4 Access of Women to Justice and Legal Empowerment

The analysis of women’s access to justice, with particular reference to their legal empowerment in the setting of an Islamic state such as Iran, is not an easy task. However, I want to suggest that it is equally important to distinguish and highlight the impact of sociocultural dimensions of inaccessibility that women face on their path to justice. In light of the discussion in the previous chapter, which reviewed barriers to access to justice without any particular reference to women, the present chapter examines gender-specific barriers to access to justice. The chapter also provides a conceptual analysis of empowerment and specifically attempts to conceptualise the legal empowerment of women. The chapter first presents a detailed analysis of the key components that constitute Iranian women’s access to justice. Second, it analyses some of the key gender-specific barriers women might face in the quest to solve their problems and then explains how the concept can be reduced to measurable elements to maximise the access of Iranian women to justice.

Women, Justice, and Access

The discussion about access to justice becomes extremely complicated when it focuses on women in Iran. The analysis of “women’s access to justice” is most often merged with “women’s unequal status” in Iran as a Muslim country located in the Middle East. Controversial key words such as women, justice, Iran, Islam, and the Middle East can lead any potential discussion to a biased conclusion that there is no substantive justice under Islamic law for women. This impression, however, might appear unfair and incorrect to those academics who are familiar with the notion of access to justice, and yet it appears to be the fundamental understanding of many. Note, for example, a number of Iranian women activists (especially those in exile) believe that the lack of substantive justice is a result of legal and political Islam.1 Inside Iran also “secular women, who wielded no influence with the Islamic regime, launched their dialogues publicly through print publications (weeklies, monthlies), often arguing that Islam is unable to deliver justice to women” (Hoodfar and Sadr, Reference Hoodfar and Sadr2009: 892).

To understand how true these impressions and statements are, we need to examine what elements constitute the degree and quality of Iranian women’s access to justice. There are four main components to which I want to draw attention. The first part deals with the notion of justice and equality embodied in the law. It questions substantive justice and the existence of equal remedy for women in the law and other regulatory frameworks. The second component deals with institutions of justice, looking at procedural justice to examine whether or not the legal system is able to provide access to equal and effective remedies for women. The third element is about cultural norms and social context, which affect and determine the extent to which legal rights may be realised. Finally, the fourth component pertains to the human agency of access to justice, dealing with the issue of legal empowerment.

This book, however, does not claim to provide a complete analysis. The main objective here is to provide a contextualised understanding of the key elements associated with women’s access to justice in Iran. My second qualifying remark concerns information provided regarding discriminatory laws, which is reflected within the framework of substantive justice without attempting to develop a conceptual framework for women’s human rights in Islam, since most of the laws presented next are based on Islamic law. The reason for not including an analysis of women’s rights under Islamic law is because of the various interpretations of the Islamic sources and also the multifaceted sociolegal structures of Muslim societies. The complex nature of women’s rights in Islam thus requires a comprehensive study that is beyond the scope and rationale of this book.2 It is important also to note that the focus of this study is on the formal legal system, which is referred to as the “justice system.”

Women and Legal Justice

The discussion regarding Iranian women’s access to justice is most often faced with a substantive question: to what extent have the equal rights of women been protected by constitutional provision and domestic legislation? This section therefore looks at a list of discriminatory laws affecting equal access of women to justice. As noted elsewhere, a journey to justice for women is built upon the existence of equal remedy by international, constitutional law and by a legal and regulatory framework.3 With regard to international instruments, Iran has not ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).4 Under the previous president, Mohammad Khatami, the parliament passed a bill in favour of joining the convention, but the Guardian Council vetoed it on the grounds that the bill contradicted Islamic principles. This claim was made even though some Muslim-dominated countries such as Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, and Tajikistan have ratified CEDAW without any reservation. Also most of the Muslim states have joined the Convention, such as Bangladesh, Egypt, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, the Maldives, Morocco, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Pakistan, Tunisia, Turkey, and Indonesia, albeit some with substantial reservations. States that have used adherence to Islam as justification for including reservations in the Women’s Convention include Bangladesh, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, the Maldives, and Morocco. Tunisia and Pakistan have not expressly cited Islam as a reason for reserving their position, but the religious argument may well be inferred from the text of what appears to be a general reservation (Ali, Reference Ali2006: 86).

Countries that have ratified CEDAW are obliged to provide equal remedy for women in the case of discrimination. They also agree to eliminate discriminatory laws, in keeping with the principle of justice and equality within their legal systems. It seems that the Constitution of Iran has replicated the key provisions of CEDAW such as “equality before the law” even though it is not a state party to the convention. However, there are still several discriminatory laws against women that hinder their equal access to justice, as we shall discuss later.

The first promise of substantive justice is based on constitutional provisions. The constitution of Iran recognises equality among citizens in conformity with Islamic law. Article 20 of the constitution states: “All citizens of the country, both men and women, equally enjoy the protection of the law and enjoy all human, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, in conformity with Islamic criteria.” This general protection is narrowed down in Article 21, which places obligations on the state to ensure women’s equality. The state “must accomplish a prescribed list of social goals related to women’s role in society including, inter alia, the growth of women’s personality, the protection of mothers, and special insurance for women without support.”5 As stated earlier, the Iranian Constitution guarantees access to justice within fair trial provisions without any discrimination between women and men.6 Beyond the constitution, Iranian women’s legal status in the Penal Code and the Civil Code7 clearly appears unequal to that of men, as shown in the key examples of discriminatory laws listed below.

