Introduction

Today, it is exceptionally important for a Japanese to enter the West, step on their soil, examine their objects, investigate the inside facts of the human beings, acquire what one should acquire, and imitate what one should imitate. This is why I thought of going abroad to the United States.

Kumagusu’s departure speech.

Wakayama, Kii, Japan.Footnote 1

American scholarship turned out to be terribly inferior to scholarship of my own country.

Kumagusu, writing to his Kii friend, Sugimura Kōtarō

San Francisco, the United StatesFootnote 2

In January 1887, the 20-year-old aspiring naturalist-botanist Minakata Kumagusu (南方熊楠, 1867–1941) arrived at the port of San Francisco, inspired to investigate the knowledge required to become ‘civilized’ (Figure 1).Footnote 3 The Japanese needed to survive the inevitable changes in civilizational progress by learning from the West.Footnote 4 As Kumagusu came face to face with the supposedly civilized nation, however, he quickly realized that the theory of civilization the Japanese Meiji state (1868–1912) had taught him at the University of Tokyo’s Preparatory School was unreasonable. The social Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’, inspired by the study of biological evolution, had no basis in fact. Leaving institutionalized education, he decided to re-examine the nature of social evolution himself.

Figure 1. Portrait photo of Minakata Kumagusu shortly before his departure from Japan to the United States (1886).

Kumagusu turned his mind and heart back to his home region of Kii (紀伊) on Honshū island’s Kii Peninsula in southwest Japan.Footnote 5 His childhood in Kii informed his experience of inhabiting ‘civilizing’ Japan through knowledge that originated from India and China: the complete antithesis of the Meiji government’s West-inspired intellectual agenda. Shingon Buddhism (真言密教), whose main temple was on Mount Kōya overlooking the Kii, left the most significant impact on Kumagusu’s epistemology. Like most Buddhism, the sect’s teaching can be traced back to the Kushan empire of ancient India. The Meiji regime in the meantime persecuted Buddhism from the outset. Furthermore, the encyclopedic work of Wakan Sansai Zue (和漢三才図会/The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan) became another key inspiration for Kumagusu. Chinese historiography and Confucian thought additionally facilitated his reasoning process. All the while, the Meiji government and its associated philosophers, such as Fukuzawa Yukichi (福沢諭吉:1835–1901), regarded knowledge of the Sinosphere embraced in the previous Tokugawa period (1603–1867) as ‘foolish’ and ‘backward’.Footnote 6

The name ‘Kii’ is in fact a Tokugawa naming of Kumagusu’s home region, then governed by the Kii domain (also known as the Kishū domain). Locals have long embraced this place-naming even after it became Wakayama Prefecture under the newly introduced prefectural system in the Meiji era. The knowledge of the immediate past discarded by the government operated as the essential sources of epistemology required in the present. Kumagusu critically examined questions of science, evolutionism, religion, history, and philosophy pertinent to evolutionism and civilization theory, employing knowledge derived from India and China.

What interconnected all of these was what I call ‘queer nature’: the ontological and epistemological basis for truths about what it truly meant to be civilized. Queer nature resembled the microbe slime mould that irresistibly attracted Kumagusu’s attention. Similar to slime mould, Kumagusu’s formation of knowledge based on queer nature evaded the epistemological binaries and hierarchies that shaped modern Western philosophy and science adopted by the Meiji state’s intellectual agenda. It troubled the most fundamental logic of their evolutionary—and civilizational—theories, troubling conceptions such as the West and the rest, civilized and savage, subject and object, and emotion and intelligence. Just like his experience of observing slime mould, ‘knowing’ with queer nature embraced attraction, curiosity, and desire for intimacy.

Kumagusu’s evolutionary theory based on queer nature indicated that societies evolved—and therefore, civilized—through cooperation and affective desire for intimacy with each other beyond normative epistemological divides. Thus, in the light of queer nature, civilizing subjectivities simultaneously embraced collectivity and independence. Becoming ‘civilized’ implied embracing affective desire for each other and inviting borderless collectivity beyond the imposed categories of race and nationalities. Kumagusu indicated that people became ‘civilized’ through independent self-knowledge and moving away from unquestioning reliance on state-provided knowledge. Grappling with intellectual and emotional struggles of his own, he yearned to liberate himself and others from the West-centric and hetero-normative epistemology of social Darwinism.

Kumagusu’s ideal civilization theory was utopian in that it often existed at odds with his own social conditions. For instance, his father’s economic success in Japan’s emerging capitalistic society made his independent intellectual explorations overseas possible. Furthermore, though his remarks suggest he believed in women’s agency, he did not necessarily fight for equal rights for women. Unaccustomed to speaking with women—including his mother or sister since childhood—they remained alien to him until he married in 1906. His theory of civilization based on queer nature surfaced without explicitly addressing how one might come to terms with these contradictions.

In what follows, I will first discuss how queer nature, as I conceptualize the term, impacted on Kumagusu’s knowledge formation, and what queer nature shares with existing queer theory. The main section of the article will demonstrate how queer nature operated in Kumagusu’s reconsideration of social evolution and how Kii’s Indian and Chinese derived concepts helped him formulate his civilization theory. I will elucidate why the state’s vision, inspired by the modern West, turned into a historical ‘retrogression’ and the alternative knowledge of Kii played a crucial role for Kumagusu. I will explain how this epistemological shift brought about Buddhist science, through which queer nature emerged. I will then elaborate on his theories of social evolution and civilization based on the queer nature he embraced.

Historians have rarely decoupled the civilizing process from the making of the modern nation-state inspired by the monolithic seiyō (the West). As a result, the historical meaning of civilization theory—the theory of what it truly meant to be ‘civilized’—and the power of political institutions in shaping its nature remained almost unchallenged. Meiji Japan in the late 1880s epitomizes this understanding, when the government celebrated the promulgation of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan (1889) and the opening of the Imperial Diet (1890). Japanese discourses surrounding civilization theory seemed to have settled when Japan established its governing system as a modern nation-state. Yet, during this very period, Kumagusu judged the state-led, West-inspired civilization theory to be uncivilized.

Kumagusu has fascinated scholars of modern Japan with his myriad interests, pioneering thoughts, and ‘eccentric’ personality. During his lifetime, he made immense contributions to both science and the humanities and forged intellectual bonds with various historical figures as he moved between Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. He published 51 articles in the science journal Nature and approximately 400 English essays and 600 Japanese works in the humanities. In London, he played a key role in facilitating the British Museum’s research on Asia. In Japan, he was one of the first ‘environmental’ activists. His close interlocutors included the Shingon Buddhist monk Toki Hōryū (土宜法竜, 1854–1923), the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen (孫文, 1866–1925), and the ‘founding father’ of Japanese folklore studies Yanagita Kunio (柳田國男, 1875–1962). Even Emperor Hirohito (裕仁天皇, 1901–1989) of Shōwa Japan (1926–1989), also a biologist, requested him to deliver a lecture.

Kumagusu’s multidisciplinary expertise and wide-ranging activities bore no obvious resemblance to other contemporaneous figures, but each of his works and actions resonated with diverse historical actors. The overwhelming majority of historiography has thus focused on each sub-disciplinary aspect of his work in his post-United States period when he became a polymath, prolific author, and influence on various intellectuals.Footnote 7 Initially in the United States, he was a young scholar with no academic publications, and no scholar has interrogated at length whether his ideas for civilization theory during this period, shortly before he became a prolific scholar, differed from those of the Meiji state. Yet, civilization theory acted as his guiding principle for which knowledge mattered and why.

