In India, as elsewhere, one must often abandon one’s attempt to determine among the attested versions of a mythical narrative the one from which all the others, whether contemporary or later, have supposedly derived. Even from the most ancient times variants have existed, each as legitimate as the next.

The Babylonian Flood story is the only mythical account in ancient Mesopotamian culture about a radical renewal of a world order already in existence, resulting in the immortalization of its human protagonist. It is also the only mythical account from ancient Mesopotamia that depicts a paradisiac locale of immortalization. Renewal in the Flood story takes place as a result of the total destruction of the old world order, with the kernel of a pristine cosmos preserved inside the boat the Flood Hero builds to survive this aquatic cataclysm. Here, I refer to this boat as the ark, a term I use in its simple sense, with no intention to emphasize links with the Bible and Noah.

In the “classical” Flood narratives of the Old Babylonian period, while it is the ruler god Enlil who tries to destroy humanity on account of the nuisance it has caused for the gods, it is the god of wisdom and magic and lord of the Apsû, Enki/Ea, who instructs one representative of humanity, the Flood Hero, to build a boat in order to escape the Flood, the final catastrophe inflicted by Enlil on mankind in a chain of attempts at destruction.2 The story is found, albeit incompletely, in two texts from the Old Babylonian period, the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs, in Akkadian, and the Sumerian Flood Story, in Sumerian. In the former, the Flood Hero is called Atrahasis, in the latter, Ziusudra.

As indicated in Chapter 1, the Old Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh also contains the character of the Flood Hero, named Utnapishtim, although a narrative of the Flood story belonging to this text has not come to light. The Standard Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh from the Neo-Assyrian period, in turn, contains the most complete Flood story from ancient Mesopotamia.3 In the present framework, I adopt an integral approach to the treatment of these texts in an analysis of the “investiture” painting, whereby references to the much later but more complete Flood narrative in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh concentrate on, but are not restricted to, its aspects that have their clear counterparts in the earlier Old Babylonian Flood narratives.

A Note on Method

One might ask what the Mari painting has to do with the Flood story. Both the painting and the myth are too familiar to the scholar of the ancient Near East. A connection between them, so far not drawn, may easily strike one as off the wall. On the one hand, the Flood story generates a range of presumptions and prejudices, both because of its biblical repercussions and its contemporary impact on popular consciousness, including all kinds of eccentric views, with the physical search for Noah’s ark still continuing. On the other hand, the study of the kingdom and site of Mari is a highly specialized academic matter, a full-fledged sub-field within the study of the ancient Near East. The copious archive of the Old Babylonian palace and the extensive archaeological remains of the site have generated voluminous scholarship.

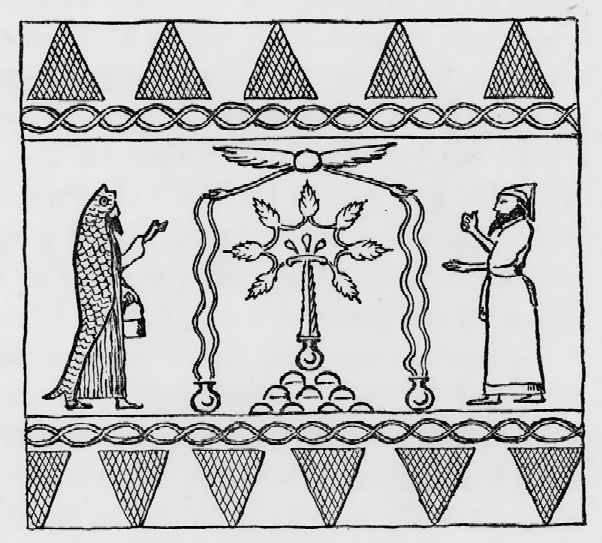

Despite extensive documentation of the site of Mari and its socio-political and economic affairs especially in the early eighteenth century bce, its art is still poorly understood.4 With its visual vocabulary paralleling the iconographic repertoires of ancient Mesopotamian works of art before and after it and resonating with conceptions of paradise, immortality, and ascent, the “investiture” painting would be scrutinized most fruitfully within the continuum of the visual language of the ancient Near East and its metaphysics. As such, the themes of the Mari painting, renewal, a paradisiac garden, the flowing vase as a symbol of passage or access to a terrestrial realm of purity, all set within a macro-cosmic environment of hierarchy, are directly evocative of the deeper message of the ancient Mesopotamian Flood myth, the (re)creation of a pristine terrestrial land and its human but immortal inhabitant.

Annus has posited that the survivors in the ancient Mesopotamian Flood stories are always kings such as Ziusudra, Atrahasis, and Utnapishtim.5 According to Annus, the persons who mastered the Flood by surviving it were demigods and bearers of antediluvian wisdom.6 In his recent work, Irving Finkel, however, has stated that even though the Sumerian Ziusudra was a “priest-king,” neither Atrahasis nor Utnapishtim is referred to as a king in the relevant texts in Akkadian, and that there is no reason to think that they were.7 Finkel, however, passes over Ziusudra’s identity as king quite lightly, as the Sumerian Flood Story (v. 145), a major text of the ancient Mesopotamian Flood repertoire, explicitly refers to him as lugal, king in Sumerian.8 Furthermore, Utnapishtim is the Akkadian rendition of the Sumerian name Ziusudra.9 In the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, Utnapishtim is addressed as the “son of Ubar-Tutu,” the king of Shuruppak, the last of the five antediluvian cities of Babylonia before the Flood strikes, according to the Sumerian King List (vv. 30–35).10 As the son of the last antediluvian king and the one who experiences and survives the Deluge, Utnapishtim is clearly of the royal line, even though his reign seems not to come to fruition on account of the Flood catastrophe.

