Scholars have seen both figural supports and non-representational struts as distinctive devices of Roman stoneworkers. Contrary to this expectation, however, supports and struts are recorded in Greek sculpture from the sixth century bc. They also appear in many Roman statues for which we have no Greek antecedents.

The body of surviving original Greek marble sculpture from the classical period includes a limited number of freestanding statues, vastly outnumbered by reliefs and pedimental figures, which could be fixed to the tympanon wall by means of tenons or dowels.Footnote 1 Occasionally, struts appear also in pedimental compositions, where multiple figures had to be fastened to each other or outstretched limbs secured to the main figure. The first arrangement is found in the symmetrical side groups from the late fifth-century bc pediment of the temple of Marasà at Lokroi. Here, an abundance of tiny structural supports, which were not visible to the viewer on the ground, connected the figures of each group.Footnote 2 Elsewhere, struts supported outstretched limbs.Footnote 3 More often, however, expansive positions were achieved by skilful management of carved limbs and garments. This is the case with one of the figures from the Amazonomachy pediment of the Temple of Apollo Sosianus in Rome, considered to be a Greek original from the second half of the fifth century bc.Footnote 4 The best preserved sculpture of this composition is a forward-leaning statue of Theseus whose advanced left leg is supported by a piece of cloth sliding from his thigh.

Notwithstanding the limited samples available for examination, struts seem to have been a familiar tactic for Greek stone carvers of the archaic and classical periods.Footnote 5 Although struts only became a ubiquitous feature of stone sculpture from the first century bc, their use in bracing complex compositions and limbs detached from the core has a long tradition in the Greek sculpture.

Fastening Movement

One type of support in particular seems to have emerged in the late archaic period and remained in use ever since; from the early fifth century bc large supports began to be incorporated into freestanding equestrian marble statues.Footnote 6 Additionally, archaic kouroi often include struts. Unlike most later Hellenistic and Roman statues, no kouroi have struts between their legs to reinforce the calves. Instead, struts are used to fix the free-cut arms to the body. A distinctive evolution in the shape of the struts between clenched hands and body accompanies the progression towards less rigid postures.Footnote 7

Earlier Attic kouroi from the turn of the sixth century bc, such as the so-called kouros of the Sacred Gate or the slightly later New York kouros, occasionally display narrow segments of stone left in place between hand and thigh. The Sounion kouros, discovered in 1906 in a deep pit near the temple of Poseidon at Sounion and dating to ca. 600–590 bc, also has its arms slightly detached from the body between armpit and hand, but these are fastened to the upper thighs by narrow screens of stone.Footnote 8 Later kouroi, instead, have arms that stand almost free from the armpits to the wrists. Connectors are made often in the shape of short bars, similar in both function and treatment to the ubiquitous ‘Roman’ struts. The statue of a youth in Parian marble from the mature archaic period, found at Attic Myrrhinous (modern Merenda) together with the Phrasikleia kore, preserves traces of two short, thin struts between hips and palms.Footnote 9

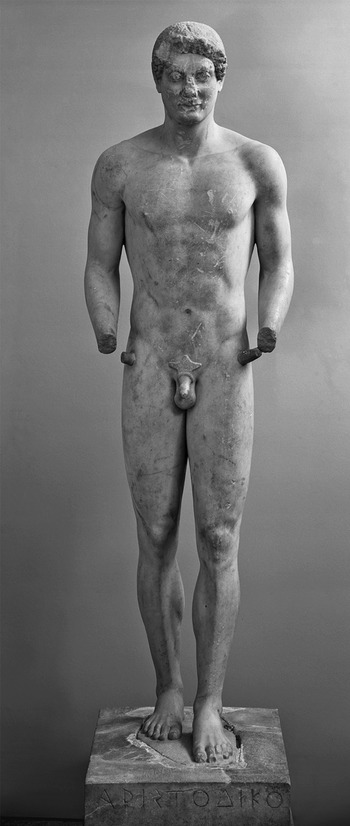

Two semi-cylindrical struts connected the upper thighs to the now missing hands of the Aristodikos kouros, which epitomises the transition from late archaic to early classical sculpture. This element highlights the dynamic movement of the youth and the novelty of his pose (Fig. 12).Footnote 10 The plasticity of the muscles and the movement of the arms, bent at the elbows, as well as the hairstyle of short shell-like curly locks, place this statue, which was executed in Parian marble and found in the Attic interior, at the end of the kouroi series in the years around 500 bc. The next phase in the history of struts is illustrated by the marble statue from the Athenian Acropolis known as the Kritios Boy, which seems to embody the stylistic transformation of freestanding statuary in the first quarter of the fifth century bc. Although smaller than life-size, this statue employed struts in the form of oval bridges to support the movement of the youth’s arms.Footnote 11

