1. Introduction

People with a personality disorder and an offending history are referred to in the literature as personality disordered offenders (PDOs). In England and Wales, this term is applied in practice to describe a population who are determined to have a high risk of further offending and are considered likely to have a severe personality disorder. This likelihood is determined on the basis of a structured screening process and clinical review [Reference Skett1, Reference Craissati, Joseph and Skett2]. Whilst the population may not have a formal diagnosis, the abbreviation PDO is adopted in this article for brevity and consistency with other England-based studies of the same population e.g. [Reference Brown3, Reference Brown and Völlm4]. The study reflects the reality of practice, rather than a research ideal, by sampling those who are identified by this screening process.

Occupational participation involves participating in personally meaningful and socially valued activities and roles [Reference Taylor5]. However, it must be recognised that the activities and roles people participate in can be antisocial or criminal. Occupational participation that is prosocial (i.e. within the law and not harmful to self or others) is an important outcome in its own right. Understanding occupational participation is important for PDOs because when prosocial, it is associated with health [Reference Stamm7, Reference World Health Organization8], desistance (ceasing offending) and reduced risk of reoffending [9–13]. The model of occupational participation with the strongest evidence base is the Model of Human Occupation [Reference Taylor5] which describes how occupational participation develops, is sustained and can be changed over time. However, it has not previously been applied with PDOs in the community.

Compared to people with an offending history but no personality disorder, PDOs have worse health and quality of life [Reference Black14], reoffend more often and more severely [Reference Yu, Geddes and Fazel15] and have more impairments in occupational participation [Reference Hill, Nathan and Shattock16]. Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has been associated with poorer outcomes than other types of personality disorder [Reference Zanarini17]. However, PDOs appear to have worse occupational participation still than people with BPD and no offending history [Reference Hill, Nathan and Shattock16, Reference Hill18].

Intervention to increase prosocial occupational participation has potential to improve outcomes for PDOs. However, due to a lack of research on this topic, interventions have not been robustly developed or evaluated for effectiveness. There is no evidence for effective interventions [Reference Connell19] and the factors that influence occupational participation for PDOs are unclear [Reference Connell20]. This limits practitioners’ abilities to intervene effectively.

Due to the lack of existing literature, this research used qualitative methods to identify what influences occupational participation for PDOs in the community.

2. Method

2.1. Theoretical framework

Drawing from narrative research principles [Reference Squire21], narratives were understood from a critical realist perspective [Reference Danermark22, Reference Bhaskar23]. Each participant’s narrative represented his or her ‘reality’ which itself was an interpretation informed by their life experiences. Consistent with the view of narrative as constituting experience [Reference Ricoeur24], an occupational narrative is a person’s occupational participation over the life course. An occupational narrative influences how a person participates in occupations in the present, how they attribute meaning to occupations, and how they anticipate their future [Reference Kielhofner25–Reference Melton and Taylor28]. Occupational narratives provide a vehicle to identify the mechanisms influencing occupational participation at a point in time, whilst recognizing their basis in distal events that may continue to act to influence occupational participation.

2.2. Study participants

Men and women supervised by the National Probation Service (NPS) in a city region in England were purposively sampled if they were identified as PDO, were aware they had been identified as such, lived in the community (not prison or hospital), were aged over 18, spoke English and could give written informed consent. Participants were identified as a PDO if they scored above a pre-determined cut-off on a structured screening tool [Reference Craissati, Joseph and Skett2] and following review by qualified psychologists.

2.3. Sampling and recruitment

Stratified purposive sampling identified participants identified as PDOs who were demographically representative of the NPS caseload in the region. Age, sex, ethnicity, offence type and employment status (a proxy of occupational participation) were selected as variables, as they were theoretically relevant to occupational participation, desistance and personality disorder diagnoses. An absence of women in studies of the factors influencing occupational participation for PDOs in the community [Reference Connell20] and their low representation on the NPS caseload (5%), informed proportional over-sampling of women to ensure a diversity of experience. Sampling ceased when no new findings were identified during analysis.

