On the Threshold

Most of us take doors for granted. We pass through doorways tens of times each day, without reflection. The door is, however, a powerful feature of human mentality and life-practice. It controls access, provides a sense of security and privacy, and marks the boundary between differentiated spaces. The doorway is also the architectural element allowing passage from one space to the next. Crossing the threshold means abandoning one space and entering another, a bodily practice recognized both in ritual and language as a transition between social roles or situations. Doors and thresholds are thus closely linked with rites de passage, the word ‘liminality’ itself stemming from Latin limen, ‘threshold’. This does not imply that each and every crossing of a threshold constitutes a liminal ritual, but rather that passing through a doorway is an embodied, everyday experience prompting numerous social and metaphorical implications. A volume on thresholds in fiction asks why the threshold exercises such a riveting grasp on human imagination; why it is such a resonant space (Mukherji Reference Mukherji2011:xvii). The characterization of the threshold as a resonant space precisely captures its affect. The threshold is evocative, a locus of heightened anticipation.

The seeds for this book were sown nearly a decade ago when, during data collection for my master’s thesis, I noticed a strange concurrence between two written sources related to the Viking Age. One text, ibn Fadlān’s Risãla, was from the Arabic Caliphate, containing an eyewitness report of a ship burial of a Viking chieftain on the river Volga in 922 CE. The other was an episode from Flateyjarbók, a late Icelandic saga of which the oldest surviving copy dates to the fourteenth century, recounting a strange fertility ritual on a remote farm in Viking Age Norway.1 Even though the texts were transcribed centuries apart and in vastly different geographical and cultural contexts, they both touched on the same, eerie topic: a woman being lifted – or asking to be lifted – above a doorframe, to enable her to see into a different realm.

This image took root in me; I started wondering if doors were related to ritual practices in the Viking Age. Simultaneously, I had started realizing the vast and largely untouched potential in considering the archaeological remains of the built environment of the period not only as functional-economic constructions but as social expressions, producers, and agents. Gradually, these two themes forged one question: How can an in-depth study of an everyday material object – the door – generate new knowledge of social, ritual, and affective experience of the Late Iron and Viking Ages? In answering that question, this book offers a fresh approach to the (pre)historic period often termed the Scandinavian Late Iron Age (c. 550–1050 CE); it is a social exploration of the houses and homes of the Vikings in a pivotal period of European history. The crux of the book is that it uses a highly charged architectural element as an entryway to explore the households, hierarchies, and rituals of the Viking Age.

New Gateways to the Vikings

The Vikings are well known to us. We can conjure images in our minds without blinking – long-haired, bearded, frenzied warriors, swords in hand. And, equally obvious, the conjured image is to some extent false, or at the very least it is one-dimensional and stagnant. In a thought-provoking article, Neil Price points out that the Vikings we study today are very different from the ones under scrutiny twenty years ago – or even further back. ‘They have grown’, he writes, ‘they have gained more depth and resolution’ (Price Reference Price, Eriksen, Pedersen, Rundberget, Axelsen and Berg2015:7). To my mind, that is only partially true. In arenas such as religion and ritual, dress and gender, and especially mortuary practices, the Vikings have gained more depth. But in terms of everyday life, in the Vikings’ households, and their use and conceptualization of domestic space, I argue that there is still room to grow. In a recent assessment of Viking archaeology, Sarah Croix (Reference Croix2015) claims that Viking studies are to some extent regressing. After the last decades’ gender critique and a focus on Viking ritual, craft, and especially trade, an international exhibition launched in 2013 unapologetically focussed on the stereotypical Viking: the male raider and warrior (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Pentz and Wemhoff2014). With the enormous popularity of the Vikings in mainstream culture, Croix (Reference Croix2015:93) contends that the field of Viking studies is feeding the public what it expects, ‘and repeating itself within a simplified and ever more narrowing frame’. In my opinion, while the perceptions of Vikings as warriors, traders, and colonists are in the forefront of public discourse, as well as the object of a substantial amount of research on the Viking Age, the domestic sphere is still perceived as an unproblematized, familiar, and somewhat trivial sphere.

In contrast, the empirical basis and the point of departure of this work are the fragmented remains of the doors, but also the dwellings, of the Vikings. Even though the door will be on centre stage in this study, it makes little sense to discuss entryways without considering the space to which they lead. I thus draw on the latent possibility in using architecture and the built environment to answer questions of social organization, architectural templates of movement, ideology, affect, and ritual behaviour. The question of how one particular material construction can elucidate the social fabric of the Viking Age relates to a broader attempt to develop more theoretically engaged perspectives in Viking archaeology. More important, though, is the question: How does the Viking Age look from the point of view of the house?

In recent years, developments in excavation technique have unearthed thousands of prehistoric houses in Scandinavia. This new dataset provides novel opportunities to examine the practice of dwelling through physical remains of architecture. This book draws on the generally unexploited potential embedded in the archaeological record of house remains from Late Iron Age Scandinavia, with a primary focus on Norway. The corpus, presented in the Appendix and referenced throughout, consists of 99 longhouses and 17 shorthouses, in total 116 buildings interpreted as dwellings, from 65 archaeological sites. Embedded in the corpus is a substantial archaeological material of doors and entrances, with a total number of 150 doors. The primary attention on Norway is a strategy to limit the scope of inquiry, and to present Norwegian settlements of the period into one publication, as this material has not been compiled previously. However, I will use settlement material from other parts of Scandinavia, mainly south Scandinavia (Denmark and Scania), and the Norse worlds comparatively, in order to explore differences and similarities between the south and central Scandinavian architectural expression. I will also briefly discuss other building types such as courtyard sites, cult buildings, and mortuary houses.

Research on Iron and Viking Age settlement has traditionally focused on functional, economic, and agricultural aspects of settlement. While these topics are clearly important, there are still unrealized possibilities in using the material remains of houses in discussions of the spatiality and social organization of dwellings. By drawing on the potential embedded in postholes, doors, and hearths, this study complements existing research by considering access and entry to domestic space, the composition of the household, and the affective webs of the house. It investigates the ritualization of doors and thresholds in the Viking Age, the relationship between houses, doors, and the dead, and the significance of everyday, domestic life. Material objects are herein considered as more than economic commodities, status symbols, or, in the case of architecture, climate shelters; and are rather explored as social entities forming relational assemblages, in line with much of current archaeological thinking (e.g. Fowler Reference Fowler2013; Jones and Boivin Reference Jones, Boivin, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Lucas Reference Lucas2012, Reference Lucas, Bille and Sørensen2016; B. Olsen Reference Olsen and Tellefsen2010). I will repeatedly argue that Viking longhouses have forms of agency and vibrancy, that they can have social lives, and that the inhabitants’ lives were very much entwined with that of the house. Significantly, I hope to map a more comprehensive universe of the Vikings, where the people of the Viking Age are fleshed out and embodied.

I therefore aspire to see the Vikings as more complete human beings specifically through their relation to and use of social space. This work cannot and will not be a complete social archaeology of the Viking Age; it does not consider for instance the Viking raids, colonization, or trade. The aim is rather to carve out, from the grey block often termed ‘the domestic sphere’, a higher-resolution picture of lived experience in Viking Age Norway. Everyday life is the foundation of this work; consumption, seating arrangements, sleeping patterns, everyday movement through domestic space. In some chapters, the slaves of the Vikings are considered, and their everyday life experience. Viking children, and women, and males of different status are brought into the picture. In other chapters, I consider rituals, and deposition, and the house as an active agent in the creation of a social world. I hope to portray the Vikings to a higher extent as real people, with desires and aversions, agendas and affects, anxieties and beliefs. I embed them within a physical, architectural frame that not only significantly shaped their movements, thoughts, and actions, but that was part of them and of which they were a part in turn. In short, the aim is to contribute to the development of a social archaeology of the Viking Age. And my gateway for doing so is through the door of the domestic house.

The House: Ordering Space, Bodies, and Social Relations

… the house we were born in is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits. After twenty years, in spite of all the other anonymous stairways; we could recapture the reflexes of “the first stairway”, we would not stumble on that rather high step. … The house we were born in is more than an embodiment of home, it is also an embodiment of dreams.

