Chapter 3 Latinitas et communitas Visionis Willielmi de Langlond

An instant way to tell whether any given Middle English manuscript belongs to the Langland archive is to see whether it steadily incorporates Latin lines and passages of various length into its main English text. It is usually easy to tell, since they are visually emphasized via boxing, rubrication, or change of script to textura. Piers Plowman, of course, is not unique in featuring Latin prominently: Gower's Confessio Amantis does, in a manner quite different from Langland's, and the Clerk's Tale and the Wife of Bath's Prologue are surrounded by Latin glosses in many manuscripts, including Ellesmere and Hengwrt.1 But because those glosses are marginal, they are not printed in the main portions of modern editions, their existence wholly eluding casual readers. Not so the Latin of Piers Plowman, which forces its Latin into its reader's consciousness. This prominence has led to a growing sense that Langland's relationship to Latinate cultures is a mark of his progressive originality. Sarah Stanbury wryly notes the critical trend according to which the poet was “something of a linguistic Robin Hood,” “a folk-hero appropriating Latin texts and distributing them, in English, to the general populace,”2 laying bare ecclesiastical secrets to vernacular readers of the poem as occurs within it as well. Others argue that Langland exploited the radical potential of the Latin itself, which “registers, and indeed is a register marker for, the dissonance and discontinuity” of Piers Plowman.3

While both of these approaches have been very productive, they rely on the extraordinary, downplaying the conventional. The conventional, though – the Bible, Cato, etc. – constitutes the overwhelming majority of Piers Plowman's Latin. As such, most of these tags “are detachable (and might have made their way into the text by way of the margin),” which is what led George Kane not to assign those lines distinctive numbers.4 Much of the Latin that editions print in their main texts does in fact appear in the margins of the manuscripts, especially the OC2 group of B, and F, VA, W, and N2 at various locations in the C tradition.5 The converse is true as well, with about thirty spurious Latin lines, some of which undoubtedly originated as marginal additions, appearing in the main texts of eighteen extant manuscripts.6 It is thus possible that, as with the as an ancre tag discussed in Chapter 2, some of the Latin lines assumed to be Langland's might have come into the main text from the margins, where they recorded early readers' engagement with the poem. A given line's appearance in an entire tradition means only that it was in that version's archetypal text, all three of which were at least two stages of copying removed from the holograph.

The possibility extends to lines extant in more than one version, as Langland might either have welcomed the new appearance of any given item and retained it in the next version, or failed to recognize it was not his own item in the first place. He merely initiated the process, which was simple enough to re-enact. For while not many readers this side of John But could write Langlandian verse with any facility, most anyone – at least, those who had studied grammar and listened to sermons, which I am assuming fits the bulk of Langland's audience, both real and imagined – could come up with an appropriate proverb. That is what margins are for. If Langland did indeed want to encourage his readers' participation in the production of his poem, he could hardly have chosen a better means. So when John Alford objects that Kane's line-numbering policy “devalues” the quotations by implying that they “are less important than numbered quotations, dispensable, perhaps not even authorial,”7 he in fact describes the situation quite well, except that Kane, if uncharacteristically, does not himself scorn this potential intrusion of non-authorial material into Langland's masterpiece.

Such treatment of the poem's multilingualism was a manifestation of the larger reality, not very clear from the received archive, that Latin provided the most immediate and accessible means for the medieval reader's engagement with and participation in Piers Plowman in its manuscript instantiations. We are accustomed to seeing Langland's poem as a triumph of the common tongue, a triumph to which even its treatment of Latin points: “Other languages are fought off; English is liberated and isolated.”8 But it was Piers Plowman's Latinity, precisely because of that language's status as the lingua franca of the literate, that enabled a substantial proportion of its audience most directly to come to terms with its message. This should not be very surprising, but the emphasis on the “English” of the “Middle English era” has kept Latin, precisely because of its dominance, on the outskirts. That dominance is too much even for Ardis Butterfield, otherwise committed to resisting the notion of English's separable character: “An even longer and better book would bring Latin properly into the picture as well, since in a sense this is the most important linguistic perspective of all.”9

This book, too, might be even longer and better if it gave Latin its due, but as it stands this chapter will contribute to Butterfield's project by presenting the evidence for the claim that Latin is how medieval and early modern readers were most likely to engage with Piers Plowman. This material is found on the flyleaves, margins, endpapers, and even the main texts of the poem's manuscripts and early printed editions, places that rarely figure in critical assessments of the poem's Latinity. Critics, interested almost exclusively in the texts that editors rely on and in general willing to grant that whatever is in the archetypal texts must be authorial, have made use only of the main texts, on the whole ignoring the other four of these locations. An emphasis on Langland's originality, and fabrication of an archive in that image, have, paradoxically, obscured one of his most original conceptions: the invitation to contribute to the production of Piers Plowman from the beginning, one that, even if he did not offer it consciously, many of his early readers accepted with relish.

