This chapter sets forth the theoretical and methodological approach of the book. The underlying assumption is that the study of the EP as an accountability forum needs to be situated in the specialised literature in public administration (on accountability) and political science (on legislative oversight). After all, the EP is a legislative body with powers of scrutiny over EU executive actors in the EMU. Throughout the chapter, the terms ‘legislative oversight’ and ‘parliamentary scrutiny’ are used interchangeably to denote a political accountability relationship between legislatures and executive actors with an ex post focus on past government activities. By contrast, ‘public accountability’ is a broader term that includes all mechanisms – electoral, legal, and administrative – through which public sector actors are required to justify their conduct in front of a higher authority and potentially face sanctions (Reference MulganMulgan 2000a: 555).

Accordingly, the chapter starts with the introduction of the concept of accountability, which became popular in political discourse and public administration starting the 1970s (Reference Dubnick, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansDubnick 2014: 28). Next, the chapter narrows down on accountability as the relationship between an account-giver (an ‘actor’) and an account-holder (a ‘forum’), where the latter has the right to ask questions and receive answers regarding the activity of the former (cf. Bovens 2007). This narrow focus on discursive interactions is explained by the types of accountability relationships existing between the EP and executive actors in the EMU – for instance, the Monetary Dialogue, the hearings on banking supervision, or the Economic Dialogues (see Chapter 2.2.2). Since the EP lacks clear sanctioning mechanisms vis-à-vis executive actors in the EMU, it makes little sense to consider accountability as punishment (for a discussion of the topic, see Reference Mansbridge, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansMansbridge 2014). Conversely, the interest here is in accountability exchanges between legislative and executive actors, which require a theoretical anchor in legislative oversight studies in political science. While oversight has been extensively theorised through the lens of principal–agent theory, the assessment of its effectiveness in practice is more complicated – especially when it comes to the analysis of discursive interactions between parliaments and executive actors.

Against this background, the chapter emphasises the importance of parliamentary questions in legislative oversight and the need for a systematic framework to examine their effectiveness. The idea is that the study of parliamentary questions (Q) needs to be connected to their respective answers (A) and examined together (Q&A) at the micro level as an exchange of claims between legislative and executive actors. Drawing on principal–agent theory, the public administration literature on accountability, and communication research, the chapter offers a step-by-step guide for qualitative content analysis of Q&A that can be applied to different legislative oversight contexts at different levels of governance – not just to the EP. It is argued that the effectiveness of Q&A depends on the strength of the questions asked and the responsiveness of answers provided, which are correspondingly operationalised. The two dimensions are then developed into six possible scenarios of oversight interactions, ranging from ‘High control’ over the executive (or ‘responsiveness’ to the accountability forum) to ‘No control’. Coming back to the EMU, the chapter formulates theoretically-informed expectations about the potential accountability interactions between the EP and the four EMU executive actors selected for empirical investigation: the ECB, the Commission, the ECOFIN Council, and the Eurogroup (see Chapter 1.4). The final section puts forth the methodological considerations of the study, including the coding guide used for the empirical analysis.

3.1 The Concept of Accountability

How do we know if an actor is being held accountable in a given context? Where do we draw the line between degrees of accountability in specific cases? In accountability studies, questions of operationalisation and measurement remain a minefield owing to the concept’s vast semantic field – including words such as ‘responsibility’, ‘answerability’, ‘control’, ‘responsiveness’, ‘liability’, ‘transparency’, ‘public ethics’, and so forth (Reference DubnickDubnick 2002, Reference Dubnick, Bovens, Goodin and Schillemans2014; Reference KoppellKoppell 2005; Reference MulganMulgan 2000a). Indeed, the public administration literature abounds in studies that seek to conceptualise accountability (Reference BehnBehn 2001; Reference BovensBovens 2010; Reference Bovens, Schillemans, Goodin, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBovens et al. 2014; Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans 2013; Reference Day and KleinDay and Klein 1987; Reference DubnickDubnick 2011; Reference Dubnick and FredericksonDubnick and Frederickson 2011; Mulgan 2000; Reference Romzek and DubnickRomzek and Dubnick 1987; Reference Schillemans and BusuiocSchillemans and Busuioc 2015). Despite variation in terminology, there is in fact a minimal consensus on some core features of the term. Accountability is generally understood as the relationship between an account-giver and an account-taker, in which the former has to answer to the latter by providing information and justification of conduct (Bovens 2007: 450; Reference LindbergLindberg 2013: 209; Reference PhilpPhilp 2009; Reference Romzek, Dubnick and ShafritzRomzek and Dubnick 1998; Reference SchillemansSchillemans 2013 Reference ScottScott 2000). The two parties of the relationship can have different names: actors and forums (Reference BovensBovens 2007a), accountability holdees and holders (Reference BehnBehn 2001), and accountors and accountees (Reference PollittPollitt 2003). While such relationships exist in both the public and the private sectors, the concept gained wide currency in the democratic lexicon in relation to the importance of imposing controls on the exercise of power by public officials (Reference FlindersFlinders 2011; Reference MulganMulgan 2003; Reference Schedler, Schedler, Diamond and PlattnerSchedler 1999; Reference SchmitterSchmitter 2004). At the same time, accountability relationships involve both individuals and organisations: for example, civil servants accountable to their superiors, public agencies accountable to parliaments, experts accountable to professional bodies, governments accountable to administrative and constitutional courts, and so on (Reference Romzek and DubnickRomzek and Dubnick 1987: 228–229).

A common position in the public administration literature is that accountability is an obligation that can be either mandatory, required by law, or voluntary, a deliberate choice of the account-giver to provide information and justify conduct, usually in order to improve legitimacy (Reference Bovens, Schillemans, Goodin, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBovens et al. 2014: 12; Reference Busuioc and LodgeBusuioc and Lodge 2016: 253–255; Reference Koenig-ArchibugiKoenig-Archibugi 2004: 245–246; Reference KoopKoop 2014). Research on the adequacy of mandatory accountability is far more prevalent in the specialised literature, taking into consideration the connection with democracy and its inherent requirement for public officials – whether elected or not – to be accountable to a higher authority (Reference DowdleDowdle 2006; Reference MulganMulgan 2003; Reference Przeworski, Stokes and ManinPrzeworski et al. 1999; Reference Schmitter and KarlSchmitter and Karl 1991: 76). In contrast, voluntary accountability is not legally binding and varies considerably depending on the practices of public organisations (Reference KoopKoop 2014: 569; see also Reference Moore, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansMoore 2014). Mandatory accountability is associated with institutional mechanisms stipulated by law, which are in principle easier to identify and evaluate.

The work of Mark Bovens systematised the study of mandatory accountability by offering a parsimonious definition that could be applied to different contexts and levels of governance (Reference BovensBovens 2007a, Reference Bovens2010; Reference Bovens, Schillemans, Goodin, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBovens et al. 2014). He popularised a mechanistic approach to the term, focusing on the institutional arrangements of accountability and their impact on the behaviour of actors – in other words, accountability as the independent variable (Reference BovensBovens 2010: 957). In his view, accountability referred to a series of institutionalised mechanisms through which actors could be held accountable, ex post facto, by a forum (Reference BovensBovens 2010: 948). The goal of the conceptualisation was primarily descriptive, namely to map institutional arrangements of accountability and identify their (potential) shortcomings (Reference Schillemans, Bovens, Dubnick and FredericksonSchillemans and Bovens 2011). In practice, the analytical focus on mechanisms is never purely descriptive because an independent variable does not make sense in isolation: there is always a dependent variable – in this case the behaviour of actors – that is considered by association. But the emphasis on institutional arrangements narrowed down the scope of accountability research significantly.

Furthermore, Bovens put forth a sequential understanding of accountability relationships in which he distinguished between three stages. First, the actor must be under a formal or informal obligation to render account – translated into the regular disclosure of information about its activities (the ‘information stage’). Second, the forum must have the capacity to ask questions regarding the conduct of the actor, demanding further information and/or justification for certain decisions (the ‘debate’ or ‘discussion stage’). Third, the forum must be able to pass judgement on the behaviour of the actor, using sanctions when considered appropriate (the ‘consequences stage’) (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 451–452; Reference Schillemans, Bovens, Dubnick and FredericksonSchillemans and Bovens 2011: 5). Elsewhere, the stages are described as ‘analytically distinct phases’ (Reference SchillemansSchillemans 2013: 13) or as ‘a heuristic device’ that helps organise research on accountability by pointing out deficiencies in one of the stages (Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans 2013: 956).

