In this chapter, I consider the chief alternative to the normative account of the preceding three chapters. Most philosophers and lawyers have thought that the rule of law is closely associated with an ideal of liberty. I have some skepticism about this claim (“the liberty thesis”), and aim with this chapter to subject the multiplicity of arguments for it to closer examination. To do so, this chapter introduces the transition between the purely normative and conceptual analysis of the rule of law and a strategic analysis. The full account of this book integrates the two analytic strategies, arguing that both give us reason to expect a strong association between the rule of law and equality. Here, this integration is begun.

This chapter begins (section I) by arguing – using an elementary game theoretic model – that the rule of law actually may facilitate the control by officials over nonofficials, and thus may impair rather than advance individual liberty. This strategic argument foreshadows the later chapters of this book (especially Chapter 6), which center on the claim that the rule of law will be maintainable only in an environment in which coordinated nonofficial action holds officials to account. This tool for holding officials to the limits of the law, I argue, also can be a tool to allow officials to credibly commit to costly punishment, and hence to reliably get their orders carried out.

This chapter then considers several arguments that have been offered in the philosophical and legal literature for the liberty thesis. Although, as noted, I approach them with substantial skepticism, the goal is not to refute them – all have their merits – but to find their boundaries and to consider the extent to which they apply to real-world states. In examining these arguments, the focus remains largely on the strategic context – that is, on the incentives that the rule of law and its institutional supports create, and the extent to which those incentives either facilitate or inhibit interferences with the choices of nonofficials.

The chapter closes by returning to the equality thesis of the previous chapters, and to the expressive approach to interpreting value claims that those chapters emphasize. It turns out, I argue, that we can helpfully interpret compelling arguments in the domain of liberty as egalitarian appeals to the ideal of equal respect for people as autonomous decision makers.

I The rule of law as a technology of constraint

To begin, let us consider a very conventional problem in the strategic analysis of questions in political science: the credible threat. This is a highly general problem, relating to the fact that using force is typically costly. If I want to order you around on pain of violence, and you disobey my orders, I have to decide whether to expend the cost to punish you. In many strategic circumstances (which may vary depending, for example, on whether we’re embedded in a system of repeated interactions with sufficiently low discounting, whether my punishing you may send useful signals to other players, etc.), it becomes hard to see my punishing you as rational. In the simplest case, your disobedience has already occurred and is irrevocable: punishing you is simply a costly act of spite that cannot change your behavior. As a result, looking down the game tree, if you think I’m rational, you need not obey my initial command, for you know it is not rational for me to punish you for disobedience.

As I said, this is a very general problem in political science, which is, after all, the discipline about understanding when people can successfully deploy force against one another to achieve their ends. It is particularly prominent in the international context, where political scientists have long studied the strategy of deterrence.1 It is also a very old problem: to my knowledge, the first person to see it was Niccolò Machiavelli, who counseled rulers to be careful about punishing the powerful (i.e., those as to whom punishment is particularly costly).2 Let us consider it in the law enforcement context.

Suppose an absolute ruler (Louis), completely unconstrained by the rule of law, wishes to forbid some behavior. He announces that he will interfere with citizens’ choices to do so by violently punishing those choices. However, Louis knows that punishment is costly: even an absolute ruler must pay his soldiers in order to keep his job, and he has only a limited budget for doing so; that is, to punish someone, violent resources must be diverted from other uses at an opportunity cost. Moreover, the fact of punishment itself can be damaging: to punish someone might invite distrust and potential retaliation, or simply may undermine Louis’s propaganda campaign, which has maintained that nobody would dare think of disobeying him.

So Louis issues the following decree: “No one may put a pink flamingo on his or her lawn, on pain of imprisonment.” In order to figure out whether it will be obeyed, we must go through some basic game theory.

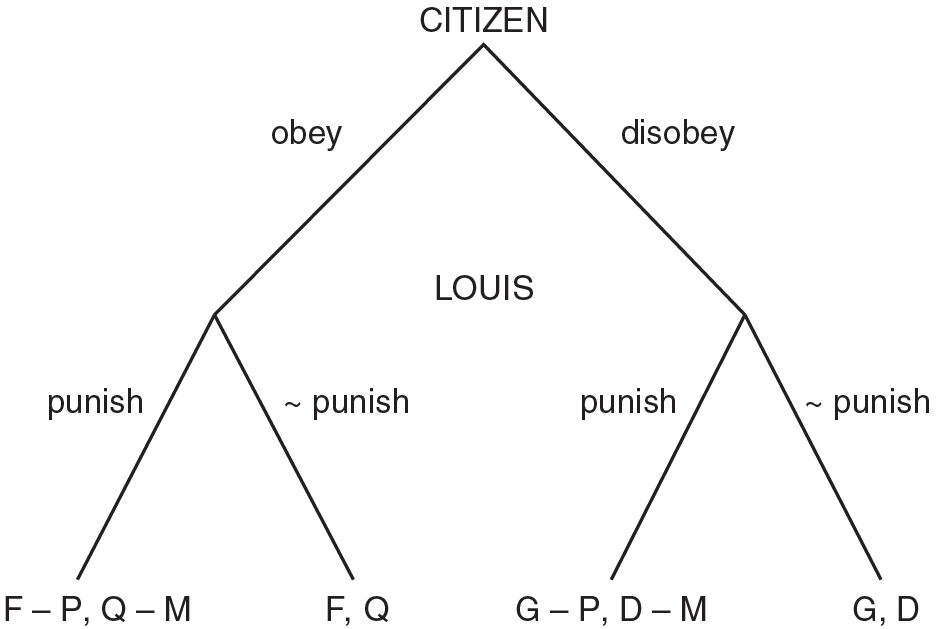

Start with a straightforward two-stage punishment game, in which a citizen first chooses either to obey or to disobey the ruler’s command, and the ruler then chooses to punish or not. Citizen’s payoff for obeying is F, for disobeying G. Ruler’s payoff for obedience is Q, for disobedience D. G > F, and Q > D. Ruler can punish at cost M, which inflicts cost P on the citizen (see Figure 4A).