Ashmole 1468, Pseudo-Gluttony, and the quick brown fox

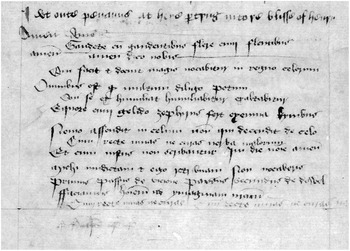

The final page of the Piers Plowman text in Oxford, Bodleian MS Ashmole 1468, a late fifteenth-century copy of the A version, features a contemporary response, or contribution, to the poem's transmission that has barely registered in the Langland archive. The top two lines of Figure 4, “I wt oute penauns . . . / Amen Amen,” conclude the main text, in its scribe's hand; the next, starting “Gaudete cum gaudentibus” is in the new hand.

Figure 4 Latin lines following on from the MS’s Piers Plowman.

Only Walter Skeat has mentioned this item, in his description of the manuscript, but he was not very impressed: “a few Latin quotations are scribbled below, which have occurred in Piers Plowman.”10 His implication that they were written in haste, and unworthy of attention, probably explains the silence that has since greeted the lines. In fact, as this image shows, they are in an attractive Gothic Secretary hand,11 and flow on directly from the main text, as if to be taken as part of it.

The item's contents, too, get short shrift in Skeat's characterization. The “few Latin quotations” in these thirteen lines are in fact fifteen separate quotations copied over seventeen segments, as one, a line from Cato, occurs three times over lines 8 and 13. Two-thirds of the fifteen – six from the New Testament, two from the Old, the Cato item, and a formula – are “quotations, which occur in Piers Plowman,” if that phrase refers to Langland's quotations of other items, with the bulk from A 10–11, the final two passus of the poem.12 If the phrase means quotations of the poem, the figure increases from ten to twelve such quotations, with the addition of the two rubrics of line 11, “Primus passus de vicione Passus secundus de dowel.” The remaining three items appear nowhere in the extant texts of Piers Plowman. The first is in keeping with the bulk of this collection: the second part of line 10, “Non vocaberis,” which opens Isaiah 62:4, “Thou shalt no more be called Forsaken: and thy land shall no more be called Desolate.” The other two, though, could hardly be less appropriate to their context. Line 4, “Omnibus est [notum] quod multum diligo potum,” sounds like something Gluttony might have said in another version of passus 5: “Everyone knows I like many a drink.” This Leonine quip was common – among its homes is below the conclusion of the Piers Plowman text in San Marino, Huntington Library MS Hm 137, fol. 89v – enabling easy sourcing of the missing term notum, necessary for sense and internal rhyme.13 The other non-Langlandian item could not be Gluttony's or anyone else's: “Equore cum gelido Zephirus fert exennia kymbus,” the Latin equivalent of “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,”14 which, too, appears, among many other places, in another Piers Plowman manuscript, BL MS Harley 6041, fol. 96v, in an early sixteenth-century addition beneath the conclusion.15

These three items prevent any easy characterization of the Ashmolean collection as either a simple continuation of the main text or a digest of its best lines. It is akin to the item on which Jacques Derrida focuses his attention in Archive Fever, the “Monologue with Freud” with which Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi concludes his book Freud's Moses: Judaism Terminable and Interminable. Derrida expends most of his energy on the content of this “monologue,” whose implications for the notion of the archive are substantial, but his first observation concerns the very structure of the piece, which is both part of and extraneous to the book proper, a standard history:

In the first place, this fictitious “Monologue” is heterogeneous to the book, in its status, in its project, in its form; it is thus by pure juridical fiction that such a fiction is, in effect, bound in the same book signed by the same author, and that it is classified under eight “scientific” rubrics (nonfictional: neither poetic nor novelistic nor literary) in the bibliographic catalogue whose classical categories are all found at the beginning of the work.16

Likewise does the Ashmolean item present itself as an integral part of what precedes but can succeed only as a fiction: hence its near absence from any description of the book within which it is bound.