Whereas social anthropology, sociology, and several subfields of archaeology have long been interested in houses and households as analytical categories, as well as the connections between the built environment and social organization, such issues have arguably received limited attention in Scandinavian Iron and Viking Age studies. People, and their everyday social, political, and ritual practices, are often more or less invisible in discussions of houses and settlements. Ruth Tringham’s famous statement that the inhabitants of prehistoric houses are merely ‘faceless blobs’ (Reference Tringham, Gero and Conkey1991) rings no less true in the late 2010s than it did in the early 1990s.

The earliest studies of Iron and Viking Age settlement in Norway were rooted in a cultural-historical framework, and generally of a descriptive character (Grieg Reference Grieg1934; Hagen Reference Hagen1953; Petersen Reference Petersen1933, Reference Petersen1936). A particular research strand in Norwegian archaeology has been the tradition of using written records, cadastres, maps, and toponyms to chart Iron and Viking Age settlement, as historical farms are seen as the natural successors to postulated prehistoric farms (Gjerpe Reference Gjerpe2014; Pilø Reference Pilø2005). This relates partly to Norwegian archaeology’s emergence in a national romanticist framework in the nineteenth century (see also Chapter 3).

Subsequent works in the second half of the twentieth century became increasingly attentive to questions of economy and subsistence, in line with the developing processual framework (e.g. Jacobsen Reference Jacobsen1984; Kaland Reference Kaland and Knirk1987; Randers Reference Randers1981). Publications primarily focus on calculations of produce, cultivation intensity, and the number of livestock, and rarely contain plans of the houses and settlements. In line with the predominant archaeological thinking of the day, this points to an underexplored analytical consideration of the house structures themselves. Yet, there were other voices in the settlement debate. Through several works, Bjørn Myhre considered the settlement of southwest Norway (Reference Myhre1980, Reference Myhre, Myhre, Stoklund and Gjærder1982a, Reference Myhre1982b, Reference Myhre, Myhre, Gjærder and Stoklund1982c, Reference Myhre1983). Even though Myhre was influenced by the processual and functionalist way of thinking, he also pinpointed socially oriented questions of settlement and used models from social anthropology. Likewise, Trond Løken’s work on the Bronze Age to Early Iron Age site Forsandmoen, Rogaland, incorporates more socially oriented questions springing from the architecture itself (Løken Reference Løken and Løken1998).

Other works have taken a political angle, focusing on the development of estates and petty kingdoms, and the role land ownership played in state formation (Iversen Reference Iversen2008; Skre Reference Skre1998). Especially the works of Dagfinn Skre (Reference Skre1997, Reference Skre1998, Reference Skre2001) significantly rejected the idealized egalitarian perception of Viking settlement and illuminated the role of freed dependants and slaves in large-scale settlement patterns. Skre opens for a debate of ideological and political aspects of settlement, where his focus is primarily on landholding, tenancy, and social economy explored mainly through burial material and written sources (Skre Reference Skre2001). Yet, there is limited consideration of everyday, domestic life, or indeed the house structures themselves; the estates identified in later written sources are the important elements, as pawns in large-scale power plays.

In the same period the number of excavated settlements in Norway started to increase dramatically due to the methodology of excavating with mechanical diggers underneath cultivated land. However, accumulating a larger dataset of houses from the Iron Age did not in itself increase explorations of social aspects of space. In contrast, British prehistoric archaeology, especially during the peak of post-processualism, has offered cognitive takes on architecture, such as tracing symbolic spaces or viewing houses and monuments as cosmological expressions (e.g. Bender et al. Reference Bender, Hamilton, Tilley and Anderson2007; Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson1999b; Tilley Reference Tilley1994), yet, I would argue, again often at the cost of lived experience. Such approaches moreover rarely seeped into Scandinavian considerations of architecture and households, at least in Iron Age scholarship. In Scandinavia, limited consideration of the British-centred phenomenology of space has taken place, or the lived experience of architecture. I argue that there has been a tendency of a dichotomy between mortuary archaeologists focusing on ritual, social organization, and ideology; and settlement archaeologists – at least those working with non-elite settlements – concentrating on typology, economy, and function. As a result of this division of research agendas (and here I am painting with a broad brush), a picture emerges where the manner in which a past society handled their dead may provide knowledge of ideas, rituals, and ontology, while the built environment is reduced to a neutral backdrop to social practice.

In recent years, however, studies of built environments in Scandinavia and the wider Viking world that transcend a homo economicus perspective have started generating new knowledge in a range of areas: social and political process (Boyd Reference Boyd and Harkel2013; Dommasnes et al. Reference Dommasnes, Gutsmiedl-Schümann and Hommedal2016; Hadley and Harkel Reference Hadley and Harkel2013; Herschend Reference Herschend2009; Holst Reference Holst2010), structure and practice (Webley Reference Webley2008), ritualization (e.g. Carlie Reference Carlie2004; Eriksen Reference Eriksen, Eriksen, Pedersen, Rundberget, Axelsen and Berg2015b; Kristensen Reference Kristensen2010), the relationship between the living and the dead (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2013, Reference Eriksen2016, Reference Eriksen2017; Thäte Reference Thäte2007), and gender relations (Croix Reference Croix, Kristiansen and Giles2014; Milek Reference Milek2012). A key Scandinavian scholar has been Frands Herschend, who in a series of works has explored notions of ordered space and considered landscapes as social agents in the Iron Age (Herschend Reference Herschend1993, Reference Herschend and Larsen1994, Reference Herschend1997, Reference Herschend1998, Reference Herschend2009).

It is also increasingly accepted that many, if not most, agrarian, economic practices, such as planting crops, ploughing, grinding, cooking, or weaving, had ritual and mythological overtones in the Iron Age world view (e.g. Fendin Reference Fendin, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Gräslund Reference Gräslund, Sundqvist and Van Nahl2001; Kristoffersen Reference Kristoffersen2000; Welinder Reference Welinder1993). The house was also the central locus of many forms of feasts and seasonal celebrations, as well as rites de passage: burials, births, and weddings took place within the house. All deities in the Norse pantheon had their own, named hall buildings over which they ruled; when warriors died, they expected their bodies to go live in another house – Valhǫll or Fólkvangr. Moreover, the world itself is in kennings and Eddic poetry likened to a hall or house, the sky as a roof, and so on (e.g. Rigsþula, Vǫluspá 64). A foundation of this book is thus that the longhouse not only had ritual connotations, but was deeply entwined in the Late Iron Age ontology, and moreover, that social, ritual, and economical practices were interwoven into a tapestry that could not be unravelled (sensu Bradley Reference Bradley2005).

The built environment is an accumulated and influential assemblage of social practice, repeated actions, spatial ideals – in other words, of lived space. Architecture is always the result of past action (e.g. McFadyen Reference McFadyen, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013). The house and its praxis has been placed in the very centre of the social fabric of pre-industrial societies, as it has been argued that in cultures without literacy, inhabited space and the house constitute the primary objectifications of social schemes (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977:89–90). The house is, in Bourdiean terms, both a structuring and structured structure – i.e. both a cause and effect of social process, and a primary field for inscribing the body with a specific habitus. However, John Robb suggests that instead of simplistically applying ideas such as habitus in prehistory or ‘look for agency’ in the archaeological record, we should rather understand action as genres of behaviour: ‘a set of institutionalized practices recognized as a distinct activity’ (Robb Reference Robb2010:507). Feasting, warfare, mortuary rituals, or cultivation would constitute different genres of behaviour. Moreover, Robb stresses that agency is not necessarily embedded in disparate individuals but in relationships, and that these relationships are fundamentally material. Agency can thus be defined as ‘the socially reproductive quality of action’ within relationships among human and non-humans (Robb Reference Robb2010:494). Houses create the contexts for many different fields of action and genres of behaviour. Moreover, the influence of the built environment is certainly part of a reciprocal relationship between the house and its inhabitants, and their daily, unreflected and embodied practices; the house as the product of the social choices of the builders and inhabitants, and a reification of past action, in turn affecting new generations emerging within the house.