Figure 12 Aristodikos kouros, ca. 510–500 bc. Parian marble. H. 198 cm. Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 3938

The Invention of Leaning Bodies

The use of struts and supports remains fairly marginal throughout the fifth century bc. Most freestanding marble statues seem not have required any external support, relying instead on the arrangement of limbs and garments alone. Nonetheless, attributes with a supporting function became commonplace. For example, Heracles’ club and Asclepius’ rod became essential elements of their iconography. The image of Aphrodite, too, shows a significant evolution during the last decades of the fifth century. This resulted in a broader choice of designs, such as leaning poses that relied on figural supports.Footnote 12

In a limited number of cases, the prominent position and structural function of supports have raised questions about the narratives and the visual impact of compositions initiated in bronze or other materials lighter than stone. The Wounded Amazon of the so-called Sciarra-Berlin-Lansdowne type, which is known from multiple Roman marble versions of the first and second centuries ad, is a good example.Footnote 13 The statues in this replica series, which are thought to derive from a bronze original from the third quarter of the fifth century bc, depend on a support for both their balance and the arrangement of limbs.Footnote 14 Exhausted and wounded under her right breast, the mythical warrior rests her left elbow on a post. This support enables her to shift her weight to the right leg, while her right hand is raised to her head as if about to faint. Baffled by the prominence of this support, scholars occasionally suggested a later dating of the prototype to the Hellenistic or Augustan age, which seemed more compatible with this ‘virtually unnecessary’ implement.Footnote 15 Others, however, have stressed the narrative role of the pillar and argued that, while stabilising the composition, it may represent a boundary marker of the sanctuary of Artemis where the wounded warrior sought shelter.Footnote 16 As a pars pro toto, the pillar sets the character in its mythological context. The Varvakeion Athena statuette, regarded as the most faithful – or rather the only complete – surviving copy after the chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos erected for the Parthenon has posed similar questions.Footnote 17 Athena extends her right arm forward, supported by a column. A Nike stands in her palm, about to take off. Although scholars have often argued that a support was necessary to sustain the Nike of the statue created by Phidias, others consider such a static solution unlikely to originate in a fifth-century bc Greek sculpture and attribute the addition to the Roman copyist.Footnote 18

Figural supports seem to have represented a meaningful yet marginal phenomenon in Greek freestanding sculpture of the fifth century bc, and the use of non-figural struts remained exceptional.Footnote 19

Beginning in the fourth century bc, the work of Praxiteles seems to have initiated a new phase in the development of struts. In a number of types attributed to this prolific Athenian sculptor, supports are integral in the construction of the piece and its visual effect. This compositional choice, as scholars have often remarked, goes hand in hand with a new conception of the human figure, which now relied largely on external elements for balance. Among the types attributed to Praxiteles, which are known from multiple Roman copies, it seems that both figures initiated in bronze, such as the so-called Apollo Sauroctonos or Lizard-Slayer, and sculptures originally carved in marble, like the Cnidian Aphrodite, were equipped with prominent supports to match the human figure.Footnote 20

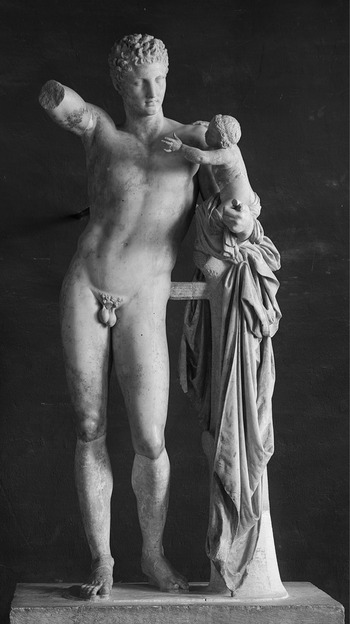

Exceptionally relevant to our argument is the group of Hermes and the infant Dionysus, which was found in 1877 in the ruins of the Heraion at Olympia and whose attribution to Praxiteles has been the subject of fierce controversy among art historians ever since (Fig. 13).Footnote 21 The figure’s weight rests on his right leg, while his left foot touches the ground lightly, in an off-balanced stance which is made possible by a bulky support on his left side. Based on a remark by the second-century Greek traveller Pausanias, who mentions a ‘marble Hermes carrying the baby Dionysus’ by Praxiteles in the Temple of Hera, it has been conjectured that this may be the original statue carved by the Greek sculptor.Footnote 22 The prominence of the support and, especially, the presence of a rectilinear bar-like strut that connects the polished body of the god to the massive trunk at his side, have however prompted widespread rejection of this attribution in favour of a much later dating as a copy of Praxiteles’ lost original.Footnote 23