Figure 4A: A credible commitment game

Trivially, where M > 0, the only pure strategy subgame perfect equilibrium of the one-round version of this game has the citizen disobeying and the ruler refraining from punishment.3

Let us consider a finitely repeated version of the same game with N rounds. By backward induction, where M > 0 the only pure strategy pair that is in subgame perfect equilibrium is [always disobey, never punish]. In round N, regardless of the previous play, we’re back in the one-round game such that citizen disobeys and ruler declines to punish. Given that, neither can make credible threats about one’s behavior in round N to influence the choice about round N – 1, so in round N – 1, again citizen disobeys and ruler declines to punish, and so on. In this simple model, it looks like we may festoon our lawns with pink flamingos with impunity.

There are many ways to solve this model and give Louis the power to punish us. If, for example, we are in an indefinitely repeated game with sufficiently low discounting (if we might obey or disobey Louis again and again and again), then there are folk theorem equilibriums according to which we obey. (However, there are also folk theorem equilibriums according to which we disobey. Equilibrium selection in these contexts is a thorny problem.) There are also reputation-based mechanisms for solving these problems; it may be worthwhile for Louis to punish me in order to communicate his willingness to punish you (signal that punishment is not all that costly to him).4 The political science literature is rich with such models.

However, if Louis is particularly clever, he may recruit us to punish ourselves. Here’s how. Suppose he can off-load the decision whether or not to inflict punishment for his decrees to an independent punisher, like a bureaucracy, judge, mass jury, or even a computer program. Call the independent punisher “Richelieu.” If Richelieu does not personally incur the cost of punishment, then she is not inhibited by that cost from imposing it; if she is embedded in an institutional context in which there is a positive incentive to actually impose the punishment (such as one in which she is trained and rewarded for following the decrees or laws Louis enacts), then we would expect it to actually occur. Well, in truth, we would expect it never to actually occur, because disobedience, and thus punishment, would be off the equilibrium path: now that Louis can credibly threaten punishment, nobody will ever disobey, and Richelieu need never carry it out.5

Now Louis has a new problem: how can Richelieu be independent? After all, Louis still pays for Richelieu’s punishments. Accordingly, even if he decrees that Richelieu’s decisions are immune from his control, that decree itself is not credible. The moment Richelieu orders a costly punishment, Louis ought to countermand that order.

Suppose, however, that Louis can make a deal with the masses (or the nobility, or anyone else with the power to act in concert against him). Here are the terms of the bargain: “I will write down a list of my rules, announce them in advance, and give them to Richelieu to enforce. Richelieu will be trained to really care about these rules, and paid to obey them. You backstop Richelieu’s power, and make sure that I don’t interfere with her judgments. In exchange, I won’t try to punish you for anything that isn’t on the list.” Political scientists know this technique as creating “audience costs”: finding someone who will sanction Louis for not doing the thing he wants to commit to do.6 As I will argue in Chapter 6, that is a very good deal for the people: if they have a common-knowledge set of rules governing the use of Louis’s power against them, and a consensus method of resolving disputes about the application of those rules (i.e., Richelieu), then they can develop the capacity to collectively hold Louis to those rules. That chapter will argue that the rule of law is actually built and sustained by establishing means by which people know the conditions under which their fellows will act against their government.7

The catch is that by doing so, they empower Richelieu, and if the law motivates Richelieu, and if Louis writes the law, then the very means by which the people can hold Louis to only using violence against them pursuant to the law is also the means by which Louis can off-load the cost of punishment and hence make the commands he writes into the law enforceable.8

Used this way, the weak version of the rule of law is partly a tool of freedom, partly a tool of unfreedom. It allows rulers or officials – at least in nondemocratic societies, or imperfectly democratic societies – to inflict a specified list of unfreedoms on the people, in exchange for the guarantee that those are the only unfreedoms that will be so inflicted (or at least that there will be some kind of public announcement before adding to the list, and the list won’t be retroactively supplemented).9 The bargain is to recruit the people (or those with power) to help create an alternative source of power that can bind all; doing so both holds rulers to the law they have set out and helps rulers enforce those laws over the people.

This separation between enforcement power and enforcement costs is a general-purpose technology of law enforcement, which works both for and against officials. That technology explains regimes like that of Singapore, a wealthy, capitalist, efficient state with high levels of property rights protection, low levels of corruption, effective and fair police and courts, and an incredibly restrictive and harsh criminal law featuring extensive surveillance, bans on chewing gum, floggings, and bold red letters on the immigration forms one must fill out to enter the country reminding visitors that it levies the death penalty for drug trafficking.10 Singapore has aimed its extraordinarily effective technologies of law enforcement at citizens and officials alike.11

Of course, the bargain to create audience costs will not work unless the people inflicting those audience costs get something out of the deal. Depending on the configuration of power relationships in the populace, this might actually mean substantive guarantees of individual liberty, or it might mean economic development (as in Singapore), or even just rents attached to a powerful aristocracy. These issues will be taken up further in Chapter 8. For now, suffice it to say that the rule of law appears to be a general-purpose technology of constraint that may allow officials to constrain people, as well as allow people to constrain officials; it is not obvious that it facilitates individual liberty.

With that initial skepticism established, let us now move to the affirmative case for the liberty thesis.

II Some arguments for the liberty thesis

In this section, I run through some arguments for the liberty thesis and their associated conceptions of liberty. We may begin with mainline liberal arguments for the claim that the rule of law facilitates what is often known as “negative liberty,” or the ability of people to be free from interferences in their choices (including increases in the costs imposed on their choices by others).