To consider the lived experience of dwelling it is necessary, I argue, to consider bodies in space: bodies building space, using space, navigating space, and transforming space. Increased attention has been directed towards the senses and the body recently, within the Iron Age (e.g. Hedeager Reference Hedeager, Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010; Lund Reference Lund2013) and especially in European later prehistory at large (e.g. Borić and Robb Reference Borić and Robb2008; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2013; Rebay-Salisbury et al. Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Sørensen and Hughes2010; Robb and Harris Reference Robb and Harris2013). Bodies are ambiguous, simultaneously objects and subjects, a site where both the self and the other are negotiated and performed. Bodies are places of desire, but also of violence, biological processes, abjection, and alienation. Embodiment can be defined as the way people engage with the world through their bodies. The way we experience the built environment, as the rest of the world, is through our corporeality (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977; Merleau-Ponty Reference Merleau-Ponty2012 [1958]). Mauss (Reference Mauss1979) famously observed that the techniques of the body: the way we walk, sleep, dance, run, and make love, are all socio-cultural idiosyncrasies. Children in particular are inscribed with, or rather, imitate, the adults’ movements of the body, and thereby acquire sets of socially conditioned body movements that constitute culturally specific strategies for experiencing and mediating the world (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977; Mauss Reference Mauss1979; Wilson Reference Wilson1988:153).

The perspective of bodily learnt practice and experience is highly relevant for a study of doors and dwellings. Movements through domestic space, seating arrangements, the order in which food is served, the room you are not supposed to enter, the threshold only some are allowed to cross – these small, household practices are both executed by and absorbed into the body, creating and recreating the social world. And as the social systems are institutionalized in the architecture, differentiated power structures are legitimized and euphemized (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1989). Harris and Robb (Reference Harris, Robb, Robb and Harris2013b:3) offer the useful working concept body worlds, which they define as ‘the totality of bodily experiences, practices and representations in a specific place and time’. Emanating from embodiment, some scholars emphasize the performativity of architecture, of how it is only when bodies, architecture, and things come together that a space becomes a place (Kaye Reference Kaye, Bille and Sørensen2016). Other scholars stress that the built environment can be understood as a producer of affective fields (Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010), engendering certain forms of emotional responses in its users (Harris Reference Harris, Bille and Sørensen2016; Love Reference Love, Bille and Sørensen2016), or specific atmospheres (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2015). I consider doors, doorways, and the house at large, not only as mediators of habitus, but as things which shape, move, and merge with people, in a process where houses and people together engage in an embodied process of dwelling.

Towards a Social Archaeology of the Viking Age

Novel theoretical perspectives have opened the door to new questions and new answers in Viking archaeology. The eclectic internally conflicted wave of approaches hurtling forth from the beginning of the third millennium has been collectively termed ‘new materialism’ (Thomas Reference Thomas2015). Although controversial and provocative, this shift to relational thinking offers a vast range of new perspectives in archaeology. Among the perplexing strands of symmetrical archaeology (Olsen Reference Olsen2003; B. Olsen Reference Olsen and Tellefsen2010; Witmore Reference Witmore2007), meshworks (Ingold Reference Ingold2007), Actor-Network Theory (Latour Reference Latour2005), assemblages (Fowler Reference Fowler2013; Hamilakis and Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017), entanglements (Hodder Reference Hodder2012), vibrancy (Bennett Reference Bennett2010), and the ontological turn (Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Fowles, Holbraad, Marshall and Witmore2011; Marshall and Alberti Reference Marshall and Alberti2014) I wish to emphasize three points because they explicitly and implicitly cast the story of this work.

The first is that material culture, animals, landscapes, things, and people form relational assemblages (Bennett Reference Bennett2010; Fowler Reference Fowler2013, Reference Fowler2016; Hamilakis and Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017; Lucas Reference Lucas2012); a wave of thinking in current archaeological discourse that springs primarily from the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari2013 [1987]) and the subsequent work by DeLanda (Reference DeLanda2006). While I argued that architecture is always the result of past action, it is certainly not merely the result of humans acting ‘upon’ dead materials. Rather, the Iron Age longhouse is an excellent example of an assemblage of builders, materials, landscapes, inhabitants, weather, guests, animals, things, practices, technologies (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2016), all engaging in a process of perpetually becoming a house, at an intersection between construction and decay (e.g. Harris Reference Harris, Bille and Sørensen2016; Jones Reference Jones2007; Lucas Reference Lucas, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013). A reductionist view of houses as merely the physical construction of the walls and posts; or only the (human) inhabitants; or the actions that take place within, becomes arguments ad absurdum – the house is the emerging aggregate of all these entities, inextricably entwined.

The second point is that everyday things have to some extent been overlooked in current discourse. However, everyday things are interwoven with human lives; they are aggregates of lived experience, and by studying mundane things we access other perspectives on the Viking Age than fine metal work, monumental burials, or warrior swords can allow. An implicit motivation for this study is thus to illuminate the mundane, the ordinary, the non-spectacular. For example, in a thought-provoking article about emotion and material culture, Harris and Sørensen (Reference Harris and Sørensen2010) argue that archaeology should engage with questions of emotion and affect. They contend that emotions are not only internal and immaterial phenomena, but occur in the encounter with a material world, and use the case study of a spectacular Late Neolithic monument, the henge at Mount Pleasant, to discuss the role of emotion in building and rebuilding such a site over an extended period of time. In her comment to the text, Åsa Berggren, however, points out that the enormous monument is an example where it is relatively simple to argue that materiality elicits emotional responses. She writes: ‘It would, for example, have been interesting to see [Harris and Sørensen] apply their ideas to some of the more mundane archaeological materials, from, for example, settlements that would be more explicitly connected to everyday life’ (Berggren Reference Berggren2010:164). The critique resonates with this project. Archaeologists have for a long time, through virtually all archaeological paradigms, favoured the monumental: the richest finds, the largest mounds, and the most elaborate monuments.

In a sense, this book starts where Nicole Boivin ends her stimulating Material Cultures, Material Minds (Reference Boivin2008). Boivin lists a number of ‘… mundane, but powerful objects and environments that create us as we create them’, such as pots and pans, fishing hooks, pendants, carpets, parks, artworks, pacemakers, and yes, even doorways. She concludes by stating that we have only just begun to explore how ‘this mass of simple things has shaped and transformed our thoughts, emotions, bodies, and societies’ (Reference Boivin2008:232). This study is intended as exactly that, an exploration of how an everyday material feature, the door, shaped and transformed thoughts, emotions, bodies, and societies in a specific prehistoric period. It is, after all, everyday life that builds a social world.

Third, this work is intended as a contribution towards a social archaeology of the Viking Age. Some prominent thinkers in current discourse see a clear opposition between social archaeology and a materialist archaeology (Latour Reference Latour and McMullin1992, Reference Latour2005; Webmoor Reference Webmoor2007). The sharpest critique of social archaeology was presented by Webmoor and Witmore (Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008), closely shadowing Latour, in arguing that the social has become ‘both the explanandum and the explanans for archaeological inquiry’, an invisible force that somehow is both cause and effect, with a significant anthropocentric bias (see also Webmoor Reference Webmoor2007). It is largely proponents of Actor-Network Theory and symmetrical archaeology that are refuting the concept of social, because it in their view inherently describes relations between humans and other humans, upholding a Cartesian dichotomy between the ‘material’ and ‘social’ world. Although the critique has merit in criticizing the use of social as a universalist and a catch-all phrase, I still claim ‘social archaeology’ has significance. First because, as it has been argued against Latour, if ‘the social’ should be banished from our vocabulary, how can we continue to speak of equally ephemeral concepts such as ‘the economic’ or ‘the political’ (Rowland et al. Reference Rowland, Passoth and Kinney2011)? Second, Webmoor and Witmore (Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008:55) imply that the social has superseded its role ‘as a corrective’ in archaeology. While that may or may not apply to the Anglophone world, there are large territories of archaeology where the post-processual wave did not become quite as ubiquitous as in, e.g. British prehistory (cf. Ribeiro Reference Ribeiro2016), and Viking studies is certainly among those lands. The use of social in this work is indeed intended as a corrective to traditional, largely economic perspectives on the Viking Age: a heuristic to shift the focus from agrarian practices to people, from trade relations to affective relations, from typology to agency. And third, social archaeology is herein understood as inherently relational, springing from the view that societies are formed not merely by humans, but by wider, heterogeneous agencies (Boivin Reference Boivin2008; Lucas Reference Lucas2012). In line with Gavin Lucas’ ‘new’ social archaeology (Reference Lucas2012:258–265), the social emerges through networks and relationships among humans, animals, and things, rather than somehow existing ‘behind’ or ‘previous’ to them. We can expand on the old analogy referenced by Malafouris (Reference Malafouris2013:25), where the archaeologist searching for the social behind a stone axe (or indeed a longhouse), can be compared with a visitor to Cambridge, who, after seeing the colleges, departments, and the library, asks to be shown the university.