Even the lack of the designation “king” in the extant parts of the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs may not be enough to brush aside implications of kingship from this text, since in the poem Atrahasis is capable of summoning the elders of his community and making declarations to them regarding his decision to leave their city to join Enki/Ea in his subterranean abode, as quoted in full further below. In this respect, Atrahasis is at least a personage of importance and influence in his polity. Last but not least, the Sumerian King List itself is as much about kingship as it is about history, and it features the Flood as the principal turning point in its chronological configuration. Thus, it is reasonably sound to think of ancient Mesopotamian Flood traditions as closely linked with the ideology of kingship. The kind of kingship referenced by the Flood mythology, however, is not a typical mode of rule, but a supra-political understanding of kingship, whereby its possessor had certain intellectual and spiritual powers not accessible to his community or ordinary humanity, as Annus has observed.11 The royal ideologies of the ancient Near East expressed precisely this kind of kingship through the image of the king in their regal art, whether or not the actual personal qualities of the king as a human being in a particular state during a particular era warranted it.12

The Ideal Enclosure and the Ideal Garden

In addition to the motif of the flowing vase, there are two major themes in the Flood story that call for a consideration of certain elements of the Mari painting in light of the paradigms they offer. The first is the presence of a hermetically sealed capsule, the boat built by the Flood Hero, an enclosure evocative of the Apsû, in which the seeds of a new world order are embedded. This aspect of the Flood myth parallels the semantics of the central rectangular enclosure of the painting (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). The second is the reference to a faraway land of immortality, where the Flood Hero is placed in the aftermath of the Flood, a land that is clearly part of the earth but also magical in essence, co-extensive with, or in close spatial proximity to, the Apsû, the Dilmun of the Sumerian Flood Story. As for this aspect of the Flood story, it resonates with what I have referred to as the arboreal incarnation of the Apsû outside the central panel of the Mari painting.

While the construction of the boat under instructions from Enki/Ea is clear in the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs, the immortalization of the Flood Hero and his placement in Dilmun in the distant East is clear in the Sumerian Flood Story. The relevant passages from both texts, followed by their counterparts in the Standard Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, are well worth quoting in translation. In the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs, the god Enki/Ea speaks to Atrahasis: “Destroy your house, build a boat, / Spurn property and save life / The boat which you build / …] be equal [(…)].”13 It is a pity that the description of the boat is missing here, but when the text resumes, we read: “Roof it over like the Apsû / So that the sun shall not see inside it / Let it be roofed over above and below.”14 Before embarking on the ark, Atrahasis tells the elders of his community: “‘My god [does not agree] with your god, / Enki and [Enlil] are angry with one another. / They have expelled me from [my house(?)], / Since I reverence [Enki], / … / I can[not] live in [your…], / I cannot [set my feet on] the earth of Enlil.”15 The phrase “[r]oof it over like the Apsû” suggests an affinity between the structure being constructed under Enki/Ea’s instructions and the god’s own abode, both sealed enclosures into which sunlight cannot penetrate. This statement cannot be a fortuitous simile. The speaker is Ea and part of the instructions he gives for the construction of the ark evokes the design of his own sacred enclosure.16

The parallel passages from the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh read: Enki/Ea speaks to Utnapishtim: “O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubar-Tutu, / demolish the house, build a boat! / Abandon riches and seek survival! / Spurn property and save life!’ … The boat that you are going to build, / … / cover her with a roof, like the Apsû.”17 …”Then also you will say to them [the elders] as follows: / ‘For sure Enlil has conceived a hatred of me! / I cannot dwell in your city! / I cannot tread [on] Enlil’s ground! / [I shall] go down to the Apsû, to live with Ea, my master; / he will rain down on you plenty! / [An abundance] of birds, a riddle of fishes! / […]…riches (at) harvest-time! / In the morning he will rain down on you bread-cakes, / in the evening, a torrent of wheat.”18

In both the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs and the Gilgamesh passages quoted above, by embarking on the boat, the Flood Hero enters the magical domain of Enki/Ea to be preserved from destruction and eventually immortalized. In the Mari painting, the bottom register of the central panel, especially with its aquatic doorway, reflects this condition of entering an aquatic environment that is effective during a process of purification and renewal. In the Flood story, the period spent in the boat is also such a transitional or intermediate process that results in the immortalization of the Flood Hero after the Flood has receded.

Regarding the immortalization of the Flood Hero in the aftermath of the Flood, we find the following verses in the Sumerian Flood Story: “The king Ziusudra / Prostrated himself before An (and) Enlil … (who) gave him life, like a god, / Elevated him to eternal life, like a god. / At that time, the king Ziusudra / who protected the seed of mankind at the time(?) of destruction, / They settled in an overseas country, in the orient, in Dilmun.”19 The parallel passage in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh reads: “Enlil came up into the boat, / he took hold of my hand and brought me out / He brought out my woman, he made her kneel at my side, / he touched our foreheads, standing between us to bless us: / ‘In the past Uta-napishti was (one of) mankind, / but now Uta-napishti and his woman shall be like us gods! / Uta-napishti shall dwell far away, at the mouth of the rivers!”20

In a parallel reading of the elements of the Mari painting against the conceptual backdrop offered by these passages, one could ask if the upper register of the central panel corresponds, by analogy, to the immortalization of the Flood Hero by the gods governing the cosmos after his emergence from the boat. Such an implication is very much there, but I have proposed to understand the upper register as a celestial domain presided over by Ishtar, and the act depicted as one that amounts to apotheosis, or divinization. In the Flood myth, by contrast, the Flood Hero is placed after the Deluge in a liminal terrestrial domain in an equally liminal status through his immortalization in human form without apotheosis.