It was in the United States that his questions about civilization and evolution merged with his ambition to become a modern polymath of Japan.Footnote 8 He interacted with fellow Japanese youths who pursued the 1880s movement for democracy, the Jiyūminken Undō (自由民権運動/Freedom and People’s Rights Movement). Many of them fled Japan for San Francisco, seeking to nurture an alternative civilizational agenda that had been censored by the Japanese government.Footnote 9 They kept circulating their ideas in and from the United States through their own newspapers.Footnote 10 Kumagusu even agreed to become a regional correspondent for one of them, Shinnihon (新日本/New Japan).Footnote 11 No detailed record illuminating his intent and the extent of his involvement has survived, though. While locating himself within this social network, he noted without any explanation: ‘I must become a [Conrad] Gessner of Japan.’ The sixteenth-century Swiss naturalist and ‘father of bibliography’ created Bibliotheca universalis (1545–1549), the totalizing record of all known scholarship produced in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Like Gesner, Kumagusu wanted to strengthen his commitment to historical knowledge, but in his case the knowledge derived from the wider Asia that symbolized ‘Japan’ in his intellectual foundation.

Against this background, Kumagusu wrote essays on seemingly discursive topics from religion and science to personal memories of love and torment for his Japanese friends in the United States to read. He kept diaries of his daily activities and personal ambitions. He inscribed his thoughts on what he learned from his independent study in research notebooks. Asserting queer nature as his basis for truths illuminates the ideas for civilization theory that Kumagusu wove into these texts.

Queer nature: Why, what, and how

Queer nature is a queer theory of intellectual history rooted in modern Japan, whose sources of knowledge originally derived from India and China. The dominant Western theory of civilization in this period depended on how one understood the nature of society compared to the nature of the universe discovered by modern science.Footnote 12 Nature provided the empirical foundation upon which society could be built. Therefore, modern intellectuals’ argumentation on what it meant to be civilized depended on knowledge of nature. I arrived at the notion of queer nature through examining primary historical sources on Kumagusu—including his diary, letters, notebooks, essays, drawings, and the specimens he collected. While exploring them, I noticed that his thoughts, emotions, and actions appear to have emerged from a basis for truths that differed radically from the state’s West-inspired civilization theory.

Queer nature resembled Kumagusu’s understanding of slime mould in its ontological and experiential qualities. Ontologically, the elusive biology of slime mould appeared to defy the normative notions of male-female, animal-plant, and life-death binaries and hierarchies. He understood that slime mould possessed qualities of both plants and animals and a transient ability to float between life and death.Footnote 13 They appeared androgynous—their biological sex and attraction undefined by the dichotomy of male-female. Today, they are known to exist in more than 900 biological sexes.Footnote 14 Experientially, the mould never ceased to fascinate and inspire Kumagusu to pursue further intellectual enquiries. His cognitive process as a result blended emotional experience with intellectual reasoning, where the former impacted on the latter and vice versa.

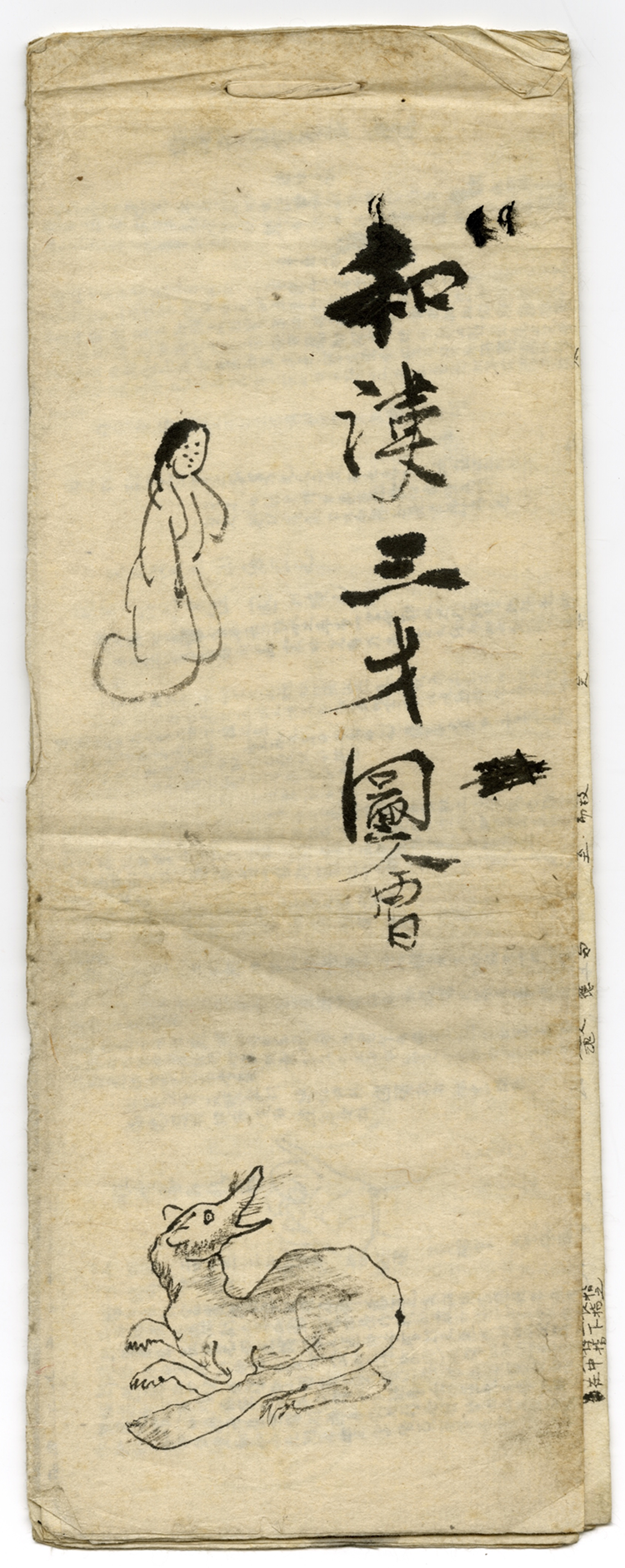

The Japanese terms for slime mould—nenkin (粘菌) or henkeikin (変形菌)—encapsulate what Kumagusu saw through the microscope as he re-examined the evolutionary nature of society.Footnote 15 The former literally translates as ‘sticky-fungi/bacteria’, and the latter translates as ‘transformation-fungi/bacteria’.Footnote 16 The microbes look sticky and are malleable. They continuously change their forms without a normative state and develop acres of mycelium networks on rotting woods and in underground soil. Referring to his drawings of slime mould (Figure 2), Kumagusu described his experience of their fascinatingly ambiguous nature:

[Slime mould] are utterly outrageous. Just like the illustration (1), they swim in water when they are young, turning around and round, and come together before long. They then turn into phlegm-like form, as in (2). Some of them move like amoeba and eat up what they encounter right away. They harden themselves in whatever way they like. From (3) to (7), they transform themselves into various mycological shapes.Footnote 17

Figure 2. Kumagusu’s illustration of microbes in his letter to Hayama Hanjirō.

The characteristics of queer nature that resembled the ‘utterly outrageous’ slime mould appeared natural and therefore truthful in the light of Kii’s scholarship that originates from ancient India and China—as I will elaborate in the rest of this article.