Consequently, these building blocks – relational ontology, everyday materials, and social archaeology – form the foundation of the pages ahead. Instead of seeing material culture as a ‘representation’ of the world, materials are the world, physically and socially. Not only household things but also the house itself is inextricably entwined with human lives.

Architecture of the Argument

Many pathways lead to a more socially grounded approach to the Viking Age; mine has been through the door. Or, to put it another way, I have chosen to place a specific architectural element under scrutiny – though not in isolation – and to let the doorways and entrances speak.

Some practical concerns and definitions should be clarified. This book addresses the time between 550 and 1050 CE. In Northern Europe, this timeframe has several chronological definitions and names (e.g. late Germanic, Merovingian, Vendel, Viking, Early Medieval), and a common chronological framework has not yet been developed. In Norwegian archaeology, this chronological scope consists of the Merovingian period (c. 550–800) and the Viking Age (c. 800–1050); the two periods are collectively termed the Late Iron Age and are regarded as belonging to prehistory. In this work, Late Iron Age and Viking Age are used as synonyms for the second half of the first millennium, i.e. sixth to eleventh centuries. At points where a more finely tuned chronology is of relevance, I will point out the dating in more explicit terms; however, as stated in the Appendix, many houses cannot be dated very precisely, and chronological development is therefore not at the forefront of this study. I have already stated that Norway constitutes the primary research area. Regarding geographical nomenclature, the modern nation-state Norway had of course not yet formed in the Late Iron Age. When ‘Norway’ and ‘Norwegian’ is used in this text, areas of modern-day Norway are implied.

At this juncture, I will also briefly state the book’s stance on using written, medieval sources to understand societies centuries older than the oldest surviving manuscripts. With the exception of short and formulaic inscriptions in the runic alphabet, Late Iron Age Scandinavia was a society without text. The first longer Scandinavian texts were written in the Latin alphabet after the consolidation of the State and the conversion to Christianity in the beginning of the second millennium. The relationship between medieval written sources concerning the Late Iron Age and the material record of the period has been subject to changing academic approaches since the emergence of Viking studies. From a somewhat uncritical reading of textual sources (e.g. Munch Reference Munch1852) to a critical approach refuting almost any source value (Weibull Reference Weibull1911, Reference Weibull1918); most researchers today seem to aim at a middle ground (e.g. Andrén Reference Andrén2005, Reference Andrén2014; Hedeager Reference Hedeager1999, Reference Hedeager, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2004, Reference Hedeager2011; Price Reference Price2002, Reference Price2010, Reference Price2014). In general, today’s scholars neither take medieval sagas and poetry at face value, nor disregard their insight into twelfth to fourteenth-century reflection and commemoration of a not-too-distant past. The written sources do reflect a high-medieval world view, but at a time where oral traditions stood strong. Late Iron Age Scandinavia is often understood as an oral culture where narratives and legal rule were remembered through formalized language (Andrén et al. Reference Andrén, Jennbert, Raudvere, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Bertell Reference Bertell, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Brink Reference Brink and Hermann2005a); and where society, in spite of the conversion and changing political organization, alluded to its recent pre-Christian past (Sørensen Reference Sørensen, Lidén and Steinsland1995). Moreover, several objects, such as rune stones, gold bracteates, picture stones, and hogback stones display scenes and narratives known from the later, written sources (e.g. Andrén Reference Andrén1993; Hauck Reference Hauck and Schmidt-Wiegand1981; Lang Reference Lang, Hawkes, Campbell and Brown1984). These resilient motifs are often mythological, such as Óðinn on his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, or Týr losing his hand to the Fenris wolf. Therefore, motifs shared between material culture from the Late Iron Age and texts from the medieval period must be older than the time of transcription of the texts, and moreover, the narratives must also have been remembered and related in a consistent manner centuries later.

Consequently, I use written sources, mainly Eddaic poetry, Icelandic Sagas, and early legal texts, sporadically in a complementary manner; aiming to critically use the Norse texts as tools for thought. Particularly, I use the strategy of identifying homologous motifs in the archaeological record and in the later texts, with particular regard to descriptions of households, architecture, or legal and ritual practices. This book thus aligns itself with scholarship utilizing the vast potential of working in a period of (pre)history that includes contemporary descriptions of Scandinavia, later written sources reflecting the social memory of the period, iconographical depictions on for example rune stones and metal objects, and the recent expansion of archaeological house material. Together, this eclectic material has the potential to create a high-resolution picture of the Viking Age.

In approaching the issues at hand, I have divided the book into three parts. The first part introduces the themes of the work, Part II tackles the houses, households, and landscapes of the Viking Age, while Part III develops the argument that doors and thresholds were perceived as ritual objects and ritual spaces in the Viking Age. Thus, having established the raison d’être of the study in the present chapter, the second chapter will introduce the main protagonist of the book: the door itself. In Chapter 2, I map the connection between architecture and affect, exploring how buildings can create certain bodily experienced reactions in its inhabitants. I also consider how and why the door is linked with ideas of liminality, transgression, and transformation.

Part II, consisting of Chapters 3–5, forms the very backbone of the book. Emanating from a fresh overview of Norwegian settlement material from the period, Part II takes the reader inside the Viking house to explore the household and the agency of architecture, and ends outside in the social landscape. Chapter 3 briefly maps the overall distribution of Late Iron Age settlements in Norway. The weight of Chapter 3, however, lies in analyses of social space and the Viking household. Chapter 4 brings the reader further inside the spatial and social matrix of the Scandinavian-style longhouse. Through the method of access analysis, the door’s agency in facilitating or denying encounters within the house; creating axes of movement and barriers of exclusion, is discussed. In Chapter 5, the reader will find herself outside the house. In this chapter, I shift perspective from the internal spatial order of the longhouse to its exterior, situating the house and the door in social, cosmological, and political landscapes, arguing that the idea of the house is shifting at this time. The house, as a mental and political institution, is under transformation.

Finally, Part III turns the reader’s attention to the ritual significance of doors and entrances in Late Iron Age Scandinavia. Chapter 6 takes the links between the body and the house as its subject. It considers the associations between thresholds, sexual acts, and marriage rituals, and moreover, connects the links between houses and bodies with practices of deposition in domestic space, marking the social biographies of houses and people. Chapter 7 maps a connection between judicial practices and the door, before examining the relationship between the Viking house and the dead, and proposes that in the Viking Age, the domestic door was used as portal to the realm of the dead. The book concludes with Chapter 8.

I will end this introduction by charting the scope of this book. Readers hoping to find a comprehensive overview of door symbolism through the ages will surely be disappointed. And although the study provides the first overview of Viking Age settlement in Norway, it does not dwell on local architectural tradition, construction technique, or detailed chronological development. Moreover, it does not in any detail deal with subsistence practices, agricultural crops, pollen analyses, and the like. Even though the considerations listed are clearly topics of high significance, other scholars will be much better situated to write those books. This work has its own aims and aspirations. Most fundamentally, my objective has been to breathe life into the postholes and hearths archaeologists excavate. Springing from a social and relational approach to everyday material culture, the book aims to demonstrate how domestic life is always entangled both with large-scale social and political schemes, and at the same time, with small-scale, embodied, and affective experience. In the end, I can only hope that readers will feel a sense of resonance when reading it.