The Penal Code is marked with unequal treatment of the two genders based on the following key issues. First, criminal liability for girls commences six years prior to that of boys. Under the Penal Code, juveniles are immune from prosecution for committing a crime.8 The law does not determine the age for criminal responsibility; however, it defines a child as a person who has not yet reached the age of puberty. The age of puberty (known as boloogh) is set at age fifteen for boys and nine for girls in the Civil Code.9

A second issue relates to the unequal rights of women regarding testimony in criminal matters. The Penal Code has a long list of crimes in which women cannot testify, including drinking alcohol,10 sodomy, homosexuality,11 and organised prostitution.12 In other cases, the testimony of two women usually equals that of one man. For example, to prove adultery13 or unintentional murder,14 a man’s testimony is worth the testimony of two women. A third issue relates to unequal punishment. According to Article 209 of the Penal Code, “if Muslim man commits first-degree murder against a Muslim woman, the penalty of retribution shall apply. The victim’s next of kin, however, shall pay to the culprit half of his blood money before the act of retribution is carried out.” Therefore, the punishment (Qisas)15 is based on sex of the offender of the crime, which violates Article 14 of the Islamic Penal Code that reads: “a punishment that should be equal to the crime.” Another issue pertains to Diyat (blood money), which is a financial punishment pronounced by a judge.16 The law, however, considers a woman’s life to be worth half that of a man. “The blood money for the first- or second-degree murder of a Muslim woman is half of that of a murdered Muslim man.”17

In relation to family law, the Iranian Civil Code includes a discriminatory category of regulations where women and men appear unequal. Regarding marriage, for example, the law says that the marriage of a virgin girl [even after puberty] requires the permission of the father or paternal grandfather. If the guardian refuses to give permission without a valid reason, the court can grant permission.18 On the subject of divorce, “A man can divorce his wife whenever he wishes to do so” (Article 1133, Civil Code). Yet the wife is able to initiate a judicial divorce (referring to the court) in only a few cases. When it is proved to the Court that the continuation of the marriage is likely to cause difficulties, the judge can compel the husband to divorce his wife to avoid more harm and difficulty. If this cannot be done, then the divorce will be granted with the permission of the Islamic judge.19 Also, if the husband refuses to pay the cost of maintaining his wife, and if it is impossible to force him to make payments through the court, the wife can initiate divorce. The same stipulation exists in the case where a husband is unable to provide for the maintenance of his wife.20 The law also recognises khula and Mubarat.21 Another issue relates to the equal rights of women concerning inheritance. According to the law, women inherit half of what men would usually inherit in comparable situations.22

This list of laws, which are unequal in terms of their treatment of women is not exhaustive; nevertheless, the above-mentioned laws appear to be the most significant with reference to access to justice. These statutes clearly have an adverse impact on women’s equality and deny their equal access to justice. For example, imagine a path to justice for two women who are victims of organised prostitution. If they want to report the crime, their testimony will not be heard by the court. They also might be charged with adultery if they cannot prove that they have been forced into prostitution. Now imagine what would happen if the victims were men. Under the law, with the testimony of two men, the crime of pimping and organised prostitution can be proved.23

The discriminatory laws on divorce and custody of children cause a vast range of physical and emotional barriers for women in accessing justice. It is relatively clear that women find it difficult to deal with the fear of losing custody of their children if they initiate divorce. According to the law, “A mother has preference over others for two years from the birth of her child for the custody of the child and after the lapse of this period custody will devolve on the father except in the case of a daughter who will remain under the custody of the mother till 7 years.”24 And “If the mother marries another man during her period of custody, the custody will devolve on the father.”25 The unequal custody rights upon dissolution of the marriage are terrifying enough to discourage women from seeking justice for their family-related problems.

Discriminatory laws create a sense of powerlessness among women because “every person should receive a just and fair treatment within the legal system” (Muralidhar, Reference Muralidhar2004a: 1). The discrimination that women often face with regard to family law, property, inheritance rights, employment, and so on limits their legal entitlements and so acts as a barrier to justice. This “unjust” and “unfair” access to laws and regulations reflects the necessity of making rights equal so as to ensure legitimacy and credibility of a justice system. Especially for women, a lack of access to equal rights results in a lack of courage and self-confidence, which seem often the greatest obstacles to challenging the injustice.

A “fair treatment” by the legal system is based on substantive justice that aims at eliminating legal discrimination. However, substantive justice needs to extend its scope from a narrow concept of formal equality to initiate laws and policies for gender equality and justice. The realisation of substantive justice requires the positive obligation of the state to ensure equality without distinction on the basis of gender. Therefore, whereas equal treatment by law is essential, the State needs also to address causes, impacts, and outcomes that can marginalise and disadvantage women’s rights and interests. Providing nondiscriminatory legal remedies and effective protection of women’s rights by law thus is a substantive element of access to justice that also promotes gender equality.

Women and Administration of Justice

A black letter law, even where it protects a substantive right, is not enough to provide women with access to fair and effective justice. The law clearly can set a legislative norm to protect women’s interests and rights. However, the access of women to justice also requires access to an effective and fair administration of justice that is able to provide easy access to equal remedies. In Iran, as elsewhere, the quality of justice women receive is equally pertinent in providing fair access to justice. The laws in Iran, while rather diverse and nonbiased, still may fail to protect women’s rights because of the failure of the justice system to provide effective and fair enforcement.

