The Mediterranean diet (MD) is considered to be one of the most influential dietary patterns in relation to health. Its composition is principally based on food groups that are characteristic of Mediterranean zones. At the same time, it also incorporates a way of cooking and a lifestyle that includes physical activity (PA) engagement, sufficient rest and socialisation during meals. The MD possesses common patterns such as the inclusion of cereals, vegetables and fruits in all meals, together with a moderate consumption of dairy products. Equally, the use of olive oil as the main source of fat is considered fundamental and weekly incorporation of animal or vegetable protein is also required. On the one hand, with regard to proteins that are of animal origin, consumption preferences should be directed towards fish (≥2), eggs (2–4 times a week) and white meats (≥2), with red meats being consumed in lower quantities and at a lower frequency (≤2). On the other hand, legumes are the main source of vegetable protein (≥2). Finally, water provides the main source of hydration(Reference Bach-Faig, Berry and Lairon1).

MD adherence has been demonstrated to exert protective effects against CVD, coronary diseases, acute myocardial infarctions and cancer(Reference Rosato, Temple and La Vecchia2,Reference Schwingshackl, Schwedhelm and Galbete3) . Relationships have been found in adolescents between a healthy diet and various cardiovascular risk factors, such as blood pressure(Reference Bacopoulou, Landis and Rentoumis4) and cholesterol(Reference Zhong, Lamichhane and Crandell5). On the other hand, the MD has also been demonstrated to exert positive effects on quality of life perceptions, PA levels and sleep quality. Further, the impact has been shown on obesity, although these results are not conclusive(Reference Evaristo, Moreira and Lopes6–Reference Ferranti, Marventano and Castellano8). In addition, greater MD adherence is associated with a lower risk of suffering from mental illnesses, especially those with depressive symptomology(Reference Altun, Brown and Szoeke9).

Nonetheless, despite the diverse array of benefits shown for health, trends in recent years show a reduction in adherence to the traditional MD and a rise in less healthy habits amongst children and adolescents(Reference Cabrera, Fernández and Hernández10,Reference Thana, Takruri and Tayyem11) . In this sense, the maintenance of healthy dietary patterns during adolescence could prevent the risk of suffering from health problems during adulthood(Reference Hu, Jacobs and Larson12–Reference Pearson, Miller and Ackard14).

Thus, evaluation of the factors influencing MD adherence is key for better understanding of the current situation. In this way, choices regarding food consumption can be determined at an individual level according to age, nationality, sex, preferences, nutritional knowledge, physiological state and psychological factors(Reference Arcila-Agudelo, Ferrer-Svoboda and Torres-Fernàndez15–Reference Conner, Povey, Sparks and Murcott17). On the other hand, socio-cultural factors such as social norms, the influence of family and peers, socio-economic status, the media and social networks appear to play a mediatory role over dietary habits(Reference Moreno-Maldonado, Ramos and Moreno18,Reference Higgs and Thomas19) . Finally, the influence of setting, in the same way as access to and availability of healthy foods, also intervenes in dietary choices(Reference Gustafson, Jilcott and McDonald20).

The majority of studies dealing with the MD in adolescents studied its relationship with obesity or other variables mainly associated with physical health. However, the present study approaches the analysis of adherence to an MD from a broader perspective, examining its relationship with various indicators, not only of physical health but also psychological and social health, whilst also analysing its association with different socio-demographic variables and potential predictive factors. To this end, various instruments were used to assess the different dimensions of health. Instruments assessed adolescents’ adherence to the MD, PA level, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, body image satisfaction, hours of nightly sleep, BMI, maximal oxygen uptake, academic performance and socio-demographic factors.

Methods and procedures

Participants

A descriptive, cross-sectional and correlational study was carried out with a representative sample of adolescents undertaking secondary education at educational centres in La Rioja, a region in the north of Spain. The sample was obtained through stratified random sampling according to clusters, in which secondary education classrooms in all centres of the region provided the sampling unit. Of a total of 6018 adolescents enrolled in these classrooms, it was estimated that the number required for sampling to be representative was 362 (95 % CI). A final sample of 761 adolescents was obtained from twenty-five educational centres. Participants were aged between 12 and 17 years (14·51 (sd 1·63) years), with 49·7 % being female and 50·3 % being male.

Procedure

Written informed consent was requested from adolescents’ parents or legal guardians. The collaboration of adolescents in the present study was voluntary, and all provided verbal consent. The fundamental ethics of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected. In addition, the project was approved by the Ethical Committee for Clinical Research of La Rioja. Members of the research team carried out fieldwork during teaching hours at the educational centres, with all members following the same action protocol: self-completion questionnaire, anthropometric measures and physical aptitude test.