A The incentives argument

From the liberal standpoint, I consider two major lines of argument. The first, which appears in Hayek as well as in Federalist No. 57, I call the “incentives argument”:12 the rule of law requires officials to apply the laws to their own behavior; this encourages them to minimize their interference with subjects’ choices in order to avoid interfering with their own.13

This argument, though stated in abstract form, might lead to actual claims about real-world societies. Consider a religious state in which restrictive regulations are enforced against ordinary citizens, but not against the ruling elite. Reputedly, for example, in Saudi Arabia, sharia is enforced against ordinary citizens, but the elite who control the state’s institutions violate it with impunity.14 Were elites constrained to obey the laws they apply to the masses, it would at least become more likely that they would adopt a less restrictive interpretation of Islamic law in order to preserve as many of their own pleasures as possible.

The incentives argument is plausible with respect to states with a substantial degree of similarity between officials’ preferences and ordinary subjects’, particularly with respect to the desirable domain of noninterference. This suggests that it will not be plausible in two types of societies. First, in societies governed by officials who subscribe to strong comprehensive doctrines (e.g., theocracies), officials may not particularly care about restrictions on their own liberty.15 Second, in highly diverse societies, the things that officials count as restrictions on their liberty may not be the same as those that ordinary subjects (or cultural minorities) count as restrictions on their liberty.16

A potentially stronger variation on the incentives argument appears in a concurring opinion by US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson. There, he argues that a state that is bound to apply the same law to political majorities as to political minorities (that is, a state with general law, on a formal conception) will protect the people from “arbitrary and unreasonable government,” because it will subject officials to “political retribution” from the affected majority if the laws are oppressive.17

However, the same point about pluralism applies to Jackson’s version of the argument. A wide variety of illiberal laws might be enacted that majorities are happy to suffer, but that are experienced as oppressive by cultural or religious minorities, or just those with idiosyncratic preferences.

That being said, the incentives argument may still give us good reason to suppose that the rule of law facilitates individual freedom, for even fanatical officials or bigoted majorities may prefer some level of individual freedom for themselves. There might be some laws that not even Savonarola would be willing to apply to himself – perhaps he’s willing to apply the sumptuary laws to himself, but he really likes eating meat on Friday, so in a rule of law society he finds himself forced to restrain his regulatory zeal to at least that minimal extent. The incentives argument gives us some reason to believe that the rule of law will facilitate individual liberty, but it is unclear how far that reason goes.

B The chilling effects argument

The second argument comes from Rawls, who argues that where citizens’ liberties are uncertain, they will be deterred from actually exercising them in virtue of the risk that they might be punished for something that they had thought was within their domain of choice.18 This closely resembles an argument often deployed in US free speech law, in which vague restrictions on speech are said to cause a “chilling effect,” leading to self-censorship.

The force of the chilling effects argument is not limited to vague law. Potentially, any failures of regularity and publicity risk a chilling effect. If official power is inadequately controlled by legal rules, or citizens have no way of knowing what those rules are or participating in their enforcement, then they may have reason to fear that official power will be used against them unexpectedly, and this may, in turn, give them reason to keep their heads down and restrict their activities to avoid drawing the attention of the powerful.

Let us note, however, that all law creates some chilling effect regardless of whether the rule of law is satisfied. Legal theorists have long recognized that there is room for disagreement about the application of laws in marginal cases (in what Hart called the “penumbra” of a legal rule). This indeterminacy creates a chilling risk: a citizen whose behavior is on those margins may have good reason to avoid choices that she believes to be lawful out of the fear that officials may disagree and punish her – if the law is “No vehicles are allowed in the park,” a sensibly cautious citizen might refrain from skateboarding in the park even if she thinks that skateboards don’t count as vehicles.

For the chilling effects argument to count as a defense of the liberty thesis, citizens’ choices must be chilled to a greater extent in a state that does not comport with the rule of law (and hence just enforces officials’ unvarnished preferences, if those officials can find a way to credibly commit to punishing those who violate them) than in a state that does. Alternatively, we may create a version of the chilling effects argument according to which subjects don’t constrain their own choices, but they sometimes get punished for acts they thought would go unpunished – experiencing interferences in their liberty in virtue of that cost imposed on their choices, even if they make their most preferred choices anyway. Either version of the argument, however, depends on the proposition that officials’ preferences are unknown or unstable, or that the practical consequences of those preferences are less knowable than the practical implications of public and preexisting law in rule of law states.19

To see this, compare two societies: in one society, the law bans pink flamingo lawn ornaments and requires garden gnomes. The first society comports with the rule of law, so citizens know they won’t be punished for any other lawn ornament choices. In the second society, there is an absolute and unconstrained, but rational, dictator (Claudius). Citizens who anger Claudius are punished regardless of the content of the law (if any). It so happens that Claudius hates pink flamingos and loves garden gnomes.

If Claudius’s preferences with respect to lawn ornaments are known and stable, citizens will know to never have pink flamingos and always have garden gnomes, and they will know that Claudius won’t bother them for any other lawn ornaments. Claudius’s subjects will behave exactly as do citizens of the first society, and experience exactly the same amount of interference with their choices.20

However, if they are ruled not by Claudius but by Caligula, whose preferences are unknown and unstable, they will have reason to fear. “Does Caligula hate birdbaths this week? Or does he love them?” Citizens under Caligula will experience all their choices as more costly, in view of the uncertainty about for what Caligula will choose to punish them.21

Linz suggests a useful distinction between an “authoritarian” regime, in which the ruler “exercises power within formally ill-defined limits but actually quite predictable ones,” and a “sultanistic-authoritarian” regime, which features the “arbitrary and unpredictable use of power.”22 The discussion thus far suggests that subjects of sultanistic-authoritarian regimes will be less free than rule of law states, but subjects of merely authoritarian regimes need not be. It seems to me that, for several reasons, we ought to expect the non-rule of law world to be dominated by authoritarian rather than by sultanistic-authoritatian regimes, and thus that even unconstrained officials will be sufficiently predictable in their uses of power that they will not create much more of a chilling effect than will the penumbra of ordinary law.