The final two quotations in the item, the two rubrics that make up line 11, nicely embody the dilemmas of the poem's “detachable” Latin and of this collection's relationship with the text of Piers Plowman. On the one hand, of the items on this page only two rubrics must have come from the poem; on the other, they might as well keep company with the “quick brown fox” lines so far as the Langland archive goes, given their absence both from Alford's Guide, for they are not “quotations,” and from the main texts of any recent editions, for they are supposedly not Langland's.17 Yet some scholars promote the scheme of rubrics as authentic indicators of major structural significance.18 Since the case cannot be decided on the grounds of the Latin alone, advocates of the rubrics' authenticity must, somewhat perversely, appeal to their very difficulty as evidence for their case. Thus the transitions marked by their appearance in the final two passus of B, says John Burrow, “are so far from obvious that they have even escaped the notice of most modern scholars”; they mark “the deep structure of his poem.”19

Yet Langland's readers did recognize, and mark, such deep structural elements of the poem, and did so even long after its original composition. The table of contents of CUL MS Gg.4.31 (c.1544) divides Piers Plowman into thirty-five chapters, signaled in the main text by the use of capitals.20 “Not surprisingly,” observes Judith Jefferson, these chapter divisions “suggest structural interest. Chapter breaks occur at significant points of transition.” These can be changes of subject matter, or of modes of literary discourse, or of plot development: the chapter break at B 1.79, for instance, is the point at which the Dreamer's “vision suddenly becomes personal (he falls on his knees and asks Holy Church how he may save his soul), while that at 6.253 occurs at a similar juncture, at the point where the criticism of those who are wasters suddenly becomes personal to Piers.”21 To grant the possibility that the rubrics might not be authorial, then, one need only imagine the actions of a single reader of equivalent interest and acumen to those manifested in CUL Gg.4.31, at work on the poem much closer to the moment of its origins.

In remarking that the rubrics mark deep structural transitions inaccessible to all but the poet, Burrow voices a common belief about the role of the Latin tags as well. While they might appear to be afterthoughts intended to provide an authoritative gloss to the English, these quotations are in fact, so John Alford argues, “the matrix out of which the poetry developed,” and the question of their relation to the rest of the poem is “more pertinent than any other to the art of Piers Plowman.”22 This argument presents Langland as “eking out his poem slowly, even tediously, while poring over a variety of commentaries and preacher's aids – and this picture is entirely consistent with the practice of countless of his contemporaries, with the structure of the poem itself, and with the fact that he was a tireless reviser.”23 Following Alford's lead in this respect, the analysis of Langland's Latin over the past decade or so has emphasized its distinctive status over its general milieu: “while Latin quotations in English manuscripts often take the form of marginalia designed to gloss and bolster the authority of what the English text already says,” Fiona Somerset remarks, “Langland's usage is by now understood to be far more complex and varied, and in many cases an integral part of his poem's project.”24

Prime among Somerset's examples is the set piece of the angel's proclamation in the Prologue, “Sum Rex, sum princeps; neutrum fortasse deinceps” etc. (B Prol.132f.), which Traugott Lawler has now even posited as an authentic Langlandian composition.25 A substantial number of tags are incorporated syntactically into the English, or are necessary referents of the English, such as “The sauter sayth in þe psalme of Beati omnes: / Labores manuum tuarum quia manducabis etc.” (A 7.234–4α), or the long quotation from Job and a commentary on it followed by “Yf lewede men knewe this latyn a litel” (C 17.53–4). But complex and varied usage on the whole does not necessitate complexity in every instance, or even in very many of them. However much the extraordinary Latin of Piers Plowman captures the imagination, the fact remains that most of it consists of straightforward quotations that many readers knew very well, and that could be, as it were, re-detached: hence the Ashmolean collection of thirteen tags. This was a simple model that readers could also adopt as their own: hence the Ashmolean addition of three new items to that collection.

The item at the end of Piers Plowman in that manuscript presents one final, even more basic, dilemma: how it is to be incorporated into definitions of the poem. The issue, in sum, is the one on which Derrida focuses with regard to the Freud archive: whether this is a witness to the poem itself, or to the reception of that entity. The first option is not so easily dismissed, for one of the rubrics it cites, and both items of line 9, “Et cum justus non scribantur” and “In [dei] nomine amen,” are absent from the main text of this copy, the pages that attested them having gone missing. Strictly speaking, these lines together constitute an independent witness to Piers Plowman of equal authority to the lines of the main text. It is also possible, if unlikely, that this inscriber was copying from the exemplar behind the Ashmole copy, which would render all the lines from the poem that appear here of equal textual authority to the main poem. Yet this item has never been collated in, cited in, or even explicitly rejected from any edition. It appears in no lists of witnesses, in which, even if they are arbitrarily confined to items of potential textual authority, that is, whose text cannot be dismissed as derivative of another extant witness, the Ashmolean collection would seem to merit inclusion. Since other excerpts, both shorter and later than this one, often show up on lists of the extant manuscripts, as we saw in the Introduction, it must be either the item's Latinity or its proximity to a main text, neither of which has any real bearing on the issue, that has prevented its inclusion.