As any heuristic, the idea of stages impacts the operationalisation of accountability. If the term is defined as a sequence of institutionalised mechanisms, then the evaluation of accountability will start by examining the presence or absence of those stages (Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans 2013). Next, the assessment will zoom in on individual stages with the goal to identify institutional inadequacies: there can be either too many or too few accountability mechanisms in a given setting (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 462). Empirically, this analytical focus assumes an investigation of accountability procedures and their functioning, which can be more quantitative or qualitative depending on the methodological orientations of the researcher. But regardless of methods, the lack of accountability is similarly explained in terms of institutional overloads or deficits that can only be fixed if the right balance of mechanisms is found for every context (Reference Bovens, Schillemans, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBovens and Schillemans 2014: 677–679). The key question is whether there are appropriate measures to ensure accountability at every stage.

In Bovens’s writing, the question whether actors ‘behaved in an accountable way’ (Reference Bovens, Schillemans, Goodin, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBovens et al. 2014: 8) is actually secondary. He argues that depending on the effects of different mechanisms, accountability can be evaluated from a democratic, constitutional, or learning perspective. First, democratic accountability is assessed in principal–agent terms, asking to what extent principals can exercise control over agents in the institutionalised chain of delegation from voters to elected representative to executives to bureaucracies. Second, constitutional accountability is analysed from a legal and administrative viewpoint, looking at courts and chambers of auditors in order to examine whether an actor has abused its power or mismanaged funds in any way. Third, the learning perspective of accountability focuses on public performance reviews centred on stakeholder and public account-giving, weighing the appropriateness of the incentive structure, which allows actors to learn from and correct past mistakes in order to provide greater societal outcomes (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 463–466). There are implicit normative assumptions behind each perspective, as accountability is expected to enhance the legitimacy of an actor via ‘democratic control’, by ‘preventing the development of dangerous concentrations of executive power’, or by ‘making governments deliver better public value’ (Reference Bovens, Curtin, ’t Hart, Bovens, Curtin and ’t HartBovens et al. 2010a: 50). The three perspectives can not only complement but also contradict one another: for example, democratic control through electoral politics is at odds with constitutional accountability through judicial processes (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 466). In the end, Bovens deliberately leaves the evaluation of accountability open-ended: it is up to the researcher to choose his/her most preferred theoretical apparatus and understand the trade-offs involved in that choice.

Over time, this approach to accountability became widely employed in empirical research, especially in EU studies (e.g. Reference Bovens, Curtin and ’t HartBovens et al. 2010b; Reference BusuiocBusuioc 2013; Reference Curtin and EgebergCurtin and Egeberg 2008; Reference Harlow and RawlingsHarlow and Rawlings 2007; Reference MarkakisMarkakis 2020; Reference PapadopoulosPapadopoulos 2007; Reference SchillemansSchillemans 2008). The generality of the stages made the approach particularly applicable to the EU’s multi-level system. Indeed, indicators of the ‘information’, ‘discussion’, and ‘consequences’ stage could be identified to a greater or lesser extent within all accountability relationships. What is trickier is to assess individual indicators and take stock of the extent of accountability in a given context. The challenges of that process are discussed in the following pages.

3.1.1 Measuring the Stages of Accountability

When it comes to measuring Bovens’s approach to accountability, indicators for the ‘information stage’ and ‘the consequences stage’ are straightforward. Usually, these are provided in the legal framework of the actor under investigation. In terms of information, indicators refer to periodic self-evaluation reports and testimonies about the performance, results, or processes of the actor (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 451). Sanctions are expected to offer the possibility for redress, providing ‘safeguards against bad government’ (Reference OliverOliver 1991: 23); for instance, the forum could quash or amend the actor’s decisions or take disciplinary measures through rewards, bonuses, termination, or changes of contract (Reference BehnBehn 2001). In addition to indicators measuring legal provisions – which can be limiting because they only assess de jure accountability – there are also ways to capture practices or de facto accountability (Reference BusuiocBusuioc 2009). Such practices include the amount and type of information released by an actor on a regular basis or the informal consequences a forum can impose through public criticism and rebukes (Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans 2013: 955–958). From a methodological perspective, surveys and interviews are useful here. On the one hand, surveys can ask actors detailed questions about the type of information they share and inquire whether forums find this information sufficient (Reference Brandsma, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBrandsma 2014: 148). On the other hand, interviews can add precious details regarding the type of accountability relationship at play and the reasons behind the imposition of sanctions or their lack thereof (Reference BusuiocBusuioc 2013; Reference Yang, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansYang 2014).

By contrast, the discussion stage is much more challenging to capture from an empirical perspective. The reason is related to the nature of the stage: accountability debates are not always public, and even when they are, discursive interactions are naturally open to qualitative interpretation. One pertinent attempt to investigate the ‘discussion stage’ has been made by Reference BrandsmaBrandsma (2013, Reference Brandsma, Bovens, Goodin and Schillemans2014) and Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans (2013), who proposed to examine the ‘intensity’ of discussions. Intensity refers to ‘the extent to which an actor’s behaviour is discussed with her afterwards’ (Reference Brandsma, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansBrandsma 2014: 150) and whether ‘a message [is getting] across through an exchange of views’ (Reference Brandsma and SchillemansBrandsma and Schillemans 2013: 965). Based on survey material and interviews with participants in accountability arrangements, the authors categorised discussions as being about principles or visions, that is, points of views of either actors or forums (Reference BrandsmaBrandsma 2013: 133). Elsewhere, Reference CarmanCarman (2009) evaluated the interactions between funders and non-profit organisations in the United States and created scales to operationalise various dimensions of those exchanges, for example, external monitoring, descriptive reporting, and evaluation and performance measurement. While both approaches yield valuable results, they are based on participants’ own understanding and post hoc rationalisation of the accountability interaction rather than on the interaction per se.

Examining the actual discussion of the ‘discussion stage’ is difficult because of access to data. Indeed, numerous accountability interactions are never recorded in writing or in a video/audio form. Parliamentary debates offer a rare glimpse into the ‘discussion stage’ by allowing the researcher to explore the dialogue of accountability interactions (Reference Amtenbrink and van DuinAmtenbrink and van Duin 2009; Reference AuelAuel 2007; Reference Eijffinger and MujagicEijffinger and Mujagic 2004). In respect of the EP, one of the most comprehensive analyses of the discussion stage is provided by Reference van de Steegvan de Steeg (2009), who devised a checklist regarding the efficient use of ‘question time’ by MEPs, the clarity of their questions, and the extent to which the actors answered the ‘core’ of the questions posed. Such an approach is essential because it demonstrates how accountability is enacted, that is the ways in which accountability forums use the means at their disposal to hold actors to account and, in turn, how actors respond to this challenge. The point is to go beyond checking whether a ‘discussion stage’ exists on paper and looking into the practice of that accountability relationship by examining the extent to which relevant questions are asked and appropriate answers are provided or investigating differences in interactions over time. Indeed, researchers need a better understanding of the ‘discussion stage’ because it provides a unique angle into the day-to-day implementation of accountability.

When it comes to political accountability, the ‘discussion stage’ overlaps with legislative oversight of executive actors, as shown in the next section.

3.2 Situating the Accountability Potential of Parliaments

In the political science literature on democratic accountability, parliaments occupy a central role for at least two reasons: (1) members of parliaments are accountable to their voters through elections and (2) they are responsible for holding the governments to account through different means (Reference StrømStrøm 2000: 267). This book is concerned with the second dimension, namely the relationship between parliaments (classically seen as legislative bodies) and governing actors (collectively known as the executive). The discussion here covers mainstream political science studies on legislative oversight and principal–agent relations.

3.2.1 Government Accountability and the Role of Parliaments

In the institutional logic of parliaments, the relationship with the executive covers both their elective and controlling functions (Reference von Beymevon Beyme 2000: 72). The elective function refers to a parliament’s power to appoint the executive (Reference BagehotBagehot 1873: 119), which differs depending on the system of government in place. In parliamentary democracies, governments can be voted in and out of office by parliamentary majorities, so they are dependent on the legislature’s support (Reference Müller, Bergman, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and BergmanMüller et al. 2006: 12–13). Conversely, in presidential systems, the head of state is directly elected by citizens for a fixed term; s/he selects members of the cabinet and administration; and together, they operate independently from parliamentary votes of no confidence (Reference LinzLinz 1990: 52). Semi-presidential or mixed systems lie somewhere in-between, but recent research shows that there is actually significant heterogeneity in all three regime types (Reference Cheibub, Elkins and GinsburgCheibub et al. 2014: 528). For accountability purposes, the elective function of parliaments is thus more relevant in some contexts than others.