Why, then, ‘queer nature’? Historically the diverse meanings of the term ‘queer’ capture its ontological and experiential qualities. The contemporary usage of the term ‘queer’ as non-binary affirms queer nature’s ontological quality. Experientially, queer nature attracted Kumagusu’s attention and induced greater curiosity within him to enquire further, similar to the ways in which slime mould mesmerized him and facilitated broader intellectual enquiries. Queer nature induced ‘attraction’ and ‘fondness’ towards ‘strange, odd’, and ‘peculiar’ things that appeared ‘startling’ and ‘amusing’, and incited the desire ‘to inquire’ further—all ideas that the term ‘queer’ historically conveyed.Footnote 18

In Japanese, he described the above characteristics of knowing in words such as jōsei (情性/affective human nature), hōyū (朋友/intimate friend), myō (妙/strange), and chin (珍/ curious, rare, and strange). He also compared them to platonic love. For example, he wrote newspapers for his Freedom and People’s Rights Movement friends to read in private, entitling them Chinji Hyōron (珍事評論/The Criticism on Curious Things).Footnote 19 His jōsei (affective human nature) that desired intimacy with his deceased hōyū (intimate friend) manifested as platonic love. Kumagusu’s ideas for a theory of civilization based on queer nature, as a result, queered—or ‘put out of order’ as it once meant—the Meiji state’s social Darwinian civilization theory.Footnote 20

The ‘nature’ in queer nature therefore holds the sense of ‘intrinsic nature’ rather than ‘environmental nature’, the term that emerged during the post-war period.Footnote 21 Similarly, it does not imply the modern Japanese term shizen (自然), which refers to external, ‘objectifiable’ nature, that came into popular use in the 1890s. Kumagusu hardly used the term shizen as a noun in his life even after it settled into everyday Japanese vocabulary. The term appeared in his writing as an adjective, the only form of the term that initially existed in Confucian texts in the previous Tokugawa period.Footnote 22 In fact, he rarely used equivalent Japanese words of the time. For example, the Meiji emperor used the term tenchi (heaven and earth) to signify ‘nature’ in his speech to promulgate the Charter Oath in 1868.Footnote 23 Kumagusu’s own understanding of intrinsic nature runs through his writings without appearing as a fixed term.

Queer nature as a nonessentialist way of knowing shares an affinity with Timothy Morton’s notion of queer ecology.Footnote 24 Emerging in 2010, queer ecology establishes the intimate relationship between ecology and queer theory. It joins together the dual propositions that ‘[e]cology stems from biology, which has nonessentialist aspects’ and ‘[q]ueer theory is a nonessentialist view of gender and sexuality’.Footnote 25 Within this context, Morton notes that Darwin’s evolutionary theory regarded life-forms as mutually determining entities.Footnote 26 Present-day science furthermore clarifies that cellular reproduction happens asexually and that there is no firm boundary between life and nonlife.Footnote 27 Thus, the conception of the environmental ‘“Nature” as an idealized, pristine, and wild’ existence outside the human being does not exist. Morton calls for abandoning terms such as ‘animal’ and adopting ‘something like strange and strangers … [that are] uncanny, familiar and strange simultaneously’.Footnote 28 We human beings are composed of interlinked and interacting cells; we are in symbiosis.Footnote 29 Desire for intimacy with strangers is hence central in queer ecology.Footnote 30

In 2015, the cultural theorist David Griffiths also adopted queer ecology to rethink the epistemology of science and society in the light of microbe lichens.Footnote 31 This fruitful enquiry emerged as a philosophical proposition within the intellectual milieus of Continental philosophy and Western biological science, similarly to Morton.Footnote 32 While queer nature clearly carries a theoretical kinship with queer ecology, its roots reside in the intellectual history of modern Japan whose reliable sources of knowledge originally came from India and China. Queer nature is a way of conceptualising intellectual history that surfaced from a hermeneutical analysis of primary sources produced by Kumagusu within the specific context of modern Japan, situated within particular social and personal conditions that are inseparable from the Asian intellectual lineages.

Within the historiography of queer theory, one could argue that queer nature contributes to what Morton calls ‘dark ecology’. Dark ecology refers to an epistemological transition ‘from an ideological fixation of Nature to a fully queer ecology’.Footnote 33 This epistemological shift correlates with queer theory’s broader concern to overcome the illusion of universal norms. The normative, universalist logics of liberalism and capitalism that assert essentialized differences too often overshadowed historical phenomena that evaded them. Analysing such phenomena with queer theory can reveal narratives of modernity where emotional affiliations that went beyond differences took the central stage. Lauren M. E. Goodlad’s study of E. M. Forster and Jonathan Flatley’s reframing of Andy Warhol, for example, showed this.Footnote 34 An epistemological challenge, however, remains as works of both modern intellectual history and queer theory still largely revolve around Western intellectual lineages and, as a result, marginalize ‘the rest’, albeit unintentionally. This article demonstrates a queer way of navigating the intellectual history of modern Japan, while overcoming this epistemological barrier.

The theory of civilization, retrogressed

Queer nature first emerged when, upon Kumagusu’s arrival to the United States, his perception of the West-inspired civilization theory of the Meiji state slid from the vision of progress to retrogression—in a similar manner to what Sho Konishi termed as ‘the history slide’.Footnote 35 The day-to-day reality of the ‘civilized’ nation welcomed him with normalized racism; encounters that he experienced as ‘uncivilized’. He examined the historical grounds for the West-influenced civilizational narrative in conjunction with studies of science that verified the reasoning. The historical premise turned out to be ones of recent making compared to historical knowledge of his home region Kii that could be traced back to ancient India and China. He realized he could no longer rely on the knowledge provided by the West and the state without questioning it. The dissolution of the foundation behind the theory forced the vision to slide and fall apart. The understanding of history became a matter of social change.

Kumagusu turned to what he recognized as ‘Japanese’ knowledge based in the Kii region of Japan: Shingon Buddhism and Wakan Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan). Having learned them during his formative years in the early Meiji period, they became sources of knowledge that informed him of civilizational changes in the human past. Local knowledge in Kii dated back to the Tokugawa period in Japan, but also further back to ‘premodern’ China and India. It presented a different understanding of the past that justified the experience of the present as well as ideas for the future in the historical narrative of civilizational changes. The present became the moment in which he urgently needed to rectify the narrative of history. What was typically perceived as progressive became backward in his view. Suddenly, history became a matter of social change.

The Meiji government had rapidly adopted the modern knowledge of the ‘civilized’ West while using its normative logic to reframe Japan’s past. By doing so, the state could legitimize its vision of civilizational progress, the foundation of which was grounded in the notion of nature it invented at the beginning of its era. The modern creation of Kokka Shintō (国家神道/the State Shinto) in 1868 was envisioned to replace the ancient belief of Shintō (神道). Instead of worshipping nonhuman nature, as Shintō historically did, Kokka Shintō created a mythology that established the Imperial lineage of Japan as the constitutive, intrinsic nature of the new Japanese nation-state. This innovation emerged while the notion of universal nature in political philosophy became a contested one in the 1860s and 1870s, as Julia Thomas elucidated.Footnote 36 The government, in the meantime, relentlessly disseminated the centralized myth of nature through the Great Promulgation Campaign until 1884.Footnote 37

The ‘modernization’ programme, with a ‘civilized’ modern state as its goal, served to support the ‘divine’ Imperial nature of the Japanese state. Even the Japanese translation of the English term ‘nature’ in the 1880s conveyed the notion of kōkin (洪鈞): the political power of the nation-state as the creator of the universe.Footnote 38 The political ideology of nature sought to encompass all other metaphysical beliefs.Footnote 39 Based on this ideological conception of nature, the government could legitimize scholarly knowledge as they pleased.

Kumagusu had familiarized himself with the state’s concern for and theory of becoming civilized when he attended the Preparatory School for the Imperial University (presently known as the University of Tokyo), the first state-funded university, the aim of which was to nurture future elite bureaucrats. Having moved from the regional city of Wakayama in Kii, he entered the school at the age of 17, enthusiastic about what Tokyo had to offer. He grew aware of the concerns around human civilizational progress in conjunction with the natural history he had so eagerly pursued since his childhood.