It is interesting to ponder how criticism would have dealt with these Ashmolean lines had they been in English. Perhaps they would still have been ignored, for being derivative of the main text, or, to be more optimistic, celebrated for being so much more than the collection of nota benes with which readers usually have to be content as markers of reception. Once one does notice them, I have argued, these lines raise some fundamental questions, by themselves accommodating three modes of Latin: the sort seemingly integral to the poem (Cato, St. Paul, etc.); that most likely added by an early reader but generally accepted to be part of the poem (Primus passus de vicione, etc.); and that in turn added by the latest generation of audience, who saw no reason that Pseudo-Gluttony and the quick brown fox could not take their place within the disparate collection of materials known as “the Latin of Piers Plowman.” What Derrida says of Yerushalmi's “Monologue” applies to the list of Latin lines in Ashmole 1468 as well: “this postscript of sorts retrospectively determines what precedes it.”26 It turns Piers Plowman itself into something much different from anything we have known before.

The fullness of time: from the margins into the text

If the Ashmolean inscriber added new items to his collection of Piers Plowman's Latin, others added them to the poem itself. In doing so Langland's readers were following his own example, for they knew the same reservoir of biblical, legal, and aphoristic materials as he did, and could even supply it when the poet himself was content to rely on English versions. One such instance concerns the Donation of Constantine, the apocryphal act that was believed to have ceded the Lateran in Rome to the papacy. This is anathema to Langland (or, at least, to the narrator, Anima in received B, Liberum Arbitrium in C), who tells the famous legend that a sign came from above indicating the travesty of this transference of authority:

In the B tradition's OC2 manuscript group, the lines appear as above, but with the addition, after line 559/222, of hodie venenum est effusum in ecclesiam domini, “today venom is poured forth in the church of the Lord.” This phrase had been what the angel said since at least the thirteenth century; in Langland's era it “is cited in Higden's Polychronicon iv 26 and Gower's Confessio Amantis Book 2, and was favoured by Wycliffe (e.g. Dialogue iv, 18),” as A. V. C. Schmidt observes in his commentary on this passage, citing, of course, the OC2 item as further evidence.27

Langland clearly had this line in mind as well. The received quotation is a very good translation, both literal (hodie, “this day”; venenum, “venym”) and filled out in ways characteristic of Langland's translation practices. Line 560/223 exemplifies his “urge to make clauses with verbs” where the Latin is compressed (here, by the passive construction of est effusum), and 561/224 manifests his “urge to expand and to specify,” since this is only implied in the Latin.28 The only slightly uncharacteristic feature in OC2 is that the Latin appears before the translation, rather than after as is usually the case; but as we will see in a moment there are material reasons for that location. The same thing occurs later in the poem as well, at B 16.93-5, about the fullness of time when Jesus will take on his ministry,29 presented here in the text of C2, CUL MS Ll.4.14:

This belief that Christ would be born exactly 5,199 years after the Creation frequently initiated brief chronologies of the world that were produced through many centuries and in many regions.30 The addition, while less intimately related to the passage than the other OC2 addition is to the Donation of Constantine, still fits its new context perfectly; likewise the lines' Leonine hexametrical form, which Langland favored as well. Had either of these OC2 additions been inscribed into the margins of the exemplar behind the B archetype and taken up into the main text of that copy, no one would have doubted its integrity.

These two instances demonstrate that the Latin additions to the manuscripts were not necessarily the insertions of scribes as they wrote out their copies. Rather, these additions moved into the main text, where they appear in C2, from the margins, their home in O (Oxford, Oriel College MS 79). While MS O often places its Latin in the left or right margin, the angel's cry is the only such tag inscribed above its folio's top ruling (fol. 67v), while the lines on the fullness of time are the only ones just below their folio's final ruling and above its bottom edge (fol. 69r).31 These tags must thus have been in the equivalent margins of the group's mutual common ancestor, whose mise en page the O scribe reproduced faithfully while his C2 peer decided instead to normalize his text.32 Some manuscripts of both Gower's Confessio Amantis and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales likewise bring Latin marginalia into the main text.33 In those cases, where the Latin goes on for many lines and, in the case of Gower, serves as commentary on the English text, the practice was very disruptive. But Langland, always much more economical in his own treatment of Latinate glossing, enabled those who followed his example to go unnoticed.

If the reader of the OC2 exemplar could provide the Latin that lay behind the Poison of Possession lines, so could a reader of any of the three archetypal manuscripts. This means that in theory any detachable Latin in received A, B, or C could have originated as a reader's gloss. Take, for instance, Haukyn's rationalization of his sin-stained coat at the beginning of B passus 14, which Alford calls “Langland's most sustained, and perhaps most successful, use of the method” of concordance.34 The proof that this could be non-authorial is simple: we need only remove the Latin to see if the passage works without it.