In contrast, the controlling function – the notion of parliamentary control over the executive – is at the heart of democratic accountability regardless of whether the system of government is parliamentary, presidential, or mixed. The importance of the idea was first articulated by John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century:

Instead of the function of governing, for which it is radically unfit, the proper office of a representative assembly is to watch and control the government: to throw the light of publicity on its acts; to compel a full exposition and justification of all of them which any one considers questionable; to censure them if found condemnable, and, if the men who compose the government abuse their trust, or fulfil it in a manner which conflicts with the deliberate sense of the nation, to expel them from office, and either expressly or virtually appoint their successors.

Nowadays, parliaments are commonly referred to as government ‘watchdogs’ (Reference FrearsFrears 1990), playing a key role in legislative oversight (Reference McCubbins and SchwartzMcCubbins and Schwartz 1984; Reference Ogul and RockmanOgul and Rockman 1990) or the scrutiny of the executive (House of Lords 2011). The terms are often used interchangeably and accepted as part of the established vocabulary of political accountability surrounding executive–legislative relations. In the academic literature, the notion of ‘oversight’ gained traction in the 1970s, in parallel to developments in the US Congress regarding the need to ‘keep a watchful eye’ over the administration after the Watergate scandal (Reference AberbachAberbach 1990).

In legislative studies, ‘oversight’ is conceptualised in an inclusive or restrictive way depending on the number and type of instruments entailed in the process, as well as on the form of control they place over the executive (Reference RockmanRockman 1984: 416–417). A broad definition is provided by Ogul, who describes oversight as ‘behaviour by legislators and their staffs, individually or collectively, which results in an impact, intended or not, on bureaucratic behaviour’ (Reference OgulOgul 1976: 11). His focus is not on the government per se but on the entire administrative apparatus of the state, including civil servants. Harris proposes a narrower understanding: ‘oversight, strictly speaking, refers to review after the fact. It includes inquiries about policies that are or have been in effect, investigations of past administrative actions, and the calling of executive officers to account for their financial transactions’ (Reference HarrisHarris 1964: 9). In relation to legislation in particular, the National Democratic Institute (NDI) portrays oversight as ‘the obvious follow-on activity linked to lawmaking. After participating in lawmaking, the legislature’s main role is to see whether laws are being effectively implemented and whether, in fact, they address and correct problems as intended by their drafters’ (National Democratic Institute 2000: 24). Oversight has thus an important ex post dimension in government action, focusing on the executive’s past conduct in terms of implementing legislation and adopting specific measures.

From a theoretical perspective, the study of legislative oversight became intertwined with principal–agent applications to delegation in representative democracies (Reference Kiewiet and McCubbinsKiewiet and McCubbins 1991; Reference Lupia and McCubbinsLupia and McCubbins 1994; Reference StrømStrøm 2000). In fact, this is how definitions of oversight came to be equated with a parliament’s (mechanisms of) control over the government and the bureaucracy. The principal–agent model is not a theory as much as an approach to delegation dominant in economics, political science, sociology, and policy studies (Reference Braun and GustonBraun and Guston 2003). The bedrock of the approach is the idea that in a representative democracy, ‘those authorised to make political decisions [i.e. citizens] conditionally designate others [i.e. elected politicians, technocrats etc.] to make such decisions in their name and place’ (Reference Müller, Bergman, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and BergmanMüller et al. 2006: 19). The person or group/institution doing the designation is the principal, whereas the person or group/institution acting on the principal’s behalf is called the agent (Reference Lupia, Strøm, Müller and BergmanLupia 2006: 33). Delegation is typically perceived in the form of a chain, with direct links from voters to members of parliament, from members of parliament to governments, from governments to individual ministries and regulatory/implementing agencies, and finally from ministers and agency heads to civil servants (Reference BusuiocBusuioc 2013; Reference MüllerMüller 2000; Reference NiskanenNiskanen 1973; Reference StrømStrøm 2000). This single-chain type of delegation is common in parliamentary democracies, whereas presidential systems have a different model, resembling a grid – with multiple principals (voters in different constituencies) electing multiple agents for the office of the president and parliament, respectively (Reference Strøm, Strøm, Müller and BergmanStrøm 2006: 65).

Against this background, the principal–agent framework introduced accountability as the counterpart of delegation in democratic systems. In fact, when describing electoral accountability, Fearon presents delegation as the necessary condition for accountability, based on the understanding that ‘A is obliged to act in some way on behalf of B’ and, in turn, that ‘B is empowered by some formal institutional or perhaps informal rules to sanction or reward A for her activities or performance in this capacity’ (Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). To put it differently, if delegation is the process through which principals entrust agents with specific tasks, accountability is meant to ensure that the same principals maintain control over their agents. As explained by Lupia:

An agent is accountable to a principal if the principal can exercise control over the agent and delegation is not accountable if the principal is unable to exercise control. If a principal in situation A exerts more control than a principal in situation B, then accountability is greater in situation A than it is in situation B.

Based on this premise, the principal–agent model is concerned with the formal incentive structure through which principals can influence the behaviour of agents and make them act accountably (Reference Gailmard, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansGailmard 2014: 91). The model is based on rationalist assumptions of fixed preferences and self-interested behaviour, operating in an environment of scarce information and a hierarchy of principals over agents (Reference Strøm, Strøm, Müller and BergmanStrøm 2006: 59). These assumptions create automatic problems for accountability because the preferences of principals and agents are bound to diverge over time. Agents are therefore expected to ‘shirk’ their obligations before principals either by hiding information before they are appointed (adverse selection) or by hiding their behaviour while on the job (moral hazard) (Reference MoeMoe 1984: 754–755). In the attempt to control their agents, principals are faced with a decision between the benefits of realising their own preferences and the costs of making the agent act in their most preferred way (Reference Gailmard, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansGailmard 2014: 92). Although there are several variations of principal–agent frameworks applied to accountability, they all share a focus on sanctions and the role of punishment in holding actors accountable (Reference Mansbridge, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansMansbridge 2014: 55–56). The logic is straightforward: sanctions reinstate the principal’s control over an agent and prevent future agency drift.

In respect of accountability, the principal–agent literature describes four different ways to address agency problems. These are: (1) contract design, (2) screening and selection mechanisms, (3) monitoring and reporting requirements, and (4) institutional checks (Reference Kiewiet and McCubbinsKiewiet and McCubbins 1991: 27). The first two operate ex ante (framing the principal–agent relationship), while the other two function ex post, ensuring ongoing oversight of the agent. Kaare Strøm elaborated on the four measures in the context of executive–legislative relations. In his view, contract design refers to ‘the set of terms on which the cabinet is allowed to take office’ (Reference Strøm and Döring1995: 73). Contract terms are to specify not only the shared interests between principals and agents (‘incentive compatibility’) but also the rules by which the agent is to take office (‘investiture rules’) (Reference Strøm and DöringStrøm 1995: 74–75). Screening and selection mechanisms aim to solve the problem of adverse selection by eliminating ‘potentially troublesome’ agents ‘before they ever get into office’ (Reference Strøm and DöringStrøm 1995: 75). Political parties in parliament play a major role in the process of screening, voting, or appointing cabinet members and agency heads (Reference SaalfeldSaalfeld 2000: 356).

Monitoring and reporting requirements overlap most clearly with the legislative oversight instruments mentioned above. Such requirements include committee hearings, questions, audits, special commissioners (‘ombudsmen’), plenary debates, plus the ‘ultimate sanction of the no confidence vote’ in parliamentary regimes (Reference Strøm and DöringStrøm 1995: 75). Elsewhere in the literature, monitoring mechanisms are categorised as (1) proactive and centralised (‘police patrols’) or (2) reactive and decentralised, meaning instruments available at the disposal of those affected in case of necessity (‘fire alarms’) (Reference McCubbins and SchwartzMcCubbins and Schwartz 1984). The centralised aspect of ‘police patrols’ is contested, taking into account that there is no parliamentary-wide, systematic review of government measures; instead, police patrols are decentralised in committees and can often act in response to a scandal inside the executive (Reference Ogul and RockmanOgul and Rockman 1990: 13). Fire-alarm oversight refers to the totality of procedures through which interested third parties (citizens, civil society organisations, and interest groups) can complain directly to the parliament about past or prospective executive measures (Reference SaalfeldSaalfeld 2000: 363).

