3 Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Divided Heart of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

No one had ever seen anything like it. Five thousand copies flew off the shelves the week it was published. Three hundred thousand more had sold in the United States before a year was up, easily eclipsing previous sales records. The novel was translated into French, German, Spanish, Polish, and Magyar – and soon global sales exceeded one million. Popular demand for the book proved so strong, in fact, that the production staff in the United States worked around the clock. “Three paper mills are constantly at work, manufacturing the paper, and three power presses are working twenty-four hours per day, in printing it, and more than one hundred bookbinders are incessantly plying their trade to bind them, and still it has been impossible as yet to supply demand,” announced its publisher John P. Jewitt breathlessly. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life among the Lowly was the publishing phenomenon of the nineteenth century.1

Remarkable as these numbers are for the time, they fail to capture the full impact of Stowe’s first book. Novel reading, after all, was often a social event in the antebellum period, as whole families would sit down before a roaring fire to listen to stories read aloud. Contemporaries reasoned, therefore, that the true size of Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s audience greatly exceeded the number of copies sold. “Uncle Tom has probably ten readers to every purchaser,” hazarded the Literary World.2 Well before the advent of modern mass marketing campaigns, the book gained a level of cultural prominence that would make even a twenty-first century Madison Avenue advertising executive jealous. One London newspaper reported that the United States and Great Britain were gripped by “Tom-Mania” in the years after its 1852 publication. Stowe’s characters and plotlines surfaced in songs, plays, and unauthorized novels as well as merchandise ranging from paintings, puzzles, and cards to ornaments, board games, and dolls. Dry goods shops and creameries in London were named “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” while one could buy Uncle Tom’s Candy in Parisian stores.3

Abolitionists, no surprise, were thrilled by the spotlight Stowe shined on slavery’s human costs. At an 1853 Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society meeting, Theodore Parker announced that Uncle Tom’s Cabin “has excited more attention than any book since the invention of printing.” Wendell Philips went a step further, calling it “rather an event than a book.”4 Estimations of the novel’s influence eventually reached dizzying heights. Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow judged it “one of the greatest triumphs recorded in literary history, to say nothing of the higher triumph of its moral effect,” while Higginson maintained that “of all the blows which slavery received, none was so great as that delivered by this tale of ‘life among the lowly.’”5

Countless Americans attributed the coming of the Civil War to Stowe’s work. Basking in the glory of victory, Northern voices tended to celebrate the novel’s role in galvanizing antislavery forces. Uncle Tom marched “all through the conflict, up and down,” declared Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in a poem he wrote for Stowe’s seventy-first birthday celebration. Some southerners also viewed the war as the logical outcome of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but, in the wake of defeat, they heaped scorn upon Stowe. An editorial in the Montgomery Advertiser called her “an unchristian, an unfeminine creature,” who “so fatally contributed to all the dire consequences of civil war in this country.” More positively and famously, Abraham Lincoln, on meeting Stowe in 1862, was supposed to have said, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war!” Whether Lincoln ever used these words – and recent research suggests that the anecdote merits a hefty grain of salt – they nonetheless reflect a broadly shared sentiment in the nineteenth century: Stowe’s book changed the young nation.6

But why? What accounts for the unprecedented popularity and impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Stowe believed that it was the novel’s divine inspiration; scholars offer secular explanations. David Reynolds explicates how Uncle Tom’s Cabin drew on the diverse forms of popular culture that prevailed in antebellum America, including “visionary fiction, biblical narratives, pro- and anti-Catholicism, gender issues, temperance, moral reform, [and] minstrelsy.” Meanwhile, Ronald Walters highlights the ease with which Stowe’s “vivid characters, comic interludes, and melodramatic storytelling” could be divorced from her antislavery message, thereby enabling people who cared little for the cause of the slave to appreciate the book and its many imitations. Finally, James Brewer Stewart focuses on the ways in which the novel “satisfied every antislavery taste.” Nonresistants gravitated toward the pious, pacifist Uncle Tom, just as militants found the armed George Harris attractive. And racist Free Soilers, for their part, simultaneously laughed at Stowe’s racial stereotypes and nodded approvingly at her free labor critiques of plantation life and gestures toward colonization.7

Like most popular works of art, then, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was influenced by the cultural modes and tropes that were fashionable in its day. Nowhere is this more evident than in Stowe’s imaginative combination and reconfiguration of different types of high and popular romanticism. The major romantic chord struck by Stowe was her sentimental appeal. As Parker insisted in 1853, the “triumph” of Uncle Tom’s Cabin “is not due alone to the intellectual genius and culture of the writer; it is due to a quality far higher and nobler than mere intellect.... She has won this audience because she has appealed to their Conscience, because she has touched their Hearts, because she has awakened their Souls. She has brought justice, love and piety to bear the burden which her genius imposed upon them.”8 Stowe artfully repackaged the antislavery tactic most associated with early romantic reform (moral suasion) into what had become, by the 1850s, a wildly popular form of expression in the United States: the sentimental novel.

Like Garrisonians, Stowe aimed to convert her readers to the cause of the enslaved. But Stowe’s appeal to the hearts and minds of America discarded much of the vitriol that characterized the writing of first-generation romantic reformers. Emphasizing the shared humanity of white and black Americans rather than the wickedness of slaveholding, Stowe wove a stirring moral drama about slavery out of the familiar threads of a sentimental literature. Even more, by placing pious and suffering Uncle Tom and Eva at the center of her novel, Stowe hitched pacifist moral suasion to other romantic points of emphasis, including sentimental identification, romantic racialism, and the idealization of childhood.

Stowe counterbalanced Tom and Eva’s tragic stories with the daring and more traditionally heroic exploits of George and Eliza Harris. These resistant rebels prove themselves unwilling to submit to bondage, even in the face of death. Their stories, in turn, prove Stowe’s unwillingness to settle on a single answer to the problem of slavery. Tom and Eva’s suffering lights an antislavery fire in the hearts of several of the characters, a response Stowe hoped to provoke in her readers, helping them, as she put it, “feel right.”9 The failure of these conversions to topple the institution of slavery within the novel, however, highlights the fact that Stowe herself was uncertain about whether moral suasion could bring slavery to a close. In contrast, George and Eliza Harris – who not only escape to the North but also forcefully resist those who would return them to bondage – suggest that the novelist had an open mind when it came to what to do about slavery. Reluctant to sacrifice themselves, the Harrises force Stowe’s readers to wrestle with the question of whether opponents of slavery should concentrate on moral suasion or take the fight more directly to the institution’s supporters. Taken together, these heroic archetypes – the sentimental martyr and the resistant rebel – reveal Stowe’s ambivalent, multilayered, antislavery thinking.

Ambivalence, to be sure, was not unreasonable in a tumultuous age. But Stowe had a particularly acute case. The daughter of Lyman Beecher, perhaps the most influential preacher of the early nineteenth century, she was, on the one hand, the product of her father’s modified Calvinism. Quick to minimize her own agency, Stowe gave credit to a higher source for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. On the other hand, her novel stressed not the awesome power of God but rather the ways in which Christians who opened their hearts to Jesus Christ could almost become divine themselves. This message reflected an altogether different context – what Emerson called “the age of the first person singular” – in which somber Calvinist notions of original sin and a limited elect seemed anachronistic holdovers from a bygone era.10 Viewed this way, Uncle Tom’s Cabin spoke directly to perfectionist America.

Unlike her fellow New Romantics, however, Stowe had doubts about the demands of perfectionist striving as well as the likelihood of achieving a state of spiritual perfection. She had misgivings as well about her lifelong interest in popular and elite romantic currents. As a young girl, Stowe had plowed through the works of Byron and Scott, which both tantalized and disturbed her. After befriending Byron’s widow, she wrote a scathing essay to excoriate the English poet for his incestuous infidelity.11 In similar fashion, Stowe was drawn to – and repelled by – the religious theories of German Romantics such as Schleiermacher and Schelling and their Transcendentalist counterparts. She appreciated the weight that romantic theology attached to intuition and feeling, though she had significant reservations about the liberal hermeneutics of ministers like Parker. As was the case with so much in her life, Stowe wrestled with romantic modes and ideas, accepting parts, rejecting others. In these struggles, she proved herself to be, if anything, a representative New Romantic.