Potential participants were identified by NPS administrative staff. The respective offender managers (criminal justice practitioner supervising the person) made the initial approach to secure consent to be contacted by the researcher. A participant’s name was only shared with the researcher when consent to contact was given. Informed consent was taken by the researcher and an interview was scheduled after a cooling off period. Participants were free to withdraw at any point without giving a reason and were informed that involvement in the research would have no effect on their work with the NPS. Participants’ offender managers were not present during interview.

2.4. Data collection

Interviews were conducted at the NPS premises the participant routinely attended. Participants were familiar with the layout and security apparatus. Interviews consisted of two components and lasted 45–120 min. They were audio-recorded with participants’ consent.

The first component was a narrative interview using the broad open question “what is day-to-day life like for you?” This ensured that participants’ narratives were not curtailed. The second component was a semi-structured interview utilising the Occupational Performance History Interview – Version Two (OPHI-II)[Reference Kielhofner29]. The five interview themes (routines, roles, activity choices, environments and turning points) are considered across the life course, providing prompts to support participants to share their narratives. As a well-established clinical assessment, piloting was not required.

Interviews were conducted by a woman researcher (CC) with clinical experience in the field but no prior relationship with the participants or the NPS. Field notes were taken to capture impressions, theoretical links and reflections on interviews. They facilitated scrutiny of researcher influence on the analysis, prompted consideration of alternative theories and supported reflexivity.

2.5. Data analysis

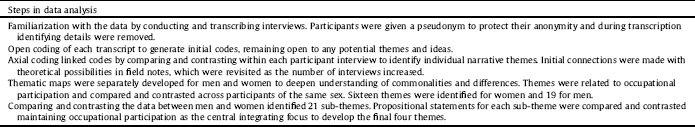

Data were analyzed using a grounded theory informed approach [Reference Robson30–Reference Glaser and Straus32] supported by MAXQDA software [Reference Software33]. The analysis proceeded as described in Table 1.

2.6. Credibility

A Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group advised on research design and appraised the resonance of the findings with their experiences. Strategies adopted to ensure credibility [Reference Lincoln and Guba34] included: concurrent data collection and analysis; independent second coding of a proportion of transcripts, whereby agreement was confirmed between coders (CC, EAM); verbatim quotation in presenting the results; description of the research context; and the use of field notes and a reflexive position statement. This research was part of a wider mixed-methods study in which half the participants validated the results, which incorporated the findings in this article (in preparation).

Table 1 Steps in data analysis.

2.7. Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Biomedical Science Research Ethics Committee, University of Warwick. Additional approvals were obtained from Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (formerly the National Offender Management Service) and Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

3. Findings

3.1. Participants

Table 2 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the 13 men (72%) and five women (38%) participants. One participant who consented to contact did not meet inclusion criteria and one lost contact with their supervising offender manager. They were replaced using the purposive sampling framework. Themes influencing occupational participation are presented.

3.2. Narrative themes

Four themes describe the influencers of occupational participation for PDOs in the community. Table 3 shows each theme and the sub-themes it includes. Participants pseudonyms are presented alongside their respective verbatim quotations to demonstrate findings were developed from the range of participants.

3.2.1. Function of occupation

This theme reflects how occupational participation performed certain functions for the participants. The form of the occupation (e.g. fishing, cooking, ‘drifting’, using substances) was often irrelevant compared to the need it met for the individual person. Seven sub-themes describe commonly identified functions.

Most participants undertook occupations in response to or to/escape unpleasant feelings. Cos if I get really irritable, I, I have to, go to the gym for like five hours… (Loelle). If they were concerned an occupation risked an unpleasant experience or feeling, many participants avoided the activity all together.

It’s a lovely day. An I like, I could just. I’d love to go on my bike and have a ride round but I can’t. Cos I know. I dunno. If I bump into someone. Or if someone bumps into me, I’m gonna flare up (Steve).

Several participants described doing activities to access a pleasant feeling. …but I just do it for the, I don’t do it for no- any reason, it’s just to, just to get a buzz out of it man (Faisal). Whilst others described a desire to create stability and security. That’s probably why I kept going back. Because when I’m not there I haven’t got that structure, but when I’m there, there’s everything that’s in place (Jackie).