Finally, institutional checks are safety mechanisms designed to ensure that the decisions of agents are subject to ‘the veto power or other checks exercised by other political agencies’ (Reference Strøm and DöringStrøm 1995: 76). For example, institutional checks and balances encompass judicial review by courts, the division of competences within federal systems, or internal procedures within executives and parliaments. It is important to mention that the range of mechanisms available in principal–agent models cannot eliminate agency loss completely. In fact, it is expected that the very act of delegation presupposes a loss of agency by the principal (Reference Lupia, Strøm, Müller and BergmanLupia 2006: 35). After all, the reason why the principal agreed to delegate specific functions to an agent is because it lacked the necessary information and resources to perform the task by itself. Under the circumstances, the role of accountability is to reduce agency loss, meaning that the conduct of the agent does not drift significantly from the principal’s ideal preferences (Reference StrømStrøm 2000: 275). The interest of principal–agent studies is then to outline game-theoretical models mapping the different choices of principals and agents or, alternatively, to check whether the elements of the model are empirically present (Reference Gailmard, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansGailmard 2014).

Having outlined the theoretical roots of democratic accountability through parliaments, the next question is how principal–agent relations work in practice and how best to investigate them empirically.

3.2.2 Studying Oversight through Parliamentary Questions

Whilst legislative oversight studies might have originated in the American context, the concept can be identified all over the world, with some variation between parliamentary and presidential regimes (Reference StrømStrøm 2000). Typically, the framework for legislative–executive relations is described in constitutions (or equivalent) in relation to the separation of powers, while the details of legislative oversight are stipulated in legislation and/or parliamentary rules of procedures (Reference YamamotoYamamoto 2007). From an organisational perspective, legislative oversight is visible in (1) committee hearings, (2) plenary hearings on specific topics, (3) the creation and functioning of commissions of inquiry, (4) the submission of written questions, as well as the use of in-chamber, (5) ‘question time’, and (5) interpellations (Reference Pelizzo and StapenhurstPelizzo and Stapenhurst 2012: 32–36). The availability and use of different tools depend on the jurisdiction; important factors include the legal framework of executive–legislative relations, the adequacy of parliamentary staff and research capacity, the influence of political parties, and the activity of individual legislators (Reference OgulOgul 1976; Reference Pelizzo and StapenhurstPelizzo and Stapenhurst 2012).

On the whole, oversight tools allow a parliament to make demands of the executive and react to specific policies in writing or orally through reports, speeches, and statements and in direct engagement with the government or civil servants – by asking questions. In fact, the study of parliamentary questions constitutes a field of its own with different areas of focus. In the UK House of Commons, the use of ‘Question Time’ has attracted a lot of attention as a historical development (Reference Chester and BowringChester and Bowring 1962), in terms of why members of parliament ask questions and how (Reference Franklin and NortonFranklin and Norton 1993), and in relation to what type of control over the government can be exercised through questions (Reference ColeCole 1999; Reference GregoryGregory 1990). There is also extensive research on the practices of parliamentary questions in European legislatures with an emphasis on the political behaviour of members who address questions (Reference MartinMartin 2011a; Reference Russo and WibergRusso and Wiberg 2010; Reference Wiberg, Koura and WibergWiberg and Koura 1994).

Although questions are almost always linked to oversight, they carry additional connotations for members of parliament such as self-promotion, acting on behalf of one’s constituency (Reference MartinMartin 2011b), gaining strategic advantages within one’s party, or competing over issues with others (Reference Proksch and SlapinProksch and Slapin 2011; Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave and ZichaVliegenthart et al. 2013). In fact, it is widely recognised that members of parliament ask questions for a plurality of reasons (Reference Wiberg, Koura and WibergWiberg and Koura 1994: 30–31). Furthermore, examining the behaviour of members of parliament driving parliamentary questions contributes to the study of electoral links, government-opposition relations, and intra-party dynamics in legislatures. But although these subjects are fascinating in themselves, they move away from the legislative oversight goal of limiting agency loss through monitoring and reporting requirements (Reference Kiewiet and McCubbinsKiewiet and McCubbins 1991). To put it simply, even if members of parliament ask questions for electoral or career gains, this does not diminish their original ‘oversight purpose’ to control the executive. After all, different motivations can be served through the same question.

From a research perspective, the challenge is to establish when a parliamentary question is effective in achieving the effect of control. So far, this methodological conundrum has been addressed by scholars in two ways. One avenue was to ask members of parliament, through surveys and interviews, whether the use of parliamentary questions has fulfilled their expectations of holding ministers accountable (Reference Franklin and NortonFranklin and Norton 1993). Surveys are helpful in conveying the perceptions of a sample of members of parliament regarding the usefulness of parliamentary questions; however, they risk being under-representative owing to low participation rates (Reference Bailer, Martin, Saalfeld and StrømBailer 2014: 186). Interviews suffer from the same problem to a higher extent, namely the inability to capture whole-of-parliament views about the effectiveness of oversight activities. At the same time, surveys and interviews take a snapshot of participants’ views at a certain moment in time, meaning that findings cannot cover longer legislative periods.

Another popular approach is to conduct content analyses of parliamentary questions, which aim ‘to extract meaningful content from an entire corpus of text in a systematic way’ (Reference Slapin, Proksch, Martin and SaalfeldSlapin and Proksch 2014: 128). Typical investigations include analyses of the frequency of questions on different indicators, such as government department/agency and subject matter (Reference ColeCole 1999) or type of procedure and political affiliation of members of parliament posing questions (Reference Proksch and SlapinProksch and Slapin 2011; Reference Wiberg, Koura and WibergWiberg and Koura 1994). Quantitative content analysis of oral and written questions overcomes the representativeness problem of surveys and interviews; nevertheless, the method cannot capture qualitative aspects about the content of the question in terms of their suitability for oversight.

To sum up, the literature on legislative oversight is rich but simultaneously disjointed. As with many other academic subfields, scholars have been interested throughout time in different aspects of oversight, some theoretical and others empirically driven. When it comes to the study of parliamentary questions in particular, what is currently missing from the literature is a systematic analytical approach for evaluating their effectiveness in achieving control of the executive. The next section introduces such a framework.

3.3 The Analytical Framework: The Q&A Approach to Legislative Oversight

So far, the chapter has established the scarcity of research on the ‘discussion stage’ of public accountability relationships and the problem of measuring the extent to which actors can be held accountable through this stage alone. In respect of political accountability and the relationship between parliaments and executive actors in particular, the ‘discussion stage’ is captured in legislative oversight and the pervasive use of parliamentary questions. From a theoretical perspective, oversight is widely conceptualised in principal–agent terms, but the literature lacks a comprehensive framework for assessing whether parliamentary questions can control the executive and actually hold governmental actors accountable in practice.

To establish the effectiveness of parliamentary questions in the ‘discussion stage’ of political accountability, the approach presented hereFootnote 9 builds on two underlying assumptions. The first is that the study of parliamentary questions cannot be separated from the study of executive answers, keeping in mind that legislative oversight presupposes a discursive exchange between two actors: the legislative and the executive. Following the convention in the literature, the ‘executive’ can refer to cabinet members (including prime ministers/presidents), politically appointed government officials in ministries or agencies, or civil servants in public administration. The legislative can include members of parliament (individually or in groups), a parliamentary committee, or the parliament as a whole. The second assumption is that evaluating the effectiveness of parliamentary questions must be limited in scope; otherwise, researchers risk getting lost in assessing the broader impact of legislative oversight on the political system (Reference RockmanRockman 1984: 430). Indeed, ‘impact’ can mean different things to different people, including but not limited to changes in policy decisions, changes in the attitudes of the executive towards the legislative (e.g. more transparency), or changes in legislative oversight practices (e.g. more hearings). The problem is that such (longer-term) effects can be caused by multiple factors that are not related to parliamentary questions. To avoid the confusion, it is proposed to limit the evaluation of parliamentary questions to their content on the one hand and their corresponding answers on the other hand, that is, the exchange of claims between legislative and executive actors.

Taking into account the emphasis on questions and answers as a discursive exchange, the analytical framework is labelled the ‘Q&A approach to legislative oversight’. Two implications come with the label: (1) that the content of Q&A in oversight interactions is essential and should be analysed in itself and (2) that the exchange of claims between legislative and executive actors is the result of ‘the actual, strategic actions of the claims makers’ (Reference Koopmans and StathamKoopmans and Statham 1999: 216). Indeed, legislative oversight interactions have a certain dynamic dictated by the nature of their relationship, bearing in mind that the legislative has the authority to judge the appropriateness of executive actions, while the executive has to answer to the legislative for its performance (Reference AberbachAberbach 1990; Reference Kiewiet and McCubbinsKiewiet and McCubbins 1991; Reference OgulOgul 1976). Q&A will thus correspondingly reflect the strategic positions of actors towards these goals. Moreover, since legislative oversight is an institutionalised process, Q&A can be found in organised hearings, meetings, and more frequently, the exchange of documents between the two parties. Accordingly, Q&A takes the form of both verbal and written communication.