The Flood Hero certainly does not ascend to heaven. Instead, he is placed apart from ordinary humanity in a faraway terrestrial location for an indefinite period of time. In other words, it is as if he made a transition from one form of the Apsû, the sealed enclosure of the boat, to another, its paradisiac incarnation on the surface of the earth. Here he is to remain immortal indefinitely. Thus, there is something open ended, unfulfilled, and indeterminate about his position. One inevitably asks how long he would remain in this state in this location, and whether at some point in the distant future he would be released from this condition to join the divine sphere in the proper sense of the word apotheosis.

In the historical Judeo-Christian tradition, paradise was thought to exist “as a place where the just awaited resurrection and final judgment, which was thought to be close at hand.”21 There were divergent opinions as to its exact location. On the one hand, it was thought to be located “in a remote part of the earth, preserved in its original state, but become inaccessible.”22 On the other hand, as expressed by Jean Delumeau:

paradise had been removed from our earth and transported to heaven or, more exactly, to the “third heaven” to which St. Paul was caught up and that was not to be confused with the “seventh heaven” of eternal happiness and beatific vision. In this place of waiting, … two persons in particular were dwelling: Enoch and Elijah, both of whom had been removed from the sight of the living without passing through death.23

As stated further by Delumeau, “in the church of the early centuries paradise does not yet mean … the ‘kingdom of heaven,’ as it will later on.”24 This liminal configuration of paradise is parallel to ancient Near Eastern manifestations of an intermediate locale of blessedness and longevity, conveyed by the aquatic and vegetal elements of the Mari painting, rather than a state of transcendent eternity and divinity, expressed instead in the Mari painting by the encounter between the king and the goddess Ishtar.

The liminal state of the Flood Hero is in greater harmony, again by analogy, with the indeterminate visual mode found in the Mari painting than it is with the scene of encounter between the Mari king and Ishtar. The indeterminate mode is especially prevalent in the lateral panels of the outer landscape, with their implying the beginning of a process of ascent that is not carried through its climax, as discussed in the previous chapter (Figs. 2 and 5). In the aftermath of the Flood, the Flood Hero might as well have been fully divinized and taken to the sky, like the ancient Egyptian king of the Pyramid Texts, as the promise may very much be there, albeit suppressed.25 It is the fulfillment of such a potential of ascent and divinization that the upper register of the central panel of the Mari painting shows, expressed through the ring and rod and Ishtar as the lady of heaven. Implications of a process of renewal and the resultant state of immortalization, in turn, are rather embedded in the lower register of the central panel and the outer scene, with the upper representing a state that is even beyond immortalization, apotheosis. The central panel as a whole is then the synopsis of an entire metaphysical process. This process, in its two stages, is visually set within an enclosure modeled after the Apsû, just as the ark, a construction also like the Apsû, is the physical link in the Flood story between a primeval era and a future world order, containing elements of both.

The Ideal Temple

There is a close affinity between the Apsû and the ark of the Flood stories on the one hand, and between the latter and the archetypal ancient Mesopotamian temple on the other, as pointed out in a compelling way by Steven W. Holloway.26 It is a pity that no complete description of the boat built by the Flood Hero exists in the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs. The recently discovered Old Babylonian Ark Tablet, quoted below, however, fills an important gap in this regard.27 As Lambert and Millard state, the Old Babylonian Poem of Atra-ḫasīsdoes not feature the “midrashic elaboration of Gilgameš XI, where the boat is a veritable Titanic with six floors.”28 In light of the parallelism between the basic elements of the Flood narratives in the Old Babylonian and Standard Babylonian texts quoted above, however, one cannot ignore the description of the Flood Hero’s boat preserved in the later Gilgamesh text in probing the nature of ideal or cosmic enclosures in ancient Mesopotamia as represented in both text and image.

According to Holloway, the ark described in the Flood story in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh is no simple boat, but an archetypal structure or enclosure, such as the Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon.29 In a discussion of the analogy between the ark and the temple in ancient Mesopotamian and biblical traditions, Holloway views the textual description of the ark in the Epic of Gilgamesh as in harmony with the principles of composition belonging to this ziggurat as described in the so-called Esagila Tablet from the Seleucid period (312–138 bce), which specifies the height, length, and breadth of the ziggurat as equal.30 In the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, the Flood Hero, Utnapishtim, describes the ark: “one acre was her area, ten rods each her sides stood high, / ten rods each, the edges of her top were equal / I set in place her body, I drew up her design: / I gave her six decks, / I divided her into seven parts. / I divided her interior into nine.”31

As already noted by scholars, this description of the Flood Hero’s boat indicates that the structure is a cube divided into seven compartments by means of six decks, with a further division of the interior space into nine, the exact nature of which is not entirely clear.32 Thus, the ark is of an ideal geometric form incorporating ideal numerological symbolism. The ideal, hence unrealistic, nature of the form of the ark can also be detected in the passage from the Old Babylonian Atra-ḫasīs quoted above in which one of the instructions for the construction includes “roofing it over both above and below (eliš u šapliš).” Ordinarily, a roof covers only the upper part of a structure, whereas the text blurs the usual distinction between above and below, drawing attention to the supernatural qualities of the ark.

