Part IV Bringing It Together

6 Institutional development in new democracies

Network structure and uncertainty shape the incentives of political and economic elites to act collectively in the process of creating new institutions. The two previous chapters each explored the impact of uncertainty. Chapter 4 showed how political uncertainty structures ties between parties and firms. Chapter 5 demonstrated how political uncertainty interacts with network breadth to structure human ties, in the form of career networks, between the state and the economy.

In order to understand the link between networked societies and institutional development, this chapter identifies different forms of state–society relations that have emerged among eleven countries in post-socialist Europe through data that capture the two features identified as critical variables in this study: the breadth of social networks and the level of uncertainty in the political and economic field.

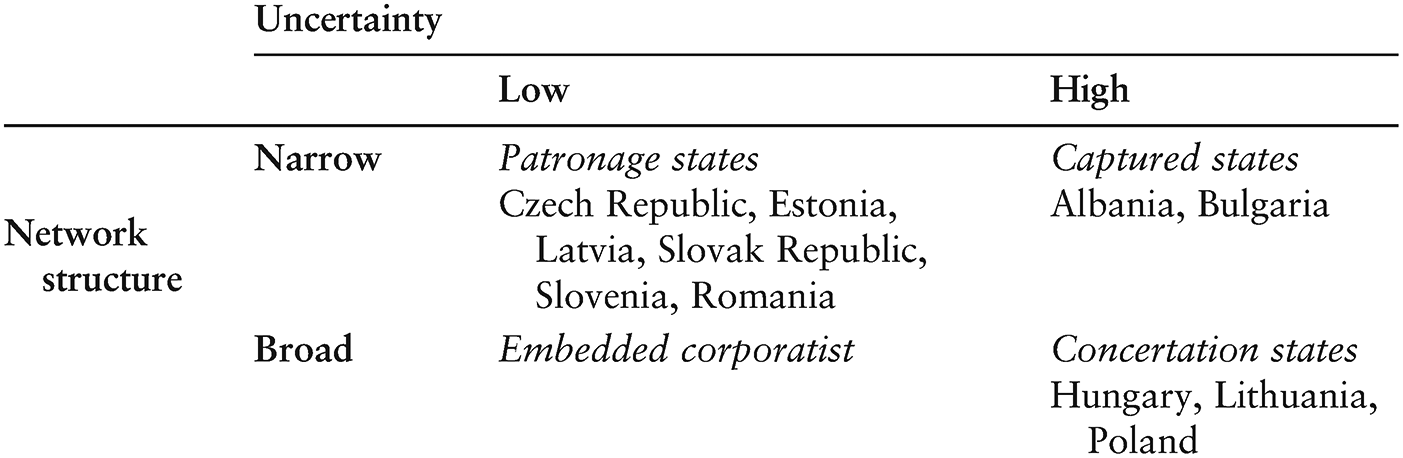

In describing the trajectories toward institutional development taken by the countries in question, I identify the following four types. First, there are the post-communist countries that have developed broad networks among firms and between the economic and political elite and have relatively high levels of uncertainty. These concertation states have made the most progress in the development of broadly distributive institutions. Second, countries with narrow networks and low levels of uncertainty have developed patronage states. These states have made moderate progress on the development of broad institutions. Third, countries with narrow networks and high levels of uncertainty have developed captured states. These countries have made the least progress in the development of broadly distributive institutions. Finally, the fourth category consists of embedded corporatist states, which comprise broad networks and low uncertainty. I do not expect to find countries with competitive elections that fit in this category. Rather, the combination of low uncertainty and broad networks describes Asian developmental states (for example, South Korea, as described by Evans Reference Evans1995).

This chapter confirms the finding that in countries in which dramatic reform and institutional development are taking place simultaneously – as in many emerging market countries and all the post-socialist nations – one tends to observe the emergence of broadly distributive institutions when uncertainty is higher and social networks are broader. This is counterintuitive, and in striking contrast to arguments in economics and political science that strong social networks hamper institutional autonomy, which is instead reinforced by predictable, fast, and early reform (Lipton and Sachs Reference Lipton and Sachs1990a; Lipton and Sachs Reference Lipton and Sachs1990b; Sachs Reference Sachs1994; Shleifer and Vishny Reference Shleifer and Vishny1998). Rather, the argument presented here draws on a long tradition in sociology focusing on the advantages of broad networks of weak ties for generating diverse resources (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973), as well as a literature in comparative politics that points to the role of historical struggles, social dislocations, relational ties, and negotiated institutions as the source of autonomous state power (Moore Reference Moore1967; Mann Reference Mann1984; Evans Reference Evans1995; Waldner Reference Waldner1999).

Markets and networks: empirical puzzles

This chapter is motivated by an empirical puzzle about networks and uncertainty that undermines traditional explanations and suggests that the alternative spelled out above might have more leverage in explaining the emergence of institutional development. Take the comparison of two countries – the Czech Republic and Albania – at opposite extremes of the European post-socialist experience. The former is one of the success stories of transition, ranked as a regional leader in terms of government effectiveness – defined by the World Bank’s “Worldwide governance indicators” as “the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies” (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2009). Albania, by contrast, has been the basket case of Europe. In both countries, however, firms express the same level of confidence (high) in their ability to find recourse without resorting to illegal payments in a case when an official acts against the rules (EBRD 2005b).

This surprising result raises more questions than it answers and suggests that there are two different dynamics generating the certainty of recourse, which likely does not have the same significance in both countries. As survey data show in the coming pages, two different orders frame and support market activity and the development of market institutions in these two countries, and we do not have a satisfying account of this process.

Albania and Poland provide another interesting contrast. Poland also ranked among the top regional countries for government effectivness in the late 1990s and 2000s.1 Yet, in Albania, firms find interpretations of the law more consistent and predictable. In fact, on average, they express the highest level of confidence in the sample. Most firms in Poland find them inconsistent and unpredictable (EBRD 2005b). This comparison suggests that the level of institutional performance varies significantly across the region and is not directly linked to the traditional indicators of quality of governance, such as levels of corruption.

