentally shot fellow conscript Herminio Pérez Paco while patrolling the town of Corque (Oruro) in July 1953, the subsequent military-justice proceeding included a typed copy of Pérez Paco's service record that listed his race as Indigenous. When Pérez Paco presented for service in the city of Oruro in April 1953, the clerk must have filled out a form that solicited information about his birth, family, address, profession, skills, literacy, level of education, languages spoken, and physical description, which included both race and skin color.Footnote 80 With the glaring exception of race, all this information would need to be transferred to either the Military Register or the service sheet sent to the archive.Footnote 81 This internal form thus adds to evidence suggesting the systematic generation and deliberate suppression of racial data during military conscription.Footnote 82 It also shows that the MNR's revolution effected only the reporting of racial information in 1953, not the collection of it.

Despite the absence of race from the 1953 Military Register, it came roaring back into the records when the military held nation-wide registration in February 1954 and continued to appear in the tables filled out in April 1955, April 1956, April 1957, and January 1958. This trend was particularly pronounced in 1954, when the Military Register listed a race for 51 percent of all registrants. Although the percentage of men identified by race was similar to prerevolutionary levels, the places reporting racial data had changed profoundly. Before the revolution, 72 percent of the men identified by race had presented at registration sites in Cochabamba. In the postrevolutionary period, clerks from at least one registration site in each department, except Beni and Pando, drew in a column for race, and only 20 percent of total racial identifications came from Cochabamba.Footnote 83 Far from eliminating racial identification, the military under the MNR widened the practice across the national territory.

The placement of racial data also changed. Whereas race had earlier been squeezed in alongside profession, after 1952, a column was added under “Observations” on the far-right side of the table. This placed race in a more prominent position on the page and subtly implied that the category could stand on its own as compared to the previous position, which had linked race to occupation and literacy. Out of the 632 tables from the post-1952 period that included race, only one reverted to the prerevolutionary placement. In this table from 1955, the clerk entering data from Aquile (Cochabama) wrote a small “M” or “I” next to the profession of the first twenty-nine men who registered for service. He then omitted race all together on the final four pages of registrants. This suggests that, after completing the first page, he realized his mistake or someone corrected him. The remarkable consistency in placement across hundreds of tables filled out by at least forty-six different clerks indicates that they received specific instructions for recording race.Footnote 84

The inclusion of race in the Military Register declined precipitously after 1954, with race recorded for only 28 percent of registrants in 1955, 15 percent in 1956, and then under 7 percent for the next two years before permanently disappearing in 1959.Footnote 85 This drawn-in column provokes additional questions. Why were some clerks instructed to add race while others were not? Did the military stop producing racial data starting in 1959? Or did it just stop telling clerks to add this information to Military Register? Recruitment manuals unfortunately do not answer these questions; they make no mention of what information to collect or how to record it.Footnote 86 The officers involved in registration or the conscripts who served as clerks might be able to clarify—if they remember such a minor detail this many years on. These questions will likely remain unanswered unless internal communications surrounding recruitment are located.

Even without definitive answers to these questions, the existence and substance of racial data reveals much about Bolivia in the 1950s. Its absence from the 1953 Military Register suggests that the military attempted to eliminate reporting on race to reflect the new administration's ideology. Yet the clerks who registered conscripts clearly classified at least some of them by race that year, and the institution restarted and even widened the reporting of race in 1954. This indicates that the collection and reporting of racial data was a conscious decision rather than a habit that had not yet been broken. Racial labels continued to have tremendous power and meaning in the MNR's Bolivia.

Because racial data was only reported at particular recruitment centers, these records cannot be used to determine the breakdown of assigned race among troops in the military or to see how it changed over time.Footnote 87 Instead, each set of registrants must be analyzed on its own terms, taking into account the demographics and social norms of the surrounding area. The handwriting, cross-outs, and blanks in the Military Register also serve as reminders that people filled out the forms and transferred the information. They made mistakes in the process, and they also made individual judgements about each man's race based on ethnoracial markers that varied depending on region and urbanity.