Table 2 Participant demographics.

Table 3 Themes and subthemes.

Some participants undertook activities that performed a function of validating their emerging identity. Marcia describes how being a fighter and mother shaped her occupational participation.

Like me just keep in fighting. Look after kids, and myself, and me just want to show other mothers, have for sure like, family member, certain people in a better position, you know. Especially like some government people, more of a show them, you know what? People can change (Marcia).

Other participants continued occupations because of a wish to experience mastery. I’m amazing myself that I can do these things. Erm. Which is positive really(Angela).

A final subtheme was found only in the men’s narratives, where occupations performed a function of enhancing self-perception of status and significance. And unfortunately, in this world you either need the money or power and that comes with the job title (Mark).

The function of occupations played a large role in motivating occupational participation. Participants learned the effectiveness of particular occupations and repeated them, indicating the importance of past occupational participation on current occupational participation. The next theme expands on the influence of the past.

3.2.2. Influence of the past

Five sub-themes were: I’ve matured; I’ve missed out; consistent/lost occupations; turning points; and intruding past.

Some participants recognized their past occupational participation as different, allowing them to position their present self as more mature, wiser and seeing things clearly. I’m all grown up now, you get me? (Danny). Some attributed their current difficulties to having missed out on quite a lot (Mark), including belonging in a family, and social connection with peers in their childhoods.

Most participants had one or more occupations that they consistently participated in. These could be either socially valued or disapproved of, with many participants having both. …I have stopped on the odd occasion. Obviously when I was in prison for four years. Couldn’t go fishing there (Jamie). Several participants had not managed to sustain valued occupational participation.

But obviously I want to get back to the stage where I was buying ingredients and just erm, cooking it meself. Because I enjoyed cooking as well. I used to enjoy it man… that would give me a buzz as well like (Aaron).

The turning points sub-theme describes how a past event or interaction could impact on the trajectory of someone’s occupational participation. She said something to me one day which really just like, she just, put fire inside me stomach. She says to me (pause), “me would never change” (Marcia).

The final sub-theme relating to the influence of the past was where participants could not keep the past in the past. It intruded into their day-to-day life uncontrollably, disrupted their attempts at occupational participation or elicited occupational participation which functioned to manage distressing intrusions. …my life was just traumatic and in the end that, that’s wor I done [index offence], because I felt like I wasn’t getting any help or anythink. (Shelley).

The influence of the past theme indicates that past experiences of occupational participation had a marked impact on what participants did and did not do, if and how participants understood their current occupational participation, and on motivation for future occupational participation. Some participants identified how their occupational participation changed over time, often influenced by significant event that acted as a catalyst for change. Many continued to view change as something under the control of external forces.

3.2.3. External forces

Participants described how things out with their control influenced their occupational participation. Sub-themes describe the main ‘forces’: mood and mental disorder; uncontrollable circumstances; interfering authorities; helpful rescuers; and faith and purpose.

Many participants strongly attributed variation in occupational participation to mood and mental disorder. If I feel good I clean straight away. If I feel bad. I have a drink and that first and. Jump back in bed and just, slouch around (Brendan). Uncontrollable circumstances were described by several participants, which contributed to avoiding social contexts.

Someone in a supermarket, the trollies. They leave their trolley over there and they walk up to the other aisle. That irritates me. A couple of times I’ve rammed their trolley out the way. Just. Bashed it cos, it’s just, frustrating for me. But I’m trying, I’m trying my hardest to keep a lid on it…It’s horrible. I just can’t do nothing about it (Steve).

Services for PDOs could be viewed as interfering or rescuing. Sometimes the same participant held both views.

Strangers are dictating to us. It’s just. It does me head in, having to do all this conforming and. You know like. People that don’t even know you telling you what to do. It just drives me potty (Michael).

And I call [offender manager] the, the‘persistent little [indicates swearing but doesn’t] before, yeah. Cos she just doesn’t give up (smiling) (Jackie).

Finally, several participants described religious faith or another set of beliefs as enabling them to continue with what had been a difficult life experience to date.

I’m here for a reason. Erm. It’s linked to my beliefs. But, it’s a bit more, because I feel that, I have, a purpose. Not that I’m hundred per cent sure what it is yet (Mark).