Haukyn's appeal to his possession of a wife could easily have prompted a reader of a manuscript to add to the holograph's margins a New Testament line, Uxorem duxi & ideo non possum venire (Luke 14:20). The scribe who took this copy as his exemplar, like the C2 scribe, would then have incorporated the Latin into his text after line 3, ensuring its appearance in all the B copies. An even more sophisticated reader might have recognized that the parable from which this line comes “provides the theme for Passus 14,” as Alford points out35 – all the more reason, then, to add the pertinent lines from the gospel reading itself, as well as those from the commentaries built up around it. Such speculation is not to deny the force of Alford's approach, or of any argument that takes detachable lines to be integral to the poem. On the contrary, it is to acknowledge that Langland wrote for an audience conversant with this procedure, who thus could fill in the very Latin lines that inspired the poet in the first place, which is just what occurred in the OC2 group.

Unidentified scraps

The Latin of the received versions most likely to have originated as marginal glosses is not of the character found in Haukyn's lines, even if we cannot rule out that possibility. It is, rather, the sort that features what Helen Barr calls the most characteristic appearance of the quotations: “their standing apart from the actual verse form such that they could be written at the side of the English as marginal glosses.”36 Since most of the criticism of Piers Plowman's Latin focuses on the extraordinary, it will be worth spending a few moments to get a sense of this material's character and provenance. The fullest treatment is John Alford's Guide to the Quotations, but there remain what he calls “unidentified scraps,”37 whose elusiveness might seem to suggest origins in milieux different from the grammatical, legal, and theological ones Alford identifies as most important. It has thus even been suggested that Langland himself composed some of this material. Yet the quotations for which I will now offer new or corrected identifications, like so much of the rest of Piers Plowman's Latin, were part of a common storehouse of aphorisms emanating from these and closely related modes of discourse. The fascination with the poet's unique and innovative qualities has obscured the presence at those very locations of the opposite qualities, the ones in which the poem could belong to, or include contributions by, any educated reader.

First is a line from one of the most delightful passages unique to the A version, quoted at the beginning of Chapter 2, Wit's invective against those restless and reckless souls who futilely wander about among the religious orders:

Skeat, querying the origin of this tag, said “this is used to express that a man who is Jack of all trades is master of none.”38 His query would not be answered until Teresa Tavormina finally pointed to Higden's very close remark, “Immo nonnulli omne genus circueuntes in nullo genere sunt, omnem ordinem attemptantes nullius ordinis sunt,” as the closest analogue, leading to at least one claim that Higden informed some central aspects of English identity, in this case those of “recklessness” and elusive identity.39

In fact there is a direct source for both Piers Plowman and Higden: a reportatio of Peter of Auvergne's Questions on Aristotle's de Caelo (c.1277–89), in the discussion of “whether the first mover moves the primum mobile, i.e., whether the first orb is moved immediately by the first mover or whether it has a proper mover besides the first mover.”40 Following the typical structure of the scholastic question, Peter first presents arguments in favor of the position with which he will disagree. One of the two arguments to be rejected is home to our item:

Item principium universale non appropriatur alcui enti, quia quod circuit omne genus in nullo genere est; sed primum principium est causa universalis, efficiens principium omnium.41

The universal principle is not particularly related to a particular being, because whatever encompasses every origin is in no origin; but the first principle is the universal cause, the efficient principle of everything.

Peter responds by saying that this argument does no more than state the obvious truth that each orb has its own efficient cause, its own proper mover. But, he objects, “the first mover is particularly related to the primum mobile. It moves the first orb in ratione amati et desiderati with the daily motion from east to west. Consequently, it moves all inferior orbs, and in this sense it is an efficient cause as well.”42 Whoever was responsible for the tag in Wit's lines, whether Langland or an early reader, must have had an innate interest in such material, given that this section of Piers Plowman relies so heavily on scholastic theology. If Langland was familiar with Peter of Auvergne's Questions, he would have known that Wit's tag ends up on the losing side of the debate. Dame Study's wrathful reaction to her husband's speech (A 11.1f.) would no longer appear to be the first indication of its dubious nature. But the tag's presence in the A version itself, as well as its obvious influence on Higden, shows that it thrived quite apart from its original context.

Michael Calabrese judges “Sunt infelices quia matres sunt meretrices,” “They are accursed, for their mothers are whores” (C 3.190α), in Conscience's invective against priests' keeping of mistresses, to be “one of the most striking additions to C of any kind”: hardly a scrap.43 Also apt is Calabrese's observation that “the line could very well be a scribal gloss inserted into the text as if it were a line of poetry, or it could have been a line of text that became a scribal gloss, as in [MS] F.”44 This Leonine tag has resisted identification because it is separated, so far as I am aware only in Piers Plowman, from the companion with which it elsewhere appears: “Presbiteri nati non possunt esse beati, / Sunt infelices quia matres sunt meretrices.”45 Another English collection of proverbs, in Oxford, Bodleian MS Rawlinson D 328, cites the first of these lines alone, together with translation: “Presbiteri nati non possunt esse beati. / A preste-ys chyld schall never be blessyd.”46 The marginal annotation of C 3.189 in Huntington MS Hm 143, “notate prestes gurles” (fol. 13r),47 is closer linguistically to the maxim's presbiteri nati than to the poem's more belabored reference to Meed's maintenance of “prestes . . . to hold lemmanes . . . And bringeth forth barnes aзenes forbodene lawes” (C 3.188–90). It might well be that, as Calabrese suggests, an earlier annotator had decided that Langland should have inserted this well-known misogynist maxim instead of going on and on with this wordy allegory.