The recently discovered Old Babylonian Ark Tablet, too, not only parallels the rhetorical aspects of the Atra-ḫasīs and Gilgamesh passages, but also prescribes an ideal design for the ark, whose scheme is to be drawn in a circular plan, with equal length and breadth. In this text, even though not specified, the speaker is again in great likelihood Ea: “Wall, wall! Reed wall, reed wall! / Atra-hasīs, pay heed to my advice, / That you may live forever! / Destroy your house, build a boat; / Spurn property and save life! / Draw out the boat that you will make / On a circular plan (eṣerti kippatim); / Let her length and breadth be equal, / Let her floor area be one field, let her sides be one nindan high.”33 Finkel, who published this text for the first time, makes much of the mention of a circular plan in the description of the vessel, arguing that the Old Babylonian ark was a coracle.34 He understands the specifications in the text for the equality of the length and breadth of the structure as a stylized expression of circularity as well, the way a god would note the characteristics of a circle.35 On the basis of the occurrence of the word kippatu, meaning circle or circumference, in the Gilgamesh text, translated by A. R. George as “area” (“one acre was her area, ten rods each her sides stood high”), as well, Finkel argues that underlying even the ark described in the Gilgamesh text is a round scheme, the cubic and multi-tier configurations being the result of the much later “midrashic” elaboration of this “iconic vessel.”36

Without intervening in a discussion on the shape of the ark of the ancient Mesopotamian Flood traditions, I would again observe the highly conceptual, almost esoteric, nature of these descriptions. In the Old Babylonian Ark Tablet, the lines “[d]raw out the boat that you will make / on a circular plan (eṣerti kippatim)” may not unequivocally mean “make the boat circular in shape.” Furthermore, the mention of a circular plan along with equality of length and breadth may be comparable to the idealism of roofing a structure both above and below, an inherently impossible configuration within realistic parameters. The Ark Tablet is further revealing in its spelling out the phenomenon of immortalization integral to Flood narratives at the outset: “Atra-hasīs, pay heed to my advice, / That you may live forever (tabālluṭ dāriš)! (my emphasis),” a phrase lacking in the extant Atra-ḫasīs and Gilgamesh texts.

In light of the variety of ideal or archetypal forms that the ark or the temple may draw upon in the ancient Mesopotamian textual record, the entirety of the central enclosure of the “investiture” painting can be considered as such an ideal enclosure. This structure contains in it the kernel of a new world order modeled after the primordial cosmos represented by the Apsû, which it encompasses most conspicuously in its lower register (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). The central enclosure of the Mari painting is certainly not a figural depiction of the boat built by the Flood Hero, nor is the painting as a whole the visual narrative of the Babylonian Flood story. But with its multiple bands of frame incorporating the numbers six and seven, the central panel should be considered as an ideal enclosure with a cosmological symbolism like the ark, as described basically in the Old Babylonian texts but in much greater elaboration in the Standard Babylonian account of the Flood story.

Numerological Symbolism

The numbers six and seven, which characterize the internal division of the structure of the ark in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh text, also occur in the description of the duration of the Flood both in the latter and the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs.37 In Atra-ḫasīs, we find the following verses: “For seven days and seven nights / Came the deluge, the storm, [the flood].”38 As for the Gilgamesh text, we read: “For six days and seven nights, / was blowing the wind, the downpour, the gale, the Deluge [laying flat the land] / When the seventh day arrived, / the gale relented, […] / The sea grew calm.”39

Along similar numerological lines, Horowitz states that there existed a tradition of seven heavens and seven earths “in the Near East during the later part of the first millennium B.C.E. and the first millennium C.E.,” mentioning contemporary Hebrew and Arabic texts, such as the Hebrew Book of Enoch and the Koran, which “present cosmographies in which seven heavens and earths are explained in detail.”40 According to Horowitz, a Sumerian conception of seven heavens may be inferred from certain incantations:

Despite the absence of direct evidence for seven superimposed heavens (an) and earths (ki) in Sumerian and Akkadian texts, indirect evidence for understanding [the Sumerian phrases] an.7 ki.7, an.7.bi ki.7.bi, and an.ki.7.bi.da as allusions to 14 cosmic regions is available. If the phrases in the incantations allude to multiple heavens and earths, then these incantations invoke heavens (an) and earths (ki) to cure a supplicant.41

Horowitz also notes a parallelism in construction between the phrases referring to the seven earths and seven heavens in the incantation texts and the phrase found in the Sumerian Flood Story referring to the seven days and nights that constitute the duration of the Flood, in a way pointing out how such numerological parallelism is not purely incidental.42 The numbers six and seven occur frequently in ancient Mesopotamian texts and thought, but often in a spatial, geometric, temporal, and hence cosmologically charged sense. The system of graded framing found in the Mari painting through its seven concentric linear elements defining six bands also communicates the temporal and spatial stages of a hieratic process such as ascent to heaven. This configuration is comparable to the Flood narratives’ depicting a spatial gradation and temporal sequence in the structural design of the ark and the duration of the Flood, respectively, in laying out a process of transition and restoration.

A New Cosmic Order

The fact that an ascent to heaven is not the case in the aftermath of the Deluge in the Flood myth indicates that the new status of the Flood Hero is liminal, somewhere between humanity and divinity, far away from both, but closer to the divine in its immortality. His new home is one in which the pristine and magical qualities of the antediluvian cosmos are maintained. This ideal land is conceived as Dilmun in the East in the Sumerian Flood Story, and as the “Mouth of the Rivers” (pî nārāti) in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, both of which are associated with Enki/Ea and the Apsû itself.43 By analogy, the outer scene of the Mari painting also implies the magical and liminal qualities of an intermediate land of immortality, signaling through its visual elements the potential of further ascent, but also stretches temporally and spatially ad infinitum (Figs. 2 and 5).