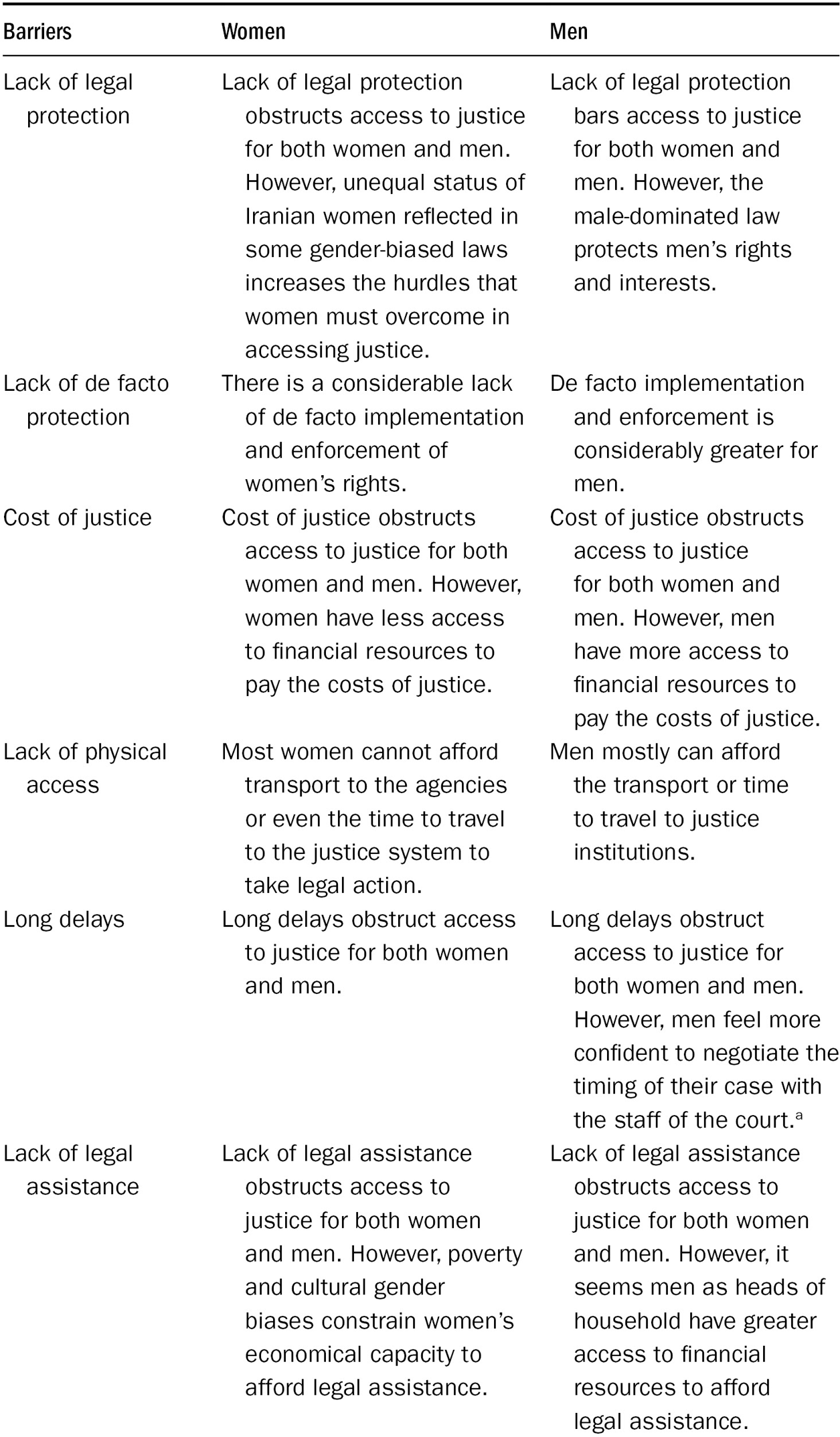

The gender-related barriers to accessing justice are closely associated with the capacity of law enforcement agencies to provide effective legal remedies for women. The barriers, as we discussed in the previous chapter, affect the access of both men and women to justice. It seems, however, that men have easier access to justice than women.26 The institutionalised gender biases and discriminatory norms appear to permeate the administration of justice in particular and therefore create more multilayered barriers that women must overcome in order to access justice. Table 4 illustrates the key barriers and their implications for Iranian men and women in accessing justice.

Table 4. Barriers to Access to Justice for Women and Men

a This negotiation is an informal part of Iranian court procedure. Women are usually powerless and less confident to negotiate, and any attempt made is based on building sympathy.

One important barrier that must be briefly discussed here is the lack of gender sensitivity. In the context of access to justice, gender sensitivity within the justice system is of special significance in a sociolegal setting in which women may have nowhere else to seek protection of their rights. Gender sensitivity generally refers to the ability to recognise women’s equal rights and also to understand the diverse perceptions of gender roles. Most policies concerned with gender sensitivity and access to justice are related to improving women’s capacity to access resources and opportunities in order to overcome barriers to accessing justice. Some policies are also linked to the proportion of female staff within the justice system.27

Gender sensitivity within Iranian justice delivery agencies seems to be minimal. The number of female personnel working within the justice institutions, such as judicial officers, judges, and police and prison officers, although increasing, is still much lower than the number of male personnel (CCA, 2003). This low representation is especially problematic because women are officially barred from being judges. Prohibition started immediately after the 1979 Islamic revolution; this was when women judges were barred from practice. This practice was legalised later on by adding a clause to the constitution, which indicated that only men may become judges. The same clause was approved by the provisional government in 1979 and was added to the constitution28 and, as a result, judgeship became an exclusionary position for men. The ratification was also included in the 1982 judges’ employment law, which stated: “judges are only appointed among qualified men” (Article 2).

The law reform in 1992 facilitated a means for women to sit as assistant judges in some civil courts, but still women were prevented from becoming judges. The judiciary, however, uses “female judges” as an accepted term for those women who sit as assistant judges, judicial advisors, and deputy to the prosecutor. The number of female judges has been reported to be 528 in Iran, out of which 7 are the deputy to the prosecutor, 13 are the judicial deputy, 442 are assistant judges, and 86 serve as judicial advisors.29 Therefore, the number of female judges comprised less than 5 percent of the 7,939 judges that were reported to be service in 2008.30

A related issue needs to be addressed here with regard to the unequal power relationships between men and women judges, which also have an adverse impact on women’s access to justice. In a survey study of how female judges experienced working within a male-dominated system, forty-five respondents were asked to reflect upon their experiences in Tehran, of which thirty maintained that they had to overcome considerable difficulties to become a judge and felt that they were marginalised in the decision-making process (Moazami, Reference Moazami2007). Almost all participants mentioned the unequal power relationships that exist between male and female judges, illustrating examples such as male judges having forced female judges to make official decisions against their own judgement (ibid.).