Figure 13 Statue of Hermes with infant Dionysus. Marble. H. 215 cm. The statue has either been considered an original carved by Praxiteles of the fourth century BC or a copy made in the late Hellenistic or Roman period. Olympia, Archaeological Museum

Supplementing the Legs

The argument that a strut between hip and tree trunk would be ‘offensive to the aesthetic sense of a fourth-century Hellenic sculptor’ conflicts with other, more securely dated evidence from the same period.Footnote 24 Although it remains difficult to determine with certainty whether struts connecting the trunk of a human figure to outstretched limbs or attributes were in fact viable options for Greek sculptors of the fifth and fourth century, one particular type of non-figural support seems to have enjoyed some success in this period of Greek art. Both the Kallithea monument now at the Piraeus Museum and the Daochos dedication at Delphi, two family monuments erected in the second half of the fourth century, attest to the use of vertical struts located behind statues.

Vertical struts are an important feature of the Daochos monument at Delphi.Footnote 25 The ensemble consisted of a long, rectangular base, on which nine statues stood in a row, portraying the donor, his son and ancestors. An inscription naming the individuals represented appears on the pedestal. Six generations of the family were included, among which two ancestors who had won crowns in the Pythian Games and were therefore directly linked to the sanctuary at Delphi.Footnote 26 Moving from right to left the group depicts the progenitor Aknonios and his three sons, Agias, Telemachos, and Agelaos, followed by the offspring of Agias in generational order: Daochos I, Sisyphos I, the donor Daochos II, and his own son Sisyphos II at the left end.

Six figures survive in their entirety or as substantial fragments. A pair of sandal-clad feet is the only surviving element of the final statue, the donor himself, Daochos II.Footnote 27 All of these figures have prominent vertical figural or non-figural supports.Footnote 28 The right lower leg of the two athlete brothers, Agias and Agelaos, is augmented by a vertical mass of stone with a coarse and irregularly picked surface. Both the progenitor Aknonios and his grandson Daochos I have almost identical pillar-like vertical supports running from the plinth to the hem of their heavy chlamys (Fig. 14). A thin vertical support, almost oval in section, is placed behind the left foot and calf of Daochos II. The statues of Sisyphos I and II, instead, are both equipped with figural supports, a tree stump and a herm respectively.Footnote 29 The support plays a minor role in the composition of Sisyphos I and allows the figure, dressed in a short tunic, to stand almost fully upright. In contrast, a markedly off-balance stance was chosen for Sisyphos II, requiring a support in the form of a herm. The presence in the same group of figural and non-figural supports, of different forms and in different relationships to the human body, has sometimes been seen as an indication of different sculptors’ hands.Footnote 30

Figure 14 Statue of Aknonios from the so-called Daochos monument, seen from the left side. Marble. H. 180 cm. Delphi, Archaeological Museum

The Kallithea monument offers comparable evidence.Footnote 31 Two of the three figures included in its imposing architectural frame are supplemented by sturdy pillar-like supports along their leg that are similar to those of the Daochos group. Due to the placement of the statues on a high platform, however, these struts must have remained almost invisible to the viewer below. As plain, squared blocks of stone, such struts properly belong to the category of non-figural supports, unrelated to the subject and content of the composition. Although their similarity to the much-discussed strut between body and tree-trunk support of the Hermes at Olympia is obvious, in terms of both abstraction and non-involvement in the narrative, their visual effect is radically different, placed as they are behind the legs or partly hidden behind the folds of the heavy drapery.Footnote 32

The Daochos and Kallithea monuments demonstrate that in the late fourth century bc a variety of supports and struts was used to meet the structural needs of a composition initiated in marble. In particular, pillar-like struts behind or beside the foot and calf of a freestanding figure seem to be a successful invention of this period, as both the Kallithea monument and the Daochos dedication attest, as well as a handful other isolated works.Footnote 33 That similar supports occur in similarly dressed (or undressed) figures indicates that the choice followed coherent formal criteria, at least within the same workshop or in the same monument.

The Emergence of Struts

By the late Hellenistic period supports and struts were widely used elements of freestanding marble figures. The set of large-scale marble statuary from Delos from the late second and early first centuries bc illustrates this evolution in technique and taste.Footnote 34 Two of the best-known specimens of Delian statuary from the turn of the second and first centuries bc – the group of Aphrodite, Pan, and Eros from the Hall of the Poseidoniast known as the Slipper-Slapper group (Pantoffelgruppe) and the male portrait known as the pseudo athlete – famously include prominent stone connectors. In the Slipper-Slapper group a large strut links the goddess’ left thigh to Pan’s right leg. This element is carefully rounded and contrasts strongly with the thick wool that covers Pan’s legs.Footnote 35 The pseudo athlete displays a striking number of more or less evident supports, in addition to the unusually large tree trunk behind the figure’s right leg.Footnote 36 Struts are located between the legs and between the left hand and thigh, while short branches connect the massive tree trunk to the falling edge of the cloak.