Growing Up Calvinist in the Age of Byron

Born on June 14, 1811 in Litchfield, Connecticut, Harriet Beecher Stowe was the seventh child of Lyman and Roxana Beecher. Stowe’s mother died from tuberculosis when she was just five years old, leaving her imposing father Lyman the central influence in the novelist’s early life.12

Among the nation’s most influential clergymen, Beecher preached a modified version of New England Calvinism. As a young minister, he clung tightly to the doctrine of original sin, telling his parishioners and family that unless touched by God they were doomed to damnation. Beecher dispensed similarly stern sentiments at home. “Henry, do you know that every breath you breathe is sin?” he asked Stowe’s younger brother when he was just a toddler. “Well, it is – every breath.”13

Yet Beecher also softened Calvinism’s sharpest edges. His alteration of the catechism, “No mere man since the fall is able perfectly to keep the commandments of God” to “No man since the fall is willing to keep the commandments of God,” demonstrates the distance between John Edwards’s austere Calvinism and Beecher’s more hopeful stance. While Edwards thought all men shared Adam’s original sin, Beecher stressed humankind’s vast, if largely unrealized, potential.14

Although Beecher’s theology tacitly undermined the absolute sovereignty of God, he did not go as far along this line as liberal Christians, who were gaining a foothold in New England, not to mention radicals like Parker. Indeed, in the mid-1820s he moved his family from Litchfield to Boston in hope of saving a city that he believed was under siege from within. “Calvinism or orthodoxy was the despised and persecuted form of faith” in Boston, Stowe explained decades later. “All the literary men of Massachusetts were Unitarian. All the trustees and professors of Harvard College were Unitarians. All the élite of wealth and fashion crowded Unitarian churches. The judges on the bench were Unitarians.” Her father hoped to prevent this liberal tide from engulfing the symbolic seat of New England Puritanism.15

The following decade Beecher opened a western front in his holy war, taking the presidency of Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati. There, he battled with the city’s Catholic population and later had a falling out with – and effectively drove off – evangelical abolitionists led by Theodore Weld. Beecher reveled in this fight over the spiritual future of America. “I was built for war,” he boasted.16

Beecher’s heroic self-posturing had as profound an impact on his family as did his modified version of Calvinism. Facing the daunting Unitarian establishment in Boston, he alone seemed to hold up the orthodox mantle. “It was the high noon of my father’s manhood,” Stowe wrote, “the flood-tide of his powers.”17 Her father also described his decision to leave Boston for Cincinnati in epic terms. “If we gain the West, all is safe,” he told his daughter Catharine, “if we lose it, all is lost.” Harriet displayed this sort of romantic affectation too. “The heroic element was strong in me,” she once noted, “having come down by ordinary generation from a long line of Puritan ancestry, and just now it made me to do something, I knew not what: to fight for my country, or to make some declaration on my own account” (Figure 3.1).18

European Romantic currents fed the Beechers’ proclivity for heroic self-posturing. Although poetry and prose were forbidden fruit in many Calvinist households, Beecher and his children were well versed in the popular English Romantics. Later in life, Stowe recalled her father telling her brother George, “You may read Scott’s novels. I have always disapproved of novels as trash, but in these is real genius and real culture, and you may read them.”19 While the more philosophical Romantics, such as Schelling and Coleridge, held little appeal for the Beecher family, they reveled in the work of accessible Romantic writers and poets, especially Scott and Lord Byron.

Stowe discovered Byron’s work in the home of her Aunt Esther, who lived but a half-minute walk from the Beecher home in Litchfield. Eventually the English Romantic would become, in the words of literary critic Alice Crozier, “the single greatest literary and imaginative influence on the writings of Harriet Beecher Stowe.” Lyman was also smitten with Byron. “My dear, Byron’s dead – gone,” he said when he learned of the poet’s passing. “Oh, I’m sorry that Byron is dead. I did hope he would live to do something for Christ.”20

The Beecher family’s exposure to European Romanticism was due in large part to Roxana’s brother Samuel Foote, a worldly sea captain who returned from his journeys with the latest continental poetry and prose. Stowe and her brothers and sisters devoured these exotic morsels. Catharine Beecher mimicked Sir Walter Scott’s ballads, while her more famous sister had an entire “Walter Scott bookcase” as an adult. Stowe was also drawn to Madame de Staël’s Corrine, which she used to plumb the depths of her dissatisfaction in more despondent moments. She even ascribed an innate moral sensibility to European Romantics, despite their ethical failings. “Moore, Byron, Goethe, often speak words more wisely descriptive of the true religious sentiment, than another man, whose whole life is governed by it,” she maintained in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.21

Popular Romantic poetry and prose were but one part of the uncommon education the novelist enjoyed as girl. From an early age the Beecher family recognized her sharp mind and sought to hone it. She studied mathematics, geography, moral philosophy, and logic at Litchfield Female Academy. Later, she mastered rhetoric, oratory, history, Latin, and Greek at her sister’s Hartford Female Seminary, where she spent eight years as a student, teacher’s assistant, and, finally, an instructor of rhetoric and composition.22

During these years, Stowe struggled with the implications of a second romantic impulse – moral perfectionism – which had roots closer to home. In the decades before the Civil War, Americans across the country, from the polished parlors of Boston to frontier towns of the Wisconsin Territory, sought to make themselves perfect. Perfectionism had a profound impact on social reform in America, fueling the temperance and abolitionist movements, among many reform efforts, and leading to the creation of utopian communes like the Oneida Community and Brook Farm. While Emerson’s essays and Parker’s sermons set a perfectionist tone for liberal Christian circles, its most famous exponent among evangelicals was Charles Grandison Finney, a Second Great Awakening preacher who fanned the flames of evangelical revival in the United States and Great Britain like no other. Finney and his followers embraced the doctrine of sanctification, or Christian perfection, which held that human beings had the ability – and the duty – to try to purify themselves and live sin-free lives.23

Lyman Beecher rejected perfectionism outright. Nevertheless, as Joan Hedrick has written, “his brand of Calvinism, by opening the door for the exercise of free will, let perfectionism sweep in behind.” And this exacting ideal, for all its social utility, could wreak havoc on individuals, especially sensitive souls like Stowe and her brother George, who were already burdened with the demands of Calvinist introspection. Decades after waging what he called “interminable warfare” with himself in search of “complete and perfect sanctification,” in fact, George shot himself in the head with a shotgun in his Ohio garden. Although the local coroner concluded that this 1843 death was an accident, most modern scholars believe that it was more likely the result of a manic-depressive mind, exacerbated by the personal toll of the culture’s perfectionist impulse.24

Like her brother George, Stowe strove to make herself perfect while doubting whether she – or anyone else – could live up to such a standard. She had difficulty, for one, living up to the demands of the Victorian middle-class household, in which a woman was expected to provide a haven for her family from the stresses of the modern world. After marrying Calvin Stowe, a biblical scholar she met in her father’s Cincinnati seminary, she complained regularly of the toll of trying to be the ideal wife and mother. “The arranging of the whole house ... the cleaning etc., the childrens[’] clothes & the baby often have seemed to press on my mind all at once,” she wrote Calvin in 1844. “Sometimes it seems as if anxious thoughts has [sic] become a disease with me from which I could not be free.”25

Stowe felt this perfectionist angst more acutely when it came to spiritual matters. Her letters to friends and family from the 1820s through the 1840s testify to an abiding desire to find spiritual quiescence. “Religious feeling ... and social affection seem all to be smothered in the same – murky vapours,” she wrote George at one point. Stowe admitted that she felt “no sympathy for others – no desire[,] no wish except to lie down & lie still forever more.” As an adolescent, she had experienced a spiritual conversion that she hoped would put to rest her anxiety, but a local pastor convinced the would-be convert that she had deceived herself. Stowe’s torment returned swiftly. “My whole life is one continual struggle,” Stowe lamented, “I do nothing right.”26