There are things known, and there are things unknown, and between are the doors

Architecture and Affect

The door is the protagonist of this book; therefore, it seems only reasonable to give it a proper introduction. Doors are ubiquitous and mundane things in most human lives – they are everyday objects. We pass through doorways tens, or even hundreds, of times every day without much contemplation. And yet, the door serves a range of functional and social purposes, today and in the past. It is a commanding architectural archetype. The power of the door has been used consciously throughout history. According to architectural philosopher Simon Unwin (Reference Unwin2007), the doorway is one of the most effective and affective instruments available to the architect, capable of influencing perception, movement, and relationships between people. The definition of all architecture is, in Unwin’s words (Reference Unwin2009:25–34), to identify a place. The exceptional thing about a doorway is that it is simultaneously a place and a non-place. The door stands between spaces, but also connects them.

A door consists of several elements. The main components are the door itself and the doorframe. The doorframe consists of two vertical doorposts or jambs, and two horizontal pieces, the threshold and the lintel. The opening of the door is the doorway. The etymology of door and threshold implies something of their history. Door, Norwegian dør, Old Norse dyrr, Old English dúru: the root of the word is interpreted to be Indo-Iranian *dhwer/*dhwor,*dhur. The root is often stated in plural, implying that the door was viewed as something consisting of several parts. An archaic adverbial form of door exists in languages such as Latin, Greek, and Armenian, literally meaning ‘out, outside’. The door was thus viewed from inside the house, ‘… and for the person inside the house *dhwer-, *dhur- marks the boundary of the inner space of the house’ (Bjorvand and Lindeman Reference Bjorvand and Lindeman2007:208–209, my translation).

Threshold, on the other hand, Norwegian terskel or troskel, Old Norse þreskǫldr, Old English þerscold, goes back to Germanic *þreskan, to tread, trample. The Norwegian etymological dictionary finds the etymology unclear (Bjorvand and Lindeman Reference Bjorvand and Lindeman2007:1141), whereas Unwin (Reference Unwin2007:79) states that the threshold originally was a construction of timber boards placed transversely across opposing doorways of a barn during threshing, used to keep the grains inside the barn. If correct, the etymology of threshold implies that the structure is closely connected with agriculture, but also with the body and embodied practice, in the sense of treading, trampling.

The Door and Access

Doors have arguably, in some form, existed as long as the human species. The need to draw a boundary between us and them, between dwelling and landscape, between outside and inside runs deep. It is impossible to state what constitutes the first door. Is a tent opening a door? A cave opening? Mobile hunter/gatherer groups may have strong ideas and taboos regarding the opening to their dwellings, even though these are not permanent (e.g. Grøn and Kuznetsov Reference Grøn, Kuznetsov and Larsson2003; Yates Reference Yates and Hodder1989). Yet, it was plausibly when people became sedentary after neolithization that the deep symbolic and psychological idea about the house – and thereby the door – was cemented. According to Peter Wilson’s (Reference Wilson1988) classic The Domestication of the Human Species, the innovation of the house generated a range of social consequences. Among these were a proliferation of material culture; a novel instrument to conceive (and manipulate) the social and cosmological structure of the world; and, important in this context, delimiting settlements in space provided boundary analogies for defining a community or household (Wilson Reference Wilson1988:58–60). The house and its boundaries hence generated new templates and instruments for social negotiation; and new forms of relationality between architectural structures, materials, ideas, and human and non-human agents.

The primary function of the door is to provide or deny access to rooms, spaces, and buildings. A room without doors is not a room at all, but a tomb (Unwin Reference Unwin2007:193). The door is thus an access control point, where the person in control of the door invites someone in or shuts someone out (Hillier and Hanson Reference Hillier and Hanson1984:18–19). Connected to its function as a spatial control point, the door provides a sense of security to the spaces it guards. The door’s agency in controlling access extends not only to entrances but also to internal doors within a building. Other functional features of doors are their ability to provide light and ventilation, and their strategic use to enhance insulation and keep warm air circulating within the house (Schultze Reference Schultze2010). However, inseparably forged with its functional purposes, the door has strong social communicative power.

A telling quote has been attributed to Madeline Albright during the Middle East peace negotiations in 2000: ‘Shut the gate! Don’t let Arafat out’ (Unwin Reference Unwin2007:156). Doors are, by nature, including or excluding; they physically create division and differentiation. An open or closed door can communicate whether the occupant is available or busy, whether a guest is welcome or unwelcome (Hall Reference Hall1966:135–136). Closed doors can send strong signals about hierarchy and exclusion. When the U.S. Secretary of State yells that someone should shut the gate to stop Yasser Arafat from leaving peace negotiations, she is (presumably) not keeping him there by force. She is rather drawing on the significant, non-verbal social statement a closed door can make – in this instance, to keep Arafat from escaping a particularly charged social and political situation. And anyone who has ever had a door shut in their face will know that this is a very effective way of inducing shame, confusion, and anger in the person on the receiving end.

The Door and the Body

Architecture, like all human experience, is experienced through the body and all its senses: through vision, smell, sounds, movement, and touch (Merleau-Ponty Reference Merleau-Ponty2012 [1958]; Unwin Reference Unwin2009). In recent years, the focus on the sensual aspects of archaeology has increased (e.g. Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2013), leading to investigations of ’soundscapes’ and olfactory environments, but also to considerations of how the material world can elicit emotional responses in human beings (Fleisher and Norman Reference Fleisher and Norman2016b; Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010; Tarlow Reference Tarlow2000). A seminal scholar who approached the house through perspectives rooted in phenomenology and affect is the philosopher Gaston Bachelard (Reference Bachelard1994 [1964]). In his work The Poetics of Space, Bachelard explores – in a modern context – why the house is such a crucial element of human lives. He connects the door with transformation, with freedom and dreams:

How concrete everything becomes in the world of the spirit when an object, a mere door, can give images of hesitation, temptation, desire, security, welcome and respect. If one were to give an account of all the doors one has closed and opened, of all the doors one would like to re-open, one would have to tell the story of one’s entire life.

The philosopher Georg Simmel links the door with the very nature of human beings. Contrasting the door with the bridge, another liminal passageway, Simmel finds the door to be more significant. The door is, he writes, ‘a linkage between the space of human beings and everything that remains outside it, it transcends the separation between the inner and the outer’ (Simmel Reference Simmel1994:7). Simmel stresses that the door allows us to leave the spaces we have created, and in this way, it ensures freedom. Bachelard similarly relates the door with daydreams, yet, as the end of his quote suggests, he emphasizes how doors punctuate life experiences – which doors did we choose to open over our lifetime, and which did we close?

The sketch by Unwin (Figure 2.1) demonstrates how doorways reflect human form and movement, which is directed forwards both by sight and orientation of body. Doorways reproduce the axial symmetry of the body, and manipulate perception and gaze, as well as movement. Doors funnel people in a certain direction and lead them into certain spaces (Fisher Reference Fisher2009). Yet, it is worth noting that Unwin’s sketch it not universally applicable. The medieval vernacular doors from Norway, which are discussed later in this chapter, did not reflect the human form, and led to the development of idiosyncratic, bodily learnt movement patterns. Still, because of its connection with the body, the door can be used as a conscious tool when constructing buildings. The architect can use the placement of the door to manipulate movement and vision lines throughout the house (Fisher Reference Fisher2009; Unwin Reference Unwin2007). The door can be placed so that it draws the eyes of the beholder, creates a picture frame, or crafts linkages between what can be seen from the door of the outside world. It can simultaneously draw the gaze and direct movement to a person, object, or architectural feature inside (Figure 2.2). Architecture has thus been described as ‘inherently a totalitarian activity’ because when designing a space ‘you are also designing people’s behaviour in space’ (Acconci quoted in Kaye Reference Kaye, Bille and Sørensen2016:303).

2.2 Three ways the door can create vision lines, manipulating the perception of space and objects.

An important point to bear in mind, however, is that the influence architecture has over the body is not one-way. Architecture certainly propels movement through specific spatial trajectories and places the body in vast spaces or claustrophobic ones, influencing the gaze and direction of the person. Yet at the same time, the movement of the body alters the very nature of the space through which it moves. A place becomes a place only when the architecture, things, and human body come together to produce a particular spatiality – a process of becoming that is never finished in a final form (Harris Reference Harris, Bille and Sørensen2016; Kaye Reference Kaye, Bille and Sørensen2016; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2015). Imagine, for instance, a theatrical stage without any humans ever appearing, or a house without inhabitants going through the daily motions, creating and recreating their home again and again, day after day. Bodily movement, architecture, and material culture co-produce the very characteristics of a certain space through place-making.