The learning environment at the Preparatory School introduced him to the theory of social evolution. The zoologist Edward S. Morse (1838–1925) taught the social Darwinian theory of civilization at the University of Tokyo as one of the oyatoi gaikokujin (御雇外国人/hired foreigners) before Kumagusu’s relocation to the city. Morse became known as the founding father of archaeology in Japan after his excavation of the late Jōmon period (circa 14,000–300 bce) Omori Shell Mound in 1877. Kumagusu bought and read the Japanese translation of Morse’s lecture as soon as he relocated to the city.Footnote 40

His main learning environment quickly moved outside the school. He skipped classes to take trips to archaeological sites where he collected fragments of unearthed human remains and earthenware. He regularly visited the Ueno Library, Ueno Museum, Education Museum, and the Zoo, newly opened as part of the Meiji government’s adaptation of Western public institutions. He thus learned about the early history of human society within the wider context of natural history.

Human civilization had to progress, and the Japanese were no exception, he announced to his friends while holding an axe he had found at an excavation site.Footnote 41 The United States was the ideal setting for him to learn about the essence of the civilizational progress which the Meiji state taught. He dropped out of the Preparatory School, returned to Wakayama, Kii, and convinced his successful merchant father to fund his intellectual endeavour in the United States. His enthusiasm turned to disappointment as he arrived in the ‘civilized’ nation, and his prior understanding of the civilizational progress human society had built up since the Iron Age collapsed.

Kumagusu did not leave a cohesive account on what precisely disillusioned him about the United States and forced him to turn to the historical knowledge of Kii. The marker of so-called ‘civilized society’ that he witnessed is, however, apparent. He related it to his best friend from Kii, Kitahaba Takesaburō (喜多幅武三郎, 1868–1941):

There has been a battle between black people and white people; the American land troops came out. … Approximately a thousand black people, three hundred white people, one hundred militia, and five hundred armed forces.Footnote 42

Developments in Western society, whose scientific knowledge the Meiji government rushed to adopt, had produced alarming racial conflict.

It is also likely that Kumagusu experienced direct racial discrimination in his first seven months in the United States. He stayed in San Francisco and very briefly enrolled at a business school, for unknown reasons.Footnote 43 The port city and Oakland across the bay harboured a community of young Japanese activists involved in the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement.Footnote 44 The state of California, however, had asserted discriminatory laws against ‘Mongoloids’, a category which encompassed both Chinese and Japanese.Footnote 45 Schools forced segregation upon them, while the legislature removed it for black people in 1880.Footnote 46

With a sense of conviction, Kumagusu wrote to one of his lovers Sugimura Kōtarō (杉村廣太郎, 1872–1945), the future prominent journalist for the left wing Asahi newspaper, with whom he became intimate while in Kii:Footnote 47 ‘I found out the United States is a new country that does not have everything. American scholarship turned out to be terribly inferior to scholarship in my own country.’Footnote 48 The kinds of American scholarship he rigorously studied were modern scientific and evolutionary theories. These, in turn, were the subjects that inspired the civilization theory current at that time. He jotted down in his notebook that modern Western civilization manifested ‘not progress, but retrogress’.Footnote 49

What informed his ‘history’ of civilizational narrative was the Indian- and Chinese-derived knowledge and customs that had continued to shape and celebrate local people’s lived experience in Kii since the Tokugawa period. Kumagusu absorbed them before he even began his formal education. He then compared this knowledge of the immediate past with the state-filtered knowledge of modern natural history and science from the ‘civilized’ West that he was introduced to in junior high school.Footnote 50 These historical works informed his scientific and philosophical questions of truths about nature in the present moment.

Similar to scientific enquiry, Shingon Buddhism illuminated the truths of the universe. ‘Shingon’ literally means ‘words of truths’—the secret truths of Dainichi Nyorai (大日如来/Mahāvairocana), the primordial Buddha that symbolizes the true state of the universe.Footnote 51 The sect originates in the learned Buddhist priest Ryūmyō (龍猛, or Nāgārjuna: circa 150–250 ce) who formalized esoteric Buddhism’s foundational scriptures in the Kushan empire of ancient India.Footnote 52 Following the spread of his teaching, the Japanese monk Kūkai (774–835 ce) brought back an immense volume of its scriptures, ritual implements, and mandala to Japan from Tang dynasty China (618–906 ce) in the early Heian period (794–1185).Footnote 53 He established Shingon Buddhism in Mount Kōya in the Kii region with the support of Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇, 786–842 ce) in 806.Footnote 54

The Tokugawa encyclopedic work of Wakan Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan) also elucidated worldly knowledge within its cosmology. Sansai, or ‘the Three Knowledges’, in the title referred to knowledge of ten (天/the heaven), chi (地/the land), and hito (人/people). The ‘heaven’ section encompassed conceptions of various Buddhist gods, seasons, weather, and an almanac.Footnote 55 The ‘land’ section covered the geographies of Japan and China, mountains, rivers, minerals, and plants.Footnote 56 The ‘people’ segment included explanations on the order of human relationships and ‘religious’ beliefs as well as on animals.Footnote 57 The Chinese medicine physician Terashima Ryōan (寺島良安, 1650–unknown) of Tokugawa Japan compiled its 105 volumes, using Chinese and Japanese classical literature as the major source of knowledge and citing any cultural and historical changes of understanding.Footnote 58 Ryōan modelled them on the Chinese work of the Ming dynasty period (1530–1615), Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge) by the scholar Wáng Qí (王圻, 1530–1615), among others.Footnote 59

It was against this intellectual background that Kumagusu began to interrogate the nature of social evolution in the United States. He was a modern ‘Kiikoku-jin’ (紀伊国人)—‘the citizen of Kii’.Footnote 60 It was ‘Kiikoku’ knowledge (紀伊国/the nation of Kii) against which American scholarship paled in comparison. He grumbled to Sugimura: ‘Looking back at the current situation in Japan, the society is horribly confused. … Selling [social and governmental] ranks while engaging with intellectual research is equivalent to Kan・Rei (桓・霊).’Footnote 61 Here he was referring to a historical incident of the late second-century Japan when frequent war under the reigns of the emperors of Kan and Rei led to the near-disintegration of the whole country. He asserted that the Japanese had to learn about their own ‘country’ before they ‘adore the West’, mimicking it in order to claim that they, too, are ‘civilized’.Footnote 62

Kumagusu was certainly ‘Japanese’ in that he cared enough to be troubled by the civilizational vision of the country,Footnote 63 but the country to which he maintained his patriotism was not the modern nation-state ‘Japan’ that issued him with a conscription order.Footnote 64 For him, ‘Japan’ comprised historical knowledge entangled in over 250 years of international trade and cultural exchanges highly controlled by the Tokugawa Shogunate. Such knowledge was variously rooted in localities previously governed by approximately 300 clans under the Tokugawa Shogunate. In the current state of society, he asserted, ‘[t]here is no point for me to be a citizen of Japan’.Footnote 65 He continued, writing to Sugimura: ‘But, there you exist: my beautiful and deeply affectionate bosom friend. I long for my dear hometown.’Footnote 66 He had to rectify history to delineate a ‘different kind of civilization’.Footnote 67

History, rectified

Kumagusu rectified history by connecting his lived experience of adolescence and Indian- and Chinese-derived knowledge pertaining to the district of Kii with contemporary concern for becoming civilized. Two distinct features marked his adolescence. First were his intimate—and often sexual—friendships with other male youths and, second, his attraction towards curious creatures like microbes. Shingon Buddhism and Wakan Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan), both of which he had known since childhood, most naturally bring these features together. Neither of them aligned with the hierarchical and dichotomized ontology of Western science and philosophy adopted by the Meiji regime. This knowledge recognized non-binary sex and attraction as ontologically natural. Through them, his yearning for intimacy with no longer physically obtainable lovers merged with his thirst for greater intellectual enquiry into microbiology.