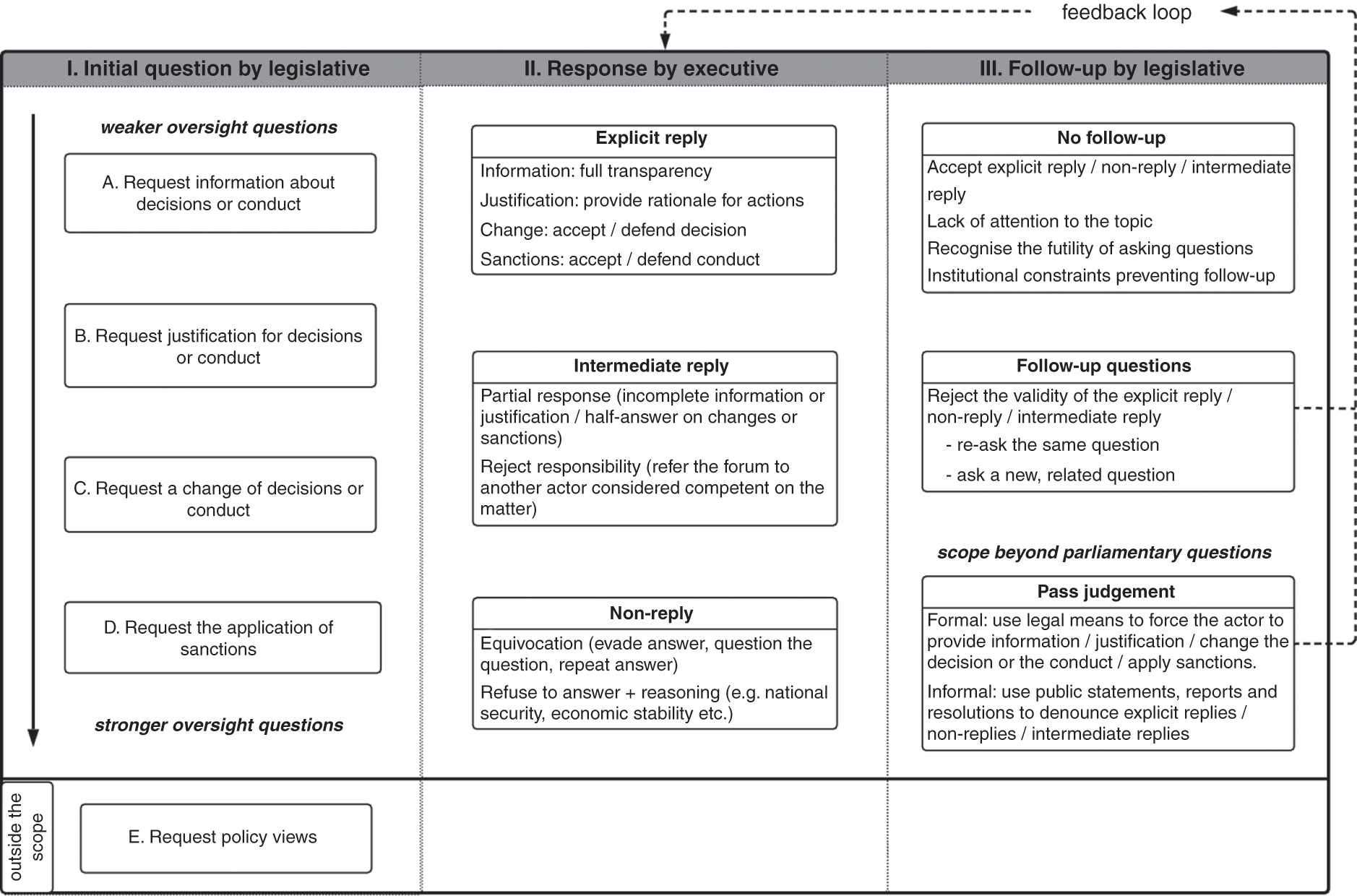

Furthermore, the Q&A approach to legislative oversight puts forth an analytical model entailing (a minimum of) three steps: (1) the legislative asks a question of the executive, (2) the executive provides an answer, and (3) the legislative reacts to that response. If the legislative continues one line of questioning, there is a feedback loop back to the executive’s replies. Portraying Q&A as a three-step process is not random. In a legislative oversight interaction, not only does the legislative ask a question and the executive reply but also there is a back-and-forth that reveals essential information about the dynamics of oversight in a particular setting. Follow-up questions suggest dissatisfaction with the executive’s response, which is why they have to be considered separately from questions asked only once (Reference Sánchez de Dios and WibergSánchez de Dios and Wiberg 2011: 356). Figure 3.1 offers an overview of the framework, which is explained below.

Figure 3.1 The Q&A approach to legislative oversight. Own account

Column I lists the types of questions a member of parliament can ask the executive. Borrowing from the public administration literature, the Q&A approach to legislative oversight connects parliamentary questions to the stages of public accountability – information, discussion, and consequences – envisaged by Mark Bovens (2007; see Section 3.1). The idea is that (1) the actor is obliged to disclose information about its activities on a regular basis, (2) the forum can interrogate the actor about the adequacy of its conduct, and (3) the forum can pass positive or negative judgements on the behaviour of the actor, including through the imposition of sanctions (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 450–451). Technically speaking, parliamentary questions are part of Bovens’s second stage because they constitute only one element of holding actors accountable. However, for the purposes of analysing parliamentary questions, the stages are extremely useful for identifying both the objectives of questions and the degree to which they challenge executive action.

Accordingly, it is posited that the legislative can make four types of requests from the executive: (type A) to provide information about (the context of) a decision; (type B) to justify a decision taken or explain conduct in a given situation; (type C) to amend a decision or change a conduct in a specific or general way; and (type D) to sanction individuals who are considered to be at fault for the negative effects of a decision or conduct. The Q&A approach to legislative oversight distinguishes demands to change decisions from requests for sanctions, keeping in mind that in principal–agent models, sanctions are the ultimate weapon of the principal (Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and ManinFearon 1999). Amendments of decisions can occur without necessarily sanctioning responsible parties for past errors. Overall, applying Bovens’s logic allows the researcher to distinguish ‘weaker’ oversight questions requesting information and justification of conduct from ‘stronger’ oversight questions demanding changes of decisions and the imposition of sanctions. In addition, there is the possibility that the legislative asks a question that is outside the scope of oversight (Figure 3.1, requests of type E). Examples include questions for policy views that do not challenge the executive’s past decisions or conduct in any way. Indeed, not all questions are relevant for legislative oversight purposes.

Next, column II illustrates the categories of answers provided by the executive in response to parliamentary questions. The point here is to establish the extent to which executive actors actually respond to questions, or alternatively, if they ‘evade questions and/or give insufficient responses’ (National Democratic Institute 2000: 38). The classification of answers is borrowed from communication research, specifically the strand dealing with equivocation in political interviews, that is, the ways in which politicians fail to reply to questions and how (Reference BullBull 1994; Reference Bull and MayerBull and Mayer 1993). Peter Bull recently refined his ‘response typology’ for the purposes of analysing ‘Question Time’ with the prime minister in the House of Commons, demonstrating the applicability of his categories for judging executive answers in legislative oversight (Reference Bull and StrawsonBull and Strawson 2020). Following his typology, column II shows that in response to parliamentary questions, the executive can provide (1) an explicit reply, (2) a non-reply, or (3) an intermediate reply.

Explicit replies show full engagement with the substance of questions. For requests for information and justification, this means offering full transparency or providing a comprehensive explanation of the rationale behind a certain decision. Likewise, when responding to requests for changes of conduct or for sanctions, executive actors can accept the request or defend the conduct in question. Explicit replies do not necessarily promise to redress a situation contested by the legislative; it may simply be that the government stands by the contested decision. For example, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Treasury Committee in the House of Commons held a series of hearings with the leadership of the Bank of England to discuss past errors and future reforms (2010–2012). One area of contention concerned the functions of the Court of Directors of the Bank of England, responsible for resource organisation (budget and appointments). In an oral testimony on 28 June 2011, the Governor of the Bank of England, Sir Mervyn King, rejected a suggestion by a member of parliament, Mark Garnier, that the role of the Court of Directors will be to ‘run the Bank of England’; instead, he argued that the Court will ‘not be responsible and should not be responsible for policy’ because the Bank should be fully independent from political interference (House of Commons Treasury Committee 2011: 126). The point of explicit replies is that they address the question head-on, without attempts at subterfuge or by invoking reasons why parliamentary requests cannot be met.