In a further example, one of the basic components of a market economy – lending – shows an unexpected difference and dynamic in the last pair of countries. Albanian banks carry half as many non-performing loans on their balance sheets as (often partly party-owned) Polish banks, despite lending approximately the same percentage of GDP. This may be because Polish banks undertake more risky lending based on network ties. In fact, Polish firms use network sources of finance as a key source of investment capital, according to BEEPs (EBRD 2005b).

These cases could not be more different in most dimensions, and thus they make clear that there is good reason to revisit assumptions about the mechanisms that link networks and network-based practices, uncertainty, and institutional development in order to understand the divergence we now see across the region.

All the comparisons above highlight the different foundations on which interactions between firms and the state are structured. As discussed in the Introduction, the early literature on institutional reform in post-socialist states identified a core set of desirable features in this relationship. One key feature was an emphasis on the sociological dimensions of the Washington Consensus: disruption of network ties and state autonomy. These were critical components of the move toward privatization, liberalization, deregulation, fiscal discipline, and the withdrawal of subsidy spending associated with planned or coordinated market economies. Scholarship on corruption also broadly supported convergence on a set of institutions associated with market liberalism.2 Deviations from these goals, it was argued, generated pathologies of reform (Hellman Reference Hellman1998; Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2003). Arguments in these literatures became heavily politicized and came to reflect dominant positions in the debate on the Washington Consensus package of reforms.3 Along the way, much of the complexity of models of economic development emerging in the post-socialist region was lost.

This chapter shows that a variety of novel solutions to the fundamental problem of economic transition have emerged in each of the eleven countries surveyed. In some countries firms and politicians turned to networks, while in others they individually turned to the state. For example, medium and large firms use network ties to existing customers as the leading source of new business in Poland, while the government primarily performs this function in Hungary (EBRD 2005b). Although horizontal network ties support business in the former, vertical ties do so in the latter.

I have identified two key features in previous chapters that broadly distinguish countries: network breadth and uncertainty. I categorize state types by the combination of these two dimensions. Each possible pairing shapes the payoffs of making long-term investments in building institutions. As a result, each combination generates a different state type. The next section empirically explores this typology, and the final section shows that each state type has an impact on the institutional development that takes place.

Data and methods

The analysis of state types is based on two factors: (1) the extent to which networks that link the state and the market are narrow or broad; and (2) the extent to which the future is uncertain for economic and political actors. These are latent qualities, however, that can be accessed only by using data that function as manifestations of broader characteristics in each national system (Shawn and Simon Reference Shawn and Simon2008). To capture these latent qualities, one must construct country-level measures based on more concrete manifestations. Two key methods, factor analysis and cluster analysis, are available to build measures that capture the latent qualities of countries on the basis of sets of more directly measureable variables. Factor analysis is useful in generating latent measures out of similar variables, assembling them into a single new variable. Cluster analysis is deployed here because it captures latent similarity among cases. In other words, it accomplishes exactly what is called for by assembling similar groups of cases based on a set of variables that describe them. These cases share a latent characteristic that emerges from the mosaic of values on the underlying variables (Aldenderfer and Blashfield Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984; Kaufman and Rousseeuw Reference Kaufman and Rousseeuw1990). Cluster analysis thus permits the identification of groups of cases based on the values that together express the level of uncertainty and the breadth of social networks in each case.

The breadth of networks and uncertainty are explored in this chapter by the use of data from the survey conducted by the EBRD in 2005 (EBRD 2005b). Numerous data sources provide insight into the nature of state–business interaction and reflect the level of cooperation, accountability, stability, and predictability of this relationship. Such indicators are not without flaws, however. For example, surveys whose purpose is to study state capture more easily detect administrative corruption, because respondents have much more contact with low-level corruption than high-level capture and tend to infer the presence of the latter from the former (Knack Reference Knack2006). Despite such drawbacks, firms are a leading source of information on government political and bureaucratic conduct, and the survey responses they provide offer hard evidence about the nature of interaction with the state. The indicators used also report on the ability of firms to resist and cooperate with both low-level decision makers and high-level political actors on an everyday basis.

Using cluster analysis on social linkage indicators and on levels of uncertainty, state types can be created to group countries that are most similar. There are many variants of clustering methods, which use different procedures to join cases into groups. The two most commonly applied methods, hierarchical and k-means cluster analysis, generate similar results for the data used here. Three robust groups of countries emerge. One of the countries, Albania, is an outlier on many measures. The analysis was conducted both with and without Albania to confirm that the pull of its extreme values did not affecting the clustering solutions.

Cluster analysis requires the scholar to make a decision about the clustering method and the distance measurement used to assess similarity between cases. The scaling of variables has been thought to influence clustering outcomes by giving more weight to variables with larger scales, while some have found that standardization does not affect results in most cases (Aldenderfer and Blashfield Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984). All analyses were performed with variables standardized to z-scores to neutralize any effect that different scales may have and compared to results on unstandardized variables. Cluster assignments remained robust.

Variables

In the pages that follow, results are reported from clustering cases using questions that measure network breadth and uncertainty. The analysis was conducted with questions from the 2005 BEEPS data (EBRD 2005b) that reveal the importance of networks to firm interactions with political actors. Although the questions ask about individual firm perceptions and behavior, aggregated they reveal the role that networks play in firm interactions in a given country. The following variables were created.

SUPP, a variable that captures the stability of firm–firm networks. The question asks if firms would continue to use a supplier despite a significant price rise. I interpret persistent customer–supplier ties despite a price increase to mean that economic relationships between firms exist in the context of other types of ties that bind firms to each other. The extent to which firms choose not to switch suppliers in spite of economic motivations (rising cost) reveals the degree to which firm–firm networks underpin economic activity. Higher values indicate that firm–firm networks are broader.

NETFIN, a variable that expresses the extent to which firms obtain working capital from network sources (informal sources, friends, state-owned banks, credit from customers, and credit from suppliers) as opposed to market sources (foreign banks, private banks, and equity markets). Higher values indicate broader networks.