From its beginnings, the Meiji government persecuted Buddhism through the nationwide policy of haibutsu kishaku (廃仏棄釈).Footnote 68 It almost entirely destroyed Buddhist temples that merged with Shintō (神仏習合/shinbutsu shūgō) in the Kumano mountains of the Kii region.Footnote 69 Kumagusu’s parents, however, continued to believe in Shingon Buddhism, the relatively unaffected head temple of which was located on Mount Kōya and overlooked the city of Wakayama where he was born.Footnote 70 This background familiarized him with the cultures of Shingon before 1889, the year when the imperial sovereign state allowed other metaphysical beliefs to operate under its power.Footnote 71

Shingon Buddhism embraced fluid sexuality among men and boys.Footnote 72 Mount Kōya was known for nanshoku (男色/‘male-colour’), that is, romantic and sexual relationships between them.Footnote 73 As a teenager, Kumagusu participated in this culture during his visit to Mount Kōya with his family.Footnote 74 In the Tokugawa period, monastic culture was in no way considered unnatural. It only became ‘uncivilized’ behaviour—slowly yet surely—under the Meiji state’s particular civilizational agenda.Footnote 75 Termed ‘homosexuality’ in English, it was certainly illegal according to the United States’ Judeo-Christian derived culture. Nevertheless, nanshoku or similar ‘intimate friendships’ among male youths remained natural for at least the duration of Kumagusu’s adolescence in Kii.Footnote 76 These relationships inspired emotional bonds and compassion as well as intellectual rigour and curiosity that helped them to navigate the civilizing process of the new era.

Wakan Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan) also helped bridge non-binary ontology both in terms of Kumagusu’s desire for his lovers and his drive towards intellectual investigation in natural science. The Tokugawa encyclopedic work continued to circulate in the Kii region’s local shops and among residents even after the fall of the Shogunate.Footnote 77 It shaped Kumagusu’s foundational knowledge from early childhood and throughout the rest of his life. In his leisure time during junior high school, Kumagusu hand-copied every single volume of this work (Figure 3). This publication classified human sexuality in non-binary categories.Footnote 78

Figure 3. Honzōgaku publication Wakan Sansai Zue, hand copied by Kumagusu, circa 1881.

The study was at the heart of Kumagusu’s intellectual bonding with his male lovers during his adolescence. In the United States, it carried, for him, the existential memory of Hayama Shigetarō (羽山繁太郎, 1868–1888), with whom he shared an intense intimacy and longed to be reunited. It moreover merged with his desire for greater intellectual enquiry. This is illuminated by a short reflective piece of writing Kumagusu inscribed on the latest copy of Wakan Sansai Zue he received from his brother in Wakayama. After narrating his relationship to the publication since childhood, he recollected how he and Shigetarō discussed the significance of the scholarship.Footnote 79 Through this work, together they cultivated their intellectual curiosity while both suffering from ill health. Shigetarō however passed away as a result of his illness after Kumagusu left for the United States. He thus concluded:

This book both tortures and delights me. When I think of print writing, this book again induces me to tears. Through this book, I cure my incurable illness and receive immense wisdom and knowledge. With this book, in this moment, I am able to retain traces of the times with my most intimate friend when my mind and heart filled with pleasure.Footnote 80

His Kii-derived historical knowledge, then, became entangled with his conception of natural science as he examined ‘myō’ (strange) and ‘chin’ (curious, rare, and strange) microbes. He equipped himself with a microscope, illustrated copies of the study, and matchboxes, which he used as specimen containers. With these tools, he carefully examined microbes in his cluttered rented room and created specimen books of his own. He eagerly corresponded with another independent microbiologist, William Wirt Calkins (1842–1914), to discuss and exchange findings.Footnote 81 He even found new species of lichens that made appearances in the journal Science, though Calkins announced Kumagusu’s findings as his own and made no acknowledgement of his young Japanese friend.Footnote 82 Seemingly not discouraged by such incidents, Kumagusu tended to his research.Footnote 83 His motivation as a naturalist seemed to have little to do with fame or success.

The entanglement between his knowledge and activities is shown in how he described himself:

A big scholar, specializing in botano-physiology, botano-morphology, botano-taxonomy, and ætiology, and the mastery of Buddhistic, Confucian, and historic-Japanese literatures.Footnote 84

His specialties as a scholar were, furthermore, informed by his personal identification as: ‘Formerly, a “sanga” in Jizōin, Kōya; Presently … The “king of love”’.Footnote 85

In this imagined persona, Kumagusu was one of the monks (sanga) who lived under Buddhist precepts at the Shingon temple on Mount Kōya. He then became the ruler of an independent state that governed love. This Buddhist ‘king of love’ was a natural scientist fascinated by the ‘utterly outrageous’ physiology, morphology, taxonomy, and ætiology of microbes.

Buddhist science

The study of nature was never natural. Inescapably, human culture was helping to shape the epistemology of natural and social science. So-called ‘objective’ understandings of universal and societal nature were no exception.Footnote 86 Recognizing the cultural nature of the science behind theories of evolution and civilization, Kumagusu configured Buddhist science.

As Western-inspired civilization theory began to disillusion Kumagusu, he criticized ‘the scientists of the modernist school’ who effectively validated the civilizing process, influenced by the social Darwinian view of ‘progress’.Footnote 87 It manifested what he would regard as ‘retrogress’.Footnote 88 The presence of social, racial, and international hierarchies, and also the state’s control over people’s freedom, all evidenced civilizational retrogression. The epistemology of daijō (大乗/mahāyāna) Buddhism to which Shingon belonged asserted the equality of all humans.Footnote 89 Kumagusu argued that,

There is nothing between heaven and earth that desires restraints; nothing in east, west, north, south, the heaven, and the earth that favors inequality. … Freedom and equality are the greatest felicities in the world.Footnote 90

The naturalist Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory and philosopher Herbert Spencer’s theory of social evolution emerged through a dichotomized and hierarchical epistemology of modern Western science.Footnote 91 Kumagusu knew that modern Western science emerged alongside affirming the Christian epistemology that asserted the domination of humans over nonhuman nature.Footnote 92 This scientific culture justified social Darwinism where the normative idea of ‘human’ was represented by a white male heterosexual elite; everyone else was closer to ‘primitive’ nature. Scholars at the Imperial University, in the meantime, erased the Christian cultural aspects from the theory while preserving the Spencerian epistemology. In doing so, then-president of the university Katō Hiroyuki (加藤弘之, 1836–1916) translated Darwin’s theory of evolution into a Spencerian social theory of shinkaron (進化論/The Progress Theory), suited to the political ideology of Kokka Shintō (State Shinto) that held the Imperial lineage sacred.Footnote 93

It was in the context of these cultural dynamics that Kumagusu let Buddhism influence his science. His practice of science thus emerged from an epistemology suffused with Daijō Buddhism (mahāyāna), to which the Shingon sect belonged. Daijō teaches that any phenomena, the subject of epistemic recognition, emerges from each individual’s kokoro (心/mind-heart).Footnote 94 In other words, the Cartesian hierarchical assertion of mind-over-matter and the ‘scientific’ dichotomies of object-subject and intelligence-emotion simply did not exist in this Buddhist science.

Within this epistemology, Kumagusu classified reality into bukkai (物界) and shinkai (心界).Footnote 95 Bukkai signified the world of matter, whereas shinkai referred to the world of kokoro (心/mind-heart). The notion of kokoro (心) denotes an organ that takes charge of thoughts (the mind) as well as emotion (the heart). In shinkai (the world of mind-heart), therefore, intellectual recognition is intimately intertwined with emotional experience. Nature, in turn, emerged at the intersection of the world of matter and the world of mind-heart. The nature that surfaced in this Buddhist science was queer nature, encapsulating Kumagusu’s desire for intimacy beyond the dichotomized and hierarchical epistemological divides.