Two decades later, Stowe experienced a second conversion. Having recently lost George and facing an ill child whom she was unable to comfort, she felt helpless. Just as Stowe seemed to hit bottom, however, “when self-despair was final ... then came the long-expected and wished help,” she wrote in March 1844. “My all changed – Whereas once my heart ran with a strong current to the world it now runs with a current the other way.... The will of Christ seems to me the steady pulse of my being & I go because I cannot help it. Skeptical doubt cannot exist ... I am calm, but full – everywhere & in all things instructed & find I can do all things thro Christ.” Reduced to a state of despair, Stowe lost herself in Christ and, in the process, she finally found spiritual solace. Although her religious doubts did not fade entirely after this conversion, Stowe found a bedrock of faith in a Christ-centered vision of suffering and salvation.27

Submit to divine guidance, she urged her husband in the months after the experience, “learn to know Christ & be transformed by him.”28 Jesus was universal and immanent, she believed, enabling individuals to do his work if only they opened their hearts to him. Stowe developed this Christocentric theology further in the pages of the New-York Evangelist, for which she had begun to write after relocating to Cincinnati with her family. Christians, she held, should resist the temptation to judge others by their own standards for there are too many different “style[s] of living” to isolate a clear set of spiritual guidelines. “We know of but one safe rule: read the life of Jesus with attention – study it ... live in constant sympathy and communion with him – and there will be within a kind of instinctive rule by which to try all things,” she concluded.29

Stowe emerged from despair following George’s suicide by becoming one with the martyred Christ, whom she styled, “a captain whom suffering made perfect.” Five years later, she once again found divine strength through pain when she lost her young son Charley to cholera. “Poor Charley’s dying cries and sufferings rent my heart,” lamented Stowe. Yet through “the baptism of sorrow we come to a full knowledge of the sufferings of God – who has borne for us all that we bear.” To Stowe, Charley’s death, like George’s suicide, had been “one more great lesson of humanity which must needs be learned to attain perfection.”30

Stowe turned repeatedly to the phrase, “the baptism of sorrow,” to describe the experience of divine grace in the years after Charley’s death.31 At the same time, she believed that Christians attached too much weight to dramatic moments of conversion. Do not look for God merely in times of despair, she advised readers of the New-York Evangelist. Instead, she counseled them to seek celestial fellowship in everyday events. “To the Christian that really believes in the agency of God in the smallest events of life,” Stowe wrote, “the thousand minute cares and perplexities of life become each one a fine affiliating bond between the soul and its God.” Nearly a decade later, Stowe expanded on this vision in her 1859 novel The Minister’s Wooing. “There is a ladder to heaven,” she wrote, “whose base God has placed in human affections, tender instincts, symbolic feelings, sacraments of love, through which the soul rises higher and higher, refining as she goes, till she outgrows the human, changes as she rises, into the image of the divine.” In this passage, Stowe seems to break with her father’s brand of Calvinism and mainstream evangelical thinking, both of which put great stock in the conversion experience. Her conception of salvation as the steady growth of the soul toward the divine, in fact, sounds like something that Parker or Douglass might have said.32

By the mid-1840s, Stowe had begun to find common ground with these New Romantics on a variety of fronts. Her husband Calvin had exposed her to the same German Romantic theology that helped to ignite the miracles controversy in Boston. The couple sat up late at night discussing the religious theories of Schleiermacher and Schelling. Like Parker, Ripley, and their Transcendentalist colleagues, Harriet and her husband believed that intuition and feeling were the foundation of religious truth. And these ideas, as the Stowes well knew, were far more heretical in their conservative circles than they were in liberal Boston. “There is not a soul that I can say a word to about any of these matters,” Calvin confessed to his wife in 1842.33

Stowe also shared the Transcendentalists’ vision of a loving deity, whose divine spirit was immanent in nature. “Do not think of God as a strict severe Being,” she once told a student at her sister Catharine’s academy. “Think of him as a Being who means to make you perfect ... who looks on all you say and do with interest.”34 When Stowe visited Niagara Falls, she was moved by its natural splendor and cascading power. “Oh, it is lovelier than it is great; it is like the Mind that made it: great, but so veiled in beauty that we gaze without terror,” she wrote. “I felt as if I could have gone over with the waters; it would be so beautiful a death; there would be no fear in it. I felt the rock tremble under me with a sort of joy.”35 This conception of a benevolent deity, in turn, led Stowe to question the fire-and-brimstone sermons of orthodox ministers, which she called the “refined poetry of torture.” Why, she wrote Edward, should we tell sinners that God hates them? She endorsed an altogether different message: “Is it right to say to those who are in deep distress, ‘God is interested in you; He feels for and loves you?’”36

Stowe even turned orthodox Calvinist ideas about original sin and infant damnation on their head, contrasting the pristine virtue of the newborn with the wrongs perpetrated by adults. Children, she insisted, were born pure; it is “the world” that defiles them. Here she seemed to echo a position outlined by Parker just a few years earlier. In a controversial series of lectures on religion delivered across New England and later published as A Discourse of Matters Pertaining to Religion, the Transcendentalist worried that the divine inspiration of youth fades with time. Too many adults, he maintained, “cease to believe in inspiration,” counting “it a phantom of their inexperience; the vision of a child’s fancy, raw and unused to the world.” Age, Parker lamented, does not always beget wisdom when it comes to spiritual matters.37

Despite these many affinities, Stowe was no Transcendentalist. She preferred, for one, a literal interpretation of the Bible to the liberal hermeneutics of Parker or George Ripley. After carefully reading Parker’s sermons, Stowe admitted that her “respect & esteem” for the minister increased. She could not stomach, however, his doubts about the inerrancy of the Bible or professions that Jesus Christ was human rather than divine.38 Stowe also had reservations about the perfectionist impulse. While Parker and Douglass held that all people had divine potential, she believed that “saintly elevation” was possible for only the “few selectest spirits ever on earth.” As such, the quest to make oneself perfect spelled an endless cycle of spiritual torment for the rest of humanity, leaving some “to long for death as the end alike of their struggles and their sins!”39

It took years, but Stowe made her peace with perfectionism, though only by moving away from the humanist version espoused by liberal perfectionists. Christians, she concluded, should put aside their paralyzing questions about whether “entire perfection” was attainable and rest assured that, as the New Testament illustrates, a “state of feelings ... high enough” has – and thus can – be achieved. The solution to the perfectionist dilemma was simple: Make yourself one with Jesus, be absorbed by his love, “say, I am crucified with Christ, yet I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me.”40 Whereas Parker counseled his parishioners not to love “Christ better than man,” Stowe believed that the path to personal sanctification was to surrender to Jesus Christ. Whereas Emerson touted self-reliance, Stowe put greater weight on the assistance that God could provide to would-be perfect souls. “God’s existence, his love and care,” she argued, “seem to us more real than any other source of reliance.”41 Although a perfectionist, Stowe refused to collapse the distinction between humanity and the divine.

Nevertheless, it is telling that Stowe could be confused, if only for a moment, for an Emerson or a Parker. Reared in an orthodox household, she had broken with her father on a number of fronts by the 1840s. Stowe formulated a Christocentric religion of the heart, which bore little resemblance to Beecher’s theology, not to mention that of his Puritan forebearers. And her early interest in Byron and Scott – the seeds of which Lyman himself had helped to plant – had matured into an exploration of new modes and concepts, ranging from evangelical perfectionism to German Romantic theology to Transcendentalist theories of childhood. The Calvinist’s daughter became a romantic. Soon she would break with Lyman Beecher on yet another front: What to do about the problem of slavery.

Moral Suasion, Recast

Stowe believed that her son Charley’s death was a pathway to heaven, bringing her closer to Christ through “the baptism of sorrow.” This distraught mother was also convinced that she needed to use the trying experience to effect changes on earth. “There were circumstances about his death of such peculiar bitterness, of what might seem almost cruel suffering, that I felt I could never be consoled for it, unless it should appear that this crushing of my own heart might enable me to work out some great good to others,” Stowe confessed. That “great good,” of course, was Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Between her son’s death in 1849 and late 1852, the novelist wrote the nineteenth century’s most socially impactful novel. As her book steadily captured the imagination of the Western world, Stowe insisted that it “had its root in the awful scenes & bitter sorrows of that summer.” The loss of a child exposed Stowe to what she determined was the most tragic component of slavery. “It was at his dying bed, and at his grave,” she wrote of Charley, “that I learned what a poor slave-mother may feel when her child is torn away from her.”42 Soon Stowe would help millions of readers get a glimpse of such loss and pain.