In addition to the small number of female personnel within the justice delivery organisations, a limited appreciation of women’s rights and an inadequate understanding of gender roles by the male staff of the justice system also negatively affect equal access of women to justice. The crucial role of judges, prosecutors, and police is particularly important in view of gender-based discrimination and violence against women. In the case of domestic violence in particular, family court judges in general are indifferent to women threatened by violence (Nadjafi, Reference Nadjafi2007); thus the reluctance of justice officials to pursue investigations leaves women without any protection from the law. Voiced and unvoiced discrimination by judges or discriminatory practices in law enforcement and by justice officials explain how assumptions regarding gender roles can affect the law and its practice.31

Unfair treatment as a key constituent of procedural justice is more evident concerning accused women and female offenders.32 Discrimination in the treatment of female offenders by the justice system “not only resulted in decreasing the age of those imprisoned, but has also contributed to an increase in the number of women convicted for petty crimes” (ibid., 13). Also, many female offenders believed that “double standards do exist and women are charged with greater severity than their male counterparts” (ibid.). A similar result has been shown by the survey study of women’s access to justice in Afghanistan (Women and Children Legal Research Foundation, 2008), where 75.7 percent of the respondents reported facing some kind of problem with the police or the wider judicial system. The most frequently reported problems – 21.6 percent – have been an absence of hearing or “believing” women’s stories (ibid., 36).

This effect is called the “voice effect,” which is one of the most robust effects in justice literature (e.g., Folger, Reference Folger1977). Most of the women that I interviewed during my survey study placed an emphasis on the fairness of the process. Other correlated studies have also shown that people attach a perceived fairness to procedures that lead to certain decisions (Van den Bos, and Miedema, Reference Van den Bos and Miedema2000). Research studies regarding gender and procedural justice explain that women place more value on procedural justice than men in different contexts (e.g., Sweeney and McFarlin, Reference Sweeney and McFarlin1997; Tata and Bowes-Sperry, Reference Tata and Bowes-Sperry1996). In my fieldwork, examples given by the respondents more often reflected the issues that relate to whether a woman has been given the opportunity to voice her claim. Court procedures, especially the way cases proceed to a hearing and the way women are treated, have an effect on how the female user of justice has experienced fair as opposed to unfair procedures.

Women and Cultural Barriers

This section identifies the debate with regard to social and cultural settings and its significance for the access of women to justice. It discusses how culture imposes on women’s equality beyond substantive and institutional justice. Even when the laws are just and inclusive and operate adequately, women may face enormous difficulties in accessing justice because of discriminatory cultural norms. Any related analysis thus should be able to address cultural paradigms to understand how justice and access have been defined beyond law and order in the social context.

The influence of cultural considerations on women’s access to justice can be determined from the fact that making a legal claim is still not an easy decision to make for many women in Iran. Those women who take legal action are often stigmatised by the community, particularly if they claim against their spouses. Statistics suggest that the divorce rate has gone up steadily, rising by 15.7 percent in 2009 compared with the previous year, against a 2.1 percent increase in marriages, yet divorce is considered socially taboo. Women are more stigmatised by divorce, as illustrated in a Persian proverb: “a woman enters her husband’s house with a white wedding dress and leaves it in a white burial shroud.” In criminal or civil cases initiated by women against male members of their family, there is always a fear of losing face in society and also losing support from the family upon whom women may be economically dependent. As the following case studies illustrate, social stigmatisation creates a sense of powerlessness and emotionally deters women from seeking justice. These are stories of women for whom access to justice was denied by what I would like to call the “culture of injustice.”

The first case involves a young girl who was the victim of gang rape as a form of honour revenge in South East Iran (Sistan and Baluchistan Province). The girl (said to be twelve or thirteen years old) was kidnapped from her school; her teacher and classmates were witnesses to this. The victim was released in her neighbourhood a few hours after the kidnapping. The day after, the police, having been informed by the school, approached the victim’s family but the family denied that any crime had taken place. The police believed that the victim’s family and the gang of rapists were both involved with drug trafficking, which had caused long-held hostility between the two families. The school headmaster later reported the case to the advisor of the province’s governor of women’s affairs. She (the advisor) had several meetings with the victim’s family, begging them to report the crime and in particular to allow the authorities to conduct a medico-legal examination of the crime. The family rejected the request, quoting tradition and cultural norms. To them, seeking legal justice could be used as confirmation for their community that their daughter had been a victim of rape, and her lost virginity could greatly damage the reputation of the family.The case was brought by the advisor of the province’s governor to the National Legal Committee for Women’s Rights in 2004. At that time, I was a member of the committee, which was instigated by the Ministry of Interior to examine the issues regarding the legal protection of women in the different provinces of Iran. In the above-mentioned case, the main question was how to overcome the cultural obstacles in providing access to justice for women where legal protection and administration of justice has the ability to provide a just remedy.33

A more recent case involves Mina, whom I met in 2008.34 Mina was the mother of a four-year-old son, Kamyar, from her marriage to Amir. A few months after their wedding, Amir started to sexually abuse Mina in their home in Karaj (located 20 km to the west of Tehran). “He forced me to do things that I didn’t want to.” And when I asked her what sort of things, she replied: “things that prostitutes do in some brutal videos.” She reported that even during her pregnancy, she was subjected to serious sexual abuse by her husband. “I couldn’t tell anyone. It was a great dishonour for me and my family.” She could bear the violence until she realised her husband was sexually assaulting their four-year-old son. “I saw my poor baby with no clothing on, sitting on the devil’s lap ... I suddenly realised why my Kamyar was terrified to be alone with his dad whenever I had to leave the house.” A few days later, Mina left the house with Kamyar and went to her father’s house. “I couldn’t tell them what he had done to us. What would my father or brothers think of me? It disgusted me to see myself through their eyes ... I just told them I wanted a divorce. I told them Amir had beaten me ... they said that, even so, it could not be serious since I had no bruises on my face.” She desperately wanted a divorce and custody of her son, but her family insisted that she had to return to her husband’s house before “people start to say things that would ruin her reputation.”

Mina came to me for help. She did not want to take legal action against Amir based on sexual violence and abusing their child. “People will stigmatise my poor son and that may remain with him for years. I don’t want to damage his reputation in future ... he needs to be a man of honour.” We had several meetings. I persuaded her that even if she obtained a divorce, the court could award custody to her husband unless he was proven to have been sexually abusive toward the child. Mina’s fear for her son’s safety helped her overcome her fear of social stigmatisation. I arranged an informal meeting with the head of the related family court that had jurisdiction over Mina’s case. Fortunately, the head and his deputy showed support and sympathy. Since marital sexual assault cases are very often extremely difficult to prove in court, they organised a medico-legal examination to provide enough evidence before it was too late (the examination usually needs to be carried out within 72 hours of a sexual assault). A physical examination documented both extra-genital and genital injuries and marks.