Second, if the executive provides a non-reply, it can do so in two ways. One is equivocation, which can mean evading an answer, questioning the question, or repeating a previous response (Reference Bull and StrawsonBull and Strawson 2020: 10–11). In the same hearing from June 2011, the Governor of the Bank of England evaded a question from a member of parliament, Andrea Leadsom, who contested the extent to which the Court of Directors reviewed the Bank’s handling of the financial crisis. Instead of answering the question, Sir Mervin King claimed that the Treasury Committee actually fulfilled that function by conducting ‘a permanent standing public inquiry into the financial crisis’ (House of Commons Treasury Committee 2011: 129). Attention was thus deflected from what the Court should have done to the direct flattery of the Treasury Committee. The other category of non-replies concerns a clear refusal to reply accompanied by a rationale, which in legislative oversight could refer to national security, economic stability, or executive actions that require secrecy. In the same hearing with the Governor of the Bank of England, a member of parliament, George Mudie, asked for ‘one time, one action’ when the Bank changed its conduct because the ‘Committee came across strongly on a given issue’. Sir Mervyn King answered, ‘I sincerely hope that there was no action that we took that was as a direct result of what you have said because that would be to compromise [our] independence’ (House of Commons Treasury Committee 2011: 131). In this context, we see that central bank independence is considered a sufficient rationale for not complying with requests for change of conduct in legislative oversight.

Finally, intermediate replies lie in-between explicit and non-replies. Some intermediate replies are just partial responses, providing incomplete information and justification or only half-answering requests for changes and sanctions (Reference Bull and MayerBull and Mayer 1993: 660). In the above-cited hearing, an intermediate reply is provided by the Governor of the Bank of England when he acknowledges that it is essential to delineate clearly the role of the Court of Directors, but that this should be done by the legislators (House of Commons Treasury Committee 2011: 125–126). A second type of intermediate reply concerns instances of rejecting responsibility for the matter because it is not within the competence of the executive actor questioned. In the example above, Sir Mervin King replies to questions regarding mistakes done prior to the financial crisis in banking supervision by referring to the Financial Services Authority, which was responsible for prudential supervision and financial (mis-)conduct during the crisis. These situations should be investigated further because they can include cases of blame-shifting or avoidance of oversight (Reference HoodHood 2010). If the question was indeed asked of the incorrect addressee, the reply is still considered ‘intermediate’ because the legislative does not receive a full response; however, the situation is not the fault of the executive actor under consideration.

In a third step (column III), the legislative reacts to the response of the actor by (1) providing no follow-up, (2) asking follow-up questions, or (3) passing judgement on the actions of the executive. The reaction of the forum as ‘no follow-up’, ‘follow-up’, and ‘passing judgement’ can occur regardless of whether the request was for information, justification of conduct, changes of policy, or the application of sanctions. The lack of follow-up can have different reasons, which are often hidden to the observer because they concern the personal motivations of legislative actors. Accordingly, a lack of follow-up can mean that the legislative is satisfied with the answer of the executive, that public attention has moved away from the topic, or simply that the legislative is aware that a complete answer will never be provided – in the case of non-replies and intermediate replies. Moreover, not all parliamentary systems allow members to ask follow-up questions orally; this depends on each assembly’s rules of procedure, which can create institutional constraints that prevent follow-up altogether. Follow-up questions occur for all categories of responses: explicit replies (when the legislative seeks additional information about the issue), non-replies (when the legislative rejects the lack of answer and restates the question), and intermediate replies (when the legislative seeks a full answer either by re-asking the same question or demanding additional information).

The final category of follow-up reactions, namely the ‘passing of judgement’ (cf. Reference BovensBovens 2007a), goes beyond the scope of Q&A in legislative oversight. In fact, members of parliament use other parliamentary tools – not questions – to express positive or negative assessments of the executive’s conduct. Such tools can be formal, for example, legislative acts that force the executive’s hand in some respect, and also informal, when legislatures criticise or approve the executive’s response in public statements, reports, and resolutions (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 452). The challenge is to establish the extent to which these other forms of follow-up are linked to specific parliamentary questions. In the end, the decision to include the ‘passing of judgement’ in an analysis of Q&A is an empirical question to be settled by researchers on a case-by-case basis.

3.3.1 Six Scenarios of Oversight Interactions

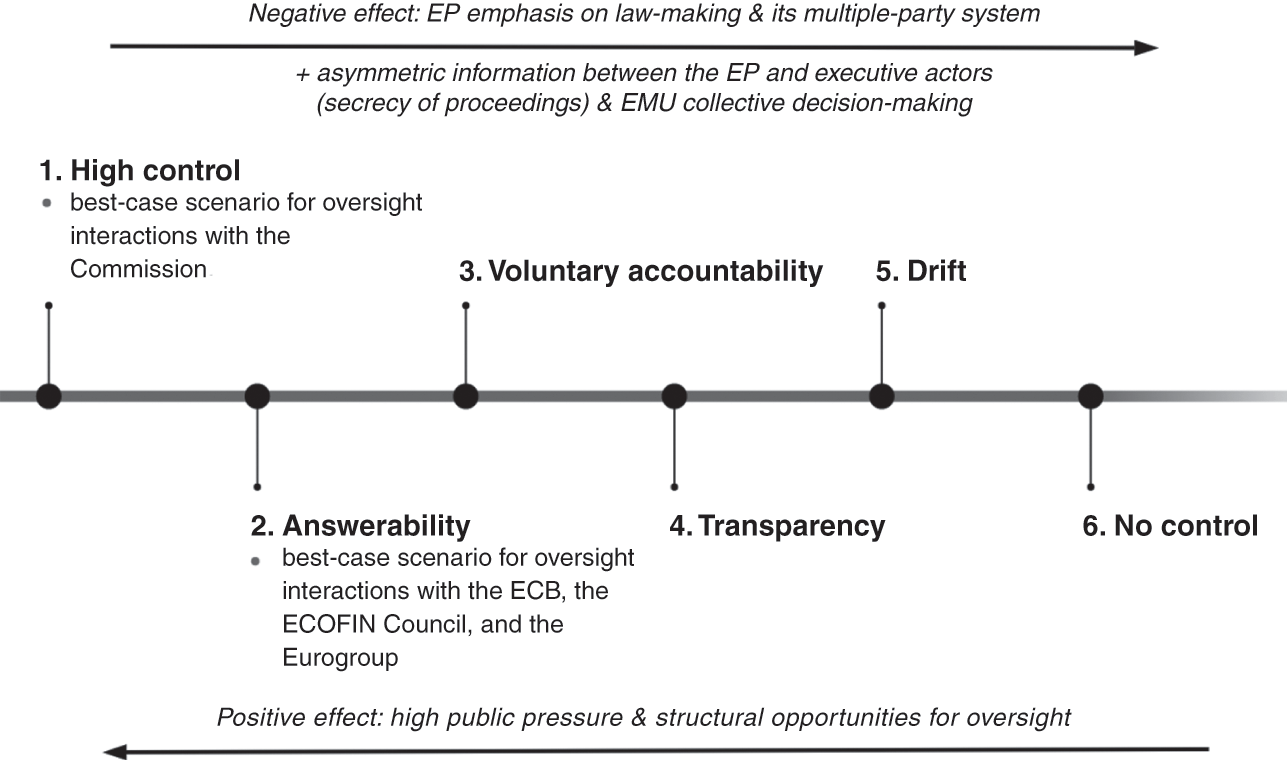

Having established the main categories of Q&A, the next step is to evaluate their effectiveness. Following principal–agent insights, the purpose of oversight is to ensure legislative control of the executive (Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and ManinFearon 1999; Reference Lupia and McCubbinsLupia and McCubbins 1994; Reference StrømStrøm 2000; see Section 3.2.1). This book puts forth six scenarios capturing different dynamics of principal–agent control – or its lack thereof. Two criteria are considered: one concerns the type of questions asked by the legislature, and the other refers to the responsiveness of the executive actor providing the answer. In line with the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, requests of type A (for information) and type B (for justification of conduct) are considered ‘weaker’ oversight questions, whereas requests of type C (for change of conduct) and type D (for sanctions) are seen as ‘stronger’ oversight questions. In respect of the responsiveness of the executive, three patterns are possible: the actor accepts the legislative’s requests for change of conduct or sanctions and promises to do better in the future (rectification); the actor explains or defends its decisions without promising any changes (justification); or the actor evades answering altogether, dodging the question from the legislative (equivocation).