While Charley’s passing helped Stowe forge a common emotional bond with slave mothers separated from their children, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 provided the political context that compelled her to explore those emotions on paper. Like her fellow New Romantics, Stowe was transformed by the measure that put thousands of northern blacks’ freedom at risk, while punishing those who assisted them. Despite the new law’s obvious moral failings, she lamented, ministers – men of God – flocked to support it. “To me it is incredible, amazing, mournful!!,” wrote Stowe in December 1850. “I feel as if I should be willing to sink with it, were all this sin and misery to sink in the sea.”43

Stowe had not always been willing to sacrifice her life if she could take down slavery with it. Early on, she had followed her father’s more moderate cues. A member of the American Colonization Society (ACS), Lyman Beecher believed that immediate abolitionists like Garrison went too far. His refusal to support Theodore Weld and a group of Lane seminarians who wanted to debate the merits of colonization and immediatism, in fact, had sparked an exodus from the school in the mid-1830s. By that point, however, Stowe had begun to drift away from her father on the slavery question. In the decade that followed, she advocated the creation of an “intermediate society” between abolitionists and colonizationists and started writing antislavery essays for periodicals such as the New-York Evangelist.44

The new fugitive slave law solidified her commitment to the antislavery cause, a point she made clear in a letter to her sister Catharine. “Dear Sister,” she wrote, “Your last letter was a real good one, it did my heart good to find somebody in as indignant a state as I am about this miserable wicked fugitive slave business.” Overwhelmed by “pent up wrath” toward northern apologists for the law, Stowe scoffed at the grounds on which politicians such as Daniel Webster and Henry Clay made their famous appeals for compromise, writing, “The Union! – Some unions I think are better broken than kept.” Then Stowe relayed the details of a recent encounter with Thomas Upham, a professor of mental and moral philosophy at Bowdoin College and long-time member of the ACS. After Calvin accepted a faculty appointment at Bowdoin in early 1850, the Stowe family had moved to Brunswick, Maine. Harriet had befriended the professor and his wife only to find the relationship strained over the issue of slavery. Upham, she seethed to her sister Catharine, believes that the United States “ought to buy [all the slaves] with the public money & send them off – & until that is done he is for bearing every thing in silence – stroking & saying ‘pussy pussy’ so as to allay all prejudice & avoid all agitation!” On one visit to the Upham household, Stowe confronted her host. Would you obey the fugitive slave law, she asked, if a runaway came knocking on your door? Upham “laughed & ... hemmed & hawed” without offering a clear response, but his young daughter Mary announced, “I wouldnt I know.’”

As fate – or, more likely, the dictates of a good yarn – would have it, a fugitive slave headed for Canada was directed to Upham’s doorstep the very next day. Despite his prior equivocation, the professor promptly brought the runaway to his study, listened to his story, and gave him a dollar. After his wife Phebe provided the fugitive with provisions, the runaway was shuttled off to the Stowe household to spend the night before moving on to Canada. This story, which not only validates Stowe’s abiding faith in the innate moral compass of children but also provides an all-too-timely life lesson for Professor Upham, seems too good to be true. Apocryphal or not, it highlights a critical theme that Stowe would shortly develop at length: that individuals’ “hearts are better on this point than their heads.”45

On March 9, 1851, Stowe contacted Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the Washington-based antislavery weekly the National Era, about a story she had in mind. “Up to this year I have always felt that I had no particular call to meddle with this subject,” she wrote, “and I dreaded to expose even my own mind to the full force of its exciting power.” But the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had compelled her to act. “I feel now that the time is come when even a woman or a child who can speak a word for freedom and humanity is bound to speak,” she held. According to family legend, Stowe’s decision to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin was provoked by a letter she received from her sister-in-law Isabella. “Hattie,” Isabella wrote, “if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something to make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” Stowe, her children later remembered, read this letter to her family in the parlor of their home in Brunswick. When Stowe came to the passage urging her to take up her pen, the matriarch announced, “I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.... I will write something. I will if I live.”46

From June 1851 to April 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared weekly in the National Era, earning a book contract before the serialization was even completed. Stowe attributed the novel’s extraordinary success not to her own literary efforts and talent but to divine inspiration. In late 1852, as the novel was breaking global sales records, she wrote a public letter to a Scottish fan, which was printed in the New York Times. “For myself, I can claim no merit in that work which has been the cause of this,” she insisted. “It was an instinctive, irresistible outburst.... I can only say that this bubble of my mind has risen on the mighty stream of a divine purpose, and even a bubble can go far on such a tide.” In her later years, she told a neighbor, “I did not write it.... God wrote it.... I merely did his dictation.”47 Whether such gestures reflect her humility or a genuine feeling that God had worked through her is impossible to know, although the latter seems likely. Regardless, her stance as a writer reflects the distance between Stowe and many of her New Romantic counterparts, who preferred to attribute accomplishments like Uncle Tom’s Cabin to human potential for greatness rather than God’s grace.

Notwithstanding her appeals to divine inspiration, Stowe had plenty of worldly sources from which to craft her tale. While living in Cincinnati, she had direct exposure to plantation life in the neighboring state of Kentucky. In 1834, Stowe had visited a nearby plantation, providing her a model for her portrait of slave life in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Escaped slaves, who found shelter in her Cincinnati and Brunswick homes, proved a rich resource too. In addition, Stowe solicited the assistance of prominent runaways like Frederick Douglass. “I am very desirous here to gain information from one who has been an actual labourer on one,” she wrote the black editor, “& it occurs to me that in the circle of your acquaintance there might be one who would be able to communicate to me some such information as I desire.” True to her desire to present as unbiased a picture as possible, she also gathered evidence from slave owners. “I have before me an able paper written by a southern planter in which the details & modus operandi are given from his point of sight,” she admitted to Douglass, “I am anxious to have some now from another stand point – I wish to be able to make a picture that shall be graphic & true to nature in its details.”48 In this way, Stowe hoped to both build on – and transcend – previous efforts to illustrate slavery’s horrors.

More so than most of her fellow New Romantics, Stowe had faith that the solution to the problem of slavery lay in converting the nation to the cause of the enslaved. In her 1845 short story, “Immediate Emancipation,” she implied that slaveholders need only to be exposed to the destructive potential of human bondage to be convinced of its immorality. Fifteen years later, on the cusp of the Civil War, Stowe wrote that slavery in New England “fell before the force of conscience and moral appeal.” And if moral suasion was, in historian Ronald Walters’s words, Stowe’s “weapon of choice,” then Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the most powerful round that she ever fired.49

Stowe’s novel worked from the arsenal of ideas assembled by a previous generation of romantic reformers. Garrisonians had pledged themselves to non-coercive tactics two decades earlier, while many evangelical abolitionists likewise embraced moral suasion despite their misgivings about nonresistance. Consider, for example, the popular 1839 compendium, American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, which Theodore Weld produced along with wife Angelina Grimké and her sister Sarah. By coupling runaway slave advertisements and other materials from southern newspapers with excerpts from fugitive slave narratives and first-hand testimonials about the institution, Weld and the Grimkés exposed the American public to the brutality of slavery. They let slaveholders and their former property speak for themselves. Despite the falling out between Weld and Lyman Beecher at Lane Seminary, the evangelical abolitionist’s moral-suasionist text appears to have had a strong influence on Stowe. Her 1853 A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in which she sought to defend her novel against accusations that it misrepresented slavery, included a good deal of material found in American Slavery as It Is. The romantic novelist even kept Weld’s compendium “in her work basket by day, and slept with it under her pillow at night, till its facts crystallized into Uncle Tom,” according to Angelina Grimké.50