I asked Mina to arrange a meeting with her family where we could raise the issue regarding their understanding and support. A day later, her mother called to warn me about “disturbing Mina’s life and dishonouring her family.” She said “the law and the court can’t bring justice to Mina when she has to face blame from society and feel guilty for the rest of her life.” I was not able to contact Mina anymore. I was told that Mina and her son were living in her paternal home. Her extended family was told that Mina and her husband had issues over incompatibility but no legal action was made for divorce and obviously no crime of sexual assault toward Mina and her son was reported. In 2010, I was informed that Mina and her son were still living with her parents, with no sign of redressing violence and injustice.35

These case studies might sound extreme, as they illustrate women in critical situations, but they reflect the fact that many Iranian women often have to overcome cultural obstacles because of traditional gender bias and social stigmatisation in accessing justice. Further empirical evidence concerning gender bias and cultural values and whether or not women perceive cultural norms as a barrier to access to justice are also examined in Chapter 6, which presents the results of the survey study undertaken for this study.

Human Agency in Access to Justice

I begin this section by looking at definitions of empowerment and women’s empowerment. I then move on to the literature that covers legal empowerment to examine how legal empowerment is related to women’s access to justice. I would like to suggest that formal law cannot be an adequate path for women to access justice in the presence of customary practices and sociocultural norms.

Women and Empowerment

The term “empowerment” has been used in various fields, such as education (Freire, 2000), women’s studies (Morgen and Bookman, Reference Bookman1988), and development (Friedmann, Reference Friedmann1992; Narayan, Reference Nasr2002), among other subjects. Empowerment has also become popular in the development field since the mid-1980s. This was a “new buzzword” in international development language but is often poorly understood (Oxaal and Baden, Reference Oxaal1997). Numerous academic studies have been conducted to define empowerment but so far little agreement has been reached (e.g., Friedmann, Reference Friedmann1992). Most of the related international documentation often uses empowerment to promote various social inclusion policies rather than providing a comprehensive conceptual analysis.36 There have also been a large number of research studies regarding the possible measurement of empowerment (Alsop et al., Reference Alsop, Bertelsen and Holand2006; Narayan, Reference Nasr2002). These studies have attempted to examine how empowerment can be reduced to measurable components.

From a measurement perspective, empowerment is mainly about opportunities that people can use to make effective choices and take action. For example, research involving five countries37 and conducted by the World Bank measures degrees of empowerment by examining the capacity to make an effective choice. This capacity “is primarily influenced by two sets of factors: agency and opportunity structure. Agency is defined as an actor’s ability to make meaningful choices; that is, the actor is able to envisage options and make a choice. Opportunity structure is defined as the formal and informal contexts within which actors operate” (Alsop et al., Reference Alsop, Bertelsen and Holand2006: 6).

Literature regarding empowerment most often uses common concepts such as power, control, participation, and making choices to define empowerment. The notion of empowerment in particular has been emphasised through people’s ability to make choices (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer1999). In this context, empowerment is a process of change in the power relationships whereby marginalised and disadvantaged populations make their own life decisions. In other words, “the term empowerment refers to a range of activities from individual self assertion to collective resistance, protest and mobilisation that challenge basic power relations. For individuals and groups where class, caste, ethnicity and gender determine their access to resources and power, their empowerment begins when they not only recognise the systemic forces that oppress them, but act to change existing power relationships.”38 The notion of control also has been emphasised in social work studies originally used by Barbara Solomon (Reference Solomon1976). Solomon defines empowerment as the process by which disadvantaged groups increase power by accessing psychological and material resources, and begin to take control over their lives.

Another line of thought takes into account the different approaches to the process of empowerment. The top-down and instructive approach has been emphasised in the field of welfare reform in the late 1970s. In this perspective, existing social structures, such as neighbourhood, family, church, or voluntary associations, give instructions with regard to what poor people should do for their empowerment because they assume that poor people are powerless and need to be given power (Berger and Neuhaus, Reference Berger and Neuhaus1996: 158). The “bottom-up” approach, on the other hand, operates from below and involves a participatory process toward development (Oxaal and Baden, Reference Oxaal1997; Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Chambers, Shah and Petesch2000). Therefore, empowerment is a bottom-up process and cannot be operated from the top down.

On the subject of women’s empowerment in particular, a study by the World Bank reviews some of the related literature and underlines some similarities between the definitions of women’s empowerment such as “women’s agency” and “process” (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Schuler and Boender2002). This study distinguishes empowerment from power to highlight that women themselves must make choices and exercise control over their lives to be considered empowered. Women’s agency has most often been described by the related literature as an ability to make decisions and exercise control over resources and their lives. Woman’s agency thus is “a capacity or ability to make meaning within a given set of cultural practices which fail to offer a clear and consistent formula for life, but are marked by contradictions” (Naffine, Reference Naffine2002: 86). Process, as another vital element of empowerment, has been emphasised by many writers on the subject (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer1999; Rowlands, Reference Rowlands1995). Process is the progression from gender inequality to gender equality.

Several different efforts have been made in recent years to develop comprehensive frameworks outlining the various dimensions within which women can be empowered (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Schuler and Boender2002). One commonly used index is the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), which measures gender inequality in the areas of political participation and decision making, economic participation and decision making, and power over economic resources. The index refers to women’s empowerment as a similar concept to gender equality by measuring women’s participation at a national level and thus does not include an individual basis. The GEM ranking for Iran is 87 and the value is 0.347; this includes the share of seats in parliament held by women (4.1); female legislators, senior officials, and managers (16); female professional and technical workers (34); and the female economic activity rate (0.39).39

It appears that the GEM provides a very limited reflection of women’s empowerment. An increased percentage of female administrators and managers, for instance, does not represent whether or not Iranian women are empowered in their personal, familial, economic, and political lives. Empowerment of women in Iran includes numerous factors contributing to women’s lives at both national and individual levels.

Legal Empowerment

In recent years, international organisations and development agencies have developed strategies for using the law to help disadvantaged populations have more control over their lives. Although these approaches vary in structure from legal literacy to public interest litigation, they are similar in embracing empowerment as processes.