Later in C, Imagynatif expounds the gifts of grace and kind wit, saying in Latin that “the phenomena of this world are subject to the configurations of the heavens”:

This tag, too, eluded the efforts of Skeat, Alford, Pearsall, and Schmidt, the last of whom, calling it “a quotation (if such it is) of untraced origin,” suggests that it might be Langland's own.48 In fact, in 2002 Stella Pates, having recognized it in the copy of Pseudo-Ptolemy's Centiloquium included as part of Oxford, Bodleian MS Bodley 463, became the first modern reader of Piers Plowman to identify the quotation.49 What she does not say is that the Centiloquium was a sort of Disticha Catonis for anyone interested in cosmology. Arabic sources of the twelfth century provide the earliest evidence for its existence, and over a hundred and fifty Latin manuscripts are extant. This was among its more popular aphorisms, making its way into such texts as Dante's De Situ et Forma Aque et Terre and Constantine of Pisa's Liber Secretorum Alchemie.50

Finally, and most famously, Pacientes vincunt: if Langland's poem has a motto, this, “the patient conquer,” is it. This tag appears more often than any other Latin clause, six times over three passus in the B version (13.135α; 13.171α; 14.33α; 14.54 [= C 15.253]; 15.268; 15.598α; also C 15.137, 15.156), and its lesson is in operation even where not cited: as Stephen Barney observes, Langland's Jesus conquers the devil by hiding and suffering in B passus 18.51 By no one's standard could this be considered scrappy: yet it is exactly like the items identified above in resisting the pall of uniqueness with which modern critics have imbued it. “Scrappiness” is an index not of these Latin lines' character but of our knowledge. While “patientia vincit omnia” is proverbial in the singular, Alford says that Langland “offers the only example in the plural,” a statement that still holds.52 Yet the Latin plural appears as well in a source that Alford has already identified as a likely major source for Langland's quotations about the rich and poor in passus 14, among the homes of pacientes vincunt itself. This is John Bromyard's Summa Praedicantium, under the heading “humilitas”:

Opus quod nobis incumbit est bellare contra diabolum: quia vero superbus est contra eum non pugnat, sed vero sub eo militat, nunquam eum vincit. Qui vero humilitate et pacientia contra eum pugnant, vincunt. Sic ergo dum pacientes vincunt, “de sua virtute gloriantes humilias.”53

The work incumbent on us is to war against the devil: because in truth he who is proud does not fight him, but serves as a soldier under him, and never defeats him. In truth those who fight him with patience and humility conquer. Thus, while the patient conquer, “thou humblest them that glory in their own strength”

Alford deems it very likely that “the poet drew upon the [biblical] commentaries and upon some such work as Bromyard's (if not the Summa Praedicantium itself ) for the majority of his quotations.”54 Pacientes vincunt cements the case.

The tags and lines we have been discussing originate from wildly disparate milieux, ranging from Parisian scholastic lectures of the 1270s to the witty misogyny that soils flyleaves and proverb collections. Many of them could have come into Piers Plowman via grammatical texts, a notion that has recently been promoted as the driving force of Langland's Latinity;55 but each argument in favor of that milieu equally supports the artes praedicandi in which we find Bromyard as primary conduit: grammar texts and sermons share a substantial proportion of their respective characteristics, and preachers, after all, had once been schoolboys. Christopher Cannon adduces Langland's “habit of repeating quotations, often with very long stretches of the poem intervening between one citation and the next” as evidence for the Latin's schoolroom origins, but this characteristic led A. C. Spearing to note Langland's indebtedness to the methods of digressio and descriptio emphasized in medieval English artes praedicandi.56 Medieval English sermons feature Latin–English lines that are alliterative, punning, and witty, such as “non vultu ficto and ficle verbis sed pleno corde” and “diu laboravit graviter in gravynge istorum signorum.”57 While Cannon seems to imply that hexameter Leonines are strictly the provenance of grammar texts, in fact they pervade sermons as well.58 Likewise, “the use of proverb collections as reference books for preachers is well documented.”59 And this Latin was sophisticated in ways that would have attracted Langland and his readers: “often a biblical figura invoked in the sermon text does not merely look back at the doctrinal matter to be proven but at the same time points forward and provides the ground for further amplification,” remarks Siegfried Wenzel, who concludes: “To find an appropriate biblical figura . . . and weave it meaningfully into the verbal texture of the sermon surely requires skill and intelligence.”60