A semi-fictional autobiographical gesaku (戯作) he wrote in 1889 evidences the emergence of queer nature in his Buddhist science.Footnote 96 Entitled A Writing for Ryūseiho (竜聖法に与うる書), he addressed the piece to his United States-based Japanese student-friend Watanabe Ryūsei (渡辺龍聖):Footnote 97

I, Jintaku, am a man of Hidaka district in the nation of Kii… One day, I read Kūkai (空海)’s Sangō Shiiki (三教指帰). Upon closing the book, I realized this is the direction to where my life is headed. I studied very hard, trying every possible means. Now I am in the US. … My most earnest desire is to rescue everyone. The hardship of life can rescue society. … The virtue of Buddha never changes, Buddhist scriptures are accurate, Buddhist precepts are orderly, and the sutra is rational. … Spencer facilitates Christians’ partial peace and ignorance. Japanese Buddhism these days has particularly deteriorated; Christianity has greatly confused and disturbed Buddhist truth. … I therefore cross marshes and walk into forests to thoroughly investigate the nature of matter during the day; I read the sutra and reflect on the image to enquire into the dynamic of matter and mind-heart at night. … I named myself Minakata Kumagusu in this human world.Footnote 98

Here, he portrayed himself as a fictional Buddhist monk Jintaku (腎沢). Kumagusu merged his persona as the monk with his closest lover Shigetarō, who occupied his mind-heart, by noting that the monk himself belonged to Shigetarō’s hometown of Hidaka. This monk became aware of his life’s purpose upon reading the autobiographical novella text of Kūkai, the founder of Shingon Buddhism. Jintaku realized that he must rescue society from intellectual chaos as Minakata Kumagusu in the human world, just like Kūkai. Society had fallen into epistemic turmoil; people could not discern what it actually meant to become civilized in the light of Buddhist truths. Spencer’s social Darwinism normalized Christian-derived epistemology. Japanese Buddhism lost its own epistemology to this social Darwinian norm. Kumagusu examined nature, the empirical foundation of civilization theory, in microbes he collected in fields and forests. He did so within the ‘mindframe’ of Buddhist epistemology, in which matter and mind-heart are symbiotically intertwined.

Kumagusu was certainly not alone in combining Buddhism with science in the late 1880s to the early 1890s. Buddhism was on the brink of its reinvention to become compatible with the ‘scientific objectification’ of nature in 1880s Japan, as Godart has shown.Footnote 99 The combined forces of state persecution and rising Western science were threatening Buddhism. Christianity was experiencing rapidly increasing church membership.Footnote 100 Competing with one another, Buddhism and Christianity strived to argue for their compatibility with ‘civilized’ Western science.Footnote 101 Inoue Enryō (井上円了, 1858–1919) was the most prominent figure to advocate for the integration of Buddhism with Western science and philosophy. His influential 1887 publication Bukkyō katsuron joron (仏教活論序論/Introduction to the Vital Theory of Buddhism) argued that Buddhism was compatible with the Spencerian theory of social evolution.Footnote 102

In the United States, however, Kumagusu was away from the movement. His focus on Buddhism rested on the historical discussion of religions in the Anglophone world and their relationship to methods for finding the ‘truth’.Footnote 103 He showed no interest in Buddhism’s social and political status in Japan. Moreover, while learning from Spencer, he contemplated his own theory of evolution, unlike Enryō. As a result, he also argued against Spencer—again, unlike Enryō.Footnote 104 He did so before Enryō and other Buddhist thinkers, such as Kiyozawa Manshi (清沢満, 1863–1903) and Miyake Setsurei (三宅雪嶺, 1860–1945), began to question the ideas of evolution led by the Spencerian ideas of ‘progress’.Footnote 105

The theory of social evolution, based on queer nature

For Kumagusu, nature emerged as queer. The microbes he observed through the lens of Buddhist science appeared to reflect the state of his mind-heart, filled with what he referred to as jōsei (情性, affective human nature).Footnote 106 His yearning for intimacy with his physically unobtainable male lovers merged with his curiosity surrounding the strange, ‘outrageous’ microbes and desire for greater intellectual enquiry. As I explained earlier, his favourite microbe slime mould ontologically eluded the normative conceptions of male-female, animal-plant, and life-death binaries and hierarchies. Knowing with and through slime mould blended emotional experience with intellectual recognition. In other words, both the microbes and his affective human nature ontologically and experientially transcended the epistemological dichotomies and hierarchies that ‘the scientists of the modernist school’ and social Darwinists regarded as fundamental in evolution. As a result, his evolutionary theory based on queer nature suggested that societies evolved through cooperation and affective desire for intimacy with each other beyond normative epistemological divides.

Such ideas behind Kumagusu’s theory of social evolution emerged inseparably from his knowledge of Chinese historiography (for example, jōsei as affective human nature). He saw that the ways in which certain cultures and nations wrote history determined which characteristics they considered natural social—social evolution—within human civilization. When Kumagusu became dismayed by the ‘uncivilized’ state of the United States, he consulted the work of Sīmǎ Qiān (司馬遷, circa 145–86 bce), known as the ‘founding father’ of history writing in Asia.Footnote 107 Sīmǎ Qiān developed Kidentai (紀伝体), a synthetic method of producing records of the changing world—that is, civilization—in early Han dynasty China (206 bce–220 ce). Scholars of the Tokugawa Shogunate families then adopted this system to write the history of Japan.Footnote 108

‘All I can do for now is simply follow the example of jitsugyō (実業/business), the basis of civilization,’ Kumagusu declared to Sugimura.Footnote 109 He elaborated on this seemingly capitalist idea: ‘What is jitsugyō (business)? It is a way to create tomi (富/wealth).’ Footnote 110 This was shortly before the notion of ‘business’ came to be used increasingly in the history of capitalism in Japan.Footnote 111 ‘Wealth’, however, had nothing to do with financial or territorial gain, with which the state was concerned amid rising international capitalism that originated from the European Enlightenment. He explicated:

According to Sīmǎ Qiān, tomi (wealth) is a person’s jōsei (affective human nature), and it is not something that one learns but desires together with others. If tomi (wealth) was affective human nature, jitsugyō (business) is a business that all nations and each race should learn together while helping each other.Footnote 112

One had to acknowledge affective human nature as civilizational wealth in order to civilize society and oneself. One could recognize affective human nature through interpersonal—and potentially interspecies—relationships. The idea implied an innate collective desire for each other. Yet, such a wealth seemed to be deficient in human society of the day. Hence, despite Sīmǎ Qiān’s argument that it was not about learning, Kumagusu asserted that all nations and races had to learn the method of producing this wealth.

Similar ideas appeared as a theory of social evolution in Kumagusu’s short essay ‘Chinron: Myō na Shinkaron (珍論: 妙な進化論/A Curious Theory: The Strange Progress Theory)’.Footnote 113 The piece was part of Chinji Hyōron (珍事評論/The Criticism on Curious Things), a hand-written newspaper he wrote and circulated in confidence among his Japanese friends in the United States. ‘The curious theory’ discussed a series of modern scientific discoveries that explained the nature of the universe.Footnote 114 He contended, in the text for ‘The Principle of Venereal Passion (色欲原則)’, a theory that should be, he explained, seen as the successor of ‘the father of shinkasetsu (進化説/the progress theory) Spencer’.Footnote 115 The theory, according to him, revealed the desire for intimacy intrinsic to affective human nature.Footnote 116

No further details of the theory exist. After the brief comments in the essay, Kumagusu resentfully remarked: ‘sadly, nobody yet writes about the progress of venereal passion … what is to blame is the current condition of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 117 However, it is possible to sketch an outline of the theory by cross-examining who and what evoked Kumagusu’s affective desire for intimacy: memories of his male lovers and cryptogams, a type of organism associated with a microbe Kumagusu was particularly fond of. They resonated with one another, marking nature as queer, in his Buddhist science.