The concept of legal empowerment emphasises the process and strategies that use “legal services and related development activities to increase disadvantaged populations’ control over their lives.” The phrase “legal empowerment” was suggested by Stephen Golub as a response to the failure of the “rule of law orthodoxy.” Golub argued that Western advocacy for the rule of law has several problems; first, it employs a top-down approach by concentrating on building state-dependent legal institutions. Second, it assumes legal reforms should aim at smoothing the function of the market to eradicate poverty. Third, developing countries are employing international approaches without contextualising those strategies. Fourth, it fails to guarantee access to justice for all by bringing the judiciary to meet people’s needs (ibid., 7–21).

Building on Golub and McQuay (Reference Golub and McQuay2000) and Golub (Reference Golub2003), legal empowerment has been defined as a “process” that increases disadvantaged groups’ control over their lives through use of the law, legal information, and action. Legal empowerment also has been seen as a “goal,” referring to the actual achievements of the disadvantaged groups through the use of law. “The distinction is important, because the process of legal empowerment can proceed even if the goal has yet to be achieved” (Golub and McQuay, Reference Golub and McQuay2000: 26).

In a similar vein, the Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor40 in its final 2008 report, Making the Law Work for Everyone, defined legal empowerment as “the process through which the poor become protected and are enabled to use the law to advance their rights and their interests, vis-à-vis the state and in the market” (2008). The commission recognised two key conditions for legal empowerment; identity and voice. “The poor need (proof of) a recognised identity that corresponds to their civic and economic agency as citizens, asset holders, workers, and businessmen/women. Without a voice for poor people, a legal empowerment process cannot exist” (ibid., 26).

In this context, legal empowerment can be defined as a subjective as well as an objective phenomenon. Most of the related research studies seem to emphasise creation of empowering opportunities such as providing legal aid, legal information, and legal institutions reform (see Narayan, Reference Nasr2002; Golub and McQuay, Reference Golub and McQuay2000). Thus, the objectives of these result-based projects have been categorised as “empowerment.” However, “opportunities are external to the impoverished person, and although providing these opportunities may alter the person’s potential reality, they are not empowering in and of themselves unless they enter into that person’s actual reality” (Brown, Reference Brown2003: 1). Subjective legal empowerment refers to processes that empower individuals to use the law. “In order to be legally empowered a person has to see herself as capable of using legal means for solving the problem” (Gramatikov and Porter, Reference Gramatikov and Porter2010: 6).

Beyond objective or subjective approaches, legal empowerment fundamentally is about power. However, most definitions of legal empowerment avoid “power” and use the term “control” instead. In this perspective, “control may relate to priorities such as basic security, livelihood, access to essential resources, and participation in public decision-making processes” (Golub and McQuay, Reference Golub and McQuay2000: 26). The question here is whether legal empowerment is only about taking legal action and participating in public decision-making processes. This question seems crucial when examining the access of women to justice in Iran. Women should be able to recognise themselves as entitled to make choices and take action. Legal empowerment consequently must include the processes and mechanisms that enable women to perceive themselves as entitled to make choices.

This book defines legal empowerment as a subjective phenomenon that must result in functional objectives. Thus, legal empowerment refers to processes that result in enhancing the self-belief of individuals and, in particular, disadvantaged groups to perceive themselves as citizens entitled to make choices and take action on their own behalf and change the power relationship to have better control over their lives. Law and legal institutions may not always be able to provide access to justice for women, as we discussed earlier in this chapter. Legal empowerment thus seems a promising paradigm for women to have a better understanding of the use of the law in their surroundings and of the sociolegal factors that may make them powerless and marginalised: “when they recognize systemic forces and oppressive surrounding conditions, they step in the process of their empowerment and commit to activities” (Morgen and Bookman, Reference Bookman1988: 4). This notion of women’s agency is also relevant from the point of view of women’s access to justice in Iran, for women who have to face not only substantive and institutional inequality but also cultural gender biases that hinder their access to justice.

The present study uses “woman’s agency” in relation to the ability and strength that Iranian women have demonstrated on their path to justice. However, I do not suggest that Iranian women are responsible for their own actions and have personal duty to be empowered. Certainly there is an urgent need to promote gender equality through law reform, institutional improvement, political recognition of women’s rights, and also to enhance women’s access to resources. These positive changes, while vital in enhancing the access of Iranian women to justice, are not adequate enough to provide equal access to justice, as discussed earlier. Therefore, my emphasis on human agency in access to justice, as the defining criterion of legal empowerment, is mainly related to Iranian women’s individual or collective ability to identify their rights and interests and make strategic choices on their path to justice. From this perspective, the choices that Iranian women make can be highlighted as women’s agency. The “strategic life choices”41 women make on their path to justice, as we see in the survey chapter, show that Iranian women are not powerless and weak in negotiating for justice and standing up for their own individual lives and for the sake of their families. Women’s perceptions of access to justice, also presented in the survey chapter, can lead us to identify their abilities as an agency struggling against gender inequality.

The survey study, however, does not deny the difficulties that women may face in seeking justice. Discriminatory laws, failure of the justice system to provide effective and fair enforcement of rights, biased cultural values, and other barriers as mentioned in this research hinder women’s ability to take legal action. Yet, it is important to appreciate the strengths of women in Iran who struggle to have access to a justice they perceive is more strategic for their families and children. Going to court, for example, may not be considered as a strategic choice for women when dealing with a family-related problem, but talking to a family advisor might be regarded as a strategic action. Most women interviewed in the current study reflected on their role as active agents in negotiating their rights and making strategic choices. The evidence of the current study thus strongly challenges the stereotype image of Muslim women portrayed in Iran as victims of their religion.42

Women’s agency is also a fundamental element of legal empowerment by emphasising women’s strengths, resistance, and strategies to deal with their legal problems. A brief word may be added here regarding some potential aspects of a legal empowerment model in Iran, even though providing a detailed discussion about programming legal empowerment, tools, and mechanisms is beyond the boundaries of this research. Promoting legal empowerment of women may involve a range of different approaches and methods. In this section, however, we shall focus on those approaches and tools that aim at strengthening capacity of women to use the law in their path to justice.