First, the motives of unconstrained officials have often been fairly transparent. Some are in it for the money, and tend to concentrate their abuse of power on plundering wealthy citizens. Citizens can fairly reliably avoid punishment in their states by not accumulating or displaying riches. Unconstrained officials also tend to persecute their political opponents. Except in those cases where officials are paranoid (Stalin), citizens in their states can fairly reliably avoid punishment by not getting involved in politics and not becoming powerful enough to pose a threat to the existing rulers.23 Many officials have a taste for markers of status; citizens in their states can fairly reliably avoid punishment by treating officials with great deference. Finally, some officials subscribe to religious or secular comprehensive doctrines, and use their powers to enforce them; examples include numerous religious governments as well as the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Citizens in their states can fairly reliably avoid punishment by complying with the official doctrine.

In addition to these generally understood historical motives, officials have some strategic reason to make their preferences known. We may safely suppose that those with political power in non-rule of law states, whether top-level rulers or intermediate officials, have at least four basic self-interested motives. First, each official wants to hold on to her position. Second, each official wants to maximize the rents she receives from power. Third, each official wants to maximize the extent to which citizens comply with her wishes. Fourth, each official wants to maximize her personal freedom of action; that is, if she decides to use her power against someone, she doesn’t want anyone else to intervene and put a stop to it. Officials may have other motives as well, but it does not seem controversial to suggest that they will generally have at least those four.

There is some tension between those motives – particularly, officials who maximize their freedom of action may reduce the rents their societies can generate.24 Nonetheless, some official choices are clearly better than others in respect of all four motives. I submit that an official typically does better to make her preferences known than to conceal them. Whether or not an official makes her preferences known has no effect on her satisfaction of the first or fourth motives – there’s no obvious way in which doing so threatens her hold on power or flexibility in its use. Doing so, however, makes her better off with respect to the second and third motives.

An official must make her preferences known for citizens to comply with them. Claudius is much more likely to never have his sight offended by the presence of pink flamingos if he tells the citizenry just how much he hates them. If his preferences change (suddenly he loves pink flamingos and hates garden gnomes), he again is more likely to be obeyed if he announces the change.25 Announcing his preferences will also make it much easier for subordinate officials to accurately enforce them.26 And announcing his preferences will allow him to economize on the cost of violence: once again, soldiers must be paid, and Claudius may not wish to hire more of them to lop off the heads of pink flamingo offenders when, should he announce his preferences in advance, he may simply threaten to do so and remove disobedience as well as costly violence off the equilibrium path (assuming he has found some way other than the rule of law to make those threats credible).

Moreover, officials who make their preferences known can expect, ceteris paribus, to receive more economic rents from power. This point goes to the heart of the problem with the chilling effects argument: a rational official should strive to avoid chilling citizens’ choices so long as those choices don’t actually conflict with the official’s desires, because citizens with greater practical freedom of choice will be able to engage in more economically productive activity, thus generating more rents for officials to capture.

It might be objected that some officials may prefer citizens to be cautious. Suppose a temperamental ruler systematically overreacts to offense: whatever pleases him pleases him only a little, but whatever offends him offends him mightily. Such a ruler might want all citizens to be walking on eggshells, and might want officials to aggressively punish doubtful behavior in order to shield himself from the slightest possibility of offense. Such a ruler does have some incentive to create a chilling effect, but it’s an open empirical question whether such personalities predominate among rulers (or lower-level officials). At the very least, we do know that some autocratic rulers have created or tried to create fairly explicit and detailed law codes, giving us reason to think that they wanted citizens to know at least some of their preferences.27 For these reasons, I am skeptical of the broad impact of the chilling effects argument.

1 The problem of complexity

More troublingly, modern rule of law societies have very complex laws, which are knowable by citizens in principle, but often only at some cost. It will not always be the case that the cost of learning the law (including expending time in legal research, hiring professional legal counsel, etc.) will be lower than the potential cost of risking breaking it. Those of us in the United States who file our tax returns without professional assistance, for example, seem to have implicitly made the judgment that the risk of making a mistake is worth taking. It is not clear that divining what one must do to avoid violating the Internal Revenue Code is any easier than divining what one must do to avoid angering Claudius (or even Caligula!).

Of course, there is some rule of law ground for criticizing overly complex laws under the principle of publicity. At a certain level of complexity, even fully disclosed laws begin to feel Kafkaesque; it is easy to imagine that someone living under very complex laws may experience her world as one in which those who have studied those laws more extensively (including, obviously, officials) have open threats against her.

Complexity is a troubling problem. It may be that there is a trade-off between legal complexity and discretion in economically advanced societies: as the activities in which people engage and the organizational structures in which they engage in them become more diverse, the number of ways in which the legal system must regulate those activities multiplies; it may do so either through multiplying rules or through making the rules less specific, and hence less constraining over officials.28 If that is true, and if legal complexity really is a problem from the standpoint of publicity, then it would follow both that (1) there is an upper bound on the extent to which we can achieve the rule of law in a complex society, and that (2) there is an indirect tension between the rule of law and a conception of freedom that attends to subjects’ practical scope of behavior: the more organizational and behavioral options people actually have, the less rule of law they can have.

Moreover, the creation of the rule of law not only may be a general-purpose technology of constraint, but it may also go along with general-purpose technologies of complexity. Consider that many economists and political scientists believe that the rule of law facilitates economic development, which in turn creates more scope for complex activities that require complex regulation. It may also be part of a package of institutional changes leading to overall social and legal complexity. North, Wallis, and Weingast, for example, argue that there are three “doorstep conditions” facilitating the transition to “open access” (i.e., vaguely liberal-democratic type) states, two of which are the rule of law (as applied to elites), and (complex) “perpetually lived organizations,” such as the corporate form.29

Furthermore, many Richelieu-like institutional supports for the rule of law (as discussed at the beginning of this chapter, and at greater length in Chapters 6 and 8) may promote the professionalization and bureaucratization of law. Particularly when Richelieu is a judge or an administrative agency (rather than, say, a mass jury), creating institutions with a legal culture that is oriented to making and enforcing rules, and that operates rule-based systems at relatively lower cost, may encourage the creation of more complex legal rules.