Finally, emotion has been defined as ‘the act of being moved’ (Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010:149). This definition has an interesting double entendre for the topic at hand: doors certainly move us on a physical level, but they have the capacity to move us on an emotional level as well (and can the two ever be fully separated?). Unwin (Reference Unwin2009:214) argues that architectural transitions such as doors can influence our emotions, our behaviour, and even our self-perception. I have already discussed the strong feeling of exclusion a closed door can create. Another example is how doors used in sacral architecture can be over-dimensioned compared to the human body, to elicit a sensation of the sacral and the minuteness of the human being. The idea that built environments can elicit emotional responses in humans has been increasingly argued in archaeology in recent years (Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010; Love Reference Love, Bille and Sørensen2016; Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir, Bille and Sørensen2016; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2015). Harris and Sørensen state that while the topic of emotion has largely been viewed as speculative in archaeology, it is possible to explore how human engagement with the material world is inherently affective. In line with other attempts to collapse the dichotomy between mind and matter (e.g. Boivin Reference Boivin, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004), they suggest that emotion is not a passively experienced sensation seen from an internal mind somehow separate from the world, but rather that emotions are created in the encounter between people, things, and the material surroundings.

Unwin identifies three emotional experiences the door generates in its users. Threshold shock is the sensation we may experience ‘when we propel ourselves, too quickly for our brains to keep up, into a new and different situation’ (Unwin Reference Unwin2007:9). He uses examples such as the shock of going from a bright beach into a dark tent, or from a crowded street into the sanctuary of a church. Threshold hesitation is the social behaviour where someone about to enter a home or an office will hesitate outside the door, waiting for confirmation before crossing the threshold (Unwin Reference Unwin2007:80). The hesitation is arguably about recognizing, spatially and bodily, that you are entering someone else’s domain (cf. Hall Reference Hall1966). Finally, Unwin vividly describes the shudder we can experience upon passing through. Referencing a photograph of a doorway from an Italian palazzo, he asks the reader to imagine how it would feel to go through the door. The doorway is large enough for comfortable passage, no need to turn sideways or brush against the walls. ‘And yet’, Unwin writes, ‘you sense that frisson as you go in. You know it is safe to enter but you are not quite sure what you will find inside. It is a sensation we all experience so often that, until reminded of it, we hardly acknowledge it’ (Unwin Reference Unwin2007:76).

Doors are material structures to be engaged with, through human gaze, touch, and, especially, movement. Therefore, phenomenological and affective perspectives of the door may be valuable. Yet, critique of phenomenological perspectives needs to be acknowledged. Obviously, we cannot as twenty-first-century researchers replace a past body with our own and thereby generate the same practices, body techniques, or world views as people in the past – because all embodied engagement is historically constituted (e.g. Brück Reference Brück2005). Embodied experience of space and place is moreover not standardized within a historical context, but influenced by, for example, gender, age, health, personal life history, and social identity. Nonetheless, Harris and Robb (Reference Harris, Robb, Robb and Harris2013a:214) have addressed the tension between body universality and historical context by highlighting that although all bodies are produced by specific conditions, all societies must cope with ‘body challenges’ such as hunger, childbirth, or death. Along the same lines, perspectives rooted in phenomenology and affect have the potential of generating great insights on houses and architecture because of the close association between built environment and body. The affect of the door, the relationship between doorway and body, and the social meanings that connection generates, will neither have been static nor universal throughout human history. However, the built environment and the door have an affective potential that is worth exploring also in prehistoric contexts.

Betwixt and Between

Arnold van Gennep famously pointed out that rites de passage such as initiation rites, marriage rites and mortuary rituals consist of three stages: separation, limen, and aggregation (Reference van Gennep, Vizedom and Caffee1960 [1909]). After being separated from her social group, the subject enters a phase of liminality, an ambiguous state where she does not belong to any social group or realm. In the last state, the transformation is constituted and the subject re-enters the group in a new social position. Turner (Reference Turner1977), of course, developed the notion of rites of passage further. He emphasized the liminal or threshold phase, the ‘betwixt and between’, where social structures are dissolved and the subject belongs neither here nor there.

Doorways and thresholds are inextricably linked with liminality, even lending the concept its name. The door may entail transformational powers – a person can be perceived as altered and transformed when she crosses the threshold and enters another space. Doors and entrances allow us to transport ourselves from one space to another, between rooms and areas, between situations, and even between social roles. The built environment orders space into meaningful entities that reflect – even unfold – ourselves, as well as the order of social relations. The door is the mediator and portal between spaces and situations. From the number of adages and metaphors concerning doors, entrances, and thresholds, it is clear that European, Western mentality embeds a symbolic meaning to this motif. ‘Close a door and a window opens’, ‘On the threshold to a new life’, ‘A portal to another world’, ‘Door-opener’, and so on. Yet, not only metaphors but also liminal practices have centred on the threshold.

Van Gennep stressed the physical, embodied movement during rites of passage where the ritual subjects change spatial location. In other words, the door allows people to change their location in space and through that transform their social positions. Thus, the link between the door and transformational rituals lays in the fact that the door is the border between inside and outside. It is the physical and social boundary between spaces, and transcending the threshold means abandoning one space and entering another. This fact may seem self-evident, yet it has deep implications. The threshold is by nature both a static boundary and transitive, as it is made to be crossed. The transcendental qualities of doorways and thresholds will be reprised in several parts of this work.

Ritualization of the Door

Ritualization of the door and threshold is cross-cultural and near-universal. From the Korean threshold god Munshin to the sacred back door of the circumpolar Saami, the door seems to be deeply embedded in human minds as a liminal space and ritual instrument. Theologian H. Clay Trumbull collected beliefs concerning thresholds at the end of the nineteenth century (Reference Trumbull1896). He found that the threshold and doorway were used in ritual practices in nearly all corners of the world. Subsequent researchers from a range of disciplines have noted the ritual importance of the door (Eliade Reference Eliade2002 [1957]; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991; van Gennep Reference van Gennep, Vizedom and Caffee1960 [1909]). It falls outside the scope of this book to systematically collect all occurrences of ritualization of door and threshold, but a brief exploration shows that ritual use of the door is known in some form from all continents, and at least through the last four millennia – possibly longer. For instance, Hodder (Reference Hodder1990:119–122, 130 ff.) discusses how doorways become increasingly important in the earlier Neolithic of central Europe, partly based on ritual deposits connected with entrances. He interprets the increased emphasis on the boundaries of the house as linked with increased social competition in the form of feasting. In the Roman Republic, the door of the domestic house would be ritually opened every dawn by the janitorial servant, marking the beginning of a new day and the ‘salutatio’, the ritualized greeting between patron and client (Knights Reference Knights, Parker Pearson and Richards1994). The door, particularly the main entrance, can also work as a representation of the house and household. The Batammaliba people of West Africa, upon initiating a new house, pour beer on the threshold as a libation ritual and a sacrifice to the house itself (Blier Reference Blier1987:27).

The oldest textual evidence for a ritual, metaphorical understanding of the door that I am aware of is the Sumerian/Babylonian legend of the goddess of sexuality and warfare Ishtar entering the underworld. As Ishtar descends into the netherworld, possibly to retrieve her brother/lover Tammuz, she goes through seven gates, the doorkeeper removing one of her attributes each time until she reaches the underworld. In the Babylonian version, Ishtar, who has lent her name to one of the gates of Babylon, is quite aggressive when reaching the door (Hooke Reference Hooke2004:39–40):

It was argued a few pages ago that doors have the ability to lead movement and draw the gaze. Yet, they can also be used to obstruct passage or to confuse through, for example, false doors, hidden passages, and labyrinths. Ancient Egypt is known for the false doors from burial chambers (Figure 2.3). The door’s function was to allow passage for the dead person’s spirit, or ka, to come forth and accept the sacrifices left on the altar (Frankfort Reference Frankfort1941). On the other hand, the famous Greek myth of the Minotaur – the oxen-headed monster waiting inside the labyrinth on Crete – reflects the claustrophobic fear of being locked in, of not finding a way out.