Within this theme there were variations in the way participants viewed external forces acting on their lives. Participants had different perceptions about the degree to which they could control the external forces and/or their response to them, and about whether they were a help or a hindrance. The more participants felt a sense of personal control the more they recognized that they had the potential to learn new strategies and adapt to life changes.

3.2.4. Learning and adaptation

The final theme was the need to learn and adapt to new ways of occupational participation. Participants described using activities and roles to facilitate this adaptation process. The inter-relationship between occupational participation as means of change and the outcome of change is captured in four sub-themes: learning adult norms; shaping a new adult identity; exploring; and discovering new reasons to participate in occupations.

Many participants talked about how they were learning adult norms for the first time.

How they. Resolve conflicts without using violence. An I, I try to pick up on that. (long pause).…Yeah. I, I’m, I’m not a people skills person. That’s, that’s why when I’m, listening to the er, guys at work. How, how they deal with the customers on the door (Paul).

Participants were trying to build a new identity for themselves, though they had different levels of success.

Coming out an changing my life but like, remembering that, I could walk into a shop and the shopkeeper might remember me and say that like,“oh, like, you’re the geezer that used to come in my shop and take this and take that”(Danny).

Several participants talked about how they were experiencing a completely new situation. Some were exploring different occupations. I’m not weird, it’s like, I just like to, venture out innit (Faisal). However, many participants were frightened to explore and preferred staying in their own home. For three years I’ve been alone, really, at home. These, these good days that I have. Erm. There not very, er. Regular occurrence (Brendan). Some of the participants described how, for the first time they were participating in an occupation out of choice rather than in reaction to another need. This was less common, but it was significant for the participants who described it.

We go out to eat. Or sometimes we stay in and I cook. An we go shopping. Like. We just do normal things. Like, what we shoulda been doing in the first place (Loelle).

Participants were attempting to adapt to a life in the community where their identity had changed and they had to learn new ways to participate in occupations that supported this change. This was a challenge for many of the participants who had a long history of difficulties. They approached it in different ways, with different levels of social support and with different levels of success.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion

These findings demonstrate that occupations valued by society (prosocial occupations) as well as those considered antisocial are undertaken by PDOs because they perform a function, and that both the occupation and its function vary by person. Narrative research methods may be particularly useful in identifying the function of occupation. A narrative study of self-harm (which can be conceptualised as an occupation, albeit one considered harmful) also found that occupational participation was functionally driven. Because self-harm functioned to effectively reduce unpleasant emotions, it became an established strategy over time [Reference Morris35]. This research with PDOs used a larger sample and more men than women, strengthening the importance of considering the function of occupation. Narrative approaches may assist a practitioner in identifying why a person seeks or repeats participation in particular occupations, and to intervene in a way that enables them to meet their needs by participating in alternative prosocial occupations.

For men, occupational participation performed a function that was not identified for women, the need for status and significance. Herrschaft et al. [Reference Herrschaft36] investigated transformation narratives (narratives about a change for the better) of eight men and 23 women. All the men identified status factors in their narrative of change (100%, n = 8), but only 43.5% (n = 10) of women. Although their study was not focused on occupational participation, finding that status was evident in some women’s narratives suggests that if more women been sampled in this research, status and significance may have been identified as influencing occupational participation for some women.

Historical occupational participation influenced occupational participation in the present and the PDO’s anticipation of future occupational participation. Past difficulties in prosocial occupational participation and adverse past experiences were reported by all the PDOs. Adverse experiences are highly prevalent in offender populations [Reference Singleton, Meltzer and Gatward37]. Childhood adversity is known to effect health outcomes and increase the likelihood of future violence or self-directed harm [Reference Hughes38]. These findings suggest that childhood adversity also has a lasting impact on occupational participation. There is limited literature that considers how childhood adversity may continue to influence occupational participation as an adult, or if occupational participation as a child has a protective effect against poor outcomes in the longer term.