Even so, Stowe was not entirely comfortable with the brand of moral suasion practiced by nonresistants such as Garrison or evangelicals like Weld. “With all credit to my good brother Theodore,” she wrote of Weld in 1853, “I must say that prudence is not his forte.... It seems to me that it is not necessary always to present a disagreeable subject in the most disagreeable way possible, and needlessly to shock prejudices which we must combat at any rate.” Stowe made similar comments about Garrison, whose confrontational stances and harsh invective put Weld to shame. The nation’s sins, the impassioned editor believed, merited “an avalanche of wrath, hurled from the Throne of God, to crush us into annihilation.” Although Stowe sympathized with Garrison’s positions and admired the Liberator’s “frankness, fearlessness – truthfulness & independence,” she worried about the zeal with which he critiqued all who disagreed with him, whether friend or foe. In an 1853 letter to Garrison, Stowe playfully called him “the celebrated Wolf of all wolves,” confessing that she “was exceedingly afraid of being devoured” by the radical abolitionist.51

In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe set out to recast moral suasion in a less confrontational fashion. Like many abolitionists, she was frustrated by the degree to which the South had closed itself off to any discussion of slavery. “The sensitiveness of the south on this subject is so great that they have enclosed themselves with a ‘cordon sanitaire’ to keep out all sentiments or opinions in favor of freedom,” she observed. Stowe wanted to write a book that, by presenting the institution of slavery in all its guises, would attract southern as well as northern readers. “I shall show the best side of the thing, and something faintly approaching the worst,” she wrote in early 1851.52 In A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1853, Stowe maintained that the novel was “a very inadequate representation of slavery” for the institution, “in some of its workings, is too dreadful for the purposes of art.” In this way, she broke with the pattern set by Garrisonians, who were infamous for their blanket denunciations of slavery and its proponents. At one point, Garrison called slaveholders “murderers of fathers, and murderers of mothers, and murderers of liberty, and traffickers in human flesh, and blasphemers against the Almighty.”53

Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s slave owners, in contrast, run the gamut from sympathetic yet feckless Augustine St. Clare to cruel and abusive Simon Legree. While Garrison alienated friend and foe alike, Stowe hoped that her balanced portrait would open doors to individuals who might otherwise feel no obligation to the enslaved. “Even earnest and tender-hearted Christian people seemed to feel it a duty to close their eyes, ears, and hearts to the harrowing details of slavery,” she wrote in the introduction that she added to an illustrated version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “These people cannot know what slavery is,” she reasoned.54

Stowe saw herself as an artist, not an agitator. “My vocation is simply that of painter,” she insisted, “There is no arguing with pictures, and everybody is impressed by them, whether they mean to be or not.”55 Certainly her deeply held belief in the inhumanity of slavery informed this position; slavery was so awful that even a tempered picture of it was enough to sway the public against the institution. So, too, did prevailing gender norms, which advised against women taking too strident a public stance. This is not to say, however, that Stowe lacked the acid tongue of a Garrison or a Douglass. Indeed, as biographer Joan Hedrick has argued, “a highly refined and pointed anger” rears its head from time to time in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After painstakingly highlighting the horrors of slave trading, for instance, the New Romantic laid blame not at the feet of slave traders, like Haley, but rather at those of leading Americans – particularly politicians – who have created a culture in which human trafficking thrives. “Who is most to blame?” Stowe asked. “The enlightened, cultivated, intelligent man, who supports the system of which the trader is the inevitable result, or the poor trader himself?” When the day of judgment comes, she warned, the elite may pay a greater price than the coarse and ignorant.56

On the whole, though, Stowe’s indictment of slavery tempered the immediatist critique of the South by spreading blame for the institution across the nation. White southern characters, like Emily Shelby and Augustine St. Clare, express doubts about slavery, while the true villain of the novel – Simon Legree – is the product of Stowe’s cherished New England. And even Legree, for all his malevolence, seems almost capable of salvation when exposed to the saintly Tom. “Legree,” wrote Stowe, “had had the slumbering moral elements in him roused by his encounters with Tom.”57

This lenient treatment drew criticism from some abolitionists. Although Higginson admired “the extraordinary book,” he initially thought Stowe sold slavery’s sinfulness short. “I charge upon Mrs. Stowe that she has softened down the actual evil – that her woman’s fear shrank from it,” he declared. In later years, however, Higginson put a positive spin on Stowe’s restraint. Despite his deep admiration for Garrison and his followers, the Transcendentalist had come to believe that the intolerance they had for slaveholders was excessive. Garrisonians, Higginson complained, rarely let the practical barriers that some slaveholders faced – such as state laws limiting manumission – get in the way of fierce invective. Stowe, in contrast, “was more discriminating.” Her depiction of St. Clare as a Byronic figure – tragically stuck between his personal misgivings about slavery and the reality that he could not do anything about it “because his slaves belonged really to his wife, who had no such feeling” – rang true to Higginson in the twilight of the nineteenth century.58

Still, Stowe faced daunting challenges trying to turn fiction toward effective social critique. For one, fiction that aimed at social reform had failed to garner much attention in the United States. Sentimental novels such as Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World had begun to sell well by the middle of the century, but antislavery fiction had, to this point, found readers only among the converted. What is more, many Americans harbored doubts about the implications of reading and writing imaginative literary works. Before Scott’s historical fiction gained popularity in the United States, nary a novel could be found in the Beecher household. As an adult, she remembered that in her youth “most serious-minded people regarded novel reading as an evil.” Although Stowe was convinced that fiction was “not merely a matter of amusement, but a high intellectual exercise,” she admitted as late as 1849 that the “doubtful hue of romance” that attends all imaginative literature was difficult to shake. Novel readers do not enjoy having “their sympathies enlisted and their feelings carried away by what, after all, may never have happened.”59

To make matters worse, although the great authors of her childhood had produced works of beauty and sophistication, too often they wrote without “any express moral design.” Stowe saved her sharpest barbs for Lord Byron. “The evil influence ... exerted by Byron on the minds of the young and sensitive, is not to be lightly estimated,” she wrote in the New-York Evangelist in 1842.60 Stowe expanded this critique of Byron in an essay she published the following year. Contrasting Romantics like Byron with “moral” writers like Dickens, she placed a premium on the social consciousness stimulated by imaginative literature. Writers such as Byron, she lamented, tend “to withdraw interest from the common sympathies, wants, and sufferings of every day human nature, and to concentrate them on high wrought and unnatural combinations in the ideal world.”

Dickens was different. He did not dismiss “the joys and sorrows of ordinary life as decidedly coarse and vulgar,” but rather used “the warmth of poetic coloring” to illuminate “the every day walks and ways of men.” Stowe believed that Dickens, unlike Byron or Scott, had performed a great service to “the cause of humanity” by depicting “the whole class of the oppressed, the neglected, and forgotten, the sinning and suffering, within the pale of sympathy and interest.” Indeed, Stowe made precisely this point in a letter she wrote to Dickens just as Uncle Tom’s Cabin was becoming an international sensation. “There is a moral bearing” in your work, confided Stowe, “that far outweighs the amusement of a passing hour. If I may hope to do only something like the same, for a class equally ignored and despised by the fastidious and refined of my country, I shall be happy.”61

The New Romantic, in fact, aimed to do more than Dickens because the British novelist had one glaring flaw in the eyes of his American counterpart: he did not provide positive representations of the Christian faith. Stowe, in contrast, would attend to both social and spiritual concerns. She imagined a literary concoction that combined Dickens’s gritty realism, Byron’s soaring prose, and her own deep piety – all in equal parts. She would serve this drink in the reassuring glass of antebellum sentimental literature. Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s domestic setting, its keepsake imagery, and Eva’s deathbed scene no doubt proved familiar to millions of consumers weaned on sentimental fiction.62