Instruments

MD adherence was evaluated using the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and teenagers (KIDMED) questionnaire developed by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo21). The instrument comprises sixteen items with dichotomous response options (‘yes’ or ‘no’) in relation to the consumption of foods related to Mediterranean dietary patterns. The procedure established by the author was followed in order to derive an overall adherence score, with possible values falling between minus four and twelve. The final derived score was then classified according to the parameters indicated by the author of the questionnaire: low (≤3), medium (4–7) or high (≥8). For data handling, adolescents reporting low (4·7 %) and medium (46·3 %) MD adherence were grouped together due to the low percentage reporting the former.

Health-related quality of life was estimated through the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire, developed and validated within Spanish adolescents by Aymerich et al.(Reference Aymerich, Berra and Guillamón22). This questionnaire is formed by twenty-seven items which are grouped according to five dimensions and rated along a Likert scale. The dimensions are as follows: physical well-being, psychological well-being, autonomy and parenting, school environment and social support and friends. Obtained data were handled in accordance with the parameters established by the authors of the questionnaire, with higher values corresponding to more positive perceptions of health-related quality of life(23).

Evaluation of self-esteem was performed using Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale, adapted and validated by Atienza et al.(Reference Atienza, Moreno and Balaguer24) in Spanish adolescents. This scale is formed by ten items, with responses being rated from one to four, permitting final scores of between 10 and 40. In this way, higher scores are related to higher self-esteem.

For evaluation of perceptions of and satisfaction with body image, the method described by Stunkard & Stellar(Reference Stunkard, Stellar, Cash and Pruzinsky25) and adapted by Marrodan et al.(Reference Marrodan, Montero and Mesa26) was used. For this evaluation, nine silhouettes of female figures are used in addition to nine male figures. The silhouettes show a progression towards a stockier appearance and correspond to different BMI values, running from 17 up to 33 kg/m2. Participants were asked to choose two silhouettes, the one with which they most identify themselves based on their actual appearance and the silhouette representing the figure they wished they had. In this way, the difference between both silhouettes is calculated, grouping adolescents according to two categories: adolescents who are satisfied with their body image (values between –2 and 2) and those who are dissatisfied (all values outside of this range).

The PA level was estimated using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents, adapted and validated within Spanish adolescents by Martínez et al.(Reference Martínez, Martínez de Haro and Pozo27). This questionnaire evaluates the PA engaged in during the last 7 d, as a function of frequency and time-frames. Obtained values are between one and five, with higher values being associated with greater engagement in PA. In addition, two questions are posed in relation to engagement in organised sporting activities and the mode of transport used to arrive at the educational centre: ‘Do you engage in any extra-curricular sporting activity after school?’ and ‘Do you exercise when you go from home to school (walking, cycling, skating…)?’ With the aim of calculating hours of nightly sleep, adolescents were also asked about the time at which they typically went to bed and woke up.

Evaluation of setting was analysed through the Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and fitness at population level project (ALPHA) environmental questionnaire developed by Spittaels et al.(Reference Spittaels, Verloigne and Gidlow28) within the ALPHA Project of the European framework. This questionnaire evaluates perceptions of factors within one’s immediate environment (from within approximately 1·5 km of the home) which may influence PA engagement. A version of this instrument was used which was adapted for the Spanish youth population and validated by García-Cervantes et al.(Reference García-Cervantes, Martinez-Gomez and Rodríguez-Romo29). Scores are obtained by summing together the ten questionnaire items. Higher results represent a more favourable setting for engaging in PA. Results were categorised using the median as the cut-point. This enabled two potential settings: favourable or unfavourable.

With regard to socio-demographic data, adolescents reported their sex, date of birth and nationality (‘born in Spain’ or ‘born in another country’). For evaluation of socio-economic status, the family affluence scale (FAS II) was used(Reference Currie, Molcho and Boyce30). This constitutes four questions related to family possession of material goods. The final score ranges between zero and nine, with results being categorised in the following way: low (≤2), medium (3–5) or high (≥6). For data handling, adolescents reporting a low socio-economic status (1·8 %) and a medium socio-economic status (28 %) were grouped together due to the low percentage reporting the former.

Likewise, the Oviedo response frequency scale(Reference Fonseca, Paíno and Lemos31) was also used with the aim of detecting and excluding from data analysis any questionnaire data which had been provided in a random, dishonest or pseudo-random way. The Oviedo response frequency scale is a self-report instrument that includes questions which demand dichotomous (yes or no) responses. In this way, six items were introduced in an interspersed way throughout the questionnaire (for example, ‘have you ever used the bus?’ or ‘have you ever seen children playing in the park?’). Adolescents who provided responses that most contradicted logic were excluded from the analysis, more specifically, two were excluded for this reason.