2.3 False door from an Egyptian tomb, exhibited at the British Museum.

Judeo-Christian mythology is ripe with door rituals and door symbolism. A striking example is the narrative of the first Passover, god’s revenge on the Egyptian people after the mistreatment of the Israelites. The text states that each man should sacrifice a year-old sheep or goat on behalf of his household: ‘Then they shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they eat it’ (Exodus 12:7). In other words, the Israelites smeared the doorframe with blood to strengthen the boundary to the house and signal their origin to the avenging angels. The sacrifice and the ritual sprinkling of blood ensure that the Angel of Death passes over houses belonging to the Israelites during the divine slaughter. The pearly gate, on the other hand, is an example of how the door’s concrete function as a controlling element, allowing or denying entry, is elevated to a mythological level. St. Peter is the gatekeeper to Paradise, allowing only those who are free of sin and have accepted Christ to pass through the gates. Moreover, the most important individual in Christianity likens himself to a door: ‘I am the door; if anyone enters through Me, he shall be saved, and shall go in and out, and find pasture’ (John 10:9).

We continue to use the door as a material articulation of liminality and transformation. When exploring ritual usages of the door in Part III of this book, I am therefore not arguing that the idea of the door as an architectural element with ritual qualities is exclusive to the Late Iron Age. The ritualization of the door is ancient and widespread in space and time. Rather, the fact that door rituals are so widespread may reflect an inherent potential in this particular architectural element, generated by the door’s affective resonance. Thus, the door is an everyday object and technology, and from its everyday function a number of connotations emerge, a point of departure I find significant when exploring the resonance and affect that material culture can evoke across time and space.

A Note on Doors and Structuralism

With a topic such as the door, it is easy to fall into the well-known structuralistic scheme of binary oppositions, e.g. inside – outside, male – female, wild – tame, pure – impure. When structuralism was first applied in post-processual archaeology, it was part of an effort to develop a less functionalistic and more interpretative archaeology. However, in the words of Rachel Pope (Reference Pope, Haselgrove and Pope2007:222), ‘Rather than moving on from functionalism, structuralism merely re-packages much of the processual methodology, with the continuing neglect of the individual in the past’. Bourdieu was likewise criticized for being influenced by structuralism in his work with the Kabyle houses (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1979). He was later self-critical about this point, stating that he wanted to ‘abandon the cavalier point of view of the anthropologist who draws up plans, maps, diagrams and genealogies’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1990:20). Models of pre-Christian cosmology have similarly been constructed with a set of binary oppositions, clearly structuralist in nature (Gurevich Reference Gurevich1985; Hastrup Reference Hastrup1985; Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson1999b) and have rightly been critiqued on those grounds (e.g. Brink Reference Brink, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2004; Pope Reference Pope, Haselgrove and Pope2007).

I do not follow a rigid, structuralist framework in this book. However, it is impossible to ignore that a fundamental aspect of the door is its placement between opposing spaces, between the outside and inside. Moreover, it is conceivable that a divide between settled and unsettled land was pivotal in Iron Age mentalities, due to the importance of the house (Chapter 5). However, rather than mapping out binary opposites onto dynamic and shifting landscapes, my aim is to transcend simplistic structuralist models and rather focus on human agency and material culture as intertwined: constituting dynamic fields of tension and potential.

Viking Doors

Doors are not only affective structures embedded with ritualized connotations; they are also everyday material technologies, and these two capacities of the door are inextricably linked. Turning now from the atmospheric and affective to the concrete and mundane material, the question I want to ask before we embark on Part II of the book is: What do we actually know of these everyday constructions in the Scandinavian Late Iron Age? Because houses from the period are often excavated in the plough zone, as well as the fact that preservation conditions for wood and other organic material are poor, limited material on the door constructions themselves exists from this period. Doors are usually observable in the archaeological record only as negative imprints in the form of post holes or gaps in wall trenches. Chapter 4 will use these ‘shadow-doors’, i.e. door posts, openings in wall trenches, or paved entrances, to explore physical parameters such as the size and number of doorways in the Norwegian corpus, and subsequently consider how these entryways generated movement and encounters within the house. The intent of this section, however, is to synthesize other sources that provide insights into the technology, appearance, and affective aspects of the Viking door to provide a status quo before Chapter 4’s presentation of doors from the corpus of dwellings from Norway. By comparing the few preserved doors that have been unearthed, and by including in brief doors from iconography and later medieval doors, we can attain a fairly detailed picture of the technology and appearance of the door in the Late Iron Age.

Scholarship on doors from Iron Age and medieval Scandinavia has occurred sporadically, but is in general descriptive (Gjærder Reference Gjærder1952; Grieg Reference Grieg1958). Although rarely cited, a symbolically oriented article by Monsen (Reference Monsen1970) foreshadows some of the material on the ritualization of the door that is referenced in the present work. Other researchers have also noted, albeit usually briefly, how doors may have been ritualized in Late Iron Age Scandinavia. Birgit Arrhenius (Reference Arrhenius1970) and Anders Andrén (Reference Andrén and Andrén1989, Reference Andrén1993) have discussed how Gotlandic picture stones may be representations of doors, as detailed later. Several scholars have briefly noted a concurrence between the two texts mentioned in the introduction to this book, ibn Fadlān’s Risãla and the episode from Flateyjarbók (see ch. 6), yet without going into detail (Andrén Reference Andrén and Andrén1989; Price Reference Price2002:168, 218–219; Steinsland and Vogt Reference Steinsland and Vogt1981). Hedeager (Reference Hedeager2011:131) also briefly connects ibn Fadlān’s reported door ritual with figural gold foils deposited in postholes of high status settlements, and with the general liminal nature of doorframes. A recent study is the unpublished thesis of Anna Beck (Reference Beck2010) and two subsequent articles (Reference Beck2011, Reference Beck, Kristiansen and Giles2014), which consider entrances in certain regions of south Scandinavia; Beck’s work is used comparatively in Chapter 4 in particular.

The Archaeological Material: Reconstructing the Door

Seven doors and one doorframe have been preserved from Late Iron Age contexts in Scandinavia, in addition to one Early Iron Age door. Most of the preserved doors and door remains are from early urban sites. This may bias the material – doors from urban sites, which are potentially seasonal, may differ from permanent, rural doors. The doors are constructed in generally similar ways. The oldest door, from Nørre Fjand (second century BCE to second century CE), was composed of two planks of oak joined by means of two curved inlets. The door was probably hinged from a wood-peg, as one of the corners of the plank door was carved into a tenon (Hatt Reference Hatt1957:61–63). From Gotland, a sixth-century door was found collapsed immediately inside the threshold of a longhouse. The door consisted of three pine planks with two transverse crossbeams nailing the three planks together (Stenberger Reference Stenberger1940). One door is preserved from Kaupang, the Viking proto-urban centre in Vestfold.1 This door was reused as framing in a wood-framed well or latrine. It had a rounded shape, and originally consisted of four planks with a transverse beam nailing the planks together with five wooden nails. The door is composed of several types of wood: The planks were pine, oak, and fir. This may indicate that the door was crafted from available wood sources, and thus not particularly planned or meticulously crafted (Figure 2.4).