Stowe was richly rewarded for these efforts as people across the Western world rushed like never before to buy her book. Abolitionists toasted it, while white southerners and not a few northerners vilified it. Nonetheless, everyone was talking about Uncle Tom’s Cabin after its publication in early 1852. This singular achievement was not lost on her fellow New Romantics. “To have written at once the most powerful of contemporary fictions and the most efficient of anti-slavery tracts,” wrote Higginson, “is a double triumph in literature and philanthropy, to which this country has heretofore seen no parallel.” Stowe had repackaged moral suasion in a less confrontational and more approachable narrative, a fact that she herself highlighted. Responding to a letter from an admiring English lord, she counted among the book’s most important effects the conversion “to abolitionist views many whom” had been alienated by antislavery “bitterness.”63

Tom and Eva as Sentimental Martyrs

Frederick Douglass visited Stowe at her home in Andover, Massachusetts, in early 1853, not long after she and Calvin had relocated there. He came away thinking how easily the five-foot tall author – who had been an early North Star subscriber – could get lost in a crowd. “Sitting at the window of a milliner’s shop, no one would ever suspect her of being the splendid genius that she is! She would be passed and repassed, attracting no more attention than ordinary ladies,” observed the editor in his newspaper. But, he continued, once one engaged Stowe in conversation, she revealed herself to have “that deep insight into human character, that melting pathos, keen and quiet wit, powers of argumentation, exalted sense of justice, and enlightened and comprehensive philosophy, so eminently exemplified in the master book of the nineteenth century.”64

His former partner Delany begged to differ. In a series of letters that he sent Douglass not long after the editor had visited Stowe in Andover, this New Romantic laid his misgivings bare. White abolitionists like Stowe, insisted Delany, knew nothing about blacks and must not be allowed to take the lead in their liberation. He also objected to Stowe’s seeming advocacy of colonization toward the end of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Finally, the black abolitionist took issue with Stowe’s positive portrayal of Tom as a pacifist martyr.65

Delany was not alone in this final critique. Indeed, the passivity of Stowe’s titular character has been denounced time and again by critics of the novel in the century and a half since it was published. To many readers – white and black, radical and conservative, old and young – the figure of Uncle Tom epitomizes meek submission. Although this characterization’s durability has something to do with stage adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which often depicted Tom as little more than a passive, happy-go-lucky figure, the fact remains that even careful readers of the novel have interpreted Stowe’s titular hero as an “Uncle Tom.”66

This representation, however, simultaneously elides Tom’s moral resolution and the purpose for which Stowe sought to use it in her novel. Instead of centering her story on a martial hero like Madison Washington, Stowe focused, first and foremost, on the experiences of a different type of romantic hero: the sentimental martyr. Tom’s myriad personal sacrifices, especially his tragic demise (as well as that of his symbolic soul mate Eva), rather than the more conventionally heroic escapades of runaways George and Eliza, provide the emotional foundation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In making Tom a sentimental martyr, in other words, Stowe did not craft a timid character. Instead, from start to finish, she paints Tom using bold colors. “The hero of our story,” she writes, “was a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man.” Though gentle, pious, and unwilling to escape his bondage, he is strong, courageous, and principled. While barely literate, Tom has an admirable work ethic and sharp business acumen, qualities recognized by all of his masters. Moreover, while Tom ultimately accepts death at the hands of his master and his henchmen, all of his decisions are guided by his conscience rather than his owners’ orders. In the novel’s early stages, he agrees to be sold down the river in order to save the rest of the Shelby slaves from the same fate. Likewise, he refuses to whip Lucy, despite Legree’s threats, explaining, “I’m willin’ to work, night and day, and work while there’s life and breath in me; but this yer thing I can’t feel it right to do’ – and Mas’r, I never shall do it, never!”67

Thus, Tom follows his own moral compass, a fact that angers Legree enough to kill him. And when Tom refuses to beg his master’s forgiveness and take up the whip against his fellow slaves, Stowe suggests that his forbearance trumps the brutal master’s physical might: “Tom stood perfectly submissive; and yet, Legree could not hide from himself that his power over his bond thrall was somehow gone.” Tom’s refusal to reveal Cassy and Emmeline’s hideout ultimately provokes Legree to beat him savagely and then to turn him over to Sambo and Quimbo to finish the job. Even in death, Tom acts of his own volition, if not in his own best interests. Feeling “strong in God to meet death,” Tom admits to Legree that he knows Cassy and Emmeline’s whereabouts, but he refuses to betray them. “I can’t tell anything,” insists the martyr, “I can die.” Although rooted in his deep Christian faith, this self-sacrifice was not motivated simply by his desire for salvation in heaven but also his concern for fellow bondspeople on earth. “Tom in various ways manifested a tenderness of feeling, a commiseration for his fellow-sufferers,” writes Stowe. Epitomizing the religion of the heart that the New Romantic had come to embrace a decade earlier, Tom was, to Stowe, a hero in the mold of Jesus Christ. Or, to put the matter in another way, he was anything but an “Uncle Tom.”68

Some scholars argue that it would be more accurate, if oddly put, to call Tom “the supreme heroine of the book.” After all, Stowe’s central character embodied the qualities that nineteenth-century Americans associated with true womanhood – submission, piety, and self-sacrifice – qualities that Stowe put at the core of the Christocentric theology she developed in the 1840s. The novelist, in fact, viewed Jesus Christ as the natural offspring of God and Mary, whose miraculous conception “was the union of the divine nature with the nature of a pure woman,” concluding that “there was in Jesus more of the pure feminine element than in any other man.”69

If no living man could rival Jesus in his feminine characteristics, she created a fictional character who seemed equal to the task. Like any true woman, Uncle Tom is dutiful, pious, and altruistic. He puts the interests of family and hearth and home ahead of all else. After accepting his fate of being sold down the river rather than jeopardizing his family, Tom sobs uncontrollably over his sleeping children. He then urges young George Shelby – his owner’s son – to respect his parents in what Stowe describes as “a voice as tender as a woman’s.”70 Later, as Eva lies dying, Tom becomes a surrogate mother of sorts. As her own mother Marie spends Eva’s final days absorbed in her own suffering – a model of what a true woman would not do – Tom dutifully dotes on the young girl. In the meantime, Eva plays the role of good mother herself, reaching out and inspiring the abused and motherless Topsy.

Exemplars of feminine and maternal values, Uncle Tom and Evangeline St. Clare were Christ-like figures for Stowe. After describing Legree’s brutal beating of Tom, she writes, “But, of old, there was on One who suffering changed an instrument of torture, degradation and shame, into a symbol of glory, honor, and immortal life; and, where His spirit is, neither degrading stripes, nor blood, nor insults, can make the Christian’s last struggle less than glorious.” Tom, like Christ, sacrifices his life not only to save Cassy and Emmeline but, more generally, as a moral lesson – and a path to salvation – for others. The same can be said of Eva. “She’s no more than Christ-like,” admits Miss Ophelia once she sees Eva’s effect on Topsy. “I wish I were like her. She might teach me a lesson.”71

Tom’s martyrdom, of course, follows the pattern that Stowe had set earlier in the book with Eva, who seems to be physically and emotionally consumed by exposure to slavery. In a conversation she has with Tom not long before her death, Eva foreshadows her fate as well as its purpose. “I can understand why Jesus wanted to die for us,” she said to Tom, acknowledging that she had “felt so, too.” When Tom expresses confusion, Eva explains that watching slaves who have been separated from their mother and fathers, wives and husbands, got her thinking about what she could do. “I would be glad to die, if my dying could stop all this misery,” she concluded. “I would die for them, Tom, if I could.”72

Stowe’s saintly portrait of Tom and Eva amounts to a creative combination of her Christocentric theology with three other romantic currents: romantic racialism, the idealization of childhood, and sentimentalism. Like so many of her contemporaries, she embraced the romantic racialist assumption that African Americans were inherently meek, pious, and emotional. Stowe’s racial imagination was most likely shaped by the work of Alexander Kinmont, a Swedenborgian educator who offered a series of influential ethnographical lectures in Cincinnati in 1837 and 1838. Born in Scotland, Kinmont had converted to Swedenborgianism – a Christian sect that followed the teachings of eighteenth-century Swedish mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg – after moving to the United States in the 1820s. He settled in Cincinnati, where he founded Kinmont’s Boys Academy, a school that offered students a classical and scientific education as well as a thorough grounding in Swedenborgianism. Although Swedenborgian converts were few and far between, his “doctrine of correspondence,” which posited a direct connection between the objects of the physical world and truths of the spiritual world, influenced Transcendentalists like Emerson and Higginson.73