For the measurement of height and weight a Holtain® (Holtain Ltd.) stadiometer and SECA® scale were used, with a precision of 1 mm and 0·1 kg, respectively. Anthropometric measurements were performed according to the protocols of the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry(Reference Stewart, Marfell-Jones and Olds32). Following this, BMI was calculated and adolescents were categorised as a function of reference values established by the WHO: normal weight, overweight and obesity(Reference Onis, Onyango and Borghi33).

Evaluation of aerobic capacity was conducted with the Course-Navette Test. For this, two transversal lines marked a distance of 20 m, indicating the start and finish of the run route. Participating adolescents had to maintain a race speed that was dictated by an acoustic signal. This determined the time in which participants had to successively cover the distance between both lines. The acoustic signal began the race at a speed of 8·5 km/h, increasing by 0·5 km/h every minute. In this way, each adolescent finished the test when they stopped or failed, on two successive occasions, to complete the route within the time indicated by the signal. Through the results obtained, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) was calculated according to the formula stipulated by the author who conceived the test(Reference Leger, Mercier and Gadoury34).

Finally, academic performance was analysed through the grades provided by the Educational Council of the Government of La Rioja. Specifically, this outcome was obtained by recording the average mark obtained by the adolescent for the school year they were undertaking at the time of the study. Ninety percent of families gave their express consent for these grades to be provided to the research team.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were represented according to means and standard deviations, whilst in exchange, qualitative variables are given according to frequencies. Normality and homoscedasticity of the data were verified with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Levene test, respectively. Means were compared through the Student’s t test and the Mann–Whitney U for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. The Pearson χ 2 test was used to analyse the associations between qualitative variables.

Factors associated with the MD score were analysed via univariate analysis. Pearson and Spearman indices were used for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. Following this, a multiple linear regression model was developed using backward elimination. The aim of this was to identify predictors of the MD score and to control for the effect of confounding variables. This analysis included the variables of age, nationality, sex, socio-economic status, setting, BMI, body satisfaction, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, PA, maximal oxygen consumption, hours of nightly sleep and academic performance. This same analysis was carried out as a function of sex. Models met the assumptions of multiple regression in terms of linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, independence and non-multicollinearity. All statistical analyses were carried out using the programme IBM-SPSS® in its version 25 for Windows. A statistical significance was established at P < 0·05.

Results

Adolescents’ age, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, PA engagement, aerobic capacity, hours of nightly sleep and BMI are shown in Table 1 as a function of MD adherence. For all variables, the analysis revealed significantly higher values on the part of adolescents with high MD adherence. The only exceptions were found for age, where a significant inverse relationship was uncovered, and BMI, where no significant differences were found.

Table 1. Characteristics of study sample according to Mediterranean diet (MD) adherence(Mean values and standard deviations)

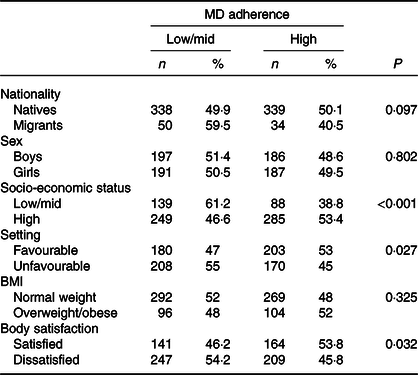

Table 2 presents outcomes for the analysis of influential factors with regard to MD adherence. Greater adherence is observed on the part of adolescents with a high socio-economic status and who reside within settings that are favourable towards PA engagement. In the same way, greater adherence was reported by adolescents who were satisfied with their body image. Despite failing to find statistically significant findings in relation to nationality, a greater prevalence of high adherence was highlighted amongst natives (50·1 %), relative to migrants (40·1 %).

Table 2. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) according to different factors(Numbers and percentages)

Table 3 shows the frequency with which certain foods are consumed as a function of various socio-demographic factors. Migrants reported a lower consumption than natives of dairy products, fish and legumes, in addition to a higher consumption of pasta or rice and sweets. With respect to socio-economic status, adolescents with a high status reported significantly higher percentages for the consumption of breakfast cereals, fruit and juices, fish, legumes and second servings of fruit and dairy products. In contrast, consumption of pasta, rice and sweets was higher in adolescents with a low/medium socio-economic status. Finally, differences were also observed as a function of setting in that those who were residents in zones that favoured engagement in PA reported higher frequencies for the consumption of fruit and juices and vegetables and fish alongside a lower consumption of pasta and rice.