The primary subject that evoked Kumagusu’s affective desire for intimacy in the midst of his research in microbiology was Shigetarō, who he had left behind in Kii and had recently died.Footnote 118 He expressed his torment:

I have been thinking of him quietly for so long. … If I am to die with the illness in the end, I would rather return home and sleep together with him in the same hole.Footnote 119

The longing for his dead lover led him to experience the present as a simultaneous expression of life and death. He barely ate or slept; when he did sleep, he dreamt about Shigetarō.Footnote 120 The affective desire for intimacy extended to Shigetarō’s brother Hanjirō (蕃次郎: 1871–1896) who was still alive and with whom he also had a romance before he left Japan.Footnote 121 He maintained the will to live only through his desire for entities that were no longer physically obtainable, seeing them instead in his dreams.

For Kumagusu, cryptogams symbolized the symbiosis of intellect and emotion. These were plant-like organisms without visible sexual organs, like flowers or seeds,Footnote 122 and included slime mould, fungi, seaweed, mosses, liverworts, and lichens. The name ‘cryptogam’, moreover, derived from the Greek words kryptos (‘hidden’), and gameein (‘to marry’) to imply ‘hidden reproduction’.Footnote 123 While their sexual organs were invisible, it seemed to him that some of the slime mould’s visual appearances curiously resembled human sexual organs (Figure 4).Footnote 124

Figure 4. Kumagusu’s drawings of cryptogams and slime moulds in his letter to Hayama Hanjirō.

‘They are so desirable,’ Kumagusu told Hanjirō.Footnote 125 His research into these microbes became inseparable from his intimate dialogues with his lover. He continued: ‘The other day I wrote on and on asking you to kindly collect algae and lichens [in the Kii region]. What I would love for you to also look for are fungi.’Footnote 126 As he looked through the microscope to examine the microbes he had gathered in a land far away from Kii, his affective human nature appeared to be in symbiosis with the curious microcosmos that irresistibly attracted his attention.

As Kumagusu sketched what these microbes looked like, he asserted that slime mould, the Mycetozoa group in particular, should be regarded as animals instead of being categorized in the taxonomical classification of plants. In other words, he desired to place them in a class closer to humanity.Footnote 127 In his thinking, the biological relation of Mycetozoa to humankind was evident. He agreed with British biologist Edwin Ray Lankester (1847–1929) that Mycetozoa was the oldest form of life on the planet.Footnote 128 In his book Degeneration: A Chapter in Darwinism, Lankester argued that evolution does not necessarily always result in ‘improvement’.Footnote 129 As such, even though the emergence of humankind occurred much later than the rise of Mycetozoa, it could not be logically argued that humankind was a superior life form.

Mycetozoa hence manifested two of Kumagusu’s pivotal observations of evolutionary nature. The microbe first demonstrated that social evolution can ‘retrogress’, as he witnessed in American society. Second, it proved that neither the microbes’ seeming asexuality nor their bodies’ sexual ambiguity hindered evolution. There had to be reasons why such organisms still existed.Footnote 130

Kumagusu further developed these ideas as he set off to travel to Cuba to search for rare cryptogams.Footnote 131 Here, by comparing cross-mixing of the human race to microbial osmosis, he imagined ‘a different kind of civilization’.Footnote 132 Although he did not elaborate on this remark, it is clear that intimate interracial relationships appeared natural in the light of the queer nature he observed in microbes. Japanese intellectual elites working with the Meiji state in the meantime considered the mixing of races a highly sensitive issue.Footnote 133 Inoue, for example, strongly argued against the mixing of seiyō-jin (西洋人/the Westerners) with Japanese.Footnote 134 He feared, naturally, that they might take over the ‘weak and inferior civilization’ of Japan based on the innate characteristics of social Darwinism.Footnote 135 Spencer, who occasionally advised the Meiji state, also vehemently opposed ‘the intermarriage of foreigners and Japanese’, arguing that ‘the result is inevitably a bad one’.Footnote 136 Such concerns seemed irrelevant for Kumagusu in light of queer nature.

The theory of civilization, based on queer nature

How Kumagusu imagined manifesting these ideas of social evolution as a theory for civil society remains unknown. He said he wrote many ‘secret theories’ against Spencer but could not publish them ‘due to the confusion of the entire world’.Footnote 137 It is possible, however, to uncover their outlines by analysing how he situated his affective desire for intimacy within other recurring topics of interest. These included a thirst for knowledge and independence, and a concern for morality and collectivity.

These preoccupations were also key issues in the Meiji regime’s theorization and dissemination of its ideas for civilizational progress.Footnote 138 For example, the state deemed the adaptation of Western knowledge to be a central requirement for the nation to civilize and remain independent.Footnote 139 The state centralized moral codes to suppress internal uprisings and maintain national collectivity amid the effort to ‘civilize’. The fundamental disagreement between Kumagusu and the state on these matters arose, however, from their contrasting views of nature, which served as their foundation of truths.

Based on queer nature, Kumagusu’s theory of civilization called for civilizing subjectivities to become simultaneously independent and collective.Footnote 140 It asserted that knowledge of one’s own nature was a prerequisite for individuals who are in the process of civilizing; acquired self-knowledge facilitated individuals’ independence. For his own part, Kumagusu’s self-knowledge recognized his affective desire for intimacy with others. This self-knowledge simultaneously implied collectivity in its essence. Civilizing subjectivities could inhabit independence and collectivity at the same time because, in his understanding, anyone could possess moral agency.

Kumagusu’s thoughts behind these notions surfaced when he responded to fellow Japanese friends in the United States who had immersed themselves in modern Western political ideologies.Footnote 141 From ‘anarchism’ to ‘socialism’, the ideologies they discussed could be identified with the term ‘shugi’ (主義/ism) in modern Japanese.Footnote 142 He criticized what appeared to him to be the temporal privileging of modern thoughts in history: ‘Well well, though there are so many kinds of ism, most of them are utterly one-sided.’Footnote 143 The ideologies that argued for the freedom and equality of people were not at all new, and Kumagusu argued that they were continuations of ‘pre-modern’ ideas that had existed for thousands of years in Buddhist thought.Footnote 144

In accordance with the Buddhist intellectual lineage, Kumagusu believed that one ought to find one’s own ism that exists in multiplicity. Koko ga Kugai no Mannaka Kaina (こゝが苦界のまんなかかいな/Is This the Centre of the Tough World?), the opening story of The Criticism on Curious Things, elaborates on how to do so. In this story, Kumagusu and his friends live in a world where brutally harsh things can happen—like the loss of loved ones; the Buddhist notion of kugai (苦界) in the title denotes such a human world. But people could become like rakan (羅漢/literally, ‘worthy one’), the Buddhist epithet for those who gained wisdom close to the Buddha’s. Rakan meditated on the nature of the world to help overcome spiritual torment, according to Kumagusu. If people were to follow this path, they would then arrive at their own ism that exists in hundreds of heterogeneous forms. Such diverse isms resembled the 33,333 faces of the Buddha which, upon close inspection, illuminate the face of the person they yearned to meet. He thus wrote:

The world is fast changing, but what does not change is the nature of human beings. Ripped clothes and broken shoes heimin (平民/the common people) -ism … eight-tongued repeat-ism, reliable and hindering critic-ism … whatever is good-ism … so many men, so many minds. … five-hundred isms at a gathering of rakan … thirty-three-thousands-three-hundreds-thirty-three ism of the Buddha at the temple of the Sanjūsangendō (三十三間堂) … One ism exists for a person’s own way, one’s own way also exists for one ism. Oh, is this the centre of a tough world.Footnote 145

Sanjūsangendō was a Buddhist temple in Kyoto built by the renowned warlord Taira no Kiyomori (平清盛, 1118–1181) for Emperor Goshirakawa (後白河天皇, 1127–1192) in 1164. A historical anecdote of the temple famously suggested that, if observing carefully, one would find the face of the person they long to meet among the temple’s 1,001 golden statues of the Goddess of Compassion Kannon in her thousand-armed incarnation. Those who Kumagusu was dying to see were, of course, the Hayama brothers with whom he had nurtured intimate relationships in his adolescence.