For these reasons, modern rule of law societies are likely to be accompanied by a substantial degree of day-to-day citizen legal uncertainty. This is how lawyers stay in business. It follows that for those who do not have access to lawyers, the world may be full of chilling effects, even in a rule of law state. Of course, lack of lawyers is itself a problem from the standpoint of publicity – but a state can get pretty far along the rule of law path (much further than Claudius) without having free universal legal aid, and in doing so risk a bevy of chilling effects. It is not obvious that such a state is any more free, on the chilling effects argument, than many plausible state models that altogether lack the rule of law.

C The planning argument

Consider another argument. The rule of law is often said to protect citizens’ ability to make and carry out plans to achieve their ends.30 This idea has some intuitive grip, particularly on the conventional conception of the rule of law, which requires that official coercion be predictable. Though I argued against this conception elsewhere,31 I will assume it in this section as necessary to cast the planning argument in its strongest form.

The intuition behind the planning argument is that citizens’ liberty depends on their ability to plan and pursue complex and long-term goals, which in turn depends on the predictability of their environment; the rule of law protects that predictability. This is not merely the chilling effects argument under another name. For even if citizens know officials’ preferences, the mere fact that their plans are subject to future disruption if officials’ preferences change may count against their liberty, regardless of whether the prospect of future disruption counts as a cost imposed on their choices in the present.

This argument requires a conception of liberty in which citizens’ abilities to make plans are important independent of the extent to which their choices are interfered with. It’s most natural to turn for this to that family of conceptions of liberty based on the idea of autonomy associated with, inter alia, Kant and Spinoza.32 On such conceptions, an agent is more free to the extent she is self-directed – able to run her own life and make her own rational decisions. An agent is less free to the extent her choices are heteronomous, that is, controlled (or influenced, or caused) by external circumstances or nonrational drives.33 Since making plans is an important rational function by which we may run our lives, it is essential for liberty as autonomy. On the autonomy conception, a citizen whose long-term plans might be disrupted is less free because she is less in control of her own life.

My skepticism about the planning argument is rooted in the intuition that interfering with a citizen’s long-term plans need not keep her from being in control of her own life. For many contingencies may disrupt an individual’s long-term plans, including contingencies rooted in the arbitrary discretion of other people. One might start a business and find that one’s employees all quit to work for a competitor; one might plan a family and turn out to have an unfaithful spouse. Ordinarily, when people make long-term plans, they take into account the possibility that other people might disrupt those plans (e.g., by making contingency plans); for that reason the risk of external intervention does not count against their general ability to plan.34 This is true even when the interventions of others include the use of state coercive force: consider that property rights themselves (and hence others’ uses of them to frustrate our plans) are nothing more than licenses to use state coercion.35

The prospect of outside interventions due to the unconstrained power of state officials may be more disruptive to subjects’ planning capacities than those other interventions, because such power has a tendency to be unbounded and uncertain, sometimes even secret. Caligula, unlike a property owner or an employee, may interfere with one’s plans in unknown and surprising ways that are difficult to plan around, and may recursively interfere in the contingency plans built to account for that interference.36 Such radical uncertainty may undermine subjects’ long-term planning capacities altogether. On the other hand, as noted before with respect to the chilling effects argument, officials have good reason to make their preferences known, such that in many states that lack the rule of law we would nonetheless expect subjects to more or less be able to plan around official interventions. The planning argument may still be persuasive to the extent that subjects in states without the rule of law are unable to make contingency plans on the basis of the prospect of such officials’ preferences changing, but this seems like a fairly narrow range of situations.

There are two interesting variations on the planning argument. The first has not, to my knowledge, been raised in the literature but may appear tempting.37 It might go as follows. The rule of law, by making the legal restrictions on our own behavior and on the behavior of our fellow citizens more or less certain, allows us to make credible commitments to one another, and to carry out complex plans that rely on coordinated action with our fellow citizens. For example, my knowledge that the state will reliably enforce contracts against me as well as against others allows me to precommit to performing my agreements as well as rely on the performance of others, and thus makes those agreements (practically, strategically) possible. This, in turn, is advantageous from a liberty standpoint (i.e., in terms of a positive conception of liberty that attends to the scope of the choices available to me, or from a Kantian autonomy conception of liberty).

The flaw with the credible commitment argument is that the rule of law is neither necessary nor sufficient for the law to create stable expectations between ordinary citizens. As a counterexample to its necessity, consider a state that enforces contracts and property rights between ordinary citizens, but reserves a royal prerogative to imprison or plunder citizens at will – Leviathan, perhaps, or Pinochet. And suppose Leviathan’s intrusions on citizens’ persons and property are relatively minimal, either because he prudently establishes a reputation for restraint just in order to increase economic activity and thus maximize his rents from power,38 or simply due to insufficient administrative resources to interfere with all but the biggest targets. In such a state, citizens will still be able to make plans that rely on contracts with one another.39 As a counterexample to its sufficiency, consider a state that fully comports with the rule of law but whose law provides few or no tools for coordination among citizens; only those contracts specified on a very short statutory list are enforced, no corporations or partnerships are permitted, no private property is permitted in the means of production, and so forth. In such a state, citizens will not have the legal tools to make complex plans that rely on mutual coordination.40

The second variation on the planning argument is another of Hayek’s contributions. In Law, Legislation and Liberty, Hayek argues that liberty-preservingness is a property of common-law systems in which judges state legal rules by attempting to give effect to the preexisting expectations of the parties before them.41 Those expectations, in turn, are structured both by previous statements of legal rules and by the underlying norms and customs of the community.42 This argument is similar to the original planning argument, in that it is premised on the claim that the object of adjudication is to satisfy citizens’ preexisting expectations about their legal rights and obligations. However, it differs in that Hayek argues that a predictable (expectation-satisfying) legal system necessarily has the property of protecting some sphere of individual action independent of citizens’ plans.