It is in this context that we should examine the statuary recovered from a shipwreck off the islet of Antikythera, south of the Peloponnese. It is generally believed that the ship had sailed towards Italy from the eastern Mediterranean and sunk off Antikythera’s northeast coast at some point in the second quarter of the first century bc. The marble statuary carried by the vessel seems to have been produced at the very beginning of this century, perhaps in Delos.Footnote 37 The evidence from Antikythera confirms that all the main types of struts employed by Roman marble carvers were already a common feature of late Hellenistic sculptures made in Greece. From the point of view of sculptural technique, the most relevant feature is the variety of bulky quadrilateral struts that are attached to several human figures and connect the figure to its base or the outstretched limbs to the core.Footnote 38

Whereas some struts might have functioned as precautions for shipping, other conspicuous props are an integral part of the composition. A primary example is the statue of a nude boy in Parian marble, bent over with his head raised, often interpreted as a pancratiast or wrestler just before the match (Fig. 15).Footnote 39 The gap between the thumb and forefinger is bridged by a very thin strut. More visible in the composition are the large, quadrilateral struts that almost create a cobweb around the human figure. These comprise a huge shaft, now largely corroded by sea water, joining the plinth to the statue’s left thigh, a bar between the right elbow and thigh, as well as a third such squared, roughly picketed strut beneath the right knee. Clearly, this abundance of supports was required by the peculiar stance of the young athlete whose off-centre, crouching pose required additional measures for stability. If such struts were instrumental to the general scope of the composition, their visual share must have been acknowledged and accepted. Although slightly different solutions could have been devised that would limit the need for external support, the sculptor who created this statue and his prospective customers evidently valued the effectiveness and impact of the youth’s stance more than they disapproved of the related shortcomings in stability and balance.

Figure 15 Statue of a boy from the shipwreck of Antikythera, early first century bc. Parian marble. H. 111.5 cm with the plinth. Athens, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 2773

Sometimes, the presence of large struts has been, on the one hand, fundamental to the reconstruction of a marble composition and, on the other hand, an obstacle to accurate dating. An intricate group of Artemis and Iphigenia, found in Rome in the area of the Horti Sallustiani and now at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, is a perfect case in point. What remains of the group, reconstructed in the early twentieth century by Franz Studniczka thanks to its many struts, are actually the torsos of two women and the fragmentary head of a deer.Footnote 40 The rear torso has been recognised as that of the goddess Artemis. In front of her, the figure of Iphigenia is preserved as a torso of a semi-recumbent young woman, whose chiton is ripped aside exposing her right breast, hips, and right leg. Dating has ranged from the late fourth century bc to the Roman imperial period. Some have considered the group to be either a late classical or Hellenistic original; others think instead that it is a Roman copy after a lost bronze composition made at some point between the late fourth and the mid-first century bc.Footnote 41 One of the reasons for a later dating of the Copenhagen statues has been the number and prominence of their struts, thought to be incompatible with a work of Greek art.Footnote 42 But the freestanding Hellenistic statuary from Delos and the marble statues recovered from the shipwreck of Antikythera constitute a reliable body of evidence about the widespread use of both figural and non-figural supports by late Hellenistic marble carvers in Greece. Although this can hardly be accepted as a decisive indication that the Artemis and Iphigenia group dates to the mid to late Hellenistic period, the possibility of framing the technical device of struts within a larger and long-term development in both workshops’ practices and, evidently, current taste, allows us to rule out one major argument that has so far prevented scholars from focusing on other, more reliable stylistic features.

Struts were employed by the artists who created some of the most striking archaic kouroi and continued to be used throughout the classical period in order to secure slightly outstretched limbs or the projecting parts of a composition. It is in the late fourth century that both figural and non-figural supports became fundamental and often optically prominent features. By the time the Slipper-Slapper group and the pseudo athlete had been installed in Delos, struts seem to have become a popular and accepted expedient to guarantee the stability and integrity of freestanding marble statues. Struts, in themselves, can hardly be presented as a Roman invention. Rather, stone carvers of the Roman era may have adopted the concept and practice of structural supports from the Greeks along with their tradition of marble sculpture. Non-figural supports became commonplace in Roman marble statuary from the late republican period onwards.