BUSORG, a variable that captures the extent to which business organizations are valuable in lobbying business. High values indicate that more firms use collective bodies for interest expression. In other words, networks between firms are broader.

A second set of indicators was developed to assess the uncertainty that firms and parties face. For this analysis, the following variables were used.

COMPET, a variable that expresses the number of competitors firms face in the national market. Higher values indicate high levels of competition, and thus uncertainty in the market.

TAXINS, a variable that captures the frequency of annual inspections by the tax authority and thus another element of uncertainty that firms face. Higher levels indicate frequent inspections.

IDTURN, a variable that captures the extent to which ideological turnovers, as opposed to simply leadership turnover, of the party in power are a source of institutional uncertainty for firms (Horowitz, Hoff, and Milanovic Reference Horowitz, Hoff and Milanovic2009). Ideological turnovers are turnovers across the ideological divide. Higher values indicate more frequent turnover. The choice of ideological turnover is discussed in Chapter 1. Briefly, ideological turnover captures the number of political events that disrupt the networks linking firms to power holders.

Three groupings of countries emerge when these variables are clustered together.4 Cluster centers are reported in Table 6.1. These are interpreted as the mean score of a value for a cluster on a given variable. Traditional significance tests are not available or appropriate for cluster analysis, as the analysis itself is designed to find the most significant cluster possible (Aldenderfer and Blashfield Reference Aldenderfer and Blashfield1984; Everitt, Landau, and Leese Reference Everitt, Landau and Leese2011).

Table 6.1 Networks and uncertainty in the Baltics, east central Europe, and the Balkans

Note: Final cluster center scores.

Cluster analysis differentiates the way that networks and uncertainty are present to create three groupings. Cluster 1, the grouping of concertation states, is marked by broad networks and high levels of uncertainty. In these countries, firm–firm networks are very stable. This is shown by the above-average use of business organizations and the persistence of customer–supplier networks independent of price levels. On both these variables, cluster 1 has the highest relative values. Firms also make frequent use of network sources of finance. When disaggregated, the data show that firms in cluster 1 make frequent use of informal sources of finance, supplier credit, and state-owned banks. While networks between firms as well as ties to the state typify these economies, business exists in an environment of uncertainty, with high competition between firms and frequent political alternation.

In cluster 2, patronage states, firms have narrow networks and face low levels of uncertainty. They do not use collective organizations, and horizontal ties between them are unstable. Customer–supplier relations are sensitive to price. Network sources of finance are still used by firms, but not as frequently as in cluster 1. Political alternation is also relatively low, and the level of competition between firms is the lowest of the three clusters.

Firms in cluster 3, captured states, have narrow networks and face high levels of uncertainty. The use of collective organizations by firms is low relative to the other clusters, and customer–supplier ties are more sensitive to price than in cluster 1. The exception to this is that network sources of finance are quite commonly used. Disaggregating reveals that firms, particularly in Bulgaria, rely on “family and friends” as sources of capital. Since I consider only medium- and large-sized firms, I interpret this as meaning allied firms and their executives. Supplier credit is also common. These narrow networks coincide with high levels of uncertainty. High political turnover and frequent tax inspections suggest a state that is weak, chaotic, and predatory. In contrast to cluster 1, this uncertainty does not extend to inter-firm competition, which is significantly lower.

The two dimensions in the cluster analysis can be reformatted into the typology proposed in Table 1.1. The resulting classification is shown in Table 6.2.

The analysis groups cases together on political uncertainty that are not normally considered similar, but this follows from the data used here. Uncertainty is composed of three individual components: the level of competition from other firms, the level of intrusion from the state, and the unpredictability of politics. The latter was captured using data on ideological turnovers for each country. Lithuania is thus classified as a case with high uncertainty because it had four ideological turnovers between 1990 and 2005, according to Horowitz, Hoff, and Milanovic (Reference Horowitz, Hoff and Milanovic2009). This is the highest number for the region, achieved only by two other countries: Bulgaria and Hungary. Poland trailed slightly, with three ideological turnovers. By contrast, Latvia had only one ideological turnover, although it had three government turnovers (recompositions of the governing coalition). These were episodes when the majority coalition changed but did not shift across the ideological divide. While Latvia is an example of a country known for government instability, these changes did not take place across the ideological divide. As regards ideological turnover, Latvia has instead been very stable despite frequent recompositions of government. The distinction is important, because we expect changes in government to have a different and arguably less disruptive effect than ideological shifts of power (Horowitz, Hoff, and Milanovic Reference Horowitz, Hoff and Milanovic2009: 121).

Impacts on governance

This section shows how different combinations of network breadth and uncertainty pair with patterns of institution building. Thus, it becomes possible to determine whether, for example, societies in which firms are linked by broad networks but also face higher levels of uncertainty tend to progress to broader institutional development than those in which networks are narrow and uncertainty is high.

External factors have driven some countries in the post-communist region to move ahead on institutional reform in specific areas. Given the external pressure for reform and liberalization related to European Union accession, according to the EBRD, trade and foreign exchange liberalization are at high levels across the region. Nevertheless, there are significant differences between the clusters. Averages across six policy areas – enterprise restructuring, price liberalization, trade and foreign exchange policy, competition policy, banking reform and interest rate liberalization, and securities market and non-bank financial institution reform – show that the three clusters have performed as expected.

The following graphs of outcome variables show only small numerical differences between clusters. The differences between whole numbers in the EBRD scoring scheme represent big outcome differences, however. The EBRD’s scoring system rates countries on different policy areas on a scale ranging from 1 to 4+. With minor differences between the policy areas, a 1 indicates little progress from a planned economy or an absence of policy in a given area. A 2 indicates the existence of some institutions, while a 3 indicates “some progress” in the development of a regulatory framework. A 4 means that the policy framework approaches Western standards, while a 4+ indicates a framework on the level of advanced industrial countries. The difference between a 2 and a 4 is therefore enormous. Figure 6.1 shows that captured states have made the least progress. Patron states are also in the same general category of reform, although they have made slightly more progress. Concertation states are in the highest category. The large difference between the concertation and captured cluster, for example, indicates a sizeable gap between the quality and implementation of policy frameworks in countries belonging to the two clusters.