Some participants’ occupational narratives and occupational participation were disrupted by recollections of accumulated traumatic experiences. Literature considering how past (and ongoing) traumatic experiences influence occupational participation is limited. These findings suggest that the distress caused by ongoing reactions to traumatic experiences may result in some PDOs reverting to habituated occupational participation that may bring them into conflict with the law. Whilst the past is not modifiable in an intervention, the ongoing influence of traumatic experiences and childhood adversity on occupational participation may be. It must be better understood across populations and warrants further research attention.

Discussing past occupational participation where a participant experienced mastery and other positive outcomes in interviews was a powerful means of generating internal motivation. Facilitating someone to become aware of discrepancies between how things could be and their current position is central to motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is applied in behavioural change interventions and is useful where there may be resistance. It has been used with offenders [Reference Treasure39, Reference McMurran40]. However, participants did not always view themselves as able to make changes to achieve a goal. They often lacked a sense of agency, viewing mood or their response to the environment as something outside their control. This finding is supported by a narrative study of people with and without Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), where a lack of agency differentiated the narratives of participants with BPD from a matched sample without BPD [Reference Adler41].

Occupational participation was found to be the outcome, but also a contributor to the change process. This is consistent with systematic review findings of factors that influence occupational participation [Reference Connell20]. This phenomenon is described in the Model of Human Occupation, and termed ‘occupational adaptation’. Although not explicitly cited, occupational adaptation is evident in recovery among general and forensic mental health service users [Reference Stickley and Wright42–Reference Drennan45] and desistance from offending [Reference Maruna9, Reference Ward and Brown46]. These research findings explain how what is variously termed ‘meaningful activity’, ‘generative activity’, ‘excellence in work’ etc… may operate to facilitate changes, whereby a person redefines themselves as a person in society distinct from an illness, disorder or offence through occupational participation.

Facilitating occupational adaptation is central to occupational therapy in forensic settings, where the Model of Human Occupation is the most commonly used practice model [Reference Connell47, Reference Connell48]. These findings indicate that practitioners working with people with personality disorder and/or PDOs in the community to increase occupational participation should consider intervention informed by occupational adaptation and particularly attending to the functional nature of occupational participation in this population. Service providers who wish to provide a service designed to increase occupational participation may wish to consider the skill-mix in the team.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

The primary limitation of this research is that the participants were not required to be diagnosed with personality disorder or other mental disorder/s. Given the high prevalence of personality disorder in probation populations [Reference Brooker49] and that the participants had been screened as likely to have severe personality disorder, it is more likely than not that participants would have met diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder. Different types of personality disorder may be associated with different influences on occupational participation in people with criminal justice involvement. As the sample did not require a diagnosis, this cannot be determined from this research. Further, a confirmed diagnosis of personality disorder or of specific types of personality disorder is usually unavailable to practitioners working in probation. As such this research reflects the experiences of the population seen in practice. Nonetheless, there is potential that some participants may not have had a personality disorder and thus findings should be applied with caution and built on in further research where the sample includes diagnostic data.

Despite the purposive sample resulting in participants with diverse characteristics, there is always selection bias in research. Those unwilling to participate may have had different experiences, therefore full representativeness is not claimed. However, participants discussed historical experiences where their engagement with probation and society would have precluded participation in this research, indicating that these experiences may have been captured.

5. Implications

5.1. Implications for practice

When working with PDOs in the community to change occupational participation, practitioners may:

• Consider the function of occupations, the influence of the past, a person’s degree of agency, and the learning process that has to occur

• Conduct interventions informed by occupational adaptation that are based on an understanding of occupational participation over the life course

5.2. Implications for research

Further research should:

• Develop an intervention using occupational adaptation to increase prosocial occupational participation for PDOs in the community and evaluate its effectiveness

6. Conclusion

Four themes describe the influences of occupational participation for PDOs in the community: function of occupations; influence of the past; external forces; and learning and adaptation. These findings highlight the importance of considering occupational participation over the life course with this population. Occupational adaptation was identified as a theory to explain change in occupational participation. These findings support the application of interventions informed by occupational adaptation in practice.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Catriona Connell is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Health Education England (HEE) Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship (ICA-CDRF-2015-01-060) for this research project. This paper presents independent research. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.