2.4 Preserved door from the Viking town of Kaupang, Norway.

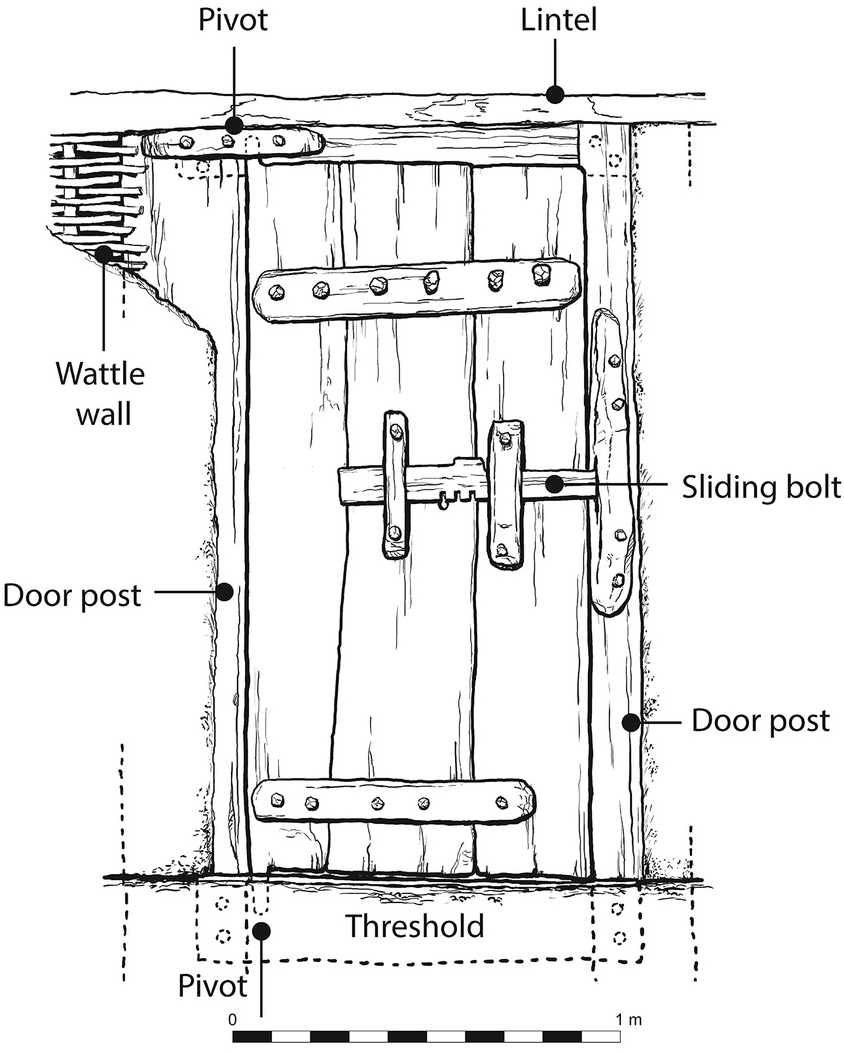

Two doors and a doorframe have been preserved from Hedeby (Schietzel and Zippelius Reference Schietzel and Zippelius1969). The first door consisted of three wooden planks, again fastened together with two transverse crossbeams, of a rectangular shape. The door had a sliding bolt on the upper part, which could be used to lock the door from the inside. The second door was only half a metre wide, and consisted of two wooden boards nailed together by two transverse pieces of wood (Schultze Reference Schultze2010). Both doors must have opened inwards towards the interior, due to the placement of the sliding bolt and the hinges. In addition to the two preserved doors, parts of a doorframe with a rounded lintel were also unearthed at Hedeby (Rudolph Reference Rudolph1939). Figure 2.5 displays a reconstruction drawing of the completely preserved Hedeby door, showing the technology of the construction.

2.5 Reconstruction drawing of the complete door found in Hedeby.

Finally, door constructions are also known from the Viking diaspora, from the hybrid architectural traditions of Dublin. A timber plank door probably swung outwards, based on the placement of its tenon. A second door was made of wattle, making it more portable than a plank door (Wallace Reference Wallace1992:29–30). In addition to the doors, on Fishamble Street an ornamented ship’s prow was found to have been reused as a rather beautiful threshold (Lang Reference Lang1988:9).

Depictions of Doors

Iconographical depictions of doors can be relevant to the study of both the technical aspects of doors and how doors were perceived in Viking mentalities. A handful of iconographical depictions of houses and doorways survive from the Late Iron Age. I will begin with a compelling artefact type directly linked with the door itself. Circa 450 picture stones are known from the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. Type C stones, dated to 800–1000 CE, are traditionally interpreted as memorial stones in honour of the dead (Andrén Reference Andrén1993). However, recent excavations reveal that they can also function as highly striking burial markers (Andreeff Reference Andreeff and Karnell2012). The stones’ ornamentation frequently includes scenes of ships, animals, battles, armed riders, and women with drinking horns. The type C stones are also particularly shaped, sometimes referred to as mushroom- or keyhole-shaped (Figure 2.6). This form has been interpreted as phallic; however, Arrhenius (Reference Arrhenius1970) connected the shape with another famous artefact from the Viking Age: the Urnes stave church portal (see Figure 2.10). The close parallel between the keyhole shape of the Urnes portal and the Gotlandic picture stones, as well as their placement in boundary zones, and their mythologically charged iconography, has led to an interpretation of the stones as ‘doors to other worlds’ (Andrén Reference Andrén1993). I will return to the Gotlandic picture stones repeatedly as the book unfolds.

2.6 Picture stone from Lillbjärs, Gotland, Sweden, ‘keyhole’ shaped.

The Sparlösa rune stone, from Västergötland, Sweden, is dated to c. 800 CE (Nordén Reference Nordén1961). The runic inscription carved on the stone is debated amongst runologists and will not be discussed here. However, the upper part of the stone displays a depiction of a small, decorated building with a large, accentuated door-ring placed on a rectangular portal (Figure 2.7a). The building does not resemble buildings intended for dwelling, and may depict a king’s hall or a hov, a separate cult building.

2.7 (a). Building with rectangular door and large door ring depicted on Sparlösa runestone.

(b) Small building with rectangular door depicted on the Birka coin. (c) On top of what has been interpreted as a magical practitioner’s staff, a small bronze house has been attached.

Furthermore, a silver coin from Birka, an urban settlement in southern Sweden, has a depiction of a small monumental building carved on the adverse (Lindqvist Reference Lindqvist1926). A loop is attached to the coin, indicating that it hung on a cord and was worn, perhaps, on the body. The coin was found in an early ninth-century burial, and similar finds have been interpreted as amulets (Audy Reference Audy2011). The building, reminiscent of the house depicted on the Sparlösa rune stone, has two animal heads attached to the gables. The roof is curved and the walls seem to be convex – a prototype Viking house. The door is centrally placed and rectangular (Figure 2.7b).

Another somewhat charged object is the Klinta staff, discovered in a cremation grave on Öland in 1957. The iron staff is c. 80 cm long, with a broken end. On top of a flat bronze plate, a miniature house of bronze is formed, probably of a Trelleborg-like type (Figure 2.7c). Each of the two longwalls has a centrally placed door. Originally, four animals were attached to the corners of the bronze plate, surrounding the house, but only one animal was preserved at the time of excavation (Andersson Reference Andersson2007). The staff has been interpreted as an attribute of a vǫlva – a religious specialist or sorceress (Price Reference Price2002). I find it intriguing that the house should be used as ornamentation on a magical practitioner’s staff.

Finally, the hogback stones of the British Isles constitute an intriguing group of artefacts (Figure 2.8). Memorial monuments, probably originally used as burial markers, they are mainly found in northern England and central parts of Scotland – roughly in the area that constituted Northumbria in the medieval period – with additional single finds in Ireland, Wales, and southwestern England (Lang Reference Lang, Hawkes, Campbell and Brown1984). The name ‘hogback’ alludes to the convex shape of the roofline of the stones, making the stones resemble animal bodies. However, they are simultaneously shaped in such a way that they are meant to evoke Scandinavian-style longhouses or halls. The hogbacks belong to a short time-span in the tenth century when they became immensely popular for a limited period, perhaps as little as fifty years (Lang Reference Lang, Hawkes, Campbell and Brown1984:97). Many of the hogbacks have two beasts, seemingly bears, holding onto (or attacking) the short-ends of the longhouse-shape, underlining a link with the animal realm. Intriguingly, this is somewhat reminiscent of the two animals used as gable end heads on the Birka coin, and the four animals originally surrounding the Klinta house. Five stones may be interpreted to display stylized rounded doorways. All stones in this group have two end-beasts grasping the gables, and usually three panels of knots and interlace above the niche. As grave markers, the hogbacks probably constituted metaphorical and material houses for the dead – an ‘inhabited mortuary space’ (Williams Reference Williams2016).

2.8 The hogbacks allude to Scandinavian longhouses. Some, such as Brompton 7, display a stylised rounded doorway.

Medieval Doors