Figure 6.1 Progress on six major policy areas, 1990–2005

The clusters vary especially when compared on areas of policy that are largely determined by factions. For example, institutional reforms that regulate the internal market framework and are more easily subject to pressure from interest groups display more variance, and countries from the same wave of EU integration, such as Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, or Romania and Bulgaria, score differently from each other. This is consistent with the literature on the impact of EU expansion discussed in Chapter 1.

Competition policy

One major indicator that can be used to judge the impact of firms on the state is the progress that a country has made on competition policy. Competition policy and the structures that enforce it by definition harm the interests of insiders, so the development of a competent body that monitors and enforces such policies requires the support of a broad coalition of firms. The EBRD “Transition indicators” provide a comparative measure of progress on competition policy. There is a range of outcomes across the typology presented in Figure 6.2. As predicted above, where networks are strong and uncertainty is highest – the concertation states – progress on competition policy is greatest. Differences across full integers represent large differences in outcome.5

Figure 6.2 Competition policy, 2000–2005

Recapitulating the mechanisms at work here, the enforcement of competition policy is taken as a result of the struggles of diverse groups to create an institution that “levels the playing field.” Thus, competition policy is also a good indicator of the distribution of the power of groups. Where progress is made, competing factions have brokered a structure to make sure that all parties stick to the rules of the market and abide by whatever joint conception of fair competitive practices obtain in a given context. Where such structures are lacking, one group of insiders is likely to dominate and block the development of competition enforcement. These results are in line with the argument that concertation states, with broad networks and high levels of uncertainty stemming from a rapid development of institutions and frequent political turnovers, have competing factions of business elites who gradually recognize the benefits of an enforcement authority that reduces selective benefits. By contrast, in patronage states, there are much weaker incentives to build such leveling institutions. Captured states have the weakest incentives for collective action. In Bulgaria, when the business community attempted to coordinate and create an institutional infrastructure that would provide stability for repeated interactions, the attempts repeatedly broke down as calculations about future political counterparts became difficult to make and dominant firms were unable to look beyond their very short time horizons.

Financial institutions and secured transactions policy

As seen in Figure 6.3, securities market and non-bank financial institution reform shows similar divergence in the amount of reform undertaken.6 The ability to regulate securities transactions and safeguard the rights of minority shareholders is a critical component of sophisticated markets, giving firms the ability to raise capital and reassuring shareholders that their interests will be protected. Thus, this is another variable that measures the extent to which the framework benefits the interests of broad versus narrow coalitions. Although standards in the region fall below the level of advanced industrialized countries, in the case of concertation states we see a development of institutions that protect minority shareholder rights, settlement procedures, and a regulatory framework.

Figure 6.3 Securities market and non-bank financial institution reform, 2000–2005

Banking

Differences are also to be found in banking law, although they are narrower than in the two prior areas, as shown in Figure 6.4.7 Again, concertation states lead in the area of banking reform.

Figure 6.4 Banking regulation reform, 2000–2005

Rule of law

A final broad measure that sustains the findings of this chapter is drawn from the World Bank “Worldwide governance indicators” of the rule of law, as shown in Figure 6.5. This indicator expresses the extent to which the rule of law is applied equally to all affected parties, ranging from –2.5 to 2.5. It captures the extent to which “agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence” (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2009). This is a composite measure that also includes factors such as trust in the police that are not relevant here. Nevertheless, quite a few of the components of the rule of law indicator give a sense of the selective or broad nature of institutions emerging in each cluster.

Figure 6.5 Rule of law by cluster

Concertation states were significantly more advanced on this measure after a decade of reform but had lost ground by 2005. Poland and Hungary both received weaker scores in the latter year, driving down the result for the whole cluster. As a result, the difference between the concertation states cluster and the patronage states cluster is not likely to be significant by the end of the period. This raises an interesting question about why patronage states have done surprisingly well on the development of the rule of law. One possible explanation is that patronage states may have reasons to develop the rule of law despite the disproportionate power of political actors because the political elite still depend on firms to generate revenue and thus have some incentives to provide an institutional framework that can support market activity. I discuss this further in the conclusion. Captured states trail dramatically on this indicator.

Conclusion

This chapter grouped together post-communist countries on the basis of two characteristics: (1) the extent to which networks are narrow insider networks or broad heterogeneous networks; and (2) the predictability of the environment in which firms operate. Four groups were posited and countries then placed into a typology that expressed variation along these dimensions. Once clusters were identified, it was demonstrated that membership in a cluster has significant and, in the case of several clusters, unexpected impacts.

Three principal findings emerge from the large-n analysis. First, unsurprisingly, captured states have performed poorly in the development of institutions that serve the broad interest. Narrow societal networks and high levels of uncertainty have given narrow groupings the ability to influence the course of institutional development.

With regard to patronage states, one might expect them to perform as poorly as captured states. The second finding of the large-n analysis is that patronage states fall between captured and concertation states on measures of institutional development. On some dimensions, such as the development of the rule of law, they perform as well as concertation states by the end of the period under observation. They also fall between captured and concertation states in the development of competition policy and securities market regulation, however. How can we interpret this result? In patronage states, political elites are able to dominate economic elites because of narrow networks and low levels of uncertainty. Nevertheless, political elites in patronage states have an interest in institutional development because they rely on funds extracted from business. Patrons are both grantors of benefits and extractors of resources. To this end, institutional development is useful for promoting business performance. As outlined by Greif, Milgrom, and Weingast (Reference Greif, Milgrom and Weingast1994), rulers must tie their own hands with institutionalized procedures to be able to extract resources effectively. Patronage states have undertaken some institutional development in order to facilitate economic development because they rely on business for resources. This impetus for institutional performance is not as great as in the concertation states, however, because of the lower level of party competition and the narrowness of business networks. The third finding, which supports the argument made in earlier chapters, is that the combination of high uncertainty and broad networks correlates strongly with countries that have the highest levels of institutional development of the three clusters identified in the analysis.