For the purposes of argument, we may grant the claim that common law systems track citizens’ preexisting expectations (although that seems to require a fairly idealized view of the epistemic powers of both judges and citizens). Still, Hayek’s argument doesn’t go through.

Hayek argues that expectation satisfaction (that is, predictability) is maximized by a system of rules that carves out a protected domain of activity (that is, negative liberty) for each individual.43 It is meant to follow, I take it, that expectation-satisfying legal systems will be liberty-preserving just in virtue of their conferring protected domains of activity on citizens.

However, even if the relationship between expectation satisfaction and the existence of protected domains of negative liberty holds as a general principle, in any given legal system that protected domain can be large or small, and there is no reason to believe that larger domains will be more expectation-satisfying than smaller domains. As a counterexample to any such notion, consider usury. Most would argue that a legal system that enforces contracts for interest is preferable, from the standpoint of liberal freedom, to an otherwise identical legal system that does not do so. Yet each of those legal systems should be equally expectation-satisfying: in the no-interest legal system, all citizens will expect that usurious contracts will not be enforced and that expectation will be satisfied, and vice versa in the other.

D Neorepublican liberty

Let us now turn to a conception of liberty that is particularly suitable to the rule of law. For neorepublicans such as Philip Pettit, Quentin Skinner, and Frank Lovett, an agent is unfree not when someone actually interferes with her choices, but when someone has the power to arbitrarily interfere with her choices, regardless of whether that power is actually exercised. Unsurprisingly, neorepublicans have said that the rule of law is necessary to prevent the state’s dominating its citizens,44 and aptly so: in states that fail to comport with the principle of regularity, officials have open threats against citizens. An official who has an open threat against a citizen may interfere with her choices at will by threatening to exercise that threat. Such an official dominates the citizens over whom he has open threats.

With this claim, I have no quarrel. It is also wholly compatible with the egalitarian theory of the rule of law, for essential to the idea of domination is a profound inequality. Pettit has repeatedly emphasized that domination is a relational, hierarchical idea, connected to behaviors like bowing and cringing and flattery.45 He has gone so far as to describe domination as “a matter, essentially, of social standing or status” that “involves being able to walk tall, to look others in the eye, to be frank and forthright.”46

Although neorepublicans are right that subjects are dominated in the absence of the rule of law, I am skeptical of the claim that the notion of domination maps to the higher-level concept of liberty, rather than that of equality. This is, however, a debate for another place:47 here we may simply note that the equality thesis fits nicely with neorepublican theory.

Nigel Simmonds offers an interesting variation on the liberty thesis, drawing on both neorepublican and liberal conceptions of liberty.48 According to Simmonds, the mere fact of prespecified and more or less stable rules that guide official coercion (i.e., regularity) preserves a formal domain of individual choice. Even if the law specifies everything I must do with every moment of my life in painful detail (“at 6:03 am, you must eat exactly one hard-boiled egg …”), the mere fact that the rules must be specified, as opposing to leaving scrutiny of my choices to the post hoc discretion of some arbitrary authority, means that it must leave me some area of choice, however tiny, about how I carry out those commands. (Simmonds: “Should I wear a hat whilst doing so?”) Moreover, the Weberian idea of the state as monopolist on violence implies the further limitation that the law must also forbid private violent interference with that reserved space of choice.

However, approaching the question from a strategic perspective shows that Simmonds’s argument is not robust to a world in which officials’ preferences change, or in which officials respond to incentives given by the prospect of behavioral innovation among the ruled. With respect to preference change, while it is true that having to think up and specify the restraints one wishes to impose on people in advance limits the extent to which one can coerce them, it also means those coercions can persist through preference change (either within one official or across officials), especially in a robust rule of law state in which officials enforce the law because they support lawfulness for its own sake (i.e., one in which Richelieu has been created and empowered). Thus, we may see archaic laws enforced through bureaucratic inertia by or in the name of officials who do not actually care whether the conduct commanded is carried out; by contrast, in a state without the rule of law, the preferences of prior generations of officials have no institutional means to perpetuate themselves: if the new king no longer cares about 6:03 am egg eating, he may stop forcing people to do so.

With respect to behavioral innovation, a ruler or legislator who is uncertain about how people might offend her preferences has an incentive, in a world in which she must rule only by ex ante law, to regulate more broadly than she might otherwise choose. Taking Simmonds’s hat example, suppose that our ruler is not currently offended by any of the hats people wear right now. However, she knows that people are endlessly creative, and worries that, in the future, people may make hat choices that she considers ugly. In order to forestall this prospect, she has an incentive, when enacting the law, to attempt to specify a complete list of permissible headgear, and, in doing so, forestall not only potential offense from future hat innovations, but also perfectly inoffensive hat innovations. By contrast, in a world in which she coerces people purely by case-by-case discretion, she is capable of punishing only the ugly future hats, not the attractive ones as well, and of hence leaving citizens more long-run hat-wearing freedom.

The two problems are merely an aspect of one well-known bug in legal rules: legal philosophers have long pointed out that rules are both underinclusive and overinclusive; Simmonds’s argument for the proposition that ruling by law preserves a space of freedom focuses all the attention on the underinclusiveness wing. But although a legislator may choose to make legal rules underinclusive with respect to the expected impact of future behavioral innovations on her anticipated future preferences – in scientific terms, prefer type II errors to type I errors – she may instead choose to make them overinclusive, that is, to prefer type I errors.