Yet replacing the schoolroom with the pulpit as immediate origin of Piers Plowman's tags merely replicates the problem. This material was universal. The aphoristic, moralistic sorts of Latin tags found throughout Piers Plowman provided both the themes and content of sermons, of grammatical instruction, and of poetic composition, so there is little point attempting to determine their precise milieux. Scraps or not, these items have substantial implications for the fabrication of the Langland archive, calling into question the possibility of attributing some of the most important lines of its foundational entity, Piers Plowman, to its namesake.

Excerpting Piers Plowman, c.1450–1600

The converse of the phenomena discussed over the previous few pages is epitomized in Ashmole 1468: the excerption of Piers Plowman in ways that emphasize its Latinity. The opening English lines (“In a somur sesoun . . . ”) show up at the end of the C-version text in Huntington MS Hm 143 and in National Archives E101/516/9,61 and a few prophetic passages make their way into compilations in the sixteenth century, as Chapter 4 will show. Yet it is striking to realize that all other known instances of excerption present the poem's Latin either on its own or wholly subordinate its English to the Latin. This applies even to the single other instance of a standalone English excerpt from Piers Plowman, which occurs in a quire of flyleaves added to the beginning of Bodleian MS Bodley 851 by one “Dodsthorp,” the final compiler of the manuscript. “Chastite wihtout charite brennit in helle” appears here (fol. 3r), and, while definitely from Piers Plowman, is almost certainly not from the Z version found later in the volume, originating as either A 1.162 or C 1.184.62 Yet this is but one of “over seventy items, a few English or French but most Latin” in these flyleaves' pages, says A. G. Rigg: “the mixture is typical of fly-leaf poetry of the period: there are items of local interest, riddles, proverbs, literary extracts, drinking and begging poems, etc.”63 The full-scale Piers Plowman in this manuscript was already bedfellows with Walter Map, John of Bridlington, and other Latin materials by the time it reached Dodsthorp, who in turn inscribed its English fully into that Latinate world, perhaps not even realizing it was from Piers Plowman at all.

The longest relatively brief excerpt of Piers Plowman, too, accentuates the Latinate. “Nota bene de libero arbitrio secundum Augustinium & Yisidorum”: thus writes John Cok on the final blank folio (p. 210) of Cambridge, Gonville and Caius MS 669*/646, proceeding to inscribe Piers Plowman C 16.182–201α. “We might pass over as insignificant this scrap” – that word again – “of twenty lines on Free Will which he appends to his anthology,” were it not for the information it provides, writes George Russell: “We know that Cok was a cleric attached to St Bartholomew's Hospital in the first half of the fifteenth century, and this fragment tells us that he had access to a Piers Plowman manuscript and remembered, or wished to register, the present passage.”64 Textual affiliations even indicate that he consulted CUL MS Ff.5.35.65 But even though Cok was busy writing the Englished Richard Rolle into this volume, he showed comparatively little interest in the vernacular of Piers Plowman. In the sixteen English lines he writes, Liberum Arbitrium offers the Latin names for English concepts associated with himself: Anima, Animus, Memoria, sensus, Amor. Cok departs from Ff.5.35 in replacing the final three English lines, 199–201, with a single one translating 199, “Secundum augustinum & ysidorem & quemlibet eorum,” followed by the culminating self-definition, 201α, which occupies some five lines in Russell and Kane.

One could hardly do more to turn a triumph of vernacular poetry into a repository of scholastic Latinity. Yet Cok did just that: for though it has gone all but unnoticed, his first inscription of the poem into his volume occurs much earlier in the book, in the bottom margin of p. 87, when he provides, as a gloss on the discussion of poverty in the Englishing of Rolle called “Amore Langueo” there copied, the definition of poverty that we now call Piers Plowman C 16.116:

paupertas est odibile bonum, remocio curarum, possessio sine calumpnia, donum dei, sanitatis mater, absque solicitudine semita, sapiencie temperatrix, negocium sine dampno, incerta fortuna, absque sollicitudine felicitas &c.66

Cok's omission of the phrase “quod pacience” after paupertas, which occurs in all other witnesses to the passage, underscores the extent to which he subordinated the English of Langland's poem to its Latin. Had he not included the following excerpt from the same passus a few pages on, no one would have suspected this is from Piers Plowman at all.