Kinmont, in turn, popularized Swedenborg’s more obscure racial theories. In several minor works, the Swedish visionary had insisted that Africans have the innate ability to communicate with God in a more direct, unmediated fashion than other races. Hence, he concluded, they “are more receptive of the Heavenly Doctrines than most others on this earth, because they readily accept the Doctrine.” Kinmont expanded upon this idea in his Twelve Lectures on the Natural History of Man, which depicted Africans as inherently spiritual, feminine, and childlike. He insisted that Caucasians were, in contrast, naturally rational, masculine, and aggressive, so much so that “all the sweeter graces of the Christian religion appear almost too tropical, and tender plants, to grow in the soil of the Caucasian mind.”74

No conclusive evidence has been found confirming that Stowe, in fact, heard Kinmont deliver these lectures. We do know, however, that she too was an educator, lived in Cincinnati in the years in which he gave his lectures, and followed cultural happenings closely. Stowe even took note of Kinmont’s death in late 1838. We can imagine that the well-read author was at least exposed to Kinmont’s ideas after his lectures were published to much fanfare in Cincinnati the following year.75

In any case, one thing is certain: the romantic racialist vision that emerged in the budding abolitionist’s public and private writing in the early 1850s aligned precisely with the theories Kinmont had laid out a decade earlier in Cincinnati. Stowe, too, judged people of African descent as inferior to whites in terms of their intellectual capacity and fighting spirit, but superior in terms of religious and emotional capacities. As she wrote of African Americans in 1851: “I have seen the strength of their instinctive and domestic attachments in which as a race they excel the anglo saxon.”76 In Uncle Tom’s Cabin she repeatedly associated simplicity, religiosity, and meekness with African ancestry. Tom, wrote Stowe, had “the soft, impressible nature of his kindly race, ever yearning toward the simple and child-like.” Lacking in the “daring and enterprising” qualities that both Stowe and Kinmont associated with whites, African Americans, she insisted, were domestic, affectionate, and pious by nature. She concluded in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin that “the divine graces of love and faith, when in-breathed by the Holy Spirit, find in their natural temperament a more congenial atmosphere” among blacks “than any other races.” Uncle Tom, of course, epitomized this innate black spirituality.77

If, in Stowe’s mind, Tom derived his Christ-like qualities from his black ancestry, then Eva’s divine nature was similarly conditioned by her youth. Like many romantics across the Western world, Stowe thought children were oracles of divine wisdom who could teach as much as they could learn. Transcendentalist Bronson Alcott called the child “a Type of Divinity,” who revealed the “nature” of man, “despoiled of none of its glory.” Emerson opined that “infancy is the perpetual Messiah, which comes into the arms of fallen men, and pleads with them to return to paradise” in his widely read essay, “Nature.” Closer to nature, children seemed closer to God. Stowe likewise believed that children had much to “teach us,” especially insofar as morality and spirituality were concerned. “Wouldst thou know, O parent, what is that faith which unlocks heaven?” she asked in an 1846 essay. “Go not to wrangling polemics, or creeds and forms of theology, but draw to thy bosom thy little one, and read in that clear, trusting eye, the lesson of eternal life.”78

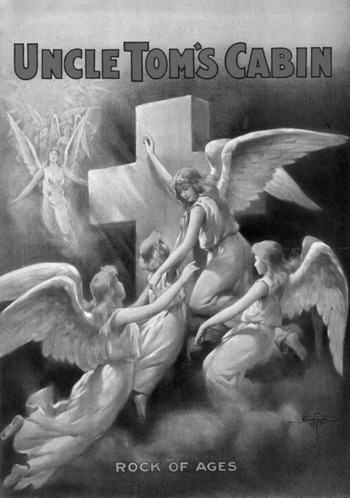

No character in American literature better exemplifies the divine interpretation of childhood than Little Eva. Stowe renders her as a romantic, otherworldly figure. When Tom first catches a glimpse of her aboard a Mississippi steamboat, Eva “seemed something almost divine.” Blonde-haired, blue-eyed, and “always dressed in white,” she has “an undulating and aërial grace, such as one might dream of for some mythic and allegorical being.” In her purity, selflessness, and deep piety, Eva reflected Stowe’s faith that children were the spiritual foundation of the nation (Figure 3.2).79

Stowe’s saintly characterization of Eva, especially her overwrought death scene, has provoked almost as much critical opprobrium as the image of Uncle Tom. “Little Eva gains her force not through what she does, not even through what she is, but through what she does and is to us, the readers,” Ann Douglas argued in the most forceful critique of the scene. Eva is little more than a “decorative” character, she wrote, whose “sainthood is there to precipitate our nostalgia and our narcissism.” Her death typifies the larger problem that Douglas identified in works of Victorian sentimentalism like Uncle Tom’s Cabin: the betrayal of the seriousness and artistry of elite culture in favor of “sentimental peddling of Christian belief for its nostalgic value.” Contrasting sentimental literature with the work of such European Romantics as Goethe, Keats, Shelley, and Coleridge, Douglas insisted that the former lacks the latter’s “political and historical sense,” its “spirit of critical protest.” Instead, sentimentalism encourages “self-absorption, a commercialization of the inner life.” Yet Douglas’s test for whether a work of literature is romantic or sentimental has more to do with aesthetics than its social or political import. Romanticism, she held, “no matter how strained or foreign to modern ears, has not – to use Hemingway’s phrase – ‘gone bad.’” Sentimental literature, in contrast, sounds sappy and dated. The eminent black novelist James Baldwin agreed. As he wrote in a scathing 1949 essay, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, having, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality, much in common with Little Women.” Baldwin called “sentimentality ... the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion” – “the mark of dishonesty.”80

While Douglas’s and Baldwin’s interpretations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s aesthetic shortcomings are on target, they miss the mark in other ways. First of all, as scholars like Jane Tompkins have ably demonstrated, sentimentalists like Stowe did not retreat “from the world into self-absorption and idle reverie.” Quite the contrary, by positing the transformation of America into a more just republic at the hands of “Christian women,” they put the seemingly conservative values of sentimentalism and domesticity to work in the service of radical social reform. Secondly, sentimentalism was far from a dishonest or intellectually bankrupt body of ideas. Instead, it had deep philosophical roots, some of which could be found in the romantic soil that Douglas valued so highly.81

Sentimental literature reached its apogee in the nineteenth century, but arguments for the centrality of emotion and feeling date back to the early modern period. Responding to the perceived ethical shortcomings of Lockean empiricism, Scottish Common Sense philosophers like Francis Hutcheson and Adam Smith posited an internal moral sense by which to guide all individual action. In his influential 1759 The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith stressed the use of imagination in the process of identification with another. “By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation,” he wrote, “we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him.”82

Stowe was likely exposed to Common Sense theories by such writers as Hugh Blair and Archibald Alison, whom she read as a young girl. Her sister Catharine, who developed an education theory based on awakening “affection in the human mind” at the Hartford Seminary, reinforced this early interest in Common Sense philosophy. Drawing directly on Smith’s theories, Catharine wrote that instructors could help students develop their faculty of “Sympathy” – “the power the mind possesses of experiencing such emotions as ... exist in another mind.”83

Stowe also found intellectual support for sentimentalism in the contemporary arguments of romantics in the United States and Europe. Since the 1840s, Stowe and her husband had been reading the work of Schleiermacher, who maintained that “religion’s essence is neither thinking nor acting, but intuition and feeling.” Her fellow New Romantics likewise identified sentiment as the wellspring of humanity. “A man without large power of feeling is not good for much as a man,” wrote Parker. “He may be a good mathematician, a very respectable lawyer, or a doctor of divinity, but he is not capable of the high and beautiful and holy things of manhood.”84Douglass believed that mankind’s “affinities” were so powerful that even the institution of slavery could not sunder them. On the anniversary celebration of West Indian emancipation in 1848, he confidently announced that “the magic power of human sympathy is rapidly healing national divisions, and bringing mankind into the harmonious bonds of a common brotherhood.” Fourteen years later, while serving in South Carolina as a commander of a regiment of ex-slaves, Higginson also invoked the bonds of sympathy that unite all people. In a journal passage in which he explored the elements that set his African American soldiers apart from their white counterparts, he wrote, “As for sugar, no white man can drink coffee after they have sweetened it – perhaps I could, I never tried it – & perhaps this sympathy of sweetness is the real bond between us.” Even the simple act of tasting his soldiers’ coffee, Higginson implied in Smithian fashion, had the potential to foster sympathetic identification with another.85