The landscape in the painting may further be understood on the analogy of the fertility and abundance associated with the aftermath of the Flood in ancient Mesopotamian myth. In addition to its destructive impact, the Flood eventually purifies and initiates a new or “repristinated” world.44 In the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, when the time comes for the Flood Hero to embark on the ark to escape the Flood, he is instructed by Enki/Ea to tell the elders of his city that he is going down to the Apsû to live with his master Ea, who will bring upon them a rain of plenty. This statement could not simply be an ordinary lie invented to deceive the fellow citizens of Utnapishtim and dispel attention from his hidden plan of escape. As stated rightly by Lambert and Millard in relation to the Old Babylonian Poem of Atra-ḫasīs, “Atra-ḫasīs now has to explain his actions to the elders. He told them quite truthfully that Enki and Enlil had fallen out, so he, a protégé of the former, could no longer live on the latter’s earth. He must, then, be off in his boat to live with his own god” (my emphasis).45 In both texts, the Flood Hero’s statement is a parabolic or cryptic indication, if not an announcement, of what actually is about to happen, rather than words of trick and deceit. The Flood Hero may not be descending to the Apsû literally to live with Enki/Ea, but by embarking on the ark under the instructions of this god and staying enclosed in it throughout the duration of the Flood, he certainly leaves the domain of the god of the now expired world order, Enlil, and remains in an occluded environment like the Apsû under the aegis of his master Enki/Ea, lord of the Apsû, in preparation for the new circumstances.

The rain of plenty mentioned by the Flood Hero in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh must again be no simple verbal stratagem to give masses the impression that something good is coming and divert their attention from the impending disaster. Rather, it must be another cryptic indication for the ultimate purification and fertility that the Flood waters will bring the world after the destruction. The additional reference to birds, fishes, cakes, and wheat complements the emphasis on abundance. In fact, verses from the Sumerian poem Enki and the World Order, in which Enki characterizes his own bounty, are quite comparable: “When I approach heaven, a rain of abundance rains from heaven. When I approach earth, there is a high carp-flood. When I approach the green meadows, at my word stockpiles and stacks are accumulated.”46 In the Gilgamesh passage, what on the literal level seem to be statements of favorable portents meant to deceive may in fact be loaded with truthful tropes crucial to the genuine meaning of the Flood story.47

Flood Vision

The idea of an initiation in the Apsû below, followed by an encounter with divinity outside or above can be found in the myths of Ninurta and Adapa as well. In Ninurta’s Journey to Eridu (I 8–23), Ninurta acquires the me’s, the cosmic forces, in the Apsû at Eridu “in order to ensure abundance and fertility for Sumer.”48 Fragment B (53’) of the Adapa myth, discovered at Tell el-Amarna and dated to the fourteenth century bce, depicts the sage Adapa plunging into the Apsû, where Enki/Ea gives him instructions for his visit to the heaven of Anu. In heaven, Adapa is offered the food of immortality, which he rejects; but he certainly accepts the garment put on him and the oil brought, with which he anoints himself.49 Annus has pointed out that the epithet of the Old Babylonian Flood survivor, Atrahasis, meaning “exceedingly wise,” “is also an epithet of the sage Adapa in the Akkadian myth.”50 Annus interprets Adapa’s refusal of the “food of life” and the “water of life” as virtuous acts, in that the sage stays away from the “foodstuffs forbidden to humanity.” He sees Adapa’s accepting the garment and ointment as the “main elements of assuming divinity,” which he compares to Enoch’s transformation in heaven according to 2 Enoch 9.17–19. The Enoch incident also involves garments and anointment with oil.51 In her study on “ascent apocalypses” of the ancient Jewish and Christian traditions, Martha Himmelfarb designates this Enochic episode as the “investiture” of a “heavenly priest,” especially by virtue of its including clothing and anointing.52

If the upper register of the central panel of the Mari painting is a depiction of the king’s assuming divinity as a result of the encounter with Ishtar and her conferring on him supra-royal insignia, the ring and rod, we come full circle to the question of investiture. Not being restricted to a technical definition of the term in its referring exclusively to the conferral on the king of the throne, the crown, and the scepter, as attested in the royal inscriptions of the Ur III and Isin periods, we may embrace in relation to the Mari painting its sense of the highest sacerdotal initiation of the royal figure, of which all enthronement and renewal of enthronement ceremonies in the ancient Near East must be considered reenactments.53

Flood traditions, which were not monolithic in ancient Mesopotamia, are also associated with the heroic god Ninurta.54 In Lugal-e (ll. 347–67), after having used the Flood as a destructive weapon, the god, connected with agriculture in addition to kingship, is described as gathering waters in one spot during the Flood and raising the vegetation in its aftermath.55 In this epic poem in Sumerian (vv. 682–97), known from Old Babylonian tablets, after his heroic exploits, Ninurta, as if he were not already a god, is given “a celestial mace, a prosperous and unchanging rule, eternal life, the good favour of Enlil … and the strength of An” by his father Enlil,56 all events evoked by the imagery of the upper register of the central panel of the “investiture” painting.

Thorkild Jacobsen reminds us that like Ninurta, Inanna, the Sumerian ancestress of Ishtar, too, presides over thunderstorms and rain that not only represent formidable destructive forces but also media of fertility and regeneration.57 Furthermore, Jacobsen points out the lion as an attribute of thunder gods, again such as Ninurta, and the lion-headed “thunderbird” as a being controlled both by Inanna and Ninurta.58 He also sees Inanna’s being a goddess of rain as a corollary of her identity as the lady or queen of heaven. Ishtar, in her incarnation as Belet-ili, the mistress of the gods, is also featured in the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh as the divinity who had commanded the Flood in the assembly of the gods.59 In sum, given the diversity and richness of the Flood traditions in ancient Mesopotamia, it would be appropriate to see Inanna/Ishtar as fully part of the rich milieu defined by this myth and its implications.