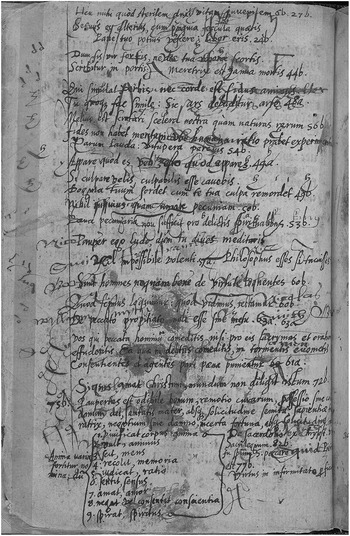

Cok was joined by early seventeenth-century readers like Richard James and Gerard Langbaine in writing out entire passages from Piers Plowman that are included in recent lists of its manuscripts.67 At least one peer of these figures might have received equivalent attention were it not for his work's character (Latinate, a collection of single lines) and location (on the blank page facing the first page of text in a Cr2 now at Yale). This italic hand inscribes some twenty-four items together with the folio or folios on which they appear, beginning: “Heu mihi quod sterilem duxi vitam juvenilem 6b. 27b.”68 This reader knew such material well enough to substitute quod for the Crowley text's quia in that first quotation (1.141α and 5.440α), to enumerate the definitions of Anima that so interested his predecessor John Cok (15.39α), and to attribute 15.343α, “De sacerdotio ex Chrystostom: Sacrilegium 82b,” rather than quote the original Quia sacrilegium est res pauperum.

This annotator exhibits no interest in Piers Plowman as either a prophecy of the Reformation or a defense of the old ways, as either a populist site in which Latin texts are distributed to an English readership or a proponent of radical Latin. It was instead, as a glance at Figure 5 reveals, more or less the same as it was for the Ashmolean commentator, the OC2 contributor, John Cok, and many others whose approach has not had much of an impact on studies of the poem's production and reception. This was a work in which the poet's individual vision was subordinate to a communal conversation, one most eloquently expressed in Latin. The extent to which this reader saw Piers Plowman as Visio Willielmi de Langlond is apparent from his addition of a small number of Latin marginal and interlinear notes in the main text, such as Insomnium Pierii beside “I slombred into a sleping, it swyзed so mery” (sig. A.ir); and the interlinear gloss possent for “they moote” (sig. L.iiiv).

Figure 5 Latin lines from Piers Plowman transcribed in a Crowley.

With the possible exception of Cok's excerpt of the line on poverty, all of the passages considered in this section could only have come from Piers Plowman. In concluding this brief history of excerpting Piers Plowman, though, we come up against the problem that bedeviled the earlier discussion of the communal character of so much of the poem's Latin. For pacientes vincunt appears elsewhere than in John Bromyard and Langland's poem: it is among the Latin glosses in the Canterbury Tales now in BL MS Egerton 2864 (c.1450–75), fol. 155v, next to the Franklin's explanation of why patience is so high a virtue: “For it venquissheth alle thes clerkes seyn” (774). Joanne Rice's notes in The Riverside Chaucer mention the Latin phrase's appearance in Piers Plowman, but since her focus is on Chaucer's own poetry she does not go so far as to cite it as the annotator's source.69 Yet it is clear that he got it from somewhere: he uses the margins to inscribe the authorities behind Chaucer's poetry, not to innovate or comment. While Bromyard or another lost or unknown source is a possibility, Langland is easily the best candidate, though no one has ever said as much. Should this be added to any complete list of witnesses to Piers Plowman? On the one hand, of course; on the other, of course not.

That is to say, while its source is almost certainly Piers Plowman its inclusion in any such list would need to come with an asterisk, since the phrase is not original to Langland. But that is already the case for any number of items whose inclusion makes one wonder about the exclusion of, say, the Ashmole and Beinecke lists of Latin lines. There are two problems, then: the local one of the prominence of proverbial and biblical Latin throughout his poem, and the broader one of the very definition of “Piers Plowman” and what counts as a witness. If the question of the quotations' relationship to the rest of the poem, to its definition and identity, is more pertinent than any other to the art of Piers Plowman, the assumption that Langland was necessarily responsible for all the detachable Latin needs to be abandoned: the Langland archive, given the centrality of Latin to its constitution, should, strictly speaking, be the Langland-and-others archive. Still more pressing is the need for an acknowledgment of the reality that the poem was for much of its audience primarily a repository of Latinate learning, whether scholastic and learned or aphoristic and populist, even its English aphoristic lines occurring in such a context. The classroom, the parish priest's desk, the cleric in the local hospital, the later fifteenth-century annotator of the Franklin's Tale: these, more than the lollers or rebels like John But or celebrity scribes like Adam Pinkhurst and John Marchaunt, are at the heart of the generation of the Langland archive, their beloved poem not so much a brilliant poet's English vision as a space not found elsewhere in the canon of major medieval English poetry, in which unidentified scraps share the glory with Conscience's quest for Piers the Plowman.