1 Poland’s ranking for governance effectiveness declined somewhat with the entrance of a new set of political parties that governed in a chaotic fashion.

2 The literature here is vast. Some prominent exponents of this view are Rose-Ackerman (Reference Rose-Ackerman1999), Shleifer and Vishny (2002), and Holmes (Reference Holmes2006).

3 Authors have noted this in other regions of the world as well. See, for example, Serra and Stiglitz (Reference Serra and Stiglitz2008).

4 Multiple cluster solutions were explored. The explanatory power of a three-cluster solution was confirmed by referring to pseudo-F values, which capture the increase or decrease in fit of 1 to n-cluster solutions.

5 Competition policy reform is scored by the EBRD as follows.

6 Securities market and non-bank financial institution reform is scored by the EBRD as follows.

7 Banking regulation reform is scored by the EBRD as follows.

7 Conclusion: political varieties of capitalism in emerging markets

What was hailed as a transition to democracy and markets over twenty years ago has turned out to be a long and arduous struggle on the path to develop effective institutions that can support economic development. This book began by observing that, after two decades of reform and two waves of European integration, a surprising diversity of relationships between economic and political actors is still evident in the post-communist world. Notably, countries such as Poland, which have been among the leaders of institutional development and economic growth, also display dense ties between the economy and the polity, while countries such as Romania and Bulgaria do not. The early literature on post-socialist reform viewed such ties between the polity and the economy as the source of poor progress on institutional development because powerful insiders hijacked reform agendas. I have observed a number of cases, however, in which the opposite seemed to be true. Armed with this puzzle, I set out to understand the conditions under which networks could support institutional development. At the core of this analysis is a desire to understand the conditions under which political and economic elites are able to use networks to act collectively.

A literature on the economic growth miracle that took place in east Asia in the 1990s offered tools to explore the role that networks play in structuring the choices that elites make. Scholarship on the developmental state in east Asia focused precisely on the powerful role that embeddedness played in helping political elites cooperate with business leaders, resulting in rapid growth. The case studies were mostly non-democratic countries, however, and the outcomes seemed heavily dependent on a special set of cultural circumstances and international political economy pressures. With few exceptions (Kang Reference Kang2002), the east Asian “tigers” were seen as having internal cultural characteristics and external security pressures that made embedded elites work together and limited the abuse of embedded ties. These limiting factors were not present in post-socialism.

In contrast, one powerful limiting factor present in the transition countries was the extent of political uncertainty related to democratic elections. All the cases investigated here had regular electoral contests but different levels of competition. As culture and the international pressures of the post-war international system were the exogenous factor that limited pernicious collaboration in east Asia, so political uncertainty served as the factor that conditioned how networks were used in post-socialism.

I thus explored how the structure of network ties between the polity and the economy, together with the level of uncertainty, affect the ability of elites to engage in collective action. Different combinations of these two variables shape the incentives of political and economic elites to cooperate, resulting in different and specific patterns of institutional development. The pages that follow review the findings and discuss the implications of this argument for countries undergoing large-scale economic transformations.

The impact of networks and uncertainty

I argue that the different combinations of the structure of networks and the level of uncertainty determine the path of collective action that political and economic elites take. This shapes the trajectory of institutional development. Where narrow networks are combined with high levels of uncertainty, economic actors have the upper hand against political elites. Because economic elites have few incentives to forge long-term bargains with political elites, these countries have made very poor progress on institutional development. I label these captured states.

In patronage states, narrow networks and low levels of uncertainty allow political elites to dominate atomized economic actors. Similarly, few incentives exist for institutional development, as economic actors are poorly coordinated, and political actors do not need to be responsive to their demands.

Finally, in concertation states, broad networks link economic and political actors and lead them to take a long view in economic exchange. As a result, they create rules of the game that are broadly distributive.

Findings

Key finding I: different network structures emerged across post-socialism

Through a survey of firm network structure and a comparison of firm networks in Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland, I have shown that different network structures emerged across the post-socialist world. Taking just the comparison of Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria, different owner types emerged as the organizing poles in each economy, as a result of the varying approaches to transformation outlined in Chapter 3. The Polish network of firms was structured by the key role of banks, which came to own large numbers of firms through debt-to-equity swaps that were common during the early phase of transition. This resulted in a broad network with many ties between firms. The largest firms in both Romania and Bulgaria were, instead, organized around industrial firms and individual investors, creating much narrower networks.

Elite networks also took on different structures. In Poland, individuals shifted jobs often and between more sectors than did individuals in Romania. Although Bulgarians also shifted jobs often, they tended to have less diverse careers. As a result, the latter two cases had much narrower career networks.

Key finding II: broad networks raise the likelihood of collective action

Broader networks that include more heterogeneous agents also raise the incidence of collective action among firms. Instead of lobbying for themselves using insider channels, firms in countries in which networks broadly linked them were more likely to use business associations for political ends. In turn, in most cases they were also less likely to use private channels to parties or bureaucrats.

Key finding III: broad networks combined with high uncertainty improve institutional development

Where networks were broad and uncertainty was high, greater progress was made in institutional development. More progress was made in the reform of banking law. The development of competition policy and an authority that could monitor it also progressed much further. Finally, measures of the rule of law showed higher levels of performance. The development of institutions for the oversight of party finance – another particularly sensitive area of regulatory development – also developed further. On this last measure, none of the three, Poland, Romania, or Bulgaria, approaches an ideal level of oversight that would render it free of illicit activity. Poland made greater advances than the other two countries, however. Institutions of oversight were created when all three faced tremendous external pressure from the European Union to reduce levels of corruption. Yet Poland developed the most functional system. The empirical findings are summarized in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Summary of findings

The differing role of institutions of collective action described in Chapter 2, the varying role of inter-firm ties discussed in Chapter 3, the different combinations of uncertainty and network structure discussed in Chapter 4, and the stark differences in career patterns across countries described in Chapter 5 are all features of three distinct trajectories of institutional development that have emerged out of the rapidly developing market economies of post-socialist Europe. These three forms are the captured, patronage, and concertation states. Each of these orders is supported by a series of complementary institutions that emerged as solutions to the problem of uncertainty that business elites and politicians faced over the period of the transformation.