Rather than providing transparent information about the race of the conscripts, each set can be used to understand how the clerks manning that recruitment center might have assigned racial categories to the men who presented for service. For example, the data collected in 1954 on the sixty-one men who registered in the rural province of Inquisivi (La Paz) shows a strong correlation between race and three other factors: literacy, profession, and surname.Footnote 88 Compared to those identified as Mestizo, men identified as Indigenous were far more likely to be listed as illiterate (47 percent versus 19 percent) and as farmworkers (57 percent versus 94 percent).Footnote 89 Clerks did not identify any registrants with Indigenous surname(s) as White but listed twenty-one of them as Mestizo and fourteen as Indigenous.Footnote 90 Although men classified as Indigenous were more likely than those classified as Mestizo or White to be listed as illiterate, as agricultural workers, and as having at least one indigenous surname, the Military Register also shows that Indigenous status was by no means solely determined by these factors. Many of the men whom clerks identified as Indigenous were literate, had two Hispanic surnames, and listed professions such as office worker, tailor, miner, or student.

Racial data from the Military Register is also useful for understanding the effects of assigned race on military service. Except at few provincial registration sites, clerks identified the vast majority of men who presented for service in the 1950s as Mestizo.Footnote 91 This stands in stark contrast to the 1950 census, which classified 63 percent of the population as Indigenous.Footnote 92 The disproportionate predominance of Mestizos shows that men from Indigenous communities were less likely to register for service, that clerks were registering them as Mestizo, or a combination of the two. Either way, the overrepresentation of men classified as Mestizo supports the idea of the military as an assimilatory institution. The Military Register also shows that registrants designated as White were far more likely to be declared unfit for service or only fit for auxiliary service than those listed as Indigenous or Mestizo.Footnote 93 This suggests that bias(es) correlated with racial classification played a role in the medical examination process that exempted some men from military service.

Because it originated from registration sites across the country rather than primarily from Cochabamba, the racial data produced in 1954 offers an opportunity to understand the construction and effects of race. Registrants categorized as White are clearly distinct, listed as having more education and more prestigious professions. More importantly, they were far more likely to be exempted from military service than their nonwhite peers at the same registration site. I found less distinction between those classified as Indigenous versus as Mestizo. Although level of education, literacy, surname, and region correlated strongly with Indigenous status, no one or combination of these factors can be used as a reliable indicator of whether clerks would classify men as Mestizo or as Indigenous. Returning to the example of Herminio Pérez Paco, the clerk listed him as Indigenous despite the fact that he was literate; had completed four years of primary education; had both Hispanic and Aymara surnames; and spoke Spanish in addition to Aymara and Quechua.Footnote 94 The lack of linguistic data in the Military Register prevents wider analysis of this final factor, but limited evidence from other sources suggests that languages spoken was an unreliable indicator of racial classification in the military during the 1950s.Footnote 95

The continued production of racial data during the conscription process points to the enduring power of racial categories and to continuity in the military's bureaucratic practice after the 1952 revolution. Yet the absence of race from the 1953 registration tables and its complete disappearance after 1958 are notable ruptures that likely reflected the MNR's efforts to erase race from the national lexicon and make the population less Indigenous. This ideology may be the reason that most men who registered for military service in this period were classified as Mestizo. The racial data preserved in the Military Register also points to the power of race, particularly whiteness, to shape a man's military service (or lack thereof) in postrevolutionary Bolivia.

Conclusions

The persistent presence of race in military records despite attempts to eliminate it as an acceptable category confirms its importance in Bolivia. Although military service was based on ideals of universality, indigeneity was at the heart of the project. Across party and ideology, conscription policy was always formulated with the explicit goal of incorporating Indigenous people into the nation and reshaping their ways of life. It should thus come as no surprise that the military continued to classify conscripts by race despite anxiety about the practice and the eventual elimination of race from preprinted forms. The evolution of documents related to military service shows the social dimensions and contingency of knowledge production. Many officers directed clerks to draw in a column for race during registration and explicitly marked particular conscripts as Indigenous in correspondence and when testifying. While these officers may have agreed with the principles behind policies that effaced race, they lived in world in which it was practically unthinkable to do so.

Even though people used racial categories as if they were static and easily definable, their content was far more slippery. The ways in which race is present in military records practically screams at researchers to investigate the process that produced these data. Whether and how each man was classified depended on a clerk who drew on his personal experience and societal norms in order to choose whether the man standing in front of him should be counted as Indigenous, Mestizo, or White. The omissions and mistakes apparent in these records should remind researchers of the unreliability of the data that underlies statistics. However, this analysis also points to the benefits of generating racial data. In inscribing a race for the men who registered, the clerks signaled the importance of this category in Bolivian society and provided researchers with a way to document the effects of racialized biases on obligatory military service.