As Stowe formulated her unique brand of reform fiction, she drew on both romantic and Common Sense theories of sentimentalism. Like Smith, Parker, Schleiermacher, and countless others, she highlighted the extraordinary power of “the faculty of the imagination,” which, she insisted in 1849, exists “burning and God-given, in many a youthful soul.”86 As she would later illustrate with her evocative “ladder to heaven” metaphor, Stowe believed the foundation of society and individual salvation lay “in human affections, tender instincts, symbolic feelings, [and] sacraments of love,” which transcended all races and cultures. Indeed, at one point in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe posited sentimental identification as nothing less than the sine qua non of the human condition. The moment in question takes place on the northern Quaker settlement to which Eliza and her son flee. When Eliza’s host Rachel Halliday learns that George has, unbeknownst to Eliza, also found his way to the settlement, she asks her friend Ruth whether she should tell the runaway immediately. “Now! to be sure, – this very minute,” replies Ruth. “Why, now, suppose ‘t was my John, how should I feel?” After Rachel’s husband Simeon applauds her neighborly love, Ruth asks, “Isn’t it what we are made for?”87

The same could be said of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which Stowe deliberately crafted to help her audience feel the suffering of the enslaved. As she wrote in her first preface, “The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away with the good effects of all that can be attempted for them, by their best friends, under it.”88 Unlike most authors, Stowe did not limit such direct appeals to her readership to the preface. Instead, throughout the novel she repeatedly disrupted the flow of the narrative with authorial interventions that challenge her readers to put themselves in the shoes of her suffering characters. Describing the scene in which Tom selflessly submits to Mr. Shelby’s decision to sell him to Haley rather than see the whole plantation broken up, Stowe explicitly asks her readers to connect it to similar pain that they have suffered: “Sobs, heavy, hoarse and loud, shook the chair, and great tears fell through his fingers on the floor; just such tears, sir, as you dropped into the coffin where lay your first-born son; such tears, woman, as you shed when you heard the cries of your dying babe.”89

Having lost her son Charley a few years before writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe urges her readers to identify with Tom and his family’s plight by drawing on their own emotional reserves. Later, she concludes a passage in which Eliza debates whether she has the strength necessary to run away with Harry from being sold down the river with another direct question to her audience. “If it were your Harry, mother, or your Willie, that were going to be torn from you by a brutal trader, tomorrow morning ... how fast could you walk?” she asks. “How many miles could you make in those few brief hours, with the darling at your bosom, – the little sleepy head on your shoulder, – the small, soft arms trustingly holding on to your neck?” Finally, while Stowe wrestles directly with the question of what individuals can do to solve the problem of slavery toward the end of the novel, she makes her classic appeal that “there is one thing that every individual can do, – they can see to it they feel right. An atmosphere of sympathetic influence encircles every human being; and the man or woman who feels strongly, healthily and justly, on the great interests of humanity, is a constant benefactor to the human race.” Feeling right and identifying with the tragic victims of slavery, she implies, can help individuals build a culture where the Toms of the world do not have to die.90

At other points, Stowe encourages sympathetic identification with others with more subtlety. Eva’s death, for example, is largely conveyed through the experiences of her family members and their bondspeople. While Eva stoically faces her imminent demise, handing each of the household “servants” a lock of her curls, they burst out with “groans, sobs, and lamentations.” Later, Stowe lingers on the shared anguish of Augustine St. Clare and Tom as Eva is at death’s door. “O, Tom, my boy, it is killing me!” cries St. Clare as a crying Tom squeezes “his master’s hand between his own.” Meanwhile, Eva smiles brightly, sighing as she passes away, “O! love, – joy, – peace!” Stowe employs a similar dynamic in Tom’s death scene, which is represented first through the eyes of Sambo and Quimbo and later through those of George Shelby, the son of his former master. Amid savagely beating Tom, the two drivers are overcome with the wickedness of their actions. Shortly thereafter, Shelby arrives, hoping to buy Tom and return him to his old Kentucky home. Stowe affords the reader a quick glimpse into the heart of Tom, who is at once overjoyed by the news that he has not been forgotten by the Shelby plantation, while nonetheless looking forward – even more than Eva – to his imminent demise. Yet again Stowe is concerned with the emotional impact of his death on those who surround him, explicating how his death converts Sambo and Quimbo to Christianity while pushing George to swear before God that he “will do what one man can to drive out this curse of slavery from my land!” 91

Viewed through the lens of sentimental identification, then, these death scenes compel Stowe’s readers to put themselves not so much in the shoes of her martyrs, but rather those of the mere mortals who surround them. By focusing on the emotional toil of Tom and Eva’s deaths on those who witnessed them as well as their impact on friends, family, and others, Stowe offered a primer on the tragedy of the institution of slavery. She did not encourage her audience to strive to live up to Eva and Tom’s impossibly high example so much as to understand the acute suffering that it inevitably entailed. This tragic thread extended even to the conversions that resulted from their deaths. On the surface, Eva’s death scene seems to be a turning point in the novel, after which those close to her would never be the same. But while Eva helps convert Topsy to Christianity in her final days, she fails utterly to effect larger changes, not least of which is the goal for which she died: the liberation of the St. Clare slaves. Even the promise to free Uncle Tom, which Eva elicits from her father at her deathbed, comes up empty as Augustine is killed in a fight before he can finalize the emancipation.

Tom’s martyrdom, too, achieves at best limited practical results regarding slavery. George pledges himself to the antislavery cause and knocks brutal Legree to the ground. Yet when the Legree slaves who bury Tom ask the young master to save them from the “hard times” on the Red River plantation by buying them, he replies, “I can’t! – I can’t! ... it’s impossible!” George does play the role of liberator on his own plantation in Kentucky. But here, too, we are left with a sense of ambivalence about what Stowe’s sentimental martyr can truly achieve. After being liberated, the Shelby slaves stay on as wage laborers, declaring, “We don’t want to be no freer than we are. We’s allers had all we wanted. We don’t want to leave de ole place, and Mas’r and Missis, and de rest!” Aside from helping Cassy and Emmeline escape, the only concrete blow against slavery that Tom manages to strike leads to the creation of a free labor version of the plantation ideal trumpeted by proslavery apologists like George Fitzhugh. In the end, it is difficult to escape the fact that even Christ-like martyrs are no match for the power of institutionalized slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.92

George and Eliza as Resistant Rebels

The tragic role played by Tom in Stowe’s sentimental drama raises the question of whether, indeed, she meant him to serve as a heroic model. Garrison, for one, had no doubt that she did. “His character is sketched with great power and rare religious perception,” he wrote. “It triumphantly exemplifies the nature, tendency and results of CHRISTIAN NON-RESISTANCE.” But on this issue the abolitionist editor also challenged Stowe, wondering whether she believed “in the duty of non-resistance for the white man, under all possible outrage and peril, as well as for the black man.” Highlighting the gap between the suffering submission of black Uncle Tom and the heroic journey and fighting spirit of mixed-race George Harris, he asked, “Is there one law of submission and non-resistance for the black man, and another law of rebellion and conflict for the white man?”93

Garrison’s reading of Uncle Tom’s Cabin underscores a critical point: Along with Tom the martyr, Stowe proffered an altogether different tale of heroism. The plotline of runaway slave George Harris, who personified the martial valor that so appealed to her fellow New Romantics, further reveals Stowe’s ambivalence about the appropriate response to slavery, at least for those with Anglo-Saxon ancestry.