Table 3. Consumption of foods related with the Mediterranean diet according to nationality, socio-economic status and setting (Percentages)

* P < 0·05, ** P < 0·01, *** P < 0·001.

Table 4 details the correlation coefficients relating MD with age, socio-economic status, sleep, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, PA, VO2max and academic performance. Higher MD adherence was inversely associated with age and positively associated with socio-economic status, hours of nightly sleep, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, PA engagement, aerobic capacity and academic performance. This association was present in both females and males.

Table 4. Correlation coefficients related to Mediterranean diet (MD) adherence (Spearman’s and Pearson’s correlation coefficients)

HRQL, health-related quality of life, PA, physical activity.

* P < 0·05, ** P < 0·01.

Finally, the multiple regression model using backward elimination is shown in Table 5. Being female, having a higher level of PA and self-esteem, better academic performance and achieving more hours of nightly sleep were found to be predictive factors of MD adherence. When considering sex-related differences, better academic performance and a greater number of hours of nightly sleep were only predictors in the case of boys, whilst VO2max, self-esteem and environment were only predictors for girls.

Table 5. Predictors of Mediterranean diet (MD) adherence* (β Values and 95 % confidence intervals; standard deviations)

β, Regression coefficient.

* Variables entered into model: age, nationality, sex, socio-economic status, setting, BMI, body satisfaction, health-related quality of life, self-esteem, physical activity, maximal oxygen consumption, hours of nightly sleep and academic performance.

Discussion

Results of the present study showed that adherence to an MD was related to various physical and mental aspects including socio-demographic variables, lifestyle habits and health indicators. Through scores obtained on the KIDMED, we can see that 49 % of adolescents presented high values of MD adherence, 46·3 % had moderate adherence and 4·7 % showed a low adherence. In this sense, results show similar trends to those reported in the Enkid study by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo21) with a representative sample of the Spanish population aged from 2 to 24 years (with 46·4 % reporting high adherence). It also corroborates results obtained in a study by Mariscal-Arcas et al.(Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Rivas and Velasco35) in adolescents from Granada (46·9 %). Nonetheless, values for high adherence were higher than those found in a sample of Andalusians (30·9 %) and Catalonians (26 %)(Reference Grao-Cruces, Nuviala and Fernández-Martínez36,Reference Fauquet, Sofi and López-Guimerà37) and were relatively higher than those found in other homologous Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Greece and Turkey (9·1, 26 and 22·9 %, respectively)(Reference Mistretta, Marventano and Antoci38–Reference Sahingoz and Sanlier40). Such differences, identified as a function of geographic region, underline the importance of better understanding the factors that impact upon MD adherence.

Through multivariate analysis, we were able to establish predictors of MD, with sex emerging as a determining factor. Along the same lines, a study carried out in twenty-one European countries revealed that females were more likely to consume fruits and vegetables(Reference Stea, Nordheim and Bere41). This finding could be partly explained by the greater interest shown by females in weight control and body image(Reference Field, Camargo and Taylor42). In this way, the pressure resulting from the promotion of beauty ideals of thinness by the mass media and social media encourages healthy food choices, leading to the avoidance of fat and salt and a higher consumption of fruit and fibre(Reference Wardle, Haase and Steptoe43).

With regard to PA, engagement was significantly higher in adolescents with MD high adherence, with this proving to be a predictive factor in both sexes. Thus, a higher level of PA has been associated with a greater consumption of fish, fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes and olive oil(Reference Muros, Cofre-Bolados and Arriscado44). Further, in agreement with the present study, the aforementioned research also demonstrated that adolescents with high MD adherence reported significantly higher values in relation to VO2max. This finding may be due to PA levels themselves, with numerous studies unveiling the association between PA and subsequent physical condition(Reference DeFina, Haskell and Willis45). However, our results only showed the predictive value of VO2max in the case of girls.

With regard to setting, adolescents residing in favourable contexts for PA engagement had significantly higher adherence rates to the MD, alongside a higher consumption of fruit, juices, vegetables and fish. This fact could be associated with socio-economic status as present results confirmed a positive correlation between setting and socio-economic status (r 135). In this way, adolescents living in areas with greater opportunities for PA also had a higher socio-economic status, with this potentially having a direct impact on access to food purchases. However, our results identified the setting as a predictor only in the case of girls.

