Download this activity worksheet here

Verbal hygiene

In April 2021 a famous sportsperson posted the question above on their Facebook page. The post went viral receiving 58 thousand likes, 11 thousand shares and 910 thousand comments. Opinions about various features of language were expressed by their followers, and some illustrative comments include:

- “At the end of the day.” The most overused phrase in America today. STOP IT!

- “No problem” instead of “you’re welcome.”

- I’m no grammarian, but it always bugs me to hear people say “irregardless”.

- When people use the “F” bomb every other word in a sentence

- Drives me crazy when people use “seen” wrong. For goodness sake, you saw it!

- Being the grandmother of a granddaughter with Down Syndrome I can’t tolerate people calling other retards. That is a derogatory use of the word.

- I could care less…….what you really mean is I couldn’t care less.

- Any sentence that ends with a preposition. Such as “Where is he at”.

- “Should of” instead of “Should have”!

- When someone calls their significant other “bae” or “boo”

- When people don’t pronounce the “t” in words. I even hear news announcers do this.

Mountain

Mou-in

Forgotten

Forgo-en

This is a relatively new thing and I hate it.

- Conduct your own survey with your own contacts to collect similar examples of verbal hygiene.

- Categorise the language features that were commented upon based on whether they are grammatical, phonological, or lexical.

- Are there any recurring language features in the comments?

- Compare your findings with those of your peers.

Download this activity worksheet here

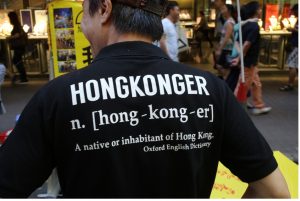

Indexicality and tee-shirts

In Chapter 2 we talked about how sometimes the important thing about the language that we see on people’s tee-shirts is not (or not just) its semantic meaning (the ‘dictionary meaning’ of the words), but also its indexical meaning (the kinds of people, places, attitudes, etc. that it ‘invokes’). Indexical meaning can be a matter of the ‘code’ used in the writing on tee-shirts (e.g. ‘French’, ‘Japanese’), but it can also be a matter of the register or style that is used, or even the genre.

We also talked in Chapter 2 about orders of indexicality, and discussed how the indexical meaning of a tee-shirt depends on who is wearing it and where they are wearing it.

Look at the tee-shirts below and discuss the possible indexical meaning of the writing on them and what you think they communicate about the people who are wearing them. Also talk about whether or not you think the meaning would change if the tee-shirt were worn by different kinds of people or in different places.

- What are the possible indexical meanings of the writing?

- Do these indexical meanings change depending on who is wearing the tee-shirt or where it is worn

Hong Kong, 2015, ©Adam Jaworski

London, 2019, ©Jackie Jia Lou.

London, 2019, ©Jackie Jia Lou.

Photo credit: David J (CC BY 2.0)

Photo credit: Heidi de Vries (CC BY 2.0)

Now watch Dr Jackie Jia Lou talk about her project on ‘wearable text’.

Download this activity worksheet here

Youth language in Manchester

In Chapter 3 we discussed Rob Drummond’s work, which explored youth language in Manchester, UK. The project’s two main research sites were inner-city learning centres, which catered for students who have been permanently excluded from mainstream education.

The example below comes from an interview the researcher had with two students, Abdou and Jake. Abdu is black but he could not decide if he identified as Black African or Black British. He was part of a dominant group of boys of mixed ethnicities, and he was a heavy user of Multicultural Urban British English. In fact, Abdu was one of the two heaviest users of word initial th-stopping. During the interview, the researcher brought up the point about saying ‘tree’ instead of ‘three’.

Read the interview below and discuss Abdul’s attitudes towards his own language use. How does he describe it? Does his reaction surprise you? How can you explain his reaction?

1 Res: I heard you saying downstairs about whether you say [t]ree or not. Do you

say [t]ree? You say [t]ree sometimes.

2 Abdou: No I don’t

3 Res: Don’t you?

4 Jake: Yeah you do yo, you say [t]ree bro.

5 Abdou: No I don’t.

6 Jake: Yeah you do.

7 Abdou: Yeah it’s f- okay

8 Res: Why what’s wrong with saying [t]ree?

9 Abdou: I don’- I jus- cos it’s not [f]ree[1]

10 Jake: You always say [t]ree I don’t know what you’re on about.

11 Abdou: But it’s not but I don’t though.

12 Jake: You do.

13 Res: But why is it wrong to say- it’s not wrong, it’s not wrong to say…

14 Abdou: It’s not wrong but obviously I don’t say it, cos it’s not [f]ree.

Reference

Drummond, R. (2017). (Mis)interpreting urban youth language: White kids sounding black?, Journal of Youth Studies, 20(5), 640-660.