Broader implications

What insights and broader conclusions can be derived from the findings of this book? One goal of the book has been to shed light on the process of post-communist development and the critical role of both networks and democratic competition in it. One of the key lessons of the post-communist transformation is that networks provide a vital resource to economic and political actors during periods of rapid change. These networks can be utilized in a variety of ways depending on their structure and the constraints placed on them, however. As scholars such as Kang (Reference Kang2002) have pointed out in the context of non-democratic east Asian states, how ties between political and economic elites are put to use depends on the limitations facing these elites. If the arguments made in the preceding pages are convincing, then the central policy implications are to promote orderly political competition and support the development of networks both within the economy and between the state and business actors. The cases examined here illustrate the consequences of weak competition and sparse networks that took hold in some countries. Consequently, one wonders about the future for both the desirable and less desirable paths. Of particular concern is the question of the stability of the three paths – concertation, patronage, and captured states – identified here after the period 1990–2005 that is covered in this book. For the paths that generate poor outcomes of institutional development – captured and patronage – it is particularly important to ascertain if states eventually emerge from them, even if they do so slowly. It would also be useful, however, to ascertain if the networks that link parties and business in concertation states eventually give way to stable and “hardened” institutions. Is it the case that this arrangement, while important during the early phase of development and high levels of uncertainty, is displaced by more formal structures? Or do networks continue to play a role even when functioning institutions have emerged?

These questions can be considered in two different ways. First, we can examine changes that have taken place in the case studies after 2005, the end point of both the data and the case study research conducted for this book. Second, we can examine cases in other regions that might shed light on possible future developments.

Regional changes

Changes in the party system are one way that shifts out of a particular party–business alignment might come about. It is also possible that party system development will bring about a breakdown altogether of the network-based dynamic. Of particular concern are the concertation states, in which, I have argued, stable party–economy ties have supported post-communist development. It is worth considering how Poland has been affected by changes in the party system that began in 2005. At that time the dominant social division in post-socialist Poland began to shift from an anti-communist/post-communist cleavage to a new division between those who have benefited from reform and those left behind. This shift brought the end of the left SLD and post-Solidarity coalition AWS and their seeming replacement with two new main center-right parties and a host of smaller partners.

It would be reasonable to expect that such a shift in the party system would have unsettled the dynamic that existed until 2005. This unsettling could result from the scrambling of existing networks linking politicians to business leaders, or from the nature of political competition having shifted. Both seemed likely with the emergence of the Law and Justice party (PiS), which formed a minority coalition government that lasted until 2007, and vocally attacked the business elite, called for an end to the Polish oligarchy’s influence, and pledged to move the country into a “Fourth Republic” free of the corruption and cronyism of the post-communist period (Markowski Reference Mares2008: 1056). Early elections in 2007 brought yet another new party, Civic Action (PO), to power. PO instead presented itself as an economically liberal party with conservative positions on social issues, and governed in coalition with the Polish Peasant Party. At the time of this writing, the PO–PSL coalition is still in power, having been returned to power in 2011.

Based on the election of 2007, Gwiazda (Reference Gwiazda2009) argues that we may finally be seeing the settling of the party system. This remains a minority view, however, and others continue to view the system as unsettled. Szczerbiak (Reference Szczerbiak2012), for example, sees the first re-election of an incumbent government, in 2011, as a potential sign of stabilization, but points to the strong performance of a new anti-clerical liberal party, Palikot’s Movement, as a sign of continued instability. Most scholars continue to classify Poland as a weakly institutionalized party system with high levels of volatility, poor party discipline, and high fractionalization (Lewis Reference Lewis2006; Markowski Reference Markowski2008). There is, consequently, no reason to believe that the level of political uncertainty has declined. On the other hand, Shabad and Slomczynski (Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2002) argue that Poland is in the process of developing career politicians, which would reinforce networks despite the emergence of new political parties.

There is little recent research on the connection of Polish political parties with the economy in the period after 2005. Despite the changes in the party system, available sources suggest that the ties between the state and the economy continue. Gwiazda (Reference Gwiazda2008) finds that, following the emergence of new party organizations, party patronage is as extensive after the shift as it was before 2005. Specifically, she finds that PiS, elected on a strong anti-corruption platform, “was relentlessly involved in the central government and economy, [and,] in addition, it extracted resources from quangos. Moreover, the new Civil Service Law increased state politicization” (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2008: 821).

The dynamic underpinning the concertation state is also reinforced by the attitudes of business leaders. In a survey conducted in 2009 and 2010 in Poland, Hungary, and Germany, Bluhm, Martens, and Trappmann (Reference Bluhm, Martens and Trappmann2011: 1024–5) find that Polish managers in top firms have a preference for an “active role of state” and “alienation towards capitalistic principles of competition” combined with a disposition toward “collective regulation of social partners.” Poland is exceptional in that feelings of alienation from capitalist principles of competition are particularly strong among business leaders in large firms. These attitudes suggest that managers view the benefits of collectively binding rules as outweighing their costs and risks while also being skeptical of market rules. This is particularly striking because business leaders in Poland are mostly drawn from a new, young managerial elite that has replaced the older generation of managers. It is also worth noting that all the large entrepreneurs of the pre-2005 period survived the party system change unscathed. Together, these findings suggest that the Polish economy will continue to develop toward some hybrid form of market. This will likely be based on networks and collective organization continuing to play an important role despite the emergence of functioning institutions. And, given the generational replacement of managers that has already taken place, it will likely develop with support from managers who are skeptical of liberal capitalism and welcome the active intervention of the state and political parties. The adoption of earlier practices of patronage by PiS, a party that came to power with a pledge to wipe away the pathologies of post-communism, indicates that even a disruption as large as a party system shift has not moved Poland toward a less network-dependent and more institutionalized arrangement.