Defining Paradeigma

Even though Flood traditions in ancient Mesopotamia were diverse, they may all be thought to share a common paradigmatic basis, the renewal of the cosmic order and the immortalization of its chief royal protagonist in the aftermath of a cataclysmic ordeal.60 As such, the Mari painting, too, bears a relation to the same paradigmatic background without necessarily being a depiction of any specific one of the extant Flood stories. It shows a renewed terrestrial domain teeming with fertility and abundance, with its foundation deep in the pristine source of the cosmos, the Apsû, and the pathway of further ascent to the state of ultimate divinity across the rising levels of the celestial realm plotted out.

A cogent definition of the notion of paradigm, paradeigma in Greek, and exemplum in Latin, can be found in Gregory Nagy’s work Homeric Questions, where Nagy posits that regardless of the presence of and differences among different versions of a myth featuring different characters and variations in plot, the paradigm behind the myth per se would be unchanging and universal. He points out that it is this unchanging aspect of a particular myth that possesses authority and the capability to instruct and illuminate.61 This definition of paradeigma should be applicable, by extension, to the relevance of mythical structures and the ideas embedded in them to images that do not necessarily depict episodes from clearly identifiable legends and sagas preserved in texts. In order to invoke the paradigm of the cosmic order and its periodic destruction and renewal in ancient Mesopotamia in the iconographic analysis of the “investiture” painting, we do not need to find Enlil, Ninurta, Utnapishtim, his wife, Ziusudra, a boat, or a figural Flood narrative identified step by step in its imagery. The paradigm offered by the myth would still be valid, authoritative, and illuminating in understanding the image. Indeed, within ancient modes of visual communication, images may be that very paradigm pure and simple.62

By the same token, conceptions of ascent evoked by the imagery of the painting would not be incompatible with the literal absence of ascent in the Flood accounts preserved from ancient Mesopotamia. With its description of the ark as a multi-tiered cosmic enclosure comparable to the ziggurat of Babylon, the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh may already signal the Flood myth as the foundation to ascent to heaven. In addition to the mythical models of Etana and Adapa, the phenomenon of ascent to heaven is not absent in ancient Mesopotamian royal ideology. We find oblique references in the Ur III period and the Isin Dynasty to the ascent to heaven of deceased kings who were also deified during their lifetimes, Shulgi and Ishbi-Erra (2017–1985 bce).63 Regardless of whether or not the Mari king was deified, the “investiture” painting makes a powerful visual statement in laying out the complexity of a process of immortalization leading to ascent and apotheosis in a way in which no textual account from ancient Mesopotamia preserves.

Albeit presented in both ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia through funerary notions, the process of the royal ascent to heaven need not be understood in an exclusively post-mortem context. At another level, it may also characterize the experience of a special human being, always cast in the guise of the king in the ancient Near East, while still alive. As outlined in the Introduction, this experience can be thought of as shamanic or mystical, since it entails an encounter with a formidable divine force or a visit to a divine realm within the confines of a human lifetime, with results affecting favorably the relevant individual’s ontological status both in life and at death, making him partake of the divine or immortal. This process should also be thought of as containing a series of stages or levels, again commensurate with the sense of stratified gradation permeating the Mari composition. The Flood myth provides the most relevant foundation in the textual domain for the analysis and discussion of the terrestrial or paradisiac component of this process, which is closely connected with the Apsû, both at the level of individual immortalization and at the level of the world order and its renewal.

The Mari Painting and the Assyrian “Sacred Tree”

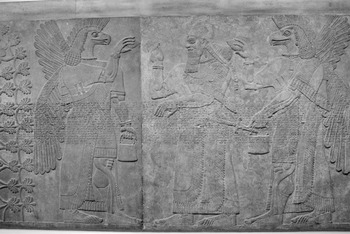

An arboreal and aquatic manifestation of the principle of time and space represented by the Apsû and its relation to a celestial domain may also be found in the celebrated image of the Assyrian “sacred tree” behind the throne of Ashurnasirpal II in the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (Fig. 3).64 Like the Mari painting, this image, too, is often understood as an expression of the Assyrian king’s relation to the state gods of his polity in enabling the prosperity of his land and the upholding of the cosmic order. A parallel reading of this composition against the backdrop offered by the present discussion would help probe additional layers of meaning in this composition as well. Such an endeavor would prove the Mari painting itself as a paradeigma in constituting a prototype and precedent for the visual expression of a process of immortalization and ascent found in this equally potent image about a thousand years later. While they seem quite different at first sight, upon close analysis, the conceptual and structural affinities between the two compositions become clearer.

We have seen above the parallelism in key passages between the Flood accounts from the Old Babylonian period and those from the first-millennium bce Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh. Attention to an analogous continuity in the language of images would enable a better understanding of what we are so apt to consider as individual works of art isolated by space and time, only to be dealt with in their own spatial and temporal contexts. With their locations north of Babylonia, Old Babylonian Mari and the political center of the Neo-Assyrian Empire were both on territory open to ideas and exchanges from different directions, while being at the same time anchored in a by and large Babylonian cultural sphere.

The “investiture” painting, along with the other paintings unearthed in the palace at Mari, show that examples of monumental wall decoration in ancient Mesopotamia preceded the orthostat reliefs of the Neo-Assyrian palaces by at least one thousand years.65 The palace establishment was the center of the intellectual life both in the kingdom of Mari and the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and there are noteworthy parallels in the architectural layout of the palace structures. In both, we see principles of planning centered on two courtyards, in one of which was nestled the throne room suite, as well as the presence of a visual program in the form of monumental wall decoration. The Mari throne room suite, however, has two principal spatial components to it, Rooms 64 and 65, and it is the definitive culminating point of a circulation path. By contrast, Neo-Assyrian throne rooms encompass a single primary space and offer routes of transition between the two courtyards of their palaces. Both the Mari painting and the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel come from throne room contexts; the former from a throne room façade, the latter from a throne room interior.