[1] It should be pointed out that ‘f’ for ‘th’ (known as th-fronting) is by far the most frequent pronunciation

of words such as three, think, mouth, etc. So in this excerpt, ‘free’ should be seen as Abdou’s personal ‘standard’ pronunciation.

Download this activity worksheet here

GIFs: Recombination and recontextualization

In Chapter 4 we talked about how recombination (the mixing of different modes) and recontextualization (the transportation of a text or utterance from one context to another) are both important aspects of multimodal communication, particularly online. In this activity, you should visit the website Giphy and collect three different animated Gifs which include an image and written words. For each one, talk about how the meaning of the image affects the meaning of the words and how the words affect the meaning of the image. Then imagine two different contexts/situations in which you might send this GIF to a friend. How would the meaning of the GIF change in these two different contexts?

Consider the following 4 questions or situations for each GIF and use the downloadable worksheet to fill in the table for each question:

- How do the words affect the meaning of the image?

- How does the image affect the meaning of the words?

- Situation 1 in which you might send this to a friend

- Situation 2 in which you might send this to a friend

Reference

Giphy https://giphy.com

Download this activity worksheet here

Translanguaging in the classroom

The extract below exemplifies a typical instance of translanguaging in the classroom.

Mrs Indra, a Class IV teacher in a rural school outside Bhopal, describes how she has started to incorporate translanguaging in her language lessons.

Many of my students are not first-language Hindi speakers. Since I started incorporating translanguaging practices into their language lessons three months ago, they have become much more talkative and engaged in their learning. Their confidence in using Hindi has noticeably improved too. I have observed that monolingual Hindi speakers in my class are starting to pick up words and phrases from their classmates as well.

If my students are going to read a section or page of their Hindi textbook, I begin by introducing the topic, inviting my students to volunteer anything they know about it and encouraging them to translate the key Hindi vocabulary into their home language. I ask them to help me if I can’t follow what they are saying.

I then ask my students to read a section or page of their Hindi textbook aloud in pairs or small groups, or silently and independently on their own. In either case, I invite them to pause at the end of each page or section and discuss what they have just read with their partner or other group members, making sense of it and establishing the meaning of any unfamiliar words together. I suggest to them that they use their home language for this. I encourage them to add any new words or expressions in the dictionaries they have created.

If I want pairs or groups of students to present something to the rest of the class in the school language, I encourage them to use their language to discuss how they will express their ideas first. I do the same if I want them to write a summary or report in the school language.

To maintain the interest of all my students, I try to vary the organisation of the pairs and groups, while ensuring that they include at least two students of the same home language each time. Sometimes I place students with similar competence in the school language together. At other times, I place a more confident student with a less confident one, so that the former can support the latter in their shared home language. If there is someone in the group who does not speak the shared home language, I ensure that my students translate what they are discussing into the school language.

Recently I located a traditional short story that was available in Hindi and my students’ home language. I used this with my Class VII students. I made copies of the stories in each language and got small groups of students to read them in parallel. I then invited them to use their home language to compare the different versions of the two stories, including the key words that had been used in each

- Notice which parts of the activities Mrs Indra encouraged her students to do in their home language and which in the school language. Are there any patterns here?

- What instructions might Mrs Indra have used to support the translanguaging practices described in the case study? Make a list of all those you can think of.

Source: The Open University (2022)

https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=64814§ion=6

Download this activity worksheet here

Style online

We don’t just alter our linguistic style according to whom we are talking to in face-to-face communication. We also do so when we communicate online. In Chapter 6, for instance, we talked about a study by the sociolinguist Jannis Androutsopoulos (2014) in which he explored the ways Facebook users changed the way they used language based on who they wanted to include in their communication. Other studies have also shown that people alter the way they deploy communicative resources online based on who they are communicating with. Areej Albawardi (2018), for example, found that when Saudi University students use WhatsApp, they alter the way they use emjois and the ‘non-standard’ internet variety, Arabizi (a way of writing Arabic using Roman characters and numbers) depending on whether or not they were chatting with family members, friends or teachers. In another study focused on social messaging applications, Kate Muir and her colleagues (2017) found that people tend to accommodate to each other in terms of the style of their messages when they communicate online, and the degree to which they accommodate can affect the impressions others have of them.