Bulgaria, a captured state, has similarly not shifted path radically. New political parties have continued to emerge as Bulgarians shift their votes from one party to the next. In particular, dissatisfaction with the government of Simeon II gave rise to the Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria party (GERB) led by a former chief secretary in the Interior Ministry and mayor of Sofia, Boyko Borisov. GERB won the election in 2009 and Borisov formed a “no coalition” minority government, which nevertheless often relied on the support of potential coalition partners. Borisov enjoyed broad support because of a shift toward programmatic politics and, in particular, a hardline approach to corruption, spearheaded by Borisov’s interior minister, Tsvetan Tsvetanov (Kolev Reference Kolev, Kitschelt and Wang2012: 41). To some, this signaled a potential shift in Bulgarian politics (Kolev Reference Kolev, Kitschelt and Wang2012). GERB governed only until Borisov’s resignation in February 2013, however, over popular opposition to rising energy prices (Ehl Reference Ehl2013). Subsequent elections in March 2013 gave the most votes to GERB but failed to generate a clear outcome. The election also had the lowest turnout since 1989 – widely taken as an indication of voter resignation and disillusion even with GERB. A government formed out of this election is likely to be unstable.

It thus seems reasonable that Bulgaria will continue to operate in an environment of high uncertainty. In the economy, many of the leaders of the business community who emerged in the first wave of private property creation have been displaced by new figures. Nevertheless, Bulgaria is widely seen as a mafia state in which policy is determined by organized crime and the shadow economy. Unfortunately for Bulgaria, large legitimate business is also controlled by these actors. Further, Bulgaria continues to be plagued by a weak institutional environment and corrupt management practices in firms (Center for the Study of Democracy 2013). In fact, it seems likely that captured states have a very hard time emerging from the circumstances that have placed them there in the first place. The state capacity to make such a shift is simply lacking in the long run. As a government official in Bulgaria argued, “There is not a vicious circle of corruption. The real problem is administrative capacity.” Without the development of state capacity, it is difficult to emerge from the cycle imposed by narrow networks and high uncertainty. Bulgaria, therefore, has been unable to move from being a captured state to some other form despite even GERB’s quite aggressive attempt to tackle corruption head-on.

Romania is perhaps the case that experienced the most change from the period before 2005. Between 2004 and 2008 Romania was governed by a coalition that emerged in opposition to the Social Democratic Party, which had through various mutations dominated Romanian politics for much of the last two decades. An electoral alliance called the Justice and Truth Alliance (DA), composed of the Democratic Party and the National Liberal Party, emerged in 2003. The priorities of this alliance were in line with the center-right ideology of its members and focused on attracting investment to Romania and empowering private initiatives, fighting corruption, creating a more fiscally responsible social policy, and depoliticizing the judiciary. In 2004 Traian Basescu was elected president and appointed Calin Popescu-Tariceanu, head of the PNL, to form a government, which resulted in a weak coalition of the PNL, the PD, the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) and the Conservative Party (PC). The DA split in 2007 when Tariceanu excluded the PD from the governing coalition. As a result, the 2008 legislative election gave birth to a new coalition government composed of the PSD and Democratic Liberal Party, the latter a union of the PD and the Liberal Democratic Party. The first designated prime minister of this coalition government, Theodor Stolojan, resigned after four days, and President Basescu then appointed Emil Boc, who would govern Romania during the economic crisis. Boc’s government collapsed in December 2009 when the PSD left the coalition. Romania’s government collapsed for a second time in February 2012, after protests that had erupted in January in opposition to austerity measures. This brought down Boc’s second government. The collapse took place against the background of heightened political struggle between Boc’s PD-L and the opposition PNL and PSD. A no-confidence vote sponsored by the opposition Social-Liberal Union (USL), seizing upon popular opposition to austerity cuts, caused the most recent governmental collapse: that of Mihai Razvan Ungureanu, in April 2012. The USL, a coalition formed by the PSD, the PNL, and the PC, won the general election in December 2012.

Although new alliances have emerged, the Romanian political leadership remains remarkably closed. Chiru and Gherghina (Reference Chiru and Gherghina2012: 511) show that for more than two decades major Romanian parties (they examine the PSD, the PD-L, the PNL, the UDMR, and the Greater Romania Party – PRM) have displayed an “uninterrupted oligarchic inertia” in which parties have highly centralized leadership selection and removal procedures with low party membership and little member involvement. Coman (Reference Coman2012) also argues that a reform that introduced single-member districts in 2008 had minimal impact on the power of party leaders. Moreover, despite the reformist and anti-corruption campaign that brought Basescu to power in 2004, much of the political elite colluded to reverse the reforms (Spendzharova and Vachudova Reference Spendzharova and Vachudova2012: 41). All three observations suggest that the political elite is insulated from societal actors and in a position to use patronage-based exchanges with business. This reinforces the view that Romania is still set in a form of patronage state, although this order may be more fragile than it was before 2004.

Lessons beyond the region

The western European experience also sheds light on the future development of at least two of the state types: concertation and patronage. There are no readily available examples of a captured state in the region.

Italy offers a western European case of patronage state. Governed by a dominant Christian Democratic (DC) party from the formation of the republic in 1948 until the Tangentopoli scandal in the early 1990s, it fits the definition of a low-uncertainty environment. Firms were also organized hierarchically through the Confindustria, which managed and structured relationships between different factions. The Confindustria served as the representative of the business community to the dominant DC (Martinelli Reference Martinelli1979). This resembled closely the patronage state type identified in this book, with high ownership concentration in pyramidal groups (Barca and Trento Reference Barca and Trento1997; Aganin and Volpin Reference Aganin, Volpin and Morck2005). The Tangentopoli scandal that swept away the Christian Democrats reshaped the party system, however, and brought this order to an end. Certainly, patronage states that depend on the dominance of a party or coalition are vulnerable to these types of shifts.