As we have seen, the scholarly cultures of both the Mari and Neo-Assyrian courts, with their emphasis on monitoring the wellbeing of the king and the success of the state through prophecy and divination, are also comparable in the extensive documentation they left regarding the activities of their practitioners. The affinity between the art of Old Babylonian Mari and Neo-Assyrian art may also be observed in parallel approaches to sculpture in the round. The statue of the Mari goddess holding the flowing vase (Fig. 16) is the ancestress of the statues of male minor deities also holding the flowing vase found in the temples of Khorsabad.66 In many respects, a comparative treatment of the crucial emblematic images of these two representatives of the ancient Mesopotamian visual tradition would broaden our perspective.

The Assyrian “sacred tree” panel, like the “investiture” painting, is a symmetrical composition in which the use of dissymmetry has also an important role. Both compositions have a prominent arboreal component. The Assyrian “sacred tree” composition takes the single central figure of the Mari king and reduplicates it, placing it on both sides symmetrically. It compresses the pair of trees into one and places the result at the center (Fig. 3). The Assyrian tree is a complex ornamental representation that combines natural vegetal elements with what may be understood as a fantastic floral dimension.67 What the Mari painting parses as two different species of trees, one natural, the date palm, and the other possibly fantastic, connected by means of the horizontal elements supporting the mythical quadrupeds, the Assyrian “sacred tree” merges into one design. In turn, the Assyrian “sacred tree” deploys a number of linear elements connecting various parts of the tree to one another (Figs. 3 and 29). Albeit a controversial matter, the Assyrian tree may have drawn some of its inspiration from the date palm, a tree associated with longevity in certain traditions of antiquity.68

The presence of a supreme deity, Ishtar, in the upper register of the central panel of the Mari painting finds its counterpart in the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel at the apex of the composition in the form of the winged disk and the figure of the god depicted in it, who, like Ishtar in the Mari painting, is shown holding the ring, although without the rod (Figs. 3 and 13).69 This god, who may be Ashur, the Assyrian state deity, is shown gesticulating toward the figure of the king to the right of the tree. This king points to the winged disk, while his counterpart on the other side of the tree is shown pointing to the tree itself (Figs. 3, 13, and 30).

30. Detail of Fig. 3 showing the king to the right of the “sacred tree.”

The idiom of dissymmetry coupled with that of the meaningful occurrence of touch/no touch observed in the lateral panels of the Mari painting may also be noted in the way the royal figure holds the mace in the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel. Whereas the king at left holds his mace horizontally, inevitably overlapping or touching the tree with it (Fig. 29), and reveals his affinity to the earthbound; the king at right holds his mace vertically with no overlap with the tree (Fig. 30), revealing his dissociation from the terrestrial and his affinity to the celestial.

As underlined in Chapter 1, numerous compositions in the glyptic imagery of Babylonia and Assyria of the second and first millennia bce bring together “sacred” or stylized trees with elements of the flowing vase and streams of water, revealing the affinity between the tree and the flowing vase (Fig. 31).70 The presence inside the field defined by the Assyrian tree of wavy lines culminating in or connected with curlicues, reminiscent of spirals, may be taken as further indication that there is an aquatic component in the complex ornamental design of the “sacred tree” (Figs. 3 and 29).71 A subtle visual parallel also exists between the way the stream-like branches emanating from the trunks of certain representations of the “sacred tree” crisscross the field inside the tree and the way in which streams of water emanating from flowing vases form similar patterns in designs that bring together rows of flowing vases, as discussed in the previous chapter (Figs. 21–22 and 29).72

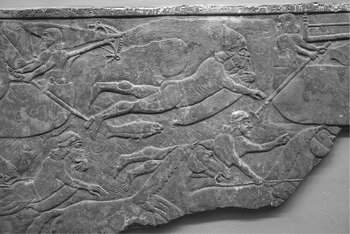

That there is a connection between curlicues or spirals, such as seen inside compositions of Assyrian trees, and water may be ascertained through observing that bodies of water, especially rivers, are rendered with such designs in the Neo-Assyrian palace reliefs depicting military campaigns (Fig. 32). With its hybrid arboreal and aquatic formation, the Assyrian “sacred tree” could be thought of as a visual embodiment of the Apsû itself.73 It is shown here in its role of constituting a substructure for the celestial domain. With its multiple levels, the tree mediates between the earth and heaven in a process of immortalization and ascent expressed through the two figures of the king, each of which stands for one of the two crucial phases of this process.

The king at left touching the tree with his mace and pointing to it with his free hand represents the status attained by the Flood Hero in the aftermath of the Flood, a paradisiac longevity, immortality, or sacral time embodied by the tree and the flowing vase, the background to ultimate ascent (Figs. 3 and 29).74 As for the king at right, even though literally “on earth,” by virtue of his distance from the tree and pointing to the firmament, he represents the status of full-fledged apotheosis in heaven, the outcome of ascent, which the Mari scene shows in the upper register of its central panel (Figs. 3, 7, and 30). In this relief composition, there is a much more explicit reference to the paradigm provided by the Flood myth than in the Mari painting. Flanking the group with the tree and the royal figures are human-headed apkallus, antediluvian sages, whose presence in a variety of different guises throughout the Northwest Palace at Nimrud constantly signal the claim of the residence of Ashurnasirpal II to being an embodiment of the antediluvian, or primordial, cosmos.75

Contemporary scholarship has long turned away from the earlier idea that the Assyrian “sacred tree” represents some kind of “tree of life,” and proposed explanations putatively more appropriate to the idiosyncratic characteristics of ancient Mesopotamian culture than what seemed to be an easy biblical model.76 However, if the Assyrian “sacred tree” is indeed a conception of terrestrial paradise, a state of immortality that extends to eternity, with the possibility of leading to a higher level of celestial divinity, the idea that the tree is after all some kind of “tree of life” becomes inevitable.77 One can remember how the plant of life or immortality Utnapishtim reveals to Gilgamesh is also a plant found in the Apsû.78 In the final analysis, the realm of Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh can be seen as the conception of a “golden age” that now exists in a crypt, and functions as a restricted source of possibility to transcend, through eternal time, the ordinary human condition defined by death, leading to further levels of liberation and ascent.