It is important to note that there is no single model for legal empowerment. Legal empowerment programs are likely to vary in different contexts, cultures, and communities of Iranian society. A legal empowerment model for women in Tehran must be different from women legal empowerment in Baluchistan, for instance, where development indicators are much lower than the capital. A road map to women’s legal empowerment in Iran includes three main dimensions:43 (1) the importance of law reform to promote gender equality should be acknowledged; however, focusing on law reform should not reject opportunities to empower women to use the “existing law”; (2) legal services provided by the justice system should be based on the rights and needs of women; (3) the capacity of women as “users of justice” should be strengthened.

Building on the work of Anderson (Reference Anderson2003), I have used the phrase “capacity of women as users of justice” to include the following categories of capacities: capacity to identify legal rights, capacity to identify legal problems, capacity to identify how to claim legal rights, and capacity to identify how to enforce legal rights. Anderson (Reference Anderson2003) suggests different stages of access to justice, as Table 5 demonstrates.

One potential approach to strengthen the capacity of women as “users of justice” to use the law and legal system is to educate them to deal with legal matters. Most of the respondents in the current study, although, could identify the right they were entitled to but they did not know how to enforce their rights.

Another promising mechanism is developing efficient legal aid systems, which need to emphasise legal assistance provided by paralegals and legal aid clinics. As the study presented in Chapter 6 shows, almost all of the respondents had no experience using legal aids and also did not know that some courts and the Bar Association actually provide free legal aids for the poor. Expanding legal aid systems facilitate accessibility of the judicial procedures for women, who have no legal representation. One possible mechanism is establishing paralegal programs at the community level that are missing from Iranian law society. In many countries such as the United States44 or United Kingdom,45 paralegals are not qualified as solicitor or barrister but receive specialised legal training to provide legal advice and assistance. They can supply basic information and legal advice and also assist with representation in administrative processes and litigation.

Beyond expanding legal services to the poor by paralegals, legal aid clinics and clinical legal education can involve law students who provide free legal advice for disadvantaged groups. Clinical Legal Education (CLE) has emerged as a reaction to the failures of the traditional legal education during the last thirty years. This term can be defined as an interactive teaching methodology that aims at learning by practicing and also creating justice values.

In Iran, law school study consists of four years of academic work. There are around 2,390 higher education institutions in Iran, and most of them teach law as a graduate major. Most law schools also adopt an analytical approach to the law as logical doctrine taught principally through lectures. The teaching methodology thus includes lecturing while students read the law from textbooks. Some law schools also use the Casebook Method with focus on judicial decisions and the Socratic Method, which teaches the skill of legal analysis, both derived from American legal education in the nineteenth century.46 From a personal perspective, I also have been trained by a traditional approach to legal education during my graduate study in Iran. I learned about clinical legal education while completing a master’s degree at the Central European University. Upon my return to Iran, I initiated several national projects on the law school’s capacity, building on clinical legal education,47 and also started the first Iranian CLE course in Mofid University, Qom. The course adopted an active learning methodology to teach practical legal skills to the students. The students could apply to work with the Mofid University Legal Clinic where they assist lawyers with family law cases.48 Apart from Mofid University, none of the other Iranian law schools offer “clinical legal education” courses where students act as lawyers under the direction of a faculty member. Therefore, most students have to take a bar examination in one of the provinces upon graduation from law school to be able to practice law. These restrictions on who may provide legal services present an obstacle to more accessible forms of legal services such as paralegals and legal clinics.

There are some problems, however, with developing clinical legal education in Iran. These challenges include: (1) there is a fear that a legal clinic may upset the law school’s relation with the local legal community; (2) there are limited resources regarding qualified clinical teachers, textbooks, financial support, and infrastructural facilities; (3) there is a limited capacity to accommodate interested students within the clinical education program; (4) no credit is given to students who take part in the community work; (5) the local community and especially women are not aware that the law schools provide free legal services; (6) there is a legal restriction on faculty to practice in a court of law and also on students to represent clients in the court; (7) there is a problem with supervising students to provide legal aid; and (8) there exists a lack of involvement of the Bar and the Judiciary. Beyond these problems, there is a great danger that the legal aid services provided to the vulnerable women by the law school may not be adequately gender-sensitive.

However, it may thus be concluded that clinical legal education remains as one of the key themes for enhancing women’s access to justice in Iran. This is mainly because legal aid clinics may provide legal services to women at no cost, especially when Iranian lawyers are not required by law to fulfil any commitment to public service by mandatory pro bono. Clinical legal education may also inspire a commitment to social justice and public interest among the students. Many of my former students from Mofid University continued to contribute to access-to-justice by educating women about their rights and performing pro bono work. Besides, clinical programs may contribute into strategies such as public interest litigation that reflect change in the law itself. As a final point, legal clinics may help explore methods for more effective representation of clients’ interests.49

Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to contextualise the access of Iranian women to justice by examining substantive and procedural justice, sociocultural barriers, and legal empowerment. It reviews gender-specific barriers to access to justice and also illustrates the limits of formal law as a mechanism for providing equal access for women to justice in the presence of discriminatory institutional practices and social norms. The chapter presents similar interrelated components of empowerment, women’s empowerment, and legal empowerment, and suggests that legal empowerment can provide better access to justice for women in Iran. One important conclusion drawn is that women’s empowerment and, in particular, women’s legal empowerment is a multidimensional process and is difficult to measure. Legal empowerment also has different meanings in different contexts; a variable that indicates empowerment in one sociolegal setting is likely to be different in another setting. This chapter concludes the first part of the book regarding the conceptual framework and also a contextualised analysis. Part II of the research study includes two chapters that discuss the methodology, access to justice measurement models, and the findings from the survey study with reference to women’s perceptions of access to justice in Iran.

1 For example, Mehrangiz Kar, a well-known Iranian feminist now living in the United States, believes that the Iranian legal system is inherently incompatible with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). She says, “the Iranian government is based upon Islam, and its constitution states that laws cannot contradict the Sharia. Given that the Sharia does not consider men and women’s rights as equal, its joining the Convention would be problematic” (Fathi, 2007, BBC World Service).