Accordingly, the effectiveness of parliamentary questions is operationalised in terms of (1) the strength of questions raised for the purposes of oversight and (2) the extent to which the executive is ready to justify and, if needed, rectify its behaviour in front of members of parliament. Justification and rectification are intrinsic in many definitions of public accountability (Reference MulganMulgan 2000b), taking into account the expectation that the actor will explain and, if necessary, make amends for past errors of judgement (Reference OliverOliver 1991: 28). In the Q&A approach to legislative oversight, justification and rectification correspond to ‘explicit replies’ and are categorised depending on the emphasis of the answer – either to explain/defend behaviour or promise to correct ill-conceived decisions. Conversely, equivocation is borrowed from communication research (Reference Bull and MayerBull and Mayer 1993) and can be identified under ‘non-replies’ in Figure 3.1. Table 3.1 provides a summary of the interactions between the two dimensions, creating six scenarios of legislative oversight.

Table 3.1 Six scenarios of legislative oversight

| How does the actor respond to the question? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Through rectification | Through justification | Through equivocation | ||

| Types of questions asked as part of oversight | Stronger (types C and D) | (1) High control/responsiveness | (2) Answerability | (5) Drift |

| Weaker (types A and B) | (3) Voluntary accountability | (4) Transparency | (6) No control | |

The numbering of the scenarios illustrates their placement on a continuum from ‘(1) High control/responsiveness’ to ‘(6) No control’. The order of the in-between scenarios is complicated by the strength of parliamentary questions. Specifically, scenario ‘(2) Answerability’ indicates a higher degree of legislative control over the executive than ‘(3) Voluntary accountability’ because rectification in the absence of strong requests for changes of conduct/sanctions is entirely dependent on the benevolence of the executive. Conversely, scenario ‘(4) Transparency’ denotes a higher degree of legislative control over the executive than ‘(5) Drift’ because a transparent executive that addresses requests for information/justification illustrates a higher degree of legislative control than an executive that evades strong parliamentary questions altogether.

Under what conditions is each scenario more likely? The legislative oversight literature offers no encompassing explanation of the reasons behind cross-national and cross-temporal variation in the strength of parliamentary questions (Reference Rozenberg and MartinRozenberg and Martin 2011: 402–403). Based on empirical studies, we have, however, some indication of the institutional settings and legislative–executive constellations that increase the likelihood of stronger questions (types C and D). First, public pressure on an issue is essential for legislative oversight, regardless of whether it is triggered by ‘fire alarms’ (Reference McCubbins and SchwartzMcCubbins and Schwartz 1984), constituency demands (Reference MartinMartin 2011b), or general media scrutiny that allows members of parliament to build a reputation (Reference Wiberg, Koura and WibergWiberg and Koura 1994). Second, there are structural opportunities such as the oversight mandate of the legislative, the institutional procedures available to ask questions in committee or plenary meetings, and adequate staff resources supporting members of parliament in asking strong questions (Reference OgulOgul 1976; Reference RockmanRockman 1984). In this respect, parliamentary systems have on average a greater capacity for oversight than semi-presidential and presidential systems (Reference Pelizzo and StapenhurstPelizzo and Stapenhurst 2012: 52). Third, there is the relative strength of various functions played by parliaments, namely ‘law-making’, the ‘ex ante [s]election of officeholders’, and ‘the ex post control of the cabinet’ (Reference SiebererSieberer 2011: 731; for a general index of parliamentary powers, see Reference Fish and KroenigFish and Kroenig 2009). It can thus be expected that legislatures with strong law-making powers are less likely to prioritise parliamentary questions than legislatures with strong elective and control powers (Reference SiebererSieberer 2011). Fourth, single-party cabinets tend to face more effective questioning procedures than coalition governments because the latter have a lower potential for confrontation (Reference Russo and WibergRusso and Wiberg 2010). In summary, we can expect stronger oversight questions under the following conditions:

(1) High public pressure on an issue

(2) Multiple structural opportunities for legislative oversight in settings where…

(3) Parliaments have stronger elective and control functions rather than law-making powers, while

(4) Cabinets are led by single parties rather than coalitions

At the same time, the incidence of follow-up questions has an additive effect – as suggested in Section 3.3 – meaning that more follow-up questions are also an indicator of strong oversight by a parliamentary forum.

Furthermore, the oversight literature offers some clues regarding the likelihood for rectification, justification, or equivocation in response to questions. Rectification as ‘(1) High control/responsiveness’ can be anticipated in parliamentary systems where there is a direct chain of delegation between parliaments and cabinet members (Reference StrømStrøm 2000). In contrast, rectification as ‘(3) Voluntary accountability’ can be expected from independent agencies that seek self-legitimation in different systems, especially when dealing with politically salient issues (Reference KoopKoop 2014; Reference Schillemans and BusuiocSchillemans and Busuioc 2015). Next, justification as ‘(2) Answerability’ or ‘(4) Transparency’ is applicable to a wide range of legislative–executive interactions regardless of the system of government; nevertheless, the two scenarios are more likely when parliaments and governments are in an indirect principal–agent relationship in which the focus is on account-giving rather than control (Reference BovensBovens 2007a). Examples include legislatures and independent agencies in parliamentary systems (Reference ThatcherThatcher 2005) or legislatures and cabinets in presidential systems (Reference AberbachAberbach 1990; Reference StrømStrøm 2000).

Finally, equivocation in the form of ‘(5) Drift’ or ‘(6) No control’ can be predicted in two contexts. First, under conditions of asymmetric information between legislatures and bureaucracies/expert agencies, there is a higher chance that executive actors will ‘explain away’ the questions raised in any system of government (Reference Lupia and McCubbinsLupia and McCubbins 1994; Reference MoeMoe 1984). Second, when collective decisions by multiple actors cannot be disentangled, the potential for blame-shifting increases exponentially (Reference Hobolt and TilleyHobolt and Tilley 2014; Reference HoodHood 2010). Table 3.2 provides an overview of these expectations in connection to the conditions for stronger oversight questions outlined above.

Table 3.2 Institutional settings of legislative oversight scenarios

| Institutional settings (constellation of legislative–executive relationships) | Public pressure | Structural opportunities for oversight | Focus of parliamentary powers | Single-party vs coalition government |

| (1) High control/responsiveness | ||||

| High | Many | Select and control the executive | Single-party government |

| (2) Answerability | ||||

| High | Many | Select and control the executive | Single-party government |

| (3) Voluntary accountability | ||||

| High | Fewer | Law-making | Coalition government |

| (4) Transparency | ||||

| Medium | Fewer | Law-making | Coalition government |

| (5) Drift | ||||

| Medium | Many | Select and control the executive | Single-party government |

| (6) No control | ||||

| Low | Fewer | Law-making | Coalition government |

Legend: L = legislative, C = cabinet, and B/A = bureaucracy/agencies. Own account based on the literature.Footnote 10

The following pages describe the six scenarios in brief. The first scenario ‘High control/responsiveness’ occurs when parliaments ask stronger questions as part of legislative oversight, requesting the executive to change its decisions or apply sanctions, while the executive answers through rectification, acknowledging that something needs to be changed or sanctions should be applied to the responsible parties. The likelihood for the first scenario to occur increases under conditions of (1) high public pressure on an issue, (2) multiple structural opportunities for legislative oversight (e.g. organisation of ‘Question Time’ sessions, regular or inquiry committee hearings), (3) strong parliamentary powers focused on control of the executive (e.g. Danish, Austrian, or Spanish parliaments), and (4) the presence of single-party cabinets as in the United Kingdom.

The second scenario ‘Answerability’ also occurs when parliaments ask stronger oversight questions, requesting executive actors to change their decisions or impose sanctions, but executive actors answer through justification rather than rectification, that is they focus on explaining their decisions or defending the conduct under scrutiny. ‘Answerability’ is also consistent with a high number of follow-up questions, even if they are requests for information or justification of conduct. In terms of likelihood of occurrence, ‘Answerability’ is expected when (1) public pressure on the executive actor is high, (2) there are multiple structural opportunities facilitating legislative oversight, (3) parliaments have strong powers to control the executive (as opposed to or in addition to law-marking powers), and (4) the party system is conducive to single-party governments that are strongly connected to parliamentary majorities.

The third scenario ‘Voluntary accountability’ occurs when parliaments ask weaker questions as part of legislative oversight, mostly requesting information and justification of conduct from bureaucracies and independent agencies. These executive actors acknowledge on their own the need for rectification and promise to change problematic decisions or sanction individuals found responsible for past errors. The assumption is that bureaucracies and independent agencies suffer from a lack of ‘input legitimacy’ because they are not directly elected, that is, they are non-majoritarian institutions (Reference Thatcher and SweetThatcher and Sweet 2002). Consequently, they can be expected to seek self-legitimation through voluntary means in any system of government but especially when dealing with politically salient issues (Reference KoopKoop 2014; Reference Schillemans and BusuiocSchillemans and Busuioc 2015). The third scenario is thus expected when (1) public pressure on an issue is high, but otherwise, there are (2) fewer structural opportunities for legislative oversight, (3) the parliament has strong law-making powers in a given institutional context (as opposed to strong elective and control powers over the executive), whereas (4) the party system is conducive to coalition governments.