Simmonds’s second point – that the formal protection of legal rules against type II errors has to be backed up by the state’s monopoly over force, and thus carves out a space of freedom from private domination – is also incorrect. It is simply untrue that, as Simmonds claims, “[t]o make its governance effective, and to retain a substantive monopoly over the use of force, a regime must prohibit potentially coercive interferences.” To the contrary, a regime may not care about coercive interferences except insofar as those interferences themselves interfere with its commands.

Simmonds wants to derive antidomination from the Weberian notion of a state. Yet in a footnote, he acknowledges that such a state may have a “formal” monopoly of force, insofar as it allows the domination of some citizens by others “while pointing out that the conduct derives its legitimacy from the regime’s will.” In order to foreclose this possibility, and thus retain the claim that the state must restrain private violence, Simmonds mysteriously claims that “the Weberian analysis derives its plausibility from the way in which the monopoly of force is one facet of the state’s instrumentalization of force in the service of its goals,” which “requires a substantive monopoly, not a formal one.” As far as I can comprehend this argument, I take it to mean that a Weberian state must actually direct the force it permits in pursuit of its goals; it may not simply allow private force to run amok and then claim that the private violence occurred with its permission. But this is not accurate. The state’s goals may include economizing on law enforcement in order to pursue other priorities; in such an event, it may well allow private violence to occur in furtherance of its goals, although not, as with the case of Jim Crow as discussed in the previous chapter, to withdraw the protections of law unequally, from some rather than others.49

E Democratic liberty

To close this section, let us consider a family of arguments that connect the rule of law to a family of democratic conceptions of liberty as collective self-rule. These arguments tend to rest on the principle of generality, and suppose that democratic liberty requires the state to produce only laws that treat citizens as equals. Thus, for example, Dworkin suggests that democratic legitimacy requires the laws to treat each citizen with “equal concern.”50 Rousseau claims that the general will can only generate laws that are themselves general.51 Hayek claims that “so far as men’s actions toward other persons are concerned, freedom can never mean more than that they are restricted only by general rules.”52

On a formal conception of generality, the claim that general law has anything to do with freedom seems implausible on its face. It’s counterintuitive to think that the law “Joe Smith may not criticize the government” is more freedom-infringing than the law “No one may criticize the government” just because the former law has a proper name in it. On any conception of liberty discussed so far, everyone, even Joe Smith, is as unfree under the second law as under the first, and everyone but Joe Smith is less free under the second.

However, on the public reason conception of generality, Rousseau’s claim that the general will can only issue general laws is quite plausible. If a law makes distinctions between citizens that are unjustified by public reasons, that law will disregard some citizens’ legitimate interests; if that’s the case, it cannot be a product of a general will, which is directed only at the general interest. And since, on a Rousseauian conception of democracy, the general will is what preserves the freedom of citizens within a state, nongeneral laws are not consistent with freedom. It would follow that the rule of law is necessary for freedom.

This argument is unsatisfactory as a general normative grounding of the rule of law, because it has nothing to say in defense of the rule of law in a nondemocratic state. By contrast, the egalitarian arguments in Chapters 1 through 3 are at least partially compatible with nondemocracies: an absolute monarchy that restricts itself to using violence against its people pursuant to public law, or that treats its subjects as equals rather than establishing legal hierarchies among them, is surely more morally valuable than the alternative. A Rousseauian democratic conception of liberty may give us additional reason to suppose that the rule of law is morally worthwhile in democracies (I say more about the relationship between the rule of law and democracy in Chapter 8), but still needs the egalitarian conception of the rule of law for the general case.

III Libertarian equality

The conventional claim that the rule of law supports individual liberty can actually be pressed into service in support of the equality thesis of the first three chapters. This potential appears in sharp relief when we consider Raz’s discussion of the relationship between the rule of law and autonomy. While he gives lip service to the conventional claim that unpredictable or nonprospective law is a threat to citizens’ autonomy, his actual argument for that proposition relies on the idea that it insults their autonomy.53

The insult claim is quite plausible for many ways in which the rule of law may be violated. Raz frames his version of the argument in the context of the planning conception of the relationship between the rule of law and liberty that I discussed earlier, and which is particularly amenable to the notion of an insult to autonomy. To ignore previously established legal entitlements is to disrespectfully disregard the likelihood that subjects have made plans in reliance on those entitlements; to take property without legal process is to disrespectfully disregard the likelihood that the property in question is instrumental in subjects’ plans. Although Raz doesn’t flesh out the claim in any detail, it’s easy to believe that arbitrarily frustrating subjects’ plans is to express disrespect for their capacity to plan in the first place.54

Raz distinguishes “insult, enslavement, and manipulation” as the three ways in which one might achieve “an offence to the dignity or a violation of the autonomy” of another. Enslavement and manipulation are, obviously, violations of autonomy. Equally obviously, insult is an offense to dignity (as are enslavement and manipulation). But we ought to understand this as a core egalitarian claim. Delivering an insult is a characteristic behavior of someone who thinks himself better than the one insulted. Similarly, respect is the characteristic attitude one displays to an equal, in contrast to the condescension and subservience displayed to, respectively, an inferior and a superior. The idea that violations of the rule of law insult the autonomous planning capacity of their victims is rooted in the ideal of equality.

Similarly, in a passage entitled “The View of Man Implicit in Legal Morality,” Lon Fuller explains that the normative criteria that he applies to law (which track a plausible conception of the rule of law) imply claims about the kind of beings over whom a legal system operates.55 The rule of law “involves of necessity a commitment to the view that man is, or can become, a responsible agent.” Accordingly, violating it “is an affront to man’s dignity as a responsible agent,” and to do so with respect to a specific person “is to convey to him your indifference to his powers of self-determination.”