2 An extensive academic and legal scholarship has been produced about the nature of Islamic law and whether it limits women’s rights. For example see Ali (Reference Ali2000); Ahmed (Reference Ahmed1992); Kandiyoti (Reference Kandiyoti1991); and An-Na’im (Reference An-Na’im1990).

3 For a detailed analysis of legal protection of access to justice, see Chapter 3.

4 Adopted at New York on 18 December 1979; Entered into force on 3 September 1981. UN GA Res. 34/180, 34 GAOR, Supp. (No. 46) 194, UN Doc. A/34/46, at 193 (1979), 2 U.K.T.S. (1989); 19 I.L.M. (1980) 33.

5 Article 21 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

6 For a detailed discussion, see Chapter 3.

7 References about discriminatory articles in the Penal Code and the Civil Code are provided in the following discussion.

8 Penal Code, Article 49.

9 Civil Code, Article 1210.

10 Penal Code, Article 170.

11 Penal Code, Articles 117, 119, and 128.

12 Penal Code, Article 137.

13 Article 76.

14 Article 237.

15 Under Islamic criminal law, Qisas crimes (murder, intentional and unintentional physical injury, and voluntary and involuntary killing) involve the sanctions of retaliation or compensation.

16 Islamic Penal Code, Article 15.

17 Islamic Penal Code, Article 300.

18 Article 1042, Civil Code.

19 Article 1130, Civil Code.

20 Article 1129, Civil Code.

21 According to Article 1146 of the Civil Code: “A Khula divorce occurs when the wife obtains a divorce owing to dislike of her husband, against property which she cedes to the husband. The property in question may consist of the original marriage portion, or the monetary equivalent thereof, whether more or less than the marriage portion.” Article 1147: “A Mubarat divorce occurs when the dislike is mutual in which case the compensation must not be more than the marriage portion.”

22 Civil Code, Article 907.

23 Penal Code, Article 137.

24 Civil Code, Article 1169.

25 Civil Code, Article 1170.

26 Most of the respondents of the survey study presented in Chapter 6 thought that men have easier access to justice.

27 For a detailed discussion, see UNDP (2007), “Gender Equality and Justice Programming: Equitable Access to Justice for Women,” accessed 25 March 2010, available online at http://www.undp.org.ir/gender/Equitable%20Access%20to%20Justice_EN-EBOOK.pdf.

28 Article 163 of the constitution lists the characteristics of judges without specifying a man or a woman.

29 Statistic provided by the Ministry of Justice in year 2008, accessed 23 April 2011, available online at http://isna.ir/isna/NewsView.aspx?ID=News-1677323.

30 Ibid.

31 As stated by former Chief Justice of India, “In recent years, the role of judiciary has extended beyond issuing directions on social issue concerns to ensuring effective and fair implementation of the same. As a judge this requires elimination of subtle ways in which the courtroom perpetuates discrimination and violation of women’s right.... As judges we need to be proactive and take charge of our courtroom to ensure that the subtle ways of discrimination through spoken and unspoken words are eliminated” (Anand, Reference Anand2004: 12).

32 Procedural justice examines both formal procedures (e.g., laws and legal proceedings) and informal procedures (e.g., being given permission to be heard) to measure whether the fairness of procedures has lead up to the distribution of certain outcomes (Van den Bos, Reference Van den Bos2005: 273–300).

33 All case documents are archived by the National Legal Committee for Women’s Rights, the Ministry of Interior in 2004. Despite several attempts to gain access to the case documentation, official reports were not available to the researcher.

34 The names have been changed to protect the parties’ confidentiality and privacy.

35 To maintain ethical principles, in particular confidentiality and privacy of the victims, the researcher is not able to provide complete reference.

36 See some of the United Nations documents, particularly about women’s empowerment such as the Association for Women in Development (Everett, 1991), the Declaration made at the Micro-credit Summit (RESULTS 1997), (UNICEF 1999), and DFID (2000).

37 Brazil, Ethiopia, Honduras, Indonesia, and Nepal.

38 Batliwala (Reference Batliwala1994).

40 The Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor was established in 2005 by UNDP, and after three years of research, the commission suggested strategies for empowering those living in poverty through providing voice, identity, access, and protections of rights.

41 “Strategic life choices” refers to decisions that affect women’s lives such as decisions related to marriage, divorce, childbearing, education, and employment. Empirical studies often suppose that the ability to make strategic choices will be demonstrated in an ability to make day-to-day decisions (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Schuler and Boender2002).

42 To read more about Muslim women as active agents see Starr (Reference Starr1992).

43 The suggested “model” is based on the findings of the survey study presented in next chapter.

44 “A legal assistant or paralegal is a person qualified by education, training or work experience who is employed or retained by a lawyer, law office, corporation, governmental agency or other entity who performs specifically delegated substantive legal work for which a lawyer is responsible.” Under this definition, the legal responsibility for a paralegal’s work rests directly and solely upon the lawyer”(definition by American Bar Association, accessed 27 February 2011, available online at http://apps.americanbar.org/legalservices/paralegals/def98.html).

45 “A person who is educated and trained to perform legal tasks but who is not a qualified solicitor or barrister” (United Kingdom’s National Association of Licensed Paralegals, accessed 27 February 2011, available online at http://www.nationalparalegals.com/nalp.htm).

46 See McManis (Reference Rosen1981).

47 In January 2007, I did coordinate a visit of Iranian law schools and Bar Association of the Campus Law Clinic and Street Law program at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa. The South African experience provided the Iranian delegation with a pragmatic overview and general idea about clinical legal education. On 19 June 2007, the First International Conference on Clinical Legal Education was held in Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran. A brief summary of the conference is available online at http://www.sbu.ac.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=552&ctl=Detail&mid=1612&Id=730, accessed 25 May 2011.

48 The legal aid clinic of Mofid University has since been developed to teach students effective legal skills. The Mofid clinic also renders assistance to indigent clients on family law, labour law, and criminal law. See legal aid clinic of Mofid University, accessed 10 February 2011, available online at http://lcmu.ir/.

49 For a detailed discussion see Charn (Reference Charn2003).