Postscript on Shamanic Lore in the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia

As is the case with the Mari painting, questions of immortalization and apotheosis expressed through the figures of the Assyrian king need not be confined to a vantage point that investigates whether or not the king was deified in a particular era of ancient Mesopotamian history. In both the Mari painting and the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel, the royal figure is the medium of signification through which the hieratic processes and conceptions in question are expressed, not that these processes and ideas applied solely to the king. It is in fact much likelier that the master minds, such as scholars and artist-sages, behind the creation of these images expressed, through the figure of the king, ideas and phenomena that applied more directly to their own ontological and spiritual privileges as “godlike,” “royal,” or “shamanic” men than to the experience of the king himself as a person.

It is in this sense that the images in question, especially those that bring together a solar symbol over a vertical element, may be diagrammatic accounts of shamanic experiences. On his ascent to heaven, the shaman climbs a vertical post with notches and gradually makes his way to its apex, whence he makes a transition to the ultimate point of the journey, an exit through the sun into the presence of the supreme deity.79 Even though the shaman’s journey to the beyond is a concrete experience, the steps followed in this practice have their philosophical or mystical counterparts in an individual’s progress from death, across immortality, to a final exit from temporal contingency altogether in the form of an ascent. This trajectory may even be experienced in its entirety within the confines of a human lifetime, without, however, the elimination of the threshold of death, as already stressed.

A significant number of the apkallus shown flanking the Assyrian “sacred tree” or the king himself in the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud are winged and bird-headed (Fig. 33). These are thought to be the heads and wings of an eagle, even though they may also be those of a vulture. Even the human-headed apkallus such as those flanking the “sacred tree” slab from the throne room, are winged, sharing the winged quality of the solar disk itself, whose wings, too, are those of an eagle (Figs. 3 and 12). Given that the animal most closely associated with shamanic ascent is the bird, especially the eagle, the eagle-headed and winged sages of early Neo-Assyrian art may also point to the presence of shamanic lore in this artistic tradition.80

In ancient Mesopotamian myth, the eagle is also the medium of ascent for Etana in his quest for the plant of life, which, in contrast to the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh, is in heaven as opposed to the earth.81 The mythical bird Imdugud or Anzû, too, may be shown in the art of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia as a lion-headed eagle.82 The visual manifestations of a variety of deities and divine beings as animal-headed both in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, not to mention the numinous characters of birds such as the vulture and the eagle, may betray a shamanic substratum in the religions of the ancient Near East. This substratum may have been assimilated fully to state ideologies governed by rulers and scholars and expressed most directly in fine art.83

The Neo-Assyrian figural type of the winged bird-headed human goes back to the Middle Assyrian period. Its association or equation with the Babylonian concept of the antediluvian sage was the result of the final codification of Assyrian art at the beginning of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. It is not clear if the figural type already stood for the apkallu in the Middle Assyrian period. Diana Stein has plausibly argued that the hieratic vocabulary of Neo-Assyrian art in the form of stylized trees, winged disks, and winged beings originally represented “popular themes” at home in the ritual world of the Zagros foothills, or the highlands, such as the hunter’s dance and trance experiences.84 She has seen the glyptic art of the kingdom of the Mittani as a direct expression of this ritual world. Drawing a link between the imagery of Mittanian glyptic and prehistoric art, Stein posited that the art of the Neo-Assyrian Empire translated these elements into a systematically codified iconographic repertoire in the service of an imperial state.

Even though Stein makes no reference to shamanism in her discussion, the phenomena she invokes, especially trance experiences, ritual dance, or the state of enlightenment reached as a result of ritually induced altered states, are commensurate with shamanic practices. In this respect, the possible presence of shamanic lore in the art of the early Neo-Assyrian Empire may have been enabled by a Middle Assyrian conduit, which in turn would have been informed by a Mittanian precedent. Such lore would be a source of richness in the codification of Neo-Assyrian art rather than a trait that should threaten or undermine its unique character.

In the Mari painting as well, wingedness is not only the natural quality of the oversized blue bird captured in flight (Figs. 2 and 28), but also an aspect of the two top mythical quadrupeds of the side panels (Figs. 2 and 5). As is the case with the Neo-Assyrian winged beings, we see here two kinds, the winged human-headed being, the potential sphinx, and the winged eagle-headed being, the potential griffin. Thus, the parallels between the Mari painting and the art of Ashurnasirpal II are not only compositional but also to a certain extent figural, once again pointing to the crucial link in tradition between these two artistic corpora despite the chronological distance that separates them.85

Matters of shamanism are being increasingly invoked in the study of the ancient world by scholars of the visual arts as well as literary works. On the one hand, it is a drastic shift to start thinking of the works of art or images so familiar to us from the study of the art and culture of the ancient Near East not merely as expressions of national and political identity, as we have come to perceive them for decades. On the other hand, it is imperative that we move beyond the limitations of these previous approaches in opening up opportunities to understand these images better and possibly in ways much more commensurate with the mindsets of their creators. Engaging with such underlying trends and practices would allow us to look at art as more of a continuum, and thereby see more in the art of each culture and period than we would if we continued looking at it solely in the vacuum of its own period.