In the same way, self-esteem was also shown to be a valuable predictor. Previous studies have shown that the consumption of fruits and vegetables is directly associated with psychological health(Reference Boehm, Soo and Zevon46), exercising a protective role against depression, anxiety and psychological distress(Reference Sadeghi, Keshteli and Afshar47). However, our results only showed the predictive value of self-esteem on MD in girls. In this sense, the importance of body image on girls’ self-esteem could lead to a desire for weight loss and, therefore, greater diet control. In this way, improvements to self-esteem appear to be key for preventing the development of eating disorders in girls(Reference Argyrides and Kkeli48).

In respect to hours of nightly sleep, significant differences were also found, with adolescents who more strictly adhered to an MD reporting more hours of sleep. These results collaborate those reported by Rosi et al.(Reference Rosi, Giopp and Milioli7). In the same way, Ferranti et al.(Reference Ferranti, Marventano and Castellano8) reported that sleep duration was positively associated with the intake of fruits and vegetables and inversely related to the consumption of sweets and snacks. In our results, this duration turned out to be a predictor of MD in the case of boys.

Finally, academic performance was superior within adolescents with better MD adherence. This relationship has already been reported previously and has been determined to occur independently of factors such as BMI and PA(Reference Argyrides and Kkeli48). In the same way, Frisardi et al.(Reference Frisardi, Panza and Seripa49) confirmed the relationship between consumption of foods inherent to the MD and conservation and improvement of cognitive processes. Such dietary practices appear to offer protection through vascular inflammation and oxidation which results in better neuronal conservation. Along the same lines, Chacón-Cuberos et al.(Reference Chacón-Cuberos, Zurita-Ortega and Martínez-Martínez50) uncovered positive associations between high MD adherence and processes related to learning strategies and motivation. This led to better scores for elaboration strategies, organisation, critical thinking, effort regulation and study habits and time. In our study, academic performance was even a predictor of MD adherence in boys. In this way, these results could serve as a call to promote the importance of a healthy diet.

Besides the predictive factors described above, MD was shown to be associated with other socio-demographic variables and indicators related to adolescent’s mental well-being. First, individuals with high NSE reported greater adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns. This coincides with studies that have evidenced greater consumption of fruit, fish and legumes, in addition to lower consumption of pasta, rice and sweets(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas and Ngo21). On the other hand, MD adherence was inversely correlated with age. This could be associated with the greater influence of peers with increasing age, alongside increases in autonomy and financial independence(Reference Moreno-Maldonado, Ramos and Moreno18). With regard to indicators of mental well-being, adolescents with greater MD adherence also reported higher levels of health-related quality of life and body satisfaction. In this sense, previously conducted studies have already uncovered relationships between the MD and various quality of life dimensions(Reference Knox and Muros51), whilst also revealing dietary restrictions which are non-characteristics of Mediterranean patterns amongst adolescents who are unhappy with their body weight(Reference Bibiloni, Pich and Pons52). Nonetheless, none of these associations proved to be determinant in the multivariate analysis. Thus, given the potentially confusing effects produced, the present results should be treated cautiously.

One of the main strengths of the present study is based on its inclusion of a representative sample which enables us to extrapolate the influence of socio-demographic factors on MD adherence to wider populations. This is also true for the associations between these factors and diverse health indicators, both physical and mental, providing a global view in the analysis of MD. Nonetheless, the present study is not exempt from limitations. Self-complete questionnaires were used which are susceptible to the subjectivity of participants. Future studies should be considered which use instruments that provide greater objectivity and data precision, including food consumption diaries or accelerometers. This being said, the data collection protocol was the same for all adolescents, protected anonymity and used valid instruments that had demonstrable reliability within populations similar to that used in the present study. On the other hand, the use of a cross-sectional design in the present study makes it impossible to determine the direction of associations. This makes it necessary to develop future research studies which are longitudinal and experimental in nature.

Conclusion

The results obtained show that 49 % of the included adolescent population presented high MD adherence. Being female, having higher PA levels and self-esteem, better academic performance and more hours of nightly sleep were found to be predictive factors of MD adherence. When considering sex-related differences, better academic performance and a greater number of hours of nightly sleep were predictors only in the case of boys, whilst VO2max, self-esteem and environment were predictors for girls. The relationships found between MD adherence and other indicators and habits highlight the need to develop promotional strategies from an inter-disciplinary and transversal standpoint. Given the tendency for adolescents to move away from the MD as they age, educational centres and related institutions are advised to promote healthy dietary patterns based on the MD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all students, parents and teachers of the schools who participated in this study.

The study was partially financed by the Institute of Riojan Studies (IER) of the Government of La Rioja through ‘Resolución nº 55/2018, de 9 de julio, de la gerencia del instituto de estudios riojanos para la concesión de ayudas para estudios científicos de temática riojana convocadas para el año 2018-2019.’

All authors were involved in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, literature search and writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions. None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.