In this activity, you will analyse your linguistic style on WhatsApp or a comparable instant messaging application, particularly your use of emojis, abbreviations and non-standard spellings.

Choose several different conversations with different kinds of people from your WhatsApp history (e.g., parents, friends, classmates). Look through the conversations and fill out the chart below. You will need to quantify the number of times you used emojis/ abbreviations/ non-standard spellings as a ratio of the total words or other symbols you used in the chat or section of the chat you are analysing. You should also consider the kinds of emojis and abbreviations that you and the other person used.

Then consider:

- Do you change your style when you chat to different people on WhatsApp? How and why?

- To what degree do you accommodate to the people that you are chatting with? Are there times when you do not accommodate (diverge) from your chat partner’s style/ Why? What’s the effect?

Use the downloadable worksheet to fill in the details about your chats in WhatsApp.

References

Albawardi, A. (2018). The translingual digital practices of Saudi females on WhatsApp. Discourse, Context & Media, 25, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.009

Androutsopoulos, J. (2014). Languaging when contexts collapse: Audience design in social networking. Discourse, Context & Media, 4–5, 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2014.08.006

Muir, K., Joinson, A., Cotterill, R., & Dewdney, N. (2017). Linguistic style accommodation shapes Impression formation and rapport in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 36(5), 525–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X17701327

Download this activity worksheet here

Accent attitudes

The Speech Accent Archive is a popular database of people’s speech in different accents in English. Creators of the archive asked people from all over the world to read the following passage:

Please call Stella. Ask her to bring these things with her from the store: Six spoons of fresh snow peas, five thick slabs of blue cheese, and maybe a snack for her brother Bob. We also need a small plastic snake and a big toy frog for the kids. She can scoop these things into three red bags, and we will go meet her Wednesday at the train station.

The archive is mostly used by linguists interested in phonetics and phonology to study how speakers of English in different regions, as well as speakers of English language around the world, produce different sounds. The archive allows users to search by region and by ‘native language’ of speakers.

Since all of the speakers are saying the same thing, the database can also be used to conduct informal studies of people’s attitudes towards different accents.

Use the downloadable worksheet to fill in this scale.

Reference

George Mason University. The Speech Accent Archive, Available at http://accent.gmu.edu/browse.php

Download this activity worksheet here

Using smartphones to document linguistic landscapes

In 2015, Leonie Gaiser and Yaron Matras from the Multilingual Manchester research unit at the University of Manchester worked together with the University’s Research IT department to develop LinguaSnapp.

LinguaSnapp is a smartphone application that can be used to study linguistic landscapes by documenting, mapping and analysing signs in public space. So far it has been used by scholars to investigate multilingualism in Manchester, Melbourne, Jerusalem, Birmingham and Hamburg.

- For this activity you need to choose an area, neighbourhood, high street, or other location that you want to investigate.

- Download the LinguaSnapp application on your smartphone.

- Use this mobile app to take photos of signs in your chosen locale.

- For each photographed sign, add information on code choice, content, and context. These analytical descriptors accompany the image alongside automatically generated GPS-coordinates that capture the location coordinates where the photo was taken, as well as the date and time the image was created.

- You can then use the data you collected to create a publicly accessible interactive online map, which visualises the geographical distribution of your images. Here is an example of interactive map from the Multilingual Manchester

Click here for more guidelines on how to use LinguaSnapp.

References

Gaiser, L. E. & Matras, Y. (2021). Using smartphones to document linguistic landscapes: The LinguaSnapp mobile app. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(1), https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2019-0012

Download this activity worksheet here

Communicating across scales

Choose a moment of communication such as an interaction in a classroom or a consultation with your lecturer or tutor, a meeting of an organization you belong to, an online interaction (such as on a MMOG site), a public event, or any other kind of communication where people from different places or with different kinds of power relationships interact.

Think about what kinds of ‘scales’ are relevant to this moment of communication. Remember scales can be spatial/geographical (e.g. a room, a building, a campus, a city, a state, a country), temporal (a class period, a week, a semester, a year, a university career, a lifetime), or social/institutional (a department, a faculty/college/school, a university, an educational system).

Think about the kinds of people, objects, facts, and relationships that are relevant to these different scales, and also the kinds of power relationships (who has relatively more power on this scale?).

Use the downloadable worksheet to fill in the detail for each different scale.