The fourth scenario ‘Transparency’ occurs when parliaments ask weaker questions as part of legislative oversight, focusing on requests for information and justification of conduct from executive actors. For their part, executive actors acknowledge the substance of questions and answer by justifying their decisions or defending the conduct under scrutiny. Similar to ‘Answerability’, this scenario is expected when legislatures and executive actors are not in a direct principal–agent relationship (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 451). Since parliaments cannot control governments by changing their composition (especially in the case of cabinets) or the legal framework in which they act (especially in the case of agencies or bureaucracies), the legislative–executive relationship focuses on transparency, that is, the exchange of information between the two parties. The scenario is more likely to be encountered when (1) there is moderate public attention given to the issue or the executive actor under scrutiny, (2) there are fewer structural opportunities for legislative oversight, while the institutional context is characterised by (3) parliaments with strong law-making powers, and (4) a multi-party system conducive to coalition governments.

The fifth scenario ‘Drift’ occurs when parliaments ask stronger oversight questions focused on changing decisions and imposing sanctions, to which executive actors respond through equivocation, evading, or failing to address the substance of questions. This scenario follows classic principal–agent expectations regarding legislative oversight, based on assumptions of asymmetric information between parliaments and government agencies with specialised knowledge, which can explain any question away regardless of the system of government (Reference Lupia and McCubbinsLupia and McCubbins 1994; Reference MoeMoe 1984). Moreover, ‘Drift’ is likely to occur in institutional contexts where executive decisions are taken collectively across different agencies or levels of government, thus opening the space for blame-shifting from one actor to another (Reference Hobolt and TilleyHobolt and Tilley 2014; Reference HoodHood 2010). Legislative relationships with bureaucracies and specialised agencies are predicted to fulfil the criteria, as well as multi-level settings that mix decision-making competences, for example, the EU. Moreover, the scenario is expected under the following conditions: (1) a moderate level of public pressure on the executive actor or the issue at stake, (2) multiple structural opportunities for legislative oversight, (3) strong parliamentary powers in respect of controlling the executive, and (4) a party system conducive to single-party governments. The point here is that the legislature has both the means (structural opportunities, direct connections to the government) and the willingness to control the executive, but the latter fails to engage with oversight appropriately.

The sixth scenario ‘No control’ occurs when parliaments ask weaker oversight questions centred on access to information and justification of governing decisions. Yet executive actors equivocate even these questions, avoiding answering or failing to engage substantively with the legislature. Similar to ‘Drift’, this scenario is expected under conditions of asymmetric information and collective decision-making in various institutional settings (Reference Hobolt and TilleyHobolt and Tilley 2014; Reference HoodHood 2010; Reference Lupia and McCubbinsLupia and McCubbins 1994; Reference MoeMoe 1984). Relationships between parliaments and bureaucracies or specialised agencies fall in this category because the latter can exploit the legislature’s knowledge gaps and lack of time/attention to understand complex policy issues (Reference MajoneMajone 1999: 3–4). Moreover, ‘No control’ is facilitated by (1) low levels of public pressure on the executive actor and the policy issues under its jurisdiction, (2) fewer structural opportunities for legislative oversight, (3) a parliamentary tradition focused on law-making rather than selection and control of the executive, and (4) a multi-party system conducive to coalition governments. The point is that parliaments lack both the means and willingness to ask strong oversight questions, whereas executives seek to obscure their conduct or shift responsibility to other actors.

From a normative perspective, the order of the scenarios is consistent with principal–agent expectations regarding the purpose of legislative oversight and accountability more generally, namely to ensure that agents are responsive to the principals that elected/appointed them (Reference Przeworski, Stokes and ManinPrzeworski et al. 1999). However, in some instances, ‘Answerability’ can be as important as ‘High control/responsiveness’ depending on the specificities of the political and organisational setting under consideration (Reference Dubnick, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansDubnick 2014: 33). For example, if governments are seen ‘to do a good job’, then the need for rectification will automatically be weaker than in contexts where executives deviate from legislative intent and hence have to be regularly ‘controlled’. Moreover, there is also the question of whether rectification or executive responsiveness to legislatures is always desirable: for example, independent (regulatory) agencies were delegated to fulfil specific tasks not least in order to be insulated from political changes over time (Reference MajoneMajone 1999: 13–14); in these cases, the justification of executive decisions might be more valuable than their rectification or appearing responsive to parliamentary pressure. The point is that researchers must decide on a case-by-case basis whether ‘High control/responsiveness’ or ‘Answerability’ is the best-case scenario in a given oversight context.

3.3.2 Expectations about the European Parliament in the EMU

Taking into account the literature above, we can formulate several expectations about the accountability relationship between the EP and various executive actors in the EMU. The only caveat is that the vast majority of studies on legislative oversight are based on national parliaments, so it is necessary to make adjustments to the variables identified in order to fit the characteristics of the EP in EU multi-level governance and the EMU specifically.

First, given the structure of the EU political system, the interactions between the EP and the Commission come closest to the relationship between a legislative and a cabinet in parliamentary systems. According to Articles 14(1) and 17(7) TEU, the EP elects the Commission President and votes on the College of Commissioners as a whole; in addition, MEPs can initiate a motion of censure and dismiss the current Commission, in line with Article 17(8) TEU and Article 234 TFEU. While there are caveats to the chain of delegation in place – for example, the European Council appoints a candidate for Commission President (not the EP) – we can still expect the highest level of political accountability from the College of Commissioners who earn their jobs (and can subsequently lose them) as a result of a plenary vote in the EP. Based on this logic, the best outcome for the oversight relationship between the EP and the Commission is ‘High control/responsiveness’ (scenario 1).

Conversely, the interactions with intergovernmental bodies (the ECOFIN Council and the Eurogroup) are different because Member States’ governments are formally accountable to their respective national parliaments and citizens, not to the EP (Article 10 TEU). For this reason, the oversight dynamic between the EP and the Council comes closest to the relationship between a legislature and a cabinet in a presidential system, where the executive is directly accountable to citizens. Under the circumstances, such relationships are unlikely to be characterised by ‘High control/responsiveness’ (scenario 1). Consequently, the best outcome for the oversight relationship between the EP and the ECOFIN Council/the Eurogroup is ‘Answerability’ (scenario 2).

The same expectation can be formed regarding the interactions between the EP and the ECB (the other main executive actor in the EMU) but for different reasons. Given the political independence of the ECB – stipulated in the Treaties (Article 130 TEU) – we can envisage a dynamic similar to the one found between legislatures and bureaucracies/agencies at the national level. The more independent the executive agency, the more unfeasible the possibility for political control or ‘responsiveness’ to an accountability forum. By contrast, the emphasis of such a relationship would be on account-giving, meaning that the best outcome for the oversight relationship between the EP and the ECB is also ‘Answerability’ (scenario 2).

Starting from these preliminary expectations, the other variables mentioned in Table 3.2 can shift accountability interactions closer or farther from the best-case scenario. First, high political pressure on an issue (such as financial assistance programmes or the health of banks in the Eurozone) is likely to increase the strength of parliamentary questions and the responsiveness of executive actors. In a similar vein, the ability to ask written questions or the format of committee meetings (e.g. the number of speakers permitted per session) will allow MEPs to ask stronger oversight questions and expand the time in which executive actors must respond. The structural opportunities for oversight might also limit the possibility to ask follow-up questions, which would normally indicate a strong performance by the accountability forum.

Conversely, the remaining variables in Table 3.2 are not favourable to facilitating oversight and hence move accountability interactions closer to the best-case scenario. On the one hand, the profile of the EP is not geared towards scrutiny of the executive and government–opposition dynamics. As described in Chapter 1.2, the EP is a parliament focused on law-making as opposed to control of the executive; in addition, political polarisation is diffused among 7–8 political groups per parliamentary term. Although a ‘governing coalition’ exists in support of the Commission and is typically composed of 2–3 political groups, the competition between groups is less clear. Moreover, in the relationship with the ECB and the Council, the absence of a ‘governing coalition’ is more pronounced because – unlike the Commission – these bodies are not in a principal–agent relationship with the EP (for a detailed discussion, see Chapters 4.2 and 6.2, respectively).