In those arguments we can see a strong isomorphism with the expressive theory of this book. An official who chooses to respect or to disregard the rule of law engages in conduct that is susceptible to interpretation on the basis of the attitudes with which those choices are most consistent. Rephrased in my terms: to comply with the rule of law is to express the attitude that one’s fellows are capable of self-determination; to decline to do so is to express the opposite.

Moreover, to insult someone’s autonomy in that way is to act with hubris toward him or her, as I described in Chapter 1. Hubris in the rule of law context is the assertion of authority over someone based not on the responsiveness of that authority to the right kinds of reasons, but based on a gap in personal qualities between oneself and the other: because of one’s superiority or the other’s inferiority – a kind of assertion that, when made in the context of giving orders backed up with force, amounts to the assertion that the other is not entitled to make his or her own decisions.

We can understand the Raz and Fuller arguments as a kind of equality about liberty.56 That is, they are plausible arguments for the notion that to coerce people unbound by the rule of law is to treat those people as inferiors. The connection (the mapping rule, if you will) between the violation of the rule of law and the expression of an attitude about inferiority incorporates a conception of people as free. Yet, the rule of law can respect people’s free nature even as the law undermines their enjoyment of freedom.

I will explain further. A free person is one who has the power to make self-determining, autonomous choices. When we order such a person about, if we offer her the right kinds of reasons (drawn from law that meets the principle of generality, implemented in a way consistent with allowing her to argue back, etc.), then we hold out the possibility that she might obey those orders autonomously, as an act of free choice, rather than simply as a response to brute force – and this is so even though brute force is omnipresent in the background, and she is not genuinely free to disobey the command. In that way, (rule-of-law-compliant) law possesses, as Habermas has suggested, both “facticity” and “normativity”: it is presented to people both as a brute reality – “Do this or you will be shot” – and as something that offers genuine reasons that can be complied with by an autonomous agent.57

The implicit utterance underneath every general law, “Do these things for the following good reasons, and also, if you don’t, I’ll hit you with this stick,” thus expresses respect for the status of those addressed as beings capable of following the law for the good reasons, that is, as free in a Kantian sense. But we cannot ignore the stick. Ultimately, that utterance is still a threat that forces the one threatened to do what is required on pain of violence. For that reason, there will always be a threat to freedom implicit in the law, prefaced with a “rule of” or otherwise.

But we are not yet done with Fuller. Kristen Rundle offers an important reading of Fuller’s “View of Man” passage.58 On her argument, the dignity that Fuller sees the law respecting is not merely that of an adult who can voluntarily choose to follow the good reasons that apply to her, and that are expressed in the law. Rather, the legal conception of the agent is of one on whom the rules themselves depend, in Rundle’s words, “akin to the Greek conception of the citizen … an active participant in the legal order.” The subject is not just running her own life; she’s also running the life of the polis. For Rundle, this is meant to capture two forms of participation: first, directly in the procedures of the legal system – as litigant or juror, perhaps – and second, participation through giving or withholding consent to that system.

For Rundle’s Fuller, these kinds of participation make up a conception of reciprocity inherent in a well-ordered legal state. As I understand it, this is meant to be a moral relationship: citizen and official co-create the legal order by acting in accordance with the agency of the one and the reasons represented by the other, as well as the shared expectation that the rules will be respected by all.59

However, as I shall suggest in Chapter 6, the two forms of participation are interdependent. By making use of the participatory institutions of a legal system, citizens have the capacity to signal their commitment to or rejection of it – even in nondemocracies – and the stability of the system depends on that signaling. This is consistent with Fuller’s conception of reciprocity, but gives it a new dimension: as we saw at the beginning of this chapter, in addition to the normative relationship, there is also a strategic relationship of reciprocity between official and subject: the rule of law allows subjects to control officials, and, by doing so, also allows officials to control subjects.

This idea of reciprocity also suggests a point that I will develop further in Chapter 8: if, as I have been arguing, the rule of law essentially captures the idea of coercing people only under the color of reasons that you have addressed to them, then participating in the rule of law – either as an official or perhaps even as a citizen – will tend to train one to think of those with whom one interacts through legal institutions as agents capable of responding to reasons, and to whom reasons are owed. As I will argue further in Chapter 8, this may suggest that the rule of law has the capacity to generate as well as express the understanding of citizens as of equal status. Moreover, Chapter 8 argues that the rule of law will be more stable to the extent that the substance of law is genuinely general, in the sense that it reflects the equal status of all through public reasons.

Having foreshadowed those claims (and with the hope that the reader will suspend disbelief in them until they can be defended in a few chapters), we can accept Fuller’s argument, as elucidated by Rundle, and take it still further. The rule of law both expresses respect for and depends on subjects of law who respond to public reasons that treat them as equals. Such subjects will be responsible agents in fact – the legal system will depend on their responding to such reasons – and will be treated as such in an expressive sense. Such agents are free, in the sense that it is their exercise of agency that permits the legal system to exist, and they are equal in the further sense that their exercise of system-supporting agency is a response to being treated as equals.

In sum, to treat subjects as equals for rule of law purposes is to treat them as agents who are responsive to public reasons both with respect to their individual lives – in terms of the substance of the law that is uttered in their names and that they are asked to obey – and with respect to their collective lives, capable of and in fact choosing to act in public to uphold a legal system that so treats them.

At this point, the core case for the egalitarian conception of the rule of law has been built and reconciled with the arguments for the more traditional idea that the rule of law preserves individual liberty. Subsequent chapters move from construction to application, recognizing (a) that normative and conceptual work in political philosophy can and should be useful to social scientists as well as political actors in the real world, and (b) that a conception of an “essentially contested concept” such as the rule of law ought to be able to prove its worth outside the armchair. In order to do so, we shall immediately begin with the historical home of Rundle’s “Greek conception of the citizen,” and see that in Athens, the citizen was indeed “an active participant in the legal order,” understood as the linchpin of a network of trust and commitment that protected the equal standing of all citizens.