After Tangentopoli, it becomes more difficult to classify Italy. Firms are politicized. For example, Sapienza (Reference Sapienza2004) shows that Italian state-owned banks, key suppliers of finance to firms, charge lower interest rates than privately owned banks (by forty-four basis points on average). She also finds, however, that the political affiliation of the state-owned bank drives its lending behavior. The stronger the bank’s affiliated political party is in an area, the lower the interest rates that bank charges (Sapienza Reference Sapienza2004: 359).

Political competition is intense, however, between the disorganized and frequently reorganized leftist parties and a right dominated by Silvio Berlusconi since the early 1990s. The elite on the left is closed but internally deeply split between a center-left and parties further left of center. At the same time, reforms in the financial system since the 1990s should have brought significant changes to the Italian ownership structure. The evidence suggests that such a change has not taken place, however (Bianchi and Bianco Reference Bianchi and Bianco2006). Overall, it would seem that Italy has devolved from a patronage state but not yet moved to a new type.

More examples are available of countries resembling concertation states in western Europe. According to Hall and Soskice (Reference Hall and Soskice2001), firms in coordinated market economies (CMEs) in continental Europe coordinate economic activity using nonmarket methods. This is accomplished by relying on informal networks or corporatist arrangements between firms. Germany is the central example of a CME for Hall and Soskice, and a country in which networks serve the purpose of facilitating economic activity and have played a key role in the country’s post-war success. In addition to allowing firms to share information, engage in “network reputational monitoring,” set collective standards, develop collaborative systems of vocational training and engage in relational contracting, these networks have also helped German firms coordinate in response to the increasing competition associated with globalization (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001: 23; Kogut and Walker Reference Kogut and Walker2001). These networks persist and play a key role in supporting market activity despite the highly institutionalized environment in which German firms operate.

This is consistent with the broadly held view that markets rely on networks to function (White Reference White1981; Fligstein Reference Fligstein2001; White Reference White2004). We can conclude from this that the emergence of well-formed institutions does not necessarily mean that networks will be displaced, as they are an essential part of certain forms of capitalism, such as the CME. It is likely also the case that, as in the CMEs, institutionalization will transform the nature of networks so that they can be incorporated into more institutionalized but pluralistic processes of economic management. This is not yet the case in any of the post-communist countries. There is evidence, however, that similar processes have been under way as a result of democratic deepening in other regions where networks play a key role in the economy. East Asian states that were identified as developmental states have seen the evolution of networks and their incorporation into collaborative relationships with the state and political actors as a result of democratic deepening (Kim Reference Kim1999; Wong Reference Wong2004). As with the CMEs of western Europe, this suggests that networks persist even at the advanced stage of institutional development.

Networks and politics

Throughout this book, I have argued for the importance of social networks in political processes, and one key aim of this work has been to give them a central role in explanations of post-socialist development. North (Reference North2010) has argued that rationalist approaches to institutional change miss a key feature of institution building: historical forces and social structures that bind and limit the choices available to rational actors, as well as the inability of those actors to know ex ante which institutions will reduce transaction costs.

Social network analysis addresses these shortcomings, as has been shown by studies in economics and political science (Carpenter, Esterling, and Lazer Reference Carpenter, Esterling and Lazer1998; Lazer and Friedman Reference Lazer and Friedman2007). Often, however, in such work “networks” constitute a variable added to the analysis to capture the effect of social relations on outcomes (Putnam Reference Putnam1994), with little consideration of the impact that the structure of ties might have. As I can testify, data on networks are notoriously difficult to obtain, and even more so for multiple countries. Yet the benefits of such endeavors are significant, as they grant empirical foundation to the key notion of embeddedness, bringing testable hypotheses and theory building to a new level.

Multiple levels of analysis

The question of when elites cooperate to build institutions is a central question of development. The main lesson that I have drawn from this exploration is that broad networks under conditions of uncertainty create the conditions and incentives for elites to cooperate toward institution building. I have tried to address questions about the dynamics of institutional development in post-socialism by appealing to multiple levels of analysis. Behind this research design is a belief that generating insight into large-scale dynamics requires both the global view of quantitative social science and a thick understanding of dynamics on the ground. An exciting trend in recent political science is the tendency to conduct “mixed-methods” research (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005; Collier, Brady, and Seawright Reference Collier, Brady and Seawright2010), which most commonly combines quantitative analysis, allowing researchers to make sense of many cases, with deep analysis of a few cases, in order to understand the mechanisms that generate outcomes. I have followed in the footsteps of this scholarship. The ambition of this study has been to confirm the theory by utilizing data at three different levels: cross-national large-n data; within-country large-n data; and deep qualitative analysis. To this end, the study employed survey data that allow for cross-national comparisons, as well as two original data sets – of ownership and of careers – that allow for the quantitative exploration of within-country dynamics in three countries. Finally, extensive field research was conducted in each of these three countries to understand the forces driving what I observe in the data, and to supplement these understandings with the point of view of the individuals themselves through elite interviews.

At times, working at these three levels has seemed akin to the Sufi poet Rumi’s tale of “The elephant in the dark,” in which three men are led to feel an elephant in a dark room and come away with dramatically different impressions of its shape. The dynamic under study here is difficult to observe and understand. The preceding chapters represent a vigorous attempt to creatively investigate it. The challenge and the value of this study both lie in the fact that it seeks to identify the complex story of post-socialist development, told and cross-validated by what sometimes seemed like different glimpses of an elephant in the dark. Actors in this period of tumultuous change are agents within a social structure that they only partly perceive, yet they respond to it and also shape it. The dynamic is huge and its movements impressive, and yet it is hard to grasp its shape completely. The story of the elephant has endured because, while the men fight over who has correctly described it, we know that they each have a partial view. If only all three knew that each component is part of the larger whole. It is precisely this larger, cumulative impression of the beast that I have sought to deliver.