Writing to Sugimura, Kumagusu declared that the ism he ‘could not possibly abandon’ was ‘the rising affect (情/jō) and desire (慾/yoku) for loved ones’.Footnote 146 An interpersonal relationship he described as hōyū (朋友/intimate friends) activated this affect and desire for collectivity.Footnote 147 ‘Intimate friend’ was also how Hayama Shigetarō had described his relationship to Kumagusu in English before their separation.Footnote 148 Kumagusu, in the meantime, described his emotion towards his hōyū (the intimate friend) Shigetarō as ‘platonic love’.Footnote 149 The notion of love advocated by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato was asserted to be androgynous.Footnote 150 It resonated with Kumagusu’s sustained affect and desire for physically unobtainable intimate friends.

Kumagusu explained that hōyū was one of the Five Ethics (gorin/五倫) in Confucian thought.Footnote 151 He argued: ‘Hōyū … ought to happen in women … and in boys, too.’Footnote 152 Women and children—whom the state perceived as inferior to men and adults—also possessed the agency necessary for moral conduct.Footnote 153 It was thus possible for any civilizing subjectivity to simultaneously inhabit independence and collectivity.

Conclusion

Nature, the basis for truths, emerged as queer in Kumagusu’s re-evaluation of civilization theory in the United States between 1887–1892. Queer nature resembled the ontological and experiential qualities of microbe slime mould in ways that challenged the epistemological binaries and hierarchies of modern Western philosophy and science. Slime mould possessed characteristics of both animals and plants, seemed to exist without a clear boundary between life and death, and appeared androgynous. The microbe attracted his attention and induced greater curiosity and desire for intimacy. As a result, knowing through queer nature defied the separation between intellect and emotion. The truthful meaning of civilization theory, then, implied that societies became civilized through cooperation and affective desire for intimacy with each other beyond the normative epistemological divides.

Theoretically, the article challenged the epistemological barrier of existing queer theory that revolved around the intellectual lineages of continental philosophy and Western science. Queer nature, as I argue, appeared natural not only in the light of microbes, but also in ‘Japanese’ knowledge of Kumagusu’s home region Kii whose localized intellectual lineage derived from ancient India and China. Shingon Buddhism and the Tokugawa-period encyclopedic knowledge of the world of Wakan Sansai Zue (The Illustrated Three Knowledge of Sino-Japan) affirmed the intrinsic characteristics of queer nature. Chinese historiography and Confucianism facilitated his reasoning process.

The article therefore challenged the narrative of ‘modernization through Westernization’ that informed the predominant historiography of modern Japan. Knowing through queer nature evidenced that neither ancient nor Asian knowledge equated with pre-modern primitivity. Instead, they existed as the essential sources of knowledge that opened up a novel way of understanding the present moment in ‘civilizing’ society. Kumagusu turned to them as he questioned the singular authority of Western philosophy and science that validated civilization theory. The historical foundation of social Darwinism crumbled and fell apart when he faced ‘uncivilized’ racism in the United States. The West-led civilization theory that had appeared as ‘progress’ suddenly slid down to a state of retrogression.

Within the above context, I revealed a new history of Buddhism and science in modern Japan, showing a case study where Buddhism did not resort to the social Darwinian paradigm of civilizational progress in the 1880s and 1890s. Kumagusu’s Buddhist science reinvented the ontological and epistemological foundations upon which modern science developed. His knowledge of science expanded while he interrogated a scientific enquiry of nature through Buddhist ontology and epistemology—consequentially leading him to practise Buddhist science. Buddhist thoughts asserted intrinsic freedom and equality of all beings and defied conceptual dichotomies and hierarchies of human domination over the earth and mind over matter. Discerning evolutionary nature in microbes, queer nature appeared as the symbiosis of his mind-heart and microbial biology.

Furthermore, the article advanced the existing historiography of evolutionary theory in the modern Japanese history of science that, again, revolved around Japanese thinkers’ adaptation of Western epistemology. I illuminated the ways in which Kumagusu reflected on the evolutionary nature of society based on queer nature he discerned within Buddhist science. His theory implied that societies evolved through cooperation and affective desire for intimacy with each other beyond normative epistemological divides. His knowledge of Ming dynasty China—instead of the European Enlightenment—provided him with insight. Sīmǎ Qiān, the founding father of history writing in Asia, asserted that the wealth of civilization was jōsei (affective human nature). Kumagusu recognized jōsei (affective human nature), desiring an intimacy with no longer physically obtainable lovers in Japan. As he observed microbes, he reflected on their wondrous non-binary biology that rarely failed to capture his intellectual imagination.

I then delineated Kumagusu’s civilization theory for the first time, building on the above findings. I showed how his ideas for the theory emerged while contemplating the same shared concerns as the Meiji government—that is, a thirst for knowledge and independence, and a concern for morality and collectivity. Kumagusu and the Meiji regime, however, developed their arguments surrounding these key notions based on their contrasting nature which operated as their basis for truths about what it meant to civilize.

Thus, the illuminated history moves the understanding of nature as the basis for truths away from a singular cause towards an entanglement of multiple agencies in modern Japanese history. It destabilizes conventional dynamics of power and knowledge production which determine the historical narrative of civilizational discourse. The dominant account of ‘civilizational progress’ that placed the Meiji state at its centre typically followed the Foucauldian perspective where the regime of power, not knowledge in and of itself, produced the basis for truths.Footnote 154 In Kumagusu’s thought, the regime of power played a role only to the extent that it induced greater individual agency in the formation of his thoughts and actions. It was the microbes and Kumagusu’s knowledge outside of the regime that fundamentally contributed to how he arrived at his theory of civilization based on queer nature.

This article ultimately opened up a historical time and space that emerged from queer nature, away from the teleology of ‘civilizational development’ modelled after the genealogy of the monolithic West. The historical paradigm that revolved around the West has left an immense impact on the ways in which philosophical theories arise, even in contemporary debates. Queer theory is one such instance. The newly opened paradigm of queer nature in modern Japan invites further questions on how historians and thinkers may be able to liberate other familiar ideas and methods from the conventional paradigm and discern novel historical phenomena and approaches.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Minakata Kumagusu Archives, Minakata Kumagusu Museum, Society for the Studies of Minakata Kumagusu, Wakayama City Museum, and Oxford Bodleian Library for the access to their archival materials, research assistance, and images. I would also like to thank the Rachel Carson Centre for the Environment and Society and its Landhaus Fellowship; the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures and its Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Fellowship; the Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies, St Antony’s College, and Faculty of History at the University of Oxford and their Designated ABRF Research Studentship Award, Oxford-Sasakawa Fund Scholarship, Writing-Up Bursary, STAR Award, Antonian Fund, and Storry Memorial Travelling Bursary; the Toshiba International Foundation and its Research Fellowship; the British Association for Japanese Studies and its John Crump Studentship and BAJS Studentship; the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and its Research Grant; the Sir Richard Stapley Educational Trust and its Research Grant; the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and its Sasakawa Japanese Studies Postgraduate Studentship; the European Association of Japanese Studies; the Faculty of Letters at Kyoto University; the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto; the Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, Berkeley; and, lastly, my current home institution, the Department of Global Studies, Aarhus University, Århus. I am grateful to friends, colleagues, and mentors, who all provided valuable comments at the above institutions and beyond, and the anonymous reviewers and the editor and copyeditor of Modern Asian Studies. In particular, I would like to thank Professor Sho Konishi, members of the Oxford Japanese History Workshop, Professor Amanda Power, Dr Christopher Harding, Professor Andrew Way Leong, and Professor Urs Matthias Zachmann. Last but not least, I am grateful for numerous discussions I had on relevant topics with the present-day polymaths Professor Rahul Santhanam and Professor Sonia Contera.

Competing interests

None.